1. Introduction

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), medical burn injuries are responsible for 4500 deaths annually in the US and result in 1.1 million patients requiring hospital or inpatient admission [

1,

2]. Although extensive burns requiring surgical treatment and prolonged mechanical ventilation accounted for 1,290 (4.4%) of all inpatient hospital admissions, deep burns requiring surgical treatment without prolonged ventilation account for 9,340 (32%) of all inpatient hospital admissions per year [

3]. In the United States, the average hospital fee for the care of a child (aged 5-16 years) with massive third-degree burns requiring skin grafting is more than

$140,000 [

4]. For adult populations, the average total medical cost associated with treating surviving burn patients ranges from nearly

$131,000 to

$157,000 per patient [

5]. Direct medical costs related to wound care, pain management, and rehabilitation therapy generate additional expenses. [

4] Unfortunately, the relatively long hospital stay in addition to requirements for specialized staff, advanced medical equipment, and state-of-the art technology lead to increased healthcare expenditures and significant social and economic effects for both survivors and their families [

4,

6].

Globally, the World Health Organization has declared that burns are the fourth most frequent type of injury, following traffic accidents, falls, and physical violence [

7,

8]. Medical care for burn victims continues to present major healthcare challenges [

8,

9]. There is a great demand for cost-efficient treatment options with early and complete wound coverage capabilities [

10,

11].

Even though the skin has high regenerative potential, its capacity for regeneration becomes reduced when it is injured beyond the reticular dermis. Because of the complexity of achieving satisfactory results and the possibility of wound contracture or hypertrophic scarring, there is an interest in using cellular and tissue-based products such as intact fish skin grafts (IFSGs) to provide a supporting structure for healing tissue, improve cosmetic results, and reduce donor site morbidities [

12,

13,

14].

IFSGs are tissue grafts that preserves the native three-dimensional architecture, mechanical properties, and bioactive components of the source tissue, including collagen, proteoglycans, glycoproteins, elastin, lipids, and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). The graft’s structural integrity closely resembles human skin and provides an optimal foundation for tissue regeneration [

15,

16,

17]. The IFSG can undergo a more gentle patented processing that retains the structurally and chemical complexity. This gentle processing has been made possible since there is no known viral disease transmission risk from the North Atlantic cod to humans [

10,

15]. Kerecis IFSG dressings are CE marked and were cleared in 2013 by the FDA for a variety of wound treatments, including the treatment of burn injuries [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Previous studies have not linked fish skin to autoimmune reactions and there are reduced cultural and religious barriers related to its use as compared to human transplanted tissue, bovine, or porcine products [

15,

16,

17,

21,

22,

23,

24].

A recent systematic review revealed 72 unique publications that addressed the use of fish skin in burns. Further refinement brought this number down to 14 meaningful articles: 3 pre-clinical, 4 case reports, 2 clinical pilots, 4 clinical cohorts, and 1 retrospective study [

25]. Results demonstrated that IFSG was an effective and low-cost alternative treatment for superficial partial-thickness burns. The review noted that many of these studies were relatively small and pre-clinical. While larger studies are being initiated that look at IFSG in the treatment of deep partial-thickness burns and possible future studies are being designed to look at IFSG in the treatment of full thickness burns, there is little available information for best practices using IFSG in burn injury.

The primary goal of this article is to help clinicians provide optimal patient care when utilizing IFSG for burn injury management based on the consensus panels clinical experience as well as their review and knowledge of the current literature and recommendations. Additionally, it is hoped that this consensus will inspire future efforts to further define and expand on the recommendations for using IFSG in burn injuries.

The recommendations presented in this paper are not meant to be guidelines, since they are not given by a recognized body, but are rather consensus statements based upon the current available literature and the extensive experiential knowledge of experts in burn care who use IFSG [

26].

2. Methods

2.1. Consensus Panel Participants

The expertise of the authors in this field is outlined by their experience seen in

Table 1.

2.2. Evidence to Support the Consensus Recommendations

The chair led a systematic literature search to identify all English-language publications about IFSG in the treatment of burns, categorize the main types of burns treated, and create questions for discussion. Searches on PubMed, ScholarOne, and Google Scholar databases were conducted prior to the April 2024 meeting. There was no date range used, since North Atlantic intact fish skin graft has only been commercially available for less than a decade. The terms searched included: “fish skin,” “intact fish skin graft”, “cod skin,” and “omega 3 fatty acid graft.”

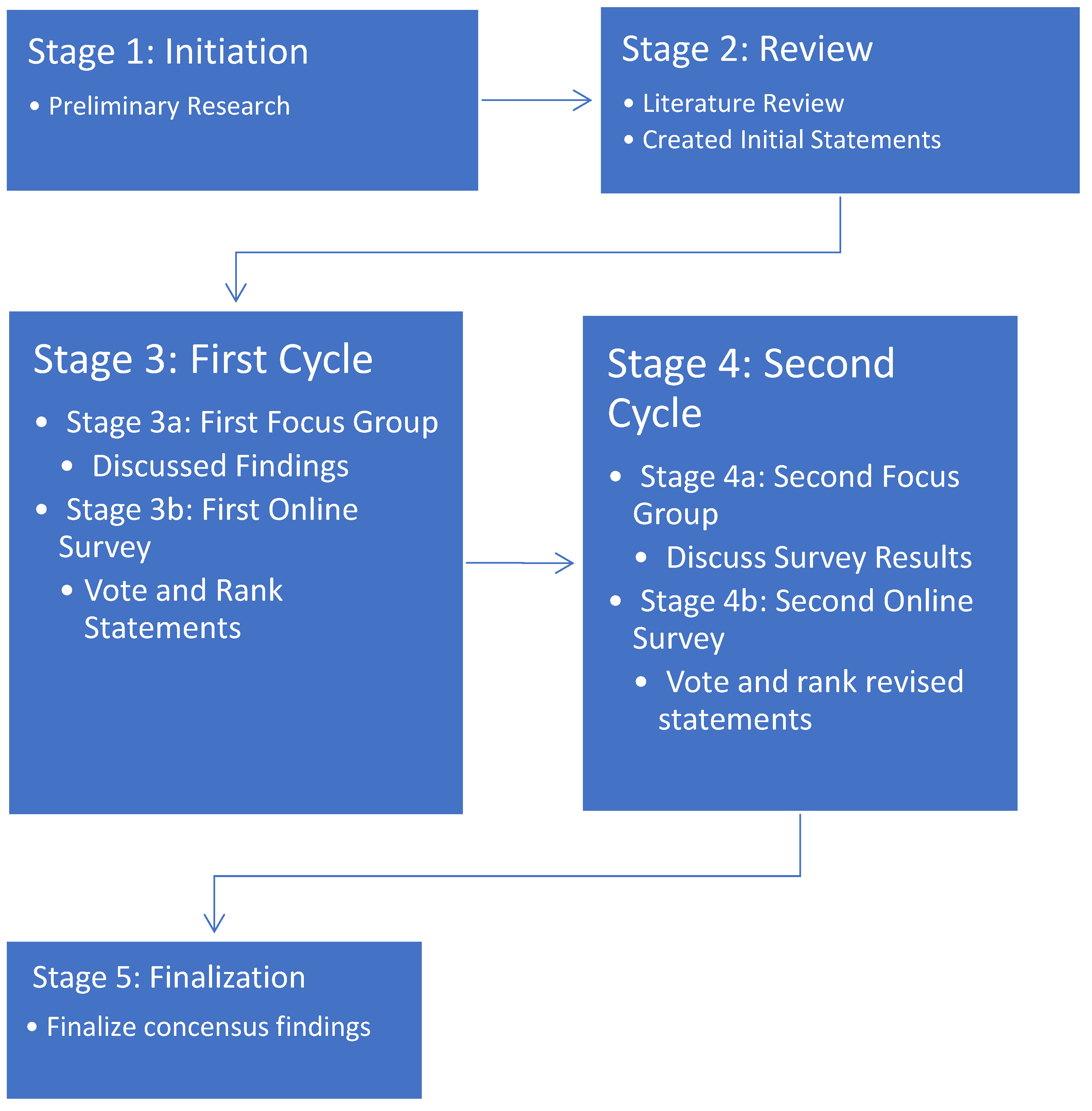

2.3. Consensus Methodology

A qualitative methodology was used based on the Nominal Focus Group (NFG) technique [

27]. This method combines Focus Group exploration and the Nominal Group Technique. The authors of the current study performed 2 cycles of the NFG process to develop consensus statements (

Figure 1).

2.3.1. Preparations (Stages 1 and 2)

A literature search was performed and review prepared on burn injuries (Stage 1) The results of this effort led to the panel creating statements for consensus review.

Consensus Recommendations for Optimizing the Use of Intact Fish Skin Graft in the Management of Traumatic Burn Injuries

2.3.2. Focus Groups (Stages 3a and 4a)

The panel met at the American Burn Association Annual Spring Meeting on April 9, 2024, in Chicago IL for the first meeting and in July 2024 for the second meeting. The first FG in April 2024 (Stage 3a) involved a discussion of the literature search findings and initial questions, and during the second FG meeting (Stage 4a) the panelists discussed the voting results of the first online survey. Each FG was moderated by the panel chair in a single session of nearly 3 hours with a 10-minute break. Each FG session was audio-recorded.

2.3.3. Online Surveys (Stages 3b and 4b)

The survey questions were generated from the transcript of the first in-person meeting and circulated by the chair. For both online surveys, panel members were invited to vote on and rank the importance of the consensus statements developed at the preceding FG meeting.

2.3.4. Consensus Threshold

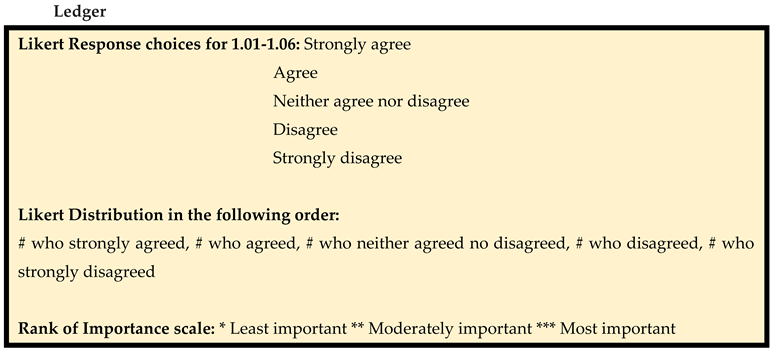

The surveys used a 5-point Likert scale, with 5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 2 = disagree, and 1 = strongly disagree. See

Table S2 for the distributions of ratings for each statement. Each statement was assigned a degree of consensus based on its score (sum of Likert scores × number of voters), which was then assigned 1 of 3 strength levels: full strong consensus (100% agreement [score of 35]), full consensus (80%-99% agreement [score of 28-34]), and no consensus (<80% agreement [score of <28]). Statements with full and full strong consensus (80%-100% agreement) were included in the final report of consensus statements.

In addition, the importance of each statement was categorized, with *** = most important, ** = moderately important, and * = least important. Finally, statements were grouped by burn injury type, order of importance (most to least), and percentage consensus (highest to lowest).

Figure 1.

A 2-cycle NFG method used for consensus statement development.

Figure 1.

A 2-cycle NFG method used for consensus statement development.

2.3.5. Consensus Statements Finalization (Stage 5)

A final report was created presenting the consensus statements in the context of the scientific literature.

2.4. Data Analysis

The audio data was transcribed, and relevant data were extracted and categorized and a thematical analysis was conducted. The data were quantified and analyzed with Spearman’s rank correlation (

Table S1) and Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance (

Table S3).

3. Results

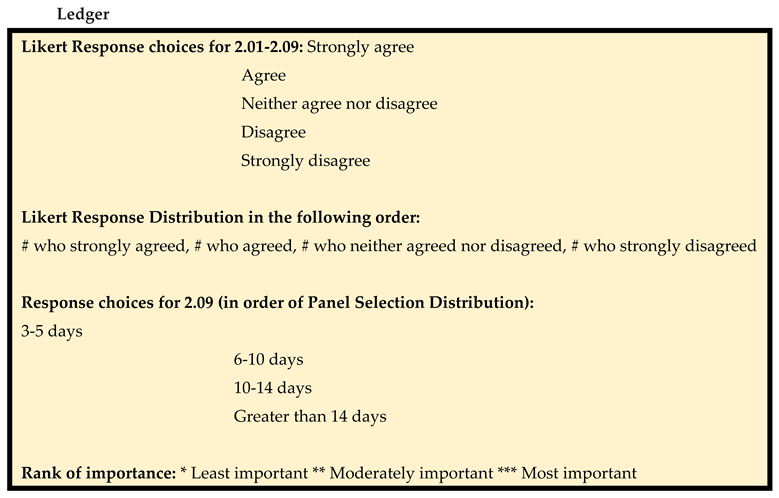

3.1. General Recommendations

There was 100% consensus that the primary goal of using IFSG was to provide appropriate wound bed preparation for facilitating wound closure (

Table 2).

To achieve optimal results, proper debridement is essential before initial IFSG application. If there is a requirement for a wound bed reapplication, panelists recommended no reapplication within the first 3-5 days and voted for either 6-10 or 10-14 days post-initial application as being the ideal time. All panelists either strongly agreed (71.43%) or agreed (28.57%) that application of IFSG allows the wound to be ready for split-thickness skin graft (STSG) earlier than would otherwise be the case.

The recommendations stress the importance of negative pressure wound therapy to bolster dressings when wounds are greater than 100 cm

2. Most of the panel members agreed that IFSG reduces a patient’s periprocedural pain and supportive literature indicates that IFSGs may reduce pain at skin graft donor sites [

28].

The panel reached a full consensus that the use of IFSG reduces the local wound care burden on nurses as well as other hospital staff. Additionally, IFSG use has the potential to decrease healthcare costs by reducing patient length of stay, inpatient hospitalization days, and number of dressing changes.

Next, the panel put forth recommendations for the use of IFSG according to wound severity or type.

Table 2.

General Recommendation for the Use of IFSG in the Management of Burns and Non-burn Traumatic Injuries.

Table 2.

General Recommendation for the Use of IFSG in the Management of Burns and Non-burn Traumatic Injuries.

| No. |

Statement |

Likert Response

Distribution

|

Consensus |

Rank of Importance |

| 2.01 |

Optimal results are obtained when an intact fish skin graft is used immediately after adequate debridement. |

5,2,0,0,0 |

94% |

** |

| 2.02 |

The goal of using IFSGs is to provide adequate wound bed preparation to facilitate wound closure. |

7,0,0,0,0 |

100% |

*** |

| 2.03 |

When there is a need for an additional dermal component prior to skin grafting, intact fish skin graft decreases the length of time to split-thickness skin grafting. |

5,2,0,0,0 |

94% |

** |

| 2.04 |

When using intact fish skin as a dermal component, the skin is more durable. |

2,3,2,0,0, |

80% |

* |

| 2.05 |

The use of intact fish skin reduces the local wound care burden on nurses and other hospital staff. |

3,4,0,0,0 |

89% |

** |

| 2.06 |

In your experience, does the use of intact fish skin have the potential to decrease healthcare costs by reducing length of stay, inpatient days, and dressing care. |

3,4,0,0,0 |

89% |

** |

| 2.07 |

For wounds greater than 100 sq cm, the preferred method for bolstering intact fish skin grafts is negative pressure wound therapy. |

5,2,0,0,0 |

94% |

** |

| 2.08 |

The properties of intact fish skin reduce the patient’s periprocedural pain. |

2,4,1,0,0 |

83% |

* |

| |

Polling on Optimal Reapplication Spacing |

Reapplication Range |

Panel Selection Distribution |

|

| 2.09 |

If the surgeon decides to reapply Kerecis for proper wound bed preparation, within how many days after initial application do you re-apply? |

3-5 days

6-10 days

10-14 days

Greater than 14 days |

0.00%

57.14%

42.86%

0.00% |

** |

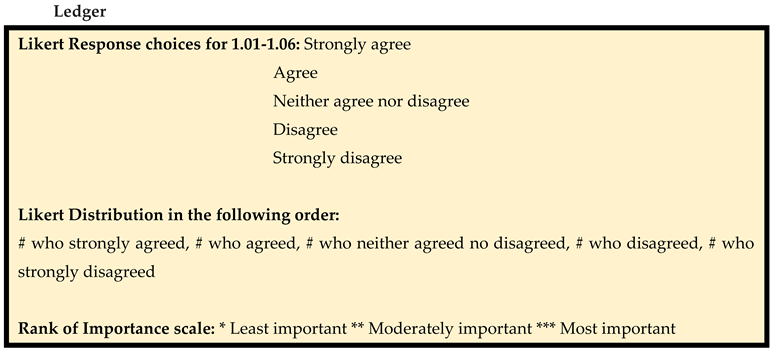

3.2. Epidermal/Superficial Burns

Superficial burn injuries affect only the epidermis and present with pain and symptoms such as swelling, erythema, and dryness [

29]. A superficial burn will generally heal by itself. Superficial or first-degree burn wounds with a minimal loss of barrier function usually do not require dressings, but topical balms and gels for pain relief and moisture retention [

29]. Additionally, cool showers and cold compresses also tend to offer relief as well as ibuprofen or paracetamol for pain during superficial burn injuries [

29]. The pain usually subsides within 72 hours and skin peeling occurs around Day 10 with no scarring [

29].

The panel did not reach a consensus that IFSG is needed to manage epidermal/superficial burns but rather either remained neutral, disagreed, or disagreed strongly with this statement (

Table 3). Instead, superficial burns should be treated according to standard of care (cleaning, pain medication, and adequate burn wound assessment [

30]). Since epidermal/superficial burns often heal rapidly (typically within a week) by keratinocyte migration and proliferation, advanced therapies are not needed [

31].

Table 3.

General Recommendation for the Use of IFSG in Burn Injury Types.

Table 3.

General Recommendation for the Use of IFSG in Burn Injury Types.

| No. |

Statement |

Likert Response

Distribution

|

Consensus |

Rank of Importance |

| 1.01 |

The application of intact fish skin grafts is beneficial for use in epidermal burns. |

0,0,1,4,2 |

37% |

* |

| 1.02 |

The application of intact fish skin grafts is beneficial for use in superficial-dermal partial-thickness wound types. |

1,2,2,1,1 |

63% |

*** |

| 1.03 |

The application of intact fish skin grafts is beneficial for use in mid-dermal partial- thickness burns. |

3,2,2,0,0 |

83% |

** |

| 1.04 |

The application of intact fish skin grafts is beneficial for use in deep-dermal partial-thickness burns. |

5,2,0,0,0 |

94% |

* |

| 1.05 |

The application of intact fish skin grafts is beneficial for use in full thickness dermal burns. |

7,0,0,0,0 |

100.00%

|

** |

| 1.06 |

Intact fish skin grafts are beneficial in traumatic wounds that involve the removal of the mid dermis. |

3,4,0,0,0 |

89% |

** |

3.3. Superficial-Dermal Partial-Thickness Burns

Superficial-dermal partial-thickness burns involve the upper part of the dermis in addition to the epidermis. The panel did not reach a consensus decision for the use of IFSG in the management of superficial-dermal partial-thickness burns; 42% (3/7) of panelists either strongly agreed or agreed that there was benefit in using IFSG for superficial-dermal partial-thickness burns. However, 29%8 (2/7) remained neutral and 29% (2/7). disagreed or strongly disagreed that IFSG was beneficial for burns of this severity. Those panelists who characterized IFSG as beneficial for superficial-dermal partial-thickness burns specifically cited evidence that IFSG can reduce pain as a factor in their decisions. Indeed, IFSG has been shown to significantly reduce pain at split-thickness skin graft donor sites [

28,

32].

3.4. Mid-Dermal Partial-Thickness Burns

A majority of panelists (71%) agreed or strongly agreed that IFSG was beneficial for the management of mid-dermal partial-thickness burns and a full consensus was achieved for this statement (

Table 3). No one disagreed that IFSG was beneficial in burns of this severity, but 29% remained neutral. The panelists agreed, however, that whether IFSG should be used on mid-dermal partial-thickness burns depended on patient status and morbidity, with higher risk patients more likely to derive benefit from IFSG.

A case series of pediatric patients from Staubach et al. in which burns including partial subdermal burns (as well as deep-dermal burns) were treated with IFSG reported no infections and good outcomes [

33].

3.5. Deep-Dermal Partial-Thickness Burns

Unlike superficial-dermal partial-thickness burns, deep-dermal partial-thickness burns extend into the deeper dermis and are drier and do not blanch [

31,

34]. Deep-dermal partial-thickness burns usually result in hypertrophic scarring and are the most difficult to assess and treat [

31,

35]. At this depth, burns are less painful due to partial destruction of pain receptors and healing tends to be slower [

31,

36]. Therefore, extensive injuries must be excised to a depth where the tissue is viable and then skin grafted to reduce morbidity and expedite return to normal function [

31]. However, some deep-dermal partial-thickness injuries will heal without skin graft in an optimized, uninfected wound environment.

The panel reached a full consensus that use of IFSG was beneficial in deep-dermal partial-thickness burns.

Indeed, IFSG has demonstrated similar results to STSG in the treatment of deep-dermal partial-thickness burns and has shown the potential to decrease the need for donor sites. In a retrospective case-control study by Wallner et al. that evaluated 12 patients with superficial and deep partial-thickness burns [

21], IFSG or STSG were applied to the deep partial-thickness areas of the burns and polylactic acid (Suprathel, GE) was applied to the superficial areas of the burns. In comparison to STSG or polylactic acidtreatment, IFSG demonstrated faster healing, reduced pain, and better scar quality as measured by water retention, elasticity, skin thickness, and pigmentation [

21]. In a study in which 18 patients received IFSG for deep-dermal partial-thickness burns after using a bromelain based enzymatic debrider, no one developed contracture of scar tissue and scar quality was good [

37]. The authors concluded that use of IFSG for deep partial-thickness burns could reduce the need for autografting [

37].

3.6. Full Thickness Dermal Burns

Full thickness burns pass through the epidermis and dermis to the underlying tissue [

29]. Full thickness burns usually present with almost no pain and require surgery since all regenerative elements have been destroyed in these type of injuries [

31,

34]. It is common for patients with full thickness burns greater than 10% TBSA to present with fluid leakage and tissue swelling [

35]. Due to destruction of all skin layers, including underlying subcutaneous fat, patients with full thickness burns are immediately referred to burn specialists to minimize morbidity, provide pain control, and help to achieve rapid healing [

34]. The initial assessment and management for severely burned patients should be similar to the approach for managing an essential trauma patient [

35]. A diverse, interprofessional approach is needed for full thickness burns since they generally require surgical treatment, such as skin grafting or flap coverage.

The panel reached a full strong consensus decision for the use of IFSG in the management of full thickness dermal burns, with all panelists agreeing strongly that the use of IFSG was beneficial in burns of this severity (

Table 3). Initial debridement is mandatory in preparing the wound for IFSG application, with consideration for pain management or hybrid debridement techniques, especially in the setting of often painful burn injuries. A standard sheet of IFSG with minimal trimming at the edges can be used to approximate the burn edges and prepare the bed for grafting. Nonadherent coverage and a bolster of choice can be used, with the panelists’ preferred bolster NPWT.

In full thickness burns, IFSG may be beneficial for preserving water loss and augmenting vessel repair as evidenced by the work of Wallner et al. and Stone et al. [

21,

38]. Further, IFSG was shown to prepare full thickness burns at least as well as cadaver skin allograft for STSG in a small investigator-initiated trial [

39,

40]. In this study, full -thickness burns were treated with either cadaver skin or IFSG and then underwent application of STSG one week later. At 21 days post-STSG, time to 100% healing was found to be equivalent between IFSG and cadaver skin with an epithelialization rate of 95% compared to 60% in IFSG and cadaver-treated areas, respectively. At 3 months, the Vancouver Scar Scale was better for the IFSG-treated areas, although this difference went away at 1 year. It is worth noting that, while not statistically significant (in such a small series), 2 of the 5 wounds that were treated with cadaveric skin had complete failure of “take” of the split-thickness skin graft while the 4 out of 5 treated with IFSG had 100% “take” at Day 7, and the one that did not have 100% “take” had 75% “take” [

39,

40].

The panelists also recognize that IFSG is not indicated for use as a definitive treatment of 3rd degree burns. However, despite that recognition there was 100% agreement that IFSG was beneficial.

3.7. Non-Thermal Injury to the Skin

Although the focus of the panel was burn injuries, panelists also discussed IFSG use in traumatic injuries. Each traumatic injury is unique and treatment should be tailored accordingly. It is important that patients receive multidisciplinary care, including good nutrition and stabilization of any underlying medical or orthopedic conditions.

Panelists agreed that IFSG is beneficial for use in traumatic injuries that involve the removal of the mid-dermis and reached a full consensus (

Table 3). Panelists indicated that IFSG provides adequate wound bed preparation to facilitate closure of these types of wounds.

Additionally, full consensus was reached among members that optimal results are achieved when IFSG is used immediately after adequate debridement (

Table 2). Panelists agreed that NPWT is the preferred method for bolstering IFSG in wounds greater than 100 cm

2, reaching a full consensus (

Table 2).

Early, adequate, and wide debridement is recommended for wound preparation. However, unlike in burns, IFSG should not be applied at the time of initial debridement in traumatic injuries. Instead, application should be delayed for a few days to allow clinical demarcation. In general, reapplication of IFSG in a stable trauma patient results in more rapid definitive surgical closure (within an average of 2 applications), potentially leading to a reduction in costs. In most traumatic injuries, especially in larger wounds, the use of fenestrated or meshed IFSG in combination with continuous NPWT for 72 to 96 hours is recommended, and early dressing change is advised.

3.8. Summary Recommendations

Table 4. summarizes the panel’s recommendations, mechanisms of action, and consensus strength across different burn depths and wound types, synthesizing the key findings from this consensus process.

4. Discussion

This consensus paper confirms what many burn surgeons already observe anecdotally: IFSG is most valuable when native dermis is largely lost, in deep-dermal partial-thickness and full thickness burns, and in traumatic wounds that excise the mid-dermis or beyond. In these settings the graft supplies an immediate, structurally intact skin structure rich in omega 3 fatty acids, lipids, limiting contraction, encouraging angiogenesis, moderating inflammation, and providing a stable dermal structure for subsequent keratinocyte migration or split-thickness skin graft (STSG).

Published studies support the views of the panelists. IFSG has been shown to accelerate healing in deep partial-thickness burns. In one study, deep partial-thickness burns treated with IFSG re-epithelialized faster than those treated with a synthetic template [

21]. IFSG was also shown to improve healing in deep partial-thickness wounds in a preclinical trial by Stone et al., which compared the efficacy of IFSGs to fetal bovine dermis grafts (FBD, Primatrix Integra, Princeton, NJ) in the healing 24 deep partial-thickness burn wounds on 6 anesthetized pigs [

10]. Burns treated with IFSG demonstrated quicker re-epithelization than those treated with FBD. The IFSG-treated wounds also showed more advanced angiogenesis than FBD-treated wounds 6 days and 13 days after graft applications.

Published studies also show the benefit of using IFSG for full thickness burns. For instance, in a study by Stone et al., IFSG was compared to allograft as a temporary covering for wound bed preparation of full thickness burn wounds before STSG [

38]. Thirty-six full thickness burn wounds were debrided and covered with either IFSG or cadaver porcine skin before application of STSG on Day 7. Results revealed that the burns treated with IFSG had similar outcome measures to the cadaver skin-treated burn wounds; however, the IFSG-treated wounds had more angiogenesis, granulation tissue, and immune cells in punch biopsies taken on Day 7 immediately before STSG application. These results suggest that IFSG has the potential to fill a current clinical gap as a temporary coverage for human burn injuries following both surgical or non-surgical debridement [

38].

By contrast, superficial burns re-epithelialize rapidly with standard dressings; adding IFSG offers negligible benefit for the added cost.

Beyond its role in improving healing outcomes, the panel noted secondary advantages of IFSG; procedural and background pain are markedly reduced, as has been shown in donor-site studies. For instance, in a study of 21 patients with STSG donor sites, 10 patients were treated with standard gauze dressing and 11 patients were treated with IFSG [

28]. Five days later, patients rated their pain levels according to the VAS scale and patients who received IFSG reported statistically significantly less pain than those who received standard gauze dressing.

The underlying evidence is drawn chiefly from small cohorts, single-center experiences, and preclinical models; robust, multicenter randomized trials are lacking. The panel’s unanimous support for IFSG may reflect user-experience bias, and participants’ practice settings in tertiary burn centers may not mirror conditions in community or resource-limited hospitals.

To bolster the evidence base, the group identified several research priorities: prospective multicenter RCTs comparing IFSG to cadaveric allograft and synthetic matrices in deep-dermal and full thickness burns; standardized pain-assessment protocols to quantify analgesic benefits; health-economic analyses stratified by burn size and payer; and long-term scar quality studies extending beyond 12 months.

5. Conclusions

In the authors’ experience to date IFSG appears to be most beneficial for deeper burn and skin injuries. Injuries, whether burn or traumatic, that extend into the deep dermis (deep second degree) or are full thickness (third degree) have the largest benefit from this therapy. Reapplication is fairly rare in this setting, and larger wounds benefit from NPWT bolstering. In general the entire panel agreed that IFSG needs to be studied separately, in a prospective manner, in both deep partial-thickness wounds and full thickness wounds.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, including Tables S1, S2, and S3.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S.; Methodology, J.L.; Formal Analysis, R.S. and J.L.; Investigation, R.S., A.C., J.L., M.Y., A.A., C.M., R.V.; Writing—original draft preparation, R.S. and J.L..; Writing—review and editing, R.S. and J.L.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Kerecis Limited LLC and the APC was funded by Kerecis Limited LLC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to that consensus documents in the U.S. do not usually contain informed consent/from the participants .

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to that consensus documents in the U.S. do not usually contain informed consent/from the participants.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Rajiv Sood, MD is a member of the Kerecis Scientific Advisory Board and, as such, receives fair market compensation for his time. John Lantis, MD is the Director of the Kerecis Scientific Advisory Board and, as such, receives fair market compensation for his time. Alfredo Cordova, MD; Marcus Yarbrough, MD; Ariel Aballay, MD; Carrie McGroarty, PA; and Ram Velamuri, MD all received fair market compensation for their time involved in the consensus panel meetings and for editorial and writing input.

References

-

Burns. CDC; 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/masstrauma/factsheets/public/burns (accessed on 9 August 2024).

-

Burn Incidence Fact Sheet. American Burn Association Accessed August 9, 2024. http://ameriburn.org/who-we-are/media/burn-incidence-fact-sheet/.

- 2020 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP)/National Inpatient Sample (NIS) data. Published online August 9, 2024.

- Peck M, Molnar J, Swart D. A global plan for burn prevention and care. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(10):802-803. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.08.059733. [CrossRef]

- Carter J, Carson J, Hickerson W. Length of Stay and Costs with Autologous Skin Cell Suspension Versus Split-Thickness Skin Grafts: Burn Care Data from US Centers. Adv Ther. 2022;39(11):5191-5202. [CrossRef]

- Chukamei ZG, Mobayen M, Toolaroud PB, Ghalandari M, Delavari S. The length of stay and cost of burn patients and the affecting factors.

- Smolle C, Cambiaso-Daniel J, Forbes AA, et al. Recent trends in burn epidemiology worldwide: A systematic review. Burns. 2017;43(2):249-257. [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz-Gospodarek A, Kozioł M, Tobiasz M, Baj J, Radzikowska-Büchner E, Przekora A. Burn Wound Healing: Clinical Complications, Medical Care, Treatment, and Dressing Types: The Current State of Knowledge for Clinical Practice. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3):1338. [CrossRef]

- Oryan A, Alemzadeh E, Moshiri A. Burn wound healing: present concepts, treatment strategies and future directions. J Wound Care. 2017;26(1):5-19. [CrossRef]

- Stone R, Saathoff EC, Larson DA, et al. Accelerated Wound Closure of Deep Partial Thickness Burns with Acellular Fish Skin Graft. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(4):1590. [CrossRef]

- Delaplain PT, Joe VC. Problems and Costs That Could Be Addressed by Improved Burn and Wound Care Training in Health Professions Education. AMA J Ethics. 2018;20(1):560-566. [CrossRef]

- Abazari M, Ghaffari A, Rashidzadeh H, Badeleh SM, Maleki Y. A Systematic Review on Classification, Identification, and Healing Process of Burn Wound Healing. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2022;21(1):18-30. [CrossRef]

- Lima Verde MEQ, Ferreira-Júnior AEC, De Barros-Silva PG, et al. Nile tilapia skin (Oreochromis niloticus) for burn treatment: ultrastructural analysis and quantitative assessment of collagen. Acta Histochem. 2021;123(6):151762. [CrossRef]

- Mokos ZB, Jović A, Grgurević L, et al. Current Therapeutic Approach to Hypertrophic Scars. Front Med. 2017;4:83. [CrossRef]

- Magnusson S, Baldursson BT, Kjartansson H, Rolfsson O, Sigurjonsson GF. Regenerative and Antibacterial Properties of Acellular Fish Skin Grafts and Human Amnion/Chorion Membrane: Implications for Tissue Preservation in Combat Casualty Care. Mil Med. 2017;182(S1):383-388. [CrossRef]

- Magnússon S, Kjartansson H. Decellulated Series: Physical Properties Supporting Tissue Repair. Icel Med J. 2015;101(12). [CrossRef]

- Kirsner RS, Margolis DJ, Baldursson BT, et al. Fish skin grafts compared to human amnion/chorion membrane allografts: A double--blind, prospective, randomized clinical trial of acute wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2020;28(1):75-80. [CrossRef]

- Luze H, Nischwitz SP, Smolle C, Zrim R, Kamolz LP. The Use of Acellular Fish Skin Grafts in Burn Wound Management—A Systematic Review. Medicina (Mex). 2022;58(7):912. [CrossRef]

- Júnior L, Maciel E. Nile Tilapia Fish Skin–Based Wound Dressing Improves Pain and Treatment-Related Costs of Superficial Partial-Thickness Burns: A Phase III Randomized Controlled Trial. Plast Reconstr Surg - Glob Open. 2021;147(5):1189-1198. [CrossRef]

- Michael S, Winters C, Khan M. Acellular Fish Skin Graft Use for Diabetic Lower Extremity Wound Healing: A Retrospective Study of 58 Ulcerations and a Literature Review. Wounds. 2019;31(10):262-268.

- Wallner C, Holtermann J, Drysch M, et al. The Use of Intact Fish Skin as a Novel Treatment Method for Deep Dermal Burns Following Enzymatic Debridement: A Retrospective Case-Control Study. Eur Burn J. 2022;3(1):43-55. [CrossRef]

- Yan Y, Jiang W, Spinetti T, et al. Omega-3 Fatty Acids Prevent Inflammation and Metabolic Disorder through Inhibition of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Immunity. 2013;38(6):1154-1163. [CrossRef]

- Baldursson BT, Kjartansson H, Konrádsdóttir F, Gudnason P, Sigurjonsson GF, Lund SH. Healing Rate and Autoimmune Safety of Full-Thickness Wounds Treated With Fish Skin Acellular Dermal Matrix Versus Porcine Small-Intestine Submucosa: A Noninferiority Study.

- Dorweiler B, Trinh TT, Dünschede F, et al. The marine Omega3 wound matrix for treatment of complicated wounds: A multicenter experience report. Gefässchirurgie. 2018;23(S2):46-55. [CrossRef]

- Luze H, Nischwitz SP, Smolle C, Zrim R, Kamolz LP. The Use of Acellular Fish Skin Grafts in Burn Wound Management—A Systematic Review. Medicina (Mex). 2022;58(7):912. [CrossRef]

- Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman DM, Greenfield S, Steinberg E. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. National Academies Press (US); 2011.

- Varga-Atkins T, McIssac J, Willis I. Focus Group meets Nominal Group Technique: an effective combination for student evaluation? Innov Educ Teach Int. 2017;54(4):289-300. [CrossRef]

- Badois N, Bauër P, Cheron M, et al. Acellular fish skin matrix on thin-skin graft donor sites: a preliminary study. J Wound Care. 2019;28(9):624-628. [CrossRef]

- Radzikowska-Büchner E, Łopuszyńska I, Flieger W, Tobiasz M, Maciejewski R, Flieger J. An Overview of Recent Developments in the Management of Burn Injuries. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(22):16357. [CrossRef]

- Burgess M, Valdera F, Varon D, Kankuri E, Nuutila K. The Immune and Regenerative Response to Burn Injury. Cells. 2022;11(19):3073. [CrossRef]

- Papini R. Management of burn injuries of various depths. BMJ. 2004;329(7458):158-160. [CrossRef]

- Alam K, Jeffery SLA. Acellular Fish Skin Grafts for Management of Split Thickness Donor Sites and Partial Thickness Burns: A Case Series. Mil Med. 2019;184(Supplement_1):16-20. [CrossRef]

- Staubach R, Glosse H, Loff S. The Use of Fish Skin Grafts in Children as a New Treatment of Deep Dermal Burns—Case Series with Follow-Up after 2 Years and Measurement of Elasticity as an Objective Scar Evaluation. J Clin Med. 2024;13(8):2389. [CrossRef]

- Schaefer T, Szymanski K. Burn Evaluation and Management. StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Schaefer T, Nunez Lopez O. Burn Resuscitation and Management. StatPearls Publ. Published online January 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430795/.

- Jeschke MG, van Baar ME, Choudhry MA, Chung KK, Gibran NS, Logsetty S. Burn injury. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2020;6(1):11. [CrossRef]

- Freund G, Schaefer B, Beier J, A Boos. Individualized surgical treatment using decellularized fish skin transplantation after enzymatic debridement: a two years retrospective analysis. JPRAS Open. 2024;43:79-91. [CrossRef]

- Stone R, Saathoff EC, Larson DA, et al. Comparison of Intact Fish Skin Graft and Allograft as Temporary Coverage for Full-Thickness Burns: A Non-Inferiority Study. Biomedicines. 2024;12(3):680. [CrossRef]

- Shupp J, McLawhorn M, Moffatt L. Fish Skin Compared to Cadaver Skin as a Temporary Coverage and Wound Bed Preparation for Full Thickness Burns: An Early Feasibility Trial. J Burn Care Res. 42:S124-S124. [CrossRef]

- Kerecis Confidental Internal Report. MedStar FDA. IDE Study. 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).