1. Introduction

The gut microbiota is crucial in maintaining the organism's homeostasis. The imbalance of the latter induces an alteration in the functioning of the immune system, which promotes the development of certain pathologies such as allergies, chronic inflammatory diseases, and intestinal infections [

1,

2]. The causes of this dysbiosis are complex and probably attributable to several factors such as the environment, genetics, and diet. Indeed, its modulation through diet can be a key factor in ensuring and restoring its balance and consequently maintaining the host's health and well-being. For this reason, researchers are very interested in biological products such as beneficial bacteria, primarily probiotics. These are living microorganisms that, when administered in adequate quantities, would have a beneficial effect on the host's health [

3].

These are often praised for their beneficial effects on health, as well as their ability to influence diseases such as cancer and obesity, which are associated with imbalances in the gut flora [

4]. The effectiveness of these is mainly linked to the selection of the species and even the specific bacterial strain. According to Yadav and Shukla [

5], lactic acid bacteria (LAB) stand out among the selected live bacterial strains for their crucial role in maintaining intestinal balance [

6]. Due to their numerous health benefits, lactic acid bacteria are considered promising probiotic candidates. However, it is necessary to emphasize that not all bacteria can be considered probiotics, and it is essential to examine their probiotic properties as well as their safety. These microbes should have considerable resistance to persist in the stomach’s highly acidic conditions [

7]. Furthermore, their ability to adhere in the gastrointestinal tract (intestinal mucosa and epithelial cells) prevents their elimination by intestinal motility. This adhesion allows them to reproduce, colonize, and affect the immune system, while competitively eliminating pathogens [

8].

This ability demonstrates their aptitude for food bioconservation and can be used as starter culture in the fermentation process under controlled conditions. During fermentation, LAB synthesize a number of compounds, such as exopolysaccharides, aromatic compounds, organic acids, etc., which extend the shelf life of the food and improve its sanitary, sensory, and nutritional properties, as well as increase the antioxidant capacity of the fermented food. This increase is mainly due to the depolymerization of phenolic compounds [

9]. Therefore, the valorization and investigation of probiotic potential of LAB isolated from various local fermented foods and products have awakened scientific interest in recent years. Fermented wheat, which is one of the food substrates stimulating their development, appears as a promising resource. It provides a natural support for the separation and analysis of LAB.

In Algeria, Hamoum, a traditionally fermented wheat, is naturally produced in an underground silo known as Matmora [

10]. In addition to its sensory and gustatory attributes, fermentation enhances the nutritional properties of wheat and stimulates the multiplication of beneficial microorganisms. According to Nithya et al. [

11], fermented wheat is recognized for its preventive virtues against intestinal pathophysiological dysfunctions. Lactic bacteria derived from fermented wheat could represent a promising solution commonly used in the medical and food sectors. In this context, the present study focuses on the identification of three selected LAB isolates obtained from traditional Algerian fermented wheat, as well as the in vitro evaluation of their probiotic, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolates

Three bacterial isolates were obtained from traditional fermented wheat, harvested in Rahwia,Tiaret region (Algeria). The pure culture isolates, previously stored at -20 °C, were transferred into deMan, Rogosa, Sharpe (MRS) broth and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, either under aerobic conditions (LB1, LB2) or under anaerobic conditions (LB3).

2.2. Pathogenic Strains

The strains used for the evaluation of antibacterial activity are Escherichia coli (E.coli) ATCC 10536, Bacillus subtilis (B.subtilis) ATCC 6633, and Bacillus cereus (B.cereus) ATCC 10876, and Staphylococcus aureus (S.aureus) ATCC6528 provided by SAIDAL and the Mostapha Bacha Hospital in Algiers, as well as an isolate of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) from a canine infection at the Veterinary Institute of Tiaret.

2.3. Phenotypic Identification of the Isolates

Morphological properties of the three strains were examined on MRS agar following 24 hours of incubation [

12]. The catalase test and the fermentation type were evaluated according to the method described by Delarass [

13]. Proliferation at various temperatures was recorded in MRS broth following incubation at 10°C, 30°C, and 45°C for 72 hours [

14]. The resistance of bacterial isolates to NaCl was assessed in MRS broth with 6.5% and 9.5% NaCl at 30 °C for 48 hours [

15].

2.4. Molecular Identification of Bacteria Using 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

The genomic DNA of LAB isolates from traditional Algerian fermented wheat was extracted according to the optimized protocol at the Laboratory of Biotechnology and Bio-Geo- Resource Valorization. Higher institute of Biotechnology Sidi Thabet, Tunis, using the phenol-chloroform technique. The amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene were carried out utilizing universal primers (27f 5'AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG 3' and 1492R 5' GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT3'). One microliter of extracted DNA was diluted to 1/10 and added to the reaction mixture comprising 2.5µL of PCR reaction (10×), 0.2 µL of deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates, 0.3 µL primer, and 0.2 µL of DNA polymerase, then adjusted to 25 µL with distilled water. PCR reactions were done on a thermocycler (T100 BIO RAD, USA) utilizing this program: hybridization at 95 °C for 3 min, this was succeeded by denaturation at 95°C for 30 s (35 cycles), the protocol was then continued with hybridization step at 57.5°C for 1 minute, 1 minute of elongation at 72°C, and conducted with 10 minutes of elongation cycle.

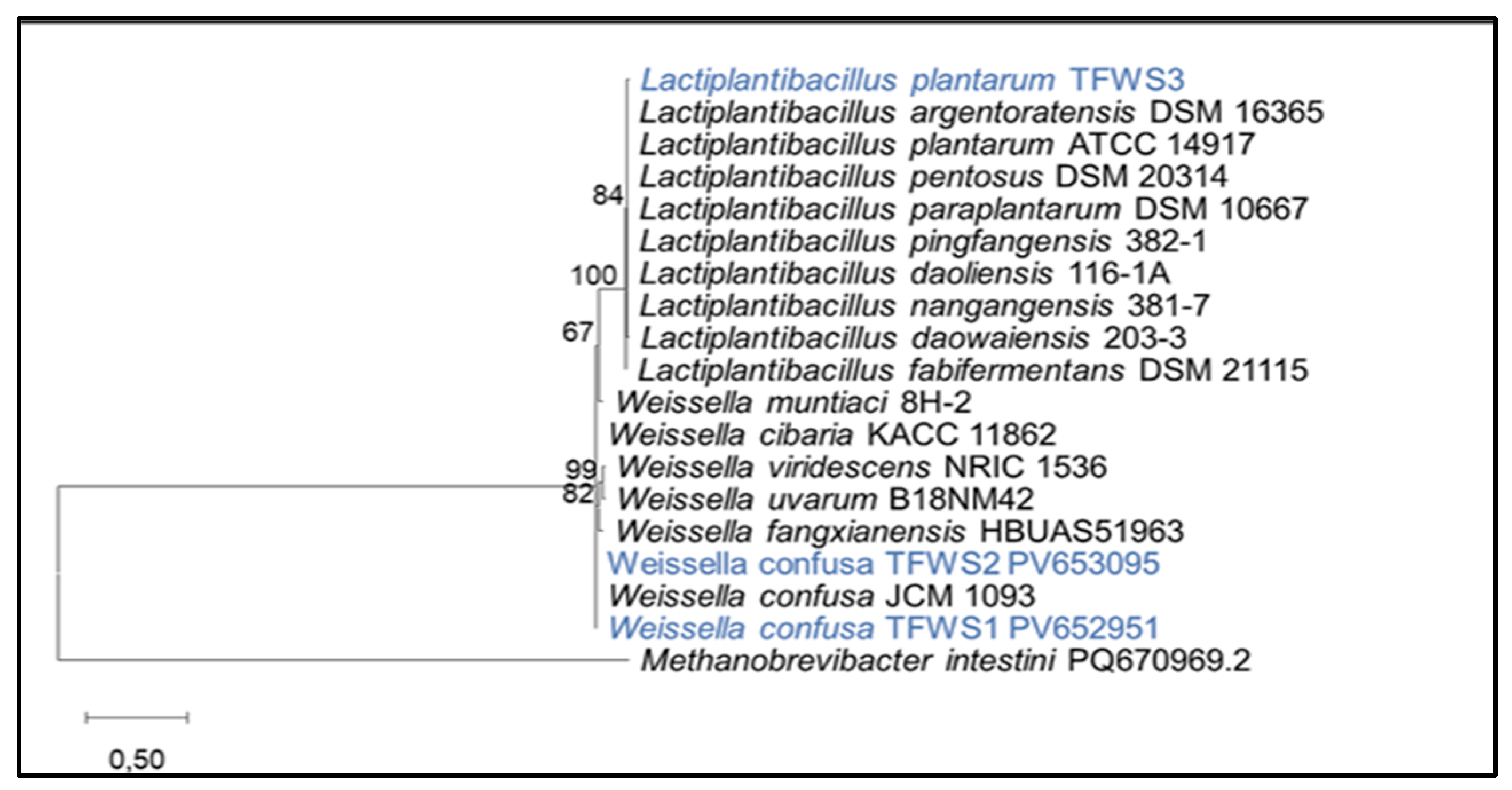

Sequencing was performed using the automated Sanger technique. The sequence obtained from the gene coding for 16S rRNA was compared with the homologous sequences of reference microbial species listed in Genbank, using BLAST NCBI (

http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). An evolutionary tree was also developed using MEGA 11 software to identify the most similar bacterial species using the neighbor-joining method [

16]. The nucleotide sequences have been added in the GenBank with accession numbers PV652951, PV653095, and PV653185 for the isolated bacteria LB1, LB2, and LB3, respectively.

2.5. Probiotic Properties Assessment

2.5.1. Tolerance to Acidity

The tolerance of the strains to acidity was performed according to Anandharaj et al. [

17] MRS medium was calibrate to pH 3 and pH 6.5, inoculated with overnight cultures, and incubated at 37°C. The growth was established over 3 h. The survival rate (%) was determined using the pour plate count method on MRS agar after incubation of 0 and 3 h.

2.5.2. Bile Salts Tolerance

The resistance ability of strains to bile salt was carried out by the method of Anandharaj et al [

17]. The MRS medium supplemented with 0.3% (w/v) bile salts were inoculated with 18h culture of bacterial isolates (10

8 CFU/ml) and the incubation was carried out at 37°C. The viability rate (%) was assessed utilizing the colony counting technique on MRS agar after incubation of 0 and 4 h.

2.5.3. Antibiotic Sensitivity

Antibiotic sensitivity of strains was determined according to Tarique et al. [

18]. The bacterial suspensions of each isolate regulated to 10

6 CFU/ml were introduced and kept at 37°C for incubation after the placement of antibiotic discs. The inhibition diameters were evaluated follwing this classification, resistant less than 1.5 cm, intermediate between 1.6 and 2.0 cm, sensitive more than 2.0 cm) [

19].

2.5.4. Auto-Aggregation

The surface cell auto-aggregation was carried out by the modified protocol of Abdulla et al. [

20]. The overnight cultures of bacterial isolates were subjected to centrifugation for 15 minutes at 4500 g (4°C), then rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2) and regulated to 10

8 CFU/ml (A

0). A volume of 4 ml of suspended cells were mixed, maintained at 37°C for 3 h incubation, and the absorbance of the supernatant was determined at 625 nm (A1). The percentage of bacterial cells auto-aggregation was measured with the following equation (1):

A1 is absorbance at 3h and A0 is absorbance at 0 h.

2.5.5. Co-Aggregation

The co-aggregation rates between the isolated strains and two pathogenic bacteria (

S. aureus and

E.coli) were performed by the protocol of Abushelaibi et

al. [

21]. The same volume of lactic and pathogenic strains suspensions were mixed, vortexed, and then subjedted to 3 hours of incubation at 37°C. The absorbance of the selected LAB strains (Ax), the pathogenic strains (Ay), and the mixture [A(x+y)] was recorded at 620 nm. The rate of co-aggregation was measured with the formula (2):

Where AX0 : Absorbance in the presence of LAB strain at 0h; AY0; absorbance in the presence of pathogenic bacteria at 0 h; A(x+y): Absorbance of the mixture after 3h of incubation).

2.5.6. Hemolytic Activity

The bacterial cultures were streaked on the surface of horse blood agar (5% v/v) and incubated for 48 h at 37°C. The degradation of the blood was noted by the formation of distinct halos (β hemolysis) or greenish areas (α hemolysis) surrounding the colonies [

22].

2.5.7. Proteolytic Activity

The proteolytic property of the strains was relaized by the disc technique on MRS agar containing 10% skim milk. Discs impregnated with 15 μL of each bacterial culture were placed on the agar, then incubated at 30 °C and 37 °C for 24 h. The diameters of the hydrolysis zones were measured to classify proteolytic activity: very high for a halo greater than 10 mm, moderate for a halo of 3 to 10 mm, and low for a halo less than 3 mm [

23].

2.6. Evaluation of the Biological Activity of LAB Isolates

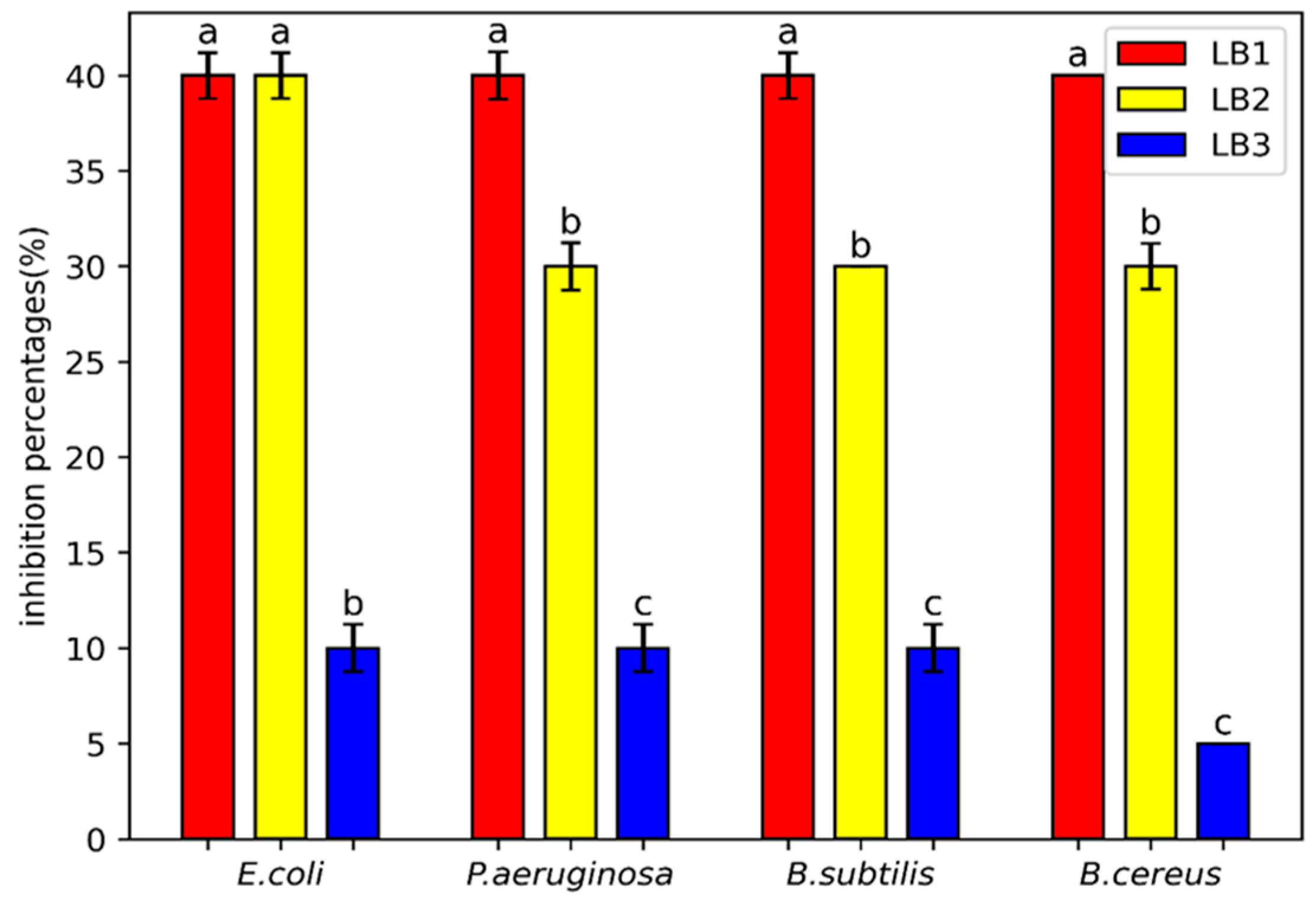

2.6.1. Determination of Minimum Inhibition Percentages by Using Microdilution Method

Supernatants of bacterial isolates, diluted to different concentrations, were then deposited in the wells of a microplate, with 100µl of each generated concentration. Each well was inoculated with 10

6 CFU/ml of a suspension of pathogenic bacteria. The wells in the first row of the same microplate received Mueller Hinton medium inoculated with the same concentration of bacteria and without supernatant. The prepared microplates underwent to 21 hours of incubation at 37°C. After incubation, 20 μl of 2,3,5 triphenyltetrazolium was added to observe the bacterial proliferation.The minimum percentage of inhibition (I%) was determined from the first well without bacterial growth [

24].

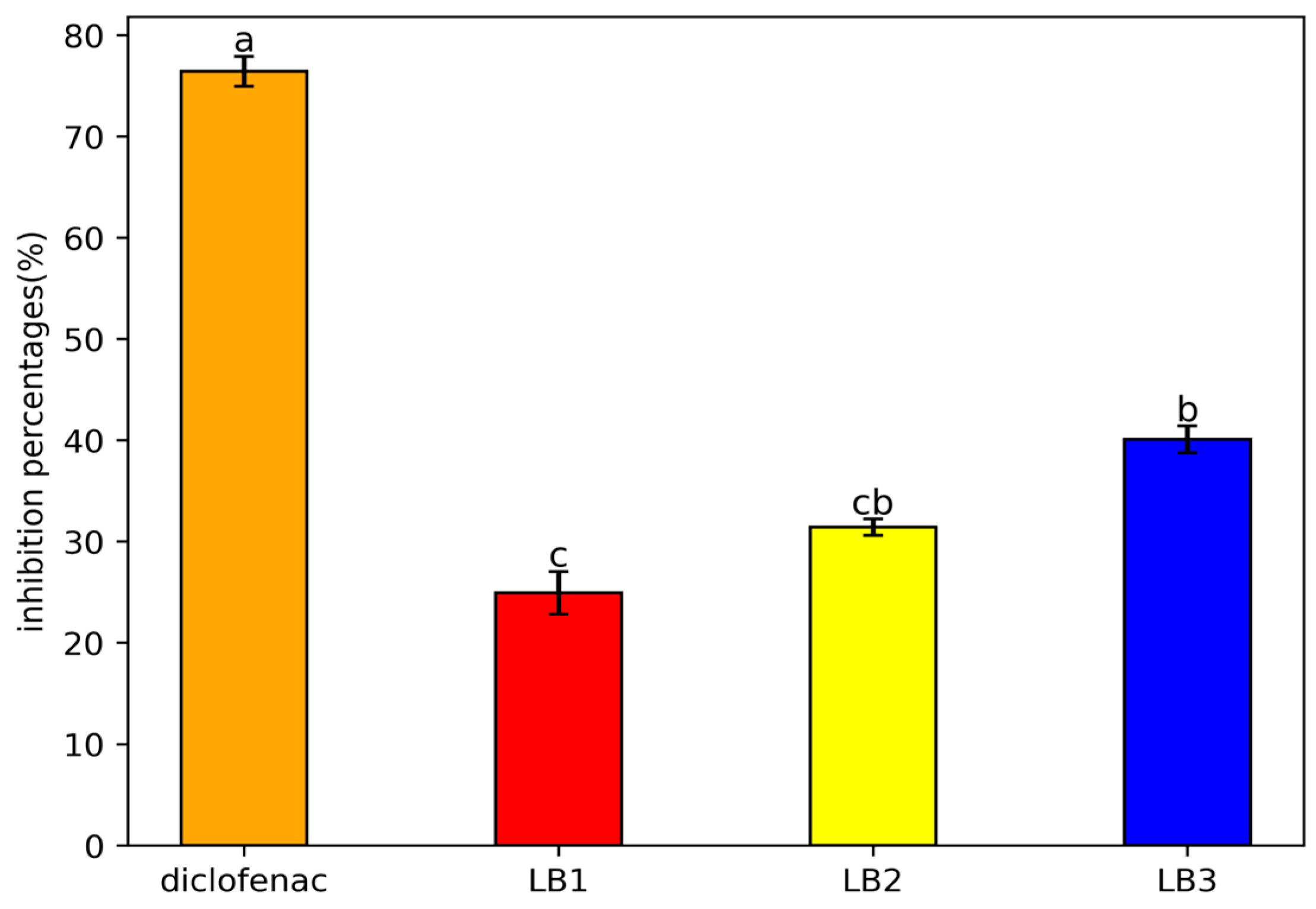

2.6.2. Assessment of Anti-Inflammatory Property

The anti-inflammatory property of the LAB isolates was carried out according to Kar et al. [

25]. Overnight cultures of each bacterial isolate were prepared. After centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, the bacterial cell pellets were subjected to three successive washes with 500μl of sterile PBS (20mM, pH=7.4). The latter were reconstituted in 500 μl of the same buffer. The total number of cells was adjusted to 10

9 CFU/ml (OD≈1.2) [

26]. The capacity to inhibit protein denaturation was carried out by preparing three solutions: Test solution 1: composed of 450μl of BSA (at 5% v/v) and 50μl of bacterial suspension; Solution 2: composed of 450μl of BSA and 50μl of bidistilled water as a control; Solution 3: includes 450μl of BSA and 50μl of sodium diclofenac (100 mg/mL). After adjusting each solution to pH 6.3, they were incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C and then subjected to 75°C for 3 minutes. The absorbance was determined after cooling process, and the formula (3) was used to evaluate the rate of protein denaturation inhibition.

Where A1 is absorbance test solution and A2 is absorbance of positive control

2.6.3. Evaluation of Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP)

This test was decribed by Benzie and Strain [

27], uses solution prepared from acetate buffer at pH 3.6, 10 mM 2,4,6 -Tris(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine, and 20 mM FeCl

3, all was subjected to 37°C of incubation. After that, a volume of 100 μL of each solution was adjusted to 900 µL of the FRAP solution and kept at room temperature for 30 min of incubation.The concentration of ferric-reducing power for each bacterial suspension was calculated using a calibration curve performed with FeSO4.

2.6.4. Evaluation of 2,2-diphényl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH•) Scavenging

This method is evaluated according to the protocol described by Sanchez-Moreno et al. [

28]. A volume of 750 μl of each bacterial suspension was added to 750 μL of the methanolic DPPH• solution at 4 mg/mL. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature and in the dark for 50 min, then the absorbance was measured at 517 nm. The ability of the bacterial isolates to scavenge DPPH• was expressed as a percentage of inhibition, calculated using the following equation (4):

where A

1 : absorbance of the control; A

2 : absorbance of the sample.

2.6.5. Lipid Peroxidation Evaluation

The evaluation of lipid peroxidation was performed by the protocol of Bekkouche et al. [

29]. 160 μL of bacterial suspensions, 40 μL of copper sulfate solution (CuSO4 at 0.33 mg/mL), and 160 μL of human plasma were combined and underwent to 50 °C of incubation for 12 hours. Two controls were used: negative control (160 μL of plasma + 160 μL of distilled water) and a positive control (160 μL of plasma + 160 μL of distilled water + 40 μL of CuSO4). After 12 h of incubation, 200 mL of the reaction solution was added to 800 μL of a thiobarbituric acid mixture (0.375% (w/v)), trichloroacetic acid (20%), 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (0.01%), and HCl (1N) (20%) and subjected to 15 minutes of incubation at 100°C. After cooling, 2 mL of butanol-1 was used to extract the complex that had formed. After centrifugation at 4000 rpm during 10 minutes, the absorbance was read at 532 nm. Malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration was determined utilizing 1,3,3-tetraethoxypropane curve , and MDA inhibition rate was evaluated using the equation (5):

Where A0 : MDA concentration of the positive control; A1 : MDA concentration of the sample.

2.6.6. Determination of Reduced Glutathione (GSH) Levels

Preparation of intracellular extracts of LAB isolates

According to Su et al. [

26] modified, overnight cultures of each bacterial isolate were centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4 °C, the cells were rinsed three times with sterile PBS, then adjusted to 10⁸ CFU/ml. Cell suspensions were subjected to ultrasonic disruption. Sonication was conducted for five intervals of one minute each in an ice bath. Cell debris was eliminated using centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4°C, and the resultant intracellular extracts were utilized to quantify total proteins and GSH.

GSH Assay

500 μL of intracellular extract from bacterial isolates were mixed to 750 μL of PBS (0.05N, pH 8) and 250 μL of Ellman's reagent. The mixture was kept 15 minutes at room temperature. The optical density reading was performed at 412 nm. The concentration of GSH was determined using a calibration curve of reduced GSH.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the means followed by the Tukey test (p<0.05) using 8 version of the Statistica software, published by Statsoft in Tulsa, Oklahoma. All data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SE).

4. Discussion

This study aims to identify phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of certain lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditional Algerian fermented wheat and to investigate their probiotic and biological properties. The obtained results regarding the phenotypic characteristics of the bacterial isolates coded LB1, LB2 confirm the phenotypic identification characteristics of

Weissella, and for the isolate coded LB3, affirm its belonging to the genus

Lactobacillus. These are identical to the main identification characteristics presented by Kandler and Weiss [

30]. Moreover, the results of 16S rRNA gene sequencing confirmed that these bacteria belong to the two genera, namely

Weissella and

Lactobacillus. The genera we identified in our samples corroborate with those of Tahlaïti et al. [

31], as well as Chadli et al. [

32], who studied the molecular identification of LAB derived from Algerian Hamoum. These authors found that most of the isolates belong to,

Leuconostoc Pediococcus,

Lactobacillus, and

Enterococcus.

The resistance of bacterial isolates to acidic pH can be attributed to their ability to produce acids and other metabolites that stabilize their environment. This tolerance is reinforced by internal pH regulation mechanisms, such as proton exchange, allowing lactobacilli to survive in an acidic environment [

33]. These findings are consistent with previous studies, which have demonstrated that

Lb. plantarum,

Weissella confusa, and

Weissella cibaria have high survival rate in acidic environment [

31,

34]. We also noticed the tolerance of these bacteria to bile salts (0.3%). These results corroborate with those obtained by Angelescu et al. [

35] and Chadli et al. [

32], who observed strong survival rates of LAB in the presence of bile salts.

The high auto-aggregation of the three strains can be attributed to several factors, including the production of polysaccharides, electrostatic interactions between surface charges, as well as Van der Waals forces and hydrophobic bonds [

36]. Anandharaj et al. [

17] reported that

Lactobacillus and

Weissella sp. exhibit auto-aggregation rates between 18 and 79%. Similarly, the significant co-aggregation capacity between probiotic bacteria and Gram-positive pathogens is explained by their morphological similarity, particularly the presence of peptidoglycan and their hydrophobic nature [

37]. This co-aggregation allows probiotics to release antimicrobial agents near pathogens, creating a hostile environment that inhibits their growth [

33]. Furthermore, the results of the proteolytic activity corroborate with those obtained by N’tcha et al. [

38], who revealed that

Lb. fermentum,

Lb. casei,

Leuconostoc mesenteroides,

and Streptococcus thermophilus exhibit proteolytic activity, with proteolysis diameters ranging between 24 ± 5.30 mm and 27.5 ± 10.61 mm.

On the other hand, the findings of the antibacterial property of the LAB isolates are in agreement with those of Tahlaiti et al. [

31], who revealed that the lactic strains

Lb. plantarum (M6, R27),

Lb. brevis (BL8), and

Pediococcus acidilactici (M54) from Algerian fermented wheat (Hamoum) exhibit high efficacy effect on

E. coli,

P. aeruginosa and

S.aureus. This result could be attributed to the synthesis of antibacterial metabolites particularly bacteriocins ,organic acids and hydrogen peroxide [

39] as well as exopolysaccharides (EPS) [

40]. Also, it is observed that protein denaturation, related to inflammation, is influenced by lactic acid bacteria, whose protective capacity varies according to the strains and the bioactive molecules produced. Studies, such as those by Khan et al. [

40] and Jain and Mahta [

41], showed that strains such as

Lb. agilis,

Lb. casei, and

Enterococcus faecium inhibit the denaturation of bovine serum albumin, with significant anti-inflammatory effects.

At the same time, the results of the antioxidant activity reveal that the LAB isolates exhibit significant antioxidant activity. This is reflected by a strong ability to scavenge the DPPH° radical, a power to reduce iron, an inhibition of lipid peroxidation, and a capacity to produce GSH. Indeed, these isolates exhibit a DPPH° scavenging capacity comparable to that reported by Riane et al. [

42] for lactic strains isolated from fermented milk (72% to 83%). Our results are also similar to those of Duz et al. [

43], these authors observed a maximum activity of 90.34 ± 0.40% for the

Lb. plantarum IH14L strain. Previous studies have notably shown that the antioxidant activity of certain

Lactobacillus species (

Lb. rhamnosus,

Lb. helveticus,

Lb. sakei, and

Lb. plantarum) is linked to the production of EPS on the cell surface [

44]. EPS could trap free radicals by releasing active hydrogen or by combining with them to form stable compounds, and they also possess iron-reducing capacity [

45]. At the same time, the results of plasma lipid peroxidation inhibition are similar to those of Lin and Chang [

46], who exhibited that

Bifidobacterium longum and

Lb. acidophilus inhibit the plasma lipid peroxidation with rates ranging from 11 to 29%. Another study conducted by Zhang et al. [

47] revealed that lactic acid bacteria exert an antioxidant activity against lipid oxidation by inducing the expression of antioxidant genes using adaptive mechanisms, particularly by chelating transition metals, which promote the formation of free radicals and lipid peroxidation. EPS are also involved in inhibiting the formation of MDA. According to the research done by Li et al. [

46], the EPS of

Lb. plantarum LP6 have the ability to enhance antioxidant enzymatic activities, maintain cellular integrity, and inhibit lipid oxidation of PC12 cells exposed to H

2O

2. Also, the inhibitory effect on MDA formation by lactic acid bacteria related to particular constituents to each bacterium, such as GSH, antioxidant enzymes, vitamins, amino acids, etc., and the different associated redox reactions [

48].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B. and R.B.; methodology, R.B.; software, D.B.; validation, R.B., H.C. and C.A.; formal analysis, C.F.; investigation, D.B.,F.B. and C.F; resources, R.B. and C.A.; data curation, R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.B., R.B., D.B., and F.B; writing—review and editing, R.B. and H.C.; visualization, R.B.; supervision, C.A.; project administration, R.B. and R.B.; funding acquisition, R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.