1. Introduction

The practical significance of magnesian rocks and their processing products is determined by their broad applicability across various industrial sectors. Among magnesium compounds, magnesium hydroxide is one of the most widely used and in-demand materials. It is utilized as a flame retardant in the production of thermoplastics and polymer composites, as a flocculant in the treatment of natural and industrial wastewater, and in chemical, pharmaceutical, and other industries.

Currently, synthetic magnesium hydroxide is typically produced via a “wet” process, which involves the interaction of aqueous solutions of magnesium salts (MgCl2, MgSO4) with sodium hydroxide, followed by precipitation, filtration, washing, drying, and grinding of the product. In addition, surface modification of synthetic magnesium hydroxide may be performed during the drying and grinding stages.

The quality of magnesium hydroxide obtained through the hydrochemical processing of enriched mineral raw materials is generally higher than that of the product derived directly from natural minerals such as brucite or dolomite. This is attributed to the fact that hydrochemical precipitation processes allow for purification stages of both solutions and suspensions. Serpentinite rocks are a promising source of magnesium due to their abundance; however, their industrial application remains limited owing to the absence of cost-effective processing technologies.

Over the past decades, numerous technologies for serpentinite processing have been developed. Most of these are based on chemical methods, including acid leaching (using sulfuric, hydrochloric, or nitric acid), sintering, as well as neutralization and purification techniques. Studies have shown that sulfuric acid ensures high availability and magnesium extraction efficiency (85–90%) [

1]. Hydrochloric acid demonstrates even higher selectivity, achieving yields exceeding 90% [

2]. However, despite this advantage, the resulting magnesium nitrate solution is difficult to utilize and is associated with high processing costs [

3]. Preliminary thermal activation of serpentinite [

4] has been shown to improve leaching efficiency by 20–30% in acid-based methods.

A considerable number of studies have focused on the decarbonization of serpentinite using various leaching agents [

5,

6,

7]. However, these proposals have not yet found practical application due to technological, economic, or environmental limitations.

The purification stage of magnesium-containing process solutions is one of the most critical steps in technologies based on acid processing of serpentinite [

8,

9]. For example, to obtain high-purity Mg(OH)

2, it is essential to effectively purify the process solution prior to precipitation.

During acid leaching, in addition to Mg2+, undesirable impurities such as Fe3+, Al3+, Ca2+, and colloidal silica (SiO2·H2O) also enter the solution. The first three are typically co-precipitated as hydroxides (e.g., Mg(OH)2), while colloidal silica complicates filtration and reduces the yield and purity of magnesium sulfate and subsequently magnesium hydroxide. Therefore, the purification of magnesium-containing solutions plays a crucial role in the process and significantly affects its economic efficiency.

In most known studies on the neutralization and purification of process solutions, stepwise precipitation methods for the hydroxides of impurity metals (Fe3+, Al3+, Ni2+, etc.) have been proposed by increasing the pH (e.g., to 5–6). Reagents such as NaOH, Na2CO3, Ca(OH)2, and MgO are used. Each of these methods has characteristic disadvantages, including an increased number of process steps, co-precipitation losses of magnesium, and the limited availability of MgO, which negatively affect technological and economic indicators.

Recent studies [

3,

8] have shown that the H

2SO

4-leaching → purification of thermally activated serpentinite → NaOH neutralization scheme enables the production of Mg(OH)

2 with a purity of up to 97% and improved properties. Additionally, the process solution is purified more efficiently due to acid–base interactions between TA-SP and the acidic suspension medium.

In [

9], high sorption purification efficiency was demonstrated when using thermally activated serpentinite. These and other findings formed the basis for the ion-exchange-based process proposed in this study for the production of magnesium hydroxide from serpentinite.

The relevance of this study is due to the fact that in Kazakhstan, serpentinite (Zhitikarinskoe deposit) is considered a promising alternative source of magnesium for the production of its compounds [

10]. High-quality dolomite deposits have not been identified in the country. Over 65 years of operation of the Zhitikarinskoe deposit have resulted in the accumulation of large amounts of tailings (hundreds of millions of tons) from chrysotile ore processing.

Based on the above, the aim of this study is to investigate the technological processes for obtaining magnesium hydroxide, including the use of thermally activated serpentinite for neutralization and purification of the acidic leach solution prior to the precipitation of the target magnesium hydroxide, as well as to assess how these stages influence the quality of the final product.

2. Materials and Methods

A powdered technogenic waste (PTW) obtained from chrysotile ore processing at the Zhitikarinskoe deposit (AO “Kostanay Minerals”, Kazakhstan) was used as the serpentinite-based material for this study. The PTW is a bluish-gray fibrous powder consisting of fine solid particles free of lumps and large inclusions. It is generated and accumulated in dry dust collection systems during the crushing and fractionation of chrysotile raw material. The elemental composition of the PTW is shown in

Table 1.

Thermal treatment of the PTW was carried out in a muffle furnace at 750°C for 1 hour. It was found that thermal activation contributes to a reduction in particle size, with no fraction larger than 0.9 mm remaining. The predominant fraction (94%) consists of particles within the range of 0.14–0.08–0.07 mm. The thermally treated material was additionally ground before use. The thermally activated PTW is hereinafter referred to as TA-PTW.

All analytical procedures aimed at determining the distribution of elements during leaching and solution purification were performed using a JSM-6490LV scanning electron microscope (JEOL, Japan) equipped with an INCA Energy 350 energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) system. Chemical analysis of the MgSO₄ solution and the final Mg(OH)₂ product was performed using a Varian MS-820 spectrometer.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the PTW and thermally activated PTW (TA-PTW) were obtained using a D8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker), with Cu-Kα radiation at 40 kV and 40 mA. The resulting diffractograms were processed, and interplanar spacings calculated using EVA software. Phase identification was carried out using the Search/Match algorithm with the PDF-2 (JCPDS) powder diffraction database.

Specific surface area and pore size distribution were determined by the Principle: Static Capacity method using a BSD-660S A3 instrument (Zone-Test, Degas→Temp Zone).

The methodologies for acid leaching and Mg(OH)₂ precipitation are provided in the Results and Discussion section for clarity and continuity of presentation.

3. Results and Discussion

The proposed technology for producing magnesium hydroxide from serpentinite is described by the following key chemical reactions:

The process includes the following stages: leaching of serpentinite material with sulfuric acid; neutralization and purification of the resulting sulfate solution using thermally activated serpentinite (TA-SP) at 750°C (for 1 hour); and precipitation of magnesium hydroxide from the purified magnesium sulfate solution using sodium hydroxide (NaOH) as the precipitating agent.

Leaching of PTW with Sulfuric Acid and Production of MgSO4. The reaction mixture of PTW and sulfuric acid was prepared based on the following proposed chemical equation:

Accordingly, the following molar ratio of reagents was selected for the experiment:

1.000 mol : 1.046 mol : 1.000 mol

A slight excess of acid was introduced to account for the presence of impurity metals in the PTW.

The leaching process of the PTW with sulfuric acid was carried out in a three-neck round-bottom flask equipped with a thermometer, reflux condenser, sampling port, and mechanical stirrer.

Into the reaction flask, 500 g of PTW and 1000 cm³ of water were loaded. While stirring (200–300 rpm), 415 cm³ of 92% H2SO4 (density 1.824 g/cm³) was added in portions (150–200 cm3 each) from a dropping funnel to the suspension (PTW + H2O). The total weight of the reaction mixture was 2256 g, with a liquid-to-solid ratio of 4.5:1. The stoichiometric amount of H2SO4 (SNK) calculated based on the Mg2+ content in the PTW was 1.046:1.

Upon the addition of acid, the mixture heated up, and within 2–3 minutes the temperature reached 100–105°C, which significantly intensified bubbling and suspension boiling. Therefore, the interval between acid additions was reduced to ensure moderate effervescence.

As a result, a thick suspension of bluish-gray color was formed. The measured pH value was 0.57. The leaching process was conducted over 3 hours. Samples (10 mL each) were taken at 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes for chemical analysis. The suspension was filtered, the precipitates were rinsed with a small amount of water, and then the filter and solid residue were dried at 105°C to constant weight and subjected to elemental analysis. The magnesium content was additionally monitored using a Varian MS-820 spectrometer.

The analytical results are presented in

Table 2.

Analysis of

Table 2 shows that after just 30 minutes from the start of the leaching process, the majority of elements contained in the PTW had already transitioned into the sulfate solution. Calcium began to appear in the solution only after 60 minutes. No significant concentration changes were observed in the time interval between 30 and 180 minutes: the magnesium content in the solution increased by 12.8%, iron by 17%, while silicon decreased by 5.8%. In the insoluble residue, the magnesium content decreased by 27%, silicon increased by 5.5%, and iron decreased by 17%.

Thus, the primary acid-base interaction between PTW and H2SO4 occurs within the first 30 minutes. During this time, the amount of extractable magnesium sulfate from 100 g of PTW reached 168.65 g (≈70% of the theoretical yield). A key observation is that the mass of magnesium sulfate extracted between 30–180 minutes remains practically unchanged. The obtained values were 168.65 g; 168.90 g; 171.60 g; and 167.68 g, which indicates no need to extend the process duration.

Neutralization and purification of the productive sulfate solution using thermally activated PTW (TA-PTW) at t = 750°C. The next experiment was conducted under the same conditions as the first one. However, considering the results in

Table 2 and the slight increase in the amount of extractable magnesium sulfate between 30 and 180 minutes, the leaching time was limited to 30 minutes. After this period, 1.0dm

3 of distilled water was added to the acidic suspension. Thermally activated PTW (TA-PTW) was used as the neutralizing agent.

Effect of Thermal Treatment on the Structure of PTW. The use of TA-PTW is justified by the fact that thermal activation leads to significant structural changes, including increased porosity and enhanced reactivity of serpentinite [

11]. Dehydroxylation occurs, resulting in the formation of an amorphous phase of silica and magnesium oxide according to the following reaction:

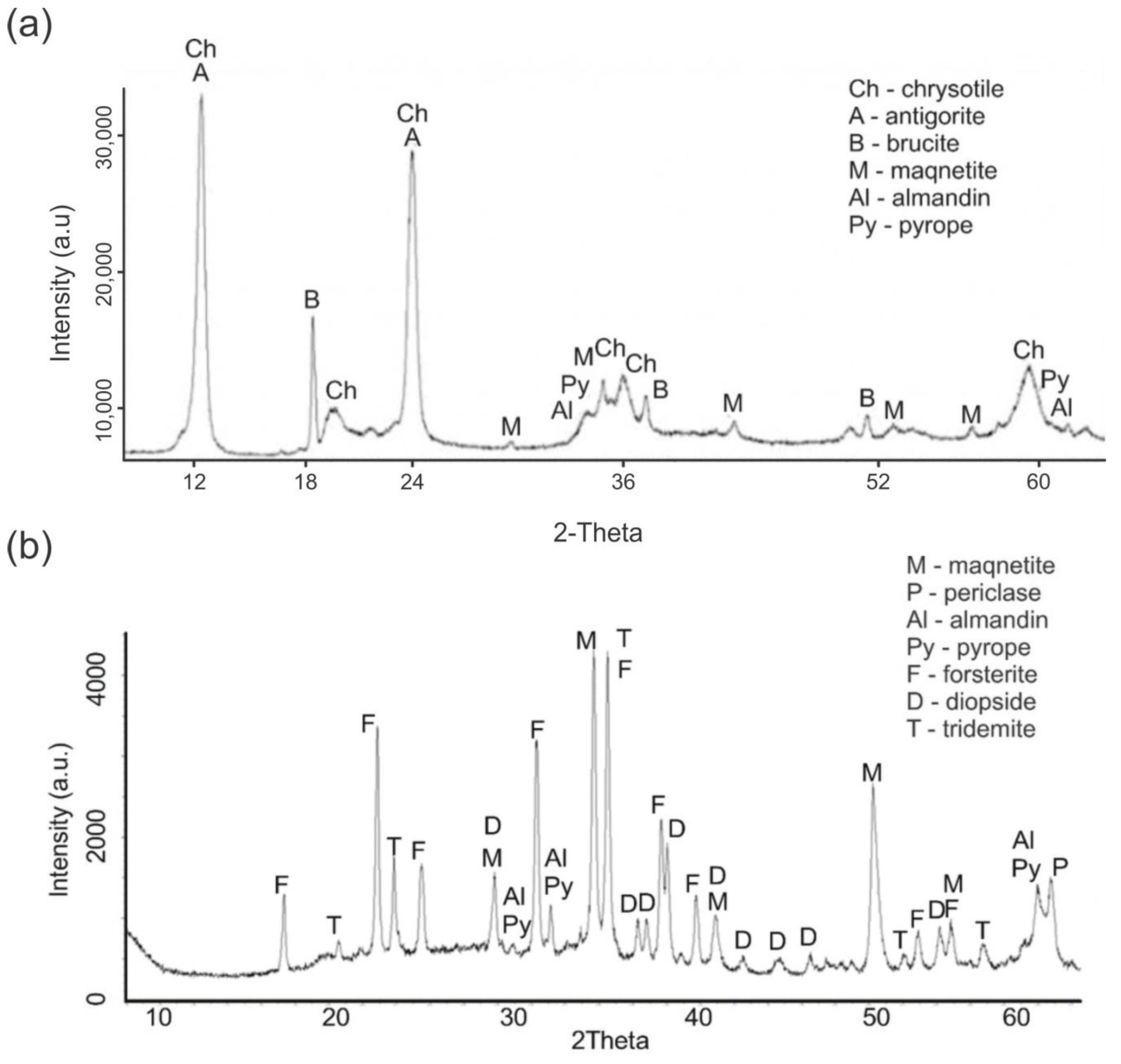

The qualitative change in the phase composition of the original PTW upon thermal treatment at 750°C is shown in

Figure 1 (a and b).

The activation of serpentinite during thermal treatment occurs as a result of internal rearrangement of the serpentinite crystal lattice, leading to the formation of periclase (MgO) (

Figure 1b). This component enhances the alkaline properties of the material [

12] and increases the number of active sites on the surface of TA-PTW particles.

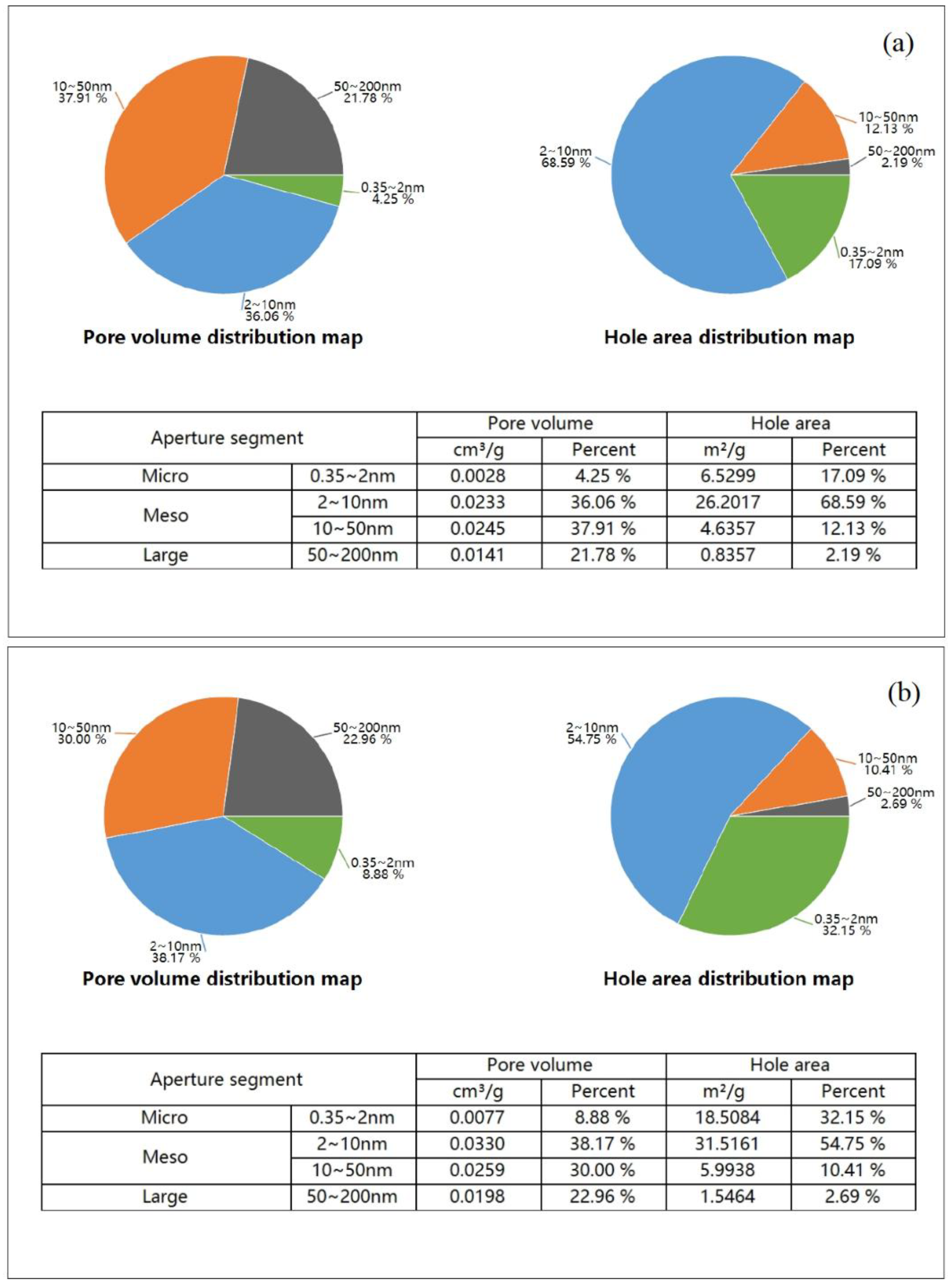

Additional studies on the effect of thermal treatment on the specific surface area of the PTW (

Figure 2) revealed a significant increase in the proportion of micropores (0.35–2.0 nm) in the thermally activated sample (b) compared to the initial PTW (a).

This confirms that TA-PTW exhibits a high adsorption capacity for Fe

3+, Al

3+, and Ca

2+ ions due to its increased surface area and the number of active sites [

9].

Neutralization process. The neutralization of the acidic suspension with TA-PTW was carried out until a pH of 8.3 was reached. The resulting suspension was filtered, and the solid residue was washed twice with 0.5 L of distilled water.

The analytical results for the filtrate and residue after neutralization using TA-PTW are presented in

Table 3.

Analysis of results. At this acidity (pH = 8.3), filtration and washing of the suspension proceeded without difficulty. As shown in

Table 3, the filtrate after neutralization is practically free of Fe

3+, Al

3+, and Si

4+ ions, except for a negligible amount of Ca

2+.

The magnesium sulfate yield after neutralization was 46% of the total magnesium content in the PTW and TA-PTW. At the same time, the magnesium recovery from sulfuric acid reaches 98–100%. The MgSO4 concentration in the first filtrate was 243 g/L (24.3%), and in the repeated leaching of a new batch of PTW (with adjusted acidity), 47–48%.

The residue (OS) after neutralization of TA-PTW contained the following elements, wt%:

The amorphous silica (SiO

2·nH

2O) in the insoluble residues can be used in various industries, for example, as an active mineral additive (microsilica) for high-strength concrete [

8,

9]; as a geopolymers precursor in alkaline activation [

3]; as a soil improver for reclamation of saline soils, and for pH [

2] structure adjustment.

Identified Advantages of Using Thermally Activated PTW as a Neutralizing Agent. The application of thermally activated process tailing waste (TA-PTW) during the neutralization stage offers several advantages over the conventional reagent (NaOH):

1. It enhances the magnesium content in the productive solution due to acid–base interactions between TA-PTW and the acidic medium;

2. It does not introduce extraneous ions into the sulfate solution, unlike alkaline reagents;

3. Owing to its structural and adsorptive properties, TA-PTW enables more effective removal of impurity metal ions (Fe3+, Al3+, etc.), with the exception of minor amounts of Ca2+.

Therefore, the use of TA-PTW provides a high-purity initial magnesium sulfate solution, suitable for subsequent precipitation of magnesium hydroxide.

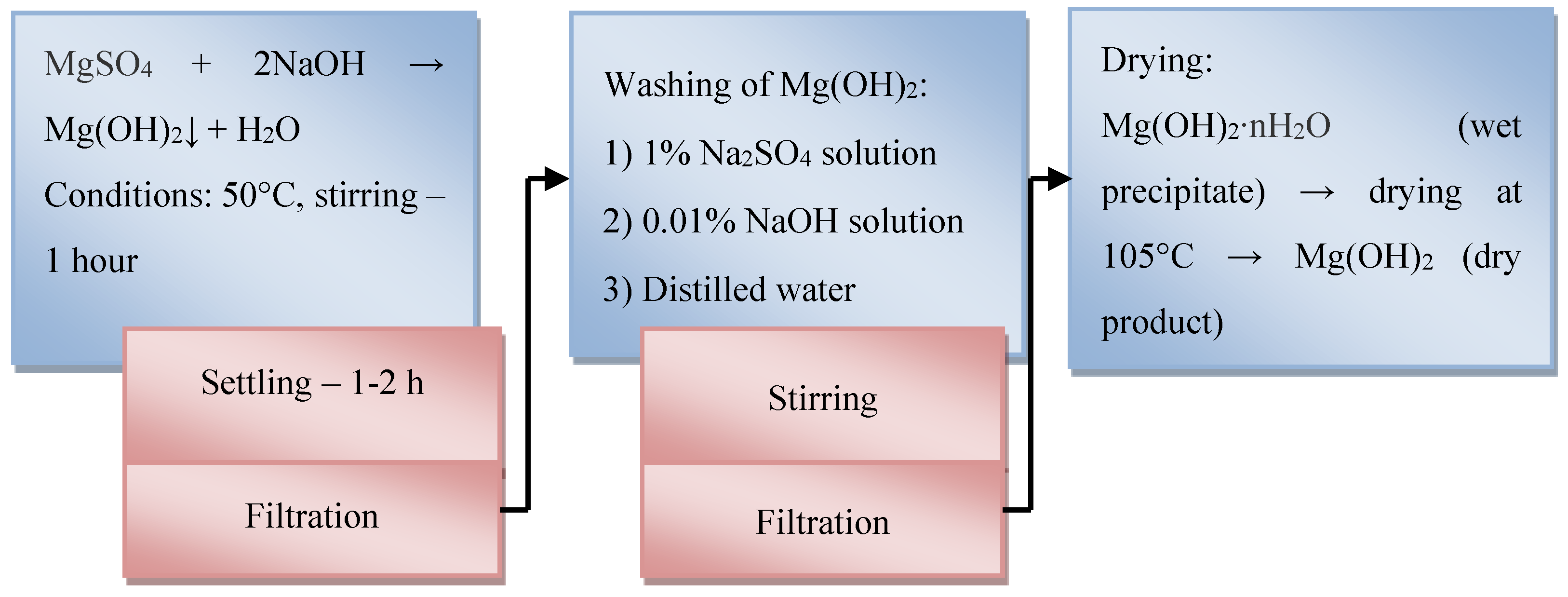

Precipitation of Magnesium Hydroxide (Mg(OH)2). Magnesium hydroxide was precipitated from the purified sulfate solution (MgSO4 concentration: 19–24%). A 25% sodium hydroxide solution was used as the precipitating agent (reagent grade, in accordance with GOST 4328-77).

The precipitation reaction proceeded according to the following equation:

The reagent ratio was determined based on the stoichiometric calculation:

To 250 mL of a 19.5% MgSO4 solution, 82 mL of a 25% NaOH solution was gradually added under stirring. During the reaction, the temperature of the mixture increased to 50°C. At pH = 9.5, turbidity formation began intensively. The precipitation was considered complete at pH = 12.5. The suspension was stirred for 1 hour at low speed and then allowed to settle for decantation and cooling.

After 2 hours, the precipitate was filtered and washed by decantation in the following sequence: three times with a 1% NaCl solution, then with a 0.01% NaOH solution, and finally with distilled water. The yield of magnesium hydroxide after drying at 105°C to constant weight was 26.22 g (98%). Precipitation began at pH = 9.4 and was completed at pH = 12.4. The residual concentration of Mg2+ in the solution after complete precipitation was 10⁻⁵ mol/L.

The process flow diagram for obtaining Mg(OH)

2 from the MgSO

4 solution (filtrate of sulfuric acid leaching) with a concentration of C(MgSO

4) = 19–24%, and indicating the process parameters (precipitation, washing, drying), is presented in

Figure 3.

The resulting Mg(OH)

2 obtained according to the presented scheme (

Figure 3) contains the following (wt.%): Mg – 99.5881; Al – 0.0180; Na – 0.0508; Ca – 0.2251.

The results of chemical analysis indicate that the use of thermally activated PTW (TA-PTW) during the neutralization and purification of the productive sulfate leach solution has a positive effect on the quality characteristics of the resulting magnesium hydroxide. This approach simplifies the technological process and may reduce the number of processing stages and equipment required for removing impurity metal ions from acidic leachates. Overall, it facilitates the production of high-purity magnesium hydroxide from serpentinite.

4. Conclusions

The processes of leaching PTW with sulfuric acid, followed by neutralization and purification of the resulting sulfate solution using thermally activated PTW (TA-PTW), make it possible to obtain magnesium sulfate solutions with high purity and favorable characteristics, thereby facilitating the production of high-purity magnesium hydroxide.

Thermally activated PTW demonstrated higher basicity and enhanced adsorption activity toward impurity metal ions. Its application during the neutralization and purification stages of the productive solution contributed to obtaining high-purity magnesium hydroxide. The positive effect of TA-PTW is also associated with improved textural properties, increased specific surface area, and a greater proportion of micropores in its structure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A., Ch.Y.; methodology, A.A., Ch.Y.; software, A.Zh.; validation, A.I., K.A.; formal analysis, Ch.Y.; investigation, A.I., A.Zh.; resources, K.A., A.I.; data curation, A.Zh.; writing—original draft preparation, Ch.Y.; writing—review and editing, A.A.; visualization, K.A.; supervision, A.A.; project administration, A.A.; funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was carried out with the financial support of the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (BR21882242).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (BR21882242)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SP |

Serpentinite |

| TA-SP |

Thermally activated serpentinite |

| PTW |

Powdered technogenic waste |

| TA-PTW |

Thermally activated PTW |

| SNK |

Stoichiometrically Necessary Amount (of acid) |

| EDS |

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| XRD |

X-ray diffraction |

| M |

magnetite |

| F |

forsterite |

| D |

diopside |

| T |

tridymite |

| Py |

pyrope |

| Al |

almandine |

| P |

periclase |

References

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H. Acid leaching of magnesium from serpentine minerals. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 278. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Z. Extraction of magnesium from serpentine using HCl. Minerals Engineering 2020, 148, 106217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y. Leaching of magnesium from serpentine with nitric acid. Hydrometallurgy 2022, 208, 105808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocjan, A.; McKelvy, M.J.; Chizmeshya, A.V.G.; et al. Termal activation of serpentinite for CO2 sequestration and Mg extraction. Minerals 2020, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamori, M.; Boivin, J.A. Technico-economic simulation for the HCl-leaching of hybrid serpentine and magnesite feeds. Can. Metall. Q. 2001, 40(1), 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutrizac, J.E.; Chen, T.T.; White, C.W. Fundamentals of serpentine leaching in hydrochloric acid media. In Magnesium Technology 2000; Kaplan, H.I., Huga, J.N., Clow, B.B., Eds.; The Minerals, Metals and Materials Society: Nashville, TN, USA, 2000; pp. 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Gladikova, L.; Teterin, V.; Freidlina, R. Production of magnesium oxide from solutions formed by acid processing of serpentinite. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2008, 81(5), 889–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhuba, V.; et al. Integrated processing of serpentine acid leachate using activated silicates. Resources Conservation & Recycling 2023, 190, 106731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusik, K.; et al. Modified serpentine minerals as sorbents for toxic metal removal. Applied Clay Science 2020, 199, 105833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punenkov, S.E.; Kozlov, Yu.S. Chrysotile asbestos and resource conservation in the chrysotile asbestos industry. Mining Journal of Kazakhstan (in Russian). 2022, 3, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Musabekov, A.M. Purification of acidic solutions using thermally treated silicates. Vestnik of KazNU. Chemical Series 2019. [in Russian].

- Auyeshov, A.; Arynov, K.; Yeskibayeva, Ch.; Satimbekova, A.; Alzhanov, K. The Thermal Activation of Serpentinite from the Zhitikarinsky Deposit (Kazakhstan). Molecules 2024, 29, 4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).