1. Introduction

Serpentinite rocks and their processing waste represent a valuable source of magnesium (up to 43 wt.% MgO) and silica (up to 45 wt.% SiO₂). They have long attracted the attention of researchers as a potential raw material for the production of industrially important magnesium- and silica-based compounds. However, despite extensive research into the integrated processing of serpentinite, practical implementation remains limited. This is primarily due to both technological and economic constraints that hinder the development and application of efficient recovery methods.

From a technological perspective, the challenge lies in the structural and chemical complexity of serpentinite. These rocks are mainly composed of minerals from the serpentine group—such as chrysotile, antigorite, and lizardite—with the general formula Mg₃Si₂O₅(OH)₄ or [Mg(OH)₂(MgOH)₂Si₂O₅]. While the magnesium-bearing phases are readily soluble in acids, they are unreactive in alkaline media. Consequently, most research has focused on acid-based leaching methods [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, although these methods offer certain advantages, they also present serious limitations from both technological and environmental standpoints.

One of the major issues associated with acid leaching (e.g., using H₂SO₄, HCl, or HNO₃) is the formation of insoluble polysilicic acids [

7], which convert into hydrated silica gel (SiO₂·nH₂O) during the leaching process. This gel layer forms on the surface of the particles, impeding further dissolution, complicating solid–liquid separation, and reducing the extraction efficiency of magnesium. In particular, it severely affects filtration and the removal of impurity metals from the pregnant solutions.

To mitigate these issues, it has been proposed to use sub-stoichiometric acid concentrations (30–40% of the theoretical H₂SO₄ requirement). Under such conditions, the quantity of silica gel formed is insufficient to block the surface completely. This approach allows for more efficient acid utilization (up to 98–100%) and achieves magnesium extraction yields of 30–40% [

8].

When higher acid concentrations are employed, the resulting dense silica residues can be further processed by alkaline treatment to selectively extract silicon in the form of soluble silicates. This forms the basis of a combined acid–alkali treatment, which enables the concurrent recovery of both magnesium and silicon while reducing secondary waste.

A review of the literature reveals that studies on the combined acid–alkali treatment of serpentinite are fragmented and remain an underexplored research area. According to a recent study by Rakhuba et al. (2023) [

4], this method can be successfully applied to technogenic serpentinite waste to produce products suitable for agricultural and construction purposes. Such research is particularly relevant to Kazakhstan, which possesses significant serpentinite reserves and large volumes of chrysotile-asbestos processing waste, as well as extensive areas of low-fertility land. The development of effective methods for utilizing these wastes is of environmental and socioeconomic importance.

The aim of this study is to investigate the processes involved in the combined acid–alkali treatment of serpentinite waste from the Zhitikara deposit (Republic of Kazakhstan). The work includes experimental research in combination with physicochemical methods to examine the dissolution mechanism of layered magnesium hydrosilicates in acid, as well as the structural and adsorption properties of the resulting amorphous silica.

2. Materials and Methods

Serpentinite waste from the Zhitikara deposit (Kazakhstan) with a particle size of ≤0.14 mm was used as the research material. The elemental composition of the sample was (wt.%): Mg – 25.0; Si – 17.45; Fe – 2.93; Al – 0.54; Ca – 0.50.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were obtained using a D8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker, Germany) equipped with Cu-Kα radiation at 40 kV and 40 mA. The diffraction data were processed using the EVA software package. Phase identification was carried out using the Search/Match function based on the PDF-2 Powder Diffraction File (ICDD).

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu IR Prestige-21 spectrometer (Japan) using an ATR (attenuated total reflectance) Miracle accessory by Pike Technologies (USA).

The specific surface area and pore size distribution were determined using the static capacity method (Model: BSD-660S A3) with a degassing zone followed by a temperature-controlled adsorption measurement (Zone-Test: Degas → Temp Zone).

Analytical procedures aimed at determining the elemental distribution during the leaching and purification processes were performed using a JSM-6490LV scanning electron microscope (JEOL, Japan) equipped with an INCA Energy 350 energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) system.

Theoretical assumptions underlying the experimental investigation of the combined acid–alkali leaching of serpentinite were as follows:

– The mechanism and kinetics of the dissolution of layered magnesium hydrosilicates [

9] are described by the shrinking core model and the pseudo-kinetic equation:

X = 1 – kt,

where: X is the degree of dissolution, k is the reaction rate constant, and t is the time. At the initial stage, the process is controlled by chemical interaction at the surface, while in later stages it becomes limited by the diffusion of the reagent into the porous particle interior.

– Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) dissolves amorphous forms of silica formed during acid treatment, converting them into soluble silicates. Under these conditions, magnesium is only weakly leached from the alkaline medium, enabling the selective extraction of silicon.

For clarity of presentation, the experimental procedures for investigating the acid–alkali treatment of serpentinite are included in the “Results and Discussion” section.

3. Results and Discussion

The combined method involving acid and alkali treatment is based on sequential processes occurring during the dissolution of serpentinite in acid and subsequent treatment of the acid-insoluble residues in alkaline media:

– During the acid leaching stage, the destruction of the crystalline lattice of serpentinite occurs, particularly in the regions of Mg–OH bonds and partially in Si–O–Mg bonds:

Mg²⁺ ions enter the solution, while the formed amorphous silica (SiO₂·nH₂O) creates a gel-like phase, which causes technological complications during the filtration and purification stages.

– The amorphous SiO₂·nH₂O reacts well with alkalis, transforming into soluble silicates.

Acid–alkali treatment. For the experiment, 100 g of serpentinite waste (SP⁰, the initial serpentinite sample) containing 25.75 g or 1.073 mol of Mg was used. According to the reaction equation (3):

1.073 mol of H₂SO₄ was required for complete leaching of Mg from 100 g of SP⁰.

A volume of 455 cm³ of a solution containing 1.073 mol of H₂SO₄ was placed in the reactor. Then, under stirring, 100.0 g of SP⁰ was added, marking the start of the reaction time. Intense boiling was observed during the addition due to the exothermic nature of the reaction, resulting in the formation of a foamy mass. After 30 minutes, the suspension was filtered hot through a blue ribbon filter using vacuum suction.

The filtration time was 2 hours. The total volume of the obtained filtrate, including the washings, was 470 cm³, with a pH of 0.72.

The mass of the undissolved residue was 83.6 g. The filtrate was a clear, colorless liquid with a slightly yellowish tint. The residual amount of free sulfuric acid in the filtrate was determined by acid–base titration using 0.5 M NaOH solution.

The results are presented in

Table 1.

The concentration of residual sulfuric acid after treatment was calculated using the following formula:

where: CNaOH — concentration of the NaOH solution, mol/L; VNaOH — volume of NaOH used for titration, mL; — volume of the sulfuric acid solution, mL.

The consumption of H₂SO₄ (%) was calculated using the following formula:

where:– amount of sulfuric acid consumed, mol; – initial amount of sulfuric acid, mol.

The chemical composition of the filtrate obtained at 105°C and the insoluble residue was determined using a JSM-6490LV scanning electron microscope (JEOL, Japan) equipped with an INCA Energy 350 energy-dispersive microanalyzer.

Based on the chemical analysis results, the compositions of the filtrate and insoluble residue were determined, as well as the extraction degree of individual elements from the initial serpentinite waste SP⁰. The distribution of elements in the filtrate and insoluble residue is presented in

Table 2.

According to

Table 2, during the initial acid leaching of the serpentine waste SP⁰ with sulfuric acid solution, a significant portion of magnesium, manganese, chromium, calcium, and aluminum (over 50%) is transferred into the sulfate solution.

At the same time, iron is only partially leached (27%), while silicon extraction is extremely low (2%).

The insoluble residue after leaching is substantially enriched in silicon (up to 98%) and iron (up to 73%).

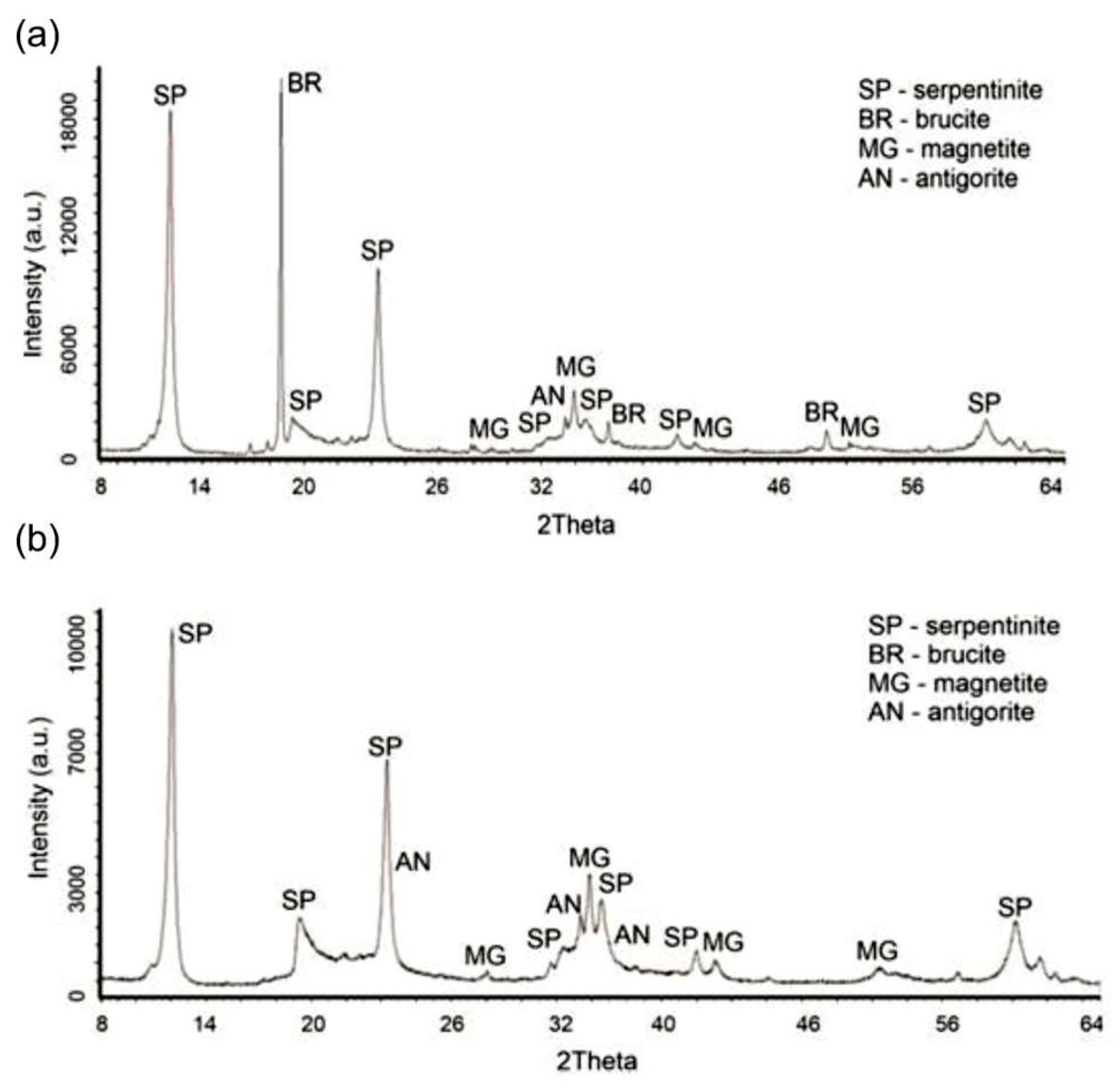

The phase transformations occurring during acid leaching are illustrated by the X-ray diffraction patterns (

Figure 1): the initial SP⁰ (a) and the leached product SP

Ⅰ (residue after acid treatment) (b). In diffractogram (b), the following phases were identified: chrysotile (SP⁰), antigorite (AN) — Mg₃Si₂O₅(OH)₄, magnetite — Fe₂O₃, pyrope — Mg₃Al₂[SiO₄]₃, and almandine — Fe₃Al₂[SiO₄]₃. The main changes in the phase composition after acid treatment include the disappearance of brucite [Mg(OH)₂] (BR) reflections at interplanar spacings d/n = 4.77; 2.365; 1.794 Å, and a reduction in the intensity of serpentinite (SP) peaks at d/n = 7.38; 3.661; 2.487; 1.53 Å and antigorite peaks at d/n = 7.30; 3.63; 2.52 Å.

The phase transformation associated with the formation of amorphous silica is not observed in the SPⅠ diffractogram.

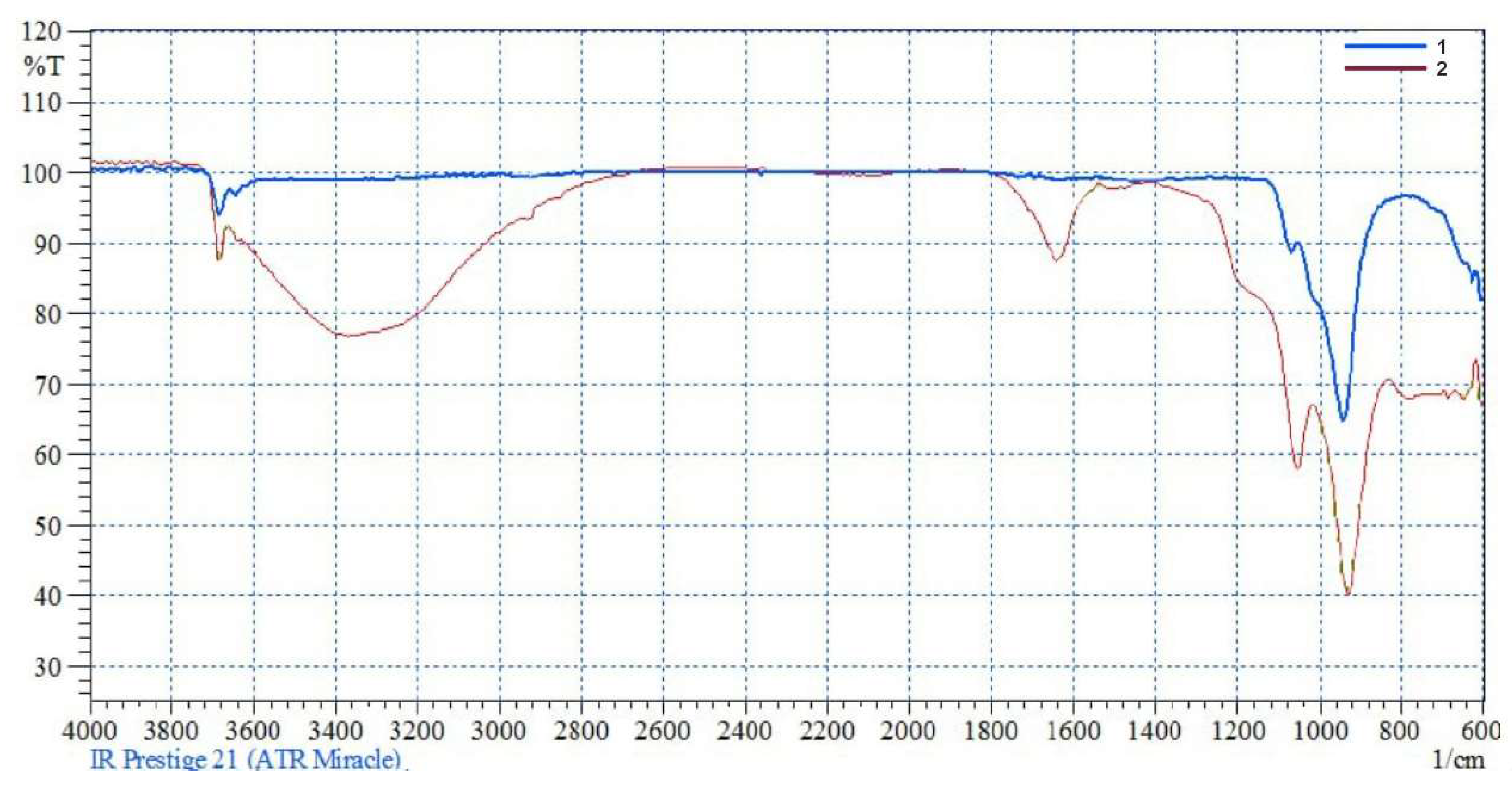

However, its presence in the system is confirmed by the FTIR spectrum of the acid-insoluble residue (

Figure 2).

A shoulder characteristic of amorphous silica [

10] at a stretching vibration frequency of νₐₛ(Si–O–Si) = 1064 cm⁻¹ appears as a distinct peak.

This indicates the breakdown of the tetrahedral–octahedral layered structure of the serpentine crystal lattice and the formation of Si–OH hydroxyl groups on its surface.

As a result, an independent amorphous silica phase is formed in the system.

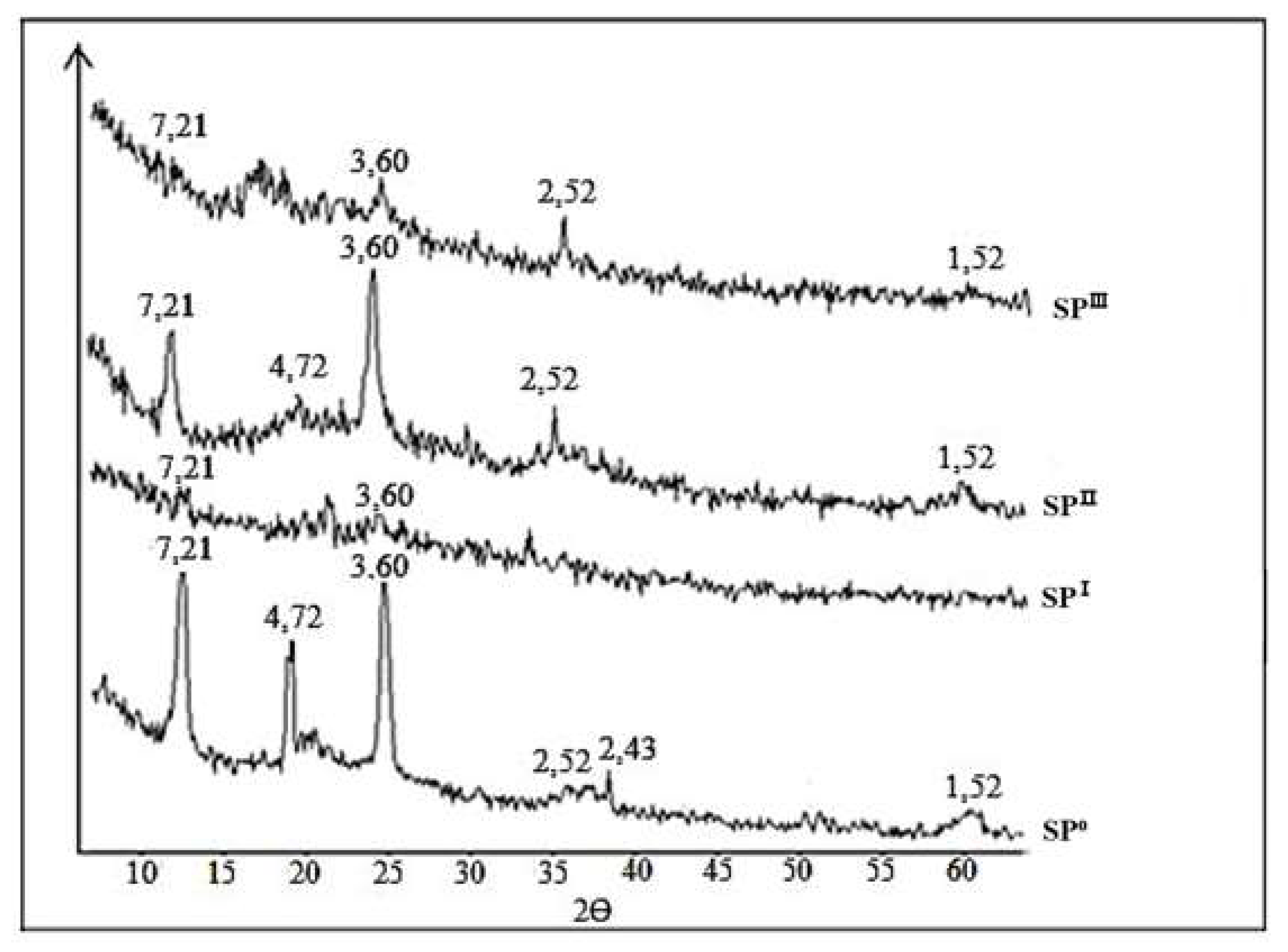

This assumption is further supported by X-ray diffraction analysis (

Figure 3). The characteristic reflections of serpentine minerals (SP⁰) are suppressed due to the formation of SiO₂·nH₂O after acid treatment (SP

Ⅰ). These reflections reappear with increased intensity after alkaline treatment of the acid-insoluble residue (SP

Ⅱ, residue after alkaline treatment), but their intensity decreases again after subsequent acid treatment of the alkaline residue (SP

Ⅲ, residue after repeated acid treatment). The observed changes in the diffractograms during acid–alkaline processing of serpentinite indicate that the acid affects only the surface layer of the multilayer magnesium hydrosilicate.

Experimental studies conducted to verify this assumption were carried out as follows. The insoluble residue weighing 83.6 g (SP

Ⅰ, obtained after acid treatment) was subjected to alkaline treatment (Stage 2). According to the elemental analysis of the insoluble residue (SP

Ⅰ), formed after leaching of the initial SP⁰ with sulfuric acid solution, the following mass fractions were determined: Mg — 15.0%, Si — 21.2%, Fe — 3.0%, Cr — 0.19%, and S — 3.18%. Calculations based on the magnesium, silicon, and oxygen contents showed that the composition approximately corresponds to the formula: 1.25 MgO·1.5 SiO₂·3H₂O. The calculations performed to determine the stoichiometry of interaction between this composition and NaOH solution, as well as the conditions for silica precipitation, were carried out according to equations (1) and (2), presented in

Table 3.

According to Equation (1) (

Table 3), 325 cm³ of 4.0 M NaOH solution (ρ = 1.155 g/cm³) was used for the treatment.

A total of 83.6 g of the acid-insoluble residue (SPⅠ) was loaded into the reactor, followed by the addition of 325 cm³ of 4.0 M NaOH solution. The mixture was heated to boiling and stirred for 2 hours, after which it was filtered under vacuum. Filtration proceeded slowly but satisfactorily. The mass of the resulting insoluble residue (SPⅠ), obtained after alkaline leaching, washing, and drying at 105°C, was 36.6 g (SPⅡ). The elemental composition of SPⅡ (wt%) was as follows: Mg – 25.1; Si – 18.7; Fe – 9.64; Al – 0.27; Ca – 0.18; Cr – 0.17; O (calculated by difference) – 48.71. The combined volume of the filtrate and washing water was adjusted to 1000 cm³ using distilled water. The pH of the resulting solution was 11.46.

The filtrate was subsequently neutralized with 45% H₂SO₄ to pH 7.0 in accordance with Equation (2) (

Table 3). As a result, a white fine-dispersed precipitate of silica formed and was separated by filtration. The mass of dry SiO₂, obtained after washing and drying the gel-like precipitate (230.0 g) from sodium sulfate and residual SO₄²⁻ (Ba²⁺ test), was 25.80 g. Elemental analysis of the resulting SiO₂ showed the following composition (wt%): Si – 42.03; Al – 0.23; Na – 0.75; O – 56.99.

The silica (SiO₂) yield was 95.78% based on the acidic residue (SPⅠ, 83.6 g), and 60.3% relative to the initial residue (SP⁰).

Elemental analysis of the initial sample (SP⁰), the acid-leached residue (SPⅠ), and the alkaline residue (SPⅡ) showed that after the two-step treatment SP⁰ (acid and alkaline), the final residue SPⅡ became comparable in composition to the original SP⁰ in terms of the main elements Mg and Si. In SP⁰, the molar Mg/Si ratio was 1.68, while in SPⅡ it was 1.56.

These data indicate that after alkaline treatment, i.e., the removal of the silica layer from the surface of SPⅠ particles, the inner layers retain the serpentine structure [Mg₃Si₂O₅(OH)₄]. To confirm this assumption, the alkaline residue (SPⅡ, 36 g) was subjected to repeated acid leaching using a 2.0 M H₂SO₄ solution (stage 3). The resulting acid-insoluble residue (SPⅢ) was subsequently treated with alkali to obtain the alkaline residue (SPⅣ). The experimental procedures applied at stages 3 (H₂SO₄ treatment) and 4 (NaOH treatment) were analogous to those used at stages 1 and 2. The obtained SPⅢ and SPⅣ residues were also analyzed following the same approach as for SPⅠ and SPⅡ.

The summarized results of the elemental analysis of the insoluble residues after sequential acid–alkaline treatment (H₂SO₄ and NaOH) are presented in

Table 4.

The analysis results of SP

Ⅲ and SP

Ⅳ (

Table 4) indicate that the dissolution mechanism of serpentinite in acids is most accurately described by the shrinking core model (Shrinking Core Model). The degree of dissolution is a function of the duration of the process, which may be prolonged depending on the activity of the serpentinite surface during its interaction with acid solutions.

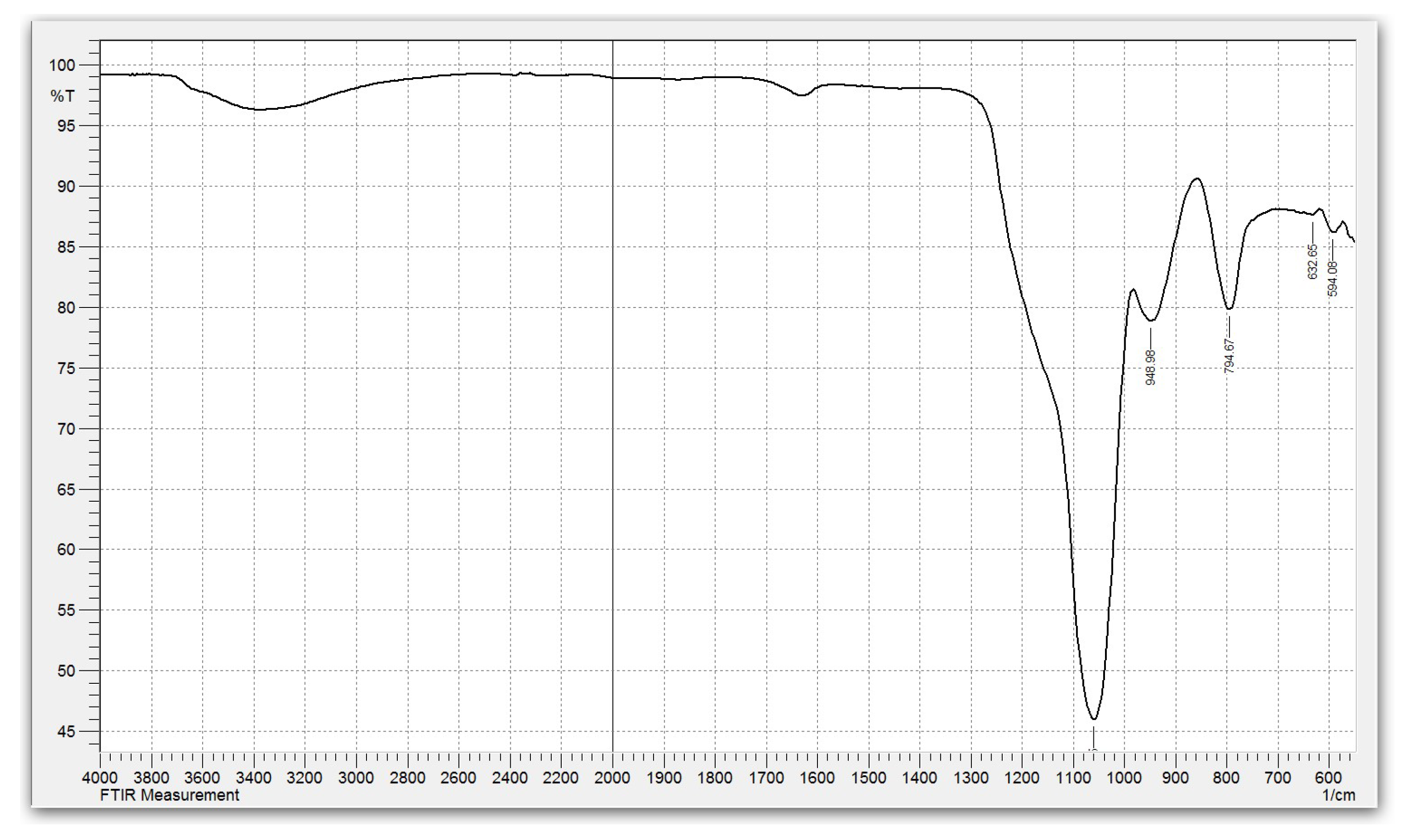

Study of the properties of amorphous silica. The obtained silica contains no more than 1% impurities (0.75% Na + 0.25% Al) and approximately 8.0% adsorbed water, which corresponds to a composition of SiO₂·0.36H₂O. The IR spectrum of silica with this composition is shown in

Figure 4.

Characteristic absorption bands were observed at 3450 cm⁻¹ (O–H stretching vibrations), 1630 cm⁻¹ (H–O–H bending vibrations), and 1064 and 796 cm⁻¹ (asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of Si–O–Si bonds), confirming the amorphous structure of hydrated SiO₂ [

11].

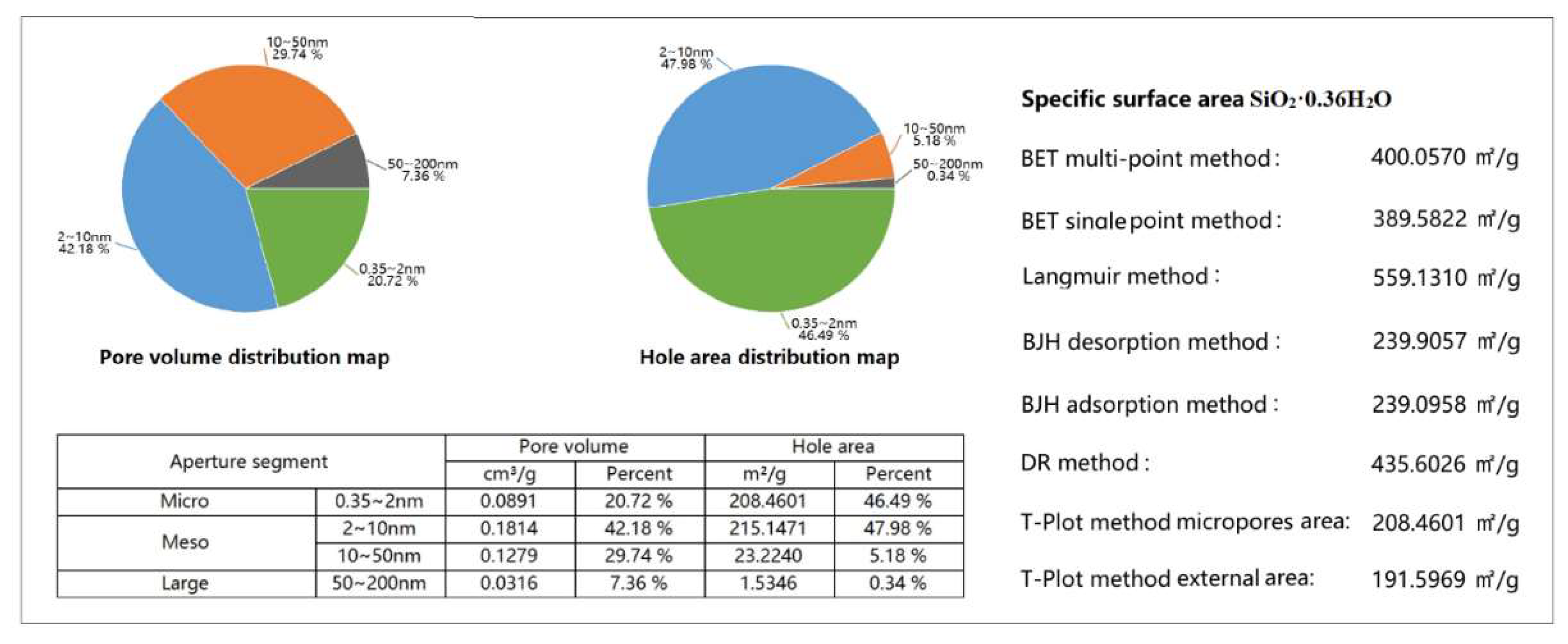

The obtained amorphous silica, containing more than 95.0% of the main SiO₂ component, can be used for various applications. Its specific surface area and adsorption properties, determined using the BET adsorption method, are presented in

Figure 5.

According to the pore volume distribution diagram, the SiO₂·0.36H₂O sample contains micropores with sizes ranging from 0.35 to 2 nm (20.72%), and mesopores in the ranges of 2–10 nm (42.18%) and 10–50 nm (29.74%), totaling 92.64%. The pore area distribution analysis shows that micropores contribute 46.49% of the surface area, while mesopores of 2–10 nm and 10–50 nm contribute 47.98 and 5.18%, respectively. Thus, the combined surface area contribution of micro- and mesopores reaches 99.65%, indicating a well-developed hierarchical porous structure.

The research results show that the amorphous silica obtained by the combined method has a high specific surface area and porous structure. According to the IUPAC classification, it is classified as mesoporous silica, which is recommended for use as an adsorbent, support, or catalyst matrix.