1. Introduction

Palliative Care (PC) can be defined as assistance to all areas of the person who is in a terminal or serious state of their illness, more specifically in those moments when the last days are approaching. The main objective is to provide the greatest possible well-being and comfort to the patient and their environment [

1].

To go back to the origin of the CP, it all begins in the Byzantine Empire during the fourth century with names such as

hospitium or

xenodochium. When this comes to Europe the Christian institutions take charge of these first hospices. The first hospital was founded in Rome by Fabiola, to attend to the pilgrims whoarrived at the port of Ostia [

2].

PC is performed on people whose health situation is critical and terminal. The Spanish Society of Palliative Care highlights as key elements: Incurable progressive disease, highresponse to treatment administered, multiorgan problemas, impacto negative in the social environment of the patient andpronóstico less than 6 months. [

3]

In Spain in the year 2021, 450,744 people died of which 1435 were children between 0 and 14 years of age. The predominant causes were conditions in the perinatal period, congenital malformations or tumors [

4]

Pediatric CPs should focus not only on children but also on family, professionals, or school settings. The right to protection must be respected and taken into account. [

5] Organic Law 1/96 of 15 January on the Legal Protection of Minors [

6] considers that minors are capable of participating in the satisfaction of their needs. In addition, following Law 41/2002 on patient autonomy, children must be informed of the entire process of their disease, since in many cases both they and their environment are aware of the situation in which they findthemselves. [

5]

The objectives of such care in children are: individualized, continuous and biopsychosocial comprehensive care, treatment of the unit (child-family), promotion of autonomy and dignity (opinions or desires), facilitating the stay at home, maintenance of daily activities and maintaining an atmosphere of comfort (doctor-patient relationship)[

6].

The final period of life is a key moment where the number of needs increases due to the progressive deterioration of the disease, increasing the number of care. Specifically in recent days these symptoms become very complicated to control being necessary to consider palliative sedation. [

6]

The consensus concept of PEdation Paliativa (SP) consists of the decrease of the level of consciousness of the patient with his corresponding consent through the use of drugs, in order to reduce the suffering of the same, due to the refractory symptoms caused by the stage of his disease. The aim is to achieve the minimum level of effective sedation in the control of these symptoms[

7,

8].

We must discern refractory symptoms from difficult symptoms[

7,

9]: the former cannot be controlled with available treatments in a reasonable time. Decreased consciousness is required. A difficult symptomrequires intensive treatment (pharmacological, instrumental and psychological) for its correct control.

With respect to the ethics and legality involved in the matter there are certain requirements for the indication of this procedure. It must be before a refractory symptom with terminal illness, without other possibilities of treatment, leaving a record of it in the patient's history with his consent and with the intention of alleviating suffering. [

7,

9]

The most commonly used drugs are benzodiazepines, sedative neuroleptics, anticonvulsants, anesthetics... [

9]

The process of palliative sedation itself should assess the following points: anticipation of the effects, the patient's health situation, their own or family's consent (Law 41/2002 of November 14), the pharmacological strategy to be followed, support for the family and the recording of the decision and procedure[

10].

After the above, the idea of considering this procedure as a disguised euthanasia comes to mind. There is a clear distinction between sedation and euthanasia[

10]: sedation is intended to alleviate suffering or symptoms by altering consciousness in adjusted doses and euthanasia is the elimination of life by lethal doses.

The nursing profession has a key position in the concept of Palliative Care. Nursing requires being at the bedside and providing the patient with the best possible care and even more so in their last days. To achieve excellence in care, exhaustive prior and specific training on these topics is needed.

It is evident that the main investigations hardly address issues related to terminal patients and even less in children. For this reason, this lack of articles and information suggests the need to address it. The nurse, like other people on the health team, must know the different aspects of these care and procedures.

For this reason, the work carried out aims to investigate what is known about palliative sedation in this type of patients. More specifically, it seeks to know what ethical aspects surround the issue and the indiscusible presenceof parents as well as which drugs are used on the few occasions that are performed in palliative care units.

Research Questions

Analyze the scientific evidence in the different areas concerning palliative sedation in pediatric patients.

Identify the existing ethical aspects to apply palliative sedation in pediatric patients.

To update knowledge about the effectiveness of therapies and medication most used in palliative sedation in children.

2. Methodology

Type of study.

A Scoping Review of the scientific literature found on palliative sedation in pediatric patients with any pathology has been conducted.

Search strategies.

We conducted a literature search, from November 2021 to April 2022; in the following databases

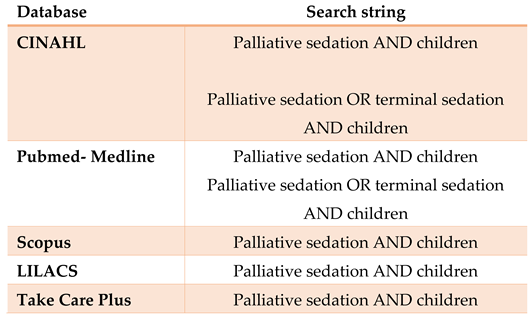

Table 2 shows the bibliographic search carried out including the search strings used to achieve this work. The search period runs from November 2024 to April 2025.

Table 2.

Databases queried and search strings used.

Table 2.

Databases queried and search strings used.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria have been: original articles or reviews that relate palliative sedation and its different areas.

Studies in adults, clinical practice guidelines and grey literature have been excluded as well as publications in languages other than Spanish, English, French and Portuguese

Analysis of methodological quality:

The methodological quality of the articles finally selected has been evaluated with the Critical Appraisal Skill Programme (CASP) tool. Specifically, the (reviews, cohort studies and cross-sectional descriptive) has been used. The minimum score to be considered the study eligible for the review was 5 out of 10 in the case of literature reviews and cross-sectional descriptive studies and 6 out of 12 for cohort studies.

Data aggregation method:

Due to the type of data obtained after the search, a narrative aggregation of these is presented. Mathematical aggregation is ruled out.

Ethical aspects:

There is no conflict of interest on the part of the authors. As it is a review, no other ethical considerations must be taken into account.

3. Results

Description of search results:

As can be seen in Figure 1A total of 587 results were obtained from the different databases, 13 duplicate studies were eliminated through the bibliographic manager Refworks. Of the remaining 574 articles, 560 were eliminated for not meeting the selected inclusion criteria. Finally, 14 articles were selected to assess their quality and subsequent review. (S1: Flowchart)

Description of study characteristics

Table 3 presents the characteristics of the included studies. The studies obtained range from 1997 [

12] to 2021 [

24,

25].

The selected studies have been carried out in numerous countries so that this great variety must be considered, ranging from countries such as the USA [

12,

17] to Israel [

13]. However, only one study has been conducted in Spain [

25].

It should be noted the great variety of the designs found, the most frequent design has been cohorts in 8 studies [

13,

17,

18,

19,

20,

22,

24,

25], followed by clinical cases [

12,

23], descriptive [

14,

16] and bibliographic reviews [

15,

21]. We must take into account the lack of experimental articles since the chosen theme and ethical aspects are fundamental when performing this technique of palliative sedation in pediatric patients.

Regarding the sample size is very varied since we have questionnaires made to the staff of a plant and also questionnaires for 4786 pediatricians of different specialties. In other cases we have specific clinical cases of patients.

Table 3.

General results of the analysis of the current situation of the different areas of palliative sedation in pediatric patients.

Table 3.

General results of the analysis of the current situation of the different areas of palliative sedation in pediatric patients.

| Author and year |

Title |

Type of study |

Country/City |

Valued results |

Tobias J, et al.

1997[12]

|

Propofol Sedation for Terminal Care in a Pediatric Patient |

Clinical case |

Columbia USA |

Drugs and therapies |

Postovsky S, et al.

2007[13]

|

Practice of Palliative Sedation in children with brain tumors and sarcomas at the end of life |

Retrospective cohort study |

Haifa

Israel |

Drugs and therapies |

Kuhlen M, et al.

2011[14]

|

Palliative Sedation in 2 Children with Terminal Cancer- An Effective Treatment of Last Resort in a Home Care Setting |

Descriptive study: case series |

Dusseldorf

Germany |

Drugs and therapies

Ethical aspects |

Kiman R, et al.

2011[15]

|

End of Life Care Sedation for Children |

Literature review |

Buenos Aires

Argentina |

Drugs, therapies

Ethical aspects |

Pousset G, et al.

2011[16]

|

Continuous Deep Sedation at the End of Life of Children in Flanders, Belgium |

Prospective descriptive study |

Flanders

Belgium |

Drugs and therapies |

Anghelescu D, et al.

2012[17]

|

Pediatric Palliative Sedation Therapy with Propofol:

Recommendations Based on Experience

in Children with Terminal Cancer |

Retrospective cohort study |

Memphis

USA |

Therapy and drugs |

Korzeniewska-Eksterowicz A, et al.

2014[18]

|

Palliative Sedation at Home for Terminally Ill

Children With Cancer |

Retrospective cohort study |

Lodz

Poland |

Therapies and drugs |

Vallero S, et al.

2014[19]

|

End-of-Life Care in Pediatric Neuro-Oncology |

Retrospective cohort study |

Italy |

Therapies and drugs |

Miele E, et al.

2019[20]

|

Propofol-based palliative sedation in terminally ill

children with solid tumors |

Retrospective cohort study |

Rome

Italy |

Therapies and drugs |

Badarau D, et al.

2019[21]

|

Continuous Deep Sedation and Euthanasia in

Pediatrics: Does One Really Exclude the Other

for Terminally Ill Patients? |

Bibiliographic review |

Switzerland |

Ethical aspects |

Maeda S, et al.

2020 [22]

|

Continuous deep sedation at the end of life in

Children with cancer: experience at a single center

in Japan |

Retrospective cohort study |

Kyoto

Japan |

Therapies and drugs |

Fedeli P, et al.

2020[23]

|

The will of young minors in the terminal stage

of sickness: A case report |

Clinical case |

Dressing room

Italy |

Ethical aspects |

Blais S, et al.

2021[24]

|

End-of-life care in children and adolescents

with cancer: perspectives from a French

Pediatric Oncology Care Network |

Retrospective cohort study |

France

Canada |

Therapies and drugs |

de Noriega I, et al.

2021[25]

|

Descriptive analysis of palliative sedation in a Pediatric Palliative Care Unit |

Retrospective cohort study |

Madrid

Spain |

Therapies and drugs |

2.1. Results of Articles on Ethical Aspects for the Application of Palliative Sedation in Pediatric Patients

Of the 14 results, 4 [

14,

15,

21,

23] tell us about the ethical aspects. In the first place, refractory symptoms and their palliation are the main objective for which palliative sedation is applied, whether dyspnea, pain or the psychological suffering that entails a terminal illness[

12,

13,

19]. It is also notorious the lack of studies on palliative sedation in these patients, which usually follows adult protocols and can cause problems regarding doses and the initiative of professionals when using SP[

12,[

19].

According to Badarau et al.[

19] the ethical basis that sustains SP is the principle of double effect whose origin dates back to the time of the Roman Empire. For it to be carried out, four conditions must be met so that the objective to be achieved must be good, without taking into account the possible negative impact, the act must be understood as beneficial for the patient and finally we have to have a compelling reason. In this way the pain is relieved despite the consequent loss of consciousness that would be the negative effect. It is difficult to know what is the intention of the professional who carries out the SP in the patient with what there is an ethical limbo without specifying and that leaves room for doubt.

As a complement to the above, several articles highlight the unanimous idea that children have the right both to express their opinion and to be informed of their health situation and the different treatments available[

14,

15,

23]. This is supported by the different conventions that have been held throughout history, among which the Convention on the Rights of the Child held in 1989 should be highlighted. Several American committees strongly propose and recommend that the child be involved in decision-making taking into account factors such as the child's age or developmental moment[

14,

15].

The main problem is that there is no firm established age at which the child is considered to have an objective and realistic criterion about his or her situation [

14,

15,

21,

23]. According to the article by Kuhlen et al.[

14] the Ethics Committee established that between 7 and 12 years the opinion of the child can and should be taken into account due to its development together with the opinion of the parents, and until the age of 14 it is assumed that the patient is already autonomous to decide but the specific case must be studied.

Due to the above, the key role of parents or legal guardians comes into play, who are the ones who will make the decision in the event that the team considers the child incapable of making the decision or is simply in a comatose state[

21]. In the clinical case presented by Kiman et al.[

15] Both patients were able to express their opinions, but needed the help of parents to determine the therapeutic route to follow.

In addition, another important aspect to take into account is the clear distinction that must be explained to parents, due to the false belief of understanding SP as euthanasia, something that causes mixed feelings in the family and relatives [

14,

15].

2.2. Results of Articles on Effectiveness of Therapies and Medication Most Used in Palliative Sedation in Pediatric Patients

In 12 [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

20,

22,

23] of the 14 selected studies this topic is addressed. Of these 2 [

12,

17] expose the benefits of Propofol; since it is a fast-acting drug as well as an antiemetic. It lacks analgesic properties but associated with other drugs is a good drug of choice.

Due to the poor response, with other conventional drugs, of the refractory symptoms of the patients studied, especially pain and dyspnea, it was decided to apply continuous infusion of propofol. Doses vary by patient and study. This drug is generally associated with opioids [morphine) in lower doses than those of previous treatment and benzodiazepines (midazolam]. Patients remain comfortable, with no sudden awakenings or agitation. Effectiveness can be assessed in addition to the above, with the level of sedation and fewer staff reevaluations [

12,

17]

In 6 articles [

14,

16,

18,

19,

22,

25] continuous midazolam is used as the drug of choice to sedate patients. It should be noted its anticonvulsant properties and the great effectiveness with respect to symptoms such as dyspnea and agitation. This associated with opioids such as morphine in lower doses, antiemetics, barbiturates allow patients to maintain acceptable levels of sedation and stable vital signs [

14,

18].

The remaining 3 studies [

13,

14,

15] deal with the use of morphine. This drug is used in most patients in the studies to induce sleep and is key along with the others mentioned above. Depending on the case it is used or not in continuous infusion.

In the study by Postovsky et al. [

13] used together with midazolam it demonstrated great efficacy in making patients remain calm and unconscious despite maintaining stable vital signs. To control the doses, patients were periodically assessed.

Despite its apparent advantages, it can also cause adverse effects and is not the most recommended alternative to start sedation[

18].

4. Discussion

Despite the notorious medical and technical development that has taken place in health fields in recent decades, many children suffer from diseases that sooner or later will cause their death. Because of this, good management of palliative care in this type of patient would be highly recommended to ensure a quality of life and a quality of death. The main problem is that we find certain aspects (political, ethical and legal) that act as obstacles to address the issue [

15,

25].

When other treatments for children's refractory symptoms do not achieve the result we expect, professional teams support the use of the procedure known as palliative sedation. There is no specific definition and less referred to pediatrics, in addition there are few guidelines and protocols to resort to in these cases. Here we must also assess the intrinsic presence of aspects such as parents, patient autonomy, psychological development, etc ... [

25]

Regarding the ethical aspects, it is concluded that the patient must know about his situation taking into account his development capacity and all this is protected by what was agreed in conventions and committees that have addressed the issue. The principle of double effect mentioned by a study[

21] is key since it values unconsciousness and the palliation of suffering. All studies [

14,

15,

21,

23] that have investigated the ethical aspects regarding palliative sedation in this type of patients agree on the complexity of this procedure due to the child's ability to understand. One study [

14] specifies age and how this decision should be approached, objectively but in the rest it is not specified.

Despite the authors' strong support for the procedure, all [

14,

15,

21,

23] mention the parental role in decision-making, which is key due to the patients' children's condition. Another aspect to keep in mind is that although there are many supporters, several studies mention the great tendency to compare palliative sedation and euthanasia [

21,

23]. All the articles found on ethical aspects, despite having an adequate methodological quality and taking into account the novelty of the subject treated, may happen that with the passage of time they change when deepening the research and the general opinion of the population, this due to the effort that is being invested in recent years in the biopsychosocial assessment of the situation of patients.

Regarding treatments, it is worth mentioning the wide use of propofol for the palliation of refractory symptoms such as dyspnea or pain. The doses used throughout the duration of the procedure are higher in two studies[

17,

20]. All authors refer in their articles [

12,

17,

20] the use as adjuvants of other drugs such as midazolam or morphine among others. In these case series, great results and effectiveness are demonstrated, so it could be interesting to deepen the use of this drug for children.

In most cases, midazolam is used to initiate the sedation process in this type of patient. Some studies mostly propose the use of adjuvant drugs such as morphine, although one of them [

16] highlights that due to its side effects it can be problematic if it is used to induce sleep. Vital signs were evaluated in a study in which continuous infusion was also performed [

14] and nutrition and hydration were mentioned in the study by Pousset et al[

16].

Morphine is used less as the drug of choice along with other antiemetic drugs, barbiturates or midazolam [

13,

15,

20]. Doses are only mentioned in the study by Kiman et al[

15].

5. Conclusions

There is an evident lack of research on the subject of palliative sedation in pediatric patients, the deepening in this topic and in the aforementioned aspects would considerably improve the quality of palliative care in this type of patients.

The ethical aspects surrounding the procedure in children are ambiguous and difficult to assess, but it is worth highlighting the autonomy of the patient, the assessment of the development of the child and the role of parents or legal guardians.

For the procedure, midazolam is used as the drug of choice along with other adjuvants such as morphine in most cases with good results. There are few studies on propofol therapies but they are quite promising in terms of effectiveness.

References

- Consensus definition of Palliative Care - Latin American Association of Palliative Care [Internet]. [cited 2022 Feb 11]. Available from: https://cuidadospaliativos.org/definicion-consensuada-de-cuidados-paliativos/.

- Montes de Oca GA, Director L, Mexico AH. History of palliative care. 2006 [cited 2022 Feb 4]; Available from: https://www.ru.tic.unam.mx/handle/123456789/1064.

- Palliative S of C. Palliative Care Guide. 2014 [cited 2022 Feb 5]; Available from: https://cmvinalo.webs.ull.es/docencia/Posgrado/8-CANCER and palliative care/guidance.pdf.

- Deaths by cause of death. National Institute of Statistics (INE) [Internet]. 2021. [cited 2022 Feb 13]; Available is: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=7947#!tabs-tabla.

- Pediatric Palliative Care in the National Health System: Care Criteria. Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. [Internet]. 2014. [cited 2022 Feb 13]. Available in: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/pdf/01-Cuidados_Paliativos_Pediatricos_SNS.pdf.

- PALLIATIVE SEDATION GUIDE. COLLEGIATE MEDICAL ORGANIZATION (OMC)SPANISH SOCIETY OF PALLIATIVE CARE (SECPAL). Cuad Bioethics [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2022 Feb 14]; XXII(3):605–12. Available from: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=87522184009.

- Clementina Acedo Claro, Bárbara Rodríguez Martín. Palliative sedation [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 14]. Available from: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1699-695X2021000200009.

- Luisa La Rica Escuín M DE, Torrubia Atienza P, Moreno Mateo R, Lauroba Alagón P, Pérez Rosel J, Germán Bes C, et al. Palliative sedation. Take care of your health [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2022 Feb 4]; 13:54–7. Available from: https://zaguan.unizar.es/record/61608/files/texto_completo.pdf.

- Vol LR-RHIBA, 2010 undefined. The what, when, why and how of palliative sedation. hospitalitaliano.org.ar [Internet]. [cited 2022 Feb 4]; Available from: https://www.hospitalitaliano.org.ar/multimedia/archivos/noticias_attachs/47/documentos/8757_69-75-revisionrodriguez-30-2-2010.pdf.

- Lavernia H, Medical DM-H, 2016 undefined. Ethical reflections on palliative sedation in terminally ill patients. medigraphic.com [Internet]. [cited 2022 Feb 4]; Available from: https://www.medigraphic.com/cgi-bin/new/resumen.cgi?IDARTICULO=65093.

- Cabello JB. Plantilla para ayudarte a entender estudios de Cohortes. En: CASPe. Guias CASPe de lectura crítica de la literature médica. Alicante: CASPe; 2005. Cuaderno II: 23-27.

- Tobias JD. Propofol sedation for terminal care in a pediatric patient. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1997; 36(5):291–3.

- Postovsky S, Moaed B, Krivoy E, Ofir R, Ben Arush MW. Practice of palliative sedation in children with brain tumors and sarcomas at the end of life. Pediatr Hematol Oncol [Internet]. 2007 Sep; 24(6):409–15. Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=17710658&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [CrossRef]

- Kuhlen M, Schneider K, Richter U, Borkhardt A, Janssen G. Palliative sedation in 2 children with terminal cancer - an effective treatment of last resort in a home care setting. Klin Padiatr [Internet]. 2011 Nov; 223(6):374–5. Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=22052636&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [CrossRef]

- Kiman R, Wuiloud AC, Requena ML. End of life care sedation for children. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2011 Sep; 5(3):285–90. [CrossRef]

- Pousset G, Bilsen J, Cohen J, Mortier F, Deliens L. Continuous deep sedation at the end of life of children in Flanders, Belgium. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011 Feb; 41(2):449–55. [CrossRef]

- Anghelescu DL, Hamilton H, Faughnan LG, Johnson L-M, Baker JN. Pediatric Palliative Sedation Therapy with Propofol: Recommendations Based on Experience in Children with Terminal Cancer. J Palliat Med [Internet]. 2012 Oct; 15(10):1082–90. Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=104505863&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [CrossRef]

- Korzeniewska-Eksterowicz A, Przyslo L, Fendler W, Stolarska M, Mlynarski W. Palliative sedation at home for terminally ill children with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag [Internet]. 2014 Nov; 48(5):968–74. Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=109767802&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [CrossRef]

- Vallero SG, Lijoi S, Bertin D, Pittana LS, Bellini S, Rossi F, et al. End-of-life care in pediatric neuro-oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014 Nov 1; 61(11):2004–11. [CrossRef]

- Miele E, Angela M, Cefalo MG, Del Bufalo F, De Pasquale MD, Annalisa S, et al. Propofol-based palliative sedation in terminally ill children with solid tumors: A case series. Medicine (Baltimore) [Internet]. 2019 May 24; 98(21):e15615–e15615. Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=138773997&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [CrossRef]

- Badarau DO, Clercq EDE, Elger BS. Continuous deep sedation and euthanasia in pediatrics: Does one really exclude the other for terminally ill patients? J Med Philos (United Kingdom). 2019 Jan 14; 44(1):50–70. [CrossRef]

- Maeda S, Kato I, Umeda K, Hiramatsu H, Takita J, Adachi S, et al. Continuous deep sedation at the end of life in children with cancer: experience at a single center in Japan. Pediatr Hematol Oncol [Internet]. 2020 Aug; 37(5):365–74. Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=32379512&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [CrossRef]

- Fedeli P, Giorgetti S, Cannovo N. The will of young minors in the terminal stage of sickness: A case report. Open Med (Warsaw, Poland) [Internet]. 2020 Jun 8; 15(1):513–9. Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=33336006&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [CrossRef]

- Blais S, Cohen-Gogo S, Gouache E, Guerrini-Rousseau L, Brethon B, Rahal I, et al. End-of-life care in children and adolescents with cancer: perspectives from a French pediatric oncology care network. Tumori [Internet]. 2021; Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85105732633&doi=10.1177%2F03008916211013384&partnerID=40&md5=f836f06ebddd761e43e4525a97590e52. [CrossRef]

- de Noriega I, Rigal Andrés M, Martino Alba R. Descriptive analysis of palliative sedation in a pediatric palliative care unit . An Pediatr [Internet]. 2021; Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85101148157&doi=10.1016%2Fj.anpedi.2021.01.005&partnerID=40&md5=7dfeed76ad489c2e398c52682b0c97c9.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).