3. Results

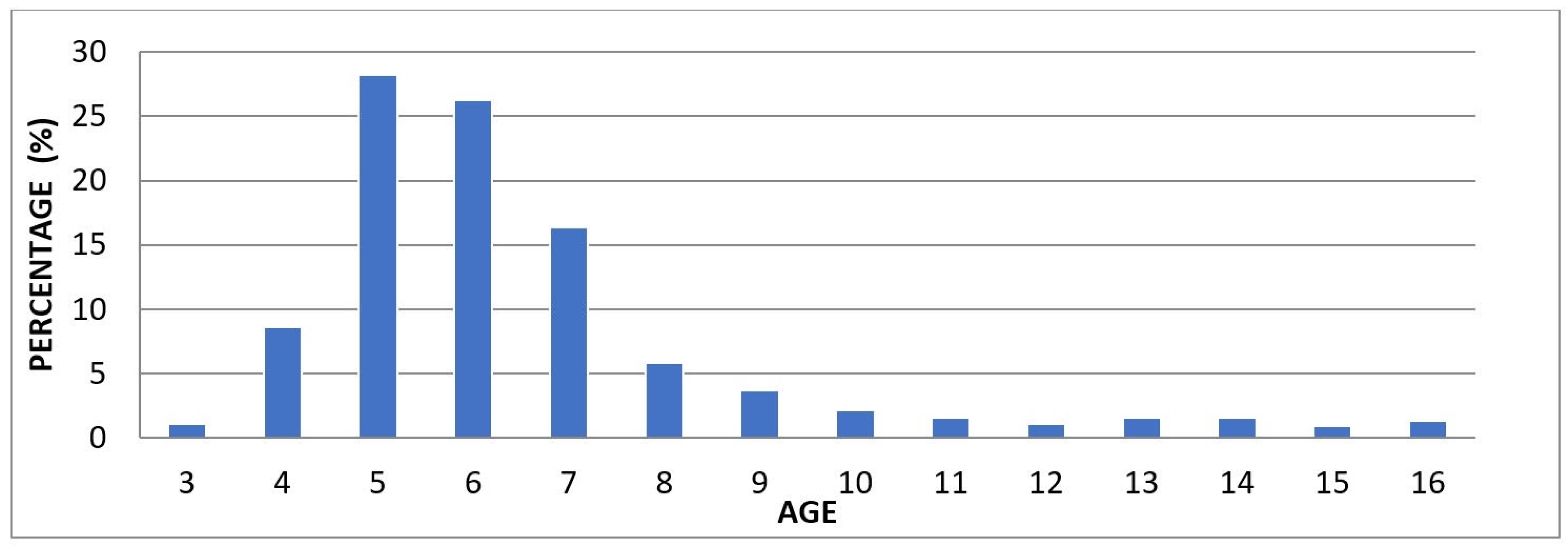

When examining the age distribution of the children included in our study, the highest proportion was observed in the 5-year-old group with 28.23%. This was followed by the 6-year-old group with 26.29%, the 7-year-old group with 16.38%, and the 4-year-old group with 8.62%. In the older age groups, the proportions gradually decreased, with 5.82% in the 8-year-old group, 3.66% in the 9-year-old group, and 2.16% in the 10-year-old group. Additionally, the proportions in the 11-, 12-, 13-, and 14-year-old groups ranged between 1.51% and 1.08%, while the lowest rates were recorded in the 15-year-old group (0.86%) and the 16-year-old group (1.29%) (

Table 2). The distribution of children treated under general anesthesia by age group is illustrated using a 100% stacked column chart (

Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

100% stacked column chart showing the age group distribution of children treated under general anesthesia.

Figure 1.

100% stacked column chart showing the age group distribution of children treated under general anesthesia.

Table 2.

Distribution of children treated under general anesthesia by age group.

Table 2.

Distribution of children treated under general anesthesia by age group.

| Age |

n |

% |

| 3 |

5 |

1.08 |

| 4 |

40 |

8.62 |

| 5 |

131 |

28.23 |

| 6 |

122 |

26.29 |

| 7 |

76 |

16.38 |

| 8 |

27 |

5.82 |

| 9 |

17 |

3.66 |

| 10 |

10 |

2.16 |

| 11 |

7 |

1.51 |

| 12 |

5 |

1.08 |

| 13 |

7 |

1.51 |

| 14 |

7 |

1.51 |

| 15 |

4 |

0.86 |

| 16 |

6 |

1.29 |

According to gender data, 43.3% of the children were girls and 56.7% were boys. Based on systemic health status, 76.1% of the children were healthy, while 23.9% had a systemic disease. Among systemic diseases, the most frequently observed were Autism (9.5%), Mental Retardation (2.2%), Epilepsy (1.5%), Cerebral Palsy (1.5%), and Down Syndrome (1.3%). Atrial Septal Defect (ASD) (0.9%), Cleft Lip and Palate, Bronchitis, Asthma, and Penicillin Allergy were each observed at a rate of 0.7%. Less common conditions included Allergic Asthma, Developmental Delay, Hyperactivity, and Microcephaly (0.4%); Lung Cyst, Atopic Dermatitis, Refractory Rickets, Galactosemia, Goiter/ASD (Atrial Septal Defect), Hydrocephalus, Hypothyroidism, Allergy to Local Anesthetics, Sickle Cell Anemia, PFO, PFAPA (Periodic Fever, Aphthous Stomatitis, Pharyngitis, and Adenitis) Syndrome, Scoliosis, and Thalassemia Major (0.2%). According to the ASA classification, 75% of the children were categorized as ASA 1, 23.9% as ASA 2, and 1.1% as ASA 3. Strip crown application was performed in 0.2% of the children, while 99.8% did not receive this treatment. Scaling/polishing was performed in 16.6% of the cases and not performed in 83.4%. Fluoride application was carried out in 17.9% of the children, whereas 82.1% did not receive it (

Table 3).

In our study, based on the data obtained from 464 children, the median age was found to be 6. Additionally, the median values for the types of treatments performed were as follows: 6 for composite fillings, 1 for stainless steel crowns, 0 for pulp capping, root canal treatment, and fissure sealants, 2 for pulpotomy, and 3 for tooth extraction (

Table 4).

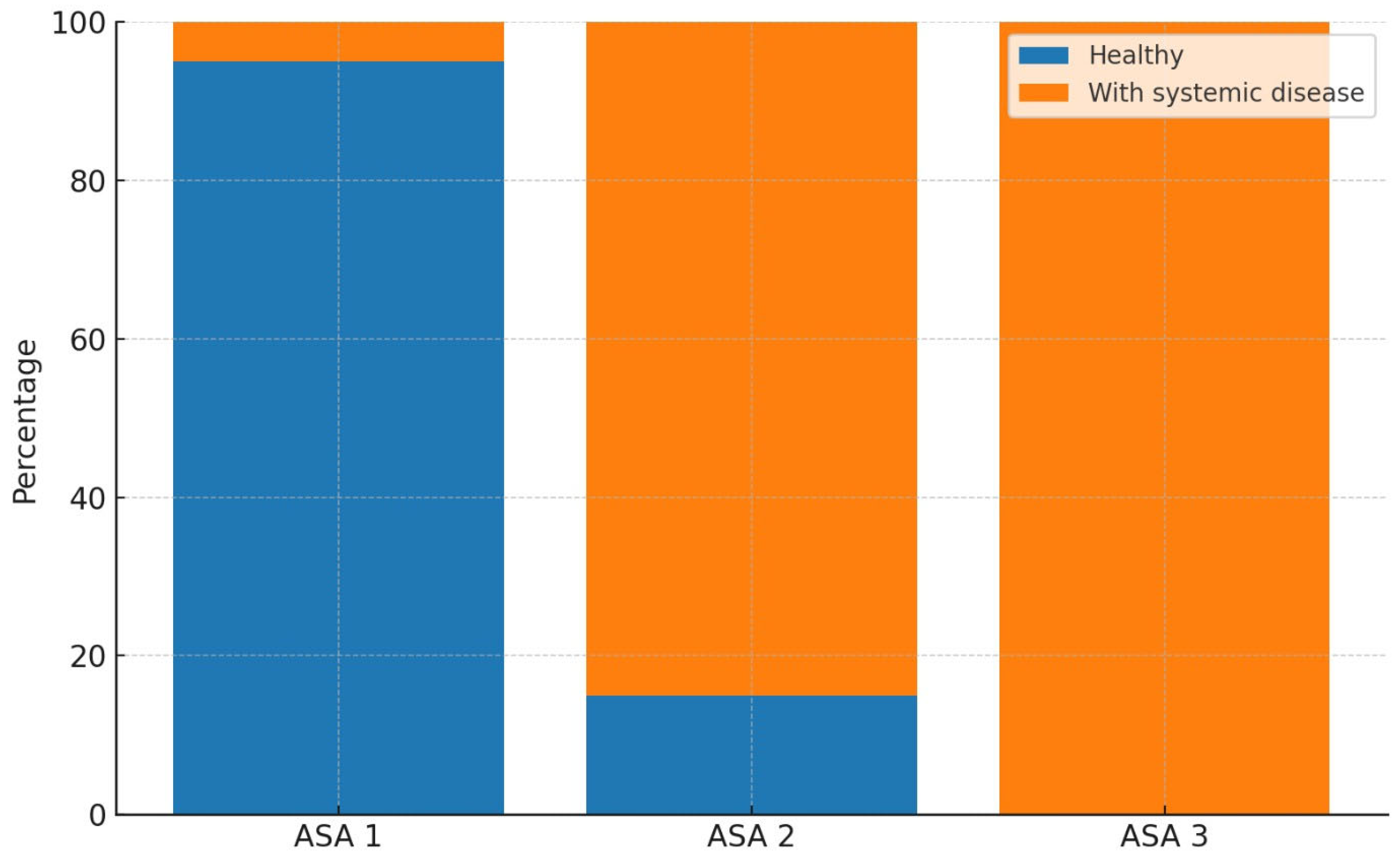

When examining the gender distribution among healthy children, the proportion of girls was 45.9%, while that of boys was 54.1%. In children with systemic diseases, the proportion of girls was 35.1%, and that of boys was 64.9%. A statistically significant relationship was found between gender and the presence of systemic disease (p = 0.046). Regarding the ASA classification among healthy children, 95.2% were classified as ASA 1, 4.8% as ASA 2, and 0% as ASA 3. Among children with systemic diseases, 10.8% were classified as ASA 1, 84.7% as ASA 2, and 4.5% as ASA 3. A statistically significant association was identified between ASA classification and the presence of systemic disease (p < 0.001) (

Table 5a). The distribution of systemic diseases according to ASA classifications was visualized using a 100% stacked column chart (

Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

100% stacked column chart showing the distribution of systemic diseases according to ASA classification.

Figure 2.

100% stacked column chart showing the distribution of systemic diseases according to ASA classification.

Among healthy children, 87.5% had not undergone scaling/polishing procedures, while 12.5% had received them. In contrast, within the group of children with systemic diseases, 70.3% had not received scaling/polishing, whereas the procedure had been performed in 29.7% of cases. The association between scaling/polishing and the presence of systemic disease was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.001). Regarding fluoride application, 81.6% of healthy children had not received fluoride treatment, while 18.4% had. In children with systemic diseases, 83.8% had not received fluoride application, and 16.2% had undergone the procedure. The analysis revealed no statistically significant association between fluoride application and the presence of systemic disease (p = 0.700) (

Table 5b).

Table 5.

a. Analysis of the association between systemic disease and categorical variables.

Table 5.

a. Analysis of the association between systemic disease and categorical variables.

| |

Healthy |

With systemic disease |

Test Statistic |

p-value |

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

Girl

|

162 (45.9) |

39 (35.1) |

3.980 |

0.046y |

|

Boy

|

191 (54.1) |

72 (64.9) |

|

|

| ASA Classification |

|

|

|

|

|

ASA 1

|

336 (95.2)a

|

12 (10.8)b

|

307.369 |

<0.001t |

|

ASA 2

|

17 (4.8)a

|

94 (84.7)b

|

|

|

|

ASA 3

|

0 (0)a

|

5 (4.5)b

|

|

|

Table 5.

b. Comparison of systemic disease with strip crown, scaling/polishing, and fluoride application.

Table 5.

b. Comparison of systemic disease with strip crown, scaling/polishing, and fluoride application.

| |

Healthy |

With systemic disease |

Test Statistic |

p-value |

| Strip Crown Application |

|

|

|

|

|

Not applied

|

352 (99.7) |

111 (100) |

— |

— |

|

Applied

|

1 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

|

|

| Scaling/Polishing Application |

|

|

|

|

| Not applied |

309 (87.5) |

78 (70.3) |

16.961 |

<0.001x |

| Applied |

44 (12.5) |

33 (29.7) |

|

|

| Fluoride Application |

|

|

|

|

| Not applied |

288 (81.6) |

93 (83.8) |

0.148 |

0.700x

|

| Applied |

65 (18.4) |

18 (16.2) |

|

|

Among healthy children, the median age was 6, whereas it was 8 among those with systemic diseases, and this difference was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.001). Regarding composite fillings, the median value was 6 in healthy children and 5 in children with systemic diseases; however, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.061). For stainless steel crowns, the median value was 1 in healthy children and 0 in those with systemic diseases, indicating a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001). The median values for pulp capping procedures did not differ significantly between the two groups (p = 0.014). A statistically significant difference was observed in the median values of pulpotomy treatments according to systemic health status (p < 0.001), with a median of 2 in healthy children and 1 in those with systemic diseases. The median value for root canal treatment was 0 in both groups, with no statistically significant difference based on systemic health status (p = 0.468). For fissure sealants, the median value was 0 in healthy children and 1 in those with systemic diseases, and this difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Lastly, the median number of tooth extractions was 3 in both groups, and no statistically significant difference was found (p = 0.326) (

Table 6).

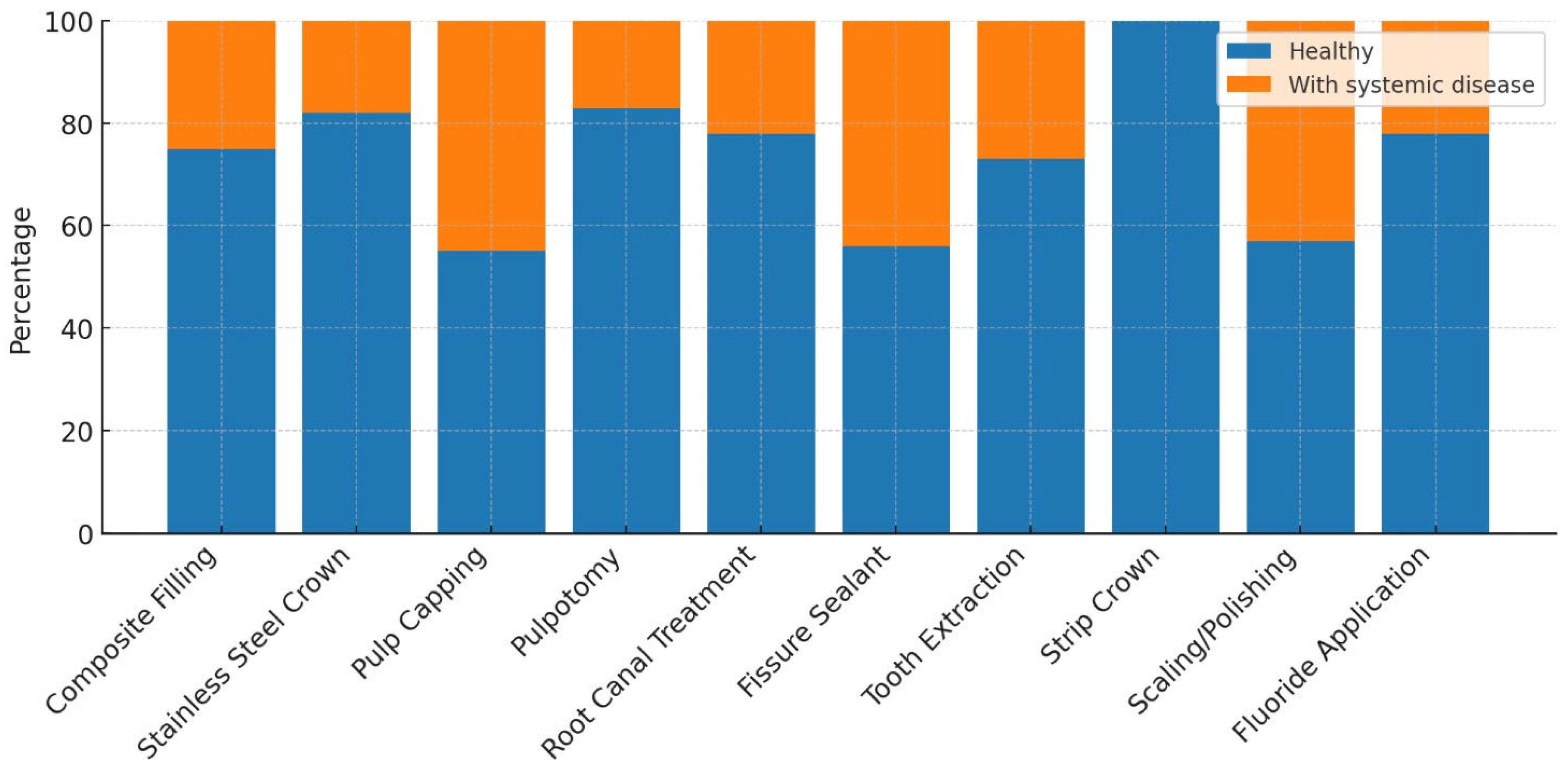

When examining the pediatric dental treatments performed, composite fillings were applied in 42.87% of healthy children and in 41.18% of children with systemic diseases. Composite filling was the most frequently performed treatment, accounting for 42.47% of all treated teeth. Stainless steel crown treatments were performed in 11.75% of healthy children, compared to 7.76% in children with systemic diseases. Pulp capping was rarely performed, with a rate of 0.1% in healthy children and 0.26% in those with systemic diseases. Pulpotomy was performed in 15.08% of healthy children and in 8.99% of children with systemic diseases. Root canal treatment was rarely administered in both groups, at rates of 0.46% for healthy children and 0.39% for those with systemic diseases. Fissure sealants were applied in 5.32% of healthy children and in 13.45% of those with systemic diseases. Tooth extraction was performed in 24.39% of healthy children and in 27.99% of children with systemic diseases. Strip crowns were applied only in healthy children, at a rate of 0.04%. A statistically significant relationship was found between the presence of systemic disease and both tooth extractions and fissure sealant treatments (p < 0.001). Additionally, a statistically significant association was observed between stainless steel crowns and pulpotomy treatments in healthy children (p < 0.001). No statistically significant differences were found between the two groups for the other treatment modalities (

Table 7). The distribution of systemic diseases by treatment type was visualized using a 100% stacked column chart (

Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

100% stacked column chart showing the distribution of systemic diseases according to treatments.

Figure 3.

100% stacked column chart showing the distribution of systemic diseases according to treatments.

Table 7.

Comparison of the number of treatments based on systemic disease status.

Table 7.

Comparison of the number of treatments based on systemic disease status.

| Treatment Type |

Healthy |

With systemic disease |

Total |

Test Statistic |

p-value |

| Composite filling (n) |

2160 (42.87) |

637 (41.18) |

2797 (42.47) |

157.181 |

<0.001 |

| Stainless steel crown (n) |

592 (11.75)a

|

120 (7.76)b

|

712 (10.81) |

157.181 |

<0.001 |

| Pulp capping (n) |

5 (0.1) |

4 (0.26) |

9 (0.14) |

157.181 |

<0.001 |

| Pulpotomy treatment (n) |

760 (15.08)a

|

139 (8.99)b

|

899 (13.65) |

157.181 |

<0.001 |

| Root canal treatment (n) |

23 (0.46) |

6 (0.39) |

29 (0.44) |

157.181 |

<0.001 |

| Fissure sealant (n) |

268 (5.32)a

|

208 (13.45)b

|

476 (7.23) |

157.181 |

<0.001 |

| Tooth extraction (n) |

1229 (24.39)a

|

433 (27.99)b

|

1662 (25.24) |

157.181 |

<0.001 |

| Strip crown (n) |

2 (0.04) |

0 (0) |

2 (0.03) |

157.181 |

<0.001 |

4. Discussion

Dental caries can lead to a variety of problems such as acute and chronic infections, pain, psychological disorders, sleep disturbances, behavioral changes, and difficulties in nutrition [

16]. It is known that untreated dental caries have negative effects on the quality of life of children [

17].

Behavior management techniques used in pediatric dentistry reinforce the sense of trust and facilitate the completion of treatment in cooperation by reducing stress and anxiety in children with high dental fear. However, for children and adolescents who cannot establish communication and cooperation due to psychological, emotional, mental, or physical conditions, dental treatment is performed under general anesthesia [

18,

19]. In our study, pediatric dental treatments performed under general anesthesia and sedation were evaluated in healthy children aged between 3 and 16 years, as well as in children and adolescents with systemic diseases or disabilities, who presented to our hospital between February 2023 and August 2024.

In the study by Zhao et al., it was observed that 48.94% of the 94 children examined were boys and 51.06% were girls. When analyzed by age groups, the highest proportion was found in the 4–5-year-old group with 44.68%, while the lowest proportion was among children under the age of 3, with 1.06%. Children aged 6 and above accounted for 9.57% of the study population [

2]. In the study conducted by Schulz-Weidner et al., a total of 325 children aged 0–18 years were evaluated. According to age distribution, 165 children were in the preschool period (mean age 4.0 ± 1.2), of whom 75 were girls, 87 were boys, and 3 were unspecified. The remaining 160 children were of school age (mean age 9.2 ± 2.7), with 66 girls, 92 boys, and 2 unspecified [

20]. In a study conducted in our country including 196 children aged between 1.6 and 11.8 years, the mean age was reported as 5.0 ± 1.9 years, with the study group consisting of 107 boys and 85 girls [

21]. In our study, the mean age of the children was 6.56 ± 2.44 years, and the median age was 6 years (min: 3, max: 16). These findings are consistent with similar studies in the literature and support that dental treatments under general anesthesia are predominantly concentrated in the preschool period.

In another study conducted in our country involving 1,536 children aged between 1 and 14 years, it was reported that 45.70% (702 girls) of the evaluated children were girls and 54.30% (834 boys) were boys. The average age of the girls was found to be 6.32 years, while that of the boys was 6.74 years [

22]. In the study by Bulut and Gönenç, it was reported that among 111 pediatric patients aged 1–12 years (mean age 5.28 ± 2.11) who completed their dental treatment under general anesthesia, 41 were girls and 70 were boys. They noted that approximately half (50.44%) of the treated children were in the 4–5 age group [

23]. Studies evaluating children undergoing dental treatment under general anesthesia have found that male patients outnumber female patients [

13,

24]. In our study, when the gender distribution of the children was evaluated, the proportion of male patients (56.7%) was found to be higher than that of female patients (43.3%). This finding is consistent with the results of similar studies in the literature. The more frequent reporting of cooperation problems during dental treatment in boys, and the observation that girls tend to be more compliant during clinical procedures, may be factors contributing to the increased need for general anesthesia among boys.

In terms of age groups, literature reviews also show that children receiving dental treatment under general anesthesia most frequently belong to the 5-year-old group [

25,

26]. When the age distribution of the 464 patients included in our study was examined, the highest proportion was found in the 5-year-old group, with 28.23%. This may be attributed to the intense anxiety, fear, and communication difficulties experienced by children in this age group during dental treatment.

In the study by Gezgin, 73.50% (n=1129) of the individuals were non-cooperative patients with whom communication could not be established using behavior management techniques, while 26.50% (n=407) were patients with disabilities or systemic diseases who did not allow treatment in a clinical setting. It was reported that 6.18% of these individuals had mental retardation, 4.81% had autism/atypical autism, 3.12% had Down syndrome, 2.08% had cerebral palsy, and 1.37% had epilepsy [

22]. In the study by Akdağ and Demir, it was reported that among 149 disabled patients treated under general anesthesia, 43.62% had mental retardation, 24.16% had epilepsy, 22.14% had autism, 11.4% had Down syndrome, and 10.73% had cerebral palsy [

27]. In the retrospective study conducted by Çiftçi and Yazıcıoğlu, 79.5% of the patients treated under general anesthesia were individuals with special needs, while 20.5% were healthy individuals. Among the special needs patients, the most frequently observed conditions were epilepsy (30.1%), various syndromes (14.7%), autism (14%), Down syndrome (13.6%), and cerebral palsy (7.3%) [

28]. In the study by Nasr and Moussa, out of 756 patients treated under general anesthesia, 641 were healthy non-cooperative individuals and 115 were patients with special needs. Among the special needs patients, the most commonly observed conditions were mental retardation (38.3%), cerebral palsy (20%), diabetes (13%), epilepsy (8.7%), and autism (7.8%) [

29]. In the study by Karl et al., it was reported that 13.5% of 1,155 patients treated under general anesthesia had systemic diseases, with the most common being neurodermatitis (4%), asthma (1.7%), and autism (1%) [

30]. In our study, 76.1% of the 464 children evaluated were healthy, while 23.9% had systemic diseases. The most frequently observed systemic conditions were autism (9.5%), mental retardation (2.2%), epilepsy (1.5%), cerebral palsy (1.5%), and Down syndrome (1.3%). The results of our study are consistent with the data in the literature.

Before dental treatments performed under general anesthesia, patients’ physical conditions are evaluated by anesthesiologists according to the ASA classification [

31]. In one study, out of 243 pediatric patients, 169 (69.6%) were classified as ASA 1, 70 (28.8%) as ASA 2, and 4 (1.6%) as ASA 3 [

32]. In the study by López-Velasco et al., 82.91% of the 192 patients were classified as ASA 1, 11.97% as ASA 2, and 5.13% as ASA 3 [

33]. In the study conducted by Gezgin, among the patients evaluated during preoperative anesthesia examinations, 1,164 (75.78%) were ASA 1, 321 (20.89%) were ASA 2, 47 (3.05%) were ASA 3, and 4 (0.28%) were ASA 4 [

22]. In our study, when the ASA classification distribution of the 464 evaluated patients was analyzed, 348 (75%) were ASA 1, 111 (23.9%) were ASA 2, and 5 (1.1%) were ASA 3. Similar to data reported in the literature, our study also found that a higher proportion of patients receiving dental treatment under general anesthesia were classified as ASA 1.

In the study by Akdağ and Demir, among 149 disabled patients treated under general anesthesia, 136 were classified as ASA 2 and 13 as ASA 3 [

27]. In the study by Yılmaz et al., of the 225 children examined, 131 had special healthcare needs and 94 were healthy but non-cooperative. In the special healthcare needs group, the proportion of male patients was higher (60.5%), while in the healthy and non-cooperative group, the gender distribution was balanced. According to ASA classification, most patients in the special healthcare needs group were ASA 2 (77.9%) and ASA 3 (15.3%), whereas in the other group, only ASA 1 and ASA 2 patients were observed, with no ASA 3 cases reported [

34]. In another study, it was reported that among patients with systemic diseases, the proportion of boys aged 2–5 years and girls aged 6–12 years was significantly higher (p=0.01). In the disabled patient group, the proportion of boys aged 6–12 years was significantly higher (p=0.01), and 75.7% of the patients were ASA 2, 16.1% were ASA 1, and 8.2% were ASA 3 [

35]. In our study, the proportion of boys among children with systemic diseases (64.9%) was found to be significantly higher than that of girls (35.1%) (p=0.046). Among healthy children, the vast majority were classified as ASA 1 (95.2%), and a small portion as ASA 2 (4.8%), whereas among those with systemic diseases, ASA 2 was predominant (84.7%), with lower rates of ASA 1 (10.8%) and ASA 3 (4.5%). A statistically significant association was found between ASA classification and the presence of systemic disease (

p<0.001). We believe that differences in gender distribution reported in the literature may be attributed to characteristics of the population, genetic factors, and environmental influences.

In a study examining the distribution of dental procedures performed under general anesthesia, restorative treatments were identified as the most frequently performed procedures (47.23%). These were followed by endodontic treatments (26.22%), tooth extractions (23.67%), and fissure sealant applications (2.86%). The majority of the endodontic treatments consisted of pulpotomies (84.37%), while a smaller portion were root canal treatments (15.63%). Additionally, 21.62% of the patients underwent scaling, and 37.83% received fluoride varnish. Fissure sealants were the least frequently performed procedure [

23]. In the study by Sarı et al., the most commonly performed treatments were restorative procedures (25.6%) and tooth extractions (20.10%) [

15]. In Gezgin’s study, the most frequently performed procedures under general anesthesia or sedation were restorative treatments (34.96%) and pulp amputations (31.62%), followed by root canal treatments, crown applications, extractions, and fissure sealants [

22]. In the study by Akdağ and Demir, restorative treatment (53.63%) was the most frequently performed procedure under general anesthesia, followed by tooth extraction (26.75%) and fissure sealant (9.7%). Pulpotomy, root canal treatment, scaling-polishing, fluoride, and curettage procedures were performed less frequently. These findings show that restorative treatments are the most frequently applied procedures, followed by extractions and fissure sealants [

27]. In Pecci-Lloret’s study, among 1,473 dental procedures performed on children with special healthcare needs under general anesthesia, the majority were restorative treatments (61%), followed by tooth extractions (21.7%), scaling (7.5%), pulpotomies (4.2%), stainless steel crowns (4%), and root canal treatments (1.6%). The most frequently performed individual procedure was composite fillings [

36]. In the study by Ehlers et al., the oral health of 134 children treated under general anesthesia with a history of early childhood caries (ECC) was assessed. All children received fillings, followed by tooth extractions (60%), fissure sealants (11.4%), and stainless steel crowns (8.6%) [

37]. In a study involving both healthy children and those with systemic diseases or disabilities treated under general anesthesia, 21.62% of the patients underwent scaling, while 37.83% received fluoride varnish [

26]. In our study, the dental procedures performed on pediatric patients were examined, and composite fillings (42.47%), tooth extractions (25.24%), and pulpotomies (13.65%) were found to be the most frequently performed treatments. Stainless steel crowns (10.81%) and fissure sealants (7.23%) were applied less frequently, while root canal treatment (0.44%) and pulp capping (0.14%) were performed at lower rates. Additionally, 16.6% of the patients received scaling/polishing, and 17.9% were treated with fluoride applications. The findings of our study are consistent with the existing literature and indicate that restorative and surgical procedures are the most commonly performed treatments in pediatric patients, whereas preventive procedures are less frequently applied.

In the study by Manmontri et al., a total of 72 strip crowns applied to 41 patients were evaluated after an average follow-up period of 21.7 months. The crowns were reported to be highly successful in terms of aesthetics (79.2%) and biological outcomes (84.7%), while the functional success rate remained low (52.8%) [

38]. In our study, strip crowns were among the least frequently performed procedures (0.03%). Considering this low frequency, we believe that more clinical applications and further evaluation of existing literature on strip crowns are needed.

In the study by Kaviani et al., the mean age of children with disabilities (6.5 years) was found to be statistically significantly higher than that of healthy children (4.5 years) [

39]. Similarly, in the study conducted by Baygın et al., the mean age of patients with disabilities was reported to be higher than that of healthy patients [

40]. In another similar study conducted in our country, the mean age of children with disabilities receiving dental treatment under general anesthesia (8.44 ± 0.37) was found to be significantly higher than that of healthy children (4.90 ± 0.15). It was noted that the timing of dental treatment in children with disabilities tended to occur at a later stage [

41]. Contrary to these findings, Yılmaz et al. reported no statistically significant difference in age between children with special healthcare needs and healthy, non-cooperative children [

34]. In our study, the median age of healthy children was determined to be 6 years, while that of children with systemic diseases was 8 years, and this difference was found to be statistically significant (

p<0.001). This finding suggests that systemic conditions may delay the initiation of dental treatment in children and that the need for special care could contribute to the postponement of such treatments.

It has been reported that children with medical conditions undergo more tooth extractions in both primary and permanent dentitions compared to healthy children. This has been attributed to the preference for simpler and more radical treatments to minimize the risk of complications and prevent the need for retreatment [

42]. Oral hygiene and health status in individuals with intellectual disabilities are poorer compared to their healthy peers, and as the degree of disability increases, oral health deteriorates further. In one study, it was found that individuals with intellectual disabilities aged 13–18 who were treated under general anesthesia required tooth extractions at a significantly higher rate than those in the healthy group [

15]. In a retrospective study evaluating 480 patients who received dental treatment under general anesthesia between 2008 and 2014, restorative treatments and extractions were reported as the most frequently performed procedures in individuals with mental retardation [

43]. It has also been reported that children with special healthcare needs treated under general anesthesia undergo more extractions and fewer pulp treatments compared to healthy children [

44].

In the study by Kaviani et al., the rate of tooth extraction was higher in children with disabilities compared to their healthy peers, while preventive treatments such as fissure sealants, fluoride applications, and preventive resin restorations, as well as pulp therapies, were significantly lower. No significant difference was noted in restorative treatments [

39]. In the study by Lee et al., dental treatments performed under general anesthesia were compared between healthy and disabled children, and it was reported that healthy children received more stainless steel crowns and pulp treatments, while disabled children underwent more tooth extractions [

45]. Similarly, in the study by Tsai et al., the frequency of tooth extractions was found to be higher in children with disabilities [

46]. In contrast, the study by Cantekin et al. reported no significant difference between healthy individuals and those with special healthcare needs in terms of restorative treatments, pulp therapies, and extractions [

13]. Likewise, Ibricevic et al. found no statistically significant difference in the number of extracted teeth between healthy and disabled individuals [

47]. Additionally, the study by Wang et al. reported that fissure sealants were more frequently applied to permanent teeth in patients with disabilities [

48]. In our study, tooth extractions and fissure sealants were significantly more common among children with systemic diseases, while stainless steel crowns and pulpotomies were significantly more frequent among healthy children (

p<0.001). No significant differences were observed in other treatment types. Our findings, in line with the literature, support the notion that more radical treatment approaches are preferred in children with disabilities to reduce the likelihood of repeat procedures and possible complications.

In a study conducted in our country, it was found that among patients aged 6–12 years, the rate of scaling procedures was statistically significantly higher in individuals with disabilities [

35]. Similarly, in our study, a statistically significant relationship was identified between scaling/polishing procedures and the presence of systemic disease. This finding may be associated with increased plaque accumulation in children with systemic conditions, which can result from factors such as medication use, impaired motor skills, dietary habits, and difficulties in maintaining oral hygiene.

In the study by Sevekar et al., fluoride application was reported to be more frequently performed in individuals with disabilities compared to healthy individuals [

44]. Biria et al. stated that regular fluoride application improves the success of dental treatments performed under general anesthesia [

49]. In contrast to the findings in the literature, our study did not reveal a statistically significant relationship between fluoride application and the presence of systemic disease. This result may be attributed to the lack of routine planning of fluoride applications in children with systemic conditions, variability in caregivers’ awareness levels, or differences in clinical practice patterns.

The results of this study should be interpreted within the context of certain limitations. Due to the retrospective design of our study, the data collection process was not directly controlled by the researcher; instead, the data were obtained based on patient records. The fact that this was a single-center study limits the generalizability of the findings to other geographic regions and healthcare institutions. Additionally, our research was limited to the treatment process and demographic data, and long-term outcomes such as post-treatment complications, restoration success, and recurrent dental problems could not be evaluated. Although the effects of systemic diseases on general anesthesia and dental treatment were examined, detailed analyses focusing on specific disease groups were limited. Therefore, further studies with larger sample sizes, prospective designs, and long-term follow-up data are needed.