1. Introduction

Sleep disorders in children are a growing global concern, with Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) emerging as a prevalent and potentially serious condition [

1,

2,

3]. OSA is characterized by recurring partial or complete upper airway obstruction during sleep, leading to breathing disruptions, oxygen desaturation, and sleep fragmentation [

2,

3]. Untreated sleep disorders can have detrimental consequences on a child's physical, cognitive, and behavioral development, including growth impairment, cardiovascular problems, learning difficulties, and behavioral issues [

1,

3].

Pediatric dentists' role is critical in early detection and management of pediatric OSA. They are usually the first to check on the oral sphere after the pediatric physician [

3,

4,

5]. As primary oral healthcare providers during a child's formative years, they are uniquely positioned to recognize subtle signs and symptoms of OSA that may be overlooked by parents or other physicians. Early identification is crucial for timely intervention and to minimize the long-lasting effects of untreated OSA [

3,

4].

However, accurately diagnosing OSA in children presents unique challenges due to subtle and varied symptom presentations. Unlike adults, excessive daytime sleepiness may not be a prominent symptom in children [

3,

6]. Instead, they might present with behavioral issues or learning difficulties [

1,

3].

Therefore, when screening for pediatric OSA, pediatric dentists should consider a comprehensive list of potential signs and symptoms, including the nocturnal signs such as habitual snoring (often loud and disruptive), witnessed pauses in breathing, labored or noisy breathing, restless sleep, unusual sleep positions, frequent awakenings, night sweats, and bedwetting. Additionally, daytime sleepiness (less common in children), behavioral problems (hyperactivity, inattentiveness, aggression), learning difficulties, morning headaches, and mouth breathing are also noticeable [

3,

6,

7].

Moreover, a definitive diagnosis of OSA in children necessitates a thorough evaluation process. First, a detailed history-taking by engaging parents as active informants is essential, as they are primary observers of their child's sleep behaviors [

3,

6]. Additionally, a comprehensive physical examination encompassing oral cavity inspection, tonsil size assessment using a standardized grading scale, observation for craniofacial anomalies (e.g., retrognathia, micrognathia), tongue size and nasal patency evaluation are critical [

7,

8]. On the other hand a polysomnography (PSG) which is the gold standard for OSA diagnosis should be performed. Nevertheless, access can be limited due to its performance in a hospital setting that requires patient stay overnight [

3,

6]. Alternative methods like home sleep apnea testing or nocturnal oximetry may be considered [

3].

Myofunctional Therapy (MT) has emerged since the 1900s as a promising non-invasive treatment for addressing underlying factors contributing to pediatric OSA [

9,

10]. Focusing on muscle function to correct malocclusion, it was first described in 1918 by Alfred Rodgers. It wasn’t until 1980, that prefabricated functional appliances were introduced [

10]. The effect of oropharyngeal exercises has been demonstrated in improving orofacial muscle function, promoting proper tongue posture and swallowing patterns, and facilitating nasal breathing, ultimately enhancing airway patency during sleep [

4,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Two types of MT are being used: the active therapy relies on specific exercises (tongue push-ups, cheek puffs and lip seal exercises) groups to strengthen the muscle groups whereas the passive approach utilizes specialized appliances that stimulate tongue activity and promote proper posture during sleep [

14].

Although MT is not the first line treatment in patients with OSA, considering applying it could lead to tangible clinical benefits [

15]. Whether the treatment proves successful or not, no possible harm is associated with the implementation of MT. Besides its numerous positive effects, this therapy is still not widely used, especially in Lebanon.

Hence, this study investigates the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Lebanese Pediatric dentists regarding pediatric OSA and the use of MT. A survey was conducted to assess their familiarity with the condition, diagnostic approaches, and treatment preferences, particularly focusing on the role of MT in their clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional survey assessed Lebanese pediatric dentists' experiences and perspectives on pediatric OSA and MT. The study included 103 dental faculty and practitioners specializing in pediatric dentistry registered with the Lebanese Society of Pediatric Dentistry (LSPD). Contact information was obtained from the LSPD membership directory. The survey was electronically distributed via Google Forms between March and April 2024. The 12-item online survey addressed: demographics, familiarity with OSA, diagnostic practices, treatment approaches, MT use, multidisciplinary collaborations, and challenges in diagnosis and treatment. The questions were written according to the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry clinical practice guidelines [

16]. The research team consisted of an associate professor specialized in pediatric dentistry, a dentistry student, and two medical students. This diversity of backgrounds and perspectives gave different dimensions to the design, data collection, and analysis processes of the study.

Data were analyzed using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (SPSS) for Windows, version 29.0. Descriptive statistics summarized the data: frequencies and percentages for categorical variables (specialty, familiarity with OSA, treatment approaches), and means, medians, standard deviations, and ranges for continuous variables (years of experience, number of OSA diagnoses per year). Additionally, Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were used to assess relationships between numerical variables. Meaningful correlations, which will be presented in the results, were defined as: ∣r∣>0.3 (moderate or stronger correlation) and p<0.05. A correlation matrix was generated to visualize significant relationships. Histograms, bar charts, and scatter plots visually presented the data.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Out of 103 contacted dentists, 62 responded to the survey.

Table 1 summarizes practice characteristics of participating Pediatric dentists.

As shown in

Table 2, the majority of respondents were Pediatric dentists (95.2%) familiar with OSA in children (86.8%). Most dentists have not considered Myofunctional Therapy as a standalone treatment (77.4%). However, among those who have used Myofunctional therapy, 55% reported patient improvement.

3.2. Familiarity and Diagnostic Practices

The number of diagnostic symptoms for diagnosis used varied. A positive correlation was observed between familiarity with OSA and the number of diagnostic symptoms considered (r = 0.330, p = 0.034). Dentists non familiar with OSA detected on average 3.6 symptoms among 9 listed in the survey. On the other hand, those familiar with OSA detected on average 6 symptoms.

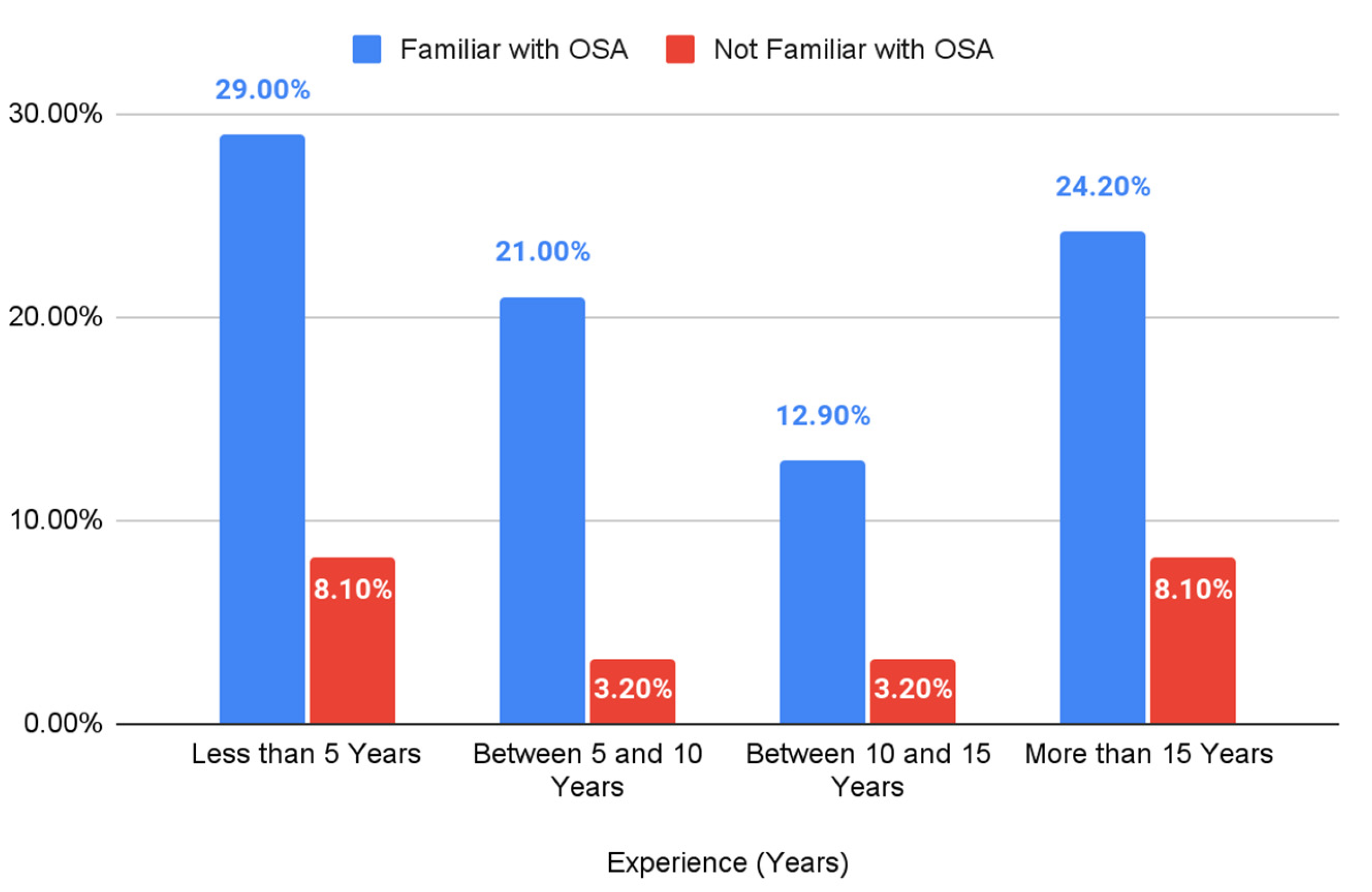

Figure 1 shows that the highest percentage of familiarity with OSA was observed in the least experienced group (less than 5 years) at 29.00%, while the lowest was in the 10-15 years of experience group at 12.90%. The percentage of dentists not familiar with OSA ranged from 3.20% to 8.10% across all experience levels.

3.3. Treatment Approaches and Myofunctional Therapy Use

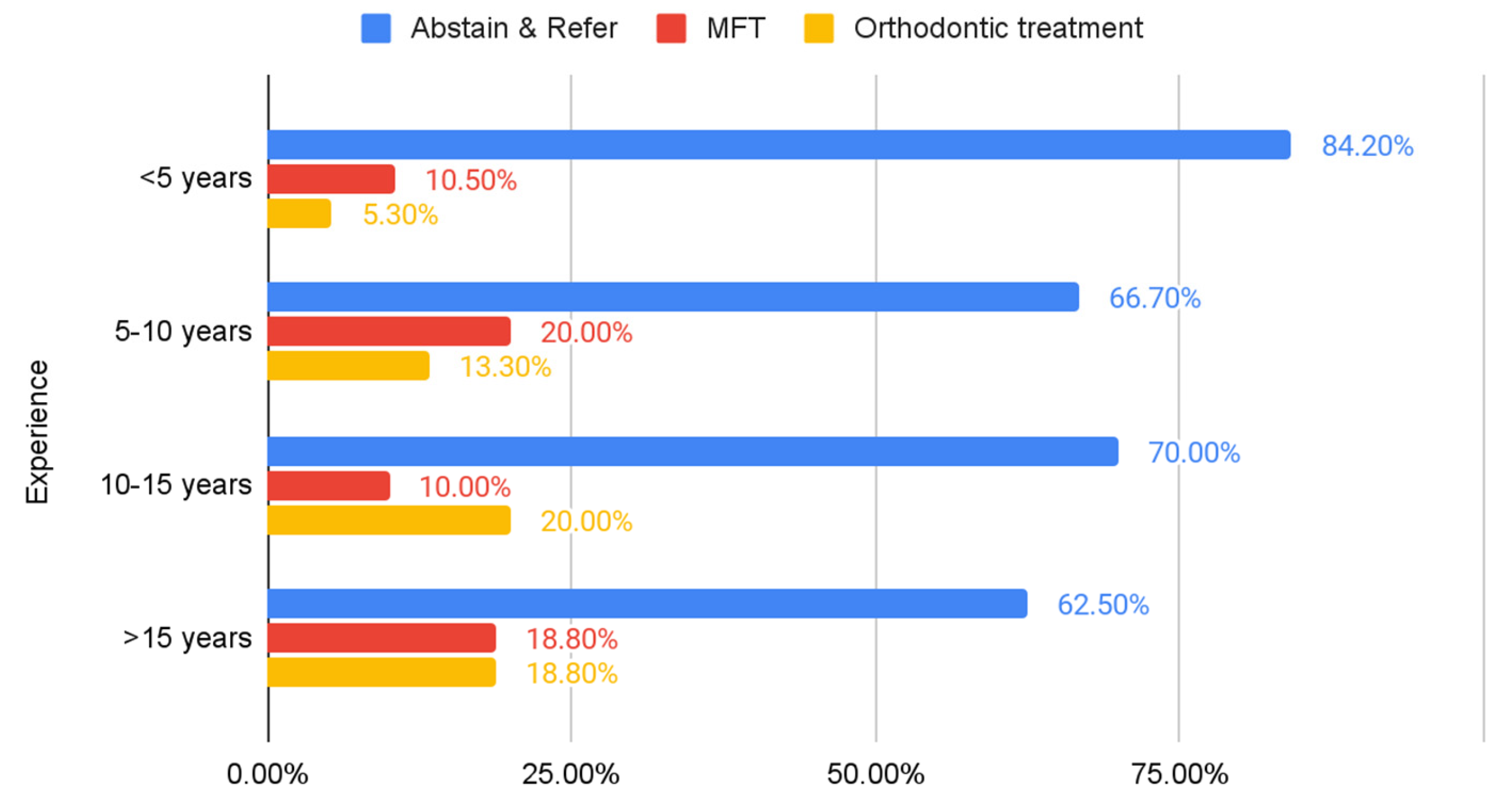

Figure 2 demonstrated that across all experience levels, the majority of dentists choose to abstain and refer, with this approach being most prevalent among those with less than 5 years of experience (84.20%) and least common among those with more than 15 years of experience (62.50%). The use of myofunctional therapy and orthodontic treatment varies across experience levels, with more experienced dentists generally showing a higher likelihood of using these approaches compared to their less experienced counterparts.

3.4. Collaboration and Challenges

The survey results revealed that ENT physicians were the most common referral specialists (80.9%), followed by orthodontists (50.0%). Pediatric physicians were also referred to by a substantial proportion of dentists (23.5%). A smaller number of referrals were made to pediatric dentists with specific myofunctional therapy training (8.0%), speech therapists (4.8%), sleep medicine specialists (1.6%), and physiotherapists (3.2%). It is important to note that some dentists listed multiple specialists, indicating a collaborative approach to managing pediatric OSA.

Table 3.

Percentage of referral specialists.

Table 3.

Percentage of referral specialists.

| Speciality |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

| ENT Physician |

51 |

82.3 |

| Orthodontist |

32 |

51.6 |

| Pediatric Physician |

15 |

24.2 |

| Pediatric dentist with Myofunctional Therapy experience |

5 |

8.0 |

| Speech Therapist |

3 |

4.8 |

| Sleep Medicine |

1 |

1.6 |

| Physiotherapist |

2 |

3.2 |

4. Discussion

The scope of dental practice has significantly broadened over the years. Dentists, especially Pediatric dentists, play a crucial role in detecting underlying medical conditions in patients seeking dental care [

2,

3,

4]. Specifically, OSA in children has been associated with a high risk of morbidity and mortality. Studies have demonstrated a prevalence of 1 to 4%, emphasizing the need for awareness among pediatric dentists [

5,

6]. Sleep disorders that go untreated can significantly impact a child's overall development, including stunted physical growth, potential heart problems, challenges with learning, and behavioral difficulties [

1,

3]. Specifically, a study on a Lebanese population investigated the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) among Lebanese children aged 3-12 years and its effects on their growth parameters. The results showed that 16.11% of children were at high risk of SDB, and there was a significant correlation between SDB and impaired growth parameters [

17]. Given these serious consequences, early diagnosis of sleep disorders in children is crucial.

Besides performing a polysomnography test, which is the gold standard for diagnosing OSA, pediatric dentists should be able to detect the various symptoms. The patient can present with enlarged tonsil size, a high Mallampati score, micrognathia, retrognathia, high arch palate, obesity, and snoring [

3,

18].

This study aimed to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Lebanese pediatric dentists towards pediatric OSA and the use of Myofunctional therapy. A survey was sent to 103 Lebanese Pediatric dentists registered in the Lebanese Society of Pediatric Dentistry (LSPD), aimed at assessing their knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards OSA in children.

Results show that the average experience level of responding dentists was between 10 and 15 years. There is a wide range in the number of OSA cases diagnosed per year, suggesting variability in practice patterns. Among dentists who utilize MT, there is a large variation in the percentage of patients treated with this approach. As shown in

Table 2, the majority of respondents were Pediatric dentists (95.2%) familiar with OSA in children (86.8%). Most dentists have not considered Myofunctional Therapy as a standalone treatment (77.4%), likely due to insufficient academic training on these kinds of therapies. However, among those who have used Myofunctional therapy, 55% reported patient improvement. In their systematic review and meta-analysis, Camacho et al. (2015) demonstrated a decrease in the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) by 62% in children who were treated with MT. The significant positive correlation between familiarity with OSA and the number of diagnostic symptoms used indicates that dentists who are less knowledgeable about the condition are less likely to consider a broader range of signs and symptoms [

17]. As a matter of fact, dentists unfamiliar with OSA detected on average 3.6 symptoms. On the other hand, those familiar with OSA detected on average 6 symptoms. This highlights the importance of raising awareness and knowledge about pediatric OSA among dental professionals.

Although not statistically significant at the standard level, the possible association between higher Pediatric dentists' experience and increased consideration of myofunctional therapy is interesting. It suggests that dentists who are more experienced might be more open to exploring various treatment options, including myofunctional therapy as shown in

Figure 2.

The level of OSA knowledge was associated with professionals' treatment confidence and their willingness to refer patients [

9]. The results showed a wide clinical referral behavior suggesting the need for a multidisciplinary approach to treat OSA. More than 80% of responders referred their patients to an ENT physician. Others suggested referring to an orthodontist (51.6%), pediatric physicians (23.5%), pediatric dentists with specific myofunctional therapy training (8.0%), speech therapists (4.8%), sleep medicine specialists (1.6%), and physiotherapists (3.2%) [

1]. Furthermore, pediatric dentists with higher experience decided to treat their patients rather than referring. These results suggest the importance of specific training not only in proper sleep disorder diagnosis and treatment approaches but also in referral options.

Most dental experts acknowledged the necessity of identifying patients with OSA and expanding their knowledge of associated issues. Hence, there is a need for enhanced education and training specifically focused on pediatric OSA, irrespective of professional experience [

9,

10,

17].

This study has limitations inherent to its cross-sectional design and reliance on self-reported data. The small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. Further research with larger and more diverse samples is needed to confirm and expand upon these results.

5. Conclusions

The results offer valuable insights into the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Lebanese pediatric dentists regarding pediatric OSA. Our findings underscore the need for heightened awareness, a more comprehensive consideration of diagnostic symptoms, and further exploration of MT as a treatment option. Continued research is vital to investigate the long-term effectiveness of MT in Lebanese children, identify ideal patient profiles, and gain a deeper understanding of the perspectives of both parents and pediatric dentists concerning this approach.

This study encourages Lebanese pediatric dentists to embrace MT as a potential treatment modality for pediatric OSA and to collaborate actively with other healthcare professionals to provide the best possible care for children affected by this condition. Although it has its limitations and needs specific appliances, MT has its indications and should be a complementary approach in pediatric dentistry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G.; Methodology, E.G.; Validation, M.N.G.; Formal Analysis, G.E.C.; Investigation, E.G.; M.E.K.; G.E.C.; Resources, M.N.G.; Data Curation, M.E.K.; G.E.C.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, E.G.; M.E.K.; Writing—Review and Editing, E.G.; M.E.K.; M.N.G.; Visualization, G.E.C.; Supervision, M.N.G.; Project Administration, E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Since our project does not include any intervention with human subject or include any access to identifiable private information, an IRB statement was not included

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the Lebanese Society of Pediatric dentistry members who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MT |

Myofunctional therapy |

| OSA |

Obstructive sleep apnea |

Appendix A

- -

General Dentist

- -

Pediatric dentistry

- 2.

Specify your experience:

- -

Less than 5 years

- -

Between 5 and 10 years

- -

Between 10 and 15 years

- -

More than 15 years

- 3.

Are you familiar with Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) in children?

- -

Yes

- -

No

- 4.

Based on which symptoms do you diagnose OSA? (Select all that apply)

- -

Snoring

- -

Hyperactivity

- -

Mouth breathing

- -

Sleep disruption

- -

Daytime sleepiness and fatigue

- -

Nocturnal enuresis (Bed wetting)

- -

Nocturnal sweating

- -

Agitated sleep

- -

Poor academic performance

- 5.

Based on which signs do you treat or refer? (Select all that apply)

- -

Size of the tongue compared to airway opening

- -

Tonsillar hypertrophy

- -

Adenoid facies

- -

Micrognathia

- -

Retrognathia

- -

High-arched palate

- -

Obesity

- 6.

What is the average number of patients you diagnose with OSA per year?

- -

0-20

- -

21-40

- -

41-60

- -

61-80

- -

More than 80

- 7.

What type of therapy are you more likely to prescribe to your patients? (Select all that apply)

- -

Myofunctional therapy (strengthening exercises + appliance)

- -

Mandibular advancement (Herbst, Twin Block, Bionator, Frankel)

- -

Rapid Maxillary Expansion

- -

Weight loss (diet, etc.)

- -

Abstain treatment and refer to a specialist

- 8.

To which specialist do you refer pediatric OSA patients? (Select all that apply)

- -

ENT physician

- -

Pediatric physician

- -

Orthodontist

- -

Physiotherapist

- -

Other: ___________

- 9.

Did you ever consider using myofunctional therapy alone as a treatment?

- -

Yes

- -

No

- 10.

What is the percentage of sleep disorders patients that you treated with myofunctional therapy?

- 11.

Did the patients' symptoms improve after the use of myofunctional therapy?

- -

Yes

- -

No

- -

Not applicable, I never prescribe myofunctional therapy

- 12.

In your opinion, why didn't myofunctional therapy work in certain patients? Or why it may not work? (Select all that apply)

- -

Treatment interruption

- -

Complexity of the condition

- -

Ineffective method

- -

Other treatments are better and more effective

References

- Zaffanello, M.; Pietrobelli, A.; Nosetti, L.; Ferrante, G.; Rigotti, E.; Ganzarolli, S.; Piacentini, G. Sleep-Disordered Breathing and Central Respiratory Control in Children: A Comprehensive Review. Children 2025, 12, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders: Third edition, text revision (ICSD-3-TR) – Supplemental material. 2023. Available online: https://aasm.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/ICSD-3-Text-Revision-Supplemental-Material.

- Moin Anwer, H.M.; Albagieh, H.N.; Kalladka, M.; Chiang, H.K.; Malik, S.; McLaren, S.W.; Khan, J. The role of the dentist in the diagnosis and management of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Saudi Dent. J. 2021, 33, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzzi, V.; Ierardo, G.; Di Carlo, G.; Saccucci, M.; Polimeni, A. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in the pediatric age: the role of the dentist. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23(1 Suppl), 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Sharma, R. Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Diagnostic Challenges and Management Strategies. Cureus 2024, 16, e75347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Wu, P.Y.; Hong, S.Y.; Chang, Y.T.; Lin, S.S.; Chou, I.C. The Role of Polysomnography for Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Life 2025, 15, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harari, D.; Redlich, M.; Miri, S.; Hamud, T.; Gross, M. The effect of mouth breathing versus nasal breathing on dentofacial and craniofacial development in orthodontic patients. Laryngoscope 2010, 120, 2089–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, H.V.M.; Schroeder, J.W.; Gang, Z.; Sheldon, S.H. Mallampati score and pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 2014, 10, 985–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, M.; Certal, V.; Abdullatif, J.; Zaghi, S.; Ruoff, C.M.; Capasso, R.; Kushida, C.A. Myofunctional Therapy to Treat Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sleep 2015, 38, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wishney, M.; Darendeliler, M.; Dalci, O. Myofunctional therapy and prefabricated functional appliances: An overview of the history and evidence. Aust. Dent. J. 2019, 64, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanao, A.; Mashiko, M.; Kanao, K. Application of functional orthodontic appliances to treatment of “mandibular retrusion syndrome.” - Effective use of the TRAINER SystemTM. Jpn. J. Clin. Dent. Child. 2009, 14, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Quadrelli, C.; Gheorgiu, M.; Marchetti, C.; Ghiglione, V. Early myofunctional approach to skeletal Class II. Mondo Ortodontico 2/2002, 109-122.

- Scribante, A.; Pascadopoli, M.; Zampetti, P.; Rocchi, C.; Falsarone, F.; Sfondrini, M.F. Changes in the Upper Airway Dimension Following the Use of Functional Appliances in Children with Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Systematic Review. Children 2025, 12, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Kaneshiro, K.; Camacho, M. Effect of myofunctional therapy on children with obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Sleep. Med. 2020, 75, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.G.D.A.; Miranda, V.S.G.; Baseggio, M.E.P.; Marcolino, M.A.Z.; Vidor, D.C.G.M. Myofunctional Therapy for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2025, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, C.L.; Brooks, L.J.; Ward, S.D.; Draper, K.A.; Gozal, D.; Halbower, A.C.; Jones, J.; Lehmann, C.; Schechter, M.S.; Sheldon, S.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Childhood Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e714–e755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katramiz, M.; Saade, A.; Ojaimi, M.; Gholmieh, M. Effect of Sleeping Disorders on the Growth Parameters of Lebanese Children. Mater. Sociomed. 2023, 35, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosetti, L.; Zaffanello, M.; Simoncini, D.; Dellea, G.; Vitali, M.; Amoudi, H.; Agosti, M. Prioritising Polysomnography in Children with Suspected Obstructive Sleep Apnoea: Key Roles of Symptom Onset and Sleep Questionnaire Scores. Children 2024, 11, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).