Introduction

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (“OSA”) is a highly prevalent disease across diverse populations including an estimated 176 million in China, 54 million people in the USA, 52 million in India, 49 million in Brazil, 26 million in Germany, and 24 million people in France with an apnea-hypopnea index (“AHI”) greater than 5 events per hour [

1]. If left untreated, OSA is linked with elevated risks of comorbidities [

1], reductions in quality of life and increased economic expense [

2].

The pathophysiology of OSA involves the narrowing of airway anatomy, making the velopharyngeal and oropharyngeal airway segments susceptible to recurrent collapses during sleep breathing that deprive vital organs of oxygen [

3]

,v. Prior research identifies that 97% of airway collapse events involve the velopharynx while 56% of events involve the oropharynx [

4]. The AHI, which is the average count of collapse events per hour, is used to quantify the severity of the disease. An AHI between five to fifteen events per hour is considered mild sleep apnea; fifteen to thirty events per hour is considered moderate; and more than 30 events per hour is considered severe [

5]. Treatment success is often determined based on how well the therapy improves AHI relative to the baseline.

Due to limitations of existing treatment options, sleep medicine professionals are evaluating new approaches for treating patients with OSA. For example, continuous positive airway pressure (“CPAP”) has demonstrated success reducing AHI, but emerging research also associates CPAP with counterproductive side effects [

6] and low levels of compliance [

7]. Surgical options have demonstrated modest reductions in AHI, but often involve non-reversible, invasive procedures, require preselection procedures such as drug induced sleep endoscopy, and are linked with adverse events [

8] and significant expenses [

9]. Traditional oral appliance therapy (“OAT”) is associated with relatively higher adherence, but utilization is suppressed by inconsistent efficacy

vi. It is also thought that OAT utilization is further limited by a paucity of published clinical data.

Materials and Methods

This study was a retrospective chart review of patients from a single dental sleep medicine practice with multiple locations. The design is organized and described according to the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes (“PICO”) format [

10]. For clarity, the Intervention component is divided into two sections. The first describes the treatment protocol. The second describes the medical device used in this study.

Population

Sixty patients diagnosed with OSA were referred to the Sleep Better Austin (“SBA”) organization for OAT. All sixty patients completed the treatment protocol. This study population was segmented by OSA severity classification to facilitate post-hoc analyses. Forty-four of the sixty patients, 73.3% of the study population, presented with mild OSA. Sixteen patients, 27% of the study population, presented with moderate or severe OSA, with 18.3% and 8.3% being moderate and severe, respectively.

Intervention, Protocol

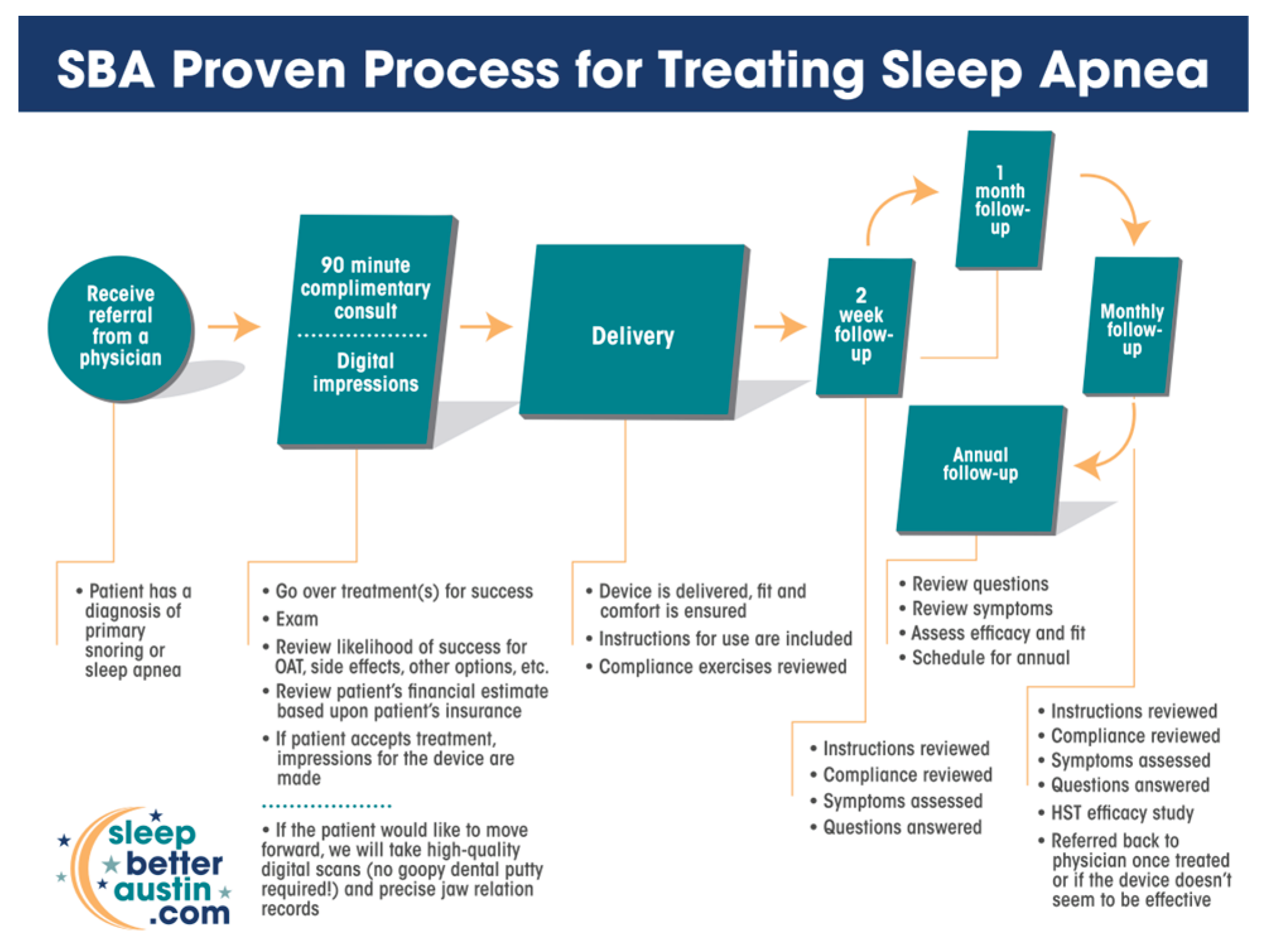

Patients were referred to SBA for OAT after being screened, tested and diagnosed with OSA by a managing physician. The protocol described in Chart 1 and below was implemented consistently for each patient enrolled in this study, across seven SBA clinic locations in the Austin, Texas metropolitan area (Southwest, Central, Cedar Park, Georgetown, Kyle, Killeen, and Waco), involving multiple SBA team members.

Table 1.

The Sleep Better Austin Treatment Protocol Map.

Table 1.

The Sleep Better Austin Treatment Protocol Map.

The first step of the SBA OAT treatment process was the consultation. SBA invested approximately 90 minutes in each consultation. The consultation included an oral/dental examination to ascertain suitability for OAT, and an evaluation for contraindications and risks of side effects. The consultation also included a review of medical insurance coverage.

SBA captured digital records of the patient’s oral structures immediately following the consultation if the patient agreed to treatment. Digital records included 1. a digital scan of the patient’s upper teeth; 2. a digital scan of the patient’s lower teeth; and 3. a digital scan of the therapeutic mandibular position. The therapeutic mandibular position was achieved using a George Gauge tool. The therapeutic mandibular position was established at 50%-60% of each patient’s maximum protrusive range of motion. This package of digital records, along with a digital prescription, was electronically transmitted to the manufacturer (ProSomnus Sleep Technologies, Pleasanton, CA) to fabricate the precision-custom OAT device.

The second step of the SBA process was delivery of the precision-custom OAT device. During the delivery appointment, SBA’s team ensured the fit and comfort of the device. Instructions were provided on how to insert, remove and care for the OAT device. Compliance exercises were reviewed.

The third step of the SBA process was the initial follow up appointment. The follow up appointment was conducted approximately 2-weeks after delivery of the OAT device. During this follow up appointment the SBA team reviewed instructions, compliance, symptoms and answered any questions that each patient might have.

The fourth step of the SBA process was the monthly follow up sequence. Patients were scheduled for monthly follow up visits to review instructions, compliance, and symptoms. A type-3 home sleep test (NightOwl, Resmed, San Diego, CA) was utilized to assess response to treatment and optimize titration. Patients were referred to their managing physician for confirmation testing and placed on an annual recall schedule if they successfully responded to therapy.

Intervention, Oral Appliance

An FDA cleared, precision-custom OA (ProSomnus EVO, Pleasanton, CA) was used to treat patients enrolled in this study. Precision-custom means that each device is 100% custom made from the oral records for each individual patient [

11]. Unlike traditional oral appliances that rely on prefabricated, non-custom components, such as screws, mechanical hinges, nylon rods or elastomeric straps, to reposition, stabilize and titrate the mandible, precision-custom devices do not have prefabricated items [

12]. Avoiding prefabricated items, and the modification steps required to embed them into devices, eliminates tolerance stacks, optimizing personalization, and reducing variability in performance [

13].

Figure 1.

ProSomnus EVO Precision-custom Oral Appliance.

Figure 1.

ProSomnus EVO Precision-custom Oral Appliance.

This OA is also entirely made from a material that satisfies the US Pharmacopeia’s requirements for the Medical Grade Class VI designation [

14]. Class VI represents US Pharmacopeia’s highest standard for medical device material biocompatibility.

This precision-custom OA also uses a familiar and clinically proven dual post design for repositioning, stabilizing and titrating the mandible into the prescribed therapeutic location. Titration is accomplished with a stepwise sequence of trays, each with a different, prescribed, protrusive setting. This stepwise titration approach offers many benefits to both the provider and the patient including: definitive titration, easier communication, enhanced durability, smaller volume in the mouth, and the elimination of metal components.

Comparison

This investigation was a matched pair study design. It compared baseline OSA values for each patient against residual OSA values with the therapeutic oral device in situ.

Baseline OSA, assessed using AHI (events per hour), was the primary basis for comparison.

Outcomes

Providers critically evaluated success by comparing the actual treatment outcomes relative to pre-determined performance goals. Performance goals were established by referring physicians, and according to normal and customary criteria, specifically:

The primary performance goal of 65% of patients achieving the primary endpoint of AHI < 10 events per hour with the OA in situ was based on the literaturexii.

Compliance and safety were evaluated during follow-up visits, based upon oral examinations and subjective patient feedback.

Statistical Methods

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism v10.0 (GraphPad Software, LLC, Boston, MA). Significance level was set at α = 0.05 using two-sided statistical testing. Non-parametric statistical methods were used due to the non-normal distribution of the AHI metric. Descriptive statistics include the mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range.

Results, All OSA Severities

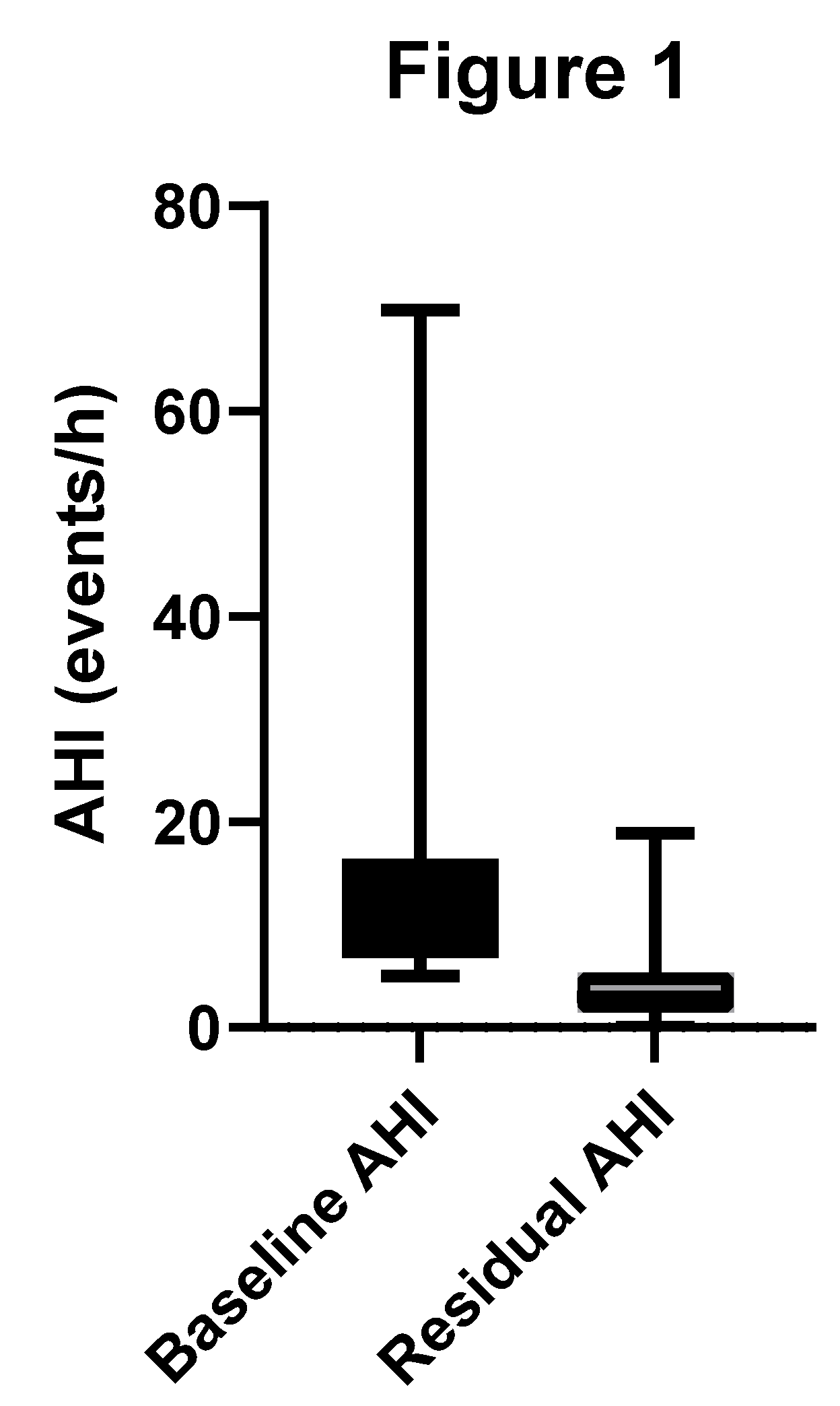

The mean baseline AHI for our study population of sixty patients was 14.0 ±11.3 (range: 5.0-69.8) events per hour and a median of 10.3 (IQR 9.7) events per hour. The mean baseline AHI for the mild cohort was 8.8 ± 2.7 (range: 5.0-14.9) events per hour. The mean baseline AHI for the moderate to severe cohort was 28.2 ± 13.6 (range: 15.1-69.8) events per hour.

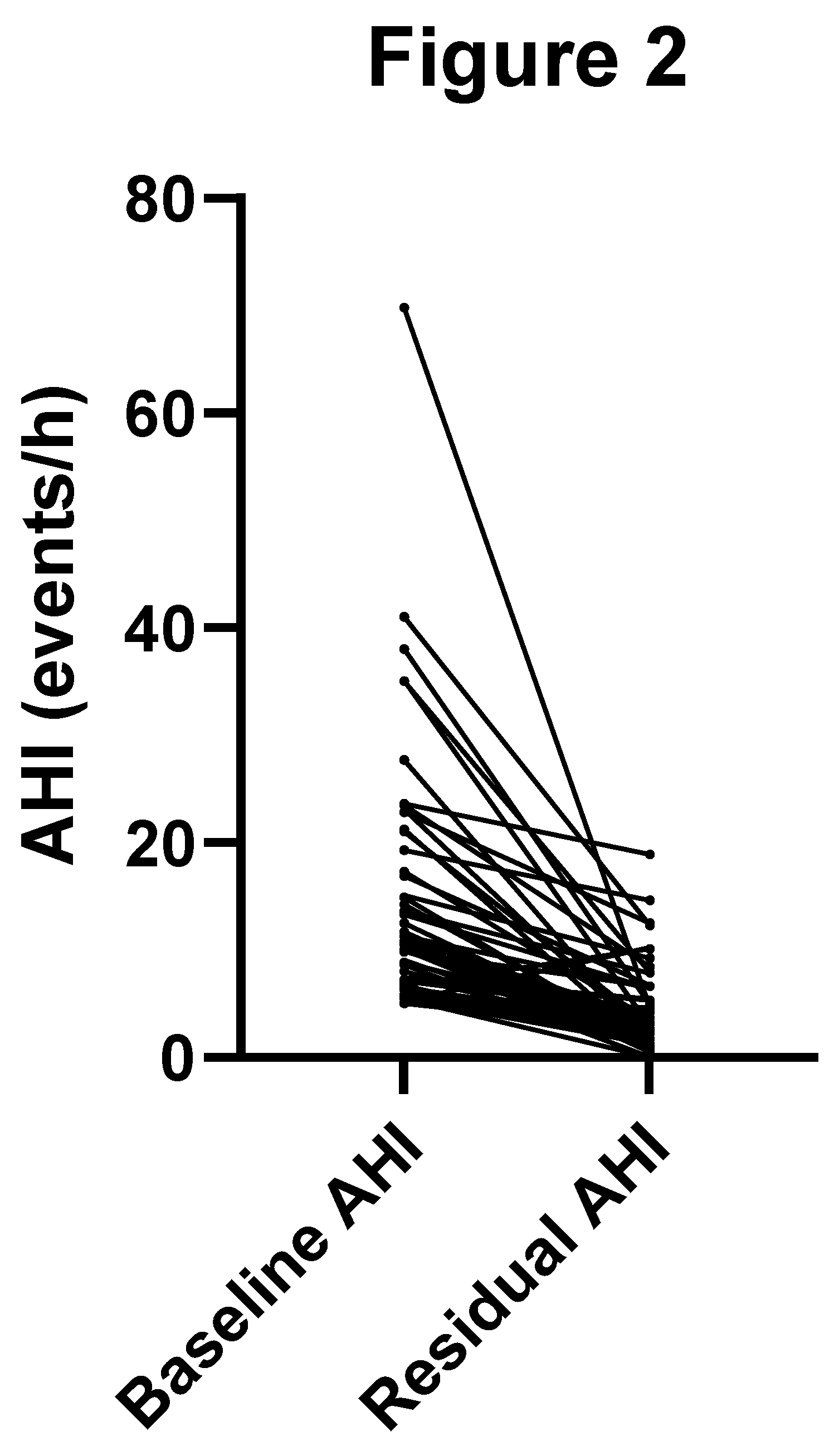

Treatment with OAT reduced the mean AHI by 9.8 events per hour, representing a 63% improvement relative to baseline. The mean AHI with OAT was reduced to 4.2 ±3.8 (range: 0.0-18.9) events per hour and a median of 3.0 (IQR 3.9) events per hour. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicated a significant reduction in AHI from baseline to outcome (p < 0.001).

Figure 1 shows a box-and-whisker plot of baseline and residual AHI.

Fifty-four of 60 (90%) patients achieved the primary threshold for therapeutic success, defined as AHI < 10. This result of 0.9 [95% CI 0.79-0.96] met the performance target of 0.65 (65%) of patients achieving a residual AHI < 10.

Figure 2 displays the matched pair change in AHI.

Fifty-eight of sixty (97%) patients demonstrated an improvement in AHI with OAT. The two patients who did not experience a decrease in their AHI with OAT had mild OSA at baseline and a negligibly higher AHI (still in the mild range) with OAT.

Fifty two of sixty (87%) patients improved by at least one severity classification with OAT. Chart 3 details the changes in OSA severity classification on a patient-by-patient basis. With OAT, zero patients were identified as having a Severe OSA classification and one patient was identified as having Moderate OSA.

Table 3.

Change in OSA Severity Classification, by Patient.

Table 3.

Change in OSA Severity Classification, by Patient.

| Patient # |

Baseline Severity |

Residual Severity |

| 1 |

Severe |

No OSA |

| 2 |

Severe |

Mild |

| 3 |

Severe |

No OSA |

| 4 |

Severe |

No OSA |

| 5 |

Severe |

Mild |

| 6 |

Moderate |

No OSA |

| 7 |

Moderate |

Moderate |

| 8 |

Moderate |

Mild |

| 9 |

Moderate |

No OSA |

| 10 |

Moderate |

Mild |

| 11 |

Moderate |

No OSA |

| 12 |

Moderate |

No OSA |

| 13 |

Moderate |

Mild |

| 14 |

Moderate |

No OSA |

| 15 |

Moderate |

Mild |

| 16 |

Moderate |

Mild |

| 17 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 18 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 19 |

Mild |

Mild |

| 20 |

Mild |

Mild |

| 21 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 22 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 23 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 24 |

Mild |

Mild |

| 25 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 26 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 27 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 28 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 29 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 30 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 31 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 32 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 33 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 34 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 35 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 36 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 37 |

Mild |

Mild |

| 38 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 39 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 40 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 41 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 42 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 43 |

Mild |

Mild |

| 44 |

Mild |

Mild |

| 45 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 46 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 47 |

Mild |

Mild |

| 48 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 49 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 50 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 51 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 52 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 53 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 54 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 55 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 56 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 57 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 58 |

Mild |

No OSA |

| 59 |

Mild |

Mild |

| 60 |

Mild |

No OSA |

Seventy three percent of the total study population, 44 of 60 patients, achieved the secondary performance goal of a residual AHI < 10 and ≥ 50% improvement over baseline.

Results, Moderate to Severe OSA Subgroup

For the sixteen of sixty (27%) of patients diagnosed with moderate or severe OSA, the mean AHI improved by 70%, 21.1 events per hour, from a baseline of 28.2 ± 13.6 (median 23.3 [IQR 15.4]) to 7.1 ± 5.3 (median 7.1 [IQR 8.6]) with OAT. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicated a significant reduction in AHI from baseline to residual (p < 0.0001). Additionally, all matched pair differences were positive, indicating that the residual values were consistently lower than the baseline values. The maximum residual AHI for the moderate to severe subgroup was 18.9 events per hour. The minimum residual AHI was 1.6 events per hour.

Twelve of 16 (75%) patients with baseline moderate to severe OSA achieved a residual AHI < 10 with OAT. Twelve of 16 (75%) patients with baseline moderate to severe OSA achieved a residual AHI < 20 with ≥ 50% reduction from baseline, and all 5 (100%) patients classified with baseline severe OSA achieved a residual AHI < 20 with ≥ 50% reduction from baseline. Fifteen of 16 (94%) patients classified with moderate or severe OSA demonstrated improvement by at least one OSA classification strata, with a mean improvement of 1.7 classification strata.

After follow-up appointments, 60 of 60 patient were continuing therapy. No patients required unscheduled interventions for adverse side effects. Any side effects reported, including dry mouth, tooth soreness, jaw soreness or general discomfort were non-serious, transient, and did not compromise the continuation of treatment.

Discussion

The results of this investigation demonstrate that OAT for the treatment of OSA, when delivered by experienced providers using a comprehensive treatment protocol and a precision-custom OA, significantly reduce AHI across all severities of OSA. With a mean AHI reduction of 63% and 90% of patients achieving a residual AHI < 10, the primary performance goal was met, exceeding the expected 65% threshold with a lower 95% CI of 79%. Of the six patients who did not meet the primary performance goal, three demonstrated an improvement in OSA severity classification.

These findings align with prior studies

xii,xv, [

15], which reported high efficacy of precision-custom OAT devices due to their personalized design, absence of prefabricated components, and biocompatible materials. Although not a comparative study design, these results are also different from the findings of investigations involving other oral devices for the treatment of OSA that reported lower levels of efficacy [

16,

17,

18]. The significant reduction in AHI demonstrated in this study underscores the potential of this therapy to address airway collapse effectively.

Notably, the moderate to severe OSA subgroup experienced a substantial reduction in AHI of 75% from baseline, with 100% of severe patients achieving a residual AHI < 20 and ≥50% reduction from baseline. This is particularly encouraging, as moderate to severe OSA is often more challenging to treat non-invasively or without continuous positive airway pressure (“CPAP”).

The success in the moderate to severe OSA subgroup may be attributed to the precision-custom design, which eliminates variability from prefabricated componentsxiv. The systemized clinical follow up process, in conjunction with the stepwise titration approach of the precision-custom OA, likely further enhanced efficacy by allowing precise mandibular positioning tailored to each patient’s therapeutic response and needs.

Compared to existing treatments, precision-custom OAT may offer advantages over CPAP, traditional, semi-custom oral appliances, and surgical options. While CPAP is effective in reducing AHI, its association with side effects and low compliance limits its long-term utility. Traditional, semi-custom oral appliances exhibit relatively better adherence rates, but utilization is constrained by inconsistent efficacy and durability. Surgical interventions, though effective in some cases, carry risks of adverse effects and high costs. In contrast, the high compliance rate and absence of serious adverse events demonstrated in this study suggest that precision-custom OAT may address these limitations, offering a balance of efficacy, safety, and patient adherence. These findings are consistent with a previously reported, head to head cross over study comparing the mean disease and mean risk alleviation of precision-custom oral devices and CPAP [

19]. The use of medical-grade Class VI materials and the elimination of prefabricated components likely contributed to the reported continuing usage and minimal transient side effects, such as dry mouth or jaw soreness.

This study’s findings also highlight the importance of a structured treatment protocol. SBA’s process, including detailed consultations, digital records of each patient’s oral structures, and regular follow-ups with home sleep testing, likely optimized patient outcomes by ensuring proper device fit, proper and stable mandibular repositioning, patient education, and outcome-oriented titration adjustments. This contrasts with traditional OAT, where inconsistent efficacy and limited clinical data have hindered performance and adoption.

Despite these strengths, this study has limitations. The sample size of sixty patients, while sufficient for demonstrating statistical significance, may not fully represent the broader OSA population, particularly given the predominance of mild OSA cases (73.3%). Additionally, the study was conducted at a single organization (SBA), which may introduce site-specific biases related to provider expertise or patient demographics. The reliance on home sleep testing for assessing treatment response, while practical, may not be as precise as polysomnography, the gold standard for AHI measurement. This study utilized single-night testing, which has been associated with frequent misclassification of OSA severity relative to multi-night testing [

20,

21]. The study did not assess long-term outcomes beyond the initial follow-up period, limiting insights into sustained efficacy or compliance. And finally, research reports that the AHI, in general and as utilized in this study, is not a good predictor of health outcomes for patients with OSA [

22]. Further, these results might not be generalizable to traditional oral appliances, or centers that do not follow a similar, comprehensive treatment protocol.

Future research should address these limitations by including larger, more representative populations and incorporating polysomnography, multi-night testing, and/or more predictive biomarkers such as hypoxic burden, for more robust outcome validation. Longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate the durability of AHI reductions and compliance over time. Additionally, comparative studies pitting precision-custom OAT against CPAP or surgical options in randomized controlled trials could further clarify the relative efficacy and cost-effectiveness of these therapies. Exploring the impact of precision-custom OAT on quality of life, comorbidities, and economic outcomes, would also strengthen the case for broader adoption of OAT with precision-custom OA’s.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that precision-custom OAT, combined with a structured treatment protocol, is a highly effective and well-tolerated therapy for OSA. The significant AHI reductions, high compliance, and minimal side effects position this approach as a promising alternative to existing treatments. Addressing the identified limitations through further research will be critical to optimizing its role in sleep medicine.

References

- Benjafield AV, Ayas NT, Eastwood PR, Heinzer R, Ip MSM, Morrell MJ, Nunez CM, Patel SR, Penzel T, Pépin JL, Peppard PE, Sinha S, Tufik S, Valentine K, Malhotra A. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Aug;7(8):687-698. [CrossRef]

- Lévy P, Kohler M, McNicholas WT, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015 ;1:15015.

- Young T, Peppard PE, Gottlieb DJ. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002 May 1;165(9):1217-39. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remmers JE, deGroot WJ, Sauerland EK, Anch AM. Pathogenesis of upper airway occlusion during sleep. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1978;44(6):931-8.

- Watanabe T, Isono S, Tanaka A, Tanzawa H, Nishino T. Contribution of body habitus and craniofacial characteristics to segmental closing pressures of the passive pharynx in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002 Jan 15;165(2):260-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramar, K.; Dort, L.C.; Katz, S.G.; Lettieri, C.J.; Harrod, C.G.; Thomas, S.M.; Chervin, R.D. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Snoring with Oral Appliance Therapy: An Update for 2015. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2015, 15, 773–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peker Y, Celik Y, Behboudi A, Redline S, Lyu J, Wei Y, Gottlieb DJ, Jelic S. CPAP may promote an endothelial inflammatory milieu in sleep apnoea after coronary revascularization. EBioMedicine. 2024 Mar;101:105015. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pépin, J.L.; Woehrle, H.; Liu, D.; Shao, S.; Armitstead, J.P.; Cistulli, P.A.; Benjafield, A.V.; Malhotra, A. Adherence to Positive Airway Therapy After Switching From CPAP to ASV: A Big Data Analysis. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2018, 15, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strollo PJ Jr, Soose RJ, Maurer JT, de Vries N, Cornelius J, Froymovich O, Hanson RD, Padhya TA, Steward DL, Gillespie MB, Woodson BT, Van de Heyning PH, Goetting MG, Vanderveken OM, Feldman N, Knaack L, Strohl KP; STAR Trial Group. Upper-airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 9;370(2):139-49. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietzsch JB, Liu S, Garner AM, Kezirian EJ, Strollo PJ. Long-Term Cost-Effectiveness of Upper Airway Stimulation for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Model-Based Projection Based on the STAR Trial. Sleep. 2015 May 1;38(5):735-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012 Oct;22(10):1435-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liptak LA, Sall E, Kim S, Mosca E, Charkhandeh S, Remmers JE. Different Oral Appliance Designs Demonstrate Different Rates of Efficacy for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Review Article. Bioengineering, 2: 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Liptak, L. A. , Edward Sall and Shouresh Charkhandeh. 2025 “Most Custom Oral Appliances for Obstructive Sleep Apnea Do Not Meet the Definition of Custom” Preprints. [CrossRef]

- A.Trattner, L. A.Trattner, L. Hvam, C. Forza, Z.N.L. Herbert-Hansen. Product Complexity and Operational Performance: A Systematic Literature Review. CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology, 25 (2019), pp. 69-83.

- Sall, E.; Smith, K.; Desai, A.; Carollo, J.A.; Murphy, M.T.; Kim, S.; Liptak, L.A. Evaluating the Clinical Performance of a Novel, Precision Oral Appliance Therapy Medical Device Made Wholly from a Medical Grade Class VI Material for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Cureus 2023, 15, e50107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- <b>16. </b>E. Mosca, M. E. Mosca, M. Braem, and E. Collier. Treatment Of Obstructive Sleep Apnea With Mandibular Advancement Device In ‘Real-world’ Settings Across Six General Hospitals [abstract]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2025;211:A6940.

- Dao N, Cozean C, Chernyshev O, Kushida C, Greenburg J, Alexander JS. Retrospective Analysis of Real-World Data for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea with Slow Maxillary Expansion Using a Unique Expansion Dental Appliance (DNA). Pathophysiology. 2023 May 9;30(2):199-208. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P. , Ning X.-H., Lin H., Zhang N., Gao Y.-F., Ping F. Continuous positive airway pressure versus mandibular advancement device in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2020;72:5–11. [CrossRef]

- Mickelson, S.A. Oral Appliances for Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am. 2020;53:397–407. [CrossRef]

- Dieltjens, M. , Charkhandeh, S., Van den Bossche, K., Engelen, S., Van Loo, D., Verbraecken, J., Braem, M. and Vanderveken, O.M., 2023. Oral Appliance Therapy as First-line Treatment Option in Patients Diagnosed With Moderate to Severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea. In A18. BREAKING NEWS IN OSA: NEW APPROACHES AND NEW TRIALS (pp. A1050-A1050). American Thoracic Society.

- Punjabi NM, Patil S, Crainiceanu C, Aurora RN. Variability and Misclassification of Sleep Apnea Severity Based on Multi-Night Testing. Chest. 2020 Jul;158(1):365-373. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechat B, Naik G, Reynolds A, Aishah A, Scott H, Loffler KA, Vakulin A, Escourrou P, McEvoy RD, Adams RJ, Catcheside PG, Eckert DJ. Multinight Prevalence, Variability, and Diagnostic Misclassification of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 Mar 1;205(5):563-569. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azarbarzin A, Sands SA, Stone KL, Taranto-Montemurro L, Messineo L, Terrill PI, Ancoli-Israel S, Ensrud K, Purcell S, White DP, Redline S, Wellman A. The hypoxic burden of sleep apnoea predicts cardiovascular disease-related mortality: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study and the Sleep Heart Health Study. Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 7;40(14):1149-1157. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy624. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 7;40(14):1157. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz028. PMID: 30376054; PMCID: PMC6451769.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).