1. Introduction

Children, defined as individuals aged 0 to 18 years, require targeted research to investigate the pharmacological and toxicological aspects of medications, ensuring the development of safe, effective, and high-quality drugs [

1]. Although clinical trials involving pediatric populations are essential for the safe use of medications in this demographic, they often encounter various ethical challenges and concerns. Consequently, many medications administered in pediatric care are prescribed off-label—meaning they are used outside the authorized indications specified in the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)—resulting in inadequate documentation regarding dosing, efficacy, and safety [

2]. A single prescription may be classified as off-label for various reasons, the most common of which are summarized in

Table 1 [

3].

Off-label drug use is a pervasive practice in pediatric prescribing, particularly within hospital settings. Recent studies emphasize that young children, especially infants and toddlers, are the most frequent recipients of undocumented prescriptions [

3,

4]. In neonatal and pediatric hospital care, the prevalence of off-label drug use exhibits significant variability, ranging from 10% to 65%, depending on the clinical context. In outpatient pediatric settings, this range is slightly narrower, reported between 11% and 31% [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Among therapeutic categories, analgesics and antibiotics are most commonly prescribed off-label in hospitals [

3,

5,

6]. Frequently used off-label medications in these settings include morphine, salbutamol, heparin, and various cardiovascular agents [

5,

6,

7].

Assessing whether a treatment constitutes off-label use presents multifaceted challenges spanning clinical, ethical, and communication domains. Clinically, the absence of robust scientific evidence and an increased risk of adverse drug events (ADEs) are major concerns, as many off-label indications lack support from high-quality clinical trials. Despite regulatory efforts to incentivize pediatric drug research, off-label prescribing remains widespread due to the limited availability of pediatric-specific formulations and the paucity of age-appropriate clinical trials [

8]. The lack of standardized protocols further complicates monitoring for treatment efficacy and safety. Additionally, the absence of comprehensive registries for off-label use impedes large-scale data collection, restricting the ability to evaluate such treatments systematically.

The vulnerability of infants and children to off-label drug use is compounded by their immature hepatic and renal functions and their distinct pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles, which require careful dose adjustments. This underscores the urgency of generating more evidence on the safety and efficacy of off-label medications. Critically ill neonates and infants, among the most fragile pediatric populations, experience the highest levels of undocumented drug use, reinforcing the need for targeted research in this area [

9]. Existing studies suggest that ADEs associated with off-label use often arise from incorrect dosing or inappropriate routes of administration rather than the off-label indication itself [

10].

These risks are magnified in polypharmacy contexts, where the concurrent use of multiple medications increases the likelihood of drug-drug interactions, cumulative toxicities, and medication errors [

11]. Pediatric palliative care (PPC) exemplifies this complexity, as the need to manage multiple comorbidities frequently necessitates polypharmacy, further heightening these risks [

12,

13].

Notably, healthcare professionals exhibit differing perceptions of off-label use, particularly between clinical pharmacists and physicians. While both groups recognize the necessity of off-label prescribing in pediatric care, pharmacists often demonstrate a heightened awareness of the associated legal and ethical considerations. They advocate for rigorous documentation and monitoring practices compared to physicians, who tend to prioritize clinical efficacy and patient-centered outcomes [

14,

15]. These differing perspectives underscore the importance of enhanced interdisciplinary communication and collaboration to optimize the safety and effectiveness of off-label prescribing, particularly for vulnerable pediatric populations [

16].

This study aims to explore the perspectives of physicians and clinical pharmacists on off-label prescribing within PPC, focusing on whether their views diverge and identifying potential gaps in knowledge regarding pediatric treatments. Given that PPC is notably susceptible to off-label prescriptions and that many patients experience polypharmacy, this context provides a compelling framework for this research proposal.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A cross-sectional observational study was carried out between August and October 2021 in the PPC center of the University Hospital of Padova, Italy. Data were initially collected from medical records, followed by a separate analysis of off-label treatments by two groups: two physicians from the PPC center who were not the main prescriber and two clinical pharmacists from the Hospital Pharmacy Unit. Each group assessed the type of prescription (on-label or off-label) and its rationale, using their respective reference sources: pharmacists consulted the SmPC and guidelines from the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA), while physicians relied on the SmPC, Clinical Decision Support Software (CDSS), and international guidelines. Discrepancies within each group were resolved by a multidisciplinary team, and the final assessment was based on a common consensus.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

The study included patients with at least one access at the PPC center and with at least one prescribed drug treatment and an age of less than 23 years. Data collected included age, gender, primary diagnosis, number and type of medications, frequency and route of administration, and ability to self-administer. Drugs were categorized by Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification for further analysis.

2.3. Data Collection

Clinical data, such as medical characteristics, were obtained from medical records and pharmacological reviews of patients' therapies during the study period. For new prescriptions, further analysis was conducted. Physicians and pharmacists independently evaluated whether each treatment was on-label or off-label, based on the patient's condition and the drug's authorized indication. Guidelines issued by AIFA were also consulted, particularly those on early drug access, cross-referenced with dosage and SmPC recommendations [

17]. In particular the guidelines for early access to a drug and cross-checked with the patients' own dosage and with the sheet patient information leaflets. Considering the complexity of some pediatric pathologies, including rare diseases, it was necessary to identify signs and symptoms of the single pathology by obtaining information from what is present in the bibliography in the Italian register of rare diseases and orphan drugs. [

18] The medical approach to the analysis was different instead: the physicians traced the entire pathological picture of the individual patient to the pre-existing international guidelines, thus considering all the symptoms resulting from the primary diagnosis and the individual situation. It was thus defined whether a treatment was then appropriate to the individual disease situation. At the end of the evaluations, a consensus between pharmacists and clinicians allowed conflicting assessments to be resolved.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Normally distributed continuous data were reported as mean ± SD and compared using the two-sided Student’s t-test. Non-normally distributed continuous data were reported as the median and interquartile-range (IQR) and compared using the Mann–Whitney test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and were analyzed with the χ2 -test with Yates’s correction or Fisher’s exact test, whichever was most appropriate.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study adhered to Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines and European directives 2001/20/CE and ISO 14155, and in agreement with the local regulations. The final protocol and its amendments were reviewed and approved by the local Ethical Committee (CE) with the number 197n/AO/21. Written informed consent was obtained from a parent and/or legal guardian.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Included Patients

The study included a total of 169 patients, with a near-equal distribution of males (49%) and females (51%), with a median age of 12.5 years (interquartile range [IQR] 6-18). The age distribution revealed that 5.9% were infants (1 month to 2 years), 19.5% were preschool-aged children (3-5 years), 22.5% were school-aged children (6-11 years), and 38.5% were adolescents (12-18 years). Additionally, 13.6% of the population were adults (≥18 years). The mean duration of disease history among the participants was 10.4 years (±6.0), with a median of 11 years (IQR 2–18). The most common primary diagnosis categories included neurologic disorders (41.4%), musculoskeletal conditions (28.4%), and genetic–metabolic disorders (16.0%). Notably, 90.5% of patients had congenital or perinatal onset conditions. To better understand the complexity of each patient's therapeutic regimen, treatments and supplements were also considered. A total of 993 pharmacological treatments were analyzed, categorized as either chronic therapies or as-needed medications. On average, each patient was taking 5.9 medications, with 52.7% of patients engaged in polypharmacy (defined as the concurrent administration of five or more drugs per day), while 19.5% were identified with excessive polypharmacy (ten or more drugs per day). These patients were taking an average of 13.5 medications daily, with a Medication Regi-men Complexity Index (MRCI) score of 44.8 [

18,

19]. A substantial 44.4% of the participants faced a medication burden, which was characterized by polypharmacy plus at least two drug administrations per night. Additionally, only 22.5% of the patients were involved in self-administration of their medications. See

Table 2 for further details.

These findings underscore the complex medication regimens frequently encountered in pediatric populations, particularly those with chronic conditions, and highlight the need for careful management to mitigate potential risks associated with polypharmacy, including adverse drug reactions and drug-drug interactions.

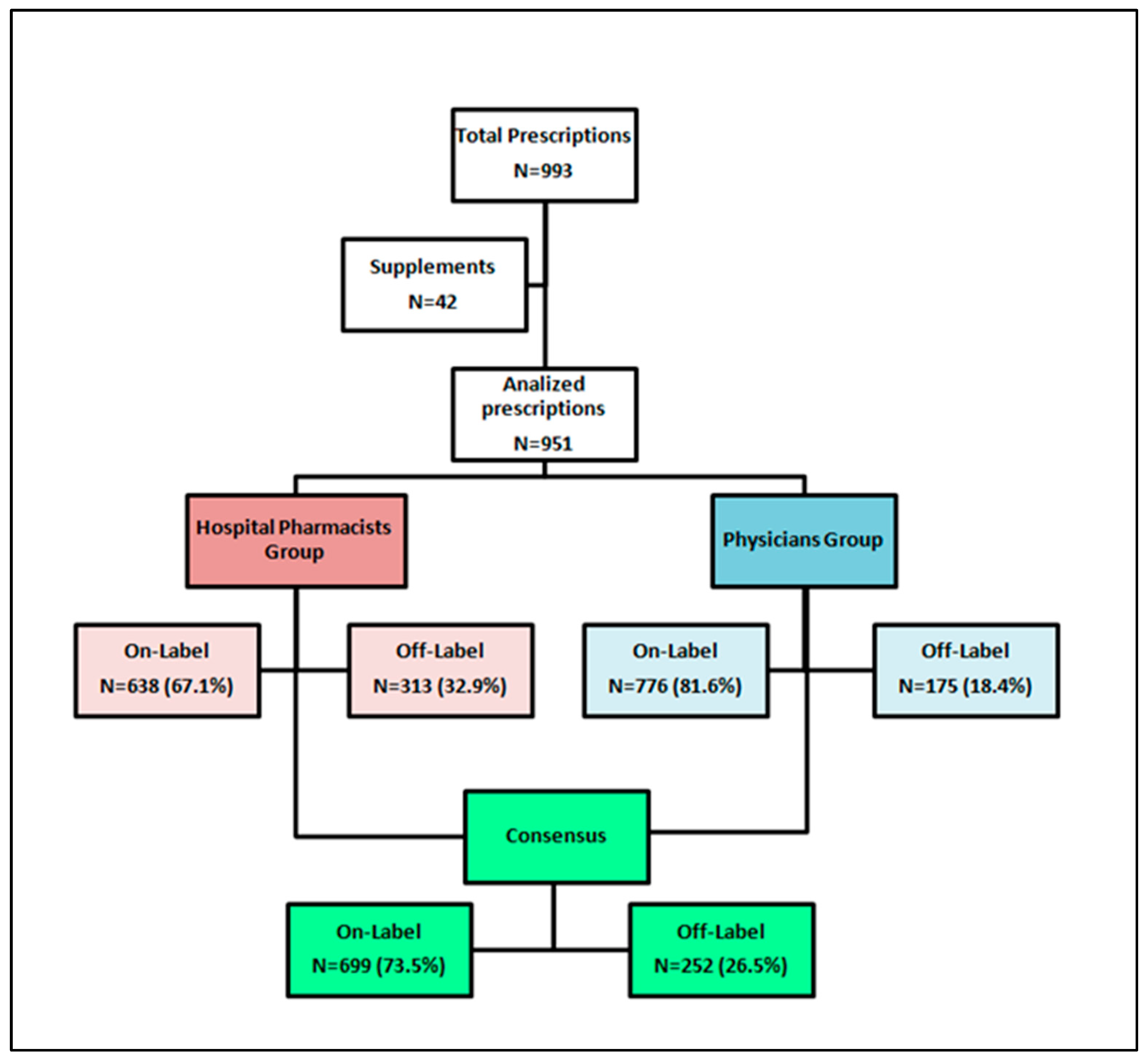

3.2. Off-Label Analysis

When focusing on drug prescriptions alone, a comparison of off-label uses revealed that out of 951 total drug treatments, clinicians identified 175 (18.4%) instances of off-label use, while pharmacists documented 313 off-label uses, representing 32.9% of all prescriptions reviewed (p<0.05). For a detailed overview of the review process, please refer to

Figure 1.

For each identified off-label use, a detailed analysis was conducted to categorize the specific type of utilization. The analysis evaluated the incidence rates of off-label use across various dimensions, including clinical indication, patient age, route of administration, dosage regimen, and other relevant factors. Differences were notable in classifications such as use for different indications (25.9% identified by pharmacists vs. 57.1% identified by clinicians, p < 0.05), route of administration (9.9% vs. 4.6%, p = 0.04), and dosage (44.1% vs. 18.3%, p < 0.05). However, no significant differences were observed for age-related off-label uses (p = 0.27). Moreover, physicians more frequently reported "other" non-recommended uses (17.1% vs. 0.9%, p < 0.05), these include unauthorized manipulations. These findings highlight the varying perspectives and rigor applied by the two groups. Detailed findings are presented in

Table 3.

Among the drugs most frequently classified as off-label in the physicians' group were azithromycin, salbutamol, and cannabinoids. In contrast, the pharmacists' group identified cholecalciferol, lansoprazole, antibiotics, and macrogol as the most prevalent off-label medications.

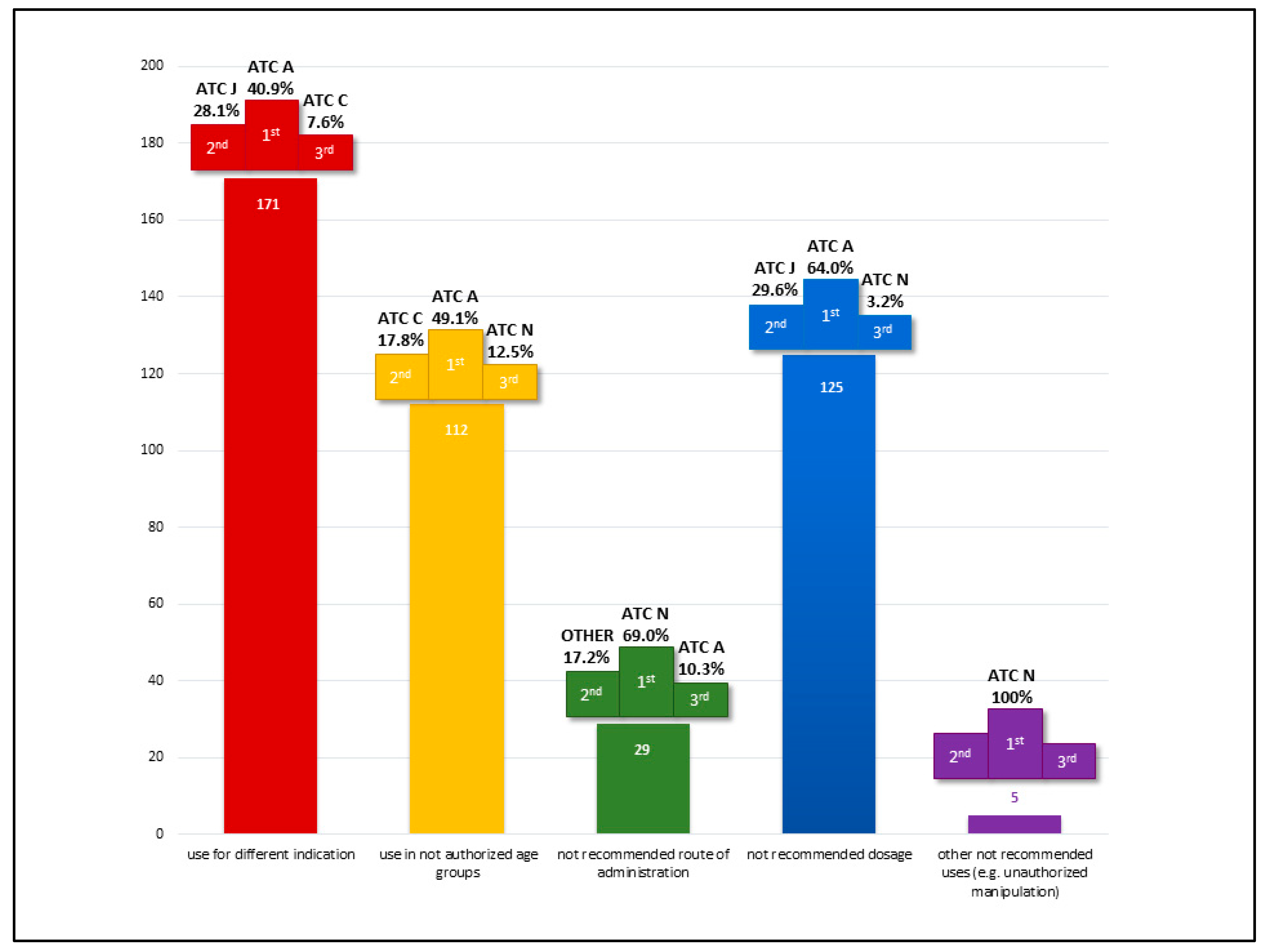

In the consensus process conducted after evaluations by clinicians and pharmacists, 252 prescriptions (26.5%) were identified as off-label. The majority of these were categorized as off-label due to indication, representing 171 cases (67.9%). Additionally, 49.6% of the off-label uses were related to dosage deviations, and 44.4% were associated with age discrepancies. Notably, 132 prescriptions (52.4%) were off-label for multiple reasons.

The distribution of off-label uses by the first ATC level is detailed in

Figure 2, highlighting the top three most represented therapeutic classes across use categories. Class A (Alimentary Tract and Metabolism) emerged as the most represented category overall, as well as for off-label use by indication, age, and dosage. This predominance is primarily attributable to the chronic use of proton pump inhibitors and macrogol.

Class J (Anti-infective Drugs for Systemic Use) accounted for approximately one-fifth of the total off-label prescriptions, driven predominantly by their application in long-term prophylaxis among frail patient populations.

Regarding off-label uses by route of administration, Class N (Nervous System) was the most prominent. This reflects the frequent administration of antiepileptic drugs via enteral tubes, a common practice in PPC patients.

4. Discussion

Our analysis highlights the percentage (26.5%) of off-label prescriptions in this PPC cohort and the difference between physicians and pharmacists regarding its perception. This divergence underscores the complexity inherent in off-label prescribing practices and the need for a collaborative framework [

16].

This result can highlight both the accuracy and strict adherence to regulation and guidelines from the pharmacist on one side and the underestimation from the clinical physicians probably due to the fact that the common and routine use of these drugs in such subspecialized context, despite their original indication, can lead them to be used to their prescription and then underestimating their off-label rate.

Finding common ground between the structured regulatory approach of hospital and clinical pharmacists and the patient-centered clinical perspective of physicians is critical for guaranteeing medication treatment effectiveness and safety. The different recognition between clinical physicians and pharmacist of off-label drugs for some specific items as duration of treatment, route of administration or even the dosage reveal significant variations in their approaches. Physicians have a thorough awareness of their patients' clinical problems and unique treatment needs. They are continuing monitoring symptoms and clinical patient status with regular follow up after starting a drug in order to detect the effectiveness of the treatment and also its potential adverse effects, proposing sometimes off label drugs as the only possibility to get a treatment which is possibly effective. This probably make not recognizing as valuable some off-label indications of specific drugs as the prolonged duration issues, whereas pharmacists are more focused on pharmacological characteristics, drug interactions, and adherence to current regulations. The identification of common off-label medications, such as azithromycin and macrogol, highlights the need for standardized protocols and communication between healthcare providers, scientific societies and pharmacists. Establishing regular interdisciplinary meetings can facilitate ongoing dialogue about off-label drug use, ensuring that all parties are aligned on treatment goals and strategies. This proactive approach is particularly vital in pediatric populations, where the risks associated with off-label prescribing can be compounded by factors such as polypharmacy and the unique pharmacokinetic profiles of children. In PPC, the issue of polypharmacy is particularly pressing, as more than 50% of children are experiencing polypharmacy, defined as the concurrent use of five or more medications [

12,

23]. This situation can lead to a heightened risk of adverse drug reactions, therapeutic duplication, and difficulties in medication adherence, exacerbating the challenges of managing such vulnerable populations [

24,

26]. Clinical physicians before prescribing off label drugs need to evaluate the context of each patient's clinical picture trying to find out possible pharmacological solutions and often to adapt the use from other context, but sometimes this is the only option available to ensure that the patient is provided with a therapeutic resource. In this sense, it is also necessary to work on improving access to known and reliable off-label uses to compensate for the long regulatory timeframe and families from covering the costs of these drugs as they cannot be included always in their standard prescriptions regimen covered but the Italian National Health System [

25].

Finally, in this sensitive process a proper communication with patients and families about the risks and benefits associated with off-label use is mandatory. This complementary relationship should be implemented in clinical practice, fostering a comprehensive understanding of treatment options, facilitating informed and safe therapeutic decisions [

14].

As previously discussed, off label drugs in pediatrics rise many challenges for both pharmacists and pediatricians for the near future. A collaboration between clinicians and pharmacists has been shown to significantly reduce the risk of medication errors related to the use of off label drugs but this is not systematic and diffused in many clinical contexts [

27]. The first role of pharmacists is to provide critical insights regarding appropriate doses, routes of administration, and potential drug interactions and monitoring side effects [

20]. But to date there are few registries for pediatric off label drug or ongoing clinical trial dedicated to monitoring the use of these drugs and potentially giving more insights on the use, dosage route of administration, safety and effectiveness. Another important resource is the preparation of customized galenic formulations to meet the specific needs of the pediatric patient and provide correct information and training in order to facilitate drug delivery and solving some of these off-label indications [

28]. The pharmacist can also play an important role in training healthcare personnel and informing patients and their families on the correct use of medicines [

28]. Continuing education and updates on about regulations are essential for all healthcare providers involved in the use of off-label drugs in pediatrics. This integrated approach not only enhances patient safety but also promotes the efficient management of hospital resources. By optimizing the use of available medications and reducing waste, healthcare systems can better navigate the increasing pressures they face [

21,

22].

Despite the valuable insights gained from our analysis, this study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. A larger and more diverse population, maybe obtained from a national multicenter study, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complexities surrounding off-label drug use. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data from physicians and pharmacists may introduce bias, as responses could be influenced by personal experiences or perceptions. Lastly, the study did not account for long-term outcomes associated with off-label use, which warrants further investigation.

To generate scientific evidence and improve patient safety related to the use of off label drugs in pediatrics it should be implemented the use of registries and databases promote the participation in pediatric clinical trials.

Looking ahead, further clinical research is essential to establish clear guidelines for off-label drug use in PPC, ideally through specific funding and the simplification of regulatory procedures. The creation of national and international registries to collect data on off-label drug use (especially for rare conditions) can provide valuable information for risk-benefit assessment and clinical guideline development as well as collaboration between healthcare institutions, universities and pharmaceutical industries.

5. Conclusions

Although a clear and flexible regulatory framework is already present in the Italian law, there is still a clear need for regulatory authorities to implement streamlined evaluation mechanisms that facilitate off-label drug use in emergency situations or when there is an unmet clinical need [

29]. This could involve expedited procedures for temporary approvals based on preliminary yet promising evidence. A more flexible regulatory framework that balances the clinical necessity for off-label use with the imperative of patient safety could significantly enhance access to potentially life-saving treatments. Moreover, a collaborative approach involving both physicians and pharmacists is essential for accurately identifying scenarios where off-label use is justified. This necessitates a thorough evaluation of the available evidence, expected benefits, and associated risks.

In conclusion, fostering increased collaboration between healthcare providers, alongside the adoption of adaptable regulatory measures, will ensure the safe and effective use of off-label medications, ultimately benefiting pediatric patients. This integration might range from investigating the effects of regular medication reviews, which could reveal significant insights for optimizing drug therapy, to supporting and delivering effective patient education on drug adherence to empower patients and their caregivers, and ultimately improving care for vulnerable patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M. and A.Z.; methodology, D.M., A.Z. and F.Ba.; validation, L.C. and L.P.; formal analysis, D.M., A.Z. and F.Ba.; investigation, D.M., L.P., A.Z. and F.Ba.; resources, F.V. and F.Be.; data curation, D.M., A.Z. and F.Ba.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M., A.Z., L.P. and F.Ba.; writing—review and editing, F.Be, F.V.; visualization, D.M and A.Z.; supervision, F.V., F.Be. and L.C.; project administration, D.M. and A.Z.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The final protocol and its amendments were reviewed and approved by the local Ethical Committee (EC) of the Province of Padova with the number 197n/AO/21.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all parents or legal guardians of the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PPC |

Pediatric Palliative Care |

| ADE |

Adverse Drug Event |

| SmPC |

Summary of Product Characteristics |

| AIFA |

Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco – Italian Medicines Agency |

| CDSS |

Clinical Decision Support Software |

| ATC |

Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical |

| GCP |

Good Clinical Practice |

| EC |

Ethical Committee |

| |

|

References

- Laughon MM, Benjamin DK Jr, Capparelli EV, et al. Innovative clinical trial design for pediatric therapeutics. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2011, 4, 643–652. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuzzolin L, Atzei A, Fanos V. Off-label and unlicensed prescribing for newborns and children in different settings: a review of the literature and a consideration about drug safety. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2006, 5, 703–718. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobe, AH. Off-Label Drugs in Neonatology: Analyses Using Large Data Bases. J Pediatr. 2019, 208, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yackey K, Stukus K, Cohen D, Kline D, Zhao S, Stanley R. Off-label Medication Prescribing Patterns in Pediatrics: An Update. Hosp Pediatr. 2019,9, 186-193. [CrossRef]

- Feka A, Di Paolo ER, Pauchard JY, Mariguesa A, Gehri M, Sadeghipour F. Off-label use of psychotropic drugs in a Swiss paediatric service: similar results from two different cohort studies. Swiss Med Wkly. 2022, 152, w30124. [CrossRef]

- 't Jong GW, Vulto AG, de Hoog M, Schimmel KJ, Tibboel D, van den Anker JN. A survey of the use of off-label and unlicensed drugs in a Dutch children's hospital. Pediatrics 2001, 108, 1089–1093. [CrossRef]

- Di Salvo M, Santi Laurini G, Motola D, et al. PAttern of drug use in PEdiatrics: An observational study in Italian hOSpitals (the PAPEOS study). Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2024, 90, 1050–1057. [CrossRef]

- Gidey MT, Gebretsadkan YG, Tsadik AG, Welie AG, Assefa BT. Off-label and unlicensed drug use in Ayder comprehensive specialized hospital neonatal intensive care unit. Ital J Pediatr. 2020, 46, 41. [CrossRef]

- Akıcı N, Kırmızı Nİ, Aydın V, Bayar B, Aksoy M, Akıcı A. Off-label drug use in pediatric patients: a comparative analysis with nationwide routine prescription data. Turk J Pediatr. 2020, 62, 949–961. [CrossRef]

- Park B, Lee H, Choi H, Lee J. Age-related off-label drug prescribing in pediatric patients in South Korea and consistency of labeling compared to the United States, Europe, and Japan. Clin Transl Sci. 2024, 17, e13869. [CrossRef]

- Bakaki PM, Horace A, Dawson N, et al. Defining pediatric polypharmacy: A scoping review. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0208047. [CrossRef]

- Zanin A, Baratiri F, Roverato B, et al. Polypharmacy in Children with Medical Complexity: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Pediatric Palliative Care Center. Children (Basel). 2024, 11, 821. [CrossRef]

- Tamir S, Kurnik D, Weyl Ben-Arush M, Postovsky S. Polypharmacy among pediatric cancer patients dying in the hospital. Isr Med Assoc J. 2021, 23, 426–431.

- Alyami D, Alyami AA, Alhossan A, Salah M. Awareness and Views of Pharmacists and Physicians Toward Prescribing of Drugs for Off-Label Use in the Pediatric Population in Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2022, 14, e23082. [CrossRef]

- Day, RO. Ongoing challenges of off-label prescribing. Aust Prescr. 2023, 46, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain SA, Abbas AN, Alhadad HA, Al-Jumaili AA, Abdulrahman ZS. Physician-pharmacist agreement about off-label use of medications in private clinical settings in Baghdad, Iraq. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2017, 15, 979. [CrossRef]

- Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA). Early access and off-label use. Available online: https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/accesso-precoce-uso-off-label (accessed on 30/12/2024).

- Orphanet. Knowledge on rare diseases and orphan drugs. Available online: https://www.orpha.net/en/disease (accessed on 23/12/2024).

- Hirsch JD, Metz KR, Hosokawa PW, Libby AM. Validation of a patient-level medication regimen complexity index as a possible tool to identify patients for medication therapy management intervention. Pharmacotherapy. 2014, 34, 826–835. [CrossRef]

- Balan S, Hassali MA, Mak VS. Awareness, knowledge and views of off-label prescribing in children: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015, 80, 1269–1280. [CrossRef]

- Almintakh LS, Al Dossary MF, Altesha AM, et al. Awareness, Practice, and Views of Pediatricians, General Physicians, and Pharmacists about Prescribing Off-label Medication in Pediatric Patients in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Meng M, Hu J, Liu X, et al. Barriers and facilitators to guideline for the management of pediatric off-label use of drugs in China: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024, 24, 435. [CrossRef]

- Nelson KE, Feinstein JA, Gerhardt CA, et al. Emerging Methodologies in Pediatric Palliative Care Research: Six Case Studies. Children (Basel). 2018, 5, 32. [CrossRef]

- García-López I, Cuervas-Mons Vendrell M, Martín Romero I, de Noriega I, Benedí González J, Martino-Alba R. Off-Label and Unlicensed Drugs in Pediatric Palliative Care: A Prospective Observational Study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020, 60, 923–932. [CrossRef]

- De Zen L, Marchetti F, Barbi E, Benini F. Off-label drugs use in pediatric palliative care. Ital J Pediatr. 2018, 44, 144. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baratiri F, Zanella C, Roverato B, et al. The role and perception of the caregiver in a specialized pediatric palliative care center in medicine preparation and administration: a survey study. Ital J Pediatr. 2024, 50, 238. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravi P, Pfaff K, Ralph J, Cruz E, Bellaire M, Fontanin G. Nurse-pharmacist collaborations for promoting medication safety among community-dwelling adults: A scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2022, 4:100079. Published 2022 Apr 18. [CrossRef]

- Mengato D, Zanin A, Russello S, et al. Taking care of caregivers: enhancing proper medication management for palliative care children with polypharmacy. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA). Available online: https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/legge-648-96 (accessed on 31/12/2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).