Submitted:

20 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

- What specific experiential learning and mentorship approaches most effectively develop interdisciplinary STEM competencies among HR professionals?

- How do organizational context factors moderate the effectiveness of these development approaches?

- What barriers and enablers influence the implementation of interdisciplinary development initiatives for HR professionals?

Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

An Integrated Framework for Interdisciplinary Competency Development

- HR competency theory (Ulrich et al., 2021) provides the professional context and functional domains where technical competencies must be applied.

- Interdisciplinary learning theory (Repko & Szostak, 2020) offers insights into the cognitive and social processes through which professionals integrate knowledge across disciplinary boundaries.

- Sustainable education principles (Sterling, 2021) provide the framework for ensuring development approaches create lasting capabilities while addressing broader sustainability concerns.

Conceptualizing STEM Fluency for HR Professionals

- Cognitive dimension: Understanding of foundational STEM concepts, technological trends, and scientific methods relevant to organizational contexts

- Functional dimension: Ability to apply STEM knowledge to HR practices including talent acquisition, development, and organizational design

- Integrative dimension: Capacity to synthesize human and technical considerations in strategic decision-making

Sustainable Education in Professional Development

- Ecological sustainability: Development approaches that minimize environmental impact while creating awareness of ecological considerations in HR practice

- Temporal sustainability: Learning systems that build adaptable competencies relevant across changing technological contexts

- Social sustainability: Development practices that promote inclusive participation across diverse backgrounds and experiences

- Ecological sustainability: Assessment of development approaches' environmental footprint and integration of ecological considerations in learning content

- Temporal sustainability: Evaluation of competency adaptability across changing technological contexts through scenario-based assessment

- Social sustainability: Measurement of demographic participation patterns and analysis of structural barriers to inclusive development

Experiential Learning and Mentorship

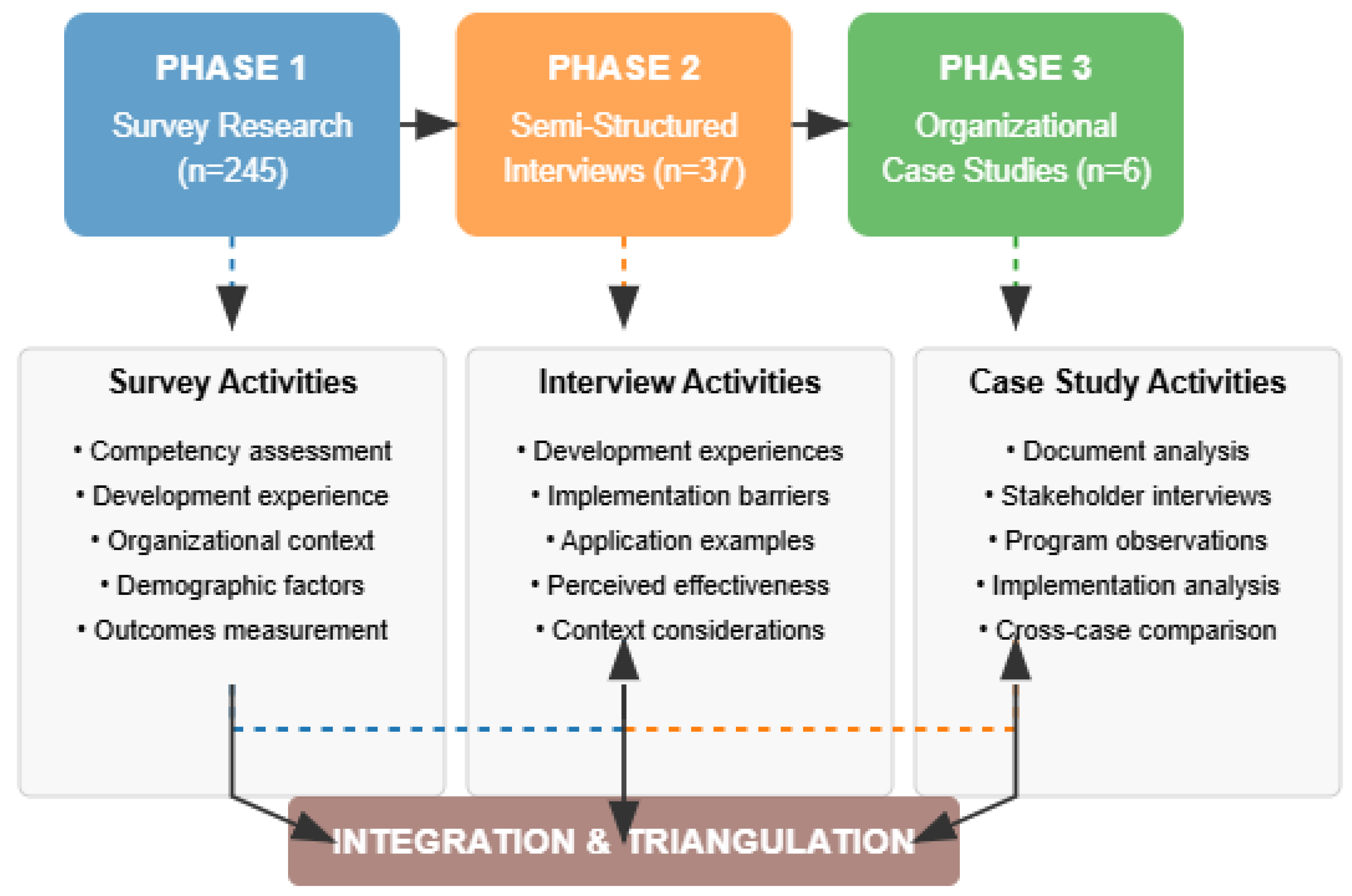

Method

Research Design

Researcher Positionality

Phase 1: Survey Research

Participants and Sampling

Measures

- STEM Fluency. STEM fluency was measured using the 24-item assessment instrument developed in pilot research (see Appendix A, items 12-35). Items assessed three dimensions (cognitive, functional, and integrative) across eight STEM domains relevant to organizational contexts. The scale demonstrated strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.87). Confirmatory factor analysis supported the three-dimensional structure (CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.06), with all items loading on their intended factors above 0.60.

- Development Approaches. Participants reported their experiences with seven different development approaches: cross-functional rotations, action learning projects, technology labs/simulations, bidirectional mentorship, communities of practice, external expert networks, and digital learning platforms. For each approach, participants rated both exposure (duration and intensity) and perceived effectiveness (see Appendix A, items 36a-g).

- Organizational Context Factors. Multiple contextual factors were measured including organization size, industry, learning culture (using Yang et al.’s (2022) Learning Organization Questionnaire, α = 0.91), resource availability, and technical leadership engagement (see Appendix A, items 8-11).

- Demographic and Control Variables. The researchers collected data on participants’ gender, age, educational background, prior STEM experience, organizational tenure, and geographic location to analyze potential demographic patterns in development experiences and outcomes (see Appendix A, items 1-7).

Procedure

Phase 2: Semi-Structured Interviews

Participant Selection

Interview Protocol and Procedure

Phase 3: Organizational Case Studies

Case Selection

- Large pharmaceutical company (8,000+ employees) – established program

- Mid-sized technology firm (800 employees) – established program

- Small biotechnology startup (45 employees) – emerging program

- Manufacturing company (1,200 employees) – established program

- Regional healthcare system (3,500 employees) – emerging program

- Professional services firm (400 employees) – emerging program

Data Collection

- Document analysis: Program materials, competency frameworks, evaluation data, internal communications (10-25 documents per organization)

- Stakeholder interviews: 6-10 interviews per organization with HR professionals, technical leaders, organizational leadership, and program participants (48 interviews total)

- Observational data: Where possible, researchers observed development activities including mentorship sessions, learning events, and cross-functional meetings (conducted in 4 of 6 organizations)

Case Analysis Approach

- Within-case analysis: Developing comprehensive descriptions of each organization’s approach, context, and outcomes

- Cross-case pattern identification: Comparing and contrasting findings across cases to identify patterns, contextual influences, and conditional relationships

- Theory elaboration: Refining theoretical understanding based on case patterns

Data Analysis

- Methodological triangulation: Comparing findings across methods (surveys, interviews, case studies)

- Data source triangulation: Comparing perspectives across stakeholder groups

- Investigator triangulation: Involving multiple researchers in analysis

- Member checking: Sharing preliminary interpretations with participants for validation

Results

Survey Results: Effectiveness of Development Approaches

Demographic Patterns in Development Experiences and Outcomes

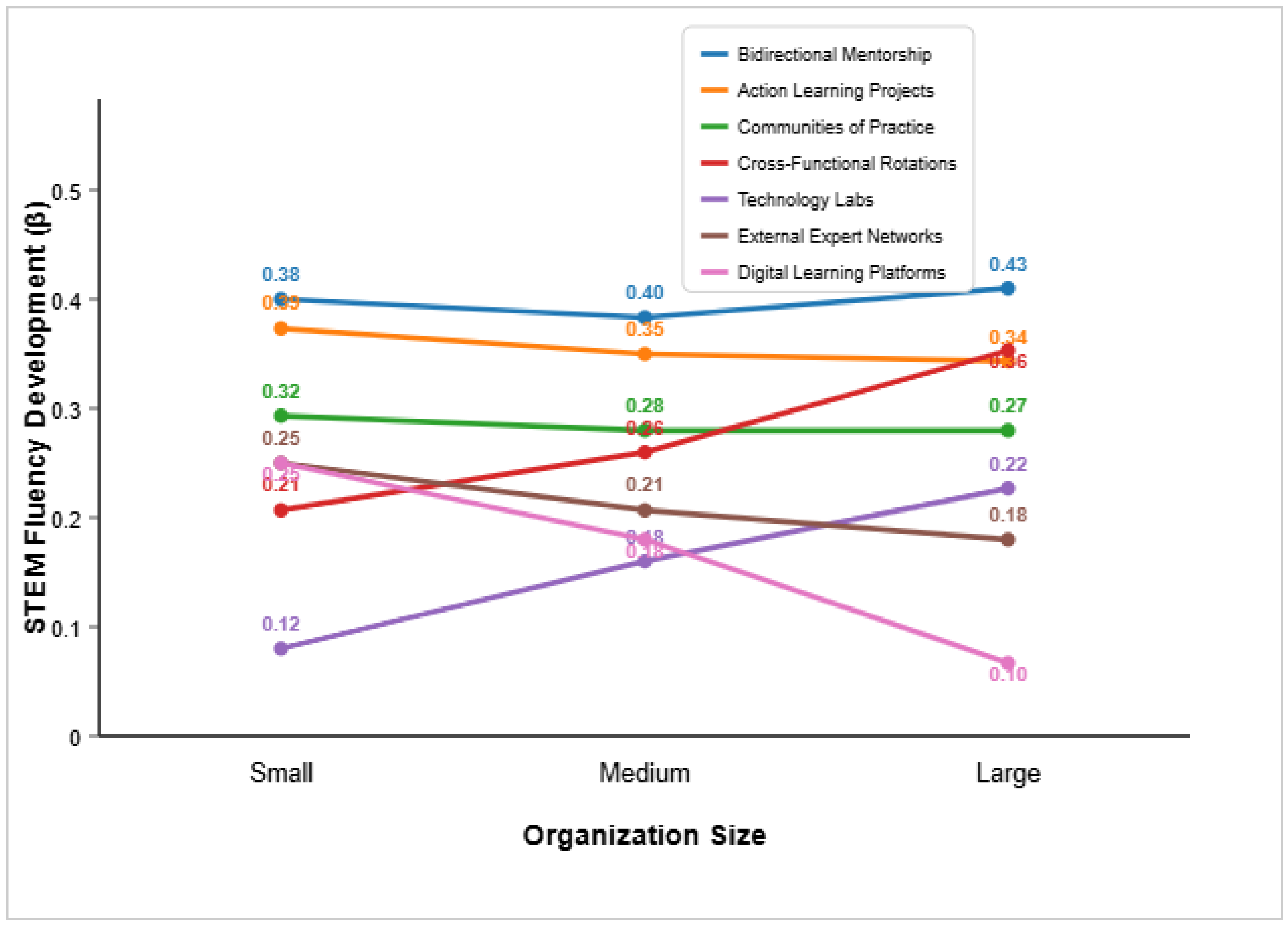

Organizational Context as Moderator

Key Implementation Mechanisms

- 1.

- Contextual knowledge acquisition: Direct exposure to technical contexts created tacit understanding of how STEM knowledge is applied in practice.

"You can't learn the language just from reading about it. Being embedded in the R&D team showed me how scientists actually think and communicate, which completely changed how I approach talent development for those teams."(Participant 14, Pharmaceutical HR Business Partner)

- 2.

- Identity boundary-spanning: Effective approaches helped HR professionals expand their professional identity without threatening core HR identity.

"The mentorship wasn't about turning me into a pseudo-engineer. It was about helping me become a better HR professional who can understand and engage with engineering contexts."(Participant 7, Manufacturing HR Director)

- 3.

- Psychological safety: Successful implementation created safe spaces for exploring unfamiliar concepts and acknowledging knowledge gaps.

"In our action learning project, everyone recognized we were learning together. That safety to ask 'basic' questions was critical—I wouldn't have engaged otherwise."(Participant 23, Technology HR Specialist)

- 4.

- Practical application scaffolding: Immediate application opportunities with appropriate support reinforced learning.

"The community of practice gave me concepts on Tuesday that I could apply in my talent planning meeting on Wednesday, with experienced colleagues to help me translate between worlds."(Participant 19, Healthcare HR Manager)

Implementation Barriers

- 1.

- Resource constraints: Limited time, budget, and staff availability constrained implementation, particularly in smaller organizations.

"We know cross-functional rotation would be valuable, but we simply don't have the HR headcount to release someone for even a week."(Participant 29, Startup HR Lead)

- 2.

- Disciplinary identity concerns: Some HR professionals expressed concerns about diluting HR expertise or professional identity.

"There's pushback from HR colleagues who worry we're trying to turn everyone into tech people rather than strengthening our core HR expertise."(Participant 11, Professional Services HR Director)

- 3.

- Measurement challenges: Organizations struggled to measure development outcomes, particularly for integrative competencies.

"We know something valuable is happening, but our metrics don't capture it well, which makes it hard to justify continued investment."(Participant 34, Technology L&D Manager)

- 4.

- Access inequities: Development opportunities were often unevenly distributed, with certain groups having limited access.

"Our remote HR team members have much less access to these informal learning opportunities with technical teams, creating a significant gap in development."(Participant 8, Pharmaceutical HR Business Partner)

Case Study Insights: Contextual Implementation

Small Organization Context (Biotechnology Startup, 45 Employees)

- Weekly "Technical Tuesday" lunch sessions where technical staff explained current projects to HR team members

- HR participation in technical team stand-up meetings

- Shared Slack channels for ongoing informal knowledge exchange

- Strategic use of external resources including professional associations and free online learning

Large Organization Context (Pharmaceutical Company, 8,000+ employees)

- Formal 2-week technical immersions for HR business partners

- Cross-functional action learning projects addressing specific business challenges

- Dedicated HR Innovation Lab for experimenting with emerging technologies

- Formal mentorship program pairing HR professionals with technical specialists

Comparison of Effectiveness Across Contexts

- Leadership commitment from both HR and technical domains

- Integration with existing work processes rather than standalone initiatives

- Clear connection to organizational priorities

- Structured reflection opportunities to process learning experiences

- Recognition systems that value interdisciplinary competency development

Unexpected Findings

- Bidirectional knowledge flow: The most effective mentorship relationships involved technical specialists gaining valuable insights from HR professionals about people management, career development, and organizational dynamics—not just HR professionals learning technical concepts. This mutual learning created more sustainable relationships and greater commitment from technical specialists.

- Epistemological tensions as learning catalysts: Rather than being purely obstacles, the epistemological differences between HR and STEM approaches sometimes created productive tension that, when properly facilitated, accelerated learning through cognitive dissonance resolution.

- The role of crisis events: Several organizations reported that technological crises (e.g., failed system implementations, technical talent exoduses) created catalytic moments that accelerated interdisciplinary development by demonstrating the clear need for integration.

- Differential effectiveness for diverse populations: Development approaches showed differential effectiveness across demographic groups, with underrepresented minorities in technical fields often reporting greater benefits from structured approaches with clear inclusion mechanisms compared to more informal approaches.

Discussion

Theoretical Implications

Practical Implications

- Prioritize bidirectional learning: Create structures that recognize and value the unique contributions of both HR and technical perspectives, rather than positioning HR as merely "learning from" technical specialists.

- Address psychological safety: Explicitly acknowledge and mitigate anxiety about technical concepts through structured support, normalized learning curves, and permission to ask fundamental questions.

- Connect to practical application: Ensure learning is immediately applicable to real work challenges rather than theoretical or disconnected from daily responsibilities.

- Attend to identity concerns: Recognize and address concerns about professional identity dilution by framing interdisciplinary development as enhancing rather than replacing HR expertise.

- Create equitable access: Proactively identify and address structural barriers that limit participation, particularly for remote workers, underrepresented groups, and those with non-traditional backgrounds.

- Creating structured virtual shadowing opportunities

- Establishing digital communities of practice with synchronous and asynchronous components

- Designing hybrid learning experiences that intentionally include remote participants

- Developing specific metrics to track participation equity across work arrangements

Ethical Implications and Sustainability Connections

- Algorithmic decision-making (temporal sustainability): As HR professionals develop greater understanding of data science and AI, they must also develop ethical frameworks for evaluating when and how algorithmic approaches should be applied to human capital decisions. This ensures that technological implementations serve long-term human needs rather than creating short-term efficiencies at the expense of sustainable outcomes.

- Privacy and data ethics (social sustainability): Increased technical capability creates greater responsibility for ensuring appropriate data governance in HR processes, particularly given HR's access to sensitive personal information. Equitable and transparent data practices are essential for socially sustainable HR technology implementation.

- Digital divides (social sustainability): Technical competency development may exacerbate existing privilege patterns if not designed with equity in mind, potentially creating new hierarchies within the HR profession. Development approaches must proactively address access barriers to ensure social sustainability.

- Humanistic HR values (ecological sustainability): Organizations must ensure that increased technical competency complements rather than displaces HR's traditional commitment to human dignity, development, and wellbeing. This broader conception of sustainability recognizes that human systems exist within ecological systems, requiring balanced approaches to technological implementation.

Limitations and Future Research

Conclusions

Appendix A: STEM Fluency Assessment and Development Survey

- 1.

-

Gender:□ Female□ Male□ Non-binary/third gender□ Prefer to self-describe: _______________□ Prefer not to say

- 2.

-

Age range:□ 21-29□ 30-39□ 40-49□ 50-59□ 60+

- 3.

-

Years of experience in HR:□ 1-5 years□ 6-10 years□ 11-15 years□ 15+ years

- 4.

-

Current HR role (select best match):□ HR Business Partner□ Talent Acquisition Specialist□ Learning & Development Professional□ Compensation & Benefits Specialist□ Organizational Development Consultant□ HR Director/Executive□ HR Generalist□ Other: _______________

- 5.

-

Educational background (highest degree):□ High school diploma□ Associate's degree□ Bachelor's degree□ Master's degree□ Doctoral degree

- 6.

- Field of study for highest degree: _______________

- 7.

-

Prior STEM experience (select all that apply):□ Formal education in STEM field□ Previous work experience in STEM role□ STEM-related certifications□ Self-directed learning in STEM topics□ None

- 8.

-

Organization size (employees):□ <100□ 100-499□ 500-999□ 1,000-4,999□ 5,000+

- 9.

-

Industry sector:□ Technology□ Healthcare/Pharmaceuticals□ Manufacturing□ Financial Services□ Professional Services□ Retail/Consumer Goods□ Energy/Utilities□ Education□ Government/Public Sector□ Other: _______________

- 10.

-

How would you characterize your organization's technological intensity?□ Very high (technology is core to business strategy and operations)□ High (significant technology integration across functions)□ Moderate (standard technology adoption for industry)□ Low (minimal technology integration beyond basics)

- 11.

- Learning Culture Assessment

- 12.

-

Understanding of foundational data science concepts (e.g., statistical analysis, data visualization)1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 13.

-

Knowledge of artificial intelligence and machine learning fundamentals1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 14.

-

Understanding of software development processes and methodologies1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 15.

-

Knowledge of cybersecurity principles and their workplace implications1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 16.

-

Understanding of digital transformation concepts and technologies1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 17.

-

Knowledge of scientific research methods and evidence evaluation1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 18.

-

Understanding of human-computer interaction principles1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 19.

-

Knowledge of emerging technologies relevant to your industry1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 20.

-

Ability to evaluate technical skills during recruitment processes1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 21.

-

Skill in designing learning pathways for technical talent1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 22.

-

Ability to develop competency models for technical roles1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 23.

-

Skill in creating compensation structures appropriate for technical roles1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 24.

-

Ability to facilitate knowledge sharing between technical teams1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 25.

-

Skill in adapting HR processes to accommodate technical work requirements1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 26.

-

Ability to anticipate workforce implications of technological change1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 27.

-

Skill in measuring performance in technical roles1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 28.

-

Ability to translate technical concepts into human capital implications1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 29.

-

Skill in facilitating collaboration between technical and non-technical teams1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 30.

-

Ability to contribute HR perspective to technology implementation decisions1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 31.

-

Skill in addressing ethical implications of technologies in HR practices1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 32.

-

Ability to integrate technological and human considerations in strategic planning1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 33.

-

Skill in developing inclusive practices for technical talent from diverse backgrounds1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 34.

-

Ability to advocate for human needs in technology-driven changes1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 35.

-

Skill in balancing innovation and wellbeing in technical work environments1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □

- 36.

- Please indicate your experience with the following development approaches:

- 37.

-

What barriers have you experienced in developing STEM competencies? (Select all that apply)□ Limited time available□ Insufficient organizational resources□ Lack of access to technical specialists□ Limited learning opportunities□ Concerns about diluting HR expertise□ Difficulty measuring development outcomes□ Lack of support from leadership□ Technological intimidation or anxiety□ Unclear development pathways□ Other: _______________

- 38.

-

What has most enabled your development of STEM competencies? (Select up to three)□ Supportive organizational culture□ Mentorship relationships□ Clear development pathways□ Resources and time allocation□ Personal motivation and interest□ Visible application opportunities□ Leadership support□ Inclusion in technical projects□ Psychological safety for learning□ Other: _______________

- 39.

-

How have you applied interdisciplinary STEM competencies in your HR role? (Select all that apply)□ Improved talent acquisition for technical roles□ Enhanced development programs for technical talent□ Better collaboration with technical departments□ More effective organizational design for technical teams□ Improved input on technology implementation decisions□ Enhanced diversity and inclusion in technical roles□ More strategic workforce planning for technological change□ Better performance management for technical roles□ Other: _______________

- 40.

-

What business outcomes have resulted from your interdisciplinary competencies? (Select all that apply)□ Improved technical talent retention□ Reduced time-to-hire for technical roles□ Enhanced technical talent performance□ Better alignment between HR and technical departments□ More successful technology implementations□ Improved diversity in technical teams□ Cost savings in technical talent management□ Enhanced innovation in HR practices□ Other: _______________

Appendix B: Semi-Structured Interview Protocol

- Introduction of researcher and explanation of the study purpose

- Review of confidentiality, recording procedures, and informed consent

- Confirmation of interview duration (45-60 minutes)

- Any questions before beginning?

- Could you briefly describe your current role and responsibilities?

- What has been your career path in HR, and how has your role evolved in relation to technical functions?

- What educational or professional experiences shaped your understanding of STEM fields prior to your current role?

- How would you describe your current level of comfort and competence in working with technical concepts and STEM professionals?

- What specific development experiences have been most valuable in building your understanding of STEM fields? Could you describe one particularly impactful experience in detail?

- [If applicable based on survey] You indicated experience with [specific development approach]. Could you tell me more about how that experience was structured and what made it effective or ineffective?

- How has your organization supported your development of interdisciplinary competencies? What formal or informal learning opportunities have been available?

- What barriers or challenges have you encountered in developing STEM-related competencies? How have you addressed these challenges?

- How has developing these competencies affected your professional identity as an HR practitioner? Has there been any tension between your HR identity and developing technical knowledge?

- Could you share a specific example of how you've applied STEM knowledge in your HR role? What was the situation, what actions did you take, and what was the outcome?

- How has your understanding of technical concepts changed the way you approach HR functions like talent acquisition, development, or organizational design?

- In what ways has developing these competencies changed your relationships or interactions with technical specialists in your organization?

- Have you encountered any resistance from either HR colleagues or technical specialists when applying interdisciplinary approaches? How have you navigated this?

- What organizational outcomes or benefits have you observed resulting from interdisciplinary approaches?

- How have you approached measurement or demonstration of value from these interdisciplinary competencies?

- How would you describe your organization's learning culture, particularly regarding cross-functional or interdisciplinary development?

- What role have organizational leaders (both HR and technical) played in supporting or hindering interdisciplinary competency development?

- How do resource availability and constraints in your organization affect development opportunities?

- [For participants from small/medium organizations] How have you adapted development approaches to work within the constraints of a smaller organization?

- How does your industry context influence the need for and approach to developing STEM competencies among HR professionals?

- How do you see the relationship between HR and STEM fields evolving in the future? What new competencies might be required?

- What advice would you give to other HR professionals seeking to develop interdisciplinary STEM competencies?

- What recommendations would you make to organizations wanting to build more effective development systems for interdisciplinary competencies?

- Is there anything else about your experience developing and applying interdisciplinary competencies that we haven't covered that you'd like to share?

- Do you have any questions about the research or how your input will be used?

- Thank participant for their time

- Explain next steps in the research process

- Provide contact information for any follow-up questions

Appendix C: Organizational Case Study Protocol

- How had the organization conceptualized and operationalized interdisciplinary STEM competencies for HR professionals?

- What specific approaches had the organization implemented to develop these competencies?

- How were these approaches selected and adapted to the organizational context?

- What implementation challenges were encountered, and how were they addressed?

- What formal and informal measurement approaches were used to evaluate outcomes?

- How had different stakeholder groups perceived and experienced these initiatives?

- What organizational factors enabled or hindered implementation?

- What outcomes were observed at individual and organizational levels?

- How sustainable were these approaches within the organization's resource constraints?

- How did diversity, equity, and inclusion considerations factor into program design and implementation?

- HR competency frameworks and job descriptions

- Development program descriptions and materials

- Organizational charts showing HR-technical relationships

- Learning and development strategy documents

- Program evaluation data and metrics

- Internal communications about interdisciplinary initiatives

- Relevant policies and procedures

- Records of attendance/participation in development activities

- Historical documents showing program evolution

-

HR Professionals (3-4 interviews per organization)

- a.

- Range of seniority levels (junior to senior)

- b.

- Various HR specializations (generalists, talent acquisition, L&D, etc.)

- c.

- Different levels of program participation

-

Technical Leaders/Specialists (1-2 interviews per organization)

- a.

- Those who had participated in knowledge-sharing or mentorship

- b.

- Those involved in program design or delivery

-

Organizational Leadership (1-2 interviews per organization)

- a.

- HR leadership

- b.

- Technical function leadership

- c.

- General management (where relevant)

-

Program Designers/Administrators (1 interview per organization)

- a.

- Those responsible for program development and implementation

- Experience with development approaches

- Perceived value and effectiveness

- Application of developed competencies

- Implementation barriers and enablers

- Outcomes and impact

- Experience sharing knowledge with HR

- Observed changes in HR capabilities

- Bidirectional learning experiences

- Perceived value and challenges

- Impact on technical-HR collaboration

- Strategic rationale for development initiatives

- Resource allocation decisions

- Perceived organizational impact

- Measurement approaches

- Future vision and priorities

- Program design considerations

- Implementation challenges and adaptations

- Measurement approaches

- Contextual factors affecting implementation

- Lessons learned and evolution

- Development program sessions

- Cross-functional meetings

- Technical-HR collaborative activities

- Mentorship interactions

- Community of practice gatherings

- Nature and quality of interactions

- Participation patterns and dynamics

- Knowledge-sharing approaches

- Evidence of implementation mechanisms

- Contextual factors influencing activities

- Chronological narrative construction documenting the organization's journey in developing interdisciplinary competencies

- Thematic analysis across data sources using both deductive codes (derived from theoretical framework) and inductive codes (emerging from data)

-

Implementation mechanism analysis examining evidence of the four key mechanisms:

- a.

- Contextual knowledge acquisition

- b.

- Identity boundary-spanning

- c.

- Psychological safety

- d.

- Practical application scaffolding

-

Barrier and enabler identification focusing on:

- a.

- Resource factors

- b.

- Cultural factors

- c.

- Structural factors

- d.

- Leadership factors

- e.

- Measurement approaches

-

Outcome assessment across:

- a.

- Individual competency development

- b.

- HR function effectiveness

- c.

- Technical-HR collaboration

- d.

- Organizational outcomes

-

Contextual factors:

- Size (small, medium, large)

- Industry (technology-intensive vs. less technology-intensive)

- Learning culture characteristics

- Program maturity (emerging vs. established)

-

Implementation approaches:

- Primary development methods

- Resource intensity

- Formal vs. informal structures

- Integration with existing systems

-

Effectiveness patterns:

- Relative effectiveness of approaches by context

- Implementation mechanisms across contexts

- Barrier patterns and solutions

- Outcome similarities and differences

-

Sustainability considerations:

- Resource sustainability

- Temporal sustainability (adaptability)

- Social sustainability (equity and inclusion)

- Multiple data sources were triangulated for each case

- Member checking was conducted with key informants to validate case descriptions and interpretations

- Researcher triangulation involved multiple researchers in data collection and analysis

- Audit trail documented all data collection, analytical decisions, and interpretive processes

- Rival explanations were actively sought and examined for each case

- Cross-case pattern matching strengthened analytical generalizations

- Informed consent was obtained from all interview participants and for observations

-

Confidentiality was maintained through:

- Data security procedures

- Anonymization of individual participants

- Organizational anonymity (if requested)

-

Reciprocity was ensured by:

- Providing case organizations with summary findings

- Offering recommendations based on cross-case insights

- Sharing broader study results upon completion

-

Researcher reflexivity was maintained through:

- Research team debriefings

- Reflection journals

- Explicit consideration of researcher positionality

- 1.

-

Preparation (1 week)

- ○

- Initial contact and agreements

- ○

- Preliminary document collection

- ○

- Interview scheduling

- 2.

-

Primary data collection (2-3 weeks)

- ○

- Document analysis

- ○

- Stakeholder interviews

- ○

- Observations (where applicable)

- 3.

-

Follow-up data collection (1 week)

- ○

- Clarification interviews

- ○

- Additional document requests

- ○

- Member checking

- 4.

-

Analysis (2-3 weeks)

- ○

- Within-case analysis

- ○

- Preliminary case description

- ○

- Validation with key informants

- 5.

-

Integration (ongoing)

- ○

- Integration with cross-case analysis

- ○

- Identification of distinctive and common patterns

- ○

- Theoretical and practical implications

References

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2022). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (6th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532-550.

- Higgins, M. C., Dobrow, S. R., & Chandler, D. E. (2022). Developmental networks in the 21st century: Extended, enhanced, and evolved. Academy of Management Annals, 16(1), 257-290.

- Johnson, R., Garcia, M., & Williams, T. (2023). Mind the gap: HR professionals' technology competency in digital organizations. Human Resource Development International, 26(1), 78-96.

- Kram, K. E., & Isabella, L. A. (2022). Mentoring alternatives: The role of peer relationships in career development. Academy of Management Journal, 65(3), 392-410.

- Miscenko, D., & Day, D. V. (2022). Identity dynamics in professional development: A multilevel perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 32(3), 100845.

- Morris, T. H. (2022). Experiential learning for professional development: A meta-analysis. Studies in Continuing Education, 44(2), 190-211.

- Repko, A. F., & Szostak, R. (2020). Interdisciplinary research: Process and theory (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Rivera, M. J., Thompson, L., & Williams, T. (2023). Scaling interdisciplinary development: Implementation strategies across organizational contexts. Human Resource Development Review, 22(1), 87-109.

- Sterling, S. (2021). Sustainable education: Re-visioning learning and change. Green Books.

- Taylor, K., & Peterson, D. (2023). Experiential learning effectiveness: A meta-analysis of learning outcomes. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 22(2), 210-228.

- Ulrich, D., Kryscynski, D., Ulrich, M., & Brockbank, W. (2021). HR competence models for a digital age: Research, implications, and applications. Human Resource Management Review, 31(4), 100821.

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). (1987). Our common future. Oxford University Press.

- Yang, B., Watkins, K. E., & Marsick, V. J. (2022). The learning organization: An update on empirical research and theory building. The Learning Organization, 29(1), 51-64.

| Development Approach | β | SE | t | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bidirectional Mentorship | 0.42 | 0.05 | 8.40 | < 0.001 |

| Action Learning Projects | 0.38 | 0.05 | 7.60 | < 0.001 |

| Communities of Practice | 0.29 | 0.06 | 4.83 | < 0.001 |

| Cross-Functional Rotations | 0.27 | 0.06 | 4.50 | < 0.001 |

| Technology Labs/Simulations | 0.23 | 0.07 | 3.29 | < 0.01 |

| External Expert Networks | 0.19 | 0.07 | 2.71 | < 0.01 |

| Digital Learning Platforms | 0.15 | 0.07 | 2.14 | < 0.05 |

| Development Approach | Cognitive Dimension β | Functional Dimension β | Integrative Dimension β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bidirectional Mentorship | 0.35*** | 0.41*** | 0.48*** |

| Action Learning Projects | 0.29*** | 0.45*** | 0.36*** |

| Communities of Practice | 0.38*** | 0.22** | 0.30*** |

| Cross-Functional Rotations | 0.18* | 0.32*** | 0.28*** |

| Technology Labs/Simulations | 0.31*** | 0.21** | 0.18* |

| External Expert Networks | 0.28*** | 0.16* | 0.15* |

| Digital Learning Platforms | 0.32*** | 0.11 | 0.05 |

| Development Approach | Small Orgs β | Medium Orgs β | Large Orgs β | Size x Approach Interaction β |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bidirectional Mentorship | 0.38*** | 0.40*** | 0.43*** | 0.12* |

| Cross-Functional Rotations | 0.21** | 0.26*** | 0.36*** | 0.24*** |

| Action Learning Projects | 0.39*** | 0.35*** | 0.34*** | -0.09 |

| Communities of Practice | 0.32*** | 0.28*** | 0.27*** | -0.08 |

| Technology Labs/Simulations | 0.12 | 0.18* | 0.22** | 0.18** |

| External Expert Networks | 0.25*** | 0.21** | 0.18* | -0.14* |

| Digital Learning Platforms | 0.25*** | 0.18* | 0.10 | -0.21** |

| Theme | Interview Mentions (n=37) | Case Study Evidence (n=6) |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation Mechanisms | ||

| Contextual knowledge acquisition | 31 (84%) | 6 (100%) |

| Identity boundary-spanning | 26 (70%) | 5 (83%) |

| Psychological safety | 23 (62%) | 6 (100%) |

| Practical application scaffolding | 29 (78%) | 6 (100%) |

| Implementation Barriers | ||

| Resource constraints | 33 (89%) | 6 (100%) |

| Disciplinary identity concerns | 21 (57%) | 4 (67%) |

| Measurement challenges | 28 (76%) | 6 (100%) |

| Access inequities | 19 (51%) | 5 (83%) |

| Organization | Primary Approaches | Implementation Adaptations | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Company (8,000+ employees) | • 2-week technical immersions • Action learning projects • HR Innovation Lab • Formal mentorship program |

• Rotational coverage system • Executive sponsorship • Integrated with career paths • Formal ROI measurement |

• 37% increase in STEM fluency • 28% improvement in technical talent retention • Enhanced strategic input on technology implementations |

| Technology Firm (800 employees) | • Cross-functional project teams • Monthly tech talks • Digital badges for STEM competencies • Technical shadowing |

• Integration with existing projects • Asynchronous learning options • Technical specialist incentives • Quarterly learning sprints |

• Improved technical recruiting efficiency • Enhanced HR credibility with technical teams • More effective technical onboarding processes |

| Biotechnology Startup (45 employees) | • "Technical Tuesday" lunches • HR in technical stand-ups • Shared Slack channels • External learning resources |

• Micro-learning approach • Integration with daily workflows • Limited formal structure • Leveraging external expertise |

• Improved technical job descriptions • Enhanced communication between HR and R&D • More effective talent attraction strategies |

| Manufacturing Company (1,200 employees) | • HR-Engineering exchange program • Problem-solving workshops • Technical skill spotlights • Online learning platform |

• Union partnership • Focus on production technologies • Multi-site coordination • Multilingual resources |

• Improved technical workforce planning • Enhanced HR support for automation transitions • Better talent development for technical roles |

| Healthcare System (3,500 employees) | • Clinical technology rotations • "HR in the Lab" program • Communities of practice • Technical leader mentorship |

• Patient care considerations • Multi-discipline approach • Clinical staff involvement • Regulatory compliance focus |

• Better clinical staff development pathways • Improved talent strategies for specialized roles • Enhanced change management for technology implementation |

| Professional Services (400 employees) | • Client-based learning projects • Technical associate partnerships • External expert webinars• Practice group immersions |

• Client confidentiality protocols • Billable hours considerations • Practice-specific approaches • Consultant partnership model |

• Enhanced technical service offerings • Improved technical talent acquisition • Better alignment between HR and client needs |

| Organization Context | Recommended Primary Approaches | Implementation Strategies | Addressing Common Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Organizations (<100 employees) | • Bidirectional mentorship • Communities of practice • Digital learning platforms • External expert networks |

• Integrate learning into existing workflows • Leverage free/low-cost external resources • Focus on high-priority technical domains • Create micro-learning opportunities |

• Use job-sharing to create development time • Partner with other small organizations • Leverage technical staff as internal faculty • Create simple, targeted measurement approaches |

| Medium Organizations (100-5,000 employees) | • Action learning projects • Communities of practice • Bidirectional mentorship• Technical immersions |

• Create formal/informal hybrid programs • Develop internal knowledge sharing systems • Establish cross-functional project teams • Implement technical shadowing programs |

• Dedicate specific budget for interdisciplinary development • Create recognition systems for knowledge sharing • Establish clear competency expectations • Balance standardization with flexibility |

| Large Organizations (>5,000 employees) | • Cross-functional rotations • Bidirectional mentorship • Action learning projects • Technology labs |

• Establish formal rotational programs • Create centers of excellence • Develop comprehensive competency frameworks • Implement formal measurement systems |

• Address bureaucratic barriers to cross-functional work • Ensure equitable access across locations • Develop consistent global implementation • Create executive sponsorship programs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).