1. Introduction

A growing interest in plant-derived compounds has emerged in recent years, owing to their nutritional, medicinal, and economic importance. Among these compounds, truffles from the genus Tuber are especially esteemed for their distinct flavor and high demand in the market [

1,

2]. The predominant species in Romania is Tuber aestivum, which is commonly found throughout Europe, while the rarer Tuber magnatum is confined to certain southern regions [

3,

4,

5,

6]. White truffles (T. magnatum), highly coveted as gourmet ingredients, also exhibit significant bioactive properties such as antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory effects [

6,

7]. This makes them valuable not only in culinary uses but also in pharmaceutical and cosmetic fields.

Truffle quality is influenced by factors such as soil composition, climate, and regional vegetation [

8,

9,

10]. Beyond their culinary appeal, truffles provide notable health benefits due to their rich antioxidant content, particularly polyphenolic compounds, which help combat oxidative stress and inflammation [

11,

12,

13]. Tuber magnatum is nutritionally dense, containing essential B vitamins (riboflavin, niacin, pantothenic acid) for energy metabolism, along with key minerals like calcium, potassium, and magnesium, which support bone and cardiovascular health. Additionally, their dietary fiber promotes gut health. Truffles’ antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties also hold promise in dermatology, potentially aiding in skin repair and anti-aging treatments. Despite their therapeutic potential, further research is needed to explore their secondary metabolites for pharmaceutical applications [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Romanian white truffles (Tuber magnatum) have long captivated gastronomes with their exceptional flavor and aroma. However, beyond their culinary allure, these truffles possess a complex chemical profile that may offer valuable therapeutic benefits. This study delves into the untapped potential of Romanian white truffles by examining their phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, and metal composition. By employing various solvents for maceration, we aim to uncover the truffles' bioactive constituents and their efficacy as natural antioxidants. Additionally, we investigate the safety and nutritional value of these truffles through a detailed analysis of their metal content. This exploration not only highlights the multifaceted value of Romanian white truffles but also opens new avenues for their application in pharmaceutical and nutraceutical fields.

This study aims to explore and maximize the therapeutic potential of Romanian white truffles (Tuber magnatum), focusing on their bioactive compounds and antioxidant properties. By integrating insights from existing literature, this research seeks to evaluate their efficacy in neutralizing oxidative stress, a key factor in aging and various chronic diseases. Understanding the phytochemical composition and biological activity of these truffles could provide valuable implications for functional foods, nutraceuticals, and pharmaceutical applications, highlighting their potential role in promoting human health and well-being. To extract pharmaceutical compounds from Tuber magnatum, four distinct macerates were created using various solvents: deionized water, ethanol (at concentrations of 70% and 96%), and methanol. The identification and quantification of polyphenols and flavonoids in the truffle macerates were performed using spectrophotometric techniques. Furthermore, the evaluation of antioxidant capacity was conducted through two methods: the DPPH free radical scavenging method and the ferric reducing power (FRAP) analysis. Additionally, the analysis of the samples included an assessment of the metals found in the white truffle species, executed through spectrophotometric GF-AAS and FAAS methods. This examination takes into consideration the environmental conditions in which these truffles thrive.

To deeper exploring the therapeutical potential of compounds identified by experimental works, in silico ADME predictions are cost-effective methods using computer-based procedures to forecast how a drug or chemical compound will be absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted (ADME) in the body. These predictions are valuable in the early stage of drug discovery and development, for identifying promising drug candidates and optimizing their properties. The structure’s optimization can be further applied to reduce the risk of late-stage failures due to poor ADME characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Extract Preparation

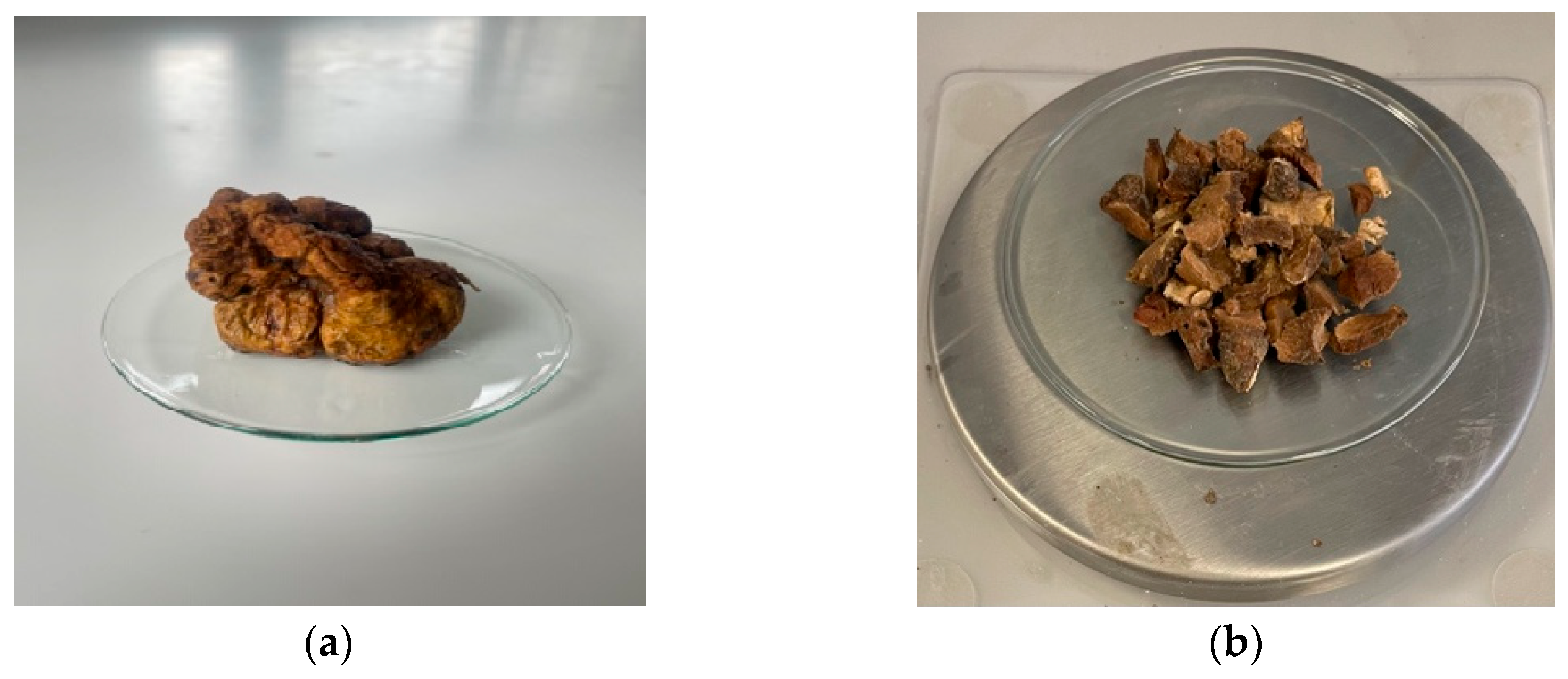

The fresh fruiting bodies of Tuber magnatum Pico (

Figure 1) were harvested in November 2023 from the southern region of the Eastern Carpathians, an area known for its suitable ecological conditions for truffle growth. Field identification was performed based on habitat characteristics, host plant associations, and macroscopic features, ensuring preliminary species verification. The truffle harvesting process was conducted in accordance with the Romanian Forest Code (Law No. 46/2008, republished), which regulates the sustainable collection of non-wood forest products such as truffles and Law No. 171/2010 on forest-related contraventions. Collection was performed on private land with the explicit consent of the landowner, using manual, non-invasive techniques that comply with current forestry and biodiversity protection regulations. Following collection, the truffles were carefully transported to the laboratory in insulated boxes with ice packs to maintain freshness and prevent microbial contamination, with storage at 4°C for 3 to 12 hours prior to processing.

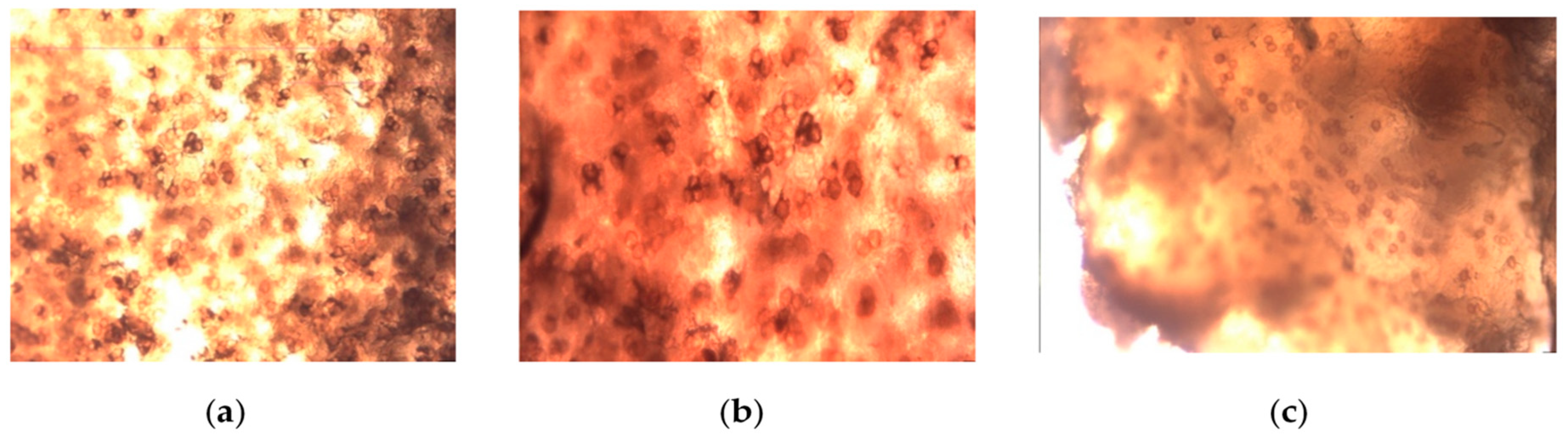

In the laboratory at the Faculty of Pharmacy, “Titu Maiorescu University”, a detailed taxonomic confirmation was carried out through microscopic examination, focusing on ascus and spore morphology. The identification process considered spore shape, size, wall ornamentation, and ascus structure, which are key diagnostic traits for distinguishing Tuber magnatum from other truffle species. This rigorous classification approach ensured the accuracy and authenticity of the collected specimens for further chemical and biological analyses.

Following microscopic examination, the fresh Tuber magnatum truffles underwent a thorough cleansing process to eliminate soil particles and impurities. The truffles were washed multiple times using potable and deionized water, ensuring maximum purity before further processing. After washing, they were carefully placed in a single layer on a sieve to allow excess water to drain naturally. For standardized sample preparation, the ascocarps were sliced into thin pieces (~1 cm thick) using a sharp knife. Once fully dried, the slices were further shredded into smaller fragments and stored in airtight bags to preserve their chemical integrity. These samples were then frozen at -18°C, ensuring long-term stability and preventing enzymatic degradation.

To extract the truffle samples, various solvents were used in the maceration process, including deionized water, 70% ethyl alcohol, 96% ethyl alcohol, and methyl alcohol. The maceration was carried out for 72 hours at room temperature using a truffle-to-solvent ratio of 1:5, optimizing the extraction of both polar and non-polar compounds. All chemical reagents utilized in the study were of analytical grade, sourced from Merck, Germany, ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of the extraction process. The four resulting macerates were designated as follows: TA (deionized water), TE70 (70% ethanol), TE96 (96% ethanol), and TM (methanol). All reagents used were of analytical purity from Merck, Germany.

2.2. Microscopic Examination

By reviewing specialized literature, valuable information was obtained to determine the morphological characteristics of truffle species. Unlike fruits such as pears or apples, which have consistent and recognizable shapes, truffles must adapt to their underground environment, resulting in a diverse range of forms. Truffles can exhibit various shapes, including spherical, elliptical, kidney-shaped, heart-shaped, and other complex forms. The shape of the ascospores, which is a key characteristic in truffle identification, can be observed using a microscope on the fresh fruiting body. In this research, the microscopic examination was conducted with a Motic BA210 LED Binocular Biological Microscope (Motic, Kowloon, Hong Kong), equipped with a camera and various eyepieces.

2.3. Total Phenol Analysis

The concentration of total phenolic compounds was measured using the Folin-Ciocalteau method, according to the ISO 14502-1:2005 standard with minor modifications [

19]. The following materials were used in the experiment: Folin-Ciocalteau reagent (purchased from Sigma Chemical, St. Folin-Ciocalteau reagent (purchased from Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MI, USA), deionized water, a 7,5% sodium carbonate solution, gallic acid (used to create a calibration curve) and a PC VWR UV-630 spectrophotometer (Avantor, Radnor, Pennsylvania,USA). The Folin-Ciocalteau reagent was diluted by a factor of 10. To determine the TPC, 1 mL of each macerate (TA, TE70, TE96, TM) was added to 10 mL volumetric flasks, followed by 5 mL of diluted Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, shaken, then 4 mL of 7.5% sodium carbonate solution was added; the absorbance was measured at 765 nm after 60 minutes.

Known concentrations of gallic acid solutions (10-60 μg/mL) were used to establish the calibration curve. This resulted in a linear regression equation of y = 0.0118x + 0.0973 and a correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.9952. By applying the regression equation, the total concentration of polyphenols in the macerates, expressed in gallic acid equivalents (mg GAE/100 g d.w.), was determined. Each measurement was performed in triplicate, and data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

2.4. Total Flavonoid Analysis

In line with the Romanian Pharmacopoeia (10th ed., 2020) guidelines for “Cynarae folium”, the total flavonoid content in white truffle (Tuber magnatum pico) was determined by forming a yellow complex through the reaction of flavones with aluminum chloride and sodium acetate [

20,

21]. To determine the total flavonoid content, a calibration curve was plotted, and TFC values were calculated using the equation y = 0.0361x + 0.028, with a correlation coefficient (R² = 0.9991). The absorbance of this complex was measured at 430 nm to quantify the flavones. The flavonoid content was expressed as mg rutin/100 g dry weight and all analyses were conducted in triplicate and reported as mean ± standard deviation.

2.5. Antioxidant Activity

2.5.1. DPPH Radical-Scavenging Activity

The antioxidant capacity was assessed using the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging assay. Gallic acid (GA) served as the standard for constructing calibration curves, and the results were expressed as gallic acid equivalents (mg GAE) [

22,

23,

24].

For the calibration curve, varying volumes of gallic acid standard solutions were transferred into 25 mL calibrated flasks, followed by the addition of 5 mL of 0.063% DPPH solution (1.268 mM) in methanol. The flasks were then filled to the mark with methanol and left in the dark at room temperature for 45 minutes. Absorbance was measured at 530 nm against a methanol blank. Before analysis, the DPPH solution spectrum was recorded, confirming the maximum absorbance at 530 nm.

DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) was purchased from Aldrich (Germany). The 0.063% (1.268 mM) DPPH stock solution was prepared in a 200 mL calibrated flask by dissolving 0.0010 g of DPPH in methanol. Absorbance measurements were performed using a VWR UV-6300PC spectrophotometer (Avantor, Radnor, Pennsylvania, USA).

To determine the antioxidant capacity of the samples, 1 mL of each extract was added to 25 mL calibrated flasks, followed by 5 mL of DPPH solution (1.268 mM). The flasks were brought to volume with methanol and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 45 minutes. Absorbance was then recorded at 530 nm, using methanol as a blank.

The calibration curve generated from standard solutions (10–60 μg/mL) yielded the linear regression equation y = - 0.4075x + 2.4073 with R² = 0,9991. Antioxidant activity was calculated and expressed as mg GAE/100 g dry weight. All measurements were carried out in triplicate, and values are reported as mean ± standard deviation.

2.5.2. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

The FRAP assay is an efficient, rapid and cost-effective technique for the direct assessment of the total antioxidant reducing activity of antioxidants in a given sample [

25,

26]. This method is based on the conversion of ferric ions (Fe

3+) to ferrous ions (Fe

2+) as an indicator reaction, which is accompanied by a visible color change. The FRAP assay was performed according to the method of Benzie and co-workers with minor modifications. The freshly prepared FRAP reagent, containing sodium acetate buffer (300 mmol/L, pH 3.6), 10 mmol/L TPTZ in 40 mmol/L HCl, and FeCl

3 * 6H

2O solution (20 mmol/L) in a 10:1:1 (v/v/v) ratio, was warmed to 37°C before use. Each 100 μl of sample was added to 3 mL FRAP reagent, and the absorbance was recorded at 593 nm after 4 min. The same procedure was repeated for FeSO

4 . 7H

2O standard solution using several concentrations 100, 250, 500, 750, and 1000 μmol/L to construct the calibration curve. The calibration curve showed a positive linear correlation (y = 0,158x + 0,135; R

2 = 0.9882) between the mean FRAP value and the concentration of FeSO

4-7H

2O standards. Sample FRAP values were calculated from the standard curve equation and expressed as µmol Fe

2+/g d.w. Each determination was performed in triplicate, and results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. All reagents used were of analytical purity from Merck, Germany.

2.6. Metal Concentration in White Truffle

Fungi such as truffles require trace elements like copper, manganese, and zinc for essential enzymatic functions; however, excessive accumulation of certain metals can pose toxicological risks. However, an excess of these elements in soil can become toxic to both plants and micro-organisms. In contrast, lead and cadmium, heavy metals that are not essential for plant functioning, can also be harmful. Therefore, in the white truffle sample studied, the concentration of some toxic metals (Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, Mn and Pb) was determined using graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry GF-AAS, and the concentration Ca, K, Na and Mg, was determined by flame atomic absorption spectrometry (FAAS).

2.6.1. Heavy Metals Detection by GF-AAS

To accurately determine the presence Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, Mn and Pb, the graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry (GF-AAS) technique is usually used. In this particular study, the samples were calcined using a calcination furnace, and the resulting ash was dissolved in an acid solution in a crucible. The analysis utilized a PerkinElmer AAnalyst 800 atomic absorption spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, Massachusetts, USA) which was equipped with an autosampler and AS-800 cooling system. Only reagents of recognized analytical grade (Merck, Germany), such as ultrapure water, HCl (hydrochloric acid) 37%, HNO3 (nitric acid) 65% and H2O2 (hydrogen peroxide) were used for the analysis. Concentrated metal standard solutions were prepared using high-purity metals, oxides or non-hygroscopic salts and were diluted with water and redistilled nitric or hydrochloric acid. These diluted solutions served as working standard solutions with a concentration of 1000 mg/L at the time of analysis. In addition, a mixture of ammonium hydrogen phosphate and magnesium nitrate was used as matrix modifiers.

2.6.2. Metal Detection by FAAS

Metal concentrations (Ca, Na, K, Mg) were measured using atomic absorption spectrometry with an AA 700 spectrometer from Analytic Jena, Jena, Germany. A 0.5 g sample of dry white truffle powder was mineralized by adding 5 mL of nitric acid (Merck, Germany) and 40 mL of deionized water, heated to 120°C for 130 minutes. The resulting solution was filtered into 50 mL volumetric flasks and topped up with deionized water.

2.7. Statistical Data

The experiments were conducted three times to ensure accuracy and reliability. To analyze the data, the mean standard deviation (± SD) was calculated, and variance analysis (ANOVA) was performed using the GraphPad Prism 10 statistical software. A probability value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed in triplicate (n = 3).

2.8. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) Predictions

Estimation of ADME properties was done on four majority constituents of the white truffles’ macerates, namely: gallic acid, ergosterol, L-arginine, and linoleic acid. Estimations were obtained using their SMILE formula as inputs in SwissADME online software [

28].

4. Discussion

The truffle, belonging to the genus Tuber, possesses a unique set of qualities that set it apart from other edible mushrooms. Unlike traditional mushrooms, truffles do not have stems and gills, their mycelium growing predominantly underground. In addition, mature truffles have a firm, dense and woody texture, in contrast to the soft and brittle nature of common mushrooms [

40,

41,

42].

The present research was focused on the identification of phytochemicals with antioxidant role in macerates obtained from Romanian white truffle species. Spectrophotometric analyses were performed to evaluate the antioxidant properties as well as their elemental profile, reflecting the mineral composition of their natural mycorrhizal habitat.

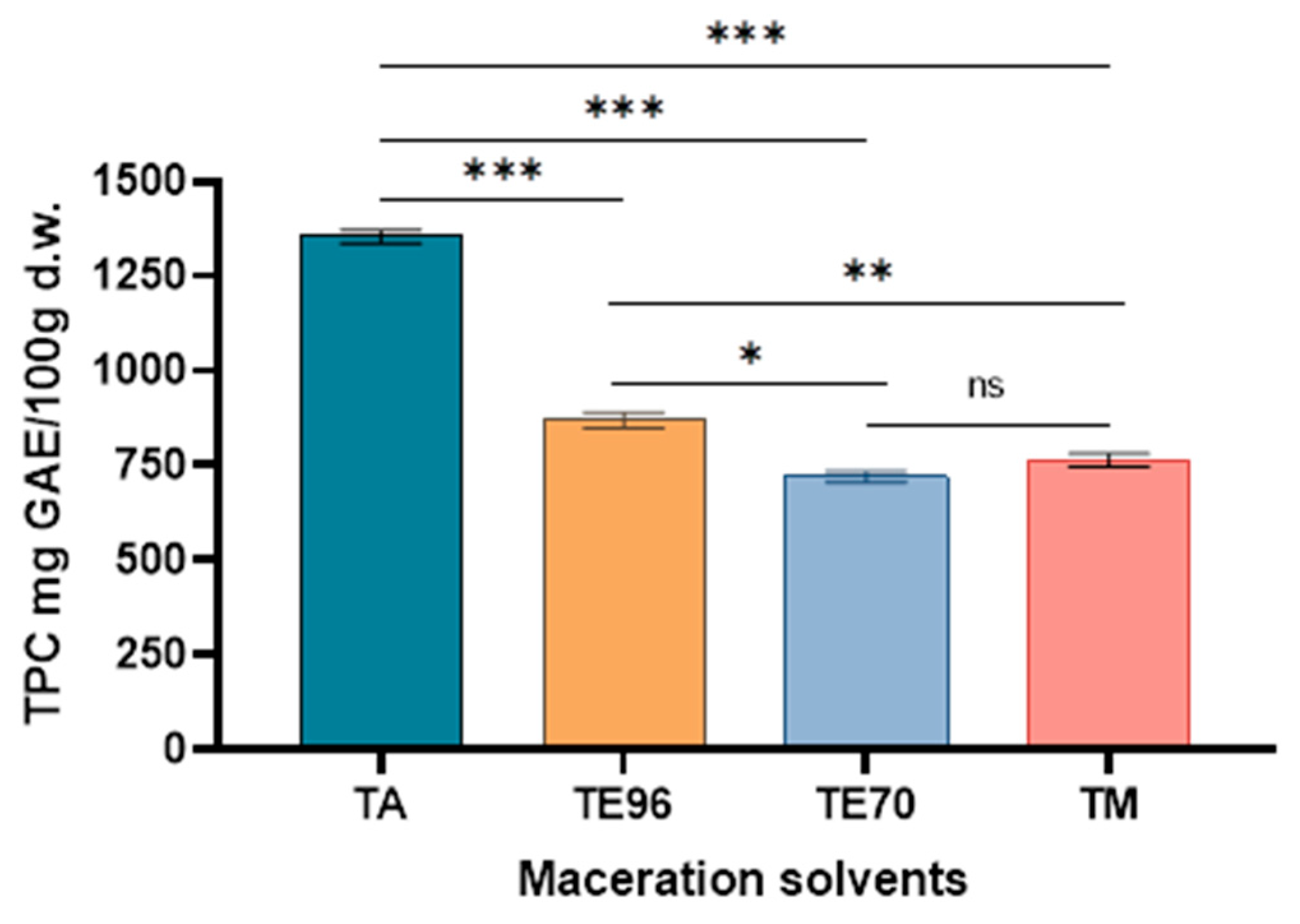

The analysis of TPC and TFC in white truffle (

Tuber magnatum) macerates revealed distinct variations in their concentrations, reflecting differences in the extraction efficiency of polyphenolic and flavonoid compounds depending on the solvent used. TPC values ranged from 721.39 to 1354.34 mg GAE/100 g d.w., whereas TFC values were significantly lower, varying between 117.31 and 198.20 mg rutin/100 g d.w. This notable difference suggests that white truffles contain a higher proportion of total polyphenols compared to flavonoids, a trend commonly observed in fungal extracts. These results are in agreement with research carried out by Tejedor-Calvo et al. and Piatti et al. [

43,

44].

In terms of solvent efficiency, deionized water (TA) was the most effective for TPC extraction, yielding the highest polyphenol content (1354.34 mg GAE/100 g d.w.), while the lowest was recorded for the ethanol-based macerate (TE70). This result indicates that highly polar solvents, such as water, are more efficient at extracting phenolic compounds. In contrast, for TFC, the methanolic extract (TM) exhibited the highest flavonoid content (198.20 mg rutin/100 g d.w.), suggesting that methanol is particularly effective at breaking down cellular structures and solubilizing flavonoids due to its polarity and affinity for flavonoid compounds.

Overall, while both TPC and TFC values were influenced by the choice of solvent, the higher overall polyphenol content suggests that

Tuber magnatum is a richer source of general polyphenols than flavonoids. This distinction is important when considering the bioactive potential of truffle extracts, as polyphenols contribute broadly to antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, whereas flavonoids are particularly known for their role in cellular protection and metabolic regulation [

45].

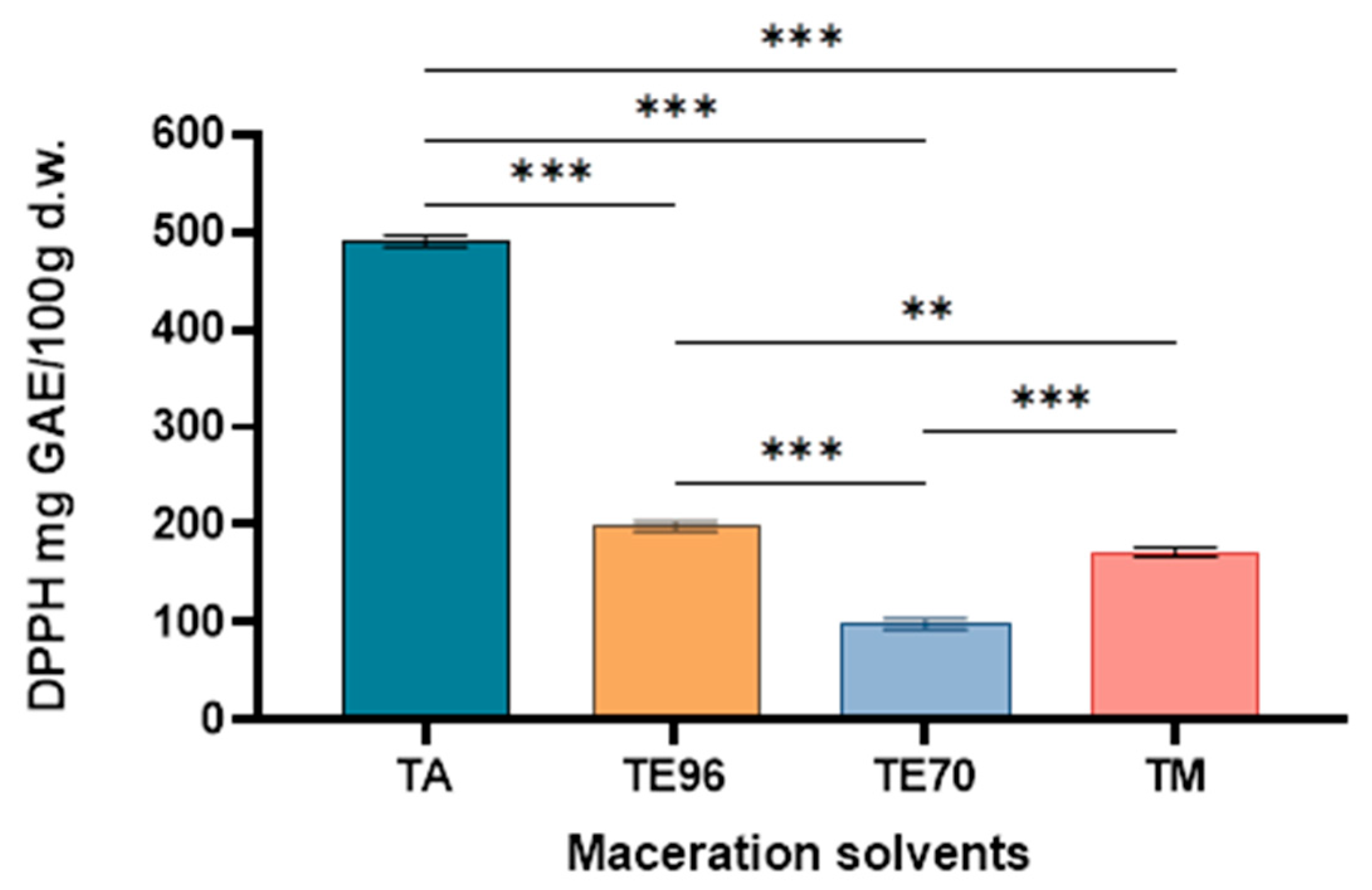

Two spectrophotometric methods, DPPH and FRAP, were employed to assess antioxidant activity. This antiradical activity demonstrated a strong correlation with both total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC). The DPPH results demonstrated significant variation in antioxidant activity among the Tuber magnatum macerates, depending on the extraction solvent. The aqueous macerate (TA) showed the highest antioxidant capacity (490.32 mg GAE/100g d.w.), highlighting the effectiveness of water in extracting polar antioxidant compounds. In contrast, the extracts obtained with 70% ethanol (198.59 mg GAE/100g d.w.), methanol (172.34 mg GAE/100g d.w.), and 96% ethanol (98.27 mg GAE/100g d.w.) exhibited lower scavenging activities.

These differences may be attributed to the polarity of the solvents and their ability to solubilize different classes of antioxidant compounds. Water, being the most polar solvent, likely facilitated the extraction of highly polar phenolic compounds, which contributed significantly to the observed radical scavenging activity. On the other hand, the reduced antioxidant capacity of the 96% ethanol extract suggests that highly non-polar or less polar constituents do not play a major role in the antioxidant potential of Tuber magnatum.

The use of gallic acid as a standard allowed for a reliable comparison of antioxidant activity across samples, with results expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per 100 g dry weight. The findings highlight the importance of solvent selection in maximizing the recovery of bioactive compounds with antioxidant properties and suggest that aqueous extracts of Tuber magnatum may offer superior functional benefits in nutraceutical or pharmaceutical applications.

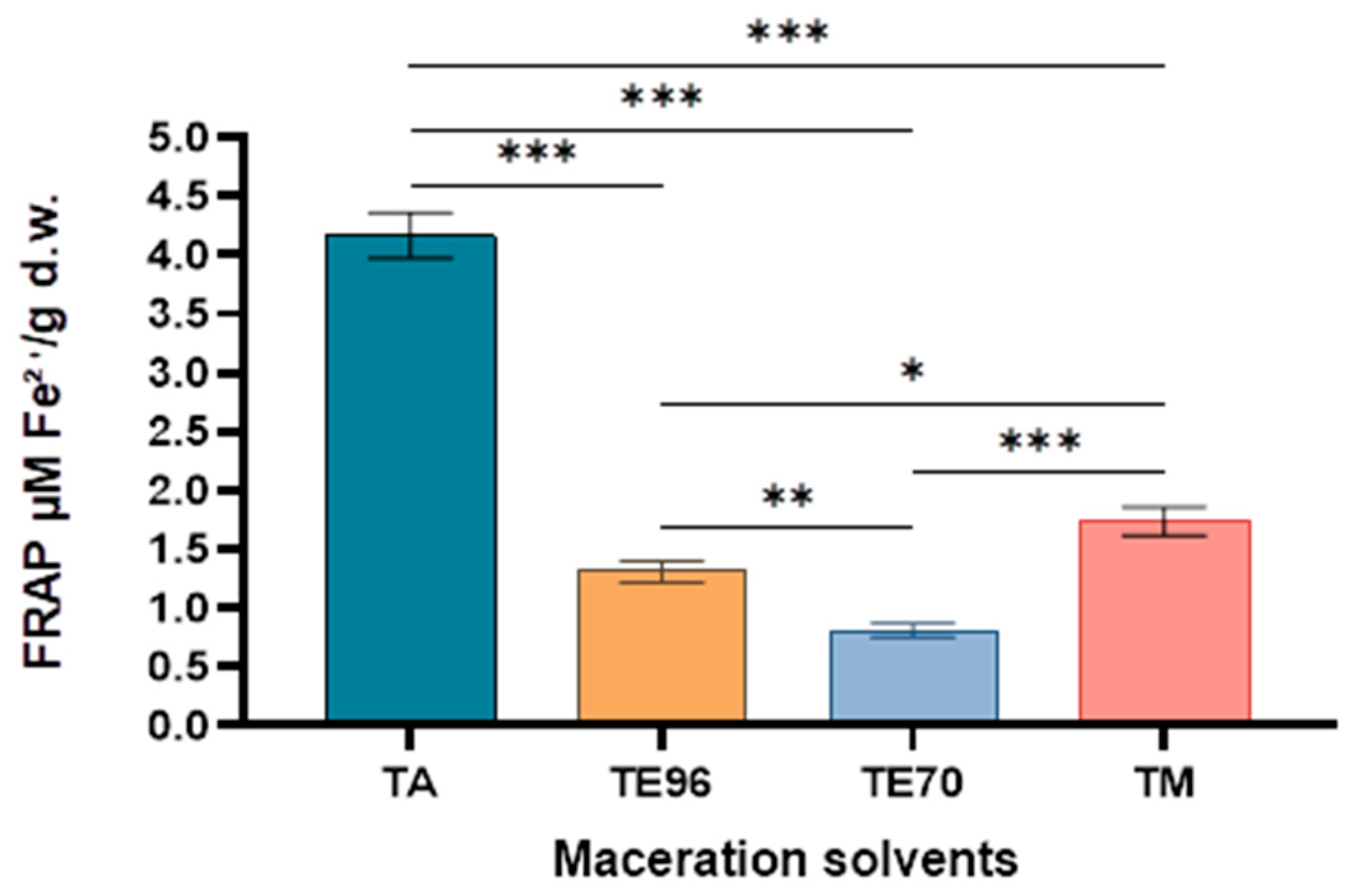

In the FRAP assay for antioxidant activity, the highest values were recorded for the TA macerate (aqueous solvent), followed by TM > TE70 > TE96, with values ranging from 0.81 to 4.17 micromoles Fe

2+/g d.w. The results indicated that the choice of solvent had a significant impact on the extraction yield, which can be attributed to the differing polarities of the solvents, directly influencing the number of bioactive compounds extracted. Consequently, using aqueous solvents for antioxidant compounds extraction, a common practice in traditional medicine, presents a safer alternative to other potentially hazardous polar solvents. These findings are consistent with similar observations reported in the extraction of medicinal plants [

46,

47].

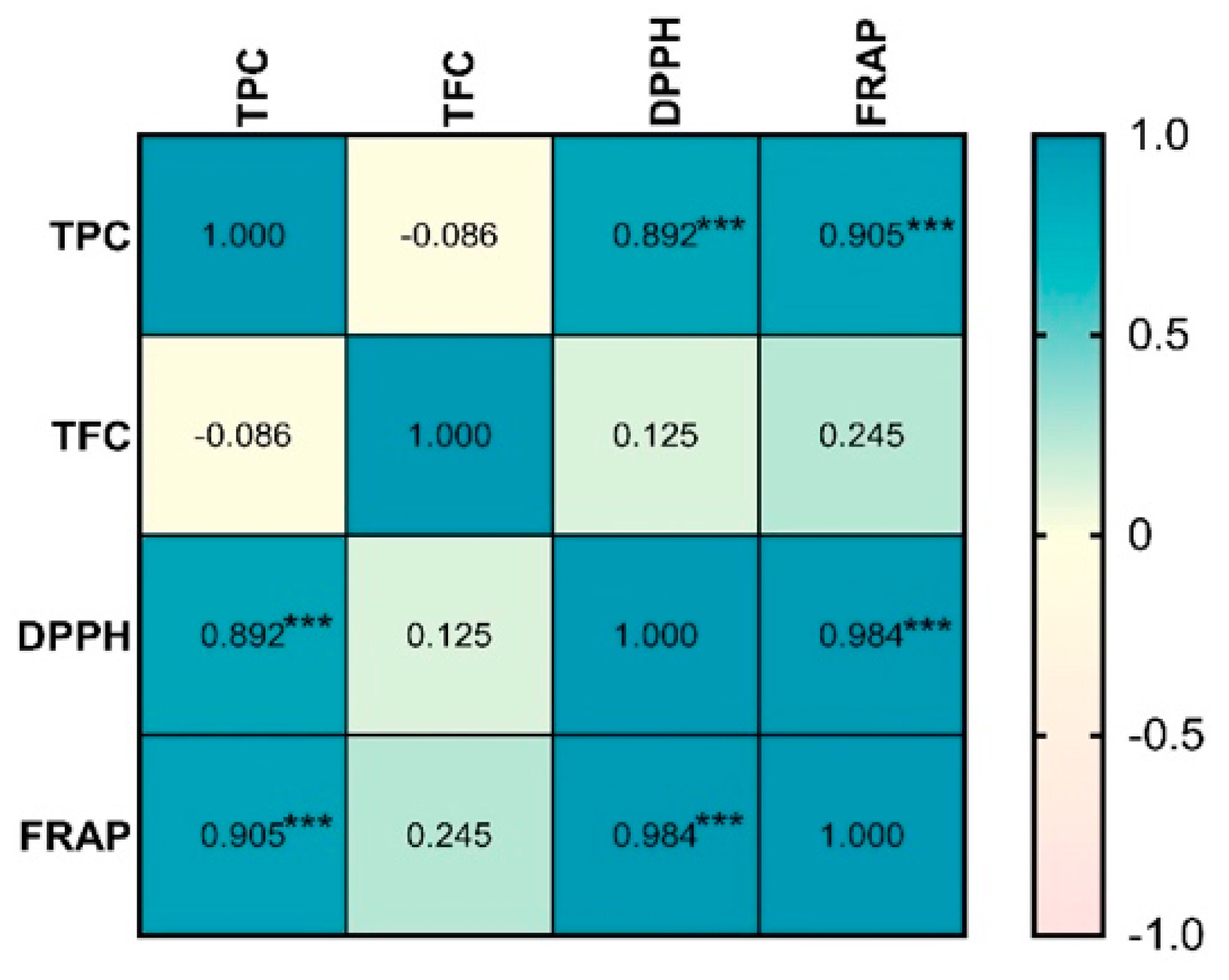

The significant antioxidant activity observed in

Tuber magnatum pico macerates is strongly associated with their total phenolic content, as demonstrated by the results of the Spearman correlation analysis (

Figure 8). This suggests that phenolic compounds are the primary contributors to the antioxidant potential. Among these, gallic acid has been identified as a major phenolic metabolite in truffles, particularly in aqueous and hydroalcoholic extracts [

48]. Gallic acid is well known for its potent radical-scavenging activity, as well as its anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects, making it highly relevant for dermatological applications.

Due to its low molecular weight, high polarity, and favorable skin permeability, gallic acid can be efficiently absorbed through the skin barrier and may act both as a direct antioxidant and as a modulator of oxidative stress-related signaling pathways in skin cells. Previous studies have shown that gallic acid can inhibit the activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), protect against UV-induced damage, and reduce inflammatory cytokine expression in keratinocytes and fibroblasts [

49,

50].

In the context of truffle macerates, the presence of gallic acid may therefore explain the strong correlation between TPC and antioxidant assays (DPPH and FRAP) and supports the idea that non-flavonoid phenolic acids are the primary bioactive agents. Its biological profile positions gallic acid as a key compound for inclusion in anti-aging, skin-soothing, and photoprotective formulations.

However, to fully harness its therapeutic potential, further studies should focus on confirming its stability, percutaneous absorption, and bioavailability within cosmetic or pharmaceutical formulations, particularly in combination with other truffle-derived metabolites.

The spectrophotometric analysis using GF-AAS and FAAS was employed to assess the concentrations of heavy metals (Cd, Cu, Ni, Mn, Cr) and essential minerals (Ca, K, Mg, Na) in white truffles (

Tuber magnatum pico) from Romania. This analysis provided crucial insights into the safety and nutritional value of these truffles, as well as their potential for use in food and cosmetic applications. The results from GF-AAS revealed that nickel (Ni), lead (Pb) were below the detection limits, which is a positive indication for the safety of these truffles, as both Ni and Pb are known for their toxicological risks. The absence of these metals above the detection threshold ensures that these truffles are safe for consumption and cosmetic use. For the detectable metals, cadmium (Cd) was present at a concentration of 0.00036 mg/kg. Cadmium is a well-known carcinogen and nephrotoxic agent, but the levels found in these truffles were far below the permissible limits set by regulatory authorities, making them safe for human consumption [

33]. Previous studies have shown that cadmium content in mushroom samples ranged from 0.10-0.71 mg/kg

-1 dry weight [

51] to 0.26-3.24 mg/kg

-1 dry weight [

52]. Chromium was detected at a low concentration of 0.00978 mg/kg, posing no significant risk, although higher levels of chromium exposure can lead to skin irritation and health issues [

53,

54]. Copper (Cu), found at 0.1441 mg/kg, was the highest among the detected heavy metals. As an essential trace element, copper supports biological functions like collagen synthesis and antioxidant activity, and the detected level is well below harmful concentrations, suggesting it contributes positively to the truffles' nutritional value [

34]. Manganese (Mn) was present at a trace amount of 0.00010 mg/kg, also below toxic levels, supporting bone formation and metabolism [

39]. Essential minerals analyzed by FAAS showed concentrations of calcium (Ca) > potassium (K) > sodium (Na) at 17.92, 11.98, and 2.31 mg/kg, respectively. Calcium is vital for bone health and skin rejuvenation, potassium for electrolyte balance and cardiovascular health, and sodium, present in a low amount, contributes to fluid balance while aligning with dietary recommendations for moderate intake [

55].

Romanian truffles, renowned for their distinctive flavor and nutritional benefits, have shown promise beyond their culinary applications. Further metal analysis confirmed that levels of lead (Pb) and nickel (Ni) were below detection limits, while cadmium (Cd) levels adhered to regulatory standards. Beneficial concentrations of calcium (Ca), potassium (K), and sodium (Na) were also detected, suggesting potential health and dermatological benefits [

56].

This study underscores the therapeutic potential of Romanian truffles, particularly Tuber magnatum pico, highlighting their rich antioxidant properties, safe metal profiles, and promising applications in skin health. The strong antioxidant activity, largely attributed to their high polyphenol content, suggests that these macerates may be effective in combating oxidative stress, inflammation, and signs of skin aging. From a metabolic standpoint, the efficacy of these compounds depends not only on their intrinsic activity but also on their ability to permeate the skin barrier, resist enzymatic degradation, and maintain bioactivity within the dermal environment. Simple phenolic acids and other low-molecular-weight phenolics appear especially suitable for topical absorption and interaction with skin cells, where they may enhance endogenous antioxidant defenses and modulate inflammatory responses. These findings position Tuber magnatum pico as a valuable natural source of bioactive compounds with dermo-functional potential, supporting its exploration in the pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and cosmeceutical industries. Further research is warranted to optimize delivery systems, assess skin permeability, and validate in vivo efficacy for practical medical and cosmetic applications.

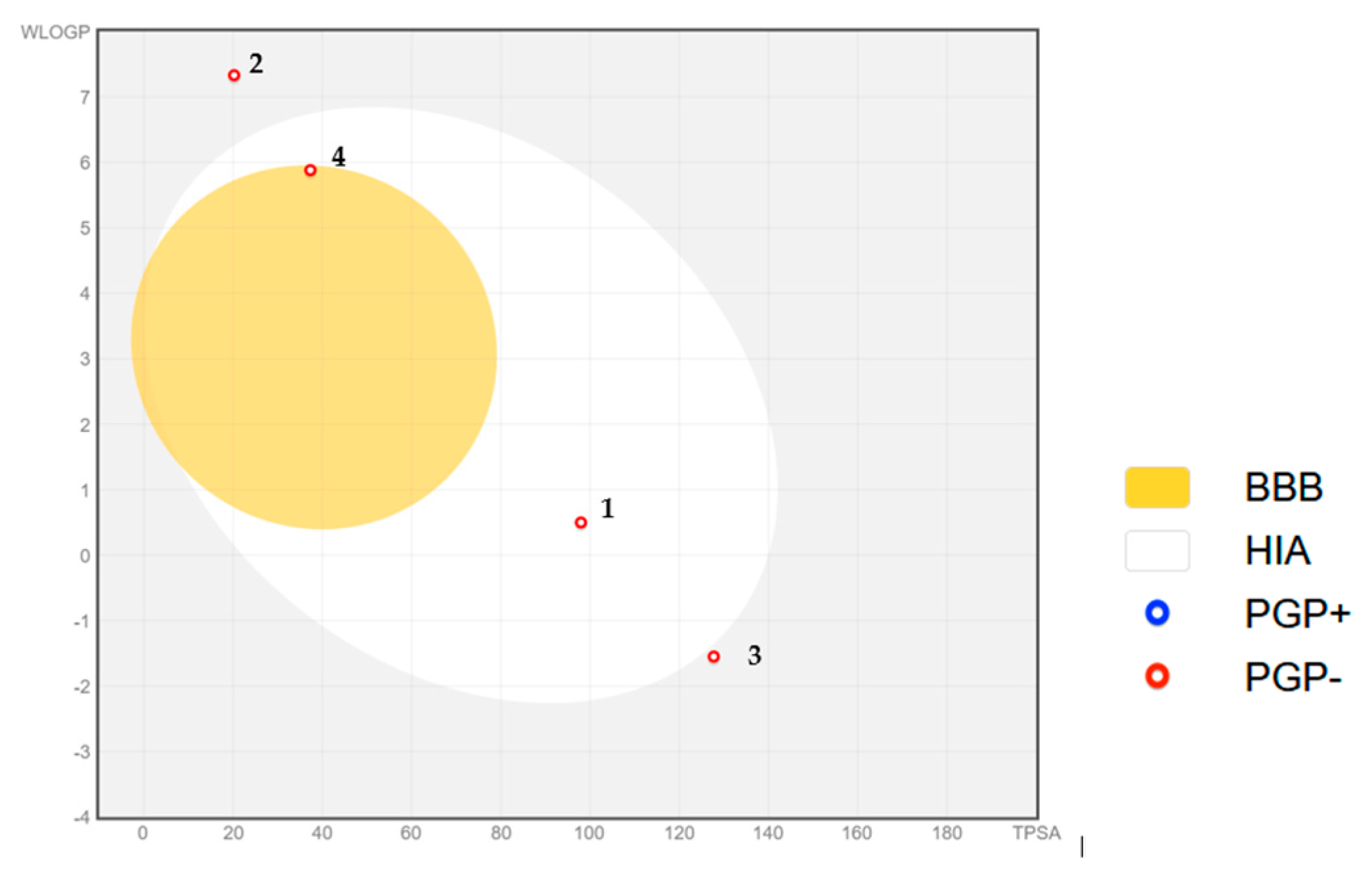

Regarding the estimations of drug-likeness properties, the main findings are that gallic acid exhibits high gastrointestinal absorption. At the same time, all the other investigated compounds have low gastrointestinal absorption, and none of the compounds are blood-brain barrier permeant. The most lipophilic compound is ergosterol, followed by linoleic acid, as shown the values of logP (7.33, and 5.88 respectively), and the most hydrophilic compound is arginine, due to its zwitterionic structure (logP = 1.55), followed by gallic acid (logP = 0.5) due to its 3 hydroxyl substituents and one carboxyl group. The calculated properties are important for establishing structures’ compliance with pharmacological filters stated by Lipinski [

57], Ghose [

58], Veber [

59], Egan [

60], or Muegge [

61] that overall, estimate their bioavailability. Gallic acid obeys all pharmacological restrictions, except Ghose’s rules (with 2 violations: MR < 40, total number of atoms < 20), and Muegge (molecular weight < 200 g

. mol

-1). Ergosterol fails to comply with all pharmacological filters, except Veber’s rule. Arginine fails to comply with Ghose and Muegge's rules, and linoleic acid complies with Lipinski, Veber, and Egan’s rules. Taking into account all molecular descriptors involved in the requirements stated by the above-mentioned pharmacological filters, it results in a bioavailability score of 0.55 for ergosterol, L-arginine, and linoleic acid, and 0.56 for gallic acid. This score is often used in drug discovery and development to assess a compound's potential for oral administration. It can be considered that all these compounds are orally bioavailable, meaning they can be absorbed into the bloodstream after oral administration.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the focus was on examining the antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds found in macerates derived from Romanian white truffles (Tuber magnatum pico). Additionally, the elemental composition of the samples was assessed to determine both nutritional and toxic metal levels.

Aqueous maceration proved to be the most effective extraction method, yielding high levels of polyphenolic metabolites and flavonoids, alongside robust antioxidant activity confirmed by both DPPH and FRAP assays. Therefore, the choice of solvent had a substantial impact on both the concentration of phenolic compounds and their antioxidant efficacy. Among the tested solvents, the aqueous solution showed great potential for white truffles, being also the safest option for human health compared to methanol and ethanol.

The spectrophotometric analysis of Romanian white truffles revealed a safe profile in terms of heavy metal content, with Ni and Pb below detection limits and Cd, Cr, Cu, and Mn present at low, acceptable concentrations. Furthermore, the significant presence of beneficial minerals such as calcium, potassium, and sodium enhances their nutritional value.

In silico predictions based on the BOILED EGG diagram highlighted relevant pharmacokinetic properties of selected truffle-derived metabolites. Gallic acid was predicted to be passively absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract (high HIA), while linoleic acid demonstrated the potential to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB), supporting its possible neuroprotective effects. These findings contribute to a better understanding of the systemic bioavailability of these compounds.

Overall, Romanian white truffles represent a promising natural source of phenolic metabolites with strong antioxidant potential and a favorable elemental profile. These features support their application in functional foods, dermocosmetics, and pharmacological formulations, with no detectable risk from heavy metal contamination. Moreover, due to their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, truffle macerates may be particularly suitable for topical applications targeting oxidative stress, skin aging, and barrier protection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.-M.C., and G.S.; methodology, L.-M.C., G.S., R.C.S., and A.S.; software, C.E.L., A.S., and R.E.C.; validation, L.-M.C., G.S. and C.E.L.; formal analysis, G.S., R.E.C., and A.S.; investigation, L.-M.C., G.S., and R.C.S.; resources, L.-M.C., and G.S.; data curation, R.E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.-M.C., R.C.S., G.S., and C.E.L.; writing—review and editing, L.-M.C., A.S., and G.S.; visualization, R.E.C., and C.E.L.; supervision, R.C.S.; project administration, L.-M.C., and G.S.; funding acquisition, G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

White truffle - Tuber magnatum pico (a) Fresh ascocarp sample; (b) Thin slices of white truffle.

Figure 1.

White truffle - Tuber magnatum pico (a) Fresh ascocarp sample; (b) Thin slices of white truffle.

Figure 2.

Spherical or oval ascospores 15-20 μm in size. (a) Spherical or oval ascospores of the white truffle species studied; (b) Asci that contain a different number of spores; (c) Clustered ascospores with a thick chitin wall.

Figure 2.

Spherical or oval ascospores 15-20 μm in size. (a) Spherical or oval ascospores of the white truffle species studied; (b) Asci that contain a different number of spores; (c) Clustered ascospores with a thick chitin wall.

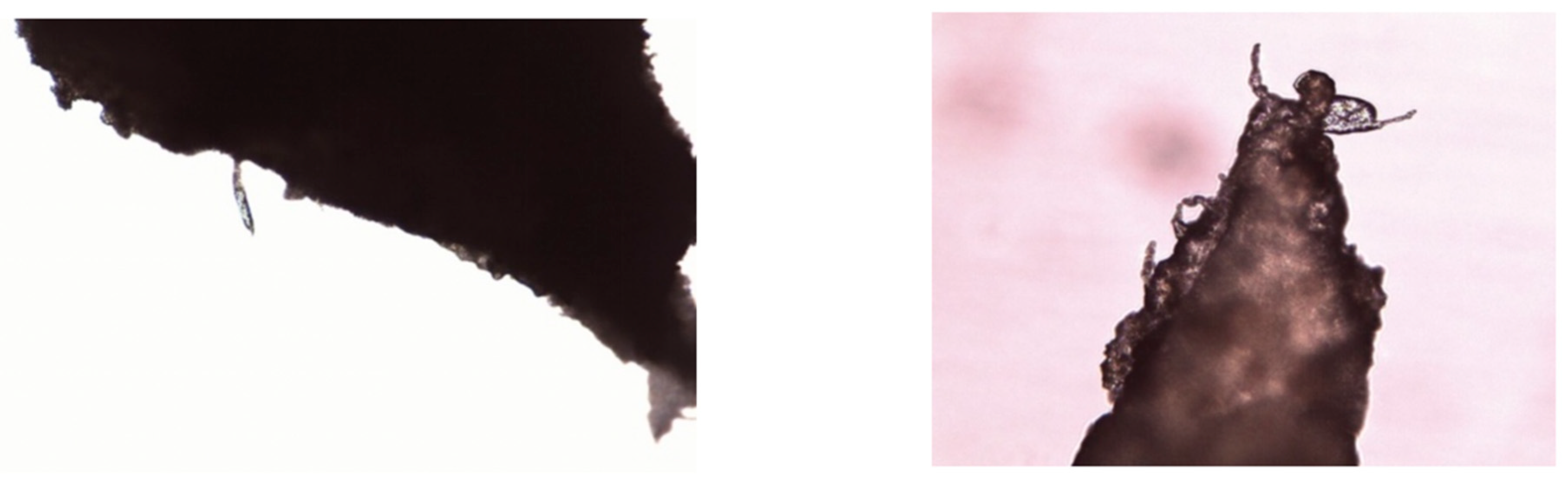

Figure 3.

Microscopic images for white truffles. Expanded rhizoids of Tuber magnatum pico.

Figure 3.

Microscopic images for white truffles. Expanded rhizoids of Tuber magnatum pico.

Figure 4.

Total phenol content of Tuber magnatum pico macerates Asterisks denote statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons among the extraction solvent used (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p<0.05, ns: p > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Total phenol content of Tuber magnatum pico macerates Asterisks denote statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons among the extraction solvent used (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p<0.05, ns: p > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Total flavonoid content of white truffle macerates. Asterisks denote statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons among the extraction solvent used (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01).

Figure 5.

Total flavonoid content of white truffle macerates. Asterisks denote statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons among the extraction solvent used (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01).

Figure 6.

The antioxidant activity of Tuber magnatum macerates. Asterisks denote statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons among the extraction solvent used (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01).

Figure 6.

The antioxidant activity of Tuber magnatum macerates. Asterisks denote statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons among the extraction solvent used (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01).

Figure 7.

Results obtained for ferric reducing antioxidant potency. Asterisks denote statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons among the extraction solvent used (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p<0.05).

Figure 7.

Results obtained for ferric reducing antioxidant potency. Asterisks denote statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons among the extraction solvent used (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p<0.05).

Figure 8.

Spearman correlation heatmap between total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), and antioxidant activity (DPPH, FRAP) in Tuber magnatum macerates. Color scale represents the Pearson correlation coefficient (ρ) ranging from –1 (strong negative correlation) to +1 (strong positive correlation). *** statistically significant at p<0.001.

Figure 8.

Spearman correlation heatmap between total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), and antioxidant activity (DPPH, FRAP) in Tuber magnatum macerates. Color scale represents the Pearson correlation coefficient (ρ) ranging from –1 (strong negative correlation) to +1 (strong positive correlation). *** statistically significant at p<0.001.

Figure 9.

Structures of major constants subject to ADME prediction: gallic acid (1); ergosterol (2); L-arginine (3); linoleic acid (4).

Figure 9.

Structures of major constants subject to ADME prediction: gallic acid (1); ergosterol (2); L-arginine (3); linoleic acid (4).

Figure 10.

BOILLED EGG diagram for gallic acid (1); ergosterol (2); L-arginine (3); linoleic acid (4).

Figure 10.

BOILLED EGG diagram for gallic acid (1); ergosterol (2); L-arginine (3); linoleic acid (4).

Table 1.

Heavy metals in Tuber magnatum pico.

Table 1.

Heavy metals in Tuber magnatum pico.

| Metal |

Concentration

(mg/kg d.w.) ± SD |

LOD (mg/L) |

LOQ (mg/L) |

R2

|

Cd

Cr

Cu

Ni

Mn

Pb |

0.00036 ± 0.00010 |

0.00012 |

0.00040 |

0.9907 |

| 0.00978 ± 0.00200 |

0.00062 |

0.00206 |

0.9925 |

| 0.14410 ± 0.03000 |

0.00093 |

0.00310 |

0.9963 |

| <DL |

0.00044 |

0.00151 |

0.9978 |

| 0.00010 ± 0.00002 |

0.00212 |

0.00708 |

0.9955 |

| <DL |

0.00304 |

0.01002 |

0.9996 |

Table 2.

Concentration of metals (mg/kg d.w.) in dried white truffle product.

Table 2.

Concentration of metals (mg/kg d.w.) in dried white truffle product.

| Metal |

Concentration

(mg/kg d.w.) ± SD |

LOD (mg/L) |

LOQ (mg/L) |

R2

|

Na

Ca

Mg

K

|

2.310 ± 0.053 |

1.1310 |

4.9866 |

0.9952 |

| 17.92 ± 0.726 |

4.3800 |

20.4811 |

0.9941 |

| <DL |

1.0523 |

1.5887 |

0.9967 |

| 11.98 ± 0.271 |

2.0632 |

5.2122 |

0.9987 |

Table 3.

Predicted drug likeness properties for gallic acid (1), ergosterol (2), L-arginine (3), and linoleic acid (4).

Table 3.

Predicted drug likeness properties for gallic acid (1), ergosterol (2), L-arginine (3), and linoleic acid (4).

| Compund |

MW |

logP |

TPSA |

HBA |

HBD |

nrb |

MR |

GI |

BBB |

| 1 |

170.12 |

0.50 |

97.99 |

5 |

4 |

1 |

39.47 |

high |

no |

| 2 |

396.65 |

7.33 |

20.23 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

127.47 |

low |

no |

| 3 |

174.20 |

-1.55 |

127.72 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

44.54 |

low |

no |

| 4 |

280.45 |

5.88 |

37.30 |

2 |

1 |

14 |

89.46 |

low |

no |