1. Introduction

Extended black hole thermodynamics [

1,

2,

3] provides a richer structure of black hole thermodynamics by identifying the cosmological constant

with pressure as

This is possible for the AdS case for which we have

, which implies that

as required on physical grounds. The volume is given as

where

is the volume of unit sphere and

is the horizon radius. This leads to the modified first law with a varying cosmological constant as

is the surface gravity given as (

is the Killing vector)

The modified first law points to the mass of the AdS black hole as being the enthalpy of spacetime [

1]. This has given rise to interesting phenomena concerning black holes, such as Van der Waals fluids [

4,

5], and heat engines [

6].

A varying cosmological constant has been shown to arise from higher-dimensional bulk effects, in which case the varying brane tension

induces extended thermodynamics on the brane [

7]. The modified first law has been shown to arise robustly via the Extended Iyer-Wald formalism in [

8]. In the context of extended phase space, an interesting result is conjectured called the “reverse” isoperimetric inequality (RII) [

3], which is formally defined as

where

V is the thermodynamic volume

1,

is the volume of unit sphere and

A is the area of the outer horizon. Equivalently, the inequality can be stated as AdS-Schwarzschild black holes at a fixed

geometric volume

maximize area or entropy [

3]. This means that

a round-sphere (static and uncharged) of fixed geometric volume in (A)dS space maximize area or entropy. It is precisely this statement that we will prove.

The inequality is reversed in the sense that in Euclidean space, a round sphere minimizes area, called simply the isoperimetric inequality [

9,

10]. The reverse isoperimetric inequality is known to be obeyed for every case except for the Bañados-Teitelboim-Zanelli (BTZ) black holes [

11]. Black holes that violate RII are called superentropic [

12,

13]. However, these are thermodynamically unstable [

14] since they have negative heat capacity at constant volume. RII is a classical result, and some quantum inequalities have also been proposed recently regarding this [

15]. Despite the success of RII, it lacks a general proof and remains a conjecture.

In this letter, we provide for the first time a two-pronged proof of RII using a geometric and analytical approach. The proof is briefly organized as follows: In (

Section 2.1), we argue in favor of RII purely on geometric grounds. In (

Section 2.2), an analytical approach using the second variation of the area is provided. We end the paper with some discussion. Three appendices (

Appendix A,

Appendix B and

Appendix C) are included to further elaborate on our proof.

2. (A)dS-Schwarzschild Black Holes Maximize Entropy

To begin with, we perform a 1+1+2 split [

16] of spacetime

of dimension

and apply a proper (non-constant) conformal transformation to the metric of the

-hypersurface

of

Here,

are the angular coordinates, so that the spherical symmetry is broken. For example, one can have

which explicitly breaks the

symmetry. In the 1+1+2 decomposition of the spacetime

, the 3-space orthogonal to the timelike unit vector

is further split into a preferred spacelike direction

and its orthogonal 2-space (or “2-sheet”). One introduces the projection tensors [

17]

so that

,

, and

. Working on a fixed background (here, Anti-de Sitter) so that

is held fixed by Einstein’s equations, we vary only the intrinsic 3-metric (or induced metric)

via a (proper) conformal transformation. Spatial indices are then raised and lowered with

. This point can be understood as follows: Although the induced metric and bulk metric are related by

we hold the bulk metric fixed,

and vary only the hypersurface embedding (or its conformal factor). Concretely, deforming the embedding as

induces a change in the induced metric via

even though

. Therefore,

Thus, we achieve a non-trivial variation of the induced metric while keeping the ambient Ricci tensor fixed by Einstein’s equations.

In addition, we choose to break the spherical symmetry via conformal transformation so that the topology of the hypersurface is preserved while breaking the spherical symmetry in a controlled way. We now argue in favor of the round 3-sphere in maximizing area or entropy purely on geometric grounds.

2.1. Sherif-Dunsby Rigidity and Maximal Entropy

Consider a compact 3-manifold

of spherical topology in the 1+1+2 decomposition of spacetime

. We consider an arbitrary one-parameter family of volume-preserving normal deformations

,

, with induced metrics

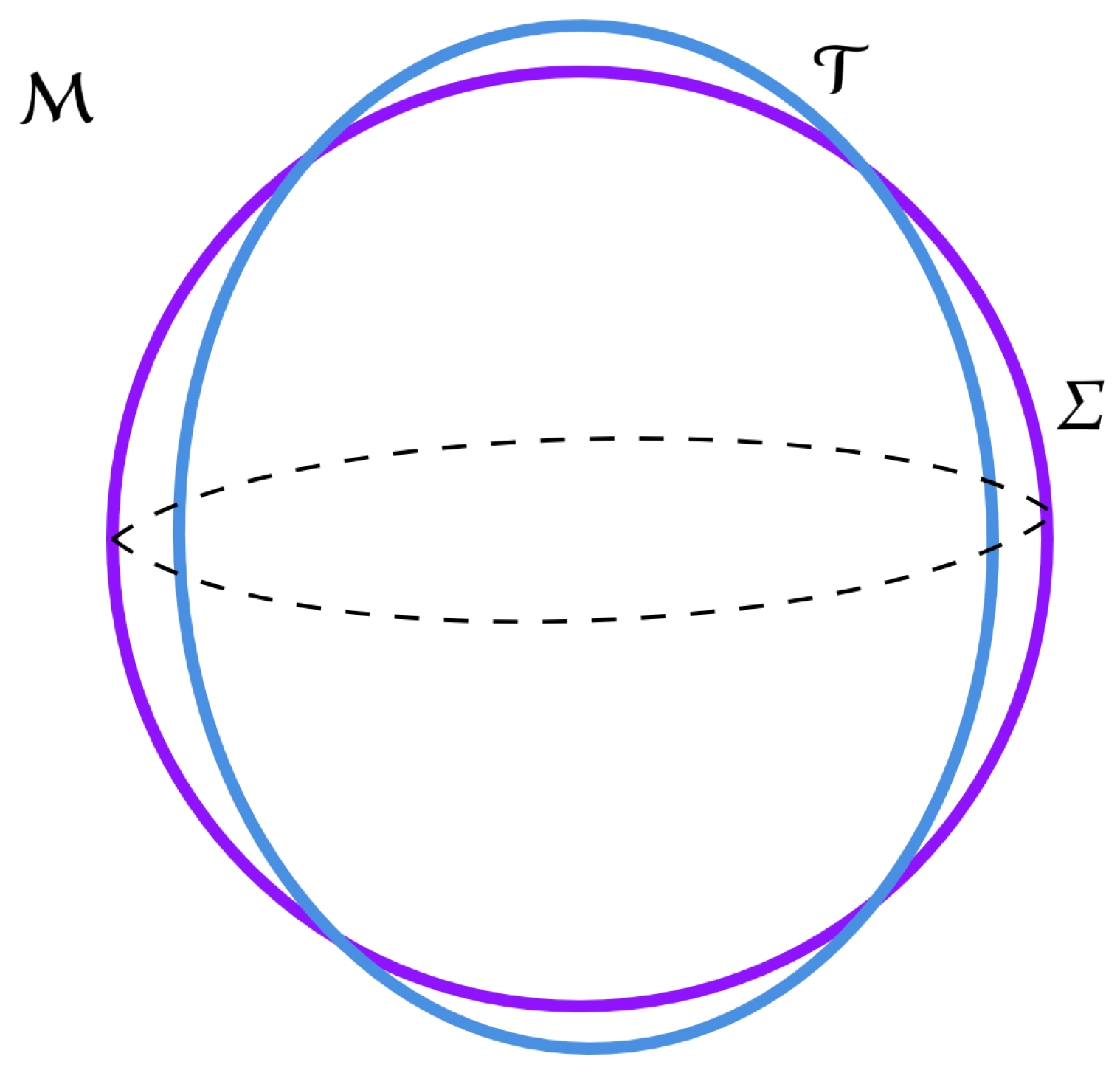

Let us represent the deformed 3-sphere (non-Einstein) with

(see

Figure 1). Then on

:

Note that we are using two different expressions of conformal factors:

is the proper conformal factor by which we deform the round 3-sphere. This is not sign-definite. In fact, under volume preservation

and it takes both positive and negative values.

is the Yamabe factor by which we study the Yamabe problem on the deformed 3-sphere

. This has a strictly negative sign via gravitational focusing

2. The discussion leads to an interesting geometrical implication:

any non-homothetic, volume-preserving conformal deformation of a compact 3-sphere under the gravitational focusing forces it to be isometric to round 3-sphere. So, the only admissible extremal is the round

.

To further investigate the extremality, consider a dS saddle of fixed volume in

(saddle topology is

). The saddle action under volume constraints in 1+1+2 decomposition gives (see

Appendix B)

where

A is the area of 2-sheet. Therefore, extremality of

(the spatial hypersurface of dS saddle) establishes it as the maximally entropic state

3. Conversely, the round dS saddle in

D-dimension has minimal action

[

18]. This follows from Bishop comparison theorem [

19]. Therefore, the surface has maximal entropy or area (this follows from (

8)). We thus conclude that

a round 3-sphere maximizes entropy (or area) under gravity. This is in stark contrast to the Euclidean isoperimetric case, where no such curvature-driven rigidity exists due to the absence of gravity.

Bolt-to-Horizon Identification

By Sherif–Dunsby rigidity the compact Euclidean slice

is isometric to the round 3-sphere. Introducing standard “latitude” coordinate

,

each

hypersurface is a round

of radius

. In particular the Euclidean “bolt” at

is the unique maximal-area 2-sphere leaf under fixed enclosed 3-volume. Under the Wick rotation back to Lorentzian signature this bolt maps exactly to the event-horizon cross-section (the

sphere) of the black hole. Hence maximality of the full

immediately implies maximality of the horizon

.

After the geometric argument, we now turn towards the area variation method to analytically establish this result.

2.2. Effective Functional and Its Variation

We begin with the Euclidean Einstein–Hilbert action plus Gibbons–Hawking boundary term in

D dimension

On an Einstein solution

we have

, so under a normal deformation

the bulk term varies as

while the Gibbons–Hawking term contributes

where

A is the area of

-sphere. Collecting these values leads to

We first calculate the first variation. Using

4

where

H is the mean curvature (trace of second fundamental form). The stationarity of

implies

For the second variation of a Riemann hypersurface, we have the standard expression

where

is the squared norm of the gradient operator,

is the ambient manifold Ricci tensor and

is the second fundamental form. Thus, we get

In an Einstein background

. Therefore, on a round 3-sphere of radius

R in an Euclidean AdS space, we obtain

Therefore, for

(quadrupole) modes, which are volume preserving, true shape deformations of the Laplace-Beltrami spectrum (see

Appendix C), we get

This shows that the round

in an AdS space is a

local maximum of area since

. Interestingly, the above remains true for a dS space, showing that dS black holes also obey a reverse isoperimetric inequality as advocated in [

21]. In Euclidean space, Ricci scalar vanishes, and we have

Therefore, for the volume preserving, true shape deforming modes

This means that a round 3-sphere in Euclidean space is a local minimum of area, which is the standard isoperimetric inequality in Euclidean spaces. This shows that the reversal of the isoperimetric inequality is due to the structure of spacetime governed by Einstein’s field equation in a curved background.

It is worth mentioning that in the case of horizons, the area is identified with entropy. Therefore, maximizing area (or entropy) leads to stability, unlike the Euclidean isoperimetric inequality, where minimizing area is related to stability. Although we derived the result for Euclidean (A)dS space in

, the analysis applies directly to Euclidean (A)dS space in

D-dimension since all the results (gravitational focusing, Sherif-Dunsby rigidity, and second area variation) continue to hold. Therefore, the conclusion naturally extends to any dimension. The extension of the Sherif-Dunsby result can be better understood as follows. Because Obata’s theorem [

22] holds on any compact

n-manifold (

), we may replace the 3D Yamabe rigidity of Sherif–Dunsby by its

n-dimensional analogue. Concretely, on a

D-dimensional spacetime we perform a

decomposition and identify the infinitesimal conformal factor with expansion of

sheet,

. Then, via gravitational focusing, we have

everywhere, and Obata’s theorem then forces the deformed metric to be isometric (up to scale) to the round

. Hence, the only volume-preserving extremum of the entropy functional is the round sphere in any dimension.

At this point, it is necessary to analyze another spherically symmetric geometry, the charged (Reissner-Nordström) black hole. It is straightforward to evaluate that adding a charge

Q modifies the saddle action as

where

is the electrostatic potential. The term corresponding to the charge

Q appears due to the addition of Maxwell’s action to the Einstein-Hilbert action

Evidently, this means that a charged black hole has less entropy than its uncharged counterpart. This leads us to conclude the main result of our Letter: Round, uncharged black holes in (A)dS space, i.e., (A)dS-Schwarzschild black holes in any dimension maximize entropy (or horizon area).

3. Conclusions and Discussion

In this work, we have established a rigorous geometric–analytic proof of the reverse isoperimetric inequality (RII) for black hole horizons in (A)dS space of arbitrary dimension. On the one hand, the geometric argument based on a decomposition, Raychaudhuri focusing, and the Sherif–Dunsby (or Obata) rigidity theorem shows that any nontrivial, volume-preserving conformal deformation of a compact spherical hypersurface is forced back to the round by gravitational focusing alone. On the other hand, the analytic approach—via the second variation of the Euclidean gravitational action plus Gibbons–Hawking–York boundary term—demonstrates that quadrupolar () perturbations of the round sphere yield in Euclidean (A)dS (but in flat Euclidean space), confirming that the round (A)dS-Schwarzschild horizon is a local maximum of area (entropy) under volume constraints.

Together, these complementary arguments show that, in contrast to the classical isoperimetric inequality in flat space, gravity in a curved background reverses the inequality: among all hypersurfaces of fixed thermodynamic volume, the uncharged, spherical (A)dS-Schwarzschild black hole uniquely maximizes horizon area. This result not only resolves the long-standing conjecture of RII in extended black hole thermodynamics but also highlights the fundamental role of Einstein’s equations and background curvature in governing entropic extremization.

Several avenues for further investigation naturally arise from our proof:

Charged and Rotating Solutions: Although we have shown that electric charge reduces the saddle action via the additional Maxwell term, a full treatment of RII for charged (Reissner–Nordström) and rotating (Kerr–AdS) black holes—including off-shell stability analysis—would elucidate possible extensions or violations in these more general settings.

Quantum Corrections: Incorporating higher-curvature corrections or quantum effects (e.g., via one-loop determinants or entanglement entropy corrections) may modify the geometric rigidity or the second variation functional, potentially leading to refined ‘‘quantum RII’’ bounds.

Holographic Perspectives: Given the AdS/CFT correspondence, it would be interesting to interpret our RII proof in the dual field theory, perhaps relating maximal horizon entropy at fixed volume to extremal entanglement or energy constraints in the boundary CFT.

Beyond Asymptotic (A)dS: Extending the analysis to asymptotically flat or more exotic asymptotics (e.g., Lifshitz, hyperscaling violation) might reveal whether the reverse isoperimetric phenomenon is unique to constant- backgrounds or has broader applicability.

Violation in the case of superentropic black holes: It is known that superentropic black holes violate RII. As part of the proof we presented, this can be traced to their non-compact hypersurface while the proof requires a compact hypersurface. Nevertheless, a general proof explicitly for non-compact hypersurfaces is an interesting future work.

In summary, our geometric–analytic approach not only proves the reverse isoperimetric conjecture in its full generality but also underscores the deep interplay between curvature, gravitational focusing, and entropy extremization. We anticipate that these insights will inform future studies of black hole thermodynamics, geometric inequalities in curved manifolds, and the fundamental connections between geometry and information in gravitational systems.

Appendix A. Conformal Rigidity and Sphericity of Compact Hypersurfaces

In this appendix, we recall and explain the key geometric result (Theorem VII.4 of Sherif–Dunsby [

17]) that underpins the identification of the unique extremal slice in our proof of the Reverse Isoperimetric Inequality. We then show how it applies to the class of hypersurfaces considered in this work.

Appendix A.1. Statement of the Theorem

Theorem A1 (Sherif–Dunsby, [

17], Theorem VII.4).

Let be a spacetime admitting a covariant split, and let be a compact, smoothly embedded spacelike hypersurface whose induced metric h has Ricci tensor of the form

where is the unit “radial” direction and N is the projector onto the remaining 2–sheet. Suppose T admits a proper

conformal transformation

with associated conformal factor , and that

and the sheet–expansion scalar ϕ of T is nowhere zero. Then is isometric to the round 3–sphere .

Here, primes denote covariant derivatives along the sheet direction .

Appendix A.2. Role in the Reverse Isoperimetric Proof

In (

Section 2.2) of the main text, we similarly assume that the deformed horizon slice

:

is compact,

admits a nontrivial conformal deformation preserving scalar curvature (this can always be ensured for a choice of conformal factor ),

scalar curvature is positive (this is always the case for and, is therefore, naturally satisfied),

along with the Raychaudhuri equation, which guarantees a negative sheet expansion under gravitational focusing (equivalently, negative conformal factor in the 1+1+2 decomposition of spacetime), so that each hypothesis of Theorem VII.4 is met. By this theorem, the only possibility is that ) is a round 3–sphere.

Together with the analytic variation argument (

Section 2.2), this geometric rigidity completes the proof that among all fixed–volume slices, the spherical black hole horizon uniquely maximizes the area.

Appendix B. Saddle Action in 1+1+2 Decomposition of Spacetime

We derive the saddle action for the simplest case

in a 1+1+2 split of spacetime and show that it reproduces the standard result in the

D-dimension [

18]. The Euclidean saddle metric in the 1+1+2 split is

Here, the coordinates

span the base 1+1 geometry. The coordinate

is the Euclidean time taken to be periodic with period

so that there is no conical singularity at the Euclidean horizon.

is the metric on the unit 2-sphere (the “2” of the 1+1+2 split). A fixed volume constraint determines the size of the ball so that the Euclidean horizon is at

. Regularity at

fixes the lapse function to be (for

saddle,

)

Now, the saddle action in 1+1+2 spherical decomposition (for a static and spherically symmetric metric) is

Note that for a static spacetime, the extrinsic curvature tensor

and its trace

K vanish. Therefore, only the 2D decomposition of the 4D Ricci scalar appears in the above equation. Since

and

is a total derivative term, we can write (after performing

and

integration)

The total derivative term

is cancelled by the Gibbons-Hawking-York boundary term

(see

Appendix B). The “1+1”-base metric is the

-subspace given as

This means that the 2D Ricci scalar is given as

Putting the integrand together, the bulk action becomes

Since

, we get the saddle action as

which is the same as that obtained in the

D-dimension.

Cancellation of the Bulk-Boundary Term via GHY Boundary Term

The term

can be written as

where

is the unit normal to the boundary, and

is the induced line element on the 1D boundary of the 2D base. The full 4D Gibbons-Hawking-York (GHY) boundary term is given as

where

is the induced metic on the 3D boundary and

K is the trace of the extrinsic curvature. In 1+1+2 spherical reduction, the extrinsic curvature decomposes as

where

is the extrinsic curvature of the boundary in the 2D base. Thus, the GHY boundary term becomes

The second term cancels the boundary term arising from the bulk. The first term is there to ensure a well-posed variational problem. However, in the limit, the York boundary is set to zero, the first term vanishes, and we only have contributions from the bulk.

Appendix C. Spectrum of Metric Perturbations on the Round 3-Sphere

In this appendix we summarize why only the quadrupole () modes yield nontrivial, source-free metric perturbations on , and why the deformations are excluded.

Appendix C.1. Transverse–Traceless Gauge and Lichnerowicz Operator

Let

be the round metric on

of radius

R, satisfying

Consider a small perturbation

imposed in

transverse–traceless (TT) gauge:

The linearized, source-free Einstein equation on an Einstein manifold

reads

where

Appendix C.2. Tensor Harmonic Spectrum on S 3

One can expand TT–tensors in tensor spherical harmonics

labeled by

, which satisfy

Inserting into the linearized equation gives the eigenvalue condition

Hence the only nontrivial solution of in TT gauge on is the quadrupole mode .

Appendix C.3. Exclusion of ℓ=0,1 Modes

(monopole): A constant rescaling

changes the volume rather than shape; in TT gauge

forbids such a trace mode.

(dipole): These correspond to infinitesimal diffeomorphisms (Killing vectors) on

,

which can be entirely removed by a coordinate redefinition. In TT gauge one requires

, and one finds no non-gauge

TT tensors.

Therefore, when restricting to physical, source-free metric perturbations of the round , only the harmonics survive, justifying the truncation to the quadrupole sector in the main text.

References

- Kastor, D.; Ray, S.; Traschen, J. Enthalpy and the Mechanics of AdS Black Holes. Class. Quant. Grav. 2009, 26, 195011. [CrossRef]

- Dolan, B.P. The cosmological constant and the black hole equation of state. Class. Quant. Grav. 2011, 28, 125020. [CrossRef]

- Cvetic, M.; Gibbons, G.W.; Kubiznak, D.; Pope, C.N. Black Hole Enthalpy and an Entropy Inequality for the Thermodynamic Volume. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 84, 024037. [CrossRef]

- Chamblin, A.; Emparan, R.; Johnson, C.V.; Myers, R.C. Charged AdS black holes and catastrophic holography. Phys. Rev. D 1999, 60, 064018. [CrossRef]

- Kubiznak, D.; Mann, R.B. P-V criticality of charged AdS black holes. JHEP 2012, 07, 033. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.V. Holographic Heat Engines. Class. Quant. Grav. 2014, 31, 205002. [CrossRef]

- Frassino, A.M.; Pedraza, J.F.; Svesko, A.; Visser, M.R. Higher-Dimensional Origin of Extended Black Hole Thermodynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 161501. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.X. Extended Black Hole Thermodynamics from Extended Iyer-Wald Formalism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 021401. [CrossRef]

- Osserman, R. Isoperimetric and related inequalities. In Proceedings of the Proc. Symp. Pure Math, 1975, Vol. 27, pp. 207–215.

- Osserman, R. The isoperimetric inequality. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 1978, 84, 1182–1238.

- Martinez, C.; Teitelboim, C.; Zanelli, J. Charged rotating black hole in three space-time dimensions. Phys. Rev. D 2000, 61, 104013. [CrossRef]

- Hennigar, R.A.; Mann, R.B.; Tjoa, E. Super-Entropic Black Holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 031101. [CrossRef]

- Hennigar, R.A.; Kubizňák, D.; Mann, R.B.; Musoke, N. Ultraspinning limits and super-entropic black holes. JHEP 2015, 06, 096. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.V. Instability of super-entropic black holes in extended thermodynamics. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 2020, 35, 2050098. [CrossRef]

- Frassino, A.M.; Hennigar, R.A.; Pedraza, J.F.; Svesko, A. Quantum Inequalities for Quantum Black Holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 133, 181501. [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, C. A Covariant approach for perturbations of rotationally symmetric spacetimes. Phys. Rev. D 2007, 76, 104034. [CrossRef]

- Sherif, A.M.; Dunsby, P.K.S. Conformal geometry on a class of embedded hypersurfaces in spacetimes. Class. Quant. Grav. 2022, 39, 045004. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, T.; Visser, M.R. Partition Function for a Volume of Space. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 221501. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, R.L. A relation between volume, mean curvature and diameter. In Euclidean Quantum Gravity; World Scientific, 1964; pp. 161–161.

- O’neill, B. Semi-Riemannian geometry with applications to relativity; Vol. 103, Academic press, 1983.

- Dolan, B.P.; Kastor, D.; Kubiznak, D.; Mann, R.B.; Traschen, J. Thermodynamic Volumes and Isoperimetric Inequalities for de Sitter Black Holes. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 87, 104017. [CrossRef]

- Obata, M. Certain conditions for a Riemannian manifold to be isometric with a sphere. Journal of the Mathematical Society of Japan 1962, 14, 333–340.

| 1 |

The definition of thermodynamic volume requires a cosmological constant or a gauge coupling. (A)dS black holes are naturally equipped with this. |

| 2 |

Since we now study the natural state of deformed 3-sphere under gravity. |

| 3 |

This is because gravity drives a deformed 3-sphere back to round 3-sphere establishing it as a stable state. Since stability in the context of thermodynamics is tied with maximal entropy, the conclusion naturally follows. |

| 4 |

The explicit equations for area and volume variations can be found in [ 20]. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).