1. Introduction

In the framework of general relativity (GR), black holes arise as fundamental solutions to Einstein’s field equations. However, the classical description of these objects becomes inadequate at the Planck scale, where quantum gravitational effects are expected to dominate. A common aspect of several quantum gravity candidates, including string theory and matrix models, is the emergence of a

minimal length scale. Although many approaches, such as string theory and loop quantum gravity, have made progress in describing quantum aspects of spacetime, there is currently no conclusive theory of quantum gravity, which motivates the study of non–commutative (NC) spacetimes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] as a candidate with geometrical approach. NC geometry introduces a deformation of the spacetime manifold through noncommuting coordinates, typically written as

where

is a constant antisymmetric matrix that characterizes the spacetime deformation. This deformation yields a fundamental length scale below which the classical concept of spacetime continuity ceases to apply. Such ideas emerge naturally from string theory, matrix models, making NC geometry a compelling framework for encoding Planck–scale corrections [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Various approaches have been presented to include NC adjustments into gravity, including the smearing of matter sources [

10,

11,

12,

13], use of the Moyal star product [

14], and more systematically, the application of the Seiberg–Witten (SW) map [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. The SW map provides the expansion of NC fields in terms of their commutative counterparts, ensuring gauge covariance and offering a controlled framework for embedding NC effects into gravitational systems. This approach has been vastly applied in the investigation of black hole physics in NC spacetime in recent years [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. NC black holes have been shown to regularize curvature singularities [

10,

11], modify thermodynamic characteristics including the Hawking temperature and entropy [

12,

29,

30,

31,

32], and yield potentially observable signatures in gravitational wave signals and shadow profiles [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

In this work, we follow the NC modifications of black hole solutions introduced in Ref. [

38] and investigate the imprint of the NC framework on a charged black hole. We introduce a Moyal–type twist in the

coordinate sector and construct a consistent NC-deformed metric by applying the Seiberg–Witten map to the vierbein fields. Second-order corrections to the spin connection are included to ensure consistency up to

, which captures subtle quantum corrections.

Our analysis spans several interconnected aspects of NC black hole physics. We start by examining the thermodynamic characteristics of the NC-Reissnerr Nordstroöm black hole, including the modification of the Hawking temperature. We also explore quantum tunneling of both bosonic and fermionic particle modes, revealing deformation–induced shifts in the radiation spectrum. A major challenge in this context is the computation of quasinormal modes (QNMs), which express the black hole’s response to external perturbations. In NC spacetimes, the equation for scalar perturbations becomes highly nontrivial due to the complex form of the metric functions. We address this by deriving a Schrödinger–like master equation through a novel numerical solution via perturbation method [

33,

34,

35] and compute QNMs, using the WKB approximation. Moreover, we investigate the structure of the

photon sphere, which governs key observational features such as black hole shadows. The stability of the photonic sphere is explored via both curvature and topological approaches. We compute the shadow radius and the deflection angles in the NC geometry and compare our predictions of the lensing observables with Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) observations of

and

. These comparisons allow us to check the probable constraints on the NC deformation parameter

, thereby assessing the observational viability of NC gravity models.

In summary, this work presents a comprehensive investigation of a charged black hole in a non–commutative spacetime. By connecting theoretical predictions with observational data, we aim to bridge the gap between quantum gravity models and astrophysical measurements, providing potential empirical opportunities to explore the physics of spacetime at the smallest scale.

2. Non–Commutative Charged Black Hole

The non–commutativitive (NC) spacetime is introduced through the fundamental commutation relation in Equation (

1). Following the methodology outlined in Ref. [

38], we derive the non-commutative corrections to the Reissner–Nordström metric, with further details available therein. The Moyal twist element is defined as

which induces the star product between functions

The gauge transformation in the NC framework becomes

where the star commutator is

Following Seiberg–Witten map, the next expansion for the deformed tetrad fields is provided

with

and the spin connection fields are expressed as

with

and

Utilizing the NC tetrad fields

introduced in [

19], deformed NC metric is proposed as

Now, the NC gauge transformation obeying counterpart

results in the construction of the NC black hole metric.

As mentioned before, this approach has been extensively employed in the literature to examine the phenomenology of spacetime within the NC spacetime [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

39]. However, [

38] proposed that a correction term be applied to (8), which makes the whole prior investigation revisited.

We present the metric for the Reissner–Nordström black hole in the Moyal twist. We correct prior errors–specifically addressing the overlooked term in Equation (8)–and introduce new, previously unexplored analyses for this significant NC metric.

The twist in the

plane is non–Killing and is characterized by the tensor

.

With this choice, the coordinates satisfy the commutation relation

Although this twist has been investigated in the literatures [

19,

21,

40], we revisit it here for Reissner–Nordström considering the newly identified terms in (8), with unexplored aspects of a charged black hole in this framework. Based upon this twist, the non-zero elements of the tetrad

include as following

here

represent the first, second, and third derivatives of

, respectively. The deformed metric

is obtained by using the definition in Equation (

12). The resulting metric is diagonal, and the non–zero components, up to the second order of

, are

The NC-corrected Reisser–Nordström metric components under the

twist are obtained by substituting the Reissner–Nordström black hole function

into Equation (16),

3. Thermodynamics

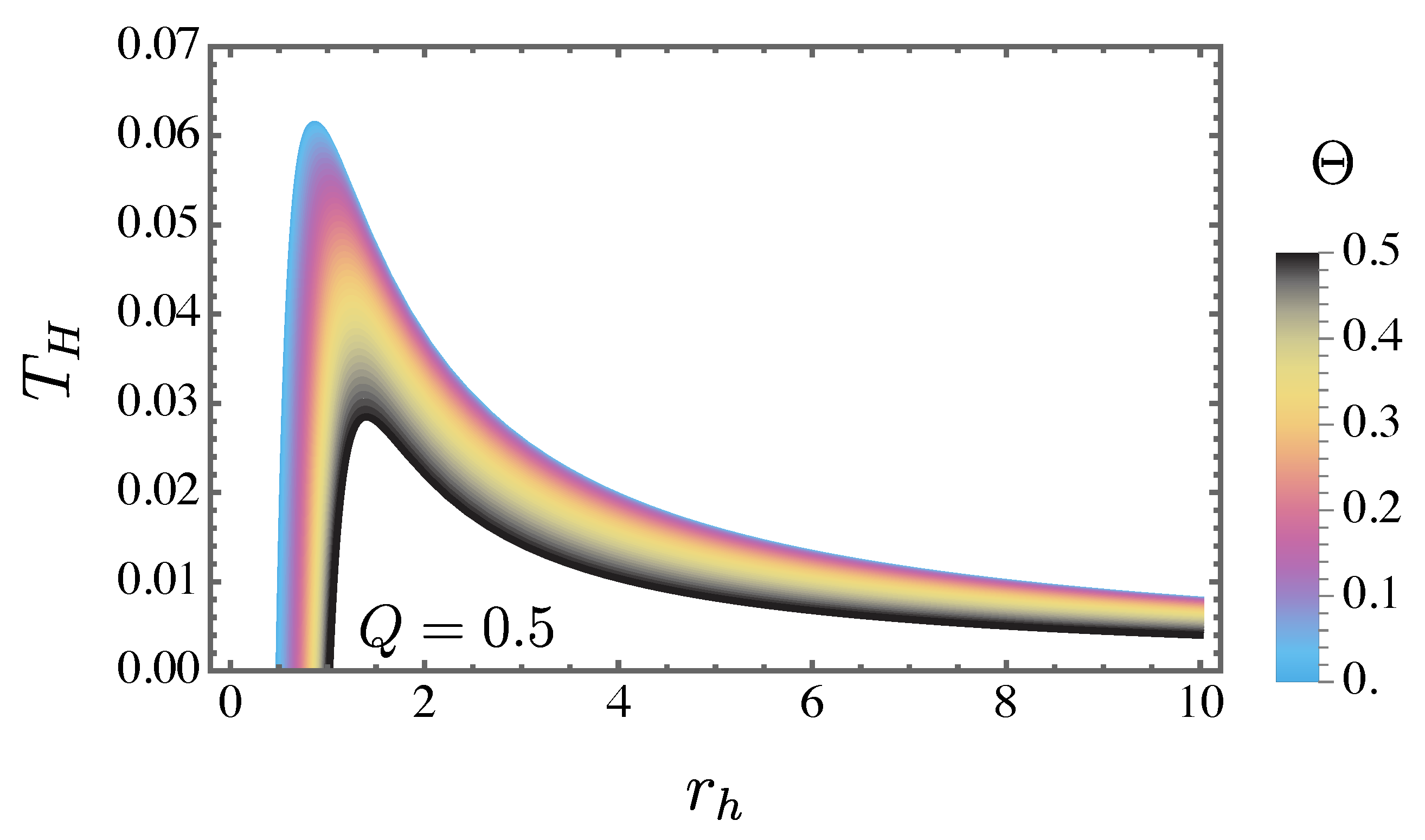

We start our analysis of the above spacetime by turning our attention to the thermodynamic aspects of the Reisser–Nordström black hole within the non–commutative gauge theory. Specifically, we examine the behavior of the Hawking temperature, entropy, and heat capacity. We will express all thermodynamic properties as functions of the event horizon radius , as it is a standard procedure in the literature. In particular, special emphasis will be placed on the Hawking temperature, which will also be studied as a function of the black hole mass M to assess the possible existence of a remnant mass.

3.1. Hawking Temperature

This section will be devoted to investigating the Hawking temperature. Using the surface gravity procedure which reads [

41,

42,

43,

43]

where

and considering small values for

and

Q, it turns out to be

It is clear that when

goes to zero, the Hawking temperature recovers the Reissner–Nordström black hole. In the next step, we show the Hawking temperature as a function of the event horizon. To do so, we consider the solution of the mass coming from

, which leads to

It is worth to notice that the horizon radius keeps the same as the commutative model of the Reissner–Nordström black hole. Therefore, after substituting mass from Equation (25) in Equation (24), we obtain

In

Figure 1, the behavior of the Hawking temperature concerning the event horizon radius

is depicted for several values of

, assuming fixed values

. It is evident that increasing the NC parameter results in a reduction in the Hawking temperature for this specific configuration.

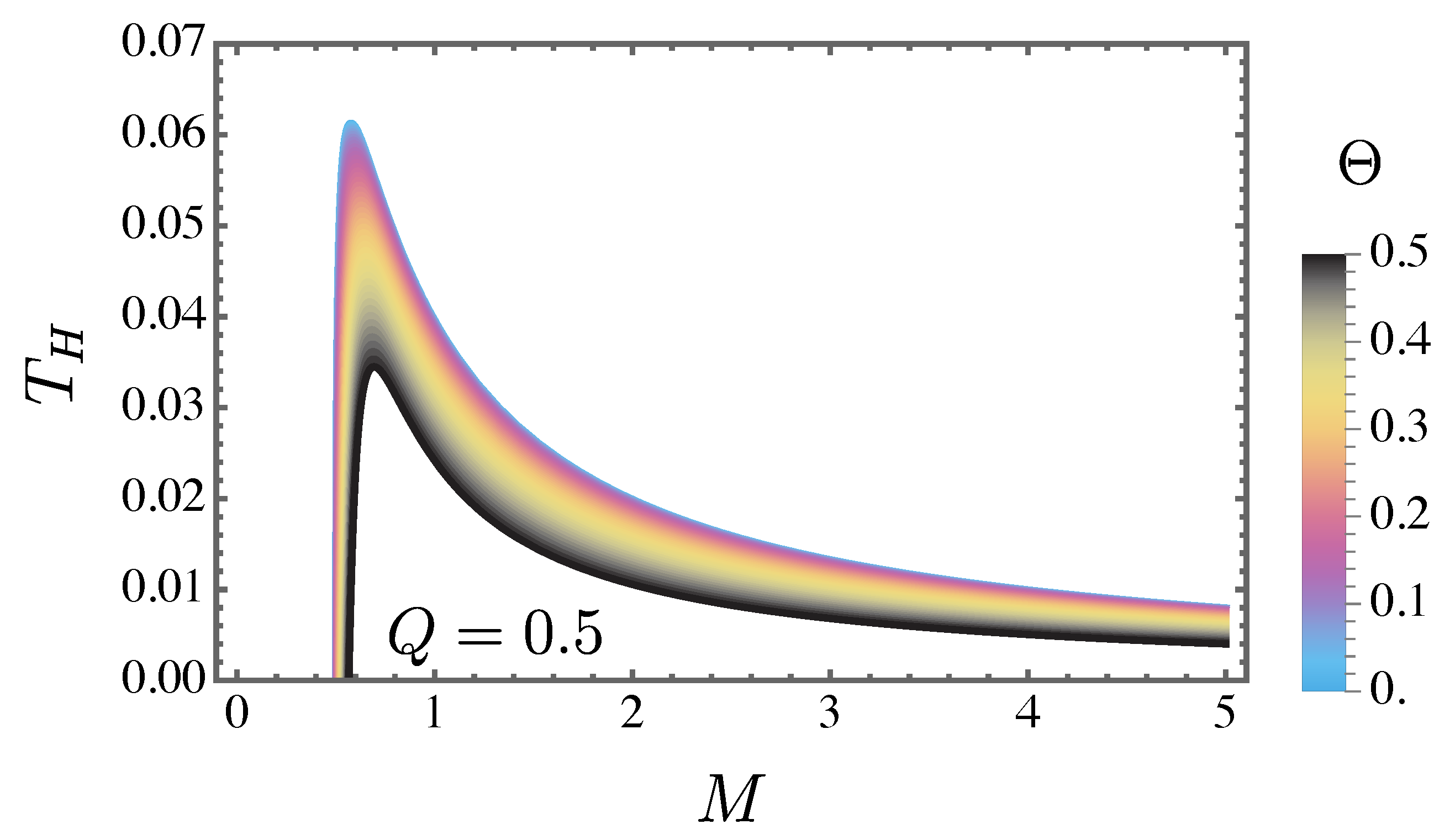

In addition, it would be important to investigate this thermal quantity concerning the mass

M. Using the expression of the event horizon present in Equation (25) and substituting it in the Hawking temperature expression in Equation (26), leads to

Figure 2 depict the Hawking temperature concerning the mass and the existence of remnant masses becomes apparent, as the Hawking temperature tends to zero while the mass remains finite, i.e.,

as

. To determine an explicit expression for the remnant mass

, we consider Equation (27) in the regime of small

and

Q, which yields the following approximation

In other words, the above expression indicates that the black hole does not undergo complete evaporation; instead, it leaves behind a nonzero remnant mass, .

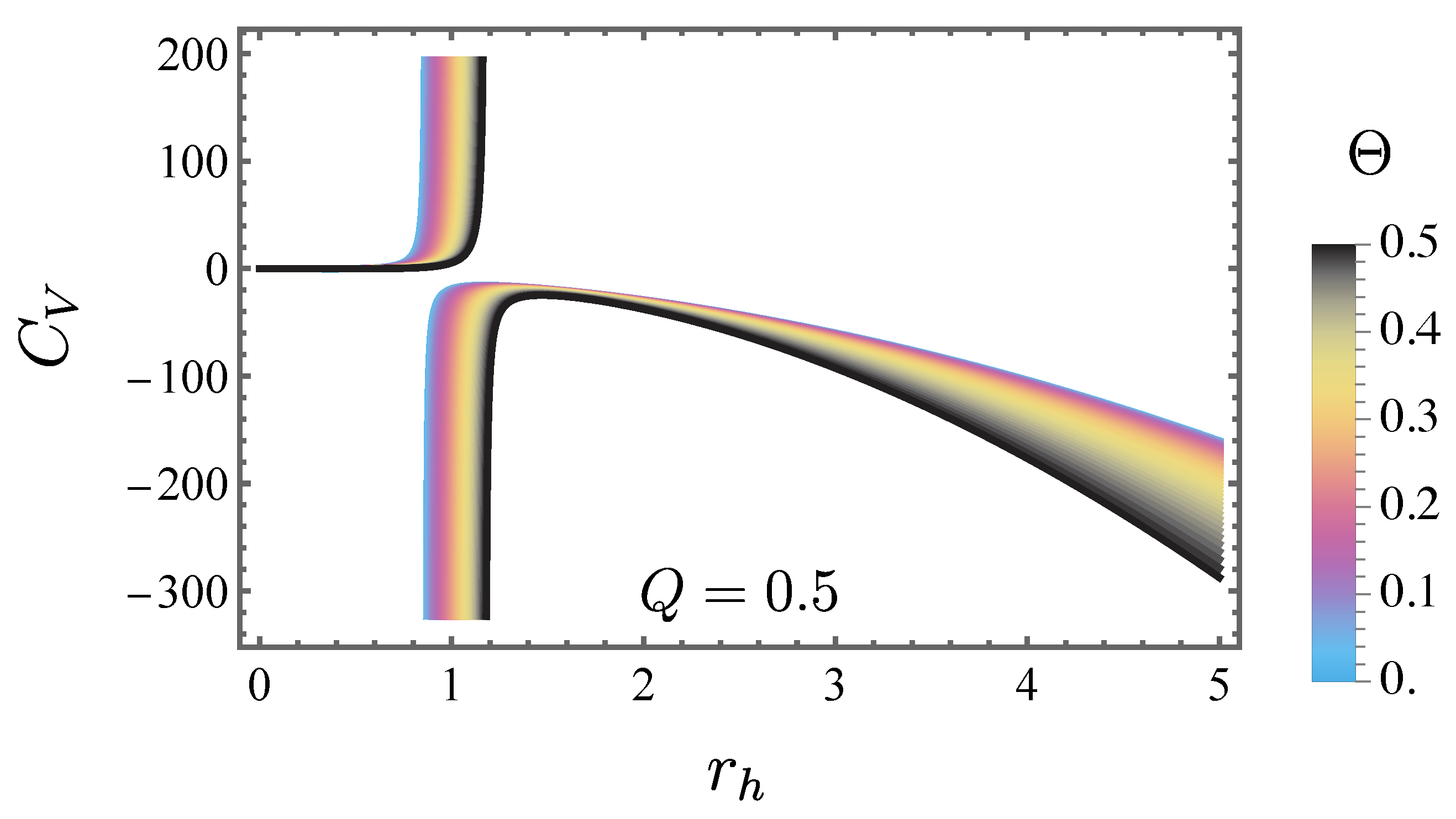

3.2. Heat Capacity

In this section, we conclude our analysis by examining the behavior of the heat capacity

In

Figure 3, the heat capacity

is displayed as a function of the event horizon radius

for different values of the charge

Q, with the parameters fixed at

. This plot highlights the occurrence of phase transitions, as well as the regions where

assumes positive or negative values.

4. Hawking Radiation

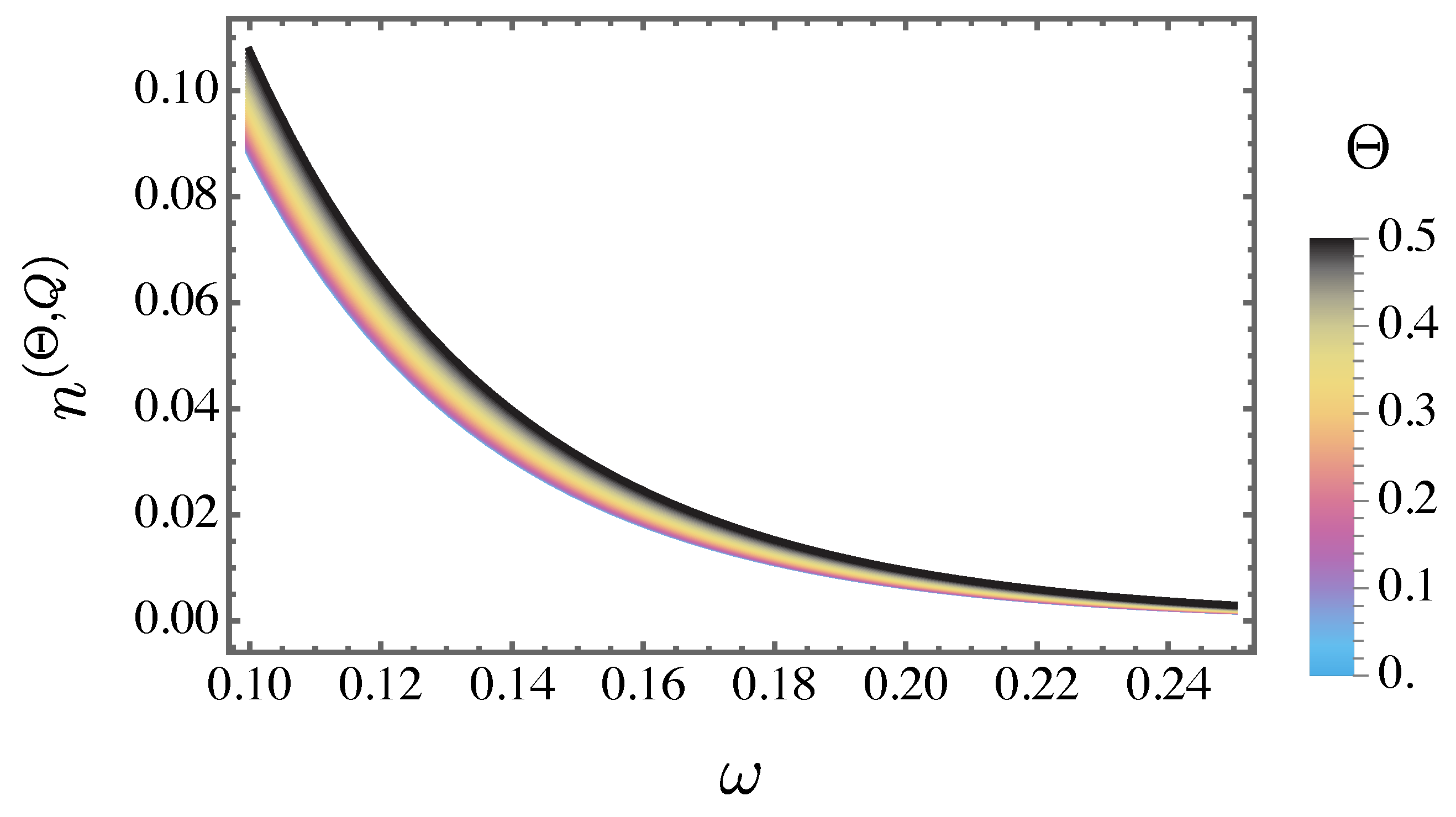

In this section, we develop the earlier examination, which confirmed the thermal emission of the black hole via the Hawking temperature, to explore the quantum radiation itself. We focus on both bosonic and fermionic particle modes. To derive analytical expressions, we adopt the same angular components as in the Reissner–Nordström metric. The corresponding particle creation densities are calculated for each case, enabling a comparative analysis of the emission rates. As will be shown, for a given frequency , the emission of bosons surpasses that of fermions.

4.1. Bosons

To conduct our analysis, we examine the following metric tensor configuration

Under the Hamilton–Jacobi approach, the equation characterizing the radial motion of a massless particle takes the form [

44,

45,

46]

As demonstrated in the following analysis, the classical action admits a representation in which the positive and negative signs correspond to outgoing and ingoing particles, respectively.

Here,

corresponds to the Killing energy. Through near-horizon expansion, we obtain

and utilizing Feynman’s method, we arrive at

where

is, therefore, the so–called surface gravity. If we consider

small, we obtain

By defining

From this analysis, we derive the fermionic particle creation density

n explicitly as

where

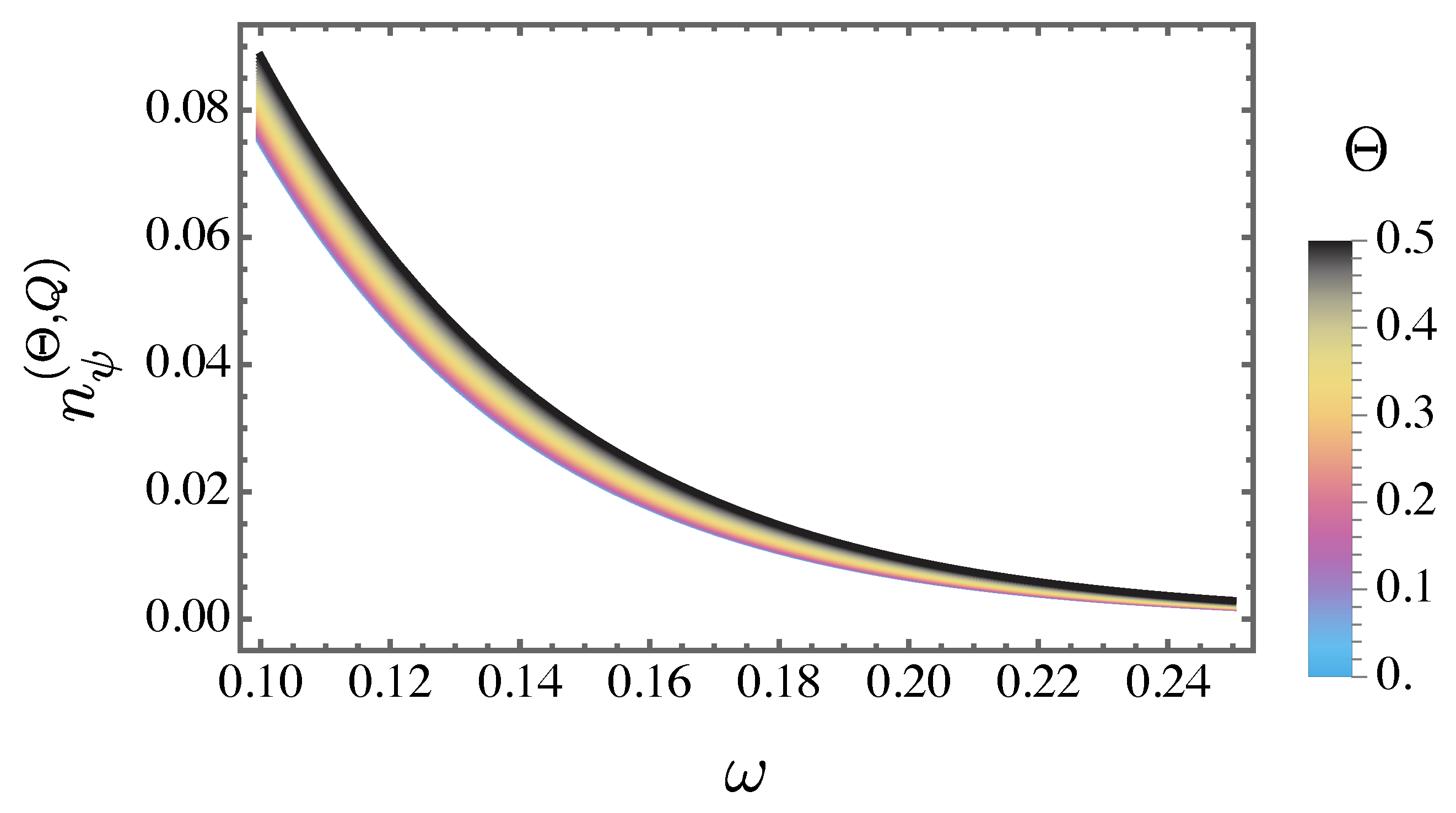

Figure 4 displays the particle creation density

as a function of the frequency

, with fixed parameters

and

, while varying the values of

. Overall, the magnitude of

increases with larger values of

.

4.2. Fermions

It is important to emphasize that the subsequent calculations are performed under the assumption that backreaction effects are neglected. Within the context of quantum tunneling, particle emission from a black hole is modeled as a quantum process wherein particles traverse the event horizon. The likelihood of such tunneling events can be determined using the methodologies outlined in Refs. [

47,

48,

49], along with the associated literature referenced therein.

Black hole radiation arises from their inherent temperature, in a manner analogous to blackbody radiation. Nevertheless, the emitted spectrum is subject to modification by greybody factors, which alter the characteristics of the outgoing radiation. The spectrum is anticipated to comprise particles of various spin types, including fermions. Foundational work in Ref. [

50], along with subsequent investigations [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56], has demonstrated that massless bosons and fermions radiate at an identical temperature. Furthermore, studies of spin–1 bosons indicate that the Hawking temperature remains unaffected, even when quantum corrections beyond the semiclassical approximation—specifically those of higher–order in

ℏ are taken into account [

57,

58].

The behaviour of fermions is frequently characterized by the phase of the spinor wave function, which satisfies the Hamilton–Jacobi equation. An alternative formulation of the action, as proposed in [

46,

59,

60], is expressed as

where

denotes the classical action for scalar particles and

accounts for the spin corrections. These spin–dependent terms arise from the coupling between the fermion’s intrinsic spin and the background spin connection, and they ensure the regularity of the solution at the event horizon. Given that such corrections primarily influence spin precession and are typically small in magnitude, they are neglected in the present analysis. Additionally, the contribution of emitted particles’ spin to the total angular momentum of the black hole is negligible–particularly for non–rotating black holes with masses significantly greater than the Planck mass [

46]. On average, emissions of particles with opposite spin orientations occur symmetrically, resulting in no net change to the black hole’s angular momentum.

This study examines the tunneling process of fermionic particles as they traverse the event horizon of a specific black hole spacetime. Alternative approaches, including those based on generalized Painlevé–Gullstrand and Kruskal–Szekeres coordinate systems, are explored in the seminal work [

50]. The analysis commences with a general form of the spacetime metric, as given in Equation (30). In a curved spacetime background, the behavior of fermions is governed by the Dirac equation, which takes the form

with

and

It is worth emphasizing that the coordinates are represented as

. The matrices

satisfy the defining relations of the Clifford algebra, given by

with

represents the

identity matrix. Based upon this formulation, the

matrices are prescribed as given below

In this context,

corresponds to the Pauli matrices, which obey the conventional commutation relation

. Additionally, the matrix associated with

can be equivalent to

To describe a Dirac field with its spin aligned upward along the positive

r–axis, the adopted ansatz is given by [

61]

This study focuses on the spin–up

configuration, while the spin–down

case, oriented along the negative

r–axis, follows a similar treatment. Substituting the ansatz (45) into the Dirac equation and following Vanzo et al. [

46], we keep only the leading–order terms in

ℏ

and if the action takes the form of

The following equations will be derived [

46]

The explicit forms of

and

do not influence the conclusion that Equations (52) and (54) yield the constraint

, indicating that

must be a complex-valued function. This condition applies to both outgoing and ingoing modes. As a result, in calculating the ratio of outgoing to ingoing tunneling probabilities, the contributions from

L cancel out, allowing it to be excluded from further consideration [

46]. For massless particles, Equations (51) and (53) admit two linearly independent solutions

In this framework,

and

correspond to the solutions describing outgoing and incoming particles, respectively [

46]. Accordingly, the total tunneling probability is given by

. Thus,

A key aspect is that the dominant energy condition, together with Einstein’s field equations, guarantees that

and

share the same zeros. Near

, these metric components exhibit a linear behavior, revealing the presence of a simple pole with a well–defined coefficient. By utilizing Feynman’s method, the following expression is found

Within this framework, the particle number density

associated with the specified black hole solution is governed by the relation

Figure 5 presents the particle creation density for fermions,

. Similar to the bosonic case, the NC parameter

leads to an enhancement in the magnitude of the particle production density.

Additionally,

Figure 6 presents a comparison of the particle creation densities for bosons and fermions. Overall, the bosonic case exhibits a greater magnitude at lower frequencies compared to the fermionic case.

5. Scalar Perturbation

This section examines the massless scalar perturbation through the non–commutative Reissner–Nordström black hole spacetime.

Due to the complex form of the metric, the Klein–Gordon equation can not be solved with a common numerical method. Here we follow the method introduced by Ref. [

62]. This novel method proposes considering the deformed stationary and axisymmetric metric in a perturbation form in which the deformation is controlled by a small dimensionless modification parameter

. According to this approach, the modified metric can be expressed via a correction term added to the main metric as

. Here

and

represent the metric incorporated into the modified and standard metric, respectively. Also,

denotes the correction coefficients. Building upon the approach introduced in Ref. [

63], a key assumption in this part is that the main metric function is Reissner–Nordström and the deformation caused by noncommutativity. Now the metric function in Equation (61) can be rewritten as

where

and the deformation is governed by small parameter

which is NC parameter

in our case. The corresponding coefficients for the modified metric components are derived as follows

Now, the Klein–Gordon equation can be explored in a new developed perturbation approach. First, the wave function can be decomposed considering two Killing vectors

and

as

where

, with

m denoting the azimuthal quantum number and

representing the frequency of the mode. The perturbative method can be applied by decomposing the operator

up to the first order of

[

35,

62,

63]

Utilizing the metric described in Equation (61), the following expressions for

and

are obtained

The function

admits an expansion in terms of associated Legendre functions

and corresponding radial functions

, expressed as

. Using this form of

leads to a the Schrödinger like differential equation for

as

where

, called the tortoise coordinate, is described as

and the effective potential is described in a perturbative form as

In this context, represents the effective potential associated with the standard Reissner–Nordström black hole, while accounts for the NC correction to the potential. We will investigate more about the effective potential in the following section.

5.1. Effective Potential

Conducting a series of algebraic steps, the effective potential expression is explicitly formulated as

where the coefficients

–

are described in Appendix I. It is worth noticing the important footprint of NC spacetime, that the standard form of the effective potential is solely dependent on the multipole number

l, and exhibits no explicit dependence on the azimuthal quantum number

m. However, the presence of NC breaks the degeneracy, and the effective potential is dependent on both

l and

m. Moreover, the coefficients of the effective potential

remain invariant under the sign change of the azimuthal number. For instance the effective potential for the case of

and

, will read the following expression

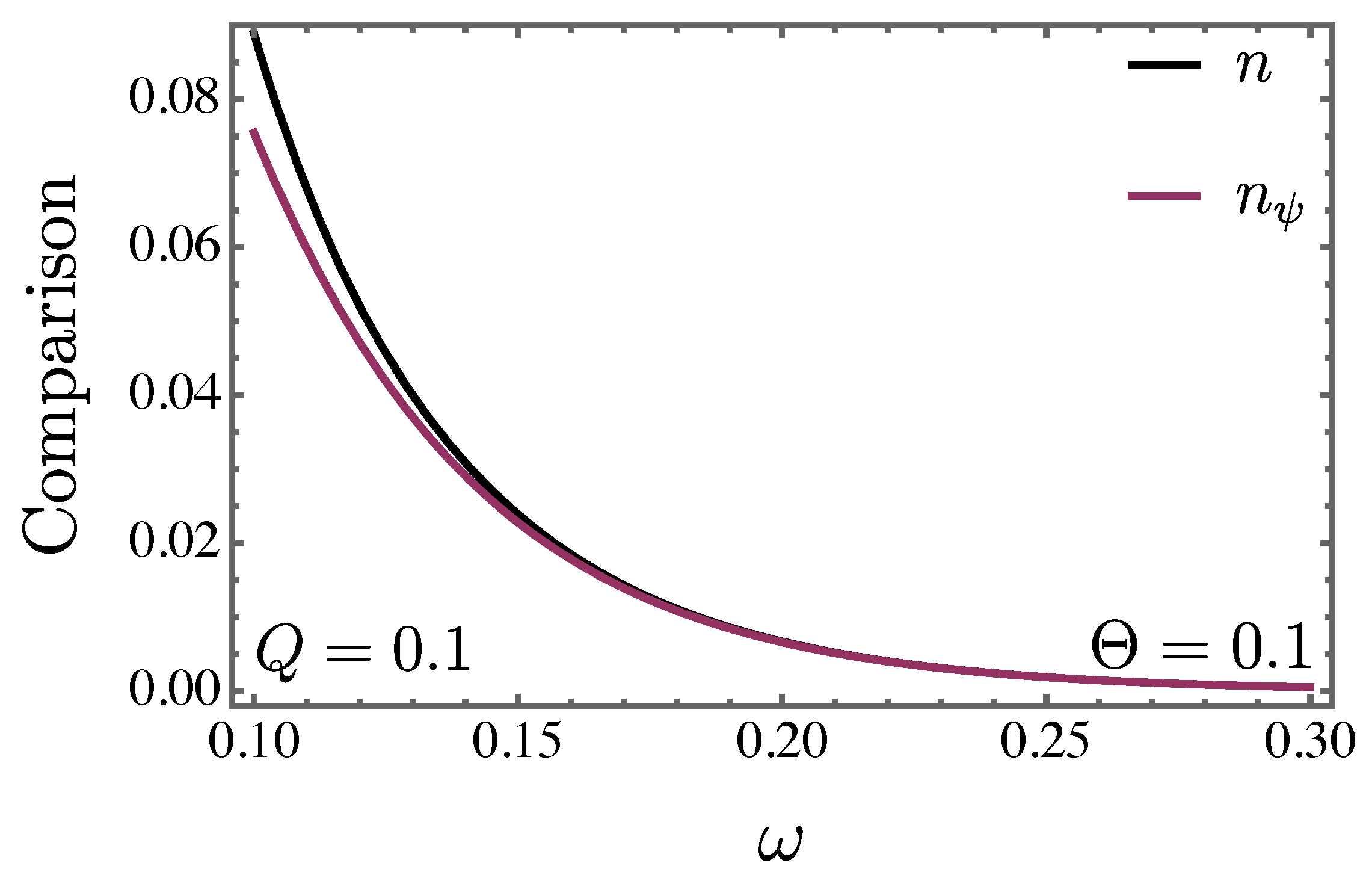

Figure 7 illustrates the effective potential,

, corresponding to fixed values of the mass

M, charge

, and different numbers of

l and

m. Specifically, the left panel displays

for

(

), while the middle and right panels show the plots for

and

(with

), respectively.

The effect of the NC parameter on the effective potential is illustrated in

Figure 7. Variations in the value of

lead to significant changes in the potential within NC spacetime. For all cases of

l, an increase in the NC parameter leads to a higher peak in the potentials, indicating that the effective potential becomes a more substantial barrier to field transmission. This suggests that the NC modifications may significantly change the QNMs and other scattering properties of the scalar field. To explore these effects in more detail, we will utilize the effective potential to calculate the scattering characteristics of the scalar field in the following sections.

5.2. Quasinormal Modes

In recent years, a variety of techniques have been employed to analyze quasinormal modes (QNMs), each offering distinct advantages and facing specific limitations [

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69]. Among these, the Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin (WKB) approximation has proven particularly Originally introduced by Schutz and Will [

70] in the study of black hole scattering phenomena, this semi–analytical method was later extended by Iyer and Konoplya [

64,

68,

71].

The application of the WKB method generally centers on the radial component of the perturbation field. In the context of black hole spacetimes, the imposition of physically motivated boundary conditions plays a crucial role: at the event horizon, the field must consist solely of ingoing waves; conversely, at spatial infinity, only outgoing waves are permitted.

To compute QNMs, we adopt the third–order WKB formalism with the following equation

In the WKB framework,

denotes the peak of the effective potential, while

describes the second derivative with respect to the tortoise coordinate

at that maximum. The terms

capture higher–order corrections associated with the

jth–order WKB expansion [

71].

Table 1 presents the QNM frequencies of scalar perturbations in a Reissner–Nordström black hole with fixed mass

and charge

, for multiple values of the NC parameter. The results indicate a change in both the real and imaginary components of the QNMs as

increases. Specifically, the real part, associated with oscillation frequency, shows an enhancement, whereas the imaginary part, linked to damping, becomes more negative, signifying faster decay of perturbations. This trend is observed consistently across different multipole numbers

, azimuthal numbers

m, and overtones

n.

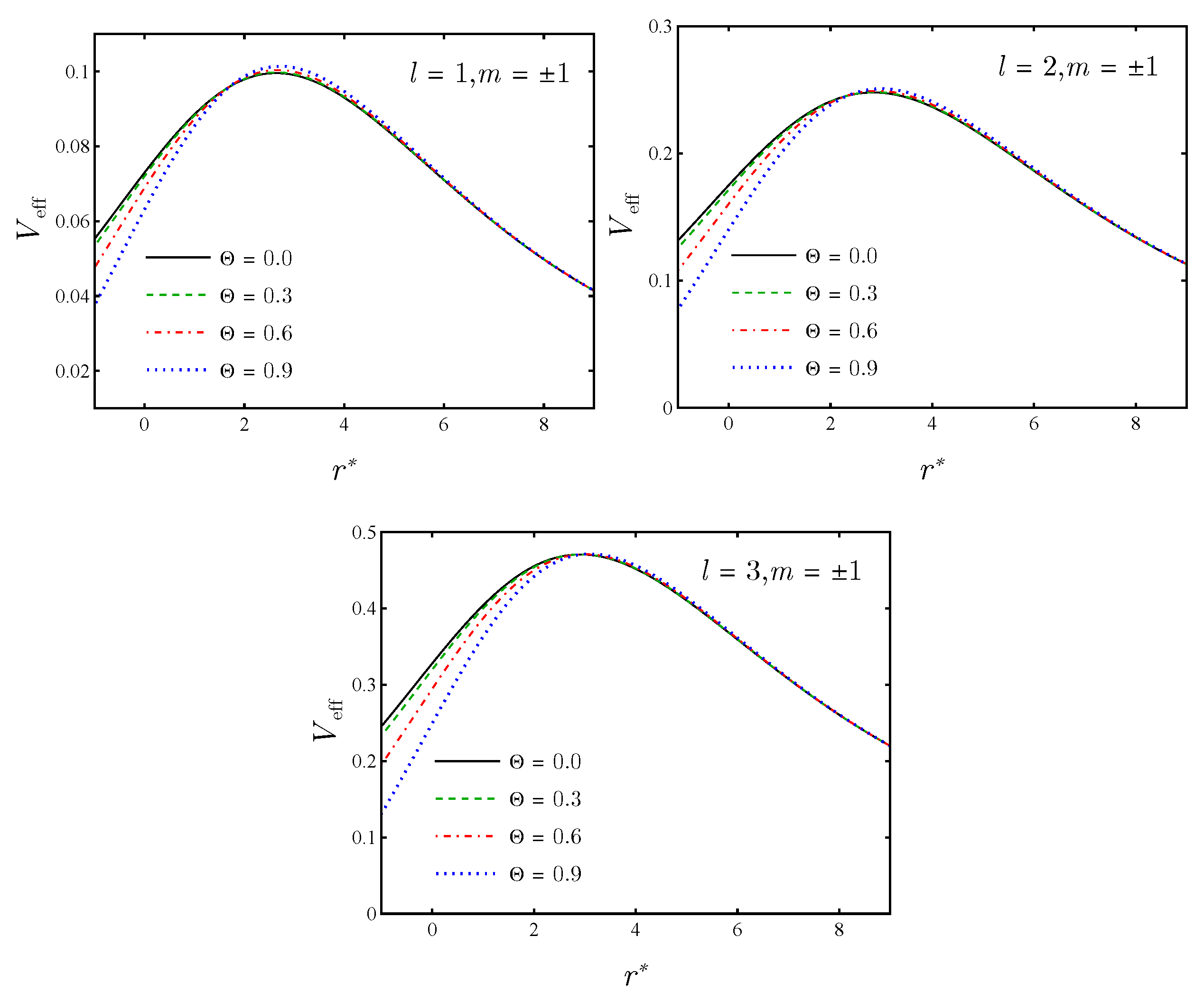

For better visualisation, the calculated QNMs for

are plotted and analyzed in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. The

Figure 8 demonstrates the variation of the real and imaginary part of QNM frequencies with both the NC parameter

and charge

Q for

, multipole number

and overtone

. There is a positive correlation between the real part of QNMs and

, which means that NC effects enhance oscillation frequencies. At a fixed value of

, a black hole with a higher charge

Q experiences a bigger propagation frequency as well. On the other hand, the absolute value of the imaginary part, which determines the damping rate, increases with increasing

. This indicates that higher NC impact enhances the dissipation of perturbations, causing them to decay faster. Moreover, for a given

, an increase in the black hole’s charge

Q results in a greater damping rate, as evidenced by a larger magnitude of the imaginary component

.

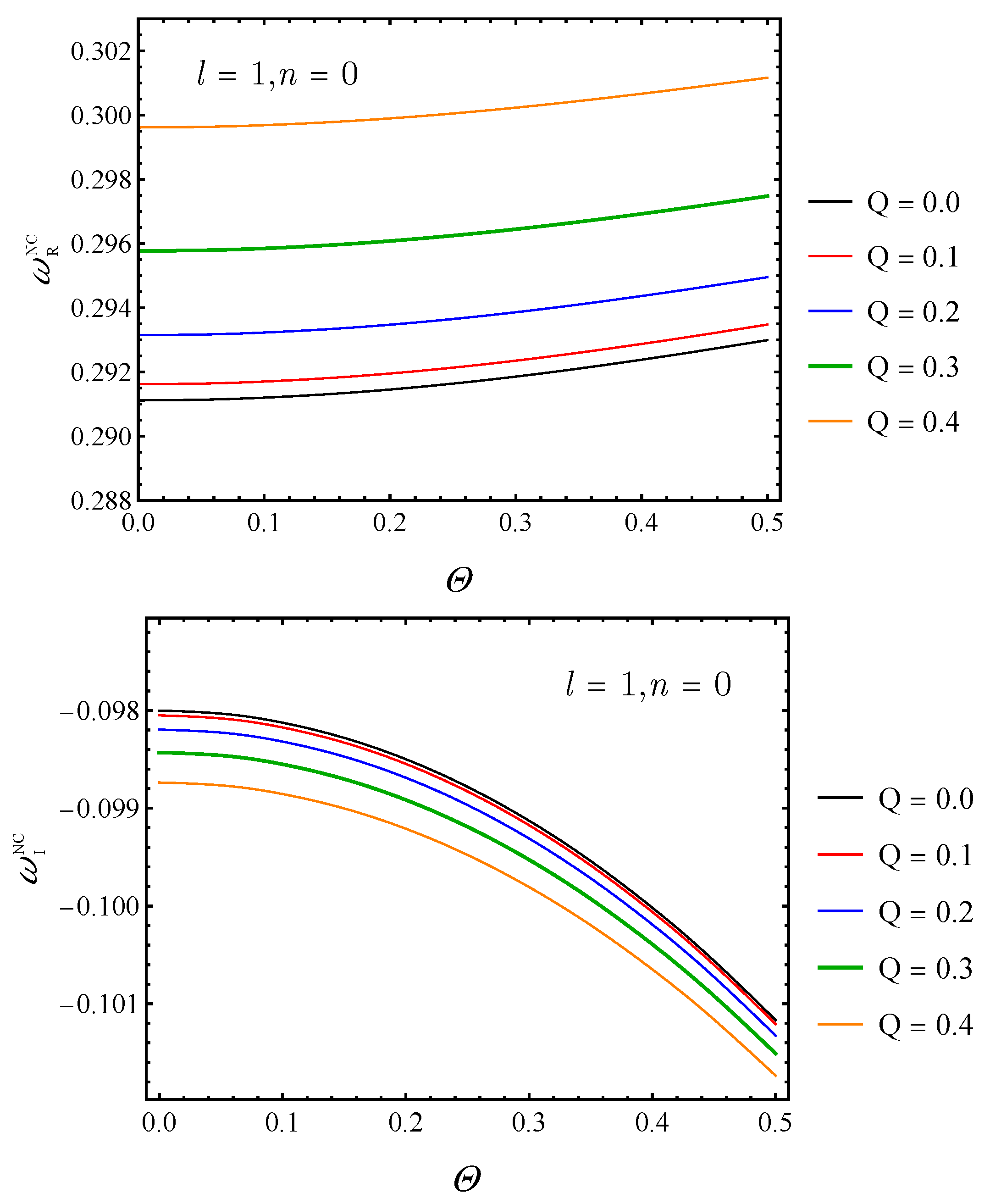

To investigate the influence of overtone number, as it is so subtle, first we introduce a normalized deviation

as

where

and

denote the QNMs of Reissner–Nordström black hole in non–commutative and commutative black hole, respectively.

Figure 9 represents the normalized deviation for both real and imaginary parts of QNMs for overtone

.

Our analysis shows that variations in the NC parameter produce qualitatively similar trends in both the real and imaginary components of QNMs across different overtone numbers. Notably, the normalized departure increases the real part more significantly for higher overtones, suggesting an enhancement in the oscillation frequency at higher modes. In contrast, the imaginary part, associated with the damping behavior, exhibits a stronger sensitivity to the NC parameter at lower overtone numbers, implying a shorter damping timescale for the black hole in the presence of NC spacetime.

6. Gravitational Lensing

Geodesics are fundamental to understanding the nature of spacetime, as they reveal its curvature and govern the motion of particles in gravitational fields. Exploring geodesics within the context of NC geometry has gained significant attention, as it examines the impact of quantum corrections on the spacetime structure. Exploring gravitational lensing in these contexts offers valuable insights into the behavior of particles at microscopic scales, where quantum effects are significant. Moreover, analyzing the geodesic structure of black hole spacetimes is essential for interpreting various astrophysical phenomena, including the characteristics of accretion disks or the formation of black hole shadows.

In this section, we comprehensively discuss the influence of the NC spacetime on the null–geodesic and gravitational lensing phenomena. The geodesic equation is derived by

where

s and

denote the affine parameter and the Christofell symbols, respectively Examining how NC affects the paths of massless particles is our primary goal in the following discussion.

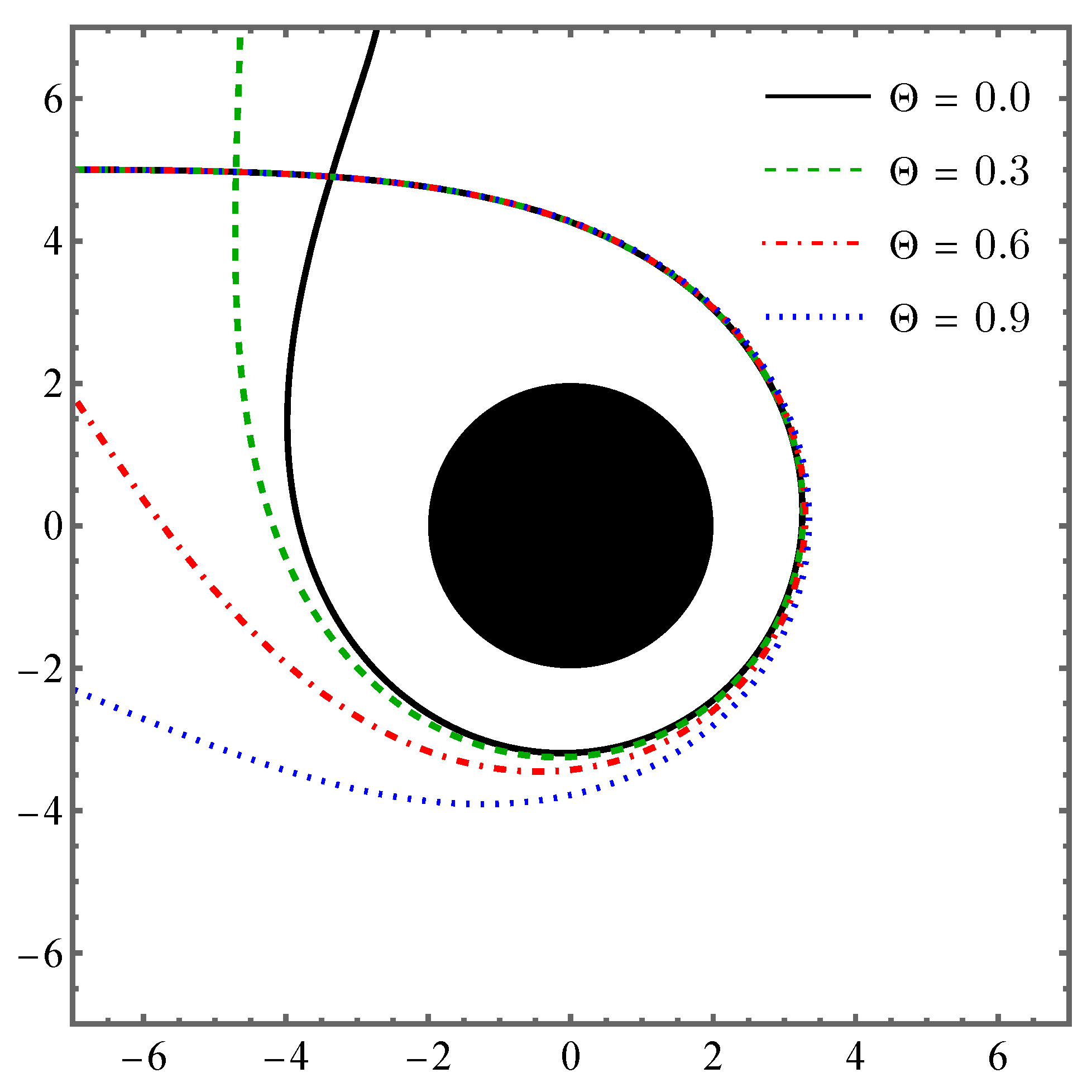

6.1. Light Trajectory

To accomplish the trajectory of the light, a series of extended partial differential equations derived from Equation (79) must be determined. The statement mentioned above specifically produces four coupled partial differential equations that need to be resolved for each coordinate as

where the terms

–

are presented in the appendix II. The light trajectories for a black hole with

,

and various values of the NC parameter are demonstrated in

Figure 10. It shows that the light trajectory for greater values of

is deflected less in the vicinity of the black hole. Therefore, the NC framework diminishes the gravitational lensing effects of the black hole on light rays. This effect of NC on the charged black hole is consistent with the finding reported in Ref. [

35], where the NC framework in the Schwarzschild black hole disempowers the gravitational lensing effect.

6.2. Photonic Radius

The study of photonic and shadow radius of a back hole represents a crucial area of research [

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77]. Interest in this topic has grown significantly, particularly after the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) captured the image of the

and

black hole [

78,

79,

80]. To analyze the shadow radius and the behavior of null geodesics, as outlined in Ref. [

81], we employ a diagonal metric with parameters

, expressed as follows

By applying this metric to the Lagrangian

formulation, defined as

Assuming geodesic motion confined to the equatorial plane,

, we set

. The corresponding Euler–Lagrange equations for coordinates

t and

results in two conserved quantities, the energy and angular momentum, denoted by

E and

L, as

Defining the impact parameter as

, we analyze the trajectory of light, which follows the condition

. This leads to the equation

By substituting Equation (86) into Equation (87), the light trajectory in the equatorial plane is obtained as

The conditions for circular photon orbits are given by

Solving this equation provides the radius of the photon sphere

, determined by

where prime denotes the derivative to the radius. Based on the metric functions described in Equation (17), and through further algebraic manipulations, the photon radius is determined as

The values of

are computed for

and varying

Q and

to examine the effect of NC on photon spheres. The data in

Table 2 reveal the dependence of the photon sphere radius on the charge and the NC parameter. As the charge

Q increases from 0.1 to 0.4, the photon sphere radius systematically decreases for all values of

. This trend suggests that higher charge values lead to a more compact photon sphere. Additionally, for a fixed charge, increasing the NC parameter also results in a gradual decrease in

. This indicates that NC effects contribute to a shift in the photon sphere location, potentially affecting observable astrophysical phenomena we are interested in exploring.

6.2.1. Topological Features of the Photonic Sphere

The photonic radius can be classified as stable or unstable. In standard spherical symmetric black holes, the stable circular orbits type yield instability in spacetime. Additionally, the unstable type can determine the shadows of the black hole [

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88]. In this part, the stability of the photon sphere is explored based on the topological method [

82]. First, a regular potential function is introduced as

where

. In the above expression, "

" and "

" serve as a factor that allows systematic topological analysis.

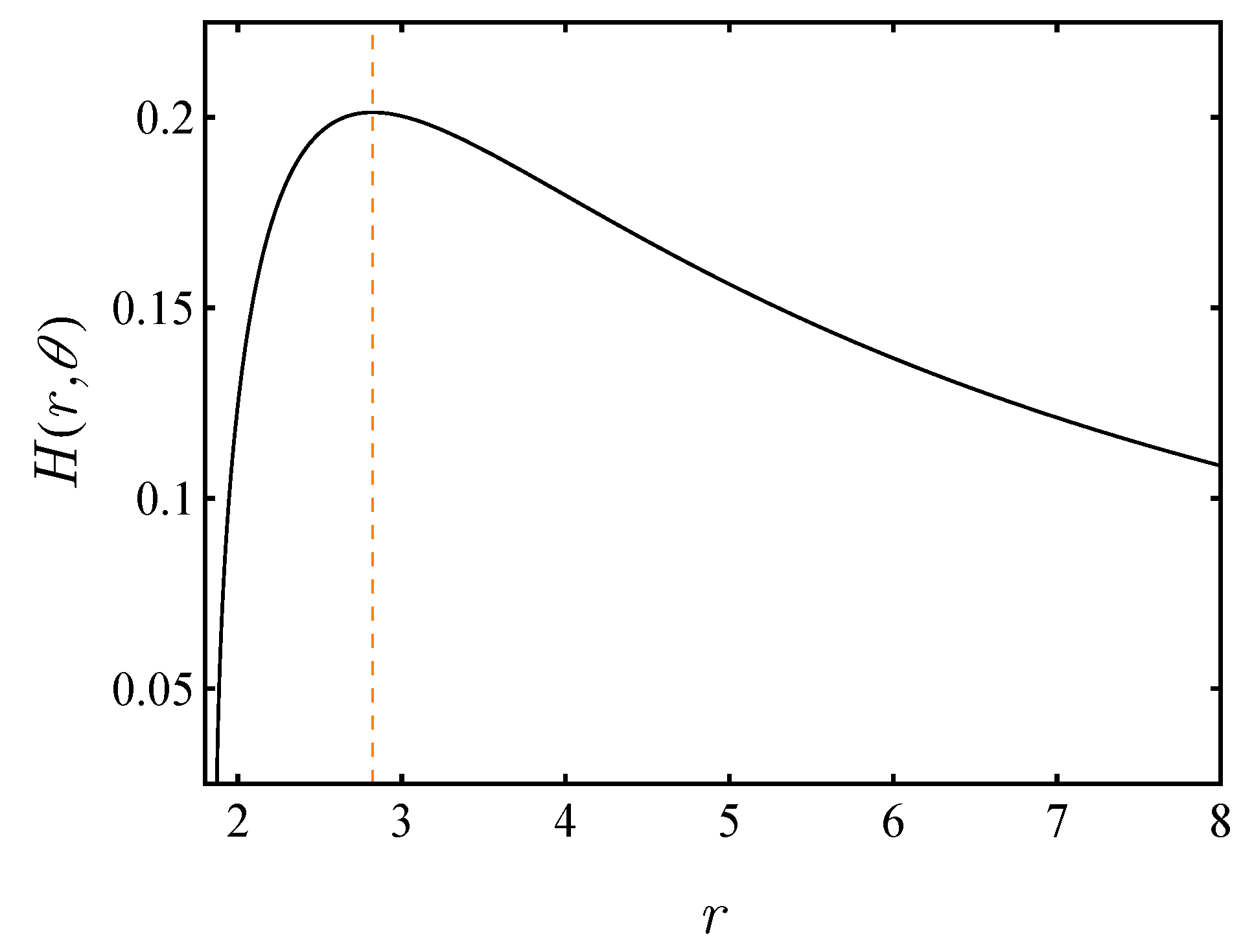

Figure 11 shows the behavior of potential

. The photon sphere locations correspond to critical points satisfying

. The maximum of the potential, for

,

, and

, is located at

and demonstrates that this photonic position is unstable. Minor disturbances can destabilize the photon trajectory, as seen in this plot, which can lead to the particle escaping outward or being caught by the black hole.

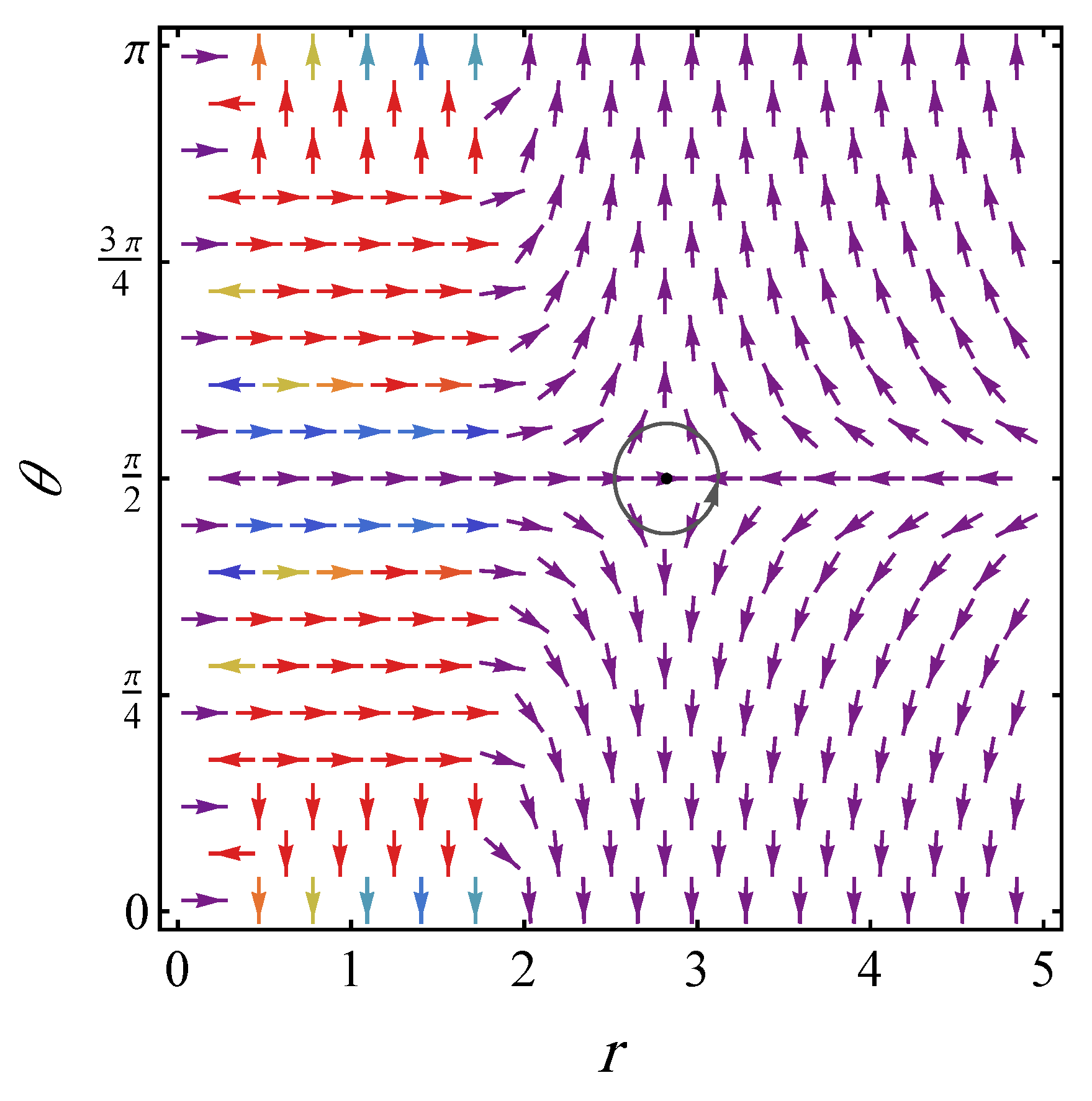

We define an associated vector field

with the following components

whose zeros correspond to the photon sphere positions. The complex representation

facilitates further topological analysis. The normalized vector components are expressed as

The photonic radius can be analyzed as topological defects occurring at points where the component of the field

vanishes. When a closed loop encloses such a zero point, it signifies that the net topological charge corresponds to the winding number. Each photon sphere associated with a black hole corresponds to a unique topological charge, denoted by

, which takes the discrete values of

. Following Ref. [

83,

89], the photonic sphere with

is unstable, and the one with

corresponds to a stable photonic radius.

Figure 12 illustrates the structure of the vector field, highlighting the only photon sphere larger than the event horizon located at

, where the field lines incorporate with a topological charge of

. Following the proposed insification proposed in Refs. [

82,

83,

84], this photon sphere remains intrinsically unstable.

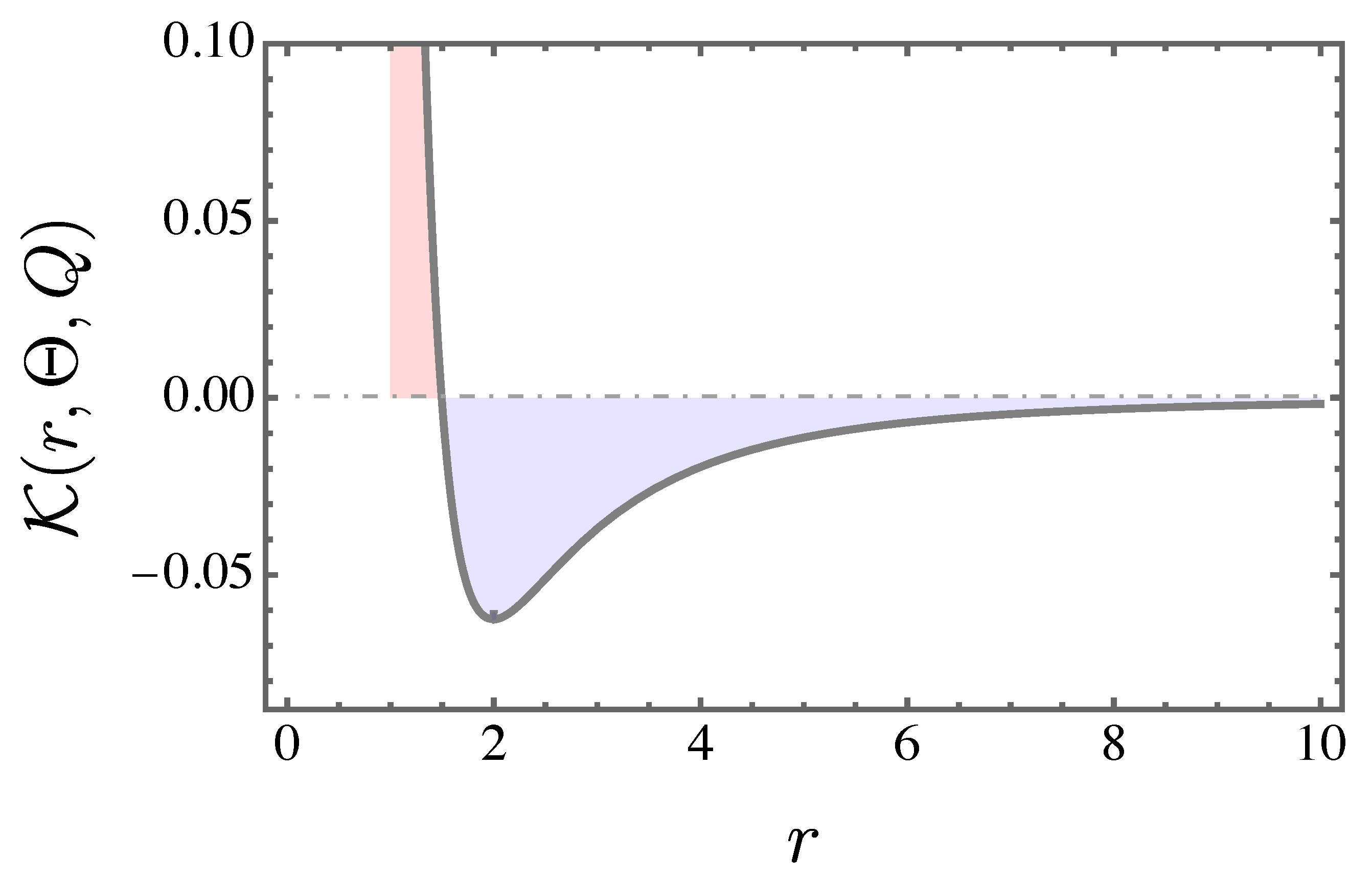

6.2.2. Stability of the Photon Sphere

The stability of photon spheres near black holes is primarily influenced by the geometric and topological features of the associated optical spacetime, with conjugate points playing a pivotal role. Under perturbations, the behavior of photon trajectories is determined by the stability properties of the photon sphere. For unstable configurations, even small deviations can cause photons to either fall into the black hole or escape to infinity. In contrast, stable photon spheres allow photons to remain confined in nearby bounded orbits [

90,

91].

The existence or absence of conjugate points within the spacetime manifold is a key factor influencing the stability of photon trajectories. Stable photon spheres are characterized by the presence of conjugate points, while their unstable counterparts are devoid of them. The Cartan–Hadamard theorem establishes a relationship between the Gaussian curvature

and the occurrence of conjugate points, offering a framework to evaluate the stability of critical orbits [

92]. In this context, the null geodesics—defined by the condition

– can be represented as follows [

93,

94]

where

i and

j range from 1 to 3,

denotes the components of the optical metric, and

. Moreover, the Gaussian curvature is calculated by [

92]

where

represents the Ricci scalar in two dimensions [

93]. When

is sufficiently small, an explicit approximation of the Gaussian curvature is given by

As discussed in Refs . [

90,

91,

92], the stability of photon spheres can be inferred from the sign of the Gaussian curvature

. Specifically, a negative curvature (

) signifies instability, whereas a positive curvature (

) indicates stability. To visualize this behavior,

Figure 13 presents

as a function of the radial coordinate

r, outlining the regions corresponding to stable and unstable photon spheres. The analysis is performed for

,

, and

. The transition point separating stable from unstable configurations is identified at

. In the plot, the pink region denotes the domain of stability, while the purple region represents instability. A comparison with results from the photon sphere analysis confirms that the critical orbits considered in this work lie within the unstable regime.

6.3. Shadow Radius

The shadow of a spherically symmetric black hole can be calculated by the following expression [

95,

96],

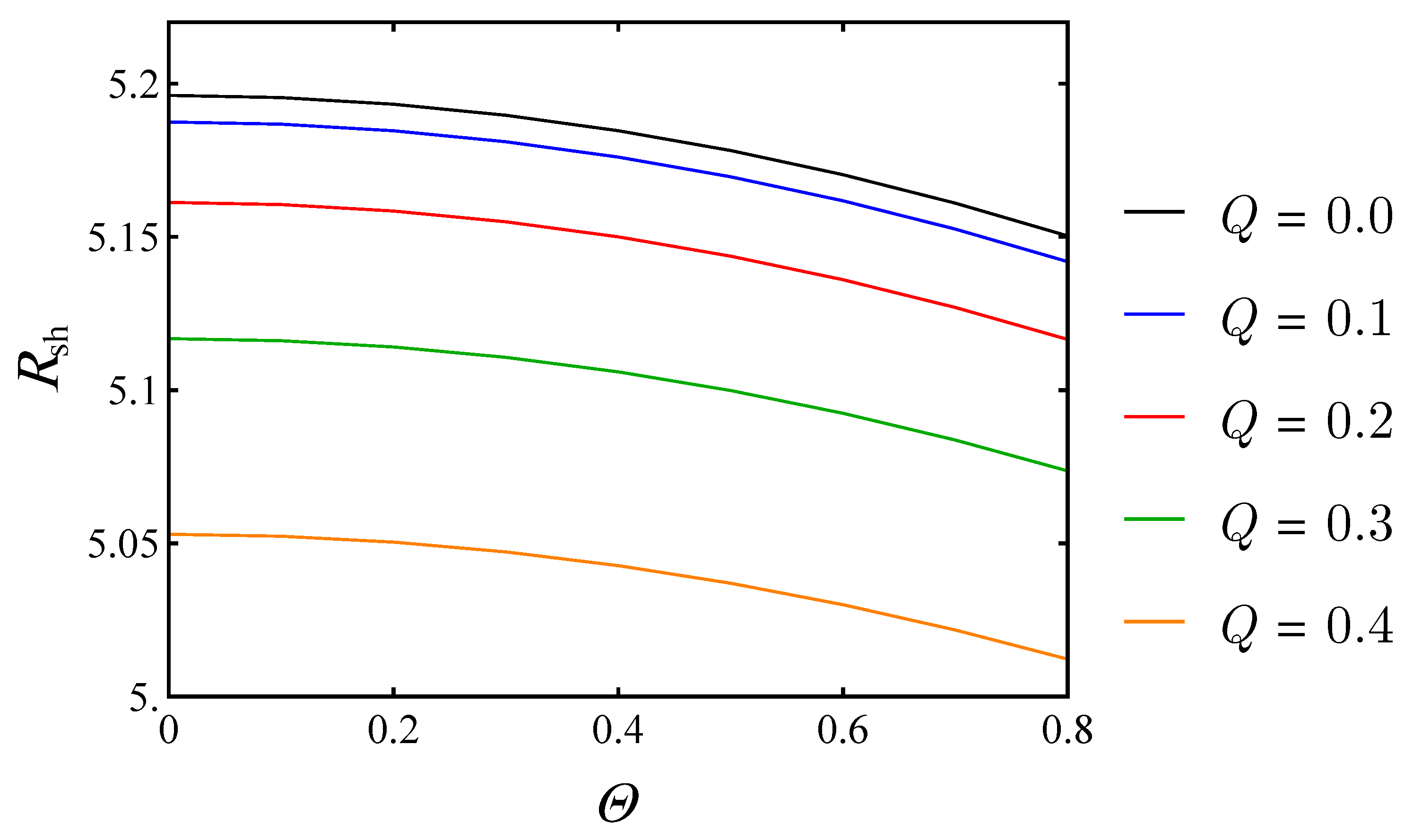

In

Figure 14, we present an analysis of the shadow radius concerning the NC parameter for a few charge

Q for improved visualization.

The shadow radius clearly decreases with an increase in the non-commutative parameter for all charge levels, indicating that significantly influences the size of the black hole shadow. Conversely, given a constant NC parameter, a reduced charge results in an increased shadow radius.

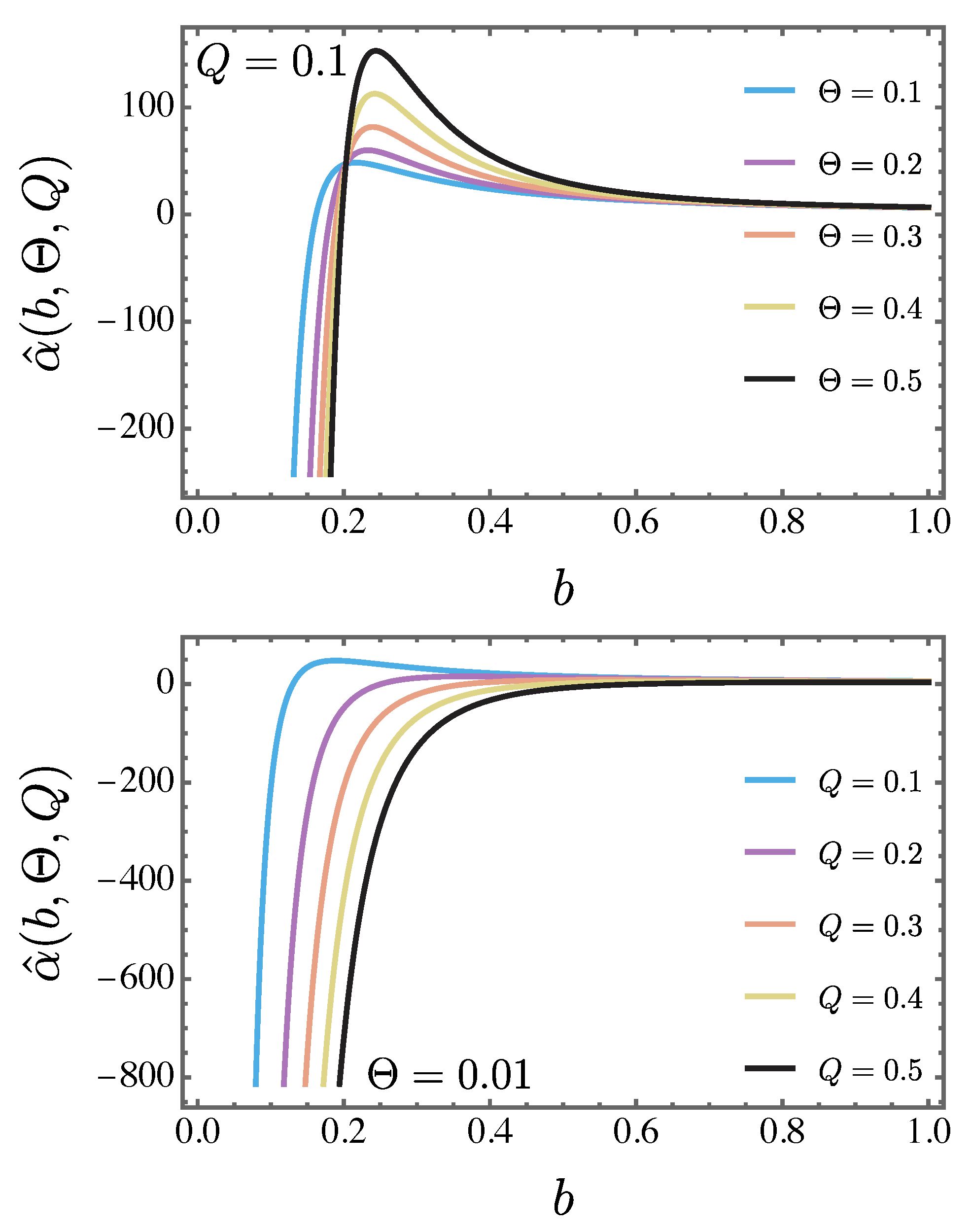

6.4. Gravitational Lensing

Building upon the expression for the Gaussian curvature obtained in Equation (98), the next step involves computing the deflection angle in the weak–field approximation by employing the Gauss–Bonnet theorem [

97]. To facilitate this, the surface element on the equatorial plane is evaluated and can be written as

enabling us to calculate the deflection angle with the following expression

Figure 15 depicts the variation of the deflection angle

. For a fixed impact parameter

, an increase in the NC parameter

corresponds to an enhancement in the magnitude of

. Conversely, raising the charge parameter

Q produces a decrease in the deflection angle.

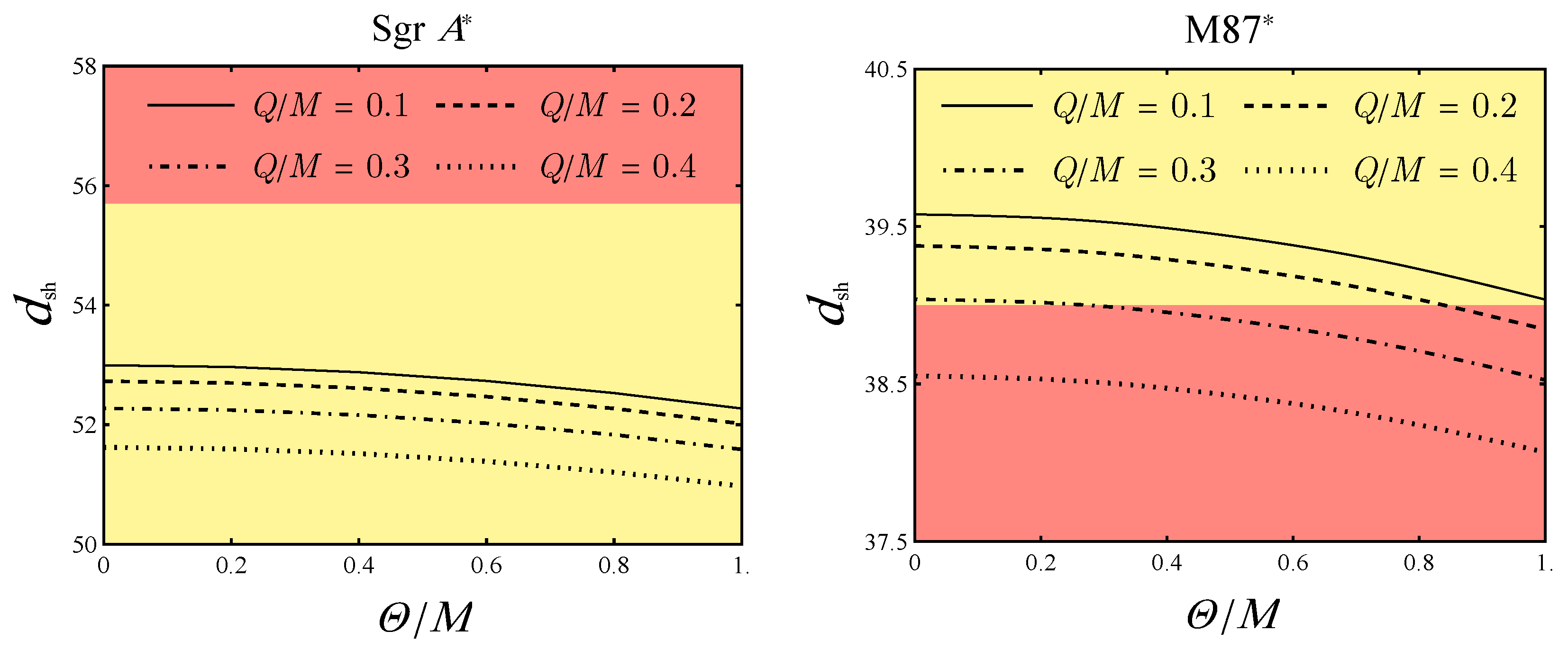

6.5. Lensing Observable

By analyzing the black hole shadow observations of

and

obtained by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), we explore potential constraints on the NC parameter

within the framework of a charged black hole in NC geometry. The angular diameter (radius) of the shadow,

, plays a crucial role in probing deviations from classical general relativity. By comparing the theoretical shadow diameter predictions with EHT measurements, we assess whether the observational data places any bounds on the NC parameter. A distant observer, located at a radial distance

from the black hole, measures the angular diameter

of the black hole shadow as [

98,

99]

To explore the constraints on

, based on both

and

observations, the charged NC black hole shadow as a function of

is shown in

Figure 16.

In the left panel, we assumed that the mass and distance to the observer were and , for the NC charged black hole as the black hole.

The angular diameter for different values of charge

Q and variation of NC parameter

, does not show any constraint to be in the EHT collaboration reported mean value range

[

100,

101].

On the right panel, for the

case, we consider mass and distance to observer to be as

and

. The angular diameter of the

black hole shadow is inferred to be

based on the EHT data [

102,

103]. In the context of the Reissner-Nordström black hole as a model for

, our analysis reveals specific constraints on the parameter

, which depend on the charge value

. Notably, when the ratio

, no restrictions are placed on the NC parameter. However, at values of

and

, the parameter

is constrained to be less than

and

, respectively. Furthermore, for

, no permissible values for

exist.

7. Conclusions

In this study, we have explored the profound implications of non–commutative geometry on the properties of a charged black hole, providing a detailed analysis of the thermodynamic behavior, quantum radiation, scalar perturbations, and optical characteristics. We have derived a consistent deformed spacetime geometry of a Reissner-Nordström black hole that captures up to second–order corrections in the non-commutative parameter .

The thermodynamic analysis revealed significant modifications to the black hole’s thermal properties. The Hawking temperature and heat capacity were found to depend on both the charge Q and the NC parameter , leading to the existence of a finite remnant mass at the end of the evaporation process. The study of Hawking radiation demonstrated distinct behaviors for bosonic and fermionic particles, with bosons exhibiting higher emission probabilities at low frequencies. Our investigation continued by examining the scalar perturbations. The calculated quasinormal modes showed increased oscillation frequencies and enhanced damping rates compared to the commutative case, with a significant imprint. The non–commutativity leads to the breakdown of the degeneracy between different angular mode,s which has not been detected in commutative spacetime. Furthermore, the photon sphere and shadow analysis revealed that non-commutative corrections results in a reduction in both the photon orbit radius and the apparent shadow size. The gravitational lensing calculations in the weak–deflection limit demonstrated that both non–commutative geometry and the charge alter light deflection, suggesting that these effects might be detectable in future high-precision observations of gravitational lensing by compact objects. Finally, the comparison of the lensing observables with Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) observations of and has been discussed to obtain constraints on the NC parameter.

The theoretical framework developed here may be applied as a foundation for further investigations into more complex scenarios, such as rotating black holes, potentially leading to new insights into the quantum nature of spacetime.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Professor A. A. Araújo Filho for insightful discussions and valuable support with the thermodynamic analysis and gravitational lensing computations.

Appendix A

The coefficients of the effective potential in Equation (75) are as follows

Appendix B

The coefficients of the geodesic equations presented in Equation (80)–(83) are introduced as follows

References

- Snyder, H.S. Quantized Space-Time. Phys. Rev. 1947, 71, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiberg, N.; Witten, E. String theory and noncommutative geometry. JHEP 1999, 1999, 032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, R.J. Quantum field theory on noncommutative spaces. Phys. Rept. 2003, 378, 207–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connes, A.; Douglas, M.R.; Schwarz, A. Noncommutative geometry and matrix theory. Journal of High Energy Physics 1998, 1998, 003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardalan, F.; Arfaei, H.; Sheikh-Jabbari, M.M. Noncommutative geometry from strings and branes. Journal of High Energy Physics 1999, 1999, 016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.R.; Nekrasov, N.A. Noncommutative field theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2001, 73, 977–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connes, A. Noncommutative Geometry; Academic Press, 1994.

- Nicolini, P. Noncommutative Black Holes, the Final Appeal to Quantum Gravity: A Review. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 2009, 24, 1229–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiberg, N.; Witten, E. String theory and noncommutative geometry. Journal of High Energy Physics 1999, 1999, 032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Nicolini, A.S.; Spallucci, E. Noncommutative geometry inspired Schwarzschild black hole. Phys. Lett. B 2006, 632, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Spallucci, A.S.; Nicolini, P. Non-commutative geometry inspired higher-dimensional charged black holes. Phys. Lett. B 2009, 670, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozari, K.; Mehdipour, S.H. Hawking radiation as quantum tunneling from a noncommutative Schwarzschild black hole. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2008, 25, 175015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo Filho, A.; Heidari, N. Geodesics, accretion disk, gravitational lensing, time delay, and effects on neutrinos induced by a non–commutative black hole.

- Smailagic, A.; Spallucci, E. Feynman path integral on the noncommutative plane. J. Phys. A 2003, 36, L467–L471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurčo, B.; Möller, L.; Schraml, S.; Schupp, P.; Wess, J. Construction of non-Abelian gauge theories on noncommutative spaces. The European Physical Journal C-Particles and Fields 2001, 21, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Chaichian, P. Presnajder, M.M.S.J.; Tureanu, A. Noncommutative gauge field theories: A No-go theorem. Phys. Lett. B 2002, 526, 132–136. [CrossRef]

- et al., P.A. A Gravity theory on noncommutative spaces. Class. Quant. Grav. 2006, 23, 1883–1912. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.; Mukherjee, P.; Samanta, S. Lie algebraic noncommutative gravity. Physical Review D—Particles, Fields, Gravitation, and Cosmology 2007, 75, 125020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaichian, M.; Tureanu, A.; Zet, G. Corrections to Schwarzschild solution in noncommutative gauge theory of gravity. Physics Letters B 2008, 660, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaichian, M.; Tureanu, A.; Setare, M.; Zet, G. On Black Holes and Cosmological Constant inNoncommutative Gauge Theory of Gravity. Journal of High Energy Physics 2008, 2008, 064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.; Saha, A. Deformed Reissner–Nordstrom solutions in noncommutative gravity. Physical Review D—Particles, Fields, Gravitation, and Cosmology 2008, 77, 064014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, R.; Maceda, M.; Sánchez-Santos, O. Thermodynamical properties of a noncommutative anti–de Sitter–Einstein-Born-Infeld spacetime from gauge theory of gravity. Physical Review D 2020, 101, 044008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, N.; Hassanabadi, H.; Kr̆íz̆, J.; Zare, S.; Porfírio, P.; et al. Gravitational signatures of a non–commutative stable black hole. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.06838 2023.

- Heidari, N.; Lobo, I.P.; et al. Non-commutativity in Hayward spacetime. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.17789 2025.

- Bežanić, M.; Ćirić, M.D.; Konjik, N.; Nikolić, B.; Samsarov, A. Noncommutative fields in Reissner-Nordstr∖"{o} m black hole background. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.06181 2025.

- Ćirić, M.D.; Konjik, N.; Samsarov, A. Noncommutative scalar quasinormal modes of the Reissner–Nordström black hole. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2018, 35, 175005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herceg, N.; Jurić, T.; Kumara, A.N.; Samsarov, A.; Smolić, I. Noncommutative quasinormal modes of Schwarzschild black hole. Journal of High Energy Physics 2025, 2025, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamseddine, A.H.; Connes, A.; van Suijlekom, W.D. Noncommutativity and physics: a non-technical review. The European Physical Journal Special Topics 2023, pp. 1–8.

- R. Banerjee, B. Chakraborty, S.G.; Saha, A. Interacting quantum field theory in kappa-Minkowski spacetime. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 83, 124036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo Filho, A.; Zare, S.; Porfírio, P.; Kříž, J.; Hassanabadi, H. Thermodynamics and evaporation of a modified Schwarzschild black hole in a non–commutative gauge theory. Physics Letters B 2023, 838, 137744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.; Majhi, B.R.; Samanta, S. Noncommutative black hole thermodynamics. Physical Review D 2008, 77, 124035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdipour, S.H. Hawking radiation as tunneling from a Vaidya black hole in noncommutative gravity. Physical Review D 2010, 81, 124049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al., Y.Z. Quasinormal modes in noncommutative Schwarzschild black holes. Nucl. Phys. B 2024, 1004, 116545. [CrossRef]

- K. Lin, W.L.Q.; Pavan, A.B. Quasinormal modes and greybody factors of noncommutative black holes. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 99, 084041. [CrossRef]

- Heidari, N.; Hassanabadi, H.; Araújo Filho, A.A.; Kriz, J. Exploring non-commutativity as a perturbation in the Schwarzschild black hole: quasinormal modes, scattering, and shadows. The European Physical Journal C 2024, 84, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.A.V.; Anacleto, M.A.; Brito, F.; Passos, E. Quasinormal modes and shadow of noncommutative black hole. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 8516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.W.; Cheng, P.; Zhong, Y.; Zhou, X.N. Shadow of noncommutative geometry inspired black hole. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2015, 2015, 004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurić, T.; Kumara, A.N.; Požar, F. Constructing noncommutative black holes. Nuclear Physics B 2025, p. 116950.

- Touati, A. Non-commutative gauge theory and quantum gravity. Ph. D. Thesis 2024.

- Touati, A.; Slimane, Z. Quantum tunneling from Schwarzschild black hole in non-commutative gauge theory of gravity. Physics Letters B 2024, 848, 138335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo Filho, A.A.; Jusufi, K.; Cuadros-Melgar, B.; Leon, G. Dark matter signatures of black holes with yukawa potential. Physics of the Dark Universe 2024, 44, 101500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo Filho, A.A.; Jusufi, K.; Cuadros-Melgar, B.; Leon, G.; Jawad, A.; Pellicer, C. Charged black holes with yukawa potential. Physics of the Dark Universe 2024, 46, 101711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo Filho, A.A.; Furtado, J.; Reis, J.A.A.S.; Silva, J.E.G. Thermodynamical properties of an ideal gas in a traversable wormhole. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2023, 40, 245001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, A.A.A. Implications of a Simpson–Visser solution in Verlinde’s framework. Eur. Phys. J. C 2024, 84, 73, [arXiv:gr-qc/2308.04939]. [CrossRef]

- Filho, A.A.A. Analysis of a regular black hole in Verlinde’s gravity. Class. Quant. Grav. 2024, 41, 015003, [arXiv:gr-qc/2306.07226]. [CrossRef]

- Vanzo, L.; Acquaviva, G.; Di Criscienzo, R. Tunnelling methods and Hawking’s radiation: achievements and prospects. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2011, 28, 183001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angheben, M.; Nadalini, M.; Vanzo, L.; Zerbini, S. Hawking radiation as tunneling for extremal and rotating black holes. Journal of High Energy Physics 2005, 2005, 014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerner, R.; Mann, R.B. Tunnelling, temperature, and Taub-NUT black holes. Physical Review D 2006, 73, 104010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerner, R.; Mann, R.B. Fermions tunnelling from black holes. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2008, 25, 095014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerner, R.; Mann, R.B. Fermions tunnelling from black holes. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2008, 25, 095014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.; Saifullah, K. Charged fermions tunneling from accelerating and rotating black holes. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2011, 2011, 001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.L.; Yang, S.Z.; Zhou, T.J.; Lin, R. Fermion tunneling from a Vaidya black hole. Europhysics Letters 2008, 84, 20003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Criscienzo, R.; Vanzo, L. Fermion tunneling from dynamical horizons. Europhysics Letters 2008, 82, 60001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yale, A.; Mann, R.B. Gravitinos tunneling from black holes. Physics Letters B 2009, 673, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerner, R.; Mann, R.B. Charged fermions tunnelling from Kerr–Newman black holes. Physics letters B 2008, 665, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yale, A. Exact Hawking radiation of scalars, fermions, and bosons using the tunneling method without back-reaction. Physics Letters B 2011, 697, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yale, A. There are no quantum corrections to the Hawking temperature via tunneling from a fixed background. The European Physical Journal C 2011, 71, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, B.; Mitra, P. Hawking temperature and higher order calculations. Physics Letters B 2009, 675, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cognola, G.; Vanzo, L.; Zerbini, S.; Soldati, R. On the lagrangian formulation of a charged spinning particle in an external electromagnetic field. Physics Letters B 1981, 104, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barducci, A.; Casalbuoni, R.; Lusanna, L. Supersymmetries and the pseudoclassical relativistic electron. Nuovo Cimento. A 1976, 35, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagnozzi, S.; Roy, R.; Tsai, Y.D.; Visinelli, L. Horizon-scale tests of gravity theories and fundamental physics from the Event Horizon Telescope image of Sagittarius A∗. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.07787 2022.

- Chen, C.Y.; Chiang, H.W.; Tsao, J.S. Eikonal quasinormal modes and photon orbits of deformed Schwarzschild black holes. Physical Review D 2022, 106, 044068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cai, Y.; Das, S.; Lambiase, G.; Saridakis, E.; Vagenas, E. Quasinormal modes in noncommutative Schwarzschild black holes. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.09147 2023.

- Iyer, S.; Will, C.M. Black-hole normal modes: A WKB approach. I. Foundations and application of a higher-order WKB analysis of potential-barrier scattering. Physical Review D 1987, 35, 3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, V.; Mashhoon, B. New approach to the quasinormal modes of a black hole. Physical Review D 1984, 30, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konoplya, R.A. Quasinormal modes of a small Schwarzschild–anti-de Sitter black hole. Physical Review D 2002, 66, 044009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaver, E.W. Spectral decomposition of the perturbation response of the Schwarzschild geometry. Physical Review D 1986, 34, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konoplya, R.; Zhidenko, A.; Zinhailo, A. Higher order WKB formula for quasinormal modes and grey-body factors: recipes for quick and accurate calculations. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2019, 36, 155002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, N.; Hassanabadi, H. Investigation of the quasinormal modes of a Schwarzschild black hole by a new generalized approach. Physics Letters B 2023, 839, 137814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, B.F.; Will, C.M. Black hole normal modes: a semianalytic approach. The Astrophysical Journal 1985, 291, L33–L36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konoplya, R. Quasinormal behavior of the D-dimensional Schwarzschild black hole and the higher order WKB approach. Physical Review D 2003, 68, 024018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.X.; Li, G.P.; He, K.J. The shadows and observational appearance of a noncommutative black hole surrounded by various profiles of accretions. Nuclear Physics B 2022, 974, 115639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panah, B.E.; Heidari, N. Some aspects of ModMax (A) dS black holes: Thermodynamics properties, heat engine, shadow, null geodesic and light trajectory. Journal of High Energy Astrophysics 2025, 45, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, N.; Lobo, I.; Bezerra, V.; et al. Gravitational signatures of a nonlinear electrodynamics in f (R, T) gravity. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.08718 2025.

- Hamil, B.; Lütfüoğlu, B. Thermodynamics and Shadows of quantum-corrected Reissner–Nordström black hole surrounded by quintessence. Physics of the Dark Universe 2023, 42, 101293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anacleto, M.; Brito, F.; Campos, J.; Passos, E. Absorption, scattering and shadow by a noncommutative black hole with global monopole. The European Physical Journal C 2023, 83, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wan, M.; Wu, C. Shadows and quasinormal modes of a charged non-commutative black hole by different methods. The European Physical Journal Plus 2023, 138, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D.; Chan, C.k.; Christian, P.; Jannuzi, B.T.; Kim, J.; Marrone, D.P.; Medeiros, L.; Ozel, F.; Psaltis, D.; Rose, M.; et al. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. I. The Shadow of the Supermassive Black Hole 2019.

- Gralla, S.E. Can the EHT M87 results be used to test general relativity. Physical Review D 2021, 103, 024023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, K.; Alberdi, A.; Alef, W.; Asada, K.; Azulay, R.; Baczko, A.K.; Ball, D.; Baloković, M.; Barrett, J.; Bintley, D.; et al. First M87 event horizon telescope results. V. Physical origin of the asymmetric ring. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2019, 875, L5. [Google Scholar]

- Batic, D.; Nelson, S.; Nowakowski, M. Light on curved backgrounds. Physical Review D 2015, 91, 104015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.W. Topological Charge and Black Hole Photon Spheres 2020. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, P.V.P.; Herdeiro, C.A.R. Stationary black holes and light rings 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, J.; Afshar, M.A.S. The Role of Topological Photon Spheres in Constraining the Parameters of Black Holes 2024. [CrossRef]

- Brzo, A.B.; Gashti, S.N.; Pourhassan, B.; Beikpour, S. Thermodynamic topology of AdS black holes within non-commutative geometry and Barrow entropy. Nuclear Physics B 2025, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, M.R.; Afshar, M.A.S.; Gashti, S.N.; Sadeghi, J. Weak Gravity Conjecture Validation with Photon Spheres of Quantum Corrected AdS-Reissner-Nordstrom Black Holes in Kiselev Spacetime. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.14352 2024.

- Sadeghi, J.; Afshar, M.A.S.; Gashti, S.N.; Alipour, M.R. Thermodynamic Topology and Photon Spheres in the Hyperscaling violating black holes 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pantig, R.C.; Övgün, A. Multimodal signatures of asymptotic (A)dS Kalb-Ramond black holes: Constraints through the shadow, weak deflection angle, and topological photon spheres 2025.

- Duane, Y. THE STRUCTURE OF THE TOPOLOGICAL CURRENT*. Technical report, 1984.

- Qiao, C.K. Curvatures, photon spheres, and black hole shadows. Physical Review D 2022, 106, 084060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, C.K.; Li, M. Geometric approach to circular photon orbits and black hole shadows. Physical Review D 2022, 106, L021501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, C.K. The Existence and Distribution of Photon Spheres Near Spherically Symmetric Black Holes–A Geometric Analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.14035 2024.

- Araújo Filho, A.A.; Nascimento, J.R.; Petrov, A.Y.; Porfírio, P.J.; Övgün, A. Effects of non-commutative geometry on black hole properties. Physics of the Dark Universe 2024, 46, 101630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, N.; Araújo Filho, A.A.; Pantig, R.C.; Övgün, A. Absorption, scattering, geodesics, shadows and lensing phenomena of black holes in effective quantum gravity. Phys. Dark Univ. 2025, 47, 101815, [arXiv:gr-qc/2410.08246]. [CrossRef]

- Perlick, V.; Tsupko, O.Y.; Bisnovatyi-Kogan, G.S. Influence of a plasma on the shadow of a spherically symmetric black hole. Physical Review D 2015, 92, 104031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konoplya, R. Shadow of a black hole surrounded by dark matter. Physics Letters B 2019, 795, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, G.W.; Werner, M.C. Applications of the Gauss-Bonnet theorem to gravitational lensing. Class. Quant. Grav. 2008, 25, 235009, [arXiv:gr-qc/0807.0854]. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Ghosh, S.G. Rotating black holes in 4D Einstein-Gauss-Bonnet gravity and its shadow. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2020, 2020, 053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, M.; Vagnozzi, S.; Ghosh, S.G. Tests of loop quantum gravity from the event horizon telescope results of Sgr A. The Astrophysical Journal 2023, 944, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, K.; Alberdi, A.; Alef, W.; Algaba, J.C.; Anantua, R.; Asada, K.; Azulay, R.; Bach, U.; Baczko, A.K.; Ball, D.; et al. First Sagittarius A* Event Horizon Telescope results. IV. Variability, morphology, and black hole mass. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2022, 930, L15. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, K.; Alberdi, A.; Alef, W.; Algaba, J.C.; Anantua, R.; Asada, K.; Azulay, R.; Bach, U.; Baczko, A.K.; Ball, D.; et al. First Sagittarius A* event horizon telescope results. VI. Testing the black hole metric. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2022, 930, L17. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, K.; Alberdi, A.; Alef, W.; Asada, K.; Azulay, R.; Baczko, A.; Ball, D.; Baloković, M.; Barrett, J.; Collaboration, E.H.T.; et al. First M87 event horizon telescope results. I. The shadow of the supermassive black hole. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2019, 875. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, K.; Alberdi, A.; Alef, W.; Asada, K.; Azulay, R.; Baczko, A.K.; Ball, D.; Baloković, M.; Barrett, J.; Bintley, D.; et al. First M87 event horizon telescope results. VI. The shadow and mass of the central black hole. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2019, 875, L6. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

The Hawking temperature is plotted as a function of the event horizon radius for and various values of .

Figure 1.

The Hawking temperature is plotted as a function of the event horizon radius for and various values of .

Figure 2.

The Hawking temperature is plotted with respect to the mass M for different values of , while the charge is set to .

Figure 2.

The Hawking temperature is plotted with respect to the mass M for different values of , while the charge is set to .

Figure 3.

The heat capacity is shown as a function of the event horizon for different values of the charge , with the parameters set fixed at .

Figure 3.

The heat capacity is shown as a function of the event horizon for different values of the charge , with the parameters set fixed at .

Figure 4.

The particle creation density is presented as a function of the frequency for a fixed value of and and different values of .

Figure 4.

The particle creation density is presented as a function of the frequency for a fixed value of and and different values of .

Figure 5.

The particle creation density is presented as a function of the frequency for different values of the NC parameter , with fixed values of and .

Figure 5.

The particle creation density is presented as a function of the frequency for different values of the NC parameter , with fixed values of and .

Figure 6.

The particle creation comparison (for bosons and fermions) is illustrated with respect to the frequency , while keeping , , and fixed.

Figure 6.

The particle creation comparison (for bosons and fermions) is illustrated with respect to the frequency , while keeping , , and fixed.

Figure 7.

The effective potential concerning for different values of NC parameter when , , , 2, 3 and

Figure 7.

The effective potential concerning for different values of NC parameter when , , , 2, 3 and

Figure 8.

The real andimaginary part of QNMs denoted as and are depicted concerning for , , and different values of Q.

Figure 8.

The real andimaginary part of QNMs denoted as and are depicted concerning for , , and different values of Q.

Figure 9.

Normalized deviations of the real and imaginary components of QNMs as functions of the NC parameter , for fixed values , , , across different overtone numbers n.

Figure 9.

Normalized deviations of the real and imaginary components of QNMs as functions of the NC parameter , for fixed values , , , across different overtone numbers n.

Figure 10.

Light trajectory in the presence of non–commutative framework for a charged black hole with and

Figure 10.

Light trajectory in the presence of non–commutative framework for a charged black hole with and

Figure 11.

The behaviour of the topological potential is shown against the r. The photonic radius is indicated by a red dashed line.

Figure 11.

The behaviour of the topological potential is shown against the r. The photonic radius is indicated by a red dashed line.

Figure 12.

The normalized vector field on the plane for , and . The black loop encircles the photonic sphere point .

Figure 12.

The normalized vector field on the plane for , and . The black loop encircles the photonic sphere point .

Figure 13.

The Gaussian curvature is depicted, with clear distinction between the regions corresponding to stable (pink) and unstable (purple) configurations. The analysis is carried out using the parameter values , , and .

Figure 13.

The Gaussian curvature is depicted, with clear distinction between the regions corresponding to stable (pink) and unstable (purple) configurations. The analysis is carried out using the parameter values , , and .

Figure 14.

Shadow radius with respect to NC parameter for and various values of charge Q.

Figure 14.

Shadow radius with respect to NC parameter for and various values of charge Q.

Figure 15.

The deflection angle is plotted with respect to the impact parameter b for and various values of the parameters and Q.

Figure 15.

The deflection angle is plotted with respect to the impact parameter b for and various values of the parameters and Q.

Figure 16.

Angular diameter with respect to NC parameter for based on M and of and . The yellow and orange areas represent the allowed and excluded regions of angular shadow, according to EHT observations.

Figure 16.

Angular diameter with respect to NC parameter for based on M and of and . The yellow and orange areas represent the allowed and excluded regions of angular shadow, according to EHT observations.

Table 1.

QNMs of scalar perturbation of Reissner–Nordström black hole for different , . The multipole and and corresponding overtones.

Table 1.

QNMs of scalar perturbation of Reissner–Nordström black hole for different , . The multipole and and corresponding overtones.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

,

|

|

0.29162-0.09805i |

0.29172-0.09814i |

0.29204-0.09844i |

0.29255-0.09895i |

0.29323-0.09966i |

|

0.26277-0.30755i |

0.26307-0.30773i |

0.26395-0.30829i |

0.26537-0.30931i |

0.26722-0.31086i |

|

|

0.48402-0.09685i |

0.48410-0.09697i |

0.48431-0.09731i |

0.48464-0.09789i |

0.48510-0.09868i |

|

0.46404-0.29595i |

0.46424-0.29627i |

0.46481-0.29722i |

0.46571-0.29881i |

0.46685-0.30106i |

|

0.43257-0.50366i |

0.43297-0.50411i |

0.43412-0.50547i |

0.43594-0.50780i |

0.43824-0.51116i |

|

|

0.48402-0.09685i |

0.48412-0.09695i |

0.48440-0.09724i |

0.48485-0.09772i |

0.48548-0.09838i |

|

0.46404-0.29595i |

0.46424-0.29622i |

0.46482-0.29701i |

0.46574-0.29833i |

0.46694-0.30021i |

|

0.43257-0.50366i |

0.43293-0.50403i |

0.43399-0.50516i |

0.43568-0.50710i |

0.43785-0.50990i |

Table 2.

The photon sphere radius for different values of the parameter and charge Q.

Table 2.

The photon sphere radius for different values of the parameter and charge Q.

|

Q = 0.1 |

Q = 0.2 |

Q = 0.3 |

Q = 0.4 |

| 0.0 |

2.99332 |

2.97309 |

2.93875 |

2.88924 |

| 0.1 |

2.99332 |

2.9731 |

2.93876 |

2.88927 |

| 0.2 |

2.99332 |

2.97312 |

2.93881 |

2.88936 |

| 0.3 |

2.99332 |

2.97314 |

2.93887 |

2.88949 |

| 0.4 |

2.9933 |

2.97315 |

2.93895 |

2.88966 |

| 0.5 |

2.99326 |

2.97315 |

2.93903 |

2.88986 |

| 0.6 |

2.99318 |

2.97312 |

2.93908 |

2.89006 |

| 0.7 |

2.99304 |

2.97304 |

2.93911 |

2.89025 |

| 0.8 |

2.99283 |

2.97289 |

2.93908 |

2.89041 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).