Submitted:

20 June 2025

Posted:

20 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

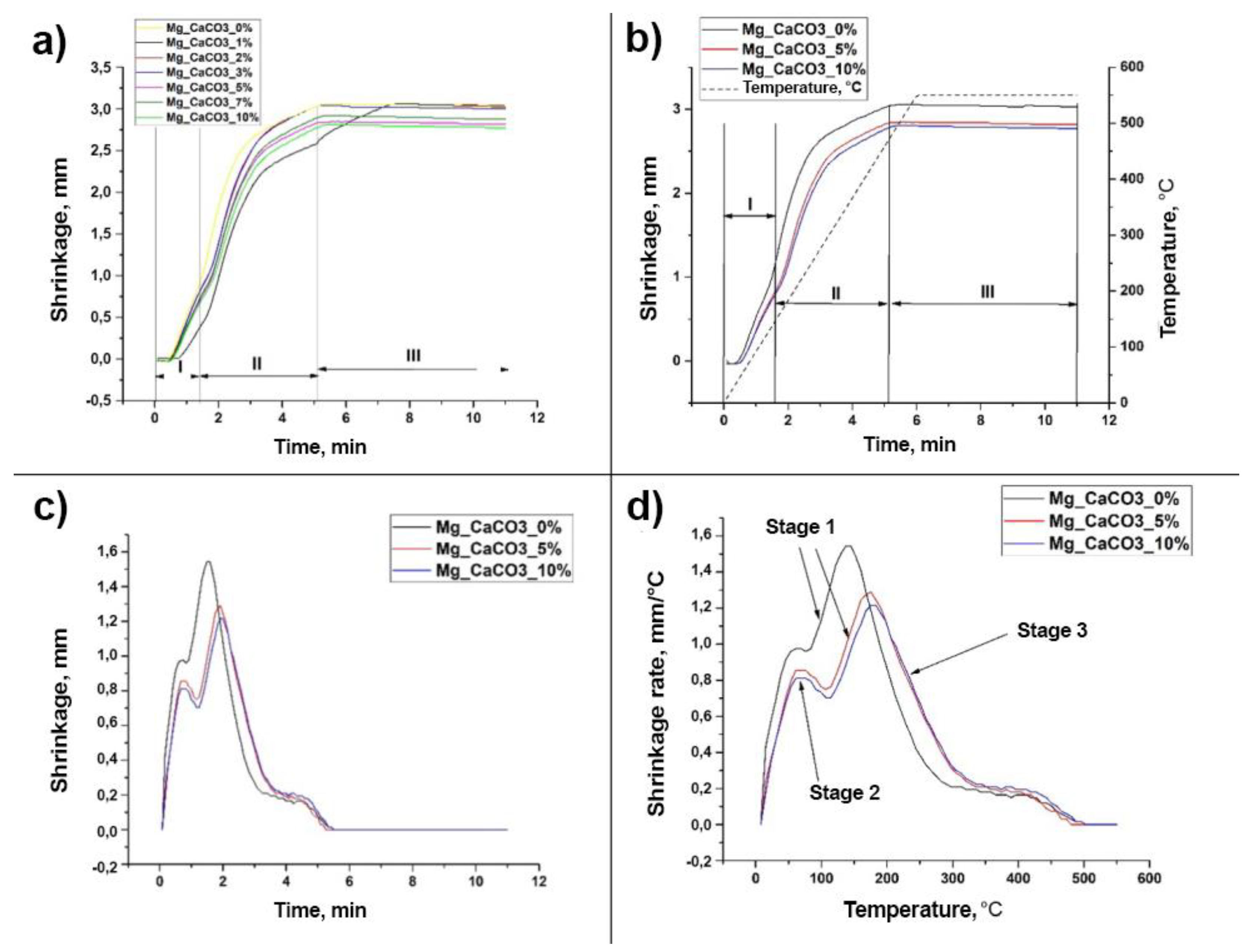

3.1. SPS Process Characterization

3.2. Coatings Composition and Morphology

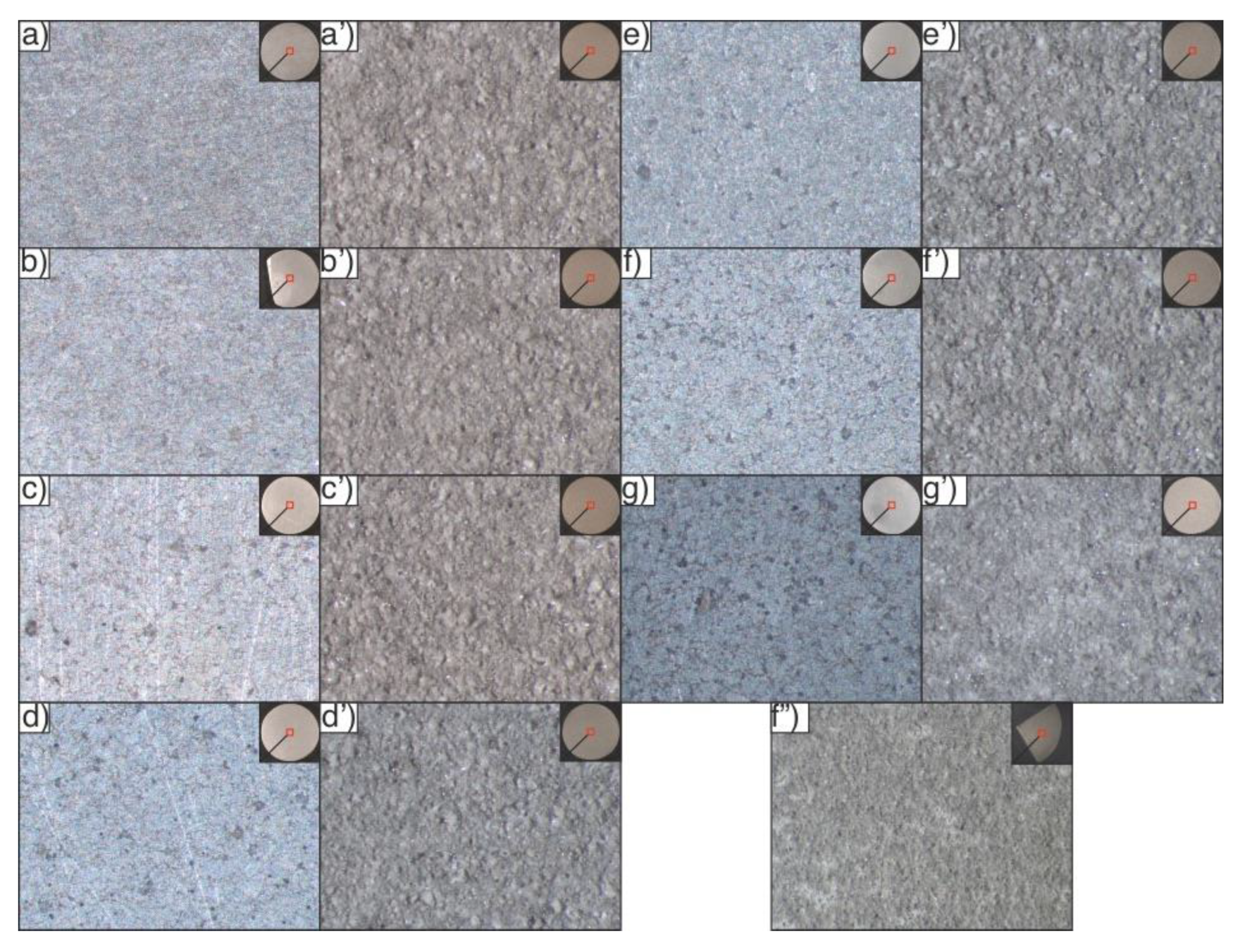

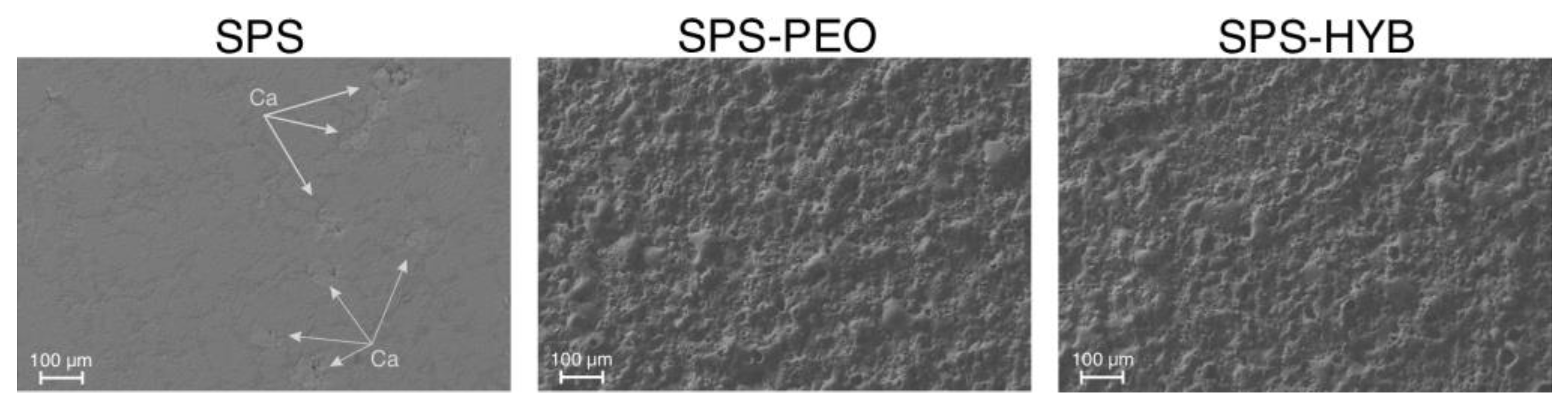

3.3. Coating Morphology

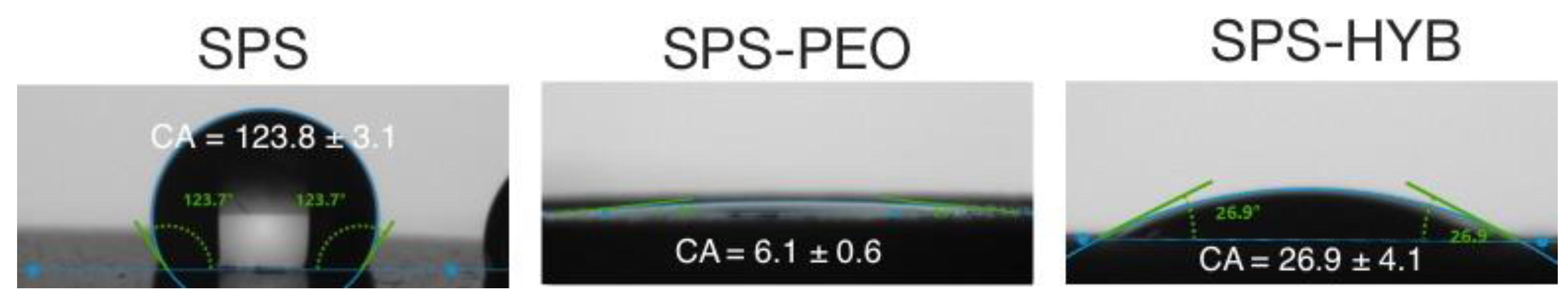

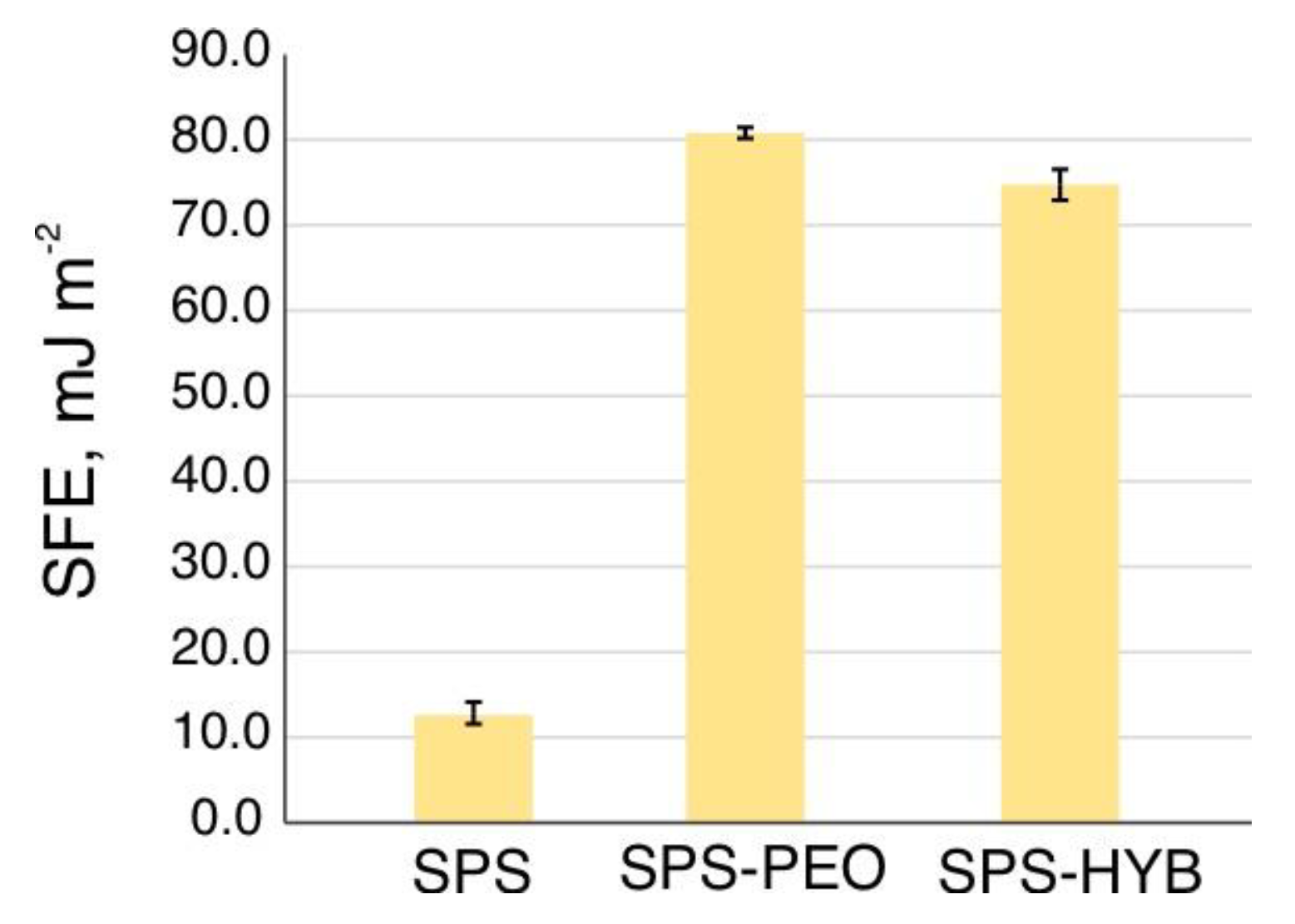

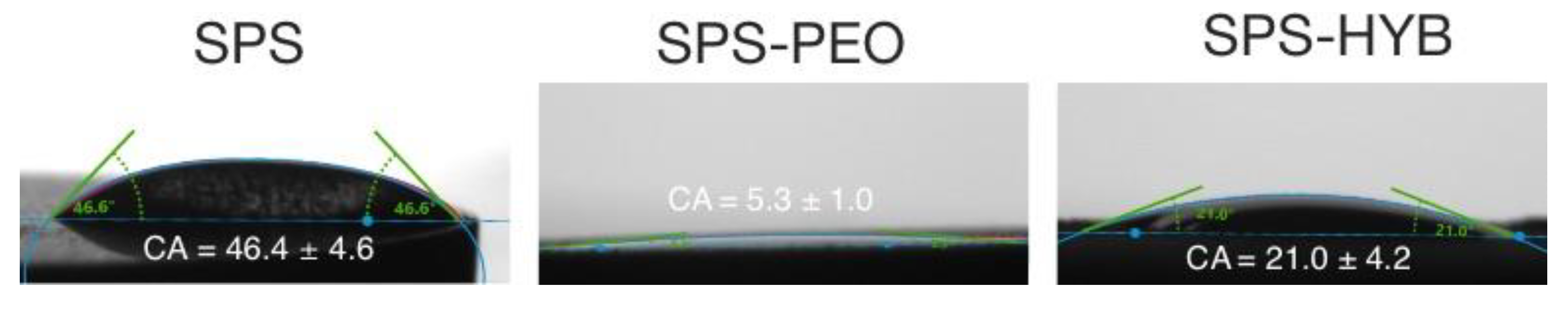

3.4. Coatings Wettability and Surface Free Energy

3.5. Coatings Mechanical Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IAIs | Implant-associated infections |

| SPS | Spark plasma sintering |

| PEO | Plasma electrolytic oxidation |

| HA | Hydroxyapatite |

| MK-7 | Menaquinone-7 (Vitamin K2) |

| PDA | Polydopamine |

| HYB | Hybrid |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| EDS | Energy dispersive spectroscopy |

| OSP | Optical surface profiling |

| SBF | Simulated body fluid |

| SFE | Surface free energy |

| OWRK | Owens-Wendt-Rabel-Kaelble method |

| CA | Contact angle |

| IR | Infrared Spectroscopy |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

References

- Staiger, M.P.; Pietak, A.M.; Huadmai, J.; Dias, G. Magnesium and Its Alloys as Orthopedic Biomaterials: A Review. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 1728–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Z.; Ni, R.; Wang, J.; Lin, X.; Fan, D.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, T.; Zheng, Y.; Cai, H.; Liu, Z. Practical Strategy to Construct Anti-Osteosarcoma Bone Substitutes by Loading Cisplatin into 3D-Printed Titanium Alloy Implants Using a Thermosensitive Hydrogel. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 4542–4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.N.; Xie, X.H.; Li, N.; Zheng, Y.F.; Qin, L. In Vitro and in Vivo Studies on a Mg–Sr Binary Alloy System Developed as a New Kind of Biodegradable Metal. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 2360–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzi, E.A.; Tibbitt, M.W. Additive Manufacturing of Precision Biomaterials. Adv. Mater. 2019, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papynov, E.K. , Mayorov V.Yu., Portnyagin A.S., Shichalin O.O., Kobylyakov S.P., Kaidalova T.A., Nepomnyashiy A.V., Sokol׳nitskaya T.A., Zub Yu.L., Avramenko V.A. Application of carbonaceous template for porous structure control of ceramic composites based on synthetic wollastonite obtained via Spark Plasma Sintering. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Papynov, E.K. , Shichalin O.O., Apanasevich V.I., Afonin I.S., Evdokimov I.O., Mayorov V.Yu., Portnyagin A.S., Agafonova I.G., Skurikhina Yu.E., Medkov M.A. Synthetic CaSiO3 sol-gel powder and SPS ceramic derivatives: “In vivo” toxicity assessment. Prog. Nat. Sci.: Mat. Int. 2019, 29, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papynov, E.K. , Shichalin O.O., Apanasevich V.I., Portnyagin A.S., Mayorov V.Yu, Buravlev I.Yu, Merkulov E.B., Kaidalova T.A., Modin E.B., Afonin I.S., Evdokimov I.O., Geltser B.I., Zinoviev S.V., Stepanyugina A.K., Kotciurbii E.A., Bardin A.A., Korshunova O.V. Sol-gel (template) synthesis of osteoplastic CaSiO3/HAp powder biocomposite: “In vitro” and “in vivo” biocompatibility assessment. Powd. Tech. 2020, 367, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, A.; Bordbar-Khiabani, A.; Warchomicka, F.; Sommitsch, C.; Yarmand, B.; Zamanian, A. PEO/Polymer Hybrid Coatings on Magnesium Alloy to Improve Biodegradation and Biocompatibility Properties. Surf. Interfaces. 2023, 36, 102495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Chang, J. Structure and Properties of Hydroxyapatite for Biomedical Applications. In Hydroxyapatite (Hap) for Biomedical Applications; Elsevier, 2015; pp. 3–19.

- Zehra, T.; Patil, S.A.; Shrestha, N.K.; Fattah-alhosseini, A.; Kaseem, M. Anionic Assisted Incorporation of WO3 Nanoparticles for Enhanced Electrochemical Properties of AZ31 Mg Alloy Coated via Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 916, 165445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrabal, R.; Matykina, E.; Viejo, F.; Skeldon, P.; Thompson, G.E.; Merino, M.C. AC Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation of Magnesium with Zirconia Nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 254, 6937–6942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daroonparvar, M.; Yajid, M.A.M.; Yusof, N.M.; Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R.; Hamzah, E.; Mardanikivi, T. Deposition of Duplex MAO Layer/Nanostructured Titanium Dioxide Composite Coatings on Mg–1%Ca Alloy Using a Combined Technique of Air Plasma Spraying and Micro Arc Oxidation. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 649, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseem, M.; Fatimah, S.; Nashrah, N.; Ko, Y.G. Recent Progress in Surface Modification of Metals Coated by Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation: Principle, Structure, and Performance. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 117, 100735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashtalyar, D.V.; Nadaraia, K.V.; Plekhova, N.G.; Imshinetskiy, I.M.; Piatkova, M.A.; Pleshkova, A.I.; Kislova, S.E.; Sinebryukhov, S.L.; Gnedenkov, S.V. Antibacterial Ca/P-Coatings Formed on Mg Alloy Using Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation and Antibiotic Impregnation. Mater. Lett. 2022, 317, 132099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswarlu, B.; Sunil, B.R.; Kumar, R.S. Magnesium Based Alloys and Composites: Revolutionized Biodegradable Temporary Implants and Strategies to Enhance Their Performance. Materialia 2023, 27, 101680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, F.; Hornez, J.-C.; Blanchemain, N.; Neut, C.; Descamps, M.; Hildebrand, H.F. Antibacterial Activation of Hydroxyapatite (HA) with Controlled Porosity by Different Antibiotics. Biomol. Eng. 2007, 24, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, A.C.; Wasilewski, G.B.; Rapp, N.; Forin, F.; Singer, H.; Czogalla-Nitsche, K.J.; Schurgers, L.J. Menaquinone-7 Supplementation Improves Osteogenesis in Pluripotent Stem Cell Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Front. cell dev. biol. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, W.; Liu, L.; Liu, L.; Chen, J.; Duan, L.; Li, Y.; Li, S. Vitamin K2 (MK-7) Attenuates LPS-Induced Acute Lung Injury via Inhibiting Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Ferroptosis. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0294763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, S.M.; O’Neill, L.; Behbahani, S.B.; Tzeng, J.; Jeray, K.; Kennedy, M.S.; Cross, A.W.; Tanner, S.L.; DesJardins, J.D. Efficacy of a Plasma-Deposited, Vancomycin/Chitosan Antibiotic Coating for Orthopaedic Devices in a Bacterially Challenged Rabbit Model. Materialia 2021, 17, 101122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, A.; Horne, A.; Gamble, G.; Mihov, B.; Reid, I.R.; Bolland, M. Ten Years of Very Infrequent Zoledronate Therapy in Older Women: An Open-Label Extension of a Randomized Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020, 105, e1641–e1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Qin, H.; Zeng, P.; Hou, J.; Mo, X.; Shen, G.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Wan, G. Metal-Organic Zn-Zoledronic Acid and 1-Hydroxyethylidene-1,1-Diphosphonic Acid Nanostick-Mediated Zinc Phosphate Hybrid Coating on Biodegradable Zn for Osteoporotic Fracture Healing Implants. Acta Biomater. 2023, 166, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, W.; Shao, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wu, W. Mussel Patterned with 4D Biodegrading Elastomer Durably Recruits Regenerative Macrophages to Promote Regeneration of Craniofacial Bone. Biomaterials 2021, 276, 120998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, M.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Xie, C.; et al. Polydopamine-Mediated Graphene Oxide and Nanohydroxyapatite-Incorporated Conductive Scaffold with an Immunomodulatory Ability Accelerates Periodontal Bone Regeneration in Diabetes. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 18, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barati Darband, Gh.; Aliofkhazraei, M.; Hamghalam, P.; Valizade, N. Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation of Magnesium and Its Alloys: Mechanism, Properties and Applications. J. Magnes. Alloy 2017, 5, 74–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashtalyar, D. V.; Imshinetskiy, I. M.; Kashepa, V. V.; Nadaraia, K. V.; Piatkova, M. A.; Pleshkova, A. I.; Fomenko, K. A.; Ustinov, A. Yu; Sinebryukhov, S. L.; Gnedenkov, S. V. Effect of Ta2O5 nanoparticles on bioactivity, composition, structure, in vitro and in vivo behavior of PEO coatings on Mg-alloy. J. Magnes. Alloy 2024, 12, 2360–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R. The Contact Angle in Capillarity. Physics of Fluids 2006, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, D.K.; Wendt, R.C. Estimation of the Surface Free Energy of Polymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1969, 13, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasper, J.J. The Surface Tension of Pure Liquid Compounds. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1972, 1, 841–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatkova, M.A.; Nadaraia, K.V.; Ponomarenko, A.; Manzhulo, I.; Gerasimenko, M.S.; Pleshkova, A.I.; Belov, E.A.; Imshinetskiy, I.M.; Fomenko, K.; Osmushko, I.; et al. Hybrid Surface Layers with Antibacterial and Anti-Inflammatory Activity for Implants Materials. J. Magnes. Alloy 2025. [CrossRef]

- Pérez Zapata, K.; Lenis, J.A.; Rico, P.; Ribelles, J.L.G.; Bolívar, F.J. Determination of Synergistic Effect between Roughness and Surface Chemistry on Cell Adhesion of a Multilayer Si - Hydroxyapatite Coating on Ti6Al4V Obtained by Magnetron Sputtering. Thin Solid Films 2022, 760, 139489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerebours, A.; Vigneron, P.; Bouvier, S.; Rassineux, A.; Bigerelle, M.; Egles, C. Additive Manufacturing Process Creates Local Surface Roughness Modifications Leading to Variation in Cell Adhesion on Multifaceted TiAl6V4 Samples. Bioprinting 2019, 16, e00054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zysset, P.K.; Edward Guo, X.; Edward Hoffler, C.; Moore, K.E.; Goldstein, S.A. Elastic Modulus and Hardness of Cortical and Trabecular Bone Lamellae Measured by Nanoindentation in the Human Femur. J. Biomech. 1999, 32, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokubo, T.; Kim, H.-M.; Kawashita, M. Novel Bioactive Materials with Different Mechanical Properties. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 2161–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, C.; Oshida, Y.; Lima, J.; Muller, C. Relationship between Surface Properties (Roughness, Wettability and Morphology) of Titanium and Dental Implant Removal Torque. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2008, 1, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fronzi, M.; Assadi, M.H.N.; Hanaor, D.A.H. Theoretical Insights into the Hydrophobicity of Low Index CeO2 Surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 478, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassie, A.B.D.; Baxter, S. Wettability of Porous Surfaces. Transactions of the Faraday Society 1944, 40, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadi, S.S.; Aliofkhazraei, M.; Barati Darband, Gh.; Abolhasani, A.; Sabour Rouhaghdam, A. Corrosion and Wettability of PEO Coatings on Magnesium by Addition of Potassium Stearate. J. Magnes. Alloy 2017, 5, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallab, N.J.; Bundy, K.J.; O’Connor, K.; Moses, R.L.; Jacobs, J.J. Evaluation of Metallic and Polymeric Biomaterial Surface Energy and Surface Roughness Characteristics for Directed Cell Adhesion. Tissue Eng. 2001, 7, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallab, N.; Bundy, K.; O’Coonor, K.; Clark, R.; Moses, R. Surface Charge, Biofilm Composition and Cellular Morphology as Related to Cellular Adhesion to Biomaterials. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1995 Fourteenth Southern Biomedical Engineering Conference; IEEE; pp. 81–84.

- PeŠŠková, V.; Kubies, D.; Hulejová, H.; Himmlová, L. The Influence of Implant Surface Properties on Cell Adhesion and Proliferation. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Med. 2007, 18, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Designation |

|---|---|

| Bare SPS-produced sample PEO coating |

SPS SPS-PEO SPS-HYB |

| PEO coating with vancomycin, menaquinone-7, zoledronate, PDA |

| Element | Designation |

|---|---|

| P Ca Mg Na |

29.4 28.5 21.1 12.6 5.9 2.5 |

| Si Other |

| Parameter | CaCO3 content in SPS-sample, wt.% | ||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 10 | |

| Sa (µm) | 4.8±0.4 | 5.2±0.1 | 5.5±0.8 | 5.3±0.1 | 6.4±0.5 | 6.4±0.6 | 5.9±0.3 |

| Sq (µm) | 6.3±0.6 | 6.9±0.4 | 7.1±1.0 | 6.8±0.1 | 8.2±0.7 | 8.3±0.9 | 7.6±0.3 |

| Sample | θ, ° | γsd, mJ/m2 | γsp, mJ/m2 | γs, mJ/m2 |

| H2O | ||||

| SPS | 123.8±3.08 | 12.85±1.63 | 0.04±0.01 | 12.86±1.67 |

| SPS-PEO | 6.1±0.6 | 50.19±0.12 | 30.62±0.09 | 80.81±0.22 |

| SPS-HYB | 26.9±4.1 | 49.22±0.60 | 25.57±1.68 | 74.79±4.39 |

| Sample | Wear (mm/(N m) |

|---|---|

| SPS | (4.7±2.3) · 10-3 |

| SPS-PEO | (4.6±1.0) · 10-2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).