1. Introduction

Obese patients suffer from a high prevalence of serious obesity-related illnesses, including diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart disease, stroke, sleep apnea, and cancer, and impose

$147 billion in costs on the healthcare system annually in the US. Obesity in the United States was 40.3% from 2017 to March 2020. It is predicted that by 2030, nearly 1 in 2 adults will have obesity [

1]. Nationally, severe obesity is likely to become the most common BMI category among women, non-Hispanic Black adults, and low-income adults [

1]. In addition, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of worldwide morbidity, disability, and death [

2]. On average, one American dies every 33 seconds from cardiovascular disease. Heart disease cost approximately

$252.2 billion between 2019 and 2020 in the US [

3].

The tragedies of delayed weight loss include obesity-induced illnesses such as type II diabetes and comorbidities, including coronary artery disease, hypertension, elevated blood lipids, fatty liver, and painful neuropathies. An extensive review and meta-analysis determined statistically significant associations between obesity and overweight (BMI > 25) and the incidence of type II diabetes, all cardiovascular diseases (hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, pulmonary embolus, except congestive heart failure), all cancers (except esophageal, pancreatic, and prostate cancers), asthma, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, and chronic back pain [

4].

The non-obese population that is overweight relative to themselves (approximately 10% over their normal, low adult weight) will likely also benefit from weight loss. This study addresses the potential physiological, psychological, and preventative benefits of weight loss in a non-obese population. This observational study aims to demonstrate the high efficacy of compounded semaglutide for weight loss in normal to overweight patients and presents anecdotal evidence of physiological and psychological improvements in this lesser-studied population.

Participants may benefit from weight loss, improved metabolic health, and enhanced overall well-being through structured medical supervision and available nutritional support. The study may also contribute to a better understanding of the effectiveness and safety of semaglutide in individuals who have struggled with weight loss through conventional methods. From a societal perspective, the findings could help refine elective weight management practices and provide insights into the off-label use of semaglutide. Additionally, the study may support more informed decision-making for healthcare providers and patients considering similar treatments. Overall, the research aims to advance knowledge in medical weight management while promoting safe and effective treatment approaches.

Many Americans strive for weight loss and maintenance. The glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogs have proven to be very effective in weight loss for the obese population. Overweight, non-obese patients also strongly desire to return to their normal adult weight. I propose that modest weight gain (8–25 pounds), generally 5–15% of a person’s stable, low adult weight, should be viewed as a person being “overweight” relative to themselves. Gains above, and returning to their “normal” lower weight, likely correlate with elevations or decreases in cardiovascular disease risk factors [

20,

21]. A method for determining a person’s target/goal weight is also proposed, along with an accompanying “success zone.”

1.1. The Current State of Research

Human studies have observed that calorie restriction (CR) protects against multiple atherosclerotic risk factors [

5]. Calorie restriction is defined as reducing caloric intake without depriving essential nutrients [

6] and results in changes in molecular processes associated with aging, including DNA methylation (DNAm) [

7,

8,

9]. A moderate CR diet has improved multiple cardiometabolic risk factors in healthy, young, and middle-aged non-obese men and women, similar to effects seen in weight loss studies involving individuals with obesity [

2]. A post hoc analysis of blood samples from the same group found that CR slowed the pace of aging [

7]. Moderate and other calorie-restricted diets may promote anti-aging adaptations and have been shown to increase healthy lifespans in multiple species [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. All the above considerations reinforce the importance of individuals maintaining their low, normal weight.

1.2. Specific Aims of the Study

To evaluate the effectiveness of compounded semaglutide for weight loss.

To study the effects of compounded semaglutide in healthy individuals who are of normal weight or overweight (BMI < 29.9).

To evaluate safety, efficacy, and the extent of weight loss with likely consequential health benefits.

To propose a novel method for declaring the ideal or target weight that accounts for differences in body composition, bone structure, and sex. Achieving this target weight is also proposed as a metric for program success.

1.3. The Primary Research Question

What is the change in weight following a non-obese (BMl < 29.9) patient taking semaglutide over 3-24 months?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study employed an internal, prospective, non-randomized, non-blinded, dynamic cohort observational design. It was conducted at Dr. Sharon Giese’s aesthetic medicine practice in New York City, beginning in May 2022 and ongoing, with a projected minimum end date of May 15, 2025. Ethical guidelines were adhered to throughout. The primary aim was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of compounded subcutaneous semaglutide in promoting weight loss and weight maintenance among a non-obese adult population (BMI < 29.9).

2.2. Intervention Protocol

The single intervention in this study was the administration of compounded semaglutide via subcutaneous injection. Participants self-administered the drug at dosages aligned with FDA-approved guidelines. The intervention was part of a structured elective weight loss program that included weekly weight tracking, adherence to regular coaching, continuous medical oversight for safety and adherence, weekly follow-ups (via email, in-person, or virtually), and detailed education on semaglutide’s risks, side effects, and management strategies.

Patients remained on semaglutide until they reached their target weight. Afterward, the dose was tapered based on individual weight maintenance success. Participants could discontinue the medication at any time. The protocol for compounded semaglutide with cyanocobalamin (B12) (5/0.5 mg/1 cc) required injecting 0.25 mg (5 units) subcutaneously into the thigh or abdomen once weekly. Participants checked in with the office or a nutritional coach to titrate the dose for appetite suppression. Dosing and timing were adjusted as necessary to achieve appetite suppression and weight loss. Weekly check-ins encouraged compliance. The medication was sourced from an accredited 503A/503B pharmacy.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included, participants had to meet the following criteria: be an adult aged 21 years or older; have been unable to reach target weight via other methods; provide informed consent for the treatment protocol, including weekly weigh-ins and communication; and show willingness to self-administer semaglutide off-label with full understanding of the risks. All genders were eligible to participate, and there were no restrictions related to socioeconomic status. The following individuals were excluded from the study: pregnant or breastfeeding women; individuals with type 1 or type 2 diabetes; those currently using metformin or with other chronic conditions; individuals with a history of eating or severe gastrointestinal disorders; and those with known adverse reactions to GLP-1 agonists. Eligible participants were required to have a BMI between 18.5 and 40 or demonstrate weight concerns relative to their personal health goals.

2.4. Sample Size and Recruitment

A total of 400 adults were recruited through internal communication methods with existing patients. No public advertisements or mass recruitment campaigns were used. The sample size was informed by a comparable two-year randomized controlled trial on caloric restriction in non-obese adults (n = 220) [

2]. Both men and women aged 21–85 years were included.

2.5. Informed Consent

Participants gave written informed consent after receiving comprehensive information about the study objectives, treatment procedures, potential benefits and risks, and their voluntary right to withdraw at any time. The consent process included written materials, verbal discussions, and video-based education. There was no financial inducement; all participants were self-funded, and no insurance claims were filed. HIPAA compliance was strictly maintained, and signed consent forms were stored securely.

2.6. Data Collection and Follow-Up

Data were collected using multiple methods: weekly self-reporting of weight (including photographic documentation of digital scale readings), structured intake and follow-up forms, visual verification by the physician during regular appointments, and review of medical records for adherence and adverse events. Periodic surveys assessed satisfaction, well-being, and treatment experience. Participants also completed intake forms that captured medical history, sleep patterns, alcohol consumption, psychiatric or diabetic medication use, and body weight history. A target weight was determined collaboratively between the patient and physician, typically above the patient’s historical low weight to ensure attainability.

2.7. Success Zone and Weight Goals

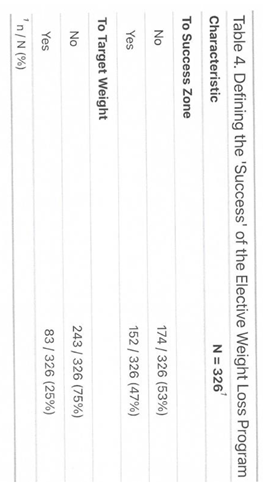

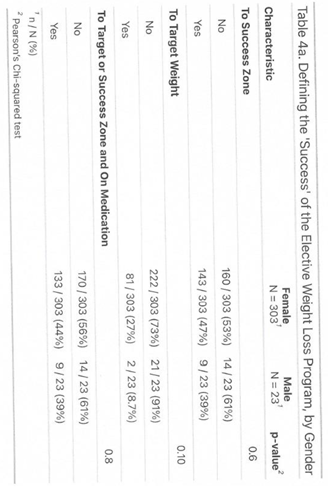

A unique “Success Zone” was established for each participant. This range—defined as achieving 75% or more of the desired weight loss—allowed a buffer for acceptable weight regain. It also established a threshold for reinitiating treatment if weight maintenance failed. For example, a participant with a starting weight of 150 pounds and a target weight of 130 pounds would have a success zone defined as 130–135 pounds. This goal-setting strategy emphasized patient involvement and realistic, sustainable outcomes rather than rigid adherence to BMI charts.

2.8. Monitoring and Safety Measures

The practice ensured 24/7 access to Dr. Giese for medical support. Commonly expected side effects—such as nausea, gastrointestinal discomfort, or temporary appetite suppression—were discussed thoroughly during intake and monitored through regular follow-ups. Participants received education on managing side effects, and dose adjustments were made in response to complications or slow weight loss progress. A small group of 29 obese patients were transitioned to tirzepatide due to side effects or plateauing while on semaglutide. This subset was not analyzed separately but will be followed in future phases.

2.9. Data Management and Confidentiality

All participant data were anonymized using unique ID codes. Each participant was assigned a unique number. The patient's name and number were stored on the practice's private server, which is backed up on a secure cloud system with firewalls. Confidential information was stored and backed up using end-to-end encryption. Terminals were password-protected, with access restricted to the principal investigator and authorized research staff. Electronic data was maintained in encrypted, password-protected systems with limited access. Physical documents were stored in locked cabinets within secure offices. Data analysis was conducted according to current ethical and legal standards. Data will be retained and eventually destroyed in accordance with those standards. HIPAA compliance protocols were strictly followed to ensure participant privacy and data integrity.

2.10. Risk and Benefit Analysis

The potential risks associated with participation in this study were minimal and included mild side effects such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation. Serious side effects may include pancreatitis, hypoglycemia, allergic reactions, gallbladder complications, and/or stomach paralysis. Risk assessments varied based on participant characteristics. Psychological risks may involve frustration or disappointment if the expected weight loss was not achieved. The principal investigator assessed basic psychological competency prior to enrollment, particularly regarding body dysmorphic disorders. If excessive or unanticipated psychological effects occurred during or after treatment, they were addressed immediately and individually. Any suicidal ideation was referred to the emergency department.

Participants potentially benefit from weight loss, improved metabolic health, and enhanced well-being through structured medical supervision and nutritional support. The study may also contribute to a deeper understanding of semaglutide’s safety and efficacy in individuals who have not succeeded with conventional weight loss methods. Its expansion to non-obese participants allows for exploration of related health benefits. From a societal standpoint, the findings could help refine elective weight management practices and provide insight into the off-label use of semaglutide. Additionally, the study may support informed decision-making for both healthcare providers and patients. Overall, the risk–benefit profile favors participation, given the low incidence of adverse events and the high potential for health improvements.

2.11. Patient-Reported Outcomes

The practice uses a body satisfaction scale from 1 to 6 (1 being extremely dissatisfied and 6 being extremely satisfied). Patients were asked to rate their current satisfaction with various body parts, such as height, weight, stomach, and overall size and shape. These data will be analyzed at a later date in conjunction with appropriate psychological expertise. The principal investigator did not evaluate whether semaglutide dosage correlated with appetite suppression or satisfaction with the treatment program.

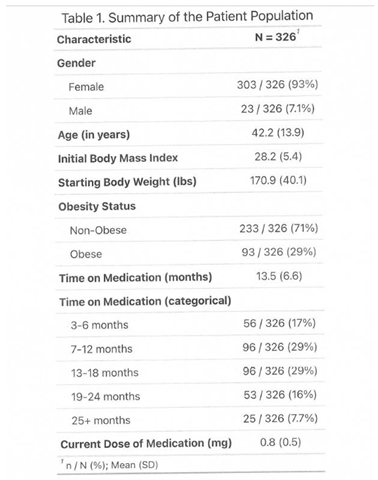

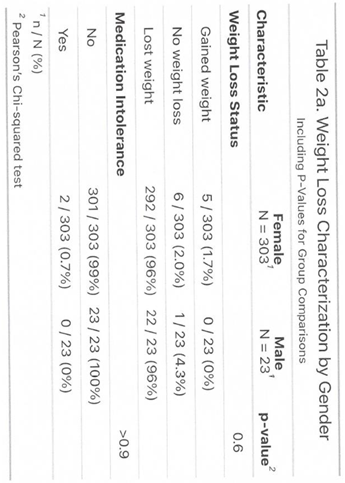

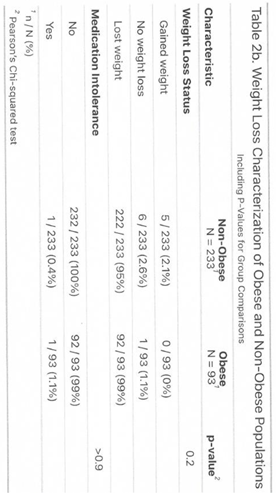

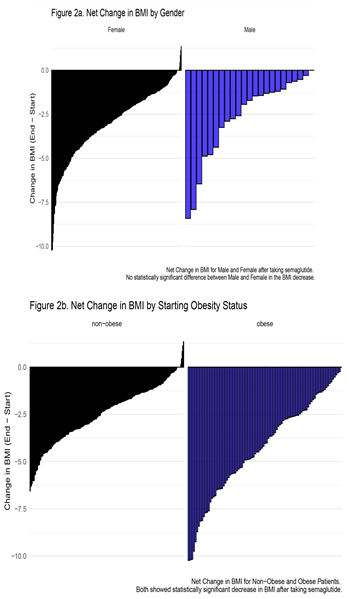

2.12. Participant Demographics and Follow-Up

The study population included 303 women and 23 men, ranging in age from 21 to 85 years. All participants had at least 12 weeks of follow-up, with some followed for up to 120 weeks. Most participants fell within the normal to overweight BMI range (<29.9). A smaller subgroup was classified as obese (BMI 30–35.5) but did not have diabetes or comorbid conditions. Many obese participants sought semaglutide through Dr. Giese’s practice after being denied access through primary care or insurance. They followed the same dosing and monitoring protocols as the non-obese group. This subgroup will be tracked separately due to the potential for different response patterns and a higher risk of weight regain.

4. Discussion

Most of the studies on weight loss and the risks of obesity are understandably conducted on the obese population. Those individuals are likely already in a diseased, inflammatory state and not a comparable population to those at a normal weight (BMI < 25) or even healthy, overweight, or non-diabetic people (BMI < 29.9). Notable weight loss in the obese population has conferred improved health benefits and reduced risk factors for coronary artery disease, hypertension, and lipid profiles [

2,

10,

46,

47,

48]. An extensive review and meta-analysis determined statistically significant associations between obesity and overweight (BMI > 25) and the incidence of type II diabetes, all cardiovascular diseases (hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, pulmonary embolus, except congestive heart failure), all cancers (except esophageal, pancreatic, and prostate cancers), asthma, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, and chronic back pain [

11]. Maintaining a healthy weight could be important in preventing this large disease burden and significantly reducing health expenditures. Obese patients suffer from a high prevalence of serious obesity-related illnesses, including diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart disease, stroke, sleep apnea, and cancer, and impose

$147 billion in costs on the healthcare system annually in the US [

2]. More recently, several STEP studies [

12] have demonstrated that the magnitude of weight loss reported in STEP trials offers the potential for clinically relevant improvement for individuals with obesity-related diseases [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

A recent, well-controlled study implementing moderate calorie restriction in non-obese men and women with a clinically normal baseline showed improvements in six cardiometabolic risk factors: reduction in LDL-C, increase in HDL-cholesterol concentration, reduced serum triglycerides, lower systolic blood pressure, reduction in BMI, and a reduction in Met syndrome Z-score and AUC insulin [

2]. Normal risk factors were already improved at the two-year post-implementation of the CR diet. The improvement in long-term cardiovascular risk was implied [

2]. The calorie restriction compliance was aided by intensive, weekly behavioral therapy and food and calorie calculation support. Without such support, compounded semaglutide may be a good alternative and adjunct to achieving calorie restriction and weight reduction. CR has been shown to reduce inflammatory markers TNF-α and CRP in non-obese humans [

11,

12]. Sustained CR was feasible in humans and sufficient to affect some potential modulation of longevity that CR has also induced in laboratory animal studies or adults [

37,

38,

39,

40]. This, in turn, likely diminishes risk factors for age-related cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and enhances human lifespan [

5,

21]. A recent report of two years of sustained CR in humans positively affected skeletal muscle quality, and gene expression changes induced by CR partially mediate the preservation of muscle strength [

11].

I propose that people in the traditionally normal weight population (BMI < 25) and non-diabetic, overweight adults (BMI < 29.9) will equally benefit from weight loss to a target weight, around their low weight as an adult, with the aid of semaglutide. Multiple cardiometabolic risk factors are reduced in both obese and non-obese populations with weight loss achieved by moderate calorie restriction [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Semaglutide has also been used as an adjunct to increase the magnitude and efficacy of weight loss with attendant medical benefits [

11]. I propose that the successful, efficacious weight loss in the non-obese population of this study, with the aid of semaglutide, improved cardiometabolic risk profiles as in the CALERIE study [

2].

As a body contour expert, I have used this target weight benchmark for over 20 years to establish an individual's "normal weight." When assessing all my body contour patients, I always ask about a person's adult high, low, and ideal body weight. In general, those values are quickly answered. It seems that most people intuitively know their "healthier" weight and set their ideal at a little higher than their lowest weight. Therefore, attaining a "target weight" is a benchmark for a program's weight loss success or effectiveness. Success or effectiveness has been expressed as a percent decrease from the start weight, a reduction in BMI, a decrease in waist circumference, improvements in health outcomes (blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and insulin sensitivity), and participants' satisfaction.

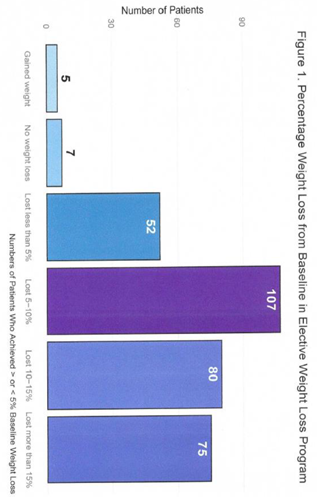

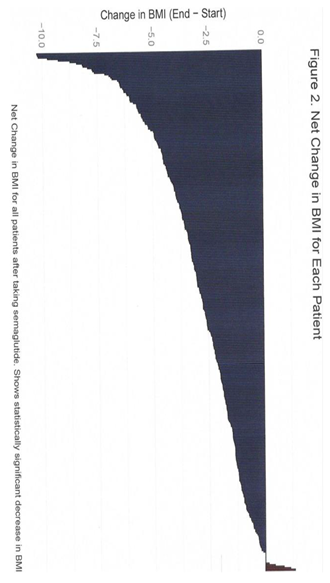

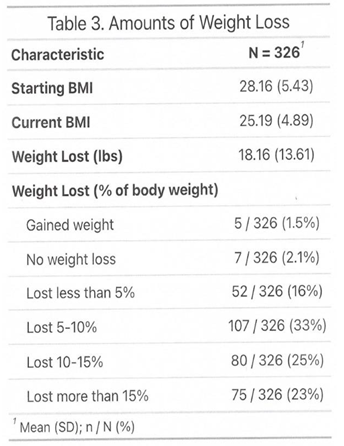

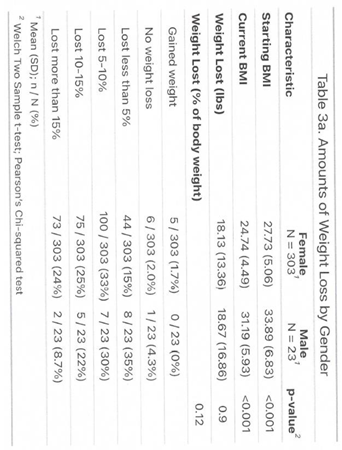

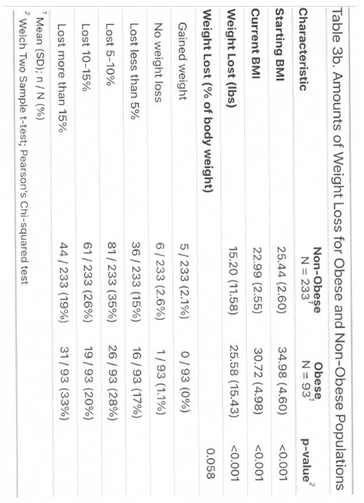

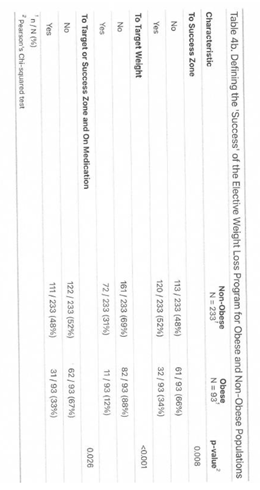

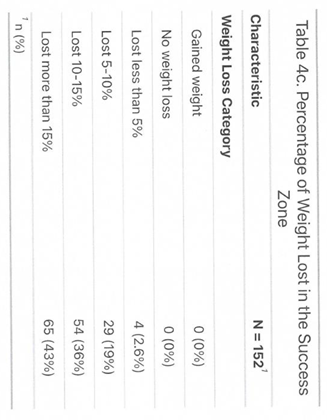

The results in this study are analyzed in three ways: statistically significant weight loss relative to themselves, the percent decrease in body weight loss at <5%, 5–10%, 10–15%, and >15%, and statistical decrease in the BMI. Patients who achieved and maintained 75% progress toward the target weight or, following attainment of the target weight, did not regain more than 25% of the weight loss, are designated in the "Success Zone." This target weight is patient-centric and patient-motivated. It does not rely on the BMI chart. Achieving 10% of body weight loss generally correlates with improved health profiles [

10]. However, obese and non-obese patients may have weight goals that are beyond that. In this case, the target weight is essential, as I recommend that patients stay on the medication until they reach the target. Just losing weight is not necessarily viewed as "success." To further justify using the target weight and "Success Zone," we compared the patients who achieved that status to typical milestones of success with weight loss medications and percent body weight loss. Seventy-nine percent of patients in the "Success Zone" have lost 10% or more of their start weight, and people with more minor total losses (<10%) had smaller weight-loss targets (Table 4c). Medical benefits have been noted with as little as 5% weight loss [

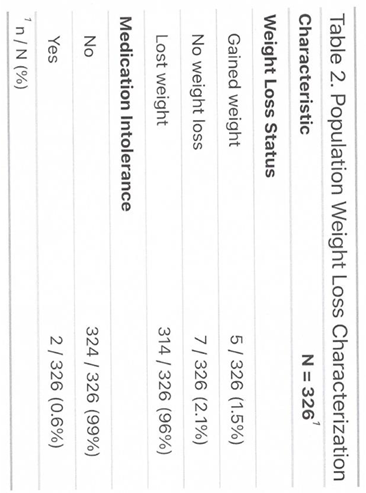

12]. Eighty-one percent of the study patients have achieved 5% or greater weight loss (Table 3).

Multiple studies have questioned the BMI stratification. While there are likely gross triage benefits today, the BMI scale was not intended for individualized clinical use but rather to define the average weight of a population [

21]. I use it simply as a benchmark and quantify the weight change within each individual in the study group. The fact that the BMI scale lacks overall clinical relevance supports my question about the ideal body weight for any given person. Determining the target weight was used as another benchmark of the success of any individual's weight loss and is intended to supplant the traditional standard BMI definitions of normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9) or overweight (BMI 25–29.9)

I have a unique window into an aging, very disciplined, accomplished, and generally healthy female population. Over the years, I have seen many patients struggle to maintain weight and/or achieve weight loss. They have many resources at their disposal and access to a multibillion-dollar weight loss industry. Their failure to achieve their weight goals motivated me to explore why. If it were easy to stay near a lower weight, more people would be there and not be trying to lose.

A prescription for weight loss is hardly one-size-fits-all. Western medicine generally prescribes “calorie restriction and exercise.” Anyone who has tried to lose weight and failed knows this is easier said than done. Longitudinal and population studies have shown that weight loss and maintenance in the obese population often fail over time [

22]. There is also high recidivism and minimal success for commercial and community-based weight loss programs [

23,

41]. A study evaluating only the most successful and overweight Weight Watchers® members found that 50% maintained at least 5% of their weight loss over five years [

24]. Weight loss interventions are generally multifaceted, costly, aggressive, and involve dramatic changes imposed on individuals—all of which may contribute to failure. Given the high failure rates, or the lack of transparency regarding actual success, there is a need for higher, more reproducible standards to evaluate weight loss.

The simple answer to high failure rates is that it is challenging to stay on a restricted calorie diet for a sustained period [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Weight loss generally takes longer than people expect to achieve. Then there is weight maintenance, which is usually considered equally as difficult [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Incredibly, weight gain is often ignored by primary care physicians until a person reaches an obese level. Even then, in the face of a diseased state—perhaps pre-diabetic—in many cases, no recommendation for treatment is made [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. Gradually, weight gain is often accepted as a natural part of aging. While many factors contribute to weight changes, one known factor is that muscle mass decreases with advancing age, particularly in women over 60. This should lead to weight reduction with age, not weight gain.

All the subjects in this observational study failed to achieve their ideal body weight by other means and opted to try compounded semaglutide to lose weight. An additional anecdotal comment, repeated by patients and likely contributing to the drug’s effectiveness, was the reduction of “food noise.” Some patients have opted to stay on a low dose (0.25–0.5 mg semaglutide weekly) as a maintenance dose to keep the food noise at bay. Recently, this has been described as “microdosing.” The food cue reactivity conceptual model is gaining credible scientific support [

42]. Evidence indicates that weight loss increases appetite sensations, particularly to upregulate appetite in women [

25].

This observational study indicated that the success of weight loss, aided by compounded semaglutide in non-obese individuals, was substantial. Ninety-six percent of the 326 subjects lost weight, with only one regaining weight after stopping the medication. Eighty-one percent of the total population achieved over 5% body weight loss, with nearly half of the patients still working toward their target weight. Eighteen and a half percent were lost to follow-up. I categorized the results by percent of weight loss, similar to the graded benchmarks of 5%, 10%, 15%, and above—used in obese populations—which are associated with escalating health benefits [

10]. The target is health improvement, including quality of life or healthspan. It is likely that a CR diet resulting in 5% to over 15% weight loss confers similar positive health outcomes by reducing obesity-induced risk factors. The addition of the “Success Zone” provides a more nuanced measure of the program’s effectiveness. Patients enter the Success Zone when they achieve and maintain at least 75% of their target weight loss goal. This benchmark is intended to encourage patients to reach their goals and remain alert to signs of weight regain. If they fall out of the zone, they should be vigilant before losing further progress or experiencing cyclical weight fluctuations.

The weight loss success occurred without infection or overdosing. I found patients to be very competent in managing multi-dose vials and self-administering injections. They were empowered by this autonomy and motivated to avoid side effects. As a result, overdosing—which would be both costly and physically uncomfortable—was not observed. I believe patients were highly motivated to succeed efficiently, which also encouraged them to discontinue the medication or maintain a very low dose of 0.25 mg every 7–14 days.

In the future, we may use Bluetooth-enabled scales to capture data in real time, eliminating the need for patients to photograph their digital weight readings and submit them manually. I expect this would result in more data points and help strengthen the dataset, which is currently partly self-reported. Since many participants were established patients in the practice, we also had the advantage of visually verifying weight updates during visits. We often recorded weight changes during appointments when patients had not submitted them, and these values were generally lower than prior reports. A placebo group of two is not ideal; however, we were unable to recruit more participants for that arm. We did not study whether semaglutide dose correlated with appetite suppression or overall satisfaction with the program. This feedback is currently being collected through a post-participation survey. It is also unclear whether adherence to the program’s guidelines—such as weekly follow-ups and dose adjustments—directly influenced weight loss outcomes. The survey may help clarify this in the future.

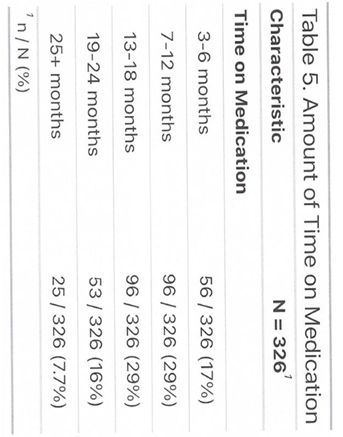

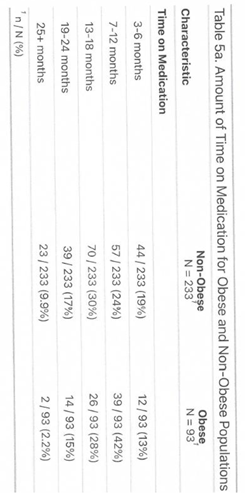

Dosing in this study was significantly lower than the dosing regimens recommended by Ozempic® and Wegovy® for obese patients, which typically increase to 2.4 mg weekly. The average dose for study participants was 0.84 mg weekly (range: 0.15–2.4 mg). At those doses, patients lost weight at a rate of one-half to two pounds per week. This was used as a predictive tool to estimate how long a patient might remain on the medication. I estimated that patients would stay on the medication for another 6–8 weeks to ensure a stable target weight before beginning a taper. The tapering protocol involved reducing the dose by 2–5 units, or 0.1–0.25 mg per week, as long as the weight remained stable. Some patients stopped medication upon reaching their goal. Given semaglutide’s long half-life (approximately one week), cessation naturally resulted in a taper over 5–6 weeks, requiring no intervention.

Some patients lost as much as 30 pounds with only 0.25–0.5 mg semaglutide weekly. In those cases, body size alone did not explain the need for lower doses. In general, I found that dosing needed to be customized. Some larger patients succeeded on low doses, while some smaller individuals required 1.25–1.5 mg weekly. A small subset advanced to 2.4 mg/week to reach their target weight. If weight loss plateaued at higher semaglutide doses, patients were transitioned to tirzepatide—29 out of 326 patients. I believe that individualized, lower-dose protocols helped reduce complications, especially the most problematic one: vomiting.

Anecdotal health benefits were also reported. One patient was able to discontinue one of two hypertensive medications. Another experienced a visible reduction in spider veins, possibly indicating improved venous return and reduced venous insufficiency. Additional patients reported increased energy and decreased joint pain. One participant’s sleep apnea resolved completely following a 35-pound weight loss. Prior studies have noted both positive and negative psychological outcomes [

26]. Psychological effects may not be tied solely to absolute weight loss. Viable study designs investigating psychological outcomes, subject selection, and intervention strategies are currently being explored for both obese and non-obese populations [

26].

Additionally, many patients expressed appetite suppression after taking semaglutide, which helped control their portion sizes. Once they learned portion adjustments, they tended to choose more nutritionally dense foods. Some scientists believe that obesity rates have surged in recent decades, at least in part due to the manipulation, ultra-processing, and declining quality of the food supply. Semaglutide appears to mitigate these challenges through improved portion control, offering a potential interim solution while broader societal issues related to food systems are addressed.

Overwhelmingly, in the current study, all patients reported improved body image and greater satisfaction with themselves. We will attempt to quantify these perceived psychological benefits in the future. One- and two-year follow-up data from a larger cohort will provide further insights into weight maintenance after discontinuation of semaglutide and the likelihood of patients resuming semaglutide if weight is regained. Given that over 40% of the U.S. adult population is obese, I believe that adults should not gain more than 10% above their lowest adult weight unless this is due to an identified medical condition.