1. Introduction

Obesity is considered a chronic disease affected by the interplay between genetics, environmental influences, and behaviors (Jensen et al., 2014; Sharma & Kushner, 2009). It is a major contributor to global morbidity and mortality and is also a significant risk factor for several chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and some malignancies (Ortega et al., 2016). One of the main concerns about the increase in obesity is its significant public health impact, which is directly through healthcare costs and indirectly through loss of productivity (Lehnert et al., 2013). The mortality attributed to obesity significantly increased by 156% from 1990 to 2019 according to the Global Burden of Disease study (Murray et al., 2020), mainly as a result of the higher incidence of such related comorbidities as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes. This global burden is reflected in the regional perspective as well. Approximately 43% of the Saudi population is classified as obese, which is higher than the global prevalence of around 30% (A. J. et al., 2014). Notably, the prevalence of diabetes among the Saudi population is among the highest in the world, with a significant proportion of these cases linked to obesity (Al-Rubeaan et al., 2018). This stark comparison underscores the urgent need for effective obesity management strategies in Saudi Arabia to mitigate these associated health risks.

Although BMI has been the standard way to define obesity and inform treatment decisions, it is beginning to be recognized that BMI is an imperfect surrogate for obesity severity. For its part, BMI fails to distinguish between fat and lean mass or to consider metabolic, functional, or psychological health risks that often accompany obesity. Indeed, the finding that some people with high BMI can be metabolically healthy and others with normal BMI can have substantial metabolic derangement (Wildman et al., 2008) raises a fundamental question on the role of lifestyle factors as risk determinants. This evolved into more sophisticated obesity classification systems.

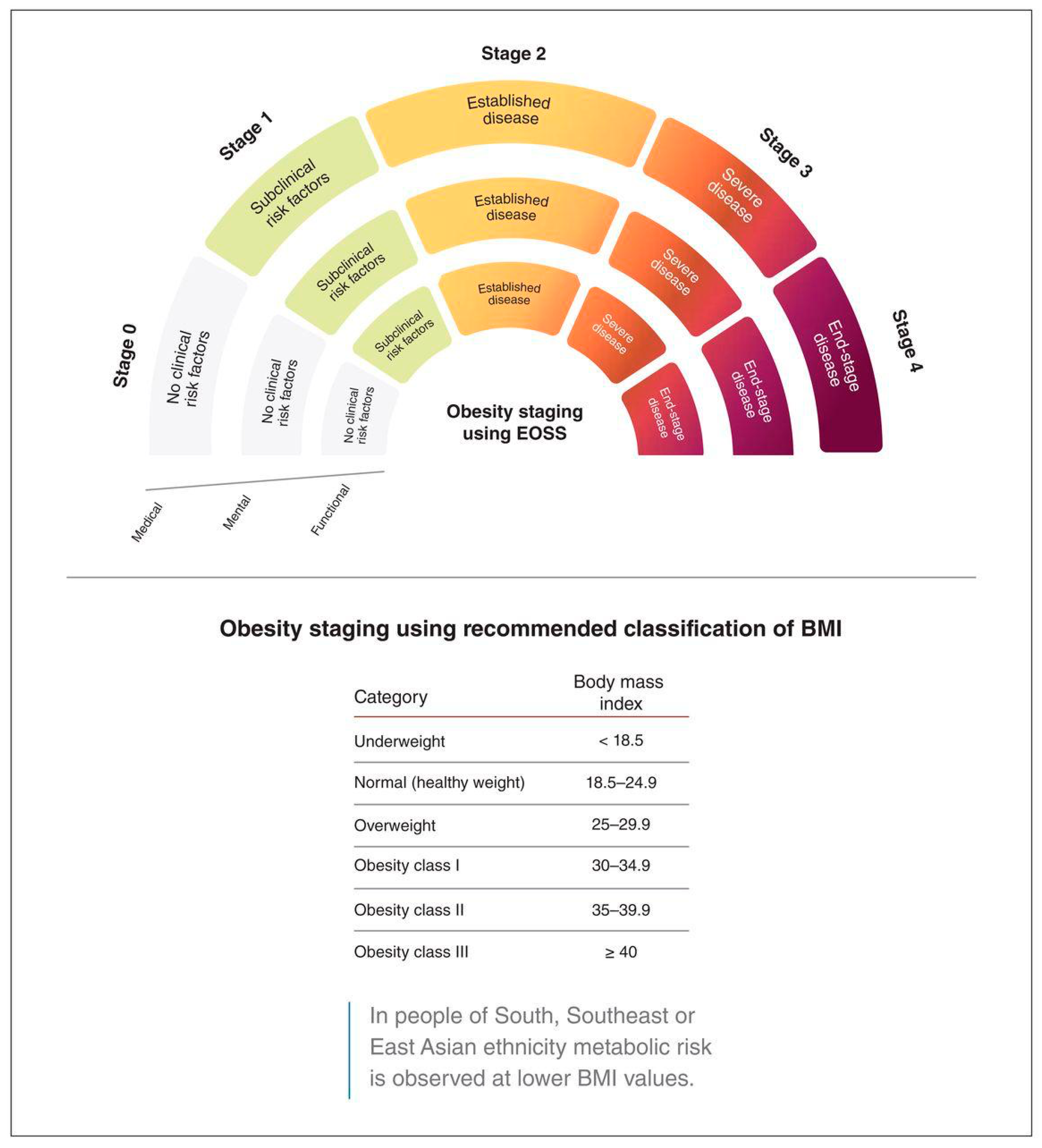

Several frameworks have been introduced to address the shortcomings of BMI, including the Waist-to-Hip Ratio, King’s Obesity Staging Criteria, and the Edmonton Obesity Staging System (EOSS) (Dobbie et al., 2023; Huxley et al., 2010). Among these, EOSS has gained recognition as a comprehensive model for obesity classification, as it encompasses the presence and severity of obesity-related comorbidities, functional limitations, and mental health conditions beyond body size (Canning et al., 2015; De Wolf et al., 2024; Kuk et al., 2011; Padwal et al., 2011).

The EOSS assigns patients into one of five stages (0–4) based on the extent of obesity-related health risk, informing clinical management (Swaleh et al., 2021). EOSS has been shown to serve as a better predictor of mortality and morbidity than BMI alone and may serve as a useful guide when determining the intensity of obesity interventions (Padwal et al., 2011).

Although EOSS has been the subject of numerous publications and research studies, there is limited information on its utility in clinical practice, particularly in primary care and Lifestyle Medicine Clinics. Primary care serves as the frontline of health service provision and is thus a vital setting for the introduction of structured approaches to obesity management (Atlantis et al., 2020).

Because of its acknowledgment of the importance of whole-person care—including aspects such as nutrition, physical activity, behavior change, and stress management—lifestyle medicine complements risk stratification models like EOSS by providing individualized, patient-centered interventions. This is particularly important in the Middle East, where there is a growing epidemic of obesity, especially in Gulf countries such as Saudi Arabia, where the prevalence of obesity is high. Understanding how EOSS can improve primary care-based obesity management strategies is crucial.

However, to our knowledge, few studies have investigated the integration of EOSS into clinical workflows within primary care-based lifestyle medicine clinics in this region.

This study aimed to describe the general characteristics of patients who visit the lifestyle medicine clinic at Wazarat Health Care Center, Prince Sultan Military Medical City, and to investigate whether the EOSS stages are associated with specific patient variables. The results can assist in promoting the incorporation of EOSS into routine care to improve obesity care and patient outcomes in primary care.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

A retrospective cross-sectional records-based study for patients served by the lifestyle medicine clinic at Prince Sultan Military Medical City- Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. This retrospective analysis was conducted on participants who presented at the lifestyle medicine clinic which focuses on motivated people with obesity who need to lose weight, as advised by their primary physicians. Patients undergo a complete biopsychosocial assessment, which is used to calculate the EOSS and receive management services accordingly. The management services include comprehensive gradual lifestyle changes, weight-loss medication, and, for those who require it, a referral for bariatric surgery (Konswa et al., 2023).

2.2. Study Participants

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria:

All patients aged 14 years or older who newly visited the clinic during 2023 from January 2023 to December 2023 with complete medical records were included in the study.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria:

Patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, pregnant individuals, those who are below 14 years old , and those older than 65 years were excluded from the study due to lifestyle medicine clinic policy since these individuals are served in different clinics in Wazarat health care center: type 2 diabetes patients are managed by the chronic illness clinic, pregnant ladies are managed by the antenatal clinics, the pediatrics clinics manage those who are below 14 years old, and those who are above 65 years old are managed by the geriatrics clinics since these individuals have different and special management guidelines.

2.2.3. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 960 patients were enrolled in the study.

2.3. Data Collection

Demographic data, anthropometric data, laboratory data, and clinical assessments were extracted from electronic medical records and divided into five parts:

- ◦

Anthropometric Measurements: Height, weight, BMI, and Waist Circumference.

- ◦

Clinical and Laboratory Data: Blood pressure (systolic and diastolic) and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels.

- ◦

Obesity-related comorbidities recorded by the physician at the time of first patient visit, namely hypertension, fatty liver, prediabetes, diabetes, hypothyroidism, and obstructive sleep apnea.

- ◦

Obesity management, including liraglutide (Saxenda) prescription, referral to a dietitian, health education, psychiatrist, psychologist, endocrinologist, pulmonologist, and clinical pharmacists.

- ◦

Based on clinical records at the time of the patient’s first visit, the EOSS stage and the stage of change were recorded as well.

2.4. Working Definitions

The EOSS assesses health complications associated with weight among individuals who are overweight or obese (Swaleh et al., 2021). The application of the EOSS categorizes patients into specific stages based on various health indicators. The EOSS includes stages from 0 to 4, with the stage being based on the most severely affected obesity-related comorbidity. (

Appendix A)

The data definitions for the EOSS comorbidities are included in

Figure 1 (Swaleh et al., 2021).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The Statistical Software Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 20.0, was used to perform the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations (SD) and frequencies (percentages), were used to describe the participants’ demographics and clinical characteristics. All continuous variables were tested for normality using histograms and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The differences between EOSS stages were assessed using chi-square test for categorical independent variables and the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test for continuous independent variables. Two-sided p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

2.5.1. Ethical Consideration

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Prince Sultan Military Medical City (approval no. [HP-01-R079]). Due to the retrospective nature of the study and the utilization of de-identified patient data, informed consent was waived. Collected data were used only for this study, and data were secured and confidentiality were maintained throughout the study

2.5.2. Budget

No external funding or financial support was received for this study. The Lifestyle Medicine Clinic at Prince Sultan Military Medical City provided all utilized resources.

3. Results

Out of 960 patients, 678 (70.6%) were female and the average age was 39.17 ± 10.36 years. The baseline lifestyle assessments revealed that 55 (5.7%) patients were current smokers, 151 (15.7%) adhered to low-caloric diets, and 132 (13.8%) were physically active for 150 minutes/week. The anthropometric measurements of the participants were: the mean BMI was 36 ± 4 kg/m2, the mean waist circumference was 106 ± 11 cm, with an average of 114 ± 10 for males, and 104 ± 10 cm for females (

Table 1).

The frequent comorbidities found among the study participants at the first visit were prediabetes 678 (70.6%), dyslipidemia 593 (61.8%), and hypertension 184 (19.2%) (

Table 2).

Patients who visited the lifestyle clinic within the normal weight range were two (0.2%). Patients with overweight were 41 (4.3%), class one obesity were 375 (39.1%), class two obesity were 471 (49.1%), and class three obesity were 71 (7.4%).

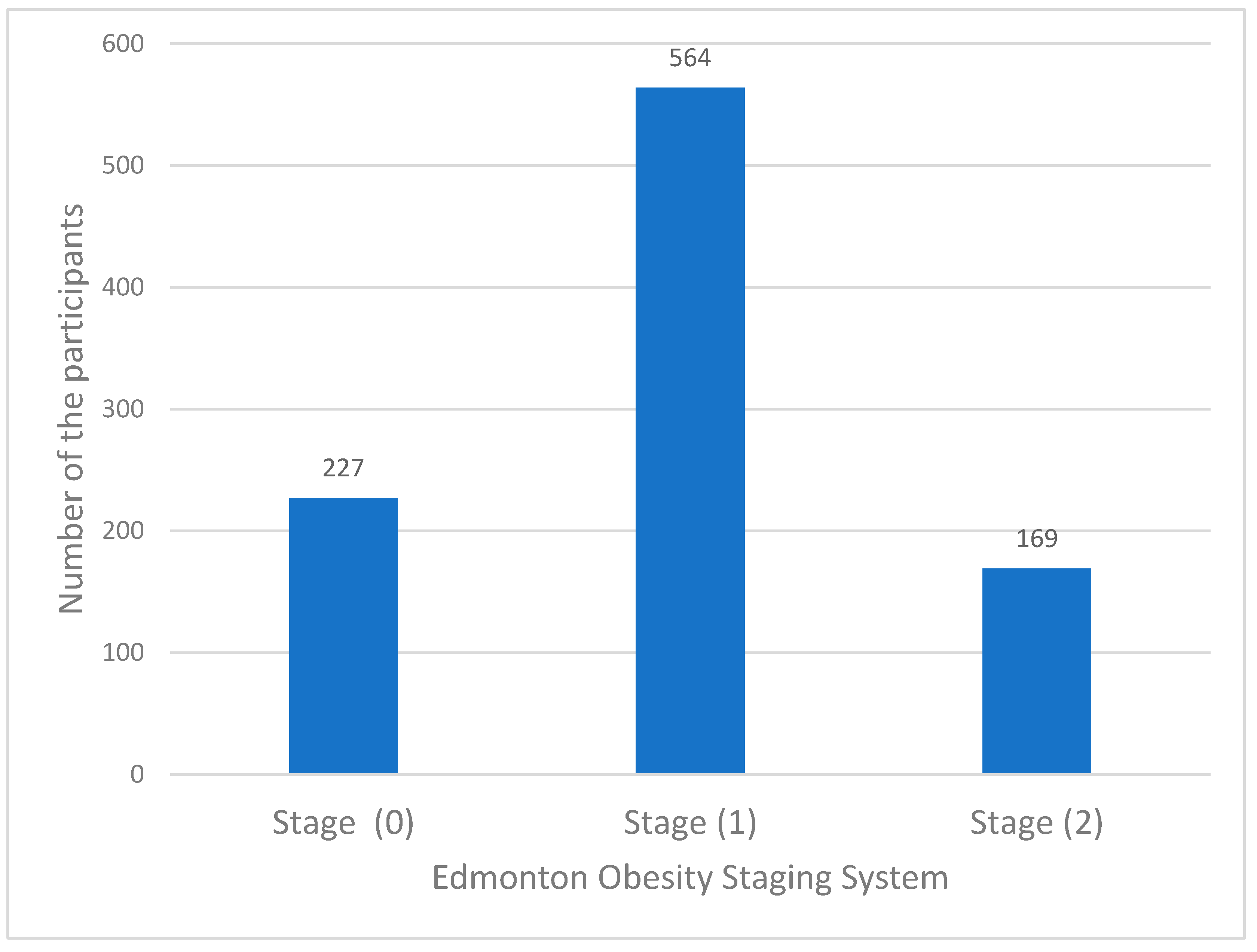

The distribution of the participants according to the Edmonton Obesity Staging System (EOSS) was as follows: stage zero, 227 (23.6%); stage one, 564 (58.8%); stage two, 169 (17.6%); and none of them were in stage three or four at presentation. This is most likely because the local policy in Wazarat Health Care Center states that patients who are in these stages should be referred to a secondary health care level. (

Figure 2).

Male gender and age of 40 years and above were significantly had higher EOSS stages,

p < 0.001 for each. Lifestyle related risk factors, namely being smoker, eating low caloric diet or practicing physical Activity (≥150 min/week), were not statistically significantly different between patients with different EOSS stage, p 0.370, 0.659, 0.804 respectively. Anthropometric measurements, namely height, weight, BMI, and waist circumference were statistically significantly higher in patients with high EOSS stage, p <0.001, <0.001, 0.007, <0.001 respectively. In addition, both Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were significantly higher in patients with high EOSS stage, p <0.001 for each. Moreover, HBA1c levels are statistically significantly high in patients with higher EOSS stages, p <0.001 (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates the application of the Edmonton Obesity Stage System (EOSS) in a primary care-based lifestyle medicine clinic, aiming to improve obesity risk stratification. Traditional BMI-based classifications fall short of capturing the comprehensive array of comorbidities associated with obesity and their impact on functional health. By incorporating metabolic, functional, and psychological parameters, EOSS proves to be a more effective tool for customizing obesity management strategies (Atlantis et al., 2020; Padwal et al., 2011; Swaleh et al., 2021).

Additionally, our results advocate for a shift from weight-centric to health-focused obesity care models (Padwal et al., 2011). By categorizing patients into EOSS stages, clinicians can implement targeted, risk-oriented interventions, particularly for those in stage 3 who require more intensive management. Such approaches have been shown to improve patient engagement and long-term weight management outcomes, as focusing on overall health rather than weight reduces the stigma associated with obesity (Atlantis et al., 2020; Puhl & Heuer, 2009).

A significant finding of this study is the correlation of increased EOSS stages with older age and male sex, consistent with literature suggesting that men face metabolic derangements at lower BMI thresholds than women. This may be due to differences in fat distribution, as men tend to store more visceral fat, a major contributor to metabolic syndrome (Kissebah & Krakower, 1994; Puhl & Heuer, 2009). In our study, we found anthropometric measures are significantly high in patients with higher EOSS stages, however, this associated in the literature is conflicting. Patients in EOSS stages 2–3 often have BMIs only 7-8 kg/m 2 higher than normal-weight individuals, yet their comorbidity burden varies widely (Ali et al., 2024; Rodríguez-Flores et al., 2022). In a cohort study, BMI had the lowest consistency with EOSS-defined obesity compared to the waist-to-height ratio (Myung et al., 2019). Furthermore, Higher EOSS stages (e.g., stage 3) are associated with similar BMI to lower stages but significantly worse health outcomes (Ali et al., 2024; Chiappetta et al., 2016). Moreover, our study showed that higher blood pressure and HbA1c are significantly higher in patients with high EOSS stages which align with reports indicating that patients in EOSS stages 1 and 2 have a markedly increased risk of cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome compared to those in stage 0 (Kuk et al., 2011; Padwal et al., 2011).

Despite the structured approach EOSS provides for obesity risk stratification, challenges remain in its widespread implementation in primary care settings. Variability in clinician interpretations of EOSS criteria, particularly relating to mental health and functional status assessments, can affect staging accuracy (Atlantis et al., 2020; Swaleh et al., 2021). To address this, structured training and clinical decision-support tools are essential for ensuring consistency across diverse healthcare environments. Furthermore, it is crucial to note that the EOSS does not currently account for socioeconomic factors that may influence obesity-related health risks (Atlantis et al., 2020; Jensen et al., 2014). Overcoming these barriers is vital for optimizing the effectiveness of EOSS in clinical practice.

This study contributes to the evidence base supporting the EOSS as a valuable clinical tool for decision-making in primary care settings. By adopting a more individualized and risk-based approach, EOSS incorporates metabolic, functional, and psychological parameters in obesity management.

However, this retrospective study has several limitations. As a single-center investigation, the generalizability of the findings may be restricted across different healthcare settings. The reliance on secondary data from electronic medical records, collected for purposes other than research, introduces potential gaps and inconsistencies in clinical documentation. Additionally, certain patient groups were excluded from the study, such as those with type 2 diabetes and patients younger than 14 or older than 65 years. This exclusion, alongside a focus on a limited range of comorbidities, may narrow the perceived utility of EOSS. The absence of certain obesity-related comorbidities and potential inconsistencies in applying EOSS staging criteria highlight the need for methodological improvements in future research. This study also did not assess the long-term outcomes of EOSS-guided interventions, indicating the necessity for longitudinal studies. Furthermore, without a control group, comparing EOSS-based obesity management with traditional BMI-based classification methods was not feasible.

Future multicenter prospective studies with control groups and broader inclusion criteria are essential. Additional research should explore the long-term clinical significance of the EOSS and assess its impact on health outcomes and patient adherence to obesity treatment recommendations. Specifically, future studies should evaluate whether EOSS leads to improved metabolic control, fewer cardiovascular events, and a higher quality of life compared to alternative obesity staging models (Atlantis et al., 2020; Padwal et al., 2011).

Our study demonstrates that EOSS serves as a clinically applicable tool for stratifying patients along the risk continuum for obesity-related health issues in primary care settings. By integrating diverse clinical, metabolic, and psychological factors, EOSS enables enhanced patient stratification and more targeted management approaches. Additionally, studies should examine how EOSS compares to emerging models of obesity classification, along with its effects on clinical decision-making, healthcare resource utilization, and long-term treatment adherence.

6. Conclusion

Integrating EOSS into primary care tends to be feasible for obesity management which potentially enhances risk stratification. Higher EOSS stages were significantly associated with age, male gender, anthropometric measures, blood pressure and HbA1c. Future prospective studies with broader inclusion criteria are needed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A. and G.G.; Methodology, D.A., G.G., and A.K.; Software, D.A., G.G., and S.A.; Validation, D.A. and G.G.; Formal analysis, M.K., and L.A.; Investigation, D.A. and G.G.; Resources, A.K., D.D., G.G., L.A., and S.A.; Data curation, D.A. and G.G.; Writing—original draft, D.A., G.G., and L.A.; Writing—review & editing, D.A. and G.G..; Visualization, A.K, and S.A.; Supervision, A.K., and M.K.; Project administration

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The study was conducted at the Lifestyle Medicine Clinic at Prince Sultan Military Medical City in Riyadh, and several authors are affiliated with it. This affiliation is recognized as a potential non-financial competing interest. Authors have no financial or commercial conflicts of interest in this study.

Appendix A

The staging criteria were based on the standardized EOSS framework developed by Sharma and Kushner (2009): (1)

Patients are classified into Stage 0 if they meet all of the following criteria:

Normal HbA1c levels without a diagnosis of diabetes

Normal blood pressure without a diagnosis of hypertension

No diagnosis of dyslipidemia

Negative depression screening test

Negative obstructive sleep apnea screening based on the STOP-BANG questionnaire (S: Snoring, T: Tiredness, O: Observed apnea, P: high blood pressure, B: Body mass index, A: Age, N: Neck circumference, and G: Gender)

Patients are classified into Stage 1 if they exhibit any of the following:

Prediabetes diagnosis or elevated HbA1c levels

Pre-hypertension diagnosis or elevated blood pressure levels

Dyslipidemia diagnosis

Positive depression screening test, but without requiring referral to a psychiatrist/psychologist

Negative obstructive sleep apnea screening based on the STOP-BANG questionnaire

Patients are classified into Stage 2 if they meet any of the following conditions:

Diabetes diagnosis or HbA1c levels indicative of diabetes

Hypertension diagnosis or elevated blood pressure levels

Positive depression screening test requiring referral to a psychiatrist/psychologist

Positive obstructive sleep apnea screening by STOP-BANG questionnaire, requiring referral for a sleep study

Stage 3: Patients classified in this stage have end-organ damage or significant functional impairment due to obesity-related conditions, such as heart disease, stroke, severe osteoarthritis, or advanced diabetic complications.

Stage 4: This stage includes patients with severe, life-threatening obesity-related conditions, such as end-stage organ failure, uncontrolled cardiovascular disease, or severe disability due to obesity.

Other obesity-related comorbidities, such as anxiety, were not scored due to the unavailability of data.

References

- J., A. Q., M. S., P., J. A., C., E., S., & M., O. (2014). Trends and future projections of the prevalence of adult obesity in Saudi Arabia, 1992-2022. 589–595. https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/emr-159248.

- Ali, S., Khan, O. S., Youssef, A. M., Saba, I., Alqahtani, L., Alduhaim, R. A., & Almesned, R. (2024). Predicting COVID-19 outcomes with the Edmonton Obesity Staging System. Annals of Saudi Medicine, 44(2), 116–125. [CrossRef]

- Al-Rubeaan, K., Bawazeer, N., Al Farsi, Y., Youssef, A. M., Al-Yahya, A. A., AlQumaidi, H., Al-Malki, B. M., Naji, K. A., Al-Shehri, K., & Al Rumaih, F. I. (2018). Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Saudi Arabia—A cross sectional study. BMC Endocrine Disorders, 18(1), 16. [CrossRef]

- Atlantis, E., Sahebolamri, M., Cheema, B. S., & Williams, K. (2020). Usefulness of the Edmonton Obesity Staging System for stratifying the presence and severity of weight-related health problems in clinical and community settings: A rapid review of observational studies. Obesity Reviews, 21(11), e13120. [CrossRef]

- Canning, K. L., Brown, R. E., Wharton, S., Sharma, A. M., & Kuk, J. L. (2015). Edmonton Obesity Staging System Prevalence and Association with Weight Loss in a Publicly Funded Referral-Based Obesity Clinic. Journal of Obesity, 2015(1), 619734. [CrossRef]

- Chiappetta, S., Stier, C., Squillante, S., Theodoridou, S., & Weiner, R. A. (2016). The importance of the Edmonton Obesity Staging System in predicting postoperative outcome and 30-day mortality after metabolic surgery. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases: Official Journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery, 12(10), 1847–1855. [CrossRef]

- De Wolf, A., Nauwynck, E., Vanbesien, J., Staels, W., De Schepper, J., & Gies, I. (2024). Optimizing Childhood Obesity Management: The Role of Edmonton Obesity Staging System in Personalized Care Pathways. Life, 14(3), Article 3. [CrossRef]

- Dobbie, L. J., Coelho, C., Crane, J., & McGowan, B. (2023). Clinical evaluation of patients living with obesity. Internal and Emergency Medicine, 18(5), 1273–1285. [CrossRef]

- Huxley, R., Mendis, S., Zheleznyakov, E., Reddy, S., & Chan, J. (2010). Body mass index, waist circumference and waist:hip ratio as predictors of cardiovascular risk—A review of the literature. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 64(1), 16–22. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. D., Ryan, D. H., Apovian, C. M., Ard, J. D., Comuzzie, A. G., Donato, K. A., Hu, F. B., Hubbard, V. S., Jakicic, J. M., & Kushner, R. F. (2014). Reprint: 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults. J Am Pharm Assoc, 54(1), e3. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=7c28596b33491c05d557becba3861acc0562df51.

- Kissebah, A. H., & Krakower, G. R. (1994). Regional adiposity and morbidity. Physiological Reviews, 74(4), 761–811. [CrossRef]

- Konswa, A. A., Alolaiwi, L., Alsakkak, M., Aleissa, M., Alotaibi, A., Alanazi, F. F., & Rasheed, A. bin. (2023). Experience of establishing a lifestyle medicine clinic at primary care level- challenges and lessons learnt. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 18(6), 1364–1372. [CrossRef]

- Kuk, J. L., Ardern, C. I., Church, T. S., Sharma, A. M., Padwal, R., Sui, X., & Blair, S. N. (2011). Edmonton Obesity Staging System: Association with weight history and mortality risk. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 36(4), 570–576. [CrossRef]

- Lehnert, T., Sonntag, D., Konnopka, A., Riedel-Heller, S., & König, H.-H. (2013). Economic costs of overweight and obesity. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 27(2), 105–115. [CrossRef]

- Murray, C. J. L., Aravkin, A. Y., Zheng, P., Abbafati, C., Abbas, K. M., Abbasi-Kangevari, M., Abd-Allah, F., Abdelalim, A., Abdollahi, M., Abdollahpour, I., Abegaz, K. H., Abolhassani, H., Aboyans, V., Abreu, L. G., Abrigo, M. R. M., Abualhasan, A., Abu-Raddad, L. J., Abushouk, A. I., Adabi, M., … Lim, S. S. (2020). Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet, 396(10258), 1223–1249. [CrossRef]

- Myung, J., Jung, K. Y., Kim, T. H., & Han, E. (2019). Assessment of the validity of multiple obesity indices compared with obesity-related co-morbidities. Public Health Nutrition, 22(7), 1241–1249. [CrossRef]

- Ortega, F. B., Lavie, C. J., & Blair, S. N. (2016). Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation Research, 118(11), 1752–1770. [CrossRef]

- Padwal, R. S., Pajewski, N. M., Allison, D. B., & Sharma, A. M. (2011). Using the Edmonton obesity staging system to predict mortality in a population-representative cohort of people with overweight and obesity. CMAJ, 183(14), E1059–E1066. [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R. M., & Heuer, C. A. (2009). The Stigma of Obesity: A Review and Update. Obesity, 17(5), 941–964. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Flores, M., Goicochea-Turcott, E. W., Mancillas-Adame, L., Garibay-Nieto, N., López-Cervantes, M., Rojas-Russell, M. E., Castro-Porras, L. V., Gutiérrez-León, E., Campos-Calderón, L. F., Pedraza-Escudero, K., Aguilar-Cuarto, K., Villanueva-Ortega, E., Hernández-Ruíz, J., Guerrero-Avendaño, G., Monzalvo-Reyes, S. M., García-Rascón, R., Gil-Velázquez, I. N., Cortés-Hernández, D. E., Granados-Shiroma, M., … Gregg, E. W. (2022). The utility of the Edmonton Obesity Staging System for the prediction of COVID-19 outcomes: A multi-centre study. International Journal of Obesity (2005), 46(3), 661–668. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A. M., & Kushner, R. F. (2009). A proposed clinical staging system for obesity. International Journal of Obesity, 33(3), 289–295. [CrossRef]

- Swaleh, R., McGuckin, T., Myroniuk, T. W., Manca, D., Lee, K., Sharma, A. M., Campbell-Scherer, D., & Yeung, R. O. (2021). Using the Edmonton Obesity Staging System in the real world: A feasibility study based on cross-sectional data. Canadian Medical Association Open Access Journal, 9(4), E1141–E1148. [CrossRef]

- Wildman, R. P., Muntner, P., Reynolds, K., McGinn, A. P., Rajpathak, S., Wylie-Rosett, J., & Sowers, M. R. (2008). The Obese Without Cardiometabolic Risk Factor Clustering and the Normal Weight With Cardiometabolic Risk Factor Clustering: Prevalence and Correlates of 2 Phenotypes Among the US Population (NHANES 1999-2004). Archives of Internal Medicine, 168(15), 1617–1624. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).