Submitted:

11 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

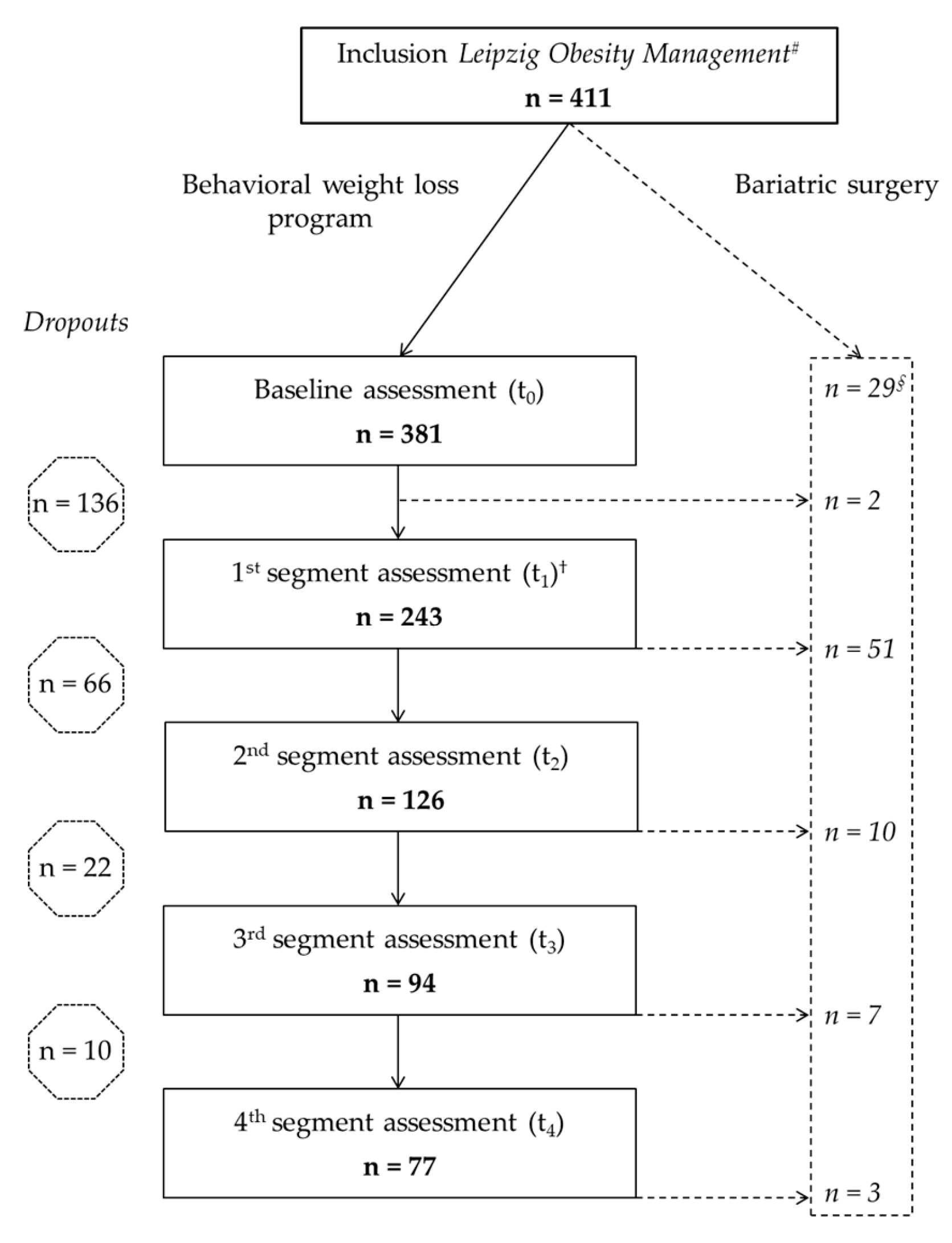

2.1. Patients

2.2. Interventions and Assessments

2.3. Assessments of Laboratory Parameters

2.4. Statistical Analysis of Medical Data

2.5. Assessment and Statistical Analysis of Healthcare Costs

3. Results

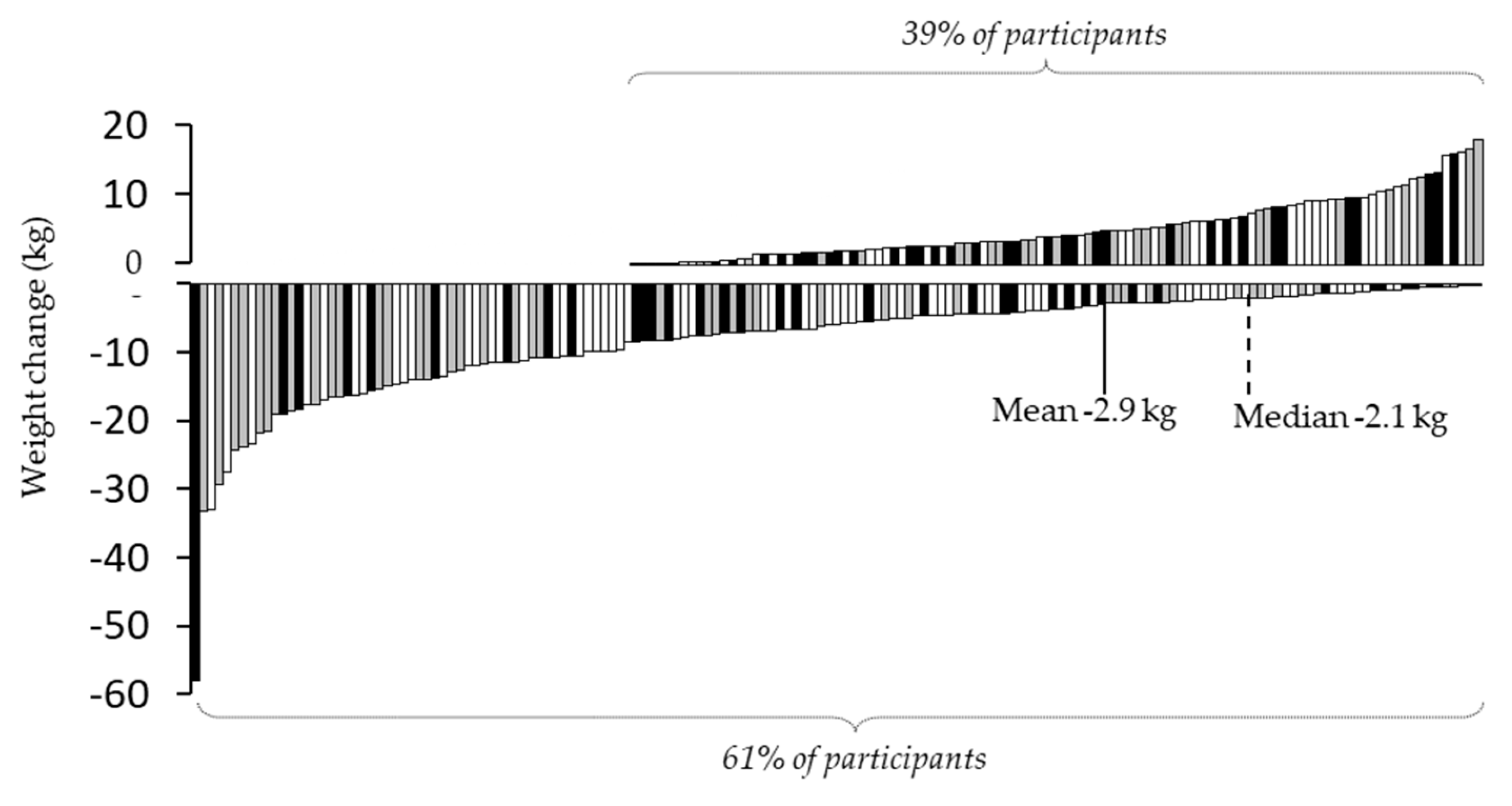

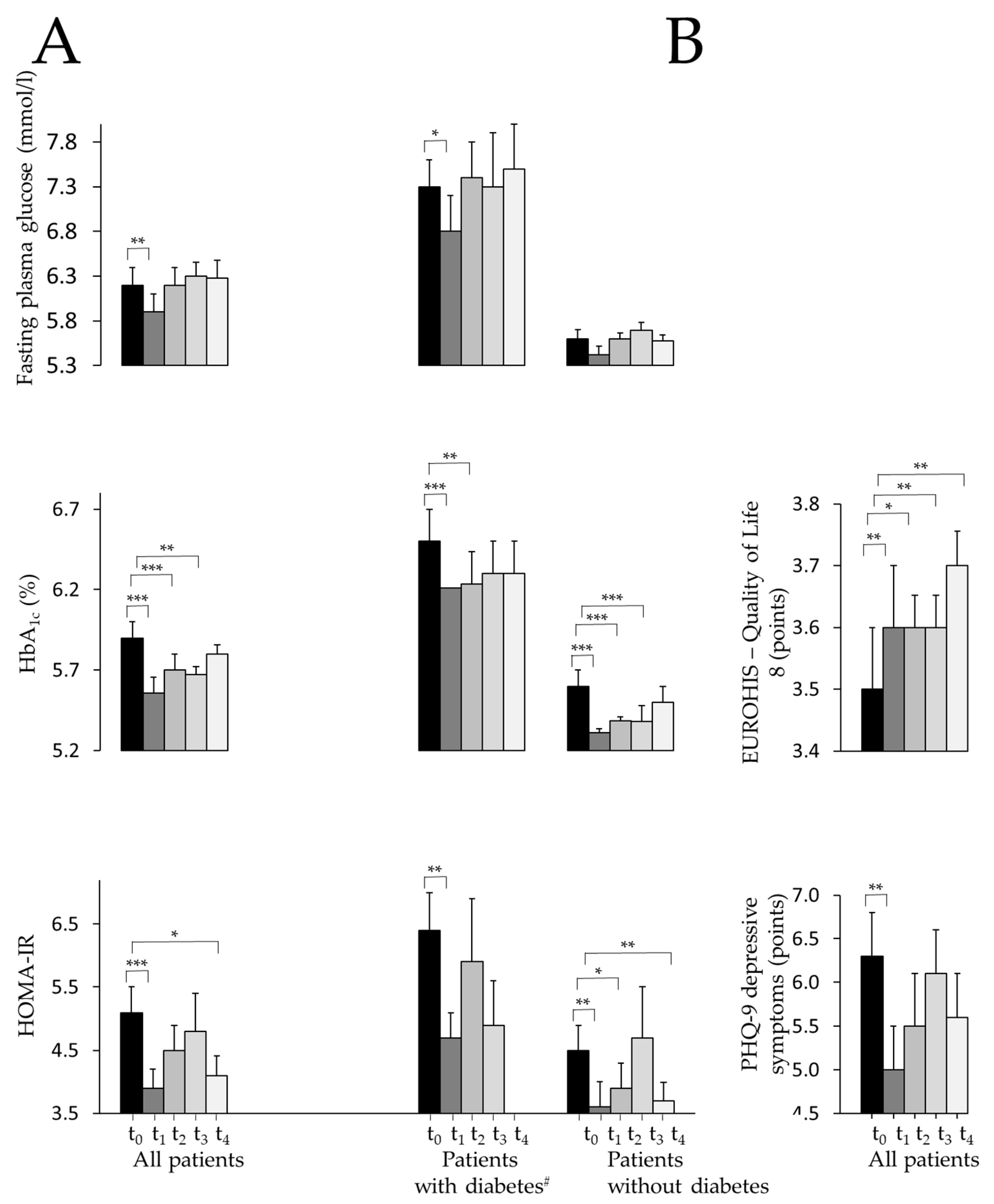

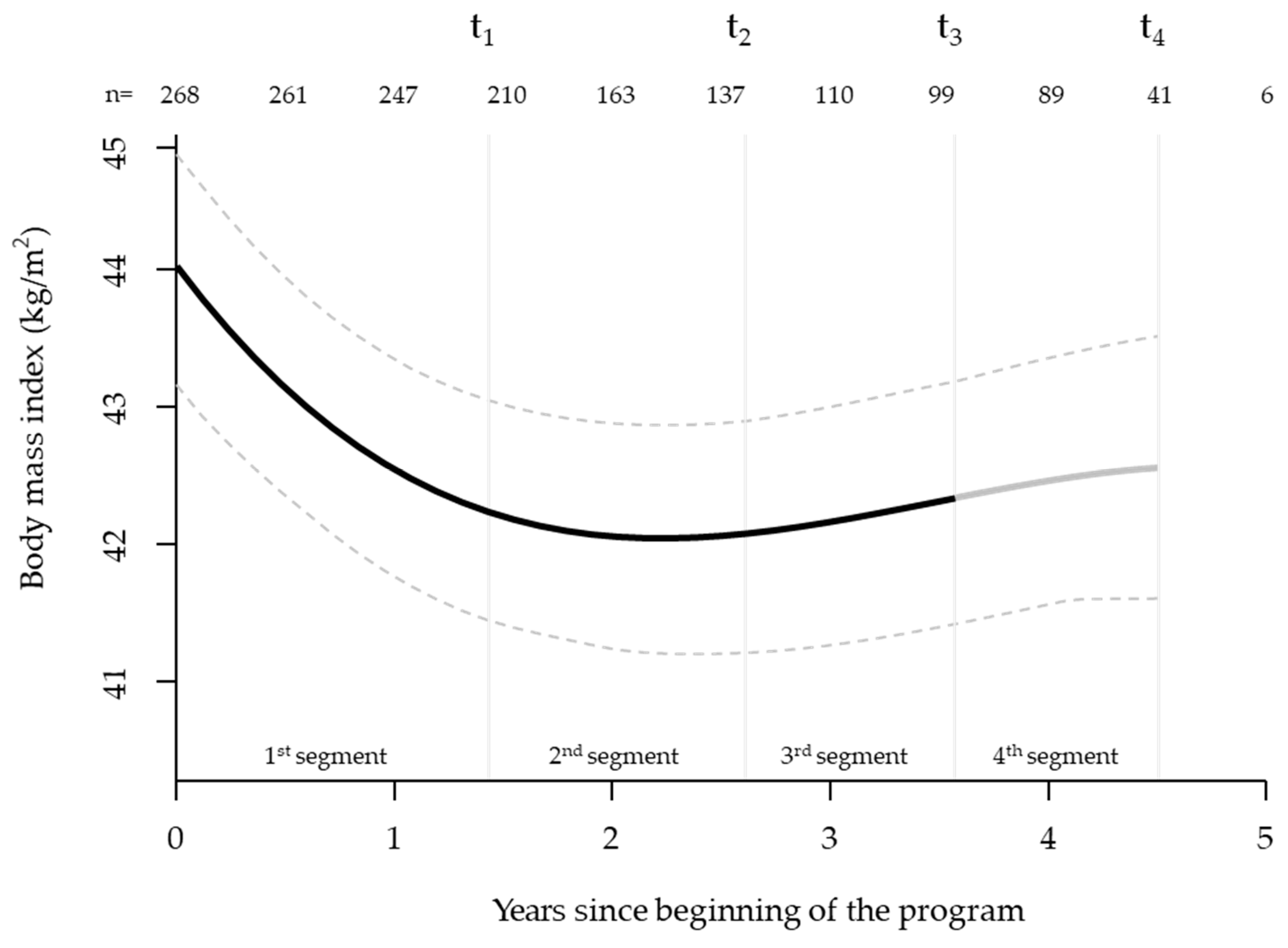

3.1. Mixed Model Analysis (Starting at t0 with n=381)

3.2. Completer Analysis of Variance of All Measured Parameters (n=77)

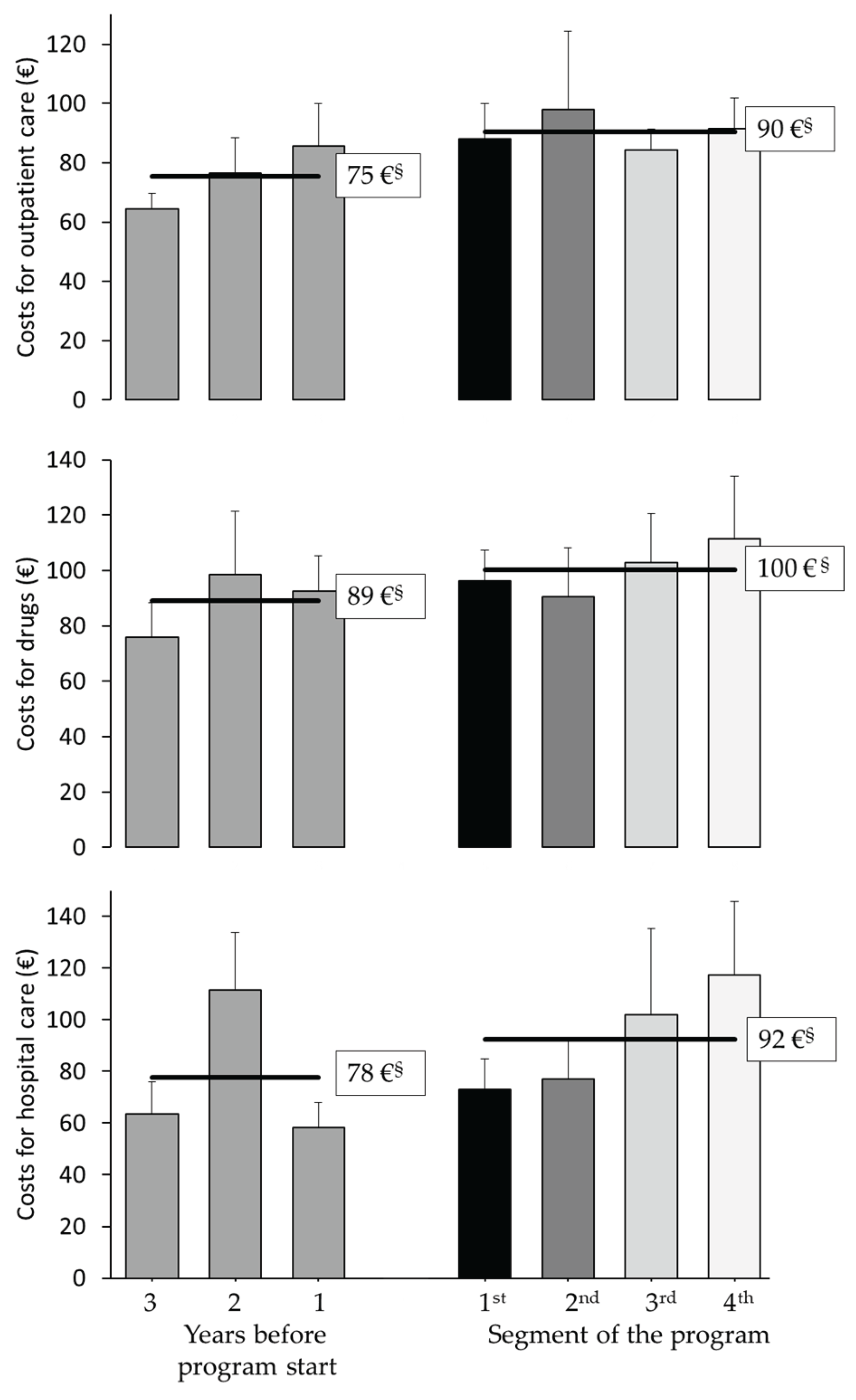

3.3. Exploratory Analysis of Healthcare Cost Changes Over Time (Starting Three Years Before Program)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Diagnostic field | Parameter |

| Glucose Metabolism | Glucose Hemoglobin A1c C-Peptide Insulin |

| Lipids | Triglycerides Cholesterol High-density lipoprotein Low-density lipoprotein |

| Endocrinology | Cortisol Lutropin Follitropin Estradiol Testosteron |

| Electrolytes | Potassium Sodium |

| Haematology | Blood cell count |

| Liver/Pancreas | Alanine-aminotransferase Aspartate-aminotransferase Alkaline phosphatase Gamma-glutamyltransferase |

| Kidney | Creatinine |

| Heart/muscles | Creatine kinase |

| Inflammation | C-reactive protein |

| Inclusion criteria | Group size | Nutritional therapy | Exercise training | Behavioral therapy | Psychological crisis intervention | ||

| Group sessions | Individual sessions | Group sessions | Groups sessions | Individual sessions | |||

| 1st segment of therapy | |||||||

| „Individual therapy program“ | BMI ≥35 kg/m2 adaptable to physical fitness |

13-15 participants | 8 units with 90 min. | 6 units with 30 min.§ | 48 units with 60 min. | 10 units with 90 min. | as necessary |

| M.O.B.I.L.I.S. | BMI 35-40 kg/m2 At least 1 W per kg bodyweight in physical fitness test |

15-18 participants | 6 units with 90 min. | - § | 40 units with 60 min. | 12 units with 90 min. | as necessary |

| DOC WEIGHT® | BMI 35-40 kg/m2 plus comorbidity or BMI ≥40 kg/m2 At least 1 W per kg bodyweight in physical fitness test |

11-13 participants | 12 units with 90 min. | 2 units with 60 min.§ | 40 units with 45 min. | 12 units with 90 min. | as necessary |

| 2nd to 4th segment of therapy | |||||||

| Successful completion of the 1st segment | 13-18 participants | - | 8 units with 30 min.§ | 36 units with 60 min. | 16 units with 120 min. | as necessary | |

Three Options of Behavioral Therapy Programs

| Item | t0 (n=359) |

t1 (n=222) |

t2 (n=119) |

t3 (n=89) |

t4 (n=57) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. How would you rate your quality of life? | 3.3 ±0.1 | 3.4 ±0.1* | 3.5 ±0.1*** | 3.6 ±0.1*** | 3.5 ±0.1 | <.001 |

| 2. How satisfied are you with your health? | 2.5 ±0.1 | 3.0 ±0.1*** | 3.1 ±0.1*** | 3.0 ±0.1*** | 3.0 ±0.1** | <.001 |

| 3. Do you have enough energy for everyday life? | 3.3 ±0.1 | 3.4 ±0.1 | 3.6 ±0.1** | 3.5 ±0.1** | 3.5 ±0.1 | <.01 |

| 4. How satisfied are you with your ability to perform your daily activities? | 3.2 ±0.1 | 3.5 ±0.1*** | 3.5 ±0.1** | 3.5 ±0.1** | 3.6 ±0.1*** | <.001 |

| 5. How satisfied are you with yourself? | 2.9 ±0.1 | 3.2 ±0.1*** | 3.4 ±0.1*** | 3.5 ±0.1*** | 3.5 ±0.1*** | <.001 |

| 6. How satisfied are you with your personal relationships? | 3.6 ±0.1 | 3.8 ±0.1* | 3.8 ±0.1 | 4.0 ±0.1*** | 3.9 ±0.1* | <.001 |

| 7. Have you enough money to meet your needs? | 3.1 ±0.1 | 3.3 ±0.1 | 3.4 ±0.1** | 3.5 ±0.1*** | 3.6 ±0.1*** | <.001 |

| 8. How satisfied are you with the conditions of your living place? | 4.0 ±0.1 | 4.0 ±0.1 | 4.0 ±0.1 | 4.1 ±0.1 | 4.1 ±0.1 | .33 |

| Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems? |

t0 (n=379) |

t1 (n=224) |

t2 (n=119) |

t3 (n=89) |

t4 (n=56) |

p |

| 1. Little interest or pleasure in doing things | 2.0 ±0.0 | 1.8 ±0.0** | 1.8 ±0.1** | 1.9 ±0.1 | 1.9 ±0.1 | <.01 |

| 2. Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless | 2.0 ±0.0 | 1.7 ±0.1** | 1.6 ±0.1*** | 1.6 ±0.1*** | 1.6 ±0.1*** | <.001 |

| 3. Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much | 2.5 ±0.1 | 2.2 ±0.1** | 2.3 ±0.1 | 2.3 ±0.1 | 2.4 ±0.1 | <.01 |

| 4. Feeling tired or having little energy | 2.5 ±0.1 | 2.1 ±0.1*** | 2.2 ±0.1** | 2.2 ±0.1** | 2.3 ±0.1 | <.001 |

| 5. Poor appetite or overeating | 2.1 ±0.1 | 1.9 ±0.1*** | 1.8 ±0.1*** | 1.9 ±0.1** | 1.8 ±0.1** | <.001 |

| 6. Feeling bad about yourself – or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down | 1.8 ±0.1 | 1.5 ±0.1*** | 1.4 ±0.1*** | 1.5 ±0.1** | 1.4 ±0.1*** | <.001 |

| 7. Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television | 1.6 ±0.1 | 1.5 ±0.1 | 1.4 ±0.1 | 1.5 ±0.1 | 1.6 ±0.1 | .07 |

| 8. Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed? Or the opposite – being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more than usual | 1.3 ±0.0 | 1.2 ±0.0** | 1.1 ±0.0*** | 1.2 ±0.0** | 1.2 ±0.1* | <.001 |

| 9. Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way | 1.2 ±0.0 | 1.1 ±0.0* | 1.1 ±0.0*** | 1.1 ±0.0*** | 1.1 ±0.0*** | <.001 |

| Reason for dropping out | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Personal / familial | 67 (28%) |

| Health | 37 (16%) |

| Termination by the university hospital due to lack of motivation | 77 (32%) |

| Professional | 17 (7%) |

| Dissatisfaction with the program | 16 (7%) |

| Death | 5 (2%) |

| Relocation | 4 (2%) |

| Other | 14 (6%) |

| t0 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (kg) Women Men |

381 272 (71.4%) 109 |

243 173 (71.2%) 70 |

126 89 (70.6%) 37 |

94 67 (71.3%) 27 |

77 55 (71.4%) 22 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) Women Men |

381 272 (71.4%) 109 |

243 173 (71.2%) 70 |

126 89 (70.6%) 37 |

94 67 (71.3%) 27 |

77 55 (71.4%) 22 |

| Waist circumference (cm) Women Men |

247 174 (70.4%) 73 |

210 146 (69.5%) 64 |

125 89 (71.2%) 36 |

94 67 (71.3%) 27 |

75 55 (73.3%) 20 |

| Hip circumference (cm) Women Men |

240 171 (71.3%) 69 |

207 145 (70.0%) 62 |

125 89 (71.2%) 36 |

94 67 (71.3%) 27 |

75 55 (73.3%) 20 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) Diabetic patients§ Non-diabetics |

379 116 (30.6%) 263 |

218 60 (27.5%) 158 |

115 32 (27.8%) 83 |

84 28 (33.3%) 56 |

70 25 (35.7%) 45 |

| HbA1c (%) Diabetic patients§ Non-diabetics |

353 98 (27.8%) 255 |

216 58 (26.9%) 158 |

115 32 (27.8%) 83 |

84 28 (33.3%) 56 |

70 25 (35.7%) 45 |

| C-peptide (nmol/l) Diabetic patients§ Non-diabetics |

355 111 (31.3%) 244 |

217 60 (27.6%) 157 |

114 32 (28.1%) 82 |

84 28 (33.3%) 56 |

69 24 (34.8%) 45 |

| HOMA2-IR Diabetic patients† Non-diabetics |

311 74 (23.8%) 237 |

209 52 (24.9%) 157 |

110 28 (25.5%) 82 |

80 24 (30.0%) 56 |

65 20 (30.8%) 45 |

| Total cholesterol‡ (mmol/l) | 379 | 225 | 116 | 84 | 66 |

| LDL cholesterol‡ (mmol/l) | 379 | 225 | 116 | 84 | 66 |

| HDL cholesterol‡ (mmol/l) | 379 | 227 | 116 | 84 | 66 |

| Triglycerides‡ (mmol/l) | 379 | 227 | 116 | 84 | 66 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 379 | 242 | 119 | 90 | 75 |

| ASAT (µkat/l) | 379 | 242 | 126 | 94 | 77 |

| ALAT (µkat/l) | 379 | 242 | 126 | 94 | 77 |

| GGT (µkat/l) | 379 | 242 | 126 | 94 | 77 |

| Quality of life (EUROHIS-QOL) | 360 | 222 | 119 | 89 | 57 |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 380 | 224 | 120 | 89 | 56 |

| t0 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (kg) Women Men |

119.4 ±2.7 113.2 ±2.5 134.9 ±5.9 |

111.7 ±2.6*** 105.7 ±2.4*** 126.8 ±5.8*** |

114.0 ±2.6*** 107.5 ±2.4** 130.3 ±5.5* |

114.5 ±2.6*** 108.1 ±2.5** 130.4 ±5.2* |

114.7 ±2.6*** 108.4 ±2. 4* 130.5 ±5.3* |

<.001# <.001# <.01# |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) Women Men |

42.6 ±0.8 42.9 ±0.9 42.0 ±1.5 |

39.9 ±0.8*** 40.0 ±0.9*** 39.4 ±1.5*** |

40.7 ±0.7*** 40.7 ±0.9** 40.6 ±1.4* |

40.8 ±0.7*** 40.9 ±0.9** 40.6 ±1.3* |

41.0 ±0.7** 41.1 ±0.9* 40.7 ±1.3* |

<.001# <.01# <.01# |

| Waist ratio (cm) Women Men |

124.9 ±1.9 121.7 ±2.1 134.4 ±3.3 |

120.7 ±1.9*** 116.8 ±1.8*** 130.5 ±4.0** |

120.8 ±1.9*** 116.9 ±1.9** 130.8 ±3.8* |

121.3 ±1.8*** 116.9 ±1.9** 132.0 ±3.4 |

122.3 ±1.9* 117.3 ±1.7** 136.0 ±3.6 |

<.001# <.01# <.05# |

| Hip ratio (cm) Women Men |

135.8 ±1.9 137.9 ±2.2 129.2 ±2.8 |

129.3 ±1.7*** 130.7 ±1.9*** 125.9 ±3.9** |

128.7 ±1.8*** 130.0 ±1.9*** 125.1 ±3.8** |

129.2 ±1.7*** 130.2 ±1.9*** 126.8 ±3.7* |

130.8 ±1.7** 131.2 ±1.9** 129.7 ±3.8 |

<.001# <.001# <.05# |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) Diabetic patients§ (n=25) Non-diabetics (n=45) |

6.2 ±0.2 7.3 ±0.3 5.6 ±0.1 |

5.9 ±0.2** 6.8 ±0.4* 5.4 ±0.1** |

6.2 ±0.2 7.4 ±0.4 5.6 ±0.1 |

6.3 ±0.2 7.3 ±0.6 5.7 ±0.1 |

6.3 ±0.2 7.5 ±0.5 5.6 ±0.1 |

.08# .36# <.05# |

| HbA1c (%) Diabetic patients§ Non-diabetics |

5.9 ±0.1 6.5 ±0.2 5.6 ±0.1 |

5.6 ±0.1*** 6.2 ±0.2** 5.3 ±0.0*** |

5.7 ±0.1*** 6.2 ±0.2* 5.4 ±0.0*** |

5.7 ±0.1*** 6.3 ±0.2 5.4 ±0.1*** |

5.8 ±0.1* 6.3 ±0.2 5.5 ±0.1** |

<.001# <.05 <.001 |

| C-peptide (nmol/l) Diabetic patients§ Non-diabetics |

1.2 ±0.1 1.4 ±0.1 1.2 ±0.1 |

1.1 ±0.1** 1.3 ±0.1 1.0 ±0.1* |

1.1 ±0.1** 1.2 ±0.1 1.0 ±0.1** |

1.0 ±0.1*** 1.1 ±0.1** 0.9 ±0.1** |

1.0 ±0.1** 1.2 ±0.2 0.9 ±0.1*** |

<.001# .22# <.001# |

| HOMA-IR Diabetic patients†(n=21) Non-diabetics (n=45) |

5.1 ±0.4 6.4 ±0.6 4.5 ±0.4 |

3.9 ±0.3*** 4.7 ±0.4*** 3.6 ±0.4** |

4.5 ±0.4 5.9 ±1.0 3.9 ±0.4 |

4.8 ±0.6 4.9 ±0.7 4.7 ±0.8 |

4.1 ±0.3** 4.9 ±0.7* 3.7 ±0.3 |

.16# .14# .35# |

| Total cholesterol‡ (mmol/l) | 5.1 ±0.1 | 4.9 ±0.1* | 4.9 ±0.1* | 5.0 ±0.1* | 4.9 ±0.1** | <.05 |

| LDL cholesterol‡ (mmol/l) | 3.3 ±0.1 | 3.2 ±0.1 | 3.3 ±0.1 | 3.2 ±0.1 | 3.2 ±0.1 | .18 |

| HDL cholesterol‡ (mmol/l) | 1.3 ±0.4 | 1.4 ±0.0* | 1.4 ±0.0* | 1.4 ±0.0* | 1.4 ±0.0** | <.05# |

| Triglyceride‡ (mmol/l) | 1.6 ±0.8 | 1.5 ±0.1** | 1.7 ±0.1 | 1.7 ±0.1 | 1.6 ±0.1 | <.01# |

| C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 7.8 ±0.8 | 6.5 ±1.1 | 6.1 ±0.6*** | 7.0 ±1.2 | 5.9 ±0.6** | .21# |

| ASAT (µkat/l) | 0.5 ±0.0 | 0.4 ±0.0** | 0.5 ±0.0 | 0.4 ±0.0*** | 0.4 ±0.0*** | <.01# |

| ALAT (µkat/l) | 0.6 ±0.0 | 0.5 ±0.0** | 0.5 ±0.1 | 0.5 ±0.0** | 0.5 ±0.0** | <.05# |

| GGT (µkat/l) | 0.7 ±0.1 | 0.6 ±0.1 | 0.7 ±0.1 | 0.6 ±0.1 | 0.6 ±0.1* | .11# |

| Quality of life (EUROHIS-QOL) | 3.5 ±0.1 | 3.6 ±0.1** | 3.6 ±0.1* | 3.6 ±0.1** | 3.7 ±0.1** | <.05 |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 6.3 ±0.5 | 5.0 ±0.5** | 5.5 ±0.6 | 6.1 ±0.5 | 5.6 ±0.5 | .19# |

References

- Avila, C.; Holloway, A.C.; Hahn, M.K.; Morrison, K.M.; Restivo, M.; Anglin, R. et al. An Overview of Links Between Obesity and Mental Health. Curr Obes Rep 2015; 4(3):303–10.

- World Health Oganisation. Obesity; 2023. Available from: URL: https://www.who.int/health-topics/obesity#tab=tab_1.

- Teuner, C.M.; Menn, P.; Heier, M.; Holle, R.; John, J.; Wolfenstetter, S.B. Impact of BMI and BMI change on future drug expenditures in adults: results from the MONICA/KORA cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13:424.

- Vidal, J. Updated review on the benefits of weight loss. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002; 26 Suppl 4:S25-8.

- Yumuk, V.; Tsigos, C.; Fried, M.; Schindler, K.; Busetto, L.; Micic, D.; et al. European Guidelines for Obesity Management in Adults. Obes Facts 2015; 8(6):402–24.

- Deutsche Adipositas-Gesellschaft (DAG) e., v. S3-Leitlinie Adipositas - Prävention und Therapie [Version 5.0 Oktober 2024]. Available from: URL: https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/050-001.

- Swan, W.I.; Vivanti, A.; Hakel-Smith, N.A.; Hotson, B.; Orrevall, Y.; Trostler, N.; et al. Nutrition Care Process and Model Update: Toward Realizing People-Centered Care and Outcomes Management. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2017; 117(12):2003–14.

- Lean, M.E.; Leslie, W.S.; Barnes, A.C.; Brosnahan, N.; Thom, G.; McCombie, L.; et al. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2018; 391(10120):541–51.

- Kim, T.J.; Knesebeck, O. von dem. Income and obesity: what is the direction of the relationship? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2018; 8(1):e019862.

- Weimann, A.; Fischer, M.; Oberänder, N.; Prodehl, G.; Weber, N.; Andrä, M.; et al. Willing to go the extra mile: Prospective evaluation of an intensified non-surgical treatment for patients with morbid obesity. Clin Nutr 2019; 38(4):1773–81.

- Wexler, D.J.; Chang, Y.; Levy, D.E.; Porneala, B.; McCarthy, J.; Rodriguez Romero, A.; et al. Results of a 2-year lifestyle intervention for type 2 diabetes: the Reach Ahead for Lifestyle and Health-Diabetes randomized controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2022; 30(10):1938–50.

- Aziz, Z.; Absetz, P.; Oldroyd, J.; Pronk, N.P.; Oldenburg, B. A systematic review of real-world diabetes prevention programs: learnings from the last 15 years. Implement Sci 2015; 10:172.

- Frenzel, S.V.; Bach, S.; Ahrens, S.; Hellbardt, M.; Hilbert, A.; Stumvoll, M.; et al. Ausweg aus der Versorgungslücke: Voll Krankenkassen-finanzierte konservative Adipositas-Therapie. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2020; 145(14):e78-e86.

- Brähler, E.; Mühlan, H.; Albani, C.; Schmidt, S. Teststatistische Prüfung und Normierung der deutschen Versionen des EUROHIS-QOL Lebensqualität-Index und des WHO-5 Wohlbefindens-Index. Diagnostica 2007; 53(2):83–96.

- Löwe, B.; Kroenke, K.; Herzog, W.; Gräfe, K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). J Affect Disord 2004; 81(1):61–6.

- Dietrich, A. Aktuelle S3-Leitlinie „Therapie der Adipositas und metabolischer Erkrankungen“. Allgemein- und Viszeralchirurgie up2date 2019; 13(02):111–21.

- König, D.; Hörmann, J. ; Predel, H-G.; Berg, A. A 12-Month Lifestyle Intervention Program Improves Body Composition and Reduces the Prevalence of Prediabetes in Obese Patients. Obes Facts 2018; 11(5):393–9.

- Rudolph, A.; Hellbardt, M.; Baldofski, S.; Zwaan, M. de; Hilbert, A. Evaluation des einjährigen multimodalen Therapieprogramms DOC WEIGHT® 1.0 zur Gewichtsreduktion bei Patienten mit Adipositas Grad II und III. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2016; 66(8):316–23.

- Schwalm, S.V.; Hilbert, A.; Stumvoll, M.; Striebel, R.; Sass, U.; Tiesler, U.; et al. Das Leipziger Adipositasmanagement. Adipositas - Ursachen, Folgeerkrankungen, Therapie 2015; 09(02):87–92. Available from: URL: https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/html/10.1055/s-0037-1618900.

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.P.; Rudenski, A.S.; Naylor, B.A.; Treacher, D.F.; Turner, R.C. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985; 28(7):412–9.

- Curtin, F. , Schulz, P. Multiple correlations and Bonferroni's correction. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44(8):775–7. Available from: URL: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9798082/.

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. The Annals of Statistics 1978; 6(2):461–4. Available from: URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2958889.

- Holm, S. A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics 1979; 6(2):65–70. Available from: URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4615733.

- Bischoff, S.C.; Schweinlin, A. Obesity therapy. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2020; 38:9–18.

- Bray, G.A.; Heisel, W.E.; Afshin, A.; Jensen, M.D.; Dietz, W.H.; Long, M.; et al. The Science of Obesity Management: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr Rev 2018; 39(2):79–132.

- Ryan, D.H.; Yockey, S.R. Weight Loss and Improvement in Comorbidity: Differences at 5%, 10%, 15%, and Over. Curr Obes Rep 2017; 6(2):187–94.

- Hauner, H.; Moss, A.; Berg, A.; Bischoff, S.C.; Colombo-Benkmann, M.; Ellrott, T.; et al. Interdisziplinäre Leitlinie der Qualität S3 zur „Prävention und Therapie der Adipositas”. Adipositas - Ursachen, Folgeerkrankungen, Therapie 2014; 08(04):179–221.

- Garvey, W.T.; Mechanick, J.I.; Brett, E.M.; Garber, A.J.; Hurley, D.L.; Jastreboff, A.M.; et al. AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGISTS AND AMERICAN COLLEGE OF ENDOCRINOLOGY COMPREHENSIVE CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR MEDICAL CARE OF PATIENTS WITH OBESITY. Endocr Pract 2016; 22 Suppl 3:1–203.

- Appel, L.J.; Clark, J.M. ; Yeh, H-C.; Wang, N-Y.; Coughlin, J.W.; Daumit, G. et al. Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. N Engl J Med 2011; 365(21):1959–68.

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 8. Obesity and Weight Management for the Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care 2022; 45(Suppl 1):S113-S124. Available from: URL: https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/45/Supplement_1/S113/138906/8-Obesity-and-Weight-Management-for-the-Prevention.

- Kullo, I.J.; Trejo-Gutierrez, J.F.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Thomas, R.J.; Allison, T.G.; Mulvagh, S.L.; et al. A perspective on the New American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for cardiovascular risk assessment. Mayo Clin Proc 2014; 89(9):1244–56.

- Grundy, S.M.; Stone, N.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Beam, C.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019; 139(25):e1082-e1143.

- 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis 2019; 290:140–205.

- Ge, L.; Sadeghirad, B.; Ball, G.D.C.; da Costa, B.R.; Hitchcock, C.L.; Svendrovski, A.; et al. Comparison of dietary macronutrient patterns of 14 popular named dietary programmes for weight and cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2020; 369:m696. Available from: URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7190064/.

- Chandrasekhar, J.; Zaman, S. Associations Between C-Reactive Protein, Obesity, Sex, and PCI Outcomes: The Fat of the Matter. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2020; 13(24):2893–5.

- Ramos-Lopez, O.; Martinez-Urbistondo, D.; Vargas-Nuñez, J.A.; Martinez, J.A. The Role of Nutrition on Meta-inflammation: Insights and Potential Targets in Communicable and Chronic Disease Management. Curr Obes Rep 2022; 11(4):305–35.

- McCarney, R.; Warner, J.; Iliffe, S.; van Haselen, R.; Griffin, M.; Fisher, P. The Hawthorne Effect: a randomised, controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007; 7:30.

- Kroenke, K. Enhancing the clinical utility of depression screening. CMAJ 2012; 184(3):281–2.

- Neri, Ld.C.L.; Mariotti, F.; Guglielmetti, M.; Fiorini, S.; Tagliabue, A.; Ferraris, C. Dropout in cognitive behavioral treatment in adults living with overweight and obesity: a systematic review. Frontiers in nutrition 2024; 11:1250683. Available from: URL: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38784136/.

- Tremmel, M. ; Gerdtham, U-G.; Nilsson, P.M.; Saha, S. Economic Burden of Obesity: A Systematic Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017; 14(4).

- Harrison, S.; Dixon, P.; Jones, H.E.; Davies, A.R.; Howe, L.D.; Davies, N.M. Long-term cost-effectiveness of interventions for obesity: A mendelian randomisation study. PLoS medicine 2021; 18(8):e1003725. Available from: URL: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34449774/.

- Xin, Y.; Davies, A.; Briggs, A.; McCombie, L.; Messow, C.M.; Grieve, E. et al. Type 2 diabetes remission: 2 year within-trial and lifetime-horizon cost-effectiveness of the Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial (DiRECT)/Counterweight-Plus weight management programme. Diabetologia:2112–22. [CrossRef]

| t0 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | p | |

| Patients n Women n (%) |

381 272 (71.4%) |

243 173 (71.2%) |

126 89 (70.6%) |

94 67 (71.3%) |

77 55 (71.4%) |

|

| Body weight (kg) Women Men |

127.3 ±1.3 120.4 ±1.3 144.3 ±2.6 |

122.2 ±1.3*** 115.3 ±1.3*** 139.4 ±2.7*** |

123.2 ±1.4*** 116.8 ±1.4*** 138.2 ±2.9** |

124.2 ±1.4** 117.6 ±1.5* 140.3 ±2.7** |

124.2 ±1.5** 117.6 ±1.5 140.4 ±2.9 |

<.001 <.001 <.01 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) Women Men |

44.3 ±0.4 44.2 ±0.5 44.7 ±0.7 |

42.6 ±0.4*** 42.3 ±0.4*** 43.2 ±0.7*** |

42.9 ±0.4*** 42.9 ±0.5*** 42.9 ±0.8** |

43.3 ±0.4** 43.2 ±0.5* 43.5 ±0.8** |

43.4 ±0.5** 43.2 ±0.5 43.5 ±0.8 |

<.001 <.001 <.01 |

| Waist ratio (cm) Women Men |

129.7 ±1.0 125.1 ±1.1 140.9 ±1.7 |

125.4 ±1.0*** 120.4 ±1.1*** 137.6 ±1.6** |

124.9 ±1.0*** 120.0 ±1.0*** 136.8 ±1.6*** |

125.0 ±1.0*** 119.6 ±1.1*** 138.3 ±1.8 |

126.4 ±1.2** 120.1 ±1.2*** 141.9 ±2.4 |

<.001 <.001 <.001 |

| Hip ratio (cm) Women Men |

138.6 ±0.9 139.4 ±1.1 136.9 ±1.8 |

134.4 ±0.9*** 135.0 ±1.1*** 132.8 ±1.7*** |

133.1 ±0.9*** 133.6 ±1.1*** 131.7 ±1.7*** |

133.6 ±1.0*** 133.8 ±1.1*** 133.4 ±2.0 |

134.7 ±1.2** 134.7 ±1.3*** 138.1 ±3.0 |

<.001 <.001 <.001 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) Patients with diabetes§ (t0: 28.0%) No diagnosed diabetes |

6.1 ±0.1 7.7 ±0.2 5.5 ±0.0 |

5.9 ±0.1** 7.4 ±0.2* 5.4 ±0.0 |

6.1 ±0.1 7.8 ±0.3 5.5 ±0.1 |

6.3 ±0.2 8.0 ±0.4 5.7 ±0.1 |

6.3 ±0.1 8.0 ±0.4 5.6 ±0.1 |

<.001 <.05 <.01 |

| HbA1c (%) Patients with diabetes§ No diagnosed diabetes |

5.8 ±0.0 6.6 ±0.1 5.5 ±0.0 |

5.6 ±0.0*** 6.2 ±0.1*** 5.3 ±0.0*** |

5.6 ±0.0*** 6.2 ±0.1** 5.4 ±0.0*** |

5.7 ±0.1** 6.4 ±0.1 5.4 ±0.0*** |

5.7 ±0.1 6.4 ±0.1 5.4 ±0.0 |

<.001 <.001 <.001 |

| C-peptide (nmol/l) Patients with diabetes§ No diagnosed diabetes |

1.4 ±0.0 1.6 ±0.1 1.3 ±0.0 |

1.3 ±0.0** 1.5 ±0.1 1.2 ±0.0** |

1.2 ±0.0*** 1.3 ±0.1* 1.1 ±0.0*** |

1.1 ±0.0*** 1.2 ±0.1*** 1.0 ±0.1*** |

1.1 ±0.1** 1.4 ±0.2 1.0 ±0.0*** |

<.001 <.01 <.001 |

| HOMA-IR Patients with diabetes† (t0: 22.1%) No diagnosed diabetes |

6.0 ±0.3 8.1 ±0.4 5.3 ±0.2 |

4.9 ±0.2*** 6.2 ±0.8* 4.5 ±0.2** |

5.1 ±0.3 6.7 ±1.1 4.5 ±0.3* |

5.2 ±0.3 6.8 ±0.9 4.6 ±0.4 |

5.0 ±0.3* - 4.3 ±0.3** |

<.01 <.05 <.01 |

| Total cholesterol‡ (mmol/l) | 5.1 ±0.1 | 5.0 ±0.1** | 4.9 ±0.1** | 4.9 ±0.1* | 4.9 ±0.1** | <.01 |

| LDL cholesterol‡ (mmol/l) | 3.3 ±0.1 | 3.2 ±0.1* | 3.3 ±0.1 | 3.2±0.1 | 3.2 ±0.1* | <.05 |

| HDL cholesterol‡ (mmol/l) | 1.2 ±0.0 | 1.3 ±0.0** | 1.3 ±0.0** | 1.3 ±0.0** | 1.3 ±0.0*** | <.001 |

| Triglycerides‡ (mmol/l) | 1.8 ±0.1 | 1.7 ±0.1 | 1.9 ±0.1 | 1.9 ±0.1 | 1.8 ±0.1 | <.01 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 8.4 ±0.3 | 7.6 ±0.5 | 7.0 ±0.6 | 8.7 ±1.7 | 6.5 ±0.5** | <.01 |

| ASAT (µkat/l) | 0.5 ±0.0 | 0.5 ±0.1*** | 0.5 ±0.0 | 0.4 ±0.0*** | 0.4 ±0.0*** | <.001 |

| ALAT (µkat/l) | 0.6 ±0.0 | 0.5 ±0.0*** | 0.5 ±0.0 | 0.5 ±0.0*** | 0.5 ±0.0*** | <.001 |

| GGT (µkat/l) | 0.7 ±0.0 | 0.6 ±0.0** | 0.6 ±0.0 | 0.6 ±0.0 | 0.6 ±0.0* | <.01 |

| Quality of life (EUROHIS-QOL) | 3.2 ±0.0 | 3.4 ±0.0*** | 3.5 ±0.1*** | 3.6 ±0.1*** | 3.6 ±0.1*** | <.001 |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 7.9 ±0.3 | 6.2 ±0.3*** | 5.9 ±0.4*** | 6.3 ±0.3*** | 6.3 ±0.4*** | <.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).