Submitted:

01 November 2024

Posted:

01 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

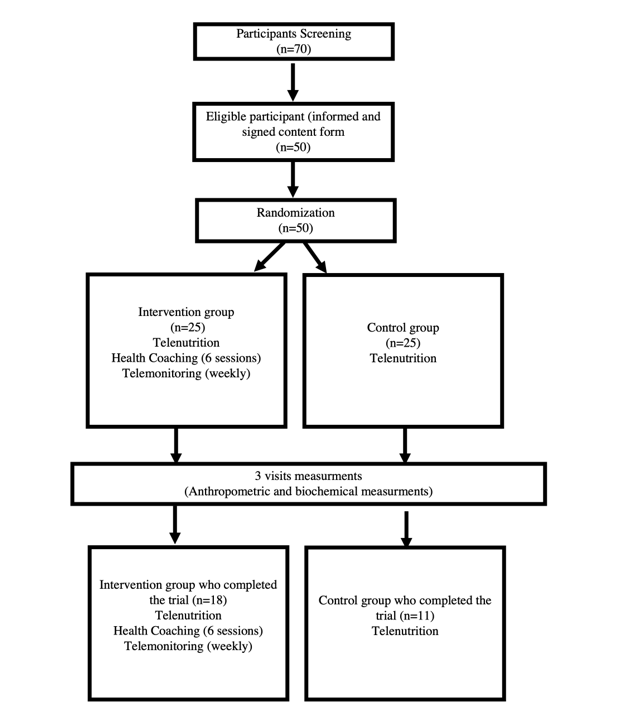

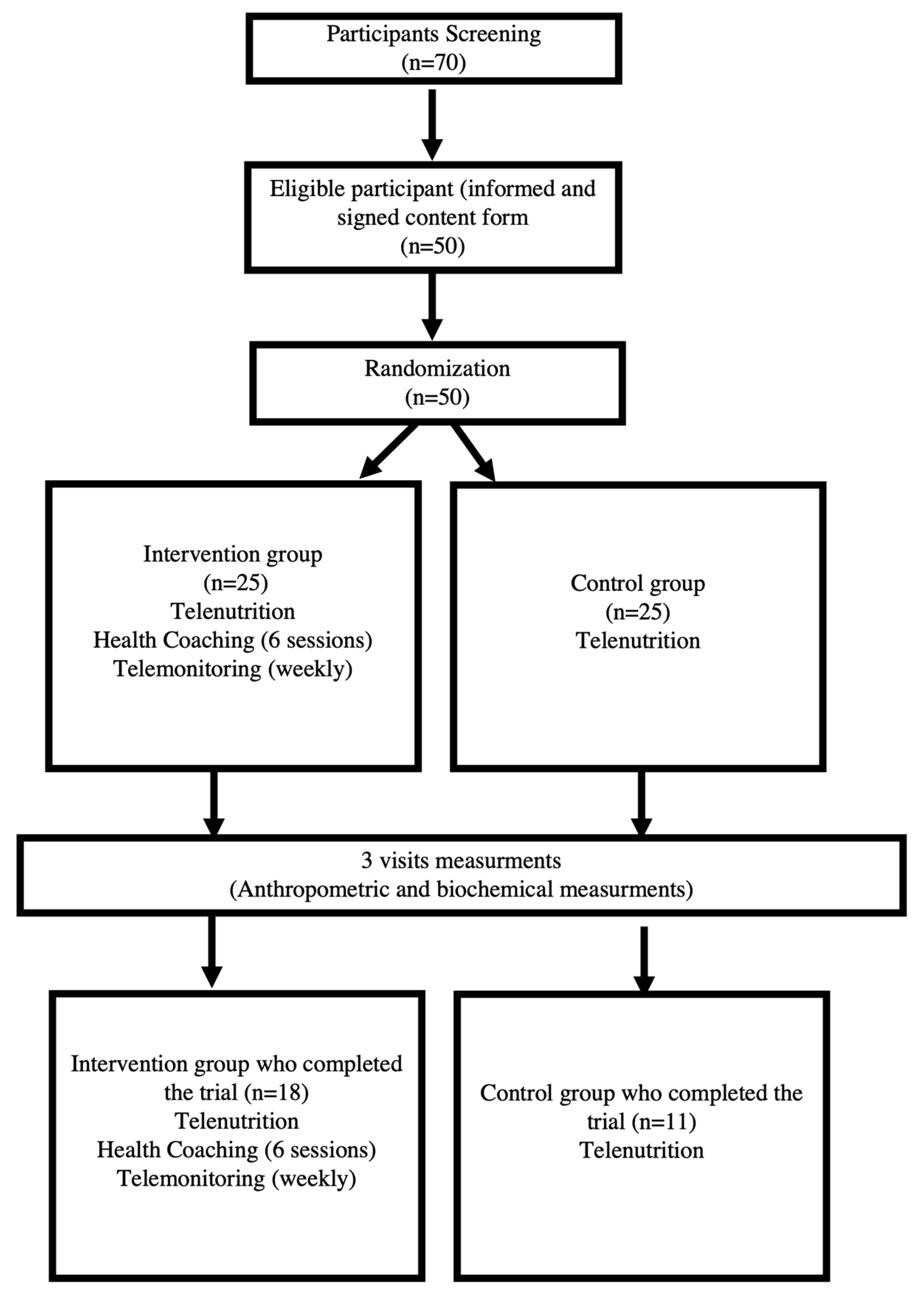

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Program Description

2.4. Anthropometric Measurements and Blood Biochemical Measures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

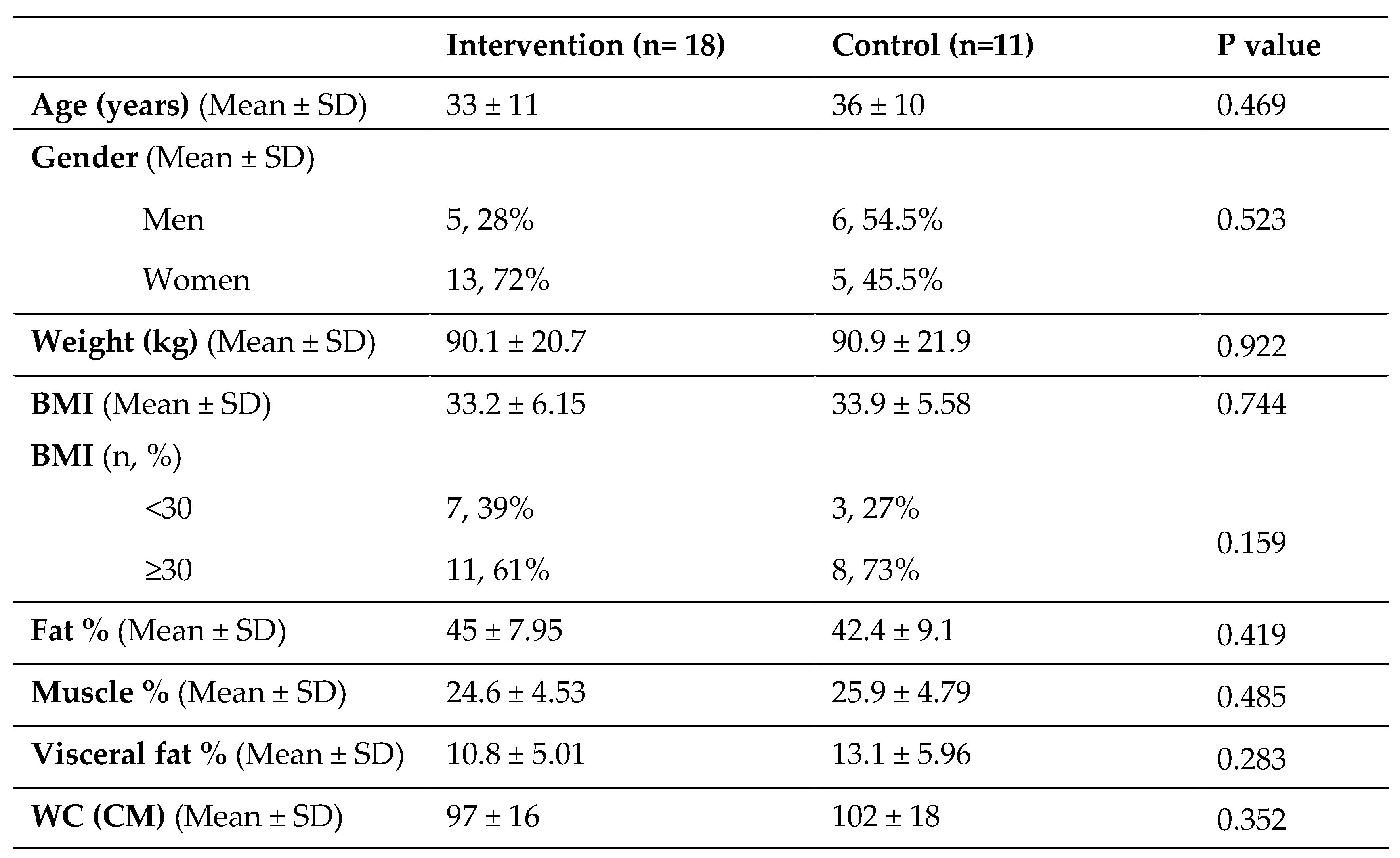

3.1. Participants Characteristics

3.2. Clinical and Biochemical Measurements at All Time-Points

3.3. Changes in Anthropometric and Body Composition Measurements from Baseline at 3 and 6 Months

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.; Min, J.; Khuri, J.; Xue, H.; Xie, B.; Kaminsky, L.A.; L, J.C. Effectiveness of Mobile Health Interventions on Diabetes and Obesity Treatment and Management: Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020, 8, e15400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luley, C.; Blaik, A.; Götz, A.; Kicherer, F.; Kropf, S.; Isermann, B.; Stumm, G.; Westphal, S. Weight loss by telemonitoring of nutrition and physical activity in patients with metabolic syndrome for 1 year. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014, 33, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bookari, K.; Arrish, J.; Alkhalaf, M.M.; Alharbi, M.H.; Zaher, S.; Alotaibi, H.M.; Tayyem, R.; Al-Awwad, N.; Qasrawi, R.; Allehdan, S.; et al. Perspectives and practices of dietitians with regards to social/mass media use during the transitions from face-to-face to telenutrition in the time of COVID-19: A cross-sectional survey in 10 Arab countries. Front Public Health. 2023, 11, 1151648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnagnarella, P.; Ferro, Y.; Monge, T.; Troiano, E.; Montalcini, T.; Pujia, A.; Mazza, E. Telenutrition: Changes in Professional Practice and in the Nutritional Assessments of Italian Dietitian Nutritionists in the COVID-19 Era. Nutrients. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelnuovo, G.; Manzoni, G.M.; Cuzziol, P.; Cesa, G.L.; Tuzzi, C.; Villa, V.; Liuzzi, A.; Petroni, M.L.; Molinari, E. TECNOB: study design of a randomized controlled trial of a multidisciplinary telecare intervention for obese patients with type-2 diabetes. BMC Public Health. 2010, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelnuovo, G.; Manzoni, G.M.; Cuzziol, P.; Cesa, G.L.; Corti, S.; Tuzzi, C.; Villa, V.; Liuzzi, A.; Petroni, M.L.; Molinari, E. TECNOB Study: Ad Interim Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial of a Multidisciplinary Telecare Intervention for Obese Patients with Type-2 Diabetes. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2011, 7, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastern Mediterranean Region intercountry dialogue on the WHO Acceleration Plan to STOP Obesity. East Mediterr Health J. 2023, 29, 491. [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Telemedicine for healthcare: Capabilities, features, barriers, and applications. Sens Int. 2021, 2, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, P.K. A review of weight loss programs delivered via the Internet. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006, 21, 251–258; quiz 259–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.O.; Thompson, H.; Wyatt, H. Weight maintenance: what’s missing? J Am Diet Assoc. 2005, 105, S63–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, R.R.; Tate, D.F.; Gorin, A.A.; Raynor, H.A.; Fava, J.L. A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2006, 355, 1563–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, W.; Zhou, K.; Waddell, E.; Myers, T.; Dorsey, E.R. Improving Access to Care: Telemedicine Across Medical Domains. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021, 42, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ofi, E.A.; Mosli, H.H.; Ghamri, K.A.; Ghazali, S.M. Management of postprandial hyperglycaemia and weight gain in women with gestational diabetes mellitus using a novel telemonitoring system. J Int Med Res. 2019, 47, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, F.B.; Oliveira, N.S.; Costa, M.G.O.; Andrade, A.C.S.C.; Costa, M.L.; Teles, A.C.S.J.; Mendes-Netto, R.S. Impact of telenutrition protocols in a web-based nutrition counseling program on adult dietary practices: Randomized controlled pilto study. Patient Educ Couns 2024, 118, 108005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura Marra, M.; Lilly, C.L.; Nelson, K.R.; Woofter, D.R.; Malone, J. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a telenutrition weight loss intervention in middle-aged and older men with multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzmar, I.E.; Cortés-Castell, E.; Rizo, M. Effectiveness of telenutrition in a women’s weight loss program. PeerJ. 2015, 3, e748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezgi, M.a.K., C. Investigating the Weight Loss Success of Clients Participated in Different Telenutrition Intervention Groups: A Cross-Sectional Design. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Health Sciences. 2022, 7.

- Kempf, K.; Röhling, M.; Martin, S.; Schneider, M. Telemedical coaching for weight loss in overweight employees: a three-armed randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2019, 9, e022242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, S.; Curtain, S. Health coaching as a lifestyle medicine process in primary care. Aust J Gen Pract. 2019, 48, 677–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, J. Integrative Nutrition: Feed Your Hunger for Health and Happiness. 3rd ed. 2014: Integrative Nutrition Publishing.

- Nicolucci, A.; Cercone, S.; Chiriatti, A.; Muscas, F.; Gensini, G. A Randomized Trial on Home Telemonitoring for the Management of Metabolic and Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015, 17, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.C.; Hoover, K.W.; Keller, S.; Replogle, W.H. Mississippi Diabetes Telehealth Network: A Collaborative Approach to Chronic Care Management. Telemed J E Health. 2020, 26, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, D.; Woods, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chandra, S.; Summers, R.L.; Jones, D.W. Home Blood Pressure Telemonitoring With Remote Hypertension Management in a Rural and Low-Income Population. Hypertension. 2021, 78, 1927–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaud, T.L.; Ern, J.; Scoggins, D.; Su, D. Assessing the Impact of Telemonitoring-Facilitated Lifestyle Modifications on Diabetes Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Telemed J E Health. 2021, 27, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekker, M.N.; Koster, M.P.H.; Keusters, W.R.; Ganzevoort, W.; de Haan-Jebbink, J.M.; Deurloo, K.L.; Seeber, L.; van der Ham, D.P.; Zuithoff, N.P.A.; Frederix, G.W.J.; et al. Home telemonitoring versus hospital care in complicated pregnancies in the Netherlands: a randomised, controlled non-inferiority trial (HoTeL). Lancet Digit Health. 2023, 5, e116–e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldhamin, R.A.; Al-Ghareeb, G.; Al Saif, A.; Al-Ahmed, Z. Health Coaching for Weight Loss Among Overweight and Obese Individuals in Saudi Arabia: A Retrospective Analysis. Cureus. 2023, 15, e41658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.E.; Alencar, M.K.; Coakley, K.E.; Swift, D.L.; Cole, N.H.; Mermier, C.M.; Kravitz, L.; Amorim, F.T.; Gibson, A.L. Telemedicine-Based Health Coaching Is Effective for Inducing Weight Loss and Improving Metabolic Markers. Telemed J E Health. 2019, 25, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Valk, E.S.; Savas, M.; van Rossum, E.F.C. Stress and Obesity: Are There More Susceptible Individuals? Curr Obes Rep. 2018, 7, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghrouz, A.K.; Noohu, M.M.; Dilshad Manzar, M.; Warren Spence, D.; BaHammam, A.S.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R. Physical activity and sleep quality in relation to mental health among college students. Sleep Breath. 2019, 23, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMarzooqi, M.A.; Saller, F. Physical Activity Counseling in Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review of Content, Outcomes, and Barriers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murase, K.; Minami, T.; Hamada, S.; Gozal, D.; Takahashi, N.; Nakatsuka, Y.; Takeyama, H.; Tanizawa, K.; Endo, D.; Akahoshi, T.; et al. Multimodal Telemonitoring for Weight Reduction in Patients With Sleep Apnea: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Chest. 2022, 162, 1373–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, C.M.; Groth, S.W.; Graham, M.L.; Reschke, J.E.; Strawderman, M.S.; Fernandez, I.D. The effectiveness of an online intervention in preventing excessive gestational weight gain: the e-moms roc randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alencar, M.K.; Johnson, K.; Mullur, R.; Gray, V.; Gutierrez, E.; Korosteleva, O. The efficacy of a telemedicine-based weight loss program with video conference health coaching support. J Telemed Telecare. 2019, 25, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, D.M.; Martin, C.K.; Redman, L.M.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Lettieri, S.; Levine, J.A.; Bouchard, C.; Schoeller, D.A. Effect of dietary adherence on the body weight plateau: a mathematical model incorporating intermittent compliance with energy intake prescription. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014, 100, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaput, J.P.; Drapeau, V.; Hetherington, M.; Lemieux, S.; Provencher, V.; Tremblay, A. Psychobiological effects observed in obese men experiencing body weight loss plateau. Depress Anxiety. 2007, 24, 518–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council Committee on, D.; Health, in Diet and Health: Implications for Reducing Chronic Disease Risk. 1989, National Academies Press (US) Washington (DC).

- Flodgren, G.; Rachas, A.; Farmer, A.J.; Inzitari, M.; Shepperd, S. Interactive telemedicine: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015, 2015, Cd002098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.L.; Haring, O.M.; Wortman, P.M.; Watson, R.A.; Goetz, J.P. Medical information systems: assessing impact in the areas of hypertension, obesity and renal disease. Med Care. 1982, 20, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Khonsari, S.; Gallagher, R.; Gallagher, P.; Clark, A.M.; Freedman, B.; Briffa, T.; Bauman, A.; Redfern, J.; Neubeck, L. Telehealth interventions for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019, 18, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayes, J.; Schloss, J.; Sibbritt, D. A randomised controlled trial assessing the effect of a Mediterranean diet on the symptoms of depression in young men (the ‘AMMEND’ study): a study protocol. Br J Nutr. 2021, 126, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafkan, L.; Choobineh, M.A.; Shojaei, M.; Bozorgi, A.; Sharifi, M.H. How do overweight people dropout of a weight loss diet? A qualitative study. BMC nutrition. 2021, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, A.; Langley-Evans, S.C.; Harrington, M.; Swift, J.A. Setting targets leads to greater long-term weight losses and ‘unrealistic’ targets increase the effect in a large community-based commercial weight management group. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016, 29, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable/timepoint | Group | n | Mean | SD | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic BP | |||||

| Baseline | Intervention | 18 | 131.4 | 16.9 | 0.868 |

| Control | 11 | 132.5 | 16.2 | ||

| 3 months | Intervention | 18 | 119.0 | 10.4 | 0.463 |

| Control | 11 | 122.6 | 15.3 | ||

| 6 months | Intervention | 16 | 126.0 | 16.1 | 0.961 |

| Control | 9 | 126.3 | 16.2 | ||

| Diastolic BP | |||||

| Baseline | Intervention | 18 | 77.8 | 13.8 | 0.026 |

| Control | 11 | 89.0 | 9.8 | ||

| 3 months | Intervention | 18 | 75.1 | 7.3 | 0.304 |

| Control | 11 | 78.4 | 9.7 | ||

| 6 months | Intervention | 16 | 81.3 | 9.7 | 0.939 |

| Control | 9 | 81.6 | 9.2 | ||

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | |||||

| Baseline | Intervention | 18 | 5.23 | 0.73 | 0.207 |

| Control | 11 | 5.67 | 1.11 | ||

| 3 months | Intervention | 18 | 4.68 | 0.94 | 0.16 |

| Control | 11 | 5.27 | 1.25 | ||

| 6 months | Intervention | 16 | 4.94 | 0.68 | 0.052 |

| Control | 9 | 5.61 | 0.82 | ||

| HDL (mmol/L) | |||||

| Baseline | Intervention | 18 | 1.35 | 0.25 | 0.958 |

| Control | 11 | 1.35 | 0.19 | ||

| 3 months | Intervention | 18 | 1.14 | 0.20 | 0.509 |

| Control | 11 | 1.09 | 0.18 | ||

| 6 months | Intervention | 16 | 1.14 | 0.22 | 0.421 |

| Control | 9 | 1.06 | 0.19 | ||

| LDL (mmol/L) | |||||

| Baseline | Intervention | 18 | 4.59 | 0.77 | 0.477 |

| Control | 11 | 4.90 | 1.54 | ||

| 3 months | Intervention | 18 | 3.47 | 1.03 | 0.243 |

| Control | 11 | 3.98 | 1.24 | ||

| 6 months | Intervention* | 16 | 3.49 | 0.59 | 0.034 |

| Control | 9 | 4.17 | 0.85 | ||

| TG (mmol/L) | |||||

| Baseline | Intervention | 18 | 1.05 | 0.47 | 0.431 |

| Control | 11 | 1.19 | 0.40 | ||

| 3 months | Intervention* | 18 | 0.97 | 0.35 | 0.043 |

| Control | 11 | 1.38 | 0.67 | ||

| 6 months | Intervention* | 16 | 0.99 | 0.52 | 0.037 |

| Control | 9 | 1.47 | 0.40 | ||

| Control | 11 | 7.79 | 12.73 | ||

| 6 months | Intervention | 16 | 4.36 | 4.93 | 0.115 |

| Control | 9 | 8.11 | 5.73 | ||

| Variable/timepoint | Group | n | Mean | SD | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | |||||

| Δ at 3 months | Intervention | 18* | -3.93 | 4.58 | 0.02 |

| Control | 11 | -0.19 | 2.50 | ||

| Δ at 6 months | Intervention | 16 | -3.11 | 6.02 | 0.337 |

| Control | 9 | -1.02 | 2.69 | ||

| BMI | |||||

| Δ at 3 months | Intervention | 18* | -1.46 | 1.66 | 0.025 |

| Control | 11 | -0.14 | 1.01 | ||

| Δ at 6 months | Intervention | 16 | -1.18 | 2.35 | 0.44 |

| Control | 9 | -0.51 | 1.09 | ||

| Fat % | |||||

| Δ at 3 months | Intervention | 18* | -2.94 | 2.80 | 0.048 |

| Control | 11 | -0.89 | 1.77 | ||

| Δ at 6 months | Intervention | 16 | -1.64 | 3.12 | 0.306 |

| Control | 9 | -0.46 | 1.76 | ||

| Muscle % | |||||

| Δ at 3 months | Intervention | 16 | 1.68 | 1.77 | 0.051 |

| Control | 11 | 0.56 | 1.05 | ||

| Δ at 6 months | Intervention | 15 | 0.46 | 2.89 | 0.866 |

| Control | 9 | 0.29 | 0.93 | ||

| Visceral Fat (g) | |||||

| Δ at 3 months | Intervention | 16* | -0.94 | 1.39 | 0.048 |

| Control | 11 | -0.09 | 0.70 | ||

| Δ at 6 months | Intervention | 15 | -0.80 | 1.52 | 0.295 |

| Control | 9 | -0.22 | 0.67 | ||

| WC (CM) | |||||

| Δ at 3 months | Intervention | 18 | -5.69 | 4.47 | 0.207 |

| Control | 11 | -3.68 | 3.26 | ||

| Δ at 6 months | Intervention | 16 | -4.72 | 7.30 | 0.959 |

| Control | 9 | -4.56 | 7.73 |

| Variable/timepoint | Group | n | Mean | SD | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | |||||

| Δ% at 3 months | Intervention | 18* | -4.06 | 4.26 | 0.022 |

| Control | 11 | -0.48 | 3.00 | ||

| Δ% at 6 months | Intervention | 16 | -3.46 | 6.49 | 0.332 |

| Control | 9 | -1.17 | 3.14 | ||

| BMI | |||||

| Δ% at 3 months | Intervention | 18* | -4.35 | 4.56 | 0.024 |

| Control | 11 | -0.63 | 3.03 | ||

| Δ% at 6 months | Intervention | 16 | -3.84 | 6.60 | 0.324 |

| Control | 9 | -1.46 | 3.25 | ||

| Fat % | |||||

| Δ% at 3 months | Intervention | 18 | -6.73 | 6.51 | 0.075 |

| Control | 11 | -2.56 | 4.66 | ||

| Δ% at 6 months | Intervention | 16 | -4.33 | 9.24 | 0.312 |

| Control | 9 | -0.96 | 3.93 | ||

| Muscle % | |||||

| Δ% at 3 months | Intervention | 16* | 7.08 | 7.87 | 0.033 |

| Control | 11 | 1.90 | 3.91 | ||

| Δ% at 6 months | Intervention | 15 | 1.61 | 11.35 | 0.929 |

| Control | 9 | 1.26 | 3.97 | ||

| Visceral Fat (g) | |||||

| Δ% at 3 months | Intervention | 16 | -7.20 | 9.50 | 0.061 |

| Control | 11 | -1.52 | 5.46 | ||

| Δ% at 6 months | Intervention | 15 | -6.02 | 13.18 | 0.376 |

| Control | 9 | -1.75 | 6.41 | ||

| WC (CM) | |||||

| Δ% at 3 months | Intervention | 18 | -5.69 | 4.13 | 0.149 |

| Control | 11 | -3.57 | 2.92 | ||

| Δ% at 6 months | Intervention | 16 | -4.59 | 6.64 | 0.876 |

| Control | 9 | -4.15 | 6.82 |

| Intervention | Control | P-value a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | |||

| <30 (34.5%) | -1.86 (2.19) | -1.27 (1.51) | 0.686 |

| ≥30 (65.5%) | -5.25 (5.28) | 0.21 (2.75) | 0.017 |

| Gender | |||

| Male (37.9%) | -7.8 (5.44)* | -0.4 (2.04) | 0.035 |

| Female (62.1%) | -2.44 (3.34) | 0.06 (3.2) | 0.171 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).