1. Introduction

The global prevalence of obesity has surged more than threefold since the 1970s, with around 3 billion people now living with excess weight or obesity [

1]. Many experts attribute this rise to the multifaceted nature of obesity, linking it to various economic, social, environmental, and neurological factors [

2,

3,

4]. This complexity has made it difficult for weight-loss interventions to produce consistent and long-term success for most individuals [

5,

6]. Moreover, the accessibility and adherence to effective weight-loss programs may be a crucial yet underappreciated factor in the global rise in obesity [

7].

In recent years, Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) have emerged as a promising category of weight-loss drugs. Multiple clinical trials have highlighted their unprecedented effectiveness in both diabetic and non-diabetic groups [

8,

9,

10]. In non-diabetic groups who combine Semaglutide therapy with lifestyle counselling, participants average a reduction between 14.9 and 16 percent of baseline weight after 68 weeks [

9,

10]. These results are often attributed to the effect of GLP-1 RAs in modulating the neurological pathways involved in satiety [

11,

12]. However, some commentators have raised concerns that these medications are being framed as a cure-all for obesity, rather than as a supplement to sustained lifestyle changes [

13,

14]. Leading health organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) stress that GLP-1 RAs should only ever be prescribed to obesity patients as an adjunct to continuous multidisciplinary lifestyle interventions [

15,

16].

While this recommended treatment approach is sound, accessing and sticking to lifestyle therapy in traditional healthcare settings remains challenging. People with demanding work or family schedules often find it difficult to attend regular consultations with multidisciplinary teams (MDTs)—an issue exacerbated by longer waiting times for GP appointments in countries like the UK [

7,

17]. Furthermore, many individuals with overweight or obesity face stigma about their condition and are uncomfortable discussing it in person [

7,

18]. Some have also reported that their GPs fail to offer comprehensive lifestyle advice or referrals to specialists [

7]. Finally, many people with overweight or obesity live too far from healthcare providers to reasonably access quality obesity care [

19,

20].

Digital weight-loss services (DWLSs) have emerged in recent times as a potential solution to these barriers [

21]. DWLSs can help eliminate the psychological and geographical hurdles to obesity treatment by minimizing the need for face-to-face interactions. They also address time constraints by offering services through digital platforms, with many providing the option for asynchronous consultations, which don’t require real-time interaction [

7,

22]. However, the quality of GLP-1 RA-supported DWLSs varies widely. Some services follow WHO and NICE guidelines by offering GLP-1 RAs as a supplement to continuous MDT-led lifestyle coaching, while others provide little more than access to GLP-1 RA prescriptions without follow-up care, fueling concerns about the over-reliance on medication for weight management [

13,

23]. These concerns are compounded by a lack of research on GLP-1 RA-supported DWLSs. At present, only a few quantitative studies have been conducted on such services, including analyses of Australian and British cohorts using Liraglutide and Semaglutide (Ozempic) alongside lifestyle coaching [

24,

25,

26,

27]. While these studies have shown some promising effectiveness and adherence results, several key questions remain unanswered before these DWLS models can be widely adopted. One of the main questions is the extent to which lifestyle coaching design influences engagement and effectiveness outcomes in GLP-1 RA-supported DWLSs. A previous mixed-methods study found that users prefer personalized and proactive coaching styles [

28]. However, that investigation did not assess the extent to which lifestyle coaching preferences affected program outcomes. Another key uncertainty is whether the Semaglutide brand influences weight-loss outcomes in real-world digital environments. While Ozempic and Wegovy have the same active ingredient (Semaglutide), the latter contains a higher maintenance dose and has been marketed by large DWLSs as the more effective variant [

29]. Despite this, and the fact that Wegovy is approved for weight-loss in the UK, US and Australia whereas Ozempic is only approved for the treatment of diabetes [

30,

31,

32], research on Semaglutide-supported DWLSs in these regions appears to be limited to Ozempic cohorts.

This study aims to evaluate how different lifestyle coaching approaches affect patient engagement and weight loss in a large, non-subsidized Wegovy-supported DWLS in the UK. By providing novel insights into both coaching methods and a different Semaglutide brand, this study hopes to contribute valuable information to the growing body of research on real-world DWLSs.

2. Materials and Methods

This study derived from an internal lifestyle coaching experiment initiated by the Juniper UK DWLS and adopted a retrospective control design to achieve its aims. Investigators followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines throughout the entire investigation. The study’s ethics were approved by the Bellberry Limited Human Ethics Committee on 22 November 2023 (No. 2023-05-563-A-1). All study patients consented to the publication of their de-identified data.

Program Overview

The Juniper UK DWLS has operated solely through an app-based platform since its inception in 2021. Prospective users fill out an extensive online pre-consultation form, consisting of over 100 questions about their health history. A pharmacist reviews the responses and often requests additional details such as test results, images, and other medical data to assess program eligibility. Decisions are largely based on the Wegovy prescribing information guidelines, which include body mass index (BMI) cut-offs, contraindications like medullary thyroid cancer, and potential interactions with other medications, such as insulin [

34].

Eligible individuals, upon paying an initial monthly fee of £189 (increasing to £299 when the highest Wegovy dose of 2.4mg is reached), are assigned an MDT consisting of a pharmacist, a dietitian or nutritionist with university credentials, and a nurse. All interactions between patients and their MDT are stored in an encrypted central database on Metabase (an open-source business intelligence tool) to optimize care continuity. Access to this data is limited to MDTs and the Juniper UK analytics team. Before consenting to the program, patients are forwarded a detailed summary of GLP-1 RA side effects. Each patient is provided with a standardized set of Bluetooth-enabled scales to track their weight.

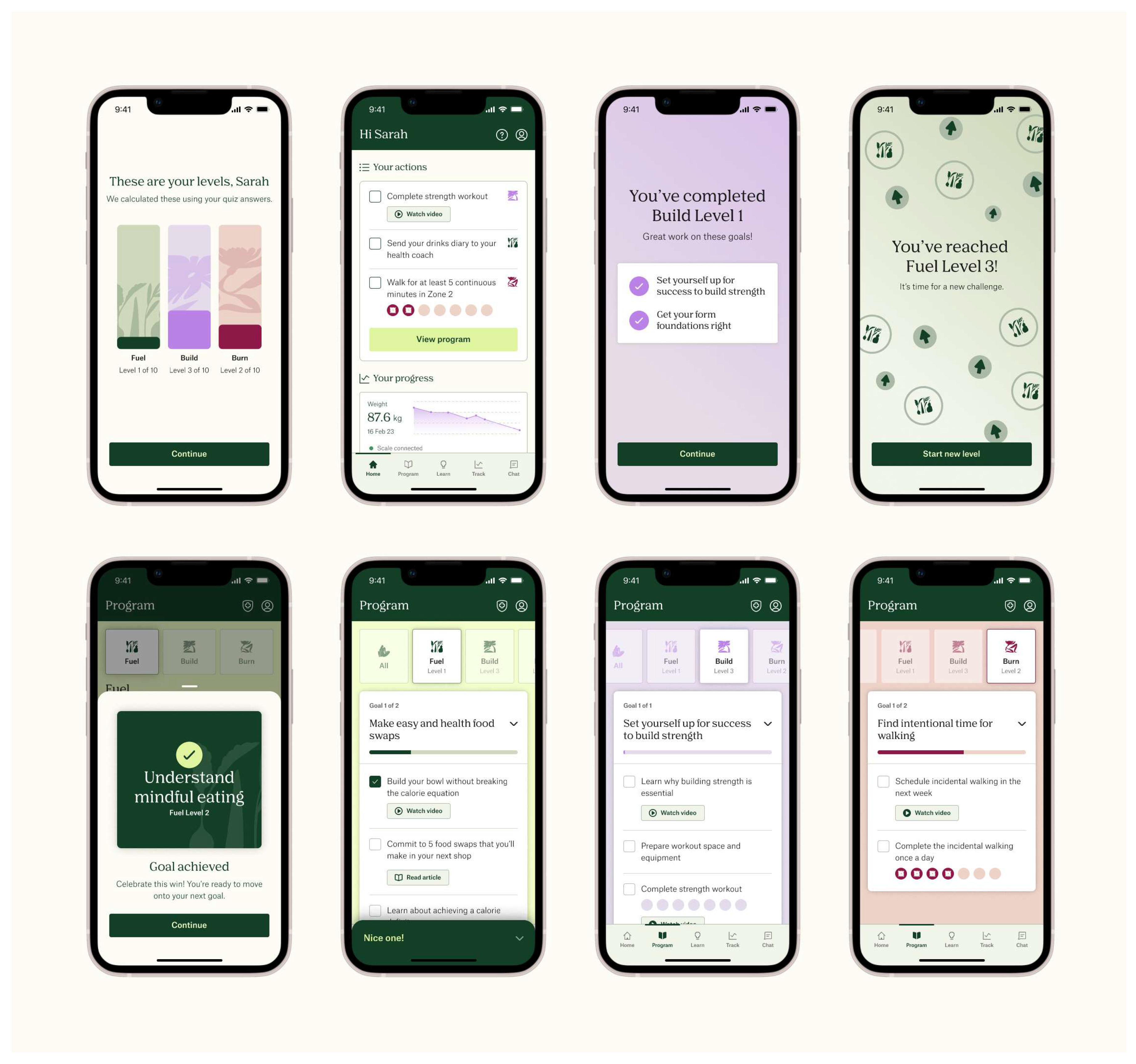

Under the standard Juniper UK DWLS, health coaches send patients a short lifestyle quiz to develop diet and exercise plans. The quiz contains questions that assess patient proficiency with resistance and aerobic training, and nutritional knowledge. Once the lifestyle plan is sent, patients receive an automated message detailing how to use the Juniper app to optimize their results. Although patients can request changes to their lifestyle plan at any time, they are only prompted to consider adjustments during their first mandatory follow-up appointment at five months (though earlier consultations may be arranged at the clinician’s discretion). Similarly, patients can reach out to their health coach whenever they wish, but the app does not proactively prompt them to ask for guidance or update progress using the ‘Action’ or weight tracking features. ‘Actions’ consist of micro diet and exercise goals organized into challenge pillars, which are supported by multimedia educational resources (

Figure 1). Patients are sorted into challenge pillars according to their baseline fitness, as indicated in the lifestyle quiz. The only prompt patients receive under the standard program is a biweekly notification to complete a check-in questionnaire, which asks them to enter weight and program satisfaction data, and offers them a chance to report adverse events. Completing the check-in is optional, and no further reminders are sent. Therefore, the standard Juniper DWLS provides reactive rather than proactive lifestyle coaching.

In December 2023, the Juniper UK strategy team decided to assess the value of a proactive coaching model. This decision followed an internal review, which found that many patients were not consistently engaging with any of the program app’s functionalities such as the ‘Actions’ feature. To conduct this assessment, they delivered proactive coaching to 100 patients who subscribed to Wegovy-supported treatment from January 12, 2024. Patients were selected on a 1 to 1 basis, with the every other patient delivered standard Juniper therapy. The proactive lifestyle coaching protocol included the following differences from the standard ‘reactive’ Juniper program:

an introductory program explainer video, with a step-by-step presentation of each app function

an additional lifestyle preference quiz to provide health coaches with greater capacity for personalizing diet and exercise programs

automated prompts to update ‘Actions’ every three days

requirement of setting accountability dates for each goal

two notifications to complete bi-weekly check-in quizzes

Patients who received proactive coaching followed the same Wegovy titration schedule as standard Juniper UK patients. This schedule adheres to Wegovy prescribing information guidelines and is as follows: 0.25mg weekly for weeks 1 to 4, 0.5mg for weeks 5 to 8, 1mg for weeks 9 to 12, 1.7mg for weeks 13 to 16, and 2.4 mg for week 17 onwards. Due to company budget constraints, the assessment was cancelled after 17 weeks, rather than running for 6 months as originally planned.

Participants

The first 200 patients who subscribed to Wegovy-supported Juniper treatment in the UK from January 12 2024 were allocated to either standard or proactive coaching on a 1-to 1 basis. Patient eligibility was determined by a UK-qualified pharmacist, who followed Wegovy prescribing guidelines for weight-loss therapy. These guidelines include the following BMI cutoffs: 27kg/m2 or greater (overweight) for any patient of non-Caucasian ethnicity and/or at least 1 weight-related comorbidity such as sleep apnea or symptomatic cardiovascular disease; or 30kg/m2 or greater for anyone else. Exclusion criteria included the following contraindications: a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2; acute pancreatitis; a previous acute kidney injury; hypoglycaemia; a severe mental health condition; acute gallbladder disease; known hypersensitivity to Semaglutide or any of the product components; and patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Pharmacists used their discretion in determining whether patients on other oral medications could safely take Semaglutide without experiencing interactions with the latter’s gastric emptying effect. The soul study-specific inclusion criterion was that patients submitted weight data between 100 and 120 days after program commencement.

To maintain objectivity, patients who received proactive coaching were not informed they were part of an internal test, as Juniper UK reasonably assumed that the new coaching protocol would not deliver worse outcomes than the standard model. All patients consented to their de-identified data being used for research purposes.

Measures

Primary endpoints were the mean weight-loss percentage from baseline to 16-week follow up and the mean number of patient messages to their MDT. The study’s secondary endpoints included the mean number of days when patients opened the program app, opened the goal tracker feature, and played a minimum of 80% of an educational video; and the proportion of patients who reached 5, 10 and 15 percent weight loss milestones. Data were only captured in the program app and goal tracker markers if patients had the respective pages open for a minimum of 5 seconds.

Statistical Analysis

All descriptive statistics were reported as means with standard deviations, along with frequency distributions (where relevant). For continuous dependent variables such as weight loss and patient messages, two-sample t-tests were used to compare means between the two study groups. Chi-square tests were conducted to assess the correlation between coaching group and the achievement of 5, 10, and 15 percent weight-loss milestones (yes/no). Pearson correlation tests were used to assess the association between continuous predictor and dependent variables, such as age and number of days when the program app was opened. All statistical analyses and visualizations were conducted on RStudio (version 2023.06.1+524).

3. Results

154 (77%) of the 200 study patients satisfied the study’s inclusion criterion, consisting of 70 patients from the proactive coaching group and 84 from the reactive group. Of the 44 patients who were excluded, 32 discontinued the program before week-16 follow-up and 12 failed to submit weight data within 100 and 120 days of program commencement. The mean age of the final cohort was 43.03 (±10.7) and the mean BMI was 33.87 (±6.12) kg/m

2 (

Table 1). Most patients were female (90.26%) and of Caucasian ethnicity (82.47%). Patients submitted follow-up weight data at a mean of 112.88 (±5.22) days after program initiation.

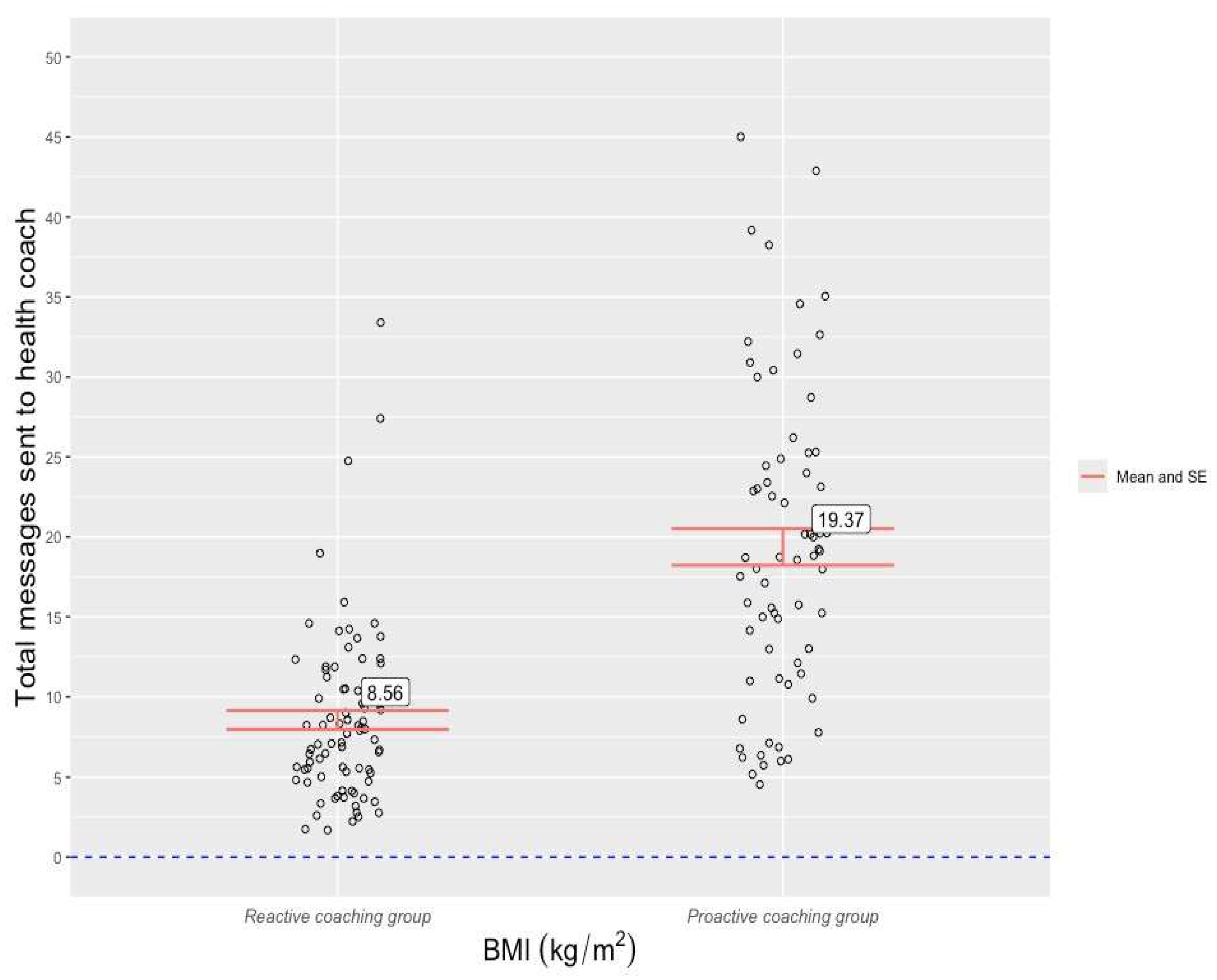

The mean weight-loss percentage from baseline to week-16 follow-up was 9.47(±5.72) across the entire cohort. Patients in the proactive coaching group recorded a higher mean weight loss percentage (10.09 (±4.42)) than those from the reactive coaching group (8.96 (±6.6)), but a two-sample t-test revealed that this difference was not statistically significant, t(152) = -1.22 , p = .22) . For the entire cohort, the mean number of patient-to-coach messages was 13.05 (±9.03). A two-sample t-test found that proactive coaching patients sent a statistically higher number of messages to their health coaches (19.37(±9.58) than reactive group patients (8.55(±5.39)), t(152) = 8.81, p <0.001) (

Figure 2).

A statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups in the number of days in which they opened the Juniper app, t(152) = -2.72 , p <0.001). Whereas the proactive coaching group opened the app at a mean of 49.31 (±21.9) days throughout the study period, the reactive group recorded a mean of 40.06 (±20.3) days. Although a higher mean was observed in the proactive coaching group for number of days opening the ‘Action’ tracker (32.99 vs 28.5) and the number of days opening educational videos (5.07 vs 4.1), t-tests found that these differences were not statistically significant (Action tracker: t(152) = -1.43 , p = 0.15; videos: t(152) = -1.89 , p = 0.06.

Chi-square tests detected no statistical differences between in the two groups in the proportion of patients who reached the 5 (X2(1, N = 154 = 1.68, p = 0.19), 10 (X2(1, N = 154 = 0.07, p = 0.79), or 15 (X2(1, N = 154 = 0.06, p = 0.8) percent weight-loss milestones. Across the full cohort, 84.44 % of patients lost a clinically meaningful amount of weight (≥5%), 47.4% lost at least 10 percent of their baseline weight, and 14.93% lost at least 15 percent.

Pearson tests found that age did not correlate with the number of patient messages (r(152) = -0.91, p = 0.36), weight loss (r(152) = -1.57 , p = 0.12), or app opening frequency (r(152) = -0.05 , p = 0.95). Initial BMI was also observed to have no significant effect on patient messages (r(152) = 0.14 , p = 0.89), weight loss (r(152) = 0.27 , p = 0.79), or app opening frequency (r(152) = -1.06 , p = 0.29). Given the low number of non-Caucasian ethnic groups in the sample, a binary ethnicity variable was created (Caucasian vs non-Caucasian). Two-sample t-tests revealed that ethnicity did not significantly correlate with patient messages t(152) = -1.08 , p = 0.28), weight loss t(152) = 0.98 , p = 0.32), or app opening frequency t(152) = 0.45 , p = 0.65). Patient gender was found to be associated with weight loss (t(152) = 1.89 , p = 0.04)., but not the number of patient messages (t(152) = 0.11 , p = 0.9). or days opening the Juniper app (t(152) = 0.95 , p = 0.34). Whereas female patients lost a mean of 9.76 (±5.74) percent of their baseline weight, the mean weight-loss percentage among male patients was 6.88 (±5.06).

64.3 percent of patients in the proactive group reported at least one side effect compared to 62.9 percent in the reactive group, with a chi-square test revealing that this difference was not statistically significant (

X2(1,

N = 154 = 0.03,

p = 0.85) (

Table 2). Of all reported side effects, only 2.9% and 3.6% were considered severed in the proactive and reactive groups, respectively. The two most common types of side effects in both groups were gastrointestinal issues and headaches.

4. Discussion

To the knowledge of the authors, this was the first study to measure the impact of lifestyle coaching design on engagement and effectiveness in a GLP-1 RA-supported DWLS. Previous research had found that such services can improve access to obesity care relative to in-person services [

7], and that patients tend to prefer the lifestyle coaching component of GLP-1 supported-DWLSs to be more proactive and personalized rather than relying on automated and/or patient-led prompts [

32]. However, no studies had investigated whether this preference translated to improved patient outcomes or engagement. Moreover, while previous effectiveness and adherence studies had been conducted on Semagltuide-supported Juniper DWLS cohorts [

25,

26,

27,

33], these cohorts used the off-label brand of Semaglutide (Ozempic) rather than the brand that has been approved for weight-loss therapy throughout the Western World (Wegovy). The findings from this study therefore add some important foundational layers to the emerging field of literature of GLP-1-RA-supported DWLSs.

The analysis discovered that patients of the Juniper UK DWLS who received proactive coaching sent a statistically higher number of messages to their health coach over the 16-week study period than patients whose coaching was reactive (19.37 vs 8.55). These mean figures convert to an average of 1.2 messages per week for the proactive group and 0.53 messages per week for the reactive group. Although messaging frequency guidelines are yet to be established in obesity or chronic care settings, the observed message frequency rate in the proactive group appears satisfactory from a care continuity perspective. Moreover, the rates observed in the two arms of this study lay a foundation for ongoing research into engagement with GLP-1 RA-supported DWLSs. Proactive coaching patients also opened the Juniper app on a significantly higher number of days than reactive coaching patients (49.31 vs 40.06 days). However, this app use disparity was considerably smaller (

t = -2.72) than the one found in messaging frequency (

t = -8.81) and may be of limited real-world significance. It is feasible that various patients opened the app without deriving any meaningful engagement benefits, such as thinking about exercise or recommended meals. Although no statistical differences were observed in the other engagement markers, the observed cohort-wide rate of opening the Action tracker (30.54 days over study period) was arguably significant in itself, as it indicated that Juniper patients engaged with goal-specific content every 3.7 days. Again, no existing data is available for comparison, but the engagement rate would feasibly satisfy future standards of obesity care continuity. The analysis also found that health coaching style does not significantly affect weight-loss outcomes in short-term Semaglutide-supported DWLSs. This discovery could possibly be explained by the study’s relatively short duration. Previous Semaglutide investigations have shown that a disproportionately high amount of weight loss tends to occur during the first three months of such interventions [

9,

10]. Had this study lasted for the intended 26 weeks, a significant association between weight loss and coaching style may have been observed. Although the difference in mean weight loss between the two groups was not statistically significant, some observers may consider the disparity between 10.1% (proactive group) and 8.9% (reactive group) to be clinically meaningful. It is possible that a correlation between weight loss and messaging frequency would have manifested over a longer study period as well, given the decreasing marginal effect of Semaglutide after the first few months of treatment.

Despite the fact that no statistical correlation was observed between coaching style and weight loss, the mean 16-week weight-loss percentage of 10.1(±4.42) observed in the proactive group can reasonably be interpreted as being comparable to the 10.73% reported in a previous 22-week study of a Juniper UK cohort using Ozempic [

26]. Some observers might be tempted to suggest that this study’s figure was on a steeper trajectory, highlighting that the previous Juniper study used a 1mg maintenance dose of Ozempic [

26], whereas this study’s cohort did not reach their maintenance Wegovy dose (2.4mg from week 17 onwards). However, as expressed earlier, a disproportionate amount of weight loss tends to occur in the early months of Semaglutide-supported interventions, and therefore no stronger conclusions can be drawn from this study about Wegovy’s effect relative to Ozempic in a comprehensive real-world DWLS setting. Future research should also explore the effect of different GLP-1-supported health coaching methods over longer periods and via other DWLS providers. The finding that female patients lost significantly more weight than male patients (9.76% vs 6.88%) is notable. While previous studies of the Juniper DWLS have not detected the same trend [

24,

26,

33], neither those studies nor the current one have contained a high percentage of male patients. The gender weight-loss discrepancy found in this study, therefore, highlights the need for a focused investigation of male DWLS patients.

This study’s strengths included its novelty (i.e., its investigation of Wegovy and different lifestyle coaching styles in a real-world DWLS), its non-interference with patient experience in the Juniper program, and its low drop-out rate (23%) relative to previous Juniper studies with comparable exclusion criteria [

24,

26,

33]. The study also contained several limitations. Firstly, the study duration was cut from 26 weeks down to 16 weeks due to Juniper’s budget constraints. Although the study still generated multiple significant outcomes, further important discoveries may have been made had the study continued for its intended duration. Budget constraints are a common challenge of real-world investigations, however ongoing DWLS evidence generation could feasibly attract funding opportunities to overcome this issue in the future. Secondly, the sample included a disproportionately high percentage of females and Caucasians, and therefore was not representative of the diverse British population. Thirdly, weight data within the study period (up to 120 days) were missing from patients who failed to satisfy the data entry inclusion criterion and could not be reported. And finally, investigators could not account for the reasons behind the decision of 44 patients to discontinue the program before study completion.

5. Conclusions

Previous research had found that Semaglutide-supported DWLSs can be effective in treating non-diabetic patients with overweight and obesity, and that patients tend to prefer the lifestyle coaching component of these services to be proactive and personalized rather than reactive and standardized. However, no previous study had assessed the degree to which these different coaching methods affect patient engagement and effectiveness in a non-subsidized DWLS that supplements coaching with the only variant of Semaglutide that is currently approved for weight-loss in the UK (Wegovy). The findings from this study indicate that a proactive coaching style leads to better patient engagement with DWLS health coaches and that Wegovy has a comparable effect to Ozempic as a supplement to DWLS coaching. Research of longer duration is needed to determine whether proactive and personalized coaching improves weight-loss outcomes in Semaglutide-supported DWLSs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.,N.L., and M.V.; methodology, L.T, L.L., M.V and N.L; validation, L.T, L.L., and M.V.; formal analysis, L.T and M.V..; investigation, L.T. and M.V; resources, L.L. and N.L.; data curation, L.T, L.L., and N.L..; writing—original draft preparation, L.T..; writing—review and editing, L.T, and M.V; supervision, L.T., and N.L; project administration, L.T, L.L., and N.L.; visualization, L.T; software, L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional review board (or ethics committee) of the Bellberry Ethics Committee (No. 2023-05-563-PRE-1, 22 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Eucalyptus patients consented to the service’s privacy policy at subscription, which includes permission to use their identified data for research. However, for this study investigators only required de-identified data for these patients

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all patients, clinicians and auditors involved in the Eucalyptus weight loss program over the study period.

Conflicts of Interest

LT, MV, L.L and N.L are paid a salary by Eucalyptus (Juniper parent company).

References

- World Obesity Federation. Prevalence of Obesity, 2024. Available from https://www.worldobesity.org/about/about-obesity/prevalence-of-obesity.

- Anekwe, C., Jarrell, A., Townsend, M., et al. Socioeconomics of Obesity. Curr Obes Rep 2020;9:272-279.

- Javed Z, Valero-Elizondo J, Maqsood M, et al. Social determinants of health and obesity: Findings from a national study of US adults. Obesity (Silver Spring)2022;30(2):491–502.

- Verde L, Frias-Toral E, Cardenas D. Editorial: Environmental factors implicated in obesity. Front Nutr 2023;10:1171507.

- Hall, K., Kahan, S. Maintenance of lost weight and long-term management of obesity. Med Clin North Am 2018; 102:183-197.

- Finucane, F., Gibson, I., Hughes, R., et al. Factors associated with weight loss and health gains in a structured lifestyle modification programme for adults with severe obesity: a prospective cohort study.

- Talay, L., Vickers, M., Loftus, S. Why people with overweight and obesity are seeking care through digital obesity services: A qualitative analysis of patients from Australia’s largest digital obesity provider.

- Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al. A randomized controlled trial of 3.0mg of Liraglutide in weight management. N Engl J Med 2015;373(1):11–22. [CrossRef]

- Wilding J, Batterham R, Calanna S, et al. Once-weekly Semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med 2021;384(11):989–1002.

- Davies, M., Faerch, L., Jeppesen, O., et al. Semaglutide 2.4mg once a week in adults with overweight or obesity, and type 2 diabetes (Step 2): a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021;397:971-984.

- Kim, M. The neural basis of weight control and obesity. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2022; 54:347-348.

- Ard, J., Fitch, A., Fruh, S., et al. Weight loss and maintenance related to the mechanism of action of Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists. Adv Ther. 2021; 2821-2839.

- Tullman, G. Weight loss drugs are not the only answer: Why we must redefine the obesity journey, Jan 10, 2024. World Economic Forum. Available from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/01/glp-1s-are-not-the-only-answer-why-we-must-redefine-the-obesity-journey/.

- Dowsett, G., Yeo, G. Are GLP-1R agonists the long-sought-after panacea for obesity? Trends Mol Med, 2023;29:777-779.

- World Health Organization. Health Service Framework for Prevention and Management of Obesity. Geneva, 2023.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Semaglutide for managing overweight and obesity; Sep 2023.

- NHS England. Appointments in General Practice, November 2023. NHS Digital, 2024.

- Crompvoets, P., Nieboer, A., van Rossum, E. Perceived weight stigma in healthcare settings among adults living with obesity: A cross-sectional investigation of the relationship with patient characteristics in person-centred care. Health expect, 2024;27:e13954.

- Prior, S., Luccisano, S., Kilpatrick, M. Assessment and management of obesity and self-maintenance (AMOS): An evalutation of a rural, regional multidisciplinary program. Int J Environ Res public Health 2022;19:12894.

- Hill, J., You, W., Zoellner, J. Disparities in obesity among rural and urban residents in a health disparate region. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1051.

- Golovaty, I., Hagan, S. Direct-to-consumer platforms for new antiobesity medications—concerns and potential opportunities. N Eng J Med, 2024;390:677-680.

- Hinchliffe, N., Capehorn, M., Bewick. M., et al. The potential role of digital health in obesity care, 2022;39:4397-4412.

- Payne, H. No doctor, no script, no worries: Here’s your Ozempic. The Medical Republic, 10 May 2024. Available from https://www.medicalrepublic.com.au/no-doctor-no-script-no-worries-heres-your-ozempic/107426.

- Talay, L.; & Alvi, O. Digital healthcare solutions to better achieve the weight loss outcomes expected by payors and patients. Diabetes Obes. Metab 2024, 26, 2521–2523. [CrossRef]

- Talay, L. & Vickers, M. Patient adherence to a real-world digital, asynchronous weight program in Australia That Combines Behavioural and GLP-1 RA Therapy: A Mixed Methods Study. Behavior Sciences, 2024;14:480. [CrossRef]

- Talay, L. & Vickers, M. Effectiveness and care continuity in an app-based, GLP-1 RA-supported weight-loss service for women with overweight and obesity in the UK: A real-world retrospective cohort analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab 2024,26:2984-2987. [CrossRef]

- Talay, L. & Vickers, M. Patient adherence to a digital real-world GLP-1 RA-supported weight-loss program in the UK: A retrospective cohort study. J Community Med Public Health 2024. [CrossRef]

- Talay, L. Vickers, M., Wu, S. Patient satisfaction with an Australian digital weight-loss service: A comparative retrospective analysis. Telemedicine Reports 2024;5:181-186. [CrossRef]

- Weiser, P., Wilson, A. Wegovy vs Ozempic: what is the difference? Ro Weight Loss, May 21, 2024. Available from https://ro.co/weight-loss/wegovy-vs-ozempic/.

- Suran, M. As Ozempic’s popularity soars, here’s what to know about Semaglutide and weight loss. JAMA, 2023;19:1627-1629.

- Prillaman, M. Obesity drugs aren’t always forever. What happens when you quit? Nature, 16 April 2024. Available from https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-01091-8.

- Australian Government. About the Ozempic (Semaglutide) shortage 2022-2024. Therapeutic Goods Administration, 29 August 2024. Available from https://www.tga.gov.au/safety/shortages/information-about-major-medicine-shortages/about-ozempic-semaglutide-shortage-2022-2024.

- Talay, L., Vickers, M., Ruiz, L. Effectiveness of an email-based, Semaglutide-supported weight-loss service for people with overweight and obesity in Germany: A real-world retrospective cohort analysis. Obesities 2024;4:256-269.

- Novo Nordisk. Wegovy: Semaglutide Injection 2.4mg. Novo Nordisk Inc, 2024.Bagsvaerd, Denmark.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).