Submitted:

19 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

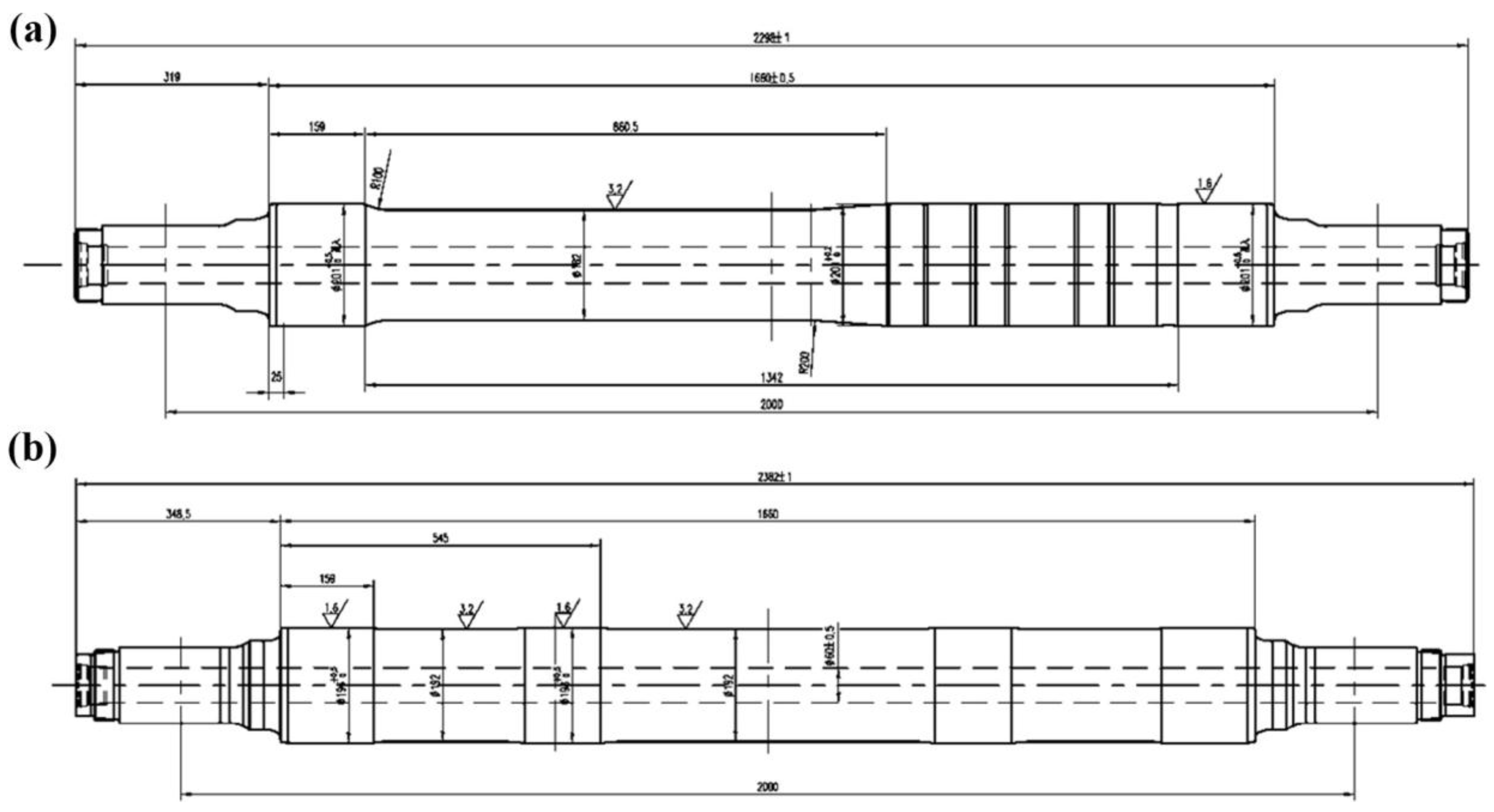

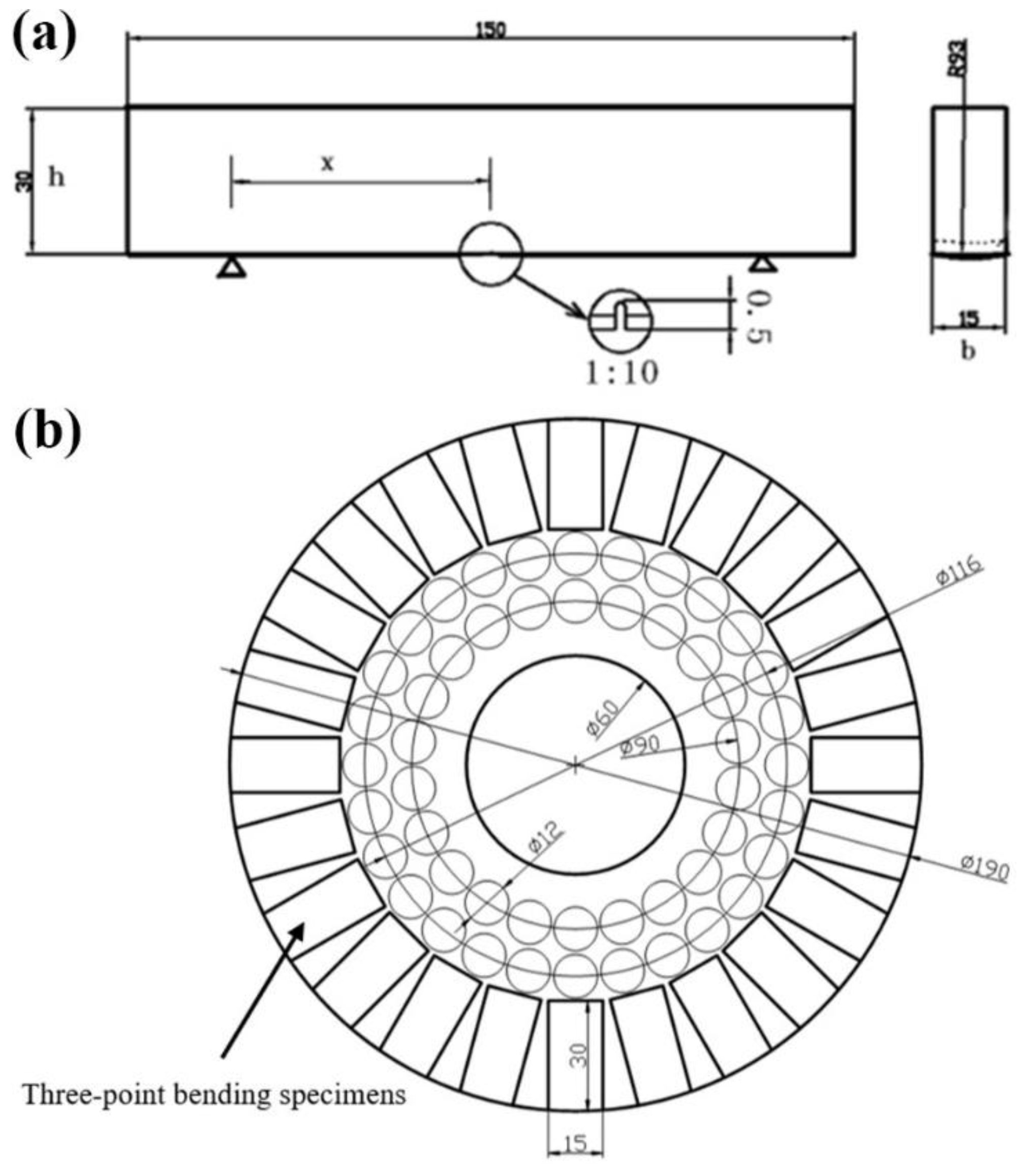

2.1. Specimen Design and Fabrication

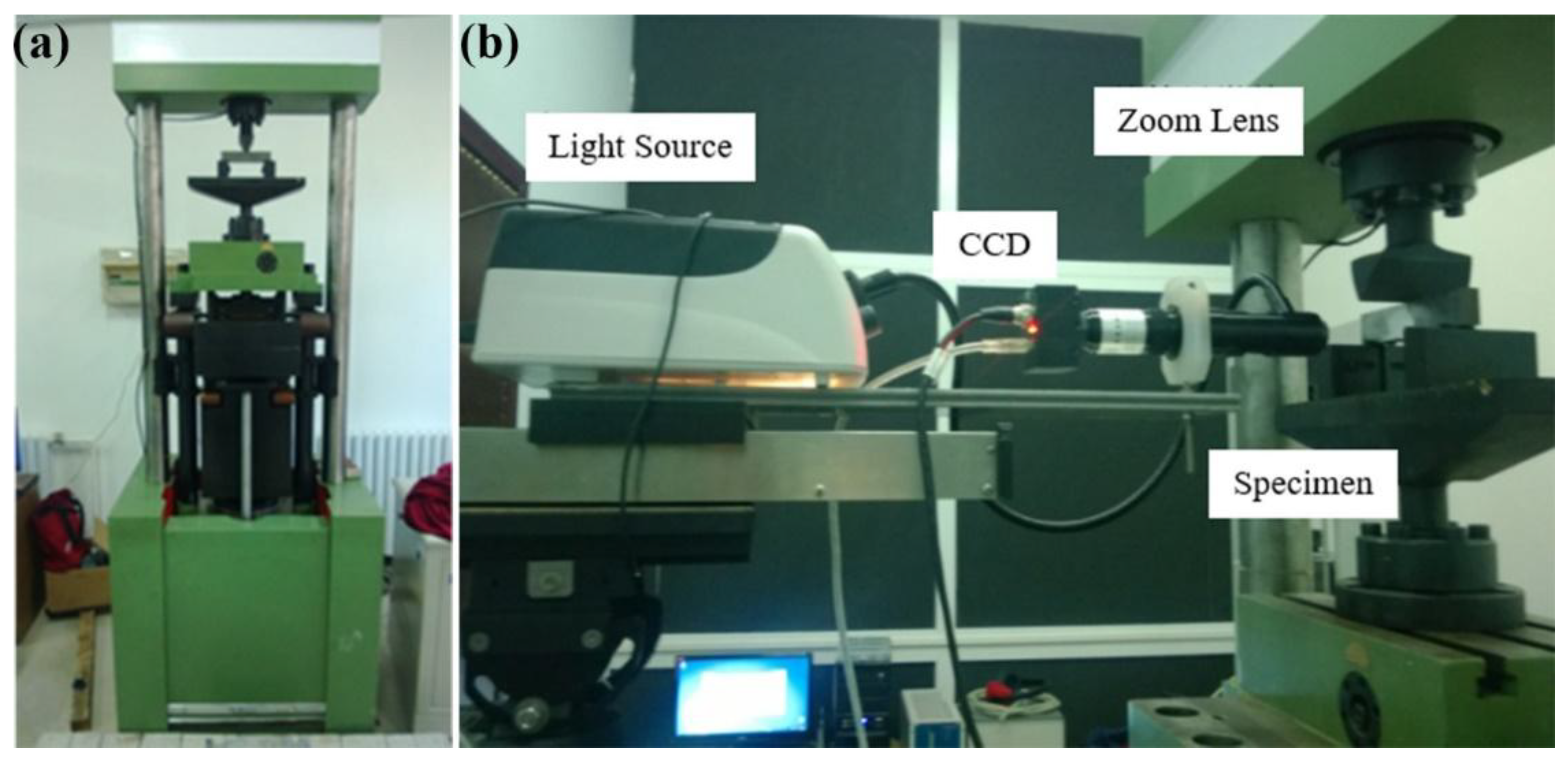

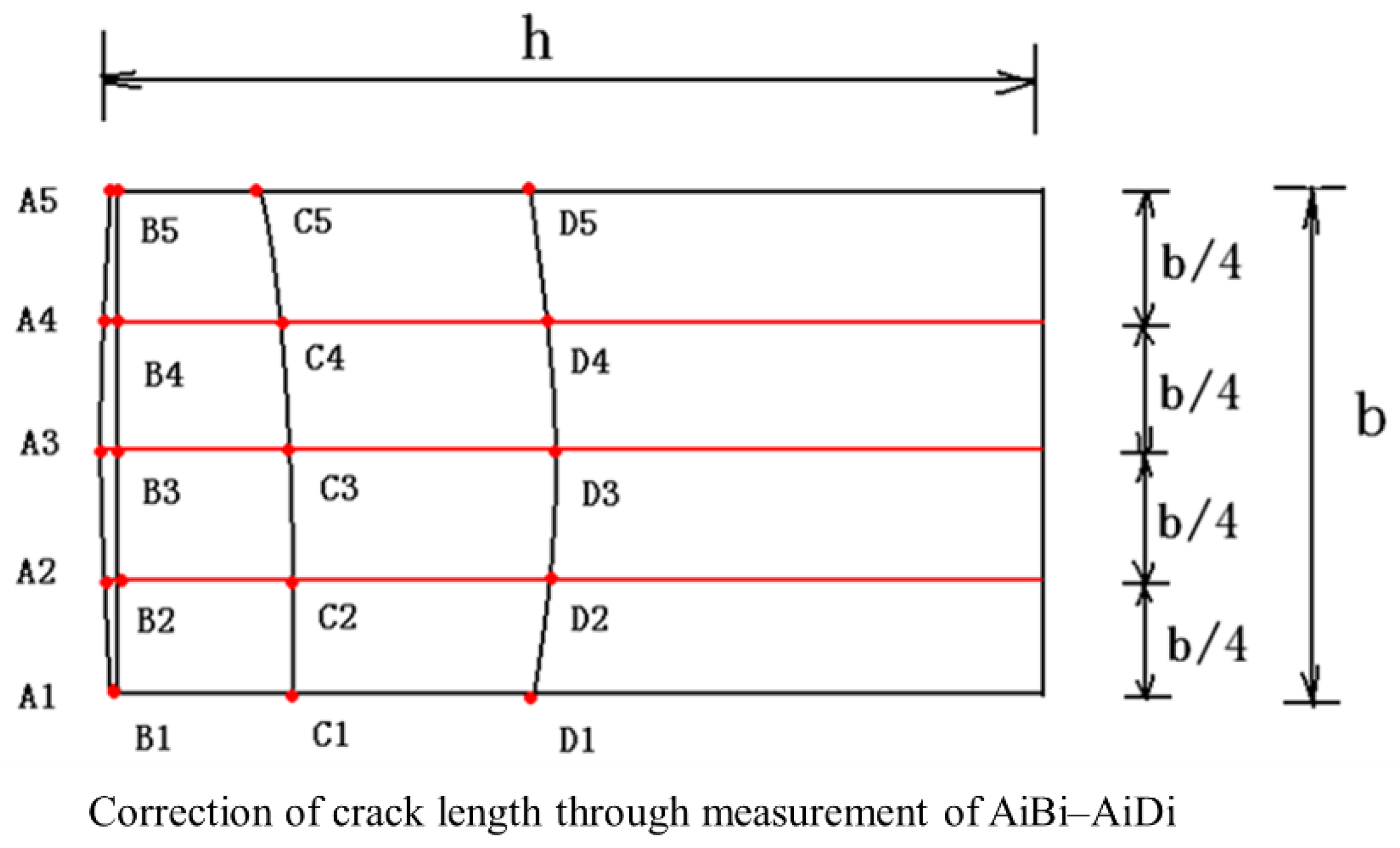

2.2. Testing Method and Devices

3. Results

3.1. a–N Data and Fractography

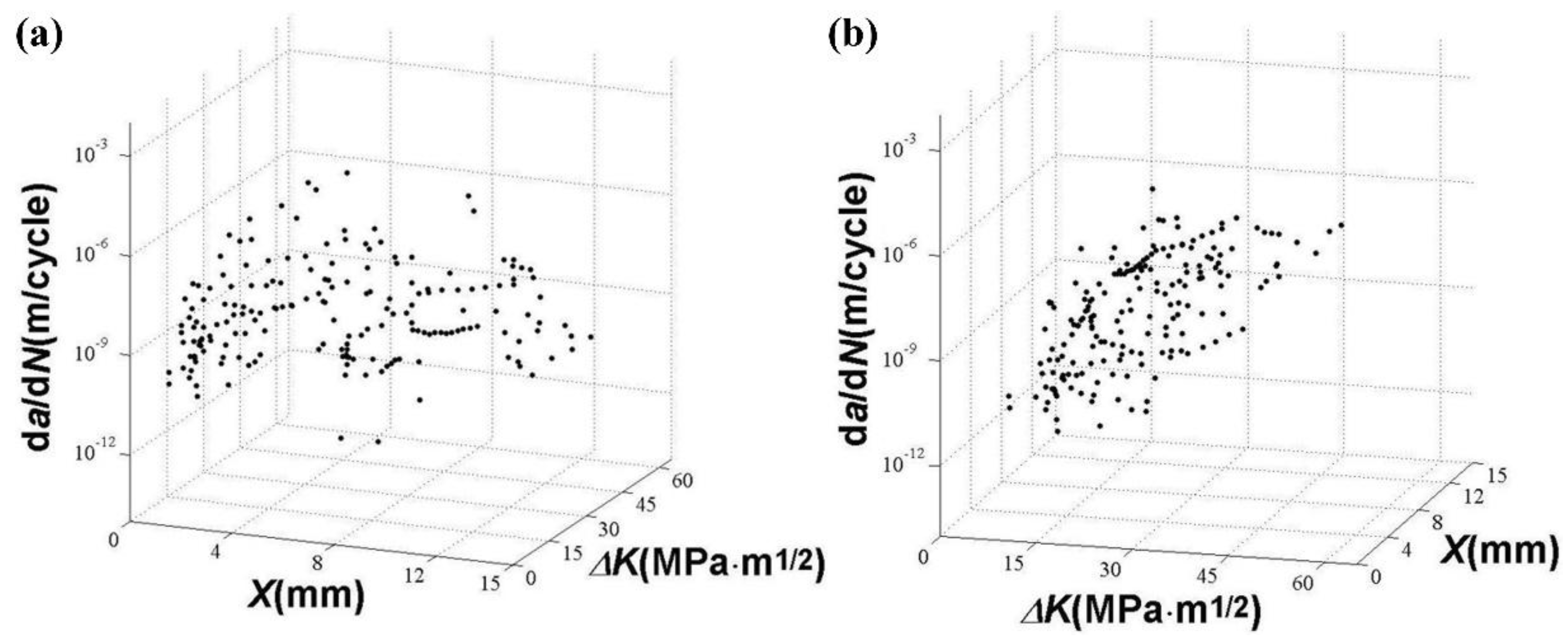

3.2. da/dN and ΔK Data

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary and Analysis of da/dN and ΔK Data

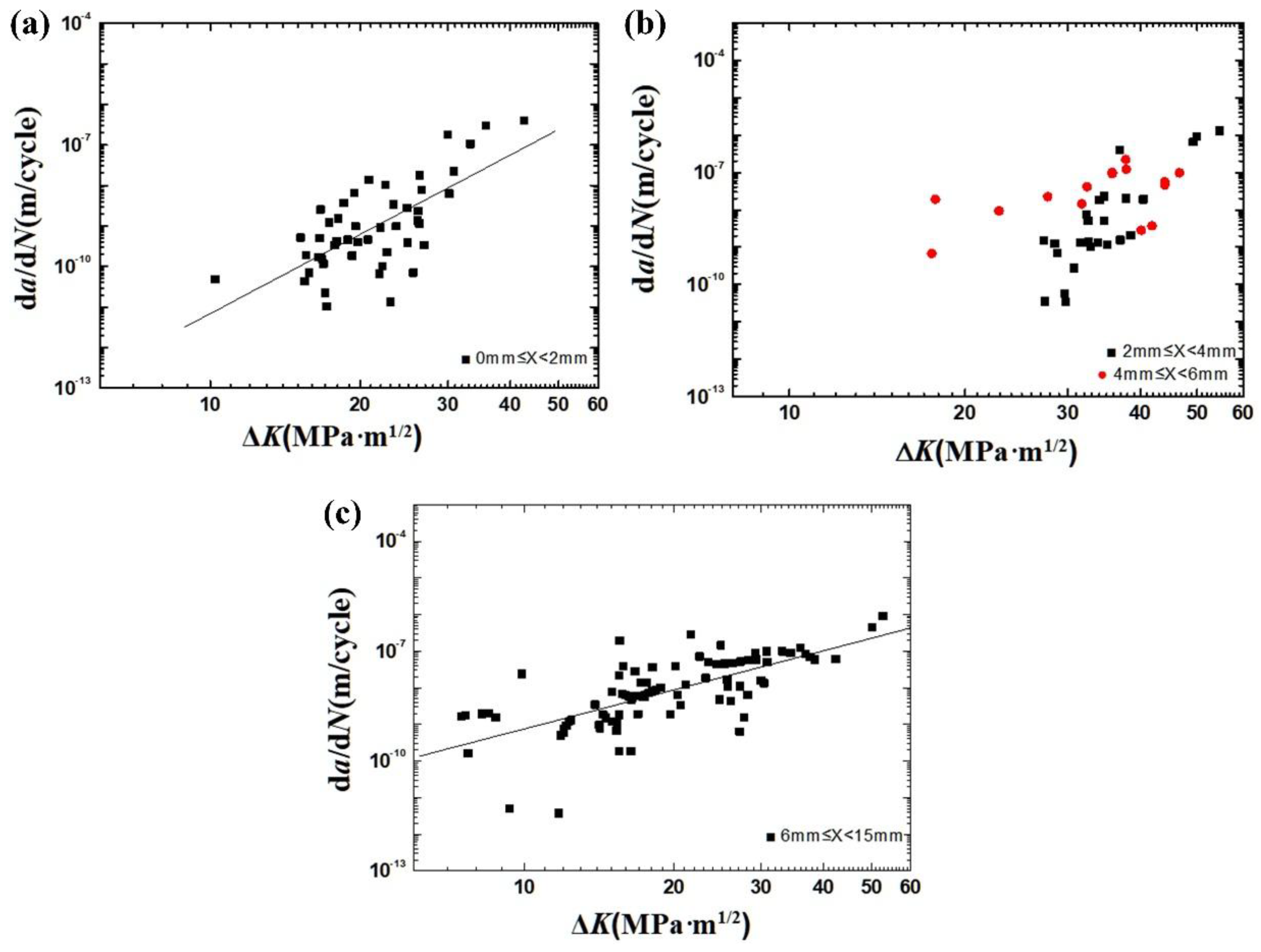

4.2. da/dN and ΔK in Multiple Depth Ranges

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Three-point bending specimens were extracted from the actual S38C axle, with the tensile side representing the hardened surface layer of the axle. Through three-point bending fatigue loading combined with crack length monitoring, the fatigue crack growth characteristics of the axle’s surface material, which features a gradient in hardness, were effectively captured. The experimental results reveal the relationship between the fatigue crack growth rate and the stress intensity factor range across three distinct microstructural regions of the axle material: the hardened surface layer (0–2 mm), the transition layer (2–6 mm), and the core matrix (beyond 6 mm). This stratification allows for a comprehensive understanding of how the material’s microstructural gradient influences fatigue crack propagation under cyclic loading conditions.

- (2)

- In the hardened surface layer of the axle, within the depth range of 0–2 mm from the surface, the relationship between da/dN and ΔK is represented by the following expression:where da/dN is in unit of m/cycle, and ΔK is in unit of MPa⋅m1/2.

- (3)

- In the core matrix of the axle, specifically within the depth range of 6–15 mm from the surface, the relationship between da/dN and ΔK is represented by the following expression:where da/dN is in unit of m/cycle, and ΔK is in unit of MPa⋅m1/2.

- (4)

- The comprehensive comparison indicates that the hardened surface layer of the axle exhibits significantly higher resistance to fatigue crack growth compared to both the transition layer and the core matrix.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Glossary: High-speed rail. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:High-speed_rail (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- High-speed rail. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High-speed_rail (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Ollivier, G.; Bullock, R.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, N. High-Speed Railways in China: A Look at Traffic; World bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zerbst, U.; Klinger, C.; Klingbeil, D. Structural assessment of railway axles—A critical review. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2013, 35, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.Y.; Liu, G.X.; Yousefian, K.; Jing, G.Q. Track Vertical Stiffness -Value, Measurement Methods, Effective Parameters and Challenges: A review. Transp. Geotech. 2022, 37, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Su, H.; Sun, C.; Hong, Y. The behavior of crack initiation and early growth in high-cycle and very-high-cycle fatigue regimes for a titanium alloy. Int. J. Fatigue 2018, 115, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Song, Q.; Zhou, L.; Pan, X. Characteristic of interior crack initiation and early growth for high cycle and very high cycle fatigue of a martensitic stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 758, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Hong, Y. High-cycle and very-high-cycle fatigue behaviour of a titanium alloy with equiaxed microstructure under different mean stresses. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2019, 42, 1950–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Pan, X.; Hong, Y. Further investigation on microstructure refinement of internal crack initiation region in VHCF regime of high-strength steels. Frattura ed Integrità Strutturale 2019, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Xu, S.; Qian, G.; Nikitin, A.; Shanyavskiy, A.; Palin-Luc, T.; Hong, Y. The mechanism of internal fatigue-crack initiation and early growth in a titanium alloy with lamellar and equiaxed microstructure. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 798, 140110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Pan, X.; Zheng, L.; Hong, Y. Microstructure refinement and grain size distribution in crack initiation region of very-high-cycle fatigue regime for high-strength alloys. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 134, 105473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, T.; Qian, G.; Zhang, G.; Wu, S.; Pan, X.; Du, L.; Liu, X. Effects of inclusion size and stress ratio on the very-high-cycle fatigue behavior of pearlitic steel. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 142, 105958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Su, H.; Liu, X.; Hong, Y. Multi-scale fatigue failure features of titanium alloys with equiaxed or bimodal microstructures from low-cycle to very-high-cycle loading numbers. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 890, 145906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Xu, S.; Nikitin, A.; Shanyavskiy, A.; Palin-Luc, T.; Hong, Y. Crack initiation induced nanograins and facets of a titanium alloy with lamellar and equiaxed microstructure in very-high-cycle fatigue. Mater. Lett. 2024, 357, 135769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, V.; Lal, D.N. Threshold condition for fatigue crack-propagation. Metall. Trans. 1974, 5, 1946–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schijve, J. Fatigue of Structures and Materials, 2nd ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, N.E. Mechanical Behavior of Materials: Engineering Methods for Deformation, Fracture, and Fatigue, 4th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Dai, Y.; Liu, Y. Crack propagation simulation and overload fatigue life prediction via enhanced physics-informed neural networks. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 186, 108382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Dai, Y.; Liu, Y. Structural fatigue crack propagation simulation and life prediction based on improved XFEM-VCCT. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 310, 110519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, A.H.I.; Sajith, S.; Shitole, S.; Almomani, A.; Khan, S.H.; Elsheikh, A.; Alzo’ubi, A.K. Fatigue life and crack growth prediction of metallic structures: A review. Structures 2025, 76, 109031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangid, M.D. The physics of fatigue crack propagation. Int. J. Fatigue 2025, 197, 108928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, M.A.; Mishra, A.; Benson, D.J. Mechanical properties of nanocrystalline materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2006, 51, 427–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xie, J.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Sun, C.; Hong, Y. Fatigue crack growth behavior in gradient microstructure of hardened surface layer for an axle steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 700, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.B.; Wang, Z.B.; Xu, J.L.; Lu, K. Simultaneous enhancement of stress- and strain-controlled fatigue properties in 316L stainless steel with gradient nanostructure. Acta Mater. 2019, 168, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Qian, G.; Wu, S.; Fu, Y.; Hong, Y. Internal crack characteristics in very-high-cycle fatigue of a gradient structured titanium alloy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnham, J.E.; Davis, C.L. The role of deformed rail microstructure on rolling contact fatigue initiation. Wear 2008, 265, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, C.; Bettge, D. Axle fracture of an ICE3 high speed train. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2013, 35, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.K.; Ding, H.H.; Wang, W.J.; Liu, Q.Y.; Guo, J.; Zhu, M.H. Investigation on microstructure and wear characteristic of laser cladding Fe-based alloy on wheel/rail materials. Wear 2015, 330, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani-Gangaraj, S.M.; Carboni, M.; Guagliano, M. Finite element approach toward an advanced understanding of deep rolling induced residual stresses, and an application to railway axles. Mater. Design 2015, 83, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Ding, H.H.; Lewis, R.; Liu, Q.Y.; Guo, J.; Wang, W.J. Microstructure evolution of railway pearlitic wheel steels under rolling-sliding contact loading. Tribol. Int. 2021, 154, 106685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, O.; Maleki, E.; Karademir, I.; Husem, F.; Efe, Y.; Das, T. Effects of conventional shot peening, severe shot peening, re-shot peening and precised grinding operations on fatigue performance of AISI 1050 railway axle steel. Int. J. Fatigue 2022, 155, 106613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Wang, K.; Hu, F. Overview and prospect of axle technology for high speed trains at home and abroad. Mater. China 2019, 38, 641–650. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Ma, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, S. The fatigue behaviors of a medium-carbon pearlitic wheel-steel with elongated sulfides in high-cycle and very-high-cycle regimes. Materials 2021, 14, 4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenam, D.E.P.; Chown, L.H.; Papo, M.J.; Cornish, L.A. Steels for rail axles-an overview. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2024, 49, 163–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zheng, C.; Lv, B.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, F. Research progress on rolling contact fatigue damage of bainitic rail steel. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 143, 106875. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R.; Olofsson, U. Mapping rail wear regimes and transitions. Wear 2004, 257, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enblom, R.; Berg, M. Simulation of railway wheel profile development due to wear—Influence of disc braking and contact environment. Wear 2005, 258, 1055–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braghin, F.; Lewis, R.; Dwyer-Joyce, R.S.; Bruni, S. A mathematical model to predict railway wheel profile evolution due to wear. Wear 2006, 261, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, K.; Toyama, K.; Kubota, M. The analysis and prevention of failure in railway axles. Int. J. Fatigue 1998, 20, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekberg, A.; Kabo, E. Fatigue of railway wheels and rails under rolling contact and thermal loading—An overview. Wear 2005, 258, 1288–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbst, U.; Mädler, B.; Hintze, H. Fracture mechanics in railway applications: An overview. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2005, 72, 163–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbst, U.; Beretta, S.; Köhler, G.; Lawton, A.; Vormwald, M.; Beier, H.T.; Klinger, C.; Cerny, I.; Rudlin, J.; Heckel, T.; et al. Safe life and damage tolerance aspects of railway axles—A review. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2013, 98, 214–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekberg, A.; Åkesson, B.; Kabo, E. Wheel/rail rolling contact fatigue—Probe, predict, prevent. Wear 2014, 314, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Y. Metal Fatigue: Effect of Small Defects and Nonmetallic Inclusions; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Du, L.; Qian, G.; Hong, Y. Microstructure features induced by fatigue crack initiation up to very-high-cycle regime for an additively manufactured aluminium alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 173, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Hong, Y. High-cycle and very-high-cycle fatigue of an additively manufactured aluminium alloy under axial cycling at ultrasonic and conventional frequencies. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 185, 108363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Pan, X.; Hong, Y. New insights into microstructure refinement in crack initiation region of very-high-cycle fatigue for SLM Ti-6Al-4V via precession electron diffraction. Materialia 2024, 33, 102008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Qian, G.; Hong, Y. Nanograin formation in dimple ridges due to local severe-plastic-deformation during ductile fracture. Scr. Mater. 2021, 194, 11363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Pan, X.; Qian, G.; Zheng, L.; Hong, Y. Crack initiation mechanisms under two stress ratios up to very-high-cycle fatigue regime for a selective laser melted Ti-6Al-4V. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 149, 106294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C.Y.; Chua, C.K.; Dong, Z.L.; Liu, Z.H.; Zhang, D.Q.; Loh, L.E.; Sing, S.L. Review of selective laser melting: Materials and applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2015, 2, 041101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DebRoy, T.; Wei, H.L.; Zuback, J.S.; Mukherjee, T.; Elmer, J.W.; Milewski, J.O.; Beese, A.M.; Wilson-Heid, A.; De, A.; Zhang, W. Additive manufacturing of metallic components—Process, structure and properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 92, 112–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Jian, Z.; Pan, X.; Berto, F. In-situ investigation on fatigue behaviors of Ti-6Al-4V manufactured by selective laser melting. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 133, 105424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Jian, Z.; Qian, Y.; Pan, X.; Ma, X.; Hong, Y. Very-high-cycle fatigue behavior of AlSi10Mg manufactured by selective laser melting: Effect of build orientation and mean stress. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 138, 105696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badoniya, P.; Srivastava, M.; Jain, P.K.; Rathee, S. A state-of-the-art review on metal additive manufacturing: Milestones, trends, challenges and perspectives. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. 2024, 46, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Pan, X.; Su, T.; Long, X.; Liu, B.; Tang, Q.; Ren, X.; Sun, C.; Qian, G.; et al. A new probabilistic control volume scheme to interpret specimen size effect on fatigue life of additively manufactured titanium alloys. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 183, 108262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Pan, S.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; He, X.; Pan, X. Anisotropic tensile behavior and fracture characteristics of an additively manufactured nickel alloy without and with a heat treatment of solution aging. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 927, 148015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Kok, Y.; Tan, Y.J.; Descoins, M.; Mangelinck, D.; Tor, S.B.; Leong, K.F.; Chua, C.K. Graded microstructure and mechanical properties of additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V via electron beam melting. Acta Mater. 2015, 97, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Jia, Q.; Li, J.; Chong, K.; Du, L.; Pan, X.; Chang, C. Mechanical properties and parameter optimization of TC4 alloy by additive manufacturing. China Surf. Eng. 2022, 35, 215–223. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Fu, R.; Du, L.; Pan, X. Research viewpoint on performance enhancement for very-high-cycle fatigue of Ti-6Al-4V alloys via laser-based powder bed fusion. Crystals 2024, 14, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Lui, E.W.; Pateras, A.; Qian, M.; Brandt, M. In situ tailoring microstructure in additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V for superior mechanical performance. Acta Mater. 2017, 125, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specimen Number | Width (mm) | Height (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15.60 | 30.90 |

| 3 | 16.00 | 31.00 |

| 4 | 16.00 | 30.70 |

| 8 | 15.98 | 31.20 |

| 17 | 15.88 | 30.80 |

| 21 | 15.70 | 31.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).