Submitted:

20 June 2025

Posted:

20 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. State-Space Explosion

2.2. Scalability in Distributed Systems

2.3. Limited Expressiveness for Nonlinear Constraints

2.4. Rigid Enforcement of the Controller

2.5. Partial Observability Challenges

2.6. Other Difficulties

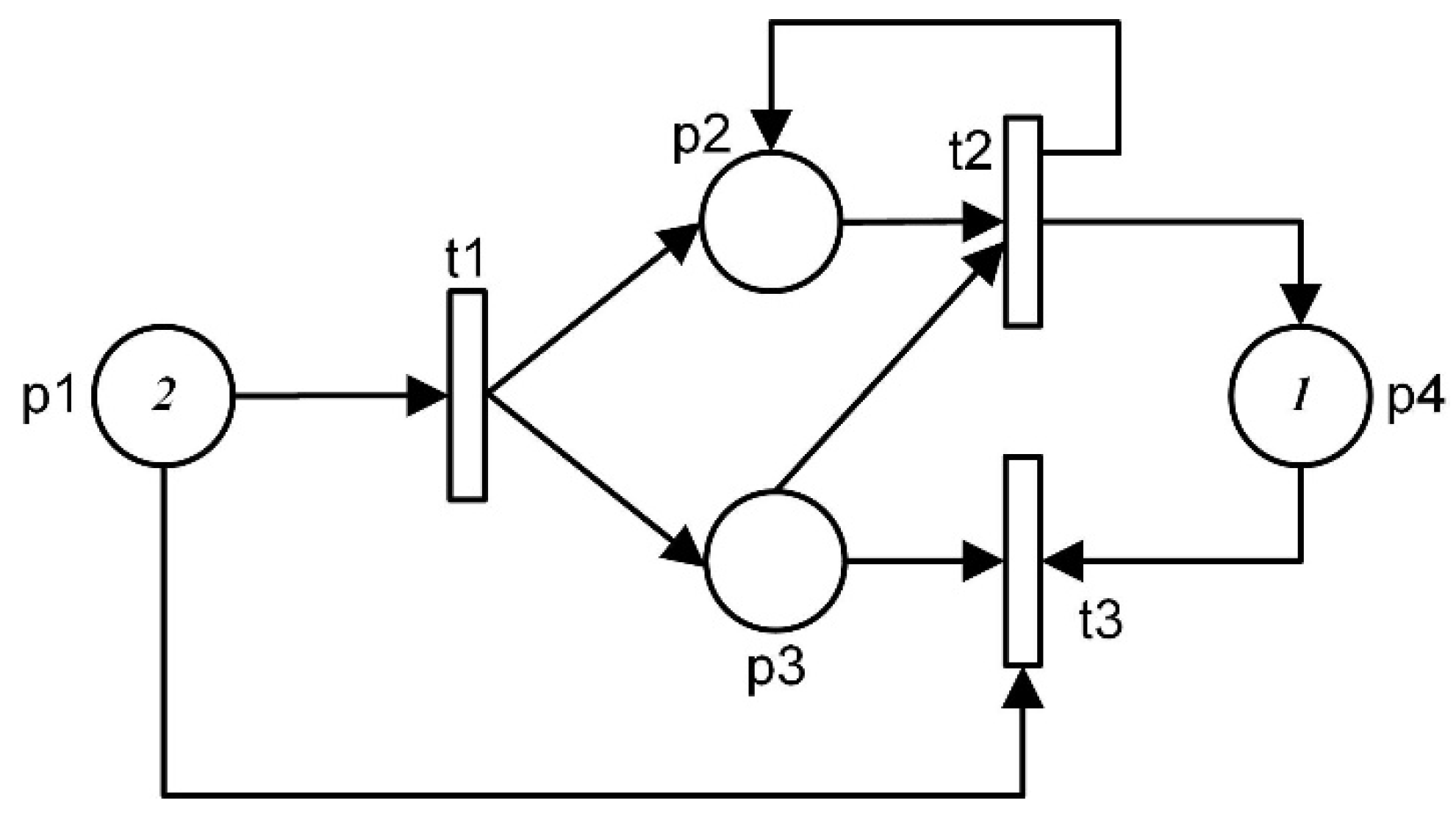

3. Petri Nets

3.1. Definition: P/T Petri Nets

- T is a finite set of transitions, T = {t1, t2, . . . , tnt }. P ∩ T = ∅.

- A is the set of arcs (from places to transitions and from transitions to places). A ⊆ (P × T) ∪ (T × P). The default arc weight W of aij (aij ∈ A, an arc going from pi to tj or from ti to pj) is one, unless noted otherwise.

- M is the row vector of markings (tokens) on the set of places. M = [M(p1), M(p2), . . . , M(pnp )] ∈ Nnp , M0 is the initial marking. Due to the markings, a PTN = (P, T, A, M) is also called a marked P/T Petri net. P/T Petri nets do not involve time. Hence, P/T Petri nets are insufficient to model engineering systems, as time is one of the key performance indicators (KPI). Hence, Timed Petri net is an extended Petri net incorporating time.

3.2. Definition: Timed Petri Net

- (P, T, A, M) is a Marked Petri net,

- FT is a mapping of T into R+: ∀t ∈ T, FT(t) ∈ R+, FT(t) > 0

- FT(t) is known as the firing times of the transitions and is defined to be greater than zero.

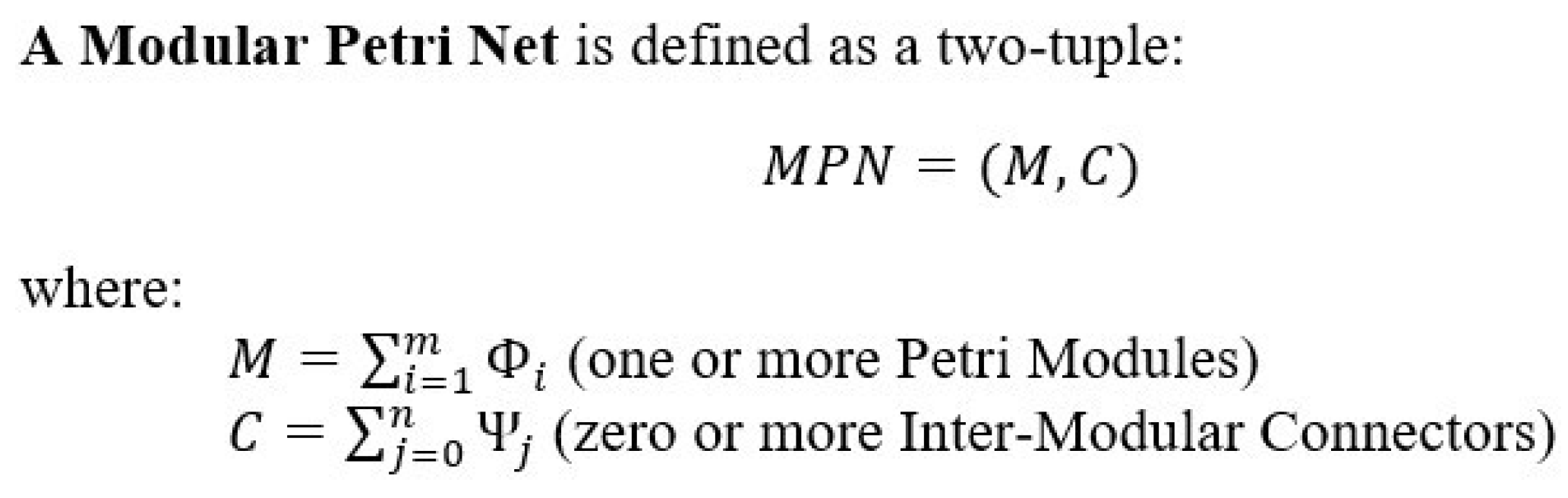

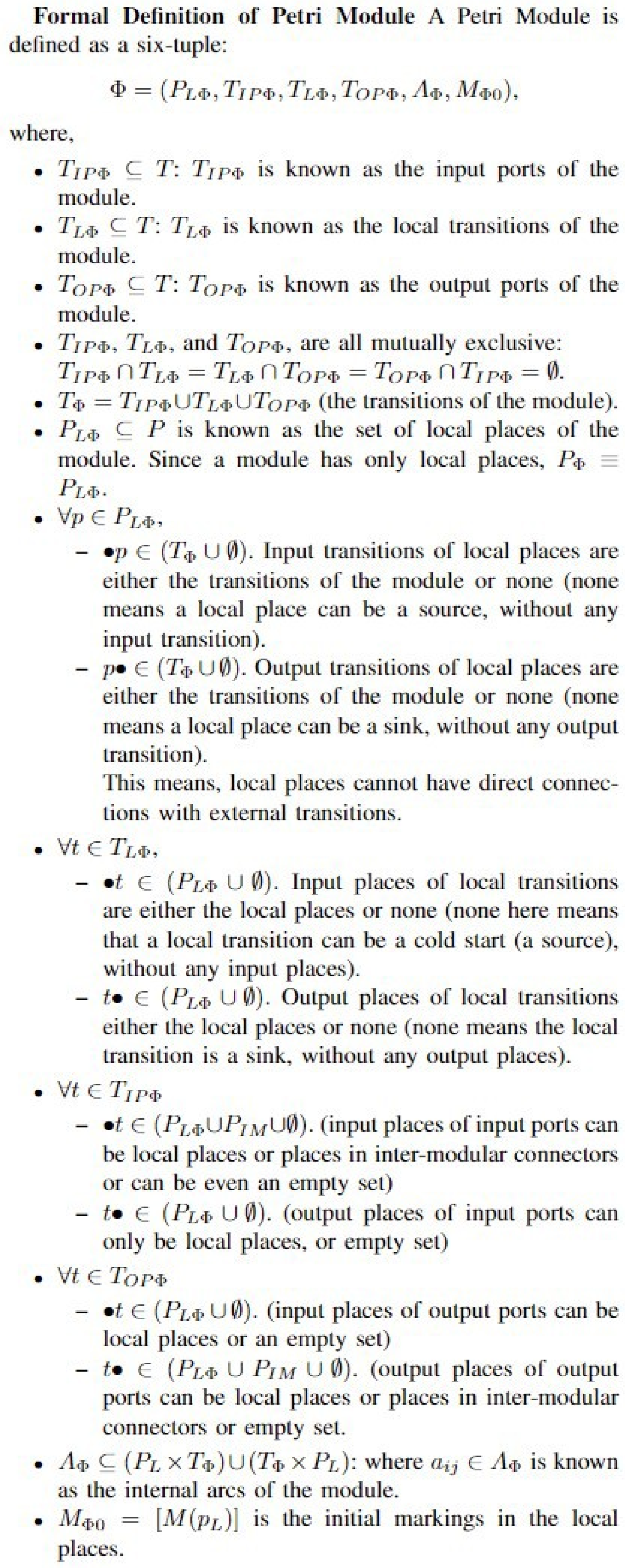

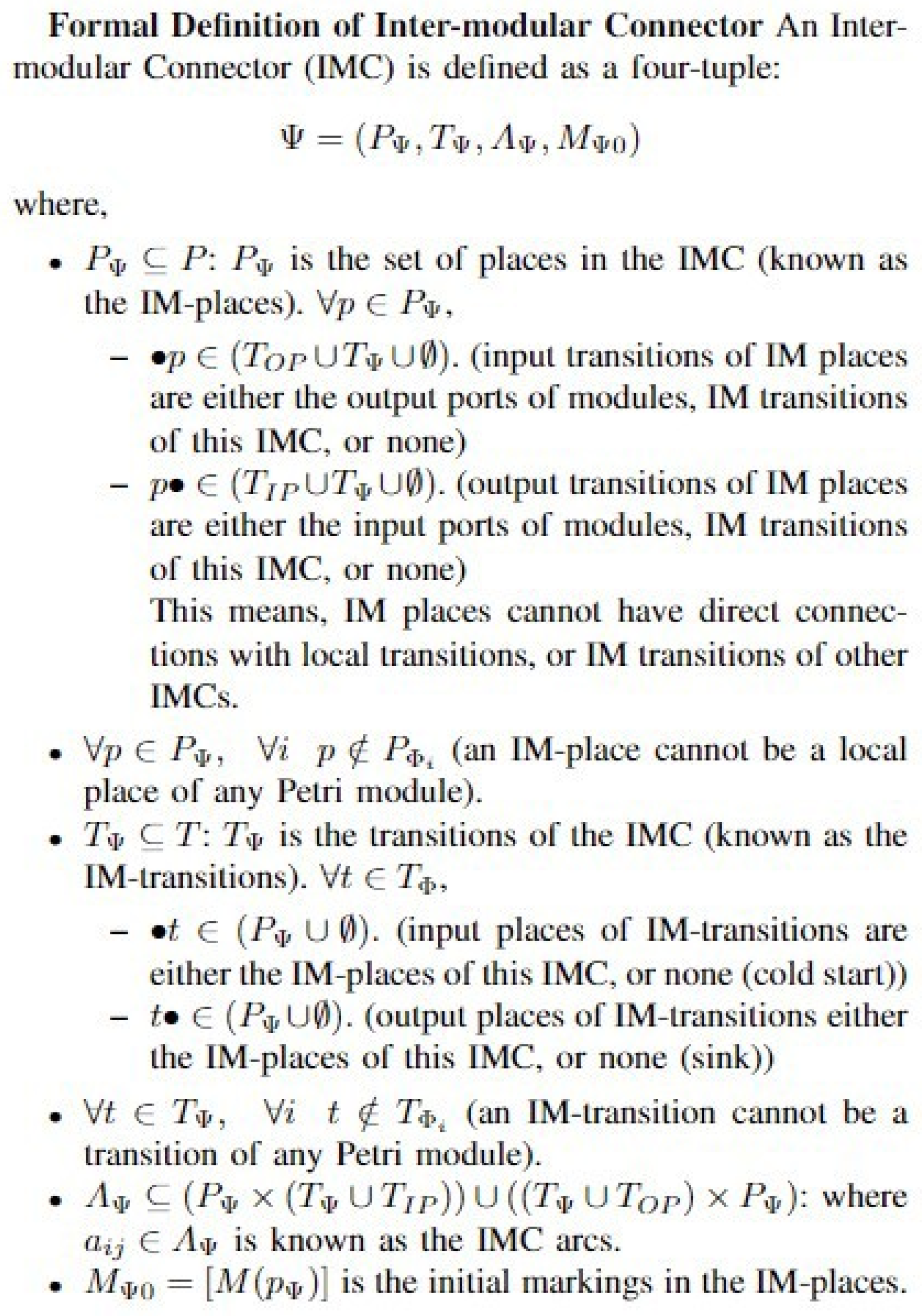

4. Modular Petri Nets

Modular Petri Net and Petri Modules

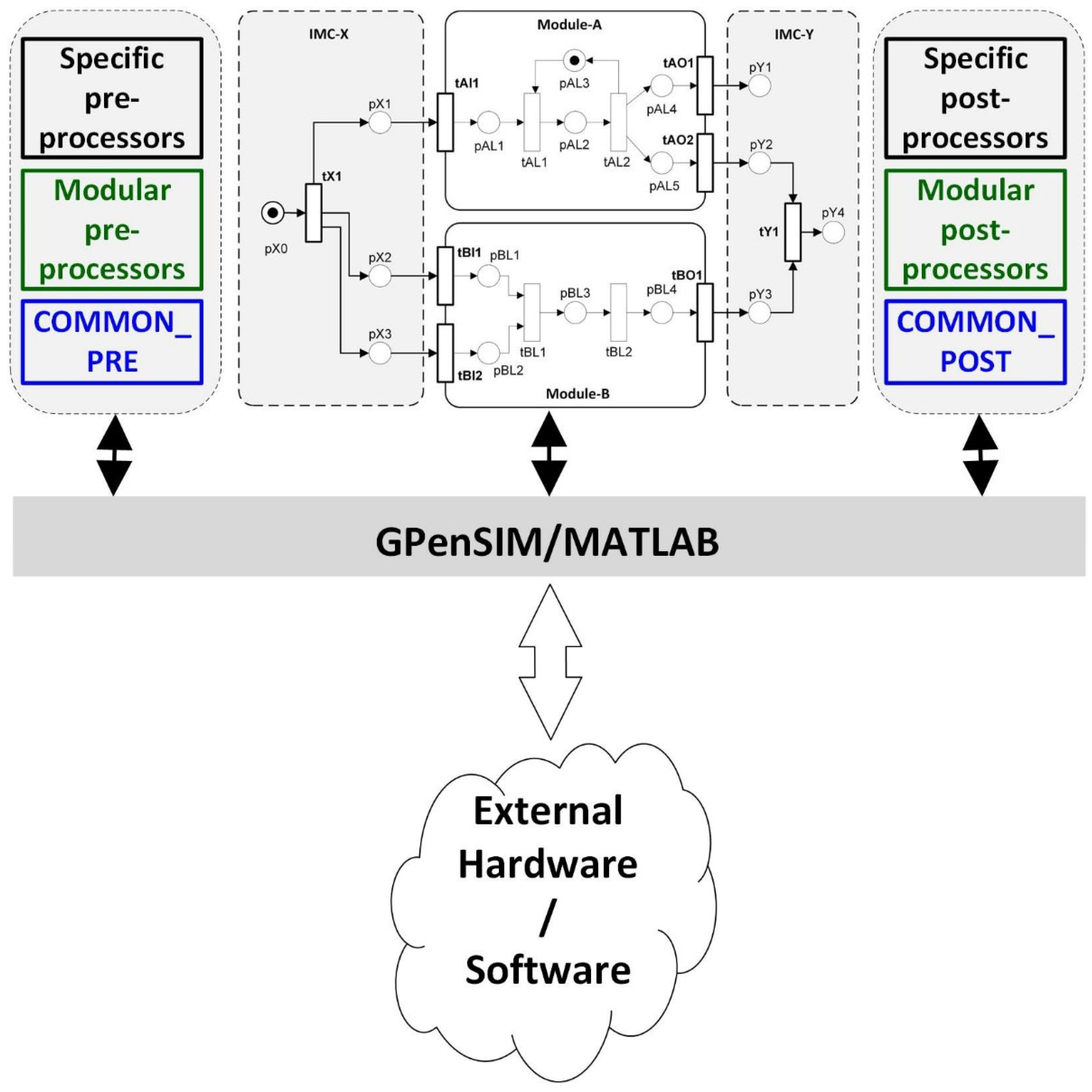

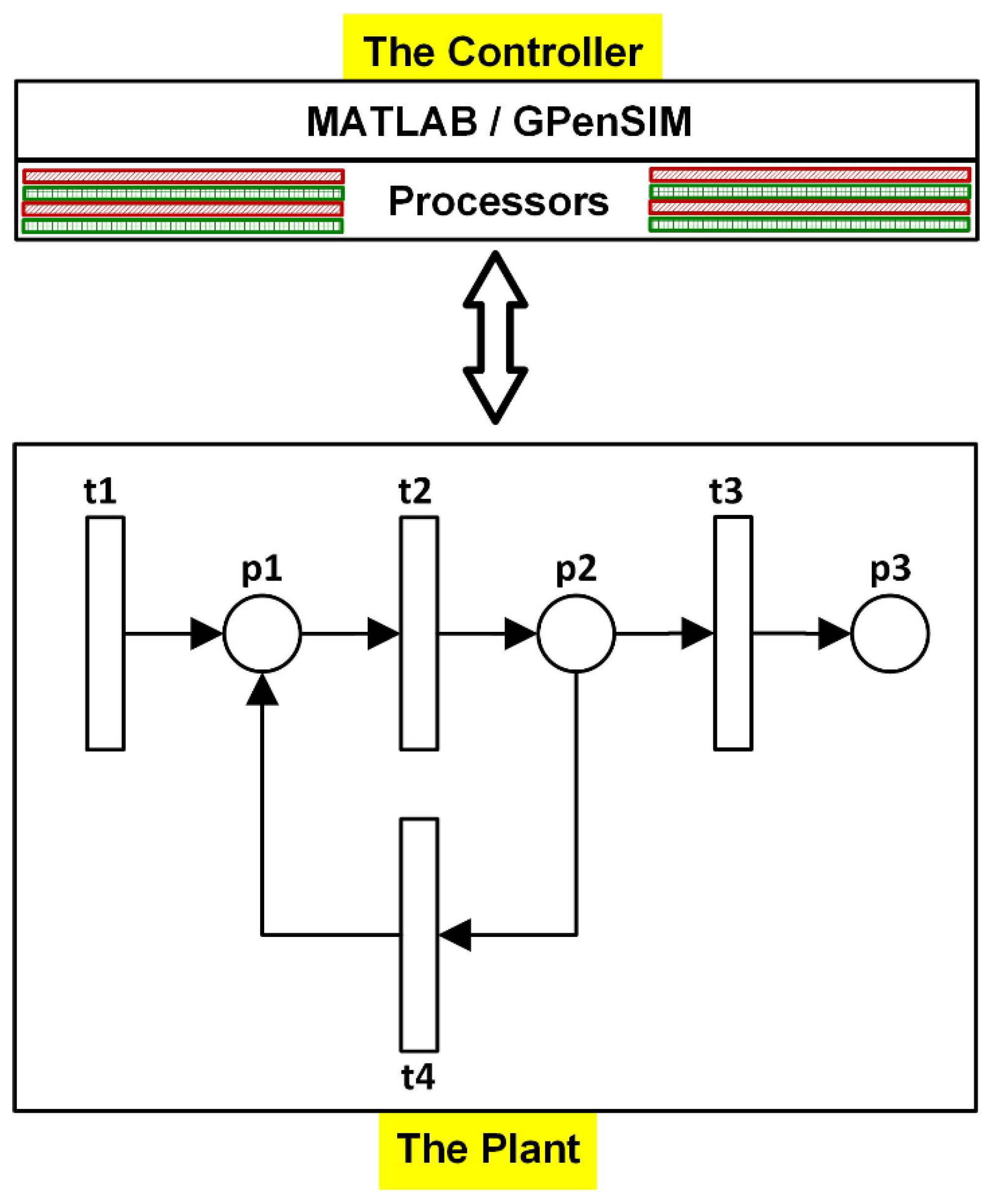

5. GPenSIM: A Modular Petri Net Framework for Scalable Supervisory Control

5.1. “The Theory of Connection” Based Design

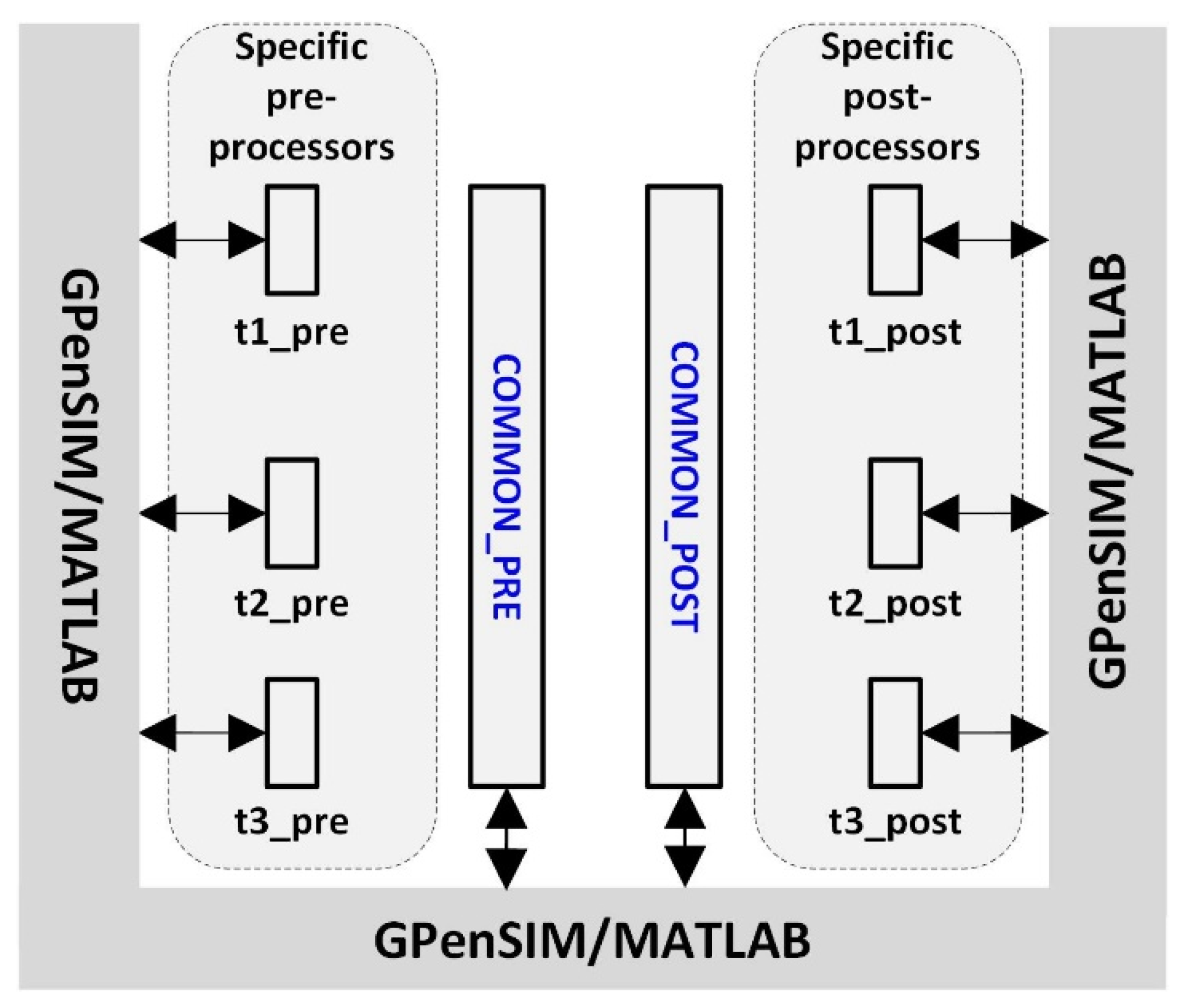

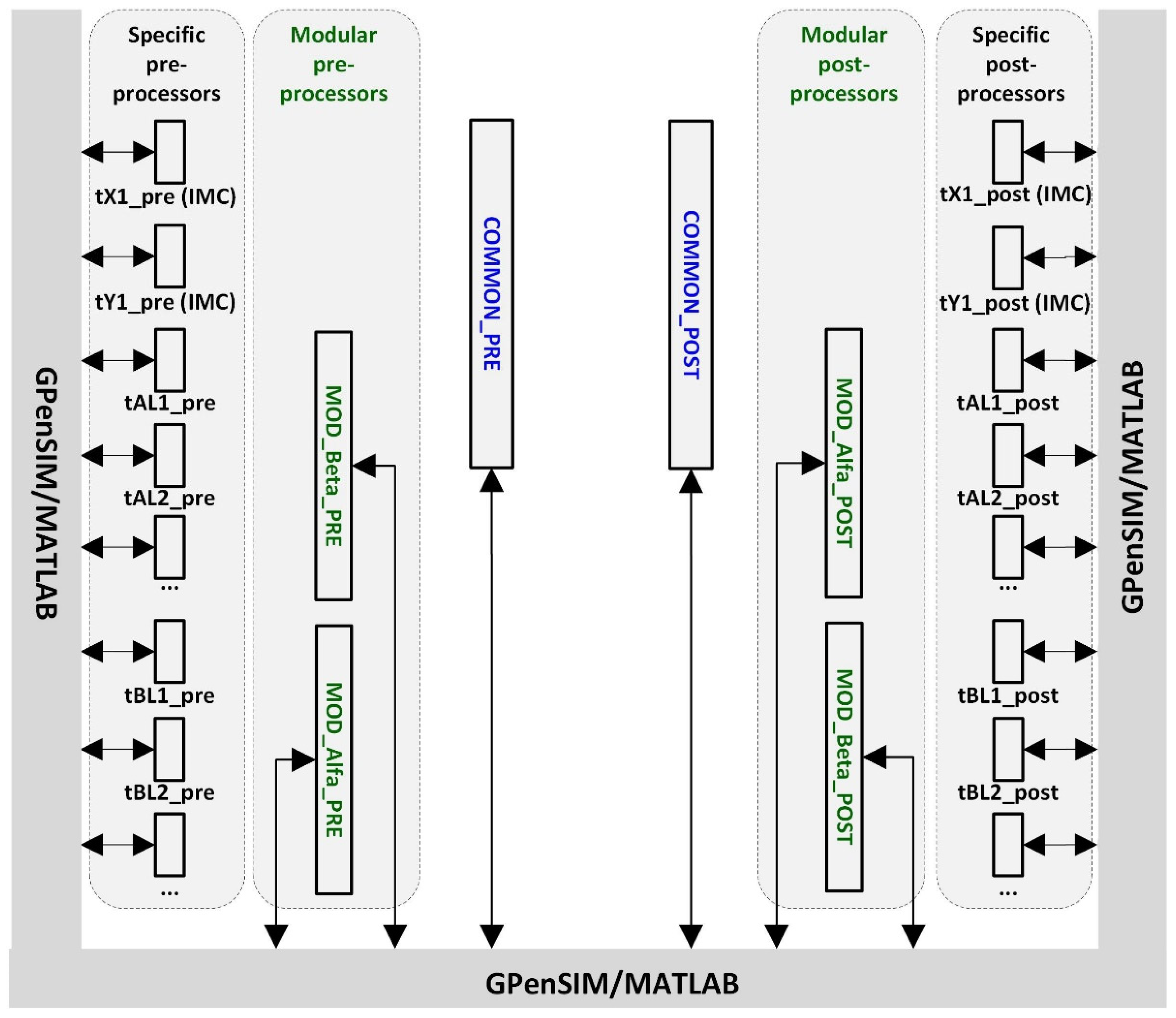

5.2. GPenSIM Processors

- Petri Net Definition File (PDF): This file defines the static Petri net graph (places, transitions, and the arcs). This file will be executed only once, for creating a MATLAB structure representing the topological information of this file.

- The Main Simulation File (MSF): This file declares the initial dynamics (e.g., initial tokens, firing times of transitions) and starts the simulations. Once the simulation is started, the GPenSIM compiler takes over to run the simulation. When the simulations are complete, control is passed back to this file so that the simulation results can be analyzed and plotted.

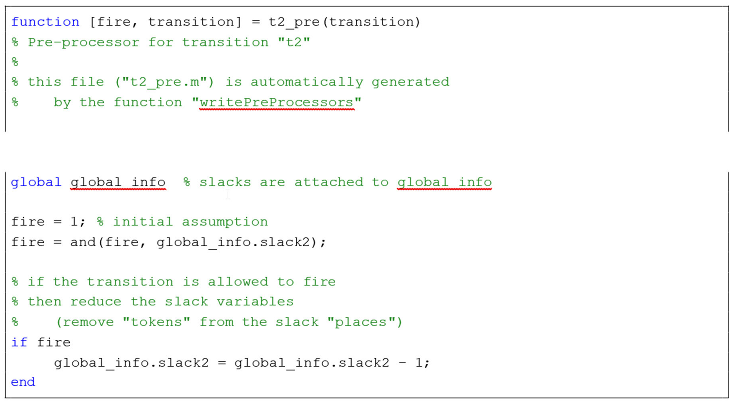

- Pre-processors: Whenever transitions are enabled, pre-processors are executed. Only if the corresponding pre-processors return logical one, the transition will be allowed to start firing.

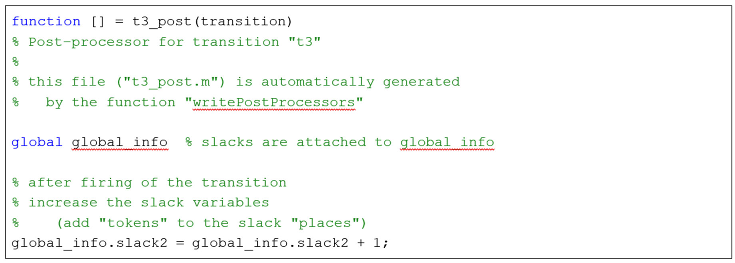

- Post-processors: Whenever transitions complete firing, post-processors are executed. This means that whenever a transition starts firing and completes firing, there will be a processor file executed by the compiler. Hence, it is the processor files (pre-processors and post-processors) that work as the interface, both intra-model (connecting the elements of the model) and between the model and the external world.

5.3. Integration with MATLAB and the External World

6. Discussion: Enhancing Supervisory Control with GPenSIM

- Network Structure: Modular design patterns (centralized vs. decentralized) deter- mine adaptability, aligning with supervisory control challenges in distributed systems (Section 2.2).

- Boundary Dynamics: GPenSIM’s interface - the processors (pre/post-processors) - mod- 234 els interactions between the Petri net and its environment, addressing partial observ- 235 ability (Section 2.5) and unmodeled disturbances (Section 2.6). In the following subsection, we shall see how GPenSIM can help solve some of the difficulties we face in supervisory control theory.

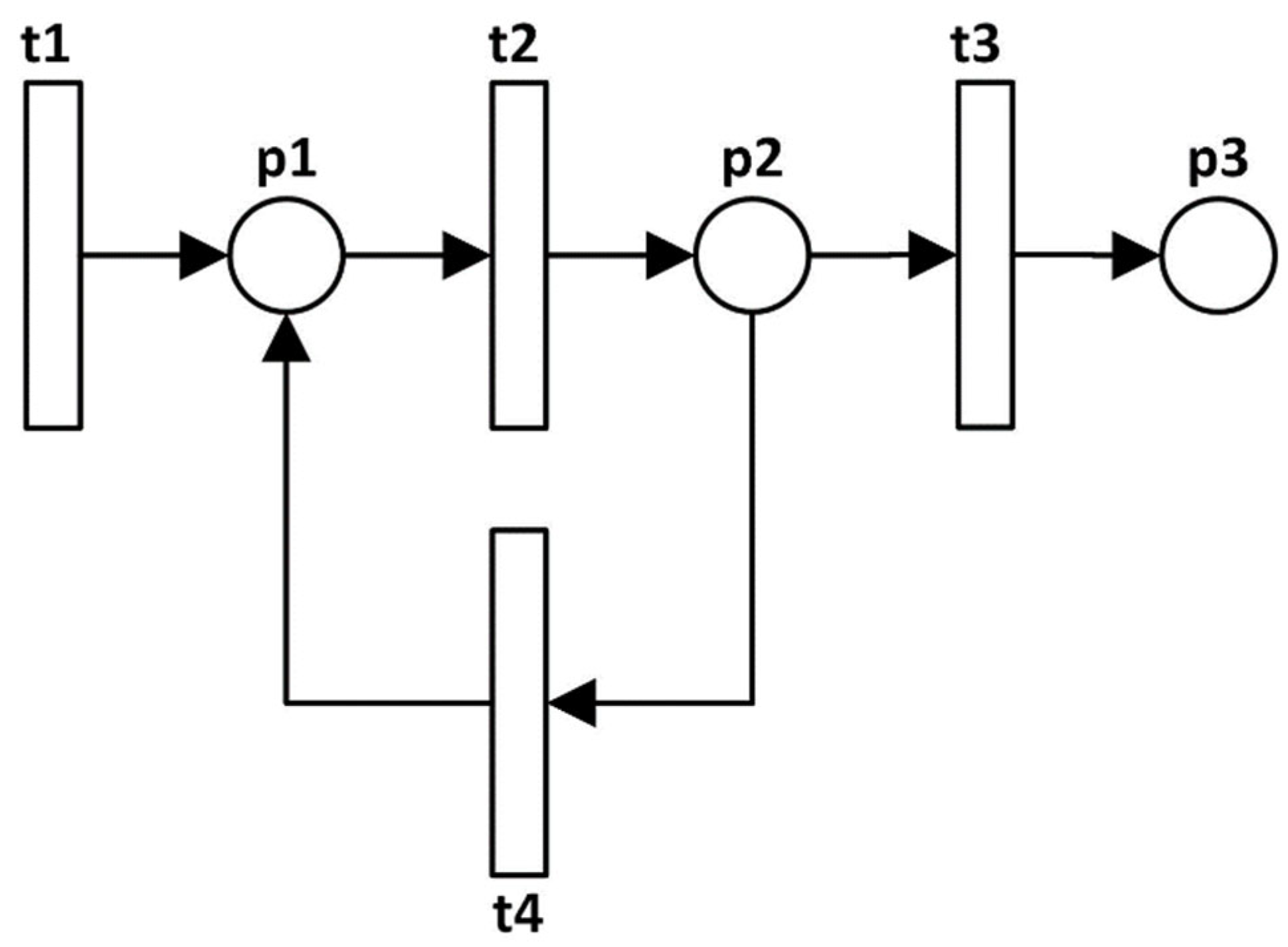

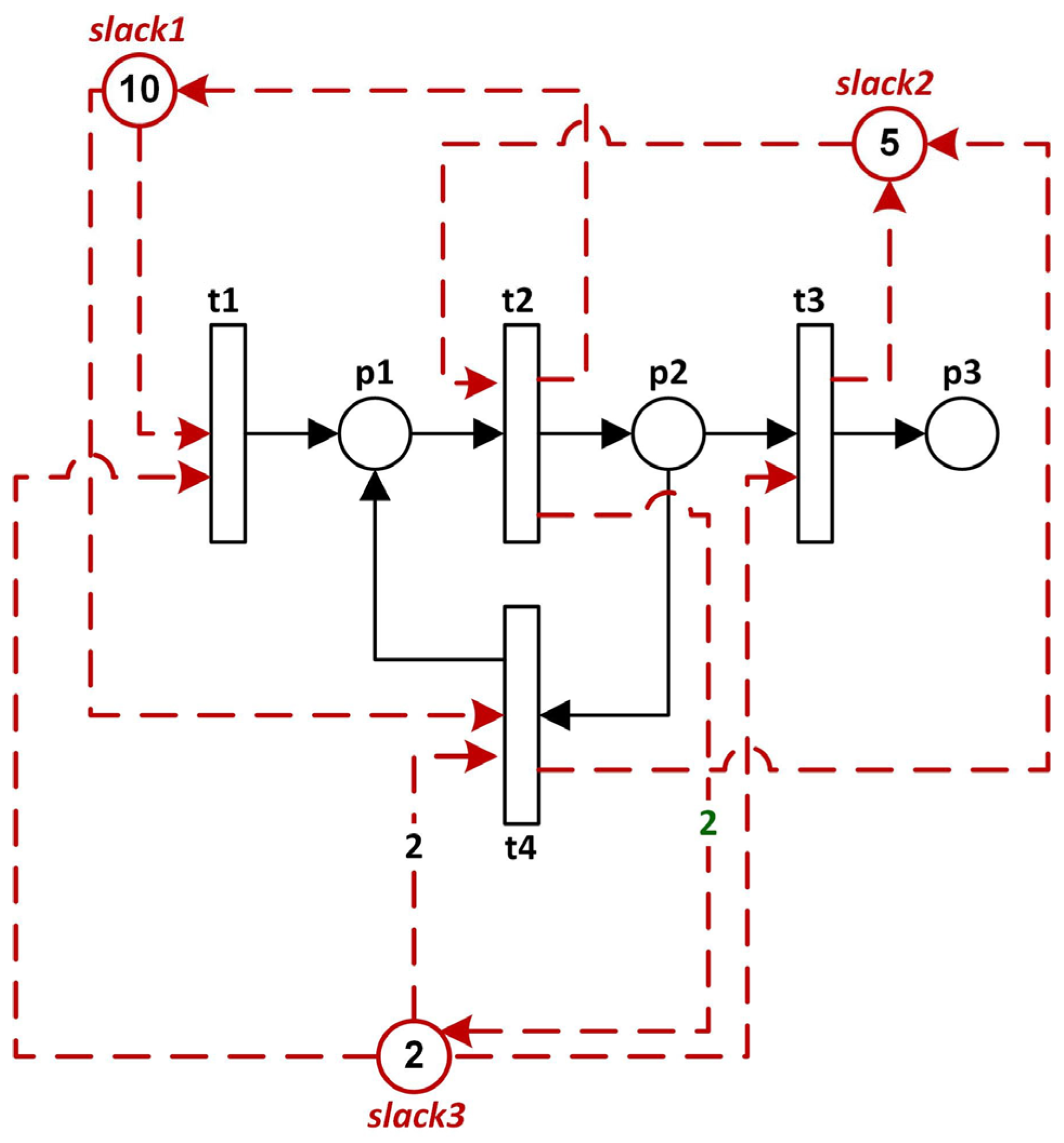

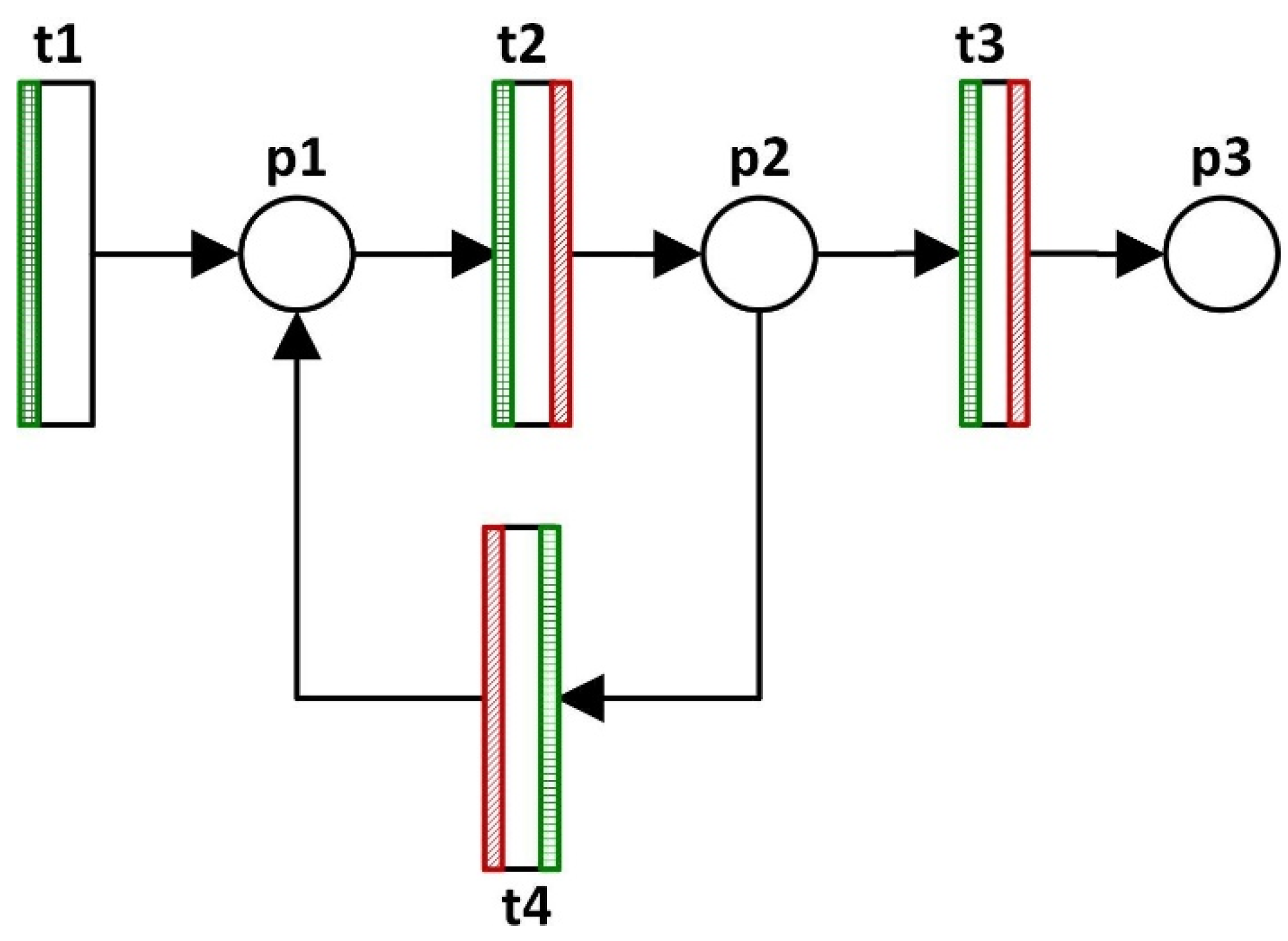

6.1. Reducing State-Space Explosion: Moving Control Logic from Controller to Processors

- The number of tokens in p1 must always be less than or equal to 10.

- The number of tokens in p2 must always be less than or equal to 5.

- The difference between the tokens in p1 and p2 must always be less than or equal to 2.

| Listing 1: Specific pre-processor "t2_pre". |

|

| Listing 2: Specific post-processor "t3_post". |

|

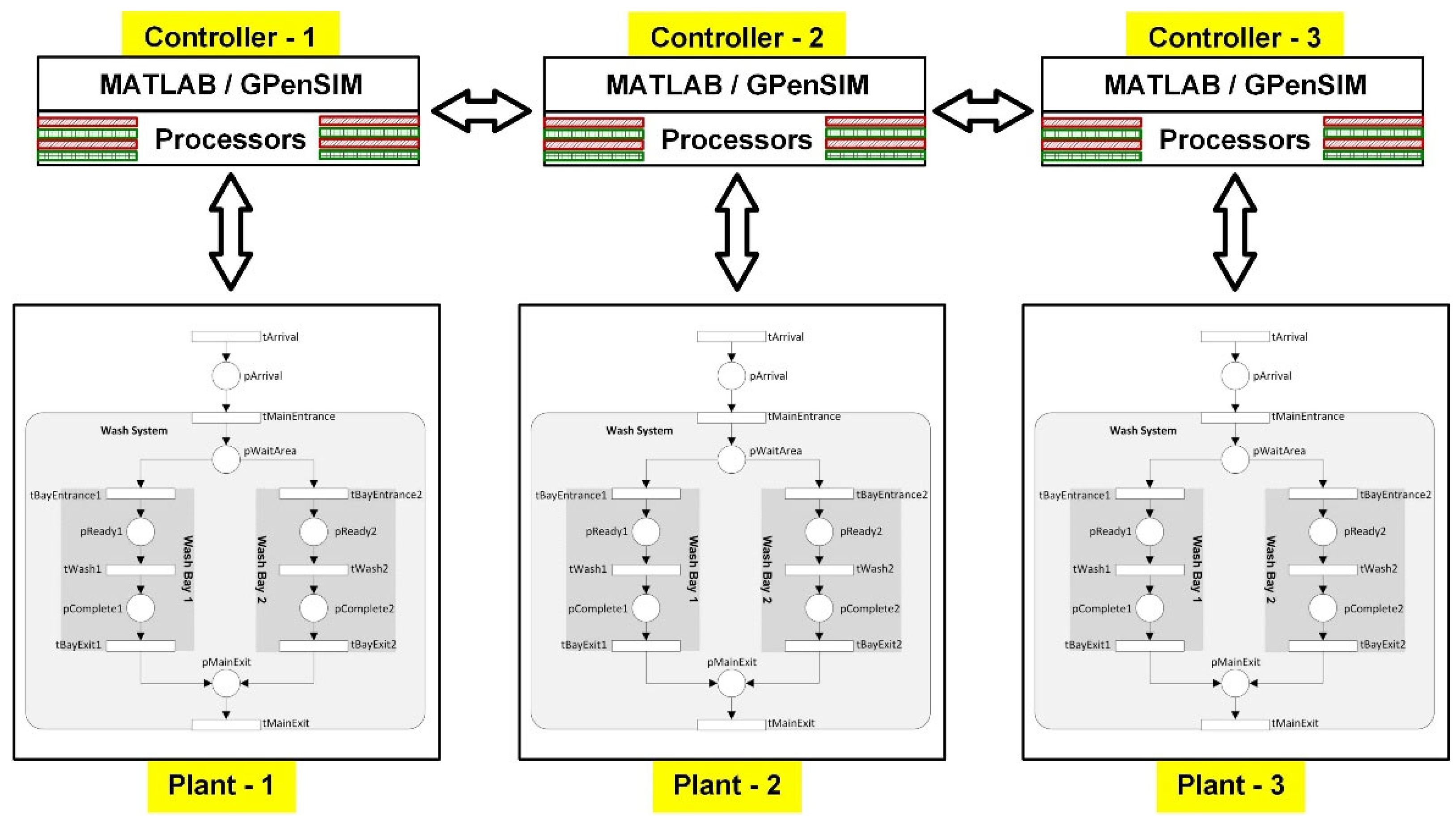

6.2. Increasing Scalability in Distributed Systems

- Hierarchical Abstraction: Modules can operate at varying granularity levels, trading off detail for scalability—a key consideration in industrial automation [15].

6.3. Enhanced Expressiveness via Programmable Interfaces

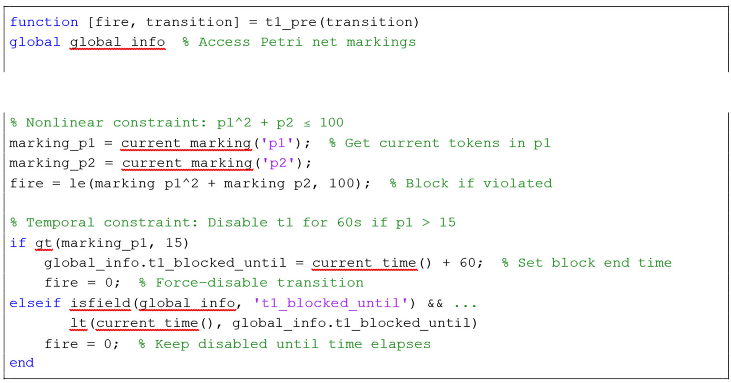

- Nonlinear constraints (e.g., quadratic, exponential) via MATLAB expressions.

- Temporal/conditional logic (e.g., disabling transitions dynamically).

- Quadratic constraint: (p12 + p2 ≤ 100).

- Temporal constraint: Transition t1 is disabled for 60 seconds if p1 exceeds a threshold.

- Pre-processor for t1 (‘t1_pre.m‘) enforces the quadratic constraint and temporal block-ing:

- 2.

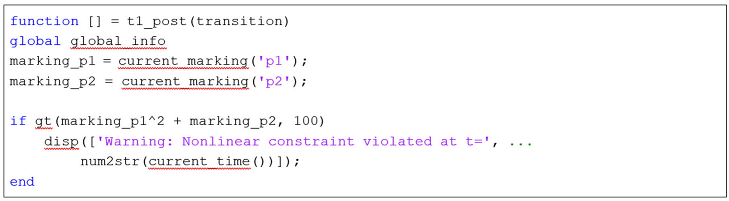

- Post-processor for t1 (‘t1_post.m‘) logs violations:

- Nonlinear arithmetic: Direct use of MATLAB’s math operators (‘^‘, ‘+‘).

- Dynamic state checks: GPenSIM’s built-in function‘current_marking’ queries real time token counts.

- Temporal control: GPenSIM’s Global variables (‘global_info‘) track blocking dura-tions.

- Integration: Leverages MATLAB’s native functions (e.g., ‘disp’) and GPenSIM’s built-in functions (e.g., ‘current_time‘).

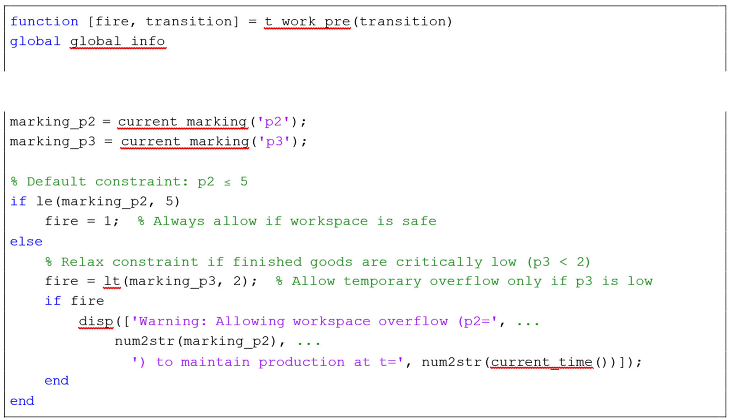

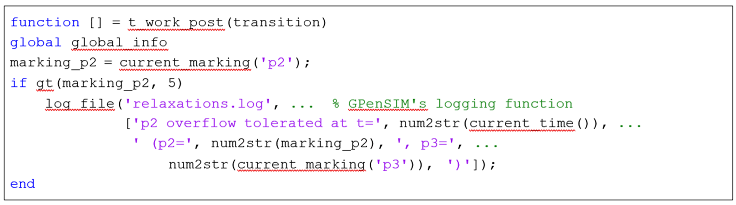

6.4. Mitigating Rigid Control via Adaptive Processors

- Conditional enabling of transitions based on real-time system state.

- Partial permissions (e.g., allowing transitions only under specific token distributions).

- Plant: Places p1 (raw materials), p2 (workspace), p3 (finished goods).

- Constraint: Avoid workspace overflow (‘p2 ≤ 5‘), but allow temporary violations if p3 is nearly empty (to maintain throughput).

- Pre-processor for t_work (‘t_work_pre.m‘) dynamically adjusts enforcement:

- 2.

- Post-processor for t_work (‘t_work_post.m‘) logs relaxations:

- Context-aware firing: Transitions are blocked only when strictly necessary (e.g., ‘p2 > 5‘ and ‘p3 ≥ 2‘).

- Real-time state checks: Uses GPenSIM’s built-in function‘current_marking‘ to evaluate tokens dynamically.

- Logging: Trades off rigor for throughput while maintaining auditability.

- GPenSIM integration: Leverages GPenSIM’s built-in functions like ‘log_file‘ for traceability.

- Theoretical Alignment: This approach aligns with Ghaffari et al.’s maximally permissive control [17] by minimizing unnecessary restrictions, while GPenSIM’s programmability avoids the complexity of formal region theory.

7. Conclusions

- Scalability: Petri Modules (Section 4) distribute control across decentralized systems (Section 6.2), minimizing synchronization delays via Inter-Modular Connectors (Figure 1).

- Theoretical Grounding: GPenSIM embodies the Theory of Connection (Section 5.1), emphasizing dynamic interdependencies between system components - a principle rooted in Bertalanffy’s systems theory [37].

- Abstraction Trade-offs: Modular decomposition requires laminar-flow models (Section 2.1), limiting applicability to highly interconnected systems.

- Verification: GPenSIM lacks native formal verification tools, though bridges to model checkers like NuSMV [51] offer partial solutions.

- Hybrid Systems: Integrating continuous dynamics (e.g., via MATLAB’s Control Toolbox).

- AI/ML Enhancements: Adaptive processors trained on historical data to optimize constraints dynamically.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramadge, P.J.; Wonham, W.M. Supervisory control of a class of discrete event processes. SIAM Journal on Control and Optimization 1987, 25, 206–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giua, A.; DiCesare, F. Petri nets and supervisory control. Discrete Event Dynamic Systems 1993, 3, 151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Murata, T. Petri nets: Properties, analysis and applications. Proceedings of the IEEE 1989, 77, 541–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; DiCesare, F. Petri net synthesis for discrete event control of manufacturing systems. IEEE Transactions on Robotics and Automation 1993, 9, 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Moody, J.O.; Antsaklis, P.J. Supervisory control of discrete event systems using Petri nets; Springer, 1998.

- Basile, F.; Chiacchio, P.; De Tommasi, G. Supervisory control of Petri nets: A survey. Annual Reviews in Control 2020, 49, 241–257. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J.L. Petri net theory and the modeling of systems; Prentice Hall PTR, 1981.

- Davidrajuh, R. Petri Nets for Modeling of Large Discrete Systems; Springer, 2021.

- Jensen, K. Coloured Petri nets: Basic concepts, analysis methods and practical use; Vol. 1, Springer, 1997.

- Wang, H.; Zhou, M. Timed Petri nets for performance analysis of automated manufacturing systems. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems 2021, 51, 1309–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, T.b. Monitoring behavior and supervisory control; Vol. 1, Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

- Iordache, M.; Antsaklis, P.J. Supervisory control of concurrent systems: a Petri net structural approach; Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

- Kaid, H.; Al-Ahmari, A.; Li, Z.; Davidrajuh, R. processes MDPI. Optimization for Control, Observation and Safety 2020, p. 387.

- Davidrajuh, R. Literature Review on Modular Petri Nets. Petri Nets for Modeling of Large Discrete Systems 2021, pp. 77–85.

- Choi, J.Y.; Reveliotis, S.A. A generalized stochastic Petri net model for performance analysis and control of capacitated reentrant lines. Robotics & Automation IEEE Transactions on 2003, 19, 474–480. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, T.S.; Lafortune, S. Decentralized supervisory control with conditional decisions: Supervisor existence. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 2002, 47, 1886–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, A.; Rezg, N.; Xie, X. Design of a live and maximally permissive Petri net controller using the theory of regions. IEEE Transactions on Robotics and Automation 2003, 19, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Reed, S.; Yang, M.H.; Lee, H. Weakly-supervised Disentangling with Recurrent Transformations for 3D View Synthesis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems-volume, 2016.

- Herzig, A.; Lang, J.; Longin, D.; Polacsek, T. A Logic for Planning under Partial Observability. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Seventeenth National Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Twelfth Conference on on Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence, July 30 - August 3, 2000, Austin, Texas, USA., 2000. Longin, D.

- Ru, Y.; Hadjicostis, C.N. Obfuscation-based partial observability in supervisory control. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 2009, 54, 1551–1565. [Google Scholar]

- Basile, F.; Chiacchio, P.; De Tommasi, G. Fault-tolerant supervisory control of Petri nets. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 2015, 60, 810–815. 504. [Google Scholar]

- Kaid, H.; Al-Ahmari, A.; Li, Z.; Davidrajuh, R. Automatic supervisory controller for deadlock control in reconfigurable manufacturing systems with dynamic changes. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahmari, A.; Kaid, H.; Li, Z.; Davidrajuh, R. Strict minimal siphon-based colored Petri net supervisor synthesis for automated manufacturing systems with unreliable resources. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 22411–22424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisig, W. Understanding Petri Nets: Modeling Techniques, Analysis Methods, Case Studies; Springer: Berlin, 2013. Modern treatment with formal methods, industrial examples, and tool support. Springer: Berlin, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Desrochers, A.A.; Al-Jaar, R.Y. Applications of Petri Nets in Manufacturing Systems: Modeling, Control, and Performance Analysis; IEEE Press: New York, 1995; Focus on manufacturing, automation, and real-time systems. [Google Scholar]

- Desel, J.; Reisig, W. The concepts of Petri nets. Software & Systems Modeling 2015, 14, 669–683. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G. Time Petri Nets and Time-Soundness. In Petri Nets: Theoretical Models and Analysis Methods for Concurrent Systems; Springer, 2022; pp. 203–236.

- Kindler, E.; Petrucci, L. Towards a standard for modular Petri nets: A formalisation. In Proceedings of the Applications and Theory of Petri Nets: 30th International Conference, PETRI NETS 2009, Paris, France, June 22-26, 2009. Proceedings 30. Springer, 2009, pp. 43–62.

- Righini, G. Modular Petri nets for simulation of flexible production systems. International Journal of Production Research 1993, 31, 2463–2477. 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.; Cha, S.D.; Kwon, Y.R. Integration and analysis of use cases using modular Petri nets in requirements engineering. IEEE Transactions on software engineering 1998, 24, 1115–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Latorre-Biel, J.I.; Jiménez-Macías, E.; García-Alcaraz, J.L.; Muro, J.C.S.D.; Blanco-Fernandez, J.; Parte, M.P.D.L. Modular construction of compact Petri net models. International Journal of Simulation and Process Modelling 2017, 12, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Wang, F.J. An object-oriented modular Petri nets for modeling service oriented applications. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual International Computer Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC 2007). IEEE, 2007, Vol. 2, pp. 479–486.

- Lakos, C.; Petrucci, L. Modular state spaces for prioritised Petri nets. In Proceedings of the Monterey Workshop. Springer; 2010; pp. 136–156. [Google Scholar]

- Davidrajuh, R. A New Modular Petri Net for Modeling Large Discrete-Event Systems: A Proposal Based on the Literature Study. Computers 2019, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.; Stumptner, M.; Nandagopal, N.; Mayer, W.; Mansell, T. Rule-based peer-to-peer framework for decentralized real-time service oriented architectures. Science of Computer Programming 2015, 97, 202–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutarraf, U.; Barkaoui, K.; Li, Z.; Wu, N.; Qu, T. Transformation of Business Process Model and Notation models onto Petri nets and their analysis. Advances in Mechanical Engineering 2018, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertalanffy, L.v. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications; George Braziller: New York, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Bertalanffy, L.v. The Theory of Open Systems in Physics and Biology. Science 1950, 111, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrester, J.W. Industrial Dynamics; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, J.W. World Dynamics. Studies in the Life Sciences 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F. The Web of Life: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems; Anchor Books: New York, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F. The Turning Point: Science, Society, and the Rising Culture; Simon & Schuster, 1982.

- Bjorke, O. Manufacturing Systems Theory. Tapir Academic Press 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Davidrajuh, R. Planning e-government start-up: a case study on e-Sri Lanka. Electronic Government, an International Journal 2004, 1, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidrajuh, R. Automating supplier selection procedures. PhD Thesis 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Davidrajuh, R. Array-based logic for realising inference engine in mobile applications. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation 2007, 1, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidrajuh, R. Modeling Discrete-Event Systems with GPenSIM; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidrajuh, R. GPenSIM Reference Manual; University of Stavanger, 2024.

- Feng1, Y.; Samolej, S.; Davidrajuh, R. Application Interface for GPenSIM. In Proceedings of the Systems Modelling and Simulation: First International Symposium, SMS 2024, Johor Bahru, Malaysia, December 16–17, 2024, Proceedings. Springer Nature, 2025, Vol. 2483, p. 237.

- Forrester, J.W. Principles of Systems. MIT Press 1968. Later expanded into the book "Principles of Systems" (1968).

- Roci, A.; Davidrajuh, R. Developing a Bridge from GPenSIM to NuSMV for Model Checking. European Modeling & Simulation Symposium 2021.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).