1. Introduction

Dating violence among adolescents and young adults is a growing concern in both global and local contexts, given its severe implications for mental, physical, and social well-being (Cénat et al., 2022; García-Díaz et al., 2017; Giordano et al., 2021; Klencakova et al., 2023; Rodríguez-Díaz et al., 2017; Tomaszewska & Schuster, 2021). Despite extensive international research, gaps remain in understanding the cultural and contextual factors influencing dating violence, particularly in Latin America. Most studies focus on physical and psychological abuse, but coercion, humiliation, and detachment also play critical roles in victimization and perpetration (Aguilera-Jiménez et al., 2021; López-Barranco et al., 2022). These indicators help capture the complexity of dating violence beyond direct aggression. In Ecuador, research on this topic remains scarce, despite increasing evidence that intimate partner violence is a significant public health issue (Carney, 2024; Edeby & San Sebastián, 2021). Studies in Latin America suggest that gender differences influence the prevalence and forms of dating violence, with women experiencing higher rates of victimization, particularly in emotional and sexual abuse, while men report higher rates of physical aggression as perpetrators (Medina-Maldonado et al., 2022). Social desirability plays a crucial role in help-seeking behaviors. Victims may underreport their experiences due to fear of stigma or cultural norms that minimize dating violence. Understanding these dynamics is essential for developing effective interventions and policies tailored to the Ecuadorian context.

Network analysis offers a powerful framework for studying dating violence by enabling researchers to map and visualize the intricate relationships among the many factors that contribute to the experience of violence (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2023). This approach enhances understanding of the structural and functional roles of various variables within the network, highlighting which factors are central, which act as bridges, and which, while less prominent, still play meaningful roles (Borsboom et al., 2021; Hevey, 2018). Unlike traditional statistical methods that often examine variables in isolation, network analysis provides a holistic view of the dynamic interplay of factors involved in dating violence (Wong et al., 2023).

The variables included in this study cover a broad range of personal, relational, and contextual factors that influence both the perpetration and victimization of violence (Marr et al., 2024; Michael et al., 2023). Age and socioeconomic level are critical demographic variables that have been widely discussed in the literature on dating violence, as younger individuals and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds often face higher risks of both experiencing and perpetrating violence (Dardis et al., 2015; Duval et al., 2020; Costa et al., 2015). Fear and stress are emotional responses that frequently accompany victimization and perpetration, reflecting the psychological toll of abusive relationships (Frieze et al., 2020; Sullivan et al., 2023).

The feeling of being trapped or maltreated is commonly reported among victims of dating violence, highlighting the psychological and emotional aspects of coercion and control within abusive relationships (Puente-Martínez et al., 2023). These are further complemented by behaviors such as hostility and benevolence, which represent the relational dynamics between partners (Lee et al., 2010). Benevolent behaviors may include acts of kindness or care that could mask underlying control or manipulation, a common feature in abusive relationships that involve cycles of violence and reconciliation (Lachance-Grzela et al., 2021).

The family level, family functioning is a key variable that influences the likelihood of experiencing or perpetrating dating violence (Emanuels et al., 2022; Park & Kim, 2018; Sianko et al., 2020). Dysfunctional family environments are often linked to higher incidences of dating violence, as they may foster maladaptive coping strategies, conflict resolution skills, and emotional regulation (Cascardi & Jouriles, 2018; Southern & Sullivan, 2021). Social desirability is another factor that may influence how individuals report their experiences of violence, as they may underreport violent behaviors or exaggerate their responses to fit social norms (Freeman et al., 2015).

In terms of the specific behaviors of victimization and perpetration, this study distinguishes between several forms of violence. Coercion refers to behaviors where one partner forces the other into certain actions or decisions, often through threats or pressure (Fernández-Fuertes et al., 2018; Zavala & Kurtz, 2021). Humiliation involves behaviors that degrade or belittle the partner, attacking their self-esteem and self-worth (Oflaz et al., 2023). Detachment reflects emotional withdrawal, where one partner distances themselves emotionally from the other, contributing to the erosion of trust and intimacy in the relationship (Aguilera-Jiménez et al., 2021). Sexual and physical violence are the more overt and severe forms of abuse, involving physical force or sexual coercion, which are often the focus of traditional studies on intimate partner violence (Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2022; Piolanti & Foran, 2022).

This study seeks to integrate these variables into a network analysis to explore how they interact and contribute to the overall dynamics of dating violence among Ecuadorian youth. By employing this approach, we aim to identify the factors that are most central to the experience of violence and those that may serve as key points for intervention in preventing or reducing dating violence within this population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

A non-experimental, descriptive, and correlational design was employed. Network analysis was used to identify and examine the connections between variables associated (Christensen & Kenett, 2023) with victimization and perpetration of dating violence. This approach analyzed both direct and indirect relationships between the variables, using centrality metrics such as closeness, betweenness, strength, and expected influence (Hevey, 2018; Rocco et al., 2024).

2.2. Participants

The sample comprised 836 young Ecuadorians aged 15 to 26 years (M = 20.78, SD = 2.648), selected through convenience sampling from high schools and universities, ensuring gender and socio-economic diversity. The gender distribution was nearly equal, with 52% women (n = 432) and 48% men (n = 404). Participants were predominantly younger adults, with 58% aged 14–21 and 42% aged 22–26.

Most identified as Mestiza (90%), followed by Indigenous (6.5%), with smaller groups identifying as Afro-Ecuadorian, White, Montubio, or Other. Regarding socio-economic status, 67% reported middle-level, 17% lower-middle, 12% upper-middle, and smaller percentages indicated low (1.8%) or high (1.6%) status. Geographically, participants were primarily from Quito (40%) and Tulcán (21%), with notable representation from Esmeraldas (17%), Azogues (11%), and Loja (8.6%). Other cities, including Machachi and Riobamba, each accounted for less than 1% of the sample. The educational institutions were from the cities geographically mentioned above.

2.3. Instruments

Ad-Hoc Sociodemographic: A custom form was administered to collect sociodemographic data such as age (from 14 to 26 years old), gender (man and woman), and socioeconomic level (low, medium, medium-high and high).

Dating Violence Questionnaire for Victimization and Perpetration (DVQ-VP): Rodríguez Franco et al. (2022), serves as a dual-function assessment instrument with two subscales. One subscale measures violence experienced by individuals, while the other evaluates violence committed within romantic relationships. Both subscales are organized around five identical dimensions that explore different aspects of dating violence. Beyond its use in detecting and assessing violence, the DVQ-VP offers valuable insights into the reciprocal nature of victimization and perpetration. The details of each subscale are outlined below:

Dating Violence Questionnaire for Victimization (DVQ-R): Was utilized to assess experiences of dating violence victimization by the current partner. It consists of 20 items that evaluate five types of victimization: physical (e.g., "Has your partner ever hit you?"), sexual (e.g., "Does your partner persist in touching you in ways or places you don’t like or want?"), humiliation (e.g., "Does your partner criticize, belittle, or undermine your self-esteem?"), detachment (e.g., "Does your partner refuse to take responsibility in the relationship?"), and coercion (e.g., "Has your partner ever physically restrained you?"). Each type of victimization is measured using four items on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (all the time) (α = .83, ω = .87, CFI = .995, TLI = .993, RMSEA = 0.02).

Dating Violence Questionnaire for Perpetration (DVQ-RP): Is a modified version of the DVQ-R, adapted to assess aggression directed towards the partner. It includes 20 items that evaluate five types of dating violence perpetration: physical (e.g., "Have you ever hit your partner?"), sexual (e.g., "Do you persist in touching your partner in ways or places they don’t want or like?"), humiliation (e.g., "Do you criticize, belittle, or undermine your partner’s self-esteem?"), detachment (e.g., "Do you fail to acknowledge any responsibility in the relationship?"), and coercion (e.g., "Have you ever physically restrained your partner?") (α = .85, ω = .87, CFI = .992, TLI = .991, RMSEA = .02).

Gender Attitudes: The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory, developed by Glick and Fiske in 1996, was used. This scale consisted of 22 items with a Likert-type response scale ranging from 0 to 5, where higher scores indicated higher levels of sexism. The reliability for Hostile Sexism (HS) was α = .82, while for the Benevolent Sexism (BS) subscale it was α = .77. The Spanish-adapted version used in Spanish-speaking countries (Expósito et al., 1998) was employed in this study.

Motivations for Perpetrating Violence in Adolescent and University Student Romantic Relationships: This instrument consisted of 13 items. Participants were presented with a list of reasons that might have caused conflicts with their partners. These reasons were grouped into emotional expression/dysregulation (α = .89), control (α = .80), and self-defense (α = .83), with additional reasons categorized subsequently (Kelley et al., 2015).

Stress: A brief 4-item version of the Perceived Stress Scale (Herrero & Meneses, 2006) was used. This scale demonstrated adequate psychometric properties, with an α = .83.

Family Assessment Scale (APGAR): The APGAR family scale (Smilkstein, 1978, Campo-Arias y Caballero-Domínguez, 2021) assessed basic functions such as adaptation, participation, resource gradient, affection, and problem-solving ability, which are present in all families regardless of their structure, development, integration, or demographics. Each question was scored on a scale from 0 to 2, resulting in a final index ranging from 0 to 10. Three outcome categories were considered: normal functionality (7-10 points), moderate dysfunction (4-6 points), and severe dysfunction (0-3 points) (α = .82, ω = .82, CFI = .998, TLI = .996, RMSEA = .024).

Social Desirability: The abbreviated Spanish version of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale was used, which showed adequate internal consistency with α = .71 (Gutiérrez et al., 2016).

2.4. Procedure

We reached out to educational institutions to invite student participation in the study. The study objectives were thoroughly explained to the institutions, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The questionnaires were administered anonymously through paper surveys, based on each institution's preference. To ensure confidentiality, the data were securely stored, and measures were implemented to protect participants' privacy. The results of the questionnaires were coded prior to analysis to safeguard participant identities and maintain the integrity of the data.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using JASP version 0.18.3.0 and Jamovi version 2.3.28. A network analysis was performed to identify relationships between victimization and perpetration variables. This involved using centrality metrics such as strength, closeness, betweenness, and expected influence to determine the most significant nodes within the network (Jones et al., 2021). Centrality Plots focus on identifying the most central or influential nodes within the network. Centrality measures quantify the importance of a node based on its position and connections. Common metrics include degree centrality (the number of direct connections a node has), betweenness centrality (how frequently a node acts as a bridge along the shortest path between two other nodes), and closeness centrality (how close a node is to all other nodes). Centrality plots visually represent these metrics, highlighting the nodes that play critical roles in the network’s connectivity and flow (Saxena & Iyengar, 2020). Network Diagrams visually represent the connections between different variables or entities (Mantzaris et al., 2019). They illustrate how each component is linked to others, enabling an understanding of the overall network structure. In these diagrams, nodes represent variables or entities, while edges (lines connecting the nodes) depict the relationships or interactions between them (Robinaugh et al., 2016). This visualization aids in identifying patterns and relationships that may not be immediately obvious from raw data alone. Clustering Plots are used to identify and visualize groups or clusters of nodes that are more closely related to each other than to other nodes in the network (Dalmaijer et al., 2022). These plots help detect community structures within the network, showing how nodes are grouped based on their similarities and interactions. Various clustering algorithms, such as k-means or hierarchical clustering, can be employed to categorize nodes into distinct clusters. The resulting clustering plot visually distinguishes these groups, providing insights into the network’s modularity and the underlying structure of the data.

3. Results

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and psychological characteristics of 836 participants, primarily young adults with an average age of 20.78 years (SD = 2.648) and a socioeconomic level centered around level 3 (M = 2.95, SD = 0.652), reflecting a middle-class background. Most participants reported relatively uniform experiences of fear (M = 1.801, SD = 0.399), feeling trapped (M = 1.79, SD = 0.407), and mistreatment (M = 1.882, SD = 0.323), with scores concentrated at level 2. Hostility (M = 20.01, SD = 13.647) and benevolence (M = 18.97, SD = 12.388) showed greater variability, indicating diverse experiences. Stress levels were moderately variable (M = 8.623, SD = 2.523), while family functioning scores (M = 13.01, SD = 5.204) reflected mixed perceptions of family dynamics. Social desirability (M = 17.48, SD = 4.916) exhibited moderate variability in responses.

Victimization and perpetration behaviors, including coercion, humiliation, detachment, and physical and sexual violence, showed low means and standard deviations, suggesting these behaviors are infrequently reported or experienced among participants. Overall, the data points to limited prevalence of victimization and perpetration within this group.

The analysis revealed significant correlations between variables related to dating violence. Higher socioeconomic status was associated with lower stress, fewer reasons for staying, and reduced victimization. Emotional factors like fear, feeling trapped, and feeling mistreated were strongly interconnected. Victimization and perpetration showed significant interrelations, indicating shared patterns in violent dynamics. Family functionality positively influenced social desirability, while stress increased vulnerability to victimization. Overall, the findings highlight the complex interplay of emotional, social, and familial factors, suggesting a need for integrated prevention and intervention strategies (Supplementary

Table 1).

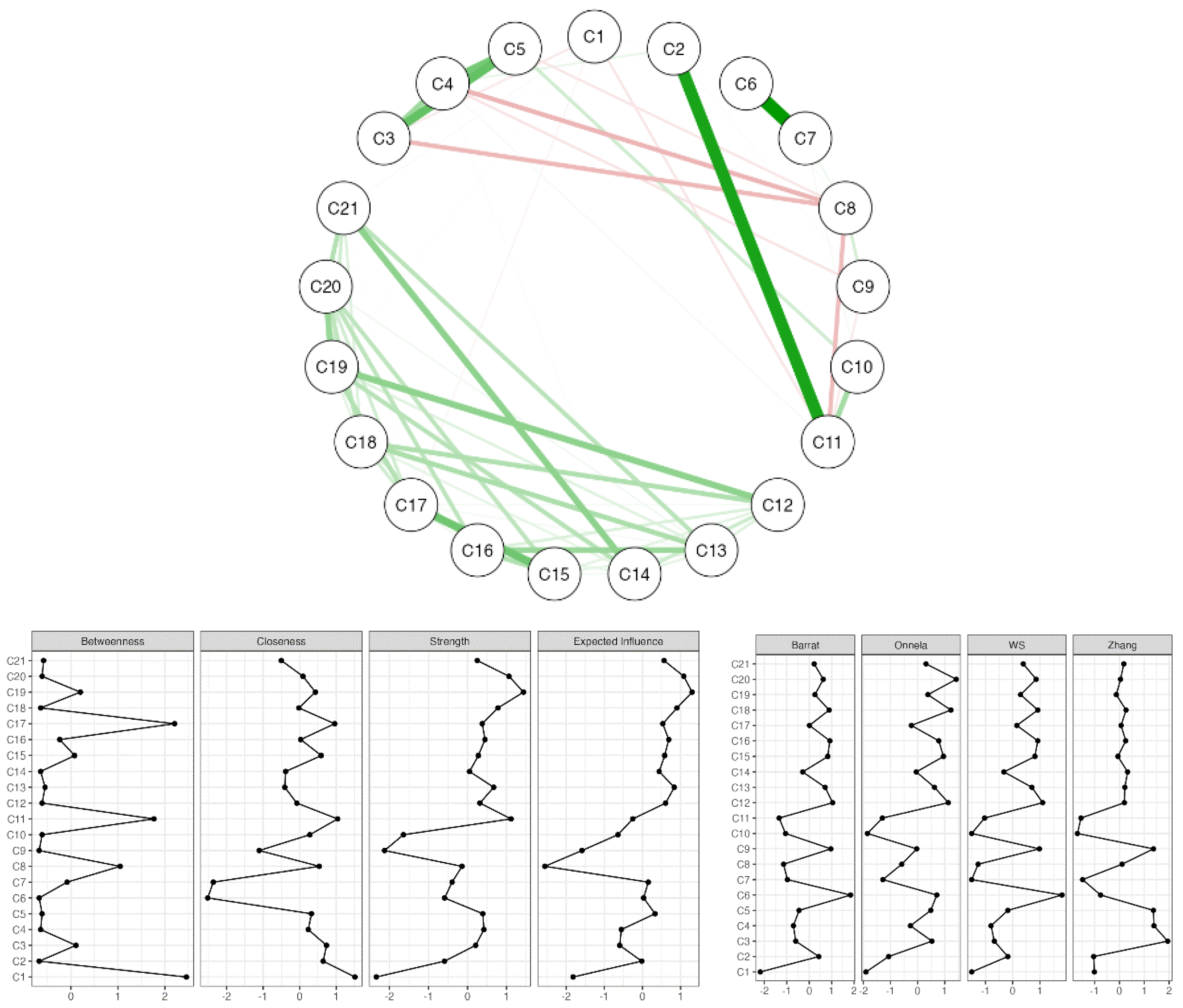

The network you present shows the relationships between various variables associated with victimization and perpetration of dating violence among Ecuadorian youth (

Figure 1). Each node (C1-C21) represents a specific variable, and the lines between them indicate the relationship between these variables, using the thickness and color of the lines to differentiate the magnitude and type of correlation. First, demographic variables such as C1 (Age) and C2 (Socioeconomic Level) are observed. These relate to other emotional and perception factors, such as C3 (Fear), C4 (Feeling Trapped), and C5 (Feeling Mistreated). These emotions reflect the psychological state of young people experiencing dating violence and are key factors in how they navigate these relationships.

Additionally, the connections between hostile and benevolent partner behavior, represented by C6 (Hostile) and C7 (Benevolent), are highlighted. For instance, C6 (Hostile) is strongly related to C2 (Socioeconomic Level) and C11 (Social Desirability). This suggests that young people from lower socioeconomic levels or those who seek to be perceived positively by others may be more likely to exhibit or experience hostile behaviors in their relationships. C11 (Social Desirability) is highly interconnected with various forms of victimization and perpetration, suggesting that the desire to be socially accepted may influence how young people report or perceive their involvement in dating violence. The categories of victimization (C12-C16), which include coercion, humiliation, detachment, sexual and physical violence, are also closely related to the categories of perpetration (C17-C21), indicating a possible reciprocity or cycle of violence in these relationships. In other words, those who are victims of one type of violence may also be perpetrators at another time or under different circumstances.

The diagram highlights the interconnectedness of victim and aggressor roles in dating violence, emphasizing the complex interactions between personal, social, and emotional factors. It suggests that victimization and perpetration are often intertwined and influenced by social and family dynamics. The centrality graph further explores the importance of different variables in dating violence through four metrics betweenness, closeness, strength, and expected influence offering unique insights into how these variables act as bridges, direct influencers, or have broader impacts on the dynamics of violence.

Variables associated with the perpetration of physical and sexual violence, such as C21 (Physical Violence - Perpetration) and C20 (Sexual Violence - Perpetration), demonstrate high betweenness centrality, underscoring their role as key mediators within the network of dating violence. These variables connect emotional, social, and family factors, shaping the overall network dynamics. Closeness centrality highlights the influence of victimization variables like C14 (Detachment - Victimization) and C16 (Physical Violence - Victimization), which exhibit strong interconnections, indicating the centrality of victimization experiences in the structure of relationships. Strength centrality identifies variables such as C2 (Socioeconomic Level) and C11 (Social Desirability) as particularly impactful, revealing that social factors significantly shape both victimization and perpetration. Moreover, expected influence metrics emphasize the profound impact of perpetration variables like C21 and C18 (Humiliation - Perpetration) on the network, suggesting their critical role in perpetuating dating violence dynamics.

Clustering algorithms provide further insights into the relationships among variables in the network. The Barrat algorithm emphasizes strong connections between perpetration variables, highlighting their centrality and tendency to cluster with victimization or emotional factors, reflecting reciprocity in dating violence dynamics. The Onnela algorithm reveals a more balanced relationship between victimization and perpetration, with physical violence acting as a central link across clusters. Meanwhile, the WS algorithm integrates broader social and family contexts, such as C10 (Family Functioning) and C2 (Socioeconomic Level), alongside perpetration variables, offering a comprehensive perspective.

These findings underscore the pivotal roles of violence, both as victimization and perpetration, as well as socioeconomic and social factors, in shaping the dynamics and clustering patterns of dating violence. Each clustering method provides a distinct lens through which to understand the interplay of variables within dating violence networks, ranging from focusing on the strength of connections to incorporating broader social and family influences.

Finally, the Zhang algorithm places significant emphasis on demographic variables, such as C1 (Age) and C2 (Socioeconomic Level). Under this approach, age and socioeconomic level are positioned as key variables in determining groups within the network. Additionally, victimization and perpetration variables follow a more predictable pattern in this approach, suggesting that Zhang prioritizes demographic factors to understand how individuals cluster within the violence network (

Figure 1).

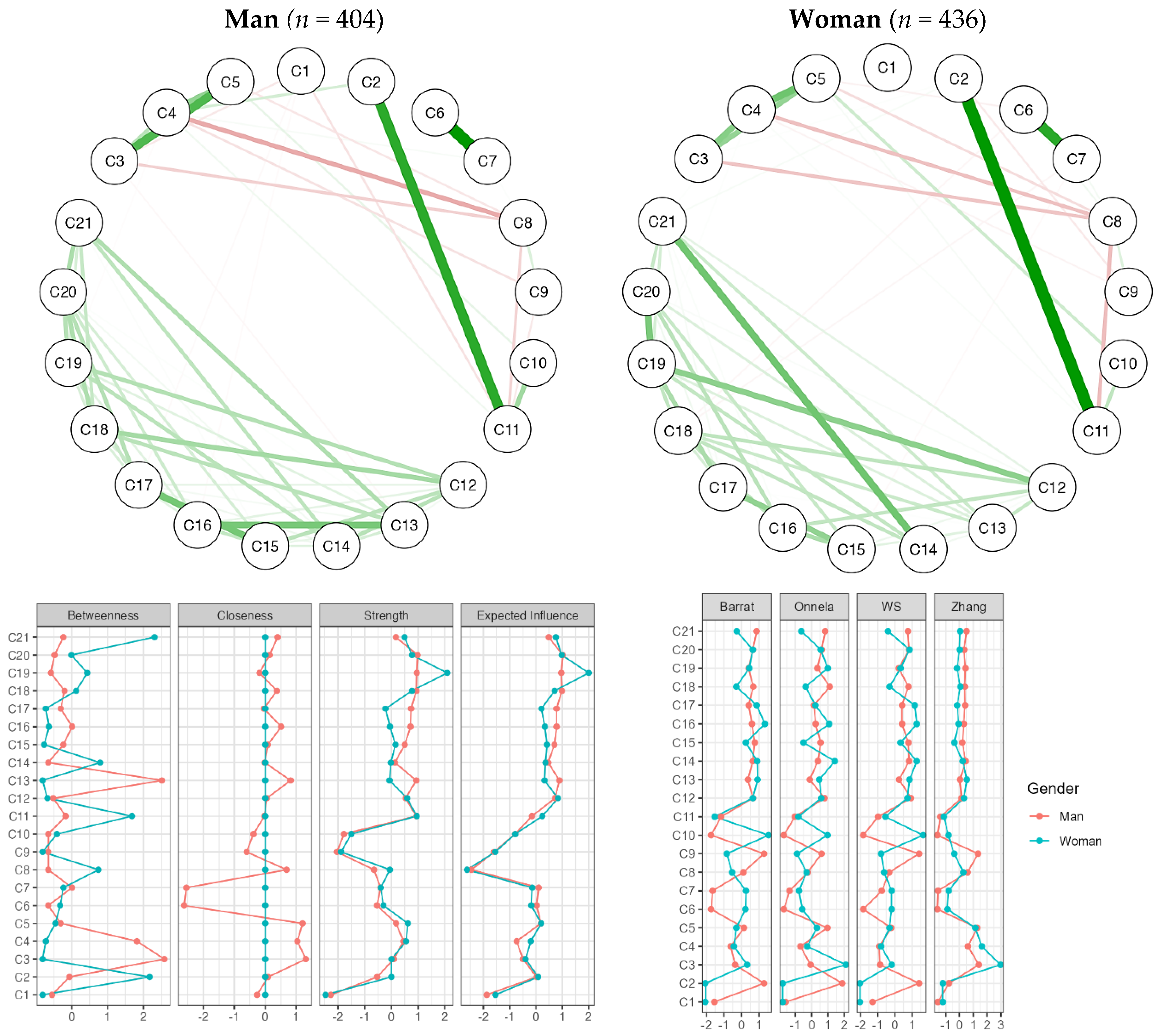

Figure 2 provides a detailed comparative analysis of the network structure, centrality measures, and clustering patterns of numerous factors as a function of gender, with separate analyses for men (n = 404) and women (n = 436). The upper part of the figure depicts the networks for people, where each circle represents a variable (C1 to C21), and the lines between them indicate the strength and direction of the relationships. Thicker lines represent stronger connections. Notable variables like C2 (Socioeconomic level), C11 (Social Desirability), and C12 (Coercion, Victimization) show significant connectivity, suggesting their significant role in the network across both genders, albeit with some differences in the strength and direction of these relationships. The centrality plots in the lower section of the figure display different centrality measures—Betweenness, Closeness, Strength, and Expected Influence—for each variable, which helps in understanding the prominence and influence of each variable within the network for men and women. For instance, variables like C11 and C2 appear to have high centrality across multiple measures, indicating their critical role in the network. The expected influence measure shows how much impact a variable can have on the rest of the network, which is crucial for understanding underlying dynamics in conflict resolution styles or victimization experiences.

The clustering plots further dissect how these variables group together within the network for each gender. These clusters indicate the presence of subgroups of variables that are more closely related to each other, revealing patterns that may differ significantly between men and women. For example, victimization-related variables (e.g., C12, C13, C14, C15, C16) might cluster differently between the two genders, suggesting that the experience or perception of victimization may be gender-specific.

Overall,

Figure 2 highlights the complex interplay of socioeconomic factors, emotional states, victimization experiences, and social perceptions, with clear gender-specific patterns. These differences in network structure, centrality, and clustering could have important implications for targeted interventions or policies aimed at addressing issues like victimization, socioeconomic disparities, or social desirability biases in different gender groups. The analysis underscores the importance of considering gender when studying these variables, as the relationships and influence of each factor can vary significantly between men and women.

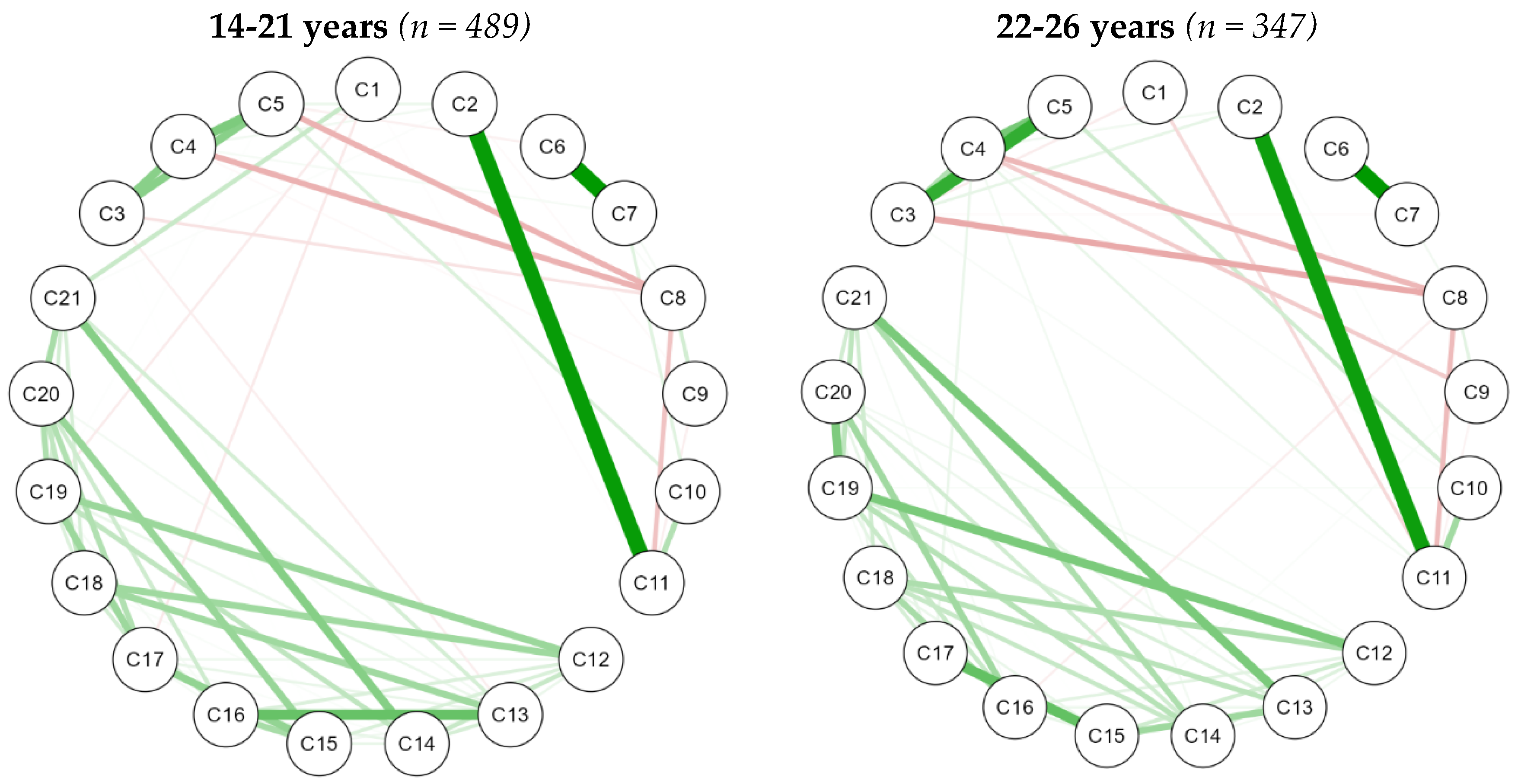

Figure 3 illustrates the comparison of network structures, centrality measures, and clustering patterns of numerous factors based on two different age groups: 14-21 years (n = 489) and 22-26 years (n = 347). The networks at the top show how variables (C1 to C21) are interconnected, with the thickness of the lines indicating the strength of these connections. Key variables like C2 (Socioeconomic level), C11 (Social Desirability), and C12 (Coercion, Victimization) display strong connections across both age groups, although the patterns and intensities differ.

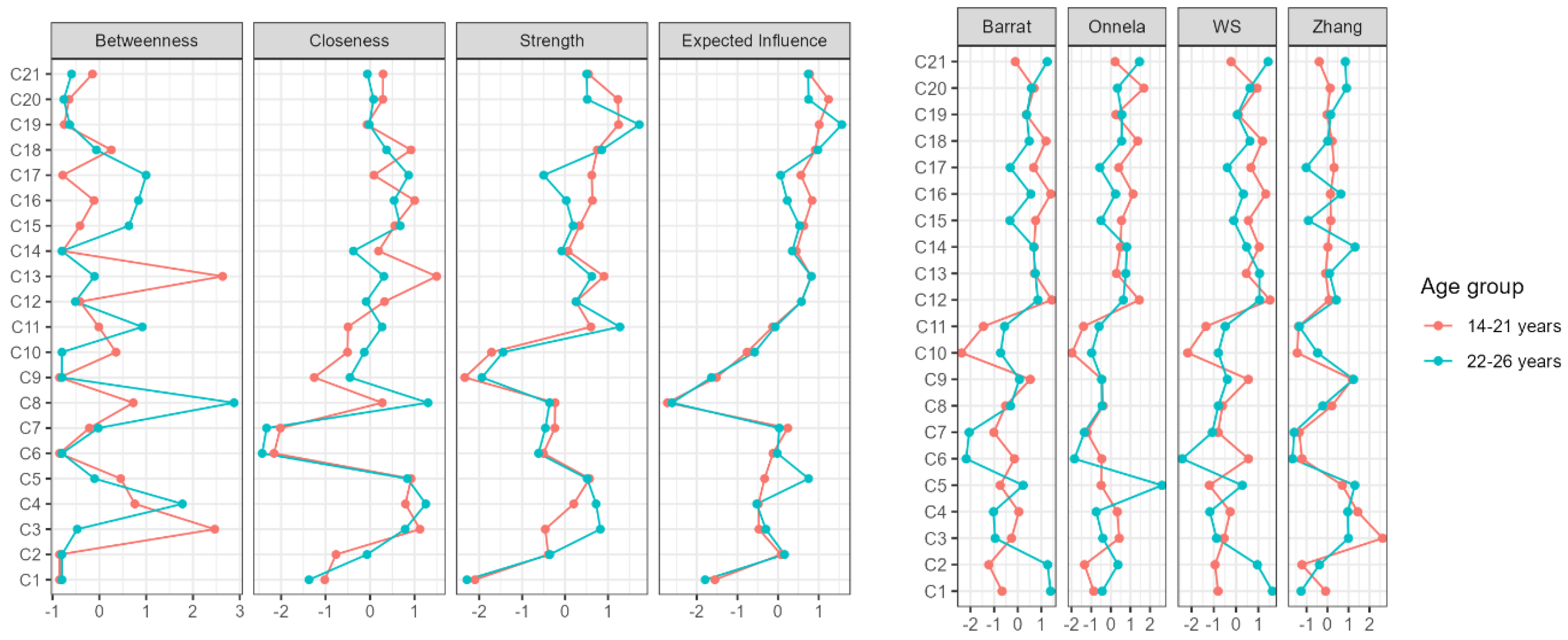

The centrality plots in

Figure 3 provide critical insights into the prominence of variables within the network across different age groups, using measures like Betweenness, Closeness, Strength, and Expected Influence. These metrics reveal age-related differences in variable influence, with factors such as C11 and C12 displaying varying centrality levels between younger (14–21 years) and older (22–26 years) groups. Such differences suggest that the interactions between socioeconomic factors, emotional states, and experiences of victimization evolve with age, shaping the network dynamics distinctively for each group.

The clustering plots further illustrate how variables group differently between age groups. Victimization-related variables (e.g., C12, C13, C14, C15, C16) cluster distinctly in younger versus older groups, indicating potential age-related variations in how victimization is perceived or experienced. These patterns underscore the complexity of relationships among socioeconomic factors, emotional states, and social perceptions, highlighting clear differences in network structure between age groups. This age-specific variability in centrality and clustering suggests the need for tailored interventions and support strategies that address the unique dynamics of these factors in different age demographics.

4. Discussion

The analysis of victimization and perpetration networks in dating violence among Ecuadorian youth, based on centrality and clustering graphs, provides a comprehensive view of how different variables relate to this complex issue. From a centrality perspective, the results indicate that variables related to the perpetration of physical and sexual violence play a crucial mediating role in the network, suggesting that these forms of violence are key nodes in the interactions between socio-emotional and familial factors. Victimization variables, such as detachment and physical violence, also show a high level of connection, highlighting their central role in the network, both in terms of being influenced by and influencing other variables. These findings align with previous research in Latin America, which emphasizes the cyclical nature of dating violence and the role of contextual factors in its perpetuation (Dardis et al., 2015; Park et al., 2018; Sánchez-Zafra et al., 2024). They contribute to a deeper understanding of dating violence in Ecuador by illustrating how different forms of aggression interact within a broader social and emotional framework (Machado et al., 2024; Valdivia-Salas et al., 2024). Additionally, stigma and social desirability significantly impact the reporting of dating violence. Victims may underreport their experiences due to fear of judgment, cultural norms that normalize certain forms of abuse, or concerns about social repercussions. This reluctance to disclose violence affects the accuracy of prevalence estimates and limits access to support services (Dardis et al., 2015; Valdivia-Salas et al., 2024). Addressing these barriers is crucial for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies tailored to the Ecuadorian context.

The clustering analysis complements this understanding, showing that different algorithms highlight various aspects of the network. The Barrat algorithm emphasizes the connection between forms of violence perpetration and their relationship with key variables, suggesting that perpetrated violence tends to cluster around shared experiences or common emotional factors. Onnela, in turn, shows greater integration between victimization and perpetration, reinforcing the notion of reciprocity in intimate partner violence. The WS method provides a more contextual perspective, indicating that factors such as socioeconomic level and family functioning also significantly influence the dynamics of violence, while Zhang highlights the importance of demographic variables like age and socioeconomic level in the network structure.

These findings are consistent with the literature on dating violence, which suggests that experiences of violence are influenced by a combination of individual, relational, and contextual factors. The presence of variables such as fear, stress, and social desirability in the networks suggests that emotional and social responses play a crucial role in how youth experience and perpetuate violence in their relationships. Additionally, the prominence of family functioning as a key factor underscores the importance of supportive contexts and family dynamics in the perpetuation or prevention of violence (Paat & Markham, 2019).

The comparative analysis of network structures, centrality measures, and clustering patterns across gender provides significant insights into the differential dynamics of conflict resolution styles, victimization experiences, and social factors among men and women. These differences are crucial for understanding how gender shapes the way individuals navigate social and personal conflicts and how they are influenced by various psychological and social variables (Michael et al., 2023).

The network structures for men and women reveal shared central variables, such as socioeconomic level (C2) and social desirability (C11), but distinct gender-specific patterns in variable interconnections. For men, stronger connections emerge between social desirability (C11), victimization, and perpetration variables (e.g., C12, C21), suggesting the influence of social perception and external validation on aggression and victimization. In contrast, women's networks emphasize emotional and psychological states, such as fear (C3) and benevolence (C7), highlighting the importance of internal emotional experiences and interpersonal relationships (Théorêt et al., 2021).

Centrality plots show that for men, social desirability (C11) exhibits high centrality across measures like betweenness and expected influence, underscoring the role of societal expectations and social standing in shaping male behaviors, particularly in conflict and aggression. For women, family functioning (C10) and benevolence (C7) are more central, indicating the influence of family dynamics and prosocial behaviors on their conflict experiences (Portugal et al., 2023; Terrazas-Carrillo et al., 2024).

Clustering analysis highlights gender-specific groupings of variables. For men, victimization and perpetration variables (e.g., C12, C17, C18) cluster closely, suggesting a potential cycle of aggression and victimization tied to societal expectations of masculinity. For women, clusters center around emotional and relational variables, such as benevolence (C7) and family functioning (C10), reflecting societal norms emphasizing relational harmony and nurturing. These differences underscore distinct gendered ways of experiencing and processing conflict and victimization (Minto et al., 2022).

Gender-specific patterns in network structure, centrality, and clustering provide crucial insights for targeted interventions. For men, the strong influence of social desirability and the interconnectedness of victimization and perpetration behaviors suggest the need for programs that challenge harmful social norms and promote healthier models of masculinity, focusing on reshaping perceptions and fostering constructive conflict resolution strategies. For women, the centrality of family dynamics highlights the importance of family-based interventions aimed at improving communication and addressing emotional and relational conflicts. These programs should emphasize fostering healthy family functioning and equipping families with conflict resolution skills to effectively mitigate the impacts of dating violence.

The analysis of network structures, centrality measures, and clustering patterns across age groups further reveals how factors like socioeconomic status, emotional states, victimization, and social perceptions interact as individuals transition from late adolescence to early adulthood. This nuanced understanding of age and gender differences in the dynamics of dating violence is crucial for developing interventions tailored to the specific needs of different demographic groups, ensuring greater efficacy in addressing these complex issues. In terms of network structure, while the fundamental relationships between variables remain consistent across the 14-21 years and 22-26 years age groups, the strength and nature of these relationships evolve with age. In both groups, variables such as socioeconomic level (C2) and social desirability (C11) emerge as central nodes, indicating their continuous relevance. However, these connections are more robust in the older age group, suggesting that socioeconomic status and social desirability become more intricately linked with other aspects of life as individuals age, possibly due to increased social expectations and pressures (Young et al., 2021).

Centrality measures reveal age-related shifts in the importance of specific variables within the network. For younger individuals (14-21 years), variables associated with immediate emotional responses, such as fear (C3) and feeling trapped (C4), exhibit higher centrality, particularly in terms of closeness and expected influence. This may reflect heightened emotional sensitivity and social anxiety commonly experienced during adolescence, where feelings of fear and entrapment significantly impact other aspects of life. In contrast, for the older group (22-26 years), variables related to victimization, such as coercion (C12) and physical victimization (C16), show increased centrality, especially in terms of betweenness. This suggests that experiences of victimization become more central in social and psychological networks as individuals move into early adulthood, likely due to increased exposure to complex social environments (Claussen et al., 2022).

Clustering patterns highlight age-specific differences in dating violence dynamics. Among younger individuals, clusters focus on emotional and psychological variables like fear, stress, and feelings of entrapment, emphasizing the need for interventions targeting emotional regulation and coping strategies. In contrast, older individuals show clusters involving both victimization and perpetration variables (e.g., C12, C17, C18, C19), reflecting a complex interplay of these roles. This suggests that interventions for this group should address both victim and perpetrator perspectives, incorporating conflict resolution, empathy, and accountability strategies (Malhi et al., 2020; Murta et al., 2020; Puffer et al., 2020). These findings underscore the importance of tailoring interventions to the developmental and relational needs of each age group.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of this analysis highlight that dating violence among Ecuadorian youth is a complex network influenced by a combination of personal, emotional, familial, and contextual factors. Perpetrated forms of violence, particularly physical and sexual violence, play a central role as mediators within this network, connecting various experiences and factors. At the same time, victimization-related variables, such as detachment and fear, demonstrate a high level of interconnection, emphasizing their significance in the experience of violence.

The clustering analysis confirms that contextual and demographic factors, such as socioeconomic status and age, significantly influence the configuration of violence networks. This suggests that violence is not merely a direct interaction between victim and perpetrator but also involves crucial social and familial contexts. This holistic understanding of dating violence underscores the need for interventions that not only address violence directly but also include strategies to improve family functioning, reduce stress and fear, and foster a more supportive socioeconomic and emotional environment for youth.

To effectively address dating violence, multidimensional approaches must consider individual and contextual factors, with an emphasis on family support, emotional health, and socioeconomic conditions. Public policies and intervention programs should prioritize early prevention and the development of robust support networks, especially within the Ecuadorian context, where these dynamics are intricately intertwined. Gender-specific analyses of networks, centrality, and clustering highlight the need to address distinct dynamics in conflict resolution styles, victimization, and societal expectations. Tailoring interventions to these patterns can enhance their effectiveness, fostering more nuanced outcomes in conflict prevention and resolution. Furthermore, age-based analyses reveal developmental shifts from emotional and psychological concerns in adolescence to complex social and relational dynamics in early adulthood, particularly regarding victimization and perpetration. Recognizing these transitions is key to designing effective, age-appropriate interventions that cater to the evolving challenges at each developmental stage.

This study has several limitations, including its cross-sectional design, which prevents establishing causal relationships and understanding how dating violence dynamics evolve over time. The sample was limited to Ecuadorian youth, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings, and self-reports may have introduced biases. Additionally, important factors like substance use, family violence history, and external influences such as fear and stress were not considered, potentially affecting the comprehensiveness of the analysis.

Despite its limitations, this study provides a critical foundation for understanding the networks of victimization and perpetration in dating violence and underscores the need for further research. Longitudinal studies are recommended to examine the evolution of violence dynamics, identify causal relationships, and detect patterns that predict escalation or reduction (Brem et al., 2021). Expanding research to include diverse sociocultural contexts could uncover contextual factors influencing dating violence and improve the generalizability of findings (Padilla-Medina et al., 2022). From a methodological perspective, incorporating objective measures such as interviews or observations and including additional variables, such as social media use, substance use, and family background, could provide a more comprehensive understanding (Taylor & Sullivan, 2021). Finally, designing and evaluating preventive interventions aimed at reducing violence, enhancing family functioning, managing stress, Conflict Resolution, and improving youth mental health is vital for developing effective strategies (Ramírez et al., 2024; Wong et al., 2023; McNaughton Reyes et al., 2021; Sánchez-Jiménez et al., 2018).

For future research, it is recommended to further explore the interaction between the independent variables gender and age group and the dependent variables related to the victimization and perpetration of dating violence, considering the impact of Ecuadorian sociocultural context. It would be valuable to examine how factors such as socioeconomic status, family functioning, and social desirability influence these dynamics, as well as to investigate potential mediators or moderators in these relationships. Additionally, future studies could employ longitudinal methodologies to understand the evolution of dating violence over time and assess the effectiveness of preventive interventions tailored to the cultural and developmental characteristics of Ecuadorian youth.

Author Contributions

Contribution to the conception and design: A.R.; Contribution to data collection: A.R., L.B.-B., H.S.-S., J.H.D. and F.J.R.-D.; Contribution to data analysis and interpretation: A.R., V.M.-M., D.R.-F. and L.B.-B.; Drafting and/or revising the article: A.R., L.B.-B., and F.J.R.-D.; Approval of the final version for publication: A.R., L.B.-B., J.H.D. and F.J.R.-D.; Obtaining authorization for the scale: J.H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financed by the Universidad Politécnica Salesiana Sede Cuenca, Ecuador.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures conducted in this study involving human participants adhered to the ethical standards established by the ethics committee. This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador (code 046-UIO-2022). This research is derived from the research project entitled “Prevalence and risk factors of dating violence among Ecuadorian adolescents and university students and evaluation of the effectiveness of psychological intervention with virtual reality in reducing anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress derived from violence”, under the direction of Dr. Andres Ramirez, PhD., with the support of the Research Group in Psychology (GIPSI-SIB) of the Salesian Polytechnic University (Universidad Politécnica Salesiana), Cuenca, Ecuador.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this research are publicly available and can be obtained by emailing the first author of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Ecuador, and especially to Juan Cárdenas Tapia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aguilera-Jiménez, N., Rodríguez-Franco, L., Rohlfs-Domínguez, P., Alameda-Bailén, J. R., & Paíno-Quesada, S. G. (2021). Relationships of adolescent and young couples with violent behaviors: Conflict resolution strategies. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(6), 3201. [CrossRef]

- Brem, M. J., Stuart, G. L., Cornelius, T. L., & Shorey, R. C. (2021). A Longitudinal Examination of Alcohol Problems and Cyber, Psychological, and Physical Dating Abuse: The Moderating Role of Emotion Dysregulation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(19-20), 10499 -10519. [CrossRef]

- Borsboom, D., Deserno, M. K., Rhemtulla, M., Epskamp, S., Fried, E. I., McNally, R. J., ... & Waldorp, L. J. (2021). Network analysis of multivariate data in psychological science. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 1(1), 58. [CrossRef]

- Carney, J. R. (2024). A Systematic Review of Barriers to Formal Supports for Women Who Have Experienced Intimate Partner Violence in Spanish-Speaking Countries in Latin America. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(1), 526-541. [CrossRef]

- Cascardi, M., & Jouriles, E. N. (2018). A Study Space Analysis and Narrative Review of Trauma-Informed Mediators of Dating Violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(3), 266-285. [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J. M., Mukunzi, J. N., Amédée, L. M., Clorméus, L. A., Dalexis, R. D., Lafontaine, M. F., ... & Hébert, M. (2022). Prevalence and factors related to dating violence victimization and perpetration among a representative sample of adolescents and young adults in Haiti. Child Abuse & Neglect, 128, 105597. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A. P., & Kenett, Y. N. (2023). Semantic network analysis (SemNA): A tutorial on preprocessing, estimating, and analyzing semantic networks. Psychological Methods, 28(4), 860–879. [CrossRef]

- Campo-Arias, A., & Caballero-Domínguez, C. C. (2021). Confirmatory factor analysis of the family APGAR questionnaire. Revista Colombiana de psiquiatria, 50(4), 234-237. [CrossRef]

- Costa, B. M., Kaestle, C. E., Walker, A., Curtis, A., Day, A., Toumbourou, J. W., & Miller, P. (2015). Longitudinal predictors of domestic violence perpetration and victimization: A systematic review. Aggression and violent behavior, 24, 261-272. [CrossRef]

- Dalmaijer, E. S., Nord, C. L., & Astle, D. E. (2022). Statistical power for cluster analysis. BMC bioinformatics, 23(1), 205. [CrossRef]

- Dardis, C. M., Dixon, K. J., Edwards, K. M., & Turchik, J. A. (2015). An Examination of the Factors Related to Dating Violence Perpetration Among Young Men and Women and Associated Theoretical Explanations: A Review of the Literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 16(2), 136-152. [CrossRef]

- Doucette, H., Collibee, C., & Rizzo, C. J. (2021). A review of parent-and family-based prevention efforts for adolescent dating violence. Aggression and violent behavior, 58, 101548. [CrossRef]

- Duval, A., Lanning, B. A., & Patterson, M. S. (2020). A Systematic Review of Dating Violence Risk Factors Among Undergraduate College Students. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(3), 567-585. [CrossRef]

- Edeby, A., & San Sebastián, M. (2021). Prevalence and sociogeographical inequalities of violence against women in Ecuador: A cross-sectional study. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 130. [CrossRef]

- Emanuels, S. K., Toews, M. L., Spencer, C. M., & Anders, K. M. (2022). Family-of-origin factors and physical teen dating violence victimization and perpetration: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 31(7), 1957-1967. [CrossRef]

- Expósito, F., Moya, M. C., & Glick, P. (1998). Sexismo ambivalente: medición y correlatos. Revista de Psicología social, 13(2), 159-169. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Fuertes, A. A., Carcedo, R. J., Orgaz, B., & Fuertes, A. (2018). Sexual Coercion Perpetration and Victimization: Gender Similarities and Differences in Adolescence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(16), 2467-2485. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A. J., Schumacher, J. A., & Coffey, S. F. (2015). Social Desirability and Partner Agreement of Men’s Reporting of Intimate Partner Violence in Substance Abuse Treatment Settings. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(4), 565-579. [CrossRef]

- Frieze, I. H., Newhill, C. E., & Fusco, R. (2020). Violence and abuse in intimate partner relationships: Battered women and their batterers. In Dynamics of family and intimate partner violence (pp. 63–83). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Guadix, M., Sorrel, M. A., & Martínez-Bacaicoa, J. (2023). Technology-facilitated sexual violence perpetration and victimization among adolescents: A network analysis. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 20(4), 1000–1012. [CrossRef]

- García-Díaz, V., Bringas, C., Fernández-Feito, A., Antuña, M. Á., Lana, A., Rodríguez-Franco, L., & Rodríguez-Díaz, F. J. (2017). Tolerance and perception of abuse in youth dating relationships. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 26(5), 462-474. [CrossRef]

- Giordano, P. C., Copp, J. E., Manning, W. D., & Longmore, M. A. (2021). Relationship Dynamics Associated With Dating Violence Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Feminist Post-Structural Analysis. Feminist Criminology, 16(3), 320-336. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, S., Sanz, J., Espinosa, R., Gesteira, C., & García-Vera, M. P. (2016). La Escala de Deseabilidad Social de Marlowe-Crowne: baremos para la población general española y desarrollo de una versión breve. Anales de Psicología, 32(1), 206-217. [CrossRef]

- Herrero, J., & Meneses, J. (2006). Short Web-based versions of the perceived stress (PSS) and Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CESD) Scales: A comparison to pencil and paper responses among Internet users. Computers in human behavior, 22(5), 830-846. [CrossRef]

- Hevey, D. (2018). Network analysis: a brief overview and tutorial. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 6(1), 301–328. [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. J., Ma, R., & McNally, R. J. (2021). Bridge centrality: a network approach to understanding comorbidity. Multivariate behavioral research, 56(2), 353-367. [CrossRef]

- Klencakova, L. E., Pentaraki, M., & McManus, C. (2023). The Impact of Intimate Partner Violence on Young Women’s Educational Well-Being: A Systematic Review of Literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(2), 1172-1187. [CrossRef]

- Kelley, E. L., Edwards, K. M., Dardis, C. M., & Gidycz, C. A. (2015). Motives for physical dating violence among college students: A gendered analysis. Psychology of Violence, 5(1), 56–65. [CrossRef]

- Lachance-Grzela, M., Liu, B., Charbonneau, A., & Bouchard, G. (2021). Ambivalent sexism and relationship adjustment among young adult couples: An actor-partner interdependence model. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(7), 2121-2140. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. L., Fiske, S. T., Glick, P., & et al. (2010). Ambivalent sexism in close relationships: (Hostile) power and (benevolent) romance shape relationship ideals. Sex Roles, 62(7–8), 583–601. [CrossRef]

- López-Barranco, P. J., Jiménez-Ruiz, I., Pérez-Martínez, M. J., Ruiz-Penin, A., & Jiménez-Barbero, J. A. (2022). Systematic review and meta-analysis of the violence in dating relationships in adolescents and young adults. Revista iberoamericana de psicologia y salud., 13(2), 73-84. [CrossRef]

- Malhi, N., Oliffe, J. L., Bungay, V., & Kelly, M. T. (2020). Male perpetration of adolescent dating violence: A scoping review. American Journal of Men’s Health, 14(5). [CrossRef]

- Marr, C., Webb, R. T., Yee, N., & Dean, K. (2024). A Systematic Review of Interpersonal Violence Perpetration and Victimization Risk Examined Within Single Study Cohorts, Including in Relation to Mental Illness. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(1), 130-149. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Maldonado, V., del Mar Pastor-Bravo, M., Vargas, E., Francisco, J., & Ruiz, I. J. (2022). Adolescent Dating Violence: Results of a Mixed Study in Quito, Ecuador. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(17-18), 15205-15230. [CrossRef]

- Michael, K., Goussinsky, R., Yassour-Borochowitz, D., Yakhnich, L., & Yanay-Ventura, G. (2023). Perpetration of violence in dating relationships among Israeli college students: gender differences, personal and interpersonal risk factors. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 32(12), 1625–1646. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Rivas, M., Ronzón-Tirado, R. C., Redondo, N., & Cassinello, M. D. Z. (2022). Adolescent Victims of Physical Dating Violence: Why Do They Stay in Abusive Relationships? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(11-12), NP10362-NP10381. [CrossRef]

- Oflaz, Ç., Toplu-Demirtaş, E., Öztemür, G., & Fincham, F. D. (2023). Feeling Guilt and Shame Upon Psychological Dating Violence Victimization in College Women: The Further Role of Sexism. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(1-2), 1990-2016. [CrossRef]

- Paat, Y.-F., & Markham, C. (2019). The Roles of Family Factors and Relationship Dynamics on Dating Violence Victimization and Perpetration Among College Men and Women in Emerging Adulthood. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(1), 81-114. [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Medina, D. M., Williams, J. R., Ravi, K., Ombayo, B., & Black, B. M. (2022). Teen Dating Violence Help-Seeking Intentions and Behaviors Among Ethnically and Racially Diverse Youth: A Systematic Review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(4), 1063-1078. [CrossRef]

- Park, S., & Kim, S. H. (2018). The power of family and community factors in predicting dating violence: A meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 40, 19-28. [CrossRef]

- Piolanti, A., & Foran, H. M. (2022). Efficacy of interventions to prevent physical and sexual dating violence among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(2), 142–149. [CrossRef]

- Puente-Martínez, A., Reyes-Sosa, H., Ubillos-Landa, S., & et al. (2023). Social support seeking among women victims of intimate partner violence: A qualitative analysis of lived experiences. Journal of Family Violence. [CrossRef]

- Puffer, E. S., Friis Healy, E., Green, E. P., M. Giusto, A., N. Kaiser, B., Patel, P., & Ayuku, D. (2020). Family functioning and mental health changes following a family therapy intervention in Kenya: A pilot trial. Journal of child and family studies, 29(12), 3493-3508. [CrossRef]

- Machado, A., Sousa, C., & Cunha, O. (2024). Bidirectional Violence in Intimate Relationships: A Systematic Review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(2), 1680-1694. [CrossRef]

- Mantzaris, A. V., Walker, T. G., Taylor, C. E., & Ehling, D. (2019). Adaptive network diagram constructions for representing big data event streams on monitoring dashboards. Journal of Big Data, 6, 24. [CrossRef]

- McMillan, I. F., Schroeder, G. E., Mooney, J. T., & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. (2023). Gender Issues in Intimate Partner and Family Violence Research. In Violence in Families: Integrating Research into Practice (pp. 63-81). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- McNaughton Reyes, H. L., Graham, L. M., Chen, M. S., Baron, D., Gibbs, A., Groves, A. K., ... & Maman, S. (2021). Adolescent dating violence prevention programmes: a global systematic review of evaluation studies. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 5(3), 223-232. [CrossRef]

- Minto, K., Masser, B., & Louis, W. (2022). Lay Understandings of the Structure of Intimate Partner Violence in Relationships: An Analysis of Behavioral Clustering Patterns. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(13-14), NP10810-NP10831. [CrossRef]

- Murta, S. G., Parada, P. D. O., da Silva Meneses, S., Medeiros, J. V. V., Balbino, A., Rodrigues, M. C., ... & de Vries, H. (2020). Dating SOS: a systematic and theory-based development of a web-based tailored intervention to prevent dating violence among Brazilian youth. BMC public health, 20, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Portugal, A., Caridade, S., Santos, A. S., Spínola, J., & Sani, A. (2023). Dating Conflict-Resolution Tactics and Exposure to Family Violence: University Students’ Experiences. Social Sciences, 12(4), 209. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, A., Medina-Maldonado, V., Burgos-Benavides, L., Alfaro-Urquiola, A. L., Sinchi, H., Herrero Díez, J., & Rodríguez-Diaz, F. J. (2024). Validation of the Psychometric Properties of the Conflict Resolution Styles Inventory in the University Population. Social Sciences, 13(11), 615. [CrossRef]

- Robinaugh, D. J., Millner, A. J., & McNally, R. J. (2016). Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(6), 747–757. [CrossRef]

- Rocco, C. M., Barker, K., Moronta, J., & et al. (2024). A psychological network analysis of the relationship among component importance measures. Applied Network Science, 9(20). [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Díaz, F. J., Herrero, J., Rodríguez-Franco, L., Bringas-Molleda, C., Paíno-Quesada, S. G., & Pérez, B. (2017). Validation of dating violence questionnarie-R (DVQ-R). International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 17(1), 77-84. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Franco, L., Juarros-Basterretxea, J., Paíno-Quesada, S., Herrero, J., & Rodríguez-Díaz, F. (2022). Dating Violence Questionnaire for Victimization and Perpetration (DVQ-VP): An interdependence analysis of self-reports. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 22(1), 100276. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Jiménez, V., Muñoz-Fernández, N., & Ortega-Rivera, J. (2018). Efficacy evaluation of" Dat-e Adolescence": A dating violence prevention program in Spain. PLoS One, 13(10), e0205802. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Zafra, M., Gómez-López, M., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Viejo, C. (2024). The association between dating violence victimization and the well-being of young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology of Violence, 14(3), 158–173. [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A., & Iyengar, S. (2020). Centrality measures in complex networks: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.07190. [CrossRef]

- Sianko, N., Meçe, M. H., & Abazi-Morina, L. (2020). Family functioning among rural teens and caregivers: interactive influence on teen dating violence. Family process, 59(3), 1175-1190. [CrossRef]

- Smilkstein, G. (1978). The Family APGAR: A proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. Journal of Family Practice, 6(6), 1231–1239.

- Southern, S., & Sullivan, R. D. (2021). Family Violence in Context: An Intergenerational Systemic Model. The Family Journal, 29(3), 260-291. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, T. P., Chiaramonte, D., Clark, D. A., & Swan, S. C. (2023). Intimate Partner Violence Fear–11 Scale: An item response analysis. Psychology of Violence, 13(2), 161–170. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. A., & Sullivan, T. N. (2021). Bidirectional Relations Between Dating Violence Victimization and Substance Use in a Diverse Sample of Early Adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(1-2), 862-891. [CrossRef]

- Terrazas-Carrillo, E., Sabina, C., Vásquez, D. A., & Garcia, E. (2024). Cultural Correlates of Dating Violence in a Combined Gender Group of Latino College Students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 39(3-4), 785-810. [CrossRef]

- Théorêt, V., Hébert, M., Fernet, M., & Blais, M. (2021). Gender-specific patterns of teen dating violence in heterosexual relationships and their associations with attachment insecurities and emotion dysregulation. Journal of youth and adolescence, 50(2), 246-259. [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, P., & Schuster, I. (2021). Prevalence of teen dating violence in Europe: A systematic review of studies since 2010. New directions for child and adolescent development, 2021(178), 11-37. [CrossRef]

- Valdivia-Salas, S., Lombas, A. S., Jiménez, T. I., Lucas-Alba, A., & Villanueva-Blasco, V. J. (2023). Profiles and Risk Factors for Teen Dating Violence in Spain. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(3-4), 4267-4292. [CrossRef]

- Wong, J. S., Bouchard, J., & Lee, C. (2023). The Effectiveness of College Dating Violence Prevention Programs: A Meta-Analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(2), 684-701. [CrossRef]

- Young, H., Long, S. J., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Kim, H. S., Hewitt, G., Murphy, S., & Moore, G. F. (2021). Dating and relationship violence victimization and perpetration among 11–16 year olds in Wales: a cross-sectional analysis of the School Health Research Network (SHRN) survey. Journal of Public Health, 43(1), 111-122. [CrossRef]

- Zavala, E., & Kurtz, D. L. (2021). Applying Differential Coercion and Social Support Theory to Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(1-2), 162-187. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Networks, Centrality Plot, and Clustering Plot of the General Model (n = 836). Note: C1 = Age, C2 = Socioeconomic level, C3 = Fear, C4 = Trapped, C5 = Maltreated, C6 = Hostile, C7 = Benevolent, C8 = Reasons, C9 = Stress, C10 = Family Functioning, C11 = Social Desirability, C12 = Coercion (Victimization), C13 = Humiliation (Victimization), C14 = Detachment (Victimization), C15 = Sexual (Victimization), C16 = Physical (Victimization), C17 = Coercion (Perpetration), C18 = Humiliation (Perpetration), C19 = Detachment (Perpetration), C20 = Sexual (Perpetration), C21 = Physical (Perpetration).

Figure 1.

Networks, Centrality Plot, and Clustering Plot of the General Model (n = 836). Note: C1 = Age, C2 = Socioeconomic level, C3 = Fear, C4 = Trapped, C5 = Maltreated, C6 = Hostile, C7 = Benevolent, C8 = Reasons, C9 = Stress, C10 = Family Functioning, C11 = Social Desirability, C12 = Coercion (Victimization), C13 = Humiliation (Victimization), C14 = Detachment (Victimization), C15 = Sexual (Victimization), C16 = Physical (Victimization), C17 = Coercion (Perpetration), C18 = Humiliation (Perpetration), C19 = Detachment (Perpetration), C20 = Sexual (Perpetration), C21 = Physical (Perpetration).

Figure 2.

Networks, Centrality Plot, and Clustering of the model as a function of gender. Note: C1 = Age, C2 = Socioeconomic level, C3 = Fear, C4 = Trapped, C5 = Maltreated, C6 = Hostile, C7 = Benevolent, C8 = Reasons, C9 = Stress, C10 = Family Functioning, C11 = Social Desirability, C12 = Coercion (Victimization), C13 = Humiliation (Victimization), C14 = Detachment (Victimization), C15 = Sexual (Victimization), C16 = Physical (Victimization), C17 = Coercion (Perpetration), C18 = Humiliation (Perpetration), C19 = Detachment (Perpetration), C20 = Sexual (Perpetration), C21 = Physical (Perpetration).

Figure 2.

Networks, Centrality Plot, and Clustering of the model as a function of gender. Note: C1 = Age, C2 = Socioeconomic level, C3 = Fear, C4 = Trapped, C5 = Maltreated, C6 = Hostile, C7 = Benevolent, C8 = Reasons, C9 = Stress, C10 = Family Functioning, C11 = Social Desirability, C12 = Coercion (Victimization), C13 = Humiliation (Victimization), C14 = Detachment (Victimization), C15 = Sexual (Victimization), C16 = Physical (Victimization), C17 = Coercion (Perpetration), C18 = Humiliation (Perpetration), C19 = Detachment (Perpetration), C20 = Sexual (Perpetration), C21 = Physical (Perpetration).

Figure 3.

Networks, Centrality Plot, and Clustering of the model as a function of age group. Note: C1 = Age, C2 = Socioeconomic level, C3 = Fear, C4 = Trapped, C5 = Maltreated, C6 = Hostile, C7 = Benevolent, C8 = Reasons, C9 = Stress, C10 = Family Functioning, C11 = Social Desirability, C12 = Coercion (Victimization), C13 = Humiliation (Victimization), C14 = Detachment (Victimization), C15 = Sexual (Victimization), C16 = Physical (Victimization), C17 = Coercion (Perpetration), C18 = Humiliation (Perpetration), C19 = Detachment (Perpetration), C20 = Sexual (Perpetration), C21 = Physical (Perpetration).

Figure 3.

Networks, Centrality Plot, and Clustering of the model as a function of age group. Note: C1 = Age, C2 = Socioeconomic level, C3 = Fear, C4 = Trapped, C5 = Maltreated, C6 = Hostile, C7 = Benevolent, C8 = Reasons, C9 = Stress, C10 = Family Functioning, C11 = Social Desirability, C12 = Coercion (Victimization), C13 = Humiliation (Victimization), C14 = Detachment (Victimization), C15 = Sexual (Victimization), C16 = Physical (Victimization), C17 = Coercion (Perpetration), C18 = Humiliation (Perpetration), C19 = Detachment (Perpetration), C20 = Sexual (Perpetration), C21 = Physical (Perpetration).

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of the study variables (n = 836).

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of the study variables (n = 836).

| Abbrev |

Variable |

Mean |

SD |

W |

|

Min |

Max |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

| C1 |

Age |

20.78 |

2.648 |

0.975 |

* |

14 |

26 |

19 |

21 |

23 |

| C2 |

Socioeconomic level |

2.95 |

0.652 |

0.777 |

* |

1 |

5 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| C3 |

Fear |

1.801 |

0.399 |

0.488 |

* |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| C4 |

Trapped |

1.79 |

0.407 |

0.5 |

* |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| C5 |

Maltreated |

1.882 |

0.323 |

0.376 |

* |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| C6 |

Hostile |

20.01 |

13.647 |

0.964 |

* |

0 |

55 |

8 |

19 |

30 |

| C7 |

Benevolent |

18.97 |

12.388 |

0.965 |

* |

0 |

54 |

9 |

18 |

27 |

| C8 |

Reasons |

5.828 |

5.496 |

0.849 |

* |

0 |

38 |

2 |

4 |

8 |

| C9 |

Stress |

8.623 |

2.523 |

0.935 |

* |

0 |

16 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

| C10 |

Family Functioning |

13.01 |

5.204 |

0.947 |

* |

0 |

20 |

10 |

13 |

18 |

| C11 |

Social Desirability |

17.48 |

4.916 |

0.994 |

* |

3 |

32 |

14 |

17 |

21 |

| C12 |

Coerción (Victimization) |

1.449 |

1.834 |

0.743 |

* |

0 |

16 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

| C13 |

Humiliation (Victimization) |

0.751 |

1.247 |

0.608 |

* |

0 |

16 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| C14 |

Detachment (Victimization) |

1.888 |

1.954 |

0.839 |

* |

0 |

16 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

| C15 |

Sexual (Victimization) |

0.343 |

1.043 |

0.363 |

* |

0 |

16 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| C16 |

Physical (Victimization) |

0.38 |

1.119 |

0.369 |

* |

0 |

16 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| C17 |

Coerción (Perpetration) |

0.592 |

1.413 |

0.476 |

* |

0 |

16 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| C18 |

Humiliation (Perpetration) |

0.766 |

1.201 |

0.651 |

* |

0 |

13 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| C19 |

Detachment (Perpetration) |

1.432 |

1.969 |

0.723 |

* |

0 |

16 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

| C20 |

Sexual (Perpetration) |

0.762 |

1.493 |

0.555 |

* |

0 |

16 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| C21 |

Physical (Perpetration) |

1.476 |

1.822 |

0.772 |

* |

0 |

16 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).