1. Introduction

Climate extremes, diminishing soil health, and increasing global population impose a greater need to maximize crop productivity and quality. Adjuvants that aid in delivery and utilization of nutrients provide an alternative to the traditional approach of increasing yield through increased fertilizer and pesticide use. Pluronics (also known as Poloxamers or Kolliphors) are non-ionic, ethoxylated triblock copolymers demonstrating adjuvant functionality [

1]. These polymers are used in foods, cosmetics, and biotechnology, and exhibit unique membrane-protective / membrane-healing activity as reviewed by Kwiatkowski et al. [

2]. Pluronic F68 (Poloxamer P188 or Kolliphor® P188) binds to and inserts into lipid bilayers, protecting cells from shear damage in suspended cell culture and limiting electrolyte leakage in damaged membranes [

3,

4,

5]. Pluronics are generally recognized as safe (GRAS) and the excipient and membrane-active functions of F68 are FDA-approved (FDA inactive ingredient database search “Poloxamer 188” accessed 5/2025). For instance, in trials with humans, pain improvement in sickle-cell anemia is attributed to F68 coating of red blood cells [

6,

7].

Demonstrated lipid bilayer protection and membrane repair from F68 may translate into agriculture to protect drought-stressed plant cells where membrane integrity is compromised [

8,

9,

10,

11]. F68 also exhibits a metal binding capacity that potentially shields F68-coated cells from toxic ion concentrations while retaining the metals for later utilization [

12]; thus, F68 could be of value in the rhizosphere as a reservoir for essential elements.

Plant health depends on the cooperation of the plant with both epiphytic and endophytic microbes, which constitute the plant’s microbiome. One of the many roles of the microbiome is to confer protection to the host from drought and pathogen stresses [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Thus, if F68 is to be used as an agricultural adjuvant, it must not have deleterious effects on the plant or its microbiome. F68 shows no adverse effects on a probiotic epiphyte wheat root colonizer,

Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6 (

PcO6), which does not utililze the ethoxylated polymer as a carbon source in planktonic growth experiments [

17]. Investigations of F68 in plant cell culture and agriculture are limited. We have previously reported F68 treated wheat under non-stressed conditions exhibit increased shoot mass [

18], possibly due to improved nutrient utilization as suggested by Kok et al., for F68-treated rice [

19,

20].

Here, adjuvant applications of F68 were examined in drought stressed wheat. F68 seed priming was performed to assess concentration dependent effects on germination and plant emergence. Rhizosphere delivery of F68 in PcO6 colonized wheat grown to 28 days was examined for potential amelioration of drought stress, utilizing evapotranspiration, photosynthetic output, and end of study dry weight yield as metrics. The fate and transport of fluorescently labeled F68 in the rhizoplane, including interactions with an endophytic Bacillus spp. were monitored to assess F68 membrane affinity, microbiome interactions, and mobility in plant cells. F68 biological activity in watered and droughted plants was manifest as an increase in evapotranspiration and shoot dry mass compared to untreated controls or plants receiving the osmolyte glycine betaine (GB), utilized here as a know plant protective compound. A neutral effect of F68 (and GB) was observed during plant drought recovery, suggesting that application timing and doses need to be further tuned to benefit plants under abiotic stress. The absence of detrimental effects in plants or associated bacteria under the study conditions support ongoing investigation of F68 as an agricultural adjuvant to improve nutrient utilization and potentially repair / protect plant cell membranes damaged during abiotic stress.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. F68 Properties

Pluronic F68, purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, MO. USA, consists of a hydrophobic polypropylene oxide (PPO) chain flanked by hydrophilic polyethylene oxide (PEO) chains with structure HO-[PEO]76-[PPO]29-[PEO]76-OH. The high hydrophilic : lipophilic balance (HLB) value of 29 reduces the driving force for F68 micellization. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) (DynaPro Nanostar, Wyatt Technology, Santa Barabara, USA) was used to measure the hydrodynamic radius of F68 unimers, micelles, and larger aggregates of 1 mM (8.4 g/L) F68 at 25 °C. F68 self-assembly and effect on water surface tension was assessed with a wire probe tensiometer (Kibron Inc, Helsinki, Finland) using a range of F68 concentrations between 0 and 10 mg/L at 25 °C in double distilled water (ddH2O). For DLS 10 acquisitions per measurement with three separate measurements conducted. Three surface tension acquisitions were made per F68 concentration.

2.2. Effect of F68 on Seed Water Uptake, Germination, Emergence, and Endophytes

F68-treated seed water uptake, germination on Lysogeny Broth (LB) 2% agar plates, and emergence in wetted and fluffed sand was examined using seeds surface sterilized with 10% hydrogen peroxide (100 mL in a 250 mL beaker containing about 100 seeds) shaken at 120 RPM for 10 min followed by extensive washing in sterile double distilled water. The seeds (five seeds per treatment with four replications) were treated with defined doses of F68 (0, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, 250 mg/mL) with 12 h immersion at room temperature before being transferred to LB agar plates or planting at 5 mm depths in wetted and fluffed quartz sand [

18,

21]. Germination was noted as positive for seeds where the root grew to be as long as the seed by 48 h after transfer. Emergence of endophytic microbes around the germinating seeds was noted after 4 d incubation at room temperature under ambient lighting.

2.3. Assessment of Drought Stress Responses in F68, GB, and F68+GB Wheat Seedlings

Adjuvants effects on wheat drought stress responses were tested in seedlings grown for 14 d under sufficient watering followed by 7 d of water witholding followed by 7 d rehydration. Exogenous glycine betaine (GB) was examined in parallel to F68 as this osmolyte is produced by plants in response to abiotic stress such as drought. Plants were grown from surface-sterilized seeds inoculated with PcO6 by immersion in a suspension of 104 colony-forming units [CFU]/ml for 5 min and blotted dry before planting in sterile quartz sand wetted with half strength Hoaglands solution and fluffed with a sterile metal fork to create pore space in this growth matrixß. The sand was previously washed with reverse osmosis, sieved to remove particles below 125 µm and dried at 200 °C.

Nine seeds were planted per pot with six pots per treatment; the sand (300 g) had been wetted with 150 mL half-strength Hoaglands solution to provide complete mineral nutrition required for optimal plant health [

18]. Glycine betaine (GB) (Sigma Aldrich) was investigated as a small molecule osmolyte with known benefit to plants under abiotic stress [

22]. At day 14 prior to onset of drought four treatments were applied: 1) Hoaglands solution, 2) Hoaglands + F68 (8.9 mg/L = 1.7 mg F68 per kg sand), 3) Hoaglands + GB (61.3 mg/L = 11.5 mg GB per kg sand), 4) Hoaglands with F68 + GB. The concentrations were selected as correlating with field applications. An additional six pots that were not planted were treated with the same watering schedules to measure the loss of water due to evaporation only from the sand. White LED light 30 cm above the base of the botswere set to a 16 h on / 8 h off cycle, providing a photon flux of ~650 μmol/m2/s and corresponding temperature of 25 °C at maximum shoot height at 22 d. Fans provided continous air circulation, and pot locations below the lamps were randomized daily.

For the first 14 d, water was added daily to maintain the mass of each pot at 135 g above dry mass per pot. At day 14, the watering contained a second treatment of F68, GB or GB+F68 at the same doses as above /kg sand. However, to provide drought stress, the daily water at 14 d was reduced to 20 g above the dry mass for half of the pots for each treatment. After 8 d of reduced watering, the 22 d-stressed seedlings were rehydrated for 6 d by adding water daily to 135 g above dry mass per pot. Seedlings from both continuously watered growth and drought stress growth were harvested at 28 d. The masses obtained daily for each pot enabled the calculation of water loss/pot due to evaporation from the sand plus loss due to plant transpiration.

Photosynthetic competency in the seedling leaves was examined starting at 14 d by examining three leaves from each pot using a LI-COR LI-6800 portable photosynthesis instrument (LI-COR Biosciences) to measure quantum yield (ΦPsII ) and photosynthetic efficiency (Fv/Fm); instrument operating conditions are provided in

Table S1. Leaves used to measure ΦPsII had at least 2 h of light before sampling. Leaves used to assess Fv/Fm had been without light for 8 h. These measurements were made every two days from 14 d until the day before the final harvest at 28 d.

To determine growth effects of the treatments, the leaves of the 28 d-old seedlings were cut above the coleoptiles and oven-dried at 60 °C for 48 h before weighing to determine tissue dry mass. To establish that neither the F68/GB treatments nor the drought period had eliminated

PcO6-root surface colonization, excised root tip sections from seedlings from each treatment were transferred to LB 2% agar. The growth of orange-colored bacterial cells from the surface of the root was indicative of colonization by

PcO6 [

18].

2.4. Fluorescent F68 (fF68)

Bacterial and plant cells were treated with a 0.1 mM solution of F68 (0.84 mg/L) containing 5 mol% fluorescein-labelled F68 (fF68). The fluorescein-labelled F68 (fF68) was prepared and handled according to the method of Kjar et al. [

23].

2.4.1. Interaction of fF68 with Root Epidermal Cells and Root-Epiphytic Bacteria

The effects of fF68 on root cells and root-epiphytic bacteria were examined using roots of germinated, surface-sterilized seeds grown for 7 d on LB 2% agar to confirm absence of any seed coat epiphytes after the surface sterilization. Roots were immersed in fF68 for 3 h, rinsed in sterile water, then transfered to a glass slide, and sealed with a cover-glass. The root cells and bacteria in these samples were imaged immediately with a Nikon Eclipse TE2000 epifluorescence microscope using a 10 MPixel camera. Time-lapse events for single epidermal root cells were captured with 10x, 40x, and 100x (NA 1.4) objective lenses and with camera integration times of 1 or 5 sec.

2.4.2. Effect of F68 on JunSE1L : Fluorescent Labelling and Planktonic Growth

Bacterial colonies growing from the spermosphere of surface-sterilized wheat seeds as they germinated on LB 2% agar were purified and a single isolate was selected to be studied for this paper. This sporulating, Gram-positive isolate, termed JunSE1L, was in the Bacillus genus, based on several characteristics including the Gram-positive staining of vegetative cells and sporulation (Wankhade et al. unpublished). The JunSE1L cells were grown for 18 h on LB and collected by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 min. After washing and suspension in sterile distilled water, the cells were treated with fF68 (0.1 mM F68 + 5 mol% fF68) for 3 h. Cells were examined for fluorescence with and without two washes in sterile water using the instrumentation described in 2.4.1.

To determine the sensitivity of JunSE1L to F68, the bacterial cells were cultured in a minimal medium broth [

18] until the late-log phase. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 min and washed twice with sterile distilled water before suspension to OD 600

nm = 0.5 (10⁷ CFU/ml). This inoculum (100 µl) was added to 100 mL minimal medium broth, without amendment or with additions of 5 or 10 g/L F68. Three cultures for each treatment were incubated at 24 °C with rotary shaking at 140 rpm and the OD

600nm was measured at defined times of growth up to 55 h to reveal growth as changes in optical density. The study was repeated twice.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

The software SAS on Demand for Academics for MS Windows was used for analysis by ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD. The data for photosynthetic function measured with the LI-COR instrument involved a restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method along with ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD when a significance of p < 0.05, was revealed.

3. Results

3.1. F68 Characterization: Size and Surface Activity

DLS of 8.4 g/L F68 in water at 25 °C revealed ~5.4 nm diameter unimers and a range of larger sub-100 nm micelles and aggregates (Supplemental

Figure S1), confirming the presence of nanosized F68 particles. F68 surface tension measurements in water at 25 °C (Supplemental

Figure S2) revealed a sharp decrease from 72 mN/m for pure water to 55 mN/m at 0.01 g/L F68. For concentrations between 0.01 g/L to 10 g/L the surface tension decreased more gradually to 45 mN/m, but never transitioned to a lower surface tension plateau indicative of a critical micelle concentration (CMC). Using dye solubilization methods, Alexandridis et al. were likewise unable to determine a CMC for F68 below 40 °C [

24], while Nakashima et al. reported a CMC of 100 g/L at 20 °C and 5 g/L at 50 °C [

25].

3.2. F68 Effects on Seed Water Uptake, Germination, Emergence, and Endophytes

There was no effect of F68 at doses of 10 g/L and below on seed water uptake and germination; however, at 100 and 250 g/L water uptake and germination declined (

Table 1), attributed to an osmotic imbalance between seed and F68 solution. Shoot emergence was not impeded by F68 seed priming for any of the investigated concentrations (

Table 1). For all F68 seed priming levels endophyte emerged and grew as white, wrinkled colonies on LB 2% agar, consistent with

Bacillus spp. (Supplemental

Figure S3).

3.3. F68 Influence on Growth of PcO6 - Inoculated Wheat Seedlings Under Drought Stress

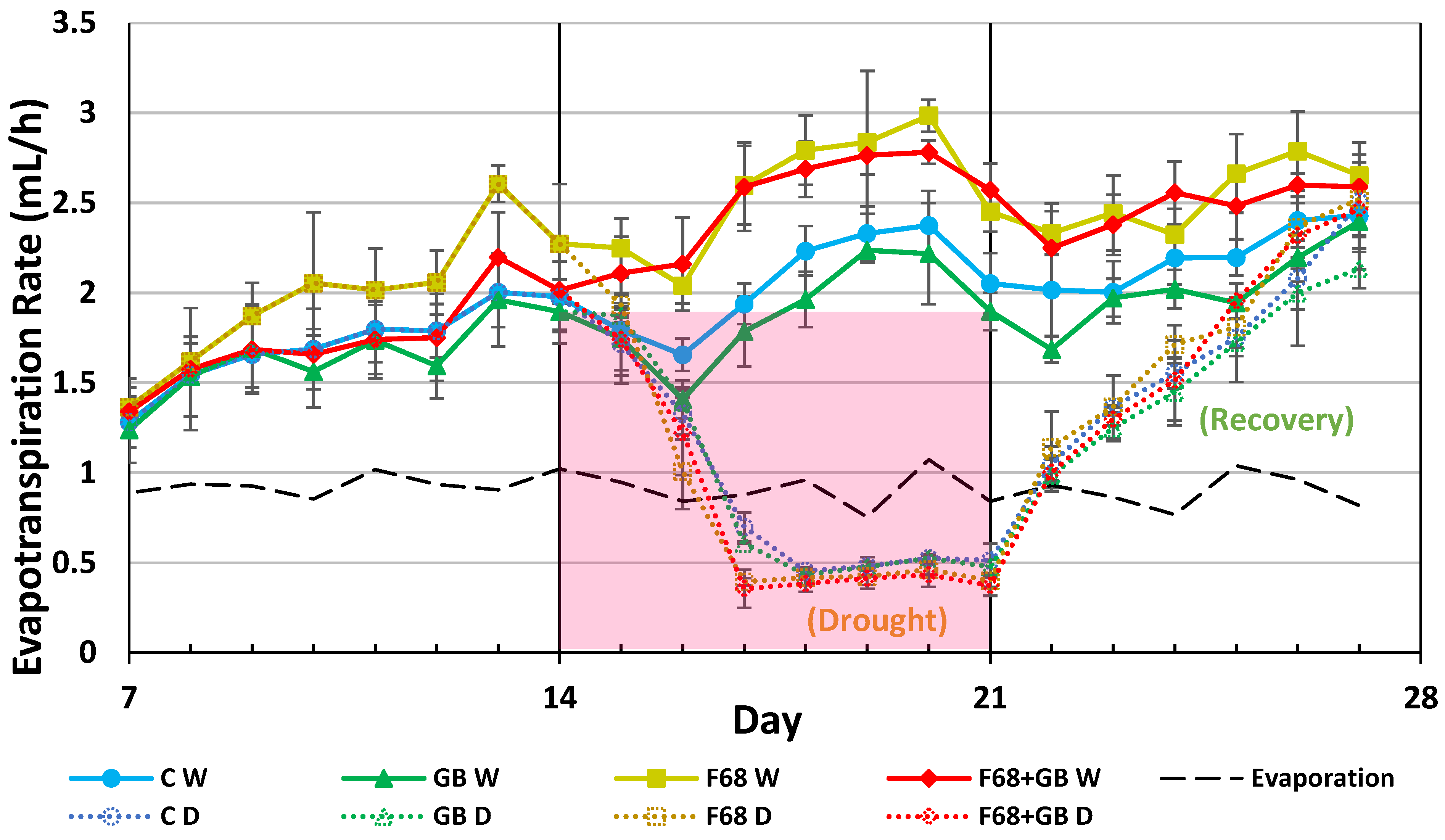

Evapotranspiration (ET) trends for F68, GB, and F68+GB treated wheat during the 28 d growth period, with half the pots from each treatment droughted from days 14 to 21, then rehydrated from days 22 to 27 are shown in

Figure 1. Also shown are the evaporation rates in plant-free growth pots (dotted black line), which remain relatively steady at ~1 mL/h throughout the study, indicating that factors directly influencing ET such as temperature, convective air currents, and RH, which were not tightly controlled, were either constant, or variations had a net neutral effect on evaporation.

During the initial 14 day full watering period the ET values for all treatments increased steadily and were statistically indistinguishable up to day 9, when the F68 treated plants exhibited statistically higher (>20%) ET than other treatments and untreated controls. At day 16 the F68+GB treated plants caught up to the ET rates of the F68 only treated plants. The ET rates for these two treatments remained statistically higher than all other treatments until day 23. GB treatments alone did not increase ET in the continously watered cohort, but the primary benefit of this osmolyte is anticipated during abiotic stress, which was initiated at day 14 in half the plants. During the droughting (days 15 – 21) and recovery (days 22 – 27) stages of the experiment ET values were statistically similar across all droughted plants receiving F68, GB, and F68+GB treatments and untreated droughted controls. Indeed, by day 27 all droughted plants across all treatments recovered with ET rates converging on the watered controls that never experienced drought.

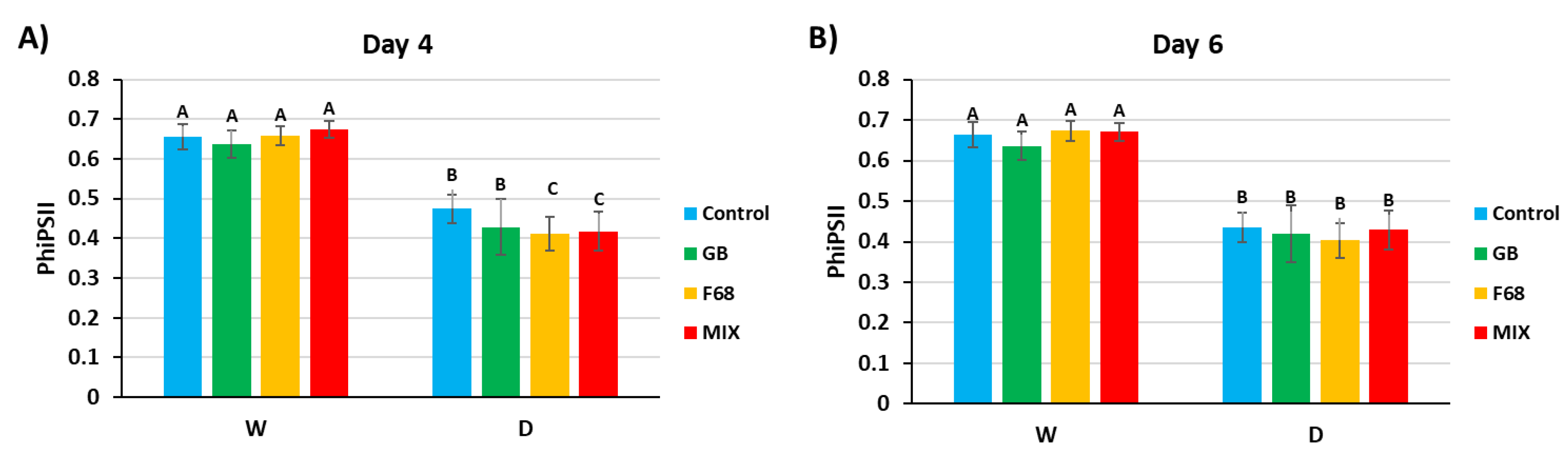

Measurement of the quantum yield for photosystem II (ΦPsII) (

Figure 2) showed reduced function by 4 d of drought stress that further decreased by 6 d of drought, with no observable benefits from any of the treatments in maintaining photosynthetic activity above untreated droughted controls. Rehydration returned values for all drought-stresed plants to those of the continuously watered plants (not shown), illustrating strong recovery in the photosynthetic function in 27 d seedlings. Fv/Fm (Supplemental

Figure S4) demonstrated a similar pattern across all treatments and controls of decreased photosynthetic efficiency with drought followed by recovery on rehydration.

At harvest, all the roots showed surface colonization by

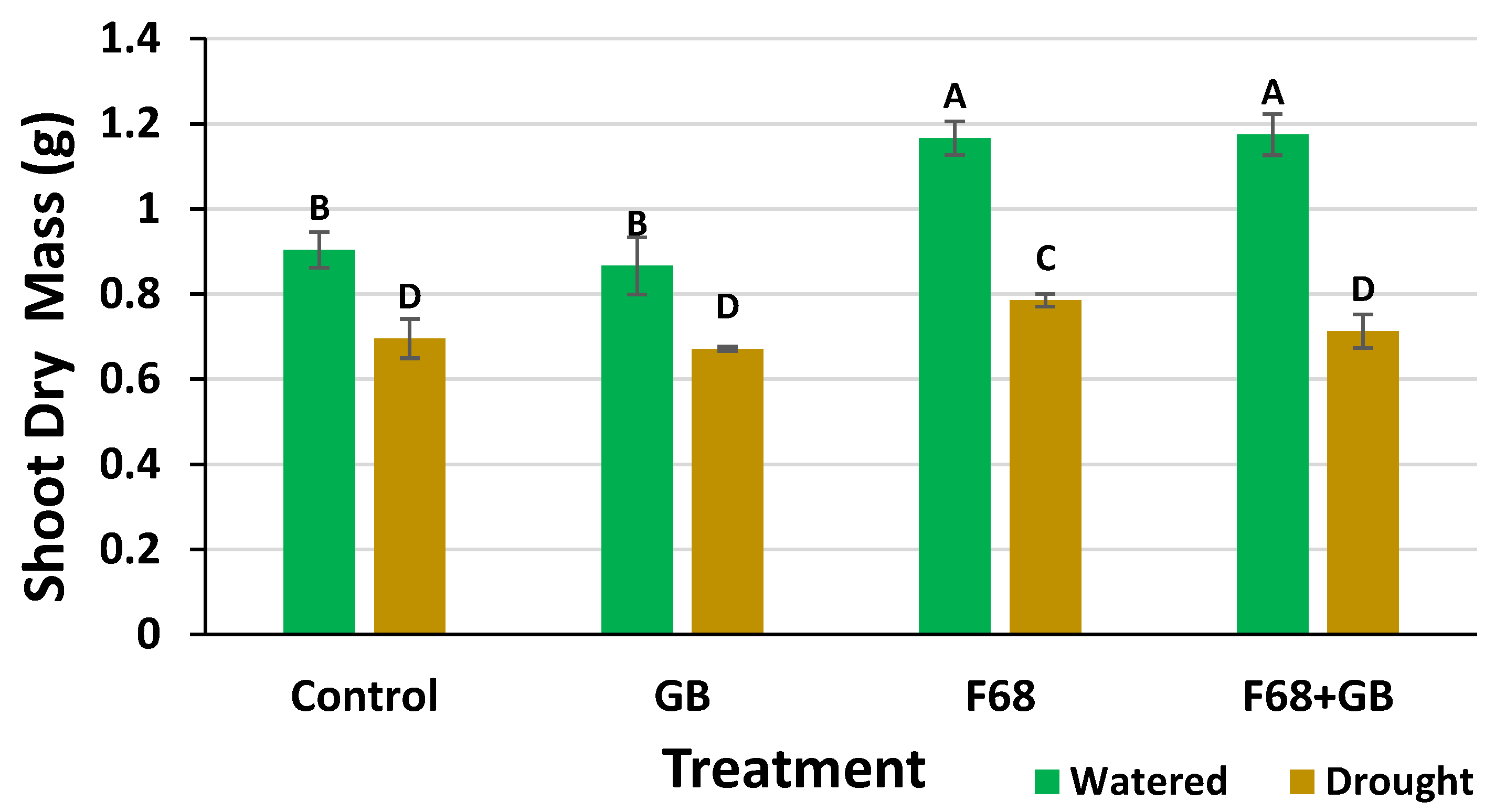

PcO6 upon transfer to LB agar (not shown), indicating survival of this bacterium as a colonist through a drought-stress period and exposure to F68 and GB. Shoot dry mass measurements (

Figure 3) show two clear trends: First, drought stress significantly reduced shoot mass compared to watered controls across all treatments, aligned with the ΦPsII watered vs. droughted data in

Figure 2; second, the continuously watered plants receiving F68 and F68+GB treatments had significantly higher dry mass than untreated and GB treated watered controls. Thus, exogenously applied GB did not provide any benefit to continuously watered or droughted plants, also suggesting the increased dry mass for F68+GB plants is due solely to F68. These shoot dry mass trends match the increased ET rates for F68 and F68+GB treated plants (

Figure 1).

3.3.1. Root Epidermal Cell and Released Endophyte Labelling with fF68

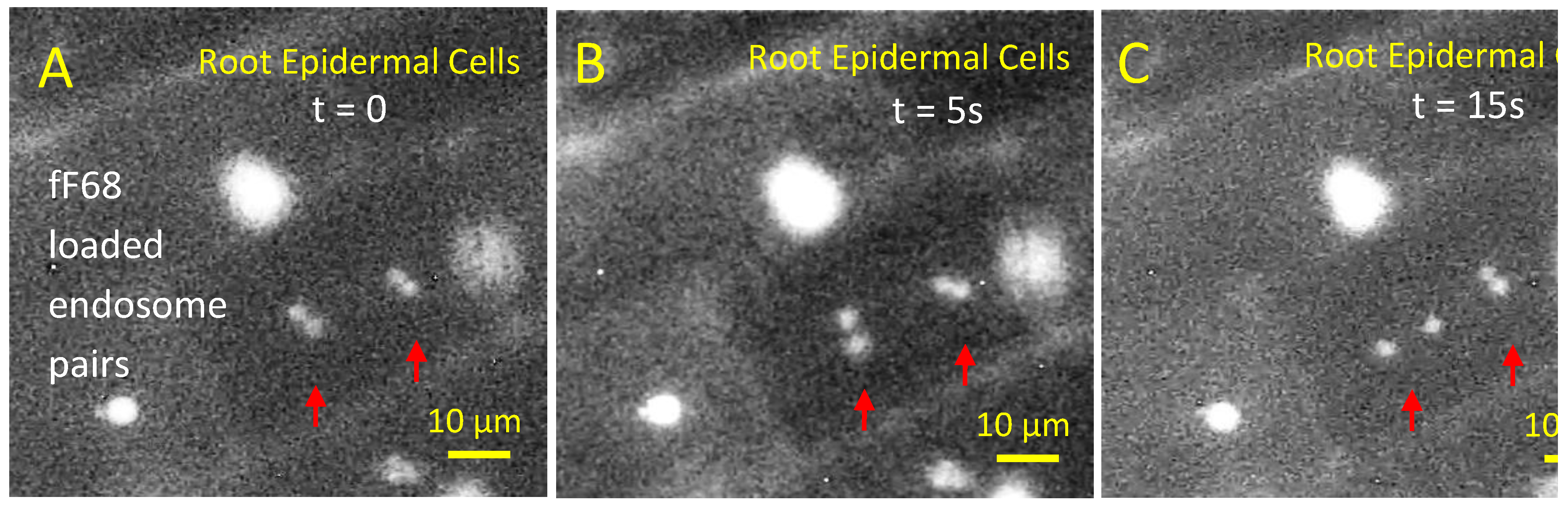

We have previously observed that wheat roots treated with fF68 and washed with water resulted in the fluorescent labelling of root hairs and some organelles. Here, after 3 h-exposure of 7 d-old wheat seedling roots to fF68, labeling of highly mobile intracellular endosomes within root epidermal cells was observed. (

Figure 4A–C). This concentration of F68 in endosomes provides mechanistic insight into the uptake and transport of Pluronics in plant tissues. During the observation period the “dancing endosomes” remained confined to a given cell, thus potential transport of F68 to the vasculature and shoot tissues may occur through apoplastic movement.

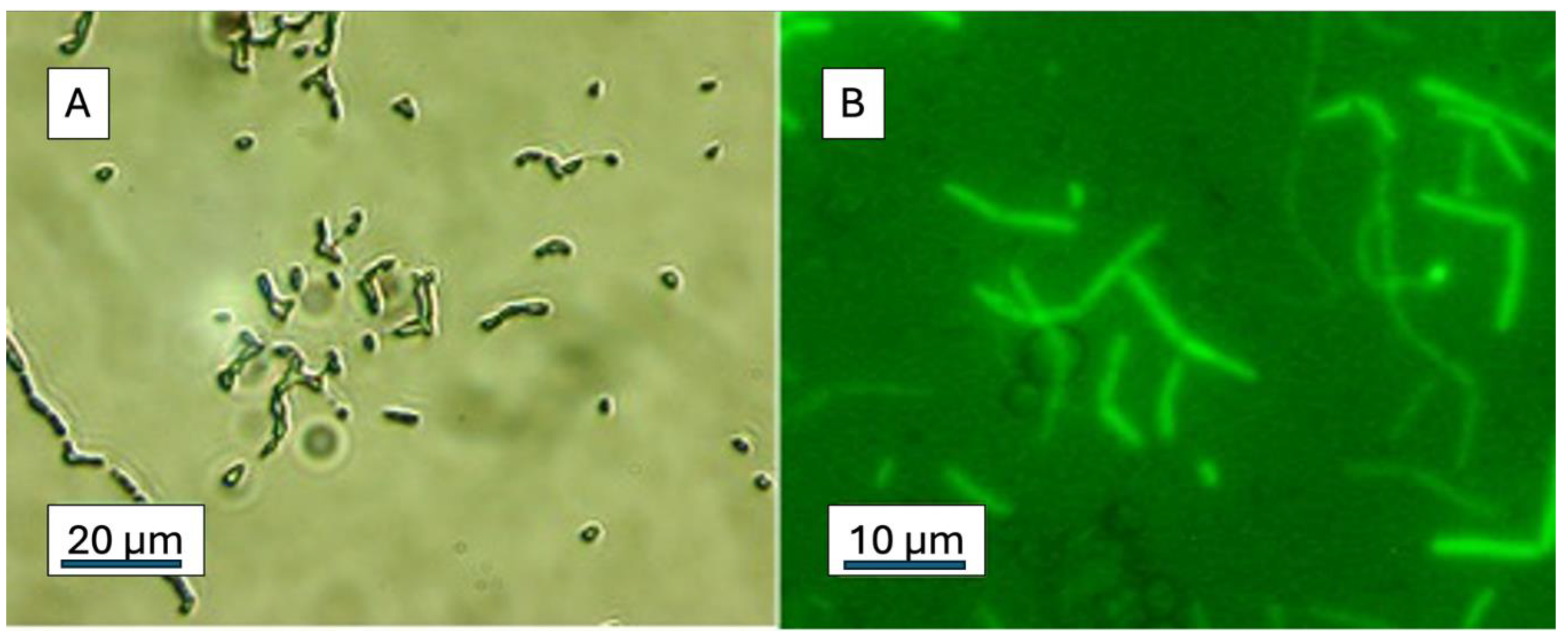

When water washes from the roots of 7 d-old seedlings grown from surface-sterilized seeds were treated with fF68 for 3 h and examined using a fluorescent microscope, fluorescently-labelled bacterial cells (presumably endophytes) were observed (

Figure 5). Some of these bacterial cells were paired or were connected in chains (

Figure 5A) and others had branched “V” and “Y”-shaped structures (

Figure 5B). Diploid, linear chained, and branched supramolecular structures have been observed for

Bacillus subtills cells under different stresses [

26].

3.3.2. The Response of Isolate JunSE1L to fF68

The spermosphere microbes, growing on LB agar as a white mass around the germinating wheat seeds, as shown in the Supplemental Material

Figure S3, were streaked on LB agar to obtain single colonies. One of the purified isolates, termed JunSE1L, had characteristics consistent with the isolate being within the genus

Bacillus (Wankhade et al., unpublished). Cells of JunSE1L when grown planktonically in LB for 18 h and then exposed to fF68, were fluorescently labelled (Figure. 6A) with the fluorescence being stable to washing with water (

Figure 6B). No fluorescence was observed for untreated JunSE1L cells or for cells treated with unlabelled F68 (images not shown). Some of these cells also had Y-shaped structures similar to those observed when cells associated with the surface of young seedling roots were examined (

Figure 5). The planktonic growth rate of JunSE1L in MM was not affected significantly by amendment with 5 g/L F68 as shown by the changes in OD

600 nm from 24, 32, 48, and 55 h in shake culture (Supplemental

Figure S5). At a higher dose, 10 g/L, a significant decrease in OD

600nm was observed early in growth but at stationary phase there was no significant decrease (p = 0.05). No spores were observed at any of these growth times either with or without treatment with F68. Thus, the cause for the lower optical density stationary phase cells does not relate to enhanced sporulation.

4. Discussion

From the water – drought – rehydrate cycle imposed on wheat over 28 d there is no observable effect of any treatments based on ET, shoot mass, or photosynthesis measurments. The absence of any beneficial F68 or GB effects for the droughted plants may indicate that the treatment concentrations, wheat cultivar (bred for drought tolerance), age of wheat (seedlings), presence of a root colonizing microbiome, and / or selected levels of drought / rehydration were not poised to reveal anticipated benefits from F68 (as a membrane repair agent) or GB (as a known plant protective osmolyte). F68 treatment did lead to increased ET and shoot mass for sufficiently watered plants, while not observably impacting the microbiome consisting of bacillus endophytes and PcO6 root colonizing epiphyte, supporting an agrochemical adjuvant role.

Beneficial impacts of endophytes such as the JunSE1L seed endophyte and probiotic root colonizers like

PcO6 may contribute to mitigation of abiotic stress, a finding already established with

PcO6 for drought-stressed plants [

27] and reported for other

Bacillus sp. isolates [

16,

28,

29]. F68 seed priming across a range of concentrations did not prevent plant emergence or endophyte release into the rhizosphere; however, F68 did slow the planktonic growth of the isolated JunSE1 seed endophyte, suggesting that this bacillus spp does not metabolize F68, an observation confirmed for

PcO6 previously [

17]. The enhanced shoot mass following F68 rhizosphere delivery may involve a greater efficacy in N utilization [

19,

20,

30], as suggested by the increased production of glutamate synthase for rice callus treated with F68 [

31,

32]. Thus, this work with seedlings indicates that F68 benefits plant survival during establishment when field-grown wheat is sensitive to drought. The mechanisms for F68 growth improvement require further investigation.

The higher foliar mass associated with F68 treatment occurred without improvements in photosynthetic ΦPsII quantum yield or the photosynthetic efficiency (Fv/Fm ratio), both of which dropped significantly during drought. We speculated that the membrane protective effects of F68 [

3,

5,

33,

34,

35] would reduce the drought-induced membrane damage and accompanying losses in photosynthetic yield and efficiency. Although there was no demonstration of buffered photosynthesis functions, the declines in photosynthetic activity caused by drought were restored upon rehydration, again suggesting that drought tolerance was already at its maximum because of the induced protection from

PcO6 root colonization [

27] and /or the protection offered by the seed endophytes.

Bacillus spp. isolates associated with wheat are correlated with improved drought tolerance [

16,

28,

29,

36].

Fluorescein conjugated F68 showed labelling of the perimeters of cells of the Gram-positive wheat seed endophyte, as was observed previously with the Gram-negative cells of

PcO6 [

17]. Thus, although the cell walls of Gram-positive cells differ from those of Gram-negative cells, both were similarly labelled with the membrane-inserting polymer, F68. Currently we do not know if F68 is internalized by the bacterial cells. Intracellular penetration was observed in the root epidermal cells as evinced by endosome labelling. It is possible that the nanosize of F68 unimers, about 5 nm, enabled its ready movement into and through the plant apoplast followed by intracellular trafficking through the plant cells’ aquaporins. Intracellular movement between plant cells would readily occur through the plasmodesmatal channels with the nanosized unimers. The term “dancing endosomes” was used by other researchers for these mobile endosomes, here labelled with fF68; these types of vesicles are proposed to carry cargo to and from the cell’s plasma membranes [

37,

38]. Our novel finding of when roots were exposed to fF68 also showed that the rapid mobility of endosomes was not inhibited by exposure to the Pluronic. The finding of fluorescence in both plant and bacterial cells upon exposure to fF68 suggests that this product could be used as a fast labelling technique that does not require genetic engineering of the cells with a gene encoding a fluorescent protein, such as the “green fluorescent protein” [

39].

Further studies are needed to understand the mechanisms by which F68 could be beneficial in agricultural formulations. Examining wheat through grain filling is necessary to determine whether F68 becomes translocated into the seed (perhaps carried by the

Bacillus endophyte). The existence of F68 as nanosized structures may improve soil transport and be integral for its cellular associations as revealed for plant and bacterial cells by use of the fluorescently-labeled product in these studies. The unimer form of F68, with an average hydrodynamic diameter near 5.4 nm, is anticipated to shift to micelles and larger aggregates with increasing concentrations[

40]. These agglomerates may not travel as well in the apoplast or symplastically in the plant. However, the average size of the F68 particles and polydispersity are highly dependent on temperature and solvent properties because micellization is driven by hydrophobic interactions. Other Pluronics with greater hydrophobic content (i.e., lower hydrophilic to lipophilic balance, HLB) form micelles at much lower concentrations. If encapsulating, solubilizing, and delivering hydrophobic agrochemicals are the goals, then Pluronics with lower HLB and CMC values than F68 are recommended. Although the high HLB of F68 makes it a weak micelle forming Pluronic, this property contributes to its biocompatibilty observed in these studies, and its unique membrane-active properties [

2].

5. Conclusions

The work in this paper shows the compatibility of Pluronic F68 at unimer concentrations with the growth of wheat as seedlings under watered conditions and drought stress. The beneficial effect of growth with F68 on shoot mass justifies further research examining the responses of wheat to F68 through maturation to seed formation. The research suggests that the probiotic effects from bacterial microbiomes would be maintained with F68 whether the bacteria were seed-borne endophytes or added as a seed-coating. The use of fluorescently labelled F68 allowed visualization of living bacterial and plant cells without the need for genetic engineering with genes encoding a fluorescent label. These observations with both the plant and their bacterial colonists suggest further studies of the use of Pluronic F68 as an adjuvant for agricultural formulations are appropriate, with future work investigating foliar applications and exploring a wider range of application doses and timing to identify anticipated benefits against abiotic stress.

Institutional Review Board Statement:. Not relevant.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: LI-6800 chamber environmental parameters for photosynthesis measurements. Figure S1: DLS of F68 solutions. Figure S2: F68 surface tension effects. Figure S3: Fv/Fm photosynthetic efficiency. Figure S4: Germination of surface-sterilized wheat seeds on LB 2% agar. Figure S5: Effect of F68 on planktonic growth of Bacillus sp. JunSE1L in minimal medium.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.W.B., A.J.A. methodology, A.C., M.Z., A.W., A.J.A., and D.W.B.; formal analysis, A.C., M.Z., A.W., A.J.A., A.R.J., J.E.M., and D.W.B.; investigation, A.C., M.Z., and A.W. ; writing—original draft preparation, A.J.A. and D.W.B.; writing—review and editing, A.C., M.Z., A.W., A.J.A., A.R.J., J.E.M., and D.W.B.; visualization, A.C., M.Z., A.W., A.J.A., A.R.J., J.E.M., and D.W.B.; supervision, A.J.A. and D.W.B.; project administration, D.W.B.; funding acquisition, A.J.A., A.R.J., J.E.M., and D.W.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was funded by grants from the Utah Agricultural Station Projects 1581 and 1746 and the National Science Foundation Research Experience for Undergraduate Program, 1950299.

Informed Consent Statement

Not relevant.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available upon request to the authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported with funding from Utah Agriculture Experiment Station, Projects 1581 and 1746, and by the Nanotechnology for Food and Agriculture Systems, project award no. 2024-67022-42830, from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hazen, J.L., 2000. Adjuvants—terminology, classification, and chemistry. Weed Technology, 14(4), pp.773-784. [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, T.A., Rose, A.L., Jung, R., Capati, A., Hallak, D., Yan, R. and Weisleder, N., 2020. Multiple poloxamers increase plasma membrane repair capacity in muscle and nonmuscle cells. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology, 318(2), pp.C253-C262.. [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.C., River, L.P., Pan, F.S., Ji, L. and Wollmann, R.L., 1992. Surfactant-induced sealing of electropermeabilized skeletal muscle membranes in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 89(10), pp.4524-4528.

- Adhikari, U., Goliaei, A., Tsereteli, L. and Berkowitz, M.L., 2016. Properties of poloxamer molecules and poloxamer micelles dissolved in water and next to lipid bilayers: results from computer simulations. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 120(26), pp.5823-5830.. [CrossRef]

- Moloughney, J. and Weisleder, N., 2012. Poloxamer 188 (p188) as a membrane resealing reagent in biomedical applications. Recent Patents on Biotechnology, 6(3), pp.200-211.. [CrossRef]

- Casella, J.F., Kronsberg, S.S. and Gorney, R.T., 2021. Poloxamer 188 vs placebo for painful vaso-occlusive episodes in children and adults with sickle cell disease—Reply. JAMA, 326(10), pp.975-976. [CrossRef]

- Orringer, E.P., Casella, J.F., Ataga, K.I., Koshy, M., Adams-Graves, P., Luchtman-Jones, L., Wun, T., Watanabe, M., Shafer, F., Kutlar, A. and Abboud, M., 2001. Purified poloxamer 188 for treatment of acute vaso-occlusive crisis of sickle cell disease: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 286(17), pp.2099-2106. [CrossRef]

- Kirova, E., Pecheva, D. and Simova-Stoilova, L., 2021. Drought response in winter wheat: Protection from oxidative stress and mutagenesis effect. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum, 43(1), p.8: 10.1007/s11738-020-03182-1.

- Tyagi, M. and Pandey, G.C., 2022. Physiology of heat and drought tolerance in wheat: An overview. Journal of Cereal Research, 14(1), pp.13-25. [CrossRef]

- Impa, S.M., Nadaradjan, S. and Jagadish, S.V.K., 2012. Drought stress induced reactive oxygen species and anti-oxidants in plants. Abiotic Stress Responses in Plants: metabolism, productivity and sustainability, pp.131-147.. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M., Lee, S.C., Kim, J.Y., Kim, S.J., Aye, S.S. and Kim, S.R., 2014. Over-expression of dehydrin gene, OsDhn1, improves drought and salt stress tolerance through scavenging of reactive oxygen species in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Journal of Plant Biology, 57, pp.383-. [CrossRef]

- Hellung-Larsen, P., Assaad, F., Pankratova, S., Saietz, B.L. and Skovgaard, L.T., 2000. Effects of Pluronic F-68 on Tetrahymena cells: protection against chemical and physical stress and prolongation of survival under toxic conditions. Journal of Biotechnology, 76(2-3), pp.185-195. [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P., Leach, J.E., Tringe, S.G., Sa, T. and Singh, B.K., 2020. Plant–microbiome interactions: from community assembly to plant health. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 18(11), pp.607-621. [CrossRef]

- Camaille, M., Fabre, N., Clément, C. and Ait Barka, E., 2021. Advances in wheat physiology in response to drought and the role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria to trigger drought tolerance. Microorganisms, 9(4), p.687. [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H., Jeong, B.R. and Glick, B.R., 2023. Biocontrol of plant diseases by Bacillus spp. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology, 126, p.102048.. [CrossRef]

- Lastochkina, O.V., 2021. Adaptation and tolerance of wheat plants to drought mediated by natural growth regulators Bacillus spp.: Mechanisms and practical importance. Agric. Biol, 56, pp.843-867. [CrossRef]

- Streeter, A.R., Cartwright, A., Zargaran, M., Wankhade, A., Anderson, A.J. and Britt, D.W., 2023. Adjuvant Pluronic F68 is compatible with a plant root-colonizing probiotic, Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6. Agrochemicals, 3(1), pp.1-11. [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, A., "Surface-Functionalized Silica Nanocarriers for Mitigating Water Stress in Wheat and Benefiting the Root Microbiome" (2023). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 8803. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/8803.

- Kok, A.D.X., Wan Abdullah, W.M.A.N., Tan, N.P., Ong-Abdullah, J., Sekeli, R., Wee, C.Y. and Lai, K.S., 2020. Growth promoting effects of Pluronic F-68 on callus proliferation of recalcitrant rice cultivar. 3 Biotech, 10, pp.1-10. [CrossRef]

- Kok, A.D.X., Mohd Yusoff, N.F., Sekeli, R., Wee, C.Y., Lamasudin, D.U., Ong-Abdullah, J. and Lai, K.S., 2021. Pluronic F-68 improves callus proliferation of recalcitrant rice cultivar via enhanced carbon and nitrogen metabolism and nutrients uptake. Frontiers in Plant Science, 12, p.667434. [CrossRef]

- Murungu, F.S., 2011. Effects of seed priming and water potential on seed germination and emergence of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) varieties in laboratory assays and in the field. African Journal of Biotechnology, 10(21), pp.4365-4371. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.P., Hui, Z., Li, F., Zhao, M.R., Zhang, J. and Wang, W., 2010. Improvement of heat and drought photosynthetic tolerance in wheat by overaccumulation of glycinebetaine. Plant Biotechnology Reports, 4, pp.213-222. [CrossRef]

- Kjar, A., Wadsworth, I., Vargis, E. and Britt, D.W., 2022. Poloxamer 188–quercetin formulations amplify in vitro ganciclovir antiviral activity against cytomegalovirus. Antiviral Research, 204, p.105362. [CrossRef]

- Alexandridis, P., Holzwarth, J.F. and Hatton, T.A., 1994. Micellization of poly (ethylene oxide)-poly (propylene oxide)-poly (ethylene oxide) triblock copolymers in aqueous solutions: thermodynamics of copolymer association. Macromolecules, 27(9), pp.2414-2425. [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, K., Anzai, T. and Fujimoto, Y., 1994. Fluorescence studies on the properties of a Pluronic F68 micelle. Langmuir, 10(3), pp.658-661. . [CrossRef]

- Mamou, G., Mohan, G.B.M., Rouvinski, A., Rosenberg, A. and Ben-Yehuda, S., 2016. Early developmental program shapes colony morphology in bacteria. Cell Reports, 14(8), pp.1850-1857.

- Cho, S.M., Kang, B.R., Han, S.H., Anderson, A.J., Park, J.Y., Lee, Y.H., Cho, B.H., Yang, K.Y., Ryu, C.M. and Kim, Y.C., 2008. 2R, 3R-butanediol, a bacterial volatile produced by Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6, is involved in induction of systemic tolerance to drought in Arabidopsis thaliana. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 21(8), pp.1067-1075.. [CrossRef]

- Lastochkina, O., Garshina, D., Ivanov, S., Yuldashev, R., Khafizova, R., Allagulova, C., Fedorova, K., Avalbaev, A., Maslennikova, D. and Bosacchi, M., 2020. Seed priming with endophytic Bacillus subtilis modulates physiological responses of two different Triticum aestivum L. cultivars under drought stress. Plants, 9(12), p.1810. [CrossRef]

- Lastochkina, O., Yuldashev, R., Avalbaev, A., Allagulova, C. and Veselova, S., 2023. The contribution of hormonal changes to the protective effect of endophytic bacterium Bacillus subtilis on two wheat genotypes with contrasting drought sensitivities under osmotic stress. Microorganisms, 11(12), p.2955. [CrossRef]

- Chichkova, S., Arellano, J., Vance, C.P. and Hernández, G., 2001. Transgenic tobacco plants that overexpress alfalfa NADH-glutamate synthase have higher carbon and nitrogen content. Journal of Experimental Botany, 52(364), pp.2079-2087. [CrossRef]

- Kok, A.D.X., Mohd Yusoff, N.F., Sekeli, R., Wee, C.Y., Lamasudin, D.U., Ong-Abdullah, J. and Lai, K.S., 2021. Pluronic F-68 improves callus proliferation of recalcitrant rice cultivar via enhanced carbon and nitrogen metabolism and nutrients uptake. Frontiers in Plant Science, 12, p.667434. [CrossRef]

- Kok, A.D.X., Wan Abdullah, W.M.A.N., Tan, N.P., Ong-Abdullah, J., Sekeli, R., Wee, C.Y. and Lai, K.S., 2020. Growth promoting effects of Pluronic F-68 on callus proliferation of recalcitrant rice cultivar. 3 Biotech, 10, pp.1-10.. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V., Stebe, K., Murphy, J.C. and Tung, L., 1996. Poloxamer 188 decreases susceptibility of artificial lipid membranes to electroporation. Biophysical Journal, 71(6), pp.3229-3241. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., McFaul, C., Titushkin, I., Cho, M. and Lee, R., 2018. Surfactant copolymer annealing of chemically permeabilized cell membranes. Regenerative Engineering and Translational Medicine, 4, pp.1-10. [CrossRef]

- Houang, E.M., Bates, F.S., Sham, Y.Y. and Metzger, J.M., 2017. All-atom molecular dynamics-based analysis of membrane-stabilizing copolymer interactions with lipid bilayers probed under constant surface tensions. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 121(47), pp.10657-10664: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b08938.

- Anderson, A.J., Hortin, J.M., Jacobson, A.R., Britt, D.W. and McLean, J.E., 2023. Changes in metal-chelating metabolites induced by drought and a root microbiome in wheat. Plants, 12(6), p.1209.. [CrossRef]

- Voigt, B., Timmers, A.C., Šamaj, J., Hlavacka, A., Ueda, T., Preuss, M., Nielsen, E., Mathur, J., Emans, N., Stenmark, H. and Nakano, A., 2005. Actin-based motility of endosomes is linked to the polar tip growth of root hairs. European Journal of Cell Biology, 84(6), pp.609-621.. [CrossRef]

- Von Wangenheim, D., Rosero, A., Komis, G., Šamajová, O., Ovečka, M., Voigt, B. and Šamaj, J., 2016. Endosomal interactions during root hair growth. Frontiers in Plant Science, 6, p.1262.. [CrossRef]

- Tsien, R.Y., 1998. The green fluorescent protein. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 67(1), pp.509-544.

- Zhou, Z. and Chu, B., 1988. Light-scattering study on the association behavior of triblock polymers of ethylene oxide and propylene oxide in aqueous solution. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 126(1), pp.171-180.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).