1. Introduction

β-carotene is a type of pigment known as a carotenoid, recognized for its antioxidant and mucosal protective properties. It is also referred to as provitamin A because it is converted into vitamin A in the small intestine [

1]. Among even-toed ungulates, cattle are unique in their ability to absorb and accumulate β-carotene, and a correlation has been reported between blood β-carotene levels and reproductive performance [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Fresh pasture, a common feed for cattle, contains high levels of β-carotene, allowing cattle to supplement this nutrient through their diet. However, the increasing use of preserved feed, such as silage and hay, has led to concerns about insufficient dietary intake of β-carotene [

8,

9,

10]. Consequently, health issues related to β-carotene or vitamin A deficiency in livestock have become a concern, prompting the addition of vitamin supplements to feed.

In Japan, the total production volume of pumpkins was approximately 182,900 tons in 2022, with Hokkaido accounting for approximately 94,000 tons, over 50% of the national production [

11]. Inedible parts, such as seeds and stringy pulp, are typically discarded and not effectively utilized. According to the Standard Tables of Food Composition in Japan, approximately 10% of

Cucurbita maxima, a pumpkin variety commonly consumed in Japan, is discarded as inedible parts [

12]. Pumpkin seeds are rich in functional components, such as fatty acids, proteins, and β-carotene, making them promising candidates for use in processed foods for humans and as livestock feed [

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, feeding whole pumpkin seeds directly to cattle can result in undigested seeds being excreted and germinating, leading to the emergence of non-edible wild pumpkins.

Another issue with pumpkins is the detection of heptachlor as a residual pesticide. Heptachlor is an organochlorine compound that was registered as a pesticide in Japan in 1957 but lost its registration in 1972. Globally, its production and use were banned under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants in 2001. Despite this, heptachlor is highly persistent in the environment and can remain in soil for extended periods. It is also selectively absorbed by cucurbitaceous plants, such as pumpkins. As a result, even more than 50 years after its ban in Japan, heptachlor can still be concentrated in pumpkins grown in contaminated soil. Particularly concerning is the potential for heptachlor to become concentrated during the drying process of pumpkin seeds and stringy pulp intended for processed foods or feed, possibly exceeding domestic regulatory limits [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Heptachlor can accumulate in cattle fat tissue, and cases of heptachlor exceeding regulatory limits in beef have been reported, prompting the establishment of a maximum residual limit for feed in Japan (0.02 μg/g) [

22,

23]. The residue limit for heptachlor is set as the sum of the main metabolites of heptachlor, cis-heptachlor epoxide and trans-heptachlor epoxide.

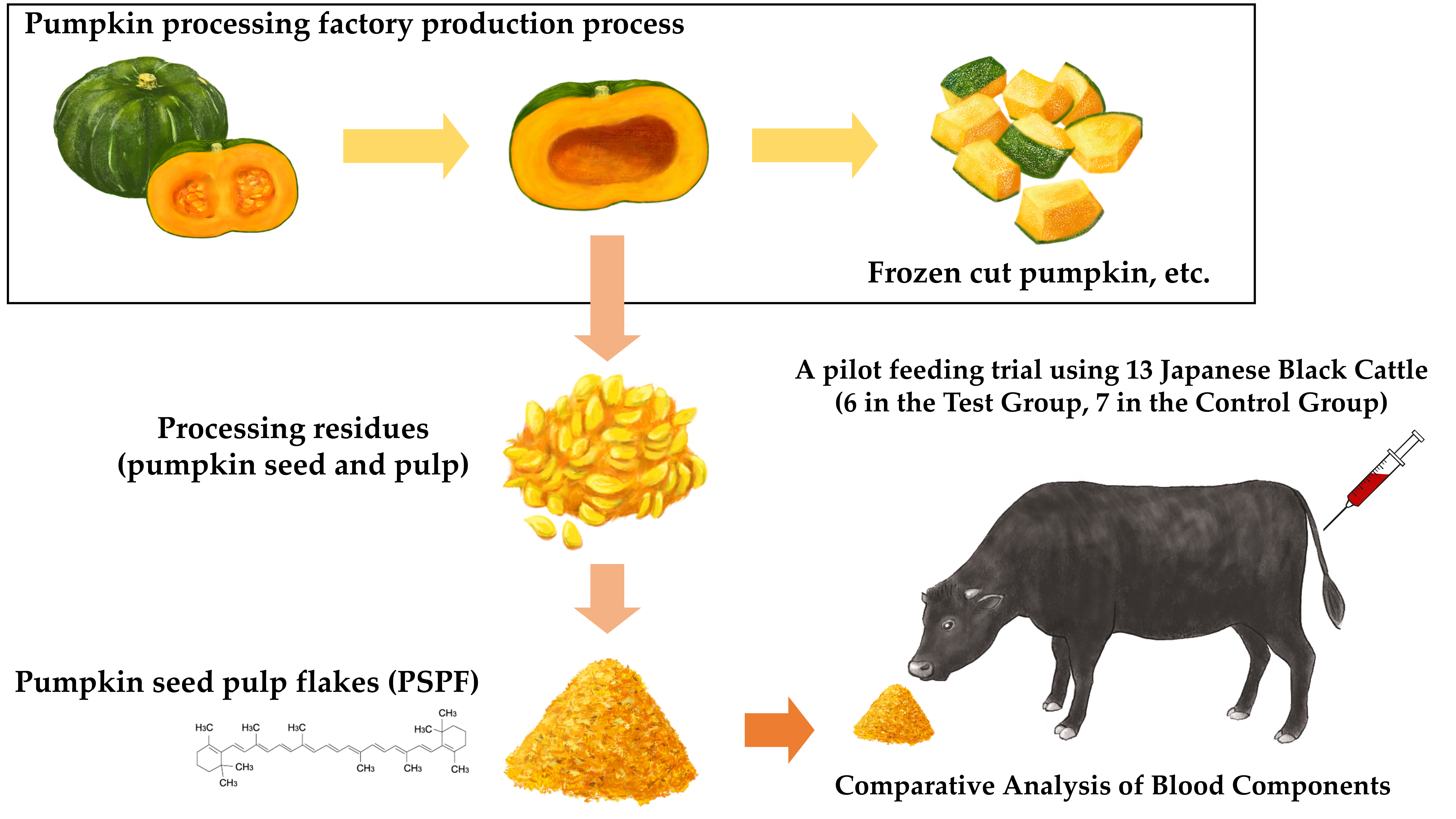

In this study, we processed pumpkin seed and stringy pulp waste from a pumpkin processing plant by crushing and drying into feed. We analyzed the residual pesticide and β-carotene concentrations across multiple production batches. Furthermore, we conducted a pilot feeding study in cattle and analyzed their blood parameters.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Production of Pumpkin Seed Pulp Flakes (PSPF)

Pumpkin residue (seeds and stringy pulp) discharged from the production line of a food processing facility was collected. The residue varied in size, ranging approximately from 20 to 100 mm. Its moisture content was 80.7% by weight. The collected residue was processed using a cutting device (URSCHEL Corp., Chesterton, IN, USA), operated at 3,000 rpm for 60 min. This procedure reduced the residue, including the seeds, to fragments approximately 1–5 mm in size. The resulting material was then dried using a vacuum dryer set to an internal temperature of 85 °C. The drying process was conducted for 16 h under conditions of 5 rpm agitation and an absolute pressure of 8.0–10.0 kPa. This treatment yielded a processed feed product derived from pumpkin residue, with a final moisture content of 10.8% by weight and particle size of approximately 1–5 mm. This processed feed has been patented in Japan.

2.2. Analysis of Heptachlor Content

Heptachlor analysis was performed by an external analysis agency, Japan Food Research Laboratories (Tokyo, Japan), using a foundation-specified method.

First, 10 g of the sample was combined with 30 mL of water and 100 mL of acetone, and subjected to shaking extraction for 60 min. The extract was filtered under vacuum, and the filtrate was adjusted to 200 mL with acetone. A 20-mL aliquot of this solution was concentrated and loaded onto a solid-phase extraction cartridge (InertSeo K-solute Plus, 5 mL), followed by elution with 40 mL of hexane. The eluate was concentrated to dryness and reconstituted to 10 mL with hexane. A 5-mL portion of this solution was then applied to a second solid-phase cartridge (Sep-Pak Plus Florisil, 910 mg), and eluted with 20 mL of a hexane:diethyl ether (24:1) mixture. The eluate was again concentrated to dryness and reconstituted in 1 mL of hexane. A 1-μL aliquot of this final solution was injected into the GC-MS.

GC-MS analysis was performed using a VF-5MS column (15 m in length, 0.25 mm inner diameter, and 0.25-μm thick film; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in conjunction with an Agilent 7890B/7010B GC-MS system (Agilent Technologies). The initial oven temperature was set at 70 °C and held for 1 min, then increased to 200 °C at a rate of 25 °C/min, followed by a ramp to 310 °C at 15 °C/min, and held for 5 min. The carrier gas (He) flow rate was maintained at 1.701 mL/min. The injector temperature was set to 250 °C and ion source temperature to 320 °C. Injection was performed in pulsed splitless mode (pulse pressure 25 psi, 1 min). Electron impact ionization was used to acquire mass spectra. Quantification was based on the peak areas of the mass fragments at m/z 272→237 (heptachlor), 355→265 (cis-heptachlor epoxide), and 217→182 (trans-heptachlor epoxide).

2.3. Analysis of β-Carotene

A β-carotene standard (purity ≥ 95.0%) was purchased from Kanto Chemical Co., Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). Pyrogallol (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan), hexane, acetone, ethanol, and toluene (Kanto Chemical Co., Inc.), potassium hydroxide (Junsei Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), sodium chloride (Kanto Chemical Co., Inc.), ethyl acetate (Kanto Chemical Co., Inc.), and tetrahydrofuran (Junsei Chemical Co., Ltd.) were of Japanese Industrial Standards grade. The 2,6-Di-tert-butyl-p-cresol (Kanto Chemical Co., Inc.) was of Cica Special Grade, dl-α-tocopherol (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) was Wako 1st Grade, and ethanol and cyclohexane (Junsei Chemical Co., Ltd.) were of HPLC grade. Acetonitrile (Kanto Chemical Co., Inc.) and acetic acid (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) were of LC-MS grade.

β-carotene was quantified using HPLC [

24,

25]. A 0.5-g portion of the powdered sample was accurately weighed into a brown volumetric flask, followed by the addition of 3 g of pyrogallol and 5 mL of water, and gently mixed. Then, 10 mL of HEAT solvent mixture (hexane/acetone/ethanol/toluene = 10/7/6/7 (v/v/v/v), containing 0.1% 2,6-Di-tert-butyl-p-cresol) was added and vigorously mixed. This step was repeated twice more with 10 mL of the same HEAT mixture. Subsequently, 10 mL of ethanol containing 0.05 g/L α-tocopherol was added and mixed vigorously; this step was repeated once. The solution was brought to volume with the same ethanol solution, sonicated for 10 min, and left to stand overnight.

After standing, 10 mL of the extract was transferred to a 50-mL tube and 2 g of potassium hydroxide was added. After vortexing, the mixture was saponified at 70 °C for 30 min, then rapidly cooled with water. A 20-mL portion of 1% (w/v) sodium chloride solution and 15 mL of a hexane/ethyl acetate mixture (9/1) were added, and the tube was shaken for 5 min under light shielding with aluminum foil. After centrifugation (2500 rpm, 2 min), the upper layer was transferred to a concentration vessel. The remaining lower layer was extracted twice more with 15 mL of the same solvent mixture. The combined upper layers were concentrated under reduced pressure at 40 °C, transferred to a 10-mL test tube while washing with the same solvent, and dried under nitrogen while warming at 40 °C. The residue was dissolved in ethanol and brought to a 5-mL volume. A 10 μL aliquot of this solution was injected into an HPLC system (Agilent 1200 series, Agilent Technologies).

The analytical column used was Kinetex C18 (4.6 × 150 mm, 5 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile/methanol/tetrahydrofuran/acetic acid = 55/40/5/0.1 (v/v/v/v) containing 0.05 g/L of dl-α-tocopherol and the flow rate was set at 0.8 mL/min. The column temperature was maintained at 40 °C and detection was performed at 455 nm. A blank solution prepared in the same manner without the sample was used as a control.

The β-carotene standard stock solution (100 μg/mL) was prepared in cyclohexane and diluted 50-fold to 2 μg/mL. The absorbance of this diluted solution was measured at 455 nm and the concentration was calculated using the following formula:

Concentration of standard solution (μg/mL) = absorbance at 455 nm × 10000 / 2500 (1)

Additionally, a 10-μg/mL standard solution was prepared by diluting the 100 μg/mL stock solution 10-fold with ethanol and further diluted to prepare a calibration curve in the range of 0.1–2 μg/mL.

2.4. Feeding Trial in Cattle (Pilot Study)

Seven adult Japanese Black donor cows were fed 500 g/day of pumpkin seed pulp flakes (PSPF) in addition to their conventional silage-based diet for a period of 34 days. As a control group, six adult Japanese Black donor cows were maintained on the conventional diet alone. The amount of conventional feed provided to the control group was adjusted to match that of the treatment group as closely as possible. Blood samples were collected from both the treatment and control groups before and after the feeding period. Plasma was separated by centrifugation and subjected to biochemical analysis. The feeding trial was conducted at the donor cow facility of AG Embryo Support Co., Ltd. (Obihiro, Hokkaido, Japan). Blood biochemical analyses were outsourced to Obihiro Clinical Laboratory Inc. (Obihiro, Japan).

Blood biochemical parameters were evaluated, including glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), total cholesterol (T-CHO), total protein (TP), albumin (ALB), albumin/globulin ratio (A/G ratio), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), glucose (GLU), non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA), calcium (Ca), phosphorus (IP), magnesium (Mg), 3-hydroxybutyrate (3-HB), vitamin A (VA), and β-carotene (βC).

For each blood biochemical parameter, homogeneity of variances between pre- and post-administration values was first assessed using the F-test at a significance level of 0.05. Based on the results, Student’s t-test was applied for parameters with equal variances, while Welch’s t-test was used for those with unequal variances. All tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Heptachlor Content in PSPF

Table 1 summarizes the cultivation fields and heptachlor concentrations of PSPF produced on different manufacturing dates (

Supplementary Figure S1). The heptachlor concentrations varied depending on the production date and some samples exceeded the Japanese regulatory limit for animal feed (0.02 μg/g). In contrast, all samples (No. 7–11) derived from pumpkins cultivated in Air Water Group's contracted fields exhibited heptachlor concentrations below the regulated threshold.

3.2. Analysis of β-Carotene Content in PSPF

Table 2 presents the manufacturing dates, cultivation fields of the raw pumpkins, and β-carotene concentrations for 11 different production lots of PSPF (

Supplementary Figure S2).

3.3. Feeding Trial in Cattle (Pilot Study)

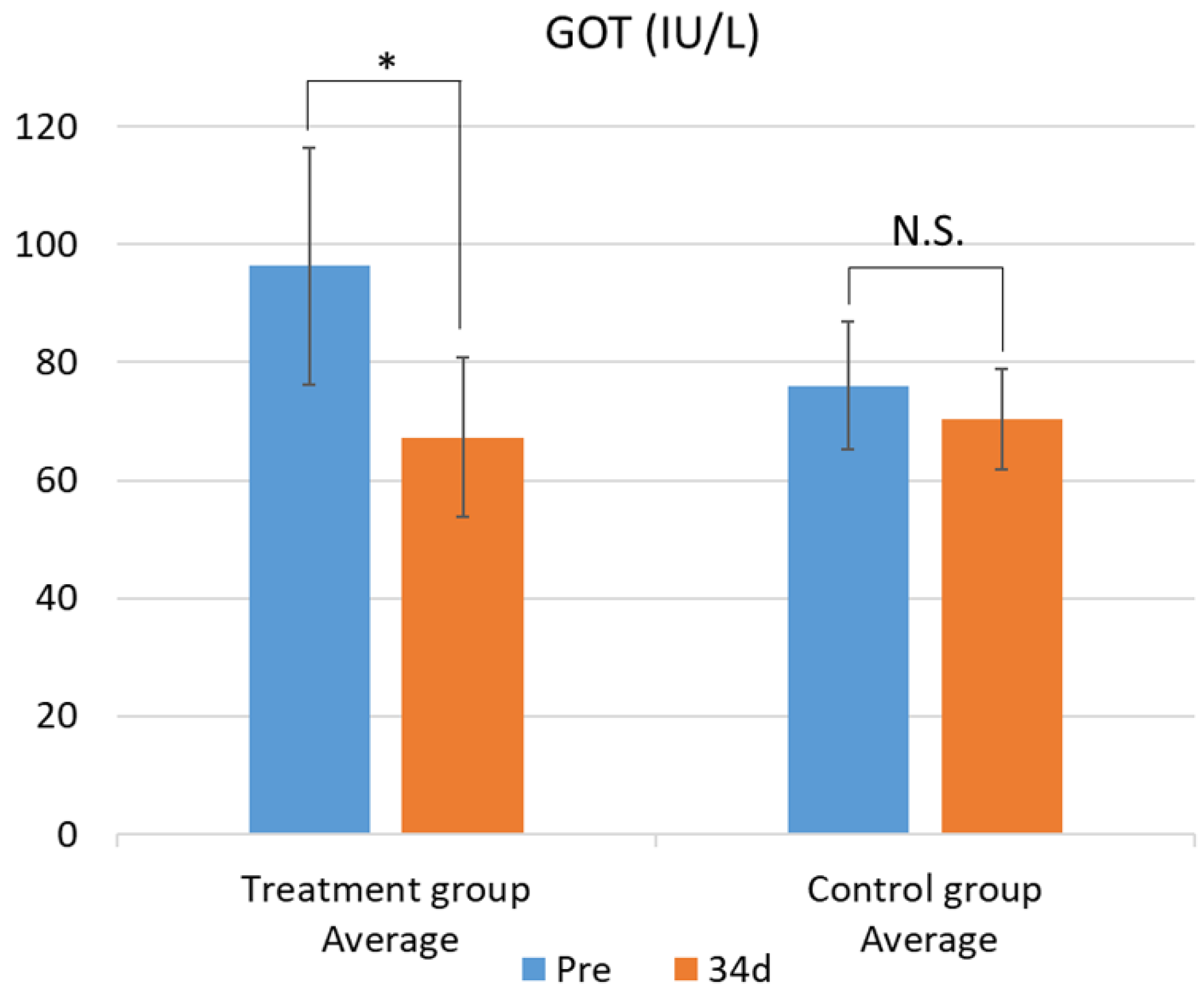

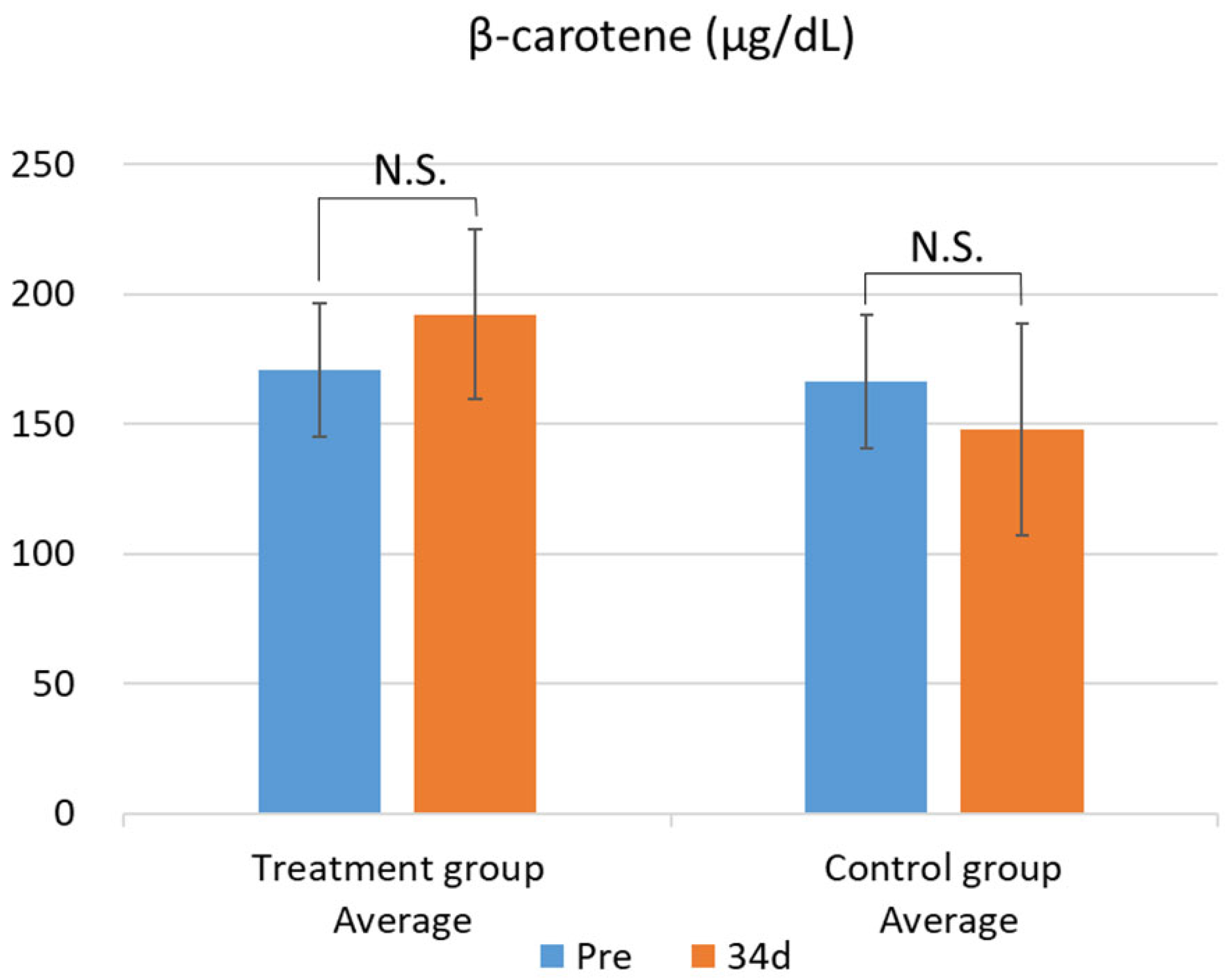

The results of the blood biochemical analysis are shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4. In the test group, GOT values significantly decreased (

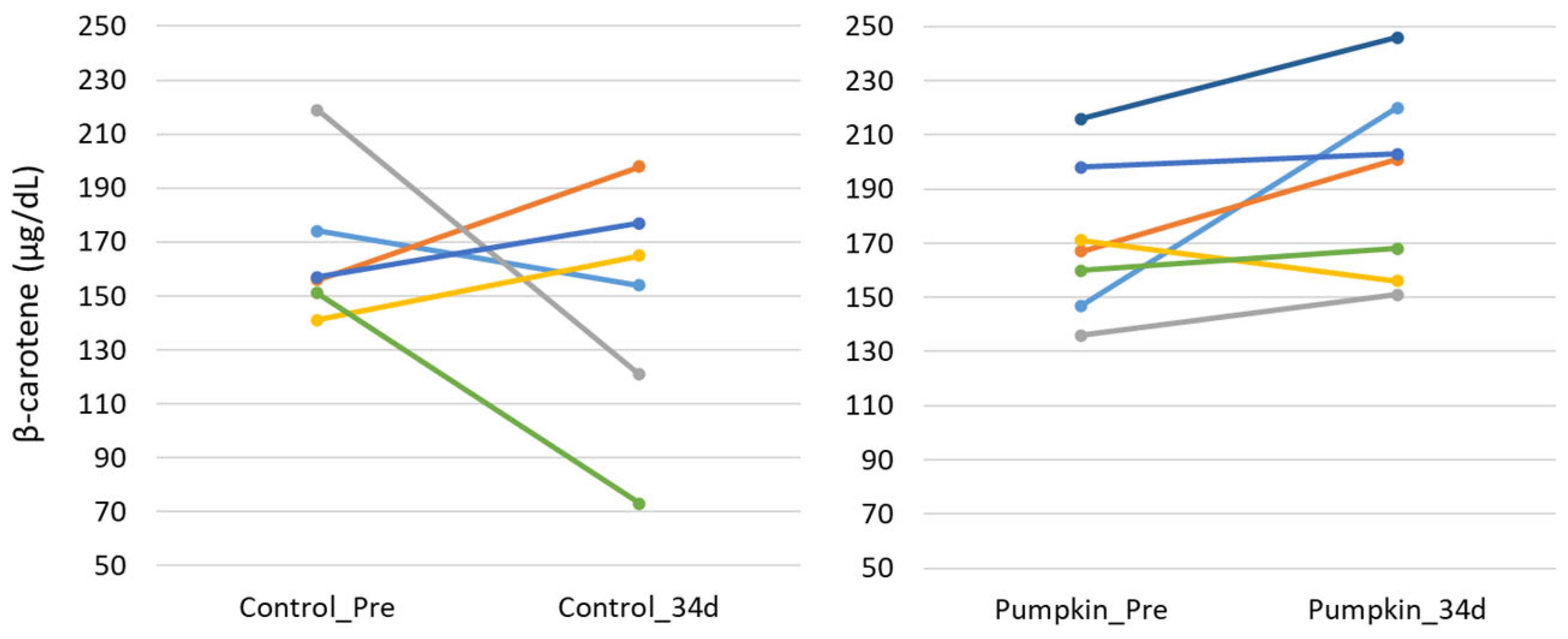

Figure 1). This difference was confirmed by the F-test followed by Welch’s t-test, with a p-value less than 0.05. In contrast, no significant changes were observed in the other parameters. While there was no significant difference in blood β-carotene levels, the test group showed a tendency for increased blood β-carotene concentrations compared with that of the control group (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Changes in plasma GOT levels between the treatment and control groups. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using Welch’s t-test; p < 0.05 was considered significant. Mean plasma GOT concentrations before (Pre) and after (34d) the feeding trial in the group fed pumpkin seed pulp flakes (left) and the control group (right). * p < 0.05. N.S., not significant (p ≥ 0.05). GOT, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase.

Figure 1.

Changes in plasma GOT levels between the treatment and control groups. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using Welch’s t-test; p < 0.05 was considered significant. Mean plasma GOT concentrations before (Pre) and after (34d) the feeding trial in the group fed pumpkin seed pulp flakes (left) and the control group (right). * p < 0.05. N.S., not significant (p ≥ 0.05). GOT, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase.

Figure 2.

Changes in plasma β-carotene levels between the treatment and control groups. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using Welch’s t-test; p < 0.05 was considered significant. Mean plasma β-carotene concentrations before (Pre) and after (34d) the feeding trial in the group fed pumpkin seed pulp flakes (left) and the control group (right). N.S., not significant (p ≥ 0.05).

Figure 2.

Changes in plasma β-carotene levels between the treatment and control groups. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using Welch’s t-test; p < 0.05 was considered significant. Mean plasma β-carotene concentrations before (Pre) and after (34d) the feeding trial in the group fed pumpkin seed pulp flakes (left) and the control group (right). N.S., not significant (p ≥ 0.05).

Figure 3.

Changes in plasma β-carotene concentration. Changes in plasma β-carotene concentrations before (control_Pre) and after 34 days (control_34d) of the feeding trial in the control group (left), and before (pumpkin_Pre) and after 34 days (pumpkin_34d) in the group fed pumpkin seed pulp flakes (right).

Figure 3.

Changes in plasma β-carotene concentration. Changes in plasma β-carotene concentrations before (control_Pre) and after 34 days (control_34d) of the feeding trial in the control group (left), and before (pumpkin_Pre) and after 34 days (pumpkin_34d) in the group fed pumpkin seed pulp flakes (right).

Table 3.

The results of the blood biochemical analysis (Treatment group).

Table 3.

The results of the blood biochemical analysis (Treatment group).

| Parameter |

GOT |

GGT |

T-CHO |

TP |

ALB |

A/G Ratio |

BUN |

GLU |

NEFA |

Ca |

IP |

Mg |

3-HB |

VA |

βC |

| Unit |

IU/L |

IU/L |

mg/100 mL |

g/100 mL |

g/100 mL |

- |

mg/100 mL |

mg/100 mL |

mmol/L |

mg/100 mL |

mg/100 mL |

mg/100 mL |

mmol/L |

IU/dL |

μg/dL |

Treatment

group |

Pre |

1 |

70 |

9 |

158 |

7.3 |

3.4 |

0.9 |

55 |

8.9 |

5.4 |

2.4 |

466 |

90 |

147 |

90 |

147 |

| 2 |

113 |

26 |

165 |

7.4 |

3.5 |

0.9 |

59 |

9.4 |

5.9 |

2.3 |

454 |

90 |

167 |

90 |

167 |

| 3 |

72 |

14 |

104 |

8.3 |

3.2 |

0.6 |

51 |

9.0 |

5.5 |

2.1 |

445 |

83 |

136 |

83 |

136 |

| 4 |

113 |

15 |

91 |

7.1 |

3.3 |

0.9 |

62 |

9.4 |

5.9 |

2.0 |

337 |

97 |

171 |

97 |

171 |

| 5 |

109 |

36 |

146 |

8.3 |

3.2 |

0.6 |

85 |

9.5 |

5.5 |

1.9 |

288 |

97 |

198 |

97 |

198 |

| 6 |

78 |

15 |

108 |

6.5 |

2.9 |

0.8 |

51 |

8.1 |

4.8 |

2.9 |

426 |

97 |

160 |

97 |

160 |

| 7 |

119 |

22 |

130 |

8.3 |

3.6 |

0.8 |

73 |

9.3 |

5.6 |

2.3 |

397 |

100 |

216 |

100 |

216 |

| Mean ± SD |

96 ± 22 |

20 ± 9.1 |

129 ± 29 |

7.6 ± 0.71 |

3.3 ± 0.23 |

0.79 ± 0.13 |

62 ± 13 |

9.1 ± 0.49 |

5.5 ± 0.37 |

2.3 ± 0.33 |

402 ± 66 |

93 ± 6.0 |

171 ± 28 |

93 ± 6.0 |

171 ± 28 |

| 34 d |

1 |

42 |

12 |

137 |

5.4 |

2.7 |

1.0 |

34 |

6.9 |

4.7 |

1.9 |

296 |

80 |

220 |

80 |

220 |

| 2 |

70 |

40 |

195 |

8.1 |

3.7 |

0.9 |

65 |

10.2 |

5.4 |

2.6 |

393 |

70 |

201 |

70 |

201 |

| 3 |

60 |

16 |

118 |

8.4 |

3.3 |

0.6 |

49 |

8.9 |

4.5 |

2.2 |

304 |

80 |

151 |

80 |

151 |

| 4 |

67 |

17 |

100 |

6.9 |

3.2 |

0.9 |

60 |

9.1 |

5.6 |

2.2 |

342 |

90 |

156 |

90 |

156 |

| 5 |

88 |

46 |

164 |

8.4 |

3.1 |

0.6 |

12 |

67 |

111 |

9.4 |

6.5 |

1.4 |

209 |

67 |

203 |

| 6 |

65 |

19 |

133 |

7.1 |

3.2 |

0.8 |

16 |

62 |

66 |

9.2 |

6.1 |

2.2 |

417 |

87 |

168 |

| 7 |

79 |

26 |

140 |

8.2 |

3.6 |

0.8 |

17 |

68 |

47 |

9.4 |

6.2 |

2.6 |

365 |

100 |

246 |

| Mean ± SD |

67 ± 15 |

25 ± 13 |

141 ± 31 |

7.5 ± 1.1 |

3.3 ± 0.33 |

0.80 ± 0.15 |

14 ± 2.7 |

61 ± 7.0 |

62 ± 25 |

9.0 ± 1.0 |

5.6 ± 0.76 |

2.2 ± 0.42 |

332 ± 70 |

82 ± 11 |

192 ± 35 |

Table 4.

The results of the blood biochemical analysis (Control group).

Table 4.

The results of the blood biochemical analysis (Control group).

| Parameter |

GOT |

GGT |

T-CHO |

TP |

ALB |

A/G Ratio |

BUN |

GLU |

NEFA |

Ca |

IP |

Mg |

3-HB |

VA |

βC |

| Unit |

IU/L |

IU/L |

mg/100 mL |

g/100 mL |

g/100 mL |

- |

mg/100 mL |

mg/100 mL |

mmol/L |

mg/100 mL |

mg/100 mL |

mg/100 mL |

mmol/L |

IU/dL |

μg/dL |

Control

group |

Pre |

1 |

83 |

6 |

139 |

7.1 |

3.2 |

0.8 |

51 |

9.6 |

6.9 |

1.9 |

377 |

100 |

174 |

100 |

174 |

| 2 |

72 |

7 |

144 |

6.8 |

3.4 |

1.0 |

56 |

9.2 |

6.9 |

2.5 |

408 |

90 |

156 |

90 |

156 |

| 3 |

79 |

12 |

151 |

7.1 |

3.6 |

1.0 |

87 |

9.9 |

6.2 |

2.2 |

437 |

117 |

219 |

117 |

219 |

| 4 |

54 |

17 |

143 |

7.1 |

3.3 |

0.9 |

52 |

9.4 |

6.2 |

2.1 |

448 |

87 |

141 |

87 |

141 |

| 5 |

87 |

7 |

130 |

6.8 |

3.4 |

1.0 |

142 |

9.4 |

5.9 |

2.2 |

301 |

97 |

157 |

97 |

157 |

| 6 |

81 |

6 |

151 |

7.2 |

3.4 |

0.9 |

40 |

9.5 |

6.5 |

2.0 |

306 |

80 |

151 |

80 |

151 |

| Mean ± SD |

76 ± 12 |

9.2 ± 4.4 |

143 ± 7.9 |

7.0 ± 0.17 |

3,4 ± 0.13 |

0.93 ± 0,08 |

71 ± 38 |

10 ± 0.24 |

6.4 ± 0.41 |

2.2 ± 0.21 |

380 ± 64 |

95 ± 13 |

166 ± 28 |

95 ± 13 |

166 ± 28 |

| 34 d |

1 |

74 |

10 |

152 |

7.3 |

3.3 |

0.8 |

69 |

10.2 |

5.6 |

2.1 |

252 |

70 |

154 |

70 |

154 |

| 2 |

72 |

14 |

144 |

6.6 |

3.3 |

1.0 |

54 |

9.2 |

6.5 |

2.7 |

327 |

90 |

198 |

90 |

198 |

| 3 |

70 |

15 |

144 |

7.1 |

3.6 |

1.1 |

60 |

10.1 |

5.9 |

2.2 |

282 |

70 |

121 |

70 |

121 |

| 4 |

52 |

12 |

154 |

7.4 |

3.5 |

0.9 |

88 |

9.3 |

5.8 |

2.1 |

300 |

77 |

165 |

77 |

165 |

| 5 |

78 |

16 |

132 |

6.8 |

3.4 |

1.0 |

93 |

9.5 |

5.9 |

2.2 |

250 |

93 |

177 |

93 |

177 |

| 6 |

76 |

1 |

150 |

7.3 |

3.5 |

0.9 |

41 |

9.8 |

5.6 |

2.1 |

267 |

103 |

73 |

103 |

73 |

| Mean ± SD |

70 ± 9.4 |

11 ± 5.5 |

146 ± 8.0 |

7.1 ± 0.32 |

3.4 ± 0.12 |

1.0 ± 0.10 |

68 ± 20 |

10 ± 0.42 |

5.9 ± 0.33 |

2.2 ± 0.23 |

280 ± 30 |

84 ± 14 |

148 ± 45 |

84 ± 14 |

148 ± 45 |

Feedback from the farm where the trial was conducted indicated that the dried PSPF were easy to store long-term, mix into concentrated feed, and feed to cattle. The flakes were highly palatable, and the cattle consistently consumed all of their feed.

4. Discussion

In this study, we processed pumpkin seed and stringy pulp waste from Hokkaido-grown pumpkins by crushing and drying it into flakes, and analyzed the residual pesticide (heptachlor) and β-carotene concentrations.

Our analysis revealed that residual heptachlor concentrations varied depending on the cultivation field, regardless of the production period. This variation is presumed to result from the presence or absence of residual heptachlor in the soil where the pumpkins were grown. Notably, all production lots derived from pumpkins cultivated in contract fields managed by the Air Water Group complied with the Japanese regulatory limit for animal feed. These findings suggest that by tracing the cultivation fields of the raw pumpkins, it is possible to control the safety of the final product with respect to residual pesticides, which may become concentrated during the drying process. To further enhance product safety, it is recommended to conduct pre-cultivation soil analyses for residual pesticides and confirm the absence of heptachlor in the designated fields.

The produced PSPF contained an average of 7,100 μg/100g of β-carotene. However, many of the samples had been stored for over one year since production and factors, such as storage conditions in paper bags, may have contributed to a decrease in β-carotene content compared to immediately after production. At the time of manufacture, the flakes contained approximately 17,000 μg/100 g of β-carotene. These findings suggest that the β-carotene concentration in the flakes may decrease by approximately half after one year of storage. To minimize this degradation, improvements in storage conditions, such as airtight sealing, light shielding, and control of temperature and humidity, are necessary.

Synthetic β-carotene is commonly used as an additive in cattle feed, therefore, a 100% natural feed source is considered highly valuable. Furthermore, as the flakes are made entirely from pumpkin, they are highly palatable to cattle and represent an environmentally friendly feed option through the use of underused agricultural by-products. In addition to β-carotene, the inclusion of crushed seeds suggests that the flakes are also rich in typical pumpkin seed oil components, such as unsaturated fatty acids. These constituents may offer additional benefits to cattle, and further compositional analysis and validation studies are warranted to evaluate their potential effects.

A pilot study was conducted using 13 cattle, with 7 assigned to the treatment group and 6 to the control group. In the treatment group, a trend toward increased plasma β-carotene concentrations was observed. Notably, freshly manufactured PSPF were used in the feeding trial. The increase in plasma β-carotene levels in the treated cattle is presumed to result from the absorption of β-carotene contained in the flakes. Maintaining adequate plasma β-carotene concentrations in cattle has been reported to enhance immune function and improve reproductive performance [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

26,

27,

28]. Studies on Hanwoo cattle have shown that feeding fat-coated β-carotene increases blood β-carotene levels and significantly improves pregnancy rates after embryo transfer [

27]. Similarly, Japanese Black cattle with high plasma β-carotene content have high progesterone secretion and superior reproductive function [

28].

The improvement in reproductive function associated with β-carotene is presumed to involve the following three mechanisms:

(1) Vitamin A, which is converted from β-carotene in the body, is essential for maintaining ovarian function, follicular maturation, corpus luteum formation, and endometrial health. A deficiency in vitamin A can lead to reproductive disorders, such as delayed estrus, infertility, and miscarriage.

(2) β-carotene is a potent antioxidant that protects ovarian and uterine cells from oxidative stress. Oxidative stress can impair oocyte quality and hinder embryo implantation, therefore, its mitigation by β-carotene may contribute to improved conception rates.

(3) In cattle with higher blood β-carotene concentrations, corpus luteum development is enhanced, and the secretion of progesterone, critical for the maintenance of pregnancy, is increased and stabilized, thereby promoting embryo implantation and retention.

Maintaining blood β-carotene levels above 200 μg/dL accelerates postpartum reproductive recovery and improves pregnancy rates [

5]. In the pilot study, four out of seven cows in the test group had blood β-carotene levels above 200 μg/dL, suggesting that adding PSPF to feed can improve blood β-carotene levels and reproductive function in cattle.

Additionally, the test group exhibited a significant reduction in serum GOT levels, a biomarker of hepatic injury. A similar trend has been previously reported [

29], where dietary supplementation with pumpkin seed cake led to decreased GOT activity in cows. Furthermore, seed protein derived from pumpkin (

Cucurbita pepo) has been shown to ameliorate liver dysfunction, including elevated GOT levels, induced by an unbalanced diet [

30,

31]. Although PSPF developed in the present study were derived from

Cucurbita maxima—a species distinct from those used in the aforementioned studies—the possibility of a comparable hepatoprotective effect cannot be excluded. To confirm this hypothesis, further investigations are needed, including comparative analyses of the seed protein profiles of

Cucurbita pepo and

Cucurbita maxima squash, as well as veterinary clinical trials in cattle.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the potential of using pumpkin seed and stringy pulp waste from Hokkaido processing plants as livestock feed. Crushing and drying the seeds, and stringy pulp together prevented the emergence of wild pumpkins and made the waste suitable for feed. Residual pesticide (heptachlor) analysis showed variability depending on the fields where the pumpkins were grown, with some samples exceeding domestic feed standards. However, pumpkins grown in fields contracted by Air Water Group met the standards. The produced PSPF contained high levels of β-carotene, and feeding trials in Japanese Black cows showed a tendency for increased blood β-carotene levels and significant improvement in GOT values. Importantly, no adverse effects were observed in the pilot study, indicating the safety of PSPF as feed. These preliminary findings suggest that PSPF may improve immune function, reproductive performance, and liver cell protection in cattle. Further research is needed to validate these effects and elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

We demonstrated the potential of using pumpkin seed and stringy pulp waste, typically treated as industrial waste, as livestock feed. This initiative has the potential to have a positive impact on both pumpkin farmers and livestock farmers by increasing the value of pumpkins and providing high-quality, naturally derived feed for livestock. We will continue to promote the effective use of unused resources, such as pumpkin seeds and stringy pulp waste, contributing to the development of agriculture and livestock industries in Japan and addressing environmental issues.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Excerpt of GC/MS Chromatogram of heptachlor, S2: HPLC Chromatogram of β-carotene.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.N., H.I., J.N., and E.K.; Methodology: M.N., H.I., J.N., and E.K.; Software: M.N., and J.N.; Validation: J.N., D.M., and E.K.; Formal analysis: M.N., and J.N.; Investigation: M.N., H.I., J.N., and E.K.; Resources: H.I.; Data curation: M.N., J.N., and E.K.; Writing—original draft preparation: M.N., H.I., J.N., and E.K.; Writing—review and editing: M.N., J.N., and E.K.; Visualization: M.N., J.N., and E.K.; supervision: E.K.; Project administration: J.N., and E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to it being a pilot study conducted by volunteers, using samples registered as feed type A in Japan, a classification defined under Japanese regulations to indicate animal protein-free feed.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author, E.K., due to the inclusion of analysis data from external institutions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Taisei Feed Co., Ltd. and AG Embryo Support Co., Ltd. for their assistance in the bovine experiment. We also thank Ms. S. Kawata for her support with the component analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

M.N. and J.N. are the employees of AIR WATER INC., Osaka, Japan. H. I. is an employee of Air Water Logistics Co., Ltd., Hokkaido, Japan. D. M. is Representative Director of Shepherd Central Livestock Clinic Co., Ltd., Kagoshima, Japan. E.K. is a medical advisor of AIR WATER INC., Osaka, Japan, and the Representative Director of Kobayashi Regenerative Research Institute, LLC., Wakayama, Japan.

References

- Takahashi, N.; Li, C.; Imai, M. Prevention and treatment of various diseases by vitamin A and β-carotene. J Oleo Sci 2014, 14, 523–530. [Google Scholar]

- Green, A.S.; Fascetti, A.J. Meeting the vitamin A requirement: The efficacy and importance of β-carotene in animal species. ScientificWorldJournal 2016, 2016, 7393620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuishi, H.; Yayota, M. The efficacy of β-carotene in cow reproduction: A review. Animals (Basel) 2024, 14, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, C.; Matsui, M.; Shimizu, T.; Kida, K.; Miyamoto, A. Nutritional factors that regulate ovulation of the dominant follicle during the first follicular wave postpartum in high-producing dairy cows. Journal of Reproduction and Development 2012, 58, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunji, M.; Yumura, Y. Relationship Between Blood β-Carotene Concentration and Reproductive Performance in Japanese Black Cattle. Kurayoshi Livestock Hygiene Service Center, Tottori Prefecture, 2016.

- Ježek, J.; Klinkon, M.; Nemec, M.; Hodnik, J. J.; Starič, J. β-carotene concentration in blood serum of cows from herds with impaired fertility. Acta fytotechn zootechn 2020, 23, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubova, T.V.; Pleshkov, V.A.; Smolovskaya, O.V.; Mironov, A.N.; Korobeynikova, L.N. The use of carotene-containing preparation in cows for the prevention of postpartum complications. Vet World 2021, 14, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozière, P.; Graulet, B.; Lucas, A.; Martin, B.; Grolier, P.; Doreau, M. Carotenoids for ruminants: From forages to dairy products. Anim Feed Sci Technol 2006, 131, 418–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, A.E.P.; Artavia Mora, J.I.; Ronda Borzone, P.A.; Richards, S.E.; Kies, A.K. Vitamin E and beta-carotene status of dairy cows: A survey of plasma levels and supplementation practices. Animal 2021, 15, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripoll, G.; Casasús, I.; Joy, M.; Molino, F.; Blanco, M. Fat color and reflectance spectra to evaluate the β-carotene, lutein and α-tocopherol in the plasma of bovines finished on meadows or on a dry total mixed ration. Anim Feed Sci Technol 2015, 207, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. The 98th statistical yearbook of Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. MAFF, 2025. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/e/data/stat/98th/index.html.

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT). Standard tables of food composition in Japan (Eighth Revised Edition) [Supplement] 2023, Chapter 2. MEXT. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/syokuhinseibun/mext_00001.html, 2020.

- Sathiya Mala, K.; Kurian, A. E. Nutritional composition and antioxidant activity of pumpkin wastes. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci 2016, 6, 336–344. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, Q.A.; Akram, M.; Shukat, R. Nutritional and Therapeutic Importance of the Pumpkin Seeds. BJSTR 2019, 21, 15798–15803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.; Noreen, S.; Khalid, W.; Ejaz, A.; Rasool, I.F.U.; Maham, M.A.; Farwa, J.M.; Ercisli, S.; et al. Pumpkin and pumpkin by-products: Phytochemical constituents, food application and health benefits. Molecules 2023, 28, 8366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Arjona, L.P.; Ramírez-Mella, M. Pumpkin waste as livestock feed: Impact on nutrition and animal health and on quality of meat, milk, and egg. Animals (Basel) 2019, 9, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataoka, C.; Nihei, M.; Nimata, M.; Sawadaishi, K. Development of a model immunoassay utilizing monoclonal antibodies of different specificities for quantitative determination of dieldrin and heptachlors in their mixtures. J Agric Food Chem 2016, 64, 8950–8957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretariat of the Stockholm Convention. Overview of the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs); United Nations Environment Programme, 2023. Available online: https://www.pops.int/TheConvention/Overview/tabid/3351/Default.aspx.

- Seike, N.; Otani, T. Relationship between Heptachlor Epoxide Concentration in Pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima) and Soil Concentration Extracted with 50% (v/v) Methanol–Water Solution. J Environ Chem 2019, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF). Revision of pesticide component standards in feed (50th Meeting of the Agricultural Materials Council, Feed Subcommittee), 2019, Document 10:. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/council/sizai/siryou/50/attach/pdf/index-10.pdf.

- Food and Agricultural Materials Inspection Center (FAMIC). Regulatory frameworks to ensure feed safety in Japan, 2022. Available online: https://www.famic.go.jp/ffis/feed/r_safety/r_feeds_safetyj22.html.

- Harradine, I.R.; Mcdougall, K.W. Residues in cattle grazed on land contaminated with heptachlor. Aust Vet J 1986, 63, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.J.; Seneviratna, P. Pesticide residues in Australian meat. Vet Rec 1989, 125, 180–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Food Research Laboratories, Ed. Key Points of Component Analysis for Nutrition Labeling (in Japanese); Chuohoki Publishing, 2007.

- Yasui, A.; Watanabe, T., Eds. Analytical Manual and Commentary for the Standard Tables of Food Composition in Japan 2020 (Eighth Revised Edition) (in Japanese). Japan Food Research Laboratories; Kenpakusha Publishing, 2023.

- Khemarach, S.; Yammuen-art, S.; Punyapornwithaya, V.; Nithithanasilp, S.; Jaipolsaen, N.; Sangsritavong, S. Improved reproductive performance achieved in tropical dairy cows by dietary beta-carotene supplementation. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 23171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Yang, Y.R.; Cheon, H.Y.; Shin, N.H.; Lee, J.W.; Bong, S.H.; Hwangbo, S.; Kong, I.K.; Shin, M.K. Effects of hydrogenated fat-spray-coated β-carotene supplement on plasma β-carotene concentration and conception rate after embryo transfer in Hanwoo beef cows. Animal 2021, 15, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuishi, H.; Natsubori, E.; Otsuka, T.; Yayota, M. High β-carotene concentration in plasma enhances cyclic progesterone production in nonpregnant Japanese Black cows. Anim Sci J 2022, 93, e13782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, G.N.; Fang, X.P.; Zhao, C.; Wu, H.Y.; Lan, Y.X.; Che, L.; Sun, Y.K.; Lv, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.G.; et al. Effects of replacing soybean meal with pumpkin seed cake and dried distillers grains with solubles on milk performance and antioxidant functions in dairy cows. Animal 2021, 15, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkosi, C.Z.; Opoku, A.R.; Terblanche, S.E. In vitro antioxidative activity of pumpkin seed (Cucurbita pepo) protein isolate and its in vivo effect on alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase in acetaminophen-induced liver injury in low protein fed rats. Phytother Res 2006, 20, 780–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenni, A.; Cherif, F.Z.H.; Chenni, K.; Elius, E.E.; Pucci, L.; Yahia, D.A. Effects of pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L.) seed protein on blood pressure, plasma lipids, leptin, adiponectin, and oxidative stress in rats with fructose-induced metabolic syndrome. Prev Nutr Food Sci 2022, 27, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Heptachlor concentrations of pumpkin seed pulp flakes.

Table 1.

Heptachlor concentrations of pumpkin seed pulp flakes.

| Sample No. |

Manufacturing date |

Raw material field |

Heptachlor Concentration (μg/g) |

| 1 |

2023/11/11 |

A・B・C |

0.089 |

| 2 |

2023/11/22 |

A・C・D・E |

0.008 |

| 3 |

2023/12/2 |

A・D・E |

0.100 |

| 4 |

2024/1/9 |

A・D・E・F |

0.069 |

| 5 |

2024/1/20 |

A・D・G |

0.005 |

| 6 |

2024/2/5 |

A・B |

0.015 |

| 7 |

2024/3/7 |

AW* |

0.006 |

| 8 |

2024/3/16 |

AW* |

< 0.002 |

| 9 |

2024/3/20 |

AW* |

< 0.002 |

| 10 |

2024/4/1 |

AW* |

0.004 |

| 11 |

2024/5/9 |

AW* |

0.007 |

Table 2.

β-carotene concentrations of pumpkin seed pulp flakes.

Table 2.

β-carotene concentrations of pumpkin seed pulp flakes.

| Sample No. |

Manufacturing date |

Raw material field |

β-Carotene Concentration (μg/100g) |

| 1 |

2023/11/11 |

A・B・C |

4,800 |

| 2 |

2023/11/22 |

A・C・D・E |

6,900 |

| 3 |

2023/12/2 |

A・D・E |

13,000 |

| 4 |

2024/1/9 |

A・D・E・F |

8,100 |

| 5 |

2024/1/20 |

A・D・G |

7,300 |

| 6 |

2024/2/5 |

A・B |

6,400 |

| 7 |

2024/3/7 |

AW* |

3,800 |

| 8 |

2024/3/16 |

AW* |

6,800 |

| 9 |

2024/3/20 |

AW* |

6,500 |

| 10 |

2024/4/1 |

AW* |

5,500 |

| 11 |

2024/5/9 |

AW* |

9,200 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).