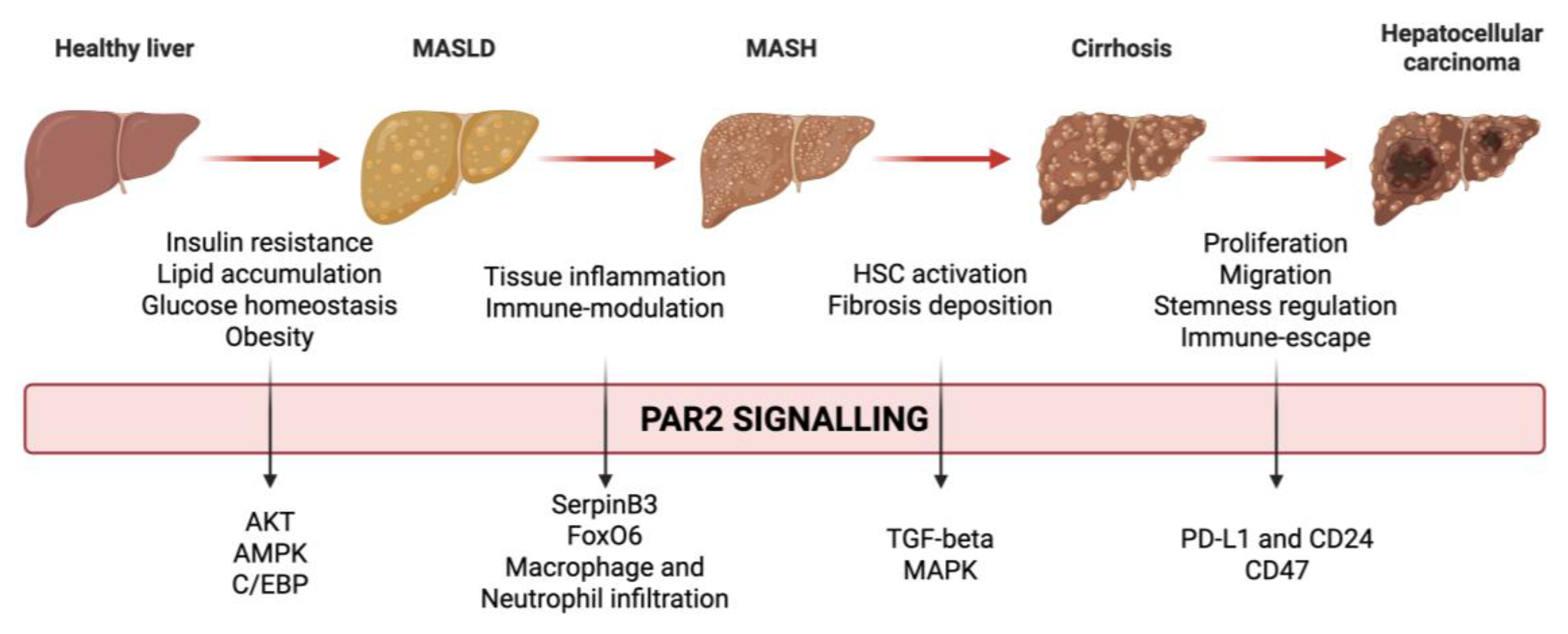

PAR2 and Metabolism

Insulin resistance, a hallmark of type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity, is a central pathogenic mechanism in the development of metabolic dysfunction and hepatic steatosis. Impaired insulin signalling leads to a reduction in protein kinase B (Akt) activation, exacerbating dysregulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. A recent study investigated the role of PAR2 in promoting insulin resistance [

11]. The authors observed an increased expression of PAR2 in hepatocytes from patients with concurrent diabetes and hepatic steatosis. Using a murine model of steatosis and diabetes, they also demonstrated that genetic deletion of PAR2 (PAR2-KO) improved histological markers of steatosis activity and led to a reduction in plasma glucose and insulin levels. These effects were primarily mediated by an increased expression of the glucose transporter GLUT2, which permits glucose uptake and glycogen storage in the hepatocytes. Mechanistically, they showed that PAR2 activation inhibited insulin-Akt signalling, promoting insulin resistance, whereas pharmacological inhibition or genetic silencing of PAR2 restored insulin sensitivity.

The contribution of PAR2 to insulin resistance was also reported in another study where the authors found elevated levels of forkhead transcription factor (FoxO) 6 in insulin-resistant rats [

12]. FoxO6 upregulation was accompanied by increased PAR2 expression. Deletion of FoxO6 improved insulin sensitivity and reduced PAR2 expression. The mechanistic link between FoxO6 and PAR2 was found in IL-1β, a cytokine, induced by FoxO6 signalling, which in turn stimulated PAR2 expression and inhibited insulin signalling.

Insulin resistance promotes lipid uptake, de novo lipogenesis, and lipid storage, ultimately leading to hepatic steatosis. Thus, lipid metabolism represents another critical pathway in the pathogenesis of MASLD. In this context, the role of PAR2 was also evaluated in lipid homeostasis. A recent study observed that hepatic PAR2 expression was elevated in steatotic livers and that patients with high PAR2 levels in the liver had significantly increased plasma LDL cholesterol [

13]. In PAR2-KO mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD), PAR2 deficiency was associated with lower hepatic and plasma cholesterol levels. This effect was mediated by three mechanisms: a) reduced cholesterol synthesis, b) increased hepatic cholesterol uptake and c) enhanced biliary cholesterol excretion, as demonstrated by PCR analysis of gene transcription. Despite unchanged plasma triglyceride levels, PAR2-KO mice exhibited reduced hepatic accumulation of triglyceride and fatty acid. This was accompanied by downregulation of key lipogenic enzymes and upregulation of genes associated with β-oxidation. Mechanistically, the authors proved that PAR2-induced activation of JNK1/2 promoted sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 (SREBP1c) activation and inhibited AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a key regulator of lipid catabolism.

Further evidence supporting the link between PAR2 and AMPK came from Kim et al., who demonstrated that PAR2-KO mice were protected from developing hepatic steatosis when fed on HFD. PAR2-KO mice showed higher AMPK activation

, compared to wild-type controls. Conversely, in vitro, overexpression of PAR2 was associated with AMPK inhibition. The downregulation of AMPK by PAR2 resulted in an impairment of autophagy, contributing to hepatic lipid accumulation [

14].

Badeanlou et al. reported that genetic deletion of PAR2 or tissue factor (TF), which mediates coagulation factor VIIa-induced PAR2 activation, protected mice from developing obesity and insulin resistance when subjected to an HFD [

15]. Furthermore, PAR2 deletion was associated with a reduction in macrophage infiltration in the adipose tissue, supporting the role of PAR2 in the development of tissue inflammation. Interestingly, the researchers uncovered a dual role for PAR2. Specific deletion of PAR2 or TF in non-hematopoietic cells led to a reduction in weight gain. Conversely, deletion of these targets in immune cells did not affect obesity development but led to decreased markers of insulin resistance and inflammation.

Some years later, the same group explored the role of TF–PAR2 signalling in the liver [

16]. Genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of TF, PAR2, or both of them, led to reductions in gluconeogenesis, lipogenesis, and liver inflammation in a murine model of diet-induced obesity. Notably, these beneficial effects were also observed when TF or PAR2 deletion was restricted to hematopoietic cells, further supporting the role of this receptor in the crosstalk between the immune system and target tissue. Interestingly, wild-type (WT) mice fed an HFD exhibited increased hepatic infiltration of CD11b⁺CD11c⁺ macrophages and CD8⁺ lymphocytes

, compared to mice fed a low-fat diet (LFD). Accordingly, TF deletion decreased CD11b⁺CD11c⁺ macrophage infiltration, while PAR2 deletion reduced the CD8⁺ T cell population.

A novel mechanism involving PAR2 in liver disease was recently identified by Villano et al. who demonstrated an interaction between PAR2 and SerpinB3 [

17]. PAR2 activation induced the expression of the transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ), a known regulator of SerpinB3. In turn, SerpinB3, a member of the serine protease inhibitor family, was shown to be essential for PAR2 activation. Importantly, the authors found that PAR2 activity could be effectively inhibited using a small molecule called 1-Piperidine Propionic Acid (1-PPA): treatment with 1-PPA prevented lipid accumulation, inflammation, and liver fibrosis in mice overexpressing SerpinB3. Additionally, it suppressed C/EBPβ expression in both THP-1 and HepG2 cells.

SerpinB3 has been previously implicated in the pathogenesis of steatotic liver disease. In a recent study, due to its involvement in lipid accumulation and inflammation

, it has been proposed as a new

hepatokine [

18]. In this study, two mouse models were used: one overexpressing SerpinB3 (TG/SB3), and the other expressing an isoform lacking its antiprotease activity (KO/SB3). Mice were fed on two different steatogenic diets: methionine–choline-deficient (MCD) or choline-deficient, L-amino acid-defined (CDAA). Overexpression of SerpinB3 resulted in increased hepatic lipid accumulation and inflammation, while loss of its activity conferred protection compared to WT mice. Moreover, TG/SB3 mice exhibited increased hepatic accumulation of crown-like structures formed by macrophages, a characteristic histological feature of steatotic liver disease, mirroring the findings of Wang et al. regarding TF–PAR2 signalling and CD11b⁺CD11c⁺ macrophage recruitment [

16].

PAR2 and Inflammation

The role of PAR2 in regulating inflammation has been investigated in various clinical contexts. Recent evidence has highlighted its involvement in promoting antigen responses during allergic reactions. A recent study demonstrated that inhibition of PAR2 reduces the production of inflammatory cytokines in a model of hypersensitivity [

19]. It has also been shown that PAR2 antagonism effectively reduces airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in a murine model of allergic reaction [

20]. Similar results were obtained in a mouse model of allergen-induced asthma [

21], as well as in vitro [

22].

In line with these findings, our research team recently published a study evaluating the efficacy of PAR2 antagonism using 1-PPA in a murine model of sepsis induced by intraperitoneal injection of lipopolysaccharide [

23]. Treatment with 1-PPA significantly attenuated the inflammatory response and vasodilation, consequently enhancing cardiac function, reducing organ damage and alleviating clinical symptoms, which ultimately led to improved survival rates. The role of PAR2 in the response to microorganisms was also highlighted by Chu et al. who described a novel PAR2-dependent mechanism of neutrophil activation, driving inflammation and giving the rationale for inhibiting this pathway in the treatment of neutrophil-mediated inflammatory disease [

24]. Other evidence demonstrated that PAR2 inhibition can prevent infection by

Candida albicans [

25], and periodontal inflammation induced by

Porphyromonas gingivalis [

26].

Our research team recently published findings on the effects of PAR2 inhibition using 1-PPA in neuroinflammation, demonstrating its efficacy in reducing amyloid deposition and neuroglial inflammation in fibroblasts in patients with Parkinson’s disease [

27]. Consistently, in another study, it has been shown that inhibition of mast cell tryptase effectively reduced PAR2-driven neuroinflammation in a murine model of cardiac arrest [

28].

Several studies have also explored the role of PAR2 in intestinal diseases. It has been reported that a microbiome with high proteolytic activity can trigger colitis via PAR2 activation in mice [

29]. Bacterial proteolytic activation of PAR2 has also been identified as a potential therapeutic target in inflammatory bowel disease [

30] and in mediating both inflammation and pain in colitis [

31]. However, Ke et al. showed that PAR2 deficiency in myeloid-derived suppressor cells enhanced their immunosuppressive activity, suggesting a dual role for this receptor in this context [

32].

Of particular relevance to this review is the link between PAR2, inflammation and metabolism, an interplay that involves not only the liver but also other organs. Ha et al. showed that PAR2-deficient mice were protected from HFD-induced kidney inflammation and injury [

33]. In a subsequent study, the same group demonstrated that PAR2-KO mice were also protected from age-related kidney inflammation and senescence [

34].

Two different studies further demonstrated the efficacy of PAR2 inhibition in preventing LDL-induced vascular damage in models of atherosclerosis, reinforcing the role of this receptor in the crosstalk between metabolism and inflammation [

35,

36].

More recent studies have provided further insights into the complex interaction between the immune system and target organs. Reches et al. addressed this issue by investigating the role of PAR2 in two distinct murine models of liver injury: one immune-mediated (using concanavalin A) and one toxin-induced (with carbon tetrachloride CCL

4). The authors compared wild-type and PAR2 knockout mice and repeated the experiments after bone marrow transplantation between the two strains. Their results demonstrated that PAR2 expression in liver tissue was essential for hepatocyte regeneration after toxic injury, whereas PAR2 expression in immune cells enhanced inflammation and worsened immune-mediated damage [

37].

This dual role of PAR2 was later confirmed by the same group in a model of autoimmune diabetes. In this context, PAR2 expression in pancreatic β-cells was protective against immune damage, while its expression in lymphocytes promoted β-cell destruction and diabetes onset [

38].

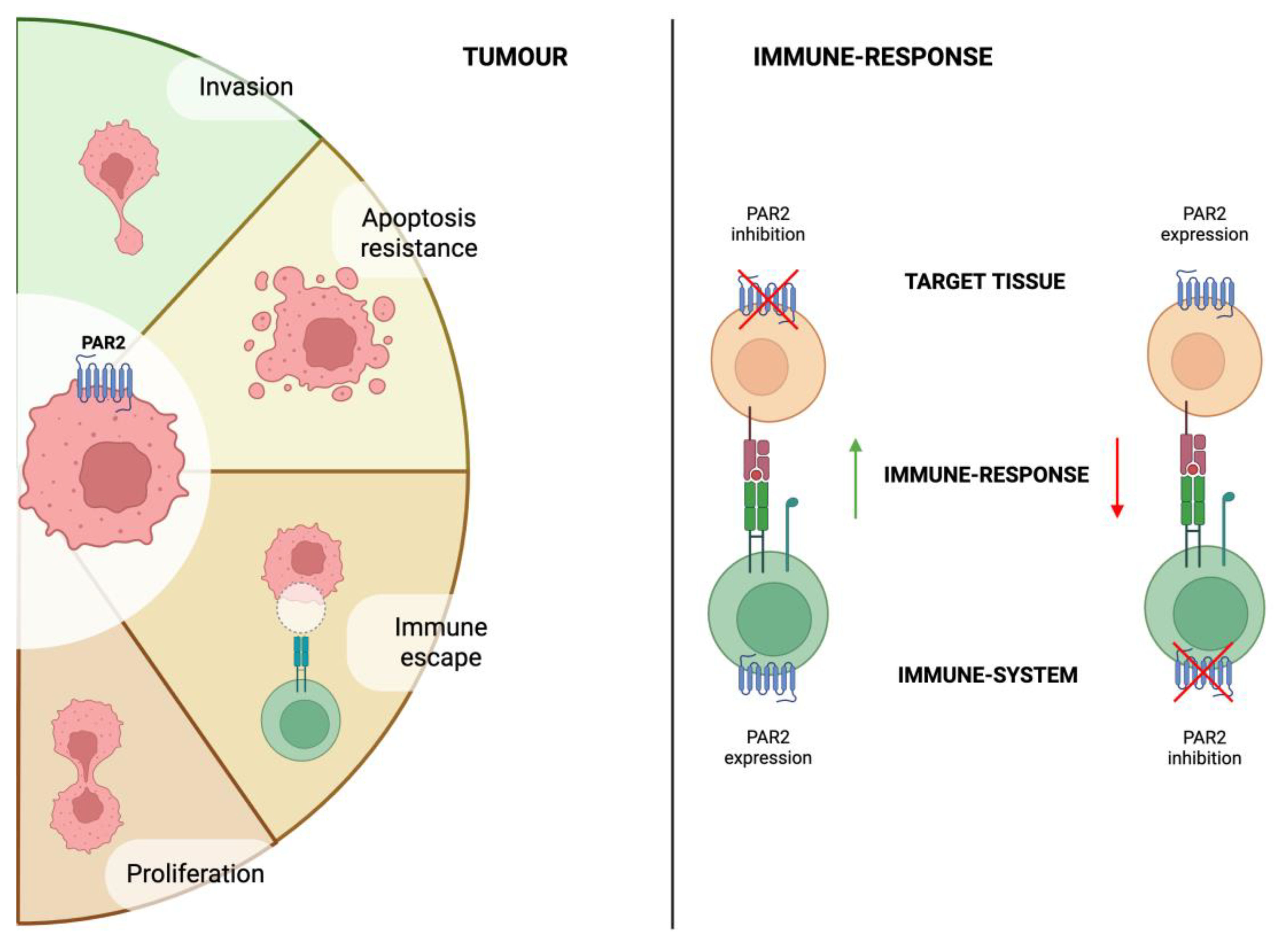

This dichotomous role of PAR2 in immune and target tissues warrants further investigation, particularly given the emerging importance in tumour development of this receptor.

PAR2 and Fibrosis

The importance of PAR2 in regulating the immune response is particularly relevant in liver disease, as chronic inflammation increases the risk of liver fibrosis, eventually leading to cirrhosis. It has been reported that inhibition of PAR2 using the pepducin PZ-235 was effective in preventing liver fibrosis. PZ-235 directly reduced hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation and decreased hepatocyte death, thereby limiting the main stimulus for chronic inflammation [

39].

Other studies have confirmed the involvement of PAR2 in modulating HSC function. Knight et al. showed that PAR2-KO mice were protected from fibrosis induced by CCl₄, a protection associated with reduced expression of TGF-β, the main mediator of fibrogenesis [

40]. In a later study, the same authors investigated the relationship between TF activation and liver fibrosis using three different genetically modified murine models lacking PAR2, the cytoplasmic domain of TF, or both. Deletion of either PAR2 or TF conferred protection against fibrosis, and simultaneous deletion of both did not produce any additive benefit, suggesting that TF-PAR2 signalling is a shared pathway driving fibrosis [

41].

In vitro studies also support this evidence. HSCs upregulated both PAR1 and PAR2 expression when cultured on plastic to promote myofibroblastic phenotype transformation. Stimulation of either receptor increased proliferation and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), while their inhibition had the opposite effect [

42]. Another in vitro study explored the role of PAR2 in apoptosis. Activation-induced cell death, triggered by phorbol myristate acetate, was suppressed by concurrent PAR2 stimulation with tryptase, suggesting a protective anti-apoptotic role of PAR2 in activated HSCs [

43].

The profibrotic activity of PAR2 is not limited to the liver. Tisch et al. recently reported that genetic deletion of PAR2 reduced airway fibrosis following allergen exposure [

44]. Similar protective effects were observed in the kidney, where PAR2KO mice were protected from renal inflammation and fibrosis [

45]. Along the same lines, both PAR2 and PAR1 contribute to kidney injury and fibrosis in a diabetic mouse model [

46].

Additional studies have examined the effects of PAR2 on intestinal fibrosis. Mast cell-derived tryptase activated PAR2 on intestinal fibroblasts, promoting their transition to myofibroblasts and mirroring the findings in hepatic HSCs [

47]. Two additional studies confirmed that PAR2 inhibition protected against intestinal fibrosis [

48,

49].

Collectively, these findings underscore the role of PAR2 in orchestrating immune responses and promoting fibrosis across multiple organ systems [

50]. This has important implications, as sustained inflammation and fibrotic signalling may contribute to tumour development via activation of oncogenic pathways.

PAR2 and Cancer

The role of PAR2 in oncogenesis has been extensively studied. In the liver, PAR2 expression in HSCs promotes HCC growth and angiogenesis in a murine xenograft model, whereas genetic deletion of PAR2 suppresses these effects. Furthermore, PAR2-deficient HSCs exhibited reduced activation following TGF-β stimulation and Hep3B-conditioned medium, indicating that PAR2 expression in HSCs contributes not only to fibrogenesis but also to HCC progression [

51].

Moreover, a recent study showed that high PAR2 expression in HCC tissue samples after radical resection was associated with more aggressive clinical features. Patients with elevated PAR2 levels had larger tumours, more advanced stages, and a higher incidence of microvascular invasion. Building on these findings, the authors demonstrated in two in vitro hepatic cancer cell models that PAR2 overexpression enhanced both proliferation and metastatic potential, while silencing of PAR2 reversed these effects. In vivo, PAR2 silencing reduced the extent of metastatic spread in a mouse model of liver metastasis [

52].

In another study, the authors showed that secreted cathepsin S interacts with PAR2 to regulate the transition of cancer stem cells in HCC. Cathepsin S was secreted by CD47⁺ cells displaying stemness characteristics. Suppression of CD47 reduced HCC cell proliferation, and disruption of the cathepsin S/PAR2 axis increased chemosensitivity, suggesting a role for this pathway in therapy resistance [

53].

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have become the first-line therapy for various cancers. Given its role in modulating immune responses, PAR2 has been investigated in this context.

In a recent study, a novel gene signature predictive of response to immunotherapy across multiple cancer types was identified [

54]. Interestingly, among the genes analysed, PAR2, together with RNA-binding motif protein 9, was associated with poorer response to ICI therapy.

The role of PAR2 in regulating anti-tumour immune responses was further explored in a study on metastatic colorectal cancer [

55]. The authors found that PAR2 expression correlated with reduced macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of malignant cells. This effect was driven by increased expression of the “don’t eat me” signal, CD24. Conversely, neutrophil elastase, which cleaves and inhibits PAR2, downregulated CD24 expression, thereby enhancing phagocytosis. Similar findings were reported also in breast cancer, where activation of PAR2 signalling via coagulation factor VIIa led to reduced phagocytosis in an in vitro model [

56]. Moreover, genetic deletion of PAR2 in vivo resulted in a smaller tumour size. Both studies highlighted a synergistic effect between PAR2 inhibition (whether pharmacological or genetic) and ICI treatment.

Apart from phagocytosis, other authors have focused on the effects of PAR2 in regulating T-cell response. A recent study reported that activation of PAR2 by coagulation factor Xa (FXa) conferred resistance to anoikis in HCC cells, thereby promoting metastasis. FXa-mediated PAR2 activation also increased PD-L1 expression while simultaneously inhibiting CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration into tumours. Inhibition of FXa in vivo resulted in decreased metastasis and downregulation of PD-L1. These effects were further enhanced by concomitant administration of anti–PD-L1 antibodies [

57]. Similar results were reported in the context of breast cancer, where PAR2 activation leads to increased production and stabilization of PD-L1 and a reduction in CD8

+ T cell activity [

58].

These findings suggest that PAR2 expression in cancer cells not only promotes tumour progression and invasion but also suppresses the immune response. On the other hand, as previously reported, PAR2 expression in the immune system may activate immune response (

Figure 2). However, to the best of our knowledge, no study to date has directly investigated the impact of PAR2 activation on immune cells within the tumour microenvironment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, PAR2’s pivotal role in the development and progression of the MASLD spectrum has been extensively investigated given its dual role in regulating metabolism and inflammation, ultimately contributing to tumorigenesis. Current research is increasingly focused on PAR2’s role in modulating the interplay between the immune system and target tissues. This emerging field of study holds particular promise, considering the growing significance of immunotherapy in oncology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: P.G, PP; methodology, P.G, A.M; writing—original draft preparation, P.G.; writing—review and editing, P.P, A.M.; supervision, P.P.

Funding

This review received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MASLD |

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| HCC |

hepatocellular carcinoma |

| PAR2 |

Protease-activated receptor 2 |

| MASH |

metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis |

| HFD |

high-fat diet |

References

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Obes Facts 2024, 17, 374–444. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.A.; Kendall, B.J.; El-Serag, H.B.; Thrift, A.P.; Macdonald, G.A. Hepatocellular and Extrahepatic Cancer Risk in People with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2024, 9, 159–169. [CrossRef]

- Chalasani, N.; Younossi, Z.; Lavine, J.E.; Charlton, M.; Cusi, K.; Rinella, M.; Harrison, S.A.; Brunt, E.M.; Sanyal, A.J. The Diagnosis and Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Practice Guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018, 67, 328–357. [CrossRef]

- Paik, J.M.; Henry, L.; De Avila, L.; Younossi, E.; Racila, A.; Younossi, Z.M. Mortality Related to Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Is Increasing in the United States. Hepatol Commun 2019, 3, 1459–1471. [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Henry, L. Epidemiology of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. JHEP Reports 2021, 3, 100305. [CrossRef]

- Piscaglia, F.; Svegliati-Baroni, G.; Barchetti, A.; Pecorelli, A.; Marinelli, S.; Tiribelli, C.; Bellentani, S.; on behalf of the HCC-NAFLD Italian Study Group Clinical Patterns of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Multicenter Prospective Study. Hepatology 2016, 63, 827–838. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Gong, G.; Ben, Q.; Qiu, W.; Chen, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, L. Increased Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies. Intl Journal of Cancer 2012, 130, 1639–1648. [CrossRef]

- Anstee, Q.M.; Reeves, H.L.; Kotsiliti, E.; Govaere, O.; Heikenwalder, M. From NASH to HCC: Current Concepts and Future Challenges. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, 16, 411–428. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Dong, B. Molecular Mechanisms in MASLD/MASH-Related HCC. Hepatology 2024. [CrossRef]

- Villano, G.; Pontisso, P. Protease Activated Receptor 2 as a Novel Druggable Target for the Treatment of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease and Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1397441. [CrossRef]

- Shearer, A.M.; Wang, Y.; Fletcher, E.K.; Rana, R.; Michael, E.S.; Nguyen, N.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Covic, L.; Kuliopulos, A. PAR2 Promotes Impaired Glucose Uptake and Insulin Resistance in NAFLD through GLUT2 and Akt Interference. Hepatology 2022, 76, 1778–1793. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Lee, B.; Lee, J.; Kim, M.E.; Lee, J.S.; Chung, J.H.; Yu, B.P.; Dong, H.H.; Chung, H.Y. FoxO6-Mediated IL-1β Induces Hepatic Insulin Resistance and Age-Related Inflammation via the TF/PAR2 Pathway in Aging and Diabetic Mice. Redox Biology 2019, 24, 101184. [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; Shearer, A.M.; Fletcher, E.K.; Nguyen, N.; Guha, S.; Cox, D.H.; Abdelmalek, M.; Wang, Y.; Baleja, J.D.; Covic, L.; et al. PAR2 Controls Cholesterol Homeostasis and Lipid Metabolism in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Molecular Metabolism 2019, 29, 99–113. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.M.; Kim, D.H.; Park, Y.J.; Ha, S.; Choi, Y.J.; Yu, H.S.; Chung, K.W.; Chung, H.Y. PAR2 Promotes High-Fat Diet-Induced Hepatic Steatosis by Inhibiting AMPK-Mediated Autophagy. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2021, 95, 108769. [CrossRef]

- Badeanlou, L.; Furlan-Freguia, C.; Yang, G.; Ruf, W.; Samad, F. Tissue Factor–Protease-Activated Receptor 2 Signaling Promotes Diet-Induced Obesity and Adipose Inflammation. Nat Med 2011, 17, 1490–1497. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chakrabarty, S.; Bui, Q.; Ruf, W.; Samad, F. Hematopoietic Tissue Factor–Protease-Activated Receptor 2 Signaling Promotes Hepatic Inflammation and Contributes to Pathways of Gluconeogenesis and Steatosis in Obese Mice. The American Journal of Pathology 2015, 185, 524–535. [CrossRef]

- Villano, G.; Novo, E.; Turato, C.; Quarta, S.; Ruvoletto, M.; Biasiolo, A.; Protopapa, F.; Chinellato, M.; Martini, A.; Trevellin, E.; et al. The Protease Activated Receptor 2 - CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein Beta - SerpinB3 Axis Inhibition as a Novel Strategy for the Treatment of Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Molecular Metabolism 2024, 81, 101889. [CrossRef]

- Novo, E.; Cappon, A.; Villano, G.; Quarta, S.; Cannito, S.; Bocca, C.; Turato, C.; Guido, M.; Maggiora, M.; Protopapa, F.; et al. SerpinB3 as a Pro-Inflammatory Mediator in the Progression of Experimental Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 910526. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Yu, S.-J.; Tsai, J.-J.; Yu, C.-H.; Liao, E.-C. Antagonism of Protease Activated Receptor-2 by GB88 Reduces Inflammation Triggered by Protease Allergen Tyr-P3. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 557433. [CrossRef]

- Schiff, H.V.; Rivas, C.M.; Pederson, W.P.; Sandoval, E.; Gillman, S.; Prisco, J.; Kume, M.; Dussor, G.; Vagner, J.; Ledford, J.G.; et al. β-Arrestin-biased Proteinase-activated Receptor-2 Antagonist C781 Limits Allergen-induced Airway Hyperresponsiveness and Inflammation. British J Pharmacology 2023, 180, 667–680. [CrossRef]

- De Matos, N.A.; Lima, O.C.O.; Da Silva, J.F.; Piñeros, A.R.; Tavares, J.C.; Lemos, V.S.; Alves-Filho, J.C.; Klein, A. Blockade of Protease-Activated Receptor 2 Attenuates Allergen-Mediated Acute Lung Inflammation and Leukocyte Recruitment in Mice. J Biosci 2022, 47, 2. [CrossRef]

- Rivas, C.M.; Schiff, H.V.; Moutal, A.; Khanna, R.; Kiela, P.R.; Dussor, G.; Price, T.J.; Vagner, J.; DeFea, K.A.; Boitano, S. Alternaria Alternata-Induced Airway Epithelial Signaling and Inflammatory Responses via Protease-Activated Receptor-2 Expression. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2022, 591, 13–19. [CrossRef]

- Luisetto, R.; Scarpa, M.; Villano, G.; Martini, A.; Quarta, S.; Ruvoletto, M.; Guerra, P.; Scarpa, M.; Chinellato, M.; Biasiolo, A.; et al. 1-Piperidine Propionic Acid Protects from Septic Shock Through Protease Receptor 2 Inhibition. IJMS 2024, 25, 11662. [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.-Y.; Zheng-Gérard, C.; Huang, K.-Y.; Chang, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-W.; I, K.-Y.; Lo, Y.-L.; Chiang, N.-Y.; Chen, H.-Y.; Stacey, M.; et al. GPR97 Triggers Inflammatory Processes in Human Neutrophils via a Macromolecular Complex Upstream of PAR2 Activation. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 6385. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Rojas, I.G.; Edgerton, M. Candida Albicans Sap6 Initiates Oral Mucosal Inflammation via the Protease Activated Receptor PAR2. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 912748. [CrossRef]

- Francis, N.; Sanaei, R.; Ayodele, B.A.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.M.; Fairlie, D.P.; Wijeyewickrema, L.C.; Pike, R.N.; Mackie, E.J.; Pagel, C.N. Effect of a Protease-activated Receptor-2 Antagonist (GB88) on Inflammation-related Loss of Alveolar Bone in Periodontal Disease. J of Periodontal Research 2023, 58, 544–552. [CrossRef]

- Quarta, S.; Sandre, M.; Ruvoletto, M.; Campagnolo, M.; Emmi, A.; Biasiolo, A.; Pontisso, P.; Antonini, A. Inhibition of Protease-Activated Receptor-2 Activation in Parkinson’s Disease Using 1-Piperidin Propionic Acid. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1623. [CrossRef]

- Ocak, U.; Eser Ocak, P.; Huang, L.; Xu, W.; Zuo, Y.; Li, P.; Gamdzyk, M.; Zuo, G.; Mo, J.; Zhang, G.; et al. Inhibition of Mast Cell Tryptase Attenuates Neuroinflammation via PAR-2/P38/NFκB Pathway Following Asphyxial Cardiac Arrest in Rats. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 144. [CrossRef]

- Santiago, A.; Hann, A.; Constante, M.; Rahmani, S.; Libertucci, J.; Jackson, K.; Rueda, G.; Rossi, L.; Ramachandran, R.; Ruf, W.; et al. Crohn’s Disease Proteolytic Microbiota Enhances Inflammation through PAR2 Pathway in Gnotobiotic Mice. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2205425. [CrossRef]

- Rondeau, L.E.; Da Luz, B.B.; Santiago, A.; Bermudez-Brito, M.; Hann, A.; De Palma, G.; Jury, J.; Wang, X.; Verdu, E.F.; Galipeau, H.J.; et al. Proteolytic Bacteria Expansion during Colitis Amplifies Inflammation through Cleavage of the External Domain of PAR2. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2387857. [CrossRef]

- Latorre, R.; Hegron, A.; Peach, C.J.; Teng, S.; Tonello, R.; Retamal, J.S.; Klein-Cloud, R.; Bok, D.; Jensen, D.D.; Gottesman-Katz, L.; et al. Mice Expressing Fluorescent PAR2 Reveal That Endocytosis Mediates Colonic Inflammation and Pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2022, 119, e2112059119. [CrossRef]

- Ke, Z.; Wang, C.; Wu, T.; Wang, W.; Yang, Y.; Dai, Y. PAR2 Deficiency Enhances Myeloid Cell-Mediated Immunosuppression and Promotes Colitis-Associated Tumorigenesis. Cancer Letters 2020, 469, 437–446. [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Yang, Y.; Kim, B.M.; Kim, J.; Son, M.; Kim, D.; Yu, H.S.; Im, D.; Chung, H.Y.; Chung, K.W. Activation of PAR2 Promotes High-Fat Diet-Induced Renal Injury by Inducing Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2022, 1868, 166474. [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, B.M.; Kim, J.; Son, M.; Kim, D.; Kim, M.; Yoo, J.; Yu, H.S.; et al. PAR2-mediated Cellular Senescence Promotes Inflammation and Fibrosis in Aging and Chronic Kidney Disease. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14184. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Gai, J.; Shi, S.; Zhao, J.; Bai, X.; Liu, B.; Li, X. Protease-Activated Receptor 2 (PAR-2) Antagonist AZ3451 Mitigates Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein (Ox-LDL)-Induced Damage and Endothelial Inflammation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 34, 2202–2208. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, M.; Liu, G.; Song, Ch.; Yang, M.; Cao, Z.; Zheng, M. Silencing Protease-Activated Receptor 2 Alleviates Ox-LDL-Induced Lipid Accumulation, Inflammation, and Apoptosis via Activation of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. gpb 2020, 39, 437–448. [CrossRef]

- Reches, G.; Blondheim Shraga, N.R.; Carrette, F.; Malka, A.; Saleev, N.; Gubbay, Y.; Ertracht, O.; Haviv, I.; Bradley, L.M.; Levine, F.; et al. Resolving the Conflicts around Par2 Opposing Roles in Regeneration by Comparing Immune-Mediated and Toxic-Induced Injuries. Inflamm Regener 2022, 42, 52. [CrossRef]

- Reches, G.; Khoon, L.; Ghanayiem, N.; Malka, A.; Piran, R. Controlling Autoimmune Diabetes Onset by Targeting Protease-Activated Receptor 2. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 175, 116622. [CrossRef]

- Shearer, A.M.; Rana, R.; Austin, K.; Baleja, J.D.; Nguyen, N.; Bohm, A.; Covic, L.; Kuliopulos, A. Targeting Liver Fibrosis with a Cell-Penetrating Protease-Activated Receptor-2 (PAR2) Pepducin. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2016, 291, 23188–23198. [CrossRef]

- Knight, V.; Tchongue, J.; Lourensz, D.; Tipping, P.; Sievert, W. Protease-Activated Receptor 2 Promotes Experimental Liver Fibrosis in Mice and Activates Human Hepatic Stellate Cells. Hepatology 2012, 55, 879–887. [CrossRef]

- Knight, V.; Lourensz, D.; Tchongue, J.; Correia, J.; Tipping, P.; Sievert, W. Cytoplasmic Domain of Tissue Factor Promotes Liver Fibrosis in Mice. WJG 2017, 23, 5692. [CrossRef]

- Gaça, M.D.A.; Zhou, X.; Benyon, R.C. Regulation of Hepatic Stellate Cell Proliferation and Collagen Synthesis by Proteinase-Activated Receptors. Journal of Hepatology 2002, 36, 362–369. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cai, W.; Shen, F.; Feng, Z.; Zhu, G.; Cao, J.; Xu, B. Protease-Activated Receptor-2 Modulates Hepatic Stellate Cell Collagen Release and Apoptotic Status. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2014, 545, 162–166. [CrossRef]

- Tisch, L.J.; Bartone, R.D.; Antoniak, S.; Bonner, J.C. Protease-Activated Receptor-2 (PAR2) Mutation Attenuates Airway Fibrosis in Mice during the Exacerbation of House Dust Mite-induced Allergic Lung Disease by Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes. Respir Res 2025, 26, 90. [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Chung, K.W.; Lee, J.; Chung, H.Y.; Moon, H.R. Renal Tubular PAR2 Promotes Interstitial Fibrosis by Increasing Inflammatory Responses and EMT Process. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2022, 45, 159–173. [CrossRef]

- Mitsui, S.; Oe, Y.; Sekimoto, A.; Sato, E.; Hashizume, Y.; Yamakage, S.; Kumakura, S.; Sato, H.; Ito, S.; Takahashi, N. Dual Blockade of Protease-Activated Receptor 1 and 2 Additively Ameliorates Diabetic Kidney Disease. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2020, 318, F1067–F1073. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yang, M.-Q.; Yu, T.-Y.; Yin, Y.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.-D.; He, Z.-G.; Yin, L.; Chen, C.-Q.; Li, J.-Y. Mast Cell Tryptase Promotes Inflammatory Bowel Disease–Induced Intestinal Fibrosis. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2021, 27, 242–255. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, Q.; Yu, L.; Zhang, S. Naringin Alleviates Intestinal Fibrosis by Inhibiting ER Stress–Induced PAR2 Activation. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2024, 30, 1946–1956. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Fontenot, L.; Chupina Estrada, A.; Nelson, B.; Wang, J.; Shih, D.Q.; Ho, W.; Mattai, S.A.; Rieder, F.; Jensen, D.D.; et al. Elafin Reverses Intestinal Fibrosis by Inhibiting Cathepsin S-Mediated Protease-Activated Receptor 2. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2022, 14, 841–876. [CrossRef]

- Guerra, P.; Martini, A.; Pontisso, P.; Angeli, P. Novel Molecular Targets for Immune Surveillance of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 3629. [CrossRef]

- Mußbach, F.; Ungefroren, H.; Günther, B.; Katenkamp, K.; Henklein, P.; Westermann, M.; Settmacher, U.; Lenk, L.; Sebens, S.; Müller, J.P.; et al. Proteinase-Activated Receptor 2 (PAR2) in Hepatic Stellate Cells – Evidence for a Role in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Growth in Vivo. Mol Cancer 2016, 15, 54. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Li, P.-B.; Yao, Y.-F.; Xiu, A.-Y.; Peng, Z.; Bai, Y.-H.; Gao, Y.-J. Proteinase-Activated Receptor 2 Promotes Tumor Cell Proliferation and Metastasis by Inducing Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Predicts Poor Prognosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. WJG 2018, 24, 1120–1133. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.K.-W.; Cheung, V.C.-H.; Lu, P.; Lau, E.Y.T.; Ma, S.; Tang, K.H.; Tong, M.; Lo, J.; Ng, I.O.L. Blockade of Cd47-Mediated Cathepsin S/Protease-Activated Receptor 2 Signaling Provides a Therapeutic Target for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology 2014, 60, 179–191. [CrossRef]

- Bareche, Y.; Kelly, D.; Abbas-Aghababazadeh, F.; Nakano, M.; Esfahani, P.N.; Tkachuk, D.; Mohammad, H.; Samstein, R.; Lee, C.-H.; Morris, L.G.T.; et al. Leveraging Big Data of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Response Identifies Novel Potential Targets. Annals of Oncology 2022, 33, 1304–1317. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, J.; Ma, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, X.; Chen, K.; Zhang, X.; et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Impede Cancer Metastatic Seeding via Protease-Activated Receptor 2-Mediated Downregulation of Phagocytic Checkpoint CD24. J Immunother Cancer 2025, 13, e010813. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Bhoumick, A.; Paul, S.; Chatterjee, A.; Mandal, S.; Basu, A.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Das, K.; Sen, P. FVIIa-PAR2 Signaling Facilitates Immune Escape by Reducing Phagocytic Potential of Macrophages in Breast Cancer. J Thromb Haemost 2025, 23, 903–920. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, L.; Wang, B.; Hu, J.; Yu, Y.; Gu, B.; Xiang, L.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, T.; et al. FXa-Mediated PAR-2 Promotes the Efficacy of Immunotherapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma through Immune Escape and Anoikis Resistance by Inducing PD-L1 Transcription. J Immunother Cancer 2024, 12, e009565. [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Das, K.; Ghosh, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Bhoumick, A.; Basu, A.; Sen, P. Coagulation Factor VIIa Enhances Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Expression and Its Stability in Breast Cancer Cells to Promote Breast Cancer Immune Evasion. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2023, 21, 3522–3538. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).