Submitted:

19 June 2025

Posted:

19 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Drug Preparation

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Cell Viability Assays

2.4. Synergy Analysis

2.5. Analysis of ROS Production

2.6. Flow Cytometry Analyses of the Apoptotic Profiles

2.7. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS)-Driven Bottom-Up Proteomics Analysis

2.7.1. Cell Culture, Treatment, and Protein Extraction

2.7.2. Protein Quantification

2.7.3. Peptides Preparation and Clean-Up

2.7.4. Label-Free Quantitative Proteomics Using Micro-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Quadruple Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (Micro-HPLC-QTOF-MS)

Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry Setup

Mass Spectrometry Acquisition Parameters

Mass Calibration and Library Generation

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Data Availability

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Antiproliferative Activity of the Seven Postbiotics Against the HKB-11 (BL) Human Cell Line

3.2. The synergy of N with UB Against the HKB-11 Lymphoma Cells

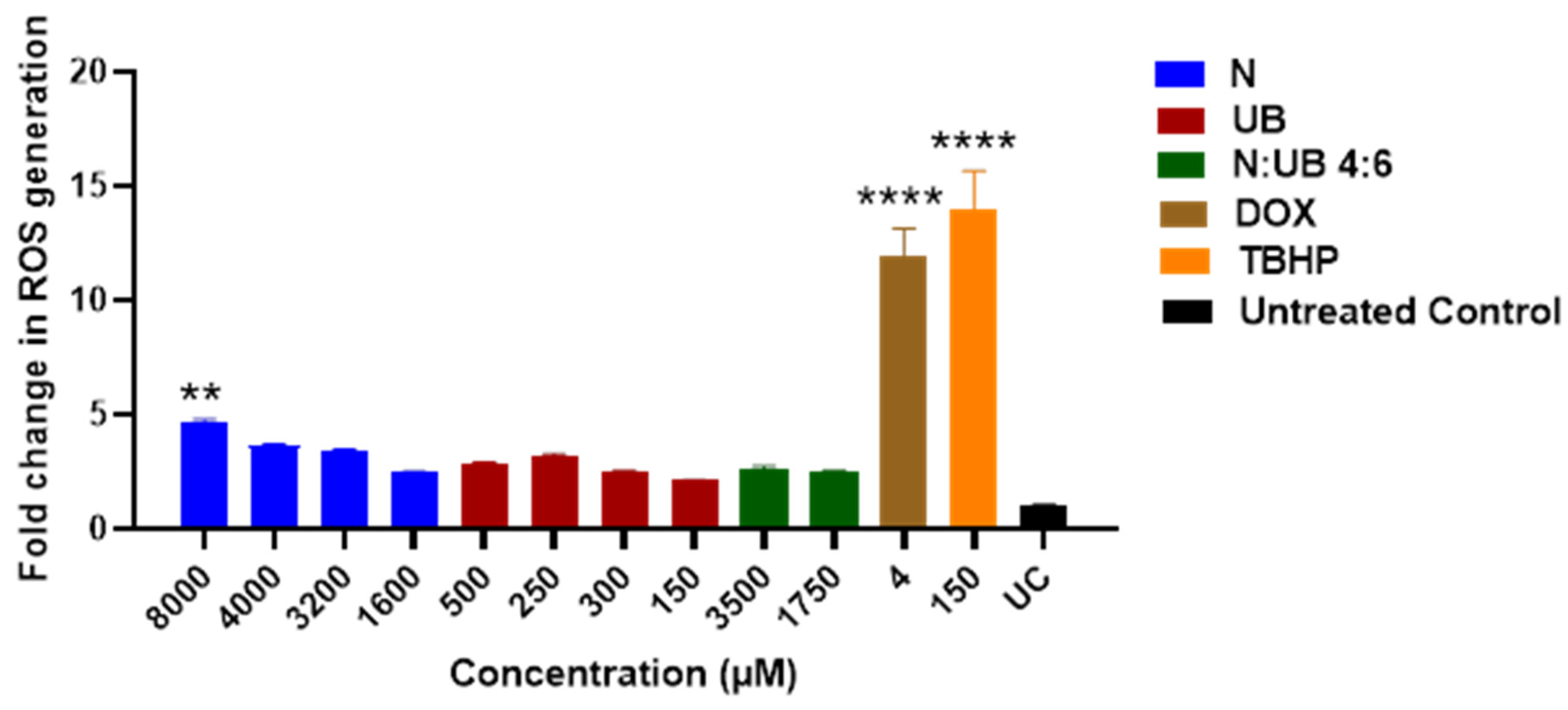

3.3. ROS Production in the HKB-11 Lymphoma Cells After Treatment with Different Concentrations of N, UB and N: UB (4:6)

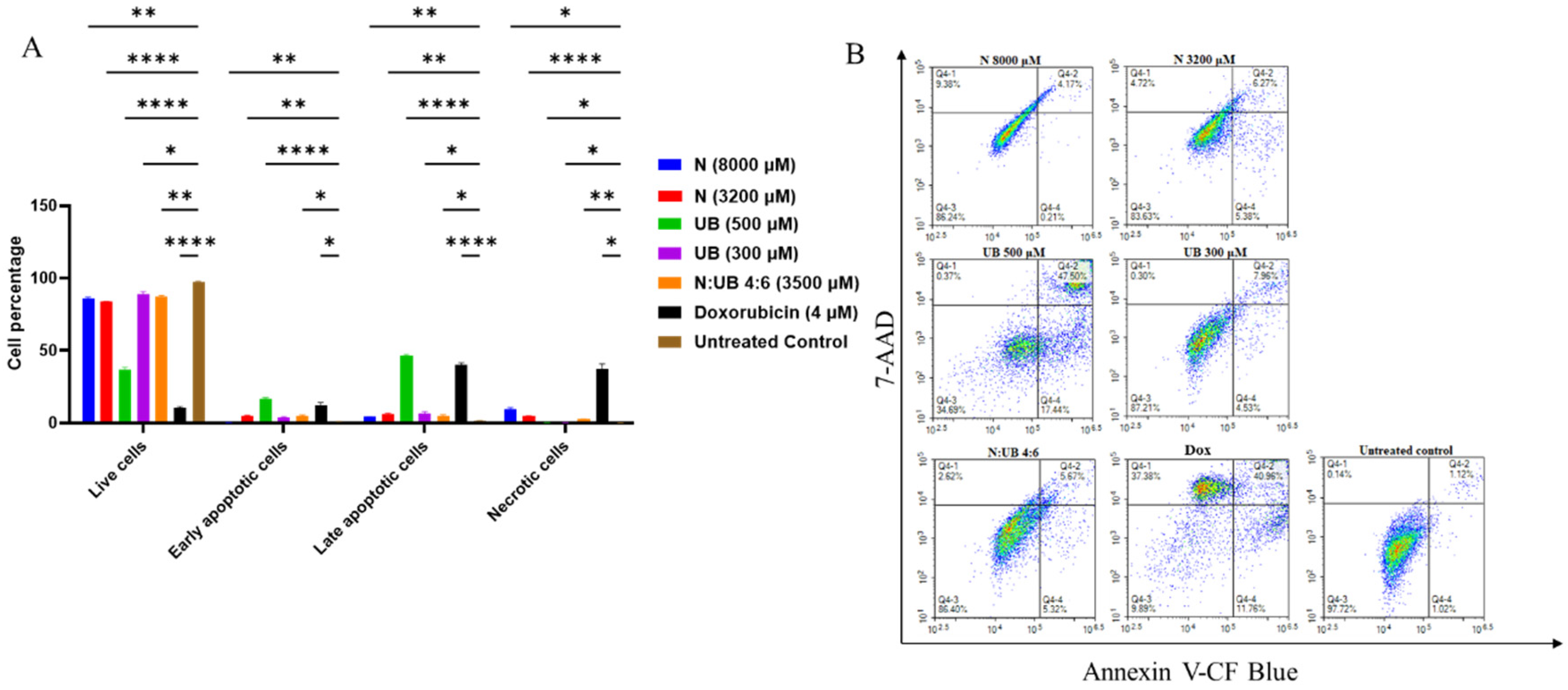

3.4. Flow Cytometric Analyses of Apoptotic Profiles of HKB-11 Lymphoma Cells After Treatment with Different Concentrations of N, UB and N: UB (4:6)

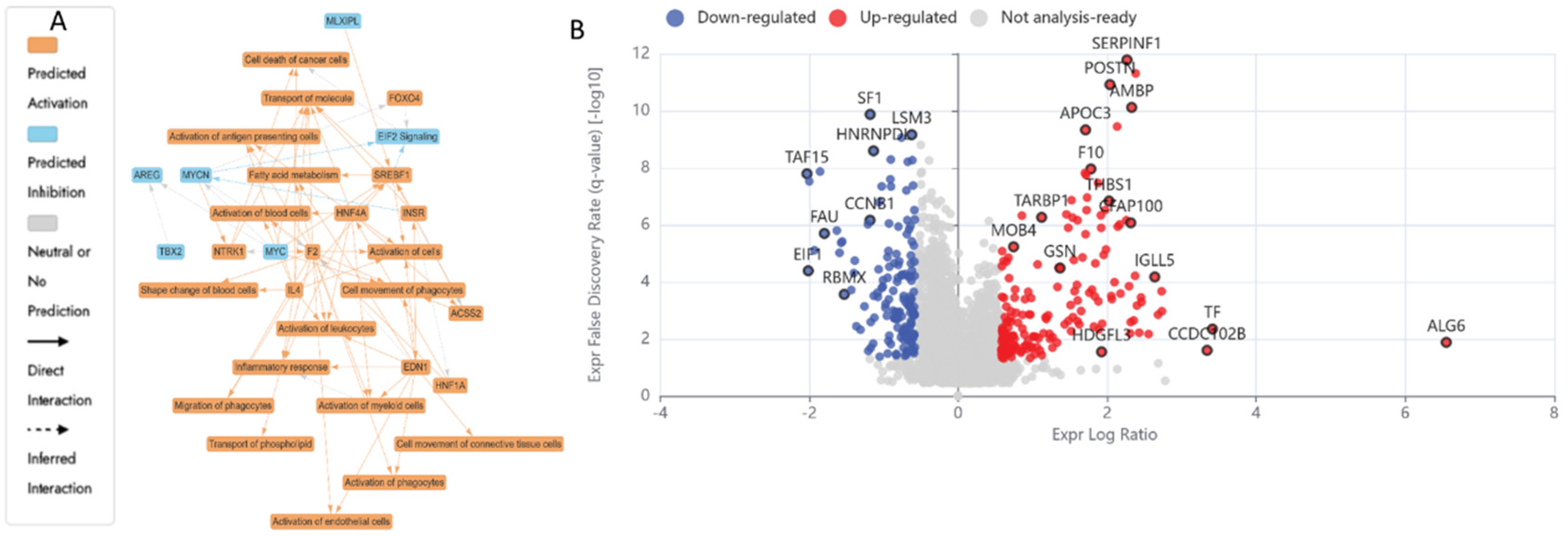

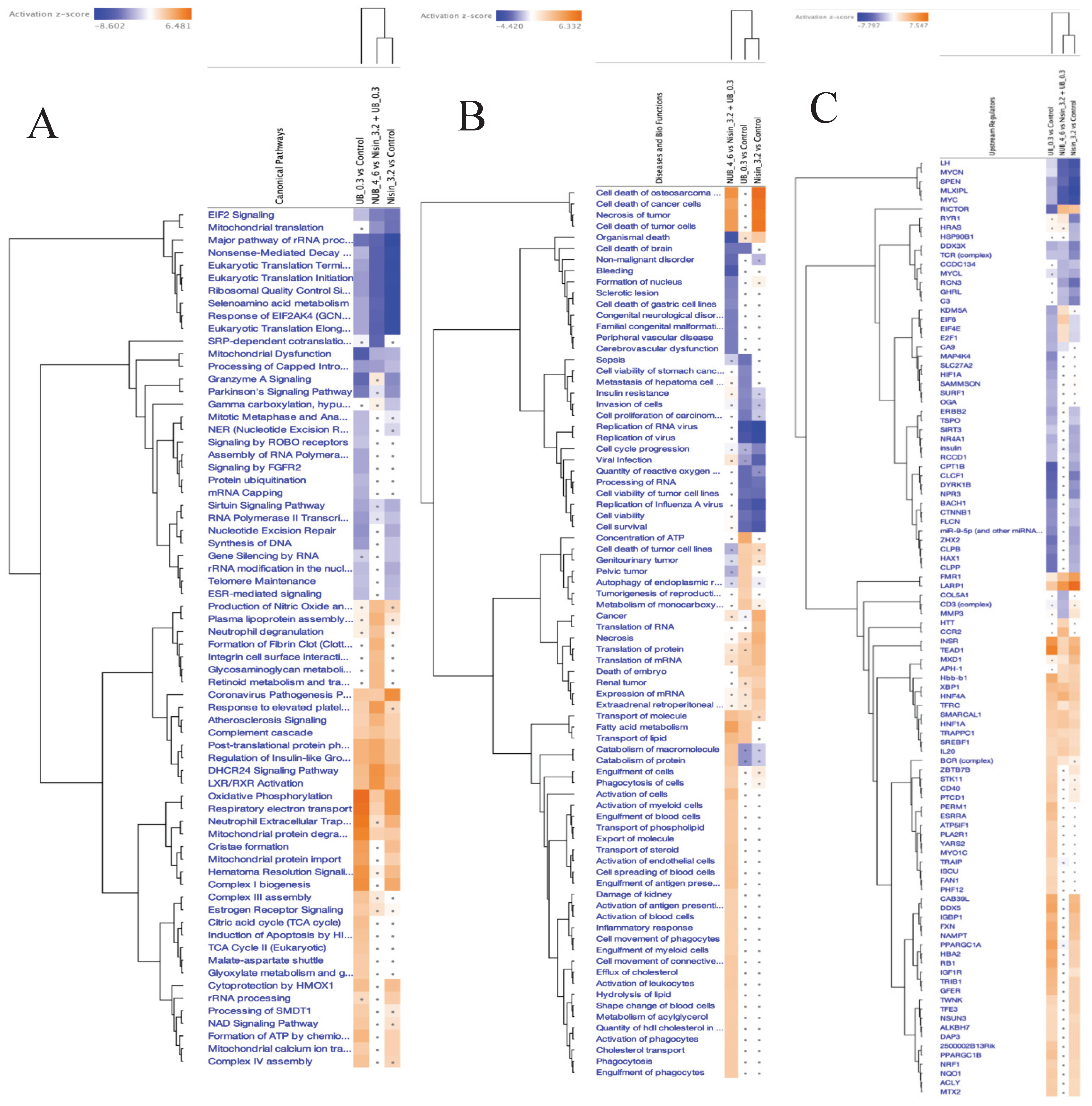

3.5. Proteomics Study of the HKB-11 Lymphoma Cells Treated with the Synergistic Combination vs. Mono Treatments

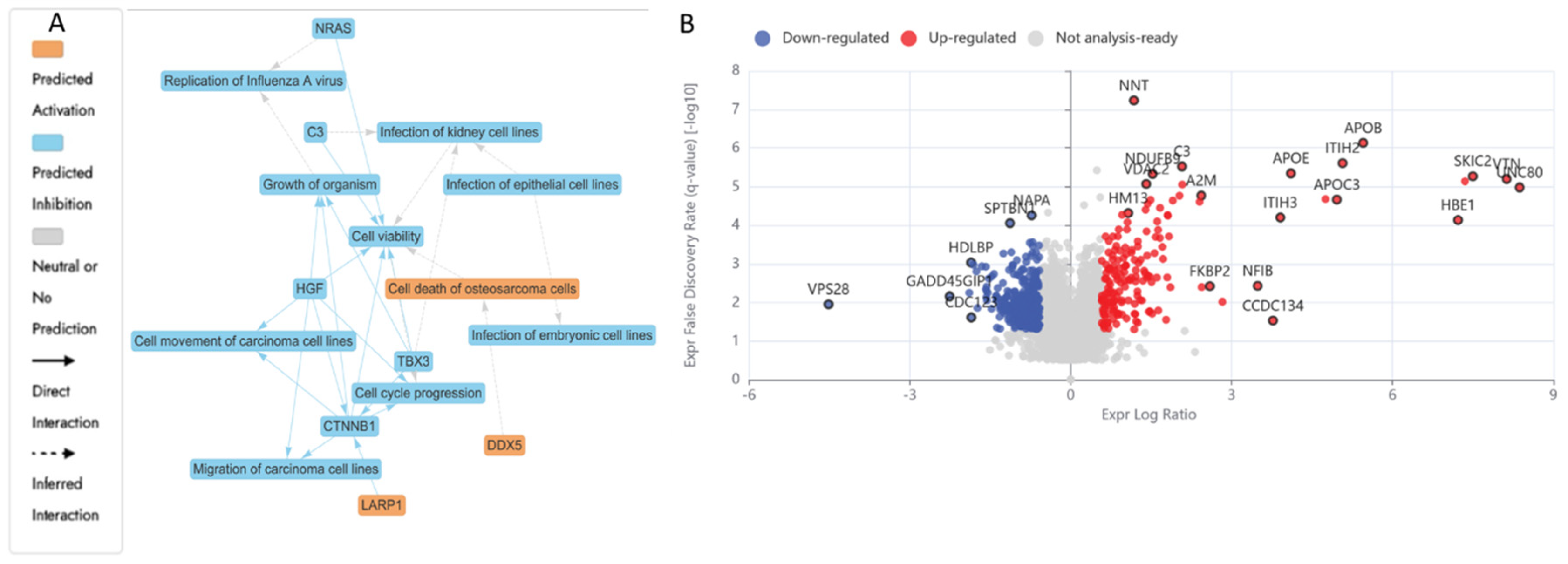

3.5.1. Differentially Expressed Proteins (DEPs) in N (3200 µM) Treated HKB-11 Lymphoma Cells Compared to Untreated Control (abs log2FC ≥ 0.58 and Q ≤ 0.05)

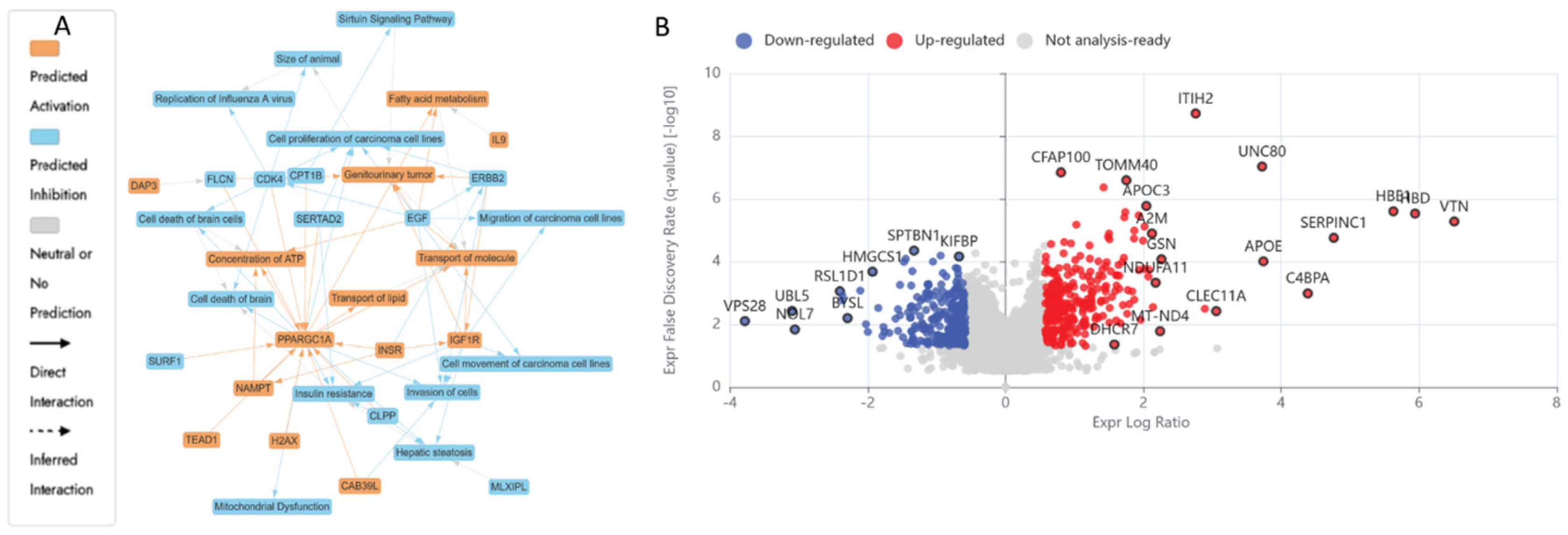

3.5.2. Differentially Expressed Proteins (DEPs) in UB (300 µM) Treated HKB-11 Lymphoma Cells Compared to Untreated Control (abs log2FC > 0.58 and Q < 0.05)

3.5.3. Differentially Expressed Proteins (DEPs) in Combo N:UB (4:6) Treated HBK-11 Cells vs Mono Treatments (N 3200 µM and UB 300 µM) (abs log2FC ≥ 0.58 and Q ≤ 0.05)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, S. S. T. S., Abdulrahman, Z. F. A., & Othman, R. T. (2023). Anticancer activity of cloned Nisin as an alternative therapy for MCF-7 brest cancer cell line. Cellular and Molecular Biology, 69(9), 149-155. [CrossRef]

- Al-Khazaleh, A. K., Chang, D., Münch, G. W., & Bhuyan, D. J. (2024). The Gut Connection: Exploring the Possibility of Implementing Gut Microbial Metabolites in Lymphoma Treatment. Cancers, 16(8), 1464. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/16/8/1464. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, E. T., & Gilmour, S. K. (2022). Immunomodulatory role of thrombin in cancer progression. Molecular Carcinogenesis, 61(6), 527-536. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsherbiny, M. A., Bhuyan, D. J., Low, M. N., Chang, D., & Li, C. G. (2021). Synergistic interactions of cannabidiol with chemotherapeutic drugs in mcf7 cells: Mode of interaction and proteomics analysis of mechanisms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(18), 10103. [CrossRef]

- Alsofyani, A. A., & Nedjadi, T. (2023). Gelsolin, an actin-binding protein: bioinformatic analysis and functional significance in urothelial bladder carcinoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(21), 15763. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansell, S. M. (2015). Non-Hodgkin lymphoma: diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clinic Proceedings,.

- Bano, D., Dinsdale, D., Cabrera-Socorro, A., Maida, S., Lambacher, N., McColl, B., Ferrando-May, E., Hengartner, M., & Nicotera, P. (2010). Alteration of the nuclear pore complex in Ca2+-mediated cell death. Cell Death & Differentiation, 17(1), 119-133.

- Bao, Y., Ni, Y., Zhang, A., & Chen, J. (2024). PPP1R14B as a potential biomarker for the identification of diagnosis and prognosis affecting tumor immunity, proliferation and migration in prostate cancer. Journal of Cancer, 15(20), 6545. [CrossRef]

- Bates, M., Furlong, F., Gallagher, M. F., Spillane, C. D., McCann, A., O’Toole, S., & O’Leary, J. J. (2020). Too MAD or not MAD enough: The duplicitous role of the spindle assembly checkpoint protein MAD2 in cancer. Cancer Letters, 469, 11-21. [CrossRef]

- Berni Canani, R., Di Costanzo, M., & Leone, L. (2012). The epigenetic effects of butyrate: potential therapeutic implications for clinical practice. Clinical epigenetics, 4, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M. I., & Kapila, R. (2017). Dietary metabolites derived from gut microbiota: critical modulators of epigenetic changes in mammals. Nutrition reviews, 75(5), 374-389. [CrossRef]

- Bhutia, S. K., Naik, P. P., Panigrahi, D. P., Bhol, C. S., & Mahapatra, K. K. (2019). Mitophagy, Diseases, and Aging. Models, Molecules and Mechanisms in Biogerontology: Physiological Abnormalities, Diseases and Interventions, 177-191.

- Bionaz, M., Thering, B. J., & Loor, J. J. (2012). Fine metabolic regulation in ruminants via nutrient–gene interactions: saturated long-chain fatty acids increase expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism and immune response partly through PPAR-α activation. British Journal of Nutrition, 107(2), 179-191. [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny, M. V. (2006). Target for cancer therapy: proliferating cells or stem cells. Leukemia, 20(3), 385-391. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blom, A. M., Villoutreix, B. O., & Dahlbäck, B. (2004). Complement inhibitor C4b-binding protein—friend or foe in the innate immune system? Molecular immunology, 40(18), 1333-1346. [CrossRef]

- Brandão, S. R., Carvalho, F., Amado, F., Ferreira, R., & Costa, V. M. (2022). Insights on the molecular targets of cardiotoxicity induced by anticancer drugs: A systematic review based on proteomic findings. Metabolism, 134, 155250. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C., Liu, P., Duan, X., Cheng, M., & Xu, L. X. (2019). Deferoxamine-induced high expression of TfR1 and DMT1 enhanced iron uptake in triple-negative breast cancer cells by activating IL-6/PI3K/AKT pathway. OncoTargets and therapy, 4359-4377.

- Chen, P.-J., Huang, C., Meng, X.-M., & Li, J. (2015). Epigenetic modifications by histone deacetylases: Biological implications and therapeutic potential in liver fibrosis. Biochimie, 116, 61-69. [CrossRef]

- Cho, M. S., Yee, H., & Chan, S. (2002). Establishment of a human somatic hybrid cell line for recombinant protein production. Journal of Biomedical Science, 9(6), 631-638. [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.-C., & Talalay, P. (1984). Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Advances in enzyme regulation, 22, 27-55. [CrossRef]

- Ciciarello, M., Mangiacasale, R., & Lavia, P. (2007). Spatial control of mitosis by the GTPase Ran. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 64, 1891-1914.

- Conaty, L. D. (2013). The effects of sodium butyrate on Hox gene expression in a human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line, HT29 East Carolina University].

- Costa e Silva, L., dos Santos, M. H., Heluy, T. R., Biaggio, R. T., Ferreira, A. R., Milhomens, J., Kashima, S., El Nemer, W., El Hoss, S., & Picanço-Castro, V. (2020). Serum-free suspension cultured human cells can produce a high-level of recombinant human erythropoietin. Engineering Reports, 2(6), e12172. [CrossRef]

- Cramer, P. (2004). Structure and function of RNA polymerase II. Advances in protein chemistry, 67, 1-42.

- Cui, J., Lian, Y., Zhao, C., Du, H., Han, Y., Gao, W., Xiao, H., & Zheng, J. (2019). Dietary fibers from fruits and vegetables and their health benefits via modulation of gut microbiota. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 18(5), 1514-1532. [CrossRef]

- D’Arca, D., Severi, L., Ferrari, S., Dozza, L., Marverti, G., Magni, F., Chinello, C., Pagani, L., Tagliazucchi, L., & Villani, M. (2023). Serum mass spectrometry proteomics and protein set identification in response to FOLFOX-4 in drug-resistant ovarian carcinoma. Cancers, 15(2), 412.

- D’arcy, M. S. (2019). Cell death: a review of the major forms of apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Cell biology international, 43(6), 582-592.

- Dang, V. B., Alsherbiny, M. A., Lin, R., Gao, Y., Li, C., & Bhuyan, D. J. (2024). Impact of a Functional Dairy Powder and Its Primary Component on the Growth of Pathogenic and Probiotic Gut Bacteria and Human Coronavirus 229E. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(17), 9353. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11394815/pdf/ijms-25-09353.pdf. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidovich, P., Kearney, C. J., & Martin, S. J. (2014). Inflammatory outcomes of apoptosis, necrosis and necroptosis. Biological chemistry, 395(10), 1163-1171.

- De Francesco, E. M., Bonuccelli, G., Maggiolini, M., Sotgia, F., & Lisanti, M. P. (2017). Vitamin C and Doxycycline: A synthetic lethal combination therapy targeting metabolic flexibility in cancer stem cells (CSCs). Oncotarget, 8(40), 67269.

- Dissanayake, I. H., Alsherbiny, M. A., Chang, D., Li, C. G., & Bhuyan, D. J. (2023). Antiproliferative effects of Australian native plums against the MCF7 breast adenocarcinoma cells and UPLC-qTOF-IM-MS-driven identification of key metabolites. Food Bioscience, 54, 102864. [CrossRef]

- Djedjibegovic, J., Marjanovic, A., Panieri, E., & Saso, L. (2020). Ellagic acid-derived urolithins as modulators of oxidative stress. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2020(1), 5194508.

- Du, F.-Y., Zhou, Q.-F., Sun, W.-J., & Chen, G.-L. (2019). Targeting cancer stem cells in drug discovery: Current state and future perspectives. World journal of stem cells, 11(7), 398. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Wetidy, M. S., Ahmad, R., Rady, I., Helal, H., Rady, M. I., Vaali-Mohammed, M.-A., Al-Khayal, K., Traiki, T. B., & Abdulla, M.-H. (2021). Urolithin A induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by inhibiting Bcl-2, increasing p53-p21 proteins and reactive oxygen species production in colorectal cancer cells. Cell stress and chaperones, 26, 473-493.

- Eladwy, R. A., Alsherbiny, M. A., Chang, D., Fares, M., Li, C.-G., & Bhuyan, D. J. (2024). The postbiotic sodium butyrate synergizes the antiproliferative effects of dexamethasone against the AGS gastric adenocarcinoma cells. Frontiers in Nutrition, 11, 1372982. [CrossRef]

- Errafii, K. (2022). Identification of the Long Non-Coding RNAs and the Signaling Pathways Involved in the Protective Effect of the Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Exendin-4 on Hepatic Steatosis Hamad Bin Khalifa University (Qatar)].

- Fang, W., Wan, D., Yu, Y., & Zhang, L. (2024). CLEC11A expression as a prognostic biomarker in correlation to immune cells of gastric cancer. Biomolecules and Biomedicine, 24(1), 101.

- Fatma, F., & Kumar, A. (2021). The Cell Cycle, Cyclins, Checkpoints and Cancer.

- Ferlay, J., Ervik, M., Lam, F., Colombet, M., Mery, L., Piñeros, M., Znaor, A., Soerjomataram, I., & Bray, F. (2021). Global cancer observatory: cancer today. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. Cancer Tomorrow.

- Gallinari, P., Marco, S. D., Jones, P., Pallaoro, M., & Steinkühler, C. (2007). HDACs, histone deacetylation and gene transcription: from molecular biology to cancer therapeutics. Cell research, 17(3), 195-211. [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, G. R., Antony, P. J., Ceasar, S. A., Vasconcelos, A. B. S., Montalvão, M. M., Farias de Franca, M. N., Resende, A. d. S., Sharanya, C. S., Liu, Y., & Hariharan, G. (2024). Health functions and related molecular mechanisms of ellagitannin-derived urolithins. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 64(2), 280-310. [CrossRef]

- García-Hernández, L., García-Ortega, M. B., Ruiz-Alcalá, G., Carrillo, E., Marchal, J. A., & García, M. Á. (2021). The p38 MAPK components and modulators as biomarkers and molecular targets in cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(1), 370.

- Garnett, M. J., Mansfeld, J., Godwin, C., Matsusaka, T., Wu, J., Russell, P., Pines, J., & Venkitaraman, A. R. (2009). UBE2S elongates ubiquitin chains on APC/C substrates to promote mitotic exit. Nature cell biology, 11(11), 1363-1369. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, P., Dey, A., Nandi, S., Majumder, R., Das, S., & Mandal, M. (2025). CTGF (CCN2): a multifaceted mediator in breast cancer progression and therapeutic targeting. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews, 44(1), 32. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, V., Pereira, J. F., & Jordan, P. (2017). Signaling pathways driving aberrant splicing in cancer cells. Genes, 9(1), 9.

- Gout, S., Brambilla, E., Boudria, A., Drissi, R., Lantuejoul, S., Gazzeri, S., & Eymin, B. (2012). Abnormal expression of the pre-mRNA splicing regulators SRSF1, SRSF2, SRPK1 and SRPK2 in non small cell lung carcinoma.

- Guo, Q., Zhu, L., Wang, C., Wang, S., Nie, X., Liu, J., Liu, Q., Hao, Y., Li, X., & Lin, B. (2019). SERPIND1 affects the malignant biological behavior of epithelial ovarian cancer via the PI3K/AKT pathway: a mechanistic study. Frontiers in Oncology, 9, 954. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y., Dong, X., Jin, J., & He, Y. (2021). The expression patterns and prognostic value of the proteasome activator subunit gene family in gastric cancer based on integrated analysis. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology, 9, 663001.

- Hasheminezhad, S. H., Boozari, M., Iranshahi, M., Yazarlu, O., Sahebkar, A., Hasanpour, M., & Iranshahy, M. (2022). A mechanistic insight into the biological activities of urolithins as gut microbial metabolites of ellagitannins. Phytotherapy Research, 36(1), 112-146. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosoi, H., Tabata, S., Kosako, H., Hori, Y., Okamura, T., Yamashita, Y., Fujimoto, K., Kajioka, D., Suzuki, K., & Osato, M. (2024). IGLL5 controlled by super-enhancer affects cell survival and MYC expression in mature B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia Research Reports, 21, 100451.

- Hu, X., Ding, S., Lu, G., Lin, Z., Liao, L., Xiao, W., Ding, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, Z., & Gong, W. (2023). Apolipoprotein C-III itself stimulates the Syk/cPLA2-induced inflammasome activation of macrophage to boost anti-tumor activity of CD8+ T cell. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy, 72(12), 4123-4144. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-X., Zhang, X., Tang, M., Zhang, Q., Deng, L., Song, C.-H., Li, W., Shi, H.-P., & Cong, M.-H. (2024). Comprehensive evaluation of serum hepatic proteins in predicting prognosis among cancer patients with cachexia: an observational cohort study. BMC cancer, 24(1), 293.

- Huang, J., Wang, H., Xu, Y., Li, C., Lv, X., Han, X., Chen, X., Chen, Y., & Yu, Z. (2023). The role of CTNNA1 in malignancies: An updated review. Journal of Cancer, 14(2), 219.

- Huth, S., Huth, L., Marquardt, Y., Fietkau, K., Dahl, E., Esser, P. R., Martin, S. F., Heise, R., Merk, H. F., & Baron, J. M. (2020). Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain 5 (ITIH5) is a natural stabilizer of hyaluronan that modulates biological processes in the skin. Skin Pharmacology and Physiology, 33(4), 198-206. [CrossRef]

- Jaye, K., Alsherbiny, M. A., Chang, D., Li, C.-G., & Bhuyan, D. J. (2023). Mechanistic insights into the anti-proliferative action of gut microbial metabolites against breast adenocarcinoma cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(20), 15053.

- Kasahara, H., Hanada, A., Kuzuyama, T., Takagi, M., Kamiya, Y., & Yamaguchi, S. (2002). Contribution of the Mevalonate and Methylerythritol Phosphate Pathways to the Biosynthesis of Gibberellins inArabidopsis *. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 277(47), 45188-45194. [CrossRef]

- Khan, F., Elsori, D., Verma, M., Pandey, S., Obaidur Rab, S., Siddiqui, S., Alabdallah, N. M., Saeed, M., & Pandey, P. (2024). Unraveling the intricate relationship between lipid metabolism and oncogenic signaling pathways. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology, 12, 1399065. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S. F., Damerell, V., Omar, R., Du Toit, M., Khan, M., Maranyane, H. M., Mlaza, M., Bleloch, J., Bellis, C., & Sahm, B. D. (2020). The roles and regulation of TBX3 in development and disease. Gene, 726, 144223. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kho, Z. Y., & Lal, S. K. (2018). The human gut microbiome–a potential controller of wellness and disease. Frontiers in microbiology, 9, 1835. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-E., Mori, R., Komatsu, T., Chiba, T., Hayashi, H., Park, S., Sugawa, M. D., Dencher, N. A., & Shimokawa, I. (2015). Upregulation of cytochrome c oxidase subunit 6b1 (Cox6b1) and formation of mitochondrial supercomplexes: implication of Cox6b1 in the effect of calorie restriction. Age, 37, 1-17.

- Kuszczak, B., Łacina, P., Dratwa-Kuźmin, M., Bogunia-Kubik, K., Wróbel, T., & Rybka, J. (2025). Evaluation of polymorphism in BCL-2, PD-1, and PD-L1 genes in myelodysplastic neoplasms. Acta Haematologica Polonica.

- Lagrange, J., Lecompte, T., Knopp, T., Lacolley, P., & Regnault, V. (2022). Alpha-2-macroglobulin in hemostasis and thrombosis: an underestimated old double-edged sword. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 20(4), 806-815.

- Lefort, N., Yi, Z., Bowen, B., Glancy, B., De Filippis, E. A., Mapes, R., Hwang, H., Flynn, C. R., Willis, W. T., & Civitarese, A. (2009). Proteome profile of functional mitochondria from human skeletal muscle using one-dimensional gel electrophoresis and HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Journal of proteomics, 72(6), 1046-1060. [CrossRef]

- Lewies, A., Du Plessis, L. H., & Wentzel, J. F. (2018). The cytotoxic, antimicrobial and anticancer properties of the antimicrobial peptide nisin Z alone and in combination with conventional treatments. Cytotoxicity, 25, 21.

- Li, C.-H., Hsu, T.-I., Chang, Y.-C., Chan, M.-H., Lu, P.-J., & Hsiao, M. (2021). Stationed or relocating: The seesawing emt/met determinants from embryonic development to cancer metastasis. Biomedicines, 9(9), 1265. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J., Dallmayer, M., Kirchner, T., Musa, J., & Grünewald, T. G. (2018). PRC1: linking cytokinesis, chromosomal instability, and cancer evolution. Trends in cancer, 4(1), 59-73.

- Li, L., Zhang, G., Yang, Z., & Kang, X. (2024). Stress-Activated Protein Kinases in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration: Unraveling the Impact of JNK and p38 MAPK. Biomolecules, 14(4), 393. [CrossRef]

- Li, X. (2024). Role of FOXM1, GPX1, and CCNB1 in cisplatin resistance in malignant thymomas and thymic carcinomas.

- Liao, L., Zhang, Y.-L., Deng, L., Chen, C., Ma, X.-Y., Andriani, L., Yang, S.-Y., Hu, S.-Y., Zhang, F.-L., & Shao, Z.-M. (2023). Protein phosphatase 1 subunit PPP1R14B stabilizes STMN1 to promote progression and paclitaxel resistance in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer research, 83(3), 471-484.

- Lin, M. Y., De Zoete, M. R., Van Putten, J. P., & Strijbis, K. (2015). Redirection of epithelial immune responses by short-chain fatty acids through inhibition of histone deacetylases. Frontiers in immunology, 6, 554.

- Liu, Y., & Wang, H. (2024). Biomarkers and targeted therapy for cancer stem cells. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 45(1), 56-66. [CrossRef]

- Maffeo, B., & Cilloni, D. (2024). The ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 O (UBE2O) and its therapeutic potential in human leukemias and solid tumors. Cancers, 16(17), 3064.

- Mager, L. F., Burkhard, R., Pett, N., Cooke, N. C., Brown, K., Ramay, H., Paik, S., Stagg, J., Groves, R. A., & Gallo, M. (2020). Microbiome-derived inosine modulates response to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Science, 369(6510), 1481-1489. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majka, J., & Burgers, P. M. (2004). The PCNA-RFC families of DNA clamps and clamp loaders. Progress in nucleic acid research and molecular biology, 78, 227-260.

- Mathew, M., Nguyen, N. T., Bhutia, Y. D., Sivaprakasam, S., & Ganapathy, V. (2024). Metabolic signature of Warburg effect in cancer: An effective and obligatory interplay between nutrient transporters and catabolic/anabolic pathways to promote tumor growth. Cancers, 16(3), 504. [CrossRef]

- Matuszyk, J. (2022). MALAT1-miRNAs network regulate thymidylate synthase and affect 5FU-based chemotherapy. Molecular Medicine, 28(1), 89.

- Mei, B., Chen, Y., Chen, J., Pan, C. Q., & Murphy, J. E. (2006). Expression of human coagulation factor VIII in a human hybrid cell line, HKB11. Molecular Biotechnology, 34, 165-178.

- Minotti, G., Menna, P., Salvatorelli, E., Cairo, G., & Gianni, L. (2004). Anthracyclines: molecular advances and pharmacologic developments in antitumor activity and cardiotoxicity. Pharmacological reviews, 56(2), 185-229.

- Mohammad, S. The influence of stromal fibroblast on antigen-presenting cell function and alteration of their biology University of Nottingham].

- Mura, M., Hopkins, T. G., Michael, T., Abd-Latip, N., Weir, J., Aboagye, E., Mauri, F., Jameson, C., Sturge, J., & Gabra, H. (2015). LARP1 post-transcriptionally regulates mTOR and contributes to cancer progression. Oncogene, 34(39), 5025-5036. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, Y., Su, H., Zhou, B., & Liu, S. (2023). The function of natural compounds in important anticancer mechanisms. Frontiers in Oncology, 12, 1049888.

- Niamah, A. K., Al-Sahlany, S. T. G., Verma, D. K., Shukla, R. M., Patel, A. R., Tripathy, S., Singh, S., Baranwal, D., Singh, A. K., & Utama, G. L. (2024). Emerging lactic acid bacteria bacteriocins as anti-cancer and anti-tumor agents for human health. Heliyon, 10(17).

- O’keefe, S. J. (2016). Diet, microorganisms and their metabolites, and colon cancer. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology, 13(12), 691-706.

- Odiase, P., Ma, J., Ranganathan, S., Ogunkua, O., Turner, W. B., Marshall, D., & Ochieng, J. (2024). The Role of Fetuin-A in Tumor Cell Growth, Prognosis, and Dissemination. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(23), 12918. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oquendo, C. J., Parker, H., Oscier, D., Ennis, S., Gibson, J., & Strefford, J. C. (2021). The (epi)genomic landscape of splenic marginal zone lymphoma, biological implications, clinical utility, and future questions. Journal of Translational Genetics and Genomics, 5(2), 89-111. https://www.oaepublish.com/articles/jtgg.2021.04.

- Osman, S., & Cramer, P. (2020). Structural biology of RNA polymerase II transcription: 20 years on. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, 36(1), 1-34.

- Parra-Medina, R., Cardona, A. G., Quintero-Ronderos, P., & Rodríguez, É. G. CYTOKINES, CHEMOKINES AND GROWTH FACTORS.

- Pelicano, H., Carney, D., & Huang, P. (2004). ROS stress in cancer cells and therapeutic implications. Drug resistance updates, 7(2), 97-110. [CrossRef]

- Peluzio, M. d. C. G., Martinez, J. A., & Milagro, F. I. (2021). Postbiotics: Metabolites and mechanisms involved in microbiota-host interactions. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 108, 11-26.

- Peng, F., Li, S., Wang, L., Han, M., Fan, H., Tang, H., Peng, C., Du, J., & Zhou, Z. Combination of Hdac Inhibitor Sodium Butyrate and Immunotherapy in Glioma: Regulation of Immunologically Hot and Cold Tumors Via Gut Microbiota and Metabolites. Available at SSRN 4942877.

- Peplow, P. V. (2024). Reprogramming T cells as an emerging treatment to slow human age-related decline in health [Opinion]. Frontiers in Medical Technology, Volume 6—2024. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Riverol, Y., Bandla, C., Kundu, D. J., Kamatchinathan, S., Bai, J., Hewapathirana, S., John, N. S., Prakash, A., Walzer, M., & Wang, S. (2025). The PRIDE database at 20 years: 2025 update. Nucleic acids research, 53(D1), D543-D553. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pino, L. K., Just, S. C., MacCoss, M. J., & Searle, B. C. (2020). Acquiring and analyzing data independent acquisition proteomics experiments without spectrum libraries. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, 19(7), 1088-1103.

- Preet, S., Pandey, S., Saini, N., Koul, A., & Rishi, P. (2015). Nisin augments doxorubicin permeabilization and ameliorates signaling cascade during skin carcinogenesis. Transl Med, 6(161), 2161-1025.1000161.

- Qiu, Y.-Y., Zhang, J., Zeng, F.-Y., & Zhu, Y. Z. (2023). Roles of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Pharmacological Research, 192, 106786.

- Rafique, N., Jan, S. Y., Dar, A. H., Dash, K. K., Sarkar, A., Shams, R., Pandey, V. K., Khan, S. A., Amin, Q. A., & Hussain, S. Z. (2023). Promising bioactivities of postbiotics: A comprehensive review. Journal of agriculture and Food Research, 100708. [CrossRef]

- Reeder, B. J. (2017). Redox and peroxidase activities of the hemoglobin superfamily: relevance to health and disease. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 26(14), 763-776.

- Reuter, S., Gupta, S. C., Chaturvedi, M. M., & Aggarwal, B. B. (2010). Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free radical biology and medicine, 49(11), 1603-1616.

- Riester, D., Hildmann, C., & Schwienhorst, A. (2007). Histone deacetylase inhibitors—turning epigenic mechanisms of gene regulation into tools of therapeutic intervention in malignant and other diseases. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 75, 499-514. [CrossRef]

- Rius-Pérez, S., Torres-Cuevas, I., Millán, I., Ortega, Á. L., & Pérez, S. (2020). PGC-1α, inflammation, and oxidative stress: an integrative view in metabolism. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2020(1), 1452696. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A., Mazzara, S., Salemi, D., Zanetti, S., Sapienza, M. R., Orecchioni, S., Talarico, G., Falvo, P., Davini, A., & Ceccarelli, C. (2025). Downregulation of rRNA synthesis by BCL-2 induces chemoresistance in Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma. iScience.

- Ryu, D., Mouchiroud, L., Andreux, P. A., Katsyuba, E., Moullan, N., Nicolet-dit-Félix, A. A., Williams, E. G., Jha, P., Lo Sasso, G., & Huzard, D. (2016). Urolithin A induces mitophagy and prolongs lifespan in C. elegans and increases muscle function in rodents. Nature medicine, 22(8), 879-888. [CrossRef]

- Sadri, H., Aghaei, M., & Akbari, V. (2022). Nisin induces apoptosis in cervical cancer cells via reactive oxygen species generation and mitochondrial membrane potential changes. Biochemistry and Cell Biology, 100(2), 136-141.

- Samban, S. S., Hari, A., Nair, B., Kumar, A. R., Meyer, B. S., Valsan, A., Vijayakurup, V., & Nath, L. R. (2024). An insight into the role of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) in the development and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Molecular Biotechnology, 66(10), 2697-2709.

- Santos, O. F., Moura, L. A., Rosen, E. M., & Nigam, S. K. (1993). Modulation of HGF-induced tubulogenesis and branching by multiple phosphorylation mechanisms. Developmental biology, 159(2), 535-548.

- Sarkar, S., Sahoo, P. K., Mahata, S., Pal, R., Ghosh, D., Mistry, T., Ghosh, S., Bera, T., & Nasare, V. D. (2021). Mitotic checkpoint defects: en route to cancer and drug resistance. Chromosome Research, 29(2), 131-144. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, S. L. G., Gomes, X. V., & Burgers, P. M. (2001). ATP utilization by yeast replication factor C: III. The ATP-binding domains of Rfc2, Rfc3, and Rfc4 are essential for DNA recognition and clamp loading. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 276(37), 34784-34791.

- Schumacker, P. T. (2006). Reactive oxygen species in cancer cells: live by the sword, die by the sword. Cancer cell, 10(3), 175-176.

- Sheibani, M., Azizi, Y., Shayan, M., Nezamoleslami, S., Eslami, F., Farjoo, M. H., & Dehpour, A. R. (2022). Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: an overview on pre-clinical therapeutic approaches. Cardiovascular Toxicology, 22(4), 292-310. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y. Q., Guerra-Librero, A., Fernandez-Gil, B. I., Florido, J., García-López, S., Martinez-Ruiz, L., Mendivil-Perez, M., Soto-Mercado, V., Acuña-Castroviejo, D., & Ortega-Arellano, H. (2018). Combination of melatonin and rapamycin for head and neck cancer therapy: Suppression of AKT/mTOR pathway activation, and activation of mitophagy and apoptosis via mitochondrial function regulation. Journal of pineal research, 64(3), e12461.

- Shetty, S. S., Shetty, S., & Kumari, N. S. (2024). Therapeutic efficacy of gut microbiota-derived polyphenol metabolite Urolithin A. Beni-Suef University Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 13(1), 31. [CrossRef]

- Shimano, H., & Sato, R. (2017). SREBP-regulated lipid metabolism: convergent physiology—divergent pathophysiology. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 13(12), 710-730. [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, S., & Gorbsky, G. J. (2015). Spatiotemporal regulation of the anaphase-promoting complex in mitosis. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology, 16(2), 82-94.

- Stanisławska, I., Piwowarski, J., Granica, S., & Kiss, A. (2017). Urolithins, gut microbiota metabolites of ellagitannins, in prostate cancer chemoprevention. Planta Medica International Open, 4(S 01), Mo-PO-16.

- Steliou, K., Boosalis, M. S., Perrine, S. P., Sangerman, J., & Faller, D. V. (2012). Butyrate histone deacetylase inhibitors. BioResearch open access, 1(4), 192-198. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strzalka, W., & Ziemienowicz, A. (2011). Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA): a key factor in DNA replication and cell cycle regulation. Annals of botany, 107(7), 1127-1140.

- Sturm, D., Orr, Brent A., Toprak, Umut H., Hovestadt, V., Jones, David T. W., Capper, D., Sill, M., Buchhalter, I., Northcott, Paul A., Leis, I., Ryzhova, M., Koelsche, C., Pfaff, E., Allen, Sariah J., Balasubramanian, G., Worst, Barbara C., Pajtler, Kristian W., Brabetz, S., Johann, Pascal D.,... Kool, M. (2016). New Brain Tumor Entities Emerge from Molecular Classification of CNS-PNETs. cell, 164(5), 1060-1072. [CrossRef]

- Su, C., Mo, J., Dong, S., Liao, Z., Zhang, B., & Zhu, P. (2024). Integrinβ-1 in disorders and cancers: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Cell Communication and Signaling, 22(1), 71.

- Subbian, S., Bandyopadhyay, N., Tsenova, L., O’Brien, P., Khetani, V., Kushner, N. L., Peixoto, B., Soteropoulos, P., Bader, J. S., & Karakousis, P. C. (2013). Early innate immunity determines outcome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis pulmonary infection in rabbits. Cell Communication and Signaling, 11, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.-D., Zhu, X.-J., Li, J.-J., Mei, Y.-Z., Li, W.-S., & Li, J.-H. (2024). Nicotinamide N-methyltransferase (NNMT): A key enzyme in cancer metabolism and therapeutic target. International Immunopharmacology, 142, 113208.

- Swerdlow, S. H., Campo, E., Pileri, S. A., Harris, N. L., Stein, H., Siebert, R., Advani, R., Ghielmini, M., Salles, G. A., & Zelenetz, A. D. (2016). The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology, 127(20), 2375-2390. [CrossRef]

- Szilveszter, R.-M., Muntean, M., & Florea, A. (2024). Molecular Mechanisms in Tumorigenesis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and in Target Treatments—An Overview. Biomolecules, 14(6), 656.

- Tan, J. K., Macia, L., & Mackay, C. R. (2023). Dietary fiber and SCFAs in the regulation of mucosal immunity. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology, 151(2), 361-370. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaiss, C. A., Zeevi, D., Levy, M., Segal, E., & Elinav, E. (2015). A day in the life of the meta-organism: diurnal rhythms of the intestinal microbiome and its host. Gut microbes, 6(2), 137-142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trachootham, D., Alexandre, J., & Huang, P. (2009). Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach? Nature reviews Drug discovery, 8(7), 579-591.

- Valko, M., Rhodes, C., Moncol, J., Izakovic, M., & Mazur, M. (2006). Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chemico-biological interactions, 160(1), 1-40.

- Vikramdeo, K. S., Sudan, S. K., Singh, A. P., Singh, S., & Dasgupta, S. (2022). Mitochondrial respiratory complexes: Significance in human mitochondrial disorders and cancers. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 237(11), 4049-4078.

- Wang, C., Wu, Y., Gong, B., Mou, J., Cheng, X., Zhang, L., & Wei, J. (2025). Agarwood Chromone Alleviates Gastric Ulcers by Inhibiting the NF-κB and Caspase Pathways Based on Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking. Pharmaceuticals, 18(4), 514. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., Song, M., Zeng, Z.-l., Zhu, C.-f., Lu, W.-h., Yang, J., Ma, M.-z., Huang, A.-m., Hu, Y., & Huang, P. (2015). Identification of NDUFAF1 in mediating K-Ras induced mitochondrial dysfunction by a proteomic screening approach. Oncotarget, 6(6), 3947.

- Wang, Z. (2021). Regulation of cell cycle progression by growth factor-induced cell signaling. Cells, 10(12), 3327.

- Woodard, K. J. (2021). Genomic Characterization of Sickle Cell Mouse Models for Therapeutic Genome Editing Applications. The University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

- Wu, X., Yu, X., Chen, C., Chen, C., Wang, Y., Su, D., & Zhu, L. (2024). Fibrinogen and tumors. Frontiers in Oncology, 14, 1393599.

- Xu, Y.-c., Su, J., Zhou, J.-j., Yuan, Q., & Han, J.-s. (2023). Roles of MT-ND1 in Cancer. Current Medical Science, 43(5), 869-878. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Bai, X., Liu, G., & Li, X. (2022). A transcriptional regulatory network of HNF4α and HNF1α involved in human diseases and drug metabolism. Drug Metabolism Reviews, 54(4), 361-385.

- Yue, J., & López, J. M. (2020). Understanding MAPK signaling pathways in apoptosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(7), 2346.

- Zhang, C., Zhao, L., Leng, L., Zhou, Q., Zhang, S., Gong, F., Xie, P., & Lin, G. (2020). CDCA8 regulates meiotic spindle assembly and chromosome segregation during human oocyte meiosis. Gene, 741, 144495. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Jiang, L., Su, P., Yu, T., Ma, Z., Liu, Y., & Yu, J. (2023). Urolithin A suppresses tumor progression and induces autophagy in gastric cancer via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Drug Development Research, 84(2), 172-184.

- Zhou, B., Zhao, Y. C., Liu, H., Luo, S., Amos, C. I., Lee, J. E., Li, X., Nan, H., & Wei, Q. (2020). Novel genetic variants of ALG6 and GALNTL4 of the glycosylation pathway predict cutaneous melanoma-specific survival. Cancers, 12(2), 288.

- Zhu, Y., Dwidar, M., Nemet, I., Buffa, J. A., Sangwan, N., Li, X. S., Anderson, J. T., Romano, K. A., Fu, X., & Funabashi, M. (2023). Two distinct gut microbial pathways contribute to meta-organismal production of phenylacetylglutamine with links to cardiovascular disease. Cell host & microbe, 31(1), 18-32. e19.

- Zitvogel, L., Daillère, R., Roberti, M. P., Routy, B., & Kroemer, G. (2017). Anticancer effects of the microbiome and its products. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 15(8), 465-478. [CrossRef]

| Cell growth inhibition (%) of HKB-11 lymphoma cell line | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (µM) |

N | Sodium butyrate | Sodium propionate | Magnesium acetate | Inosine | Concentration (µM) |

UA | UB |

| 16000 | NA | 63.83 ± 8.99 a | 51.45 ± 12.41 b | 18.23 ± 5.66 c | 35.2 ± 10.76 d | 500 | 61.51 ± 13.44 a | 81.81 ± 9.51 b |

| 8000 | 100.26 ± 0.09 a | 57.83 ± 9.95 b | 38.07 ± 10.39 c | 9.97 ± 3.12 d | 30.91 ± 6.27 e | 250 | 39.31 ± 12.18 a | 74.24 ± 4.91 b |

| 4000 | 100.21 ± 0.18 a | 53.18 ± 10.22 b | 16.31 ± 7.30 c | 9.86 ± 4.18 d | 27.02 ± 8.27 e | 125 | 18.22 ± 10.15 a | 55.51 ± 7.58 b |

| 2000 | 65.22 ± 1.35 a | 45.36 ± 9.08 b | 11.82 ± 2.51 c | 8.57 ± 4.41 d | 19.32 ± 7.15 e | 62.5 | 12.03 ± 5.16 a | 39.63 ± 7.48 b |

| 1000 | 34.84 ± 3.52 a | 23.33 ± 6.66 b | 10.26 ± 3.23 c | 7.85 ± 4.89 d | 14.41 ± 5.2 e | 31.25 | 10.77 ± 6.16 a | 36.16 ± 11.92 b |

| 500 | 15.18 ± 6.98 a | 18.58 ± 3.59 b | 10.99 ± 2.83 c | 7.61 ± 5.66 d | 13.54 ± 4.57 e | 15.625 | 8.16 ± 5.42 a | 30.96 ± 15.63 b |

| 250 | 2.64 ± 3.47 a | 15.31 ± 3.23 b | 9.47 ± 2.61 c | 6.82 ± 6.07 d | 12.42 ± 6.04 e | 7.8125 | 6.84 ± 4.75 a | 23.05 ± 2.71 b |

| 125 | ND | 13.38 ± 3.51 a | 7.75 ± 4.79 b | 6.66 ± 4.01 c | 9.45 ± 4.76 d | 3.90625 | 5.72 ± 5.12 a | 17.99 ± 3.26 b |

| 62.5 | ND | 11.64 ± 3.91 a | 5.7 ± 4.21 b | 5.47 ± 3.16 c | 7.69 ± 5.33 d | 1.953125 | 5.64 ± 5.61 a | 12.22 ± 2.73 b |

| IC50 | 1467 µM | 2022 µM | 14597.14 µM | NA | NA | 384.41 µM | 87.56 µM | |

| Combinations N: UB |

IC50 | IC75 | IC90 | IC95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:9 (800:450 μM) | 1.02 | 0.74 | 0.54 | 0.44 |

| 2:8 (1600:400 μM) | 1.03 | 0.88 | 0.76 | 0.69 |

| 3:7 (2400:350 μM) | 0.95 | 0.61 | 0.40 | 0.31 |

| 4:6 (3200:300μM) | 0.77 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.09 |

| 5:5 (4000:250 μM) | 0.94 | 0.53 | 0.31 | 0.22 |

| 6:4 (4800:200 μM) | 1.09 | 0.66 | 0.42 | 0.32 |

| 7:3 (5600:150 μM) | 0.91 | 0.46 | 0.25 | 0.17 |

| 8:2 (6400:100 μM) | 0.61 | 0.41 | 0.30 | 0.26 |

| 9:1 (7200:50 μM) | 1.32 | 0.92 | 0.70 | 0.61 |

| Concentration (μM) N: UB 4:6 (3200 : 300) | Cell growth inhibition (%) | Cell viability (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HKB-11 | Hs 313.T | HS-5 | |

| 3500 | 98.49 ± 2.43 a | 100.55 ± 0.04 a | 10.08 ± 4.01 |

| 1750 | 65.77 ± 9.03 a | 90.26 ± 1.17 b | 17.92 ± 2.52 |

| 875 | 46.80 ± 1.32 a | 86.33 ± 1.59 b | 23.46 ± 3.96 |

| 437.5 | 30.04 ± 7.51 a | 76.06 ± 4.43 b | 66.37 ± 11.53 |

| 218.75 | 25.74 ± 17.07 a | 29.84 ± 7.04 a | 89.08 ± 9.20 |

| 109.375 | 21.86 ± 16.07 a | 9.99 ± 8.81 a | 92.32 ± 7.72 |

| IC50 | 1304 μM | 335.4 μM | 551.6 μM |

| Treatment | Log2FC | Gene ID | Protein Descriptions | Molecular pathway | Mechanism of action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N 3200 μM | -1.27 | LARP1 | La-related protein 1 | mTOR signalling and RNA binding | Regulates mRNA stability and translation of survival genes. | (Mura et al., 2015; Oquendo et al., 2021) |

| -1.54 | TYMS | Thymidylate synthase | Nucleotide synthesis and DNA replication | Catalyzes thymidylate synthesis; target of 5-FU chemotherapy. | (Matuszyk, 2022; Peplow, 2024) | |

| -0.80 | MAPK14 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 | MAPK/p38 signaling pathway | Mediates cellular response to stress, inflammation, and proliferation. | (García-Hernández et al., 2021) | |

| -0.72 | PRC1 | Protein regulator of cytokinesis 1 | Cell cycle progression and mitosis | Regulates cytokinesis and mitotic spindle formation. | (Li et al., 2018) | |

| -0.70 | SRPK2 | SRSF protein kinase 2 | RNA splicing and nuclear mRNA processing | Works with SRPK1 in regulating alternative splicing. | (Gonçalves et al., 2017; Gout et al., 2012) | |

| -1.26 | CDK4 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 | Cell cycle (G1/S transition) | Phosphorylates RB1, promoting E2F release and progression through G1 phase | (Sturm et al., 2016) | |

| -0.62 | POLR2E | DNA-directed RNA polymerases I, II, and III subunit RPABC1 | Transcription (RNA Polymerase II complex) | Essential subunit for RNA Polymerase II assembly and mRNA transcription | (Kasahara et al., 2002) | |

| -0.63 | POLR2G | DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB7 | Transcription (RNA Polymerase II complex) | Structural component maintaining polymerase II processivity | (Cramer, 2004; Osman & Cramer, 2020) | |

| -0.59 | POLR2H | DNA-directed RNA polymerases I, II, and III subunit RPABC3 | Transcription (RNA Polymerase II complex) | Stabilizes RNA Pol II structure; shared across all RNA polymerases | (Brandão et al., 2022; Osman & Cramer, 2020) | |

| -0.85 | RFC1 | Replication factor C subunit 1 | DNA replication (clamp loader complex) | Loads PCNA onto DNA, facilitating DNA polymerase binding during replication | (Majka & Burgers, 2004) | |

| -0.59 | RFC2 | Replication factor C subunit 2 | DNA replication and repair | Binds RFC1 to form RFC complex; essential for DNA synthesis fidelity | (Schmidt et al., 2001) | |

| -0.60 | NUP62 | Nuclear pore glycoprotein p62 | Nucleocytoplasmic transport (nuclear pore complex) | Central channel component; regulates import/export of macromolecules | (Bano et al., 2010) | |

| -0.93 | PPP1R14B | Protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 14B | Actin cytoskeleton regulation | Inhibits protein phosphatase 1, affecting the cytoskeleton and cell motility | (Bao et al., 2024; Liao et al., 2023) | |

| -0.97 | CTNNA1 | Catenin alpha-1 | Cell adhesion (cadherin complex) | Links cadherins to actin cytoskeleton; maintains epithelial integrity | (Huang et al., 2023) | |

| -0.67 | HDAC1 | Histone deacetylase 1 | Epigenetic regulation (histone deacetylation) | Removes acetyl groups from histones, repressing transcription | (Gallinari et al., 2007) | |

| UB 300 μM |

2.04 | APOC3 | Apolipoprotein C-III | Triglyceride metabolism | Alters lipid signalling; enhances inflammatory microenvironment | (Hu et al., 2023) |

| 4.39 | C4BPA | C4b-binding protein alpha chain | Complement pathway | Inhibits complement-mediated lysis; immune evasion | (Blom et al., 2004) | |

| 3.06 | CLEC11A | C-type lectin domain family 11 member A | Cytokine signaling | Promotes endothelial and hematopoietic support in TME | (Fang et al., 2024) | |

| 2.07 | COX6C | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 6C | Respiratory chain complex IV | Boosts mitochondrial respiration | (Kim et al., 2015) | |

| 2.08 | COX7C | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 7C, mitochondrial | Cytochrome c oxidase | Increases mitochondrial adaptability in tumours | (De Francesco et al., 2017) | |

| 2.14 | FGB | Fibrinogen beta chain | Coagulation cascade | Promotes vascularisation and fibrin scaffolding in tumours | (Wu et al., 2024) | |

| 2.26 | GSN | Gelsolin | Actin regulation | Modulates the actin cytoskeleton for migration and invasion | (Alsofyani & Nedjadi, 2023) | |

| 5.94 | HBD | Hemoglobin subunit delta;Hemoglobin subunit beta | Hemoglobin complex | Facilitates oxygen delivery; modulates redox status | (Reeder, 2017) | |

| 5.63 | HBE1 | Hemoglobin subunit epsilon;Hemoglobin subunit gamma-1;Hemoglobin subunit gamma-2 | Fetal hemoglobin pathway | Reactivation may aid hypoxic survival in tumours | (Woodard, 2021) | |

| 2.76 | ITIH2 | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H2 | Matrix stability | Regulates hyaluronic acid and ECM stiffness | (Huth et al., 2020) | |

| 2.34 | MT-CO2 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 2 | Mitochondrial respiration | Supports tumour ATP production and ROS balance | (Vikramdeo et al., 2022) | |

| 2.24 | MT-ND4 | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 4 | Complex I, OXPHOS | Enhances mitochondrial respiration and survival under stress | (Xu et al., 2023) | |

| 2.18 | NDUFA11 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 11 | OXPHOS complex I | Maintains mitochondrial metabolism in cancer cells | (Wang et al., 2015) | |

| 2.01 | SAMM50 | Sorting and assembly machinery component 50 homolog | Protein import | Preserves outer membrane; supports anti-apoptotic signals | (Lefort et al., 2009) | |

| -1.45 | MAD2L1 | Mitotic spindle assembly checkpoint protein MAD2A | Mitotic checkpoint (Spindle Assembly Checkpoint, SAC) | Ensures proper chromosome segregation, disrupts mitosis, causing mitotic arrest or apoptotic cell death | (Bates et al., 2020) | |

| -0.59 | PSME3 | Proteasome activator complex subunit 3 | Proteasome activation, p53 degradation | Degrades tumor suppressor proteins. Its suppression stabilizes p53, enhancing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest | (Guo et al., 2021) | |

| -1.21 | UBE2S | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 S | Ubiquitination, mitotic exit | Ubiquitinates mitotic inhibitors (APC/C complex co-activator), Downregulation leads to mitotic arrest, promoting senescence |

(Garnett et al., 2009) | |

| -0.63 | PCNA | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen | DNA replication and repair | Sliding clamp for DNA polymerases, Loss of PCNA function causes replication stress and apoptosis |

(Strzalka & Ziemienowicz, 2011) | |

| -1.69 | UBE2E1 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 E1;Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 E3;Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 E2 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme | Supports proteostasis, DNA repair, Suppression disrupts protein quality control, leading to cell death | (Maffeo & Cilloni, 2024) | |

| N: UB 4:6 (3200:300 μM) |

2.30 | A2M | Alpha-2-macroglobulin | Protease inhibition, complement cascade | Regulates proteolysis, potentially restricts tumor invasion. | (Lagrange et al., 2022) |

| 0.67 | CDC27 | Cell division cycle protein 27 homolog | Mitotic Checkpoint (Anaphase-Promoting Complex, APC/C) | Regulates ubiquitination of mitotic regulators | (Sivakumar & Gorbsky, 2015) | |

| 2.45 | AFP | Alpha-fetoprotein | Oncofetal protein, MAPK signaling | Supports tumor proliferation, angiogenesis; marker in hepatic and hematological cancers. | (Samban et al., 2024) | |

| 2.56 | AHSG | Alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein | TGF-β inhibition | Inhibits calcification and regulates inflammation in tumors | (Odiase et al., 2024) | |

| 2.32 | ALB | Albumin | Plasma transport | High levels may reflect cancer cachexia or liver activity during tumor burden. | (Huang et al., 2024) | |

| 6.55 | ALG6 | Dolichyl pyrophosphate Man9GlcNAc2 alpha-1,3-glucosyltransferase | N-glycosylation | Promotes ER glycoprotein processing; linked to tumor cell survival | (Zhou et al., 2020) | |

| 2.64 | IGLL5 | Immunoglobulin lambda-like polypeptide 5 | B-cell development | Overexpressed in some B-cell lymphomas; immune receptor surrogate | (Hosoi et al., 2024) | |

| 2.36 | LCAT | Phosphatidylcholine-sterol acyltransferase | HDL metabolism | Alters cholesterol availability in tumors | (D’Arca et al., 2023) | |

| 2.46 | NNMT | Nicotinamide N-methyltransferase | Nicotinamide methylation | Reprograms NAD+ metabolism, supports proliferation | (Sun et al., 2024) | |

| 2.38 | SERPINA7 | Thyroxine-binding globulin | Thyroid hormone transport | Affects hormone signaling relevant to cancer cell growth | (Guo et al., 2019) | |

| 2.27 | SERPINF1 | Pigment epithelium-derived factor | Anti-angiogenic | Inhibits neovascularisation; tumor-suppressive in some contexts | (Mathew et al., 2024) | |

| 3.41 | TF | Serotransferrin | Iron transport | Modulates iron availability and oxidative stress in tumor cells | (Chen et al., 2019) | |

| 1.78 | F10 | Coagulation factor X | Coagulation cascade | Activation of prothrombin to thrombin; can affect tumor vascularization | (Alexander & Gilmour, 2022) | |

| 0.71 | FGB | Fibrinogen beta chain | Extracellular matrix (ECM) interaction | Participates in clot formation and tissue remodeling | (Wu et al., 2024) | |

| 0.65 | ITGB1 | Integrin beta-1 | Cell adhesion, survival signaling | Binds ECM; activates FAK, PI3K pathways | (Su et al., 2024) | |

| 0.77 | RANGAP1 | Ran GTPase-activating protein 1 | Nuclear transport and cell cycle regulation | Controls Ran GTPase cycle; vital for nuclear envelope reformation during mitosis, | (Ciciarello et al., 2007) | |

| -0.75 | BUB3 | Mitotic checkpoint protein BUB3 | Spindle Assembly Checkpoint (SAC) | Ensures correct chromosomal segregation, Loss promotes chromosomal instability but can also trigger catastrophic cell death in tumors | (Sarkar et al., 2021) | |

| -1.18 | CCNB1 | G2/mitotic-specific cyclin-B1 | Cell cycle control (G2/M checkpoint) | Complexes with CDK1 to trigger mitosis, Downregulation leads to G2/M arrest and apoptosis | (Li, 2024) | |

| -0.60 | CDCA8 | Borealin | Chromosome passenger complex (CPC) | Regulates mitosis and cytokinesis, Loss disrupts chromosomal stability, causing mitotic catastrophe | (Zhang et al., 2020) | |

| -0.66 | CDK1 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 | Master G2/M checkpoint kinase | Phosphorylates downstream mitotic proteins , Inhibition causes G2/M phase arrest, senescence, or apoptosis | (Fatma & Kumar, 2021) | |

| -0.59 | MAP2K4 | Dual specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 | JNK/p38 MAPK stress pathway | Activates pro-apoptotic MAPK cascades , block survival signals, sensitizing cells to apoptosis | (Li et al., 2024; Yue & López, 2020) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).