1. Introduction

The capacity of tumor cells to evade the immune response, a phenomenon referred to as immune escape, and their acquired resistance to anti-cancer therapies, are major challenges to the effective management of cancer [1]. A fundamental mechanism underlying this process is the interaction between Programmed Death Ligand 1 (PD-L1) expressed in cancer cells and the Programmed Death 1 (PD-1) receptor on cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), which inhibits T cell activity [2,3,4]. The PD-1/PD-L1 axis is one of several immune checkpoint regulators that play critical roles in maintaining self-tolerance and modulating the duration and intensity of immune responses, primarily by inhibiting adaptive T cell responses. Tumor cells exploit this mechanism to suppress anti-tumor responses, leading to CTL exhaustion and heightened resistance to pro-apoptotic signals. Currently, immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) using anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies is a promising therapeutic strategy for cancer patients [5]. However, approximately 30% of patients relapse, highlighting the need for alternative strategies to regulate the PD-1/PD-L1 axis [6].

PD-L1 is markedly overexpressed in melanoma, lung, ovarian, pancreatic, colorectal, and breast cancers. In breast cancer, elevated PD-L1 levels are associated with unfavorable clinical outcomes and correlated with negative prognostic indicators, such as an increased proliferation index, larger tumor size, the absence of estrogen or progesterone receptors, HER2 positivity, and higher tumor grade [7,8,9,10]. These associations suggest that the inhibition of PD-L1 expression is a promising approach for immune checkpoint-based cancer therapies. Recent studies have demonstrated that compounds such as berberine, luteolin, apigenin, cosmosiin, and luteolin have the potential to reactivate anti-cancer immune responses and improve therapeutic efficacy by modulating either constitutive or inducible PD-L1 expression in cancer cells [11,12,13,14].

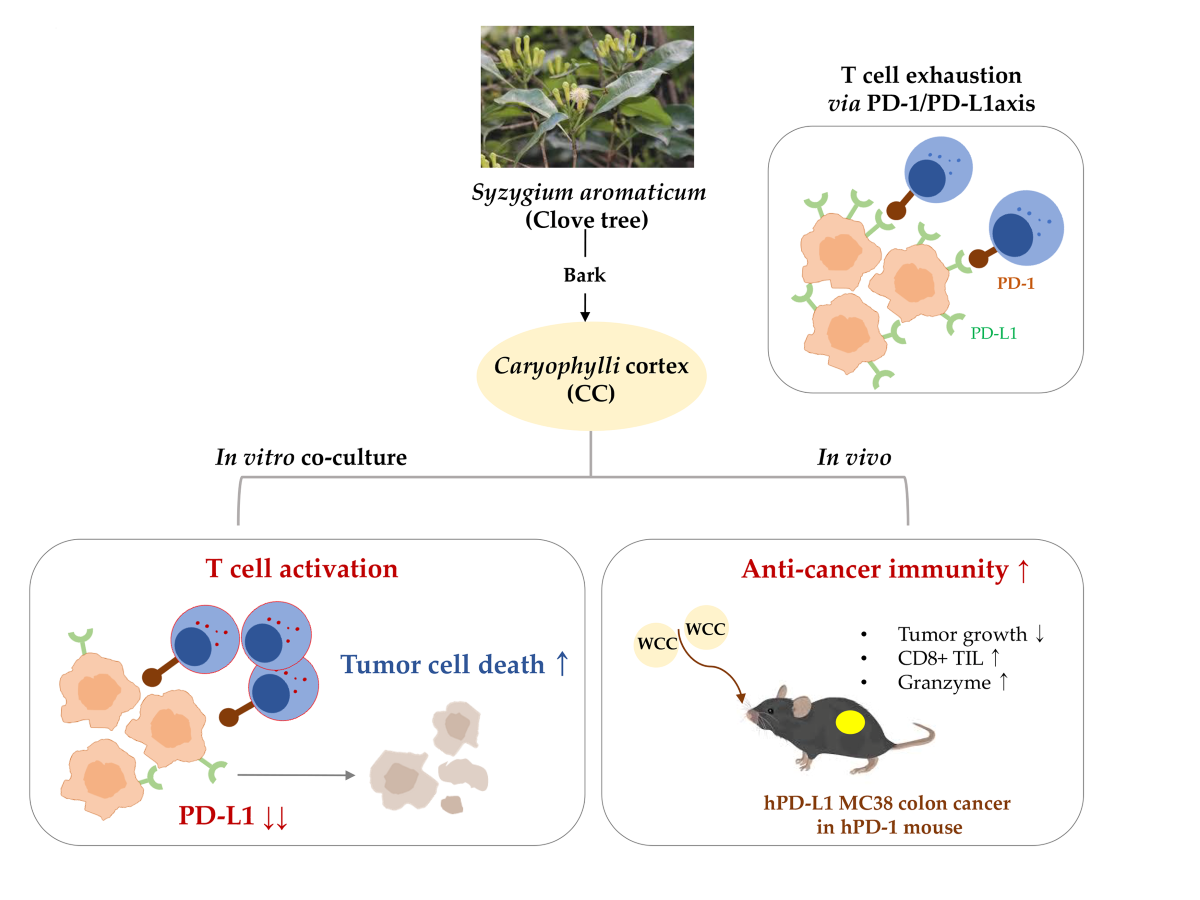

The clove tree Syzygium aromaticum is an evergreen tree in family Myrtaceae that is cultivated in tropical regions in India, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka. Its flower buds have been esteemed for centuries for their applications in food preservation, flavoring, perfumery, and traditional medicine [15,16]. Clove flower buds exhibit anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, antimicrobial, antiviral, antioxidant, and hepatoprotective activity [17,18]. Ethanol extracts of clove bark, known as Caryophylli cortex (CC), mitigate diabetes-induced renal damage by inhibiting advanced glycation end-product (AGE)-induced glucotoxicity and oxidative stress [19]. Furthermore, methanol extracts of CC are cytotoxic to MCF-7 breast cancer cells [20]. However, the potential of CC as an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) to enhance anti-tumor immune responses remains unexplored. Therefore, this study investigated whether water (WCC) and ethanol (ECC) extracts of CC might enhance anti-cancer efficacy by reducing PD-L1 expression in cancer cells and activating T cell immunity, thereby disrupting PD-L1-mediated immune tolerance in both in vitro and in vivo experimental models.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of WCC and ECC

Lyophilized powder of WCC (Cat. No. KOC-DW-335) and ECC (Cat. No. KOC-70E-261) were obtained from KOC Biotech (Daejeon, Korea) and dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, #D8418, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) to achieve a final concentration of 100 mg/mL. After filtering through a 0.22-μm disk filter, aliquots were kept at −20°C.

2.2. Cell Lines

The MDA-MB-231 (HTB-26, human breast adenocarcinoma cell line), DLD-1 (CCL-221, human colon adenocarcinoma cell line), HEK-293 (CRL-1573, human embryonic kidney cell line) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Human PD-L1-expressing MC38 cells (hPD-L1/MC38), derived from C57BL/6 murine colon adenocarcinoma cells, were purchased from the Shanghai Model Organisms Center (Shanghai, China). Jurkat T cells expressing the firefly luciferase gene under the control of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) response elements, with constitutive expression of human PD-1 (NFAT/PD-1/Jurkat T cells), were obtained from BPS Bioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). MDA-MB-231, hPD-L1/MC-38, and HEK-293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium with 4.5 g/L glucose (DMEM), while DLD-1 and NFAT/PD-1/Jurkat T cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium. Both culture media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 IU penicillin/100 μg/mL streptomycin (P/S). The cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. DMEM, RPMI, FBS, and P/S were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Hyclone Laboratories Inc. (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Chicago, IL, USA).

2.3. Chemicals and Antibodies

Crystal violet solution (1% aqueous solution, #V5265), collagenase IV, DNase, and trypsin inhibitor were all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). CellTracker Green 5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate (CMFDA, #C7025) dye and recombinant human interferon-γ (IFN-γ, #300-02) was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). APC-conjugated anti-human CD274 (B7-H1, PD-L1, #393610) antibody was purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Antibodies against PD-L1 (#15165) and β-actin (#4970) were all obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA).

2.4. Cell Viability Assay

To determine non-cytotoxic concentrations of WCC and ECC, cell viability was measured using Cell Counting Kit-8 (#CK04, Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, cells (5 × 103/well) were seeded in each well of a 96-well culture plate, allowed to grow overnight, and then treated with increasing doses of WCC, ECC, or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) for 24 h. After removing culture supernatants, the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Viable cells were then quantified using the EZ-Cytox Enhanced Cell Viability Assay Kit (Daeil Lab Service Co., Ltd., Seoul, Republic of Korea) and a SpectraMax3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

2.5. Analysis of Membrane PD-L1 Expression Using Flow Cytometry and Immunoblotting

MDA-MB231 and hPD-L1/MC38 cells were exposed to specified concentrations of WCC and ECC for 24 h. In the case of DLD-1 cells, WCC and ECC were pre-treated for 12 h and then stimulated with 20 ng/mL IFN-γ for 24 h. For flow cytometry analysis, cells were collected, rinsed with wash buffer (2% FBS in PBS), and incubated with APC-conjugated anti-PD-L1 for 30 minutes at 4°C. Following washing, fluorescence levels were quantitatively assessed using a Gallios flow cytometer with Kaluza software (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA). For immunoblotting, cells were harvested, washed with cold PBS, and lysed in RIPA buffer with a protease inhibitor cocktail. After spinning at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C, the cell lysates were collected, and the protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay (#23227; Thermo Fisher Scientific). An equal amount of proteins (25 μg per lane) were then separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to an ImmobilonR-P PVDF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Following incubation with EzBlock Chemi Solution (ATTO Korea, Daejeon, Republic of Korea) for 1 h at 25°C, the membrane was exposed to a specific primary antibody (diluted 1:1,000 in blocking buffer) overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the membrane was washed with TBS-T solution (0.1% Tween in Tris-buffered saline) and then incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (diluted 1:4,000 in blocking buffer) for 1 h at 25°C, followed by another wash with TBS-T solution. The target proteins were visualized using SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and ImageQuant LAS4000 mini (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Protein levels were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institute of Health, USA), and the relative intensities of the bands on the immunoblots from two or three experiments were calculated after normalization to the β-actin value.

2.6. Co-Culture Experiments for T Cell-Mediated Tumor Cell Killing Assay

MDA-MB231 cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well in 24-well culture plates and exposed to different concentrations of WCC and ECC for 24 h. Following the removal of the culture medium, the cells underwent three washes with PBS and were subsequently stained with CellTracker CMFDA dye at a concentration of 2.5 μM for 30 min at 37°C. After two additional washes with PBS, NFAT/PD-1/Jurkat T cells were added to the MDA-MB231 cells labeled with the green dye, and incubated for 24-48 h. Subsequently, the PD-1/Jurkat cells were eliminated, and the remaining MDA-MB231 cells were examined using a fluorescence microscope. To assess cell viability, the cells were stained with a crystal violet solution containing 0.2% crystal violet and 20% methanol for 30 min at 25°C. Following a wash with distilled water, the stained cells were dissolved in a 1% SDS solution and then the absorbance was measured at 590 nm using a SpectraMax3 microplate reader.

2.7. Experimental Mice and Allograft Tumor Model

Mice with humanized PD-1, developed on the C57BL/6J genetic background and genetically modified to express the complete human PD-1 protein (referred to as hPD-1/C57BL/6J), were obtained from the Shanghai Model Organisms Center in China and raised in a controlled environment at the KIOM for research purposes. To establish the humanized PD-1/PD-L1 MC38 tumor allograft model, hPD-L1/MC38 cells (3 × 105 in 200 μL PBS) were injected subcutaneously on the right flank of each hPD-1/C57BL/6J mouse. The tumor's growth was monitored, and its size was measured using digital calipers (Hi-Tech Diamond, Westmont, IL, USA). The experiments conducted followed the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (KIOM) and were authorized by the KIOM IACUC under approval number KIOM-D-21-091.

2.8. Isolation of Tumor Infiltrating CD8+ T Cells and Co-Culture with hPD-L1/MC38 Cells

To isolate tumor-infiltrating T cells (TILs), tumor masses from hPD-L1/MC-38 tumors in hPD-1 mice were removed, cut into small pieces, and then digested in RPMI media containing collagenase IV (1 mg/mL), DNase (0.1 mg/mL), and trypsin inhibitor (1 mg/mL) for 40 min at 37°C. The digested cells were then filtered through mesh cell strainers (SPL Life Sciences, Pocheon, Korea) of decreasing sizes (100-μm, 70-μm, and 40-μm) to obtain a single-cell suspension. CD8+ TILs were isolated using immunomagnetic separation with a Mouse CD8+ T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Waltham, MA, USA) and then activated with CD3/CD28 magnetic Dynabeads (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 24 h at 37°C. Simultaneously, hPD-L1/MC38 cells were treated with different concentrations of WCC and ECC for 24 h. After washing, the activated CD8+ TILs (Effector cells, E) were added to the WCC- or ECC-treated hPD-L1/MC38 cells (Target cells, T) at a ratio of E:T=5:1. The cells were than incubated for 48 h, and the viable hPD-L1/MC38 cells were identified after crystal violet staining. Quantitation was performed using a SpectraMax3 microplate reader as described above.

2.9. NFAT Luciferase Activity Assay

To assess T cell activity in NFAT/PD-1/Jurkat T cells following co-culture with MDA-MB231 cells or HEK-293 cells, NFAT luciferase activity was measured using Luciferase Assay System (#E4550, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, NFAT/PD-1/Jurkat T cells were collected and lysed using luciferase cell culture lysis buffer. After mixing the cell lysates and luciferase assay reagent, the luminescence was immediately measured using a SpectraMax Luminometer (Molecular Devices).

2.10. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The concentrations of IL-2 and granzyme B, which are released by activated T cells, were quantified using ELISA following the manufacturer's instructions. The BD OptEIATM Human IL-2 ELISA Set (#555190, BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), human Granzyme B SimpleStep ELISA Kit (ab235635, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), BD OptEIATM Mouse IL-2 ELISA Set (#555148, BD Biosciences), and Granzyme B Mouse ELISA Kit (#88-8022, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were utilized for analyzing the co-culture supernatants or mouse sera.

2.11. Assay for Blocking the Interaction Between PD-1 and PD-L1

To examine the effects of WCC and ECC on the PD-1 and PD-L1 interaction, competitive ELISA was performed using PD-1: PD-L1 Inhibitor Screening Assay Kit (#72005, BPS Bioscience Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. In brief, recombinant hPD-L1 (#71104, BPS Bioscience) was immobilized on 96-well plates at a concentration of 1 µg/mL (100 µL per well) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The plates were then washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween (PBS-T), blocked for 1 h at 25°C with PBS-T containing 2% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA), and washed again three times. Various concentrations of WCC and ECC were added to the wells, followed by incubation for 1 h at 25°C. Subsequently, biotinylated hPD-1 (#71109, BPS Bioscience) was added to the wells and incubated for 2 h at 25°C. The wells were washed three times with PBS-T and then 100 µL HRP-conjugated streptavidin was applied to each well. Following a 1-hour incubation, the plates underwent three washes with PBS-T. The relative chemiluminescence was quantified using an ECL solution and a SpectraMax L Luminometer. For the positive control, an anti-PD-1 neutralizing antibody (α-PD-1, #71120, BPS Bioscience) was used.

2.12. In Vivo Anti-Tumor Activity of WCC in Humanized PD-1/PD-L1 Mouse Model

To create tumor masses, hPD-L1/MC38 cells (3 × 105 cells suspended in 200 μL of PBS) were injected under the skin on the right side of each hPD-1/C57BL/6J mouse. The growth of the tumors was monitored and measured twice a week using a digital caliper. Once the tumor volume reached 100-150 mm3 on day 12, the mice were randomly assigned to one of four groups (n = 5 per group): a Normal group (no tumor + PBS), a Control group (tumor + PBS), and WCC groups receiving either a low or high dose of WCC (tumor + 100 or 300 mg/kg WCC). The mice were orally administered either the PBS or WCC daily for 15 days. Tumor volume and body weight were recorded on days 1, 4, 8, 11, 14, and 16. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula: Tumor volume = (a2 × b) × 0.52, where a and b represent the shortest and the longest diameters of the tumors, respectively. After the tumors were removed and weighed, the tumor suppression rate (TSR) was determined using the formula: TSR (%) = [(Vc – Vt)/Vc] × 100, where Vc represents the tumor volume of the control group and Vt represents the tumor volume of the WCC treatment group.

2.13. Immunohistochemistry

Tumors were fixed in a 10% formalin solution, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. The paraffin block was then sliced into consecutive 10-μm sections, which were placed on a microscope slide. To conduct immunostaining, the sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, subjected to epitope retrieval, and had peroxidase activity blocked. Subsequently, the sections were treated with antibodies targeting CD8 (#98941) and granzyme B (#46901) overnight, and then visualized using a DAKO EnVision Kit (DAKO, Jena, Germany). Following counterstaining with Mayer’s hematoxylin, the images were examined using an Olympus BX53 microscope and an XC10 digital camera (Tokyo, Japan).

2.14. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.5.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Results are shown as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from multiple trials. Variations between groups were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05 (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). All experiments, except for those conducted in vivo, were repeated at least three times.

4. Discussion

ICIs play a pivotal role in the management of malignant tumors, augmenting therapeutic strategies and enhancing cancer patient survival rates [24]. The PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway is an important target in the therapeutic management of various malignancies, as PD-L1 is expressed across a diverse range of tumor types and in immune cells present within the tumor microenvironment. Blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction facilitates the targeting of cancer cells by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. The inhibition of this interaction can result in significant antitumor responses [1,2,23]. The regulation of PD-L1 expression has emerged as a critical factor in ICI therapy, as its levels are correlated with patient responsiveness, making it an effective predictive biomarker [4,8]. Elevated PD-L1 expression frequently signifies a more immunosuppressive microenvironment, which may increase susceptibility to immune checkpoint blockade. Current research is focused on elucidating the regulatory pathways governing PD-L1 expression, which are influenced by oncogenic signaling, inflammatory cytokines, genetic alterations, and epigenetic modifications. Furthermore, strategies aimed at modulating PD-L1 expression, as well as combination therapies that target PD-L1 and other immune checkpoints, are under investigation to enhance the efficacy of ICIs and expand patient eligibility.

To assess the efficacy of an ICI, it is crucial to distinguish its therapeutic effects from cytotoxic effects exerted on cancer cells. For example, berberine has been shown to exhibit anti-cancer properties via mechanisms such as the inhibition of cell proliferation, induction of cell cycle arrest, and promotion of either apoptosis or autophagy across various cancer types [23,24]. Notably, at concentrations that do not elicit cytotoxic effects in cancer cells, berberine enhances the sensitivity of these cells to co-cultured T cells by downregulating PD-L1 expression on their surface [14]. Furthermore, berberine showed antitumor effects in Lewis tumor xenograft models by augmenting the immune response of tumor-infiltrating cells [27].

Previously, we demonstrated that extracts of Salvia plebeia, Oenothera biennis, and Korean red ginseng inhibit the binding of PD-1 to PD-L1, thereby showing significant anticancer effects in humanized PD-1/PD-L1 knock-in mouse models of colorectal cancer [28,29,30]. Furthermore, we validated the synergistic anticancer effects of combination therapy with established colorectal cancer treatments, such as oxaliplatin and pembrolizumab, combined with herbal extracts, such as unripe Rubus coreanus and Sanguisorba radix [31,32]. Our recent study showed that cosmosiin, a natural flavone glycoside, enhances T cell antitumor activity and induces apoptosis in cancer cells by inhibiting inducible PD-L1 expression, indicating its potential as an ICI [12].

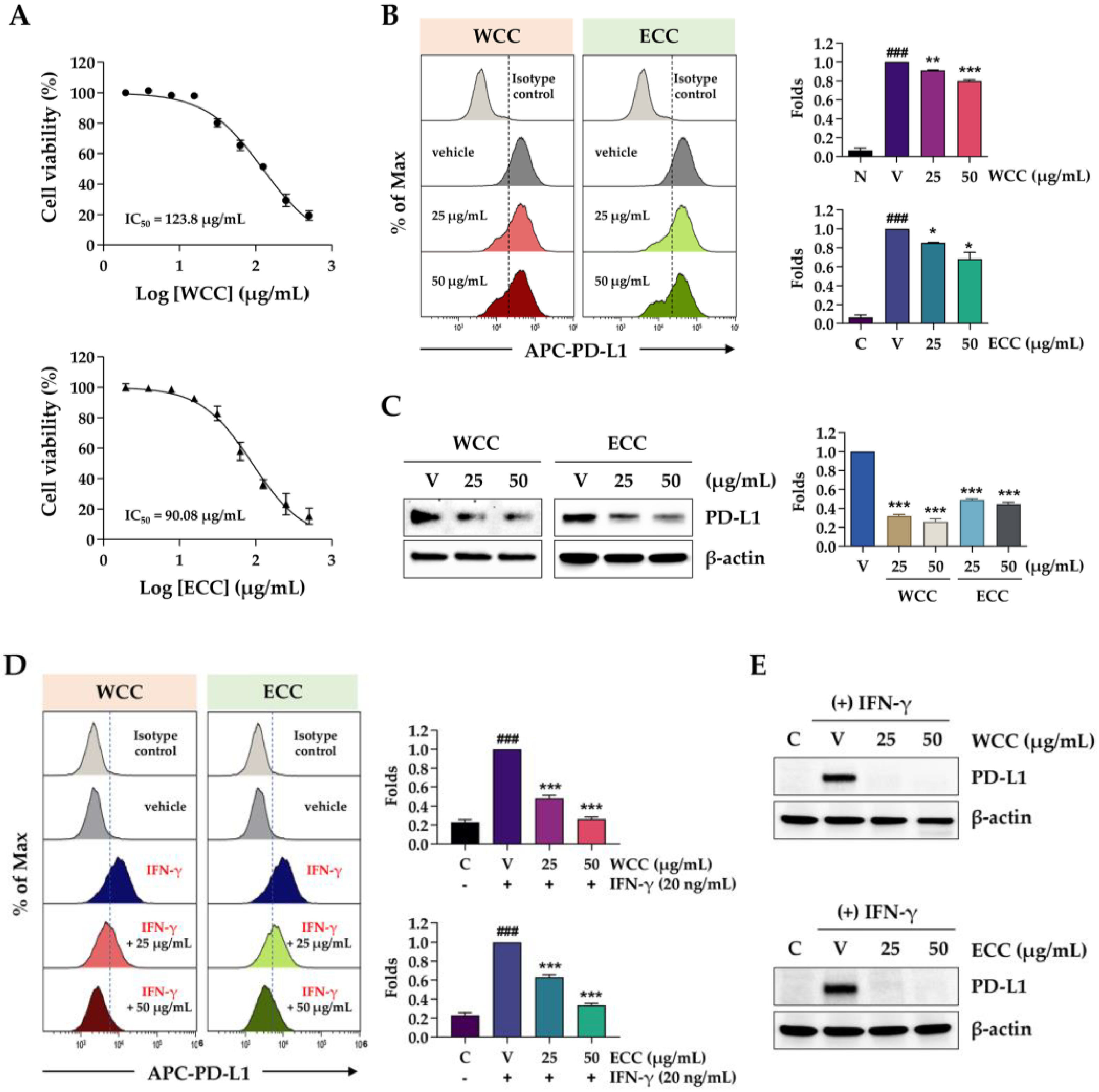

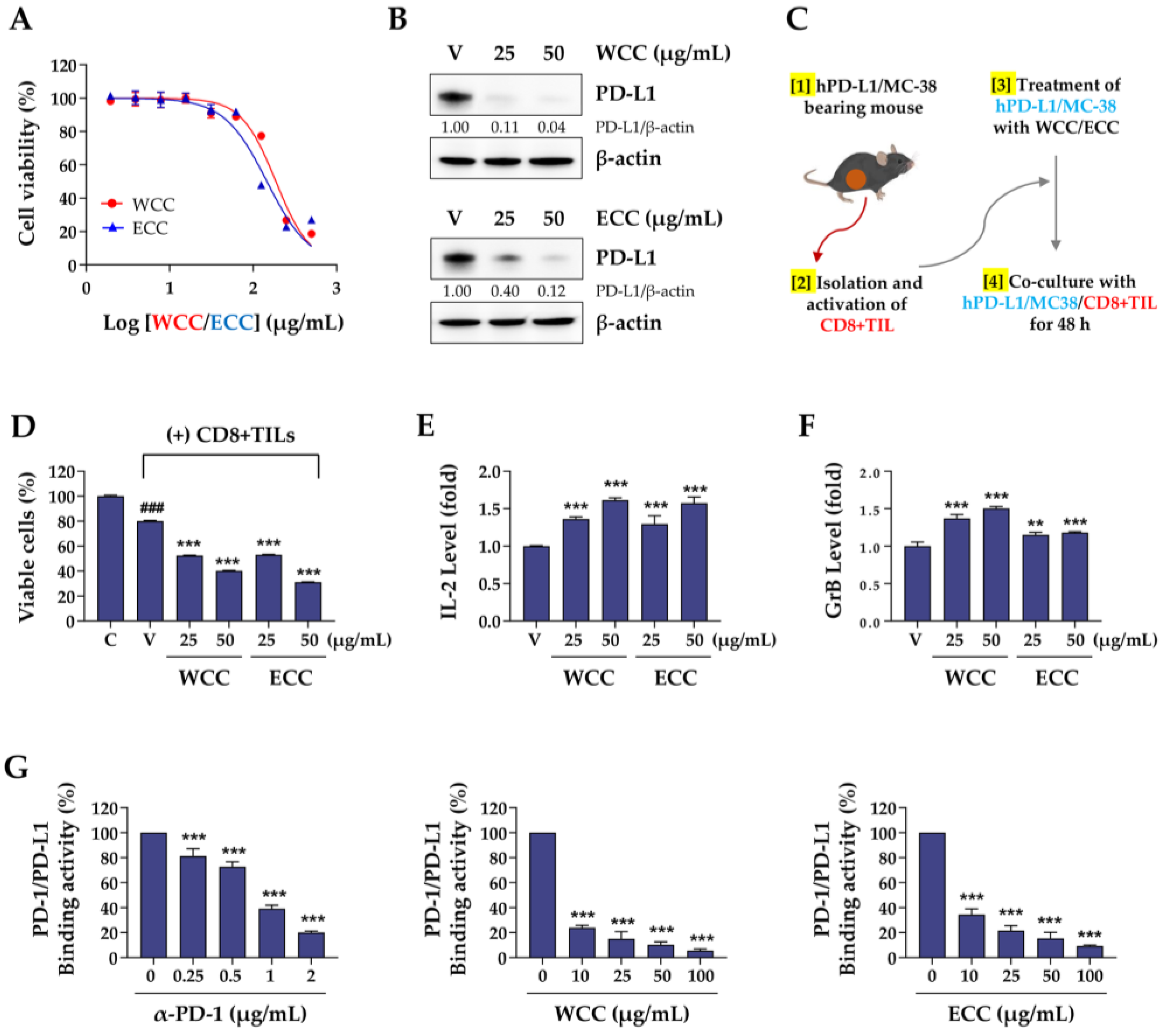

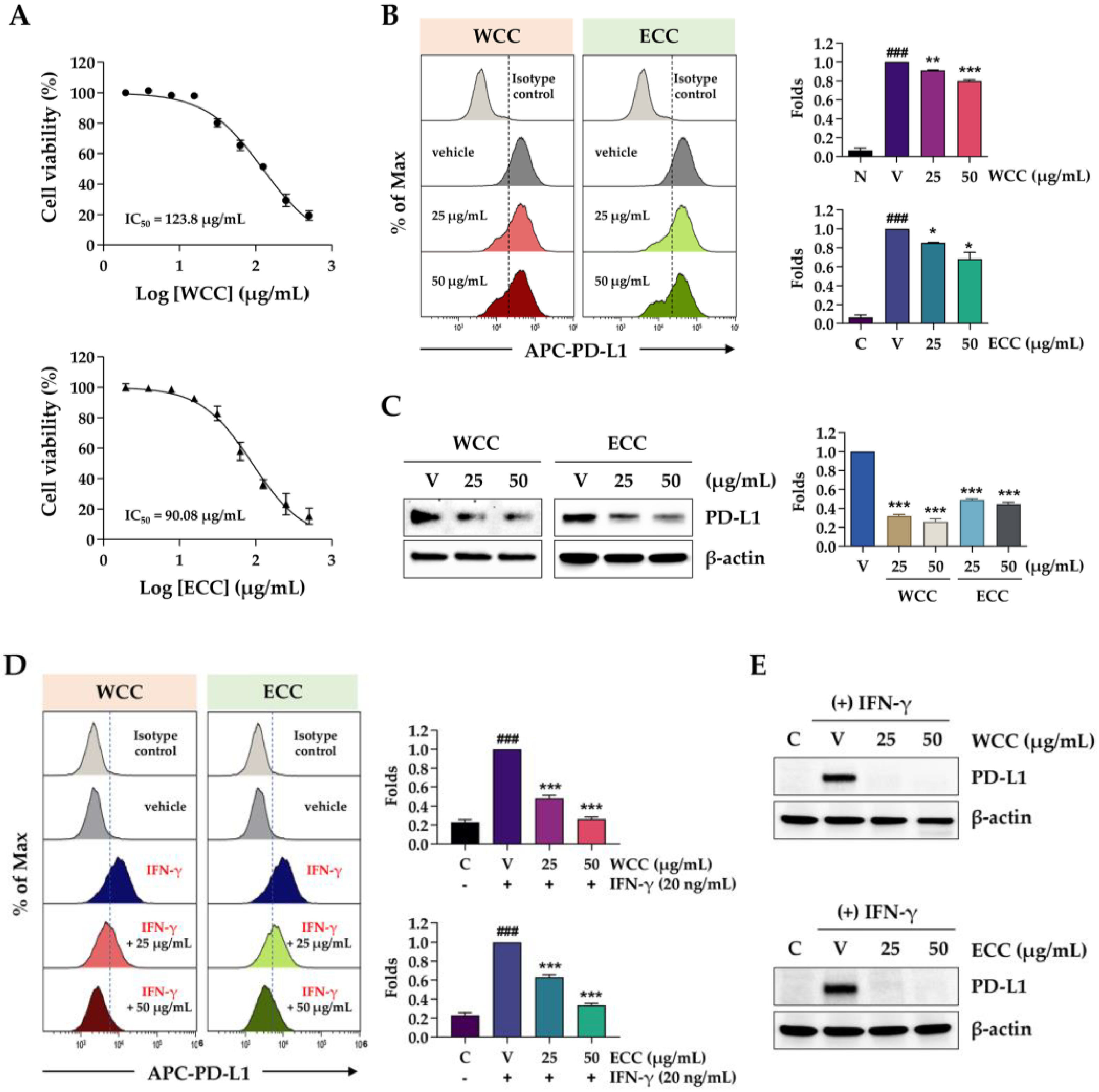

In this study, we investigated the potential of CC extract as an ICI to enhance anticancer immunity and induce apoptosis in cancer cells. We showed that both WCC and ECC significantly reduced the expression of both constitutive and inducible PD-L1 at non-toxic concentrations (

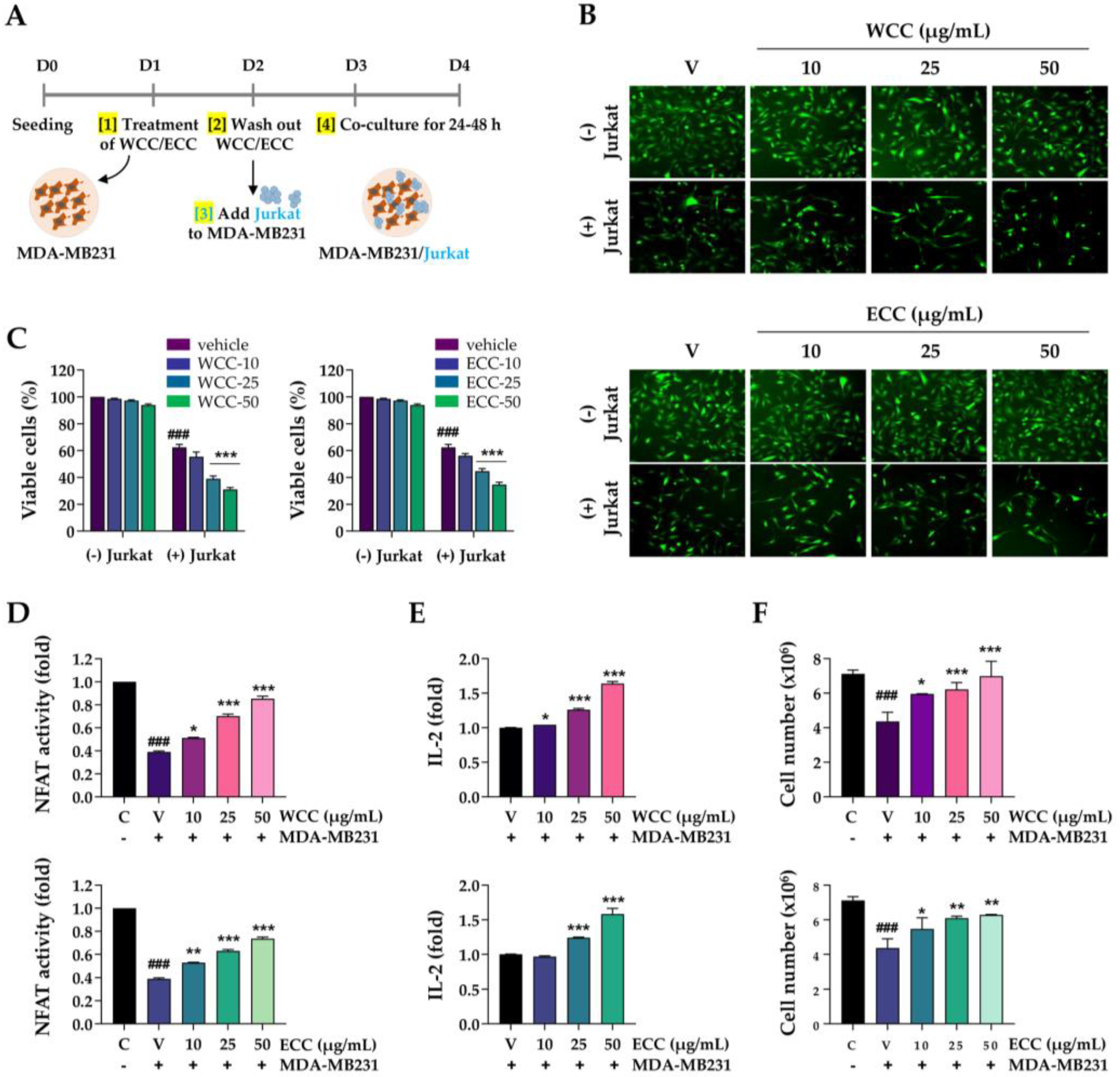

Figure 1). When administered to T cells, these extracts effectively enhanced immune activity by increasing NFAT activity. In co-culture experiments involving PD-L1-expressing cancer cells and PD-1-expressing Jurkat T cells, approximately 50% of the Jurkat T cells were eliminated due to interactions between PD-1 and PD-L1. However, pretreating cancer cells with WCC and ECC to inhibit PD-L1 expression resulted in increased T cell activity and survival rates, while also promoting cancer cell death (

Figure 3). Before evaluating their efficacy in a humanized PD-1/PD-L1 MC-38 mouse model of colon cancer, we assessed these extracts in ex vivo co-culture with hPD-L1/MC-38 cells and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ TILs. As expected, both WCC and ECC nearly completely downregulated PD-L1 levels in hPD-L1/MC-38 cells. Co-culture with CD8+ TILs resulted in a two- to threefold reduction in the viability of hPD-L1/MC-38 cells, while significantly enhancing T cell activity and cytotoxicity (

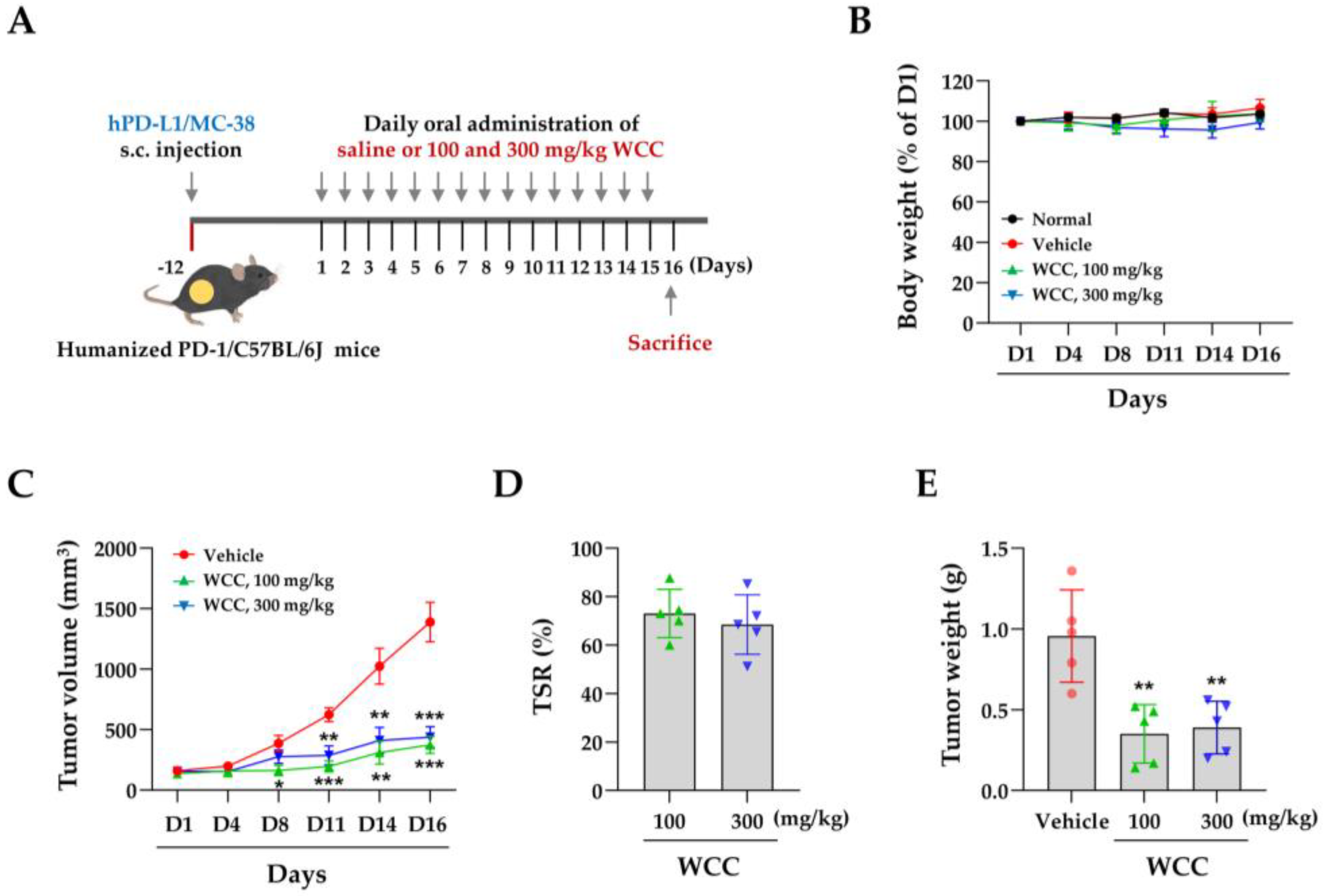

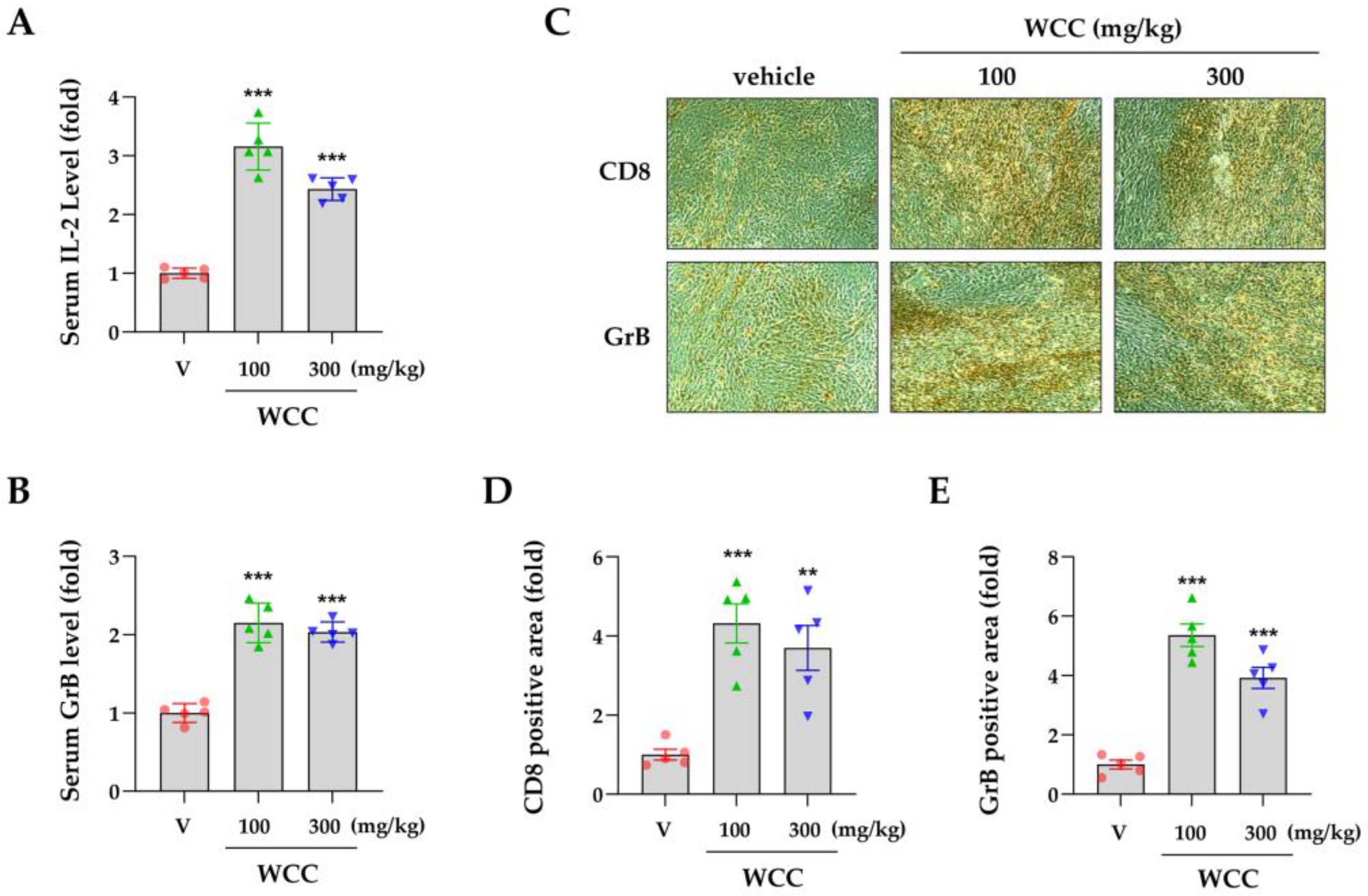

Figure 4). These findings strongly suggest that CC extract can decrease PD-L1 expression in multiple cancer types, augmenting anticancer immune responses. In a mouse model of colon cancer with human PD-1 and PD-L1, WCC administration reduced tumor growth by approximately 70% and elevated intra-tumor CD8+ T cells, IL-2, and GrB (

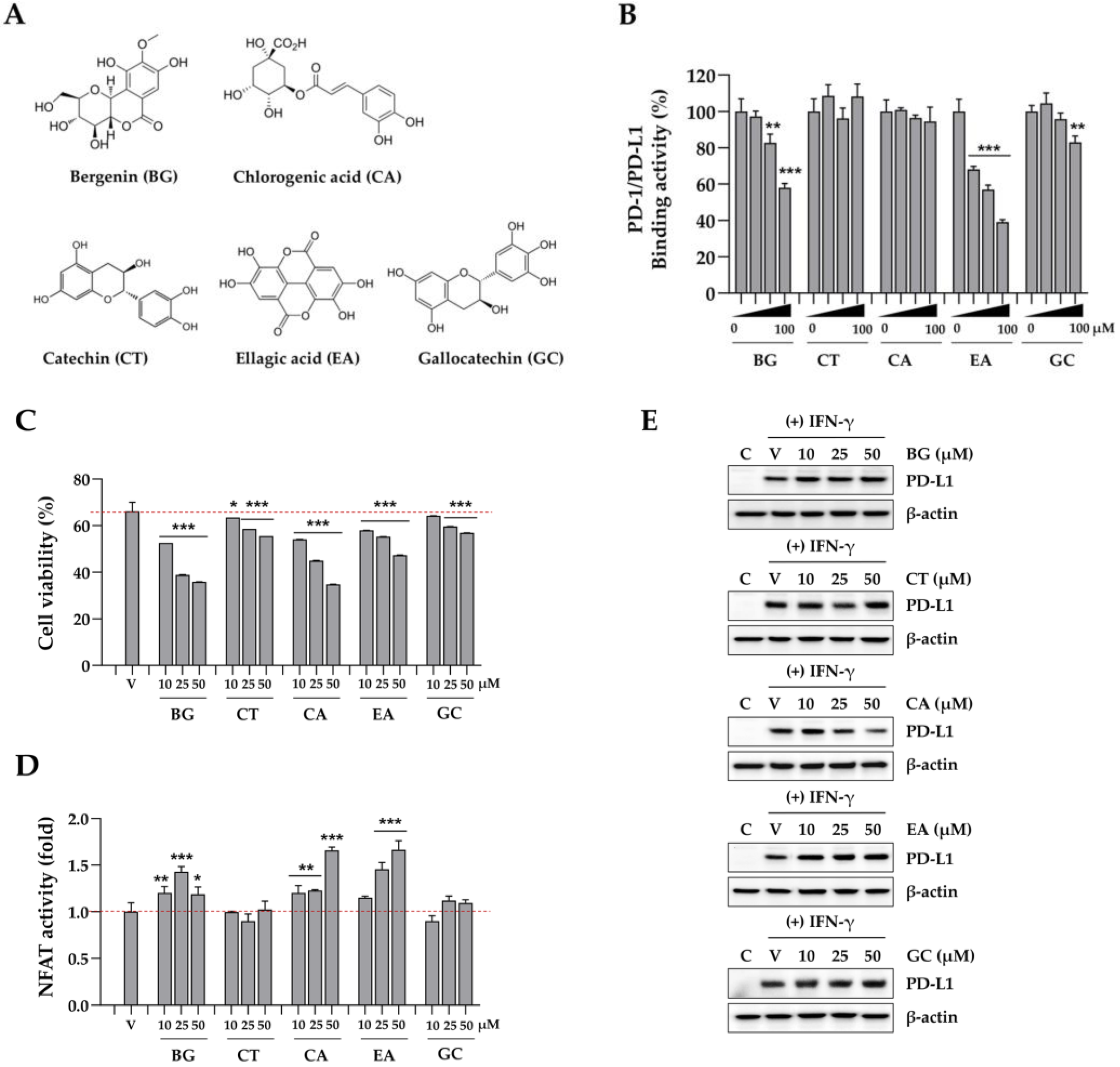

Figure 5 and 6). Our analysis of CC extract components revealed that both BG and EA elicit anticancer immune responses by inhibiting the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1 (

Figure 7). These findings are consistent with those of Kim

et al., who identified EA as a potent constituent of black raspberries, demonstrating its effectiveness in immune checkpoint blockade via the inhibition of the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction [33]. Notably, although EA decreased PD-L1 expression in the UM-UL3 and T24 cell lines [34], it did not affect the reduction of IFN-γ-induced PD-L1 expression in our study. By contrast, CA has been shown to inhibit IFN-γ-induced PD-L1 expression via the p-STAT1-IRF1 signaling pathway, thereby enhancing T cell activity and exhibiting a significant antitumor effect, as well as a synergistic effect when administered with anti-PD-1 antibodies [35]. In this study, we also observed that CA effectively reduced PD-L1 expression and increased both cancer cell apoptosis and T cell activity in co-cultures with cancer cells. Therefore, these components function as PD-1/PD-L1 ICIs via multiple mechanisms, enhancing the overall anticancer immune efficacy of CC extract.

Figure 1.

Effects of WCC and ECC on the PD-L1 expression in cancer cells. (A) MDA-MB231 cells were treated with the increasing concentrations of WCC and ECC. After 24 h, relative cell viability compared with vehicle-treated control cells was calculated and presented as the means ± SEM (n = 3). (B) MDA-MB231 cells were treated with 25 and 50 μg/mL of WCC and ECC for 24 h, and then the levels of membrane PD-L1 were detected by flow cytometry. Relative fluorescence intensity compared to vehicle-treated control cells was shown as the means ± SEM (n = 3). (C) After treatment with 25 and 50 μg/mL of WCC and ECC for 24 h, PD-L1 expression in MDA-MB231 cells was analyzed by immunoblotting. Relative band intensities after normalization to β-actin expression were presented as the means ± SEM (n = 3). (D) DLD-1 cells were pretreated with 25 and 50 μg/mL of WCC and ECC for 6 h, and then stimulated with 20 ng/mL IFN-γ for 24 h. Membrane PD-L1 was detected by flow cytometry and relative intensity compared to IFN-γ/vehicle-treated cells was shown as the means ± SEM (n = 6). (E) DLD-1 cells pretreated with WCC and ECC were stimulated with IFN-γ for 40 h. Whole cell lysates were analyzed for the PD-L1 expression by immunoblotting. ###p< 0.001 vs. isotype control, *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 vs. vehicle-treated cells.

Figure 1.

Effects of WCC and ECC on the PD-L1 expression in cancer cells. (A) MDA-MB231 cells were treated with the increasing concentrations of WCC and ECC. After 24 h, relative cell viability compared with vehicle-treated control cells was calculated and presented as the means ± SEM (n = 3). (B) MDA-MB231 cells were treated with 25 and 50 μg/mL of WCC and ECC for 24 h, and then the levels of membrane PD-L1 were detected by flow cytometry. Relative fluorescence intensity compared to vehicle-treated control cells was shown as the means ± SEM (n = 3). (C) After treatment with 25 and 50 μg/mL of WCC and ECC for 24 h, PD-L1 expression in MDA-MB231 cells was analyzed by immunoblotting. Relative band intensities after normalization to β-actin expression were presented as the means ± SEM (n = 3). (D) DLD-1 cells were pretreated with 25 and 50 μg/mL of WCC and ECC for 6 h, and then stimulated with 20 ng/mL IFN-γ for 24 h. Membrane PD-L1 was detected by flow cytometry and relative intensity compared to IFN-γ/vehicle-treated cells was shown as the means ± SEM (n = 6). (E) DLD-1 cells pretreated with WCC and ECC were stimulated with IFN-γ for 40 h. Whole cell lysates were analyzed for the PD-L1 expression by immunoblotting. ###p< 0.001 vs. isotype control, *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 vs. vehicle-treated cells.

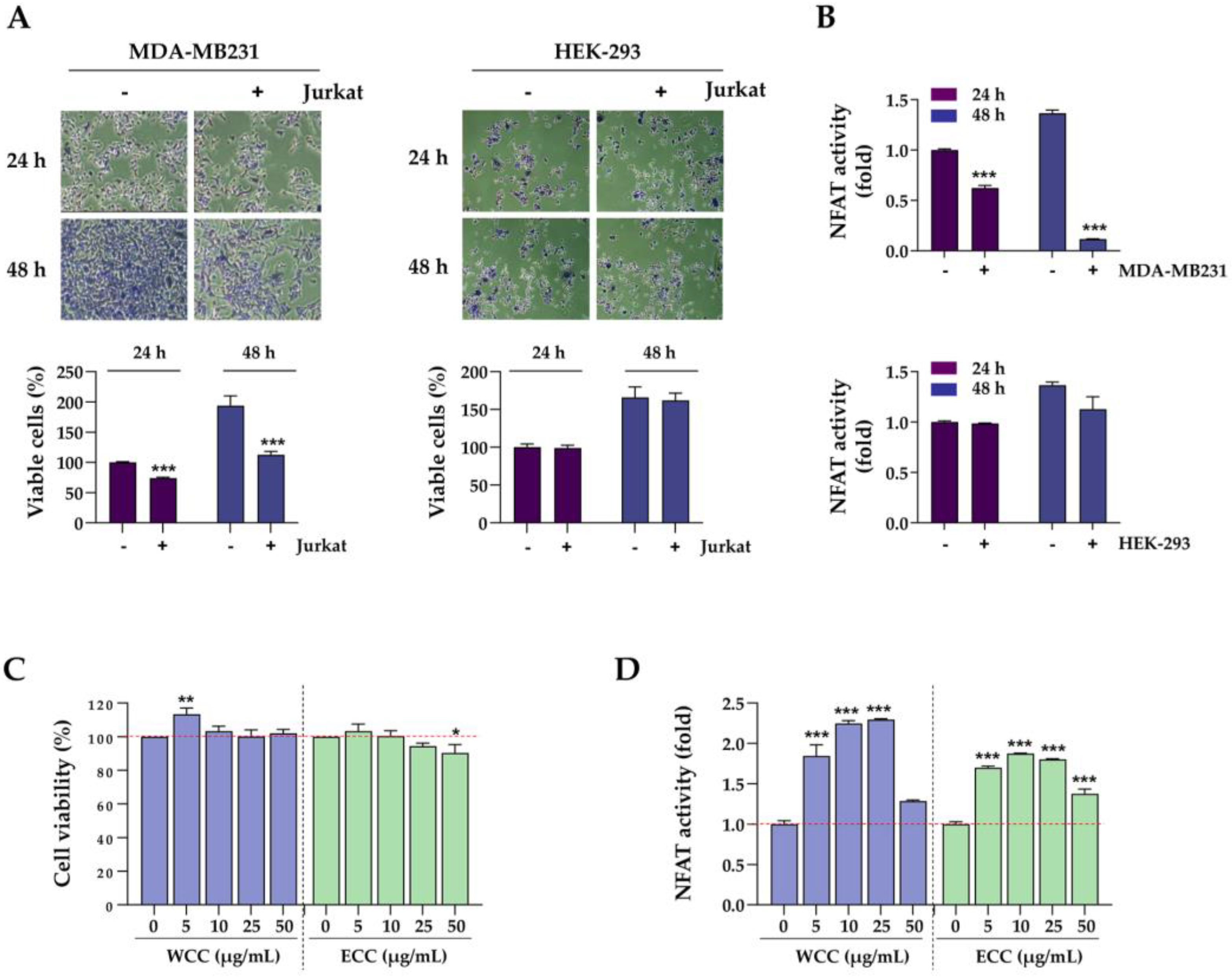

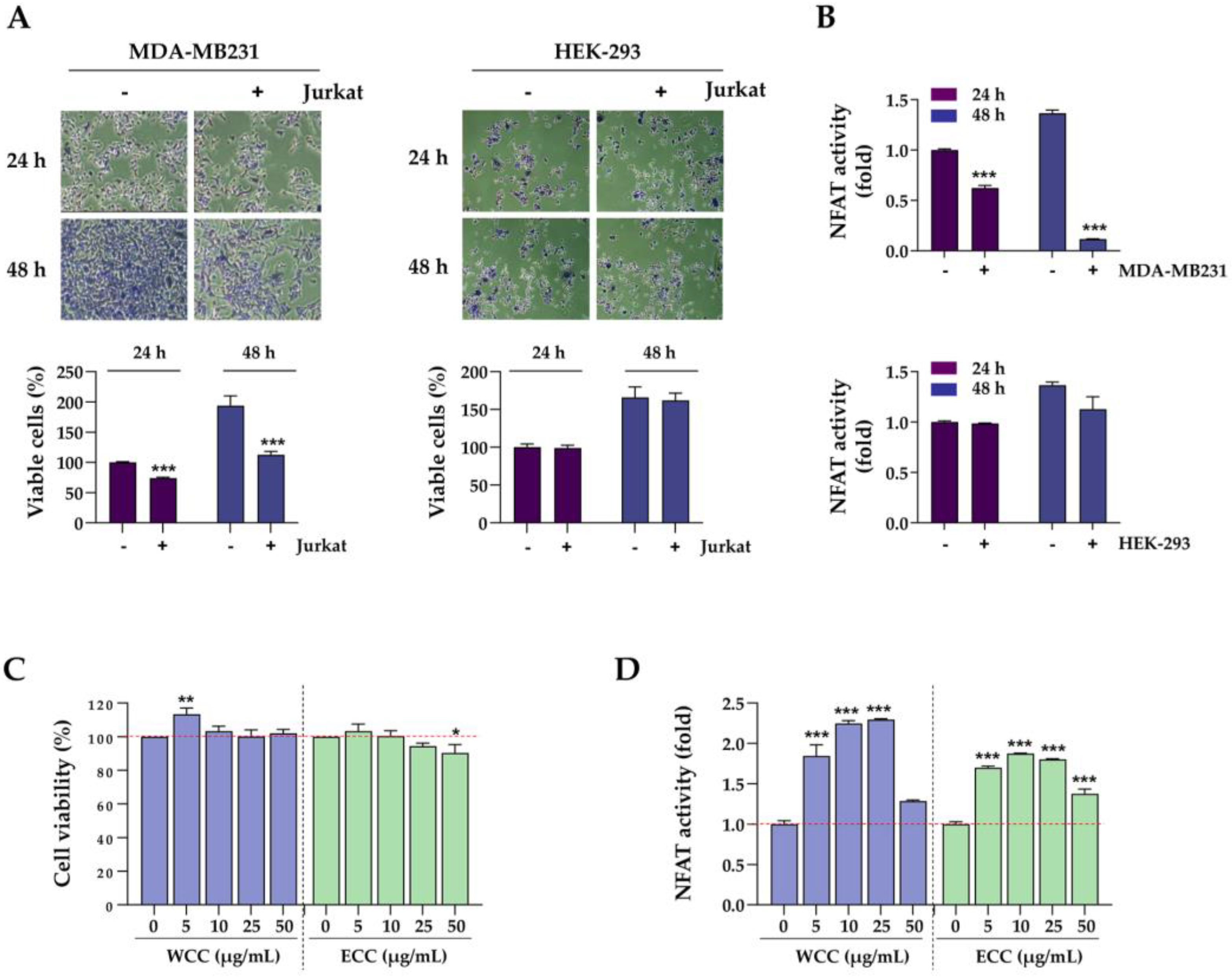

Figure 2.

Effects of PD-1/PD-L1 interaction on the cell viability of cancer cells and the NFAT activity of T cells. (A) MDA-MB231 and HEK-293 cells were seeded on culture plates, incubated overnight, and then co-cultured with NFAT/PD-1/Jurkat T (Jurkat) cells at a ratio of 1:10. After 24 and 48 h, Jurkat cells were removed, and the remaining MDA-MB231 and HEK-293 cells were stained with crystal violet solution. Viable cells were observed under a microscope and quantified. ***p< 0.001 vs. w/o Jurkat cells. (B) After co-culturing with MDA-MB231 and HEK-293 cells for 24 h, NFAT activity in Jurkat cells was assessed. ***p< 0.001 vs. w/o MDA-MB231 cells. (C) Jurkat cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of WCC and ECC for 24 h, and then the cell viability was measured using a CCK assay. (D) After treating Jurkat cells with WCC and ECC for 24 h, NFAT activity was determined. Data in each experiment are presented as the means ± SEM (n = 3). *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 vs. vehicle-treated cells.

Figure 2.

Effects of PD-1/PD-L1 interaction on the cell viability of cancer cells and the NFAT activity of T cells. (A) MDA-MB231 and HEK-293 cells were seeded on culture plates, incubated overnight, and then co-cultured with NFAT/PD-1/Jurkat T (Jurkat) cells at a ratio of 1:10. After 24 and 48 h, Jurkat cells were removed, and the remaining MDA-MB231 and HEK-293 cells were stained with crystal violet solution. Viable cells were observed under a microscope and quantified. ***p< 0.001 vs. w/o Jurkat cells. (B) After co-culturing with MDA-MB231 and HEK-293 cells for 24 h, NFAT activity in Jurkat cells was assessed. ***p< 0.001 vs. w/o MDA-MB231 cells. (C) Jurkat cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of WCC and ECC for 24 h, and then the cell viability was measured using a CCK assay. (D) After treating Jurkat cells with WCC and ECC for 24 h, NFAT activity was determined. Data in each experiment are presented as the means ± SEM (n = 3). *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 vs. vehicle-treated cells.

Figure 3.

Effects of WCC and ECC on the cancer cells and T cells in the co-culture condition. (A) Experimental scheme of cancer cells and T cell co-culture. (B) MDA-MB231 cells labeled with green dye were treated with WCC and ECC for 24 h, then co-cultured with or without Jurkat cells for another 24 h. Subsequently, the Jurkat cells were removed, and the remaining cancer cells were examined under a fluorescence microscope. (C) After co-culture, the remaining cancer cells were stained with crystal violet solution and quantified. (D) After co-culture, the NFAT activity of Jurkat cells were measured. (E) IL-2 levels in culture supernatants were determined using IL-2 ELISA. (F) After co-culture, Jurkat cells were harvested, and the number of viable cells was counted. Data are presented as the means ± SEM (n = 3). ###p< 0.001 vs. control cells, *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 vs. vehicle-treated cells.

Figure 3.

Effects of WCC and ECC on the cancer cells and T cells in the co-culture condition. (A) Experimental scheme of cancer cells and T cell co-culture. (B) MDA-MB231 cells labeled with green dye were treated with WCC and ECC for 24 h, then co-cultured with or without Jurkat cells for another 24 h. Subsequently, the Jurkat cells were removed, and the remaining cancer cells were examined under a fluorescence microscope. (C) After co-culture, the remaining cancer cells were stained with crystal violet solution and quantified. (D) After co-culture, the NFAT activity of Jurkat cells were measured. (E) IL-2 levels in culture supernatants were determined using IL-2 ELISA. (F) After co-culture, Jurkat cells were harvested, and the number of viable cells was counted. Data are presented as the means ± SEM (n = 3). ###p< 0.001 vs. control cells, *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 vs. vehicle-treated cells.

Figure 4.

Effects of WCC and ECC on anti-cancer activity of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells in a co-culture setting. (A) After treating hPD-L1/MC-38 cells with WCC and ECC for 24 h, cell viability was examined by CCK assay. (B) The levels of PD-L1 protein in hPD-L1/MC-38 cells treated with WCC and ECC were assessed using western blotting. Relative values were calculated after normalizing to β-actin. (C) Experimental design of co-culture with hPD-L1/MC38 cells and CD8+ TIL cells. (D) After co-culturing with CD8+ TILs, the viability of the remaining cancer cells was assessed. (E-F) After co-culture, IL-2 (E) and granzyme B (GrB) (F) levels in culture supernatants were measured using ELISA. (G) PD-1/PD-L1 binding activity in the presence or absence of WCC and ECC was determined by competitive ELISA. Anti-PD-1 antibody was used as a positive control. Data are presented as the means ± SEM (n = 3). ###p< 0.001 vs. control cells, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 vs. vehicle-treated cells.

Figure 4.

Effects of WCC and ECC on anti-cancer activity of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells in a co-culture setting. (A) After treating hPD-L1/MC-38 cells with WCC and ECC for 24 h, cell viability was examined by CCK assay. (B) The levels of PD-L1 protein in hPD-L1/MC-38 cells treated with WCC and ECC were assessed using western blotting. Relative values were calculated after normalizing to β-actin. (C) Experimental design of co-culture with hPD-L1/MC38 cells and CD8+ TIL cells. (D) After co-culturing with CD8+ TILs, the viability of the remaining cancer cells was assessed. (E-F) After co-culture, IL-2 (E) and granzyme B (GrB) (F) levels in culture supernatants were measured using ELISA. (G) PD-1/PD-L1 binding activity in the presence or absence of WCC and ECC was determined by competitive ELISA. Anti-PD-1 antibody was used as a positive control. Data are presented as the means ± SEM (n = 3). ###p< 0.001 vs. control cells, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 vs. vehicle-treated cells.

Figure 5.

Effects of oral administration of WCC on the growth of hPD-L1/MC-38 tumors in humanized PD-1 mice. (A) Experimental scheme for tumor injection, administration of WCC, and sacrifice. (B) Body weight changes compared to day 1 (D1) in normal and tumor-bearing mice were measured on days 4, 8, 11, 14, and 16 after WCC administration. (C) The size of hPD-L1/MC-38 tumor mass was measured on days 4, 8, 11, 14, and 16 following the administration of either WCC or vehicle. (D) Tumor suppression rate by WCC administration was compared to control mice given a vehicle. (E) On day 16, mice were euthanized, and their tumors were removed and weighed. Data are presented as the means ± SEM (n = 5). *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 vs. vehicle-treatment.

Figure 5.

Effects of oral administration of WCC on the growth of hPD-L1/MC-38 tumors in humanized PD-1 mice. (A) Experimental scheme for tumor injection, administration of WCC, and sacrifice. (B) Body weight changes compared to day 1 (D1) in normal and tumor-bearing mice were measured on days 4, 8, 11, 14, and 16 after WCC administration. (C) The size of hPD-L1/MC-38 tumor mass was measured on days 4, 8, 11, 14, and 16 following the administration of either WCC or vehicle. (D) Tumor suppression rate by WCC administration was compared to control mice given a vehicle. (E) On day 16, mice were euthanized, and their tumors were removed and weighed. Data are presented as the means ± SEM (n = 5). *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 vs. vehicle-treatment.

Figure 6.

Effects of oral administration of WCC on the T cell activity in humanized PD-1 mice. (A-B) On day 16, serum from mice in each group was isolated, and the levels of IL-2 (A) and granzyme B (GrB) (B) were determined using ELISA. (C) Representative images of CD8- and GrB-positive areas within tumors from mice administered with WCC or vehicle. (D-E) The relative areas positive for CD8 and granzyme B (GrB) within the tumors of the WCC-treated group were compared to those of the vehicle-treated group. Data are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 5). **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 vs. vehicle-treatment.

Figure 6.

Effects of oral administration of WCC on the T cell activity in humanized PD-1 mice. (A-B) On day 16, serum from mice in each group was isolated, and the levels of IL-2 (A) and granzyme B (GrB) (B) were determined using ELISA. (C) Representative images of CD8- and GrB-positive areas within tumors from mice administered with WCC or vehicle. (D-E) The relative areas positive for CD8 and granzyme B (GrB) within the tumors of the WCC-treated group were compared to those of the vehicle-treated group. Data are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 5). **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 vs. vehicle-treatment.

Figure 7.

Effects of compounds in Caryophylli Cortex extract on the PD-1/PD-L1 axis. (A) The chemical structure of bergenin (BG), catechin (CT), chlorogenic acid (CA), ellagic acid (EA), and gallocatechin (GC). (B) The binding activity of PD-1/PD-L1 in the presence of BG, CT, CA, EA, and GC was evaluated using a competitive ELISA. (C) MDA-MB231 cells were pre-treated with each compound for 24 h, and then co-cultured with Jurkat cells. After 24 h, Jurkat cells were removed, and the remaining MDA-MB231 cells were quantified. (D) Following co-culture, the NFAT activity of Jurkat cells was measured. (E) The levels of IFN-γ-inducible PD-L1 protein in DLD-1 cells were analyzed via western blotting. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 vs. vehicle-treated cells.

Figure 7.

Effects of compounds in Caryophylli Cortex extract on the PD-1/PD-L1 axis. (A) The chemical structure of bergenin (BG), catechin (CT), chlorogenic acid (CA), ellagic acid (EA), and gallocatechin (GC). (B) The binding activity of PD-1/PD-L1 in the presence of BG, CT, CA, EA, and GC was evaluated using a competitive ELISA. (C) MDA-MB231 cells were pre-treated with each compound for 24 h, and then co-cultured with Jurkat cells. After 24 h, Jurkat cells were removed, and the remaining MDA-MB231 cells were quantified. (D) Following co-culture, the NFAT activity of Jurkat cells was measured. (E) The levels of IFN-γ-inducible PD-L1 protein in DLD-1 cells were analyzed via western blotting. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 vs. vehicle-treated cells.