Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Treatment

2.2. Generating CSCs-Enriched Colonospheres

2.3. Isolation and Culture of Human PBMCs

2.4. Immunophenotyping of PBMCs

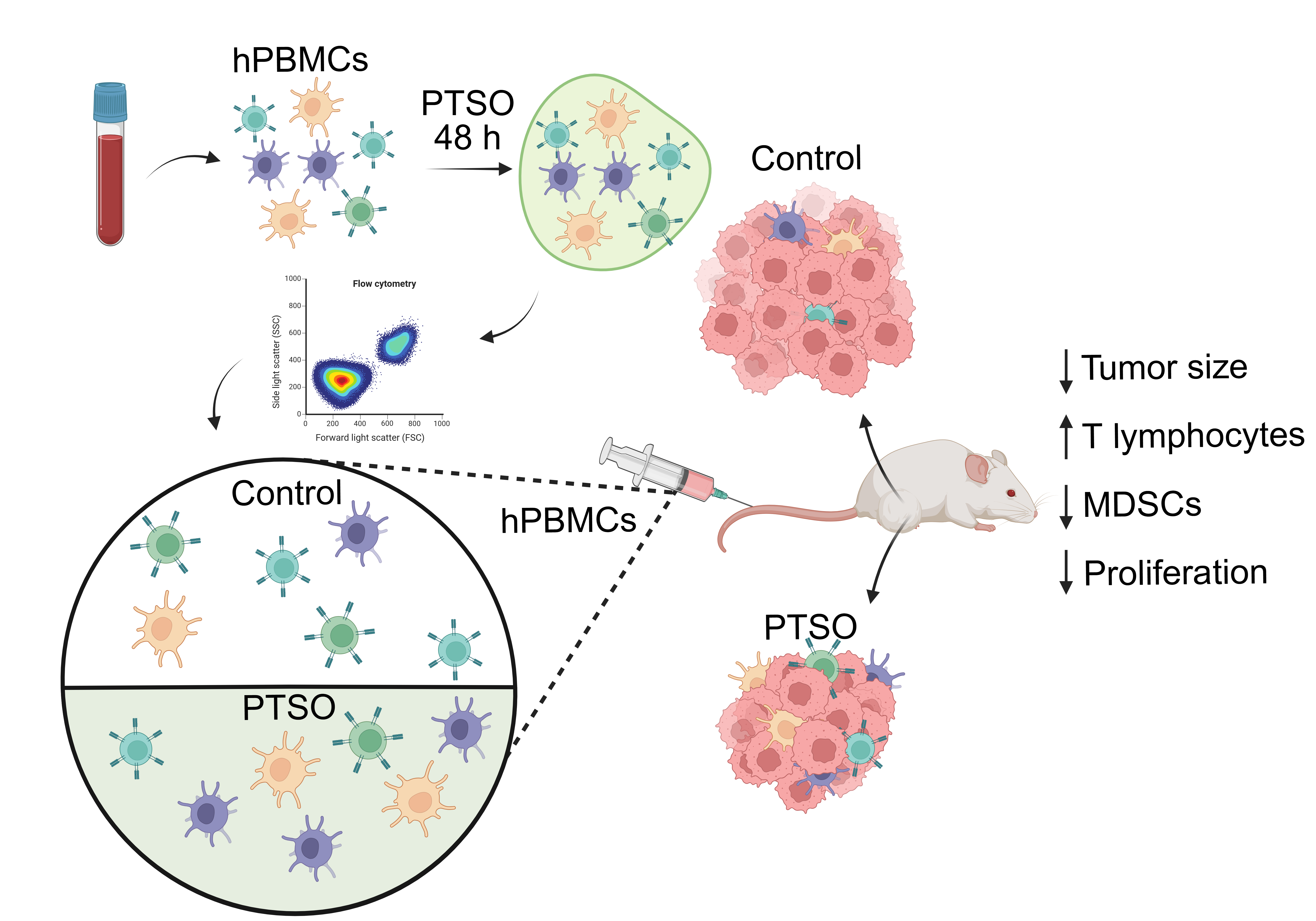

2.5. Immune-Humanized Tumor-Bearing Murine Model

2.6. Immune Profiling of Blood and Tumor Samples

2.7. RNA Extraction and Analysis of Gene Expression

2.8. Histological Studies

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

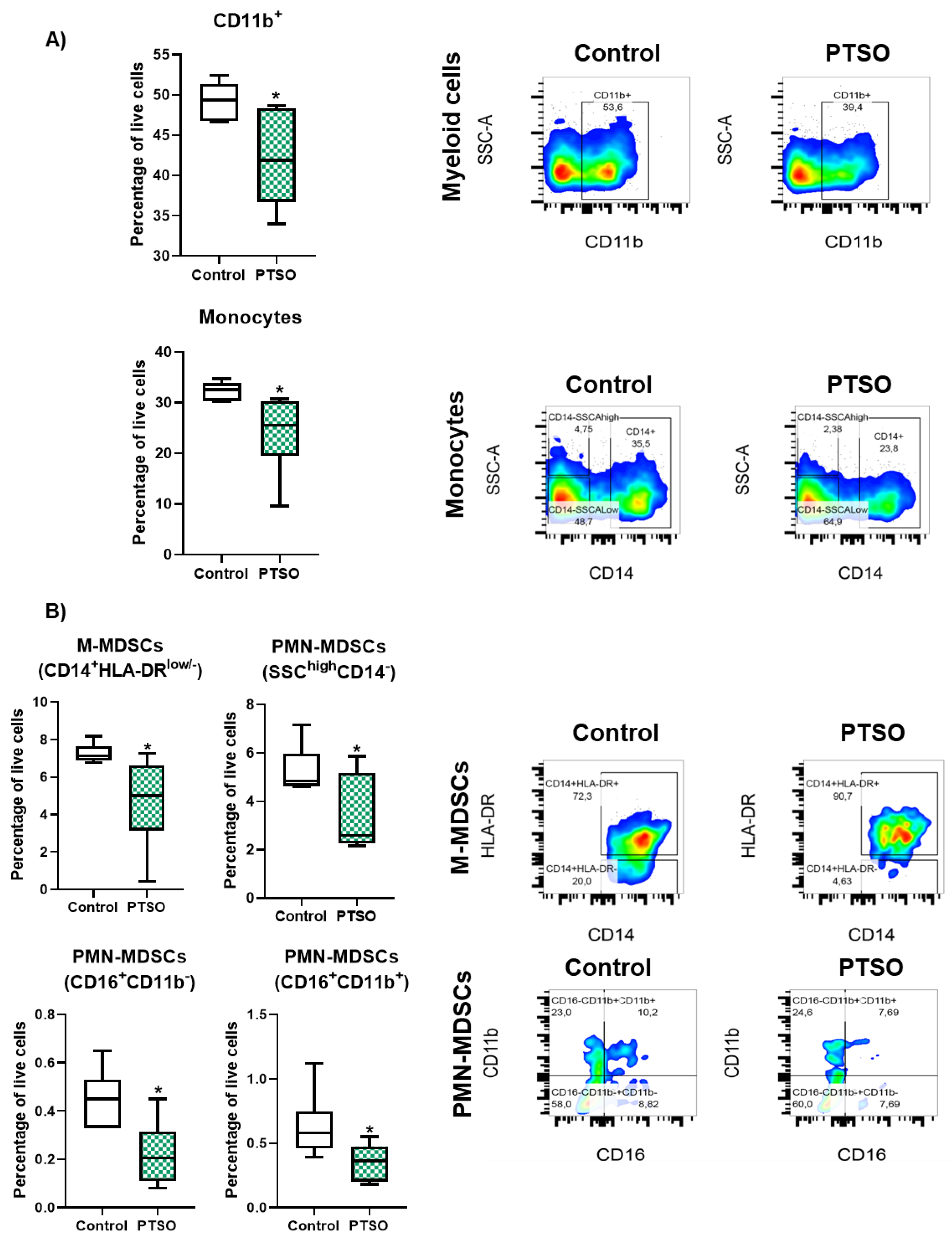

3.1. PTSO Reduces the Levels of Immunosuppressive Myeloid Populations In Vitro

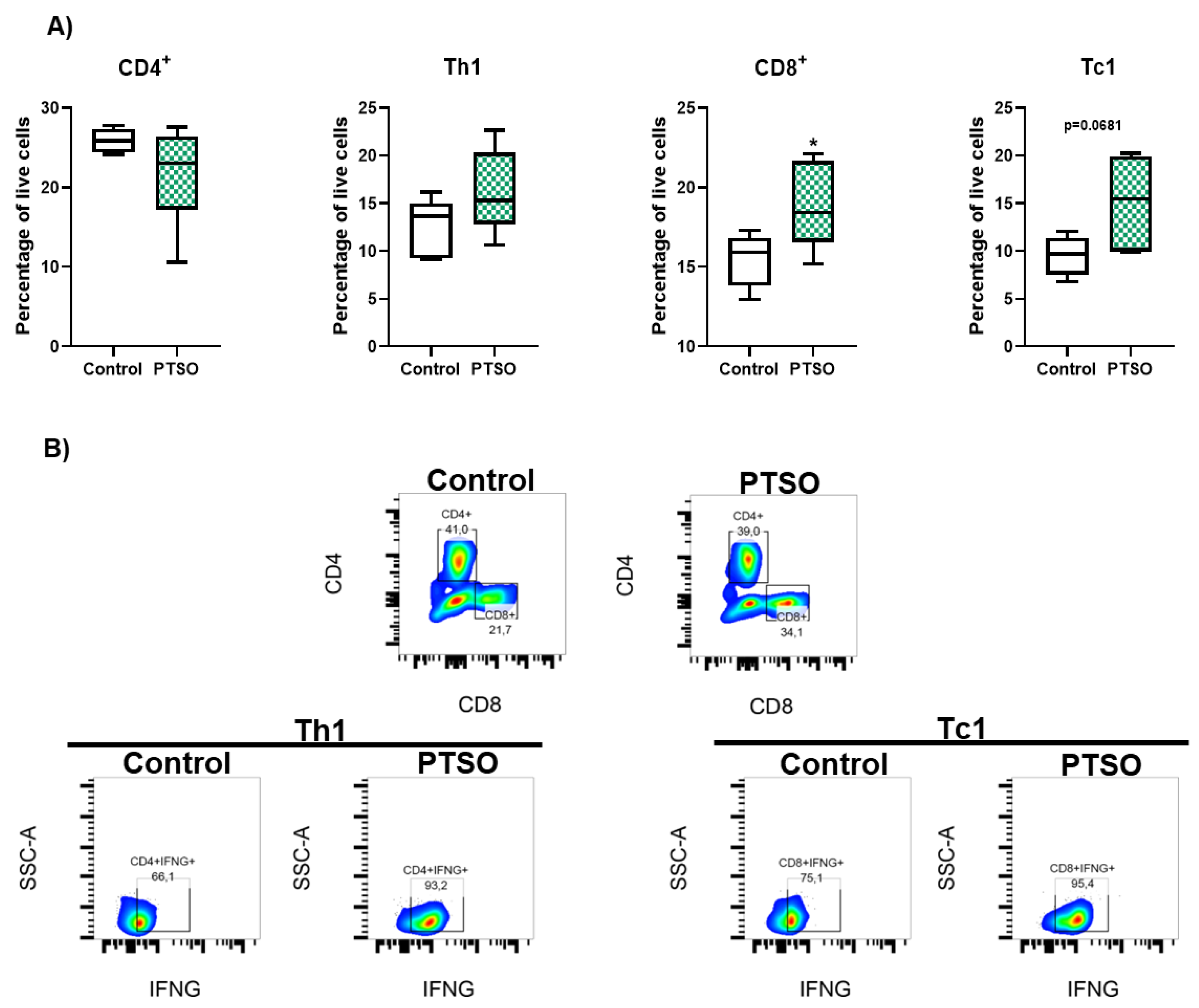

3.2. PTSO Promotes Cytotoxic T Cell Expansion In Vitro

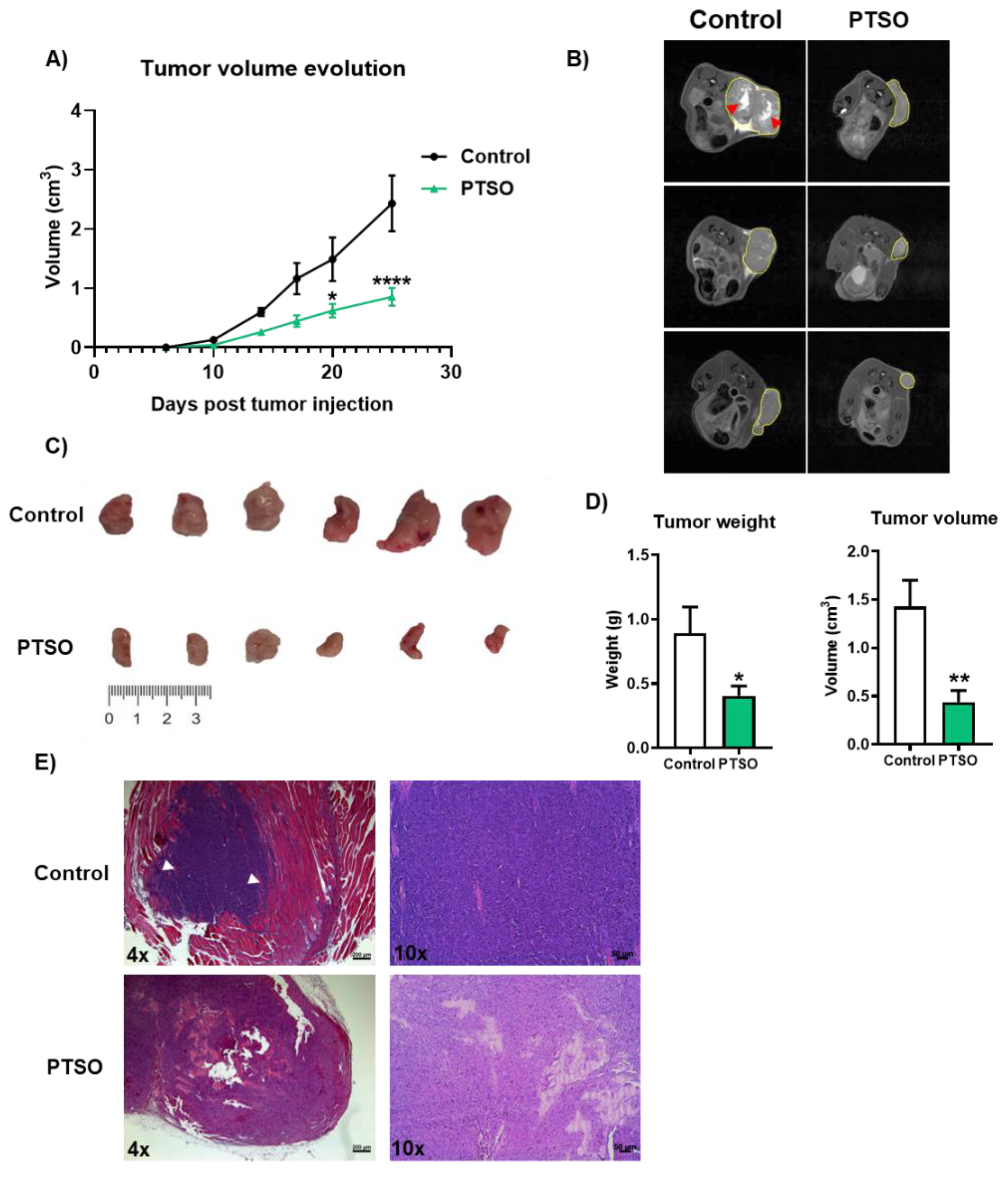

3.3. Immunomodulatory Activity of PTSO Impairs Tumor Growth in a CRC Xenograft Mouse Model

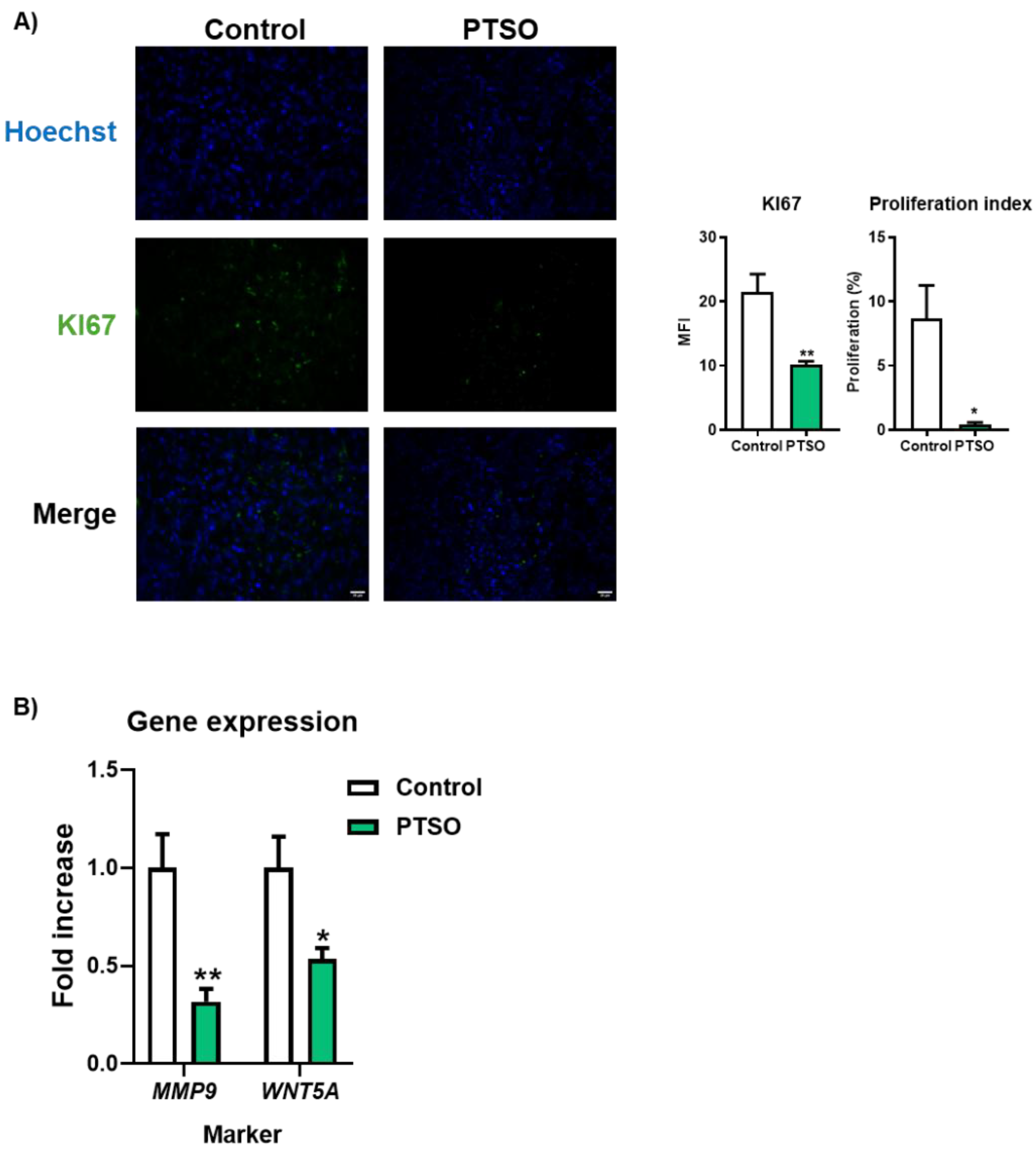

3.4. PTSO Modulates Tumor Cell Proliferation and Invasive Potential

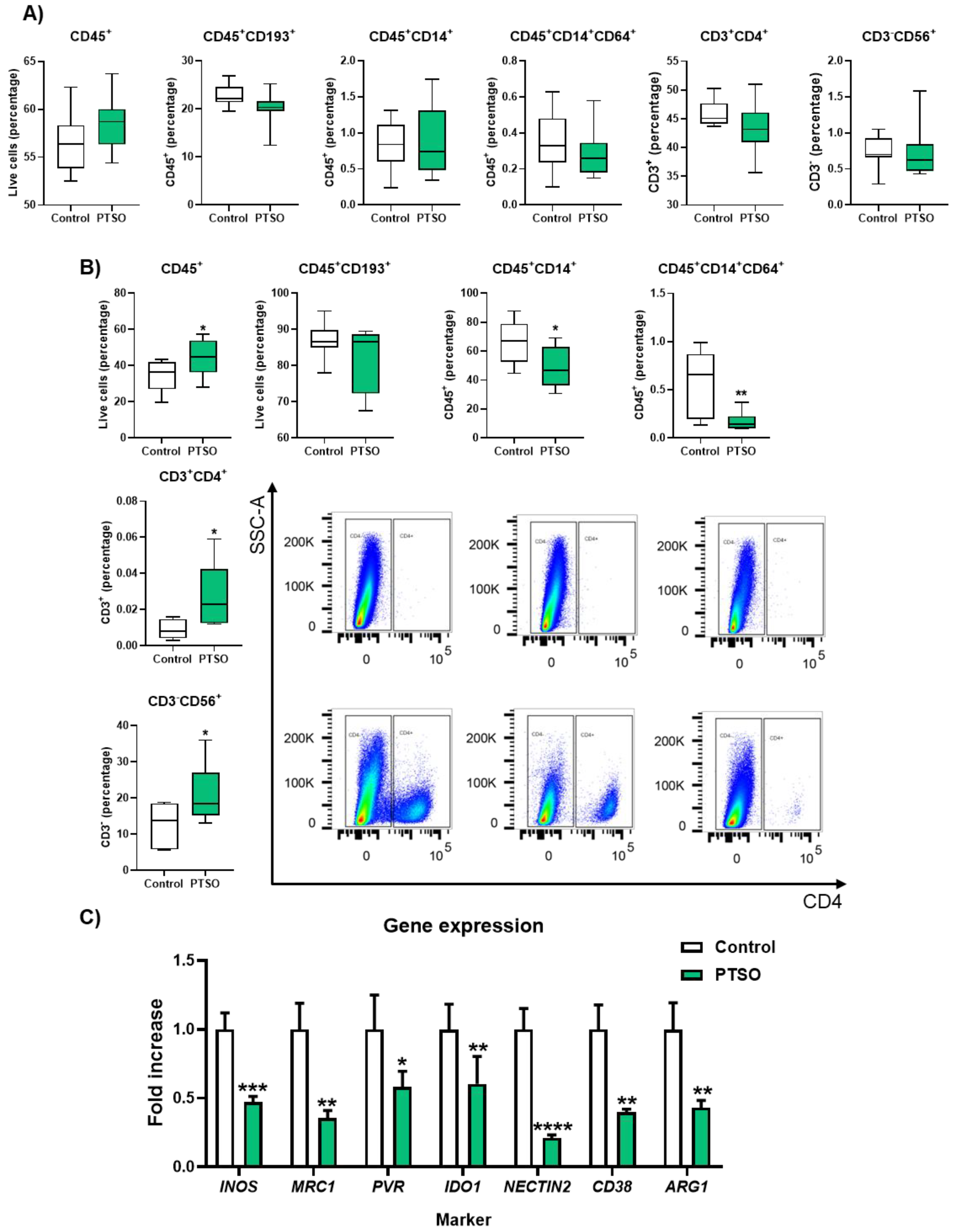

3.5. PTSO-Treated hPBMCs Enhance Tumor Immune Infiltration and Deplete the Intratumoral Myeloid Suppressor Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARG1 | Arginase-1 |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| CSCs | Cancer stem cells |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| hPBMCs | Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| ICIs | Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) |

| IFNG | Interferon gamma |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| MFI | Mean fluorescence intensity |

| M-MDSCs | Monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MSS | Microsatellite stability |

| NK | Natural Killer |

| NSG | NOD scid gamma |

| pMMR | Proficient mismatch repair |

| PMN-MDSCs | Polymorphonuclear Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| PTSO | Propyl Propane Thiosulfonate |

| Tc | T cytotoxic |

| Th | T helper |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| Tregs | Regulatory T cells |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Wagle, N.S.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin 2023, 73, 233-254. [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209-249. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Goding Sauer, A.; Fedewa, S.A.; Butterly, L.F.; Anderson, J.C.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 2020, 70, 145-164. [CrossRef]

- Fan, A.; Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Nie, Y.; Fan, D.; Zhao, X.; Lu, Y. Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: current achievements and future perspective. Int J Biol Sci 2021, 17, 3837-3849. [CrossRef]

- Barnestein, R.; Galland, L.; Kalfeist, L.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Ladoire, S.; Limagne, E. Immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment modulation by chemotherapies and targeted therapies to enhance immunotherapy effectiveness. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11, 2120676. [CrossRef]

- Gabrilovich, D.I.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; Bronte, V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol 2012, 12, 253-268. [CrossRef]

- Allegrezza, M.J.; Rutkowski, M.R.; Stephen, T.L.; Svoronos, N.; Perales-Puchalt, A.; Nguyen, J.M.; Payne, K.K.; Singhal, S.; Eruslanov, E.B.; Tchou, J.; et al. Trametinib Drives T-cell-Dependent Control of KRAS-Mutated Tumors by Inhibiting Pathological Myelopoiesis. Cancer Res 2016, 76, 6253-6265. [CrossRef]

- De, S.; Paul, S.; Manna, A.; Majumder, C.; Pal, K.; Casarcia, N.; Mondal, A.; Banerjee, S.; Nelson, V.K.; Ghosh, S.; et al. Phenolic Phytochemicals for Prevention and Treatment of Colorectal Cancer: A Critical Evaluation of In Vivo Studies. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Elattar, M.M.; Darwish, R.S.; Hammoda, H.M.; Dawood, H.M. An ethnopharmacological, phytochemical, and pharmacological overview of onion (Allium cepa L.). J Ethnopharmacol 2024, 324, 117779. [CrossRef]

- Guillamon, E.; Mut-Salud, N.; Rodriguez-Sojo, M.J.; Ruiz-Malagon, A.J.; Cuberos-Escobar, A.; Martinez-Ferez, A.; Rodriguez-Nogales, A.; Galvez, J.; Banos, A. In Vitro Antitumor and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Allium-Derived Compounds Propyl Propane Thiosulfonate (PTSO) and Propyl Propane Thiosulfinate (PTS). Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Myhill, L.J.; Andersen-Civil, A.I.S.; Thamsborg, S.M.; Blanchard, A.; Williams, A.R. Garlic-Derived Organosulfur Compounds Regulate Metabolic and Immune Pathways in Macrophages and Attenuate Intestinal Inflammation in Mice. Mol Nutr Food Res 2022, 66, e2101004. [CrossRef]

- Schafer, G.; Kaschula, C.H. The immunomodulation and anti-inflammatory effects of garlic organosulfur compounds in cancer chemoprevention. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2014, 14, 233-240. [CrossRef]

- Amani, M.; Shokati, E.; Entezami, K.; Khorrami, S.; Jazayeri, M.H.; Safari, E. The immunomodulatory effects of low molecular weight garlic protein in crosstalk between peripheral blood mononuclear cells and colon cancer cells. Process Biochemistry 2021, 108, 161-168. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, H.; Yang, Q.; Wang, B.; Ma, Q.; Chen, Y.; Xu, F.; Shi, X.; et al. Oral administration of garlic-derived nanoparticles improves cancer immunotherapy by inducing intestinal IFNgamma-producing gammadelta T cells. Nat Nanotechnol 2024, 19, 1569-1578. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.J.; Rao, Q.R.; Jiang, X.Q.; Ye, N.; Li, N.; Du, H.L.; Zhang, S.J.; Ye, H.Y.; Wu, W.S.; Zhao, M. Exploring the Immunomodulatory Properties of Red Onion (Allium cepa L.) Skin: Isolation, Structural Elucidation, and Bioactivity Study of Novel Onion Chalcones Targeting the A(2A) Adenosine Receptor. J Agric Food Chem 2023. [CrossRef]

- Falcón Piñeiro, A.; Garrido Garrido, D.; Baños Arjona, A. PTS and PTSO, two organosulfur compounds from onion by-products as a novel solution for plant disease and pest management. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Vezza, T.; Algieri, F.; Garrido-Mesa, J.; Utrilla, M.P.; Rodriguez-Cabezas, M.E.; Banos, A.; Guillamon, E.; Garcia, F.; Rodriguez-Nogales, A.; Galvez, J. The Immunomodulatory Properties of Propyl-Propane Thiosulfonate Contribute to its Intestinal Anti-Inflammatory Effect in Experimental Colitis. Mol Nutr Food Res 2019, 63, e1800653. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, G.; Hackenberg, M.; Catalina, P.; Boulaiz, H.; Grinan-Lison, C.; Garcia, M.A.; Peran, M.; Lopez-Ruiz, E.; Ramirez, A.; Morata-Tarifa, C.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell’s secretome promotes selective enrichment of cancer stem-like cells with specific cytogenetic profile. Cancer Lett 2018, 429, 78-88. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Mao, Z.; Wang, W.; Ma, J.; Tian, J.; Wang, S.; Yin, K. Netrin-1 Promotes the Immunosuppressive Activity of MDSCs in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 2023, 11, 600-613. [CrossRef]

- Waldman, A.D.; Fritz, J.M.; Lenardo, M.J. A guide to cancer immunotherapy: from T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 651-668. [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chang, J.; Chang, W.; Lv, Y.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Lin, Q.; Tang, W.; et al. The immune phenotypes and different immune escape mechanisms in colorectal cancer. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 968089. [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Ding, D.; Li, Y.; Lan, T.; Ryabtseva, S.; Huang, S.; Ren, J.; Huang, H.; Wei, B. HDACi combination therapy with IDO1i remodels the tumor microenvironment and boosts antitumor efficacy in colorectal cancer with microsatellite stability. J Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 753. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Escudero, M.; Arias-Gonzalez, N.; Martinez-Caceres, E. Regulatory cells and the effect of cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 26. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Chen, H.; Wong, C.C.; Peng, Y.; Gou, H.; Zhang, J.; Pan, Y.; Chen, D.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. ALKBH5 Drives Immune Suppression Via Targeting AXIN2 to Promote Colorectal Cancer and Is a Target for Boosting Immunotherapy. Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 445-462. [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Zhai, J.; Chen, H.; Wong, C.C.; Liang, C.; Ding, Y.; Huang, D.; Gou, H.; Chen, D.; Pan, Y.; et al. Targeting m(6)A reader YTHDF1 augments antitumour immunity and boosts anti-PD-1 efficacy in colorectal cancer. Gut 2023, 72, 1497-1509. [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Horlad, H.; Shiraishi, D.; Tsuboki, J.; Kudo, R.; Ikeda, T.; Nohara, T.; Takeya, M.; Komohara, Y. Onionin A, a sulfur-containing compound isolated from onions, impairs tumor development and lung metastasis by inhibiting the protumoral and immunosuppressive functions of myeloid cells. Mol Nutr Food Res 2016, 60, 2467-2480. [CrossRef]

- Limagne, E.; Euvrard, R.; Thibaudin, M.; Rebe, C.; Derangere, V.; Chevriaux, A.; Boidot, R.; Vegran, F.; Bonnefoy, N.; Vincent, J.; et al. Accumulation of MDSC and Th17 Cells in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Predicts the Efficacy of a FOLFOX-Bevacizumab Drug Treatment Regimen. Cancer Res 2016, 76, 5241-5252. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.K.; Sinha, P.; Clements, V.K.; Rodriguez, P.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells inhibit T-cell activation by depleting cystine and cysteine. Cancer Res 2010, 70, 68-77. [CrossRef]

- Tsukumo, S.I.; Yasutomo, K. Regulation of CD8(+) T Cells and Antitumor Immunity by Notch Signaling. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 101. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yin, K.; Tian, J.; Xia, X.; Ma, J.; Tang, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, S. Granulocytic Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Promote the Stemness of Colorectal Cancer Cells through Exosomal S100A9. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2019, 6, 1901278. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.D.; Lu, C.; Payne, D.; Paschall, A.V.; Klement, J.D.; Redd, P.S.; Ibrahim, M.L.; Yang, D.; Han, Q.; Liu, Z.; et al. Autocrine IL6-Mediated Activation of the STAT3-DNMT Axis Silences the TNFalpha-RIP1 Necroptosis Pathway to Sustain Survival and Accumulation of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Cancer Res 2020, 80, 3145-3156. [CrossRef]

- Karakasheva, T.A.; Waldron, T.J.; Eruslanov, E.; Kim, S.B.; Lee, J.S.; O’Brien, S.; Hicks, P.D.; Basu, D.; Singhal, S.; Malavasi, F.; et al. CD38-Expressing Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Promote Tumor Growth in a Murine Model of Esophageal Cancer. Cancer Res 2015, 75, 4074-4085. [CrossRef]

- Holmgaard, R.B.; Zamarin, D.; Li, Y.; Gasmi, B.; Munn, D.H.; Allison, J.P.; Merghoub, T.; Wolchok, J.D. Tumor-Expressed IDO Recruits and Activates MDSCs in a Treg-Dependent Manner. Cell Rep 2015, 13, 412-424. [CrossRef]

- Nikoo, S.; Bozorgmehr, M.; Namdar Ahmadabad, H.; Hassan, Z.M.; Moazzeni, S.M.; Pourpak, Z.; Ghazanfari, T. The 14kDa protein molecule isolated from garlic suppresses indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase metabolites in mononuclear cells in vitro. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008, 7, 203-208.

- Scodeller, P.; Simon-Gracia, L.; Kopanchuk, S.; Tobi, A.; Kilk, K.; Saalik, P.; Kurm, K.; Squadrito, M.L.; Kotamraju, V.R.; Rinken, A.; et al. Precision Targeting of Tumor Macrophages with a CD206 Binding Peptide. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 14655. [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Ikenaga, N.; Nakata, K.; Higashijima, N.; Zhong, P.; Kubo, A.; Wu, C.; Tsutsumi, C.; Shimada, Y.; Hayashi, M.; et al. Tumor-associated neutrophils upregulate Nectin2 expression, creating the immunosuppressive microenvironment in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2024, 43, 258. [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.J.; He, Y.S.; Guo, T.; Tao, J.; Wei, Z.Y.; Zhang, J.L.; Bao, C.; Chen, J.H. ADAR-mediated RNA editing regulates PVR immune checkpoint in colorectal cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2024, 695, 149373. [CrossRef]

- Domblides, C.; Crampton, S.; Liu, H.; Bartleson, J.M.; Nguyen, A.; Champagne, C.; Landy, E.E.; Spiker, L.; Proffitt, C.; Bhattarai, S.; et al. Human NLRC4 expression promotes cancer survival and associates with type I interferon signaling and immune infiltration. J Clin Invest 2024, 134. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Alves, N.; Dalmasso, G.; Nikitina, D.; Vaysse, A.; Ruez, R.; Ledoux, L.; Pedron, T.; Bergsten, E.; Boulard, O.; Autier, L.; et al. The colibactin-producing Escherichia coli alters the tumor microenvironment to immunosuppressive lipid overload facilitating colorectal cancer progression and chemoresistance. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2320291. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Qi, L.; Si, W.; Bo, Y.; Chen, X.; Ye, Z.; Fan, H.; Liu, B.; et al. Spatiotemporal single-cell analysis decodes cellular dynamics underlying different responses to immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 1268-1285 e1267. [CrossRef]

- Nersesian, S.; Schwartz, S.L.; Grantham, S.R.; MacLean, L.K.; Lee, S.N.; Pugh-Toole, M.; Boudreau, J.E. NK cell infiltration is associated with improved overall survival in solid cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Oncol 2021, 14, 100930. [CrossRef]

- Raskov, H.; Orhan, A.; Christensen, J.P.; Gogenur, I. Cytotoxic CD8(+) T cells in cancer and cancer immunotherapy. Br J Cancer 2021, 124, 359-367. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Mohammad Hassan, Z.; Mostafaie, A.; Zare Mehrjardi, N.; Ghazanfari, T. Purif ied Protein Fraction of Garlic Extract Modulates Cellular Immune Response against Breast Transplanted Tumors in BALB/c Mice Model. Cell J 2013, 15, 65-75.

- Park, S.Y.; Pylaeva, E.; Bhuria, V.; Gambardella, A.R.; Schiavoni, G.; Mougiakakos, D.; Kim, S.H.; Jablonska, J. Harnessing myeloid cells in cancer. Mol Cancer 2025, 24, 69. [CrossRef]

- Safarzadeh, E.; Orangi, M.; Mohammadi, H.; Babaie, F.; Baradaran, B. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: Important contributors to tumor progression and metastasis. J Cell Physiol 2018, 233, 3024-3036. [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadegan, M.R.; Bagheri, V.; Razavi, M.S.; Momtazi, A.A.; Sahebkar, A.; Gholamin, M. Isolation, identification, and characterization of cancer stem cells: A review. J Cell Physiol 2017, 232, 2008-2018. [CrossRef]

- Pothuraju, R.; Rachagani, S.; Krishn, S.R.; Chaudhary, S.; Nimmakayala, R.K.; Siddiqui, J.A.; Ganguly, K.; Lakshmanan, I.; Cox, J.L.; Mallya, K.; et al. Molecular implications of MUC5AC-CD44 axis in colorectal cancer progression and chemoresistance. Mol Cancer 2020, 19, 37. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Xie, M.; He, D.; Pan, Q.; Zhang, P.; Hua, D.; Wang, T.; Jin, L.; et al. TrpC5 regulates differentiation through the Ca2+/Wnt5a signalling pathway in colorectal cancer. Clin Sci (Lond) 2017, 131, 227-237. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Wang, J.; Dasari, S.; Pepin, D.; Nephew, K.P.; Zamarin, D.; Mitra, A.K. Cancer associated fibroblasts serve as an ovarian cancer stem cell niche through noncanonical Wnt5a signaling. NPJ Precis Oncol 2024, 8, 7. [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Wu, L.; Sun, G.; Shi, X.; Cao, H.; Tang, W. WNT5a in Colorectal Cancer: Research Progress and Challenges. Cancer Manag Res 2021, 13, 2483-2498. [CrossRef]

- Kusmartsev, S. Metastasis-promoting functions of myeloid cells. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2025, 44, 61. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Cai, X.; Shen, T.; Pan, D.; Liang, R.; Ding, R.; Hu, R.; Dong, J.; et al. Single-cell sequencing reveals the immune microenvironment landscape related to anti-PD-1 resistance in metastatic colorectal cancer with high microsatellite instability. BMC Med 2023, 21, 161. [CrossRef]

- Rogala, J.; Sieminska, I.; Baran, J.; Rubinkiewicz, M.; Zybaczynska, J.; Szczepanik, A.M.; Pach, R. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells May Predict the Occurrence of Postoperative Complications in Colorectal Cancer Patients-a Pilot Study. J Gastrointest Surg 2022, 26, 2354-2357. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhang, B.; Li, B.; Wu, H.; Jiang, M. Cold and hot tumors: from molecular mechanisms to targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 274. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Nicolas, M.; Pastor-Belda, M.; Campillo, N.; Rodriguez-Sojo, M.J.; Ruiz-Malagon, A.J.; Hidalgo-Garcia, L.; Abad, P.; de la Torre, J.M.; Guillamon, E.; Banos, A.; et al. Analytical Platform for the Study of Metabolic Pathway of Propyl Propane Thiosulfonate (PTSO) from Allium spp. Foods 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Fan, Y.; Huang, L.; Cai, X. Understanding the cellular and molecular heterogeneity in colorectal cancer through the use of single-cell RNA sequencing. Transl Oncol 2025, 55, 102374. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).