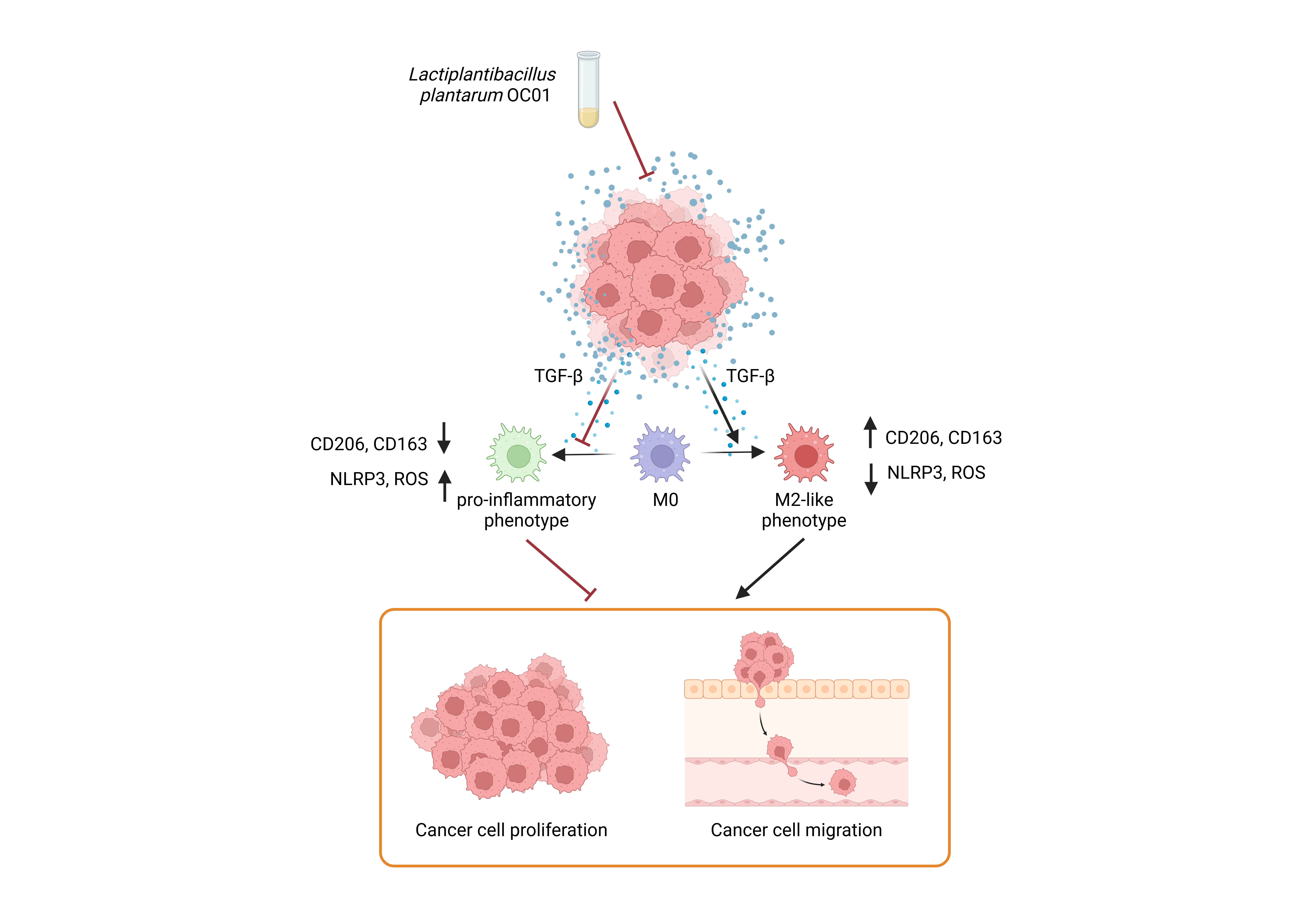

Graphical abstract. Schematic representation of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 metabolites reshaping the CRC tumor microenvironment by decreasing TGF-β levels, a key inducer of M2 macrophages. This results in macrophage differentiation into a pro-inflammatory phenotype, which counteracts CRC cell proliferation and migration (Created with BioRender).

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) accounts for more than 900,000 deaths annually, making it the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [

1]. Its rising incidence has been linked to genetic and epigenetic factors, as well as dietary habits and sedentary lifestyles, particularly in developing countries [

1]. In addition to these factors, many studied have demonstrated the significant role of the gut microbiota in CRC development and treatment outcomes [

2,

3]. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota contributes to CRC through various mechanisms, including the secretion of microbial toxins, altered metabolites production, hormonal dysregulation, chronic immune activation, and persistent inflammation [4-6].

Given its crucial involvement in CRC pathogenesis, the gut microbiota is now recognized as a key component of the tumor microenvironment (TME) [

7,

8], which also includes stromal cells, immune cells, and non-cellular component such as extracellular matrix (ECM), cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors that support tumor growth [

9]. Among immune cells, intestinal macrophages are the most abundant tumor-infiltrating immune cells in CRC tissues. These cells regulate the innate immune response, maintain tissue homeostasis, and modulate inflammation [

10].

Within the TME, macrophages differentiate into tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), exhibiting phenotypic plasticity [

11]. TAMs can polarize into either an M1 or M2 phenotype, driven by signals released by cancer cells [

12]. M1-like phenotype exhibits pro-inflammatory, immunostimulatory, and anti-tumorigenic properties through the release of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. In contrast, the M2-like phenotype is characterized by immunosuppressive and pro-tumorigenic properties due to the secretion of IL-10, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, and proteolytic enzymes like MMP-9 that contribute to ECM remodeling and facilitate cancer invasion and metastasis [

11,

13].

The polarization toward the M1-like phenotype is induced by microbial stimuli such as exogenous LPS and other pro-inflammatory signals [

14,

15], whereas the M2-like phenotype can be divided into four distinct subtypes, namely M2a, M2b, M2c, and M2d, depending on the stimuli involved. M2a is induced by IL-4 or IL-13, M2b by immune complexes in combination with IL-1β or LPS, M2c by IL-10 and TGF-β, and M2d by TLR or IL-6 signaling [

16]. These subtypes can be identified by specific surface markers, with M1 macrophage expressing CD80 and CD86 on the membrane and M2c macrophages exhibiting elevated CD206 and CD163 expression [

17].

M1 and M2 macrophages differ significantly in their immunological roles. M1 macrophages are activated through the NLRP3 inflammasome [18-20], which may be triggered by the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

21]). This activation leads to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 [

22]. Furthermore, reactive oxygen species (ROS) can activate the NK-kB signaling pathway, enhancing the transcription of additional pro-inflammatory cytokines, playing a crucial role in inducing inflammatory responses and tumor cell eradication [

17]. In contrast, M2 macrophages are characterized by the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines, having an immunosuppressive role and promoting tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis.

During cancer progression, M1 and M2 macrophage phenotypes are not fixed but change over time. In the early stages of tumor development, M1 macrophages predominate and actively work to destroy cancer cells. As the tumor progresses, macrophages gradually adopt the M2 phenotype, which supports immune suppression and tumor growth [

23]. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota plays a key role in this process by activating macrophages towards M2-like phenotype, creating an immunosuppressive TME that facilitates tumor progression and metastasis [

24].

Probiotics represent a promising new approach for managing CRC. By competing with pathogenic bacteria for space and nutrients, and producing antibacterial substances, probiotics help restore a balanced gut microbiota (eubiosis). This balance exerts anti-tumor activity by counteracting carcinogenic molecules, promoting apoptosis and cellular differentiation, and regulating immune and inflammatory responses [

25,

26].

The objective of our study is to integrate our knowledge on the beneficial effects of probiotic metabolites in CRC management, focusing on the changes they induce in the TME. We hypothesize that metabolites produced by the gut microbiota may have the potential to disrupt the crosstalk between cancer and TAMs, whose polarization into M2-like phenotype contributes to cancer progression.

In our previous research, we investigated the effects of the supernatant from the probiotic strain

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 on oncogenic pathways, which are commonly targeted in cancer treatment. Our findings revealed that metabolites derived from

L. plantarum had a negative impact on the activation of ERK and S6, key pathways involved in cancer development. Furthermore, these probiotic-derived metabolites were able to counteract IL-6-induced cell proliferation and migration, exerting a beneficial effect on CRC cells [

27].

Here, we demonstrate that Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 metabolites modulate the TME by influencing the crosstalk between cancer cells and macrophage. Conditioning medium (CM) from probiotic-treated CRC cells induced in macrophage the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and increased ROS production, driving a shift towards a more pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotype. This shift was reflected in the decreased levels of TGF-β, a key cytokine involved in M2 polarization, in probiotic-treated cancer cells, alongside the maintained or slight increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α. The more inflammatory phenotype was further confirmed by a reduction in the expression of M2-associated markers CD206 and CD163 in PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages exposed to CM from probiotic-treated CRC cells, compared to those exposed to CM from untreated cells. In co-culture experiments, macrophages exposed to CM from probiotic-treated cancer cells showed a decrease in cancer cell proliferation and migration, whereas those exposed to CM from untreated cells promoted these processes, highlighting that the shift towards a more pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotype attenuates the tumor-promoting effect on cancer cells. These findings suggest that probiotics alter the TME by modulating macrophage behavior and inflammatory cytokine profiles, ultimately influencing cancer cell progression.

By elucidating the impact of microbiota metabolites on TAMs and their role in modulating the pro-tumoral phenotype, our findings provide the pre-clinical rationale for probiotic therapeutic application, targeting both the gut microbiota and immune components of the TME. The restoration of a healthy microbiota through probiotics is expected to improve the overall health status of CRC patients, and potentially mitigate the risks of secondary metastasis and relapse.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Treatment

The human THP-1 monocyte cell line (TIB-202™), isolated from the peripheral blood of an acute monocytic leukemia patient, along with the human CRC cell lines HCT116 (CCL-247™) and HT29 (CCL-227™), each characterized by distinct genetic backgrounds and tumor site origins, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). All cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (R8758; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, ECS0180L; Euroclone, Milan, Italy), 1% glutamine (G7513; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (PES, P0781; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The cell culture were maintained under standard culture conditions (37 °C, 95% air, 5% CO₂).

THP-1 monocyte cell line was treated with 20 ng/ml Phorbol-12-Myristate-13-Acetate (PMA, P8139; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) dissolved in DMSO to induce macrophage differentiation.

2.2. Probiotic Formulation

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 (NCIMB 30624), sourced from the Probiotical SpA collection, was utilized as previously described [

27]. Briefly, the probiotic strain was stored at -80°C in 20% glycerol, with over 90% cell viability upon thawing. Before use, microorganisms were cultured under anaerobic conditions using CO₂-generating kits (Anaerocult A; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at 37 °C overnight in de Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) broth containing 0.05% cysteine hydrochloride and then sub-cultured to mid-log phase. Live bacterial counts were determined using the BD Cell Viability Kit (BD Biosciences, Milan, Italy), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For stimulation experiments, eukaryotic cells were exposed to the cell-free supernatant of OC01, which contained all catabolic and anabolic products released by 10 billion viable probiotic cells after overnight overgrowth. This supernatant was filtered through a 0.2 μm syringe filter to remove viable cells.

CRC cultures were supplemented with 10 μl of OC01 cell-free supernatant per 1 ml of final culture media volume.

2.3. Collection of the Colorectal Cancer Cell Conditioning Media (CRC Cell CM)

CRC cells (HCT116 and HT29) were cultured in 75 cm² flasks and treated with or without

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 supernatant for 48 hours, and then the CM was collected. CRC cell CM was centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 minutes to remove cell debris, diluted 50:50 (CRC cell CM : RPMI-1640), and then stored at -20 °C until use, as previously described [

28], with adjustments for CRC lines and dilution ratio.

2.4. Antibodies

The following primary antibodies (at the dilution indicated) were used for either immunofluorescence or Western blotting: mouse anti-CD68 (1:500, cod. 14-0688-80; Life Technologies, Paisley, UK); rabbit anti-NLRP3 (1:500, cod. MA5-32255; Life Technologies, Paisley, UK); rabbit anti-CD206 (1:500, cod. MA5-32498; Life Technologies, Paisley, UK); mouse anti-CD163 (1:500, cod. ab156769; abcam, Cambridge, UK); mouse anti-p21 (1:100, cod. B1313; Santa Cruz, Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA); rabbit anti-Ki67 (1:100, cod. HPA001164; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); rabbit anti-GAPDH (1:1000, cod. G9545; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); mouse anti-β-actin (1:2000, cod. A5441; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.5. Western Blotting Analysis

THP-1 cells were seeded in p35 Petri dishes at a density of 50,000 cells/cm² and treated as indicated. Cell homogenates were prepared by freeze-thawing and ultrasonication in RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors. Equal protein amounts (30 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C, followed by incubation with secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature, as detailed in [

29]. Bands were detected using Enhanced Chemiluminescence reagents (cod. NEL105001EA; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and analyzed using a VersaDOC Imaging System (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) with Quantity One software (v.4.5). Band intensity was quantified by densitometry using Quantity One software (v.4.5), and normalization was performed by re-probing the membranes with GAPDH or β-actin. Data were reproduced at least three times.

2.6. Immunofluorescence Assay

Cells were seeded onto sterile coverslips at a density of 30,000 (cancer cells) - 50,000 (THP-1) cells/cm

2 and treated as reported. At the end of the experiment, the coverslips were fixed in ice-cold methanol (cancer cells) or 4% paraformaldehyde (THP-1) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with specific primary antibodies as previously described [

29]. The following day, coverslips were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies (diluted in 0.1% Triton-PBS + 10% FBS), either AlexaFluor488-conjugated goat-anti rabbit IgG (1:000, cod. A32731, Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) or AlexaFluor555-conjugated goat-anti mouse IgG (1:1000, cod. A32727, Invitrogen, Paisley, UK), as appropriate. Nuclei were stained with UV fluorescent dye DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). Coverslips were mounted onto glass using SlowFade reagent (cod. S36936; Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) and imaged with a fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems DMI6000; Wetzlar, Germany).

2.7. Phagocytosis Study

THP-1 cells were plated onto sterile coverslips at a density of 50,000 cells/cm² and treated as described. To evaluate phagocytic activity, cells were first incubated with 100 nM LysoTracker™ Red probe (cod. L7528, Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) at 37 °C for 10 minutes, followed by incubation with 25 µg/ml of 30 nm carboxy-functionalized nanoparticles (COOH-NPs), emitting green fluorescence (cod. L5155, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), at 37 °C for 10 minutes [

30]. Coverslips were washed, mounted, and immediately imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems DMI6000, Wetzlar, Germany).

2.8. Anion Superoxide Production by MitoSOX™ Fluorescence Assay

THP-1 cells were seeded onto coverslips at a density of 50,000 cells/cm

2 and treated as described. Mitochondrial anion superoxide was detected in living cells using 5 μM MitoSOX™ Red (cod. M36008; Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) as previously described [

31]. Coverslips were washed three times with PBS, mounted on glass slides, and images were immediately acquired using a fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems DMI6000, Wetzlar, Germany).

2.9. RNA Isolation and Quantitative PCR

HCT116 and HT29 cells were plated in p60 Petri dishes at a density of 50,000 cells/cm² and treated as described. The total RNA was extracted from the cells using TRIzol reagent (cod. T9424, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The mRNA was then reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (cod. K1622, Thermo-Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The cDNA was then amplified by PCR in the presence of recombinant Taq DNA polymerase (cod. 10342-020, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) and primers designed to anneal to the 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs). The PCR products ware analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

The sequences of the primers used were as follows (

Table 1):

2.10. Macrophages and Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines Co-Culture System Assay

To partially recreate the in vivo interaction between cancer and TAMs, a non-contact co-culture system (Transwell® Permeable Supports, Polycarbonate Membrane, 12 mm Insert, 0.4 μm pore size; cod. 3413, Corning Incorporated Costar, NY, USA) was used to assess the proliferative capacity of cancer cells exposed to the presence of macrophage. THP-1 cells were plated at a density of 30,000 cells/cm² within the insert, differentiated into macrophages as reported, and subsequently transferred to a 24-well plate pre-seeded with CRC cells on coverslips. After 24 hours of co-culture, the coverslips with cancer cells were washed with PBS, fixed with ice-cold methanol, and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. The cells were then incubated with primary antibodies and processed for immunofluorescence staining as described above.

To assess the migration capability of cancer cells in co-culture with THP-1-differentiated macrophages, THP-1 cells were seeded into 24-well plate at a density of 50,000 cells/cm² and differentiated into macrophages as described. Cancer cells were seeded in p35 Petri dishes at a density of 40,000 cells/cm² and cultured until reaching 80% confluence. After 48 hours of culture, the cancer cells were trypsinized, collected, and counted. An aliquot of 50,000 cells per experimental condition was resuspended in serum-free medium and plated into uncoated inserts (Transwell® Permeable Supports, Polycarbonate Membrane; 6.5 mm Insert; 8.0 μm pore size Polycarbonate Membrane; cod. 3422, Corning Incorporated Costar, NY, USA). Each insert was placed onto THP-1-differentiated macrophages in a 24-well plate containing complete RPMI, and the plate was placed in the incubator. After 24 hours of incubation, a fraction of each cell population had migrated through the porous membrane to the underside of the inserts. The migrated cells were washed in PBS, fixed in methanol for 30 minutes, washed again in PBS, and then stained for 1 hour with eosin-hematoxylin solution (cod. 05-M06002; Bio-Optica, Milan, Italy). The inserts were washed in PBS, let dry for at least 1 day, then cut and mounted onto slides using SlowFade reagent (cod. S36936; Life Technologies, Paisley, UK). Photographs were taken from random fields using Axioscan 7 microscope (magnification 20X; ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany). The amount of migrated cells (mirrored by the staining intensity) was quantified using ImageJ software. Data are expressed as the average number of migrated cells from different fields per each condition.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

All data refer to at least three separate experiments. Data in histograms are shown as average ± S.D. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. Bonferroni's multiple comparison test after one-way ANOVA analysis (unpaired, two-tailed) and t student test were employed. Significance was considered as follow: ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗p < 0.05.

3. Results

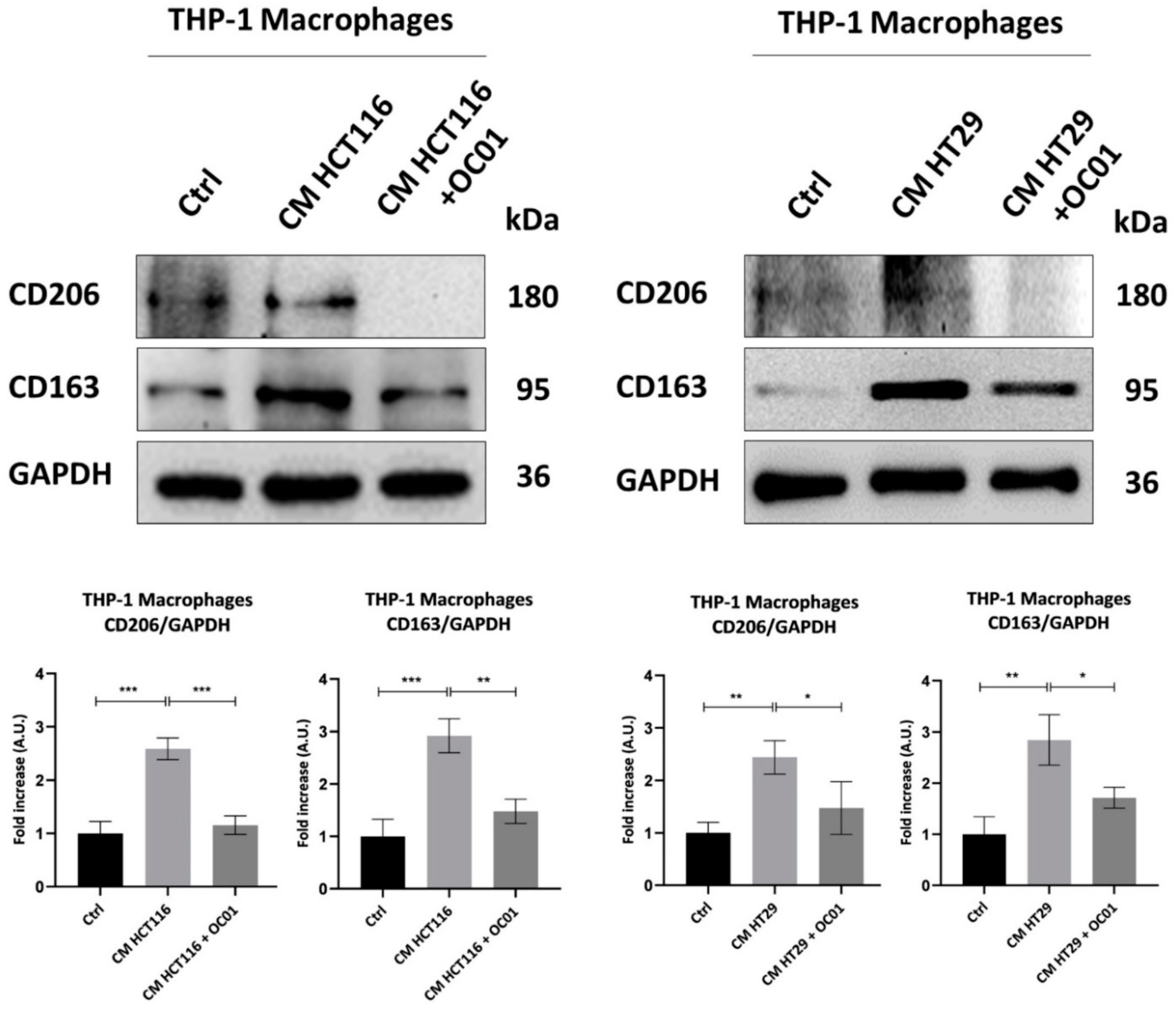

3.1. Differentiation of THP-1 into Macrophage-like Phenotype

The human monocyte cell line THP-1, commonly used for studies on macrophage differentiation, was exposed or not to 20 ng/ml of PMA to stimulate differentiation into macrophages (

Figure 1A). Following 48 hours of incubation with PMA and a subsequent 24-hour recovery in normal media, treated cells exhibited increased adherence to the culture plate, a key indicator of macrophage differentiation, along with a stellate and polygonal morphology and extended pseudopodia. In contrast, control cells retained a rounded shape and remained in suspension (

Figure 1B). This phenotypic transition was confirmed by monitoring the expression of the pan-macrophage or M0-like phenotype marker CD68 through Western blotting and immunofluorescence. The significant increased expression of CD68 in PMA-treated cells confirmed the activation of THP-1 monocytes into M0-like phenotype macrophages (

Figure 1C-D).

CD68, a transmembrane glycoprotein primarily localized in lysosomes, plays a crucial role in the internalization and degradation of extracellular particles, facilitating phagocytosis. Its upregulation is associated with enhanced macrophage activity [

32]. To assess the phagocytic capacity of M0-macrophages, cells were incubated with fluorescence-tagged nanoparticles (NPs), and their uptake into lysosomes was visualized using a red LysoTracker™ probe. Co-localization of NPs and lysosomes (yellow signal) indicated successful phagocytosis of NPs by macrophages. PMA-treated cells showed increased co-localization, suggesting enhanced phagocytic activity, whereas in untreated cells, NP uptake into lysosomes was completely absent, confirming the lack of phagocytic function in the monocyte cells (

Figure 1E).

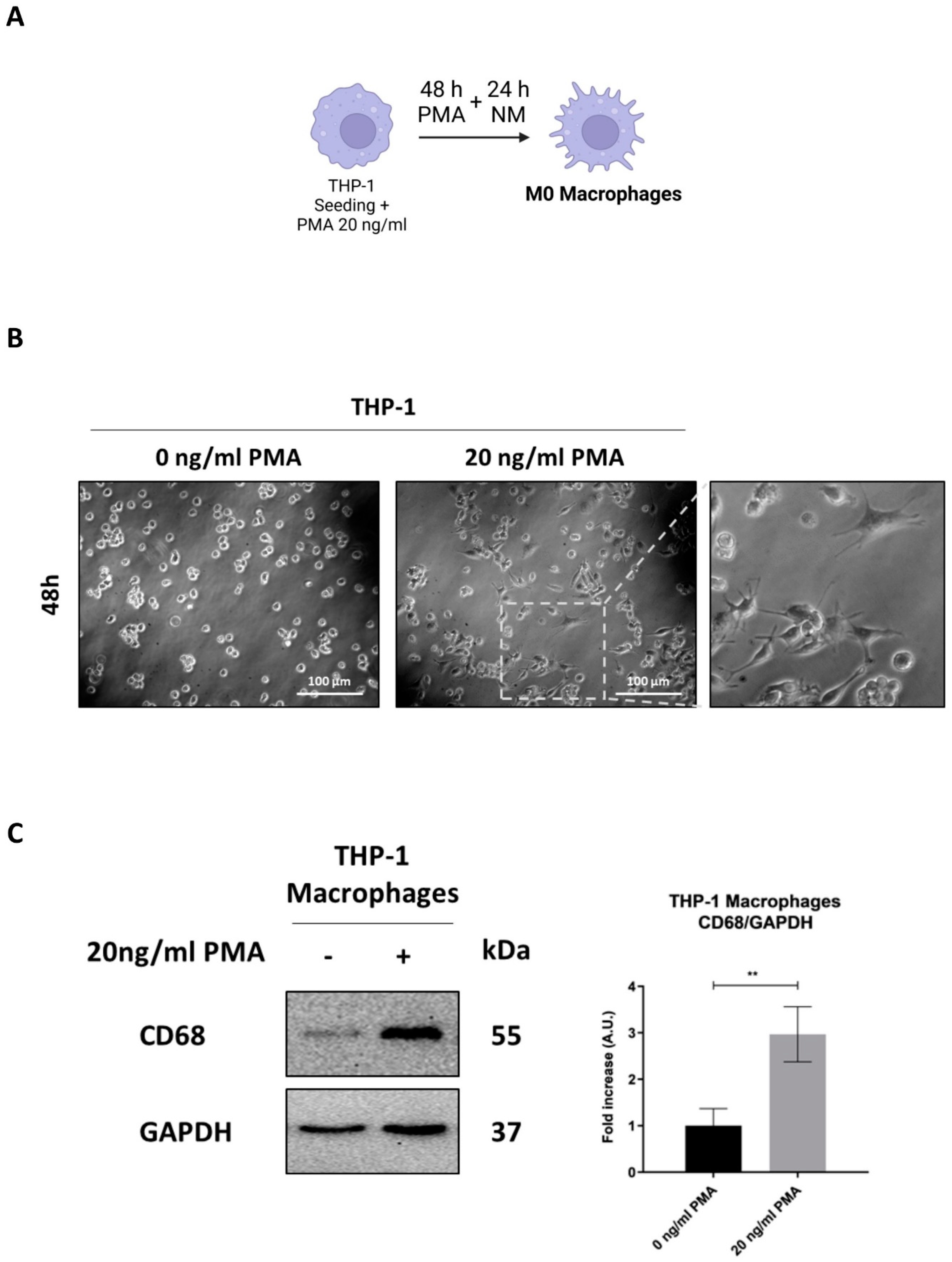

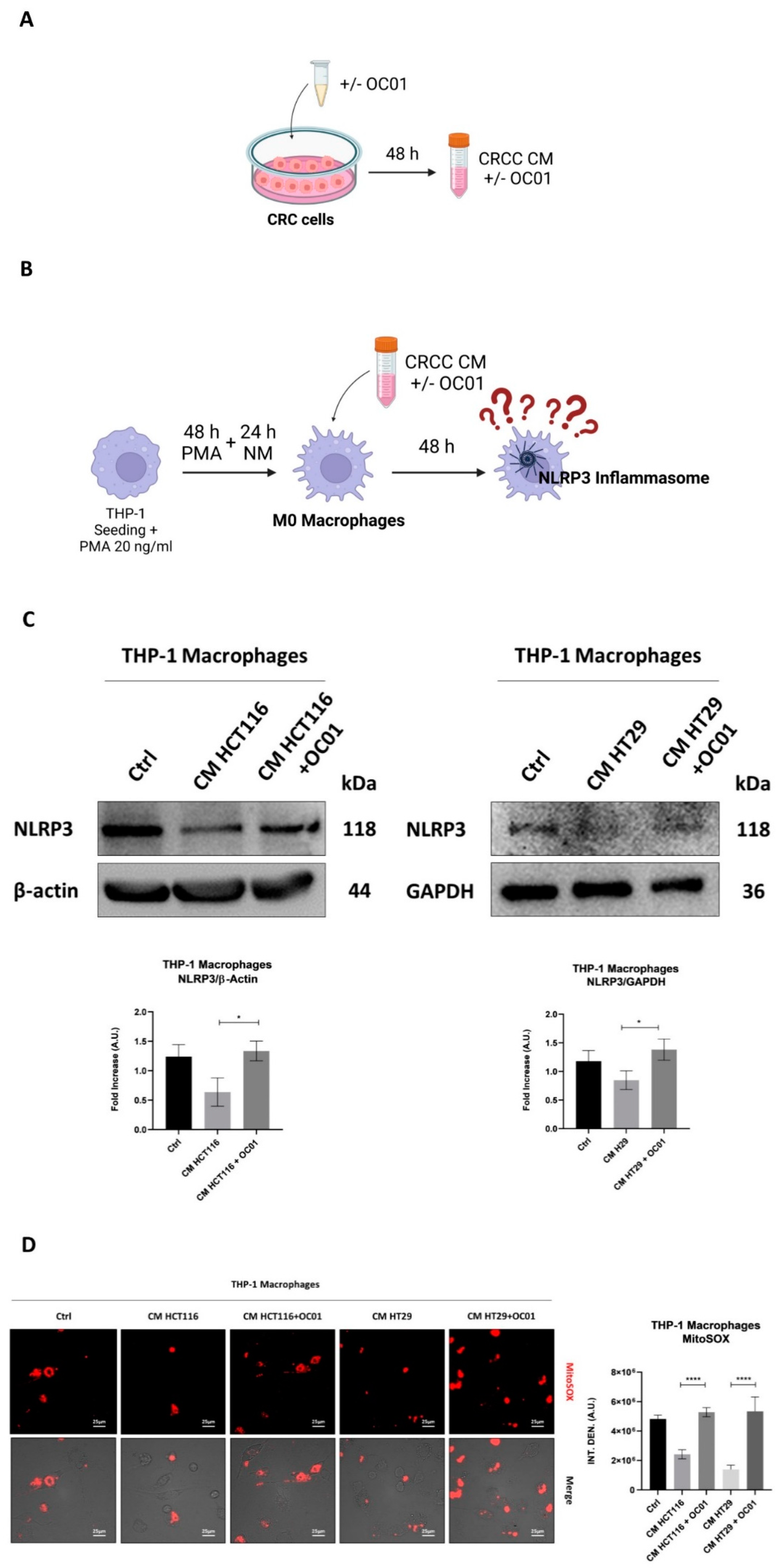

3.2. Conditioning Medium from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01-Treated Colorectal Cancer Cells Promotes Macrophage Inflammatory Phenotypes via NLRP3 Activation

Macrophages within the TME are strongly influenced by cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors, particularly secreted by cancer cells, driving their polarization into either a classically activated M1-like phenotype or an alternatively activated M2-like phenotypes. These TAMs play a critical role in the progression and metastasis of CRC [

33].

Given the pivotal role of TAMs in mediating the inflammatory response within the TME, we investigated inflammasome activation, focusing on NLRP3 as the central component in inflammasome-driven inflammation [

34]. M1 macrophages, associated with a pro-inflammatory and anti-tumor phenotype, typically exhibit higher levels of NLRP3 activity, while M2 macrophages are characterized by reduced NLRP3 activity, contributing to their anti-inflammatory profile and tumor-promoting effects [

19]. Notably, mitochondrial ROS have been identified as an inducer of NLRP3 activation, linking oxidative stress to inflammasome activation and the inflammatory response [

21].

To investigate the effect of CRC cells secretome on NLRP3 activation in macrophages, differentiated M0 macrophages were exposed to the CM from two CRC cells, HT29 and HCT116, which have different genetic backgrounds. The cancer cells were pre-treated for 48 hours with or without

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 supernatant (

Figure 2A-B) to determine whether this treatment influence the inflammatory status of macrophages.

Our results showed that macrophages differentiated with CM from HCT116 and HT29 cells pre-treated with

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 metabolites exhibited elevated NLRP3 expression and increased ROS production. In contrast, macrophages differentiated with CM from untreated cancer cells showed reduced NLRP3 expression and minimal ROS production (

Figure 2C-D). These findings suggest that macrophages exposed to CM from treated cancer cells may adopt a more inflammatory phenotype, potentially indicative of an M1-like profile. Conversely, macrophages exposed to CM from untreated cancer cells appear to exhibit a less inflammatory status, potentially aligning with an M2-like profile.

3.3. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 Metabolites Reduce the Expression of TGF-β in Colorectal Cancer Cells

To investigate the mechanism by which Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 supernatant modulates macrophage inflammatory status, we analyzed the cytokine profile of HCT116 and HT29 cells. We specifically analyzed key cytokines such as IL-8, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-18, IL-6, TNF-α, and TGF-β, which are known to play pivotal role in shaping the TME. These cytokines can direct macrophage activation toward anti-inflammatory, pro-tumoral phenotype, or pro-inflammatory, anti-tumoral phenotype phenotype, thus influencing the overall immune landscape within the tumor.

Cancer cells significantly contribute to an immune-suppressive, pro-tumoral environment, particularly through the secretion of cytokines like IL-10, TGF-β, and colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1). These molecules help reprogram macrophages to adopt an M2-like phenotype, promoting tumor progression by suppressing immune surveillance and enhancing tissue remodeling [

35,

38]. In contrast, cytokines, such as TNF-α, are generally associated with a pro-inflammatory, tumor-suppressive macrophage phenotype [

39], which can enhance the ability of immune system to fight against the tumor.

Our results demonstrated that treatment with OC01 cell-free supernatant led to a marked reduction in TGF-β expression, particularly in HT29 cells. Additionally, a slight increase in IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α was observed in both HCT116 and HT29 cells (

Figure 3).

Our results suggest that metabolites from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 may alter the cytokine profile of cancer cells, creating an environment that promotes a more pro-inflammatory macrophage state, potentially limiting tumor progression.

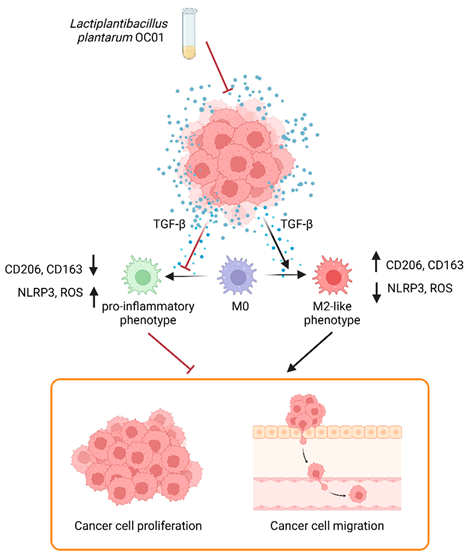

3.4. Conditioning Medium from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01-Treated Colorectal Cancer Cells Reduces the Polarization of Macrophages into the M2-like Phenotype

To further investigate whether the observed changes in inflammasome activation in macrophages exposed to CM from cancer cells pre-treated with

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 supernatant were linked to a shift in macrophage phenotype, we assessed the expression of the M2 markers CD206 and CD163, known to be associated with a less inflammatory state and pro-tumorigenic activity [

40].

Our results showed that CM from CRC cells supplemented with OC01 cell-free supernatant significantly reduced CD206 and CD163 expression, thereby limiting the differentiation of M0 macrophages into an M2-like phenotype. In contrast, macrophages exposed to CM from untreated CRC cells displayed increased expression of these markers, indicative of differentiation into anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, consistent with reduced inflammasome activation. Conversely, the reduction in CD206 and CD163 expression, combined with increased NLRP3 expression and ROS production in macrophages treated with CM from probiotic-supplemented CRC cells, suggests a shift toward a pro-inflammatory macrophage state.

Figure 4.

OC01 cell-free supernatant in the CRC cells CM limits the differentiation into M2 macrophages. HCT116 and HT29 cells were plated and treated or not with 10 µl of OC01 cell-free supernatant for 48 hours. The treatment was renewed every 24 hours. At the end of the treatment period, the CM was collected and used to treat the differentiated M0 macrophages for 48 hours. Cell homogenates were analyzed by Western blotting to assess the expression of M2 macrophages markers CD206 and CD163. The filter was re-probed with GAPDH as a loading control. The blot is representative of three experiments with reproducible results. Densitometric analysis, including standard deviation, is provided (significance was considered as follow: ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗p<0.05).

Figure 4.

OC01 cell-free supernatant in the CRC cells CM limits the differentiation into M2 macrophages. HCT116 and HT29 cells were plated and treated or not with 10 µl of OC01 cell-free supernatant for 48 hours. The treatment was renewed every 24 hours. At the end of the treatment period, the CM was collected and used to treat the differentiated M0 macrophages for 48 hours. Cell homogenates were analyzed by Western blotting to assess the expression of M2 macrophages markers CD206 and CD163. The filter was re-probed with GAPDH as a loading control. The blot is representative of three experiments with reproducible results. Densitometric analysis, including standard deviation, is provided (significance was considered as follow: ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗p<0.05).

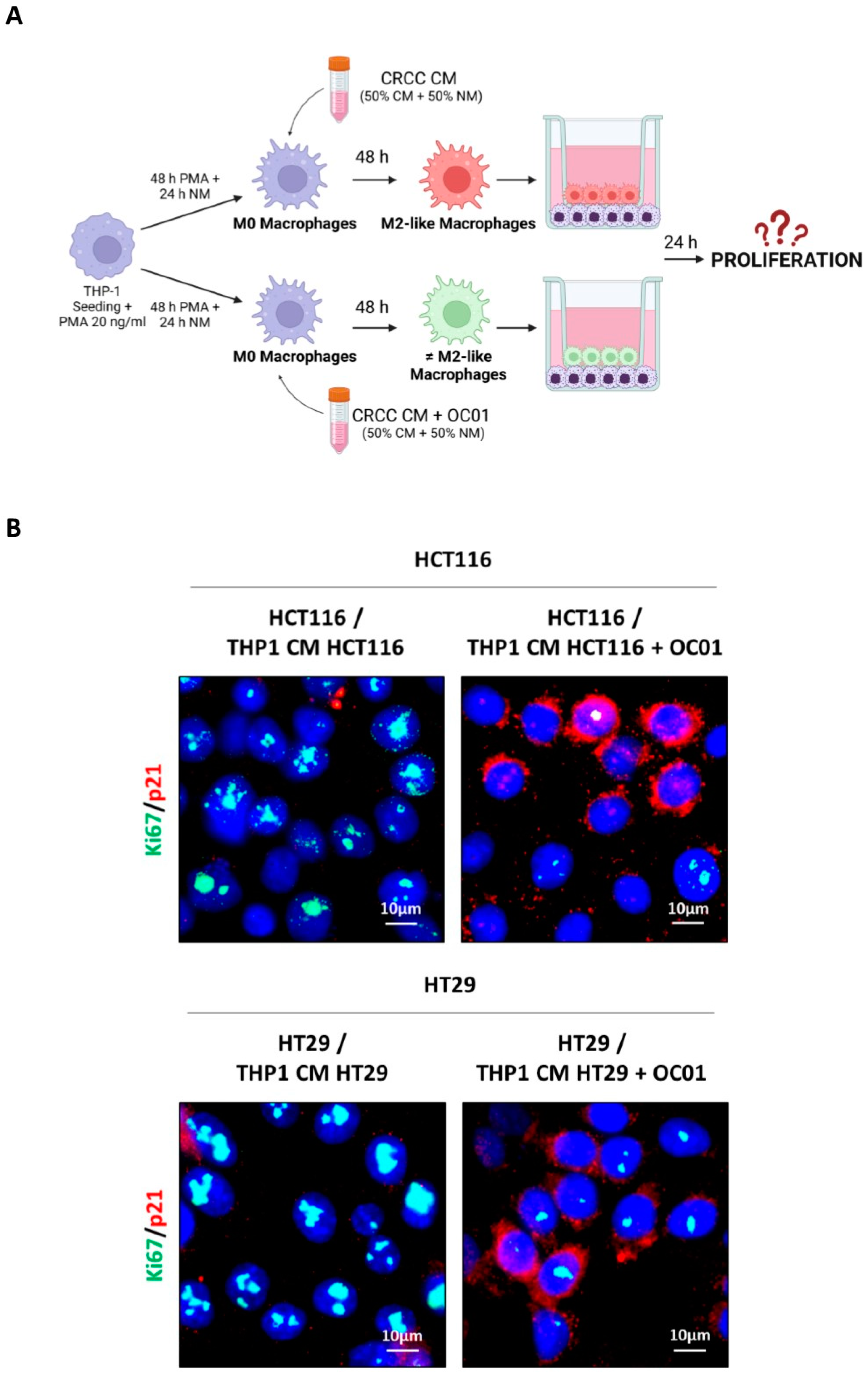

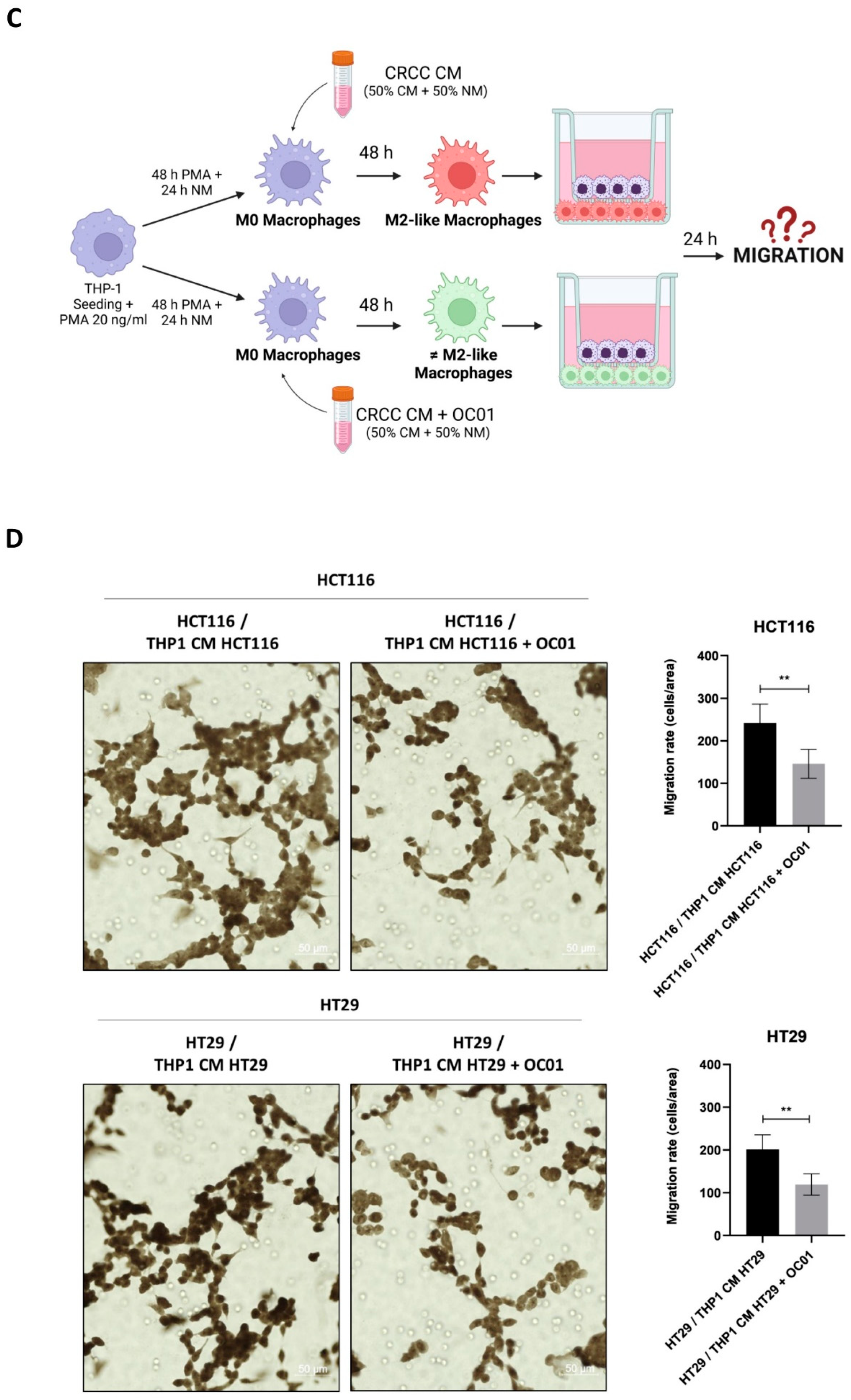

3.5. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 Supernatant-Induced Macrophage Reprogramming Reduces Proliferation and Migration of HCT116 and HT29 Colorectal Cancer Cells

We have demonstrated that the CM of cancer cells promotes the differentiation of macrophages towards an M2-like phenotype, associated with anti-inflammatory properties. In contrast, CM of cancer cells exposed to Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 supernatant induces a more inflammatory macrophage phenotype, which differs from the M2-like.

To investigate how these differentially polarized macrophages impact the behavior of HCT116 and HT29 cancer cells, a non-contact co-culture system using Transwell inserts was employed. This system allowed the exchange of soluble factors without direct cell-cell contact. Differentiated macrophages (M0 macrophages exposed to CM from HCT116 or HT29 cells, with or without probiotic treatment for 48 hours) were seeded in the upper compartment of the Transwell system, while cancer cells were plated in the lower compartment (

Figure 5A). After 24 hours of co-culture, the proliferation of cancer cells was analyzed by assessing the expression of the proliferative marker Ki67 and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21waf/Cip1 by immunofluorescence. As shown in

Figure 5B co-culture with M2-like macrophages resulted in increased Ki67 expression and decreased p21waf/Cip1 in HCT116 and HT29 cells. In contrast, when cancer cells were co-cultured with more-inflammatory macrophages differentiated with CM from cancer cells treated with

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 supernatant, a decrease in cancer cell proliferation was observed, with an increase in p21waf/Cip1 and a reduction in Ki67 expression.

The impact of different macrophage phenotypes on cancer cell migration was further investigated. In this setup, cancer cells were plated in the upper compartment, while differentiated macrophages were seeded in the lower compartment of Transwell system (

Figure 5C). After 24 hours, the number of cancer cells that migrated through the porous membrane was quantified. Co-culture with inflammatory macrophages differentiated from cancer cells pre-treated with

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 supernatant significantly reduced the migration of HCT116 and HT29 cells compared to co-culture with M2 macrophages (

Figure 5D).

These results suggest that M2-like macrophages, which are more likely to promote a pro-tumoral environment, enhance cancer cell proliferation and migration, while macrophages with a more inflammatory phenotype, induced by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 metabolites in the TME, inhibit these processes.

4. Discussion

The tumor mass exists within a complex microenvironment that includes cancer cells as well as stromal components such as fibroblasts, endothelial cells, immune cells, and adipocytes. These stromal cells engage in active communication with cancer cells through the exchange of soluble factors, including cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors, establishing a bidirectional interactions. This dynamic crosstalk can drive stromal cells to adopt more aggressive and malignant phenotypes, contributing to tumor growth. As a result, the TME is increasingly recognized as a critical player in tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis [

9].

In CRC, intestinal macrophages are the predominant immune cells infiltrating the tumor [

41]. In their resting state, these macrophages exhibit an unpolarized M0-like phenotype [

42]. However, signals from the TME, particularly those secreted by cancer cells, influence macrophage polarization, promoting them toward either a classically activated M1-like phenotype or an alternatively activated M2-like phenotype [

15]. Additionally, the gut microbiota closely interacts with macrophages, shaping their behavior within TME, further influencing tumor growth [

3]. The interplay between immune cells, microbiota, and cancer cells significantly affect the development and progression of CRC [

43].

Here, we investigated the effect of the Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 supernatant on the secretome of CRC cells. Understanding how these probiotic metabolites alter the secretome is crucial, as these modifications can significantly affect the TME, potentially promoting tumor regulation and slowing its dissemination. Of note, one of the key processes influenced by the secretome is the polarization of macrophages into TAMs.

In the TME, TAMs predominantly adopt an M2-like phenotype. This polarization is driven by the abundance of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-10, which promote macrophage conversion into the M2 phenotype. Additionally, the metabolic landscape of the TME plays a significant role, with lactate being a driver of M2 phenoconversion [

44]. M1 and M2 differ also in terms of energetic metabolism, with the former showing predominantly aerobic glycolytic metabolism and low production of ATP (thus relying on the availability of huge amount of glucose) while the latter exploit at best the mitochondrial respiration [

42]. Cancer cells predominantly utilize glucose through aerobic glycolysis to support their rapid proliferation, thereby limiting glucose availability for other cells. Consequently, macrophages within the TME lack glucose and rely on oxidative phosphorylation for energy production, which supports their M2 polarization. Together, these conditions create an immunosuppressive environment that facilitates tumor progression and immune evasion [

17].

Our study assessed the expression of NLRP3 to evaluate whether the macrophages polarized by CRC cells CM exhibited a pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory phenotype. Our results demonstrated that treating M0 macrophages with HCT116 and HT29 CM significantly reduced the levels of both NLRP3 and ROS. However, when cancer cells are pre-treated with

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01, we observed a marked increase in NLRP3 and ROS levels. These findings suggested a differential inflammatory state, with a shift towards a more inflammatory phenotype in the latter scenario. This shift in macrophage inflammatory status appeared to be closely linked to alterations in the TME, particularly in the secretome of CRC cells. To define the polarization phenotype, we analyzed the expression of CD206 and CD163, surface markers characteristic of M2c macrophages [

17]. These markers were significantly elevated when macrophages were treated with CM derived from untreated cancer cells, indicating a pronounced M2c polarization. Conversely, the presence of the probiotic led to a notable decrease in CD206 and CD163 levels, supporting that

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 modified the TME by altering the cancer cell secretome. The M2c macrophages are known to be strongly induced by TGF-β [

16,

17]. Notably, the probiotic treatment induced a reduction in TGF-β levels in both HCT116 and HT29 cells. This decrease in TGF-β likely played a pivotal role in modulating macrophage polarization, specifically reducing the M2-like phenotype.

In summary, these findings underscore the capacity of the CRC cell secretome to induce an M2c-like phenotype in macrophages, driven in part by TGF-β. The presence of the probiotic reduced TGF-β levels and mitigated the M2c polarization, highlighting a critical interplay between the secretome of cancer cells and macrophage behavior.

The anti-inflammatory phenotype of M2-like macrophages, particularly M2c, is widely associated with tumor-promoting activities, whereas a more inflammatory phenotype is linked to anti-tumor functions. By mimicking the in vivo interactions between cancer cells and TAMs, we further investigated these functional differences, establishng a co-culture system using transwells. This approach allowed us to evaluate how macrophages with distinct polarization states and inflammatory status impact tumor progression. In agreement with our previous findings, macrophages exhibiting an M2c-like phenotype, induced by CM from untreated cancer cells, were associated with reduced expression of p21 and increased expression of Ki67 in cancer cells, suggesting enhanced proliferative activity. Furthermore, these macrophages promoted cancer cell migration, as indicated by the greater number of migrated cells observed. Conversely, macrophages with a more inflammatory phenotype, induced by CM derived from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01-pretreated CRC cells, displayed the opposite effect. These macrophages were associated with increased expression of p21 and decreased expression of Ki67 in cancer cells, reflecting suppressed proliferation, along with a significant reduction in cancer cell migration, as evidenced by fewer migrated cells in the co-culture system.

Overall, our results suggest that

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 metabolites may modulate the cytokine secretion pattern of CRC cells, potentially driving macrophages toward a more pro-inflammatory state. This modulation could counteract the immune-suppressive signaling within the TME, offering a promising approach to altering macrophage polarization. The changes observed in cytokine expression suggest a shift toward a more inflammatory macrophage profile, potentially aligning with an M1-like phenotype or an intermediate phenotype between M1 and M2, such as M2b. M2b macrophages are known to be induced by IL-1β or LPS and express markers such as IL-10, IL-1 receptor, TNF-α, and M1 marker CD86 [

45]. These macrophages are typically associated with a more balanced immune response, favoring a more pro-inflammatory environment within the TME. However, further investigation is required to definitively classify this phenotype and elucidate the precise mechanisms involved in macrophage polarization and activation.

In conclusion, this study highlights the potential of probiotic metabolites as an adjuvant therapy for CRC. By focusing on their ability to influence the TME, specifically through modulating the polarization and activation of TAMs, we aim to uncover novel strategies to counteract immune suppression. Considering the critical role of the gut microbiota in CRC progression and treatment outcomes, these findings provide valuable insights into how probiotics can restore eubiosis, suppress tumor growth, and enhance the efficacy of conventional therapies. Ultimately, this research contributes to the development of more effective, personalized approaches to CRC management by addressing both the microbiota and immune components of the TME.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.G., L.V., and C.I.; methodology, B.G., L.V., and A.F.; validation, B.G. and L.V.; formal analysis, B.G. and L.V.; investigation, B.G. and L.V.; resources B.G. and L.V.; data curation, B.G., L.V., and A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, B.G.; writing—review and editing, C.I.; visualization, C.I., A.F., A.A., and M.P.; supervision, C.I.; project administration, C.I., A.A., M.P.; funding acquisition, C.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Probiotical S.p.A.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

B.G. was supported with PhD fellowship granted by Comoli, Ferrari & SpA (Novara, Italy). L.V. was supported with post-doctoral fellowship granted by Probiotical S.p.A (Novara, Italy). A.F. is recipient of a post-doctoral fellowship granted by Fondazione Veronesi (FUV 2024) (Milan, Italy). The fluorescence microscope was donated by Comoli, Ferrari & SpA (Novara, Italy). Thanks are due to Associazione per la Ricerca Medica “Ippocrate-Rhazi” (Novara, Italy) and to Consorzio Interuniversitario per le Biotecnologie (CIB, Trieste, Italy) for support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

TAMs

CRC

TME

IL

CM

TGF

ECM

TNF

ROS

PMA

COOH-NPs

NM

CSF-1 |

Tumor-associated macrophages

Colorectal cancer

Tumor microenvironment

Interleukin

Conditioning medium

Tumor growth factor

Extracellular matrix

Tumor necrosis factor

Reactive oxygen species

Phorbol-12-Myristate-13-Acetate

carboxy-functionalized nanoparticles

Normal media

colony-stimulating factor-1 |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 May-Jun;74(3):229-263. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.H.; Kwong, T.N.Y.; Wu, C.Y.; Yu, J. Clinical applications of gut microbiota in cancer biology. Semin Cancer Biol. 2019 Apr;55:28-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács, T.; Mikó, E.; Ujlaki, G.; Sári, Z.; Bai, P. The Microbiome as a Component of the Tumor Microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1225:137-153. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnière, J.; Raisch, J.; Veziant, J.; Barnich, N.; Bonnet, R.; Buc, E.; Bringer, M.A.; Pezet, D.; Bonnet, M. Gut microbiota imbalance and colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016 Jan 14;22(2):501-18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomaa, E.Z. Human gut microbiota/microbiome in health and diseases: a review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2020 Dec;113(12):2019-2040. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, T.; Cui, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Song, H.; Shang, D. Gut microbiome: decision-makers in the microenvironment of colorectal cancer. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023 Dec 12;13:1299977. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, T.; Vergara, D.; Fanini, F.; Maffia, M.; Bravaccini, S.; Pirini, F. Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Aug 12;21(16):5786. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, S.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Pazienza, V.; Preto, A. Modulation of the Tumor Microenvironment by Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids: Impact in Colorectal Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Mar 7;24(6):5069. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, N.M.; Simon, M.C. The tumor microenvironment. Curr Biol. 2020 Aug 17;30(16):R921-R925. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Cao, X. The origin and function of tumor-associated macrophages. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015 Jan;12(1):1-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanmee, T.; Ontong, P.; Konno, K.; Itano, N. Tumor-associated macrophages as major players in the tumor microenvironment. Cancers (Basel). 2014 Aug 13;6(3):1670-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A.; Allavena, P.; Sica, A.; Balkwill, F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008 Jul 24;454(7203):436-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.; Yang, C.; Wang, S.; Shi, D.; Zhang, C.; Lin, X.; Liu, Q.; Dou, R.; Xiong, B. Crosstalk between cancer cells and tumor associated macrophages is required for mesenchymal circulating tumor cell-mediated colorectal cancer metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2019 Mar 30;18(1):64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A.; Sica, A.; Sozzani, S.; Allavena, P.; Vecchi, A.; Locati, M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004 Dec;25(12):677-86. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orecchioni, M.; Ghosheh, Y.; Pramod, A.B.; Ley, K. Macrophage Polarization: Different Gene Signatures in M1(LPS+) vs. Classically and M2(LPS-) vs. Alternatively Activated Macrophages. Front Immunol. 2019 May 24;10:1084. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01084. Erratum in: Front Immunol. 2020 Feb 25;11:234. PMID: 31178859; PMCID: PMC6543837. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.O.; Sica, A.; Mantovani, A.; Locati, M. Macrophage activation and polarization. Front Biosci. 2008 Jan 1;13:453-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Liu, G.; Li, Y.; Pan, Y. Metabolic Reprogramming Induces Macrophage Polarization in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2022 Jul 7;13:840029. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Liu X, Wan C, Liu Y, Wang Y, Meng C, Zhang Y, Jiang C. NLRP3 inflammasome mediates M1 macrophage polarization and IL-1β production in inflammatory root resorption. J Clin Periodontol. 2020 Apr;47(4):451-460. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Xue, Z.; Qiu, T.; Chen, J. Loss of NLRP3 reduces oxidative stress and polarizes intratumor macrophages to attenuate immune attack on endometrial cancer. Front Immunol. 2023 Apr 3;14:1165602. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Zeng, Q.; Wu, Z.; Huang, L.; Sun, T.; Ling, C.; Zhang, B.; Chen, C.; Wang, H. Berberine inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation and proinflammatory macrophage M1 polarization to accelerate peripheral nerve regeneration. Neurotherapeutics. 2024 Jul;21(4):e00347. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, N.; Jeltema, D.; Duan, Y.; He, Y. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: An Overview of Mechanisms of Activation and Regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Jul 6;20(13):3328. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisitpongpun, P.; Potup, P.; Usuwanthim, K. Oleamide-Mediated Polarization of M1 Macrophages and IL-1β Production by Regulating NLRP3-Inflammasome Activation in Primary Human Monocyte-Derived Macrophages. Front Immunol. 2022 Apr 19;13:856296. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Kuang, T.; Liu, L.; Deng, W. The role of innate immune cells in the colorectal cancer tumor microenvironment and advances in anti-tumor therapy research. Front Immunol. 2024 Jul 19;15:1407449. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Li, Y. Gut microbiota and tumor-associated macrophages: potential in tumor diagnosis and treatment. Gut Microbes. 2023 Dec;15(2):2276314. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.; Suo, H.; Song, J. An Update on the Pivotal Roles of Probiotics, Their Components, and Metabolites in Preventing Colon Cancer. Foods. 2023 Oct 9;12(19):3706. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Liao, Y.; Wei, C.; Ma, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, B.; Ji, H.; Wang, D.; Tang, D. Potential Ability of Probiotics in the Prevention and Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2023 Aug 17;17:11795549231188225. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallino, L.; Garavaglia, B.; Visciglia, A.; Amoruso, A.; Pane, M.; Ferraresi, A.; Isidoro, C. Cell-free Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 supernatant suppresses IL-6-induced proliferation and invasion of human colorectal cancer cells: Effect on β-Catenin degradation and induction of autophagy. J Tradit Complement Med. 2023 Feb 21;13(2):193-206. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraresi, A.; Girone, C.; Maheshwari, C.; Vallino, L.; Dhanasekaran, D.N.; Isidoro, C. Ovarian Cancer Cell-Conditioning Medium Induces Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Phenoconversion through Glucose-Dependent Inhibition of Autophagy. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 May 23;25(11):5691. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garavaglia, B.; Vallino, L.; Ferraresi, A.; Esposito, A.; Salwa, A.; Vidoni, C.; Gentilli, S.; Isidoro, C. Butyrate Inhibits Colorectal Cancer Cell Proliferation through Autophagy Degradation of β-Catenin Regardless of APC and β-Catenin Mutational Status. Biomedicines. 2022 May 13;10(5):1131. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekkapongpisit, M.; Giovia, A.; Nicotra, G.; Ozzano, M.; Caputo, G.; Isidoro, C. Labeling and exocytosis of secretory compartments in RBL mastocytes by polystyrene and mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:1829-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidoni, C.; Secomandi, E.; Castiglioni, A.; Melone, M.A.B.; Isidoro, C. Resveratrol protects neuronal-like cells expressing mutant Huntingtin from dopamine toxicity by rescuing ATG4-mediated autophagosome formation. Neurochem Int. 2018 Jul;117:174-187. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choconta, J.L.; Labi, V.; Dumbraveanu, C.; Kalpachidou, T.; Kummer, K.K.; Kress, M. Age-related neuroimmune signatures in dorsal root ganglia of a Fabry disease mouse model. Immun Ageing. 2023 May 12;20(1):22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, X.; Chen, B.; Yang, Z. The Role of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Colorectal Carcinoma Progression. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;45(1):356-365. https://doi.org/10.1159/000486816. Epub 2018 Jan 19. Erratum in: Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;48(6):2659. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, K.V.; Deng, M.; Ting, J.P. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019 Aug;19(8):477-489. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango Duque, G.; Descoteaux, A. Macrophage cytokines: involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front Immunol. 2014 Oct 7;5:491. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang F, Wang H, Wang X, Jiang G, Liu H, Zhang G, Wang H, Fang R, Bu X, Cai S, Du J. TGF-β induces M2-like macrophage polarization via SNAIL-mediated suppression of a pro-inflammatory phenotype. Oncotarget. 2016 Aug 9;7(32):52294-52306. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruytinx, P.; Proost, P.; Van Damme, J.; Struyf, S. Chemokine-Induced Macrophage Polarization in Inflammatory Conditions. Front Immunol. 2018 Sep 7;9:1930. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldner MJ, Neurath MF. TGFβ and the Tumor Microenvironment in Colorectal Cancer. Cells. 2023 Apr 12;12(8):1139. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, R.M.; Mortimer, T.O.; O'Neill, K.L. Cytokines: Can Cancer Get the Message? Cancers (Basel). 2022 Apr 27;14(9):2178. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Y. Tumor-associated macrophages: from basic research to clinical application. J Hematol Oncol. 2017 Feb 28;10(1):58. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A.; Allavena, P.; Marchesi, F.; Garlanda, C. Macrophages as tools and targets in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022 Nov;21(11):799-820. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Deng, Q.; Hu, Y.; Dong, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, C. Macrophage Polarization, Metabolic Reprogramming, and Inflammatory Effects in Ischemic Heart Disease. Front Immunol. 2022 Jul 18;13:934040. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mola, S.; Pandolfo, C.; Sica, A.; Porta, C. The Macrophages-Microbiota Interplay in Colorectal Cancer (CRC)-Related Inflammation: Prognostic and Therapeutic Significance. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Sep 18;21(18):6866. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehla, K.; Singh, P.K. Metabolic Regulation of Macrophage Polarization in Cancer. Trends Cancer. 2019 Dec;5(12):822-834. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang LX, Zhang SX, Wu HJ, Rong XL, Guo J. M2b macrophage polarization and its roles in diseases. J Leukoc Biol. 2019 Aug;106(2):345-358. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

THP-1 cell differentiation into M0-macrophage. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental design. THP-1 cells were plated and treated with or without 20 ng/ml of PMA for 48 hours, followed by a one-day recovery in normal media (NM) (Created with BioRender). (B) Cell morphology images of THP-1 were obtained using phase-contrast microscopy (scale bar = 100 μm, magnification = 20×). (C) Cell homogenates were analyzed by Western blotting for the expression of the M0 macrophage marker CD68. The filter was re-probed with GAPDH as a loading control. The blot are representative of three experiments with reproducible results. Densitometric analysis, including standard deviation, is provided (significance was considered as follow: ∗∗p<0.01). (D) THP-1 cells were plated onto coverslips and treated as described. At the end of the treatment, cells were stained for the M0 macrophage marker CD68 (red) and imaged using fluorescence microscopy (scale bar = 25 μm, magnification = 63×). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Representative images for each condition are shown. (E) THP-1 cells were plated onto coverslips and treated as described. At the end of the treatment, cells were incubated with Lysotracker™ probe for 10 minutes at 37°C and then treated with 25 µg/ml COOH-NPs for an additional 10 minutes to evaluate their inclusion into lysosomes (yellow signal). Images were acquired using fluorescence microscopy (scale bar = 25 μm, magnification = 63×). Representative images for each condition are shown.

Figure 1.

THP-1 cell differentiation into M0-macrophage. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental design. THP-1 cells were plated and treated with or without 20 ng/ml of PMA for 48 hours, followed by a one-day recovery in normal media (NM) (Created with BioRender). (B) Cell morphology images of THP-1 were obtained using phase-contrast microscopy (scale bar = 100 μm, magnification = 20×). (C) Cell homogenates were analyzed by Western blotting for the expression of the M0 macrophage marker CD68. The filter was re-probed with GAPDH as a loading control. The blot are representative of three experiments with reproducible results. Densitometric analysis, including standard deviation, is provided (significance was considered as follow: ∗∗p<0.01). (D) THP-1 cells were plated onto coverslips and treated as described. At the end of the treatment, cells were stained for the M0 macrophage marker CD68 (red) and imaged using fluorescence microscopy (scale bar = 25 μm, magnification = 63×). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Representative images for each condition are shown. (E) THP-1 cells were plated onto coverslips and treated as described. At the end of the treatment, cells were incubated with Lysotracker™ probe for 10 minutes at 37°C and then treated with 25 µg/ml COOH-NPs for an additional 10 minutes to evaluate their inclusion into lysosomes (yellow signal). Images were acquired using fluorescence microscopy (scale bar = 25 μm, magnification = 63×). Representative images for each condition are shown.

Figure 2.

The secretome of OC01 cell-free supernatant-treated colorectal cancer cell induces NLRP3 activation. (A-B) Schematic representation of the experimental design. HCT116 and HT29 cells were plated and treated or not with 10 µl of OC01 cell-free supernatant for 48 hours. The treatment was renewed every 24 hours. At the end of the treatment period, the CM was collected and used to treat the differentiated M0 macrophages for 48 hours (Created with BioRender). (C) Cell homogenates were analyzed by Western blotting to assess the expression of NLRP3. The blot is representative of three experiments with reproducible results. The filter was re-probed with β-actin or GAPDH as a loading control. Densitometric analysis, including standard deviation, is provided (significance was considered as follow: ∗p<0.05). (D) THP-1 cells were plated onto coverslips and differentiated and treated ad previously described. After 48 hours of treatment, cells were labeled with MitoSOX™. Coverslips were directly visualized using a fluorescence microscope (scale bar = 25 μm, magnification = 63×). The data presented are representative of multiple fields for each condition. Graphs report the quantification of the fluorescence intensity per cell (significance was considered as follow: ∗∗∗∗p<0.0001).

Figure 2.

The secretome of OC01 cell-free supernatant-treated colorectal cancer cell induces NLRP3 activation. (A-B) Schematic representation of the experimental design. HCT116 and HT29 cells were plated and treated or not with 10 µl of OC01 cell-free supernatant for 48 hours. The treatment was renewed every 24 hours. At the end of the treatment period, the CM was collected and used to treat the differentiated M0 macrophages for 48 hours (Created with BioRender). (C) Cell homogenates were analyzed by Western blotting to assess the expression of NLRP3. The blot is representative of three experiments with reproducible results. The filter was re-probed with β-actin or GAPDH as a loading control. Densitometric analysis, including standard deviation, is provided (significance was considered as follow: ∗p<0.05). (D) THP-1 cells were plated onto coverslips and differentiated and treated ad previously described. After 48 hours of treatment, cells were labeled with MitoSOX™. Coverslips were directly visualized using a fluorescence microscope (scale bar = 25 μm, magnification = 63×). The data presented are representative of multiple fields for each condition. Graphs report the quantification of the fluorescence intensity per cell (significance was considered as follow: ∗∗∗∗p<0.0001).

Figure 3.

OC01 cell-free supernatant reduces TGF-β expression levels in HCT116 and HT29 cells. Cells were seeded in Petri dishes and treated with or without 10 µl of OC01 cell-free supernatant for 48h, with medium and treatment renewed every day. Agarose gel electrophoresis was used to visualize the PCR products for IL-8, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-18, IL-6, TNF-α, and TGF-β. The cytokine expression profiles shown are representative of three experiments with reproducible results.

Figure 3.

OC01 cell-free supernatant reduces TGF-β expression levels in HCT116 and HT29 cells. Cells were seeded in Petri dishes and treated with or without 10 µl of OC01 cell-free supernatant for 48h, with medium and treatment renewed every day. Agarose gel electrophoresis was used to visualize the PCR products for IL-8, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-18, IL-6, TNF-α, and TGF-β. The cytokine expression profiles shown are representative of three experiments with reproducible results.

Figure 5.

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01-driven macrophage reprogramming reduces the proliferation and migration of HCT116 and HT29 cells. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental design. Macrophages were plated and differentiated within Transwell inserts using the CM from CRC cells pre-treated or not with 10 µl of OC01 cell-free supernatant for 48 hours. The inserts were then transferred into a 24-well plate pre-seeded with CRC cells on coverslips for 24 hours (Created with BioRender). (B) Following 24 hours of co-culture, HCT116 and HT29 cells were processed for immunofluorescence staining of Ki67 (green) and p21 (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. The cells were photographed under fluorescence microscopy (scale bar = 10 μm, magnification = 63×). Representative images for each condition are shown. (C) Schematic representation of the experimental design. HCT116 and HT29 cells were cultured for 48 hours, then trypsinized, resuspended in serum-free medium, and plated into Transwell inserts. These inserts were positioned above differentiated THP-1 macrophages (for 48 hours with CM from CRC cells, pre-treated or untreated with 10 µl of OC01 cell-free supernatant) in a 24-well plate containing complete medium for 24 hours (Created with BioRender). (D) After 24 hours of co-culture, migrated HCT116 and HT29 cells were imaged in random fields using an Axioscan 7 microscope (scale bar = 50 µm, magnification = 20×). Representative images for each condition are shown, along with quantification of migrated cells, presented with standard deviation (statistical significance: ∗∗p < 0.01).

Figure 5.

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01-driven macrophage reprogramming reduces the proliferation and migration of HCT116 and HT29 cells. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental design. Macrophages were plated and differentiated within Transwell inserts using the CM from CRC cells pre-treated or not with 10 µl of OC01 cell-free supernatant for 48 hours. The inserts were then transferred into a 24-well plate pre-seeded with CRC cells on coverslips for 24 hours (Created with BioRender). (B) Following 24 hours of co-culture, HCT116 and HT29 cells were processed for immunofluorescence staining of Ki67 (green) and p21 (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. The cells were photographed under fluorescence microscopy (scale bar = 10 μm, magnification = 63×). Representative images for each condition are shown. (C) Schematic representation of the experimental design. HCT116 and HT29 cells were cultured for 48 hours, then trypsinized, resuspended in serum-free medium, and plated into Transwell inserts. These inserts were positioned above differentiated THP-1 macrophages (for 48 hours with CM from CRC cells, pre-treated or untreated with 10 µl of OC01 cell-free supernatant) in a 24-well plate containing complete medium for 24 hours (Created with BioRender). (D) After 24 hours of co-culture, migrated HCT116 and HT29 cells were imaged in random fields using an Axioscan 7 microscope (scale bar = 50 µm, magnification = 20×). Representative images for each condition are shown, along with quantification of migrated cells, presented with standard deviation (statistical significance: ∗∗p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Overview of the cytokines analyzed, including their amplicon lengths and the sequences of the forward and reverse primers used for amplification.

Table 1.

Overview of the cytokines analyzed, including their amplicon lengths and the sequences of the forward and reverse primers used for amplification.

| Primer |

Amplicon Lenght |

Forward

5’ -> 3’

|

Reverse

3’ -> 5’

|

| IL-8 |

455 bp |

GGACAAGAGCCAGGAAGAAA |

CCTACAACAGACCCACACAATA |

|

IL-1β

|

567 bp |

ATGACCTGAGCACCTTCTTTC |

TCTCTGGGTACAGCTCTCTTTA |

| IL-10 |

677 bp |

GAACCAAGACCCAGACATCAA |

CCAAGCCCAGAGACAAGATAAA |

| IL-6 |

427 bp |

CAGCTATGAACTCCTTCTCCAC |

CTGGCTTGTTCCTCACTACTC |

| IL-18 |

505 bp |

CCAAGGAAATCGGCCTCTATT |

GTCTTGAACACCTGACCTCTG |

|

TNF-α

|

828 bp |

ATCTACTCCCAGGTCCTCTTC |

CCCGGTCTCCCAAATAAATACA |

|

TGF-β

|

662 bp |

GTGGAAACCCACAACGAAATC |

GTGTCCAGGCTCCAAATGTA |

| β-actin |

719 bp |

GATCAAGATCATTGCTCCTCCTGAGCGCA |

GTCTCAAGTCAGTGTACAGGTAAGCCCT |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).