1. Introduction

Throughout history, shipping has been regarded as an international business. Ships travel between different ports, crossing various national and international waters, most of the time beyond the reach of nation states and their regulations. In addition, some shipping organizations have allowed their ships to sail under flags of convenience (FOC). These decisions have allowed them to choose between different regulatory regimes in order to minimize costs and maximize profits [

1]. This arrangement contributed to numerous maritime accidents, incidents and environmental disasters throughout history [

2], with human and organizational factors being the main causes [

3].

In order to improve maritime safety, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has created a series of measures and regulations. Of particular note are the International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW), with its amendments and revisions, and the International Safety Management Code (ISM) [

4]. The STCW aims to provide an international standard for the training of seafarers and the ISM aims to provide organizations with an international standard for the development of a safety management system (SMS) for their ships. The identification of risks, the establishment of appropriate safeguards and compliance with safety rules and procedures are the essential components of the SMS [

5]. Over time, the living and working conditions of seafarers in the industry proved to be problematic. The incentive for improvement came from the International Labor Organization (ILO) in the form of the Maritime Labor Convention (MLC) in 2006 [

6]. Among the numerous requirements relating to living and working conditions, particular emphasis was placed on the implementation of and compliance with occupational health and safety measures to ensure a safe working environment on board, i.e., the development of a safety culture [

7]. At the same time, the ILO emphasized that the implementation of the MLC, 2006 should be consistent with all relevant IMO instruments, including the ISM [

7]. In addition to the technical requirements for ships contained in SOLAS, the above measures should strengthen the human factor by improving the safety culture and competence of seafarers. In other words, the above measures should be sufficient to create a resilient barrier system on board ships.

After the introduction of ISM in the initial phase, the number of maritime accidents caused by human error on ships decreased (e.g., [

8]). However, another study found the paradox that the period after the introduction of ISM was associated with a decrease in personal injuries and an increase in ship accidents [

9]. However, previous research has shown that most incidents or accidents in the industry are due to the following causes or a combination thereof: inadequate training and experience, lack of competence, poor communication, lack of safety culture, poor situation assessment and decision-making errors, inadequate system monitoring and maintenance and/or unlearning from previous accidents [

10,

11,

12,

13].

To gain an insight into the current state of the industry, the available statistics on reported accidents and incidents were examined. Between 2014 and 2022, 59.1% of reported accidents were attributed to human factors. In addition, ship operations were found to be the most important factor contributing to accidental events (69.9%) [

14]. The data presented are consistent with the findings of previous studies showing that maritime regulations lead to relatively successful safety outcomes [

15,

16] and underline the findings of Schröder-Hinrichs et al. [

17], who conclude that the impact of safety regulations on a true, proactive approach to maritime safety is questionable.

In practice, the performance of ship operation is an important factor related to accidents and incidents, and the basic elements affecting the ship’s barrier system have not been sufficiently studied. Both problems are related to the human factor in practice. Therefore, the question arises whether the implementation of the provisions of the maritime regulatory framework can affect the elements related to the ship’s barrier systems, and the aim of this study is to fill this gap. The approach used in this study is based on system functionality assessment. In the literature, system functionality is described as reliability. Thus, system reliability reflects the actual performance of a system, i.e., the ability to maintain the desired performance under working conditions [

18,

19].

The objectives of the study are therefore: 1) to investigate and determine the regulatory safety requirements; 2) to investigate and determine the essential factors associated with the shipboard barrier system; and 3) to investigate the influence of regulatory safety requirements and seafarer characteristics (age, seagoing service and tenure) on the elements associated with the shipboard barrier system. The purpose of introducing the age variable is highlighted in the literature, and the purpose of introducing the seagoing service time and tenure variables is to investigate whether the logical assumptions that working for the same organization for an extended period of time and/or seagoing service time may lead to specific work patterns/habits that could affect the elements associated with shipboard operations.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a literature review on the topic;

Section 3. Methodology, describes the dataset and methodological approach;

Section 4. Results provides the results of the exploratory analyzes used, the modeling approach and the main findings of each model;

Section 5 provides a discussion and implications, followed by a conclusion in

Section 6.

2. Literature Review

The requirements established by the IMO [

5] and the ILO [

7] are of particular relevance to this study. The basic requirement is that shipping organizations should establish and implement safety management systems (SMS) for the ship(s) they manage to support and promote the development of safe operations [

20,

21] and a safety culture in shipping [

5]. The purpose of maritime regulations can be seen as a method to reduce the impact of market- and workplace-related risks and/or to prevent maritime accidents and marine pollution [

22]. Furthermore, Størkersen et al. [

9] state that “cost efficiency” is the most important factor for shipping companies and that ISM is a balance to a competitive global market. Theoretically, it should be functional to increase maritime safety, reduce risks associated with shipping operations, and improve human performance. At the same time, the ISM provides only general guidelines to achieve the set goals [

23,

24]. According to same sources these guidelines can be interpreted differently depending on the organization’s commitment, values, and beliefs.

Consequently, numerous studies have pointed out a paradox with SMS’s. They have identified three main issues that can affect daily tasks and activities on board and create a gap between SMS requirements and actual work practice: application phase [

25,

26], the standardization of SMS leading to an increase in paperwork and bureaucracy [

16,

27], and the lack of a well-developed safety culture [

15,

28].

The importance of a good safety culture has been highlighted in numerous studies and recognized as a leading indicator of safety outcomes in similar industries (e.g., [

29]). Previous studies of safety culture have found that a good safety culture is based primarily on perceptions of senior managers’ commitment to safety [

22,

30]. Such perceptions are reflected in management safety practices and can lead to compliance behaviors and good performance [

31]. Similar studies conducted in the maritime environment suggest that shipboard safety culture is distinctly different from engagement in shipping organizations and should be considered separately (e.g., [

28,

32,

33]).

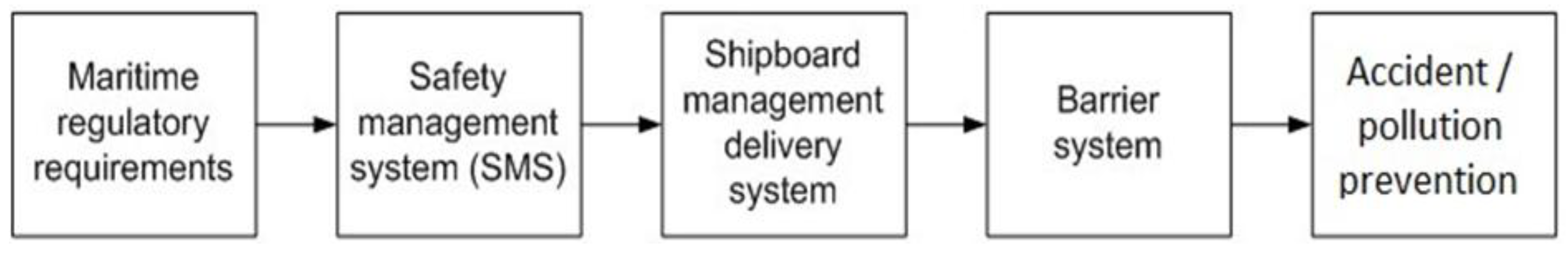

According to [

34], management delivery is an essential component of SMS. In addition, Li et al. [

35] state that an appropriate management delivery system should improve the management of safety barriers. Schmitz et al. [

36] define a barrier system as a set of measures designed to prevent causes from becoming consequences. Barriers can be organizational, technical, non-technical, human, or a combination thereof [

37,

38]. Managing safety barriers is a critical activity for maintaining the process safety of any operating facility [

39]. Furthermore, Schmitz et al. [

36] state that barrier-supportive management systems are indeed non-technical, as they are based on work processes and procedures that prioritize human actions and decisions. Nevertheless, studies have shown that inadequate procedures can be an additional factor contributing to accidents and that the quality of safety rules and procedures should minimize the potential for hazards [

40,

41]. In addition, previous studies have shown that management practices in companies and on-board ships are different, as are management delivery systems. The flowchart of maritime regulatory requirements and shipboard safety systems is shown in

Figure 1.

The early study by Bhattacharya [

16] examined the effectiveness of ISM. According to the results, the use of ISM was perceived differently by shore-based managers and crew members in terms of its intent and associated work practices. Specifically, crew members criticized the use of standardized SMS and generic work procedures. In addition, poor communication and lack of trust between ship and shore management resulted in “formal” compliance by crewmembers. The above comments are corroborated by the results of a similar study [

15]. Their results show that ship operating plans and a “vast amount of deviation” from safety management systems have a significant impact on “very serious accidents”.

At the beginning of the last decade, a new direction for improvement was taken, based on the human-centered approach of the Health, Safety, Environment and Quality (HSEQ) management system [

42]. The focus is on establishing common standards for the ship and its systems, ensuring safe working and living conditions, and implementing effective operating procedures. According to the same source, the new management systems should be based on common sense. In practice, the previous SMSs have been expanded to facilitate compliance with the relevant requirements.

In turn, the standardization of SMS has proven to be important. Numerous studies have addressed the issue of standardization of SMS. According to [

43], there is an industry that offers prefabricated SMS as a standard commodity. In addition, organizations typically include all regulatory requirements and expectations rather than focusing on safety issues. Instead of being concise and practical, systems have become too extensive and bureaucratic; the focus has shifted to documentation, creating additional risks that compromise safety [

27,

44]. Numerous studies emphasize that safety procedures should be flexible and practicable to support safe work practices [

43,

45], and minimum standards for written procedures should be implemented in the maritime industry [

46]. While many organizations have attempted to simplify their SMS, studies show that these efforts usually end up with the number of rules and procedures remaining almost the same [

32,

47]. Størkersen et al. [

9] note that safety management systems created using this method can also contribute to overregulation.

A recent study has shown that such an approach leads to numerous violations despite proper SMS [

48]. According to the findings, two-thirds of the seafarers surveyed openly admitted that they do not always comply with the procedures. The reasons given by respondents were that the procedures were either too complicated and/or not applicable in practice, that there were too many of them and/or that the company’s efficiency requirements influenced their decisions.

In addition, previous studies suggest that seafarers’ age is an important risk factor for shipboard accidents [

30,

49,

50,

51]. They also found that most accidents occurred during routine ship operations.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

As part of the study, it was necessary to assess the current situation in the shipping industry. In practice, ship officers are responsible for the conduct of ship operations and, as such, have the best insight into the advantages and disadvantages of the regulatory safety requirements and associated safety management systems that form the basis for this study. For this purpose, accredited maritime training institutions in Croatia were contacted and permissions were obtained to conduct the survey. The survey was conducted from June to September 2022. The research instrument was a questionnaire, which was in paper form. Respondents were introduced to the purpose of the survey, i.e., “what should be done” as per regulatory requirements and “how it is done in practice” as the end result. Participation was voluntary, provided the respondent had completed a period of service as an officer (deck/engine). In addition, the survey was anonymous and confidential to avoid biased participation. No incentives were offered, as this could result in speed runs of participants.

3.2. Survey Measures

The process of defining the measures of the questionnaire is crucial for ensuring content validity [

52]. Therefore, the content validity of the questionnaire statements used was confirmed, i.e., the items and scales were adopted from the literature [

21,

24,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. In accordance with the objectives of the study, the questionnaire consisted of three parts: the background of the respondents, regulatory requirements and the elements related to the barrier system of ship operation.

To determine the regulatory factors for shipboard safety, the requirements for functional safety management systems included in the regulatory requirements were examined [

5,

6,

7]. One of the requirements relates to the duty of companies to establish and facilitate effective communication on board. In addition, companies should ensure that crew members are prepared to respond to emergency situations. Companies should also develop and implement rules and procedures for the safe operation of ships. Previous studies have shown that work procedures and checklists are often poorly written. Therefore, it is necessary to gain insight into their quality and availability. According to the studies mentioned in the previous chapter, the shipboard management commitment to safety should be considered separately from organizational management commitment. In reviewing ship management commitment, the following issues were considered: ensuring that safety policies are effectively implemented and maintained, that the responsibilities and authority of personnel performing and supervising the work are defined, and that those performing their duties are supported at all times. A total of 21 statements were selected to provide insight into regulatory enforcement.

In order to investigate and determine the key elements related to the barrier system for ship operation, 12 statements were used. The focus of the statements used was on the perceived commitment of the shipboard safety officer(s), effective implementation and enforcement of safety policies and regulations, adequate familiarization with the ship’s systems, perception of economic/commercial pressures on the ship’s management structure, and respondents’ ability to deal with the hazards present. Based on the author’s expert opinion, two additional measures were included in the questionnaire: “I think that the Safety officer (e.g., Chief officer) is often in a conflict of interest between the deadlines set and the safety issues” and “I think it is better to delegate the safety supervision job to other officers (e.g., another deck officer/engineer) who are not in a conflict of interest”. The English language was used for all statements in the questionnaire.

All statements were rated on a five-point Likert scale (1: strongly disagree; 2: disagree; 3: neither; 4: agree; and 5: strongly agree) so that respondents could indicate their level of agreement. All statements were worded as neutrally as possible so as not to influence or bias participants’ responses. To facilitate the screening process, six statements were worded negatively.

3.3. Survey Sample

A total of 315 questionnaires were collected. All questionnaires collected were checked for inconsistencies in the responses. Response bias was found in 19 responses, i.e., respondents indicated the same level of agreement for all statements, so these were discarded and n=296 responses were accepted.

The seven questions of the questionnaire included background information: nationality, age, occupation, total time at sea, type of ship they worked on, company tenure, and a question about the ship’s flag (Croatian or foreign). All respondents indicated Croatian nationality and foreign ship flag. The majority of respondents (63.9%) reported being deck officers and 36.1% engineers. Regarding total time at sea, the largest percentage (32.8%) indicated: > 15 years, followed by ‘1-5 years’ (23.0%), ‘6-10 years’ (19.9%), ‘< 1 year’ (12.5%), and ‘11-15 years’ (11.8%). When asked what type of vessel they work on, the largest percentage (36.1%) indicated tankers (all types), container ships (23.0%), cruise ships (16.2%), bulk or general cargo ships (15.2%), and other types of ships (9.5%). Additional demographic variables can be found in

Table 1.

3.4. Data Analysis

All statements with negative wording were recoded; e.g., statements with a value of 1: strongly disagree were recoded to a value of 5: strongly agree. The next step was to examine the collected data for possible common method variance (CMV). Given the nature of the data and the need to explore it, i.e., define the underlying factor structure, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used along with principal component analysis (PCA) as the extraction method. Among the available rotation methods, Varimax rotation was chosen because it tends to preserve the ‘original factor structure’ and allows easier interpretation [

59]. Thus, to achieve the objectives of the study, two exploratory factor analyzes (EFA) were conducted for each set of statements. Factor loadings less than 0.6 were suppressed to ensure practical significance of the results [

60,

61]. Kaiser’s rule, eigenvalues greater than 1, was used as a threshold to determine an acceptable number of factors [

59]. The internal reliability of the factors was then tested using Cronbach’s alpha (>0.70) [

60]. In the next step, three models were constructed; the factors obtained from the first EFA were used as predictors in each model, and the factors obtained from the second EFA were used separately as dependent. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was then performed to assess the model fit and construct validity of each specified model, i.e., convergent and discriminant validity was confirmed. Factors were formed according to the EFA and CFA results using the sum (average) score method [

60,

62,

63]. The assumptions on which the multiple regression analysis was based were also tested. Finally, three hierarchical multiple regression analyzes were performed to examine the influence of maritime safety regulatory requirements as independent factors on the elements of the ship barrier system as dependent factors. The other exploratory variables (age, sea time, and tenure) were entered first, followed by the independent variables in successive steps. The programs IBM SPSS and AMOS 26.0 were used for all statistical analyzes.

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Variance

After data collection, data should be tested for common method variance (CMV). CMV can occur in cases where all variables, whether independent or not, are measured in the same survey using the same response method, and it is generally agreed that CMV can significantly affect study results and conclusions [

64,

65]. To test for CMV, the Harman single-factor test is recommended [

66]. The test requires that all study variables are included in the exploratory factor analysis and that the single factor extracted does not account for more than 50% of the explained variance. The result obtained shows that a single factor explains 35.7% of the variance between variables, therefore the CMV is acceptable.

4.2. Factor Analysis of Maritime Regulatory-Related Items

The obtained questionnaire data had to be further tested for their suitability for analysis. The initial tests, the Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2=4049.076, p<0.001) and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin’s (KMO) value of 0.907, showed that the items were appropriate for analysis [

60].

The EFA initially yielded a solution with four factors. At the same time, six items were found without loading. Therefore, the marked items were excluded and the analysis was performed again. The excluded items were “The company provides safety personnel with force required to do their jobs”; “Safety rules and procedures require a detailed work plan for each job”; “Safety rules and procedures require the use of personal protective equipment for each job individually”; “In our workplace, safety is the first priority in planning work tasks”; “Safety rules and procedures are prepared and ready for use”; and “The ship’s management while supervising the use of safety procedures uses praises for those who work safely”. The final EFA confirmed four factor solution, explaining a total of 73.6% of the variance. The remaining items are presented in

Table 2.

The six items relating to the quality of routine and safety communications between all parties involved in ship operations were included in the first factor. It was therefore referred to as communication. Four items related to the safety commitment of the ship management structure were included in the second factor, referred to as management commitment. Perceived quality of safety training and its outcomes were included in the third factor, referred to as safety training. Items related to the quality and applicability of safety procedures were included in the fourth factor, which is referred to as safety procedures.

4.3. Factor Analysis of Items Related to Barrier System for Ship Operation

The initial tests, Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2 =1395.1734, p<0.001) and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin’s (KMO) value of 0.835, indicated that the items were appropriate for analysis. The initial result revealed three factor solution. At the same time, one item was found without loading. Therefore, the flagged item was excluded and the analysis was repeated. The excluded item was: “The company expects from me to bend the safety rules, procedures, and instructions to get the job done”. Repeated analysis confirmed the three-component solution, first factor included six items, the second factor included three items, and two items were included in the third factor. However, when model validity was tested (see subsection 4.4.2.), it was found that the first factor caused problems with the discriminant validity of the model. Further analysis revealed that three items should be excluded from the first factor in order to maintain discriminant validity. The excluded items were:” My superior/safety officer closely explains the work plan and procedures before certain operation (e.g., mooring, unmooring)”; “The ship’s management ensures that we receive all the equipment needed to do the job safely”; and “Following the start of employment I was provided with all the necessary theoretical and practical knowledge in order to be able to follow the rules and procedures on board”.

After adjustment, the final EFA confirmed three factor solution, explaining a total of 72.7% of the variance (

Table 3).

The three items related to management/supervisor commitment to safety and their involvement in work practices and safety issues were included in the first factor. It was therefore referred to as shipboard work practices. The second factor included three items related to management’s safety and productivity practices on board and their response to perceived time or commercial pressures and was therefore referred to as risk management. Two items related to perceived preparedness for personal safety were included in the third factor and referred to as safety competence. It can be concluded that the identified factors correspond to the essential ships’ barrier systems.

4.4. Modeling Approach

Based on the analyzes conducted and the factors identified, three models were constructed: a) maritime regulatory factors and shipboard work practices; b) maritime regulatory factors and risk management; and c) maritime regulatory factors and safety competence, which meet the study aims.

4.4.1. Assessing Model’s Validity

CFA with maximum likelihood estimation was performed to assess model fit and construct validity of each specified model. To assess model fit, goodness-of-fit indices should include model chi-square (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) [

67]. A CFI ≥0.95, an SRMR≤ 0.08, and an RMSEA<0.08 values are indications of a good fit [

68]. To assess construct validity, convergent and discriminant validity should be examined. According to [

60], the following basic guidelines apply: standardized loading estimates should be 0.5 or higher; average variance extracted (AVE) should be 0.5 or higher to indicate sufficient convergent reliability; and to indicate sufficient internal consistency, composite reliability (CR) should be 0.7 or higher. To show discriminant validity, the square root of AVE should be greater than the correlations between constructs.

4.4.2. Model of Maritime Regulatory Factors and Shipboard Work Practices

The initial CFA results showed a good fit and the convergent validity of the model was confirmed. However, the discriminant validity of the model could not be demonstrated. The square root of AVE for communication, management commitment, and shipboard work practices was lower than the correlations between the constructs. Further analysis was conducted and it was concluded that three items should be excluded from shipboard work practices to achieve discriminant validity of the model (see subsection 4.3).

After adjustments, the CFA results again showed a good fit: χ2/df = 2.357, SRMR=0.043, CFI=0.947, and RMSA=0.068.

The construct validity results indicate that convergent validity of the model been confirmed: all standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.664 to 0.954, and the values of AVE and CR values were above the required values (

Table 4). In addition, the discriminant validity of the model was confirmed considering the calculated square roots of AVE (on the diagonal) and inter-construct correlations.

4.4.3. Model of Maritime Regulatory Factors and Risk Management

The CFA results showed that the model has a good fit: χ2/df =2.181, SRMR=0.041, CFI=0.950, and RMSA=0.063. Construct validity results indicate good convergent validity: all standardized factor loadings were between 0.644 and 0.957, and the values of CR were above the required level. The values of AVE were above the required level, except for risk management, which was at the 0.50 level. However, the CR for risk management was >0.6 (CR=0.747) and was used despite the marginal AVE [

69]. The discriminant validity of the model was also confirmed considering the calculated square roots of AVE (on the diagonal) and inter-construct correlations (

Table 5).

4.4.4. Model of Maritime Regulatory Factors and Safety Competence

The CFA results showed that the model has a good fit: χ2/df =2.363, SRMR=0.038, CFI=0.947, and RMSA=0.068. The construct validity results indicate good convergent validity: all standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.659 to 0.950, and the values AVE and CR were above the required values (

Table 6). The discriminant validity of the model was also confirmed: the square roots of AVE (on the diagonal) were larger than the inter construct correlations.

4.5. Regression Analyses

4.5.1. Testing the Assumptions

The assumptions for normally distributed residuals, homoscedasticity, linearity, and influential cases were checked using the histograms and normal probability plots (P-P) and plots of standardized residuals (ZRESID) versus standardized predicted values (ZPRED), showing that all assumptions were met. In addition, the assumption of no multicollinearity was verified by examining the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance values. The minimum tolerance values found in all analyzes were 0.267 and the maximum VIF value obtained was 3.739, indicating that there was no multicollinearity. The assumption of no influential cases was tested using the calculated Cook’s distance. The values in the analyzes ranged from 0.044 to 0.082, indicating that there are no influential cases. The test for homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test) was performed for the demographic variables (age, acquired sea time, and tenure) and the dependent variables. The results show that all p-values are significantly greater than 0.05. Therefore, it can be assumed that there is no significant variance between the groups.

4.5.2. Predicting Shipboard Work Practices

A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine the influence of respondent demographics and regulatory factors on shipboard work practices. The independent variables were introduced in steps, i.e., age, sea time, and tenure first, followed by other independent variables, with shipboard work practices as the dependent (

Table 7).

Table 7 presents three main findings. Perceived communication on board was the strongest predictor, followed by management commitment and safety training, all of which contributed positively, suggesting that better implementation of regulatory requirements should improve working practices on board. The Adjusted R2 in the last step shows that 51.4% of the variance in the dependent variable was explained by independent variables.

4.5.3. Predicting risk management

The results of the regression analysis predicting risk management are shown in

Table 8. The independent variables were introduced stepwise, with risk management as the dependent.

Table 8 presents three main findings. Perceived safety procedures were the strongest predictor of risk management, followed by the respondent’s sea time variable. Both variables contributed positively to the model, suggesting that the respondent’s experience at sea and adequate safety procedures should enhance the risk management process on board. Interestingly, the management commitment only contributes significantly after the introduction of safety procedures variable. The Adjusted R2 in the last step shows that 27.4% of the variance in the dependent variable was explained by independent variables.

4.5.4. Predicting Safety Competence

As in the above analyzes, the independent variables were introduced stepwise, with safety competence as the dependent (

Table 9).

Table 9 presents two main findings. Perceived safety training and sea time variables were the only statistically significant predictors of the model. Surprisingly, communication loses its significant contribution after the introduction of safety procedures in the last step. The Adjusted R2 in the last step shows that 21.6% of the variance in the dependent variable was explained by independent variables.

5. Discussion

Considering the study aims, it can be concluded that the objectives of the study have been achieved considering the identified factors. The empirical data used in this study shows the influence of maritime regulatory requirements and seafarers’ characteristics on the ship’s barrier system. Adequate communication, safety training, safety procedures and management commitment were identified as the most important objectives and correspond to the stated regulatory requirements (e.g., [

5,

6,

7,

9,

15,

16,

56,

70]). In addition, elements related to the barrier system for ship operations were identified in this study. According to the results of the study, these are shipboard work practices, risk management, and safety competence, which correspond to a ship barrier system consisting of elements that prevent, control and mitigate consequences.

Several important findings were made in this study that have theoretical and practical implications and further underscore the importance of the provisions contained in the current maritime regulations.

5.1. Implications of Regulatory Requirements on Shipboard Work Practices

The results of previous studies indicated poor communication as the main cause of poor safety performance, increased workplace hazards, and unsafe work (e.g., [

10,

71]). The result confirms previous findings that communication is the most important variable in predicting shipboard work practices (

Table 7). From a practical perspective, the ship’s crew should be a team, and there should be an open and constructive communication atmosphere so that all parties can discuss any work-related problems and find appropriate solutions [

56]. If communication is interrupted, it is likely that important messages will not be passed on to the last person acting, which may ultimately affect the work process. Such a scenario can also occur when the commitment of the ship management structure is low.

In addition to the mandatory requirements related to seafarer training, the provisions of ISM [

5] and chapters 6 and 8 of the MLC [

7] provide additional measures for specific safety training to prepare seafarers to work safely. Consistent with the intent of the requirements, safety training was found to be a significant predictor of the shipboard work practices model. The relationship was positive, suggesting that higher levels of shipboard safety training are associated with higher levels of shipboard work practices. In addition, the study results suggest that shipboard management commitment was a predictor of secondary importance in the model of shipboard work practices. The relationship was positive, suggesting that higher levels of shipboard management commitment were associated with higher levels of work practices. This result is consistent with previous findings and was expected.

According to stated regulations, safety procedures have the role of preventively ensuring safe work practices on board ships. Contrary to regulatory intentions, results of similar studies, and expectations, this result suggests that perceived safety procedures did not achieve their goal of establishing safe work practices and controlling seafarer behavior.

5.2. Implications of Regulatory Requirements on Risk Management

The results show that perceived safety procedures were the strongest predictor of the risk management model (

Table 8). The relationship was positive, suggesting that lower levels of inapplicability and/or quality are associated with better risk management. However, this result also points to the undesirable impact of safety procedures on the decision-making process; officers rely heavily on these procedures to manage risk. According to the literature and the authors’ expert opinion, these are sometimes poorly formulated and seafarers have to use their own discretion when making decisions. In addition, Doherty [

46] notes that relying solely on written rules and procedures is an undesirable strategy for controlling hazards; seafarers need to be able to accurately understand the author’s intentions. If management fails to properly communicate these intentions, the ship’s barrier system may break down. However, ISM mandates that the organization conduct internal safety audits to assess the effectiveness of the SMS, which is an additional safeguard.

Second, management commitment was found to be statistically important only when safety procedures were in place. This result also has an important practical implication. The purpose of the safety procedures contained in the SMS is to minimize the risks associated with ship operations. Therefore, officer commitment to safety, along with safety procedures, can be considered the last line of defense against undesirable outcomes associated with risk management. It should be noted, however, that to some degree there are efficiency requirements in the industry from management structures (ashore) that may impact onboard risk management, i.e., seafarers may be tempted to exceed safety limits (e.g., [

32,

70]). Interestingly, the regression coefficients for communication ceased to be significant after the introduction of other regulatory requirements. This result is difficult to explain. Under normal circumstances, officers work as a team and communication is an essential part of the decision-making process. One possible explanation could be the hierarchical structure of ship management, where the captain or department heads are responsible for certain operations, meaning that the final decision rests with them.

5.3. Implications of Regulatory Requirements on Safety Competence

A competent officer is essential to perform any operation, and proper training and experience should improve his or her skills [

72]. Consistent with previous findings, safety training was found to be a significant predictor of the safety competency model (

Table 9). The relationship was positive, suggesting that higher levels of shipboard safety training are associated with higher levels of officer competency. This result further emphasizes the importance of ISM and the MLC requirements. However, Stracke [

73] describes competence as “the ability that cannot be observed directly but only by activities to adequately and successfully combine and perform necessary activities in any context to achieve specific tasks or objectives”(p.35). Thus, it should be noted that officers are often under the influence of organizational factors (e.g., time/commercial pressures) that can affect their decision-making process and cause them to disregard their competence. On the other hand, individuals should be aware of the gaps in their competence and training should minimize the consequences [

74].

5.4. Implications of Seafarer’s Characteristics on Barrier System

In the literature, characteristics of seafarers such as age and sea service time are identified as risk factors that can have an impact on the safety of ship operations. According to the literature, there is relationship between age and compliance with safety regulations [

30,

51], safety awareness [

70] and accidents on board [

30,

49]. Similar studies found a relationship between sea service and compliance [

9], safe working skills and knowledge [

16], and safety awareness and risk acceptance [

70].

According to the results obtained, the age variable had no significant influence on the shipboard work practices model. However, it showed a positive influence on the risk management and safety competence models. After the introduction of other variables, the regression coefficients in both models decreased to non-significant, indicating full mediation. With regard to the sea service variable, the results show that the regression coefficients dropped to a lower significant level after the introduction of regulatory variables, indicating partial mediation in the models for risk management and safety competence.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

The limitations of the study should also be noted. First, only responses from officers/engineers on board were considered in this study. Therefore, the perceptions of lower ranking crew members are not known. Second, only officers with Croatian nationality were included in the study. However, the officers’ responses likely have some cross-cultural influence, as all of them reported working and living under a foreign ship’s flag. Studies that have addressed these issues have found cultural differences between nationalities (e.g., [

30]).

Furthermore, the influence of perceived safety procedures on shipboard work practices has been found to be insignificant, albeit statistically so. Possible explanations for this result may lie in numerous facts, such as the number of items used, their content, and/or the number of respondents included in the study. Therefore, this issue should be investigated in further research. Moreover, the presented models can be used in future studies independently of the industrial context by introducing additional statements and/or exploratory variables to further investigate the presented models.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a coherent approach to identify the regulatory safety requirements and associated barrier system for ship operations. It is recognized that a ship is a complex socio-technical system and that human and organizational factors are critical to the safe conduct of ship operations. The models presented can be used in daily ship operations, particularly for critical activities such as confined space entry, bunkering, electrical work, and/or “hot” work. Although the survey included responses from officers working in a broad shipping context and this could be considered a limitation of the study, it should be emphasized that both sets of factors are related to current maritime safety requirements and the ship’s barrier system, regardless of ship type. Although the results of the study show that regulatory safety requirements play an important role in maintaining ship safety, two findings stand out: shipping organizations should try to retain experienced officers and continue to work on the quality of safety rules and procedures and make them workable, otherwise negative consequences may occur. Throughout history, some of them have been devastating to people and the environment. Given current maritime safety requirements, statistical data on the number of accidents, and the findings of this study, the industry should consider developing additional safeguards for the safety of shipping operations.