1. Introduction

he erythropoietin-producing hepatocellular carcinoma (Eph) receptor family represents the largest group of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and plays crucial roles in embryonic development and tissue homeostasis [

1]. In the mammalian Eph receptor-ephrin system, five glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored ephrin ligands (ephrin-A1 to A5) and three transmembrane ligands (ephrin-B1 to B3) bind to corresponding Eph receptors (EphA1–A8, A10, and EphB1–B4, B6) [

2]. EphA receptors mainly bind to ephrin-As, while EphB receptors bind to ephrin-Bs, but EphA4 can interact with all ephrins [

1]. The transmembrane Eph ligands bind to Eph receptors on neighboring cells and stimulate the forward and reverse signaling through a cell–cell contact-dependent manner [

3]. Furthermore, soluble forms of ephrin-A ligands have been found in the culture supernatant of cancer cell lines. The soluble ephrin-A ligands are mainly produced by the metalloprotease-mediated proteolysis of membrane-anchored ephrin-A ligands, which mediates the autocrine activation of EphA signaling and cellular responses [

4,

5,

6,

7].

The expression of ephrins and Eph receptors is often increased or decreased in tumors compared to normal tissues [

1,

8]. Therefore, they have dual functions in promoting or suppressing tumors. In some tumors, Eph receptors are increased in the early stages but decreased during tumor progression, indicating that they could play different roles in tumor initiation and progression [

1]. EphA4 has been reported to be upregulated in various tumors including breast cancer [

9], glioma [

10], lung adenocarcinoma [

11], pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [

12], and gastric adenocarcinoma [

13].

EphA4 has been reported to be upregulated in breast cancer stem-like cells (CSCs), where EphA4-mediated signaling helps sustain the stem cell properties through interactions with tumor-associated macrophages [

14]. Furthermore, EphA4 promotes tumor cell migration, invasion, and neurotropism, which is a common pathological feature of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [

15]. Moreover, secretory ribonucleases (RNases) have revealed the significance of an unexpected ligand for EphA4. RNase 1 acts as a natively secretory ligand for EphA4 and promotes EphA4 signaling in an autocrine/paracrine manner, which leads to upregulation of CSC properties in breast cancer [

16]. Therefore, the EphA4 pathway has become a promising target for therapeutic intervention. For the neutralization and/or targeting of EphA4-positive tumors, the development of anti-EphA4 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) is essential. However, EphA4-targeting mAbs in clinical studies have not been reported.

The Cell-Based Immunization and Screening (CBIS) method is a strategy obtaining a variety of mAb against membrane proteins. In the CBIS method, antigen-overexpressed cells are immunized, and the hybridoma supernatants are subjected to flow cytometry-based high-throughput screening. We have developed various mAbs against receptor tyrosine kinases, such as Eph receptors [

17,

18,

19] and epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) [

20,

21,

22] using the CBIS method. These mAbs recognize diverse epitopes, including linear, conformational, and glycan-modified epitopes, and are suitable for use in flow cytometry. Furthermore, some of these mAbs can be used in western blotting and immunohistochemistry (IHC). This study employed the CBIS method to establish a highly versatile anti-EphA4 mAb.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Plasmids

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1, LN229 glioblastoma, P3X63Ag8U.1 (P3U1) myeloma, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Lung squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) LK-2 was obtained from the Cell Resource Center at Tohoku University (Miyagi, Japan). The complementary DNA of EphA4 (Catalog No.: RC211230, OriGene Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) plus an N-terminal MAP16 tag and an N-terminal PA16 tag were subcloned into a pCAG-Ble vector [FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Wako), Osaka, Japan]. Afterward, plasmids were transfected into CHO-K1 and LN229 cells using the Neon transfection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Stable transfectants [CHO/PA16-EphA4 (CHO/EphA4) and LN229/MAP16-EphA4] were subsequently selected by a cell sorter (SH800, Sony Corp., Tokyo, Japan) using an anti-MAP16 tag mAb (PMab-1) and an anti-PA16 tag mAb (NZ-1), respectively. After sorting, cultivation was conducted in a medium containing 0.5 mg/mL Zeocin (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA). Other Eph receptor-expressing CHO-K1 cells (e.g., CHO/EphA2) were established as previously reported [

17]. CHO-K1, P3U1, and Eph receptor-overexpressed CHO-K1 were cultured as described previously [

17].

2.2. Antibodies

An anti-EphA4 mAb (clone DMC472, rabbit-human Fc chimeric IgG

1) was purchased from DIMA BIOTECH (Wuhan, China). An anti-isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mAb (clone RcMab-1) [

23] and another anti-PA16 tag mAb, NZ-33 [

24] were reported previously. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-human IgG were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA) and Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), respectively. Secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and anti-rat IgG were obtained from Agilent Technologies Inc. (Santa Clara, CA, USA) and Sigma, respectively.

2.3. Hybridoma Production

Two 5-week-old female BALB/cAJcl mice (CLEA Japan, Tokyo, Japan) were intraperitoneally immunized with LN229/MAP16-EphA4 (1 × 10

8 cells/mouse) at 6 weeks of age. Alhydrogel adjuvant 2% (InvivoGen) was added to the immunogen cells in the first immunization. Three additional injections of LN229/MAP16-EphA4 (1 × 10

8 cells/mouse) were conducted intraperitoneally without the adjuvant every week. A last booster injection was also performed with 1 × 10

8 cells/mouse of LN229/MAP16-EphA4 two days before harvesting spleen cells from mice. The cell-fusion of P3U1 myeloma cells with the harvested splenocytes were described previously [

17]. On day 6 after cell fusion, the hybridoma supernatants were screened by flow cytometry using CHO/EphA4 and parental CHO-K1 cells. Anti-EphA4 mAbs were purified from the hybridoma supernatants using Ab-Capcher (ProteNova, Kagawa, Japan).

2.4. Production of Recombinant Antibodies

Variable (VH) and constant (CH) regions of heavy chain cDNAs of Ea4Mab-3 were subcloned into the pCAG-Neo vector (Wako). Variable (VL) and constant (CL) regions of light chain cDNAs of Ea4Mab-3 were subcloned into the pCAG-Ble vector (Wako). These vectors were transfected into ExpiCHO-S cells using the ExpiCHO Expression System (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). Ea4Mab-3 were purified using Ab-Capcher.

2.5. Flow Cytometry

Cells were harvested using 1 mM EDTA (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) and incubated with primary monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Subsequently, they were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse (diluted 1:2000) or FITC-conjugated anti-human IgG (diluted 1:2000) before fluorescence analysis using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer (Sony Corp.).

2.6. Determination of the Binding Affinity by Flow Cytometry

CHO/EphA4 and LK-2 were suspended in 100 μL serially diluted Ea

4Mab-3 or DMC472, after which Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (dilution rate; 1:200) or FITC-conjugated anti-human IgG (diluted 1:200) was treated. Fluorescence data were collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer. The dissociation constant (

KD) was determined as described previously [

19].

2.7. Western Blot Analysis

Western blotting was performed as described previously [

19].

2.8. Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) CHO/EphA4, CHO-K1, and LK-2 cell blocks were prepared using iPGell (Genostaff Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The FFPE cell sections were stained with Ea4Mab-3 (10 or 20 μg/mL) or NZ-33 (0.1 μg/mL) using BenchMark ULTRA PLUS with the OptiView DAB IHC Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

3. Results

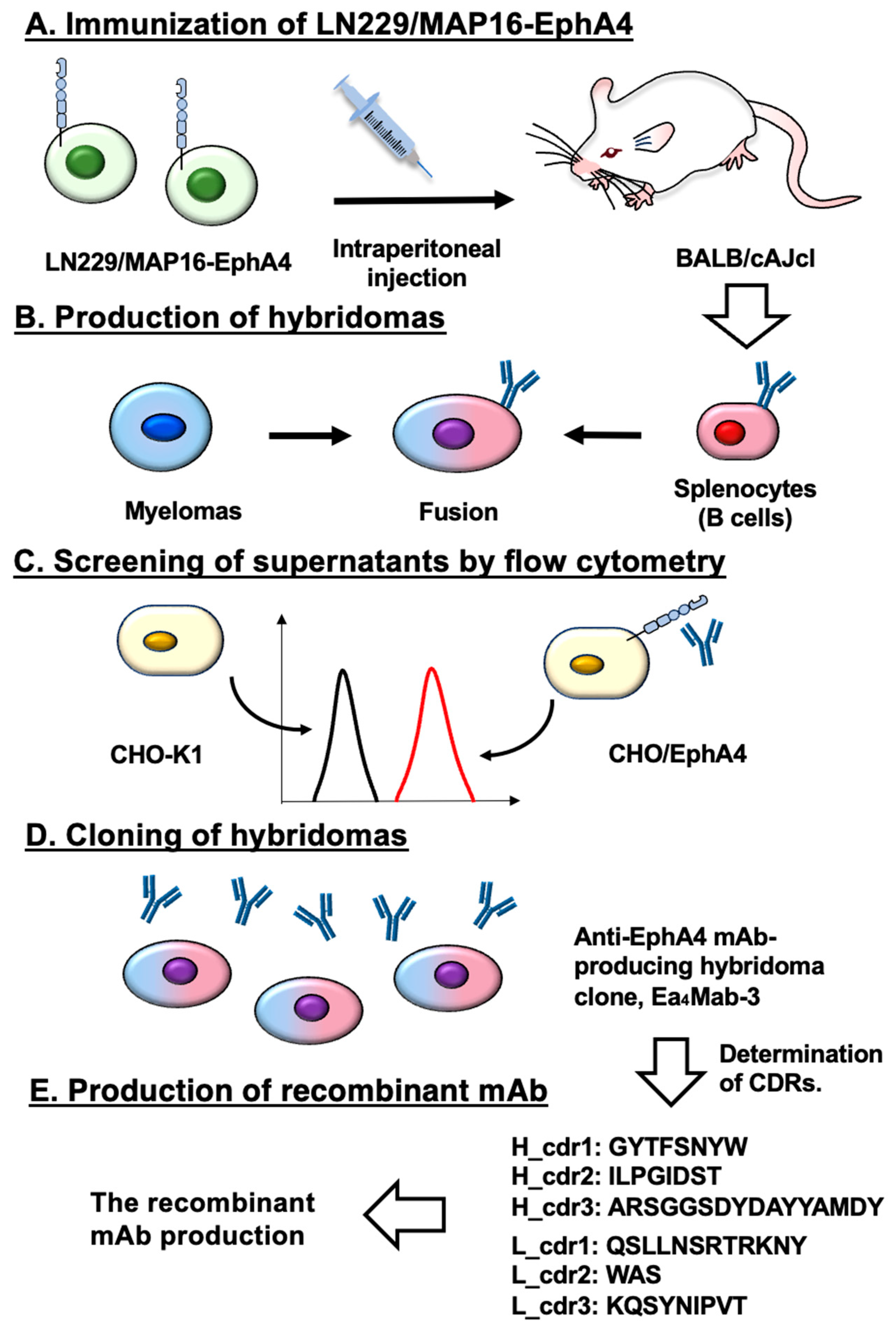

3.1. Development of an Anti-EphA4 mAb, Ea4Mab-3 Using the CBIS Method

To establish mAbs targeting EphA4, we employed the CBIS method using EphA4-overexpressed LN229 cells (

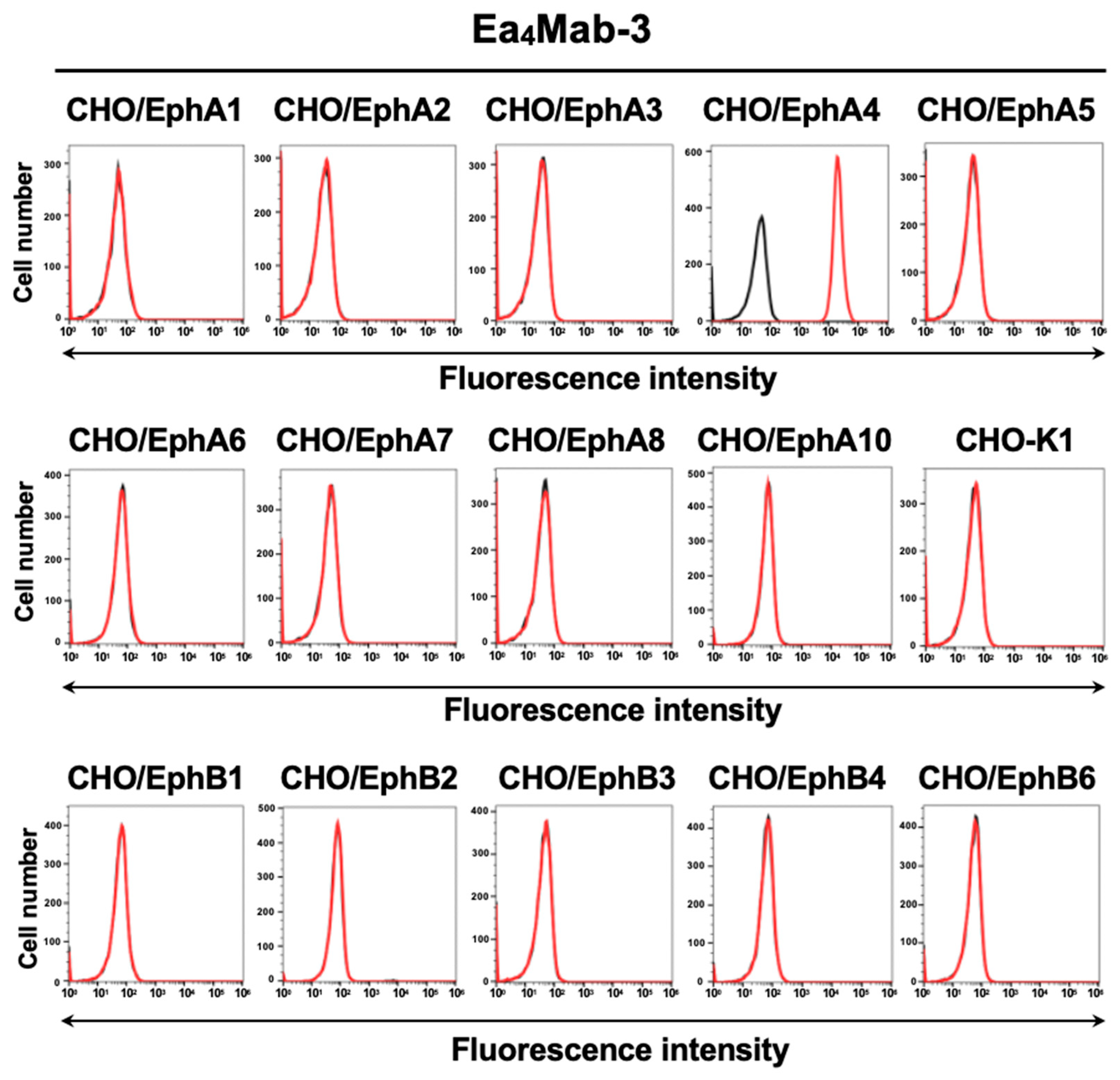

Figure 1). Two female BALB/cAJcl mice were immunized with LN229/MAP16-EphA4 5 times. Subsequently, splenocytes removed from immunized mice and fused with P3U1 cells. After confirming hybridoma formation, flow cytometric high throughput screening was conducted to select CHO/EphA4 reactive and parental CHO-K1 nonreactive supernatants of hybridomas. After limiting dilution and additional analysis, we established thirteen clones of anti-EphA4 mAbs. Among them, we selected a clone Ea

4Mab-3 (mouse IgG

1, kappa) by the reactivity and specificity. As shown in

Figure 2, Ea

4Mab-3 recognized CHO/EphA4. Importantly, Ea

4Mab-3 did not react with other Eph receptors (EphA1 to A3, A5, A6 to A8, A10, B1 to B4, and B6)-overexpressed CHO-K1. This result indicates that Ea

4Mab-3 is an EphA4 specific mAb.

3.2. Investigation of the Reactivity of Ea4Mab-3 Using Flow Cytometry

We cloned the cDNAs of the V

H and V

L regions of Ea

4Mab-3 and produced recombinant Ea

4Mab-3 for further validation (

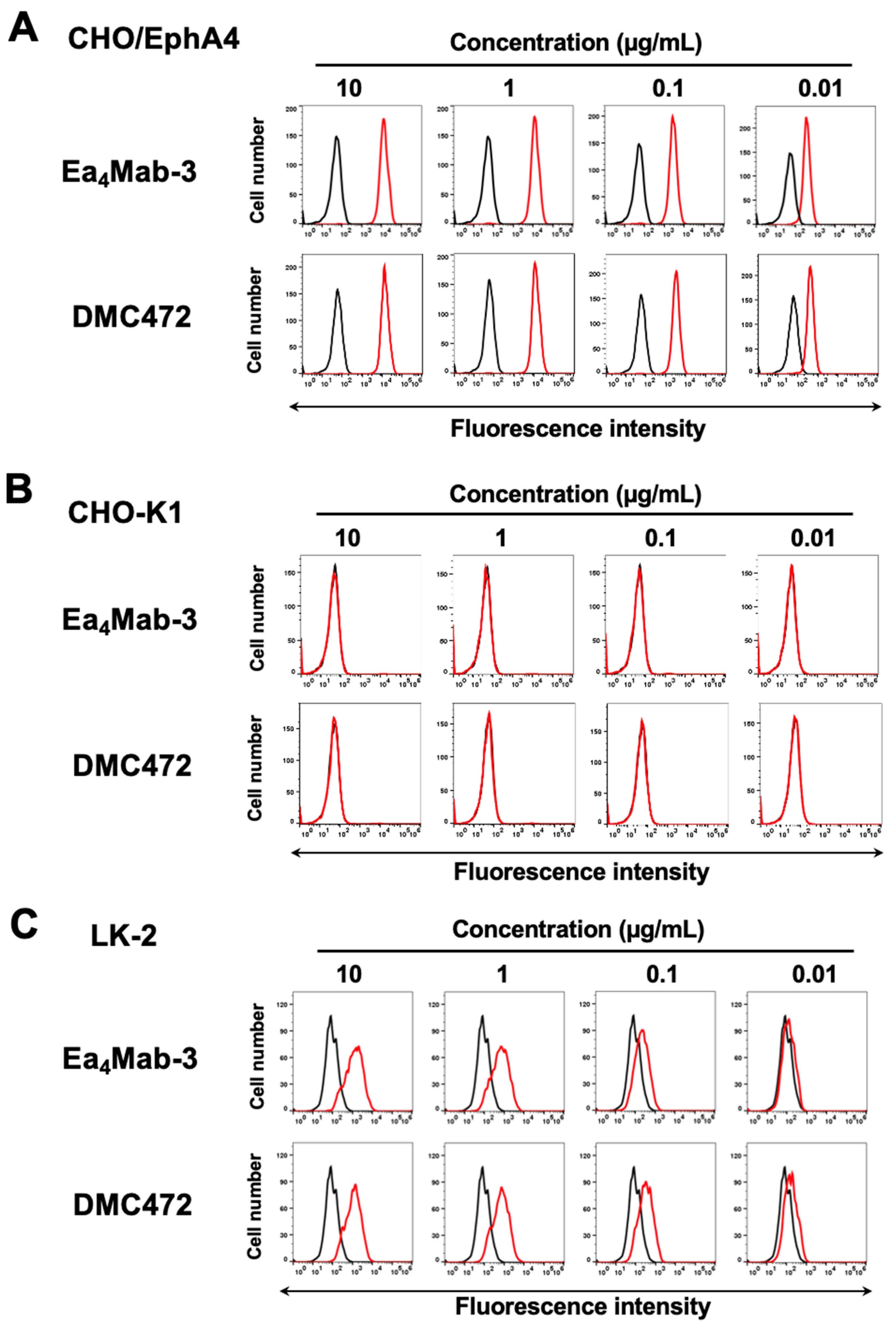

Figure 1E). We first assessed the reactivity of Ea

4Mab-3 using flow cytometric analysis. Results showed that Ea

4Mab-3 recognized CHO/EphA4 dose-dependently (

Figure 3A). Ea

4Mab-3 did not react with parental CHO-K1 cells (

Figure 3B). Furthermore, Ea

4Mab-3 exhibited a dose-dependent reaction to lung SCC LK-2 cells (

Figure 3C). A commercially available anti-EphA4 mAb (clone DMC472, rabbit-human Fc chimeric IgG

1) showed similar reactivity compared to that of Ea

4Mab-3 (

Figure 3). These results indicate that Ea

4Mab-3 can detect endogenous and exogenous EphA4 in flow cytometry.

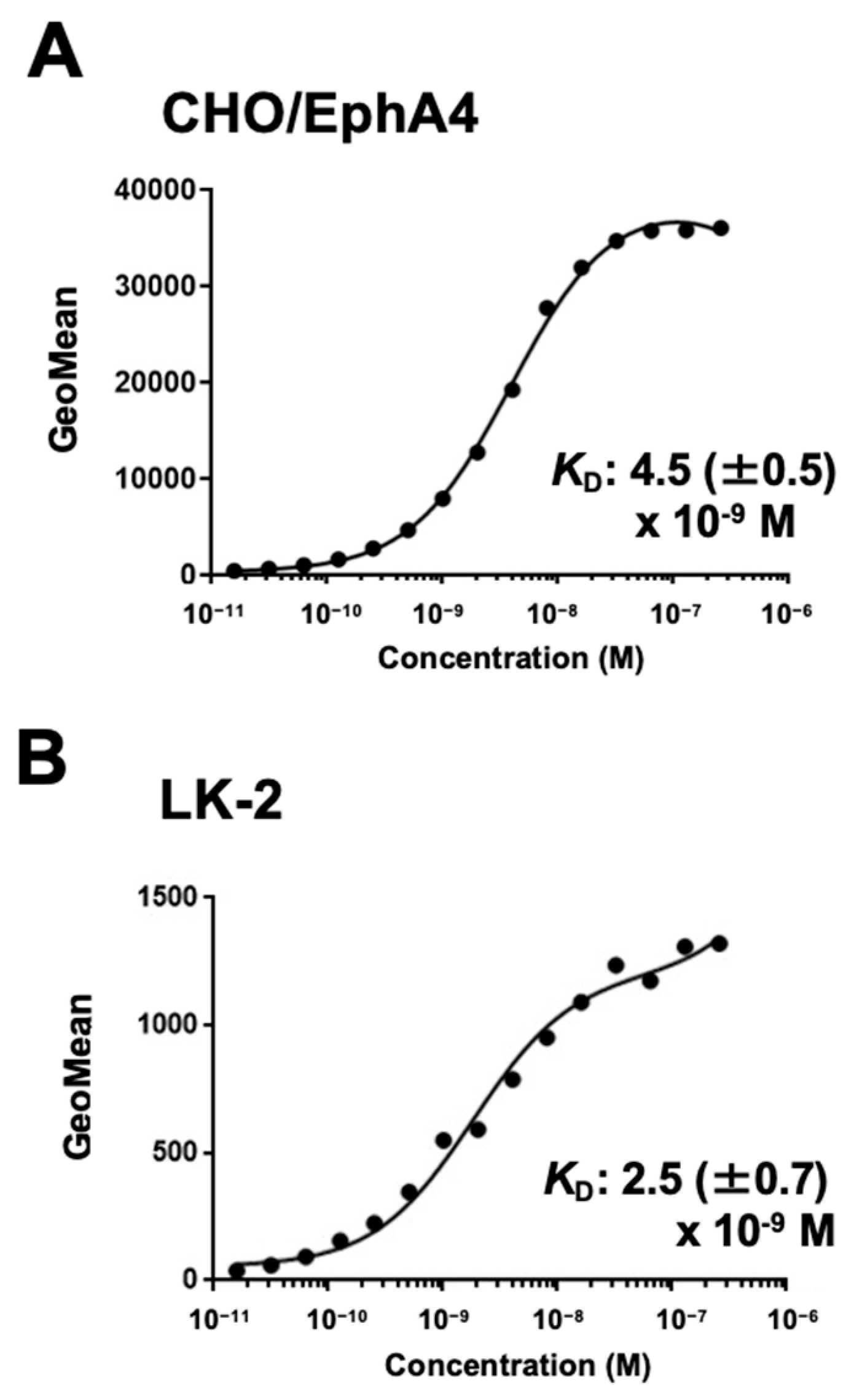

3.3. Determination of the Binding Affinity of Ea4Mab-3 Using Flow Cytometry

To evaluate the binding affinity of Ea

4Mab-3, flow cytometry was performed using CHO/EphA4 and LK-2 cells. The

KD values of Ea

4Mab-3 for CHO/EphA4 and LK-2 were 4.5 (± 0.5) ×10

-9 M and 2.5 (± 0.7) ×10

-9 M, respectively (

Figure 4). Because we could not obtain the exact molecular wight of DMC472 (rabbit-human Fc chimeric IgG

1), supplementary

Figure 1 showed the reference

KD values of DMC472 with considered it as a standard human IgG

1. These results demonstrate that Ea

4Mab-3 has high affinity to EphA4-positive cells.

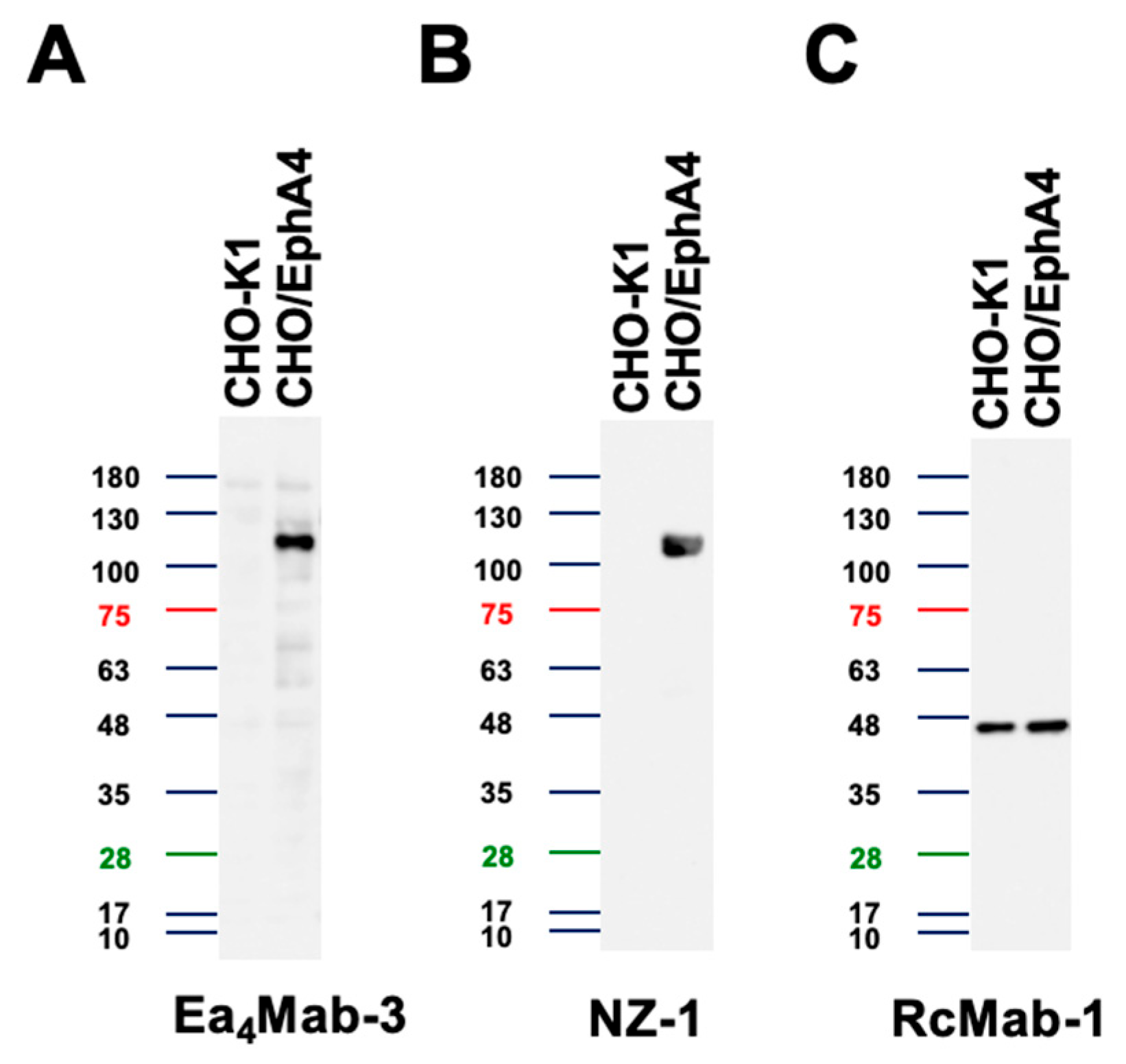

3.4. Western Blotting Using Ea4Mab-3

We examined whether Ea

4Mab-3 can be used for western blotting using cell lysates from CHO-K1 and CHO/EphA4. As shown in

Figure 5, Ea

4Mab-3 could clearly detect exogenously overexpressed-EphA4 as the band around 110 kDa in CHO/EphA4 cell lysates, while no band was detected in parental CHO-K1 cells. An anti-PA16 tag mAb NZ-1 was used as a positive control and could also detect a band at the same position in CHO/EphA4 cell lysates. An anti-IDH1 mAb (clone RcMab-1) was used for internal control. These results demonstrate that Ea

4Mab-3 can detect EphA4 in western blotting.

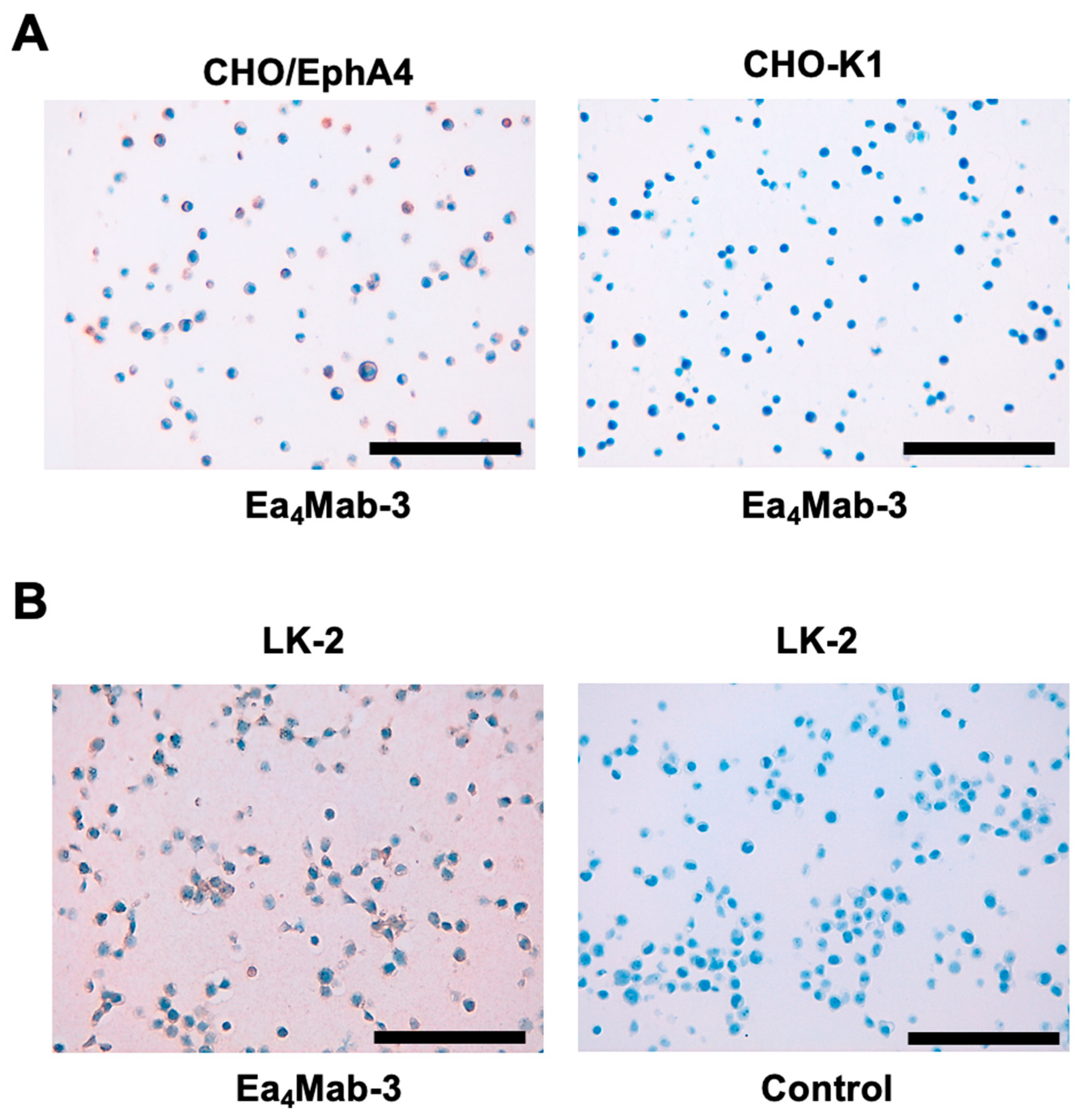

3.5. Immunohistochemistry Using Ea4Mab-3

To evaluate whether Ea

4Mab-3 can be used for IHC, FFPE CHO-K1 and CHO/EphA4 sections were stained with Ea

4Mab-3. A membranous staining by Ea

4Mab-3 was observed in CHO/EphA4 and LK-2 cells (

Figure 6). An anti-PA16 tag mAb, NZ-33 showed potent reactivity to CHO/EphA4 (supplementary

Figure 2). These results indicate that Ea

4Mab-3 applies to IHC for detecting EphA4-positive cells in FFPE cell samples.

4. Discussion

This study developed and characterized a novel anti-human EphA4 mAb, Ea

4Mab-3, which is suitable for versatile applications. Ea

4Mab-3 recognizes exogenous EphA4 and endogenous EphA4 in lung SCC LK-2 by flow cytometry (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Ea

4Mab-3 did not recognize other Eph receptor-overexpressed CHO-K1 (

Figure 2). Furthermore, Ea

4Mab-3 can detect EphA4 in western blotting (

Figure 5) and IHC (

Figure 6). Because a commercially available anti-EphA4 mAb (DMC472) is rabbit-human Fc chimeric IgG

1 and applicable to only flow cytometry, Ea

4Mab-3 would contribute to the basic research to investigate the molecular functions of EphA4 in multiple applications. We also examined the application of other twelve clones and the information has been updated at “Antibody bank” (

http://www.med-tohoku-antibody.com/topics/001_paper_antibody_PDIS.htm#EphA4).

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) constituting most cases [

25]. Currently, molecularly targeted therapy represents a principal treatment strategy for NSCLC, particularly in patients harboring mutations in EGFR, KRAS

G12C, or other well-established oncogenic drivers [

26]. For instance, administration of third-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as osimertinib, has been reported to achieve response rates exceeding 65% in patients with sensitizing EGFR mutations [

27]. Furthermore, the KRAS

G12C inhibitors sotorasib and adagrasib have demonstrated significant survival benefits in this patient population [

28,

29].

Nevertheless, 35–50% of NSCLC patients do not have mutations or rearrangements in tyrosine kinases and therefore do not receive clinical benefit from those current therapies [

26,

30]. Consequently, the identification of novel oncogenic drivers and the development of therapeutic strategies are essential for improving the overall prognosis for NSCLC patients. Recent studies have identified potential oncogenic drivers that may represent novel therapeutic targets. Among these, several members of the secretory RNase family have been shown to directly interact with specific RTKs, thereby constitutively activating their oncogenic signaling cascades and promoting tumor progression. For instance, RNase1 interacts with EphA4 in breast cancer [

16] and wild type anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) in NSCLC [

31]. RNase1 can transduce oncogenic EphA4 and ALK signaling through the interactions [

16,

31]. Furthermore, RNase5 binds to EGFR in pancreatic cancer [

32], RNase4 with anexelekto (AXL) in prostate cancer [

33], and RNase7 binds to ROS1 in liver cancer [

34]. We found the expression of EphA4 in LK-2 derived from lung SCC, a type of NSCLC (

Figure 3,

Figure 4, and

Figure 6). It is worthwhile to examine the distribution of EphA4 and ALK receptors and clarify the potential for target in the treatment of NSCLC.

EphA4 exceptionally interacts with all ephrins through its N-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD) [

1]. RNase 1 also binds to EphA4 LBD through its C-terminus [

16,

35]. Therefore, mAbs that recognize EphA4 LBD have potential for neutralization of both ephrins and RNase 1. The epitope analysis and the neutralization activity of Ea

4Mab-3 or other clones should be clarified in the future. We have determined the epitope of various transmembrane (TM) receptors such as EGFR (single TM [

36]), CD39 (2TM [

37]), CD20 (4 TM [

38]), and CCR8 (7 TM [

39]).

Anti-Eph receptors mAbs that activate or inhibit forward signaling and trigger antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) have been developed. DS-8895a is an anti-EphA2 mAb engineered to lack fucose in the constant fragment region to promote ADCC [

40]. A phase 1 safety and bioimaging trial of DS-8895a in advanced or metastatic EphA2-positive tumors revealed that the best response was stable disease at doses evaluated and low tumor uptake of DS-8895a. Further development of DS-8895a was halted due to the biodistribution data [

41]. Ifabotuzumab, a humanized EphA3 agonistic antibody with ADCC activity, was developed to target haematological malignancies and glioblastoma with some encouraging pre-clinical [

42,

43] and clinical responses [

1]. However, EphA4-targeting mAbs in clinical studies have not been reported. We previously converted the isotype of mAbs into mouse IgG

2a or human IgG

1 to confer the ADCC activity. These mAbs are used for the evaluation of antitumor activities in mouse xenograft models [

44,

45]. We already identified the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) of Ea

4Mab-3 (

Figure 1E). A class-switched Ea

4Mab-3 will be useful in investigating the antitumor activities in NSCLC xenograft models.

Author Contributions

Ayano Saga: Investigation, Guanjie Li: Investigation, Tomohiro Tanaka: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Mika K. Kaneko: Conceptualization, Hiroyuki Suzuki: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Yukinari Kato: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review and editing

Funding

This research was supported in part by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Numbers: JP25am0521010 (to Y.K.), JP25ama121008 (to Y.K.), JP25ama221339 (to Y.K.), and JP25bm1123027 (to Y.K.), and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) grant nos. 24K18268 (to T.T.) and 25K10553 (to Y.K.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Tohoku University (Permit number: 2022MdA-001) for studies involving animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All related data and methods are presented in this paper. Additional inquiries should be addressed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest involving this article.

References

- Pasquale, E.B. Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2024;24(1): 5-27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquale, E.B. Eph receptor signaling complexes in the plasma membrane. Trends Biochem Sci 2024;49(12): 1079-1096. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisabeth, E.M.; Falivelli, G.; Pasquale, E.B. Eph receptor signaling and ephrins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2013;5(9). [CrossRef]

- Alford, S.C.; Bazowski, J.; Lorimer, H.; Elowe, S.; Howard, P.L. Tissue transglutaminase clusters soluble A-type ephrins into functionally active high molecular weight oligomers. Exp Cell Res 2007;313(20): 4170-4179. [CrossRef]

- Wykosky, J.; Palma, E.; Gibo, D.M.; et al. Soluble monomeric EphrinA1 is released from tumor cells and is a functional ligand for the EphA2 receptor. Oncogene 2008;27(58): 7260-7273. [CrossRef]

- Alford, S.; Watson-Hurthig, A.; Scott, N.; et al. Soluble ephrin a1 is necessary for the growth of HeLa and SK-BR3 cells. Cancer Cell Int 2010;10: 41. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhao, X.P.; Song, K.; Shang, Z.J. Ephrin-A1 is up-regulated by hypoxia in cancer cells and promotes angiogenesis of HUVECs through a coordinated cross-talk with eNOS. PLoS One 2013;8(9): e74464. [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Scott, A.M.; Janes, P.W. Eph Receptors in Cancer. Biomedicines 2023;11(2). [CrossRef]

- Brantley-Sieders, D.M.; Jiang, A.; Sarma, K.; et al. Eph/ephrin profiling in human breast cancer reveals significant associations between expression level and clinical outcome. PLoS One 2011;6(9): e24426. [CrossRef]

- Fukai, J.; Yokote, H.; Yamanaka, R.; et al. EphA4 promotes cell proliferation and migration through a novel EphA4-FGFR1 signaling pathway in the human glioma U251 cell line. Mol Cancer Ther 2008;7(9): 2768-2778. [CrossRef]

- Saintigny, P.; Peng, S.; Zhang, L.; et al. Global evaluation of Eph receptors and ephrins in lung adenocarcinomas identifies EphA4 as an inhibitor of cell migration and invasion. Mol Cancer Ther 2012;11(9): 2021-2032. [CrossRef]

- Iiizumi, M.; Hosokawa, M.; Takehara, A.; et al. EphA4 receptor, overexpressed in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, promotes cancer cell growth. Cancer Sci 2006;97(11): 1211-1216. [CrossRef]

- Oki, M.; Yamamoto, H.; Taniguchi, H.; et al. Overexpression of the receptor tyrosine kinase EphA4 in human gastric cancers. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14(37): 5650-5656. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Clauser, K.R.; Tam, W.L.; et al. A breast cancer stem cell niche supported by juxtacrine signalling from monocytes and macrophages. Nat Cell Biol 2014;16(11): 1105-1117. [CrossRef]

- Furuhashi, S.; Morita, Y.; Ida, S.; et al. Ephrin Receptor A4 Expression Enhances Migration, Invasion and Neurotropism in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Cells. Anticancer Res 2021;41(4): 1733-1744. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.; Wang, Y.N.; Yang, W.H.; et al. Human ribonuclease 1 serves as a secretory ligand of ephrin A4 receptor and induces breast tumor initiation. Nat Commun 2021;12(1): 2788. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubukata, R.; Suzuki, H.; Hirose, M.; et al. Establishment of a highly sensitive and specific anti-EphB2 monoclonal antibody (Eb2Mab-12) for flow cytometry. MI 2025. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; et al. Development of a novel anti-erythropoietin-producing hepatocellular receptor B6 monoclonal antibody Eb(6)Mab-3 for flow cytometry. Biochem Biophys Rep 2025;41: 101960. [CrossRef]

- Satofuka, H.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; et al. Development of an anti-human EphA2 monoclonal antibody Ea2Mab-7 for multiple applications. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2025;42: 101998. [CrossRef]

- Asano, T.; Ohishi, T.; Takei, J.; et al. Anti-HER3 monoclonal antibody exerts antitumor activity in a mouse model of colorectal adenocarcinoma. Oncol Rep 2021;46(2). [CrossRef]

- Itai, S.; Yamada, S.; Kaneko, M.K.; et al. Establishment of EMab-134, a Sensitive and Specific Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibody for Detecting Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells of the Oral Cavity. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2017;36(6): 272-281. [CrossRef]

- Itai, S.; Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; et al. H(2)Mab-77 is a Sensitive and Specific Anti-HER2 Monoclonal Antibody Against Breast Cancer. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2017;36(4): 143-148. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikota, H.; Nobusawa, S.; Arai, H.; et al. Evaluation of IDH1 status in diffusely infiltrating gliomas by immunohistochemistry using anti-mutant and wild type IDH1 antibodies. Brain Tumor Pathol 2015;32(4): 237-244. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujisawa, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Tanaka, T.; et al. Development and Characterization of Ea7Mab-10: A Novel Monoclonal Antibody Targeting EphA7. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin 2025;75(1): 10-45. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Herbst, R.S.; Boshoff, C. Toward personalized treatment approaches for non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med 2021;27(8): 1345-1356. [CrossRef]

- Soria, J.C.; Ohe, Y.; Vansteenkiste, J.; et al. Osimertinib in Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;378(2): 113-125. [CrossRef]

- de Langen, A.J.; Johnson, M.L.; Mazieres, J.; et al. Sotorasib versus docetaxel for previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer with KRAS(G12C) mutation: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2023;401(10378): 733-746. [CrossRef]

- Jänne, P.A.; Riely, G.J.; Gadgeel, S.M.; et al. Adagrasib in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring a KRAS(G12C) Mutation. N Engl J Med 2022;387(2): 120-131. [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.C.; Tan, D.S.W. Targeted Therapies for Lung Cancer Patients With Oncogenic Driver Molecular Alterations. J Clin Oncol 2022;40(6): 611-625. [CrossRef]

- Zha, Z.; Liu, C.; Yan, M.; et al. RNase1-driven ALK-activation is an oncogenic driver and therapeutic target in non-small cell lung cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2025;10(1): 124. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.N.; Lee, H.H.; Chou, C.K.; et al. Angiogenin/Ribonuclease 5 Is an EGFR Ligand and a Serum Biomarker for Erlotinib Sensitivity in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018;33(4): 752-769.e758. [CrossRef]

- Vanli, N.; Sheng, J.; Li, S.; Xu, Z.; Hu, G.F. Ribonuclease 4 is associated with aggressiveness and progression of prostate cancer. Commun Biol 2022;5(1): 625. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zha, Z.; Zhou, C.; et al. Ribonuclease 7-driven activation of ROS1 is a potential therapeutic target in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2021;74(4): 907-918. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Yamaguchi, H.; Liu, Y.Y.; et al. Structural insights into EphA4 unconventional activation from prediction of the EphA4 and its complex with ribonuclease 1. Am J Cancer Res 2022;12(10): 4865-4878.

- Kaneko, M.K.; Yamada, S.; Itai, S.; et al. Elucidation of the critical epitope of an anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody EMab-134. Biochem Biophys Rep 2018;14: 54-57. [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Epitope Mapping of an Anti-Mouse CD39 Monoclonal Antibody Using PA Scanning and RIEDL Scanning. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2024;43(2): 44-52. [CrossRef]

- Asano, T.; Takei, J.; Furusawa, Y.; et al. Epitope Mapping of an Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibody (C(20)Mab-60) Using the HisMAP Method. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2021;40(6): 243-249. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, H.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Epitope Mapping of an Anti-Mouse CCR8 Monoclonal Antibody C(8)Mab-2 Using Flow Cytometry. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2024;43(4): 101-107. [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, J.; Sue, M.; Yamato, M.; et al. Novel anti-EPHA2 antibody, DS-8895a for cancer treatment. Cancer Biol Ther 2016;17(11): 1158-1167. [CrossRef]

- Gan, H.K.; Parakh, S.; Lee, F.T.; et al. A phase 1 safety and bioimaging trial of antibody DS-8895a against EphA2 in patients with advanced or metastatic EphA2 positive cancers. Invest New Drugs 2022;40(4): 747-755. [CrossRef]

- Offenhäuser, C.; Al-Ejeh, F.; Puttick, S.; et al. EphA3 Pay-Loaded Antibody Therapeutics for the Treatment of Glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel) 2018;10(12). [CrossRef]

- Day, B.W.; Stringer, B.W.; Al-Ejeh, F.; et al. EphA3 maintains tumorigenicity and is a therapeutic target in glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer Cell 2013;23(2): 238-248. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Anti-HER2 Cancer-Specific mAb, H(2)Mab-250-hG(1), Possesses Higher Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity than Trastuzumab. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25(15). [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; et al. A Cancer-Specific Monoclonal Antibody against HER2 Exerts Antitumor Activities in Human Breast Cancer Xenograft Models. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25(3). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).