Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. A Priori Regulation

1.2. Energy Allocation

1.3. Main Contributions

- A complete assessment is developed, drawing global conclusions which are vital as a source of advice to prevent common failures.

- Even though RECs are at a stage of deployment, meaning that there are few RECs in operation with accessible data, we recreate 240 realistic REC scenarios with different configurations.

- The scenarios were designed to accurately represent real consumption patterns by utilising clustering techniques on a real data set.

- The method is replicable in countries where the legal framework establishes that the distribution of RES generation must be based on allocation coefficients (such as the Spanish and French legal frameworks).

- The study is developed with a prosumer-driven perspective, instead of the typical DSO’s point of view. Providing vital information for consumers eager to form a REC and inform their decision-making.

2. Methodology

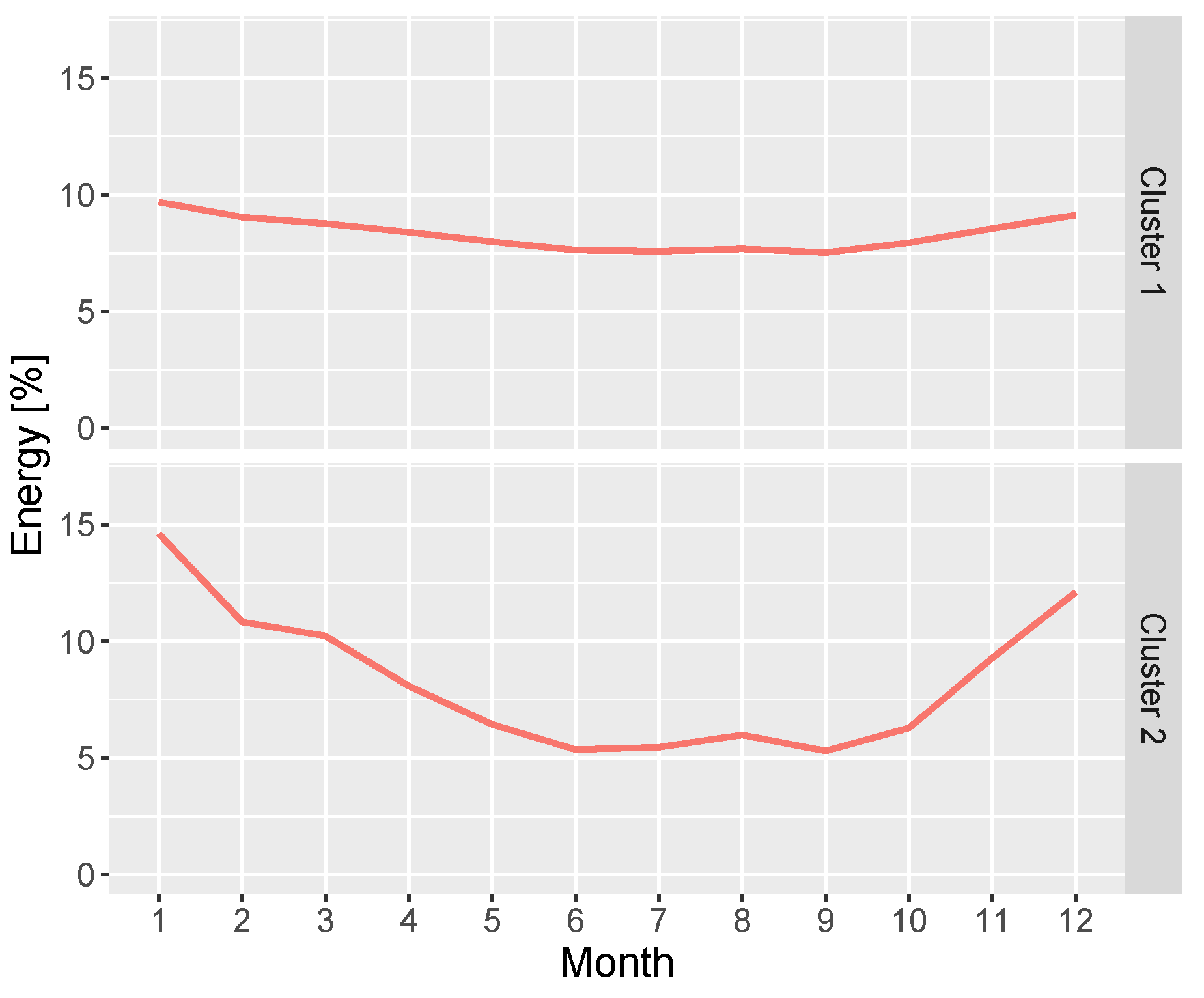

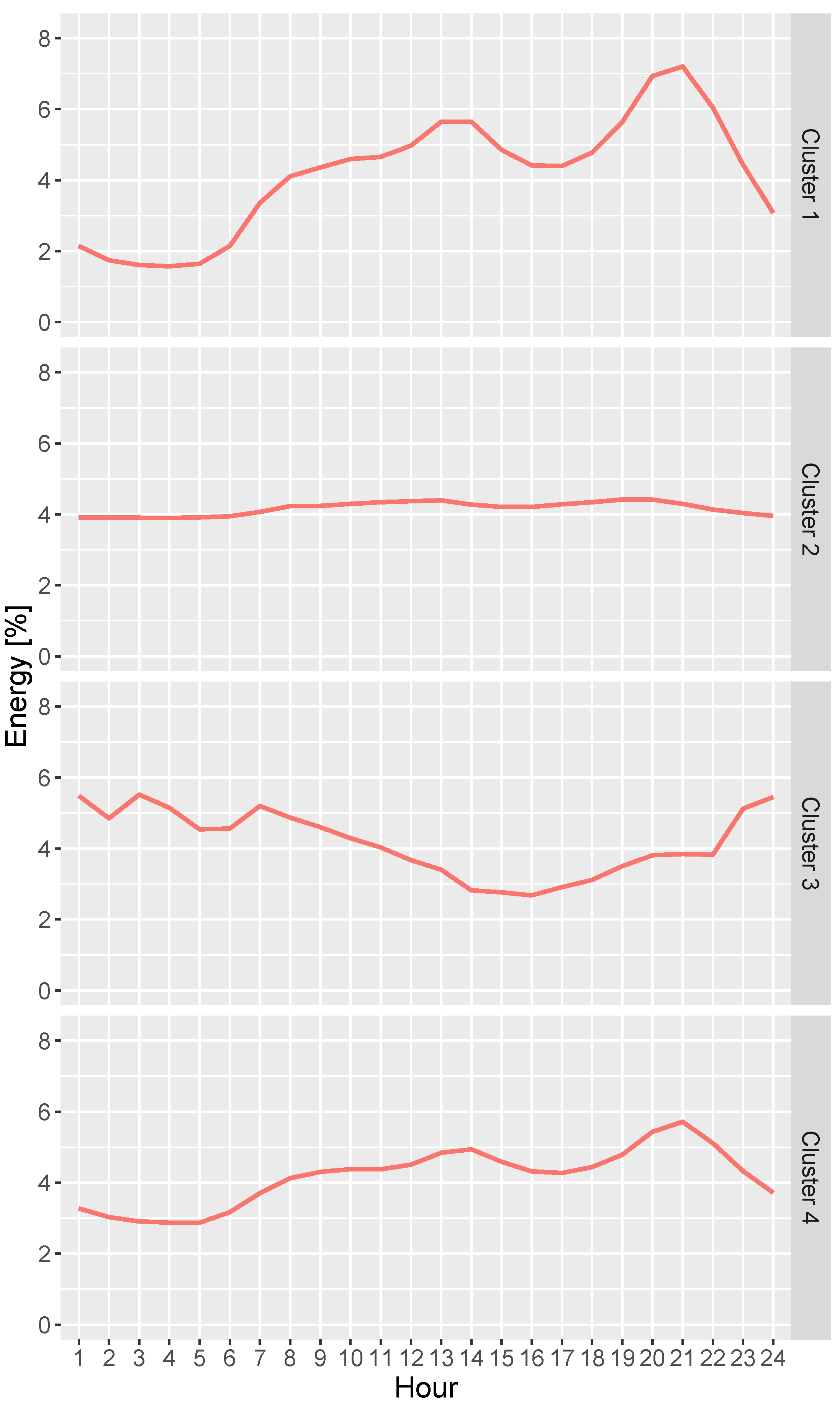

2.1. Clustering

2.2. Configuration Scenarios Design

- Aggregated consumption: annual accumulated electricity consumption.

- Shape:made by daily and seasonal consumption patterns.

- Prices:

- Two prices are assigned to every participant for the energy: purchase price of the electricity delivered by the power grid, and sale price of the solar surplus dispatched to the power grid. The ratio between these two prices was always set to , with always the largest. The values for varied randomly among participants, ranging from 0.20 to 0.28. This study focused on the relationship between prices among participants: similar prices indicate that all participants have the same tariffs, while different prices indicate that all participants have different tariffs.

- Compensation:

- The possibilities are to operate with or without a compensation mechanism. All participants in the Renewable Energy Community (REC) must use the same compensation method. According to the Spanish regulation, it is not permitted for one participant to use compensation while another does not.

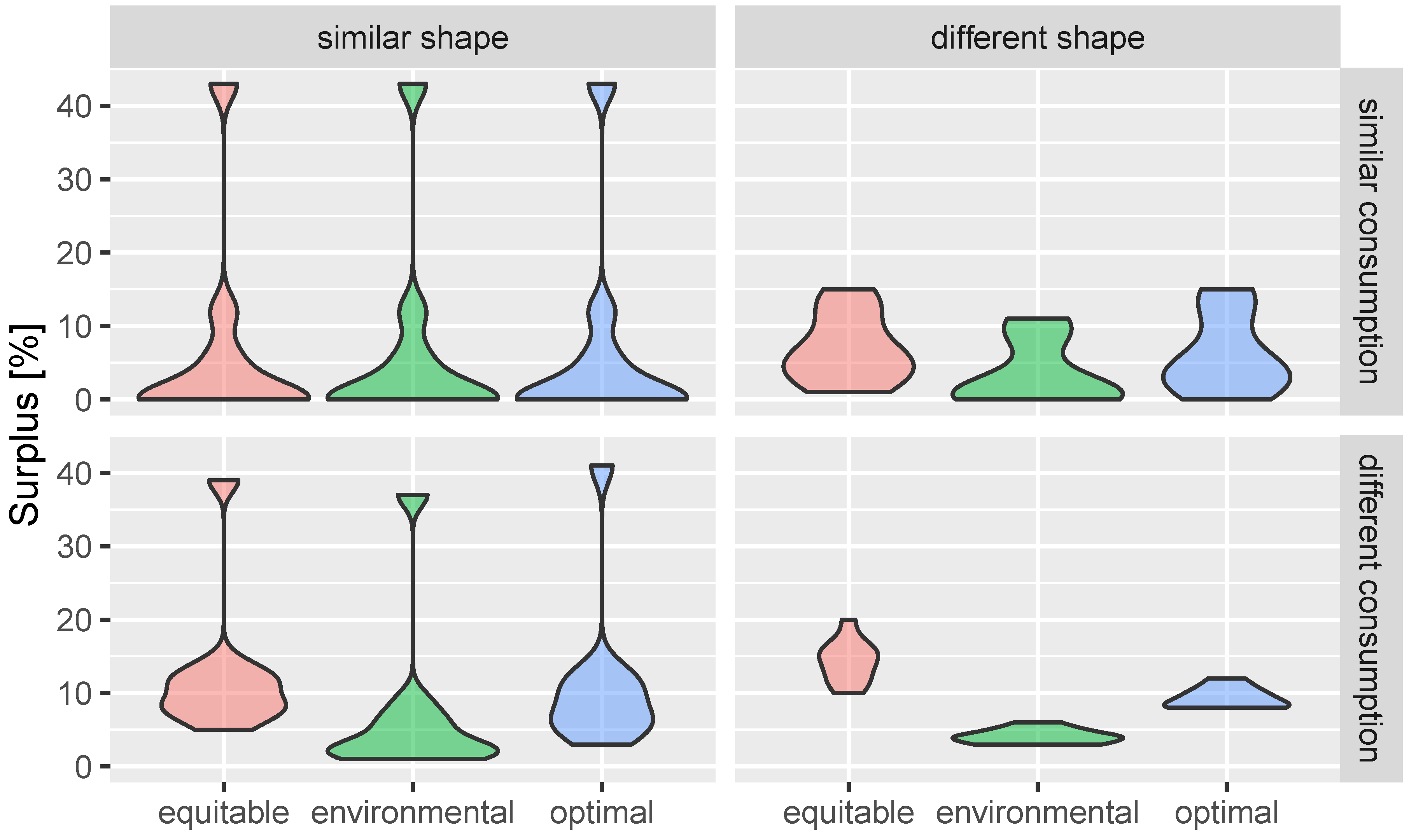

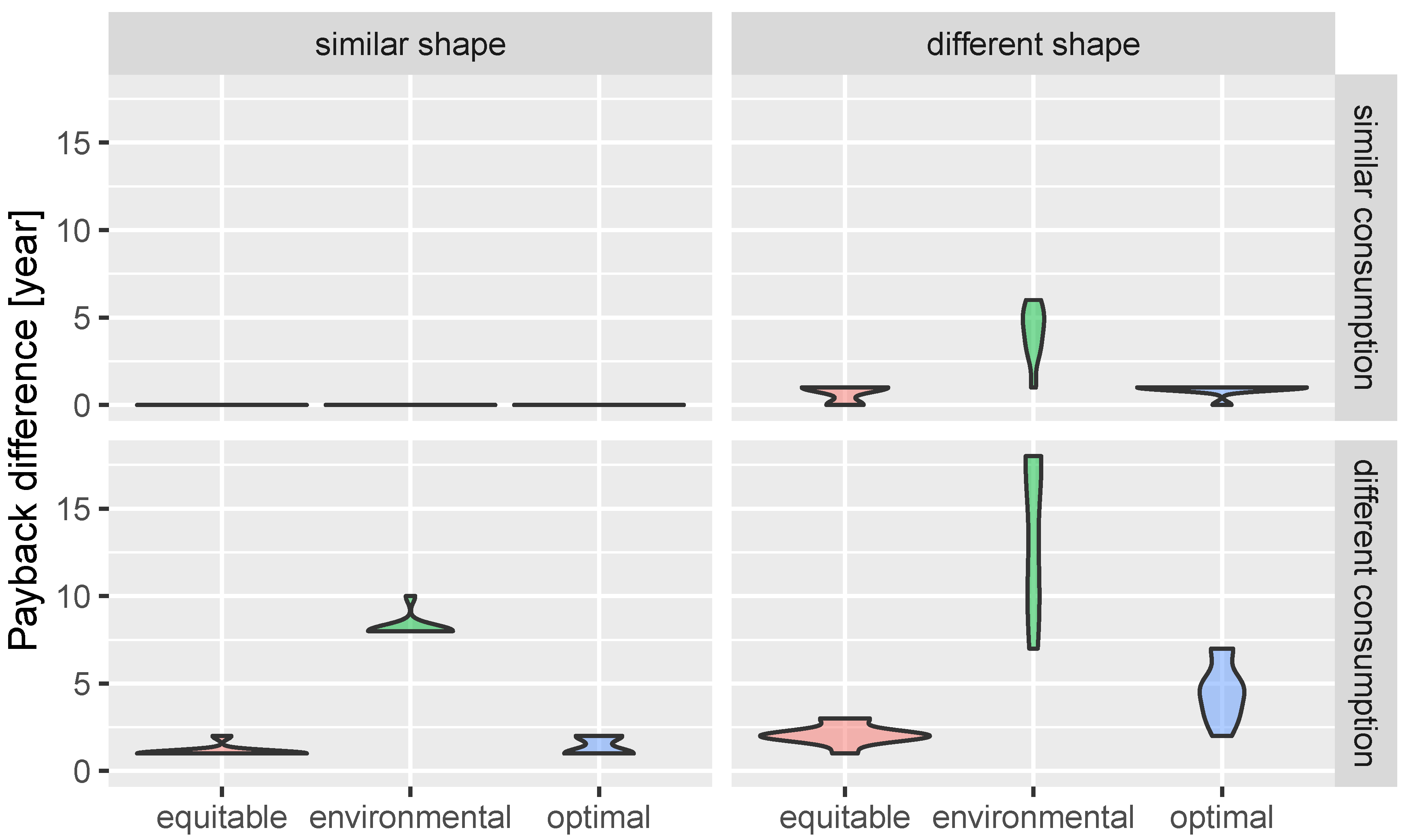

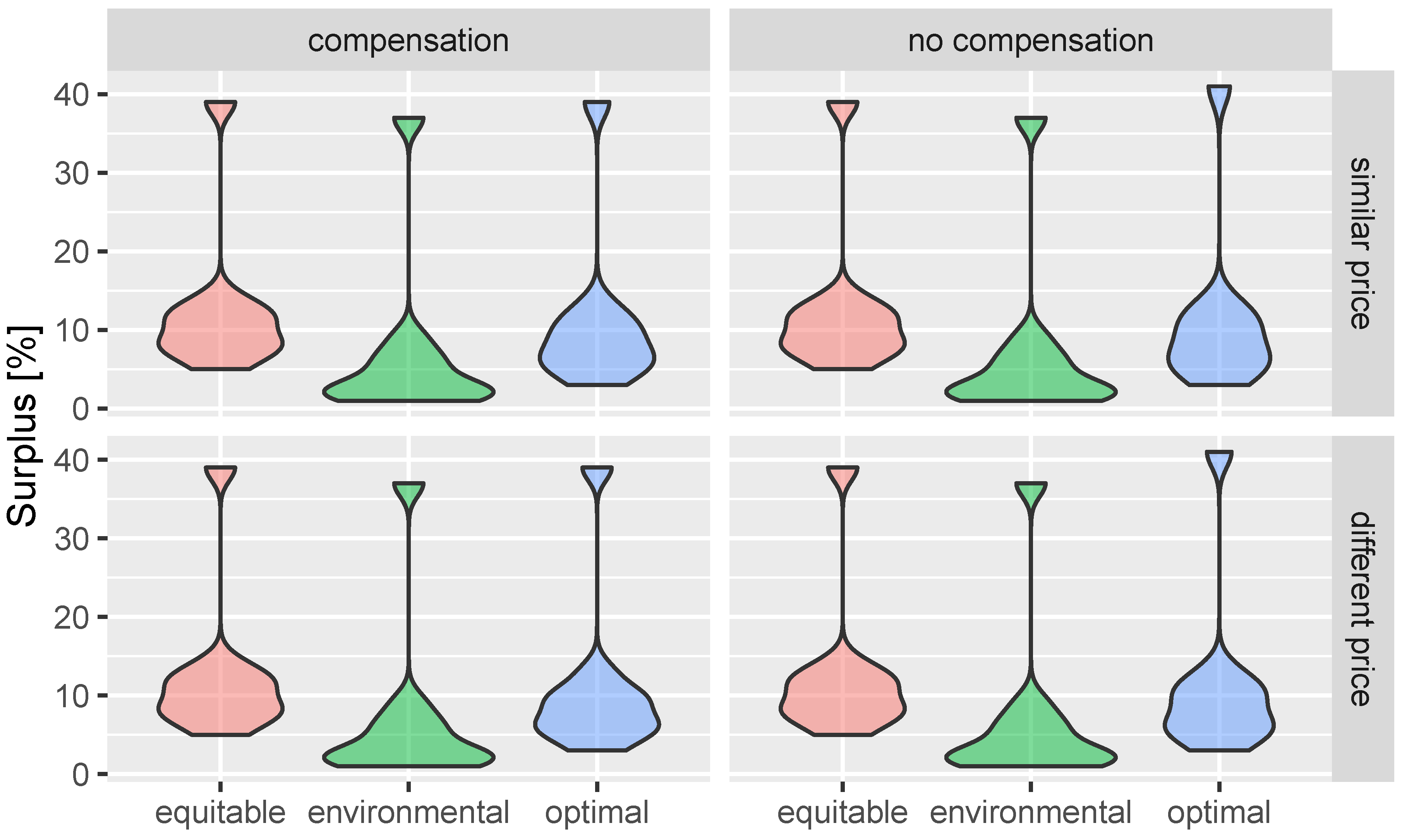

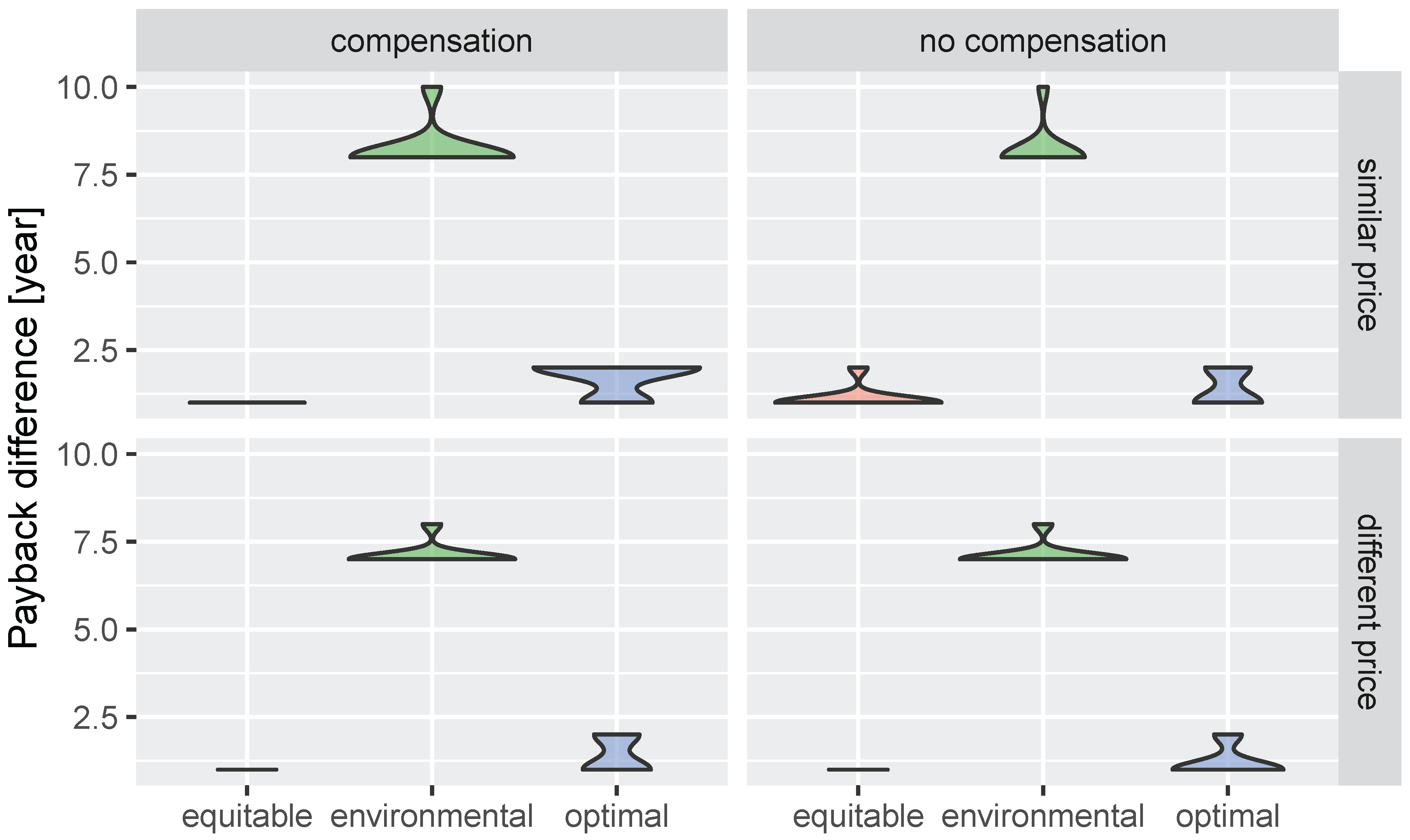

- Equitable: proportional to the individual’s initial investment.

- Environmental: proportional to the hourly electricity consumption.

- Optimised: considering both equity (minimal difference between paybacks) and sustainability (minimal PV generation surplus) [14].

- Case 1: similar shape & similar consumption. It represents the homogeneous case, in which all the participants forming the REC are similar.

- Case 2: different shape & similar consumption. It represents the case in which the participants have the same electric appliances but have different consumption habits. For example, consider a case of a REC composed of residential users whose most significant electric consumption comes from electric-driven ovens and water heating systems, but whose consumption behaviour is considerably different (some of them cook and have baths in the morning, while others do so at night).

- Case 3: similar shape & different consumption. It represents the antagonist of the previous one. Here, the habits are similar, but the net yearly amount of energy consumed is different. For example, this could be the case of a REC formed by households with air conditioning systems for space cooling, but the sizes of the households are different. We expect that the days and hours for using air conditioners will remain the same; however, the number of devices used will vary according to the size of the houses, leading to different levels of total consumption.

- Case 4: different shape & different consumption. It represents the most heterogeneous case. All participants perform completely differently.

- Case 5: similar compensation & similar price. It represents the case where all participants have similar agreements with their electricity traders. Therefore, they have the same purchase tariffs and the same compensation mechanisms

- Case 6: Without compensation & similar price. It represents the case in which the participants have the same purchase tariffs and do not use the compensation mechanism. This means they can sell as much energy as they export, without limit.

- Case 7: compensation & different price. It represents the case where all participants have different purchase tariffs. Moreover, all of them apply the compensation mode.

- Case 8: not compensation & not similar price. It represents the case in which prices are different for all participants and no one applies the compensation mechanism.

2.3. Evaluation

2.4. Dataset

3. Results

3.1. Participants Archetypes

3.2. Scenarios Comparison

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| cost of new sources per time unit | |

| Old energy cost per time unit for each participant | |

| DSO | Distribution System Operator |

| Solar energy excess dispatched to the grid | |

| Energy purchased from the electricity trader company | |

| Hourly solar electricity generation assigned to each participant | |

| Total hourly energy generated by the PV system | |

| Normalized hourly energy allocation coefficient | |

| GAs | Genetic Algorithms |

| Investment | |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| Yearly economic profit | |

| Time-varying electricity purchase price | |

| Time-varying electricity price of the solar surplus dispatched to the grid | |

| Time-varying electricity purchase price | |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| Payback of each participant | |

| RD | Real Decreto |

| REC | Renewable Energy Community |

| SDGs | United Nations Sustainable Development Goals |

| t | time in hours |

References

- United Nations, the Sustainable Development Goals Report – June 2024. New York, USA. https://unstats. un.org/sdgs/report/2024/. Accessed: 2024.

- Capellán-Pérez, I.; Campos-Celador, Á.; Terés-Zubiaga, J. Renewable Energy Cooperatives as an instrument towards the energy transition in Spain. Energy Policy 2018, 123, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramizaru, A.; Uihlein, A. Energy communities: an overview of energy and social innovation; Publications Office of the European Union, 2020.

- Prol, J.L.; Steininger, K.W. Photovoltaic self-consumption is now profitable in Spain: Effects of the new regulation on prosumers’ internal rate of return. Energy Policy 2020, 146, 111793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minelli, F.; Ciriello, I.; Minichiello, F.; D’Agostino, D. From net zero energy buildings to an energy sharing model-The role of NZEBs in renewable energy communities. Renewable Energy, 2024; 120110. [Google Scholar]

- Luzzati, T.; Mura, E.; Pellegrini, L.; Raugi, M.; Salvati, N.; Schito, E.; Scipioni, S.; Testi, D.; Zerbino, P. Are energy community members more flexible than individual prosumers? Evidence from a serious game. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2024; 141114. [Google Scholar]

- Hanke, F.; Guyet, R.; Feenstra, M. Do renewable energy communities deliver energy justice? Exploring insights from 71 European cases. Energy Research & Social Science 2021, 80, 102244. [Google Scholar]

- D’Adamo, I.; Gastaldi, M.; Koh, S.L.; Vigiano, A. Lighting the future of sustainable cities with energy communities: An economic analysis for incentive policy. Cities 2024, 147, 104828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.; Kwon, S. Design of structured control policy for shared energy storage in residential community: A stochastic optimization approach. Applied Energy 2021, 298, 117182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, L.; Kockar, I.; Wogrin, S. Towards resilient energy communities: Evaluating the impact of economic and technical optimization. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2024, 155, 109592. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Liu, A.; Ma, L.; Guo, J.; Ma, F.; Han, Z.; Wang, L. Multi-parameter cooperative optimization and solution method for regional integrated energy system. Sustainable Cities and Society 2023, 95, 104622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, J.; Jing, H.; Li, Y.; Monga, V. Small-signal stability enhancement of islanded microgrids via domain-enriched optimization. Applied Energy 2024, 353, 122172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Netto, S.V.; Sobral, M.F.F.; Ribeiro, A.R.B.; Soares, G.R.d.L. Concepts and forms of greenwashing: A systematic review. Environmental Sciences Europe 2020, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzari, F.; Mor, G.; Cipriano, J.; Solsona, F.; Chemisana, D.; Guericke, D. Optimizing planning and operation of renewable energy communities with genetic algorithms. Applied Energy 2023, 338, 120906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, L.; Bachhiesl, U.; Wogrin, S. The current state of research on energy communities. Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik 2021, 138, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiasoumas, G.; Psara, K.; Georghiou, G. A Review of Energy Communities: Definitions, Technologies, Data Management. In Proceedings of the The 2022 2nd International Conference on Energy Transition in the Mediterranean Area (SyNERGY MED). IEEE: New York, NY, USA; 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hanke, F.; Guyet, R.; Feenstra, M. Do renewable energy communities deliver energy justice? Exploring insights from 71 European cases. Energy Research & Social Science 2021, 80, 102244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warbroek, B.; Hoppe, T.; Coenen, F.; Bressers, H. The Role of Intermediaries in Supporting Local Low-Carbon Energy Initiatives. Sustainability 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckesser, T.; Dominković, D.F.; Blomgren, E.M.; Schledorn, A.; Madsen, H. Renewable Energy Communities: Optimal sizing and distribution grid impact of photo-voltaics and battery storage. Applied Energy 2021, 301, 117408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Ali, A.; D’Angola, A. A Review of Renewable Energy Communities: Concepts, Scope, Progress, Challenges, and Recommendations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inês, C.; Guilherme, P.L.; Esther, M.G.; Swantje, G.; Stephen, H.; Lars, H. Regulatory challenges and opportunities for collective renewable energy prosumers in the EU. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso-Burgos, Á.; Ribó-Pérez, D.; Alcázar-Ortega, M.; Gómez-Navarro, T. Local Energy Communities in Spain: Economic Implications of the New Tariff and Variable Coefficients. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrucca, L.; Fraley, C.; Murphy, T.B.; Raftery, A.E. Model-based clustering, classification, and density estimation using mclust in R; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2023.

- Mora, D.; Carpino, C.; De Simone, M. Energy consumption of residential buildings and occupancy profiles. A case study in Mediterranean climatic conditions. Energy Efficiency 2018, 11, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, J.; Gao, X.; Yang, X.; He, Y.L. A multi-strategy improved sparrow search algorithm of large-scale refrigeration system: Optimal loading distribution of chillers. Applied Energy 2023, 349, 121623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).