Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Adaptation of the ECC model to the specific cost structures of energy communities;

- The application of ECCs for enhanced analysis of the integration of different energy sectors (electricity, heating, natural gas, hydrogen, renewable energy sources);

- Development of a methodological framework for quantifying sector synergies and assessing economic benefits in decentralised energy systems.

2. Materials and Methods

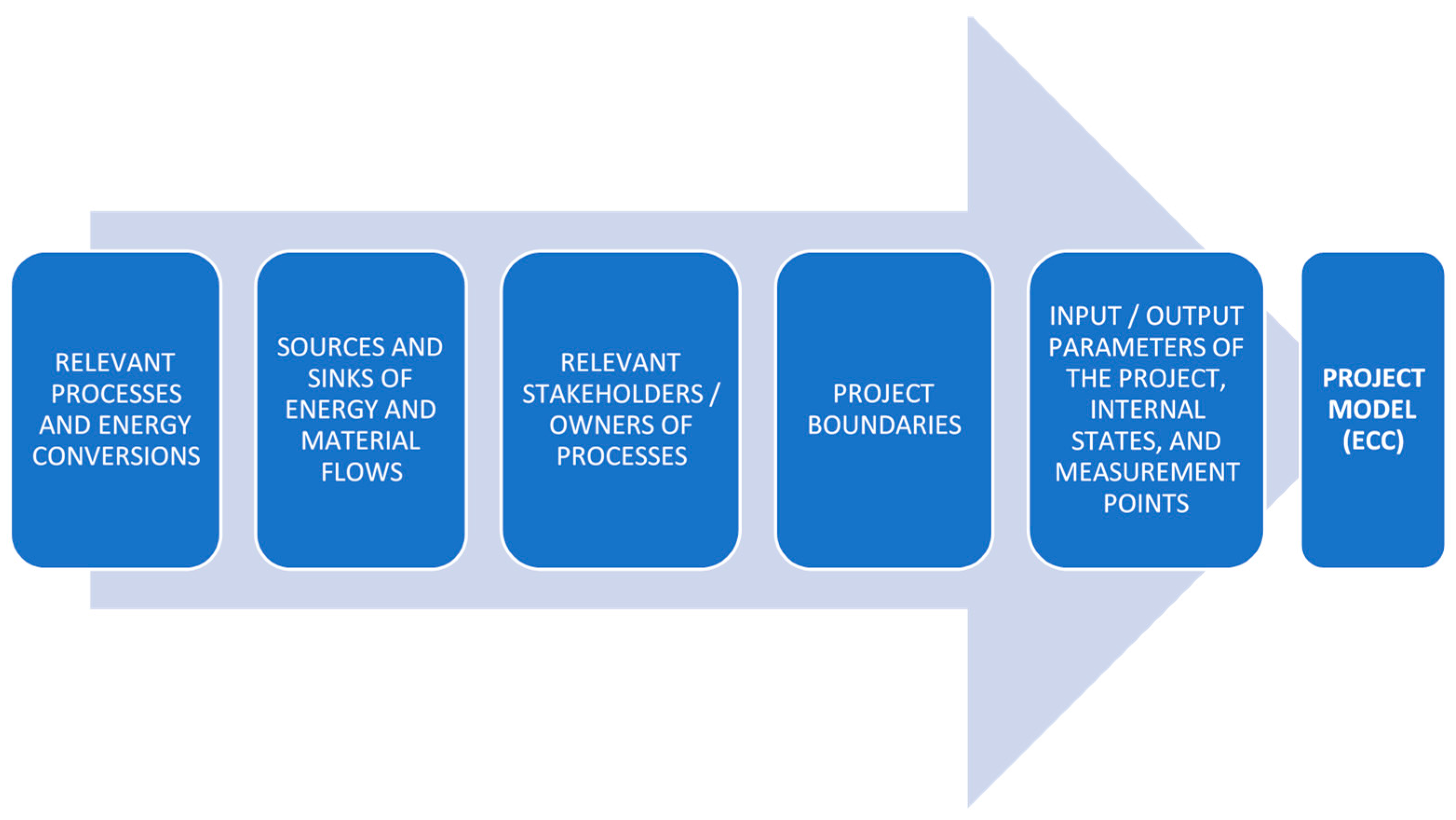

2.1. Presentation of Systems with the Structure of Energy Cost Centres

- The process or activity requiring energy must have a measurable output value;

- Energy use and/or environmental impact can be measured directly;

- The cost of measurement should not exceed 10 to 20% of the annual costs for aligning;

- ECCs with environmental legislation requirements;

- Responsibility for energy effects and environmental impacts in a particular area can be assigned to the person working in or responsible for that area;

- A standardized performance metric can be defined;

- Realistic goals can be set, and efficiency improvements can be monitored [10].

2.2. Model for Energy Use Analysis Based on Energy Cost Centres

2.3. Case Study: Improving Energy Efficiency, Increasing RES Generation and Reducing CO₂ Emissions in the Local Community in Slovenia

3. Results

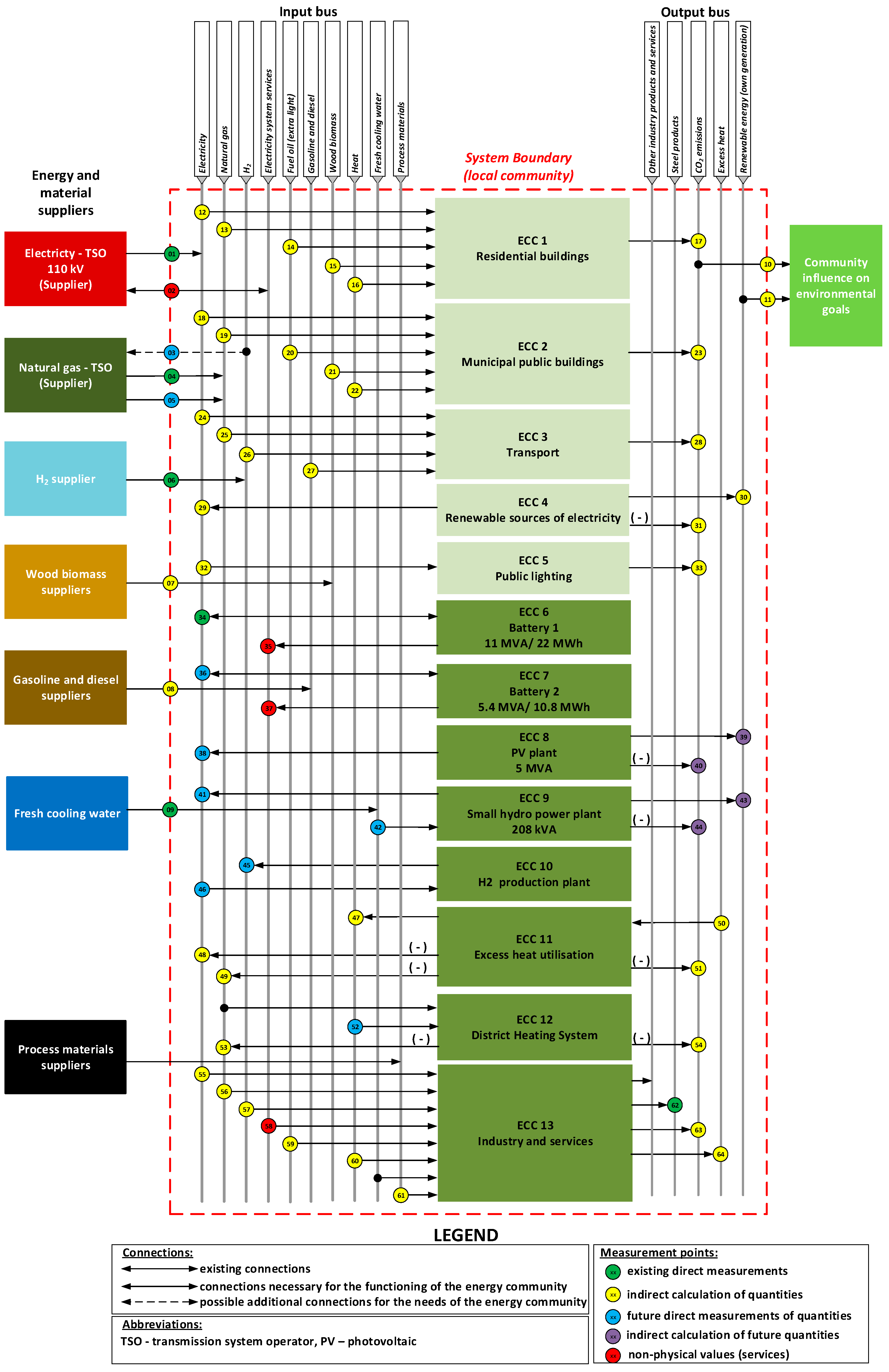

3.1. Identification of Energy and Material Flows and Representation Using the ECC Structure

- To assess the feasibility of producing electricity from renewable sources (solar, hydro potential);

- To explore the possibility of producing green hydrogen;

- To examine the potential for regulating electricity demand;

- To determine whether the proposed concept, supported by data from the district heating operator, could be used to upgrade the existing district heating system and as a decision-making tool for the steelworks to enhance their production processes.

3.1.1. Electricity Production from Renewable Sources and Demand Management

3.1.2. Household Energy Use – ECC 1

| Energy Carrier | CO₂ Emission Factor |

|---|---|

| Electricity | 0.350 t CO₂ / MWh |

| Natural Gas | 0.184 t CO₂ / MWh; 0.00185215 t CO₂ / Nm³ |

| Gasoline | 0.249 t CO₂ / MWh |

| Diesel | 0.267 t CO₂ / MWh |

| Heating Oil | 0.270 t CO₂ / MWh |

| Woody Biomass | 0 t CO₂ / MWh (non-net source of CO₂ according to IPCC 1) |

3.1.3. Energy Use in Municipal Public Buildings – ECC 2

3.1.4. Energy Use in Transport – ECC 3

3.1.5. Existing Renewable Energy Sources – ECC 4

3.1.6. Energy Use for Public Lighting – ECC 5

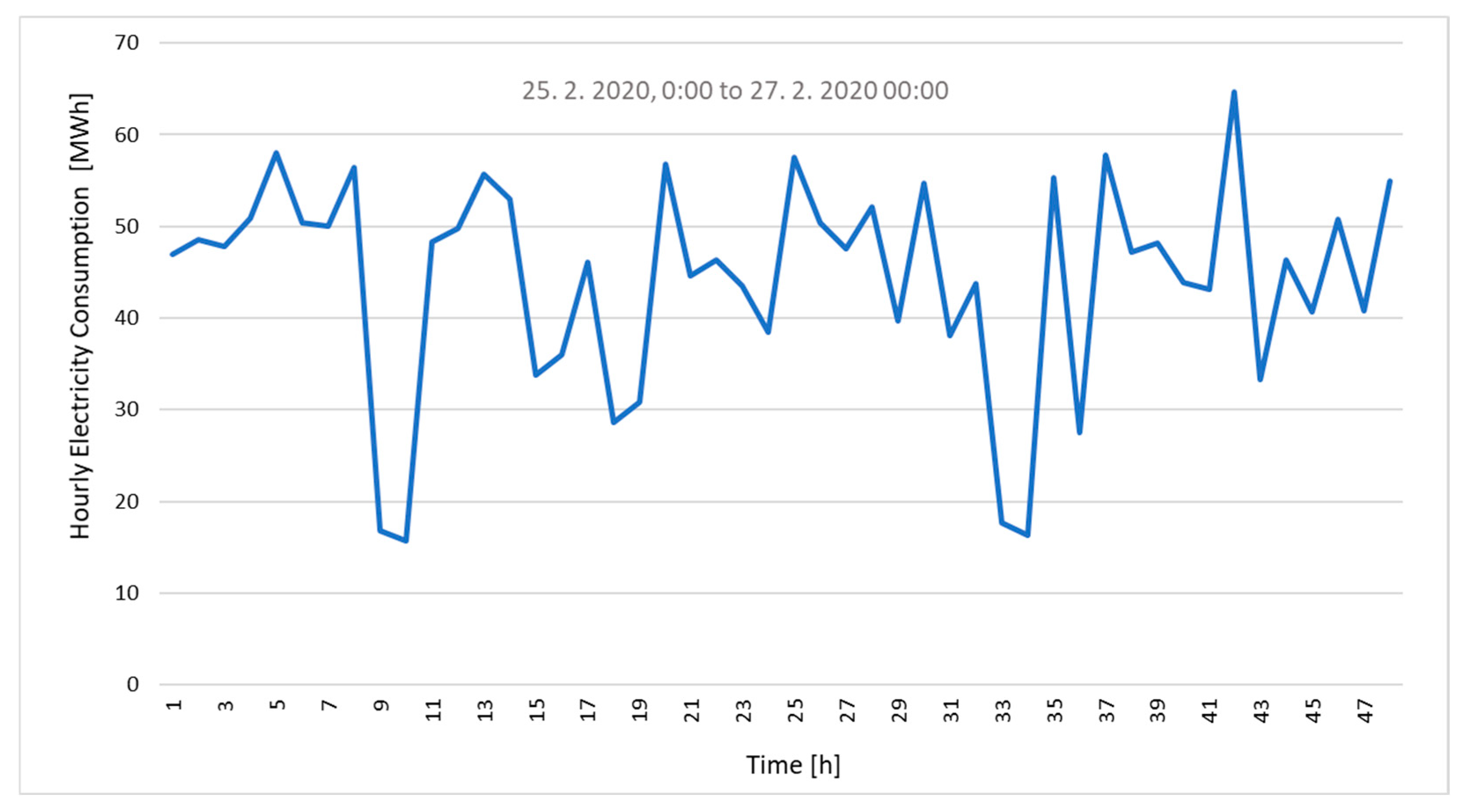

3.1.7. Demand Management with Battery Energy Storage – ECC 6 and ECC 7

- C-rate ratio: 0.5;

- Charging/discharging efficiency: 85 %;

- Depth of discharge: 0.60 (ranging from 0.20 to 0.80);

- Simulations were performed for two storage capacities: 10.8 MWh and 22.0 MWh.

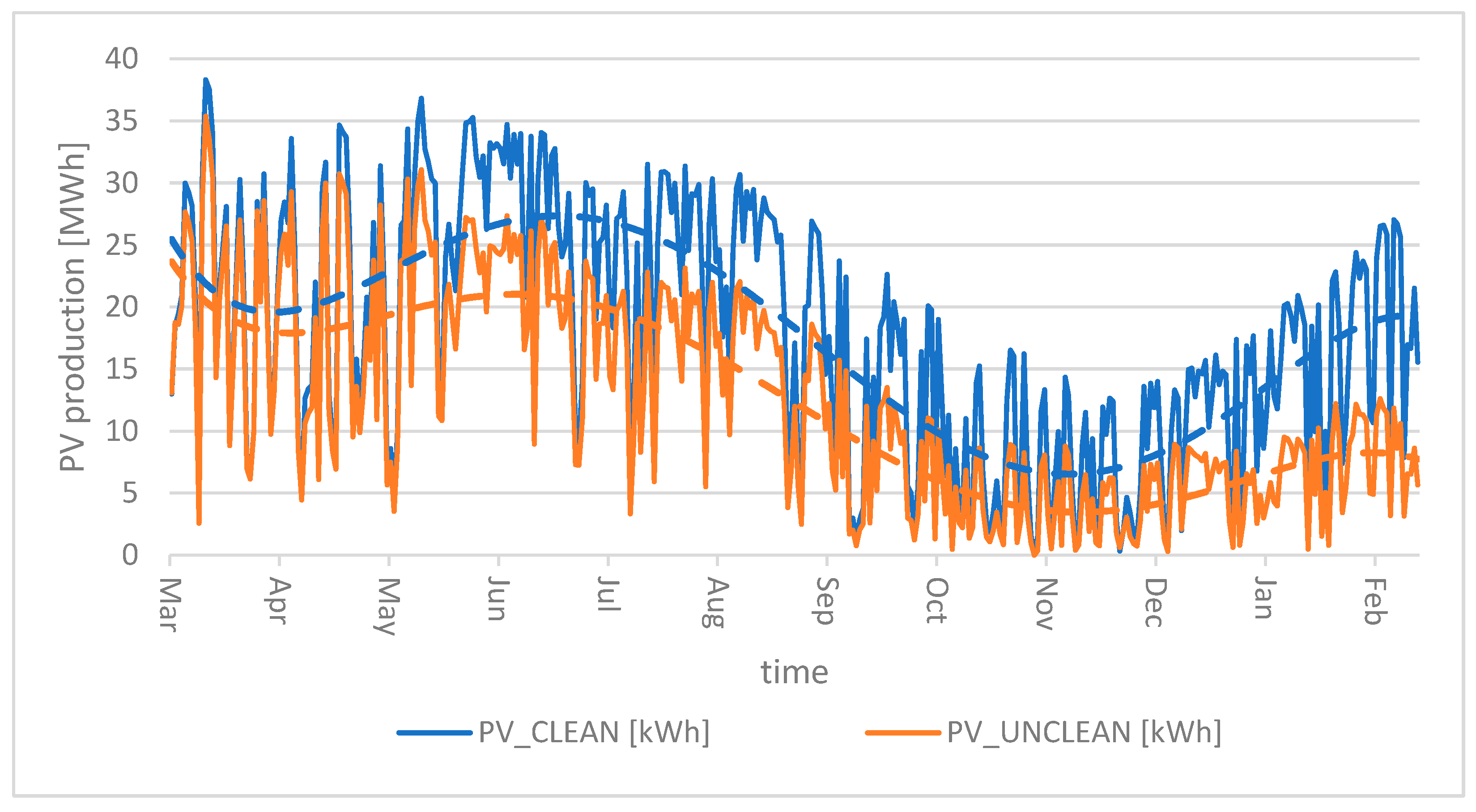

3.1.8. Photovoltaic Power Plant – ECC 8

3.1.3.1. Research on the Impact of Dust on Electricity Production

- Two identical PV modules (280 Wp);

- Two identical microinverters (290 VA);

- Two advanced electricity meters;

- A support structure for two modules (21° tilt, south-facing), and

- An electrical cabinet containing all necessary components.

- Reference period: Both test PV panels were cleaned three times per week; no deviations in electricity production were observed during this time, confirming the suitability of the test environment;

- Test period: Continuous cleaning was performed on only one panel, three times per week, over a period of one and a half years. During this test period, dust samples were collected and subjected to chemical and electron microscopy analyses;

- Post-test cleaning period: Initially, both test panels were cleaned. Over one month, both panels underwent cleaning three times per week. This cleaning protocol was conducted to confirm the feasibility of cleaning the previously uncleaned PV panel and to assess potential panel degradation due to dust accumulation over one and a half years.

- The environmental impact on micro-locations and the required cleaning intervals to maintain the desired PV efficiency;

- The primary source of dust particles in the broader steel plant area;

- Solar irradiation levels at different locations and the expected PV yield;

- The impact of dust particles on electricity production near the main dust source (details in the following section);

- No panel degradation was detected due to dust accumulation after one and a half years, as no deviations in electricity production were observed following the equal cleaning of both test panels.

- Both test panels were cleaned, and their identical efficiency was confirmed;

- A nano-coating was applied to one of the test panels;

- The electricity production of both systems was monitored without cleaning over a one-year period.

3.1.9. Small Hydropower Plant – ECC 9

3.1.10. Green Hydrogen Production – ECC 10

- What are the expected future price trends for hydrogen production technology?

- What is the maximum hourly hydrogen injection capacity at the steel plant site for the national gas grid?

- What government support is available for such projects?

- What is the most suitable business model for constructing a demonstration plant?

- What environmental and safety regulations must be met for hydrogen production?

- What are the prospects for developing a (local) hydrogen market, including its use in transport?

3.1.11. Reuse of Excess Heat in Energy-Intensive Production and District Heating – ECC 11 to ECC 13

3.2. The Overall Contribution of the Energy Community to Achieving Sustainability Goals

3.3. Results of the Economic Feasibility Analysis

- The provision of system services via an additional battery storage unit (ECC 7), assuming a required rate of return (RRR) of 5%, annual maintenance costs, and a 10-year lifespan, results in a payback period of 5.7 years under current deviation pricing.

- The investment in photovoltaics (ECC 8), based on a 15-year economic lifetime, 5 % RRR, and including maintenance and insurance costs, yields a payback period of 6.1 years.

- The small hydropower plant (ECC 9), with a 30-year economic lifetime, 5% RRR, and maintenance costs considered, achieves payback in 8 years.

- Hydrogen production (ECC 10), under current market conditions marked by high electricity prices, is not economically viable—even with 100% investment subsidies. However, should periods of very low or negative electricity prices from RES surpluses become more frequent and prolonged, hydrogen production may become justifiable, particularly as a means of providing system balancing services.

- The utilisation of excess heat (ECC 11 to ECC 13) was evaluated in three scenarios, varying in district heating system integration and the scope of heat recovery. Payback periods ranged from 9.2 to 18.9 years. With a 50% investment subsidy, these periods are reduced to between 4.6 and 9.2 years.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ECC | Energy cost centre |

| CO₂ | Carbon dioxide |

| TSO | Transmission system operator |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| MP | Measurement point |

| MWh | Megawatt hour |

| Nm3 | Normal cubic metre - the amount of dry gas that occupies a volume of one cubic meter at a temperature of 273.15 K |

| m3/s | Cubic metre per second |

| kg/s | kilogram per second |

| t | Tonne |

| RES | Renewable energy sources |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| TAPE | A record of stock (or energy price) transactions throughout the trading day |

| kV | Kilovolt |

| MVA | Megavolt ampere |

| Wp | Watt-peak |

| kVA | Kilovolt ampere |

| SHP | Small hydropower plant |

| NECP | National Energy and Climate Plan |

| RRR | Required rate of return |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

References

- Gjorgievski, V. Z.; Cundeva, S.; Georghiou, G. E. Social arrangements, technical designs and impacts of energy communities: A review. Renewable Energy 2021, 169, pp. 1138-1156. [CrossRef]

- Heldeweg, M. A.; Saintier, S. Renewable energy communities as ‘socio-legal institutions’: A normative frame for energy decentralization? Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 119. [CrossRef]

- Dóci, G.; Vasileiadou, E.; Petersen, A. C. Exploring the transition potential of renewable energy communities, Futures 2015, 66, pp 85-95. [CrossRef]

- Mišljenović, N.; Žnidarec, M.; Knežević, G.; Šljivac, D.; Sumper, A. A Review of Energy Management Systems and Organizational Structures of Prosumers. Energies 2023, 16. [CrossRef]

- Bohvalovs, G.; Vanaga, R.; Brakovska, V.; Freimanis, R.; Blumberga, A. Energy Community Measures Evaluation via Differential Evolution Optimization. Environmental and Climate Technologies 2022, 26-1, pp. 606-615. [CrossRef]

- Makatora, D.; Makatora, A.; Zenkin, M.; Mykhalko, A.; Shostachuk, O. Organizational and Economic Mechanism of Improving Energy Costs in the Technological and Process Constant of the Printing Industry. Management Theory and Studies for Rural Business and Infrastructure Development 2024, 46-4, pp. 609-618. [CrossRef]

- Mickovic, A.; Wouters, M. Energy costs information in manufacturing companies: A systematic literature review, Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 254. [CrossRef]

- Teplická, K.; Khouri, S.; Mehana, I.; Petrovská, I. Energy Cost Reduction in the Administrative Building by the Implementation of Technical Innovations in Slovakia. Economies 2024, 12, . [CrossRef]

- Sola, A. V. H.; Mota, C. M. M. Influencing factors on energy management in industries, Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 248. [CrossRef]

- Morvaj, Z.; Gvozdenac, D.; Tomšić, Ž. Sustavno gospodarenje energijom i upravljanje utjecajima na okoliš u industriji; Energetika marketing: Zagreb, Croatia, 2016; pp. 130-135.

- Li, N.; Okur, Ö. Economic analysis of energy communities: Investment options and cost allocation, Applied Energy 2023, 336. [CrossRef]

- Lode, M. L.; Heuninckx, S.; Boveldt, G.; Macharis, C.; Coosemans, T. Designing successful energy communities: A comparison of seven pilots in Europe applying the Multi-Actor Multi-Criteria Analysis, Energy Research & Social Science 2022, 90. [CrossRef]

- Lowitzsch, J.; Hoicka, C. E.; Tulder, F. J. Renewable energy communities under the 2019 European Clean Energy Package – Governance model for the energy clusters of the future?, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 122. [CrossRef]

- Tutak, M.; Brodny, J.; Bindzár, P. Assessing the Level of Energy and Climate Sustainability in the European Union Countries in the Context of the European Green Deal Strategy and Agenda 2030, Energies 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Morvay, Z. K.; Gvozdenac, D. D. Applied Industrial Energy and Environmental Management; Wiley & Sons: Chichester, United Kingdom, 2008.

- Mikulčić, H.; Baleta, J.; Klemeš, J. J.; Wang, X. Energy transition and the role of system integration of the energy, water and environmental systems, Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 292. [CrossRef]

- Klemeš, J. J.; Lam, H. L. Process integration for energy saving and pollution reduction, Energy 2011, 36 (8), pp. 4586-4587. [CrossRef]

- Sučić, B.; Košnjek, E.; Đorić, M.; Al_Mansour, F.; Matkovič, M.; Damjan, T. Innovative approach to implementing advanced energy projects in urban areas – from comprehensive simulation to actual implementation. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Sustainable Energy & Environmental Protection, Vienna, Austria, 9th-12th September 2024.

- Občina Jesenice, Lokalni energetska concept občine Jesenice za obdobje 2022 do 2032, 2022. Available online: https://www.jesenice.si/obcina-jesenice/razvojni-dokumenti/item/24404-lokalni-energetski-koncept-2022-2032 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- The International Energy Agency (IEA), World Energy Outlook 2021, Paris: IEA/OECD, 2021. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2021 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Rootzén, J.; Johnsson, F.; CO2 emissions abatement in the Nordic carbon-intensive industry – An end-game in sight?, Energy 2015, 80, pp. 715-730. [CrossRef]

- The International Energy Agency (IEA), Iron and Steel Technology Roadmap: Towards more sustainable steelmaking, IEA Publications, 2020. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/iron-and-steel-technology-roadmap (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Ministry of Environment, Climate and Energy, Updated Integral National Energy and Climate Plan of the Republic of Slovenia, Ljubljana, 18.12.2024, 2024. Available online: https://www.energetika-portal.si/fileadmin/dokumenti/publikacije/nepn/dokumenti/nepn2024_final_dec2024.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Malinauskaite, J.; Jouhara, H.; Egilegor, B.; Al-Mansour, F.; Ahmad, L.; Pusnik, M. Energy efficiency in the industrial sector in the EU, Slovenia, and Spain, Energy 2020, 208. [CrossRef]

- Košnjek, E.; Sučić, B.; Kostić, D.; Smolej, T. An energy community as a platform for local sector coupling: From complex modelling to simulation and implementation, Energy 2024, 286. [CrossRef]

- Billerbeck, A.; Fritz, M.; Aydemir, A.; Manz, P. Strategic Heating and Cooling Planning to Shape Our Future Cities, In Proceedings of the European Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ECEEE Summer Study) – Panel 5: Towards sustainable and resilient communities, Hyères, France, 6-11 June 2022.

- Olabi, A. G.; Abdelkareem, M. A.; Jouhara, H. Energy digitalization: Main categories, applications, merits, and barriers, Energy 2023, 271, 126899, . [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Alimi, D.; Knieling, J.; Camara, C. Stakeholder Collaboration in Energy Transition: Experiences from Urban Testbeds in the Baltic Sea Region. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9645. [CrossRef]

- Ceglia, F.; Esposito, P.; Marrasso, E.; Sasso, M. From smart energy community to smart energy municipalities: Literature review, agendas and pathways, Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 254. [CrossRef]

- Farid, H. M. A.; Iram, S.; Shakeel, H. M.; Hill, R. Enhancing stakeholder engagement in building energy performance assessment: A state-of-the-art literature survey, Energy Strategy Reviews 2024, 56, 101560, . [CrossRef]

- Biegańska, M. IoT-Based Decentralized Energy Systems. Energies 2022, 15, 7830. [CrossRef]

| MP | Description of the Measurement Point (MP) Parameter | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| 01 | Electricity consumption from the electricity transmission grid | MWh |

| 02 | Provision/use of electricity system services by the TSO | |

| 03 | Locally produced hydrogen injected into the gas transmission network | Nm3 |

| 04 | Consumption of natural gas from the gas transmission network | Nm3 |

| 05 | Use of natural gas in the heating stations of the district heating system | Nm3 |

| 06 | Supply of "grey" hydrogen | Nm3 |

| 07 | Energy supply in the form of wood biomass | MWh |

| 08 | Energy supply in the form of gasoline and diesel | MWh |

| 09 | Cooling water flow | m3/s |

| 10 | Reduction in CO2 emissions due to new RES and the use of excess heat | MWh |

| 11 | The overall contribution of the project to achieving the national RES target | MWh |

| 12 | Electricity consumption in households | MWh |

| 13 | Natural gas consumption in households | Nm3 |

| 14 | Energy use in the form of heating oil in households | MWh |

| 15 | Energy use in the form of wood biomass in households | MWh |

| 16 | Heat use from district heating systems in households | MWh |

| 17 | CO2 emissions from energy use in households | t |

| 18 | Electricity consumption in municipal public buildings | MWh |

| 19 | Natural gas consumption in municipal public buildings | Nm3 |

| 20 | Energy use in the form of heating oil in municipal public buildings | MWh |

| 21 | Energy use in the form of wood biomass in municipal public buildings | MWh |

| 22 | Heat use from district heating systems in municipal public buildings | MWh |

| 23 | CO2 emissions from energy use in municipal public buildings | t |

| 24 | Electricity consumption in transport | MWh |

| 25 | Natural gas consumption in transport | Nm3 |

| 26 | Hydrogen consumption in transport | Nm3 |

| 27 | Energy use in the form of gasoline and diesel in transport | MWh |

| 28 | CO2 emissions from energy use in transport | t |

| 29 | Electricity generation from existing RES | MWh |

| 30 | Contribution of existing sources to achieving the national RES target | MWh |

| 31 | Reduction in CO2 emissions due to the use of RES | t |

| 32 | Electricity use for public lighting | MWh |

| 33 | CO2 emissions from electricity use for public lighting | t |

| 34 | Electricity consumption and discharge from battery storage unit 1 | MWh |

| 35 | Provision of system services with battery storage unit 1 | |

| 36 | Electricity consumption and discharge from battery storage unit 2 | MWh |

| 37 | Provision of system services with battery storage unit 2 | |

| 38 | Electricity production in the the PV | MWh |

| 39 | Contribution of the PV power plant to achieving the national RES target | MWh |

| 40 | Reduction of CO2 emissions due to electricity production in the PV | t |

| 41 | Used cooling water flow for operating a small hydroelectric power plant | m3/s |

| 42 | Electricity production in the small hydroelectric plant (SHP) | MWh |

| 43 | Contribution of the SHP to achieving the national RES target | MWh |

| 44 | Reduction of CO2 emissions due to electricity production in the SHP | t |

| 45 | Electricity consumption for hydrogen production | MWh |

| 46 | Hydrogen production | t |

| 47 | Total amount of useful excess heat used | MWh |

| 48 | Reduction in electricity consumption due to the use of excess heat | MWh |

| 49 | Reduction in natural gas consumption due to the use of excess heat | Nm3 |

| 50 | Useful excess heat used | MWh |

| 51 | Reduction in CO2 emissions due to the use of excess heat | t |

| 52 | Heat discharged into the district heating system | MWh |

| 53 | Reduction in natural gas consumption in the DH system due to the use of excess heat | Nm3 |

| 54 | Reduction in CO2 emissions due to the use of excess heat in the DH system | t |

| 55 | Electricity consumption in industry and services | MWh |

| 56 | Natural gas consumption in industry and services | Nm3 |

| 57 | Hydrogen consumption in industry and services | Nm3 |

| 58 | Use of system services in industry and services | |

| 59 | Energy use in the form of heating oil in industry and services | MWh |

| 60 | Heat use from district heating systems in industry and services | MWh |

| 61 | Supply of raw materials for steel production | t |

| 62 | Quantity of steel products produced | t |

| 63 | CO2 emissions from in industry and services | t |

| 64 | Generated excess heat in industry and services | MWh |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).