Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. General Considerations

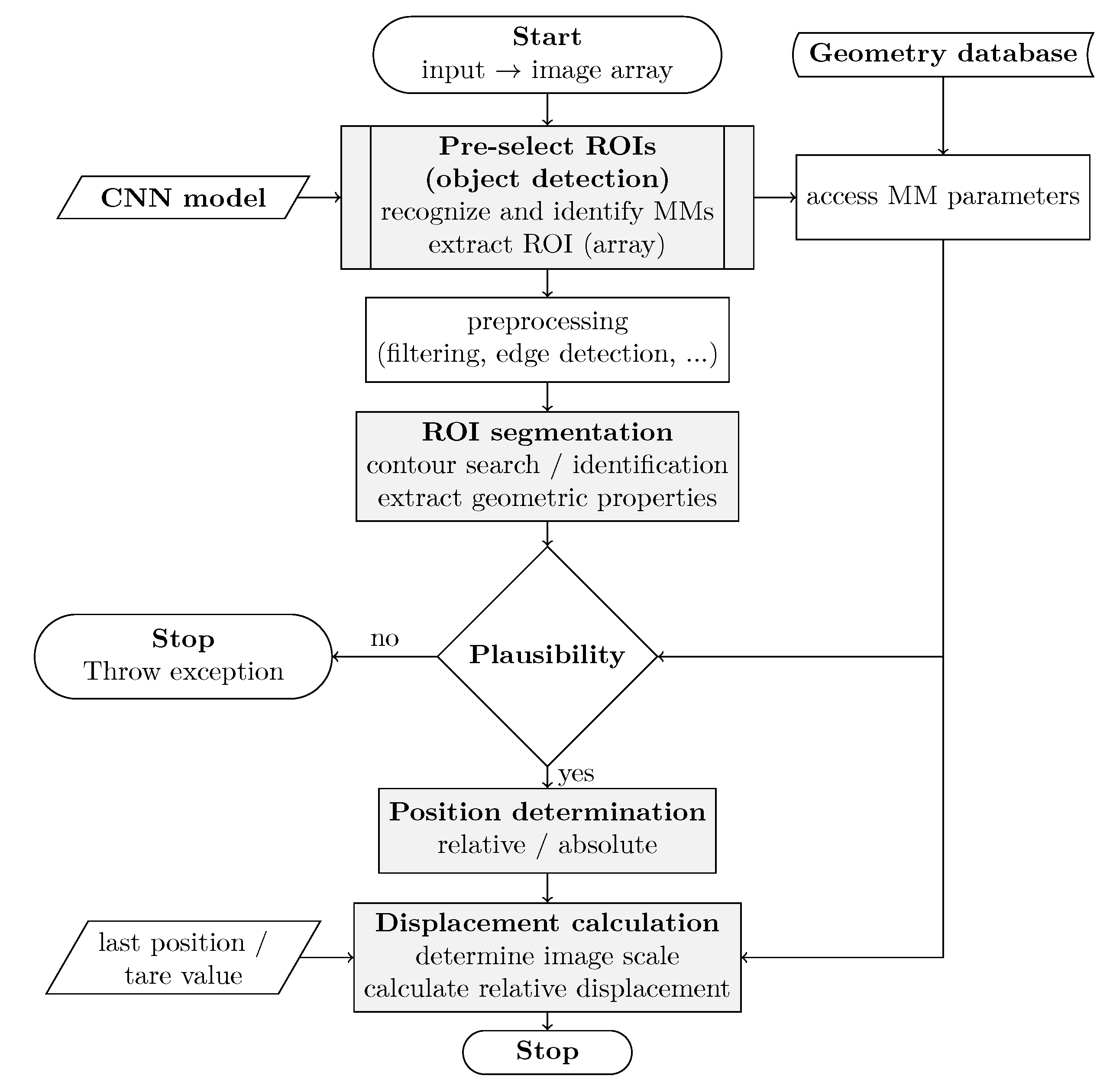

- Pre-select ROIs based on object detection.

- ROI segmentation.

- Relative/absolute position determination.

- Displacement calculation.

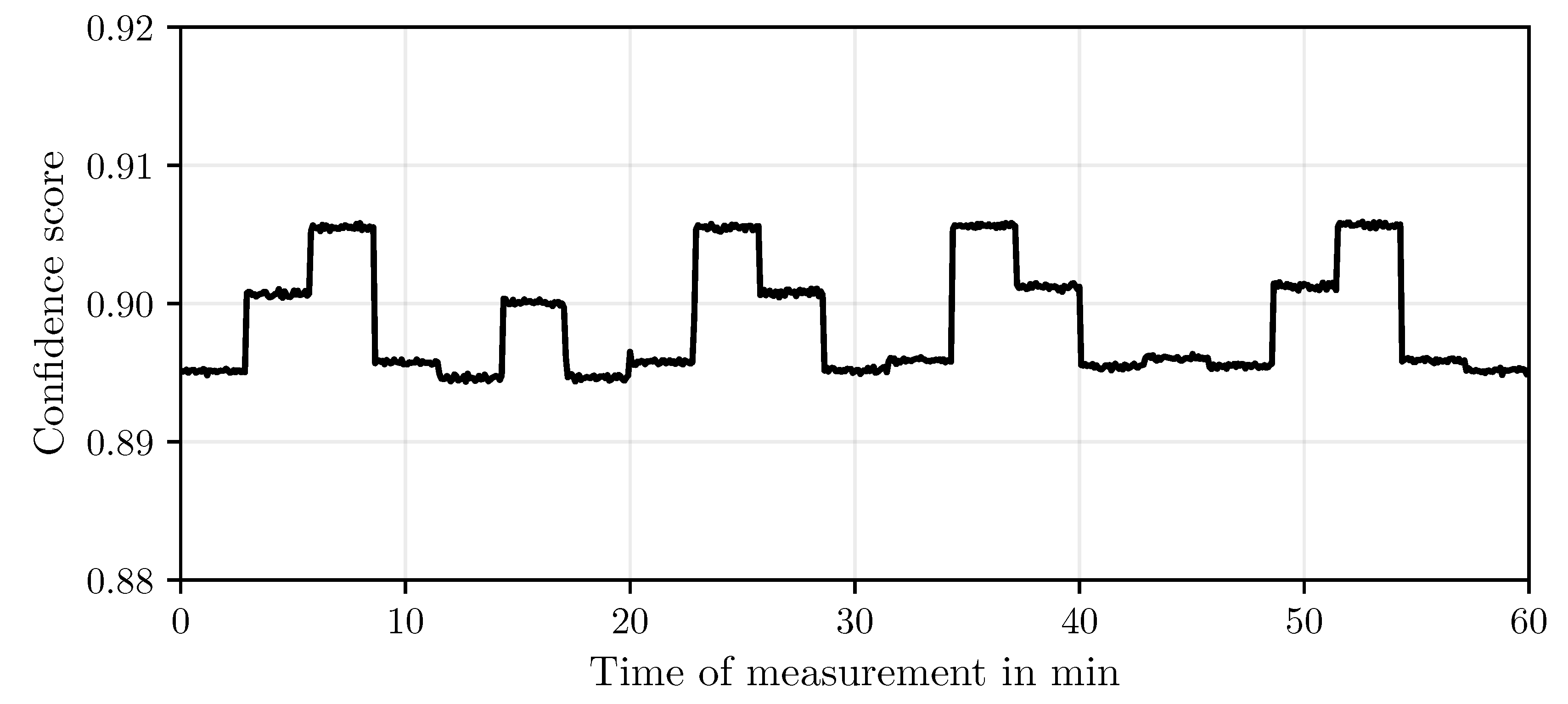

2.1. Pre-Select ROIs Based on Object Detection

- IDs of detected objects.

- Associated confidence scores.

- Coordinates of associated bounding boxes.

- Coordinates of associated centroids.

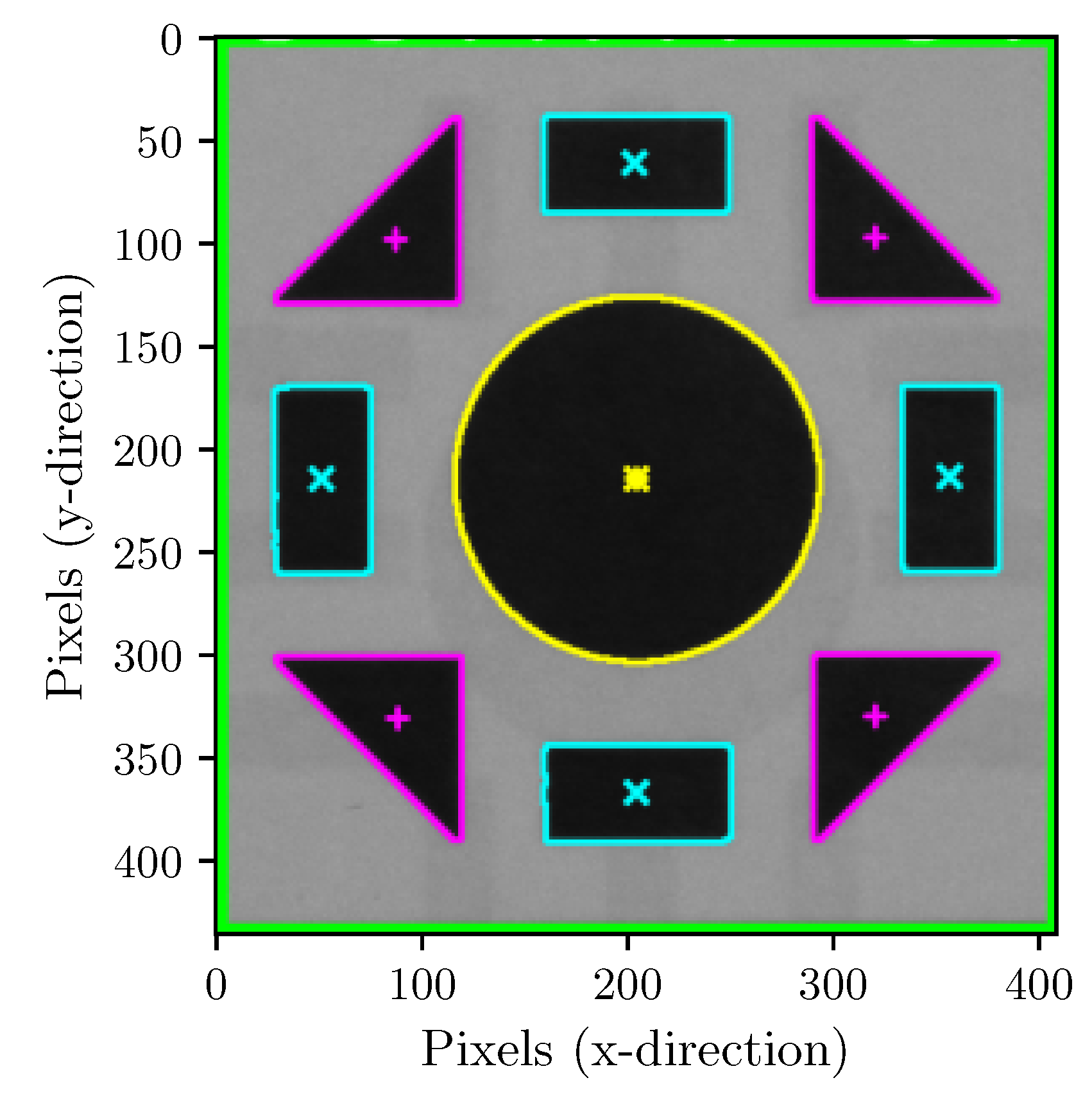

2.2. ROI Segmentation

- Recognized contours.

- Classification of contours into geometric elements.

- Geometric properties of the elements (e.g., coordinates of the geometric centers, surface area).

2.3. Relative/Absolute Position Determination

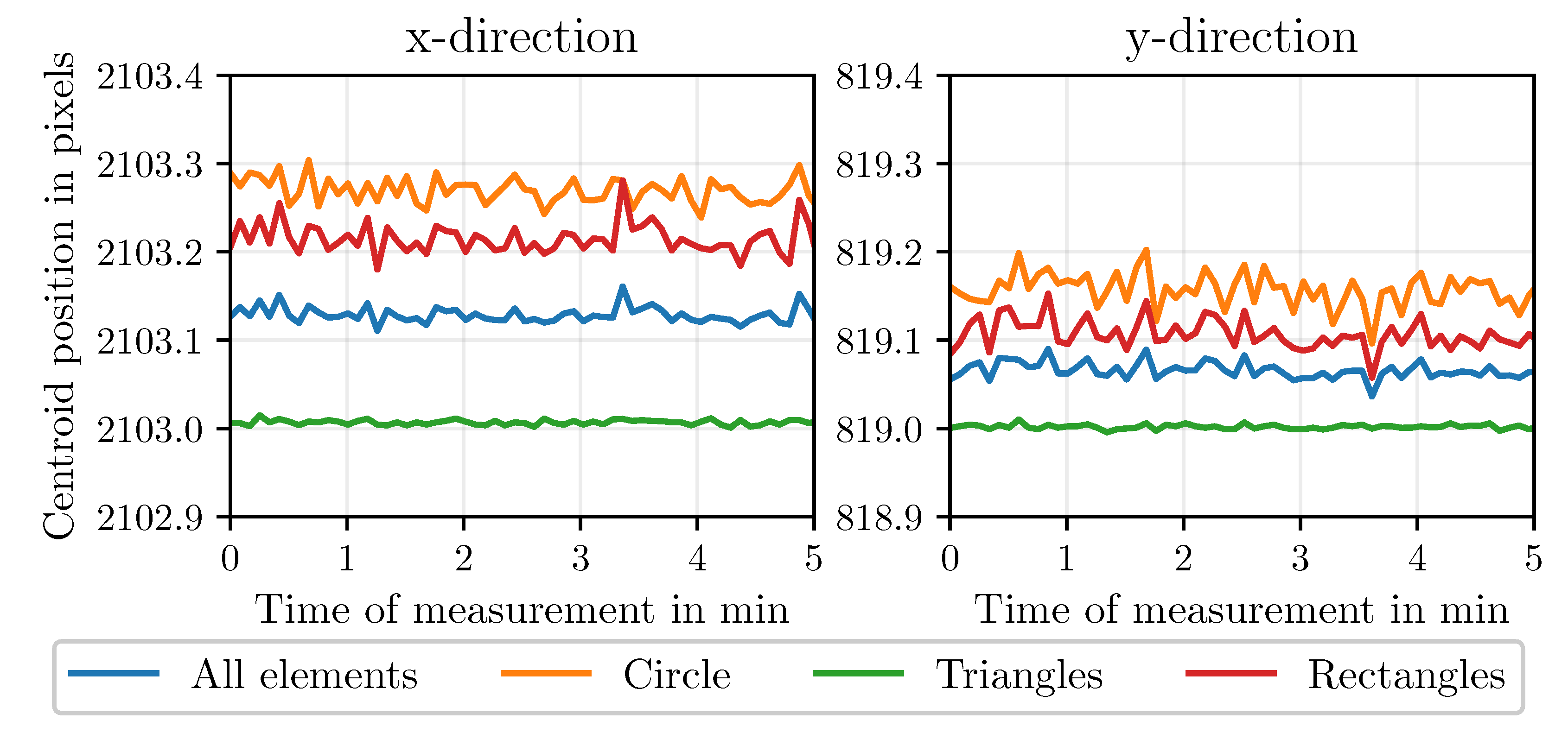

2.4. Displacement Calculation

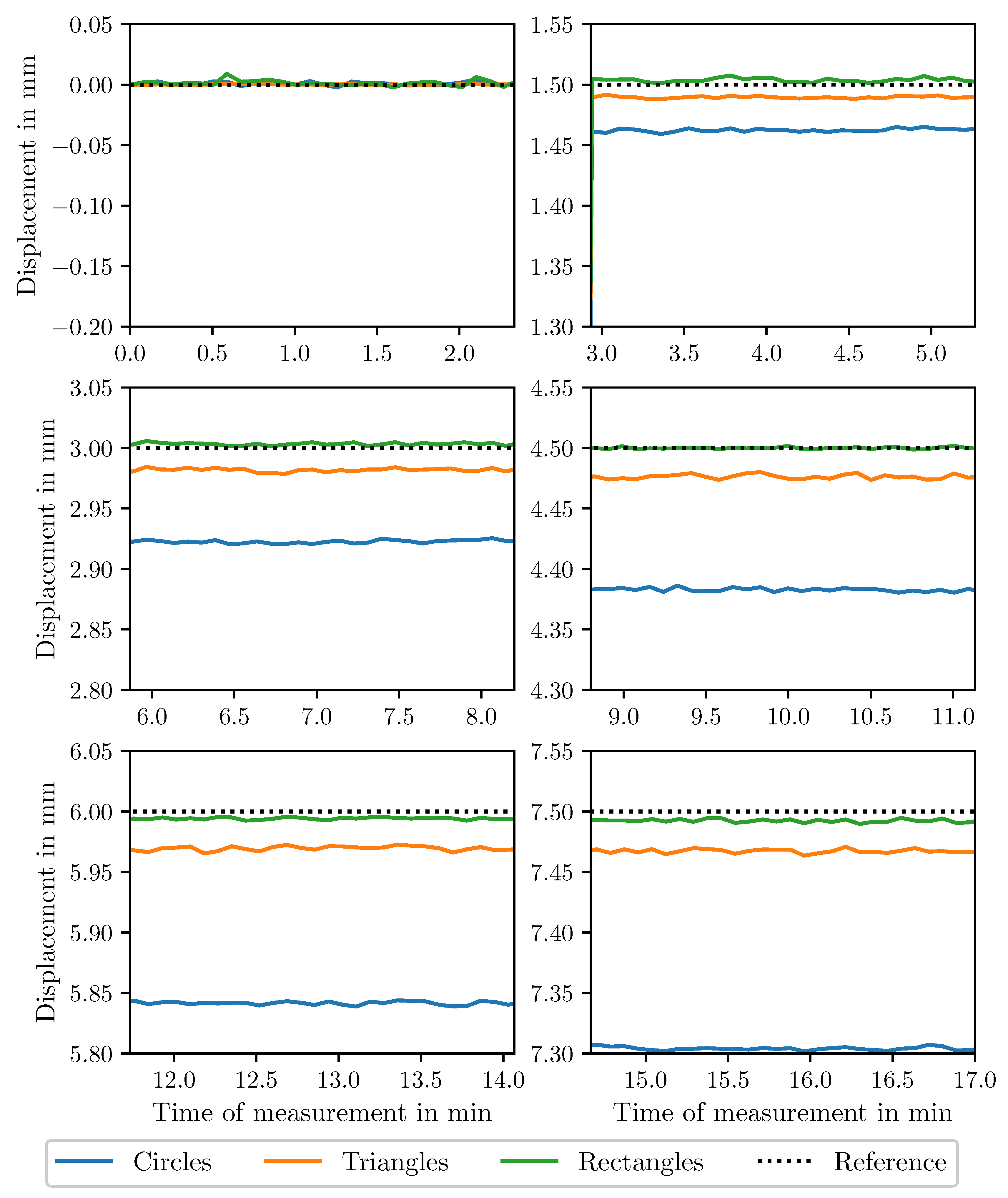

3. Experimental Investigations

3.1. Experimental Design

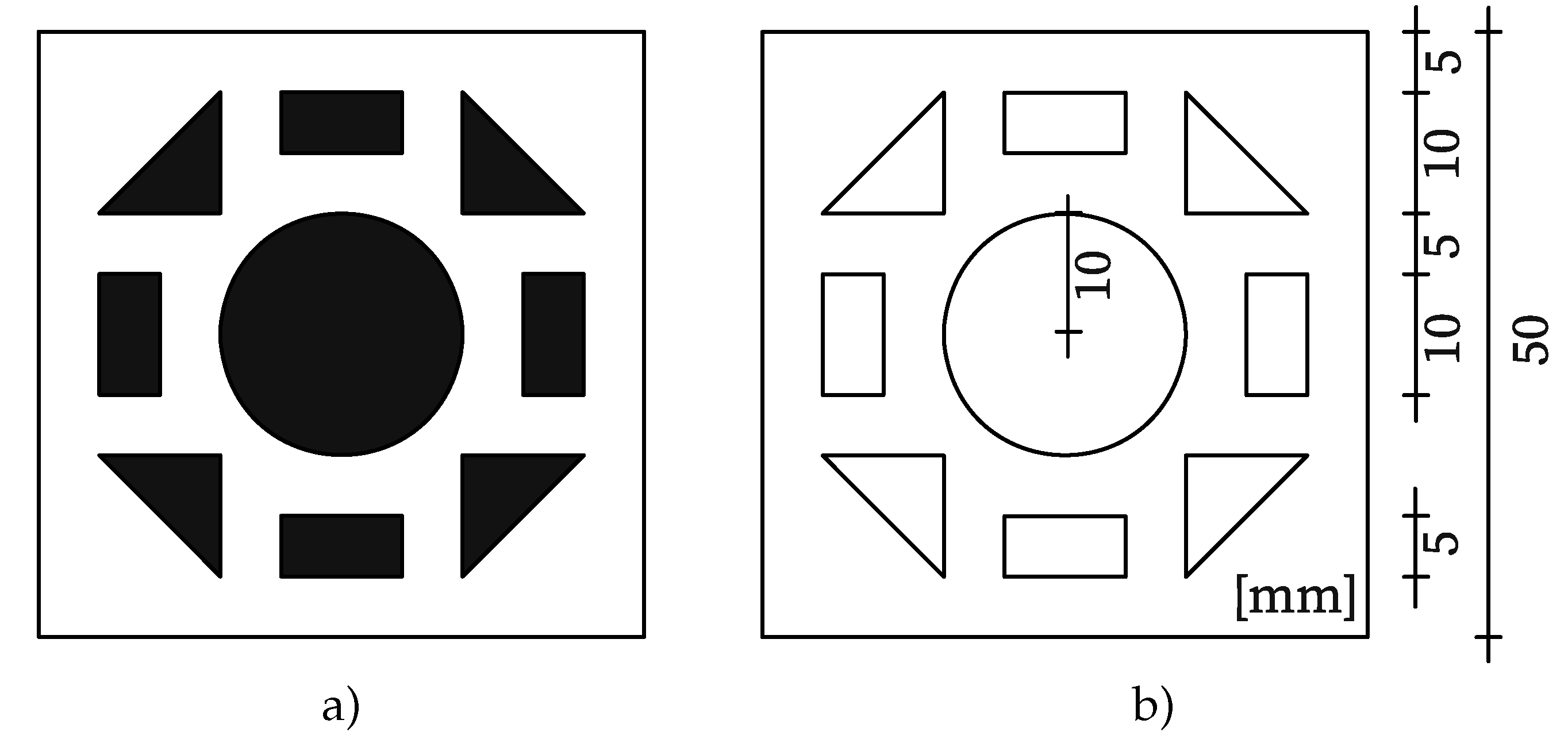

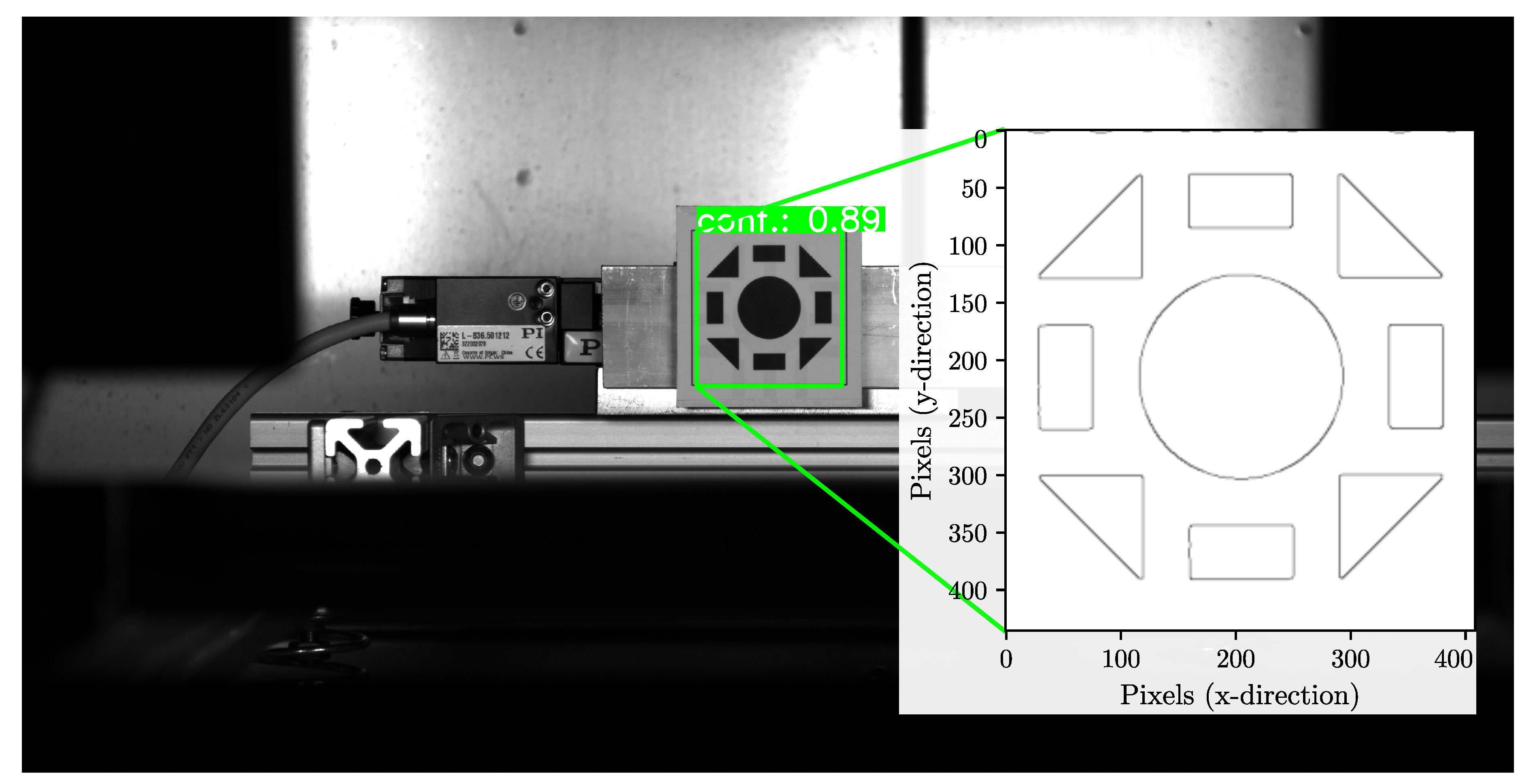

3.1.0.1. Measurement Motive

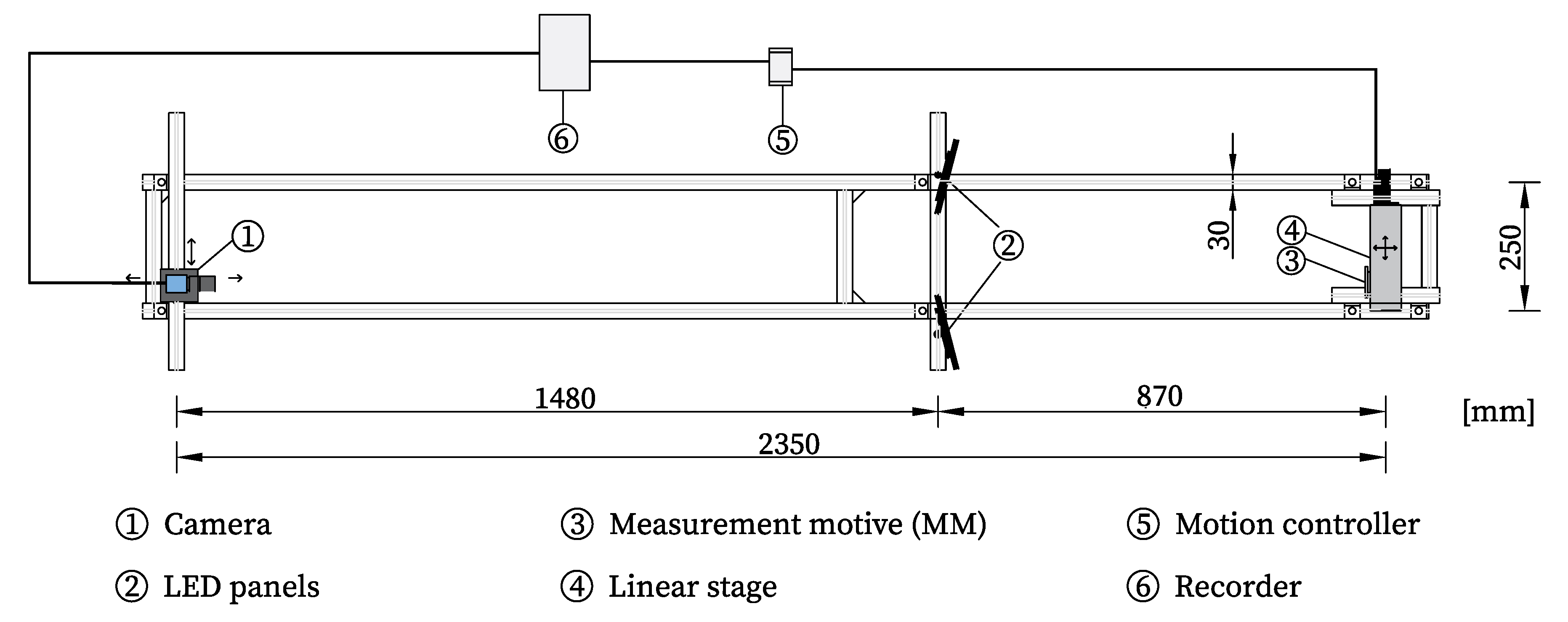

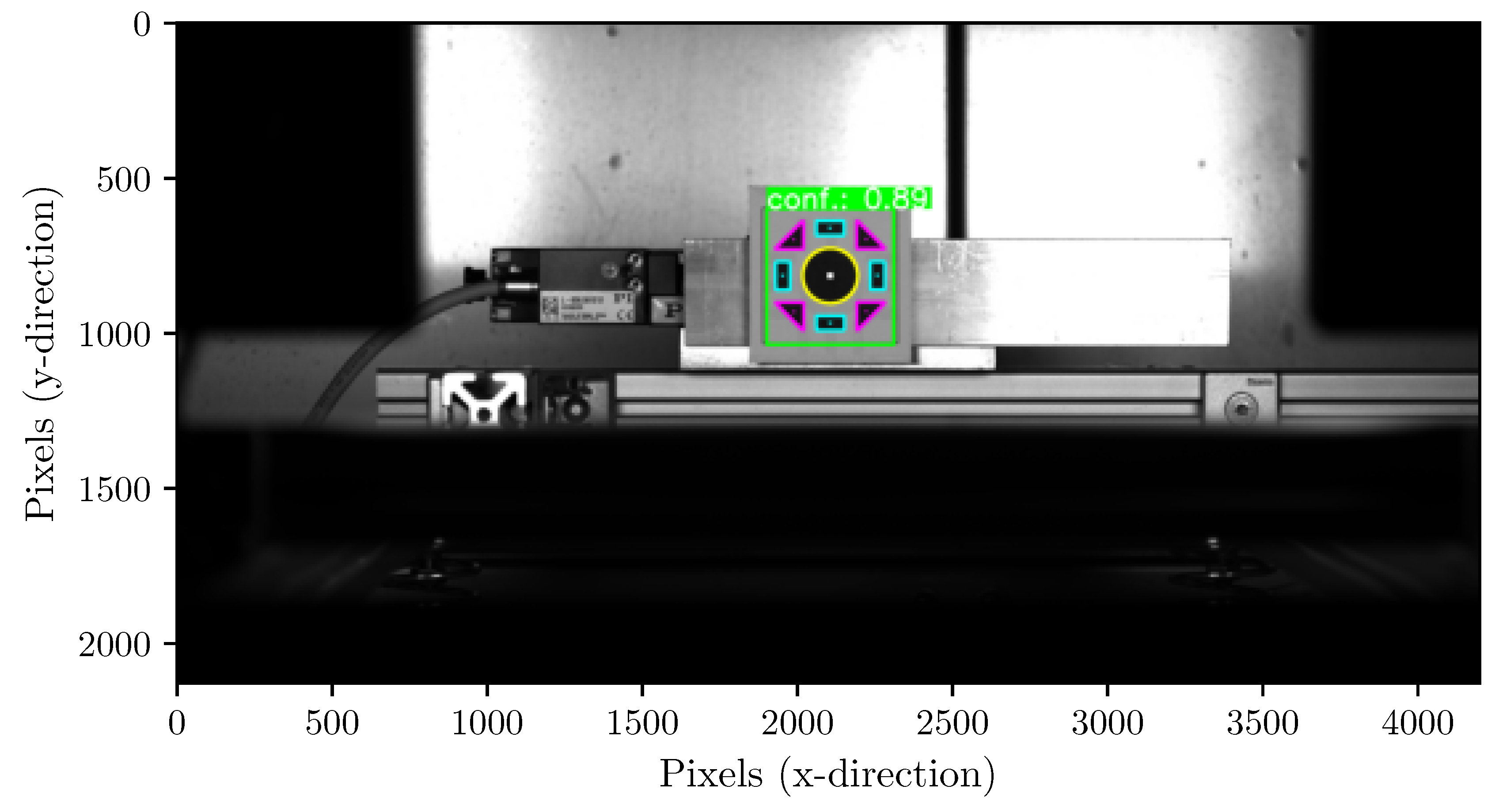

3.1.0.2. Test Setup

3.2. Minimal Implementation of the Algorithm

- ultralytics (8.3.99)

- torch (2.6.0+cu126)

- opencv-python (4.10.0.84)

- numpy (1.26.4)

3.2.0.3. CNN Object Detection

3.2.0.4. ROI Segmentation

- General

- To ignore contours incorrectly detected due to noise, a query was performed considering only contours with a minimum area of 100 pixels. The threshold value should be chosen carefully based on the expected minimum sizes of the geometric shapes.

- Circles

- First, to classify circles, the circumference (P) and area (A) of the contour must be determined. Then, circularity [48], an auxiliary variable, is defined as a parameter. The formula is as follows: . A perfect circle has a circularity of 1. A threshold value can be defined for classification depending on the desired tolerance. In this case, the threshold value was set to 0.85, as this yielded the best results with the setup shown; shapes with values above this threshold are considered circular.

- Polygons

- The OpenCV contour approximation algorithm was used to classify the triangles. The approxPolyDP() function implements the Ramer-Douglas-Peucker algorithm [49,50], which reduces a curve consisting of line segments to a similar curve with fewer points. In this case, the approximation accuracy was defined as 10% of the perimeter. The number of corners can be determined based on the number of remaining approximated lines, which are output as individual arrays. Depending on the chosen approximation accuracy, this algorithm is highly robust. However, for certain applications, other corner detection algorithms may be preferable.

- Area

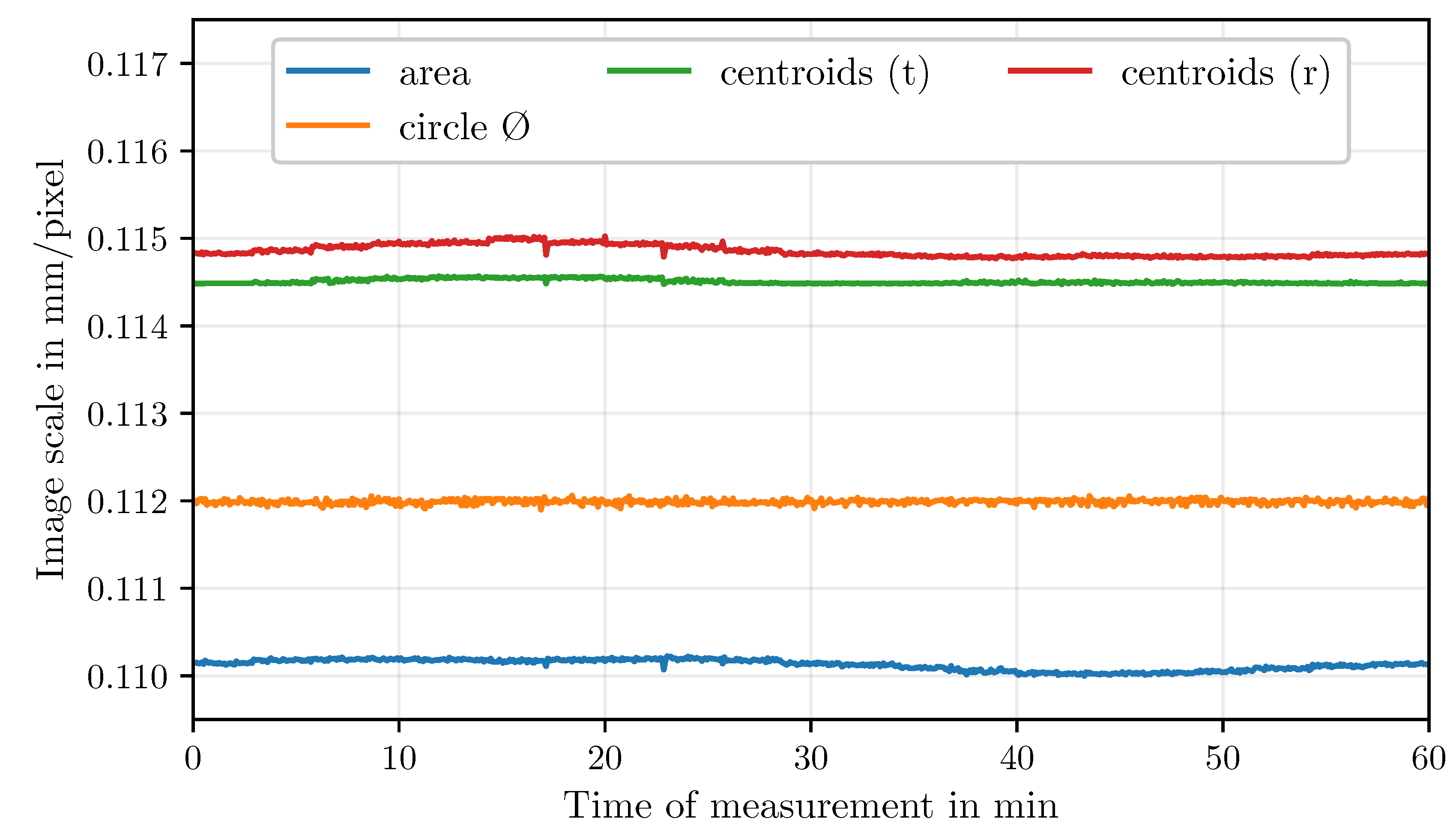

- The easiest way to determine the image scale is to compare the actual size of the geometric shapes on the MM to the size of the enclosed area of the classified contours: .

- Circles

- Circular shapes can be compared based on their circle parameters, such as radius, circumference, or area. In this case, the radius was determined using the OpenCV function minEnclosingCircle() on contours classified as circles. The actual radius is 10.

- Polygons

- In the third approach, the image scaling is determined by comparing the distances between the individual centroid points of the triangles and rectangles. The distances between the centers of gravity of the triangles are 26.667 mm between adjacent elements and 37.712 mm between opposite elements. For the rectangles, the distances are 24.749 mm between adjacent elements and 35 between opposite elements. The overall values for beta were determined using the mean values of all the respective shape ratios.

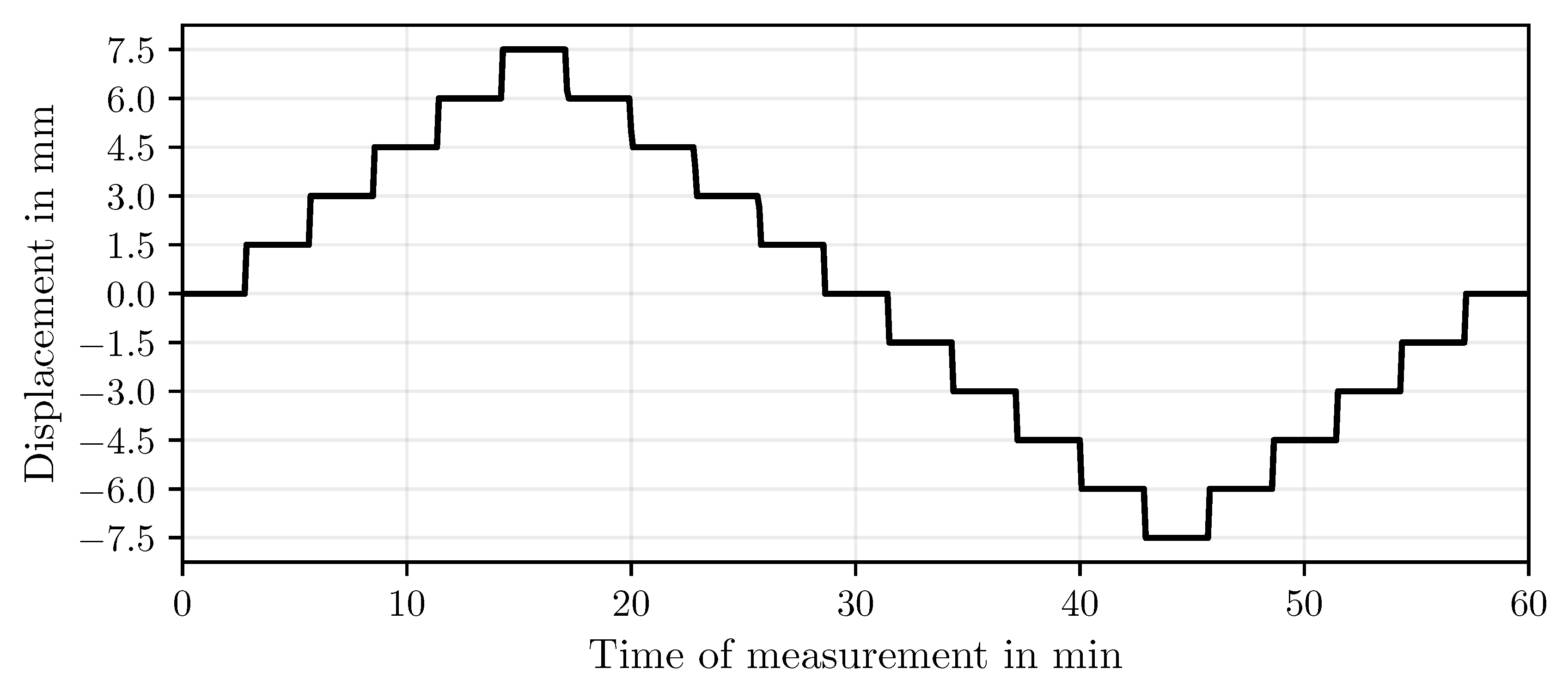

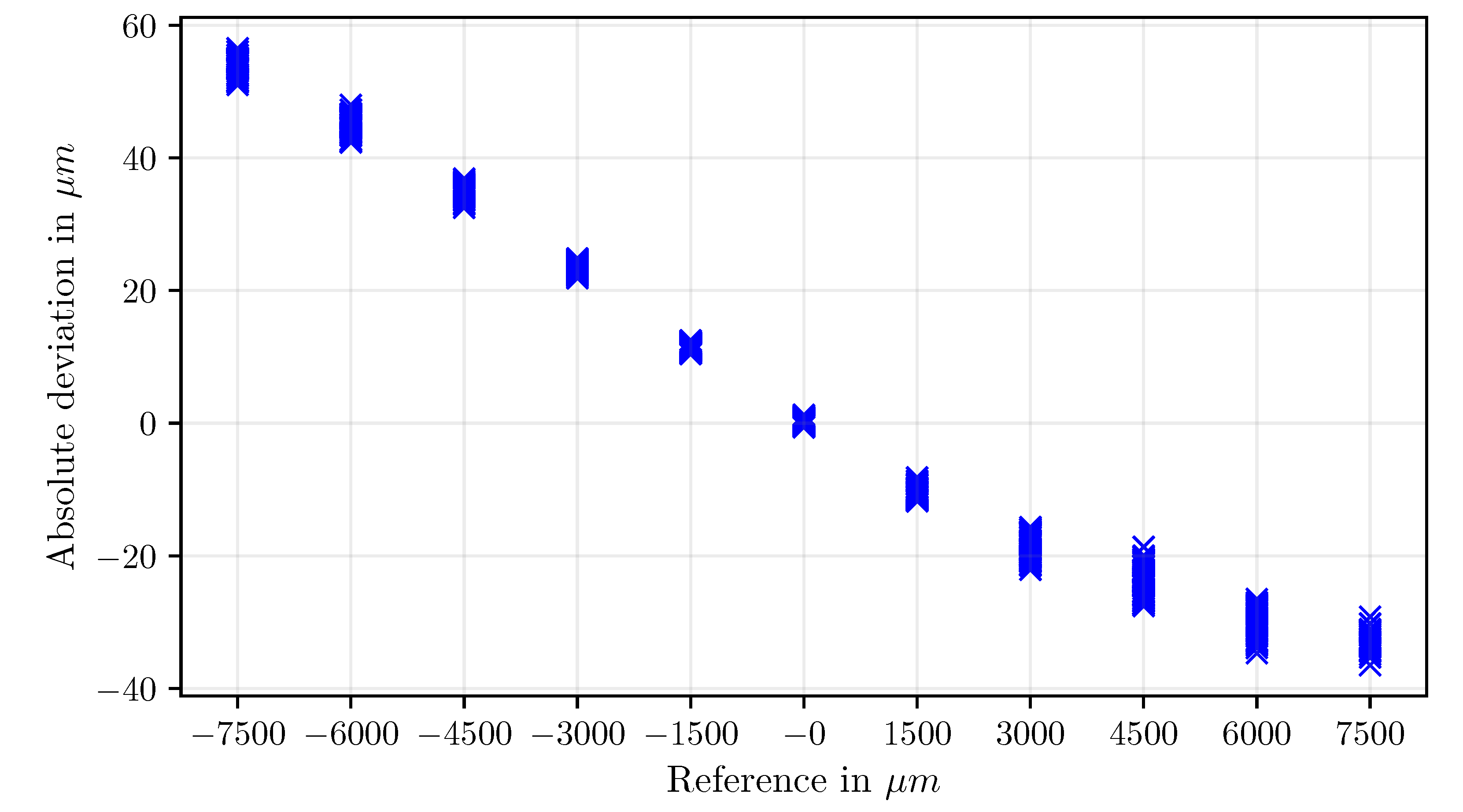

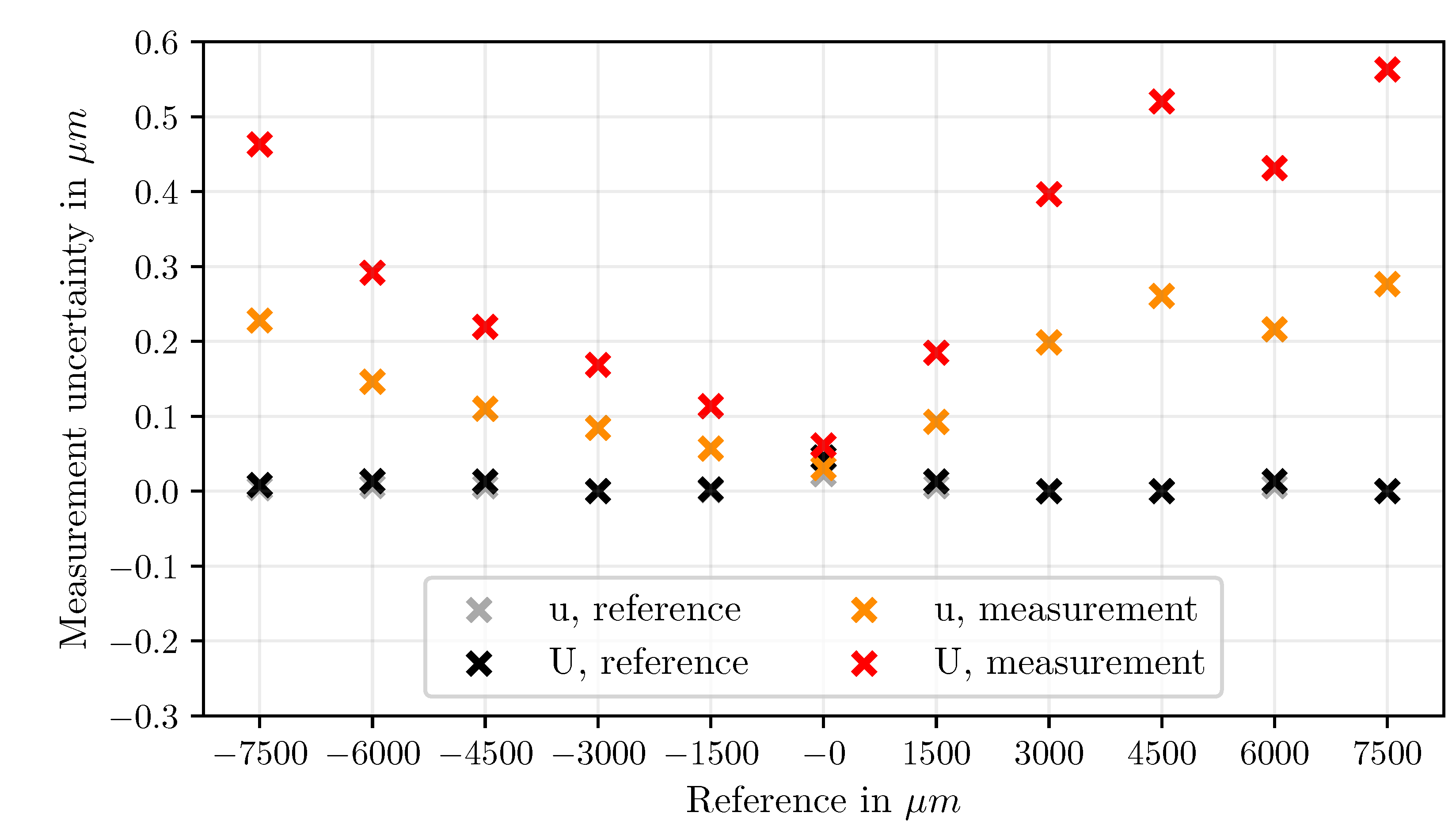

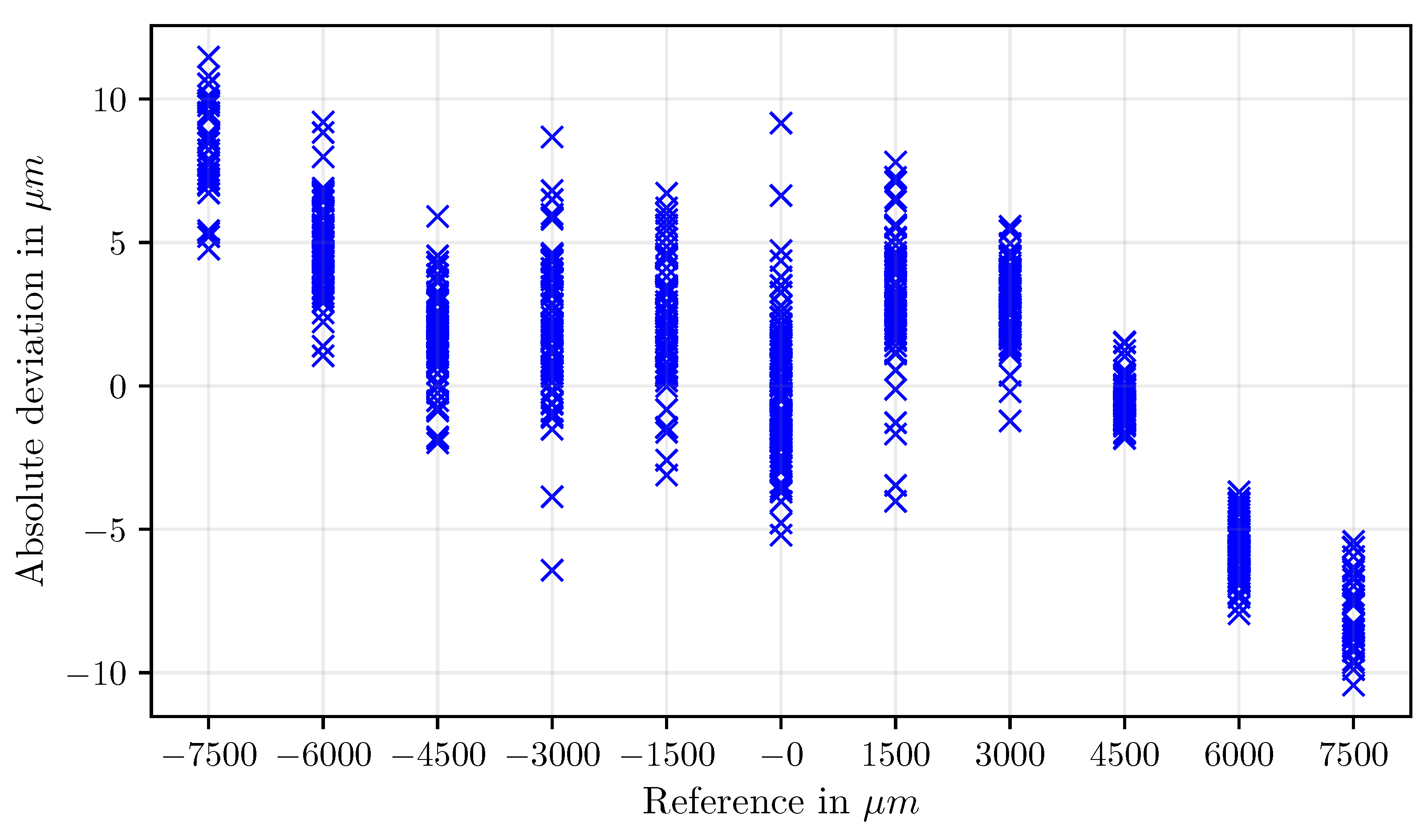

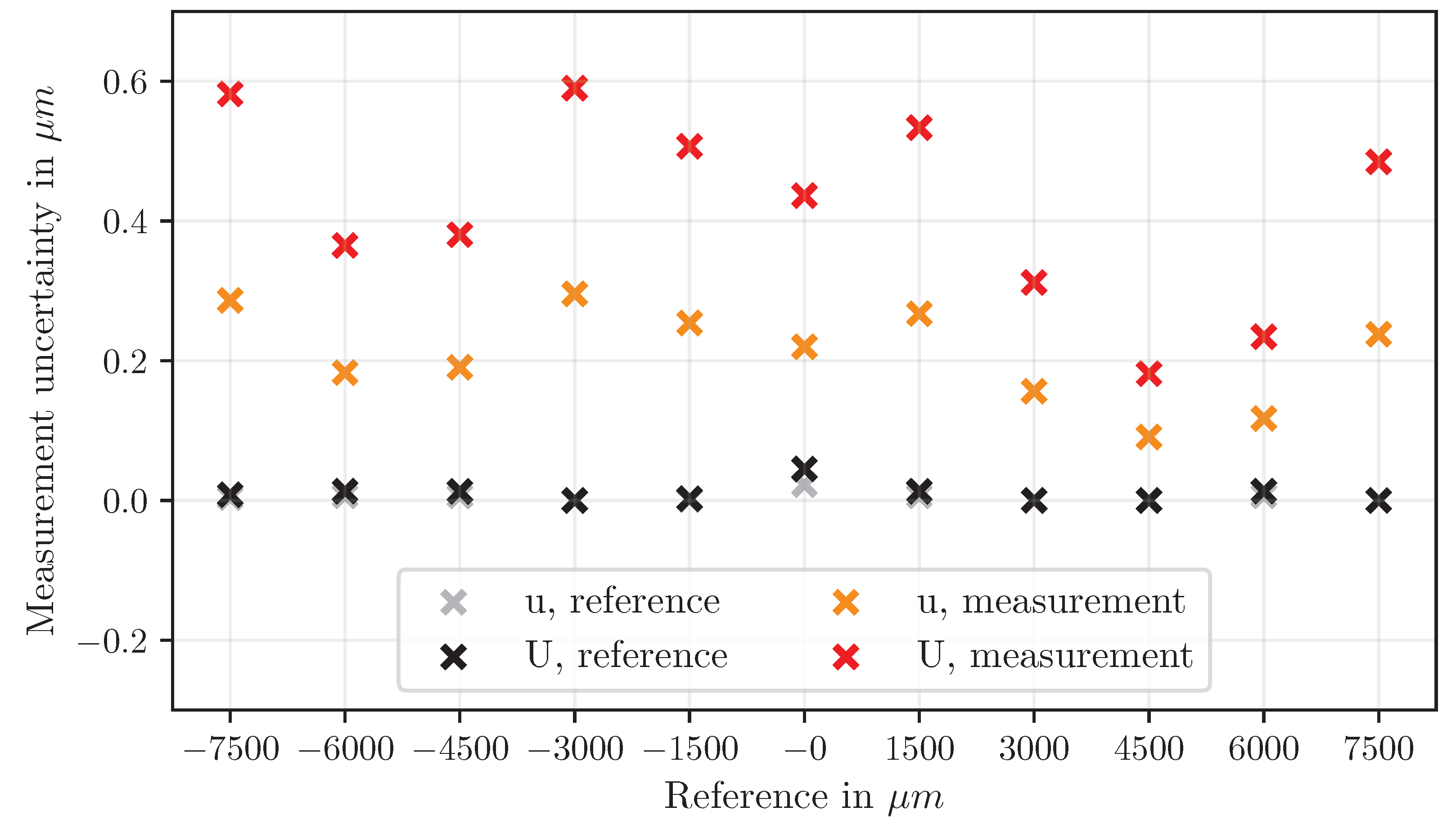

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nithin, T.A. Real-time structural health monitoring: An innovative approach to ensuring the durability and safety of structures. 11, 43. [CrossRef]

- Brownjohn, J. Structural health monitoring of civil infrastructure. 365, 589–622. [CrossRef]

- Aktan, E.; Bartoli, I.; Glišić, B.; Rainieri, C. Lessons from Bridge Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) and Their Implications for the Development of Cyber-Physical Systems. 9, 30. [CrossRef]

- Farrar, C.R.; Worden, K. An introduction to structural health monitoring. 365, 303–315. [CrossRef]

- Rabi, R.R.; Vailati, M.; Monti, G. Effectiveness of Vibration-Based Techniques for Damage Localization and Lifetime Prediction in Structural Health Monitoring of Bridges: A Comprehensive Review. 14, 1183. [CrossRef]

- Anjum, A.; Hrairi, M.; Aabid, A.; Yatim, N.; Ali, M. Civil Structural Health Monitoring and Machine Learning: A Comprehensive Review. 18, 43–59. [CrossRef]

- Laflamme, S.; Ubertini, F.; Di Matteo, A.; Pirrotta, A.; Perry, M.; Fu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Hoang, T.; Glisic, B.; et al. Roadmap on measurement technologies for next generation structural health monitoring systems. 34, 093001. [CrossRef]

- Gharehbaghi, V.R.; Noroozinejad Farsangi, E.; Noori, M.; Yang, T.Y.; Li, S.; Nguyen, A.; Málaga-Chuquitaype, C.; Gardoni, P.; Mirjalili, S. A Critical Review on Structural Health Monitoring: Definitions, Methods, and Perspectives. 29, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, S.; Dackermann, U. A Systematic Review of Optimization Algorithms for Structural Health Monitoring and Optimal Sensor Placement. 23, 3293. [CrossRef]

- Kot, P.; Muradov, M.; Gkantou, M.; Kamaris, G.S.; Hashim, K.; Yeboah, D. Recent Advancements in Non-Destructive Testing Techniques for Structural Health Monitoring. 11, 2750. [CrossRef]

- Palma, P.; Steiger, R. Structural health monitoring of timber structures – Review of available methods and case studies. 248, 118528. [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, J.; Oliveira Costa, C.; Sá da Costa, J. Strain gauges debonding fault detection for structural health monitoring. 25, e2264. [CrossRef]

- Bolandi, H.; Lajnef, N.; Jiao, P.; Barri, K.; Hasni, H.; Alavi, A.H. A Novel Data Reduction Approach for Structural Health Monitoring Systems. 19, 4823. [CrossRef]

- Weisbrich, M.; Holschemacher, K.; Bier, T. Comparison of different fiber coatings for distributed strain measurement in cementitious matrices. 9, 189–197. [CrossRef]

- Scuro, C.; Lamonaca, F.; Porzio, S.; Milani, G.; Olivito, R. Internet of Things (IoT) for masonry structural health monitoring (SHM): Overview and examples of innovative systems. 290, 123092. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Choi, H.W.; Kim, S.K.; Na, W.S. Review of Image-Processing-Based Technology for Structural Health Monitoring of Civil Infrastructures. 10, 93. [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.Z.; Catbas, F.N. A review of computer vision–based structural health monitoring at local and global levels. 20, 692–743. [CrossRef]

- Boursier Niutta, C.; Tridello, A.; Ciardiello, R.; Paolino, D.S. Strain Measurement with Optic Fibers for Structural Health Monitoring of Woven Composites: Comparison with Strain Gauges and Digital Image Correlation Measurements. 23, 9794. [CrossRef]

- Morgenthal, G.; Eick, J.F.; Rau, S.; Taraben, J. Wireless Sensor Networks Composed of Standard Microcomputers and Smartphones for Applications in Structural Health Monitoring. 19, 2070. [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, S.; Lu, Y.; Ng, C.T.; Malinowski, P. Sensor Networks for Structures Health Monitoring: Placement, Implementations, and Challenges—A Review. 4, 551–585. [CrossRef]

- Malik, H.; Khattak, K.S.; Wiqar, T.; Khan, Z.H.; Altamimi, A.B. Low Cost Internet of Things Platform for Structural Health Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2019 22nd International Multitopic Conference (INMIC). IEEE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralovec, C.; Schagerl, M. Review of Structural Health Monitoring Methods Regarding a Multi-Sensor Approach for Damage Assessment of Metal and Composite Structures. 20, 826. [CrossRef]

- Sony, S.; Laventure, S.; Sadhu, A. A literature review of next-generation smart sensing technology in structural health monitoring. 26, e2321. [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Feng, M.; Ozer, E.; Fukuda, Y. A Vision-Based Sensor for Noncontact Structural Displacement Measurement. 15, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, K.; Pawlowski, R.; Schregle, P.; Winter, S. Use of digital image processing in the monitoring of deformations in building structures. 5, 141–152. [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.W.; Dong, C.Z.; Liu, T. A Review of Machine Vision-Based Structural Health Monitoring: Methodologies and Applications. 2016, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Feng, M.Q. Experimental validation of cost-effective vision-based structural health monitoring. 88, 199–211. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Tomizuka, M. OpenSHM: Open Architecture Design of Structural Health Monitoring Software in Wireless Sensor Nodes. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Mechtronic and Embedded Systems and Applications. IEEE; pp. 19–24. [CrossRef]

- Basto, C.; Pela, L.; Chacan, R. Open-source digital technologies for low-cost monitoring of historical constructions. 25, 31–40. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, X.; Yan, F.; Zeng, Z. , Non-Contact Extensometer Deformation Detection via Deep Learning and Edge Feature Analysis. In Design Studies and Intelligence Engineering; IOS Press. [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.F. Foundations of Computer Vision. [CrossRef]

- Aboyomi, D.D.; Daniel, C. A Comparative Analysis of Modern Object Detection Algorithms: YOLO vs. SSD vs. Faster R-CNN. 8, 96–106. [CrossRef]

- Bilous, N.; Malko, V.; Frohme, M.; Nechyporenko, A. Comparison of CNN-Based Architectures for Detection of Different Object Classes. 5, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Chandra, D. Real-time Comparison of Performance Analysis of Various Edge Detection Techniques Based on Imagery Data. 42. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, H.; Yu, M.; Li, Y. Overview of Image Smoothing Algorithms. 1883. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.H.; Tseng, Y.S.; Yin, J.L. Gaussian-Adaptive Bilateral Filter. 27, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreyamsha Kumar, B.K. Image denoising based on gaussian/bilateral filter and its method noise thresholding. 7, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S. Comparison of Various Edge Detection Technique. 9. [CrossRef]

- Magnier, B.; Abdulrahman, H.; Montesinos, P. A Review of Supervised Edge Detection Evaluation Methods and an Objective Comparison of Filtering Gradient Computations Using Hysteresis Thresholds. 4. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Peng, B.; Al-Huda, Z.; Malik, A.; Zhai, D. An overview of edge and object contour detection. 488. [CrossRef]

- Papari, G.; Petkov, N. Edge and line oriented contour detection: State of the art. 29. [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.; Stephens, M. A Combined Corner and Edge Detector. pp. 23.1–23.6. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.; Monzón, N.; Salgado, A. An Analysis and Implementation of the Harris Corner Detector. 8. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J. ; Tomasi. Good features to track. pp. 593–600. [CrossRef]

- Förstner, W.; Gülch, E. A Fast Operator for Detection and Precise Location of Distict Point, Corners and Centres of Circular Features.

- Illingworth, J.; Kittler, J. The Adaptive Hough Transform. PAMI-9. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; be, K. Topological structural analysis of digitized binary images by border following. 30. [CrossRef]

- Montero, R.S.; Bribiesca, E. State of the Art of Compactness and Circularity Measures. 2009.

- Ramer, U. An iterative procedure for the polygonal approximation of plane curves. 1. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, D.H.; Peucker, T.K. Algorithms for the Reduction of the Number of Points Required to Represent a Digitized Line or its Caricature. pp. 15–28. [CrossRef]

| a) | b) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).