1. Introduction

Cellulose has attractive ecological properties with high stiffness and strength at low weight [

1]. The mechanical properties of cellulose-based materials such as wood are highly affected by their density. The densification improves the homogeneity of the material and absolute mechanical properties. The regenerated cellulose is basically different from natural fibers in terms of structure and properties. Fibers are partially crystalline (cellulose II) and highly oriented, with the degree of orientation higher in the external surface relative to the core of the fiber. The highly oriented cellulose nanofibrils (CNF) show tensile strength of 576±54 MPa and stiffness of 32.3±5.7 GPa. The regenerated cellulose fibers are highly extensible, with a failure strain between 8.0% and 25% compared to natural fibers that ideally fail at 1.0-2.0% strain due to the relatively high proportion of non-crystalline cellulose [

2,

3]. The regenerated cellulose fibers have good performance in terms of work to fracture, making them a suitable option for composite applications where high fracture toughness is needed [

4]. For instance, the regenerated cellulose fiber of lyocell has a tensile strength of 556±78 MPa and elongation at break of 8.7±1.6% [

5].

The cellulose fibers significantly increase tensile modulus, tensile strength, flexural modulus and strength, fracture toughness, elongation at break, and impact toughness of epoxy [

6,

7,

8,

9]. The CNF at 0.1 wt.% increases the tensile strength of epoxy by 6.45% [

10]. The stiffness, strength, and fracture toughness of epoxy/cellulose composite can be significantly improved by controlling the porosity and fiber volume of cellulose fiber [

11]. The cellulose long filaments improve the flexural modulus and flexural strength of biobased vanillin epoxy resin significantly by 135.1% and 542.8%, respectively [

12]. The cellulose fibers at high fiber content have better interfacial bonding with epoxy matrix [

13]. Increasing the content of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) increases the strength, elongation at break, and stiffness of epoxy. The particles of MCC arrest the cracks propagating within the epoxy matrix, which improves the fracture energy of the epoxy composites [

14]. Incorporating 18-23 weight fraction (wt.%) of CNF into epoxy nanocomposites noticeably increases their mechanical properties [

15]. Reinforcing epoxy with 20-36 wt.% of CNF doubles the tensile strength and modulus of the resulting composites [

16]. Adding 13 volume fraction (vol.%) of CNF to bioepoxy increases the storage modulus from 2.8 to 4.2 GPa and strength from 89 MPa to 107 MPa [

17].

The cellulose nanofillers of CNF can be utilized to mitigate the adverse impact of moisture on the epoxy nanocomposites. CNF can be blended with graphene oxide to develop high-humidity sensing filament. The humidity-sensing behavior of the developed filament is observed by the resistivity changes in different humidity and temperature levels [

18]. The presence of high aspect ratio and high crystalline CNF at 23 wt.% mitigates the water vapor permeability of pure epoxy resin by more than 50% [

15]. The surface of regenerated cellulose fiber is highly polar due to abundant hydroxyl groups that interact with the surrounding atmosphere, enabling the fiber to adsorb water. The interfacial bonding between cellulose fiber and epoxy is considerably degraded when the fiber absorbs moisture from the humid environment, leading to a reduction in the mechanical properties of the epoxy/cellulose composite. The moisture absorption of cellulose fiber reduces the fracture toughness, flexural strength, and modulus of epoxy/cellulose composite. The use of an appropriate coupling agent is necessary to improve the interfacial adhesion between regenerated cellulose fibers and the non-polar matrix of epoxy. The cellulose reinforcements can be chemically modified using their hydroxyl groups, enabling different methods for surface chemical modification [

2,

7,

19].

APTES is one of the most important linkers used for cellulose functionalization [

20]. The surface of cellulose nanofillers such as cellulose nanocrystal (CNC) can be silylated firstly by hydrolyzing APTES in water and then adsorbing it onto CNC via hydrogen bonds; finally, the surface of CNC is covalently linked to the chain hydrocarbon through Si-O-C bonds, which formed via the condensation reaction between silanol groups and hydroxyl [

21,

22]. The tensile strength of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) composite reinforced with 1.0 wt.% of silylated CNF is more than twice that of neat PMMA resin [

23]. The bamboo cellulose fibers treated with silane coupling agent improve the elongation at break and tensile strength of epoxy/cellulose composite by 53%, and 71%, respectively, relative to its untreated counterpart. The improvement in the mechanical properties of epoxy/cellulose composite with silane treatment can be attributed to the formation of covalent bonds that link the epoxy and the cellulose, improving their interfacial interactions [

24]. The epoxy resin is modified with 3 wt.% of APTES to enhance the tensile properties of viscose fabric composite. The elongation at break and tensile strength of the viscose fabric composites synthesized from modified resin are increased up to 14 and 41, respectively. The enhancement in the tensile properties is justified by the improved interfacial adhesion between viscose fabric and epoxy after the resin modification [

25]. The viscose fabric composite synthesized from epoxy modified with 5 wt.% of APTES shows a twofold increase in toughness relative to the raw composite. Modifying the epoxy resin by APTES is considered a better option when taking into account low energy consumption and less process waste relative to wet chemical functionalization methods such as acetylation and alkali treatments [

26].

In the published literature, the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is used to investigate the effect of chemical functionalization on the durability and the interfacial behavior of cellulose nanofiber-reinforced epoxy nanocomposites under salt and aqueous environments. The cellulose chain is functionalized by adding carboxyl groups to the surface of cellulose nanofiber [

27]. However, the reactive MD simulation has not been implemented yet to evaluate the effect of silylation treatment on the mechanical properties of cellulose-reinforced epoxy composite. Additionally, the capability of silylation in improving the mechanical properties of epoxy composites at high weight fractions of cellulose is not addressed in the previously published studies. This study covers this research gap by using the reactive MD simulation to characterize the effect of improved interfacial adhesion at the silylated cellulose/epoxy interface on the mechanical properties of epoxy composites. The epoxy thermoset is reinforced with raw and silylated cellulose at different loadings of 28.1 wt.% and 43.9 wt.%. The computational models based on MD simulation are prepared for 10 raw cellulose chains, 20 raw cellulose chains, 10 silylated cellulose chains, and 20 silylated cellulose chains, which are used as reinforcements for epoxy thermoset.

The content of this paper is arranged in four parts. The details of the main elements used to assemble the epoxy/cellulose composites are provided in

Section 2, including the introduction of the methods of molecular modeling performed. Then, the effect of silylation treatment and loading of cellulose on improving the tensile properties of epoxy composites is discussed in

Section 3. The main findings of this paper are summarized in

Section 4.

2. Materials and Methods

Molecular modeling constitutes an effective approach to characterizing the impact of silylated cellulose on the tensile properties of epoxy composites. Details on the type of ensembles and forcefields used for the equilibrium of the molecular models and the characterization of stress-strain response are discussed in sub

Section 2.1. The hydrolyzed APTES is used to modify the epoxy thermoset and the silylation of cellulose. The details of the epoxy functionalization process and the implementation of silylated cellulose as a reinforcement for epoxy composites are discussed in sub

Section 2.2. The cellulose reinforcements composed of 10 raw cellulose chains, 20 raw cellulose chains, 10 silylated cellulose chains, and 20 silylated cellulose chains are compared in terms of the highest enhancement that can be attained in the tensile strength and modulus of epoxy thermoset. Then, the stress-strain response for raw cellulose-reinforced epoxy is chosen as a baseline to evaluate the enhancements in the mechanical properties of epoxy/cellulose composites achieved by silylation treatment.

2.1. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

The open-source software of the large-scale atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator (LAMMPS) is implemented for MD simulations [

28]. The MD simulations are used to evaluate the stress-strain response of epoxy/cellulose composites deformed under uniaxial tensile loading. The polymer consistent forcefield (PCFF) and its addendum (PCFF+) obtained from MedeA software [

29] are used to describe the bond and non-bond interactions in silylated cellulose and epoxy based on parameters retrieved from ab initio calculations. The valence forcefield of PCFF/PCFF+ contains predefined bonds, angles, and torsions for organic and inorganic materials. However, the PCFF/PCFF+ can not be implemented to describe the breaking of nanocovalent bonds between atoms taking place under the tensile load. Hence, the reax forcefield (ReaxFF) is used to evaluate the tensile strength of epoxy/cellulose composites considered in this study. The parameters of ReaxFF describing the atomic interaction between epoxy and cellulose are retrieved from [

30] and [

31].

The ReaxFF can be described as a general bond-order-dependent force field offering precise descriptions of bond breaking and bond formation during MD simulations. The reaxFF divides the total system energy (

) into contributions from different partial energy terms, as demonstrated in the following expression:

These partial energies contain

: bond energy,

and

: atom under/over coordination,

: valence angle,

: penalty energy,

: torsion angle,

: conjugation energy to correctly handle the nature of preferred configurations of atomic and resulting molecular orbitals,

and

are terms to handle Coulomb-van der Waals interactions. The recent non-bonded interactions are evaluated between every atom pair, regardless of connectivity, and they are shielded to prevent extreme repulsion at short distances [

32].

For every molecular system considered, 6 replicates with various initial atomic configurations are generated to enhance statistics of the evaluated mechanical properties [

33]. Therefore, six separate models of epoxy, raw cellulose, and epoxy/cellulose composites are built and relaxed according to the steps of the equilibrium protocol shown in

Figure 1.

The tensile modulus and strength are two critical strength indicators in a plastic material that illustrate the mechanical behavior of a material under tensile load [

34]. The tensile properties of the epoxy/cellulose composites are evaluated based on the Voigt model using the elastic constants matrix [

35,

36]. The tensile strength and modulus of raw cellulose and epoxy are evaluated to verify the capability of the PCFF/PCFF+ and ReaxFF in predicting the mechanical properties of epoxy/cellulose composites. The tensile strength of raw cellulose and epoxy in the longitudinal direction is evaluated using the tensile stress-strain responses shown in

Figure 2. According to

Figure 2(fig23), the tensile strength values of cellulose are 566.2 MPa and 580.9 MPa, evaluated based on PCFF/PCFF+ and ReaxFF, respectively. These values are close to each other and comparable to the experimental tensile strength of CNF (576±54 MPa) and lyocell fiber (556±78) reported in the literature [

2,

5,

33]. It is noteworthy that the stress-strain responses of cellulose evaluated based on PCFF/PCFF+ and ReaxFF differ in terms of strain values at ultimate tensile strength due to the high proportion of crystalline regions in the molecular models of PCFF/PCFF+ compared to their counterparts of ReaxFF. The yield of cellulose is observed at around 7-8% strain in the molecular models built for ReaxFF due to the disruption of hydrogen bonds among the cellulose chain segments and high proportion of amorphous regions [

37].

According to

Figure 2(fig24), the tensile strength values of epoxy are 119.3 MPa and 187.1 MPa, predicted based on PCFF/PCFF+ and ReaxFF, respectively. These values are justified for epoxy partially crosslinked with hydrolyzed APTES at 6.6 wt.%. The APTES molecules improve the structural integrity of epoxy by forming additional bonds via their silane (Si-OH) and amine (NH

2) ends, linking the molecular groups of triethylenetetramine (TETA)/diglycidyl ether bisphenol-F (DGEB-F) together as demonstrated in

Figure 3. Furthermore, the tensile strength of epoxy crosslinked with similar functional groups can reach the value of 190 MPa [

38]. Ideally, the values of tensile strength should be in the range between 200 and 400 MPa for the vast majority of thermosets. Indeed, these values represent the upper theoretical limitation for the experimentally reported strength. The theoretical strength of epoxy is determined to be 275 MPa, while its maximum true strength value is 166 MPa, evaluated using microtensile tests. The tensile strength of epoxy reported at the microlevel is much higher than the strength retrieved by standard test techniques of 104 MPa. Therefore, the tensile strength of epoxy can reach its theoretical strength value at minimal scales at micro and nano levels [

39].

The tensile modulus values of epoxy and raw cellulose evaluated based on PCFF/PCFF+ are 3.3 GPa and 13.3 GPa, respectively. These values are in good agreement with previously reported values for epoxy and raw cellulose of 3.3 GPa [

40] and 13.5 GPa [

41], respectively. Based on the results of the MD simulation used to evaluate the properties of raw cellulose and epoxy, the forcefields of PCFF/PCFF+ and ReaxFF can effectively predict the tensile properties of these materials with good accuracy. Therefore, PCFF/PCFF+ is used to evaluate the tensile modulus, while ReaxFF is used to evaluate the tensile strength of the epoxy/cellulose composites. The molecular modeling is conducted using the Schrödinger software developed by D.E. Shaw Research (NY, USA) [

42]. All molecular models have a constant initial density of 0.60 g/cm

3.

The conjugate gradient method is used to minimize the potential energy of the molecular systems [

43]. The initial minimization stage’s energy, force tolerances, maximum iterations, and force evaluations are set to 0.0,

, 10000, and 15000, respectively. The tensile stress-strain responses are evaluated under volume-conserving uniaxial strain at room temperature (300K) by running nonequilibrium MD simulations based on PCFF/PCFF+ and ReaxFF force fields in the NVT ensemble using the Nose-Hoover thermostat. The simulation cell is elongated in the longitudinal direction in small increments of

= 0.002 at every time step. The time duration for each nonequilibrium NVT ensemble is 5.0 picoseconds with a time step size

t of 0.5 femtoseconds.

2.2. Reinforcing Epoxy with Silylated Cellulose

The cellulose considered in this study is not completely amorphous and contains a large proportion of crystalline regions in its structure. Therefore, the cellulose chains are generated with a backbone dihedral of 180

o with a polymerization degree of 10. Then, the chains of cellulose are packed similarly to the ones shown in

Figure 2(fig21). After applying the equilibrium protocol to the packed chains, the cellulose chain includes amorphous and crystalline regions. The molecules in the amorphous region are irregularly arranged with large voids, while the molecules in the crystalline region are arranged tightly and neatly. There is no obvious division between the amorphous and crystalline regions in the cellulose chain, and it is a gradual transition state [

44].

The silylation treatment is applied on epoxy/cellulose composites using APTES. The APTES molecules are used as a hardening agent along with TETA to crosslink the monomers of DGEB-F using their amine ends. Then, the crosslinked APTES/TETA/DGEB-F epoxy is hydrolyzed in water to generate highly reactive Si-OH groups at APTES molecules. The silane ends of hydrolyzed APTES molecules form covalent bonds between each other, improving the interfacial adhesion among the molecular groups of TETA/DGEB-F. When the hydrolysis of APTES is followed by condensation, the hydrolyzed molecules of APTES in the epoxy matrix act as silane coupling agents, linking cellulose to epoxy through the bonds formed between their silane ends and hydroxyl groups of cellulose. The APTES molecules are attached to the cellulose through condensation with hydroxyl groups. The hydrolyzed APTES molecules have covalent bonds with cellulose through Si-O-C. These molecules can attach to the cellulose substrate through the silane end via Si-O-C bonds or the amine end through NH

2-OH-C via hydrogen bonds [

45]. The dual function of hydrolyzed APTES as a crosslinker for DGEB-F monomers and as a silane coupling agent for cellulose is clarified in

Figure 3.

The molecular models of epoxy/cellulose composites are generated by adding 20 molecules of hydrolyzed APTES to 30 molecules of TETA and 110 molecules of DGEB-F. The molecules of epoxy matrix (APTES/TETA/DGEB-F) are used to pack cells containing 10 and 20 cellulose chains. The open-source software of Packmol is used to pack the initial molecular models of epoxy/cellulose composites [

46].

Figure 4 shows the initial configuration of molecular models used for MD simulations of epoxy/cellulose composites. The equilibrium protocol followed in this study includes two stages to eliminate the voids from the molecular models prior to and after the crosslinking process. The molecular models are compressed by applying the first stage of the equilibrium protocol. Then, the epoxy matrix is crosslinked first with crosslinking saturation of 50% applied to DGEB-F monomers. The amine ends of hydrolyzed KH550 are crosslinked with the monomers of DGEB-F. If the epoxy matrix is reinforced with raw cellulose, then the hydrogen non-covalent bonds are considered at the interface between cellulose and epoxy. However, in epoxy/silylated cellulose composites, the silane coupling agents of APTES form covalent bonds with cellulose through their silane ends on one side and connect the silylated cellulose to DGEB-F through their amine ends on the other side. After the crosslinking process is finished for epoxy and cellulose, the second stage of the equilibrium protocol is carried out to eliminate the voids generated due to the formation of bonds between molecules.

The exact molecular formulas of cellulose, epoxy, and epoxy/cellulose composites, along with the composition of their matrices and the atomic weight fraction (wt.%) of cellulose used to reinforce epoxy, are clarified in

Table 1. When the content of cellulose is increased from 28.1 to 43.9 wt.%, the loading of hydrolyzed APTES is reduced from 4.8 wt.% to 3.7 wt.%. In the epoxy composite with 28.1 wt.% of silylated cellulose, each cellulose chain is attached to two APTES molecules, but in the composite with 43.9 wt.% of silylated cellulose, each cellulose chain is only attached to one APTES molecule. Therefore, the improvements in mechanical properties obtained from using the silylation treatment in epoxy/43.9 wt.% cellulose are lower compared to those of epoxy/28.1 wt.% cellulose.

3. Results and Discussion

Based on the results of the MD simulation, the silylated cellulose reinforcement, which is composed of 20 silylated cellulose chains, has the highest improvement effect on the tensile modulus and strength of epoxy composites compared to other reinforcements of cellulose. Hence, the silylation of cellulose should be combined with homogeneous dispersion and sufficient loading of cellulose reinforcements in the epoxy matrix to obtain the highest possible increase in the tensile properties of the resulting composites. The reinforcing effect of cellulose at different loadings on the mechanical properties of epoxy composites is discussed in

Section 3.1, while the impact of silylation on improving the interfacial adhesion of cellulose with epoxy is analyzed in

Section 3.2.

3.1. The Structural Reinforcing Effect of Cellulose at High Loadings

According to the tensile properties listed in

Table 2, the cellulose reinforcement has competitive tensile modulus and strength properties of 13.3 GPa and 580.9 MPa, respectively. These properties are comparable to those of cotton fibers, which have the tensile strength of 287-597 MPa and elastic modulus of 5.5-12.6 GPa [

47]. The epoxy thermoset modified with KH550 has an elastic modulus of 3.3 GPa and tensile strength of 187.1 MPa. The introduction of silanol groups to the chemical structure of epoxy increases its density and improves its tensile strength, while it has a minor effect on its stiffness. The epoxy resin has an ideal density of 1.14 g/cm

3 and an elastic modulus in the range of 3.30-3.49 GPa [

27]. Most of the published studies enhance the mechanical properties of epoxy thermosets by modifying their chemical structure or using reinforcements characterized by superior mechanical performance. However, the chemical fictionalization of epoxy does not improve all of its material aspects, such as tensile strength, stiffness, toughness, and impact strength. Nevertheless, some of these properties are improved after modifying the chemical structure of epoxy, while the others are reduced with chemical functionalization. Furthermore, the chemical functionalization techniques of epoxy have an environmental impact that cannot be avoided [

48,

49,

50].

Reinforcing epoxy with cellulose enhances its tensile strength, elastic modulus, and shear modulus. For instance, the raw cellulose at 28.1 wt.% improves the tensile strength, elastic modulus, and shear modulus of epoxy by 31.80%, 40.20%, and 42.82%, respectively. Increasing the content of raw cellulose from 28.1 wt.% to 43.9 wt.% would enhance the tensile strength, elastic modulus, and shear modulus of neat epoxy by 54.20%, 77.33%, and 84.15%, respectively. These improvements can only be realized if the cellulose reinforcements are uniformly dispersed in the epoxy matrix. These observations are in line with the outcomes of the previously published studies. The mechanical properties of epoxy are increased with increasing content of cellulose. The highest improvement in the mechanical properties of epoxy can be attained with a cellulose fiber content of 46 wt.% [

19]. The elastic modulus and ultimate strength properties of epoxy reinforced with 21 wt.% of nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC) are increased by 180.95% and 240.63%, respectively, relative to the properties of neat epoxy. Increasing the content of NFC from 21 to 58 wt.% in epoxy composite would add further enhancement to ultimate strength and elastic modulus of 48.62% and 66.10%, respectively [

51].

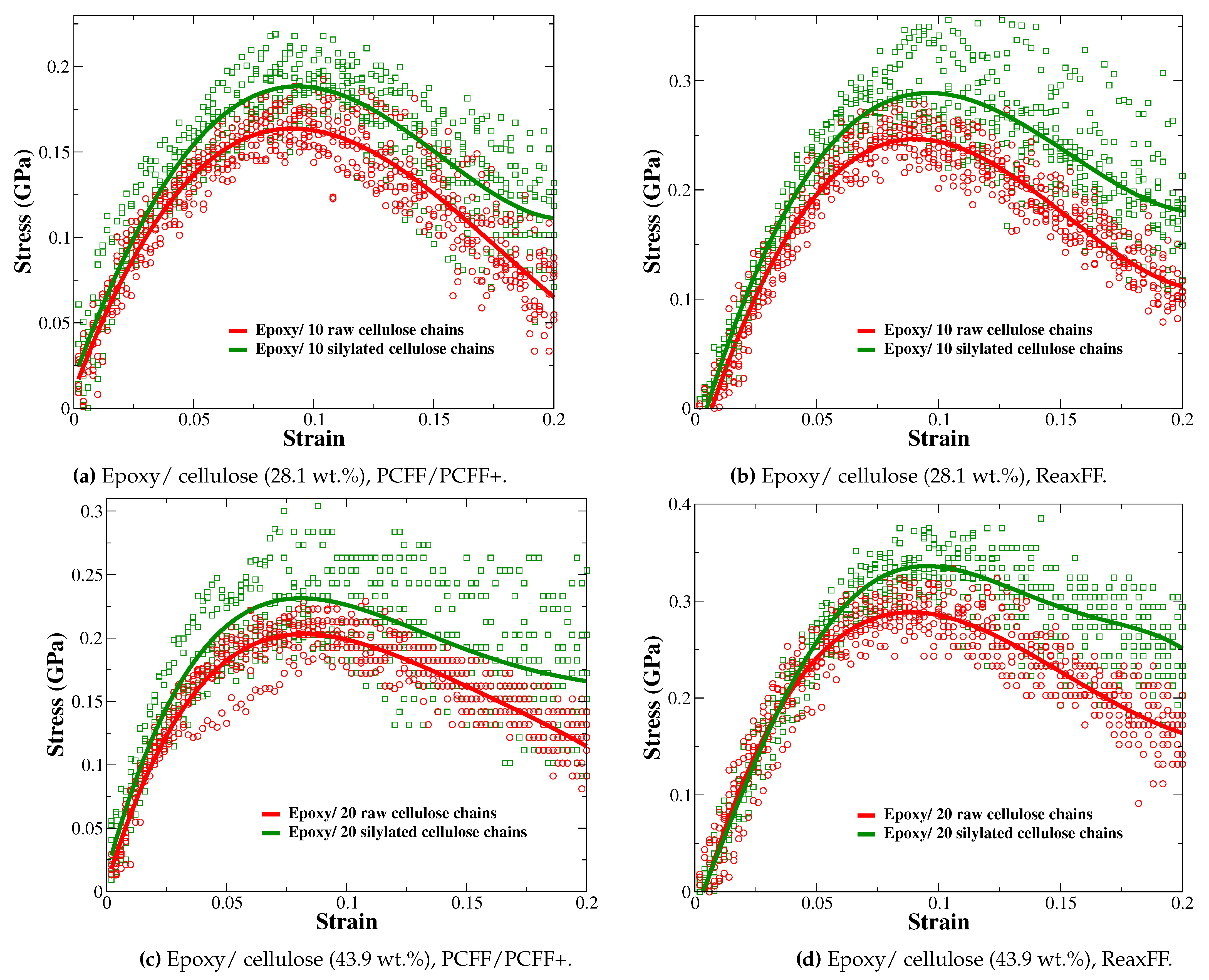

3.2. The Silylation Effect of Cellulose Reinforcements

The tensile properties of epoxy/cellulose composite are increased with increasing content of cellulose. However, increasing the loading of cellulose beyond 40 wt.% in epoxy composites leads to the deterioration of the interfacial adhesion between cellulose fiber and epoxy, which adversely affects the tensile strength of epoxy composites [

52]. Therefore, we apply the silylation treatment to enhance the interfacial adhesion between cellulose and epoxy. The enhanced interfacial adhesion at the epoxy/cellulose interface introduces significant improvements in the tensile strength and modulus of epoxy composites. Referring to

Figure 5, the silylated cellulose at loadings of 28.1 wt.% and 43.9 wt.% improves the ultimate tensile strength of epoxy by 54.36% and 79.64%, respectively. The silylation treatment of cellulose has the highest improvement effect on the tensile strength of epoxy composites compared to other properties such as elastic and shear moduli. The tensile strength of epoxy reinforced with 28.1 wt.% of silylated cellulose (288.8 MPa) is equivalent to the strength of epoxy composite reinforced with 43.9 wt.% of raw cellulose (288.5 MPa), as demonstrated by stress-strain responses in

Figure 5(fig52) and

Figure 5(fig54).

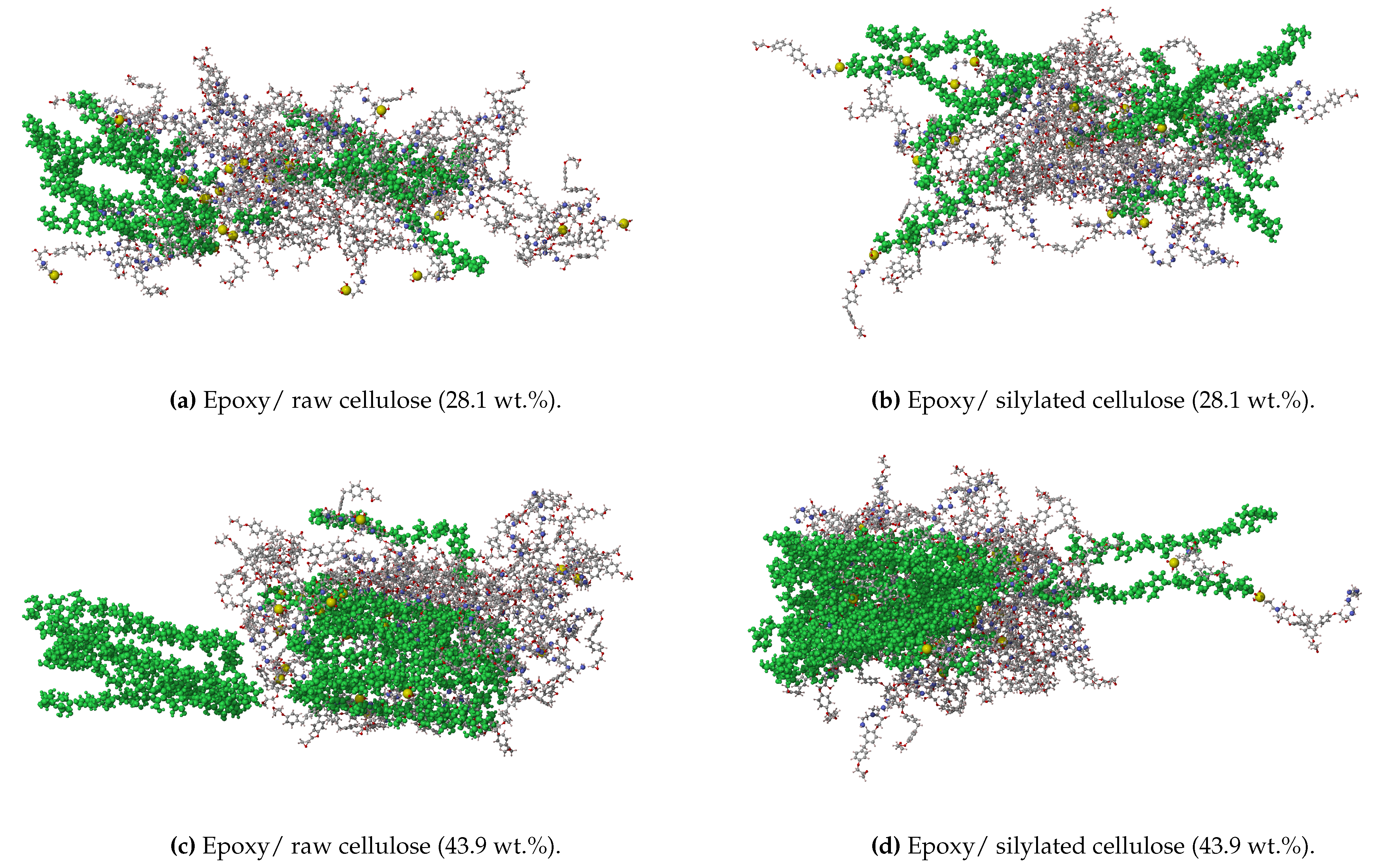

Figure 6 shows the fractured epoxy/cellulose composites retrieved from reactive MD simulations. The epoxy composite reinforced with raw cellulose at 28.1 wt.% shown in

Figure 6(fig61) is completely damaged under the effect of the tensile load, while its counterpart reinforced with 28.1 wt.% of silylated cellulose shown in

Figure 6(fig62) exhibits noticeable resistance to the damaging tensile load. The same conclusion can be drawn from the epoxy composite reinforced with raw cellulose at 43.9 wt.% clarified in

Figure 6(fig63) and its counterpart reinforced with silylated cellulose at 43.9 wt.% illustrated by

Figure 6(fig64). The structural integrity of raw cellulose shown in

Figure 6(fig63) is highly affected upon the application of the tensile load, indicating that there is a poor load transfer between raw cellulose and epoxy due to weak interfacial adhesion at the epoxy/cellulose interface.

Increasing the content of cellulose reinforcements should be associated with the application of silylation treatment to introduce comprehensive improvements in the tensile properties of epoxy/cellulose composites. The increasing content of cellulose in epoxy/cellulose composites increases their elastic and shear moduli, while the silylation treatment increases their tensile strength due to the improved adhesion at the epoxy/cellulose interface.

4. Conclusions

Epoxy is the most frequently used thermoset in the applications of the aerospace industry. The aerospace vehicles need to be fabricated from composites characterized by high strength, stiffness, and toughness, enabling them to resist the harsh weathering conditions and impacts from flying objects in their operating environment. Therefore, the research efforts are concentrated on developing new types of epoxy composites that meet the requirements of high strength, elasticity, and impact toughness with minimal environmental impact. In this study, the loading and silylation effects of cellulose on the tensile properties of epoxy composites are investigated using MD simulations. The epoxy thermoset is reinforced with two different loadings of cellulose at 28.1 wt.% and 43.9 wt.%. We use the hydrolyzed APTES as a crosslinker for epoxy and as a silane coupling agent for cellulose. The epoxy matrix partially crosslinked with APTES is reinforced with raw cellulose. The silylated cellulose reinforcements have covalent bonds with epoxy through the silane and amine parts of hydrolyzed APTES molecules. The tensile modulus and shear modulus are determined by the Voigt model based on the elastic constants retrieved from the MD simulation conducted using PCFF/PCFF+. The ultimate tensile strength of epoxy composites is evaluated based on their stress-strain responses under the tensile load, which are obtained from reactive MD simulations. The results of MD simulations show that increasing the content of raw cellulose from 28.1 wt.% to 43.9 wt.% would add further improvements to ultimate strength, tensile modulus, and shear modulus by 16.99%, 26.84%, and 28.93%, respectively. The silylated cellulose at 28.1 wt.% enhances the tensile modulus, shear modulus, and strength of epoxy composite by 14.55%, 15.65%, and 17.11%, respectively, compared to its counterpart reinforced with raw cellulose. The application of silylation treatment on the cellulose at 43.9 wt.% increases the elastic modulus, shear modulus, and tensile strength of epoxy/cellulose composite by 4.23%, 4.64%, and 16.50%, respectively. The silylation treatment can effectively increase the tensile strength of epoxy/cellulose composites with the increasing contents of cellulose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Y.A. and F.B.; methodology, A.Y.A.; software, A.Y.A.; validation, A.Y.A., F.B., and B.M.; formal analysis, A.Y.A.; investigation, A.Y.A. and F.B.; resources, A.Y.A. and B.M.; data curation, A.Y.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Y.A. and F.B; writing—review and editing, A.Y.A. and F.B.; visualization, A.Y.A.; supervision, F.B. and B.M.; project administration, B.M.; funding acquisition, B.M. and F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ren, Z.; Guo, R.; Zhou, X.; Bi, H.; Jia, X.; Xu, M.; Wang, J.; Cai, L.; Huang, Z. Effect of amorphous cellulose on the deformation behavior of cellulose composites: molecular dynamics simulation. Rsc Advances 2021, 11, 19967–19977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakob, M.; Mahendran, A.R.; Gindl-Altmutter, W.; Bliem, P.; Konnerth, J.; Müller, U.; Veigel, S. The strength and stiffness of oriented wood and cellulose-fibre materials: A review. Progress in Materials Science 2022, 125, 100916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirviö, J.A.; Lakovaara, M. A Fast Dissolution Pretreatment to Produce Strong Regenerated Cellulose Nanofibers via Mechanical Disintegration. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 3366–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbotina, E.; Montanari, C.; Olsén, P.; Berglund, L.A. Fully bio-based cellulose nanofiber/epoxy composites with both sustainable production and selective matrix deconstruction towards infinite fiber recycling systems. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2022, 10, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adusumali, R.B.; Reifferscheid, M.; Weber, H.; Roeder, T.; Sixta, H.; Gindl, W. Mechanical Properties of Regenerated Cellulose Fibres for Composites. Macromolecular Symposia 2006, 244, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, I.; McGrath, M.; Lawrence, D.; Schmidt, P.; Lane, J.; Latella, B.; Sim, K. Mechanical and fracture properties of cellulose-fibre-reinforced epoxy laminates. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2007, 38, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, A.; Kondor, A.; Schmid, T.; Einsiedel, R.; Müssig, J. Surface properties and fibre-matrix adhesion of man-made cellulose epoxy composites – Influence on impact properties. Composites Science and Technology 2016, 123, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, N.; Bavishi, J.; Parameswaranpillai, J.; Salim, N.; Joseph, J.; Madras, G.; Fox, B. Thermally flexible epoxy/cellulose blends mediated by an ionic liquid. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 52832–52836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, N.; Mohammad, F.; Pervaiz, M.; Jawaid, M.; Alothman, O.; Sain, M. Mechanical, morphological and structural properties of cellulose nanofibers reinforced epoxy composites. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2017, 97, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, J.; Sapuan, S.; Rashid, U.; Ilyas, R.; Hassan, M. Thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties of oil palm cellulose nanofibril reinforced green epoxy nanocomposites. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 278, 134421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoodi, R.; El-Hajjar, R.; Pillai, K.; Sabo, R. Mechanical characterization of cellulose nanofiber and bio-based epoxy composite. Materials & Design (1980-2015) 2012, 36, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, S.; Kumar, B.; Panicker, P.S.; Pham, D.H.; Kim, J. High-performance green composites made by cellulose long filament-reinforced vanillin epoxy resin. Polymer Testing 2023, 123, 108042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Huang, Y. Dispersion characterizations and adhesion properties of epoxy composites reinforced by carboxymethyl cellulose surface treated carbon nanotubes. Powder Technology 2022, 404, 117505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tüfekci, M. Nonlinear Dynamic Mechanical and Impact Performance Assessment of Epoxy and Microcrystalline Cellulose-Reinforced Epoxy. Polymers 2024, 16, 3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, S.S.; Dartiailh, C.; Levin, D.B.; Yan, N. Highly Toughened and Transparent Biobased Epoxy Composites Reinforced with Cellulose Nanofibrils. Polymers 2019, 11, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.S.; Kuo, P.Y.; Chen, H.; Yan, N. Investigating the effect of lignin on the mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of cellulose nanofibril reinforced epoxy composite. Industrial Crops and Products 2017, 100, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissilä, T.; Hietala, M.; Oksman, K. A method for preparing epoxy-cellulose nanofiber composites with an oriented structure. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2019, 125, 105515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C.; Panicker, P.S.; Kim, D.; Adil, S.; Kim, J. High-strength cellulose nanofiber/graphene oxide hybrid filament made by continuous processing and its humidity monitoring. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 13611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, H.; Low, I. Mechanical properties and water absorption behaviour of recycled cellulose fibre reinforced epoxy composites. Polymer Testing 2012, 31, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voicu, S.I.; Thakur, V.K. Aminopropyltriethoxysilane as a linker for cellulose-based functional materials: New horizons and future challenges. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2021, 30, 100480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjanzadeh, H.; Behrooz, R.; Bahramifar, N.; Gindl-Altmutter, W.; Bacher, M.; Edler, M.; Griesser, T. Surface chemical functionalization of cellulose nanocrystals by 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018, 106, 1288–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, J.; Ren, H.; Jin, J.; He, H.; Jin, P.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, Y. Research progress of nanocellulose-based food packaging. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2024, 143, 104289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, H.; Uno, T.; Tsujisaki, H.; Matsushima, T.; Tajima, K. Nanofibrillated Bacterial Cellulose Modified with (3-Aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane under Aqueous Conditions: Applications to Poly(methyl methacrylate) Fiber-Reinforced Nanocomposites. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 29561–29569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Jiang, M.; Jiang, Z.; Hui, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Z. Effect of surface modification of bamboo cellulose fibers on mechanical properties of cellulose/epoxy composites. Composites Part B: Engineering 2013, 51, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, R.; Rainosalo, E.; Thomas, S.P.; Ramamoorthy, S.K.; Zavašnik, J.; Vuorinen, J.; Skrifvars, M. Modification of epoxy resin by silane-coupling agent to improve tensile properties of viscose fabric composites. Polymer Bulletin 2018, 75, 167–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, R.; Rainosalo, E.; Ramamoorthy, S.K.; Thomas, S.P.; Zavašnik, J.; Vuorinen, J.; Skrifvars, M. Mechanical, thermal, and burning properties of viscose fabric composites: Influence of epoxy resin modification. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2018, 135, 46673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, K.; Zhou, A.; Yu, Z.; Qin, R.; Zou, D. Atomic insight into the functionalization of cellulose nanofiber on durability of epoxy nanocomposites. Nano Research 2023, 16, 3256–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plimpton, S. Fast Parallel Algorithms for Short-Range Molecular Dynamics. Journal of Computational Physics 1995, 117, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Design, M. MedeA, 2023.

- Vashisth, A.; Ashraf, C.; Zhang, W.; Bakis, C.E.; van Duin, A.C.T. Accelerated ReaxFF Simulations for Describing the Reactive Cross-Linking of Polymers. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2018, 122, 6633–6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, D.A.; Sengupta, D.; Foroutan, H.; Russo, M.F.; van Duin, A.C.T. Oxidation of Silicon Carbide by O2 and H2O: A ReaxFF Reactive Molecular Dynamics Study, Part I. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2012, 116, 16111–16121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tschopp, M.A.; Horstemeyer, M.F.; Shi, S.Q.; Cao, J. Mechanical properties of amorphous cellulose using molecular dynamics simulations with a reactive force field. International Journal of Modelling, Identification and Control 2013, 18, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileo, P.G.M.; Krauter, C.M.; Sanders, J.M.; Browning, A.R.; Halls, M.D. Molecular-Scale Exploration of Mechanical Properties and Interactions of Poly(lactic acid) with Cellulose and Chitin. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 42417–42428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppal, N.; Pappu, A.; Gowri, V.K.S.; Thakur, V.K. Cellulosic fibres-based epoxy composites: From bioresources to a circular economy. Industrial Crops and Products 2022, 182, 114895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, O.L. A simplified method for calculating the debye temperature from elastic constants. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 1963, 24, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chang, A.; Wang, Y. Structural, elastic, and electronic properties of cubic perovskite BaHfO3 obtained from first principles. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2009, 404, 2192–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Lickfield, G.C.; Yang, C.Q. Molecular modeling of cellulose in amorphous state. Part I: model building and plastic deformation study. Polymer 2004, 45, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Zhang, L.; He, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, L.; Ao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shang, L. Improving processability and mechanical properties of epoxy resins with biobased flame retardants. Polymer International 2024, 73, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbiebrunken, T.; Fiedler, B.; Hojo, M.; Tanaka, M. Experimental determination of the true epoxy resin strength using micro-scaled specimens. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2007, 38, 814–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Luo, J.; Daniel, I. Mechanical characterization of graphite/epoxy nanocomposites by multi-scale analysis. Composites Science and Technology 2007, 67, 2399–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santmarti, A.; Liu, H.W.; Herrera, N.; Lee, K.Y. Anomalous tensile response of bacterial cellulose nanopaper at intermediate strain rates. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 15260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research, D.E.S. Schrödinger Release 2021-2: Desmond Molecular Dynamics System; www.schrodinger.com: New York, NY, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Watowich, S.J.; Meyer, E.S.; Hagstrom, R.; Josephs, R. A stable, rapidly converging conjugate gradient method for energy minimization. Journal of Computational Chemistry 1988, 9, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Yan, Z.; Fang, W.; Zhang, Y. Molecular Dynamics Simulation on Tensile Behavior of Cellulose at Different Strain Rates. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2023, 2023, 7890912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayadi, S.; Brouillette, F. Silylation of phosphorylated cellulosic fibers with an aminosilane. Carbohydrate Polymers 2024, 343, 122500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, L.; Andrade, R.; Birgin, E.G.; Martínez, J.M. PACKMOL: A package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2009, 30, 2157–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundahl, M.J.; Klar, V.; Wang, L.; Ago, M.; Rojas, O.J. Spinning of Cellulose Nanofibrils into Filaments: A Review. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2017, 56, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.P.; Chen, Z.K.; Yang, G.; Fu, S.Y.; Ye, L. Simultaneous improvements in the cryogenic tensile strength, ductility and impact strength of epoxy resins by a hyperbranched polymer. Polymer 2008, 49, 3168–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; He, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Lin, P.; Yang, S.; Fu, S. High-toughness, environment-friendly solid epoxy resins: Preparation, mechanical performance, curing behavior, and thermal properties. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2020, 137, 48596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, X.; Liang, N.; Xu, H.; Wu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Nie, B.; Zhang, D. Toughness and its mechanisms in epoxy resins. Progress in Materials Science 2022, 130, 100977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, F.; Galland, S.; Johansson, M.; Plummer, C.J.; Berglund, L.A. Cellulose nanofiber network for moisture stable, strong and ductile biocomposites and increased epoxy curing rate. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2014, 63, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaraj, R.; Sathish, S.; Mansadevi, T.L.D.; Supriya, R.; Surakasi, R.; Aravindh, M.; Karthick, A.; Mohanavel, V.; Ravichandran, M.; Muhibbullah, M.; et al. Investigation of Weight Fraction and Alkaline Treatment on Catechu Linnaeus/Hibiscus cannabinus/Sansevieria Ehrenbergii Plant Fibers-Reinforced Epoxy Hybrid Composites. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2022, 2022, 4940531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).