The practical efficacy of the AZTRM-D methodology is demonstrated through a lab-built scenario. This scenario utilizes NVIDIA Orin devices as the core IoT components and a local GitLab server to embody DevSecOps principles within a Zero Trust architecture. The setup is designed to provide the most secure setup for devices while maintaining usability.

7.1. Currently Implemented Setup

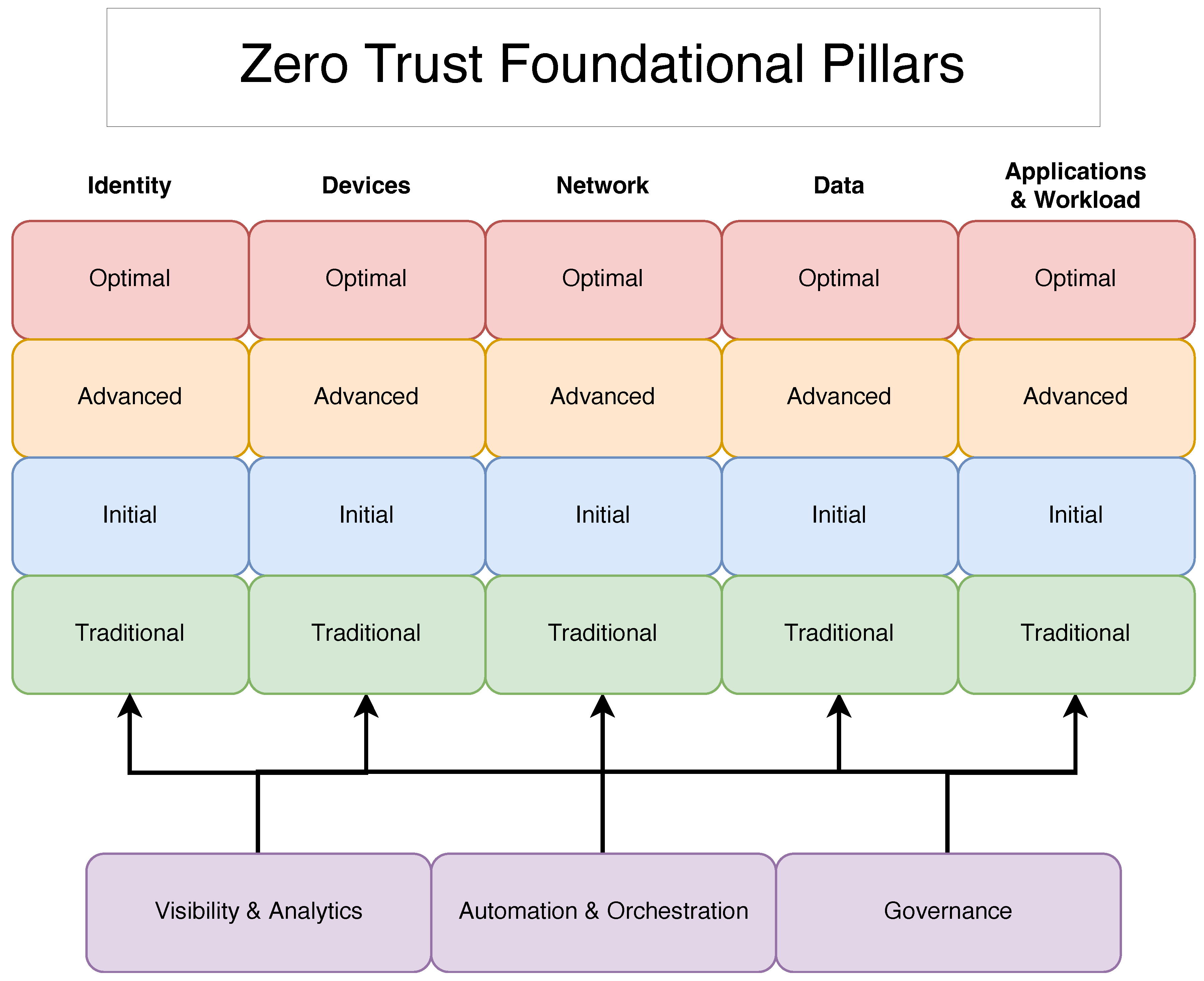

The lab setup meticulously implements Zero Trust principles, leveraging the capabilities of NVIDIA Orin devices and a GitLab-centric workflow. The security controls are mapped to core pillars of Zero Trust, establishing a strong baseline in the current implementation, with future additions planned to further mature this security posture. Through every step of the development cycle for both software and hardware, this device was audited, tested for security and had security as the forethought of every single design and development decision.

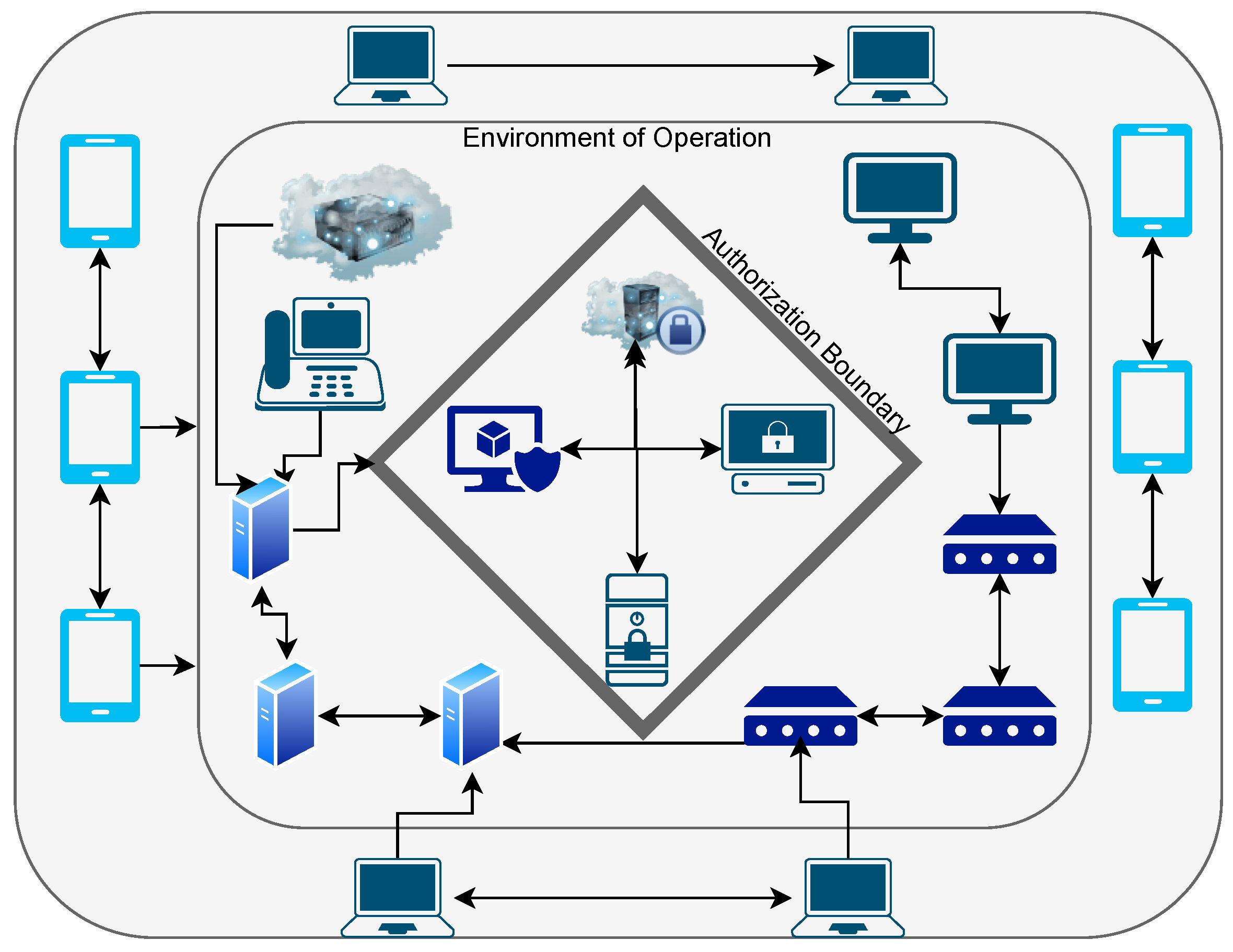

The existing AZTRM-D setup integrates a comprehensive suite of security measures, thoughtfully aligned with core Zero Trust concepts. The security model first addresses the human element, focusing on user identity and ensuring appropriate, least-privilege access. In this setup, stringent identity and user security measures govern all system interactions. Access to GitLab repositories is strictly confined to authorized users, with secure authentication mechanisms mandated for all developers and administrators. A robust SSH key management policy necessitates key changes every seven days. Multi-factor authentication (MFA) is enforced for all user logins to the GitLab server. Account lifecycle management is rigorously enforced through automated workflows; for instance, user accounts are automatically locked after three failed login attempts, and accounts are automatically suspended after 10 days of inactivity and subsequently purged if inactivity persists for an additional 30 days, minimizing risks associated with dormant accounts. Current policy also includes provisions for periodic re-authentication during active sessions to ensure continued authorized access. Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) is rigorously enforced, ensuring users operate with the minimum necessary permissions. Regular audits of user access to the local GitLab server verify these permissions. Addressing user awareness and responsibility, comprehensive security training is provided to all users interacting with the IoT system, alongside strict onboarding and offboarding procedures for personnel.

Following the focus on users, comprehensive measures are in place to secure the devices themselves. To minimize the attack surface on the NVIDIA Orin devices, a foundational hardening process has been completed. This involves disabling or restricting all unnecessary services and curtailing internet access through short-term, scheduled connections, with Bluetooth connectivity entirely disabled. Secure access to the local GitLab server is enforced using SSH keys protected by strong passphrases. Communication from the Orin devices to the GitLab server employs reverse SSH tunnels, preventing the devices from exposing listening ports. Operating systems and applications on the devices are consistently kept updated and hardened; this includes major quarterly updates, minor monthly updates, and as-needed patches, with their distribution managed via automated processes through the local GitLab server. Device integrity is actively maintained through firmware integrity checks designed to prevent tampering. Additionally, the devices undergo periodic scans to catalog installed applications and their versions, facilitating anomaly detection. The continuous monitoring of the health status of each Orin device, which flags errors or operational deviations, leverages automated tools. Devices connecting to the network must also use strong certificate-based authentication. The physical security of these devices is addressed by monitoring systems for changes in temperature, humidity, and power supply, maintaining a detailed physical device inventory, and keeping historic logs that record who accessed specific physical components and when.

The integrity of network communications and the operational environments is maintained through several layers of security. The IoT network segment is isolated to limit its exposure to unauthorized access from other network zones. Microsegmentation is applied to the network hosting the Orin devices, effectively limiting potential lateral movement between nodes should a compromise occur. Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) are currently utilized to provide secure remote access to the local GitLab server. Configured firewalls block all unauthorized outbound traffic originating from the IoT network. Network exposure is further reduced by closing all unused ports and disabling ICMP (ping) functionality to thwart external network reconnaissance.

Protecting the applications and workloads running within this environment involves several key practices. Runtime Application Self-Protection (RASP) capabilities are integrated, enabling applications to actively detect and prevent attacks during execution. All code changes intended for monitored applications undergo mandatory code reviews prior to being merged. The integrity of the software supply chain is reinforced by requiring all commits to the local GitLab server to be cryptographically signed. Software Bills of Materials (SBOMs) are generated and maintained, meticulously tracking all software dependencies. The identification of potential threats within this supply chain is supported by automated dependency scanning, and automated security scanning routines are integrated within the local GitLab environment to further streamline vulnerability identification for applications.

Central to the security strategy is the protection of data. Sensitive data is secured by ensuring it resides within access-controlled repositories on the GitLab server. A data classification scheme is employed, labeling data based on its importance to ensure it receives commensurate protection. Data transfers are encrypted using the SFTP protocol. Mechanisms are also established to detect and prevent unauthorized data transfers from the Orin devices or associated systems.

To ensure ongoing security and detect potential threats, the setup incorporates robust analytics and visibility capabilities. Comprehensive logging and auditing of all GitLab server activities provide crucial oversight. The system actively monitors for unusual login behavior, such as unexpected access times or attempts from unrecognized devices, which can indicate compromised user accounts. Anomaly detection systems are deployed to identify suspicious behaviors originating from the Orin devices, complemented by real-time behavioral analysis, often leveraging AI-driven techniques, for dynamic and proactive threat detection. This extends to monitoring unusual user behavior that might indicate potential insider threats. These analytical systems inherently operate with a high degree of automation in data collection, correlation, and initial alerting, forming a key input for security responses.

Finally, the overarching strategy for efficiency, consistency, and proactive enforcement across all these security domains is significantly enhanced through automation and orchestration. This pillar describes the foundational approach to automating various security processes mentioned earlier, such as user account lifecycle management, device update distributions, health monitoring, and security scanning for applications and dependencies. By automating these diverse mechanisms, the AZTRM-D setup ensures the timely and consistent application of security policies, more reliable enforcement of security controls, and proactive execution of maintenance tasks. This reduces the manual burden on security personnel and minimizes the potential for human error, allowing security operations to scale more effectively and respond with greater agility.

7.1.1. System Technical Overview

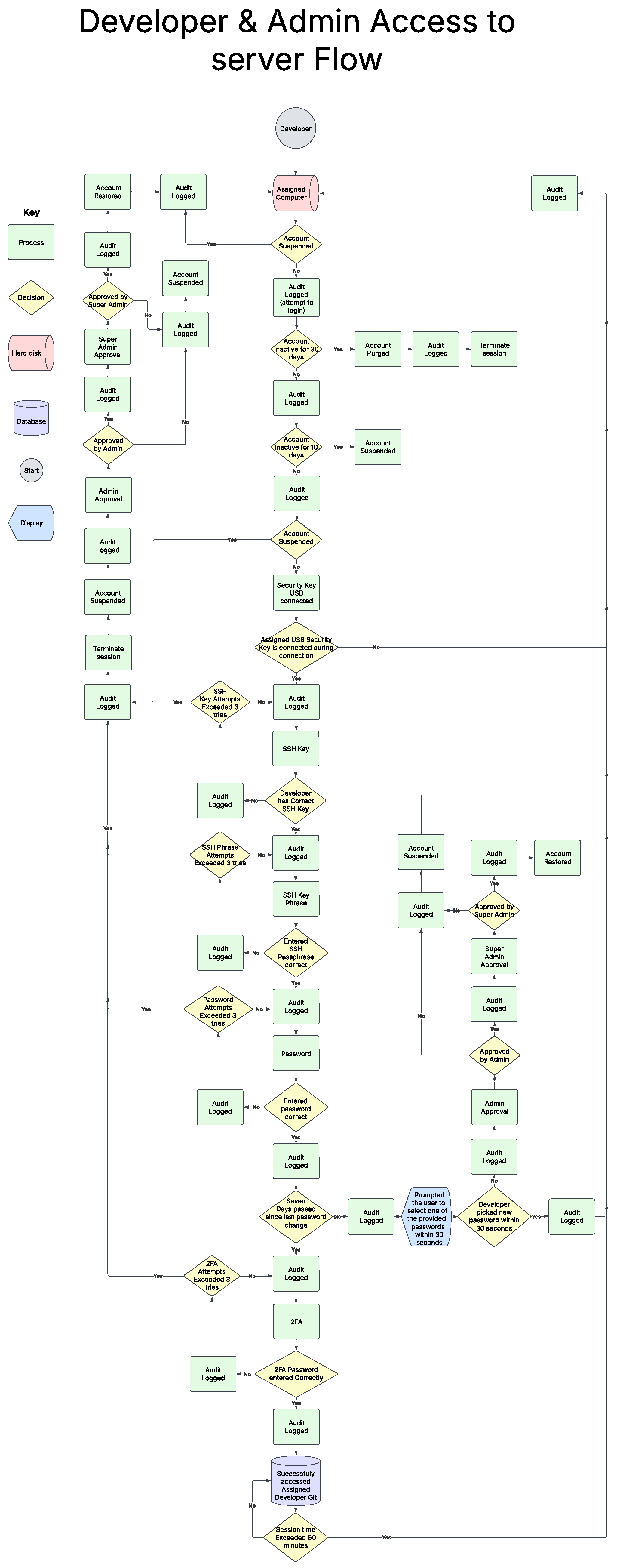

Figure 9, shows the Device Overview Flow. The entire sequence initiates with Bootup. Immediately following this, the device engages in a Secure boot process. This isn’t just a simple boot process but rather it’s a fundamental security step that verifies the integrity of the initial boot software and the operating system. Essentially, it establishes a root of trust, ensuring that the device isn’t launching with compromised or malicious code right from the start. This prevents malware that targets the boot process from taking hold. Once the system is up and running with trusted software, Device health monitoring tools become active. These tools are designed to continuously observe the device’s operational state. They check for signs of malfunction, resource exhaustion (like critically low memory or CPU overload), or unusual system behavior that could indicate a security issue, such as a process consuming excessive resources, or an impending failure. Simultaneously, Environmental monitoring keeps track of physical conditions like temperature and power. Drastic changes here can be significant. For example, overheating might suggest a cooling system failure, physical obstruction, or even physical tampering. Unexpected power fluctuations could point to an unstable supply or an attempt to disrupt the device, potentially leading to data corruption or denial of service. Effective management of the device itself is handled by Device Inventory management. This system is crucial for knowing exactly what hardware components and software versions are deployed. This information helps in tracking necessary updates, managing licenses, ensuring configurations are standardized, and identifying any unauthorized or rogue devices that might appear on the network. Closely linked to this is the regular execution of Firmware integrity checks. Firmware is the low-level software that controls the device’s hardware. These checks, often using cryptographic hashes or digital signatures, confirm that the firmware hasn’t been altered by malware aiming for persistent control at a very fundamental level of the device.

The diagram then points to Security scanning automation in Git server. This step highlights how security is integrated even before updates or new configurations reach the device. It reflects a DevSecOps approach: code and configuration changes managed in a Git version control system (the server) are automatically scanned for vulnerabilities or policy violations. This ensures that new software deployments are vetted for security flaws during the development and integration pipeline, significantly reducing the chances of introducing new risks to the operational device. Protecting the data on the device is paramount, which is where Labeling sensitive data for differentiated protection comes in. This process involves identifying and classifying data based on its sensitivity or criticality. For instance, personal identifiable information (PII) or financial records would be labeled as highly sensitive. Once classified, more stringent security measures—such as stronger encryption, stricter access controls, more intensive logging, or dedicated network segmentation—can be applied to the most critical information. This ensures that protection efforts are focused and proportionate to the data’s value and the risk of its exposure.

To address threats that might originate from within the system or from compromised authenticated accounts, the system employs Behavioral monitoring for insider threat detection. This involves establishing a baseline of normal operational behavior for users and system processes and then looking for deviations. Such deviations might include a user account trying to access unusual files or systems, a process attempting to escalate privileges without authorization, or an account suddenly trying to aggregate or transfer large amounts of data. Complementing this, Unauthorized data transfer detection specifically monitors for and attempts to block attempts to move data off the device or to unapproved external locations. This is a key indicator of data exfiltration, whether malicious or accidental, and can also detect communication with unauthorized command-and-control servers.

As

Figure 9 shows, several ongoing security processes run in parallel, continuously feeding information into the access control decision-making process. Application version scanning for anomaly detection is vital. Outdated software versions often contain known, unpatched vulnerabilities that attackers can exploit. This scanning ensures applications are up-to-date. It also looks for anomalous behavior in current application versions, which might signal a novel attack, a misconfiguration, or unexpected interactions. Runtime Application Self-Protection (RASP) is an advanced security feature embedded within applications. It allows them to detect and block attacks in real-time as they happen. RASP provides a last line of defense at the application layer by identifying and neutralizing malicious inputs, unexpected execution flows, or attempts to exploit known vulnerability patterns from within the running application itself. Many applications rely on external libraries and components, and Automated dependency scanning addresses the risks these introduce. This process automatically checks these third-party software dependencies for known security flaws. By identifying vulnerabilities in these building blocks, the system can ensure they are patched or replaced before they can be exploited.

General Automated anomaly detection and Real-time behavioral analysis serve as broad nets. These systems capture a wide range of unusual activities or patterns at both the system and network levels that might not be caught by more specific checks. This could include unexpected network connections being established, unusual process activity, significant changes in data access patterns, or deviations from established communication protocols.

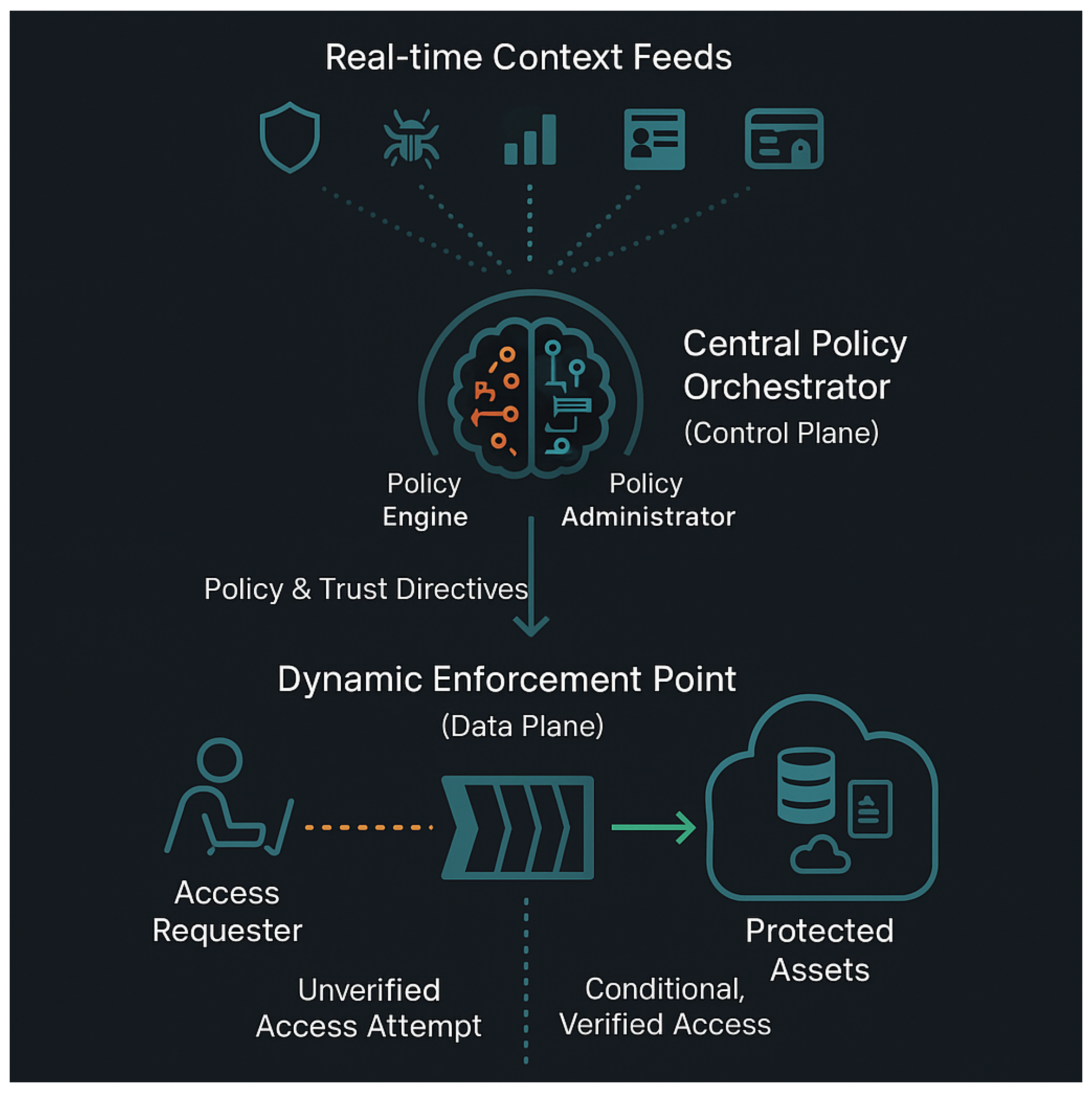

All these streams of security information converge at the Centralized policy engine for access control decisions. This engine acts as the central nervous system for security decisions on the device. It dynamically evaluates the device’s security posture based on the continuous inputs from all the monitoring and detection systems—from device health and firmware integrity to behavioral analytics and detected anomalies. Based on this holistic and real-time assessment, it enforces access policies, determining if a user or process should be granted, denied, or have their access restricted.

Ultimately, this entire orchestrated sequence of boot-time checks, ongoing multifaceted monitoring, and intelligent analysis culminates in how the system manages the User Access flow. The goal is to ensure that any access granted to the device or its data is continuously verified, context-aware (considering factors like user identity, device posture, location, and resource sensitivity), and adheres to the principle of least privilege. This provides a robust and adaptive security posture capable of responding to evolving threats both inside and outside the system.

7.1.2. User Interaction with AZTRM-D Implemented System

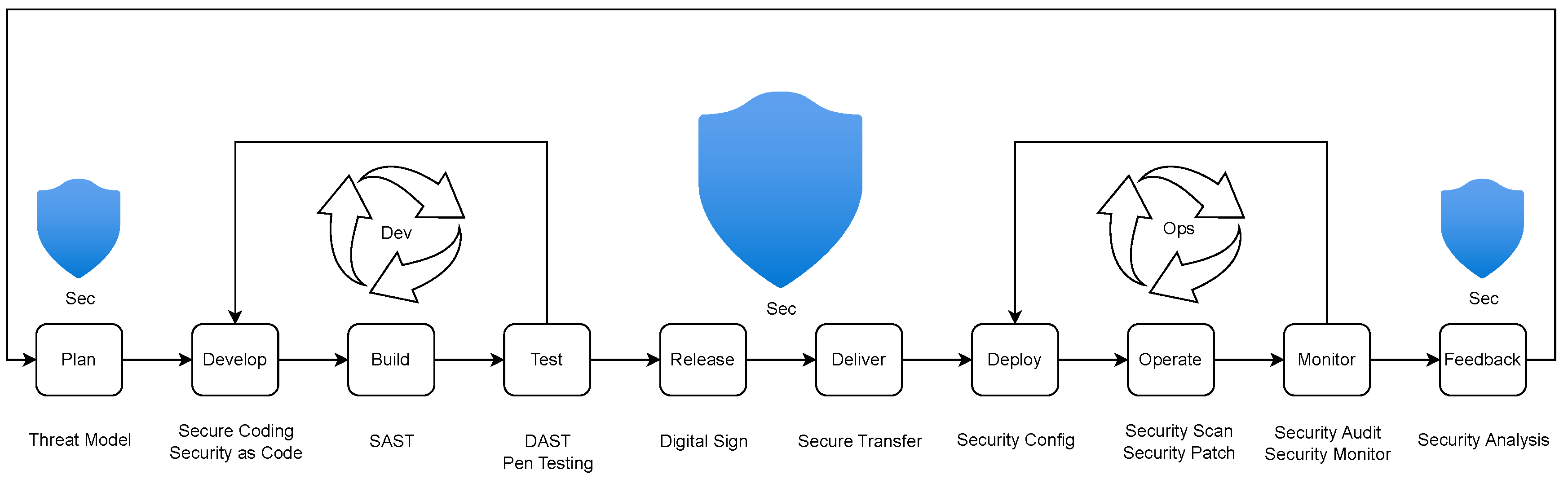

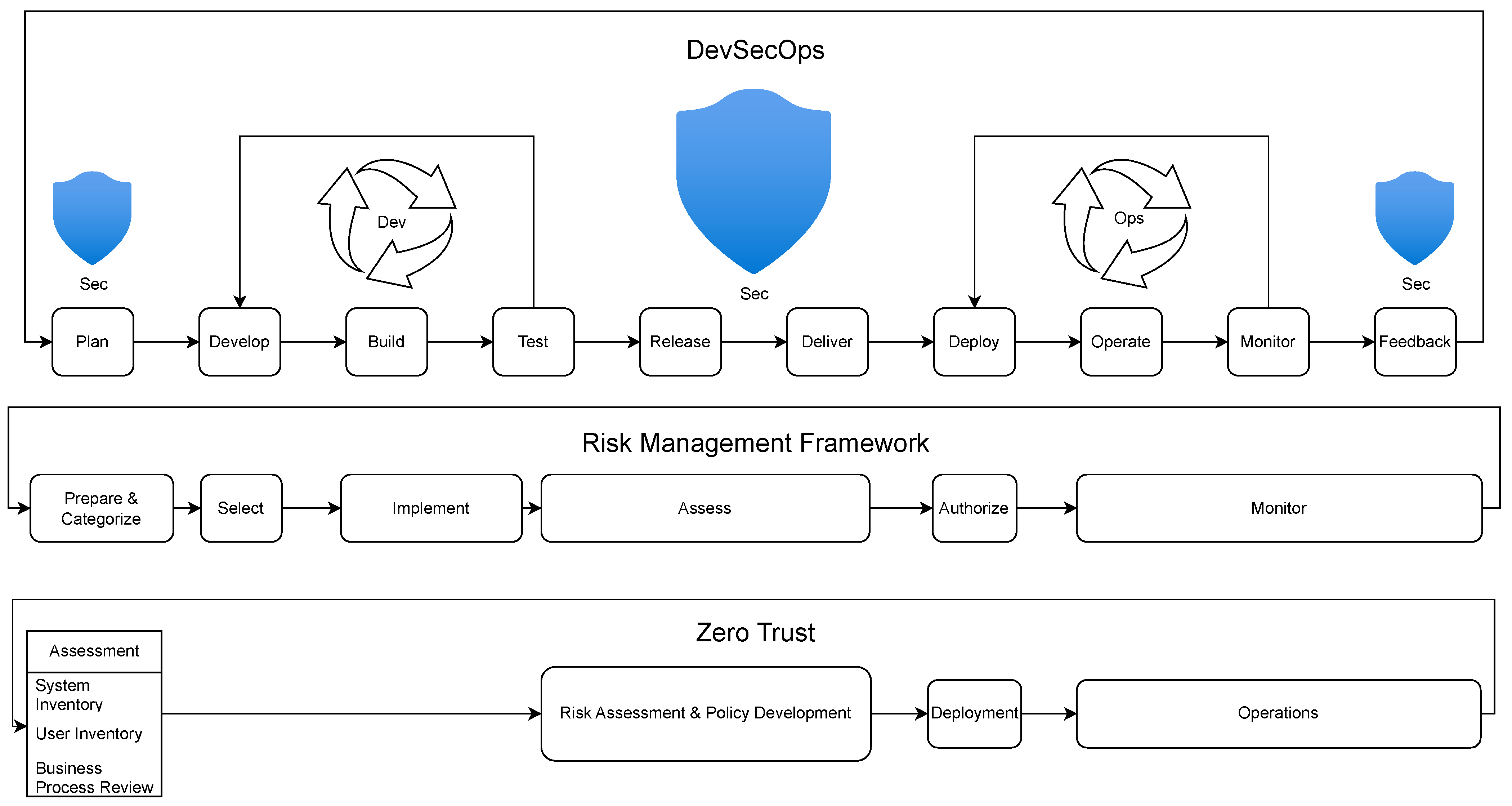

Figure 10 details the user interaction flow with the Git server, illustrating a structured and secure process for software development and deployment. This workflow begins with individual developers and culminates in a production-ready application, emphasizing security checks and approvals at each critical juncture.

The process typically involves multiple developers, such as Developer 1 and Developer 2 shown in the diagram, working in parallel from their respective Developer Repositories. When a developer is ready to integrate their changes, they initiate a Request to Commit to Main Repository. Each significant action, starting with this request, is meticulously recorded, as indicated by the recurring Audit Logged steps.

Before any code is considered for merging, it undergoes a Vulnerability Scan (SAST), which stands for Static Application Security Testing. This scan analyzes the source code for potential security flaws without executing it. If the Vulnerability scan Pass decision is ’No’, the commit is implicitly rejected, requiring the developer to address the identified issues. If it passes, an audit log is made, and the changes then require approval from Admin 1. Should Admin 1 not approve, the process halts for that developer’s changes.

Following Admin 1’s approval, the developer’s code, likely from their DEV Clone of Main Repository (representing their development branch or version), undergoes a Secrets Scan. This scan is crucial for detecting any accidentally embedded credentials, API keys, or other sensitive information within the code. If this Passed Secret Scan results in a ’No’, the changes are again rejected. A successful scan is logged before the developer’s code is ready for the next stage.

Once individual developers have successfully passed these initial checks and approvals, their work is ready for integration. A Merge operation combines the code from Developer 1 and Developer 2 (and potentially others) into a unified QA (Merge of all Dev Repositories) environment. This integrated codebase is logged and then requires approval from Admin 2, who might be a QA lead or a different administrator.

If Admin 2 approves, the integrated code proceeds to a Dependency and SBOM (Software Bill of Materials) Check. This step examines all third-party libraries and components for known vulnerabilities and ensures a complete inventory of software ingredients, which is vital for ongoing security management. A failure here (Passed Dependency and SBOM Check is ’No’) sends the code back for remediation. Success at this stage is logged, and the QA version then undergoes a dynamic Vulnerability Scan (DAST). Unlike SAST, DAST tests the application in its running state to find vulnerabilities that only appear during execution. If the DAST is not passed, the build is rejected.

After successfully passing DAST, the code, now thoroughly vetted at the QA level, is subjected to an Infrastructure as Code Scan. This ensures that any configuration scripts or templates used to deploy the application are also secure and compliant. If this scan is passed, the code moves to the Stage (QA Approved Version Repository), which serves as a pre-production environment. Every successful step continues to be logged.

The final gate before production is the Super Admin Approved decision. Upon receiving this approval, the release artifact is formally signed (Sign Release Artifact), a critical step for ensuring its integrity and authenticity. This signed artifact is then stored in a Secure Rep (repository). From this secure storage, the application is finally deployed to the Prod (Production Repository). Each of these final steps is also carefully logged, maintaining a complete audit trail of the entire lifecycle from development to deployment.

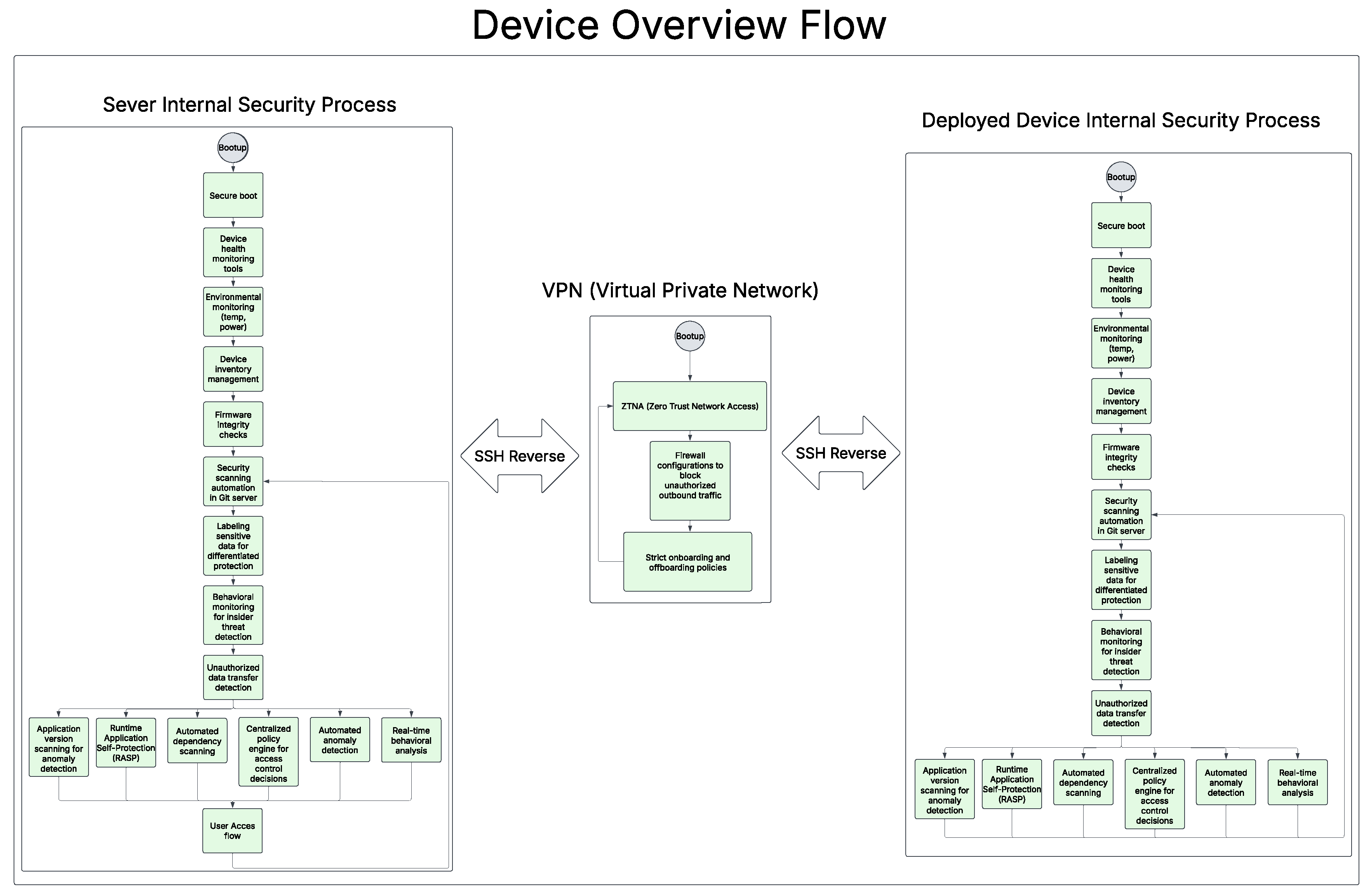

Figure 11 outlines the detailed process governing user access and interaction with a server hosted on one of the devices, emphasizing rigorous security checks and account management protocols. The interaction begins when a User attempts to connect from an Assigned Computer. Immediately, this action is logged for audit purposes, a practice repeated throughout the entire flow.

Before proceeding with authentication, the system checks the account’s status. If an Account is Inactive for 10 days, it is automatically Suspended, and this event is logged. If this inactivity extends to 30 days, the Account is Purged entirely, with a corresponding audit log. An account that is Suspended, either due to inactivity or other reasons encountered later in the flow, requires intervention to be restored. This typically involves an Admin Approval or, in some cases, a Super Admin Approval. If approval from an admin is granted ("Approved by Admin"), the Account is Restored, and these actions are logged. Similarly, if super admin approval is granted ("Approved by Super Admin"), the account is restored and logged. Without approval, the account remains suspended. It is important to note that the terms ’admin’, and ’super admin’ symbolize an admin that is higher the current users level. So, if the user is already an admin, they would need approval from the next level admin above them.

Assuming the account is active and not suspended, the login sequence commences with a check to ensure the Assigned USB Security Key is connected during connection. If the Security Key USB is not connected, the login attempt is logged ("Audit Logged (attempt to login)") and the Account is Suspended. If the key is present, this is logged, and the process moves to SSH key validation.

The system then verifies the SSH Key. If SSH Key Attempts have Exceeded 3 tries, the account is suspended and logged. Otherwise, it checks if the Developer has the Correct SSH Key. An incorrect key is logged, and this implicitly counts towards the attempt limit. A correct SSH key allows the process to continue after logging. A similar procedure applies to the SSH key’s passphrase: if SSH Phrase Attempts Exceeded 3 tries, the account is suspended. An incorrect Entered SSH Passphrase is logged and counts towards this limit, while a correct one, after logging, permits further progress.

Next, password authentication is performed. Exceeding 3 Password Attempts results in account suspension. An incorrect password entry is logged. If the Entered password is correct, it’s logged, and the system then checks for password freshness. If Seven Days have passed since last password change, this is logged, and the user is Prompted to select one of the provided new passwords within 30 seconds. Failure by the Developer to pick new password within 30 seconds leads to account suspension. Successfully changing the password is logged. If seven days have not passed, this check is bypassed after logging, and the flow advances to Two-Factor Authentication (2FA). For 2FA, if 2FA Attempts have Exceeded 3 tries, the account is suspended. An incorrect 2FA Password entry is logged. If the 2FA Password entered is Correctly verified, this successful step is logged.

Upon successful completion of all these authentication stages, the user has Successfully accessed Assigned Developer Git, and this access is logged. The session is then monitored; if the Session time Exceeded 60 minutes, the session is automatically Terminated, with all relevant actions logged. This comprehensive flow ensures that access is multi-layered, strictly controlled, and thoroughly audited from initiation to termination.

7.1.3. Future Setup Additions

To further enhance the AZTRM-D implementation and mature the Zero Trust architecture for the NVIDIA Orin-based IoT environment, several key improvements are planned. The network and environmental security architecture is set to evolve. The existing VPN infrastructure will be either replaced or complemented by a comprehensive Zero Trust Network Access (ZTNA) solution. This advancement will enforce identity- and context-aware access to internal services, such as the local GitLab server, moving away from perimeter-based trust.

Improvements in automation and orchestration will focus on responsiveness and refined policy enforcement. The system’s ability to react to threats will be improved by establishing automatic incident response triggers. These pre-defined triggers will enable automated actions, such as isolating a compromised Orin device from the network or locking a suspicious user account, significantly reducing the mean time to respond. A more dynamic and granular access control model, which will impact user access and overall governance, will be achieved through the implementation of a centralized policy engine. This engine, orchestrated with automation, will facilitate real-time, context-aware access control decisions based on a richer set of inputs, including device posture, user behavior, and environmental factors.

7.2. Security Testing Journey Through the AZTMR-D Model

This section details the methodical approach taken to assess the security posture of the Jetson Nano Developer Kit at various stages of its hardening journey, guided by the principles of the AZMTR-D model. Each testing scenario is presented from both an external attacker’s viewpoint and an insider’s perspective. From the outsider’s perspective, we employed a standard penetration testing methodology, encompassing reconnaissance, scanning, gaining access, maintaining access, and clearing tracks. For the insider’s perspective, our methodology centered on evaluating the system’s adherence to Zero Trust principles, scrutinizing authentication, access controls, and the integrity of internal processes. This dual-faceted approach allowed for a comprehensive understanding of the evolving effectiveness of the implemented security measures.

7.2.1. Security Testing Scenario - Factory Default Configuration and Setup

This initial scenario describes the security assessment of the Jetson Nano in its unconfigured, out-of-the-box state, mirroring the conditions an attacker would encounter a newly deployed, unhardened device.

Our initial steps involved reconnaissance, where our primary goal was to gather intelligence about the untouched device without overtly alerting it. We started by observing network traffic to identify the Jetson Nano’s presence; merely seeing its MAC address and assigned IP on our lab network confirmed its existence. A simple ping sweep then established that the device was active, a fundamental piece of information. The importance here was simply establishing that the device was online and reachable. We also conducted Google dorking, a technique involving specialized search queries, to uncover any publicly available information about default Jetson Nano configurations, common network setups, or developer discussions that might detail initial setup procedures or known default credentials. This was vital because it often led us to crucial information like the common nvidia:nvidia default login, which directly informed our password guessing efforts later. At this stage, we weren’t expecting to find specific developer code or applications, but rather system-level default behaviors.

Next, in the scanning phase, we moved to actively probe the device for specific vulnerabilities present in its untouched state. We used Nmap, a powerful network scanning tool, to perform a comprehensive port scan (nmap -sV -p- <Jetson_Nano_IP>). This was critically important because it allowed us to see all open ports on the Jetson Nano as it ships from the factory, revealing its inherent attack surface. The most crucial discovery was Port 22 for SSH, which is a standard remote access service and consistently found open by default in all out-of-the-box JetPack configurations. We frequently found Port 5900 for VNC as well, indicating a graphical remote access service that could be targeted. In some cases, we even observed web services on Port 80 or Port 443; while these might not serve complex developer applications yet, they often hosted default pages or basic system management interfaces (like a simple web server for an initial setup guide). The -sV (service version detection) switch in Nmap was invaluable because it performed "banner grabbing," telling us the exact software versions running on these open ports. For example, knowing it was "OpenSSH 8.2p1 Ubuntu" immediately narrowed down our search for known vulnerabilities (CVEs) specific to that version. This version information was then fed into automated vulnerability scanners like Nessus and OpenVAS. These tools are immensely important as they automatically cross-reference the identified software versions against vast databases of known security flaws. The results consistently highlighted numerous unpatched CVEs within the Linux kernel, NVIDIA’s proprietary drivers (NvGPU, bootloader components, Trusty TEE), and various third-party libraries. These weren’t just theoretical weaknesses; they represented concrete pathways for privilege escalation (gaining higher access), denial of service (making the device unusable), or even remote code execution (running our own code on the device) directly on the default system components. The network mapping aspect also revealed that the default firewall settings were extremely permissive, essentially exposing all active services to the entire network without any strong filtering. This lack of a robust perimeter defense meant that once a service was found, it was directly accessible for exploitation.

With a clear understanding of open services and identified vulnerabilities on the default setup, we moved into the pivotal gaining access phase. The most straightforward and consistently successful method for initial entry was brute-forcing the SSH service. The existence of the default nvidia user account, almost always paired with a weak or default password like nvidia:nvidia on a fresh install, was a critical finding. We employed Hydra, a powerful password cracking tool, using a targeted dictionary of common default passwords and a brute-force approach. The significance of this lies in the fact that the default SSH daemon lacked any robust account lockout mechanisms; this allowed us to try thousands of password combinations without triggering alerts or temporary blocks, making eventual success highly probable. This process frequently resulted in successful SSH login, granting us a direct command-line shell as the nvidia user. If VNC was also exposed, Hydra could be adapted for VNC password cracking, potentially providing graphical access. Beyond brute-force, if our Nessus scans had identified a particularly severe and easily exploitable CVE—for instance, a remote code execution vulnerability in a specific kernel module or a default web service—we would have leveraged matching modules within the Metasploit Framework. Metasploit is crucial because it automates the complex process of exploiting known vulnerabilities, often providing a direct shell, sometimes even as root, bypassing the need for password cracking entirely. Even when our initial access was as the unprivileged nvidia user (e.g., through a weak password), the default sudo privileges commonly granted to this user were a major win. This allowed for immediate privilege escalation to root simply by executing sudo su - or sudo bash. This means that even a simple default login vulnerability directly grants us full control over the out-of-the-box system. If sudo wasn’t configured this way, we’d then actively look for local privilege escalation vulnerabilities, often by using tools like LinPEAS or manually searching for outdated binaries with SUID bits set that could be abused to gain root. The ability to escalate privileges is paramount as it grants full control over the compromised system, regardless of what applications are installed.

Once we had secured a shell, ideally with root privileges, the next critical objective was maintaining access to ensure our continued presence on the compromised system. This phase is important because it ensures that even if the Jetson Nano is rebooted or basic security patches are applied, we retain control. Our primary method involved establishing persistent reverse shells. We would typically modify system initialization files like ~/.bashrc (for user-specific persistence) or /etc/rc.local (for system-wide persistence, if present and executable) to automatically launch a simple Netcat reverse shell or a more sophisticated Python or Bash script that would connect back to our attacker-controlled listener. This ensures that upon every system startup, a backdoor connection is re-established. For a more robust and covert backdoor, we could compile a static binary backdoor and place it in a common system path (e.g., /usr/local/bin/), or more aggressively, replace a legitimate system binary like sshd with our own altered version. As a root user, we could also create hidden user accounts with administrative privileges. These accounts are significant because they are specifically designed to be difficult for system administrators to discover during routine checks, providing a stealthy persistent foothold on the otherwise default system. To secure our command and control communications, we employed tunneling techniques, specifically SSH tunneling. This was crucial because it allowed us to route our traffic over an encrypted SSH connection, masking our activities and making it harder for network defenders to detect our malicious traffic. Keystroke logging mechanisms were also deployed, aiming to capture user entries. While an out-of-the-box system might not have sensitive user data immediately, this capability is important for any future activity on the device, including any sensitive data or commands typed by the user as they begin to set it up. Furthermore, we integrated applications that appeared legitimate but permitted unauthorized entry, commonly known as Trojan horses. These are vital for blending into the system’s normal operations and ensuring covert, long-term access.

The culmination of our external attack revolved around clearing tracks, a critical phase ensuring the attacker remained undetected. This step is crucial for avoiding detection and hindering any subsequent forensic investigation. It involved the systematic wiping of logs, concealment of malicious files, and manipulation of timestamps to eradicate any evidence or proof of our activities. Our initial step involved targeted log tampering; we diligently deleted or modified relevant logs within /var/log/, specifically focusing on /var/log/auth.log for authentication attempts and /var/log/syslog for general system activities, to remove any trace of our intrusion. Concurrently, we cleared or altered shell command histories, such as ~/.bash_history, so that no one could easily see what commands we had executed during our initial compromise and persistence setup. For more sophisticated concealment, steganography was a viable option; this involved embedding malicious files or data within legitimate, innocuous system files, thereby evading detection by rudimentary file integrity checks. File timestamp alteration, using tools like Timestomp, was important because it allowed us to meticulously change the access, modification, and creation timestamps of any system files we touched. This effectively misled forensic investigators by making it appear as though no recent changes had occurred, blending our activities with legitimate system operations. Finally, encrypting any remaining hidden files or our command and control communications served to obscure our activities and significantly complicate forensic analysis, making it far more challenging for anyone to trace our steps or understand the full scope of the compromise on the default system.

When we approached the Jetson Nano as a normal user, specifically logging in with the default nvidia account, the Zero Trust model would immediately flag several critical security failures. First, the very existence of a hardcoded, default username and a common, weak password (like nvidia:nvidia) meant that the first "trust" decision—authentication—was already profoundly compromised. A true Zero Trust system would mandate strong, unique, and multi-factor authenticated credentials from the absolute outset, never relying on defaults. Once logged in, even without any user-created developer code, the user had unfettered access to their home directory, /home/nvidia/. Within this directory, the presence of ~/.bash_history (the shell’s command history file) was a significant Zero Trust concern. In a robust Zero Trust environment, command execution logs should be immutable, centralized, actively monitored, and streamed off-device, not just a local file readable (and thus modifiable) by the user who executed them. Our ability to simply read this history file locally, without an external audit stream, represented a gap in accountability. Furthermore, we could easily read many critical system configuration files located in /etc/. This is a direct Zero Trust violation because it means basic system information (e.g., network settings, service configurations) is freely available to any authenticated user, regardless of their specific role or explicit need-to-know. A Zero Trust approach would apply granular access controls, limiting read access to even configuration files based on the specific role and current context of the user, ensuring that unauthorized information disclosure is prevented. Most critically, the default nvidia user had unconstrained sudo privileges. This is a catastrophic failure from a Zero Trust perspective. Zero Trust fundamentally operates on the principle of least privilege, meaning users (and processes) are granted only the absolute minimum access required for their current, authenticated task, and this access is continuously re-evaluated. Granting sudo without specific, granular policy enforcement (e.g., requiring re-authentication for each sudo command, limiting which commands can be run, or enforcing time-bound access) means that an initial, weak authentication immediately granted full administrative control. This single default configuration completely bypassed the "never trust, always verify" ethos, as one initial, easily compromised verification led to total system control without further checks. Additionally, the log files in /var/log/ were broadly accessible to the nvidia user. While logs are essential for auditing, a Zero Trust approach would ensure these logs are instantly forwarded to a secure, immutable, and external logging system where they cannot be tampered with or deleted by the user (or process) who generated them. Our ability to simply read these logs locally, combined with the later ability to clear them (as root), represented a severe gap in the auditable chain of trust.

The situation worsened dramatically when we considered the implications of root user access, which, as previously detailed, was trivially achieved from the default nvidia user via sudo. From a Zero Trust perspective, this is the ultimate failure of security. Zero Trust aims to prevent even a compromised internal entity from having unchecked access to sensitive resources. With root, we had complete, unconstrained control over the entire file system. This means we could read and copy any data on the device, including NVIDIA’s core JetPack software, system libraries, and the underlying structure of any pre-installed Docker containers or web server content, even if their data directories were initially empty. While there was no user-created code yet, the ability to exfiltrate the base operating system image itself, or to gain deep, unauthorized insights into NVIDIA’s proprietary components, represented a significant security breach under Zero Trust. Every access request, even for fundamental system files, should be explicitly authorized and logged, and with root, all authorizations were essentially "granted by default." More alarmingly, root access allowed us to bypass all access control mechanisms to modify any system configuration file. This directly violates Zero Trust principles of continuous validation, policy enforcement, and immutable configuration. We could create new hidden user accounts (completely bypassing identity management and authentication policies), modify system network settings (circumventing network segmentation and network access policies), or alter SSH configurations to establish persistent backdoors (undermining authorization, monitoring, and patch management). The ability to install rootkits or other malware anywhere on the system meant we could inject untrusted, malicious code directly into the trusted computing base, a direct affront to Zero Trust’s emphasis on continuous device posture assessment and integrity verification. Furthermore, root access provided the capability to clear tracks by deleting or modifying logs. This is a critical Zero Trust failure. If logs can be altered or erased by the entity generating them or by a compromised entity, there is no way to independently verify behavior, detect compromise, or reconstruct an incident. A Zero Trust architecture would absolutely rely on immutable, centralized logging to maintain an undeniable audit trail, making it impossible for even a root user on the device to hide their actions. In essence, the default Jetson Nano setup, by its very nature of weak default credentials and immediate, unconstrained sudo privileges, effectively created a single, catastrophic point of failure. Once this single point was breached, it completely dismantled any implicit Zero Trust principles that should have been in place. The initial, easily compromised trust granted to the nvidia user immediately expanded to encompass full, unmonitored, and unverified control over the entire system, making it an open book to an insider.

From an outsider perspective, the Jetson Nano is remarkably exposed. Simple reconnaissance quickly identifies the device on the network. Our scans revealed multiple open service ports, notably SSH (Port 22) and often VNC (Port 5900), all running with outdated software versions that have known vulnerabilities. Crucially, the default firewall rules were virtually nonexistent, offering no protection against incoming connections. The most significant vulnerability for external access was the widespread use of default, easily guessable credentials for the nvidia user (e.g., nvidia:nvidia). The SSH service also lacked basic brute-force protection, allowing unlimited password attempts. Once initial access was gained with these weak defaults, the attacker could immediately escalate to root privileges due to the default sudo configuration. This full control allowed for installing persistent backdoors, establishing hidden communication channels, capturing any future user input, and completely wiping all forensic evidence, ensuring the compromise was both deep and stealthy.

From an insider perspective, even as a regular, non-root user, the default configuration offered little resistance to information gathering and privilege escalation. The nvidia user, right out of the box, had immediate and unrestricted sudo access. This is a severe security flaw, as any compromise of this single default user account instantly grants complete administrative control over the entire system. We could read critical system configuration files (/etc/) and system logs (/var/log/), gaining significant intelligence about the device’s operation. More importantly, with root access, we could manipulate any system file, install malicious software permanently, create hidden user accounts, alter network configurations, and destroy all traces of our activity. This lack of proper user separation and excessive default privileges for a standard user directly undermines principles of least privilege and strong access control.

7.2.2. Security Testing Scenario - After Initial Security Hardening Using AZTMR-D Model

This scenario outlines the security testing conducted after the Jetson Nano underwent its initial phases of hardening with the AZMTR-D model, focusing on addressing network-based vulnerabilities while identifying residual physical attack surface.

Our reconnaissance phase began with passive observation of network traffic within our lab environment. We identified the Jetson Nano’s MAC address and assigned IP address, confirming its presence. A subsequent, non-intrusive ping sweep verified that the device was active and responding. We continued with Google dorking, crafting specialized search queries to uncover any publicly available information related to the Jetson Nano with AZMTR-D hardening. Our goal was to find any inadvertently exposed details, misconfigurations, or known bypasses for the implemented security model. However, unlike previous tests on the default configuration, these efforts yielded no significant leads regarding default credentials, open services, or common deployment patterns that could be exploited. The initial hardening measures appeared to have successfully obscured typical reconnaissance footholds.

Moving into the scanning phase, we employed Nmap, a powerful network scanning tool, to perform a comprehensive port scan across the Jetson Nano’s IP address. In stark contrast to previous assessments on the out-of-the-box system, this hardened configuration revealed no open network ports accessible from the outside. No SSH, no VNC, no web services (HTTP/HTTPS), nor any other application-level ports were found listening or responding. This indicated that the network-based attack surface had been effectively eliminated by the hardening efforts. Automated vulnerability scanners like Nessus and OpenVAS, typically used to identify unpatched CVEs on open services, subsequently returned no actionable findings, as there were no network services to probe. This confirmed the effectiveness of the network-level segmentation and firewall rules implemented during the hardening process.

With no network-accessible services, our efforts in the gaining access phase were redirected to physical attack vectors, as remote access was completely blocked. The only remaining external interfaces identified as potential points of compromise were the General Purpose Input/Output (GPIO) pins and the unencrypted SD card. Our primary focus shifted to the physical manipulation of the SD card. The fact that the SD card was unencrypted represented a critical bypass of remote security measures, transforming a logical attack surface into a physical vulnerability.

Once the SD card was physically removed from the target device, we mounted it on a separate Linux virtual machine. This allowed us to gain full access to the root filesystem , including critical files such as /etc/shadow, which contains hashed user passwords. This immediate access to the entire file system demonstrated that the lack of full-disk encryption on the SD card was the remaining, severe vulnerability. We could perform direct filesystem manipulation, including creating new directories like /mnt/sd, mounting the SD card’s root partition to it (sudo mount /dev/sda1 /mnt/sd) , and then listing its contents.

With full access to the filesystem, we moved to an offline password reset for a local user. We used the chroot utility to emulate the target environment directly from our host system. This involved binding critical system directories like /dev, /proc, and /sys from the host to the mounted SD card’s filesystem within the chroot environment (e.g., sudo mount –bind /dev /mnt/sd/dev). Once inside the chrooted environment (sudo chroot /mnt/sd /bin/bash) , we gained a root shell within the device’s own operating system. From this root shell, we leveraged the passwd utility to set a new password for an existing local user (e.g., koda01). A sync command was executed immediately afterward to ensure these changes were permanently written to the disk. This process effectively bypassed any configured authentication mechanisms as it was performed offline, directly on the filesystem.

After the password reset, we proceeded with remounting and safe ejection. All virtual filesystems mounted for the chroot environment (/dev, /proc, /sys) were properly unmounted , followed by the unmounting of the main SD card partition. The SD card was then safely ejected and returned to the target Jetson Nano device.

The final step in our external attack was the successful login. With the SD card back in the Jetson Nano, we connected via a UART serial console (ttyTHS1) to the device. This physical console access is typically used for debugging and initial setup, and unlike network ports, it remained open. We were able to boot the device and, when prompted, successfully authenticated using the newly set password for the koda01 account. This granted us a standard user shell under the koda01 account. Crucially, once authenticated as koda01, we could immediately escalate privileges to root using sudo su - , as the koda01 user was already a member of the sudo group and possessed full administrative rights. This demonstrated that while network access was blocked, the combination of unencrypted storage and the default sudo configuration for local users allowed for a complete system compromise via physical access.

When we approached the Jetson Nano as a developer or administrator, interacting with the system hardened by the AZMTR-D model, our experience began with a highly structured and restrictive environment designed to enforce strict security policies at every interaction point. Our initial attempt to connect from an assigned computer was immediately Audit Logged, establishing a continuous and fundamental audit trail. Before proceeding with authentication, the system rigorously checked our account’s status. We observed that accounts inactive for 10 days were automatically Suspended and logged, and if this inactivity extended to 30 days, the account was Purged entirely, with a corresponding audit log. Account restoration, if suspended, required explicit Admin Approval or Super Admin Approval, ensuring that such actions were verified and not unilateral. Assuming our account was active and not suspended, the login sequence mandated that our Assigned USB Security Key be connected. Failure to connect the Security Key USB resulted in the login attempt being logged as "Audit Logged (attempt to login)" and the account being Suspended. With the key present and logged, the process moved to SSH key validation. The system verified our SSH Key, suspending the account and logging the event if SSH Key Attempts Exceeded 3 tries. An incorrect SSH Key was logged and counted towards this limit, while a correct one allowed progress after logging. A similar procedure applied to the SSH key’s passphrase: exceeding 3 SSH Phrase Attempts resulted in account suspension, an incorrect Entered SSH Passphrase was logged, and a correct one, after logging, permitted further progress. Following this, password authentication was performed. Exceeding 3 Password Attempts led to account suspension, with incorrect entries logged. If the Entered password was correct and logged, the system then checked for password freshness. If Seven Days had passed since the last password change, this was logged, and we were Prompted to select one of the provided new passwords within 30 seconds. Failure to pick a new password within 30 seconds led to account suspension, while successful changes were logged. If seven days had not passed, this check was bypassed after logging, and the flow advanced to Two-Factor Authentication (2FA). For 2FA, exceeding 3 Attempts resulted in account suspension, and an incorrect 2FA Password entry was logged. Only if the 2FA Password entered was Correctly verified, was this successful step logged. Upon successful completion of all these stringent authentication stages, we were granted access to the Assigned Developer Git, with this access immediately logged. Our session was then continuously monitored; if the Session time Exceeded 60 minutes, the session was automatically Terminated, with all relevant actions logged.

Beyond initial access, our interaction as developers with the Git server followed a meticulously structured and secure process, significantly different from an unhardened environment. We worked from our respective Developer Repositories. When ready to integrate changes, we initiated a Request to Commit to Main Repository, with each action meticulously Audit Logged. Before any code was considered for merging, it underwent a Vulnerability Scan (SAST). If this scan failed, the commit was implicitly rejected, requiring us to address the identified issues. If it passed, an audit log was made, and the changes then required approval from Admin 1. Without Admin 1’s approval, our changes would not proceed. Following Admin 1’s approval, our code, from our DEV Clone of Main Repository, underwent a Secrets Scan, crucial for detecting embedded credentials or sensitive information. A failed Secrets Scan would result in rejection. A successful scan was logged before readiness for the next stage. Once individual developers’ work passed these checks, a Merge operation combined our code into a unified QA (Merge of all Dev Repositories) environment. This integrated codebase was logged and required approval from Admin 2. Upon Admin 2’s approval, the integrated code proceeded to a Dependency and SBOM (Software Bill of Materials) Check, examining third-party components for vulnerabilities and ensuring inventory. A failure here would send the code back for remediation. Success was logged, and the QA version then underwent a dynamic Vulnerability Scan (DAST). If DAST was not passed, the build was rejected. After successfully passing DAST, the code was subjected to an Infrastructure as Code Scan, ensuring configuration scripts were secure. If this scan passed, the code moved to the Stage (QA Approved Version Repository), serving as a pre-production environment. All successful steps continued to be logged. The final gate before production was the Super Admin Approved decision. Upon this approval, the release artifact was formally signed (Sign Release Artifact) for integrity and authenticity. This signed artifact was then stored in a Secure Rep (repository). From this secure storage, the application was finally deployed to the Prod (Production Repository). Each of these final steps was also carefully logged, maintaining a complete audit trail of the entire lifecycle from development to deployment.

Despite these comprehensive controls, the core limitation identified from an insider perspective was the system’s assumption that all access would strictly follow these defined workflows. The AZMTR-D model, as implemented, did not explicitly account for what would happen if a user, particularly one with an administrator role, somehow gained root access to the underlying operating system of the Jetson Nano outside of these defined application and authentication layers. This means that if a physical vulnerability (like the unencrypted SD card discussed in the outsider perspective) were exploited, or if an obscure kernel exploit allowed root access, the granular controls and audit logs of the Git server and user access flows would likely be bypassed or rendered irrelevant at the OS level. The strict lateral movement restrictions, which normally prevent an admin from easily elevating privileges or accessing other systems without explicit approval, would be circumvented by an underlying root compromise. This represents a significant gap where the "never trust, always verify" principle of Zero Trust could be fundamentally undermined at the lowest system layers.

From an outsider perspective, the Jetson Nano, after being hardened with the AZMTR-D model, demonstrated exceptional resilience against network-based attacks. Our reconnaissance yielded no exploitable leads, and comprehensive port scanning confirmed that no network services (SSH, VNC, web servers, etc.) were open or responsive, effectively eliminating the remote network attack surface. Automated vulnerability assessments found no actionable network-level vulnerabilities. However, this robust network defense did not extend to physical security. The system’s critical vulnerabilities shifted entirely to physical access points: specifically, the General Purpose Input/Output (GPIO) pins and, most critically, the unencrypted SD card. With physical access to the SD card, we were able to mount the device’s root filesystem on an external machine, gaining full access to sensitive files like /etc/shadow. This permitted an offline password reset for a local user (e.g., koda01) via a chroot environment, completely bypassing all authentication mechanisms. Upon physically reinserting the SD card and connecting via a UART serial console (ttyTHS1), we successfully logged in with the new credentials. Crucially, this user possessed default sudo privileges, allowing immediate and trivial root escalation. This demonstrated that while network access was blocked, the combination of unencrypted storage and the default sudo configuration for local users allowed for a complete system compromise via physical access.

From an insider perspective, when we approached the Jetson Nano as a developer or administrator interacting with the system hardened by the AZMTR-D model, we encountered a highly structured and restrictive environment enforcing strict security policies. Access controls were comprehensive, including multi-factor authentication, robust audit logging, and strict session management. The development and deployment pipeline was meticulously secure, integrating continuous security checks (SAST, Secrets Scan, Dependency/SBOM, DAST, IaC Scan) and mandatory multi-admin approvals. Despite these strong controls, a core limitation emerged: the AZMTR-D model, as initially implemented, did not explicitly account for a user gaining root access to the underlying operating system outside of these defined application and authentication layers. This meant a physical vulnerability, such as the unencrypted SD card, or an obscure kernel exploit, could lead to a fundamental bypass of the granular controls and audit logs at the OS level, effectively circumventing lateral movement restrictions and undermining the Zero Trust principle at its foundation.

7.2.3. Security Testing Scenario - After Final Security Hardening Using AZTMR-D Model

This section details the security testing scenario conducted after implementing the final security hardening measures on the Jetson Nano Developer Kit, guided by the AZMTR-D model. This comprehensive round of hardening specifically addressed the critical vulnerabilities identified in previous assessments, focusing on physical attack vectors and root access controls. Our objective was to validate the complete elimination of viable compromise paths from both external and internal perspectives.

Our re-assessment from an outsider perspective on the Jetson Nano, following the final security hardening using the AZMTR-D model, involved reiterating our previous test phases. During reconnaissance, passive network observation and Google dorking again yielded no significant leads. The device remained inconspicuous on the network, with no inadvertently exposed configurations or public bypasses for the implemented security measures, indicating that the initial hardening efforts to obscure typical reconnaissance footholds remained effective. Moving into the scanning phase, comprehensive port scans with Nmap confirmed, once more, that there were absolutely no open network ports accessible from the outside. SSH, VNC, web services, and all other application-level ports were closed and unresponsive. Automated vulnerability scanners like Nessus and OpenVAS continued to return no actionable findings, reaffirming that the network-based attack surface had been completely eliminated.

With network access definitively blocked, our efforts in the gaining access phase again shifted to physical attack vectors. However, the critical vulnerabilities identified in the previous assessment had been addressed. The most significant change was the encryption of the SD card. When we physically removed the SD card and attempted to mount it on a separate Linux virtual machine, it presented as an encrypted volume. All attempts to access its contents or perform an offline password reset were met with failure, as the encryption successfully protected the root filesystem. This rendered the previous method of direct filesystem manipulation and offline credential bypass entirely ineffective. Furthermore, the GPIO pins, previously identified as an open interface, were now closed or disabled, eliminating this alternative physical attack vector. While the UART serial console (ttyTHS1) remained physically accessible for debugging, its utility for an attacker was severely limited. Without the ability to tamper with the SD card or exploit easily accessible root escalation paths, the console simply presented a login prompt for which we had no credentials, and attempts to brute-force or bypass authentication through it were unsuccessful due to the new root access controls and policies. Consequently, we were unable to gain initial access to the system via any physical means, signifying that the previous "maintaining access" and "clearing tracks" phases were rendered impossible for an outsider.

From an insider perspective, interacting with the Jetson Nano after the final AZMTR-D hardening, the robust access controls and development workflows remained consistently applied, successfully preventing lateral movement within our defined roles as developers and administrators. Our stringent authentication process, involving Audit Logging, account status checks (inactivity suspension/purging with multi-tiered admin approvals), mandatory Assigned USB Security Key, rigorous SSH key/passphrase validation with strict attempt limits, multi-stage password authentication including freshness checks, and mandatory Two-Factor Authentication (2FA), continued to ensure highly controlled and audited access. Session monitoring with automatic termination after 60 minutes also remained in force. The development and deployment pipeline continued to enforce security from code commit to production deployment, with compulsory SAST, Secrets Scans, Dependency and SBOM checks, DAST, Infrastructure as Code Scans, multi-admin approvals, and signed release artifacts. These layered controls consistently ensured that all our actions within the application and Git server environment were strictly governed, verified, and logged.

Crucially, the major limitation identified in the previous assessment—the critical blind spot concerning out-of-band root access—had been effectively addressed. With the implementation of access controls and policies for Root users, and the increased difficulty in obtaining and validating root privileges, the system no longer presented a trivial path to full compromise even if an attacker were to bypass physical security measures like SD card encryption. Our tests confirmed that attempts to gain root access, even from an authenticated administrative account (e.g., koda01), were now significantly more challenging and required explicit validation that was not easily circumvented. The system’s response to such attempts indicated granular controls were active, preventing the automatic and unconstrained privilege escalation previously observed. This means that even if a future physical vulnerability were discovered, or an obscure kernel exploit was attempted, the hardened root access mechanisms would prevent a complete system takeover that bypasses all the carefully implemented AZMTR-D controls and audit trails. The "never trust, always verify" principle now extended to the deepest system layers, significantly mitigating the risk of an insider gaining unauthorized root privileges or circumventing the established security architecture.

This was our final round of testing on the Jetson Nano, conducted after implementing the comprehensive security hardening measures derived from the AZMTR-D model, including SD card encryption, closed GPIO pins, and robust root access controls. From an outsider perspective, the device demonstrated exceptional resilience. Our reconnaissance efforts yielded no exploitable network leads, and comprehensive port scanning confirmed that the entire network attack surface had been eliminated; no open network ports were detected, rendering remote exploitation impossible. Furthermore, the critical physical vulnerabilities identified in previous assessments were successfully addressed. The SD card was encrypted, preventing offline filesystem manipulation and credential bypasses, and the GPIO pins were closed, eliminating them as an attack vector. While the UART serial console (ttyTHS1) remained physically accessible, its utility to an external attacker was neutralized by the new root access controls, making it impossible to gain a foothold or escalate privileges. Consequently, we were unable to gain any access to the system via external or physical means, confirming a robust external security posture.

From an insider perspective, the AZMTR-D model enforced a highly structured and restrictive environment that effectively prevented lateral movement within the defined roles of developers and administrators. The system’s multi-layered authentication processes, including mandatory USB security keys, rigorous SSH key and passphrase validation, stringent password policies, and two-factor authentication, coupled with meticulous audit logging and strict session management, ensured all access was meticulously controlled and verified. The development and deployment pipeline remained exceptionally fortified, with automated security checks (SAST, Secrets Scans, Dependency and SBOM, DAST, Infrastructure as Code Scans), multi-admin approvals, and signed release artifacts safeguarding the integrity of the software supply chain. Crucially, the significant blind spot regarding trivial root access, identified in prior testing rounds, was comprehensively addressed. The newly implemented access controls and policies for root users, combined with the increased difficulty in obtaining and validating root privileges, meant that even if an authenticated administrative account were compromised, or an obscure kernel exploit attempted, it would no longer grant unconstrained system control. This final hardening round successfully extended the "never trust, always verify" principle to the deepest system layers, significantly mitigating the risk of an insider gaining unauthorized root privileges or circumventing the established security architecture.