1. Introduction

Wood is a biological material, which has been widely used in the fields of decoration, architecture, and furniture because of its renewable, environmental, and abundant resources [

1,

2]. However, wood is highly inflammable [

3], and its extensive use in daily life inevitably holds fire risk. The most direct and effective method to mitigate this risk is brushing flame-retardant coatings on its surface [

4], which minimizes the fire risk of flammable materials, benefit personnel evacuation and rescue, and reduce fire losses. Meanwhile, the building coatings with environmental protection, ecology, low toxicity, and efficient fire resistance have become an important direction for research and development of flame retardant coatings.

In recent years, inorganic geopolymer have emerged as promising candidates for flame retardant coatings due to their durability, halogen-free, environmentally friendly, and low cost advantage [

5,

6]. Silica fume is a metallurgical by-product [

7] with high emissions but low utilization efficiency, which has been proven to be used as flame-retardant coatings. Shahidi [

8] et al. investigated the flame retardancy of an intumescent flame retardant enhanced by silica fume and graphene oxide/talc. The result indicated that contains 10 wt.% silica fume and 1 wt.% MLGO/talc powder has the highest fire resistance. However, silica fume-based geopolymer coatings exhibit certain limitations in practical applications, such as insufficient flame retardancy [

9] and low residual structural strength [

10], failing to protect plywood effectively. Therefore, it is necessary to optimize its flame retardancy through synergistic flame-retardant mechanism.

Currently, one of the most commonly used flame retardants is melamine (MEL), due to their lower cost and non-toxicity during combustion, without secondary pollution [

11]. During combustion, the MEL takes away heat and releases N

2, NH

3, and other non-flammable gases, diluting the concentration of O

2 and toxic gas [

12]. However, the flame retardancy of composite coating is not effectively increased by the inclusion of MEL alone. In recent years, numerous flame-retardant systems that exhibit synergistic effects have been developed for a variety of materials. For instance, combinations such as phosphorus/boron [

13] and phosphorus/boron/nitrogen [

14] have been demonstrated to achieve synergistic flame retardancy. Zhang et al. [

15] improved the thermal stability and flame retardancy of furfurylated wood by introducing a multifunctional catalyst system comprising BA and ammonium dihydrogen phosphate (ADP). Huo et al. [

16] incorporated hyperbranched oligomers containing phosphorus/nitrogen/boron (BDHDP) in epoxy resin (EP), achieving a UL-94 V-0 with 1.5 wt.% of BDHDP. Consequently, it is a good strategy to use multi-element synergistic effects to improve the flame retardancy of geopolymer coatings.

Zinc phytate (ZnPA) is a compound formed by chelating phytic acid and zinc ions and serves as an eco-friendly and efficient flame retardant due to its high phosphorus content [

17]. Phosphorus-containing flame retardants facilitate catalytic charring and combustion prevention, and generate phosphorus radicals capable of capturing active radicals, thereby quenching the combustion chain reaction [

18]. Zhang et al. [

19] used Zn

2+ ions in ZnPA to chelate with components such as dopamine, DOPO, and fly ash, creating a flame retardant organic-inorganic hybrid coating. In this sense, ZnPA could form a zinc ion chelate cross-linked structure with the silica fume-based geopolymer to enhance the stability and continuity of the residues.

Additively, boric acid (BA) is another flame retardant widespread used across various industries [

20], acting as an effective flame-retardant additive by forming a protective B

2O

3 glassy layer during combustion, which shields the material from oxygen and heat [

21]. Savas et al. [

22] investigated the impact of zinc borate (ZnB) on the thermal and flame retardancy of polyamide 6 (PA6) composites containing aluminum hypophosphite (AlHP), where the interactions between AlHP and ZnB resulted in the formation of BPO

4, enhancing the flame retardancy. Therefore, the synergistic effect between BA and ZnPA could further form a zinc-chelated silicon phosphorus boron composite structure within the silica fume-based geopolymers during combustion in theory, thereby enhancing the flame retardancy.

Consequently, this research designs a flame-retardant coating integrating silica fume-based geopolymer with ZnPA/BA/MEL, characterized by x-ray diffraction (XRD), cone calorimeter (CC), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), respectively. It demonstrates that in-situ formed BPO4 significantly enhances the residue strength and improves the flame retardancy of condensed phase. Generally, this thesis creatively proposes a recycling strategy for high value-added utilization of silica fume, exploring the synergistic flame-retardant mechanism of ZnPA/BA/MEL-containing silica fume-based geopolymer coatings.

2. Experiment and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

Silica fume is a gray powder with a SiO2 content > 86 wt.% (mass percentage concentration), a density of 1.62 g/cm3, and a Blaine-specific surface area of 25 m2/g, purchased from Xi’an LinYuan Co., Ltd. ZnPA is procured from Guangzhou Jiale Chemical Co., Ltd. Melamine (MEL) is obtained from Wuxi Yatai United Chemical Co., Ltd. BA is supplied by Zhengzhou Del Boron Chemical Co., Ltd. Analytically pure Polyacrylamide (PAM) is purchased from Tianjin Fuchen Chemical Reagent Factory. Analytical pure Sodium Silicate (Na2SiO3⋅9H2O) is purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) is purchased from Hongyan Chemical Reagent Company. The silane coupling agent (KH-550, CAS No: 919-30-2) is provided by Shandong Yousuo Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) is purchased from Dongguan Tianyu Chemical Co., Ltd. in China. The plywood is supplied by the timber processing plant of Xi’an in China with secondary flame retardancy.

2.2. Preparation of Geopolymer Composite Coating

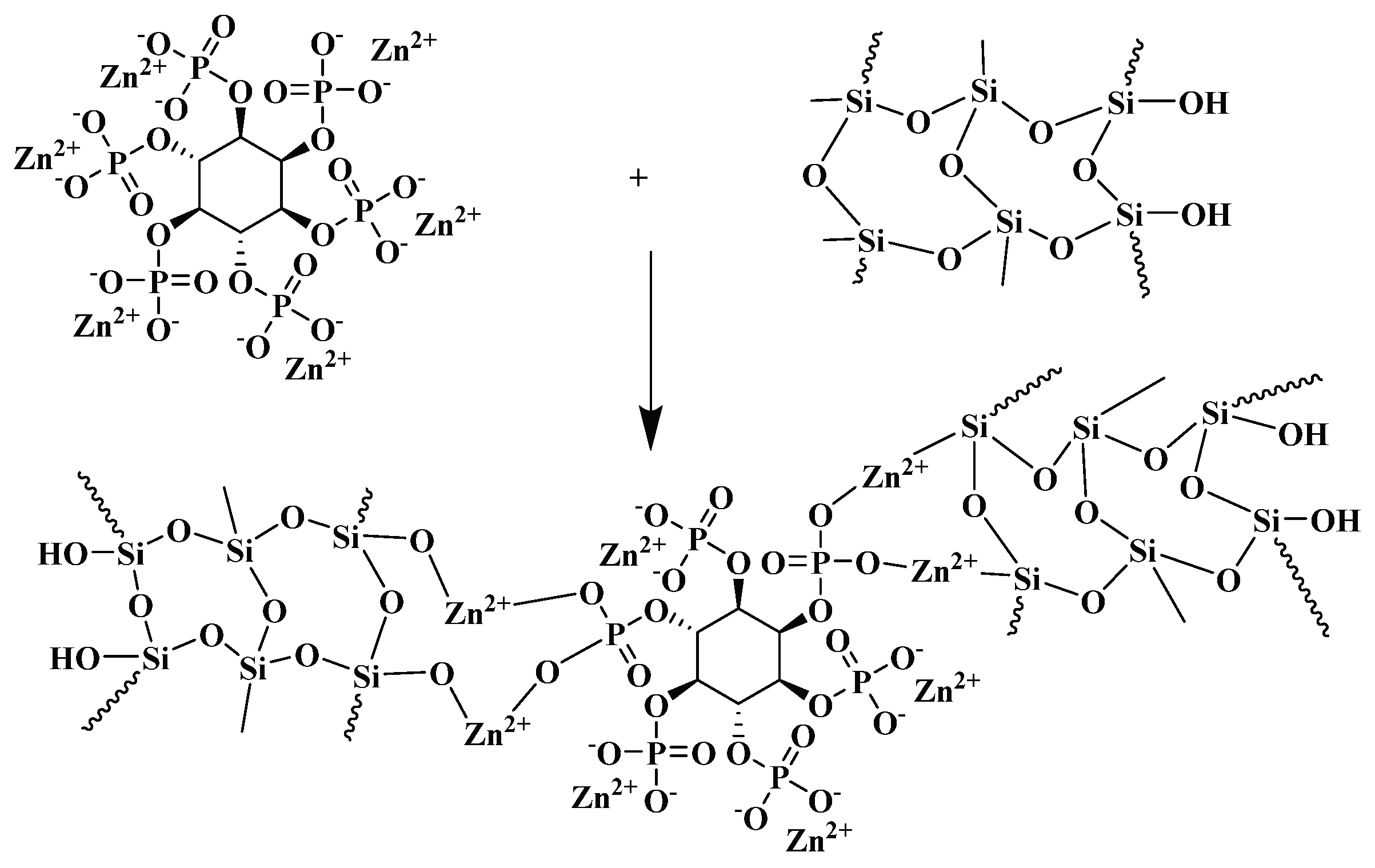

Figure 1 illustrates the preparation steps of silica fume-based geopolymer composite coatings via the multi-step sol-gel method. Firstly, 0.5 g KH-550, 1 g MEL, and varying dosages of ZnPA are weighed according to the

Table 1. They are then added to 15 g water. Magnetic stirring at 700 r·min

-1 at 60°C is applied for approximately 30 min to ensure thorough mixing. The ZnPA solution pretreated by KH550 and MEL is obtained.

Secondly, 14.21g Na2SiO3·9H2O, 5.61g KOH, 30g silica fume, and 30g water are poured into another glass beaker. Then, the mixture is stirred for 10 minutes at 70°C; the speed of the mechanical stirrer is 750 r·min-1, and silica sol is obtained. Then, ZnPA solution is injected into the silica sol and continues mixing for 20 minutes subsequently, the speed is increased to 1000 r·min-1.

Finally, PAM as a thickener and PDMS as an antifoaming agent are added to achieve ZnPA/MEL-doped silica fume-based geopolymer coatings by stirring for 5 minutes. The dosage of ZnPA is 0 g (0.0 wt.%), 0.48 g (0.5 wt.%), 0.95 g (1.0 wt.%), 1.43 g (1.5 wt.%), 1.9 g (2.0 wt.%), 2.38 g (2.5 wt.%), 2.85 g (3.0 wt.%), respectively. Then, the resulting composite coating is covered evenly on the surface of plywood (100×100×5 mm3) for 3 times with the interval about 20 minutes.

Based on the test results of ZnPA-containing geopolymer coatings, further addition of BA is carried out to prepare BA/ZnPA/MEL-containing silica fume-based geopolymer composite coatings. The preparation process is identical to that of the ZnPA-containing coating, as shown in

Figure 1B. The dosage of BA is 0.5 g (0.5 wt.%), 1.0 g (1.0 wt.%), 1.5 g (1.50 wt.%), 2 g (2.0 wt.%), 2.5 g (2.5 wt.%), and 3.0 g (3.00wt.%), respectively. The samples with ZnPA dosage of 0.5 wt.%-3 wt.% numbers as P1-P6. BA dosage of 0.5 wt.%-3 wt.% refers to B1-B6 respectively, and the coating without ZnPA and BA denotes as the control P0.

2.3. Characterizations

2.3.1. Flame Retardancy Testing

The combustion performance of the sample is assessed by a cone calorimeter (CC, ZY6243, Zhongnuo Instruments Co., Ltd., China) according to ISO 5660-1:2015. The tin foil is used to wrap the sample. The irradiative heat flux of CC is 50 kW·m

-2 (approximately 715℃) with the distance between the coating and the ignition needle of 25 mm. The following parameters are real-time recorded by CC, such as time to ignite (TTI, s), heat release rate (HRR, kW·m

-2), peak heat release rate (p-HRR, kW·m

-2), time to p-HRR (T

P, s), total heat release (THR, M·J

-2) and weight loss (WL, g). Meanwhile, the following four parameters are used to assess the flame retardancy of the sample. The fire growth index (FGI) reflects the potential growth and intensity of a fire, which is calculated by the formula (1). The fire performance index (FPI) evaluates the fire performance of materials, which is calculated by the formula (2). The average effective heat of combustion (AEHC) refers to the ratio of THR to WL. The flame retardancy index (FRI) is used to quantify the flame resistance of materials, which is calculated by the formula (3). It is divided into three grades: “FRI < 1”; “1 < FRI < 10”; “10 < FRI < 100”, which represents “poor”, “good”, and “excellent”, respectively.

The sample’s water contact angle (WCA) is tested by the contact angle goniometer (JCY-3, Shanghai Farui instrument in China), which reflects the hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity of the composite coatings. Based on the tangent algorithm, the contact angle is captured and estimated based on a high-resolution camera and software. The experiment is performed five times at different positions of the coating, and then the average value of the water contact angle is taken for the result.

2.3.2. Microstructure Testing

The infrared spectra of the samples before combustion are carried out in the spectral range of 4000-500 cm-1 by an infrared spectrometer Nicolet iS50 (Thermo, Singapore). The composition of the residual layer is analyzed by an X-ray diffractometer (D/MAX-2400) with Cu Kα (λ=1.54056Å) radiation at 40 kV and 40 mA within the range of 2θ=10~50° with the scanning step of 2°, which is preferentially ground into powders. The morphological structures of the barrier layer are observed using a scanning electron microscope (Gemini 500). Each sample needs to be sprayed with gold before scanning electron microscopy to improve the conductivity of the sample. The pyrolysis process of the materials is analyzed by a Mettler analyzer (Germany) at a heating rate of 20℃/min under an N2 flow with the temperature range from 30°C to 1000°C.

3. Results

3.1. Flame Retardancy of Samples

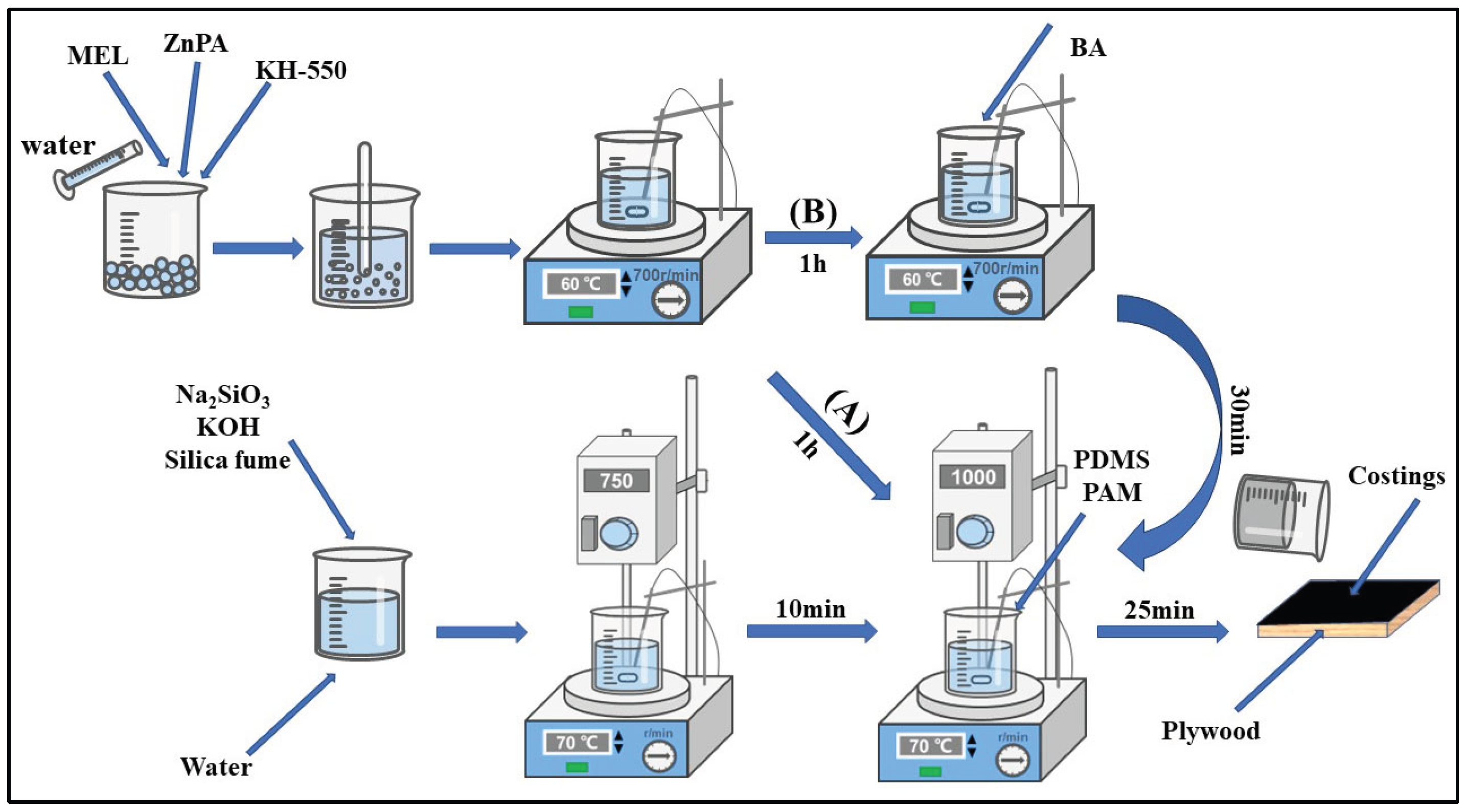

Figure 2a shows the HRR curve for the samples containing ZnPA, which gradually shifts to the right with the increasing content of ZnPA. When the ZnPA dosage is 2.48 g, p-HRR is the lowest, decreasing from 268.78 (P0) to 156.35 kW⋅m

-2 (P5), and T

P delays to 404 s. This indicates that ZnPA enhances the flame retardancy of the composite coating. However, 2.85 g ZnPA leads to a rise in p-HRR and emerges the first peak at 144 s, because the excess ZnPA accelerates the coating catalytic decomposition during combustion.

Figure 2a’ displays the HRR curve for the samples containing BA. The HRR curve decreases at first and then increases. Compared with P5, B3 exhibits a lower p-HRR value of 118.73 kW·m

-2, and T

P is delayed from 404 s to 440 s. When the BA content exceeds 1.50 wt.%, p-HRR gradually rises, indicating that the excess BA leads to a decrease in the flame retardancy of the coating.

Figure 2b and

Figure 2b’ show the smoke temperature of samples, which gradually decreases with the increasing ZnPA content, as shown in

Figure 2b. Among these, P5 presents the lowest smoke temperature, reaching a peak value of 88.66°C at 438 s. It indicates that the doped ZnPA imparts enhanced flame retardancy to the composite coating. When containing 3.00 wt.% ZnPA, the smoke temperature rises to 92.39°C, corresponding to poor flame retardancy. In

Figure 2b’, B3 displays the lowest smoke temperature at 494 s, decreasing from 88.66 (P5) to 84.68°C. This is attributed to BA dehydrating during combustion, which has an endothermic and cooling effect. However, samples with BA content exceeding 1.50 wt.% exhibit a higher smoke temperature in comparison to that of B3. The smoke temperature increases with the increasing BA content, which is completely consistent with the results of HRR.

Figure 2c and

Figure 2c’ present the residual weight value of the samples under an externally constant heat flux of 50 kW⋅m

-2. The lowest final residual weight is observed for P0 (35.29%). As the content of ZnPA increases, the residual weight also increases. P5 displays the maximum final residual weight of 46.09% at 600 s, indicating the incorporated ZnPA imparts a reduced weight loss rate to composite coating. In

Figure 2d’, the residual weight increases firstly and then drops with the increasing BA dosage. Compared to P5, B3 exhibits a lower weight loss of 50.97% at 650 s. The residual weight decreases sequentially of B4, B5, and B6 after combustion. This indicates that higher BA content is detrimental to the flame retardancy of the composite coating.

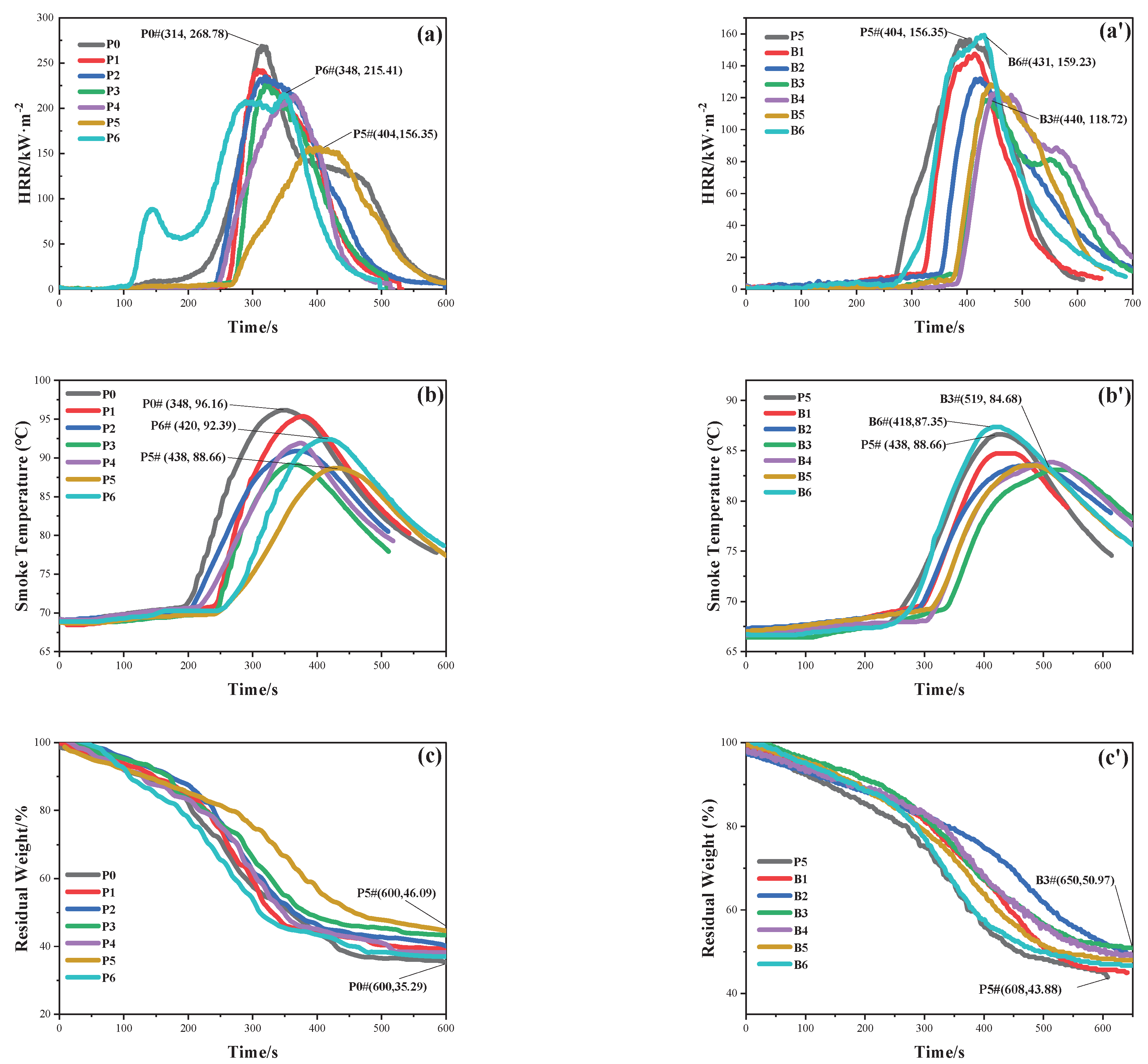

Table 2 presents the combustion parameters of the samples. According to the fire resistance index, the addition of ZnPA and BA extends the TTI of the composite coating. The longest TTI for B3 is 336 s. Among all samples, B3 also exhibits the highest flame retardancy, evidenced by the highest FPI of 2.83 s·m

2·kW

-1 and the lowest FGI of 0.27 kW·m

2·s

-1. A low FGI could slow down flame propagation, FRI is 8.48 indicating a ‘good’ flame retardant grade compared to P0. Conversely, when the content of BA exceeds 1.50 wt.%, these parameters exhibit a contrary trend. For instance, compared to B3, the TTI of B5 shrinks to 318 s, the FPI also declines to 2.48 s·m

2·kW

-1, FGI climbs to 0.29 kW·m

-2·s

-1 with the lower FRI of 7.48, corresponding to the diminished flame retardancy. Therefore, the doped appropriate ZnPA and BA have a synergistic effect, leading to the formation of dense and resilient siliceous layer, corresponding to the enhanced flame retardancy.

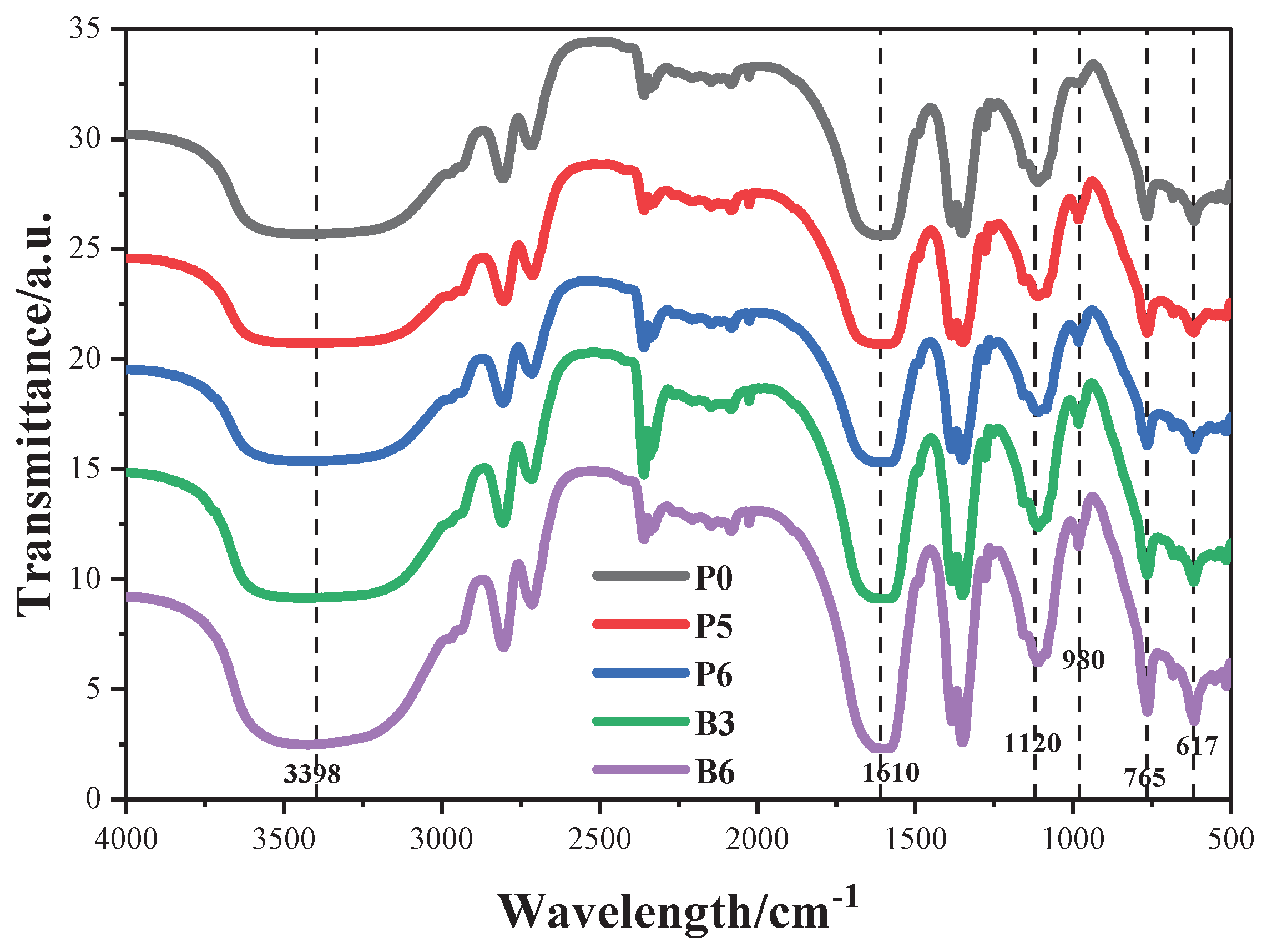

3.2. FTIR Spectra of Samples

Figure 3 presents the obtained FTIR spectra of the composite coatings before burning. The wide peak at 3398 cm

-1 is assigned to stretching vibrations of -OH and N-H [

23]. Among them, -OH is mainly derived from geopolymer and BA, and N-H is mainly derived from MEL. The broad peak at 1600 cm

-1 is assigned the C=N absorption peak of the triazine ring [

24]. The asymmetric vibrations of the Si-O-Si bond are detected at 1120 cm

-1, whereas the symmetric vibrations locates at 765 cm

-1 [

25], attributed to the hydrolysis of silane coupling agents and alkali-activated geopolymer. P-O-C symmetric vibrations occur at 980 cm

-1 [

26]. After the addition of BA, the absorption peaks of B3 and B6 samples at 617 cm

-1 show a strengthening, attributed to the deformation vibration of the atoms in the B-O bond in BA [

27,

28]. Notably, there are no significant differences among the FTIR curves of the samples, indicates that ZnPA and BA have no striking effect on chemical bonds, presenting good compatibility and stability.

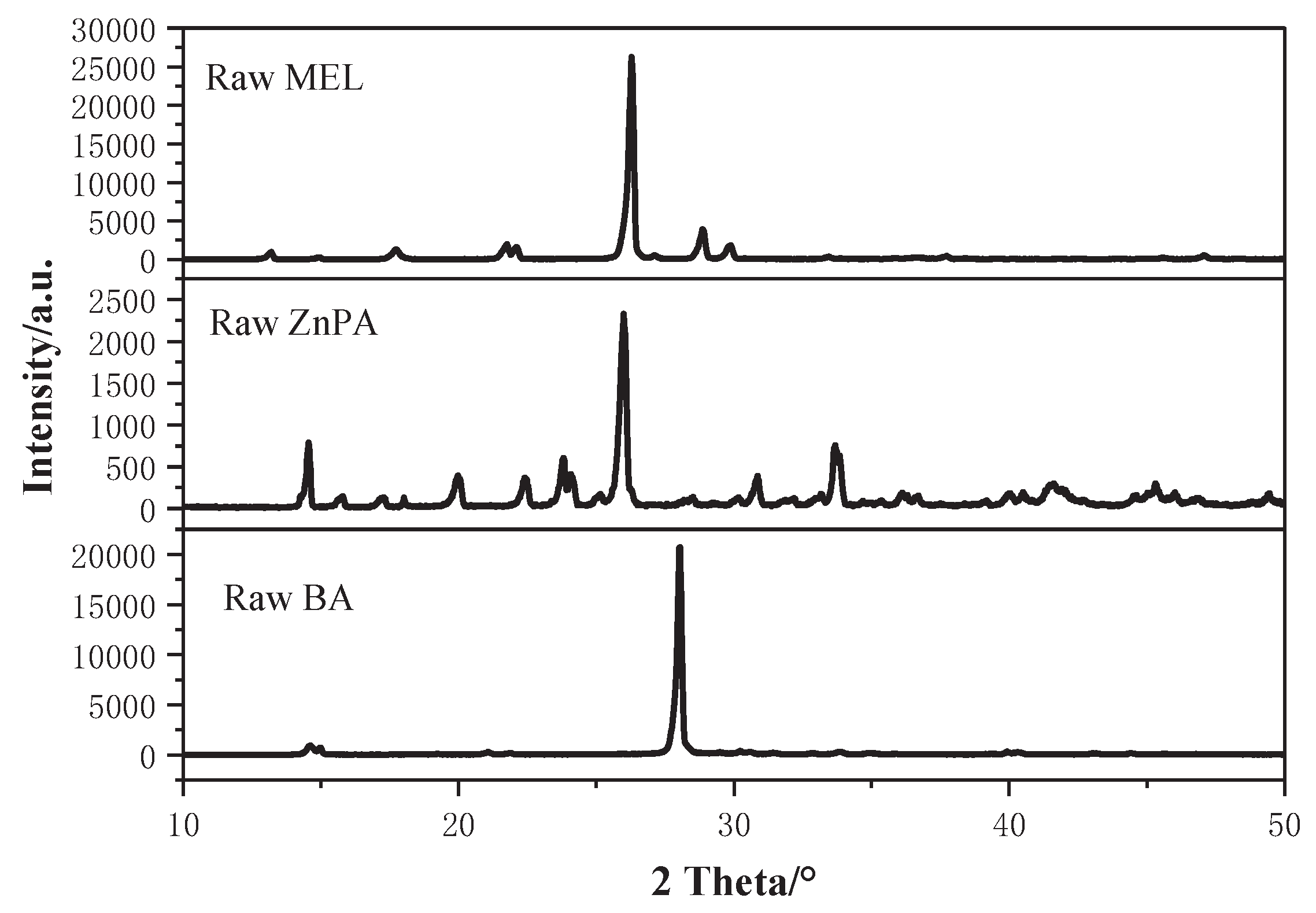

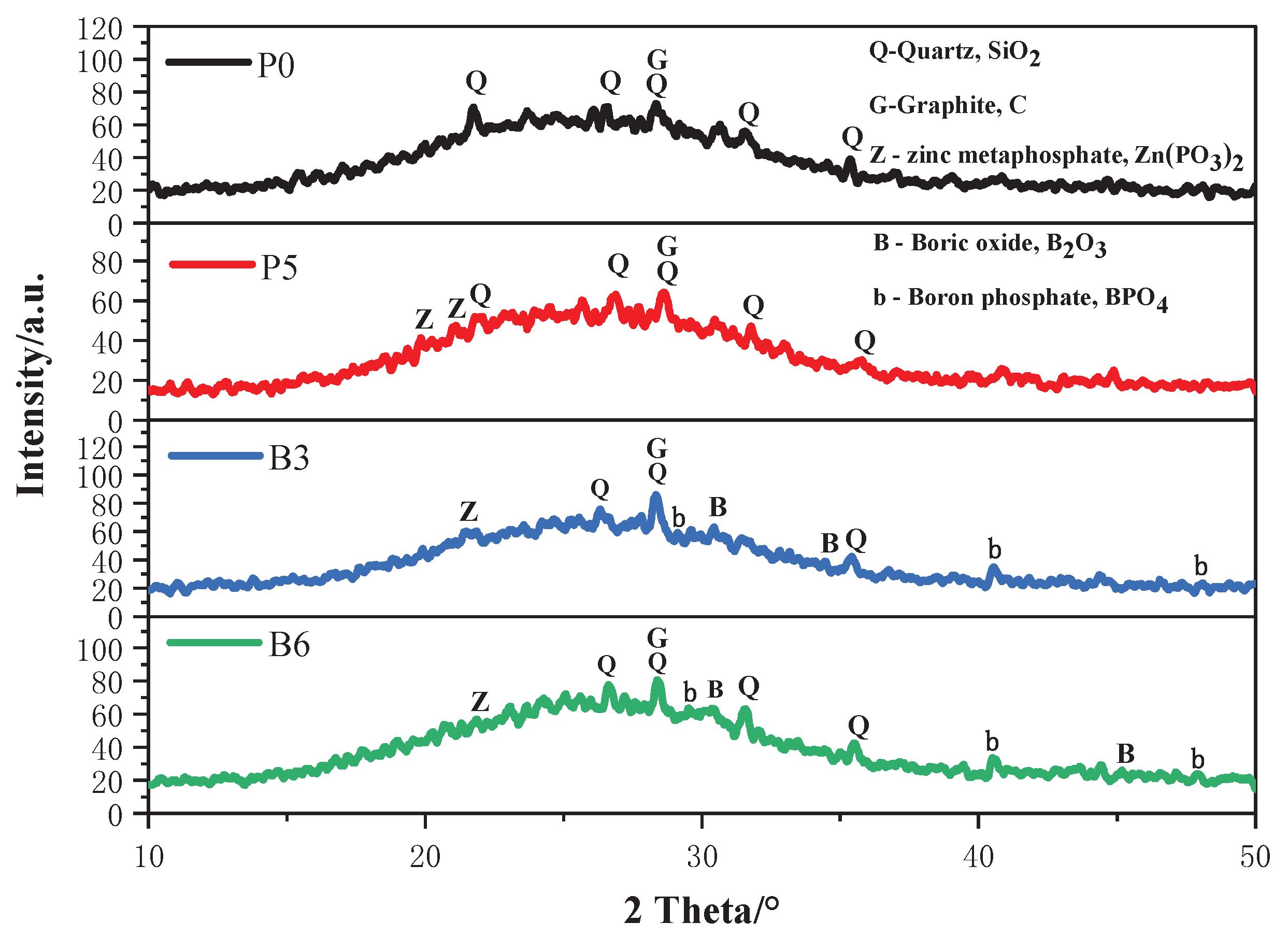

3.3. XRD Analysis

Figure 4 depicts the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the raw materials.

Figure 5 presents the XRD of the residual silica fume-based geopolymer coatings after combustion. A broad hump observed between 15-35° at 2θ suggests a high content of amorphous silicates, which contributes to enhanced flame retardancy. Overlaid upon this broad hump, discrete peaks correspond to quartz (SiO

2, PDF No. 46-1441, No. 04-0379), graphite (G, PDF No. 05-0625), zinc metaphosphate (Zn(PO

3)

2, PDF No. 01-0587), boric oxide (B

2O

3, PDF No. 46-1045) and boron phosphate (BPO

4, PDF No. 12-0380). Notably, the diffraction peaks at 29.12° and 40.56° are attributed to the hexagonal structure BPO

4. However, peaks corresponding to melamine and its derivatives are not detected, possibly due to their complete decomposition at high temperatures.

Essentially, ZnPA decomposes into phosphoric acid and Zn(PO

3)

2 During firing, while releasing CO

2 through a dehydration process [

17], as shown in reaction (4). Subsequently, the partial generated phosphoric acid dehydrates into polyphosphoric acid, which then further dehydrates into P

2O

5 [

29] as shown in reactions (5)~(6). BA undergoes dehydration at high temperatures, converting into B

2O

3 [

30], as shown in reaction (7). The generated P

2O

5 further reacts with B

2O

3 and transforms into BPO

4 [

31], as shown in reaction (8), holding high melting point of 1200°C and excellent stability [

32]. The XRD analysis confirms that the doped ZnPA and BA generate in-situ reactions.

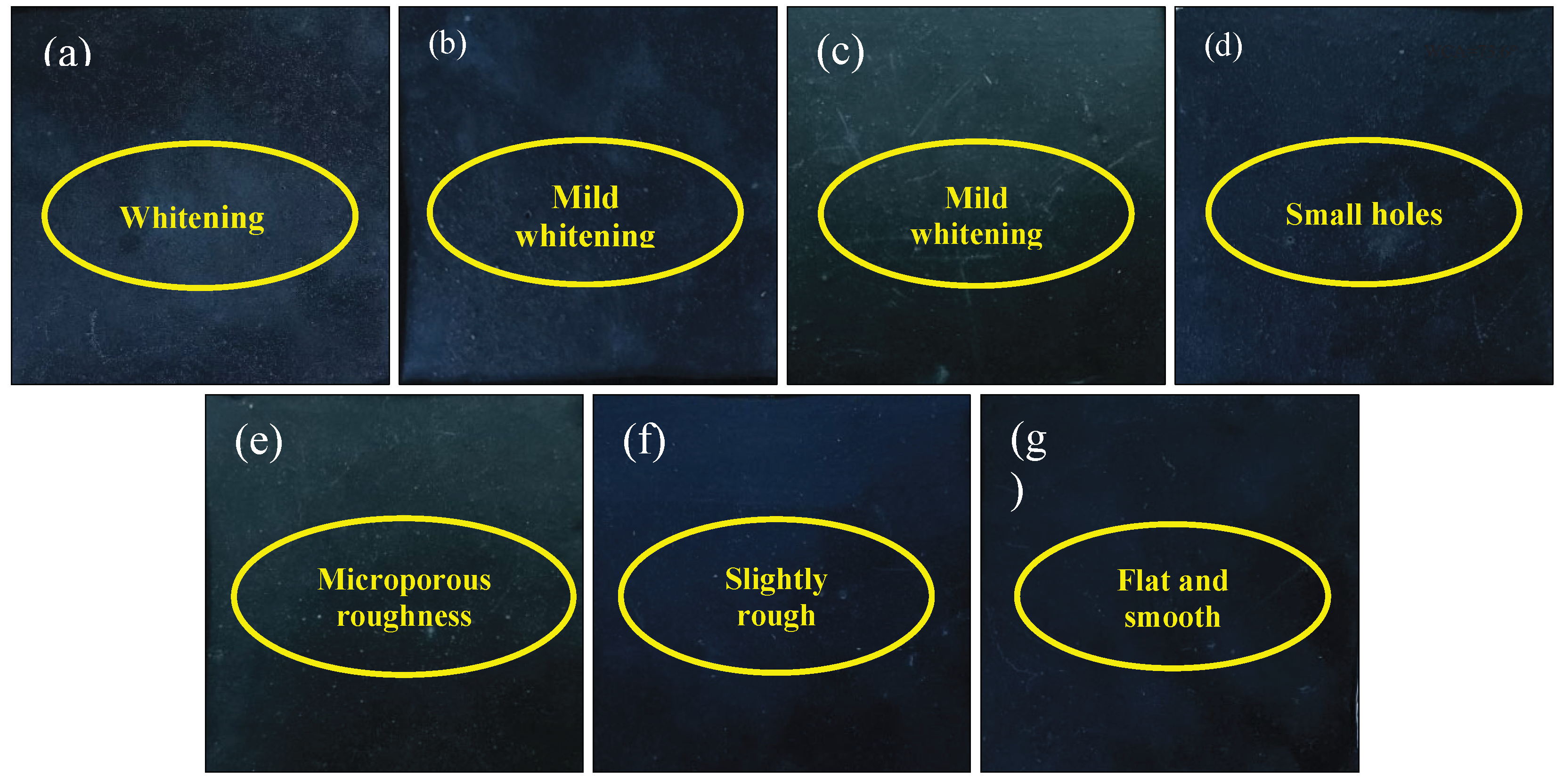

3.4. Appearance

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 illustrate the appearance and WCA of the composite coatings before burning, the coating without ZnPA and BA appears slightly whitening in

Figure 6a. Because MEL is an alkaline compound [

33], resulting in excessive alkali content in the coating. With the increase in the dosage of ZnPA, the whitening phenomenon diminishes in

Figure 6b~g. After the addition of BA, the white powders are dispersed on the surface in

Figure 6a-e. This phenomenon becomes obvious with the increasing BA dosage. Especially, when the content of BA reaches 3.0 wt.%, a rough surface with white small particle aggregation appears in

Figure 6e.

3.5. Residual Appearance of Samples

All samples form a siliceous layer [

34], as shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. This layer effectively inhibits flame propagation and traps the transfer of heat and mass, thereby safeguarding the underlying plywood against complete combustion. In

Figure 8a, the siliceous layer is inherently brittle and fragile. As shown in

Figure 8b~e, the coating hardly swells with low content of ZnPA.

The surface of the layer is convex unevenly, which affects the flame retardancy of samples and its heat release rate, evidenced by the high oxygen consumption. A continuous swelling layer is observed with the increasing content of ZnPA. Especially for the P5 in

Figure 8f, the siliceous layer is uniform expansion, continuous, and intact, but small cracks could be observed on the surface of the layer. When the content of ZnPA reaches 3.0 wt.% in

Figure 8g, cracks are observed, which are averse to the formation of the intact layer. When the dosage of BA continues to be added, the siliceous layer is in a collapsed state after combustion in

Figure 9a and

Figure 9b. However, with the addition of 1.5 wt.% BA, the unbroken, smooth, and robust homogeneous barrier layer is generated for B3 in

Figure 9c, and the smooth surface is observed, indicating that a resilient swelling siliceous layer is formed. When the BA content exceeds 1.5 wt.%, the inhomogeneous barrier layer emerges in

Figure 9d-f, leading to the diminished flame retardancy.

3.6. SEM of Residues

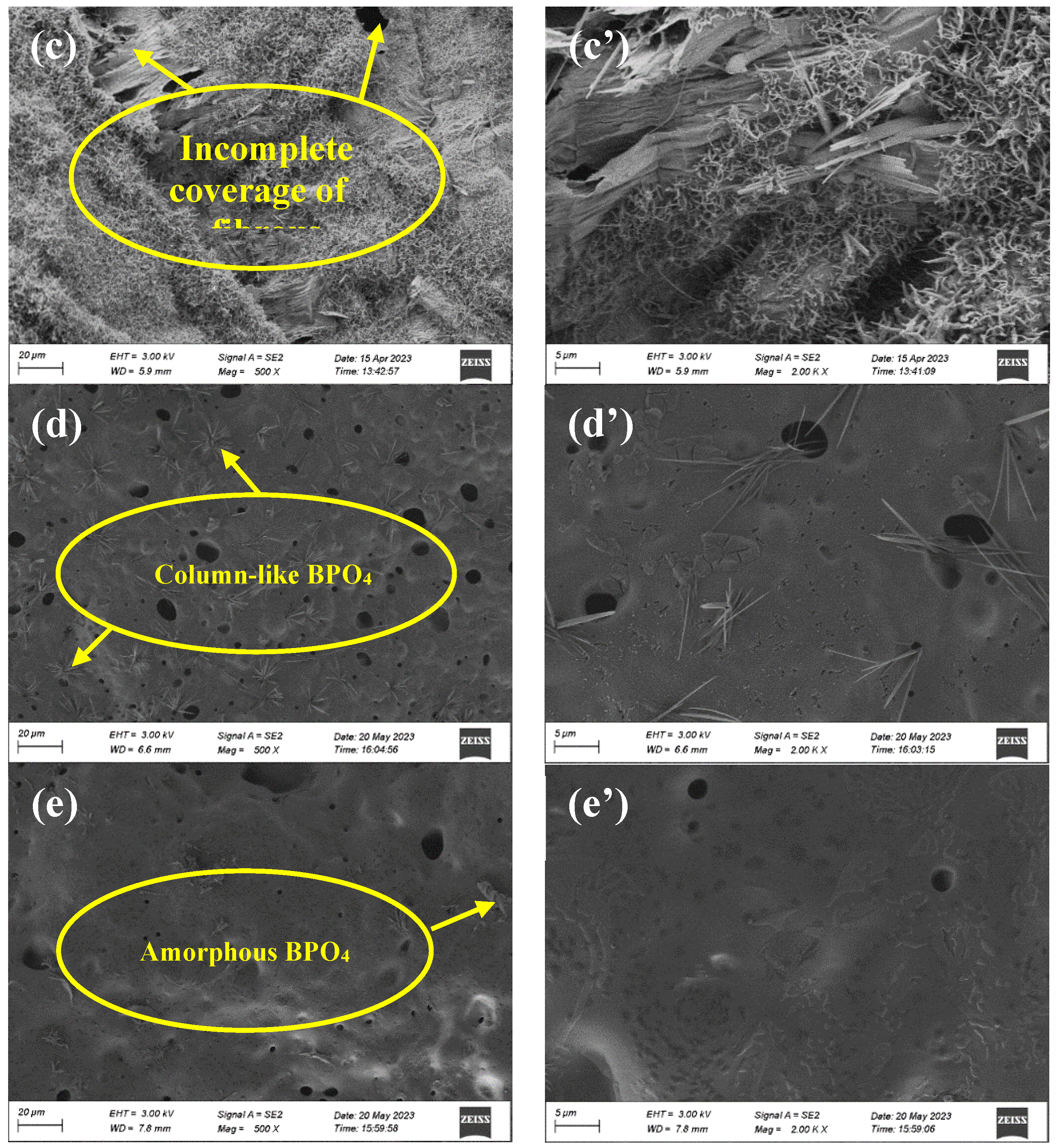

Figure 10 illustrates the microscopic morphology (500x and 2000x) of the surface of the residues after combustion of the composite coatings.

Figure 10 (a, a’) reveals sparse fibrous barriers, covering the fractured and discontinuous siliceous layer. This layer is easily penetrated by gases produced from pyrolysis and cannot effectively prevent the transfer of heat and flammable gases during firing.

When ZnPA is doped into the coating, as shown in

Figure 10 (b, b’), dense fibrous barriers appear on the surface of the barrier layer, delaying flame propagation and preventing volatile gases and liquid small molecules from entering the combustion zone. When adding an excessive dosage of ZnPA, the coverage of the fibrous decreases in

Figure 10 (c, c’), which adversely affects the flame retardancy.

Figure 10 (d, d’) shows the formation of column-like BPO

4 on the surface of the B3 siliceous layer. During combustion, BA and ZnPA decompose, producing phosphate and borate, respectively, which further react to form column-like BPO

4. The integration of BPO

4 with the siliceous layer enhances the quality of the barrier layer. Notably, BPO

4 typically adopts a cristobalite-like structure [

35]. According to our results, the formed BPO

4 exhibits a column-like structure, a discrepancy that may stem from varying conditions during BPO

4 crystal growth, leading to a diversity of crystal structures [

36]. The column-like BPO

4 increases the surface area of the siliceous layer, hindering heat transfer and protecting the underlying plywood from combustion. Meanwhile, the porous surface of the barrier layer facilitates the volatiles’ release into the surrounding air. However, an excess BA results in reduced BPO

4 on the surface of the siliceous layer, exhibiting an irregular and amorphous structure, leading to the poor flame retardancy. Therefore, the ZnPA (2.5 wt.%) and BA (1.5 wt.%) lead to the in-situ formation of BPO

4, enhancing the toughness of the barrier layer. In addition, the combination of BPO

4 and siliceous layer forms the resilient and smooth residual layer, thereby improving the flame retardancy of the composite coating.

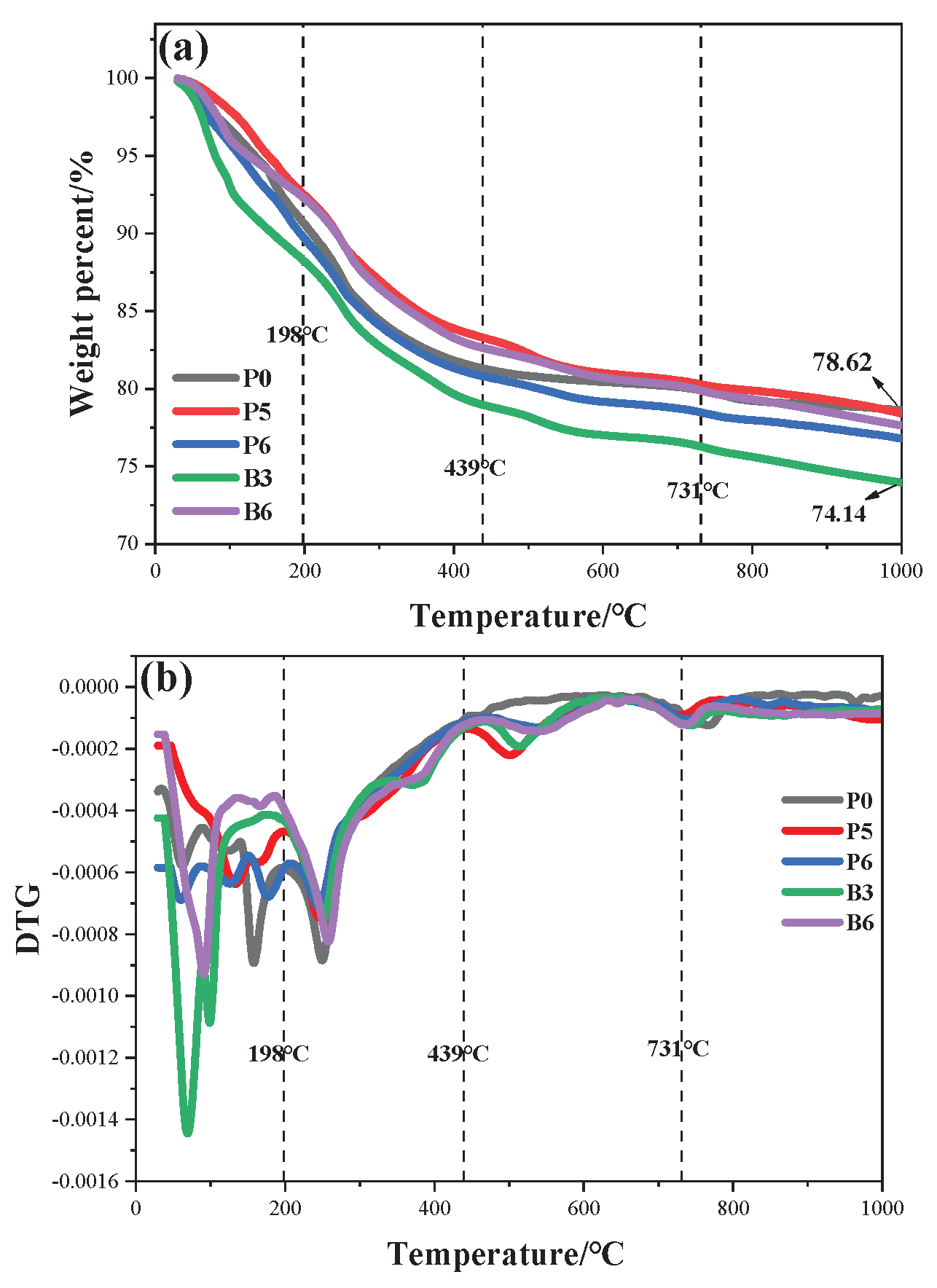

3.7. Thermal Performance Analysis

According to the thermal performance analysis, 5% weight loss temperature (T

d5%), 10% weight loss temperature (T

d10%), 20% weight loss temperature (T

d20%), the initial degradation temperature (T

i), final degradation temperature (T

f), and the corresponding maximum weight loss temperature (T

max) and carbon residue rate of the samples are expressed in

Table 3. The comparison reveals that B3 has better thermal stability, because the reaction of ZnPA and BA forms BPO

4 with high thermal stability [

37], thereby blocking the heat transfer further.

Figure 11a shows the TG curves for the geopolymer coatings, depicting temperature variations at a constant heating rate of 20°C/min. With the addition of ZnPA and BA, continuous weight loss is observed in all samples during the heating process ranging from 30 to 1000°C. It may be attributed to the thermal decomposition of ZnPA produces phosphorous compounds, accelerating the dehydration of composite coatings [

38]. The formation of BPO

4 has catalysis [

39] advancing the decomposition of the siliceous layer, consequently reducing the weight loss of the residues.

Figure 11b presents the DTG of the sample coatings. The whole pyrolysis process could be categorized into four stages: (I) 30-198℃, (II) 198-439℃, (III) 439-731℃, and (IV) 731-1000℃. In the first stage of 30-198℃, weight loss is primarily attributed to the loss of free water and bound moisture from the coating. In the temperature range of 198-439°C, the primary reactions involve the decompositions of ZnPA and MEL. MEL releases inert gases such as NH

3 [

40]. ZnPA decomposes within this temperature range, forming pyrophosphate, metaphosphate, and metal phosphate [

41]. After adding BA, BA dehydrates and forms vitreous boron oxide. With the increase in temperature, the third stage occurs at 439-731°C, primarily due to the thermal decomposition of polyphosphoric acid and the formation of the blocking layer. The final stage occurs between 731-1000°C, mainly attributed to the decomposition of the blocking layer and the formation of BPO

4. Moreover, some unreacted boride and pyrolysis products of ZnPA volatilize at high temperatures. In summary, ZnPA and BA form BPO

4 at high temperatures on the surface of the siliceous layer, which improves the flame retardancy of the composite coating.

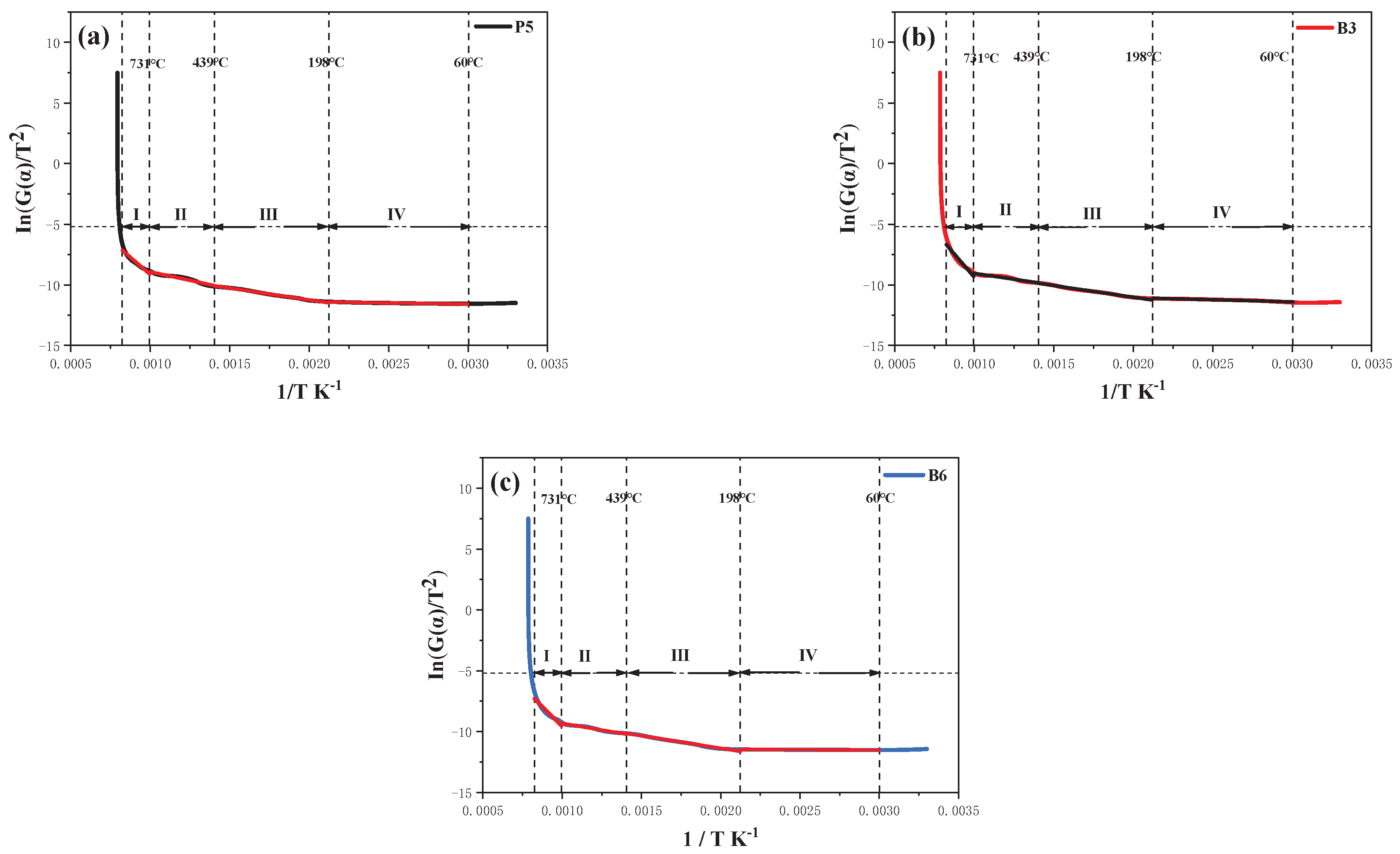

3.8. Pyrolysis Kinetics

Pyrolysis kinetics is the study of the rate at which a material undergoes decomposition or chemical reactions during heating, to obtain the reaction mechanism, action energy, and pyrolysis kinetics parameter. Using the modified Coats-Redfern integral method, the thermal decomposition kinetics of the coating is calculated using formulas (9)-(13). The plot of ln[G(α)/T

2]-1/T relationship is generated. The activation energy

Eα and correlation coefficient R

2 are obtained by linear regression fitting of the curve.

The n is the reaction order of combustion. A is the preexponent factor in units of min-1. Eα is the catalytic activation energy, measured in kilojoules per mole(kJ·mol-1); R is the ideal gas constant, 8.3145 J·mol-1·K-1; β is the heating rate of 20°C·min-1; T is the thermodynamic temperature in units of K; The α is the weight conversion rate of sample during pyrolysis,%, m0 represents the initial mass of the sample, mt is the real-time mass of the coating at time, and mf corresponds to the final remaining mass of the sample.

By performing calculations and screening among the 29 commonly used mechanism functions [

42], the three-level chemical reaction model (F3) is chosen to plot the curves, as illustrated in

Figure 12. Then, according to the fitting results, the calculated kinetic parameter

Eα value and R

2 are both within a reasonable rage. The pyrolysis is mainly divided into the following five stages as shown in

Table 4, including (IV) 60-198°C, (III) 198-439°C, (II) 439-731°C, and (I) 731-940°C. Stage IV is mainly the volatilization of small molecular substances. In comparison to P5, the

Eα of B3 is decreased to 15.94 kJ·mol

-1 in stage III and 16.04 kJ·mol

-1 in stage II, respectively. Thermal decomposition of BA and ZnPA catalyzes the thermal degradation and carbonization of the coating. The

Eα of B3 is 127.08 kJ·mol

-1 in the range of 731-940°C, indicating that BA and ZnPA react with the geopolymer to form a dense siliceous barrier layer with BPO

4, preventing plywood from coming into contact with air and enhancing the flame retardancy of coatings.

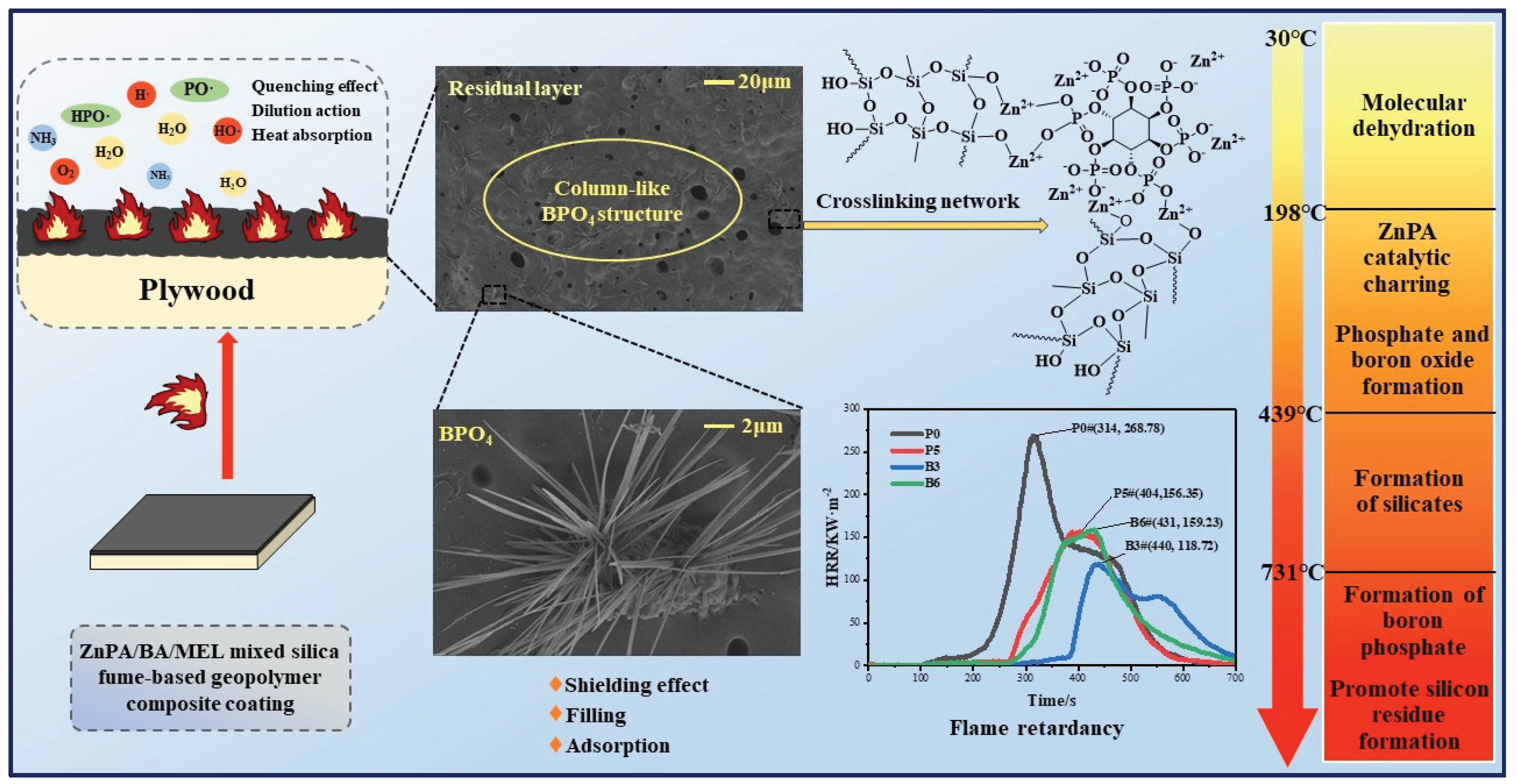

4. Discussion

In this research, an alkali-activated silica fume-based composite coating is optimized by incorporating MEL, ZnPA, and BA, to enhance its flame retardancy. Various characterization techniques, including CC, XRD, SEM, and TG, are employed to analyze the coating. The results indicate that the optimal combination of BA and ZnPA significantly improves the flame retardancy. The flame-retardant mechanism of ZnPA/BA/MEL-containing silica fume-based coatings is summarized as follows:

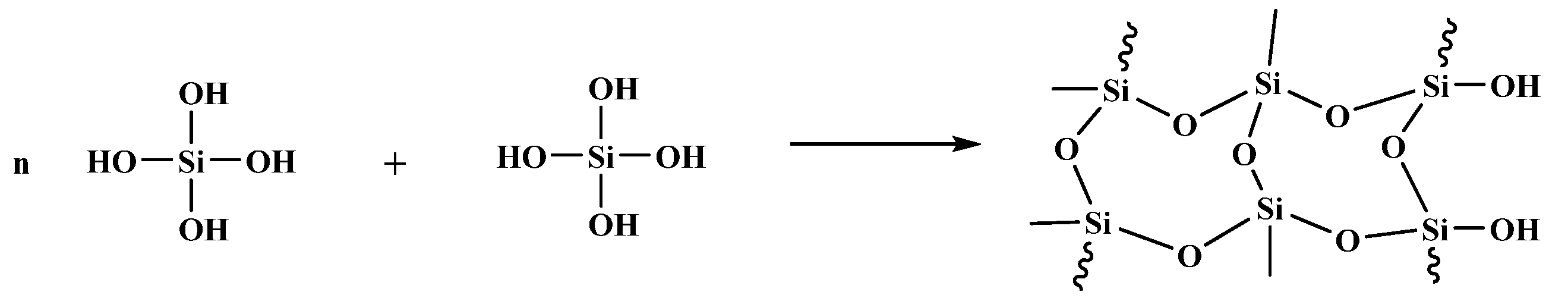

Firstly, the condensation reactions and the formation of coordination bonds are crucial in enhancing the flame retardancy of geopolymer coatings. During the combustion of alkali-activated silica fume-based polymer gels, a condensation reaction occurs, which transforms Si[OH]

4 into the Si-O-Si network structure [

43], as shown in the reaction (14). This silicon network structure contributes to the heat dissipation of the coating.

Secondly, zinc ions from ZnPA react with the Si-O-Si structure to form a crosslinking network [

44], as shown in the reaction (15). This crosslinking enhances the strength of the residues [

19]. Additionally, ZnPA enhances flame retardancy by generating phosphorus-containing free radicals that quench the pyrolysis process [

45]. The production of phosphoric acid, polyphosphoric acid, and metal phosphates catalyzes the formation of residual layers.

Furthermore, BA helps in reducing the surface temperature of the coating by producing B

2O

3 and water. Furthermore, zinc ions and boron can enhance charring [

46,

47]. Moreover, MEL accelerates the production of polyphosphoric acid [

48], and releases inert gases, such as NH

3. These gases dilute the concentration of combustible gases and O

2 in the vicinity, reducing the combustion intensity.

Thirdly, the synergistic interaction between BA and ZnPA promotes the formation of highly thermally stable BPO

4. BPO

4 forms a ceramic shielding layer atop the siliceous layer in

Figure 10. This additional layer significantly enhances the physical barrier properties of the siliceous layer. Moreover, BPO

4 has a filling effect, strengthening the structural integrity of the residual layer and forming a dense residual layer [

49]. This layer acts as a barrier to heat transfer, thereby protecting the underlying plywood. In addition, BPO

4 increases the surface area of the siliceous layer. Similar to the findings of Decsov et al. [

50], who changed the specific surface area of 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HP-β-CD) microfibers, leading to an increase in the flame-retardant index of the composites. Thus, BPO

4 introduces more active sites on the surface of the barrier layer. It adsorbs flammable organic volatiles, preventing their release and diffusion during combustion, and therefore reducing the rate of flame spread.

Consequently, the synergistic flame-retardant mechanism of silica fume-based composite coatings, as illustrated in

Figure 13, primarily involves the quenching effect, dilution action, heat absorption, and catalytic charring of coatings. The interpenetrating network structure and BPO

4 promote the generation of a continuous and robust siliceous layer that acts as a barrier. However, the complex reaction mechanism among ZnPA, BA, MEL, and geopolymer, as well as the smoke suppression performance of the composite coating, will be investigated in our subsequent research.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, the flame retardancy of ZnPA/BA/MEL-containing silica fume-based geopolymer coatings is investigated preliminarily. The following conclusions are drawn:

(1) ZnPA (2.5 wt.%) and BA (1.5 wt.%) enhance the flame retardancy of silica fume-based geopolymer coating, evidenced by that the FPI increases from 0.59 (P0) to 2.83 (B3) s·m-2·kW-1, the FGI decreases from 0.86 (P0) to 0.27 (B3) kW m-2·s-1, and the FRI of 8.48.

(2) The in-situ formed boron phosphate (BPO4) derived from the doped ZnPA and BA facilitates interpenetrating networks within siliceous gels, improving the residual resilience of the fire-barrier layer, which can shield, fill, and adsorb heat during firing.

(3) According to pyrolysis kinetic calculation, in-situ formation of BPO4 makes the Eα climb from 94.28 (P5) to 127.08 kJ·mol-1 (B3) during 731-940°C, effectively corresponding to the improved flame retardancy.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by Opening Projects of State Key Laboratory of Green and Low-carbon Development of Tar-rich Coal in Western China (SKLCRKF23-08), the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (2025JC-YBMS-560), and the open fund from Anhui Engineering Research Center for Coal Clean Processing and Carbon Reduction y (CCCE-2024007).

References

- Dong, X.; Gan, W.; Shang, Y.; Tang, J.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Z.; Xie, Y.; Liu, J.; Bai, L.; Li, J.; et al. Low-value wood for sustainable high-performance structural materials. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ma, T.; Wang, Q.; Guo, C. Synthesis of Biobased Flame-Retardant Carboxylic Acid Curing Agent and Application in Wood Surface Coating. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 14727–14738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kaseasbeh, Q.; Al-Qaralleh, M. Valorization of hydrophobic wood waste in concrete mixtures: Investigating the micro and macro relations. Results Eng. 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykam, K.; Hussain, S.S.; Sivanandan, S.; Narayan, R.; Basak, P. Non-halogenated UV-curable flame retardants for wood coating applications: Review. Prog. Org. Coatings 2023, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Shen, A.; Guo, Y.; Lyu, Z.; Li, D.; Qin, X.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z. Cement-based materials modified with superabsorbent polymers: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 225, 569–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Xu, M.-R.; Dai, J.-G.; Dong, B.-Q.; Zhang, M.-J.; Hong, S.-X.; Xing, F. Strengthening concrete using phosphate cement-based fiber-reinforced inorganic composites for improved fire resistance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 212, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, R.; Choudhary, K.; Srivastava, A.; Sangwan, K.S.; Singh, M. Environmental impact assessment of fly ash and silica fume based geopolymer concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, S.; Mohammadi, S. Synergistic effect of nano hybrid multi-layered graphene oxide/talc and silica fume on the fire and water -resistance of intumescent coatings. Prog. Org. Coatings 2023, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhu, H.; Wu, Q.; Yang, T.; Yin, Z.; Tian, L. Investigation of the hydrophobicity and microstructure of fly ash-slag geopolymer modified by polydimethylsiloxane. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yang, Q. Engineering and microstructural properties of carbon-fiber-reinforced fly-ash-based geopolymer composites. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Członka, S.; Strąkowska, A.; Strzelec, K.; Kairytė, A.; Kremensas, A. Melamine, silica, and ionic liquid as a novel flame retardant for rigid polyurethane foams with enhanced flame retardancy and mechanical properties. Polym. Test. 2020, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, P. Flame retardant cotton fabrics with anti-UV properties based on tea polyphenol-melamine-phenylphosphonic acid. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 629, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, G.; Huo, S.; Wang, C.; Shi, Q.; Yu, L.; Liu, Z.; Fang, Z.; Wang, H. A novel hyperbranched phosphorus-boron polymer for transparent, flame-retardant, smoke-suppressive, robust yet tough epoxy resins. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2021, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Mao, Y.; Wang, D.; Fu, S. B-N-P-linked covalent organic frameworks for efficient flame retarding and toxic smoke suppression of polyacrylonitrile composite fiber. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Peng, Y.; Wang, W.; Cao, J. Thermal behavior and flame retardancy of poplar wood impregnated with furfuryl alcohol catalyzed by boron/phosphorus compound system. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, S.; Sai, T.; Ran, S.; Guo, Z.; Fang, Z.; Song, P.; Wang, H. A hyperbranched P/N/B-containing oligomer as multifunctional flame retardant for epoxy resins. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2022, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Ding, M.; Huang, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, M. In-situ incorporation of metal phytates for green and highly efficient flame-retardant wood with excellent smoke-suppression property. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Xiao, Y.; Qian, Z.; Yang, Y.; Jia, P.; Song, L.; Hu, Y.; Ma, C.; Gui, Z. A novel phosphorus-, nitrogen- and sulfur-containing macromolecule flame retardant for constructing high-performance epoxy resin composites. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Zhao, J. In-situ polymerized zinc phytate chelated Si-C-P geopolymer hybrid coating constructed by incorporating chitosan oligosaccharide and DOPO for flame-retardant plywood. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, M.; Dogan, S.D.; Savas, L.A.; Ozcelik, G.; Tayfun, U. Flame retardant effect of boron compounds in polymeric materials. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2021, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, S.; Meng, D.; Chen, D.; Mu, C.; Li, H.; Sun, J.; Gu, X.; Zhang, S. A facile preparation of environmentally-benign and flame-retardant coating on wood by comprising polysilicate and boric acid. Cellulose 2021, 28, 11551–11566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savas, L.A.; Dogan, M. Flame retardant effect of zinc borate in polyamide 6 containing aluminum hypophosphite. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 165, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Luo, K.; Zhang, K.; He, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, D. Combinatorial Vibration-Mode Assignment for the FTIR Spectrum of Crystalline Melamine: A Strategic Approach toward Theoretical IR Vibrational Calculations of Triazine-Based Compounds. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 7427–7433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, H.R.; Prasad, R.; Khan, M.R.; Chowdhury, N.K. Effect of Palm Kernel Meal as Melamine Urea Formaldehyde Adhesive Extender for Plywood Application: Using a Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Study. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 121-126, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Song, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, S.; Qi, H. A novel strategy to enhance hydrothermal stability of Pd-doped organosilica membrane for hydrogen separation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 253, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carli, L.; Schnitzler, E.; Ionashiro, M.; Szpoganicz, B.; Rosso, N.D. Equilibrium, thermoanalytical and spectroscopic studies to characterize phytic acid complexes with Mn(II) and Co(II). J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2009, 20, 1515–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbeyli, I.Y. Production of crystalline boric acid and sodium citrate from borax decahydrate. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 158, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Zhao, J. In-situ grown SiC whiskers enhance flame retardancy of alkali-activated gold tailings geopolymer composite coatings by incorporating expanded graphite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Yao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, M.; Ren, J.; Zhang, C.; Wu, F.; Lu, J. Evolution of the porous structure for phosphoric acid etching carbon as cathodes in Li–O2 batteries: Pyrolysis temperature-induced characteristics changes. Carbon Energy 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, E.; Donzel-Gargand, O.; Heinrichs, J.; Jacobson, S. Tribofilm formation of a boric acid fuel additive – Material characterization; challenges and insights. Tribol. Int. 2022, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Xia, H.; Hou, X.; Yang, T.; Si, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Shi, Z. Enhanced thermal management performance of nanofibrillated cellulose composite with highly thermally conductive boron phosphide. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 27049–27060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Ahmad, F.; Shariff, A.M.; Bustam, M.A.; Gonfa, G.; Gillani, Q.F. Effects of ammonium polyphosphate and boric acid on the thermal degradation of an intumescent fire retardant coating. Prog. Org. Coatings 2017, 109, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.-M.; Zhang, T.; Yang, M.-Z.; Zhang, Q. Preparation and characterization of novel melamine modified poly(urea–formaldehyde) self-repairing microcapsules. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2010, 371, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Pan, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Lun, Z.; Gong, L.; Gao, M.; Zhang, H. “Robust–Soft” Anisotropic Nanofibrillated Cellulose Aerogels with Superior Mechanical, Flame-Retardant, and Thermal Insulating Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 27458–27470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, L.; Bin Hong, W.; Yan, H.; Wu, S.Y.; Chen, X.M. Preparation and microwave dielectric properties of BPO4 ceramics with ultra-low dielectric constant. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021, 32, 6660–6667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Ewald, B.; Prots, Y.; Cardoso-Gil, R.; Armbrüster, M.; Loa, I.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y.; Schwarz, U.; Kniep, R. Growth and Characterization of BPO4Single Crystals. Z. Fur Anorg. Und Allg. Chem. 2004, 630, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Duan, H.; Ji, S.; Ma, H. Novel phosphorus/nitrogen/boron-containing carboxylic acid as co-curing agent for fire safety of epoxy resin with enhanced mechanical properties. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 402, 123769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Lu, Z. Preparation of synergistic silicon, phosphorus and nitrogen flame retardant based on cyclosiloxane and its application to cotton fabric. Cellulose 2021, 28, 8115–8128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, J.-Y.; Yang, X.-M.; Wang, Y.-L.; Hao, J.-W. Application of TG/FTIR TG/MS and cone calorimetry to understand flame retardancy and catalytic charring mechanism of boron phosphate in flame-retardant PUR–PIR foams. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 130, 1817–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifulco, A.; Parida, D.; Salmeia, K.A.; Nazir, R.; Lehner, S.; Stämpfli, R.; Markus, H.; Malucelli, G.; Branda, F.; Gaan, S. Fire and mechanical properties of DGEBA-based epoxy resin cured with a cycloaliphatic hardener: Combined action of silica, melamine and DOPO-derivative. Mater. Des. 2020, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Luković, M.; Mendoza, M.; Schlepütz, C.M.; Griffa, M.; Xu, B.; Gaan, S.; Herrmann, H.; Burgert, I. Bioinspired Struvite Mineralization for Fire-Resistant Wood. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 5427–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Yu, Y.; Wang, S. Comparison of the thermal degradation behaviors and kinetics of palm oil waste under nitrogen and air atmosphere in TGA-FTIR with a complementary use of model-free and model-fitting approaches. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2018, 134, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Liu, S.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Feng, J. Excellent antioxidizing, thermally insulating and flame resistance silica-polybenzoxazine aerogels for aircraft ablative materials. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, S.S.; Singh, S.; Rao, D.S.; Nayak, B.B.; Mishra, B.K. Adsorption of heavy metals on a complex Al-Si-O bearing mineral system: Insights from theory and experiments. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 186, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wu, W.; Meng, W.; Xie, W.; Cui, Y.; Xu, J.; Qu, H. Core-Shell Graphitic Carbon Nitride/Zinc Phytate as a Novel Efficient Flame Retardant for Fire Safety and Smoke Suppression in Epoxy Resin. Polymers 2020, 12, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, J.; Lai, Y.; Ren, J.; Wang, Y.; Feng, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Dong, H.; Chen, W.; Jiao, C.; et al. Zn-doped carbon microspheres as synergist in intumescent flame-retardant thermoplastic polyurethane composites: Mechanism of char residues layer regulation. Compos. Commun. 2022, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Zhao, X.; Feng, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhou, K.; Shi, Y.; Liu, C.; Xie, X. Highly flame-retardant epoxy-based thermal conductive composites with functionalized boron nitride nanosheets exfoliated by one-step ball milling. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Zhao, Q.; Zhu, T.; Bo, C.; Zhang, M.; Hu, L.; Zhu, X.; Jia, P.; Zhou, Y. Biobased coating derived from fish scale protein and phytic acid for flame-retardant cotton fabrics. Mater. Des. 2022, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Wen, X.; Zhu, Y.; Lou, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Tang, T. Boron-doped copper phenylphosphate as temperature-response nanosheets to fabricate high fire-safety polycarbonate nanocomposites. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decsov, K.; Takács, V.; Marosi, G.; Bocz, K. Microfibrous cyclodextrin boosts flame retardancy of poly(lactic acid). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 191, 109655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The preparation diagrams of the geopolymer composite coatings.

Figure 1.

The preparation diagrams of the geopolymer composite coatings.

Figure 2.

Flame retardancy of samples including (a) HRR, (b) smoke temperature, (c) residual O2 concentration, and (d) residual weight, respectively.

Figure 2.

Flame retardancy of samples including (a) HRR, (b) smoke temperature, (c) residual O2 concentration, and (d) residual weight, respectively.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra before burning.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra before burning.

Figure 4.

XRD of raw materials.

Figure 4.

XRD of raw materials.

Figure 5.

XRD of coating residues after burning.

Figure 5.

XRD of coating residues after burning.

Figure 6.

Appearance and WCA of samples including (a)P0, (b)P1, (c)P2, (d)P3, (e)P4, (f)P5, and (g)P6, respectively.

Figure 6.

Appearance and WCA of samples including (a)P0, (b)P1, (c)P2, (d)P3, (e)P4, (f)P5, and (g)P6, respectively.

Figure 7.

Appearance and WCA of samples including (a)B1, (b)B2, (c)B3, (d)B4, (e)B5, and (f)B6, respectively.

Figure 7.

Appearance and WCA of samples including (a)B1, (b)B2, (c)B3, (d)B4, (e)B5, and (f)B6, respectively.

Figure 8.

Residual appearance of the sample in CC including (a)P0, (b)P1, (c)P2, (d)P3, (e)P4, (f)P5, and (g)P6, respectively.

Figure 8.

Residual appearance of the sample in CC including (a)P0, (b)P1, (c)P2, (d)P3, (e)P4, (f)P5, and (g)P6, respectively.

Figure 9.

Residual appearance of the sample in CC including (a)B1, (b)B2, (c)B3, (d)B4, (e)B5, and (f)B6, respectively.

Figure 9.

Residual appearance of the sample in CC including (a)B1, (b)B2, (c)B3, (d)B4, (e)B5, and (f)B6, respectively.

Figure 10.

SEM of the surface of residues including (a, a’) P0, (b, b’) P5, (c, c’) P6, (d, d’) B3, and (e, e’) B6, respectively.

Figure 10.

SEM of the surface of residues including (a, a’) P0, (b, b’) P5, (c, c’) P6, (d, d’) B3, and (e, e’) B6, respectively.

Figure 11.

TG/DTG curves of samples including (a) TG and (b) DTG, respectively.

Figure 11.

TG/DTG curves of samples including (a) TG and (b) DTG, respectively.

Figure 12.

Fitting pyrolysis kinetics of sample coatings including (a) P5, (b) B3, and (c) B6, respectively.

Figure 12.

Fitting pyrolysis kinetics of sample coatings including (a) P5, (b) B3, and (c) B6, respectively.

Figure 13.

Flame-retarding mechanism of composite coatings.

Figure 13.

Flame-retarding mechanism of composite coatings.

Table 1.

The composition of coating samples.

Table 1.

The composition of coating samples.

| Samples |

Na2SiO3·9H2O/g |

KOH

/g |

Silica fume

/g |

KH-550

/g |

MEL

/g |

PAM

/g |

H2O

/g |

PDMS

/g |

ZnPA

/g |

BA

/g |

P0

P1

P2

P3

P4

P5

P6

B1

B2

B3

B4

B5

B6 |

14.21

14.21

14.21

14.21

14.21

14.21

14.21

14.21

14.21

14.21

14.21

14.21

14.21 |

5.61

5.61

5.61

5.61

5.61

5.61

5.61

5.61

5.61

5.61

5.61

5.61

5.61 |

30

30

30

30

30

30

30

30

30

30

30

30

30 |

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5 |

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1 |

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2 |

45

45

45

45

45

45

45

45

45

45

45

45

45 |

0.25

0.25

0.25

0.25

0.25

0.25

0.25

0.25

0.25

0.25

0.25

0.25

0.25 |

0.48

0.95

1.43

1.9

2.38

2.85

2.38

2.38

2.38

2.38

2.38

2.38

2.38 |

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0 |

Table 2.

Combustion parameters of samples in CC.

Table 2.

Combustion parameters of samples in CC.

| Samples |

TTI

/s |

TP

/s |

p-HRR

/kW·m-2

|

FPI

/s·m2·kW-1

|

FGI

/kW·m-2·s-1

|

WL

/g |

THR /MJ·m-2

|

AEHC

/kW·kg-1

|

FRI |

| P0 |

158 |

314 |

268.78 |

0.59 |

0.86 |

30.93 |

36.67 |

1.19 |

1.00 |

| P1 |

219 |

308 |

242.31 |

0.90 |

0.79 |

29.16 |

31.27 |

1.07 |

1.80 |

| P2 |

201 |

319 |

234.90 |

0.86 |

0.74 |

29.93 |

35.93 |

1.20 |

1.49 |

| P3 |

232 |

321 |

223.93 |

1.04 |

0.70 |

26.04 |

27.92 |

1.07 |

2.31 |

| P4 |

205 |

364 |

213.97 |

0.96 |

0.59 |

24.56 |

27.79 |

1.13 |

2.15 |

| P5 |

228 |

404 |

156.35 |

1.46 |

0.39 |

27.12 |

27.79 |

1.02 |

3.27 |

| P6 |

78 |

348 |

215.41 |

0.36 |

0.62 |

31.37 |

40.44 |

1.29 |

0.56 |

| B1 |

266 |

414 |

147.49 |

1.80 |

0.36 |

26.84 |

22.42 |

0.84 |

5.02 |

| B2 |

294 |

423 |

131.89 |

2.23 |

0.31 |

29.46 |

23.44 |

0.80 |

5.93 |

| B3 |

336 |

440 |

118.72 |

2.83 |

0.27 |

24.30 |

20.83 |

0.86 |

8.48 |

| B4 |

327 |

453 |

123.31 |

2.65 |

0.27 |

23.90 |

22.62 |

0.95 |

7.31 |

| B5 |

318 |

443 |

128.29 |

2.48 |

0.29 |

25.01 |

20.68 |

0.83 |

7.48 |

| B6 |

260 |

431 |

159.23 |

1.63 |

0.37 |

26.51 |

27.63 |

1.04 |

3.69 |

Table 3.

Pyrolysis parameters of samples.

Table 3.

Pyrolysis parameters of samples.

| Samples |

aTd5%/℃ |

bTd10%/℃ |

cTd20%/℃ |

dTi

|

eTf

|

fTmax/℃ |

Char residue/wt.% |

| P0 |

133.3 |

210.0 |

718.0 |

30 |

998.3 |

250.7 |

78.61 |

| P5 |

151.3 |

243.7 |

774.3 |

30 |

999.3 |

245.0 |

78.40 |

| P6 |

113.3 |

194.0 |

515.0 |

30 |

998.3 |

244.3 |

76.81 |

| B3 |

80.7 |

160.7 |

393.0 |

30 |

997.0 |

252.3 |

74.14 |

| B6 |

125.0 |

243.0 |

721.3 |

30 |

999.0 |

258.7 |

77.64 |

Table 4.

Kinetic parameters of samples calculated using F3.

Table 4.

Kinetic parameters of samples calculated using F3.

| sample |

Temperature |

Intercept |

Slope |

Adj.R2

|

Eα/kJ·mol-1

|

| P5 |

60-198℃ |

-11.02 |

-190.19 |

0.95 |

1.58 |

| |

198-439℃ |

-7.35 |

-1948.92 |

0.99 |

16.20 |

| |

439-731℃ |

-6.13 |

-2800.53 |

0.95 |

23.28 |

| |

731-940℃ |

2.20 |

-11339.87 |

0.94 |

94.28 |

| B3 |

60-198℃ |

-10.40 |

-333.17 |

0.95 |

2.77 |

| |

198-439℃ |

-7.19 |

-1916.77 |

0.99 |

15.94 |

| |

439-731℃ |

-7.13 |

-1929.49 |

0.93 |

16.04 |

| |

731-940℃ |

5.91 |

-15284.84 |

0.93 |

127.08 |

| B6 |

60-198℃ |

11.32 |

-61.67 |

0.94 |

0.51 |

| |

198-439℃ |

-7.24 |

-2062.03 |

0.99 |

17.14 |

| |

439-731℃ |

-7.15 |

-2172.26 |

0.98 |

18.06 |

| |

731-940℃ |

3.42 |

-12986.68 |

0.91 |

107.98 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).