1. Introduction

Urban Green Infrastructures (UGI) and Nature-based Solutions (NBS) have emerged in recent years as a key topic in the debate on urban adaptation to climate change [

1,

2,

3]. The growing evidence of climate change [

4], the intensification of extreme weather events, and the exacerbation of urban risks have made it increasingly urgent to make cities more resilient and better prepared [

5]. The emphasis on these approaches has grown significantly alongside the evolution of research on urban resilience and the adaptation of cities to climate change [

6,

7]. In this regard, the strategic and designed reintroduction of natural components and processes into urbanized environments can offer numerous benefits [

8]: from mitigating the urban heat island effect [

9,

10] to managing stormwater drainage [

11], from reducing air pollution [

12] to positively impacting the psychological and physical well-being of citizens [

13]. Actions aimed at reintroducing nature into cities respond both to the perceived need to restore proximity to nature in fully anthropized environments [

14], and to the practical need to mitigate the limitations of urban settings in addressing increasing risks exacerbated by climate change [

15,

16].

Various interrelated concepts and notions populate the field of urban adaptation and support this process of reintroducing nature into cities. The European Commission defines Green Infrastructure (GI) as “a strategically planned network of natural and semi-natural areas with other environmental features designed and managed to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services.” This definition refers to another fundamental concept, namely that of Ecosystem Services (ES), which are “the benefits societies obtain from ecosystems” [

17], including direct resource consumption (provisioning ES), experiential benefits (cultural ES), and contributions to the overall regulation and maintenance of fundamental environmental conditions for human life (supporting and regulating ES). Based on this understanding of the interactions between humankind and the environment, approaches such as ecosystem-based adaptation (or mitigation) have become increasingly widespread [

18]. Indeed, the aim of NBS is exactly to “bring more, and more diverse, nature and natural features and processes into cities, through locally adapted, resource-efficient and systemic interventions” [

19]. Similarly, the UGI approach supports the systemic planning of urban greenery as part of the key infrastructural networks of a city, responding to the key principles of Connectivity, Multifunctionality, Integration of Green and Gray components; Multi-scale implementation [

20,

21].

The substantial efforts of scientific research—which is contributing to reinforcing and refining these approaches by investigating their effectiveness, methodologies, and applicability—have progressively informed the definition of local policies and strategies. Currently, many international institutions are actively engaged in promoting UGI and NbS at various levels, and this approach has increasingly gained prominence in international agreements concerning environmental protection, climate change mitigation, biodiversity support, and risk management [

22,

23,

24].

However, limitations and barriers to the effective and systematic integration of UGI and NbS into urban planning practice persist. This study specifically focuses on the importance of enhancing citizen engagement—not only through consultative activities in participatory public programs, but also by recognizing citizens as key actors in promoting the expansion of UGI within urban areas. It highlights the value of private open spaces as critical areas for the diffuse, small-scale deployment of UGI across different spatial levels. The following sections offer a perspective on the main barriers to UGI implementation as identified in the literature, and on the relevance of citizens engagement in UGI planning, also introducing the case study of Milan, Italy.

1.1. Barriers to the Advancement of Urban Green Infrastructure

Despite the intense research effort of the past decades, the effective integration of UGI and NbS into urban transformation programs remains highly limited and fragmented [

25] and a systematic adoption of this approach in urban contexts still faces several obstacles and barriers. Referring to Nelson et al. [

26], five main challenges can be identified: 1) Participation and equity, which emphasize the need to consider the dynamic and often uneven perceptions of risk and benefit across different social groups; 2) Governance, as the inherently complex and systemic nature of NbS demands coordination across institutional levels and sectors, posing significant challenges to existing governance frameworks; 3) Valuation, highlighting the need for consistent methodologies to assess and communicate the multifaceted benefits of NbS in economic, environmental, and social terms; 4) Infrastructure integration, which calls for moving beyond the traditional separation between green and grey infrastructure and toward a more holistic and multifunctional understanding of urban systems; 5) Scale and feedback, which stress the importance of trans-scalar planning approaches and the involvement of a broad range of actors to ensure responsiveness to local conditions while aligning with broader sustainability goals. Similarly, Kabisch et al. categorize the critical issues as: i) knowledge and awareness gap, which refer not only to the lack of technical expertise but also to limited public understanding of the benefits of GI; ii) governance challenges, including institutional inertia, sectoral silos, and insufficient policy coordination; iii) socio-environmental justice and social cohesion, which underline the risk that green interventions may inadvertently reinforce existing inequalities or trigger processes of green gentrification [

27]. Additional barriers can also be identified, such as financial constraints [

28,

29].

These challenges reveal that the implementation of UGI and NbS is not merely a technical issue but a complex socio-political process. It requires addressing institutional, social, and technical dimensions through inclusive governance, transparent valuation practices, and long-term policy commitment. This study primarily focuses on how various critical issues can be addressed by experimenting with new forms of citizen engagement. Rethinking the role of citizens requires action on multiple levels: promoting greater and more widespread awareness, ensuring the equitable distribution and accessibility of green spaces and their associated ecosystem benefits, and updating governance models to include new forms of public-private collaboration.

1.2. Advancing UGI Through Citizen Engagement

In light of the challenges highlighted in the literature, increased citizen involvement—going beyond traditional forms of participation—can represent a strategic approach to support the advancement of UGI [

30]. Beyond fostering widespread awareness of the benefits of nature in urban environments through educational and communication initiatives, citizen support and their perceptions of risks and benefits are crucial in underpinning innovative policies and forward-looking planning decisions.

Since the 1970s, a gradual cultural transformation has led an increasing number of people—even beyond experts and scholars—to develop a deeper awareness of the value of natural ecosystems and the importance of reintegrating and protecting nature in urban environments. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic acted as a disruptive event in this ongoing process of change, profoundly impacting habits and perceptions [

31,

32,

33]. During lockdown periods, the ability to physically or visually access urban green spaces was rediscovered as a valuable asset and a source of well-being. [

34,

35]

On the other hand, urban planning approaches have, for years, increasingly sought to include citizens through participatory processes and public consultations [

36]. Today, new scenarios for citizen participation and active inclusion can be explored, drawing on both the progress of research and a collective mindset that is increasingly open to and engaged with issues related to urban green spaces. At the European level, there are still relatively few cities actively experimenting with effective and systematic methods for involving both public and private actors in the multi-scalar planning processes of UGI. Among the most noteworthy examples are: Barcelona, which, in response to the consequences of intense urbanization and climate change, has developed a detailed strategy to reclaim every vacant urban space as public green space, including the mapping of courtyard interiors and private areas [

37,

38,

39,

40]; Hamburg, whose Open Space Requirement Analysis (2012) classified all building typologies in the city and identified the potential for integrating new urban greenery in proximity to residential functions [

41,

42,

43]; and Edinburgh, which since 2009 has developed an Open Space Strategy aimed at improving the quality and accessibility of existing green spaces, minimizing their loss to urban development, and ensuring adequate open space provision in new developments [

44]. Above all, the example of Rotterdam proved to be of particular interest for this study.

The city of Rotterdam is experimenting a strategy combining ‘densification’ –to achieve a mix of uses and functions– and ‘greenification’ –to compensate for previously unmet or future demand of urban green provision [

45,

46]. Since the 1970s and more intensively in the last 20 years, the redevelopment of the central area focused on reintroducing the residential function, promoting mixed-used and vertical growth. [

47] This process went hand in hand with a constant attention on the public space (the so-called 'groundscraper' strategy). Additionally, Rotterdam has been facing sea-level rise, higher rainfall, increasing heat waves and flooding, which pushed the city to adopt pioneer initiatives for urban adaptation, including GI as a key part of the urban program [

46]. Citizen engagement and the inclusion of private actors was highly enhanced. Indeed, the scarcity of public transformable space – only 40 % of Rotterdam area is public land– and the objective of balancing densification and accessible green spaces made it necessary to include private open spaces in each spatial planning action. So cooperation with private entities and residents is essential [

47]. Many of the foreseen greening interventions apply to private areas and properties, such as green roofs and walls. Additionally, private initiatives are encouraged and supported both directly, through public financing of private actions (e.g. the Climate Adaptation Grant adopted in 2012) and indirectly, by deregulating certain initiatives and reducing bureaucratic restrictions.

1.3. Case Study and Research Framework

This study focused on the case of the city of Milan. This city combines the challenges of a large urban area with high population density, the risks associated with a territory increasingly affected by environmental issues and CC (impacting on air quality, water management issues, and heat peaks), and the potential of a dynamic metropolis long engaged in ecological transition and the modernization of its governance structures [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. Since 2019, the city has updated its internal organization by establishing the Directorate for Environmental Transition. Additionally, the

Territorial Governance Plan Milano 2030 (PGT Milano 2030), adopted in 2020 and currently under review, outlined a roadmap to strengthen the municipal ecological network through the urban green and blue infrastructure approach and emphasized participatory processes and the inclusion of citizens in strategic decision-making [

53]. Due to these characteristics, the city offers a particularly relevant context for investigating citizens’ perceptions and exploring opportunities to engage them more actively in the implementation of UGI—moving beyond purely consultative roles toward genuine citizen empowerment.

The study and the findings presented in this paper are primarily focused on the social dimension, active participation, and the potential role of private actors in the implementation of UGI in the case of Milan. It was preceded by previous explorations that had already highlighted the spatial and strategic relevance of private open spaces in Milan, both for preserving existing green areas and for planning new ones. Previously published research on the spatial character of Milan green system [

54], highlighted the presence of a relevant amount of privately-owned small-sized green spaces. In the central district of the city private open spaces mainly consist of courtyards inside the urban blocks and cover an area of 1.6 km

2, which corresponds to 19% of the entire area of the historic center [

55]. The study area specifically focuses on Municipio 1, the historic center of the city, which is characterized by high density and a historically layered urban fabric where the complementarity between public and private open spaces is particularly evident (

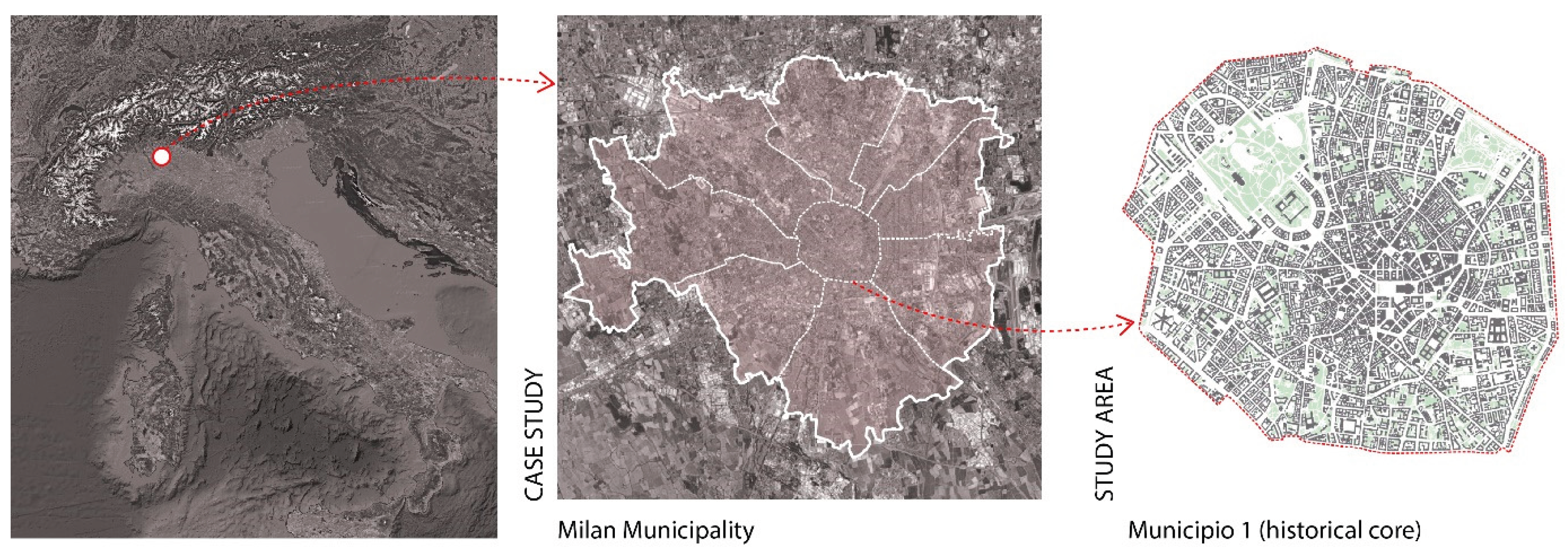

Figure 1).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Scope of the Research

Researchers and practitioners are increasingly aware of the pivotal role that citizen engagement plays in the processes of renaturing cities. Citizens are now widely recognised as key stakeholders, possessing valuable local knowledge and a strong sense of attachment to their neighbourhoods [

56]. This study aims to explore new approaches to citizen engagement and empowerment in the development of UGIs. In particular, it investigates the potential role of private citizens in transforming their own private open spaces, in line with the principles of UGI and NbS. When proposing such transformations, it is crucial to understand current citizen attitudes, perceived priorities and needs, and to raise awareness of the importance of private spaces in both preserving urban green heritage and contributing to future UGI networks [

57,

58,

59].

This research seeks to address the following questions, investigated in the case study of Milan:

What are the perceived priorities regarding urban adaptation to climate change and the role of private spaces?

What are the perceived risks associated with the implementation of NbS in private open spaces?

To what extent are citizens interested in playing an active role?

These research questions were investigated through a social inquiry targeting both a group of experts and a broader general audience. The findings informed the development of a design toolkit for NbS implementation in private open spaces within the Milan case study. This toolkit aims to align local citizens’ priorities and preferences with climate adaptation needs and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

This study was conducted within the framework of the EU-funded YADES project, which focused on the adaptation of historic urban areas to climate change and concluded in March 2025. As part of the project, the author carried out research on the integration of UGI in historic and dense urban contexts, which also included the social investigation presented in this article. The project provided a relevant network for engaging experts in the discussion and collecting their feedback.

2.2 Methodology

The study was performed with two different approaches, each one responding to a specific goal:

focus groups were conducted within a selected community in early stages of the research in order to explore awareness and expectation of experts/interested audience towards the research topic;

questionnaires were distributed to a wide audience in the study area of Municipio 1 to record preferences and concerns about alternative solutions.

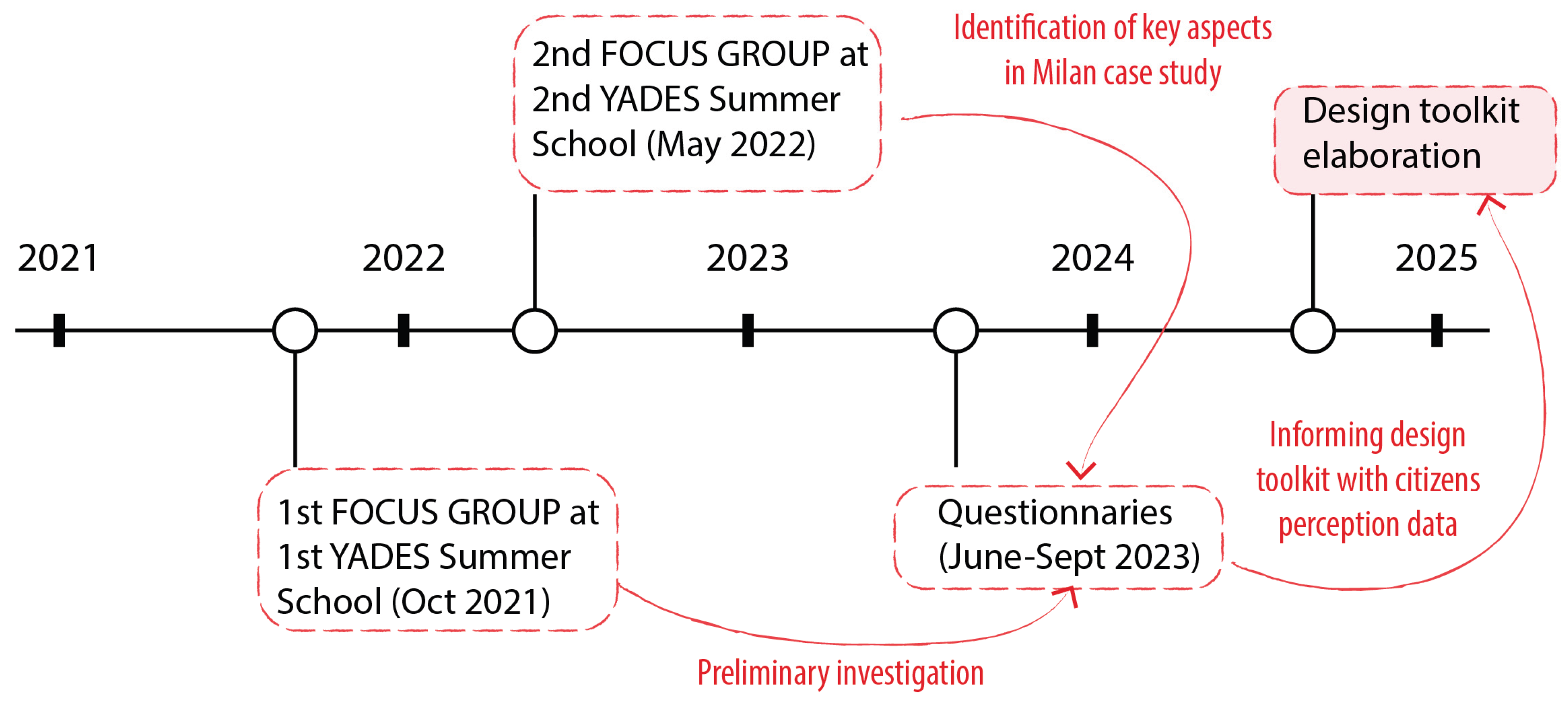

Last, the results emerging from the questionnaires were integrated into a design toolkit for including NbS in private open spaces. The various steps of the study are outlined in

Figure 2.

2.2.1 Focus Groups

The focus groups were conducted as part of the annual Summer Schools of the YADES project, in 2021 and 2022. The first Summer School, due to pandemic-related reasons, was an online event limited to project participants. The focus groups were interviewer-administrated, meaning that the collection of answers and feedbacks happened in a face-to-face situation where it was possible to make additional questions and have a discussion about the raised topics. The audience involved in the focus group consisted of individuals specialized in urban risk management, with experience in urban resilience and adaptation strategies, although not necessarily experts in green solutions. Additionally, most participants were not specifically familiar with the Milan case study. Therefore, the survey referred to historic centres and dense urban areas in a broader way.

Differently, the second Summer School took place in person in Milan and was an open event. The audience that participated consisted of interested individuals with a scientific background and a moderately high sensitivity to environmental issues. In this case, the investigation focused more on the daily experience of greenery in the case of Milan and included a specific focus on private open spaces in this city. The detailed structure of the focus groups is reported in

Appendix A.

2.2.2. Questionnaires

While the focus groups were targeted at an expert or interested audience, the questionnaires were aimed at investigating the general perception of the population of Milan, particularly in Municipio 1. The questionnaire was self-administrated, avoiding respondents to be subject to interviewer effect, and cross-sectional, aiming to explore population’s attitude towards the current state of the UGI in Milan’s historic centre and possible future scenarios [

60].

The questionnaire has been structured into three sections: 1) Courtyards of Milan; 2) Transformation scenarios; 3) General information. The detailed structure is reported in

Appendix B. The first part aims to gather objective and subjective information about the current situation of private open spaces. Objective information includes courtyard accessibility, current functions, the presence and integration of vegetation. Subjective information, on the other hand, refers to respondents' evaluations of the adequacy of the current situation, along with some insights into the modes and frequency of private outdoor space utilization. The second section introduces the reference to future transformation scenarios for which respondents are asked to provide feedback regarding possible interventions to be implemented, priorities to be followed, and potential issues. It also investigates respondents' inclination towards their direct engagement and the opening up of private spaces. Last, the third section collects some basic information about the respondents while ensuring anonymity and privacy, in order to verify the composition of the sample

2.2.3. Design Toolkit

The final step of the study involves the development of a design toolkit to integrate NbS into private open spaces. This tool draws inspiration from several existing catalogues, although originally created for different purposes. The primary references for this toolkit include previous collections and classifications of urban NbS, particularly those conducted by the World Bank [

61] and by LabSimUrb at Politecnico di Milano [

62]. These catalogues aim to provide a comprehensive classification of NbS across different scales, from the landscape scale to that of individual buildings. For the purposes of this study, a careful selection was made to extract only those actions applicable at the urban scale and suitable for small- to medium-sized spaces, such as the private residential open spaces found in the Milan case study. A more specific operational reference is provided by real urban experiences, such as those in Rotterdam [

63] and initiatives from various American cities focused on distributed stormwater management [

64,

65,

66]. These examples were instrumental in identifying private actors as active agents in the development of the UGI.

3. Results

3.1. Analytic Results of Social Investigation

3.1.1. Focus Groups

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the two focus groups pursued distinct objectives, reflecting the different profiles of the participants involved. In brief, the first focus group confirmed that the limited pervasiveness and distribution of green spaces in historic and high-density urban contexts is a widespread issue, thereby highlighting the broader relevance of this study. In contrast, the second focus group contributed to a deeper understanding of the Milan case study and subsequently informed the development of the questionnaire. Participation data are reported in

Table 1. The analytical data from the responses are provided as supplementary materials.

The first focus group included 38 international participants with proven expertise in urban resilience. This session served as a preliminary exploration of the value of integrating green features in historic and high-density urban contexts as a strategy for climate adaptation. In particular, the discussion focused on identifying the most effective approaches to promote this integration, as perceived by the participants, as well as the main barriers that hinder its implementation. From the starting general questions about the relationship between the historic/dense urban areas and the availability of urban green spaces, it emerged that, even when considering cities other than Milan, the lack of greenery is a widespread issue. 31% of respondents reported a severe lack of greenery, and 63% reported a low presence. However, when asked about the distribution of green spaces between public and private areas, the responses contradicted the data from the Milan case. Indeed, 88% of the respondents believe that the existing greenery is predominantly public. It can be hypothesized that this perception is influenced by the accessibility of green spaces. Still, this response highlights a lack of awareness of the role of private green spaces, which, while not directly accessible to everyone, provide a collective service in terms of ecosystem benefits. Regarding the perceived barriers to more effective integration of green infrastructure in historic contexts, respondents assigned significant importance to the scarcity of transformable public space (28%) and the inadequacy of existing planning tools (31%). Finally, when asked about the relevance of certain proposed actions to support the integration of green infrastructure in historic areas, the four alternatives received very similar scores. However, respondents attributed slightly greater importance to coordinating private initiatives with public ones and differentiating green solutions.

The second focus group collected feedback from 62 participants, mostly based in Milan or at least familiar with the case study. The starting questions revolved around the perception of nature's role in the daily experiences of the urban space. 82% of the respondents claimed to have daily contact with nature, mainly in the form of visual or passing-through contact (e.g., passing through a park or walking along a tree-lined avenue during their daily commute). Activities involving stationary interaction with nature (such as spending time in the park to relax, exercise, or socialize) are less common. Respondents unanimously emphasized the fundamental importance of daily contact with nature, particularly highlighting its impact on mood improvement and stress reduction. Moving on to specific questions about private courtyard spaces, over half of the respondents reported not having any vegetation (26%) or having only potted plants (29%) in their courtyards, while 45% had ground-integrated vegetation. In the context of future transformation of these spaces, respondents attached greater importance to the "structural" incorporation of vegetation through tree planting and interventions to restore soil permeability. This was followed in perceived importance by the inclusion of furnishings for space utilization, while the inclusion of playground equipment for children was not strongly supported. Lastly, regarding barriers to implementing courtyard renaturation projects, respondents expressed more concern about increased maintenance costs, followed by the inconveniences caused by transformation work. Concerns about the loss of parking spaces were relatively mild, and the issue of insects due to increased vegetation presence ranked much lower.

3.1.2. Questionnaires

Taking advantage of the relevant insights provided by the focus groups, a broader social investigation was carried out to investigate the general perception and attitude of Milan citizens towards including private open spaces in the municipal UGI strategy. The target of the questionnaire was specifically the population of Municipio 1, consistsing of 111.560 people [

67]. Setting a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%, the sample size was set at 383 respondents. The questionnaire distribution took place between June and September 2023. After closing the questionnaire distribution, a total number of 394 answers was recorded. Out of the total, 39 respondents declared not to have a courtyard or a garden in their dwellings and consequently didn’t fill section 2. Thus, the number of useful answers was limited to the 355 of those who declared to have a courtyard and entirely filled the questionnaire. This still guaranteed a margin of error limited to 5,19% (see

Table 2). The sample has a balanced gender distribution, with 51% of female respondents and 47% male. Regarding the age distribution, there is an imbalance towards the younger age groups, especially the 26-35 age range, and inadequate representation of the over 65 age group. This is certainly attributable to the online administration mode of the questionnaire.

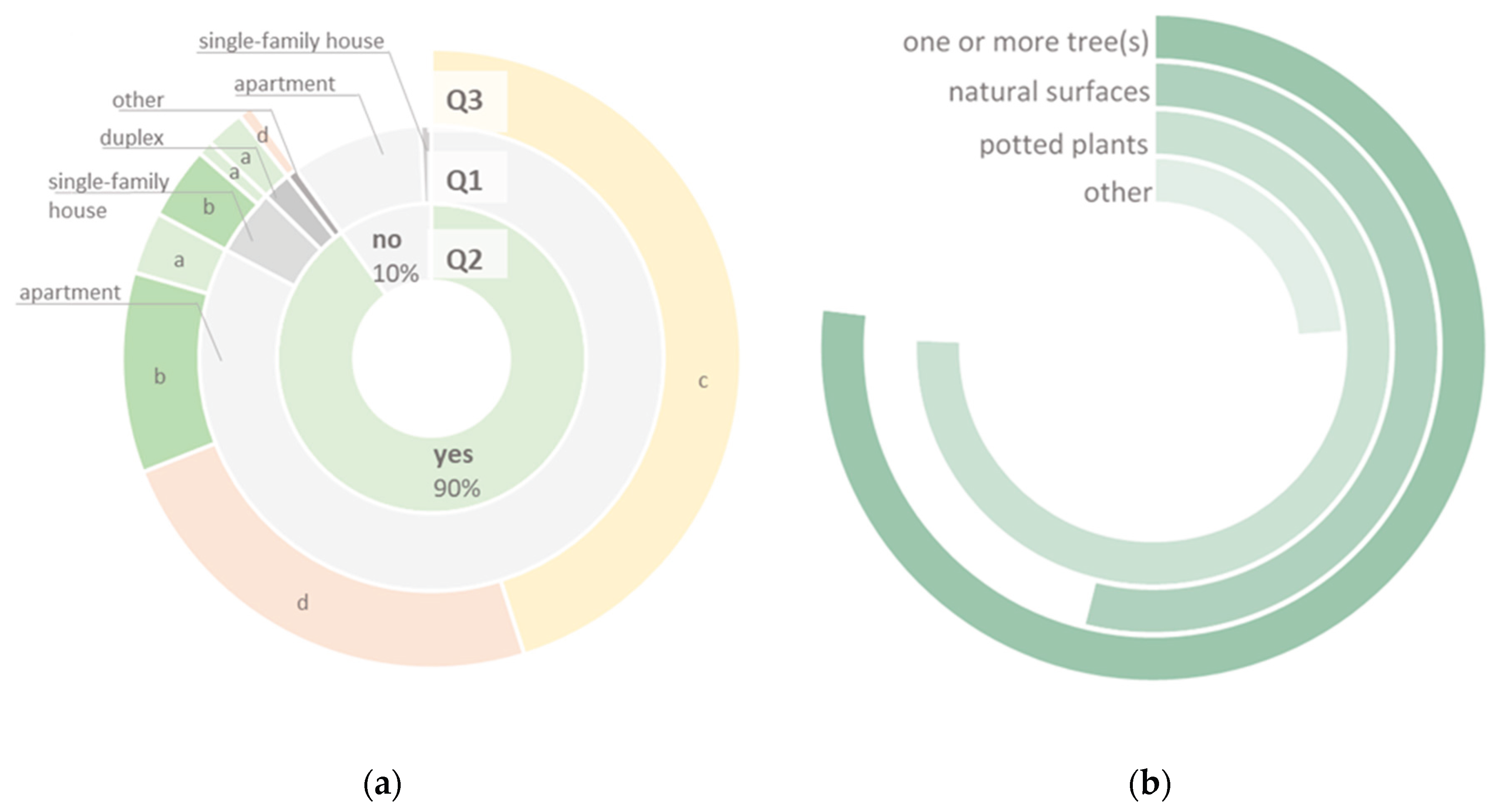

As shown in

Figure 3a, 90% of participants claim to have a courtyard/garden/space related to their residence. The vast majority of them live in apartments within residential buildings (92%), while a smaller number have different housing solutions. Regarding the private open space location, internal courtyards resulted the most common type (84%), raising potential challenges in evaluating the visual and physical accessibility of private greenery [

68]. Regarding the presence of vegetation of any kind (

Figure 3b), 85% of the responses are positive. Ou of the 303 positive answers, 26% reported to have only potted plants, and a significant 60% at least one tree. Natural surfaces, such as flowerbeds or grassy areas, are less common.

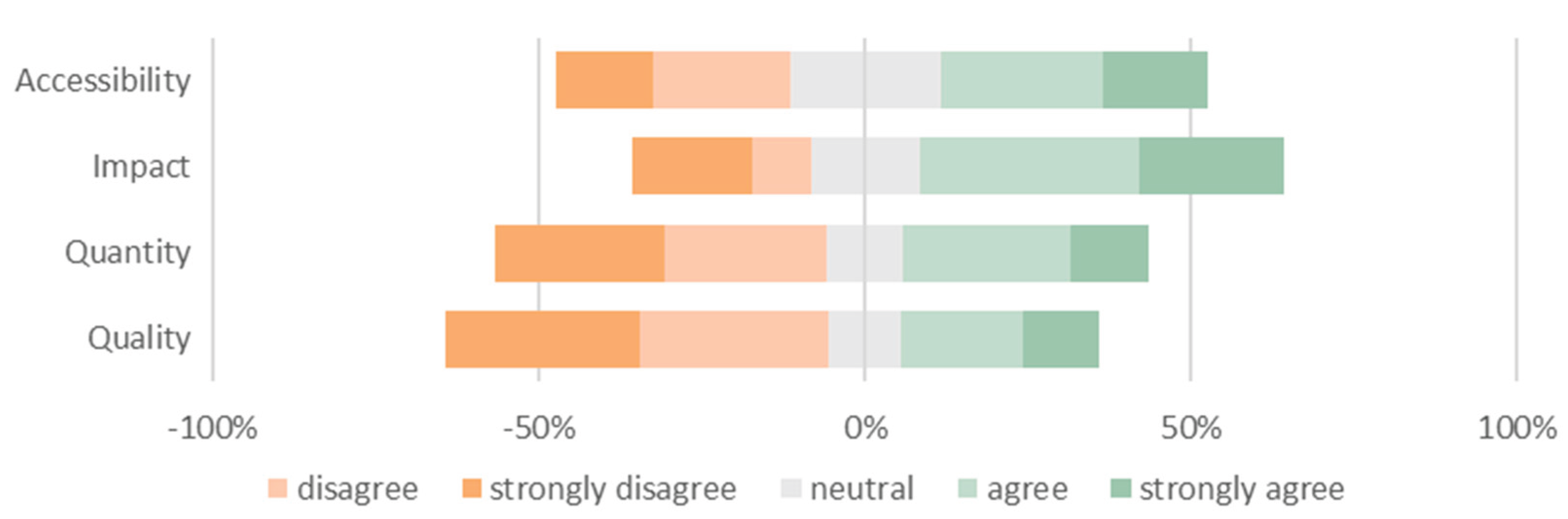

Regardless of whether there is vegetation at present, the significance of greenery in private open spaces is unanimously acknowledged, with an average score of 4.7 out of 5. Finally, respondents were asked to evaluate the greenery currently present in their courtyards with respect to quantity, quality, impact, and accessibility. Question Q10 records peaks of dissatisfaction, especially regarding quantity and quality, thus opening the possibility of taking greater and better actions for the integration of greenery in private spaces (

Figure 4).

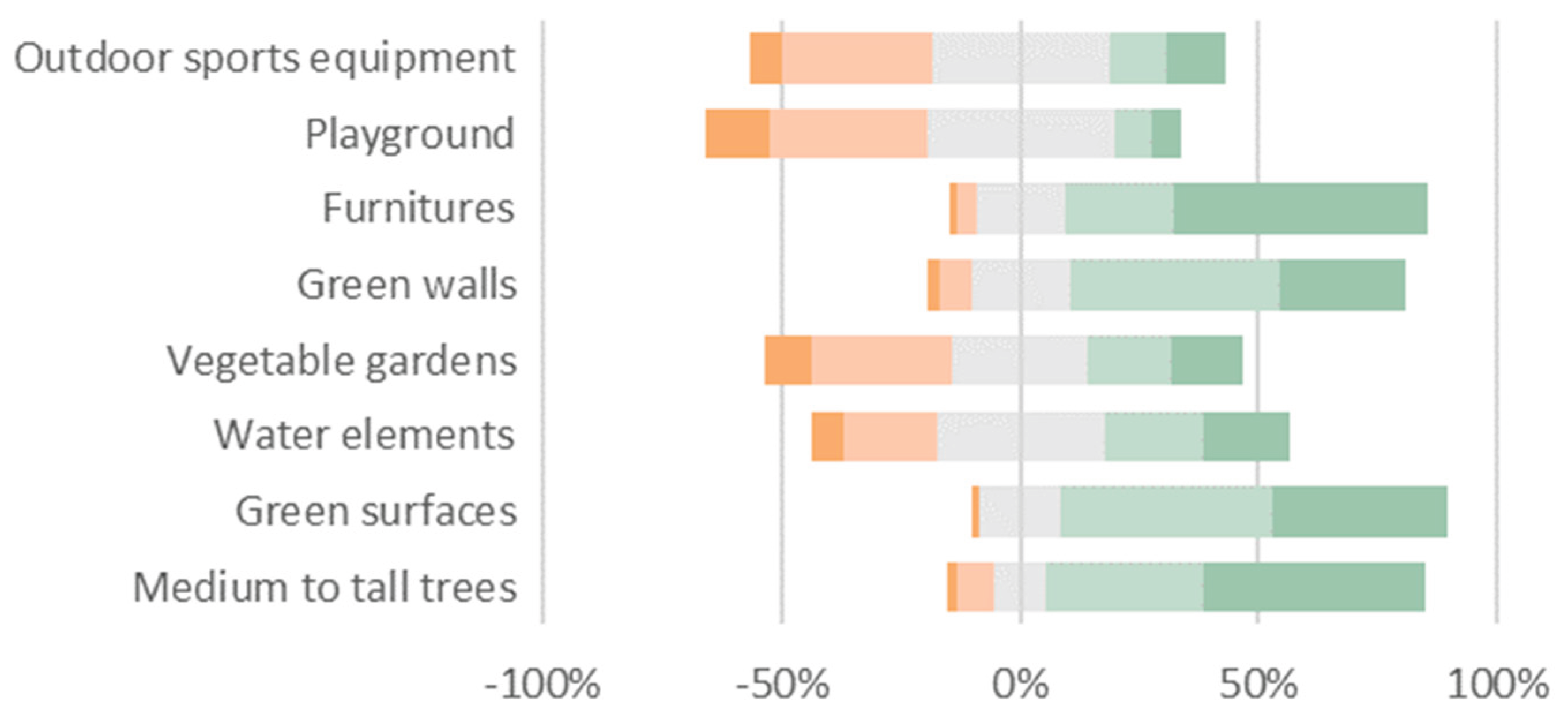

The most relevant results obtained from the questionnaire are those concerning future transformations scenarios, included in

Section 2. In particular questions Q11, Q12 and Q13 investigated the preferences, priorities and concerns about greening private courtyards. The questionnaire results highlight a strong preference for ‘structural’ greening interventions, such as green walls and surfaces which are able to deeply change the perception and functionality of the space (

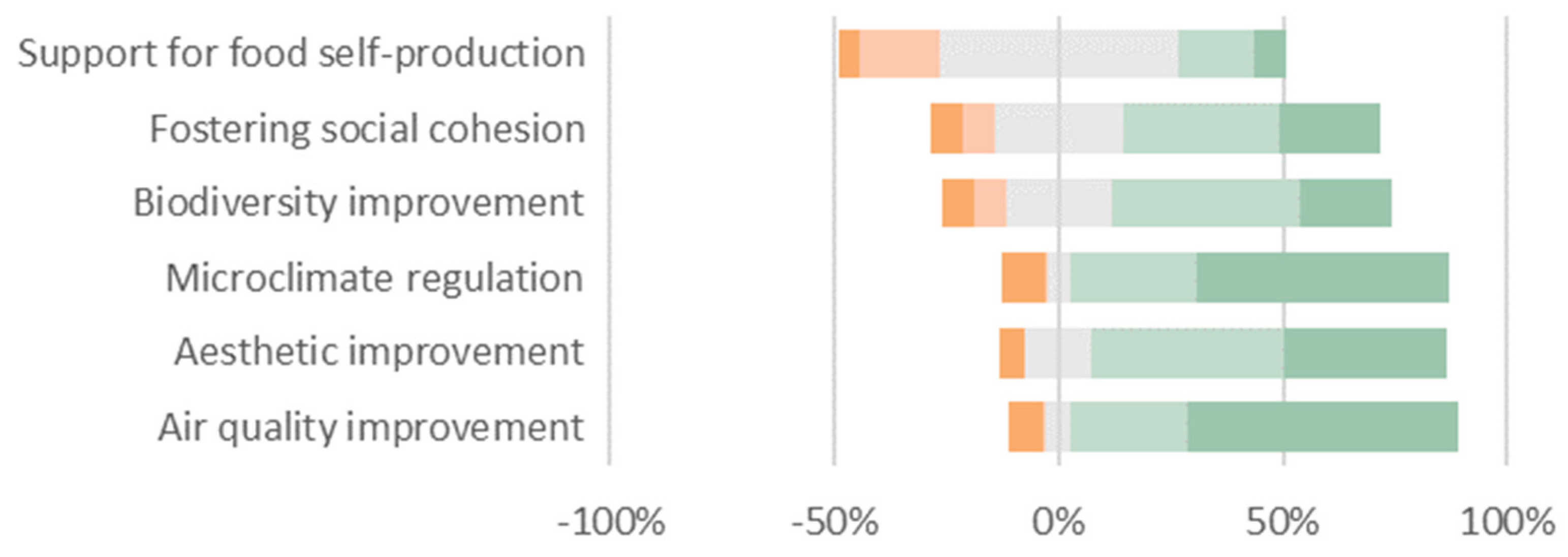

Figure 5). To that point, respondents’ preference is aligned with the opinion expressed within the focus group and definitely with the direction of transformation highlighted by the analysis conducted so far. The preferences expressed are also consistent with the assignment of priority to air quality improvement and microclimate mitigation, which are actually severe problems in Milan directly affecting people (

Figure 6).

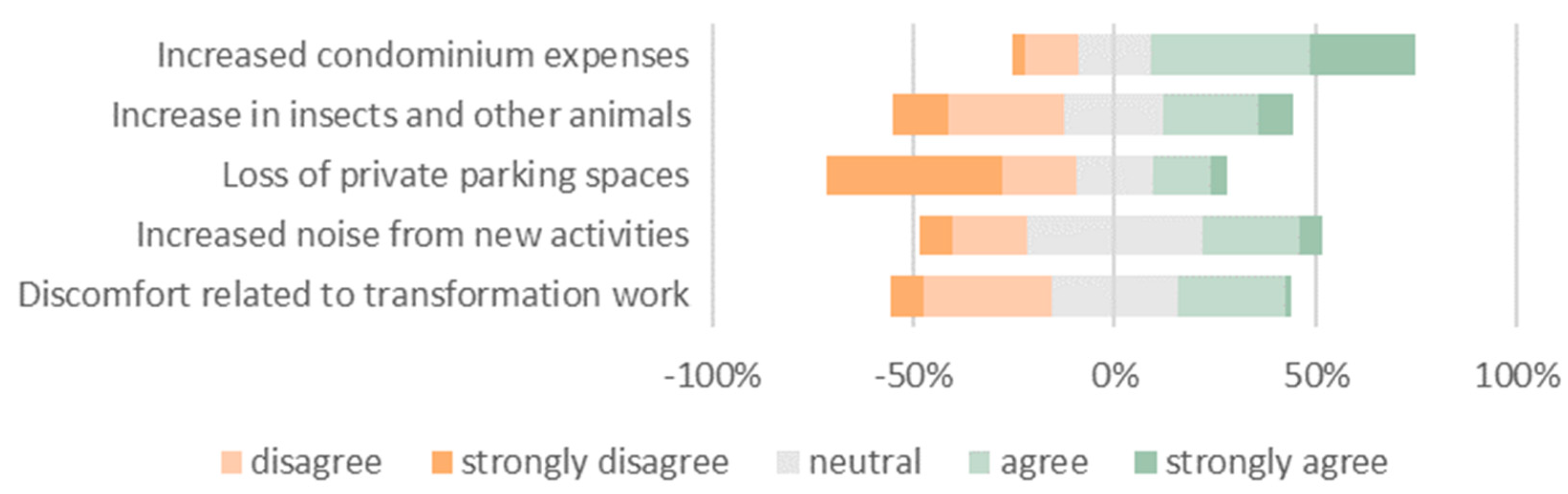

Among the concerns, the increase in costs of maintenance ranks first, as in the focus groups, stressing again the need to continue working on low-maintenance solutions and circular processes on the research front and to strengthen awareness-raising activities about the long-term sustainability of green interventions on the educational front (

Figure 7).

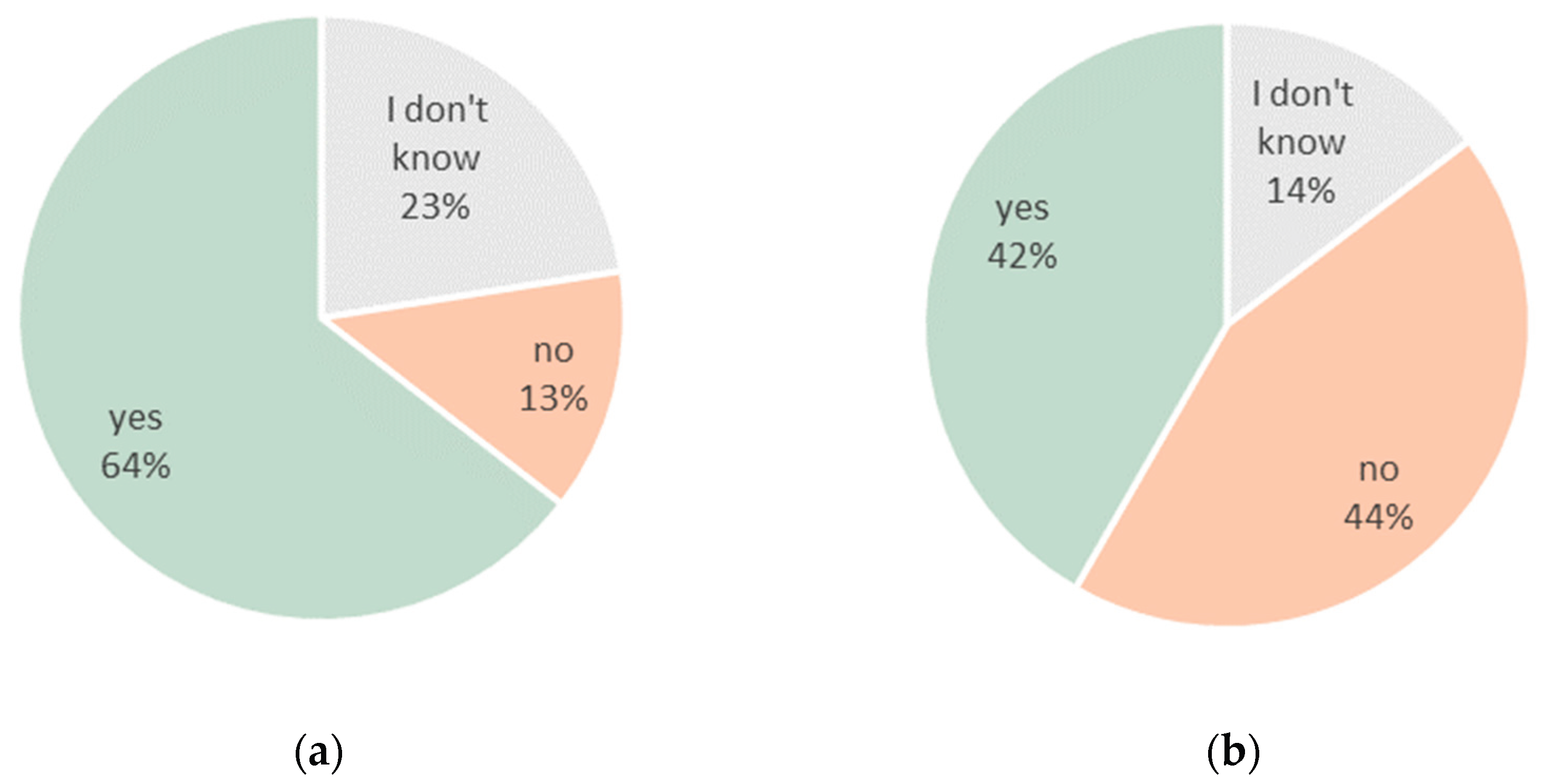

About people’s attitude on their direct engagement, positive feedback was registered on participating in greening activities, even if with a high rate of undecided respondents (

Figure 8a), while there is a much more negative attitude towards the regulated opening of private courtyards to non-resident people (

Figure 8b).

3.2. Integrating Citizens’perspective into a Design Toolkit

The results obtained from the questionnaire suggest the need to base a viable strategy for the inclusion of private space in the UGI program on participatory processes and public consultations, in order to involve citizens in the definition of effective ways and tools for the sustainable management of private open space. The final step of this study reinterpreted the input provided by citizens and proposed a toolkit to integrate NBS into private open spaces. This tool supports citizen empowerment by making them aware of the practical actions they can implement within the spaces under their control. The overarching logic remains that of the UGI, as each individual action not only brings local benefits but also contributes to the broader ecological network at the municipal level.

The proposed toolkit is a catalogue of possible actions selected for their compatibility with the focus on residential private spaces. The chosen solutions can be implemented by individual citizens owning an undeveloped area, by a group of citizens (such as residents in the same building deciding to act on the common courtyard), or even by municipal decision-makers to develop coordinated programs for intervention in private spaces.

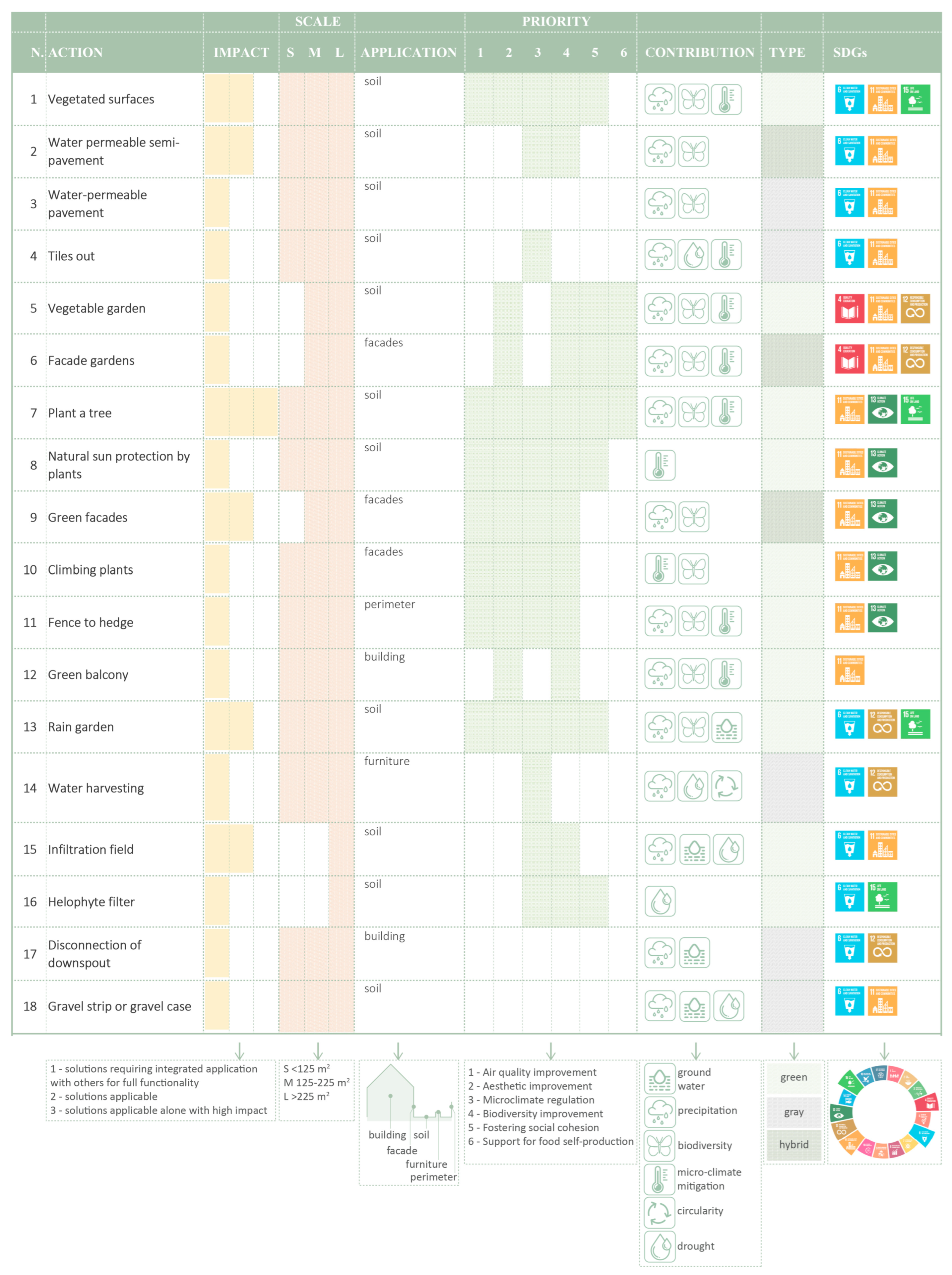

The proposed classification introduces various parameters to support informed choices, including:

the scale of application, classified into 3 classes defined on the quantiles of the size distribution of private open spaces within the study area: S <125 m2; M 125-225 m2; L >225 m2;

the impact on a scale from 1 to 3: 1) solutions requiring integrated application with others for full functionality; 2) solutions applicable individually; 3) solutions individually applicable with high impact;

the mode of application with respect to the courtyard space, i.e., whether it involves interventions on the ground, on the surrounding facades, on the building, or the incorporation of a furniture/technological element;

the perceived priority to which the solution responds, referring to the 5 options recorded through the questionnaires (see

Figure 6): 1) Air quality improvement; 2) Aesthetic improvement; 3) Microclimate regulation; 4) Biodiversity improvement; 5) Fostering social cohesion; 6) Support for food self-production;

the contribution in terms of adaptation to CC: 1) contribution to ground water infiltration; 2) contribution to rainwater management; 3) enhancement of biodiversity; 4) mitigation of micro-climate; 5) contribution to circularity; 6) contrast to drought;

-

the type of solution distinguished between green, gray or hybrid;

the contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Figure 9 shows the resulting toolkit, with 18 NBSs applicable in private open spaces and the corresponding data.

4. Discussion

The investigation conducted in the Milan case study enabled the exploration of both the potential and limitations in proposing new forms of active citizen involvement in the development of UGI. The results that emerged from the focus groups—particularly the second one—highlighted the importance of gaining a deeper understanding of local risk perceptions and community preferences in order to guide locally appropriate strategies and engagement models. Additionally, the questionnaire findings offered an insightful snapshot of Milanese citizens’ attitudes toward integrating NbS into private open spaces, as well as their preferences regarding forms of active participation. Milanese residents have long been accustomed to being involved in urban decision-making, at least in consultive ways, and are generally receptive to more proactive forms of civic engagement. However, what was more unexpected was the general reluctance toward regulated forms of opening up private open spaces for broader community use. Similar initiatives—such as opening schoolyards outside school hours for collective activities—have already been piloted in Milan [

69], as well as in other cities [

70,

71,

72]. Nevertheless, extending this model to residential private open spaces has not, at present, met with widespread public approval, possibly due to concerns about noise and safety.

The active involvement of citizens in incorporating the strategies and principles of NbS into the spaces under their stewardship opens up promising avenues for the development of the UGI. It allows for the envisioning of a complementary system of small green spaces that, collectively, can make a significant contribution to the urban ecosyste. This strategic direction aligns with the core principles of UGI by reinforcing multi-scalar implementation—particularly at the micro scale—enhancing social inclusion and the engagement of diverse stakeholders, and promoting the integration of green and grey components into cohesive and scalable solutions.

The opportunity to more systematically include private open spaces and to empower citizens represents a promising direction for a city like Milan, which is actively engaged in climate change adaptation. The city has already seized several collateral opportunities to strengthen its ecological network and promote the development of urban green areas — from the construction of new metro lines that led to the creation of linear parks on the surface, to the reuse of disused railway yards as new public parks [

73,

74]. However, in order to truly achieve the goals of green space accessibility and distribution, it is essential to experiment with innovative approaches. In this context, new models of public-private collaboration represent an opportunity that should not be overlooked [

75,

76].

As for the limitations of this study, it is important to highlight that the questionnaire targeted residents of Municipality 1. Other studies have shown that citizens’ willingness to participate in the implementation of UGI tends to be higher in inner-city areas than in peripheral ones [

77]. This may be due to the relative lack of green space in central neighborhoods, to demographic characteristics, or to other contextual factors. Therefore, the results of this study can be more extended to other dense urban centers in European cities, rather than to suburban or peri-urban areas where the urban fabric, green space configuration, and social composition differ significantly.

Finally, the developed toolkit comprises a critically selected set of NbS applicable in private open spaces, aimed at enhancing citizens' agency and positioning them as active contributors to the realization of UGI. However, for this contribution to be fully integrated within a systemic green infrastructure approach, a stronger public-private collaboration is needed, as in the successful case of Rotterdam [

47,

78,

79,

80]. This should include:

greater recognition by public authorities of the strategic role of private open spaces and of active citizenship;

administrative and financial tools to facilitate and support private initiatives;

technical assistance and monitoring tools to ensure that private interventions are carried out properly;

ultimately, a long-term strategy in which public and private actions are planned in a complementary manner to achieve clearly defined urban adaptation goals.

5. Conclusions

This study aims to contribute to the ongoing research effort aimed at understanding how NbS can be more systematically integrated into the urban environment. The topic of private open spaces and citizen empowerment emerges as an area of significant interest and potential, warranting further investigation. Several related aspects still require in-depth exploration, including governance models and effective forms of public-private partnerships, methods and tools for systematic monitoring, and assessments of the potential impact and cost–benefit analysis of a widespread transformation of private open spaces as integral components of the UGI.

Funding

This research was funded by the Marie Skłodowska-Curie YADES project, grant agreement No 872931.

Data Availability Statement

The focus group data presented in the study are openly available at the following links reported in Supplementary Materials. The questionnaire data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study was developed as part of my doctoral research within the YADES project. I would like to thank all the project partners who participated in the summer schools, bringing their diverse disciplinary perspectives and backgrounds, and contributing to a rich and stimulating debate on green infrastructure. Special thanks are also due to all the individuals who took the time to complete the questionnaire, to the CAM of Milan for supporting the questionnaire’s distribution via email, and to Professor Nerantzia Tzortzi, who guided and supported my research journey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CC |

Climate Change |

| ES |

Ecosystem Services |

| EU |

European Union |

| GI |

Green Infrastructures |

| NBS |

Nature Based Solutions |

| PGT |

Piano di Governo del Territorio (Territorial Government Plan) |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| UGI |

Urban Green Infrastructures |

Appendix A

This appendix includes the structure of the two focus groups held within YADES Summer Schools (

Table A1 and

Table A2). The interactive questionnaires were presented with Aha Slides, which allowed the participants to join the activity with their smartphones to provide answers and also expand the discussion through direct interaction.

Table A1.

Interactive questionnaire in the 1st focus group

Table A1.

Interactive questionnaire in the 1st focus group

| QUESTION |

TYPE |

ANSWER OPTIONS |

| 1 - which city are you from? |

open ended |

|

| 2 - Which urban Cultural Heritage layout best describes your city? |

multiple choices |

ISOLATED BUILDINGS - There is not a defined historical centre, some historical building are present within the urban environment. |

| HISTORICAL CENTRE - The historical centre is clearly defined and presents homogeneous characters. |

| HISTORICAL DISTRICTS - Several different areas of historical interest are present within the urban environment |

| 3 - How would you rate the integration of the Urban Green Infrastructure in the Historical urban area(s)? |

multiple choices |

in the historical urban area(s) there is a sever lack of green spaces and connections |

| only few green spaces and green connections are present in the historical area(s) |

| the urban GI fully involves also the historical area(s) |

| 4 - The existing green spaces in the historical area(s) are mostly... |

multiple choices |

public green spaces |

| private green spaces |

| I don't know |

| 5 - Referring to the strategic plans of your city, a further development of the existing UGI in historical areas is planned? |

multiple choices |

yes |

| no |

| I don't know |

| In your opinion, which are the main constraints to integrating GI into the historic areas of your city? |

multiple choices |

lack of public open space |

| lack of a strategic plan |

| lack of green solutions adapted to the historical context |

| extreme fragility of the historical context |

| lack of incentive policies for private initiative |

How would you rate these action for the effective integration of the GI strategy into historical urban areas? [1: not important / 5: very important]

|

scale |

knowledge of the green history of the area |

| coordination of private initiatives with the objectives identified by strategic planning |

| differentiation of the UGI according to the characteristics of the context (including historical, cultural, architectural...) |

| development of financial instruments to promote private initiative (for the integration of private spaces in the UGI) |

| Can you think of other actions to promote the integration of GI in historical districts? |

open ended |

|

Table A2.

Interactive questionnaire in the 2nd focus group

Table A2.

Interactive questionnaire in the 2nd focus group

| QUESTION |

TYPE |

ANSWER OPTIONS |

| Do you live in Milano? |

binomial |

yes |

| no |

| If NO, where do you currently live? |

open ended |

|

| Do you have a daily contact with nature? |

binomial |

yes |

| no |

| If YES, which of these modalities are part of your daily contact with Nature? |

multiple choices |

looking |

| passing through |

| staying |

| practicing |

How do you rate the importance of Nature in your daily life?

[1: I don't agree / 5: I agree] |

scale |

It helps me to relax and calm |

| It improve my mood |

| It improve my productivity and concentration |

| It allow me to do practical activities |

| Referring to the courtyard/private space of the house you live in, is there any kind of vegetation? |

multiple choices |

no, not at all |

| yes, but only vegetation in pots |

| yes, only/also vegetation in the soil |

Which actions are more relevant in your opinion?

[1: not important / 5: very important] |

scale |

trees and high vegetation to shadow |

| improvement of soil permeability and ground vegetation |

| furnitures to allow people to stay (benches, tables...) |

| playground for children |

Considering to transform private courtyards in green spaces, which of these limitations are more relevant in your opinion?

[1: not important / 5: very important] |

scale |

parking removal |

| noise and/or dust for the transformation works (even if limited in time) |

| vegetation brings more insects and other animals |

| costs of maintenance |

| Thinking about the courtyard/private space of your house, what you would like to change? |

open ended |

|

| |

Appendix B

Appendix B includes the content of the questionnaire delivered to the citizens of Milan (

Table B3). The questionnaire was delivered online on Microsoft form, in compliance with the security and privacy standards of Politecnico di Milano. The distribution took place through the network of contacts registered in the neighbourhood Multifunctional Community Centres (Centri di Aggregazione Multifunzionali - CAM) for Municipio 1.

Table B3.

Questionnaire structure.

Table B3.

Questionnaire structure.

| SECTION 1/3 - COURTYARDS IN MILAN |

| Question |

Options |

| 1 - What type of housing do you live in? |

single-family house |

| duplex house |

| apartment in a residential building |

| other |

| 2 - Does your house have a courtyard/garden/open space (private or shared)? |

yes |

| no |

| 3 - Where is the courtyard/garden/open space place with respect to the building? |

in front of the building |

| around the building |

| within the block, accessible through a vehicle entrance |

| within the block, accessible through the building |

| 4 - What functions are present within your courtyard? |

car parking |

| bike parking |

| waste collection |

| benches, tables or other furniture |

| children playground |

| dehors or other extensions of private activities |

| 5 - How do you use the courtyard space? |

just passing through |

| to spend time outside |

| to meet other people |

| to park my car |

| other |

| 6 - How often do you use the space of the courtyard? |

Daily |

| Some times a week |

| Sporadically |

| Rarely or never |

7 - How much do you think the presence of greenery within an urban courtyard is important (regardless of whether your courtyard has it or not)?

[1: not important at all - 5: very important] |

|

| 8 - Is there any greenery in your courtyard? |

yes |

| no |

| 9 - What kind of greenery? |

potted plants |

| one or more trees |

| natural surfaces (flowerbeds, grass...) |

| other |

10 - How do you evaluate the presence of greenery within your yard?

[1: not satisfactory - 5: very satisfactory] |

quantity: the amount of greenery present is adequate for the space available |

| quality: the types of greenery present are appropriate for the space available (potted plants, flower beds, trees) |

| impact: the greenery present enhances the perception of the courtyard space |

| accessibility: the greenery present is easily and directly accessible |

| SECTION 2/3 - TRANSFORMATION SCENARIOS |

| 11 - Which of the interventions listed below would you like to carry out in your courtyard? |

Medium to tall trees for shading |

| Accessible and usable green surfaces (grass and flower beds) |

| Water elements for cooling (fountains, water ponds...) |

| Vegetable gardens |

| Green walls on the facades of buildings surrounding the courtyard |

| Furniture for the usability of the space (chairs, tables, benches...) |

| Children's playground |

| Outdoor sports equipment |

| 12 - Which of the following criteria do you consider a priority? |

Absorption of pollutants and improvement of air quality |

| Aesthetic improvement of the courtyard |

| Microclimate regulation ( mainly mitigation of heat peak |

| Enhancement of biodiversity |

| Fostering social interactions and strengthening a sense of community |

| Support for food self-production |

| 13 - Which of the aspects listed below do you think might be a problem for you? |

Discomfort related to courtyard transformation work (noise, dust), even if for a limited period of time |

| Increased noise from new activities in the courtyard (recreational activities, children's games...) |

| Loss of private parking spaces |

| Increase in insects and other animals due to the increased presence of vegetation |

| Increased condominium expenses for the maintenance and care of the common space |

| 14 - Would you be willing to participate in community initiatives aimed at greening urban courtyards (e.g., volunteering for gardening, maintenance, or planting activities)? |

yes |

| no |

| I don’t know |

| 15 - Would you support the regulated opening of your home's courtyard to people not domiciled in the surrounding buildings? (the use by outside users is limited to certain time slots) |

yes |

| no |

| I don’t know |

| SECTION 3/3 - GENERAL INFORMATION |

| 16 - In which district of Milan do you live? |

|

| 17 - In which neighbourhood? |

|

| 18 - What is your age? |

|

| 19 - What gender do you identify with? |

|

References

- Fang, X.; Li, J.; Ma, Q. Integrating Green Infrastructure, Ecosystem Services and Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Sustainability: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Sustain Cities Soc 2023, 98, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Collier, M.J.; Kendal, D.; Bulkeley, H.; Dumitru, A.; Walsh, C.; Noble, K.; van Wyk, E.; Ordóñez, C.; et al. Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Climate Change Adaptation: Linking Science, Policy, and Practice Communities for Evidence-Based Decision-Making. Bioscience 2019, 69, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramyar, R.; Zarghami, E. Green Infrastructure Contribution for Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Landscape Context. Appl Ecol Environ Res 2017, 15, 1193–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M.; Singer, R. Urban Resilience in Climate Change. In Climate Change as a Threat to Peace: Impacts on Cultural Heritage and Cultural Diversity; von Schorlemer, S., Maus, S., Eds.; Peter Lang AG: Dresden, 2014; pp. 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Geneletti, D.; Cortinovis, C.; Zardo, L.; Esmail, B.A. Planning for Ecosystem Services in Cities; Springer, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-20023-7. [Google Scholar]

- Thian, O.; Yeo, S.; Johari, M.; Yusof, M.; Maruthaveeran, S.; Zulhaidi, H.; Shafri, M.; Saito, K.; Yeo, L.B. ABC of Green Infrastructure Analysis and Planning: The Basic Ideas and Methodological Guidance Based on Landscape Ecological Principle. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges; Cohen-Shacham, E., Janzen, C., Maginnis, S., Walters, G., Eds.; IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, H.M.; Kala, J.; Ng, A.W.M.; Muthukumaran, S. Effectiveness of Vegetated Patches as Green Infrastructure in Mitigating Urban Heat Island Effects during a Heatwave Event in the City of Melbourne. Weather Clim Extrem 2019, 25, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, L.; Parisi, S.G.; Cola, G.; Lafortezza, R.; Colangelo, G.; Sanesi, G. Climatological Analysis of the Mitigating Effect of Vegetation on the Urban Heat Island of Milan, Italy. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 569–570, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petsinaris, F.; Baroni, L.; Georgi, B. Compendium of Nature-Based and “grey” Solutions to Address Climate-and Water-Related Problems in European Cities EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, L.; Liang, Y. The Impact of Tree Clusters on Air Circulation and Pollutant Diffusion-Urban Micro Scale Environmental Simulation Based on ENVI-Met. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, IOP Publishing, 1 February 2021; Vol. 657, p. 012008. [Google Scholar]

- Poortinga, W.; Bird, N.; Hallingberg, B.; Phillips, R.; Williams, D. The Role of Perceived Public and Private Green Space in Subjective Health and Wellbeing during and after the First Peak of the COVID-19 Outbreak. Landsc Urban Plan 2021, 211, 104092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, F.; Massetti, L.; Calaza-Martínez, P.; Cariñanos, P.; Dobbs, C.; Ostoic, S.K.; Marin, A.M.; Pearlmutter, D.; Saaroni, H.; Šaulienė, I.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Use and Perceptions of Urban Green Space: An International Exploratory Study. Urban For Urban Green 2020, 56, 126888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Nature-Based Solutions in Europe: Policy, Knowledge and Practice for Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; ISBN 978-92-9480-362-7. [Google Scholar]

- McPhearson, T.; Andersson, E.; Elmqvist, T.; Frantzeskaki, N. Resilience of and through Urban Ecosystem Services. Ecosyst Serv 2015, 12, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis.; Island Press: Washington, DC, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EU Guidance on Integrating Ecosystems and Their Services into Decision-Making, Brussels, 2019.

- European Commission. Towards an EU Research and Innovation Policy Agenda. Final Report of the Horizon 2020 Expert Group on ’Nature-Based Solutions and Re-Naturing Cities’: (Full Version) for Nature-Based Solutions & Re-Naturing Cities; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, C.; Hansen, R.; Rall, E.; Pauleit, S.; Lafortezza, R.; De Bellis, Y.; Santos, A.; Tosics, I. Green Infrastructure Planning and Implementation - The Status of European Green Space Planning and Implementation Based on an Analysis of Selected European City-Regions; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pauleit, S.; Hansen, R.; Rall, E.L.; Zölch, T.; Andersson, E.; Luz, A.C.; Szaraz, L.; Tosics, I.; Vierikko, K. Urban Landscapes and Green Infrastructure. Encyclopedia of Environmental Science 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Building a Green Infrastructure for Europe; Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal COM/2019/640 Final; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Green Infrastructure (GI) — Enhancing Europe’s Natural Capital /* COM/2013/0249 Final */; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, L.M.; Good, K.D.; Moretti, M.; Kremer, P.; Wadzuk, B.; Traver, R.; Smith, V. Towards the Intentional Multifunctionality of Urban Green Infrastructure: A Paradox of Choice? npj Urban Sustainability 2024, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.R.; Bledsoe, B.P.; Ferreira, S.; Nibbelink, N.P. Challenges to Realizing the Potential of Nature-Based Solutions. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 2020, 45, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; Bonn, A. Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas—Linkages Between Science, Policy and Practice. Theory and Practice of Urban Sustainability Transitions 2017, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toxopeus, H.; Polzin, F. Reviewing Financing Barriers and Strategies for Urban Nature-Based Solutions. J Environ Manage 2021, 289, 112371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüsken, L.M.; Slinger, J.H.; Vreugdenhil, H.S.I.; Altamirano, M.A. Money Talks. A Systems Perspective on Funding and Financing Barriers to Nature-Based Solutions. Nature-Based Solutions 2024, 6, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N. Seven Lessons for Planning Nature-Based Solutions in Cities. Environ Sci Policy 2019, 93, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinschroth, F.; Kowarik, I. COVID-19 Crisis Demonstrates the Urgent Need for Urban Greenspaces. Front Ecol Environ 2020, 18, 318–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mell, I.; Whitten, M. Access to Nature in a Post Covid-19 World: Opportunities for Green Infrastructure Financing, Distribution and Equitability in Urban Planning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansil, D.; Plecak, C.; Taczanowska, K.; Jiricka-Pürrer, A. Experience Them, Love Them, Protect Them—Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Changed People’s Perception of Urban and Suburban Green Spaces and Their Conservation Targets? Environ Manage 2022, 70, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehberger, M.; Kleih, A.K.; Sparke, K. Self-Reported Well-Being and the Importance of Green Spaces – A Comparison of Garden Owners and Non-Garden Owners in Times of COVID-19. Landsc Urban Plan 2021, 212, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, C.E.; Rieves, E.S.; Carlson, K. Perceptions of Green Space Usage, Abundance, and Quality of Green Space Were Associated with Better Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Residents of Denver. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0263779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Feng, T.; Timmermans, H.J.P.; Li, Z.; Zhang, M.; Li, B. Analysis of Citizens’ Motivation and Participation Intention in Urban Planning. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgio, G.; Errigo, F. Barcellona e Rotterdam Creative Cities I Casi Del Pla Buits e Della Child Friendly City. In La città creativa. Spazi pubblici e luoghi della quotidianità; Galdini, R., Marata, A., Eds.; CNAPPC: Roma, 2017; ISBN 978-88-941296-2-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. PLA BUITS Buits Urbans Amb Implicació Territorial i Social; Barcelona, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Adjuntament de barcelona. Pla d’Impuls a La Infraestructura Verda; Barcelona, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Camps-Calvet, M.; Langemeyer, J.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Gómez-Baggethun, E. Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Gardens in Barcelona, Spain: Insights for Policy and Planning. Environ Sci Policy 2016, 62, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg. More City in the City - Working Together for More Quality Open Space in Hamburg [Mehr Stadt in Der Stadt - Gemeinsam Zu Mehr Freiraumqualität in Hamburg]; Hamburg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Demaziere, C. Green City Branding or Achieving Sustainable Urban Development? Reflections of Two Winning Cities of the European Green Capital Award: Stockholm and Hamburg. Town Planning Review 2020, 91, 373–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitillo, P. Amburgo, Metropoli Verde. Territorio 1997, 4, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- CEC. OPEN SPACE 2021 - Edinburgh’s Open Space Strategy; Edinburgh, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tillie, N.; Aarts, M.; Marijnissen, M.; Stenhuijs, L.; Borsboom, J.; Rietveld, E.; Doepel, D.; Visschers, J.; Lap, S. Rotterdam- People Make the Inner City: Densification + Greenification = Sustainable City; Cressie Communication Services, Tillie, N., Doepel, D., Stenhuijs, L., Rijke, C., Marijnissen, M., Borsboom, J., Eds.; Mediacenter Rotterdam: Rotterdam, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom-Van Beurden, J.; Doepel, D.; Tillie, N. Sustainable Densification and Greenification in the Inner City of Rotterdam. In Proceedings of the CUPUM the International Conference on Computers in Urban Planning and Urban Management 13th edition, Utrecht, The Netherlands; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tillie, N.; Borsboom-van Beurden, J.; Doepel, D.; Aarts, M. Exploring a Stakeholder Based Urban Densification and Greening Agenda for Rotterdam Inner City—Accelerating the Transition to a Liveable Low Carbon City. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, I.H.; Morello, E. Are Nature-Based Solutions the Answer to Urban Sustainability Dilemma? The Case of CLEVER Cities CALs within the Milanese Urban Context. In Proceedings of the Conference: Atti della XXII Conferenza Nazionale SIU. L’Urbanistica italiana di fronte all’Agenda 2030. Portare territori e comunità sulla strada della sostenibilità e della resilienza, January 2020; Matera-BAri. [Google Scholar]

- Sanesi, G.; Colangelo, G.; Lafortezza, R.; Calvo, E.; Davies, C. Urban Green Infrastructure and Urban Forests: A Case Study of the Metropolitan Area of Milan. 2016, 42, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, I. Nature-Based Solutions across Spatial Urban Scales: Three Case Studies from Nice, Utrecht and Milan. Proc Inst Civ Eng Urban Des Plan 2024, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canedoli, C.; Bullock, C.; Collier, M.J.; Joyce, D.; Padoa-Schioppa, E. Public Participatory Mapping of Cultural Ecosystem Services: Citizen Perception and Park Management in the Parco Nord of Milan (Italy). Sustainability 2017, 9, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Ovo, M.; Corsi, S. Urban Ecosystem Services to Support the Design Process in Urban Environment. A Case Study of the Municipality of Milan. Aestimum 2020, 2020, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comune di Milano. Documento Degli Obiettivi per La Revisione Del Piano Di Governo Del Territorio Milano 2030; Milano, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lux, M.S. Networks and Fragments: An Integrative Approach for Planning Urban Green Infrastructures in Dense Urban Areas. Land 2024, 13, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzortzi, J.N.; Lux, M.S. Renaturing Historical Centres. The Role of Private Space in Milan’s Green Infrastrucutres. AGATHÓN | International Journal of Architecture, Art and Design 2022, 11, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijs, A.E.; Mattijssen, T.J.; Pn Van Der Jagt, A.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Andersson, E.; Elands, B.H.; Steen Møller, M. Active Citizenship for Urban Green Infrastructure: Fostering the Diversity and Dynamics of Citizen Contributions through Mosaic Governance. [CrossRef]

- Rastgo, P.; Hajzeri, A.; Ahmadi, E. Exploring the Opportunities and Constraints of Urban Small Green Spaces: An Investigation of Affordances. Child Geogr 2024, 22, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerer, M.; Annighöfer, P.; Arzberger, S.; Burger, S.; Hecher, Y.; Knill, V.; Probst, B.; Suda, M. Urban Oases: The Social-Ecological Importance of Small Urban Green Spaces. Ecosystems and People 2024, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilidis, A.A.; Popa, A.M.; Onose, D.A.; Gradinaru, S.R. Planning Small for Winning Big: Small Urban Green Space Distribution Patterns in an Expanding City. Urban For Urban Green 2022, 78, 127787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, S. (Ed.) Methods in Urban Analysis; Cities Research Series; Springer: Singapore, 2021; ISBN 978-981-16-1676-1. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. A Catalogue of Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Resilience; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Morello, E.; Mahmoud, I.; Colaninno, N. Catalogue of Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Regeneration; Milan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gemeente Rotterdam WeerWoord - Toolkit. Available online: https://rotterdamsweerwoord.nl/professionals/toolkit/ (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Lake Champlain Sea Grant. Absorb the Storm: Create a Rain-Friendly Yard and Neighborhood. A Guide for Residents Interested in Protecting Their Local Streams and Lake Champlain; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Saving the Rain. Green Stormwater Solutions for Congregations; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Compendium of MS4 Permitting Approaches; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Popolazione Residente - Comune Di Milano. Available online: https://www.comune.milano.it/aree-tematiche/dati-statistici/pubblicazioni/popolazione-residente (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Lux, M.S.; Biraghi, C.A. Green Spaces Accessibility in Historic Urban Centres. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems 2024, 1186 LNNS, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartieri Resilienti - Milano Cambia Aria - Comune Di Milano. Available online: https://www.comune.milano.it/web/milano-cambia-aria/progetti/quartieri-resilienti (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Karam, G.; Hendel, M.; Cécilia, B.; Alexandre, B.; Patricia, B.; Laurent, R. The Oasis Project: UHI Mitigation Strategies Applied to Parisian Schoolyards. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alméstar, M.; Romero-Muñoz, S. (Re)Designing the Rules: Collaborative Planning and Institutional Innovation in Schoolyard Transformations in Madrid. Land 2025, 14, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Mas, M.; Continente, X.; Marí-Dell’Olmo, M.; López, M.J. Community Use and Perceptions of Climate Shelters in Schoolyards in Barcelona. International Journal of Public Health 2025, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fior, M.; Galuzzi, P.; Vitillo, P. Well-Being, Greenery, and Active Mobility. Urban Design Proposals for a Network of Proximity Hubs along the New M4 Metro Line in Milan. TeMa - Journal od Land Use, Mobility and Environment 2022, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fior, M.; Galuzzi, P.; Vitillo, P. New Milan Metro-Line M4. From Infrastructural Project to Design Scenario Enabling Urban Resilience. Transportation Research Procedia 2022, 60, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassileva, A.; Simić, M. Green Public-Private Partnerships: Global and European Context and Best Practices. Technogenesis, Green Economy and Sustainable Development 2023, 2, 161–188. [Google Scholar]

- Koppenjan, J.F.M. Public–Private Partnerships for Green Infrastructures. Tensions and Challenges. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 2015, 12, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, X.; Wen, J.; Du, S.; Zhang, M.; Ke, Q. Residents’ Willingness to Participate in Green Infrastructure: Spatial Differences and Influence Factors in Shanghai, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różewicz, D. Rotterdam’s Sustainability Strategy: A Case Study on Municipal Policies. Semestre Económico 2020, 23, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Tilie, N. The Dynamics of Urban Ecosystem Governance in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Ambio 2014, 43, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillie, N.; van der Heijden, R. Advancing Urban Ecosystem Governance in Rotterdam: From Experimenting and Evidence Gathering to New Ways for Integrated Planning. Environ Sci Policy 2016, 62, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).