Submitted:

24 October 2024

Posted:

24 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Italian regulatory and policy framework

3. Materials and Methods

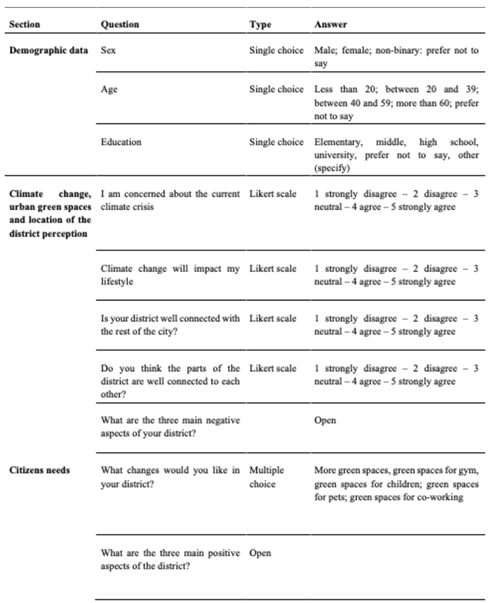

- Analysis of the territorial context: This stage aims to reveal the spatial processes to identify and define the potential, aspirations and needs for a definite territory, from a social, economic, and environmental perspective to give value to natural and cultural landscape elements in urban scale. Data collection is performed through an objective (statistics, plans and programs) and subjective (citizen’s opinions and perceptions) approach. We employ a combined approach of in-depth interviews and content analysis of key policy plans and documentation related to greenspace planning and/or climate change adaptation to evaluate competence areas in our case study city.

- Identification of main issues: A SWOT analysis is carried out as a strategic planning tool to identify the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of the context.

- Identification of project actions: To come from the questionnaires given to the citizens and from the analysis of the territorial context through a participatory process.

- Definition of the integrated scenario: Experts and citizens together develop a project proposal taking into the contextual constraints and the preferences expressed by the citizens.

- single-choice questions, where respondents selected only one option;

- multiple-choice questions, allowing respondents to select more than one option;

- single-choice items presented on a psychometric Likert scale, requiring respondents to rate their agreement with specific statements (five-point scale: 1 - strongly disagree to 5 - strongly agree).

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the territorial context: The case of San Bartolomeo District

3.2. Residents' perceptions

3.3. Identification of critical issues

- located in a historically and environmentally significant area;

- availability of undeveloped land;

- sports facilities;

- adequate parking spaces to current needs;

- quiet residential environment;

- neighborhood-level facilities and proximity to local and regional services.

- served by local public transportation;

- WiFi hotspots

- not efficient road network and public transport;

- limited pedestrian connections and reliance on cars;

- lack of neighborhood-scale energy initiatives (photovoltaic systems or energy communities);

- lack of smart devices (devices for electric charging, lockers, neighborhood apps);

- absence of common spaces and concierge services;

- deterioration of the Municipal Market;

- isolation determined by the presence of elements of separation;

- fragmentation due to the presence of heavy mobility systems,

- safety concerns;

- insufficient and unevenly distributed green areas;

- promoting activities related to nearby environmental and sports facilities..

- reconverting empty spaces into green areas for social purposes.;

- benefits from the new stadium of Cagliari calcio (urban park, promenade, and football school)

- realization of a light rail station near the Cagliari Calcio Stadium.

- Threats:

- potential for traffic congestion due to football matches and growing visitors;

- limited parking availability for the expected influx of visitors to the new Cagliari Calcio Stadium.;

- risk of neighborhood decline due to degradation;

- presence of unqualified residual spaces;

- disconnected green (via Tramontana near the Molentargius Park, Viale San Bartolomeo which extends to CalaMosca) and blue infrastructure routes (the Rio Palma navigable canal which radiates from Molentargius to intercept an important segment of the Cagliari waterfront).

3.4. Definition of project actions

- Spirulina production plant

- 2.

- Hydroponics Systems

- 3.

- Eco-compactor

- 4.

- Little Composting System

- 5.

- Co-Working

- 6.

- Floor drainage

- 7.

- Buffer strip

- 8.

- Urban Agriculture

- 9.

- Kayak anchoring

- 10.

- Cardio outdoor gym that generates electricity

- 11.

- District’s open-air market

- 12.

- Solar panels

- Illuminating poorly lit areas of the St. Bartolomeo district at night, thereby enhancing the livability of public spaces and promoting social activities;

- Charging e-bikes and scooters for residents and visitors to Cagliari who are drawn to the stadium and the surrounding sports facilities.

- 13.

- Energy-generating floor

- 14.

- Cycling and walking paths

- Citizens’ health by promoting increased engagement in sports activities

- Reducing air pollution

- Fostering environmentally sustainable mobility within the district and its neighboring areas

- 15.

- Tactical urban planning solutions for road intersections

- 16.

- Smart Totems

- measuring and monitoring air quality in the district by increasing the number of monitoring points across the City of Cagliari and expanding the range of detectable pollutants to include not only PM2.5 but also PM10, O3, NO2, and SO2;

- collecting solar energy through vertically integrated solar cells, thereby reducing CO2 emissions by approximately 300 kg per year for each totem, based on Italy's energy production mix;

- providing illumination during nighttime;

- supplying power for e-bikes and electric kick-scooters;

- offering free Wi-Fi connectivity;

- serving as an information point for mobility issues and daily events in the city and district.

- 17.

- Improvement of the St. Elia local market

- 18.

- Linear green

- Enhancing the visual experience of the area, ensuring a level of visual complexity that increases the enjoyment of green spaces;

- Strengthening ecological corridors to promote territorial and ecosystem continuity;

- Reducing fine dust and pollutants in the atmosphere, as these green surfaces serve as effective physical, chemical, and physiological filters against harmful airborne particulates;

- Establishing a barrier to mitigate noise pollution generated by vehicular traffic.

- 19.

- Green Areas

- 20.

- Green roof and green wall

- Providing insulation for living spaces and contributing to energy savings, while also mitigating the landscape discontinuities created by the new neighborhood's construction;

- These walls will effectively address the interruption of the skyline formed by the heights of the new buildings, harmonizing the view with the backdrop of St. Elia’s hill.

- 21.

- Rain garden

- green Barrier: they serve as a green buffer surrounding the cycling and pedestrian paths, providing a clear separation from other road infrastructures. This green component not only delineates the pathway but also ensures adequate visibility for both pedestrians and cyclists, enhancing safety;

- phytoremediation: the water collected from impervious surfaces often contains significant pollutants. Therefore, the selected plant species for the rain gardens will also play a crucial role in phytoremediation—either inactivating or retaining these harmful substances within their tissues.

- 22.

- Mini static bio stabilization plant

- 23.

- Water houses

- 24.

- Aquaponic plants.

- 25.

- Grow it yourself

- 26.

- Business Mentoring

- 27.

- Eco-friendly Citizens

3.5. Definition of the integrated scenario

- Co-working/hub for digital start-up with spaces and workstations with ample light sources and common areas (to encourage contamination between people with different experiences), these environments will be partially separated by hydroponic/aquaponics systems. There will also be areas for relaxation and physical activity with sports equipment from which energy can be produced.

- Laboratory for smart cities, urban agriculture - a sort of “Think-Thank” formed by agronomists, engineers, architects, planners, experts in public procurement/partnerships/concessions, researchers, representatives of the productive world and administrators to redefine new parameters and solutions for the arrangement of cities and its relationship with the territory.

- eco-sustainable gymnasium, the equipment will be placed outdoors and will allow energy to be produced through use by the athletes;

- canoe anchorage, for those who wish, it will be possible to use this type of boat to do sports activities in the St. Bartholomew Canal. Buffer strips may also be built here (Fig. 2 point 7);

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Box 1 - Modena

Box 2 - Florence

Box 3 - Bolzano

Box 4 - Mantua

Box 5 - Prato

Box 6 - Messina

- increase citizens' knowledge and awareness and increase and enhance their participation in the care and development of the city's tree heritage,

- optimize the management of the city green by reorganizing processes from a full-digital perspective and with mobile technologies for public green operators,

- make city green data and content available with open-data and webGIS interfaces.

Box 7 - Milan

- Increase the tree canopy cover by 5% compared to the 16% of existing Tree Canopy of the Metropolitan City, which will make Milan one of the main cities in Europe and in the world to focus on Tree Canopy Cover; 1

- Increase the biodiversity of plant and animal species in urban, peri-urban and agricultural areas;

- Reduce land consumption, thanks to the creation of green barriers;

- Increase green and blue infrastructures and ecological connections between the

- different parts of the Metropolitan Area;

- Enhance the existing green infrastructure (GI) heritage, systematizing

- all the green surfaces, large parks and PLIS of greater Milan,

- through a large urban forestry project.

- Ensure inclusion and social cohesion through community projects for the redevelopment of the suburbs;

- Experiment in pilot areas with new models for the management and design of urban green areas;

- Reduce the average condition of air pollution

- Promote the creation of shared and community forms of green management,

- both rural and ornamental;

- Reduce the “heat island” phenomenon, with a local temperature drop from 2 °C to 8 °C within urban areas; 3

- Increase the number and size of permeable soil surfaces that allow the reabsorption of rainwater (improvement of water run-off) and the reduction of hydrogeological risk;

- Reduce energy consumption dictated by air conditioning, setting the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 (Net-zero emissions 2050, C40 Cities);

- Reduce the average condition of air pollution (30 μg/m3 of PM2.5n particles, 3 times the WHO1 safety level)

Appendix B

References

- Wissink, B.; van Kempen, R.; Fang, Y.; Li, S.-M. Introduction: Living in Chinese Enclave Cities. Urban Geography 2012, 33(2), 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angotti, T. The New Century of the Metropolis: Urban Enclaves and Orientalism; Routledge: New York, NY, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- He, S. Evolving Enclave Urbanism in China and Its Socio-Spatial Implications: The Case of Guangzhou. Social and Cultural Geography 2013, 14(3), 243–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, T. Fortified Enclaves: The New Urban Segregation. Public Culture 1996, 8, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meninno, C. Enclavi commerciali trasformazioni architettoniche, urbane e territoriali. In The shopping center as/is a meeting place; Rodani V, M.C.E., Ed.; GECA Srl - San Giuliano Milanese (MI) per EUT Edizioni Universitarie Trieste, 2020; pp. 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont, H.; Balian, E.; Azevedo JM, N.; Beumer, V.; Brodin, T.; Claudet, J.; Fady, B.; Grube, M.; Keune, H.; Lamarque, P.; Reuter, K.; Smith, M.; Van Ham, C.; Weisser, W.W.; Le Roux, X. Nature-based Solutions: New Influence for Environmental Management and Research in Europe. GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society 2015, 24(4), 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Dawson, R.J.; Urge-Vorsatz, D.; Delgado, G.C. Six research priorities for cities and climate change. Nature 2018. [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Qureshi, S.; Haase, D. Human–environment interactions in urban green spaces — A systematic review of contemporary issues and prospects for future research. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2015, 50, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.; Breil, M.; Nita, M.; Kabisch, N.; de Bel, M.; Enzi, V.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Geneletti, G.; Lovinger, L.; Cardinaletti, M.; Basnou, C.; Monteiro, A.; Robrecht, H.; Sgrigna, G.; Muhari, L.; Calfapietra, C.; Berry, P. An impact evaluation framework to support planning and evaluation of nature-based solutions projects. Report prepared by the EKLIPSE Expert Working Group on Nature-based Solutions to Promote Climate Resilience in Urban Areas. Centre for Ecology and Hydrology 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Egorov, A.I.; Mudu, P.; Braubach, M.; Martuzzi, M. (Eds.) Urban green spaces and health; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ugolini, F.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use and perceptions of urban green space: an international exploratory study. Urban forestry & Urban greening 2020, 56, 126888. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/urban-forestry-and-urban-greening/vol/56/suppl/C.

- Paradiso, M. Per una geografia critica delle «smart cities». Tra innovazione, marginalità, equità, democrazia, sorveglianza. Bollettino della Società Geografica Italiana 2013, XIII, VI, 679–693. [Google Scholar]

- Auci, S.; Mundula, L. La misura delle smart cities e gli obiettivi della strategia EU 2020: una riflessione critica. Geotema 2019, 59, 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, M. Mobilità urbana e sostenibile tra innovazione e partecipazione (webinar, 21 maggio 2020). Semestrale di Studi e Ricerche di Geografia 2020, XXXII, 147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Vanolo, A. Smartmentality: the smart city as disciplinary strategy. Urban Studies 2014, 51, 883–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siniscalchi, S. Smart City e governance del territorio. Le potenzialità degli opendata cartografici attraverso alcuni casi di studio. Bollettino della Associazione Italiana di Cartografia 2017, 160, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas, C.; Kim, J.; Chi, S. Natural language processing-based characterization of top-down communication in smart cities for enhancing citizen alignment. Sustainable Cities and Society 2021, 66, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantrell, B.E.; Martin, L.J.; Ellis, E.C. Designing Autonomy: Opportunities for New Wildness in the Anthropocene. Trends in ecology & evolution 2017, 32, 156–166. [Google Scholar]

- DiSalvo, C.; Jenkins, T. Fruit are Heavy: A prototype public IoT system to support urban foraging. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Blessi, G.T.; Grossi, E.; Sacco, P.L.; Pieretti, G.; Ferilli, G. The contribution of cultural participation to urban well-being. A comparative study in Bolzano/Bozen and Siracusa, Italy. Cities 2016, 50, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luvisi, A.; Lorenzini, G. RFID-plants in the smart city: Applications and outlook for urban green management. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 13(4), 630–637. [CrossRef]

- Sandbrook, C.; Adams, W.M.; Monteferri, B. Digital Games and Biodiversity Conservation. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, P.; Møller, M.S.; Olafsson, A.S.; Snizek, B. Revealing Cultural Ecosystem Services through Instagram Images: The Potential of Social Media Volunteered Geographic Information for Urban Green Infrastructure Planning and Governance. Urban Planning 2016, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor Buck, N.; While, A. Competitive urbanism and the limits to smart city innovation: The UK Future Cities initiative. Urban Studies 2017, 54(2), 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrys, J. A Cosmopolitics of Energy: Diverging Materialities and Hesitating Practices. Environment and Planning A 2014, 46(9), 2095–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COM 2020 Biodiversity strategy for 2030, Biodiversity strategy for 2030 - European Commission (europa.eu).

- PNRR. Available online: https://www.governo.it/sites/governo.it/files/PNRR.

- Pozoukidou, G.; Chatziyiannaki, Z. 15-Minute City: Decomposing the New Urban Planning Eutopia. Sustainability 2021, 13(2), 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Sharifi, A.; Hajian Hossein Abadi, M.; Moradi, Z. From Garden City to 15-Minute City: A Historical Perspective and Critical Assessment. Land 2023, 12(2), 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisch, J. Green Infrastructure and the Sustainability Concept: A Case Study of the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan. University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations, 2014; p. 1869. [Google Scholar]

- Lefever, S.; Dal, M.; Matthíasdóttir, Á. Online data collection in academic research: Advantages and limitations. Br J Educ Technol 2007, 38, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltar, F.; Brunet, I. Social research 2.0: Virtual snowball sampling method using Facebook. Internet Res 2012, 22, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daikeler, J.; Bošnjak, M.; Lozar Manfreda, K. Web versus other survey modes: An updated and extended meta-analysis comparing response rates. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology 2020, 8(3), 513–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, E.; Guadagno, E. Perception of climate change impacts, urbanization, and coastal planning in the Gaeta Gulf (central Tyrrhenian Sea): A multidimensional approach. AIMS Geosciences 2024, 10(1), 80–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, J. Planning for an extensive open space system: linking landscape structure and function. Landsc Urban Plan 1991, 21(1–2), 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, H.; Vala, J.; Schaefer, V. Importance of backyard habitat in a comprehensive biodiversity conservation strategy: a connectivity analysis of urban green spaces. Restor Ecol 2002, 10(2), 368–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herzele, A.; Wiedemann, T. A monitoring tool for the provision of accessible and attractive urban green spaces. Landscape Urban Plan 2003, 63(2), 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Yin, H.; Nakagoshi, N.; Zong, Y. Urban green space network development for biodiversity conservation: identifcation based on graph theory and gravity modeling. Landsc Urban Plan 2010, 95(1–2), 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.C.; Maheswaran, R. The health benefts of urban green spaces: a review of the evidence. J Public Health 2011, 33(2), 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dillen, S.M.; de Vries, S.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Greenspace in urban neighbourhoods and residents’ health: adding quality to quantity. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012, 66(6), e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).