1. Introduction

Over the last century, rapid development in cities and urban areas in terms of number, density, and dimensions has resulted in social and environmental challenges. The development, based only on economic progress and profits, outweighs the sustainability of social well-being and the natural environment. As cities encounter challenges from growing populations within limited space, the crucial roles of urban green infrastructure in mitigating adverse impacts caused by rapid urban development have been increasingly recognised. A large body of studies verifies that urban green infrastructure within the urban fabric, composed of diverse spatial components, such as public gardens and parks, intensively cultivated fields, green surfaces and traffic greenery, helps to reduce urban heat islands [

6,

35,

64], promotes urban-natural balance [

27,

41] and community well-being [

20,

62], and mitigates the negative effect of climate change [

36].

In Zurich, rapid population growth and its direct consequence—an increase in buildings and building density—have raised public concern regarding the availability of green spaces and urban greenery within built areas. The anticipated growth of an additional 25% of the population, in contrast to the public consensus favouring densifying existing city areas rather than extending urban boundaries, implies a more compact living environment emerging in the coming decades. This calls for serious consideration to create a built environment that can fulfil urban development needs, balance the relationship between construction and nature, and maintain, if not improve, the quality of life in Zurich. The challenge is evident. On the one hand, population growth necessitates increasing both living and working spaces in the city; on the other hand, the federal and cantonal governments are committed to preserving areas for forests and agricultural fields and offering public gardens, open spaces, recreational areas and other forms of urban greenery to robust urban live and resilience, including regenerating urban ecosystem, bettering the living environment and enhance social integration and equality. To overcome the challenge, a comprehensive understanding of urban green infrastructure and its implications from various perspectives is indispensable.

The current discourse primarily investigates the environmental, social, and economic benefits of urban green infrastructure. However, it is imperative to adopt a comprehensive and integrated approach to fully comprehend the multifaceted roles of urban green infrastructure within urban settings. This necessity arises not only from the interconnections among various functions but also from its potential to assist decision-making processes that balance diverse priorities in urban planning and design [

1,

4,

5,

17], prevent trade-offs between ecological, social, and economic values, and avoid conflicts between stakeholder perspectives [

26].

This study was conducted as part of the research module "Dense and Green Cities" at the Future Cities Laboratory Global, which aims to explore strategies and approaches for urban densification and transformation in Zurich. The study sought an integrated spatial analysis approach that synthesises the urban green infrastructure quality and land features by combining social and ecosystem perspectives, thereby generating spatial patterns that contribute to strategic recommendations for enhancing local green spaces based on an overall comprehension at the district scale. Following the introduction session, the paper outlines the methodological strategies and approaches for investigating and clustering urban green infrastructure factors from multiple perspectives. Utilising the integrated land feature clustering map and detailing the characteristics of each cluster, the paper provides insights aimed at optimising urban green infrastructure in the studied district. In conclusion, the paper discusses its limitations and offers suggestions for further development.

2. Methods

2.1. Methodologies and Framework

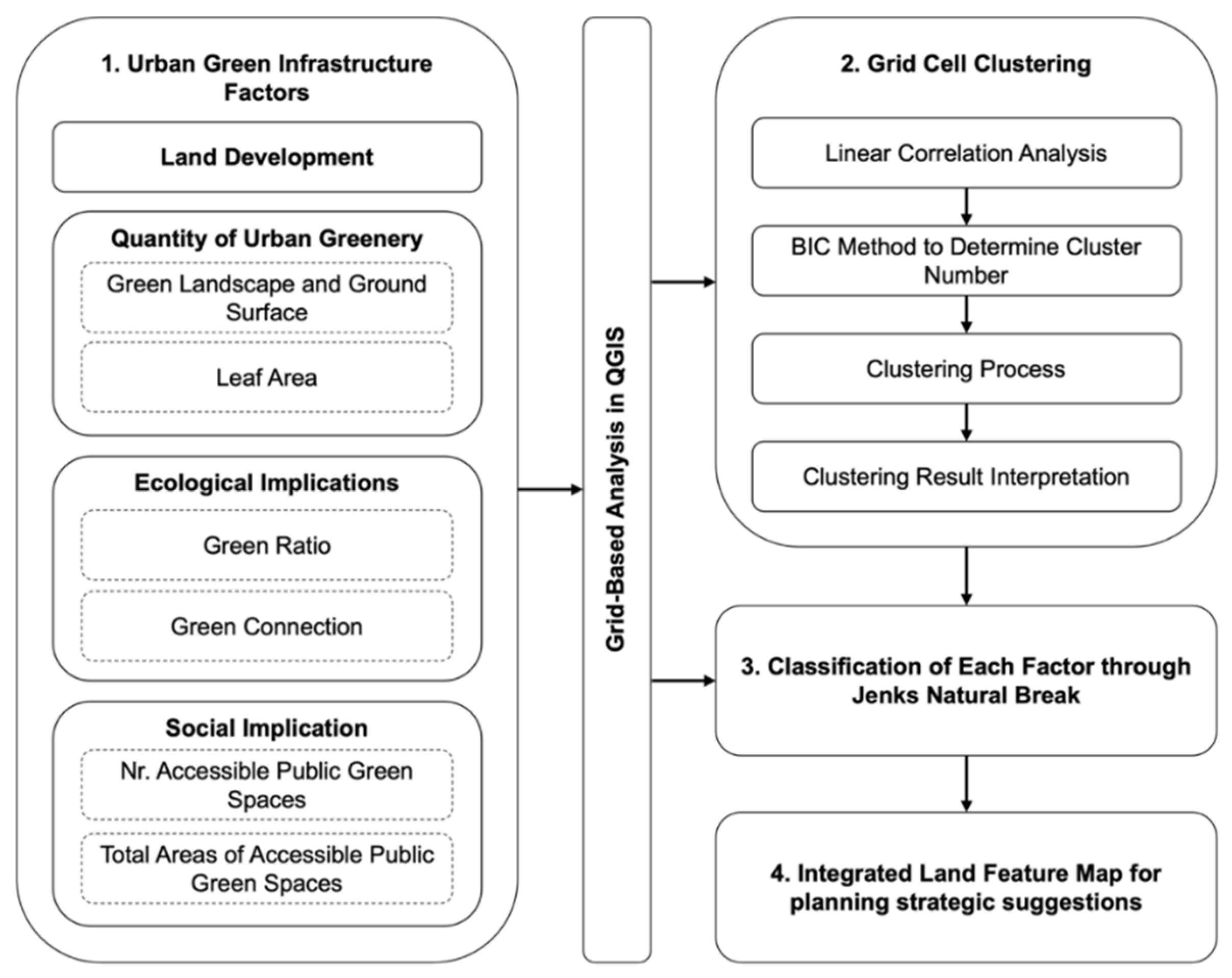

This study aims to delineate and optimise the provision of urban green spaces, framed within a comprehensive understanding of land features related to social and environmental functions. To achieve this goal, the research was structured into four distinct phases (

Figure 1). The initial phase involved assessing the availability of green space by analysing factors such as green surface area, leaf areas, green ratio, connectivity for natural habitats, and the accessibility of public green spaces that promote social health and community integration, all within a geographic information system (GIS). The findings were visualised using a rectangular grid system measuring 10 meters by 10 meters, transforming polygon-based land plot data into standardised grid cells to enhance comparison and integration.

The subsequent phase examined the interrelations among these factors and employed statistical algorithms to differentiate the grid cells, clustering them into groups with similar greenery characteristics, resulting in a clustering map of the studied area. After categorising each measured factor into ten distinct levels, the cluster centroids, representing the average values of each factor, illustrated the characteristics of the clusters through seven-dimensional radar charts. This approach enabled the study to identify patterns in land features across the district, functioning as a decision-support tool and providing valuable insights for optimising green infrastructure within the district for planners, designers, and policymakers.

2.2. Study Area

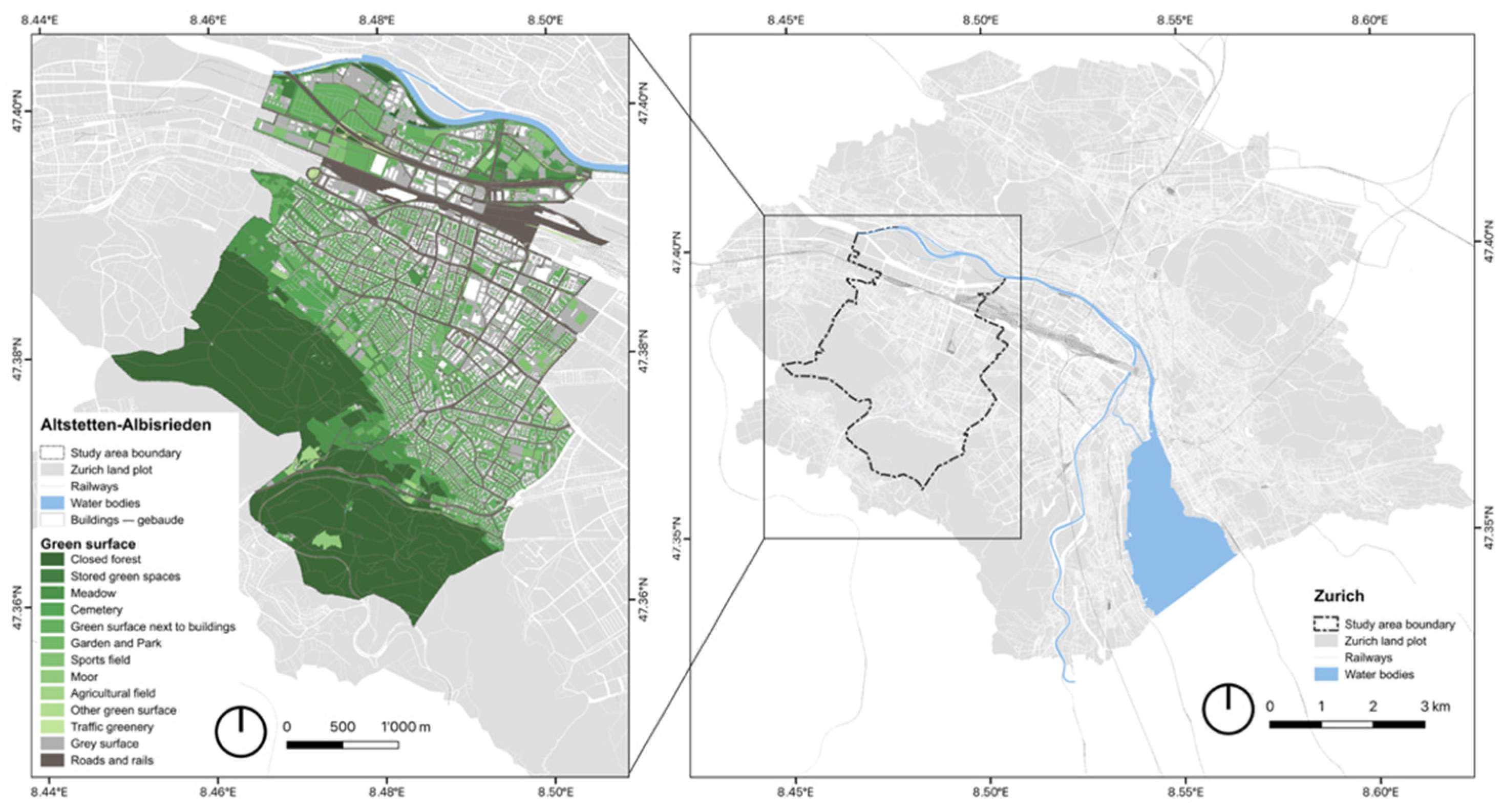

Altstetten-Albisrieden is located to the west of Zurich City, covering an area of 12.1 square kilometres, ranging from the Limmat River in the northeast to the Uetliberg mountains in the southwest (

Figure 2). This region showcases a diverse landscape characterised by various geographic features, with railways at its heart and mountains delineating its boundaries. As one of the earliest incorporated communities, Altstetten-Albisrieden presents a mix of architectural styles and urban forms, from single-family homes to modern high-rise buildings, reflecting the evolution of urban development over time. Currently, Altstetten has a population of 34,098 residents, 18,059 housing units, and 46,839 jobs, with 47% of the area developed and 28% designated as green space. In contrast, Albisrieden is home to 22,412 residents, 12,000 housing units, and 12,310 jobs, with 41% of the area developed and 43% covered by forest. In pursuit of enhancing green infrastructure in the construction areas, the study excluded closed forests adjacent to the river and the mountain foothills from its analysis.

2.3. Urban Green Infrastructure Factors

A comprehensive analysis of sustainable urban development strategies and guidelines, spanning from global to Swiss regional contexts, highlights critical principles for Switzerland's Green Urban Agenda. These principles emphasise the importance of preserving urban nature, ensuring high-quality open and public spaces, promoting accessibility to public green areas and essential facilities within short distances from residential neighbourhoods, and enhancing social inclusion while safeguarding natural resources [

43].

To address these principles, the investigation of urban green infrastructure focused on two main aspects: green space availability and accessibility. The quantity-based measure of green space availability assesses the provision of green surfaces and leaf areas, revealing the extent of green space in terms of land use and coverage. This measure interacts with development density, influencing environmental processes such as the reduction of noise and air pollution, as well as heat mitigation [

6,

41]. Consequently, these factors contribute to individual health [

11,

31,

58] and foster spatial connections that support ecological sustainability [

41,

67].

On the other hand, distance-based green accessibility examines the spatial distribution of public green spaces and their accessibility to district residents, reflecting human behaviours and daily physical activities [

68], as well as considerations of social justice and community cohesion [

19]. The study intentionally included factors related to green infrastructure and land characteristics, such as land development, green surface area, leaf area, green ratio, green connectivity, and the number and total area of accessible public green spaces.

2.4. Data

The study utilised relevant geo-information and data obtained from the City of Zurich's open-access resources in 2021, which comprised building information, household locations, land use, and tree data. Updated building information detailing the number of households and job positions within each structure was acquired from the City of Zurich in 2023. Furthermore, the study employed street networks sourced from OpenStreetMap to analyse spatial connections and assess service coverage areas of public green spaces throughout the district.

2.5. 10-Metre Rectangle Grid for Data Analysis and Visualisation

The study utilised grid-based analysis to visualise, integrate, and cluster spatial data from various factors. This approach is particularly effective for managing continuous datasets and enhances the understanding of spatial phenomena across a landscape [

2]. Recognising that grid size can significantly impact analysis results [

13,

24,

29], the study adopted a grid size of 10 meters, as recommended by N. Dong et al. [

13], to delineate the general profiles of buildings and other spaces.

Furthermore, the preference for grid-based analysis over direct use of land plots provided in the geo-information arises from several considerations:

Many projects are developed across adjacent land plots to optimise building volume and green spaces. In such instances, relying solely on plot data from geo-information does not accurately represent the actual distribution of green, grey, and built surfaces.

Most buildings have direct connections to roads and streets, and land plots do not adequately group buildings or establish a coherent spatial hierarchy beyond individual structures. This is especially relevant when analysing accessibility to green spaces; thus, land plots are more suited to administrative purposes than to fostering spatial development.

2.6. Methods and Application

2.6.1. Land Development

The land development analysis examined the constructed surface area and construction volume within the targeted regions. This included roadways, streets, railways, building footprints, and other impervious surfaces that were classified as constructed surfaces, along with building floor areas contributing to the overall construction volumes. The geo-information related to roadways, streets, railways, and other impervious surfaces was obtained directly from the City of Zurich, while the building floor areas were derived from the polygons representing building footprints, combined with the updated building floor counts as of 2023 provided by the City of Zurich.

2.6.2. Green Surface in Land Use

The essential geographical information regarding green spaces was derived from open-source data provided by the City of Zurich. This data includes attributes such as polygon geometries and classifications of green spaces. Given that multiple plots within the district have experienced redevelopment over the past five years, on-site observations and Google Earth imagery were also used to update and verify the geographical information concerning these green areas.

2.6.3. Leaf Area

The study used the Leaf Area Index (LAI) to assess the density of leaves within the district. The LAI is a critical metric in the field of climate change research [

15]. It measures half the total intercepting area per unit of ground surface area [

9] and quantifies the amount of leaf area in an ecosystem [

15]. The leaf area calculation of this study consists of two parts: the ground green surfaces and the canopies of trees in the urban area. The green ground surfaces functioning as open spaces in gardens and parks and green landscape areas surrounding buildings, urban farming areas and intensively cultivated fields were calculated as grasslands, gardening fields and crop fields, respectively. The leaf area of tree canopies was determined using the particular LAI values along with tree information such as canopy dimension and species information provided by the City of Zurich.

A substantial body of research has examined and quantified the LAI values of various vegetation species, employing diverse methodologies and perspectives. Since LAI values can fluctuate significantly due to numerous factors affecting plants, such as cultivation conditions, age, season, life stages, and the methods of measurement [

15], this study adopted LAI values, listed in

Table 1, grounded in specific principles.

The case study area encompasses over two hundred tree species. The study streamlined the information and categorised these species based on their respective vegetation genus and Latin nomenclature.

Considering the impact of climate on vegetative growth, the study primarily selected LAI values from research conducted within temperate climate zones that closely resemble the studied area. In instances where specific LAI values were not available from the aforementioned research, the study utilised data from tropical zones, particularly referencing the vegetation database provided by EarthData, NASA, and the Flora & Fauna Web by Singapore National Parks.

For tree species lacking available LAI values, the study adopted general LAI values pertinent to broadleaf and coniferous trees.

In addressing the variations in canopy structure and leaf density across different life stages, particularly the seasonal fluctuations in deciduous trees, the study favoured LAI values corresponding to mature trees measured during the period of maximum foliage, typically from early summer to early autumn, with variations depending on plant species and cultivation techniques.

Numerous studies have examined the divergence in LAI values among tree species attributable to the application of diverse measurement and calculation methods, including litter traps, Allometric methods, Digital Hemispherical Photography (DHP), and Tracing Radiation and Architecture of Canopies (TRAC) [

15]. In such instances, the study preferred to utilise either the proposed LAI value from the existing research or the average values obtained from various measurement approaches.

Urban farming zones are areas where vegetables and flowers are typically cultivated. The study applied the average LAI value for several common vegetables and flowers. The intensively cultivated fields within the case study recorded an LAI value of 2.9, referencing the statistics derived from the LAI dataset by region [

21]. Furthermore, the LAI value associated with grassland is significantly correlated with the height of grasses and the species present within a given year. For the case study, the mean LAI value of 2.9 was utilised, as recorded in Italy during the summer months [

3].

2.6.4. Green Ratio and Connection

The ongoing growth of the human population and the expansion of urban areas, characterised by buildings and infrastructure, have led to the overexploitation of natural resources and posed significant threats to natural habitats [

45]. Habitat fragmentation occurs when larger, interconnected habitat areas are divided into smaller, isolated patches due to human development, infrastructure, and natural processes. This fragmentation poses serious challenges to landscape connectivity, which is crucial for biodiversity and climate stability [

12,

40,

45].

The study introduces the green ratio as one perspective on how the development in the studied district facilitates or impedes animals’ movement among green patches. Opposed to the concept of landscape resistance [

54,

66], the green

ratio indicates the impacts of environmental factors on natural habitat movement and ecosystems. A high green ratio implies easy movement across patches, while a low ratio represents limited movement or a barrier to movement.

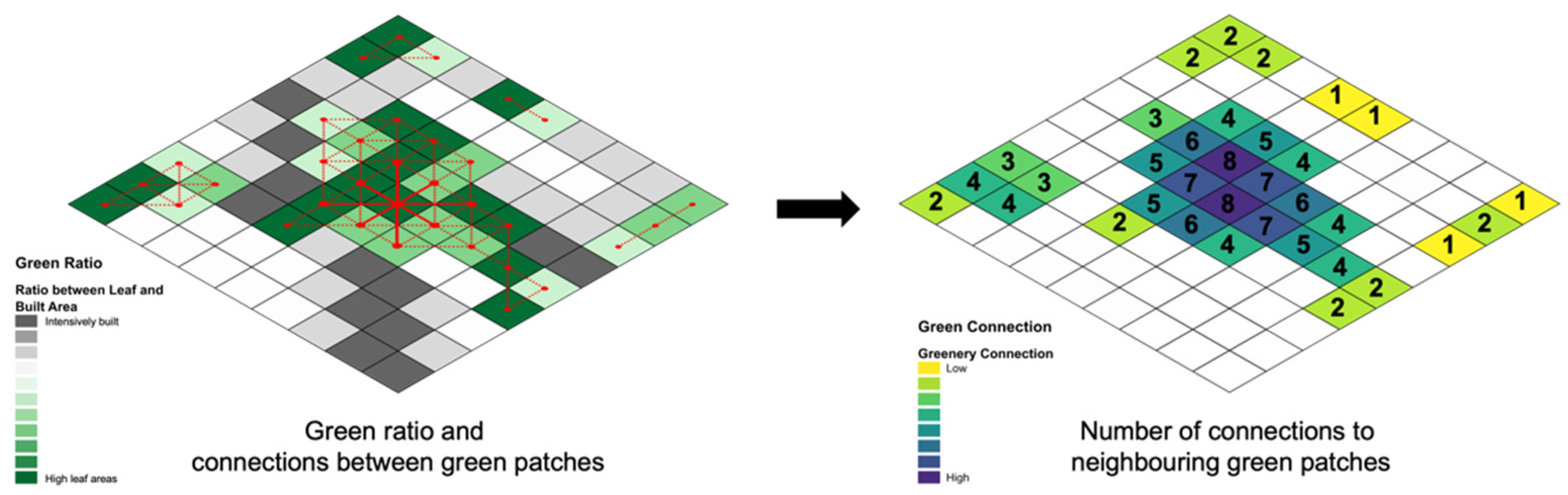

Referring to the de-fragmentation concept given by the Singapore National Parks Abroad (NParks) and its categorisation of spatial resistance in urban areas, the calculation of green ratio in this study used the ratio between the leaf and built areas to indicate the facilitation level from intensive developed areas to high-quality green areas, including environmental variables such as land use (e.g. green landscape and grey landscape), roads and streets, human development (e.g. buildings and other structures) and leaf areas. In accordance with the concept of de-fragmentation, which entails the establishment of green pathways or corridors to connect fragmented green spaces or landscapes, the study utilised the analytical tool Distance Matrix within QGIS to discern the connections of each patch possessing a specific leaf area to its neighbouring green surfaces and vegetation, indicated in

Figure 3. This analysis highlights potential green connections within the district.

The study examined the social implications of green spaces in relation to their accessibility. It predominantly focused on publicly accessible green spaces, including city parks, gardens, open green spaces, and sports fields, under the ownership of the municipality. The analysis was organised around two critical factors: the number and total area of accessible public green spaces situated within an 800-meter walking distance.

The methodology utilised in this study employs a centroid point or entrance when the dimensions of the space exceed 400 meters to represent the geographical location of each public green space. By integrating the street network, the 800-meter service catchment areas are delineated through vector processing tools, specifically employing Service Area and Hull functions within QGIS. The count of overlapping service areas reflects the number of accessible public green spaces. Given the diverse range of spatial dimensions of public green spaces across the studied district, this study further correlates the number of accessible public green spaces with their respective sizes to evaluate the total area of accessible public green spaces across various segments of the district. This analysis indicates the usage density of public green spaces and assesses the equity of their allocation.

2.6.6. Data Clustering Based on the Multiple Parameters of Green Space

The objective of the study was to systematically analyse the land features and their patterns, thereby structuring the classification of land areas based upon their similarities related to green factors. Accordingly, clustering methods were selected to examine the dataset derived from the seven measured factors. The data clustering process commenced with an evaluation of the data distribution across each factor and the relationships among those factors pertinent to urban green infrastructure. Initially, the information regarding the measured factors was standardised and consolidated into their respective grid cells, aggregating all cells into a comprehensive data matrix. The Pearson Correlation Coefficient analysis was utilised to evaluate the linear relationships among the factors.

The data matrix was characterised by high dimensionality and identified the K-Means clustering method as the principal approach. However, the distribution of the dataset, represented within a three-dimensional coordinate system exhibiting varying density, highlighted the applicability of both the Density-Based Clustering method (DBSCAN) and the Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) in conjunction with Principal Component Analysis (PCA). In order to execute the K-Means algorithm, the study utilised the Elbow Method to ascertain the optimal number of clusters (K value) for the algorithm, and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) was applied to determine the suitable number of clusters. The optimal K value was subsequently employed within the K-Means clustering methodology to distinguish the datasets into discrete clusters. Simultaneously, the two critical parameters, epsilon (eps) and the minimum number of data points necessary for the application of the DBSCAN algorithm, were established through the K-distance graph. The GMM algorithm does not necessitate any predetermined parameters; however, PCA analysis can significantly enhance the efficacy of clustering outcomes by reducing dimensionality. The results derived from all methodologies were projected for comparison within the studied area utilising QGIS. The Dunn index was employed to assess the quality of the clustering results.

2.6.7. Classification for Feature Description

To elucidate the overarching characteristics of the factors associated with each cluster, the study employed the Jenks Natural Break classification method in order to categorise the dataset pertaining to each measured factor into ten distinct classes. This methodology effectively organises the data into classes that minimise the within-class variance while maximising the between-class variance during the calculations [

7]. The centroid of each cluster with the mean values of the factor classes was utilised to produce radar charts that visually represent the distinctive characteristics of each cluster.

3. Results

3.1. Land Development and Greenery Availability

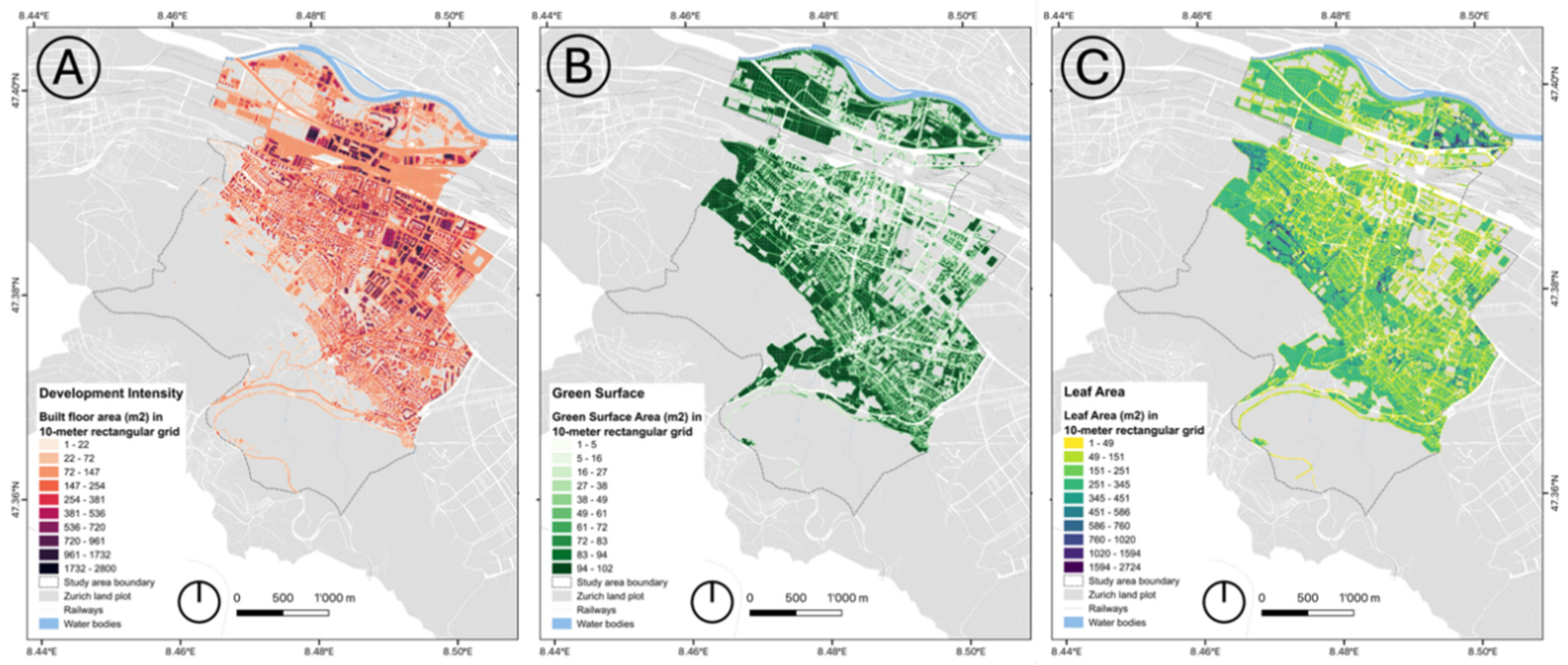

The subsequent figures (

Figure 4A–C) present a comprehensive land development, green space, and leaf area analysis. As the colour gradient darkens within each figure, it indicates an increased concentration of measured factors within the respective grid cells. These figures illustrate the extent of land development, while areas characterised by intensive development and high-density buildings, particularly along railway lines and in the eastern sector of the district, are represented by grey surfaces. In contrast, residential areas feature only essential pathways for vehicular and pedestrian movement, thereby preserving substantial ground surfaces dedicated to green spaces. Beyond the green spaces, immediate surrounding buildings, public gardens, sports fields, urban gardening plots, and cultivated fields situated at the periphery make a significant contribution to the overall availability of green spaces. Given that the majority of green areas within the urban environment are adorned with turf and shrubs, the leaf area across the district remains relatively consistent. However, the presence of trees in public gardens, sports fields, and other open spaces provides a contribution of notably high leaf area values. On average, the mean value of development within each grid cell encompasses approximately 130 m², while the corresponding green surface measures about 46 m², and the average leaf area for the grid cells attains 160 m².

3.2. Green Ratio and Green Connection

The green ratio (

Figure 5-A) and the green connection (

Figure 5-B) generated through the distance matrix analysis reveal the impact of urban development on the fragmentation of natural habitats. The colours in the green ratio, ranging from dark green to dark grey in the spatial resistance, indicate that the grid units are becoming increasingly ineffective in restoring natural habitats or impeding the movement of organisms. Additionally, the grid cells in the green connections, differentiated by colours from yellow to dark purple, show a rise in connections with the surrounding cells. Both figures demonstrate that public gardens, urban gardening plots, sports fields, and cultivated areas play vital roles in fostering green connections. The heavily developed infrastructure and high-density buildings create significant gaps in the urban greenery stretching from the Limmat River to the Uetliberg foothills. Moreover, these intense developments, buildings, and street networks fragment the greenery in the built-up area into scattered and isolated small patches, diminishing its capacity for natural recolonisation.

3.3. Accessibility of Public Green Spaces

The accessibility of public green spaces is evaluated through the lens of two primary factors: the number of public green spaces located within an 800-metre walking distance (as illustrated in

Figure 6-B) and the aggregate area of those spaces (as depicted in

Figure 6-c). The gradient of colours, transitioning from dark to light green in both figures, signifies a decline in the availability of accessible public green spaces as well as a reduction in the cumulative area of these spaces. In general, the geographical distribution of the existing public green spaces guarantees that each household within the studied district can reach at least one public green space within an 800-metre radius. However, households situated in the central area and adjacent to the Limmat River have access to over ten public green spaces within the same distance, irrespective of the size of these areas. Moreover, taking into account the dimensions of each public green space, households located in the northeastern and southwestern regions are able to utilise significantly larger green spaces compared to those in other areas. Conversely, households in the central-western portion of the district are disadvantaged in both aspects, underscoring the necessity for the introduction of additional public green spaces in this area.

3.4. Interrelationships Among Measured Factors

In the process of compiling the measured factors as variables for the examination of their interrelationships, the results depicted in

Figure 7 reveal significant positive linear relationships among the factors pertaining to green surface, leaf area, and green connection at the α=0.001 level. This observation indicates a direct correlation whereby an increase in green surface positively influences both the enhancement of leaf area and the improvement of green connection within grid cells. Furthermore, the linear relationships between the green ratio and the factors of green surface, leaf area, and green connection are observed to be moderately positive, akin to the relationships between the two factors that pertain to the accessibility of public green spaces. Notably, the development factor reflects a negative correlation with most other factors; nonetheless, the correlation coefficient values remain from very weak to moderately high. Additionally, the two factors associated with public green space accessibility exhibit independence from others, as evidenced by the very low correlation coefficient values between them.

3.5. Green Feature Clustering

The distinctive feature of the comprehensive dataset comprising green attributes is characterised by high dimensionality, encompassing seven factors. The Elbow Method recommends that the optimal K value is around 10 to 15 (

Figure 8-A). The intricacy introduced by the seven dimensions resulted in a continuous increase in values across all Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) models, in conjunction with the escalation of the K value. Due to certain variables exhibiting strong linear correlations, the study implemented the PCA method to reduce the dataset's dimensionality, ultimately retaining four principal components that achieved cumulative variances of 90%. Nevertheless, this dimensionality reduction did not enhance the results from either the Elbow Method or the BIC, suggesting a similar K value range for clustering (

Figure 8-B).

In trials with varying combinations of the two parameters, the eps value and the minimum points of the cluster, the DBSCAN algorithm generated clusters of no more than six, with extremely uneven data points distributed in each cluster, implying the method is unsuitable for this dataset. The GMM algorithm based on the PCA reduced-dimensional dataset resulted in nine clusters applying the “VVE” model for the minimum request of BIC. Since the BIC algorithm verified that fifteen clusters with the VEV model performed better than in the other situations earlier (

Figure 8-B), the GMM was also forced to cluster the dataset into fifteen groups through the VEV model specifically.

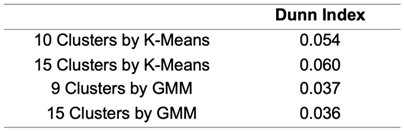

The four results of clustering—10 and 15 clusters derived from the K-Means, 9 clusters utilising the “VVE” model, and 15 clusters employing the “VEV” model as per the GMM technique—are illustrated in

Figure 9 for the district under study. In order to facilitate a comparative analysis of the differences among these clustering results, all clusters have been systematically organised in descending order based on average measurements of the development factor. The two outcomes from the K-Means adeptly differentiated between grid cells associated with buildings, grey surfaces, and green surfaces. A notable distinction between the 15-cluster K-Means outcome and the 10-cluster K-Means outcome is that the former delineated grid cells characterised by low development into three distinct groups, informed by their green surface, green ratio, and accessibility to public green spaces. In contrast, the GMM algorithm exhibited inferior performance relative to the K-Means method; both outcomes from the GMM faced challenges in effectively segregating buildings from green or grey surfaces and resulted in a dispersed distribution of points around green areas. This comparison was, moreover, verified by the Dunn-Index, as shown in

Table 2, where the 15-cluster K-Means outcome obtained a higher score than the rest, indicating a better compactness or goodness of clustering. The 10-cluster K-Means result received a slightly lower score.

Upon the division of each measured factor into ten distinct classes utilising the Jenks Natural Break methodology, the study employed the average values of these classes to accurately represent the characteristics of the fifteen clusters as identified by the K-Means Clustering method.

Figure 10 illustrates that Clusters 1 and 2 are predominantly composed of densely constructed areas within the district, characterised by a minimal presence of green surfaces and leaf areas. Households located within these two clusters have access to over five public green spaces; however, these areas are relatively small in size. Clusters 3 and 4 encompass moderately constructed areas, distinguished by their respective access to green spaces. The former benefits from commendable access to extensive public parks, despite having limited private green surfaces. In contrast, the latter contains significant private green surfaces within each grid cell, though it offers lesser access to public green spaces. While not extensively developed, the grid cells within Clusters 5 to 7 exhibit restricted green surfaces and leaf areas, indicating a predominance of grey surfaces. The regions encompassed within Clusters 8 to 11 feature a majority of surfaces adorned with vegetation, thus facilitating green connections within the constructed environment. Clusters 12 to 15 comprise green surfaces that fulfil various ecological functions, with distinctions arising from the types of vegetation present and their relational dynamics with other public green spaces.

Based on the identified clusters and their specific combinations, the studied area was systematically divided into five principal segments (see

Figure 11). The central areas, classified as the first zone, extend vertically from north to south and are characterised by Clusters 1, 7, 8, and 13. The second zone, positioned in the middle of the district, elongates horizontally along the railway lines from east to west, comprising Clusters 1, 2, 4, 5, and 9. In between the studied district and its eastern neighbouring region lies the third zone featured by Clusters 2, 4, 5, 9 and 12. Two aggregations of Clusters 3, 10, 11, and 14, which constitute the third zone, are located in proximity to the Limmat River and the foothills of the mountains. The fourth zone, encompassing Clusters 6, 12, and 15, is situated in the peripheral region of the district.

The characteristics of each zone suggest potential strategies for land development. Zones 1, 2 and 3, being significantly densely constructed regions, face disadvantages due to their limited leaf areas and the inadequate portions of accessible public green spaces. Consequently, proposed improvements prioritise the planting of additional trees and the expansion of public green spaces. As the majority of plots have been utilised for development, establishing community gardens and green spaces within these developments may alleviate the congestion experienced in public parks and gardens. Additionally, integrating structures for cultivating greenery would enhance aspects such as the green ratio and connectivity. The residential environment in Zone 4 is exemplary in terms of the availability of green spaces; hence, further investment in greenery may not yield substantial benefits for this area. Nonetheless, this zone may serve as a resource for future development due to its relatively lower building density, assisting in alleviating the pressures of rising population density. Finally, Zone 5 functions as a buffer between urbanised areas and the natural environment.

4. Application in Lindenplatz Subsite

The study employed the 400-meter service catchment area of Lindenplatz, encompassing an area of 0.5 km², located at the centre of the district, as a representative subsite for the optimisation of green infrastructure. This subsite comprises a diverse array of structures, including residential buildings, shopping centres, office buildings, educational institutions, and places of worship. It serves as a crucial cultural and commercial hub for the entire district.

As illustrated in

Figure 12-A, this subsite case traverses Zones 1 and 2 and is deemed appropriate for the general improvement suggestions proposed in the preceding session. A detailed examination of the subsite is provided in

Figure 12-B. In conjunction with the densely developed areas (Cluster 1 and Cluster 2) within the subsite, the upper half of the site is predominantly characterised by streets and other grey surfaces (Clusters 4 through 6), interspersed with smaller green patches (Clusters 8 and 9). In contrast, the lower half of the site reveals an increase in the prevalence of green spaces displaying superior features (Clusters 10 and 11), which connect to four substantial patches (Clusters 12, 13, and 14). In light of the aforementioned circumstances, the comparatively intensive developments and buildings present significant obstacles to the provision of additional green surfaces and the connectivity of green spaces at ground level. The strategies for optimising the green infrastructure of the site emphasise the enhancement of green spaces and leaf areas by utilising existing building structures for vegetation, such as roof gardens and green facades.

Given that grid size can significantly affect the analysis of geospatial information and the interpretation of results, determining the appropriate grid size for both data analysis and visualisation has emerged as a primary challenge of this study. As an initial investigation aimed at evaluating the feasibility of the analytical process, a rectangular grid measuring 30 meters by 30 meters was utilised to generate a comparatively smaller dataset. The entire analytical procedure, which includes the measurement of green factors and subsequent clustering, concluded with the identification of ten clusters, as illustrated in

Figure 12-C. The findings indicate a more abstract pattern closely associated with the ten clusters identified using the K-Means algorithm, although the profiles of buildings, streets, and other spaces appear somewhat obscured. At the district scale, this outcome illustrates a comprehensive pattern of land features, highlighting the continuous patches of densely developed areas that benefit from their proximity to a wealth of public green spaces in the city centre, alongside the relatively homogeneous low-density areas interspersed with green surfaces. When examining the neighbourhood scale, with Lindenplatz and its 400-meter service catchment area as an illustrative example (

Figure 12-D), the clustering based on a 30-meter grid underscores the interpretation of two primary components: the upper section characterised by dense development and the lower section showcasing green surfaces. Variations in clustering outcomes between the 10-meter and 30-meter grids suggest that different grid sizes are suited to various scales of analysis and their corresponding objectives. A larger grid size, manifesting in continuous patches, facilitates decision-making strategies at the city scale, while a smaller grid size allows for a more thorough investigation at the neighbourhood scale.

5. Discussion: Study Limitations and Further Developments

The objective of the study was to synthesise the analysis of urban green infrastructure with the intention of generating land feature patterns that would inform strategic recommendations aimed at enhancing the provision of local urban green spaces, grounded in a comprehensive understanding at the district scale. In alignment with this objective, the study examined green factors from both social and ecosystem perspectives within a 10-meter grid, clustering the grid cells into fifteen groups characterised by distinctive land features. The findings revealed five zones within the studied district and provided insights into specific urban green strategies customised for each zone. Throughout the entire examination and integration process, some issues related to data collection and analytical methods emerged as significant considerations for future development.

5.1. Clustering Process

Stemmed from the fact that both the K-Means and GMM algorithms cluster a dataset from the random initialisation of centroids, one of the key challenges encountered during the clustering process was the variability in cluster assignments across different runs, which led to some different cluster configurations at the beginning. The study employed the alternative technique K-Means++ to stabilise the clustering by improving centroid initialisation. However, variability still remains a concern, especially when the dataset contains considerable overlapping points within a high-dimensional structure. Similarly, the GMM method, investigating the probabilities of each data point belonging to a particular cluster, is sensitive to the initial parameters and results in different cluster assignments between runs. The Expectation-Maximisation (EM) algorithm used in the GMM method can converge to varied local optima depending on initialisation and cause the reduction of stability. This challenge required multiple runs of the algorithm and strategies of carefully selecting the initialisation to obtain better consistency.

In addition to the nature of the algorithms, some other factors can also influence the stability of the cluster assignments, for instance, the number of clusters (K value) and the size and shape of the dataset. Theoretically, clustering a larger dataset through the K-Means algorithm with any K values can achieve a more stable result than clustering a smaller dataset; on the other side, datasets with more dimensions and unsymmetric structure lead to the increase of instability of clustering (von Luxburg, 2010). The intricacy of these influential factors in the algorithm leads to the consideration of a better clustering procedure to enhance the robustness of the outcomes for future deep learning and further application extending to different urban contexts.

5.2. Contribution of Green Factors to the Clustering Process

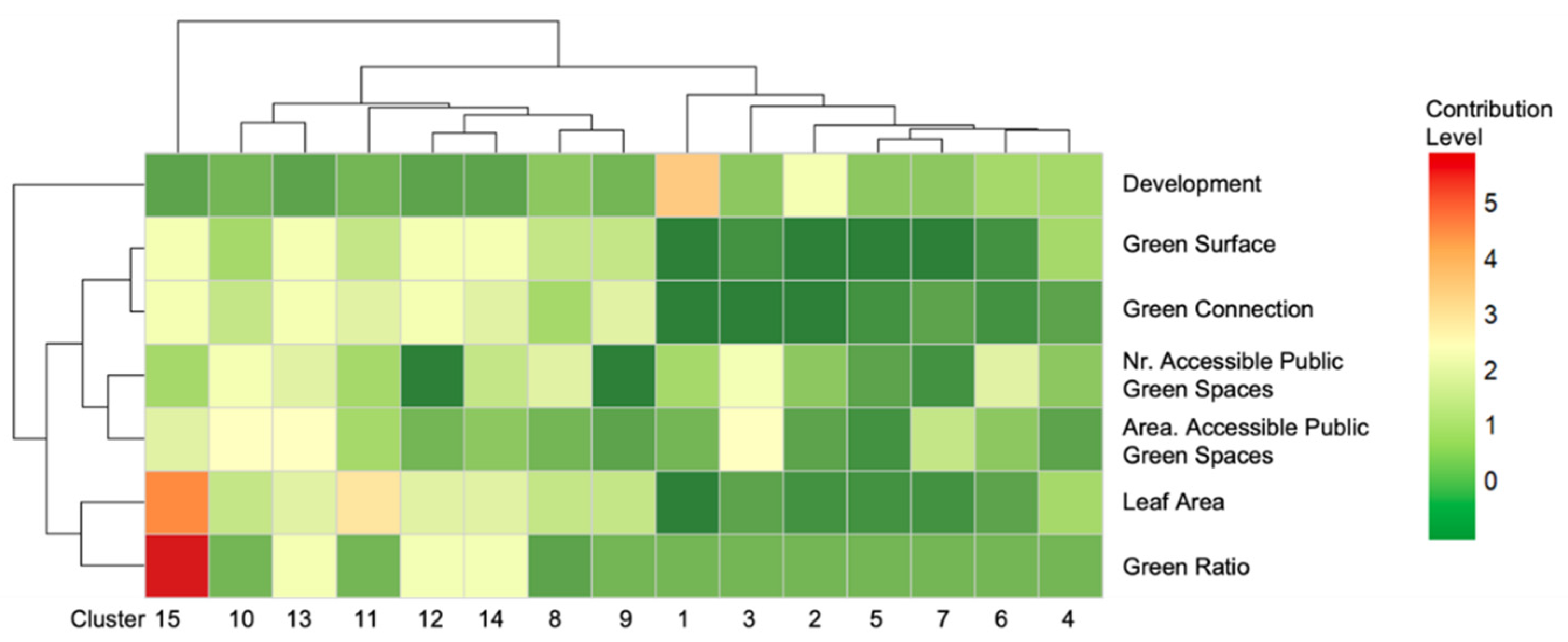

In the process of clustering, each standardised measured factor contributed uniquely to the formation of clusters (see

Figure 13). The primary observation indicates that, with the exception of the development factor, the measured factors predominantly influenced Clusters 8 to 15, contributing significantly to their defining characteristics compared to the other clusters. Cluster 15 is particularly notable due to the exceptionally high contributions of the green ratio and leaf area. This variation in contributions also reflects the hierarchy among the measured factors as well as among the fifteen clusters throughout the clustering process, which may assist in facilitating spatial ranking as objective weights.

5.3. Green Ratio and Connection

Research on landscape resistance and connectivity has garnered increasing recognition as significant parameters influencing long-term biodiversity conservation. Nevertheless, a universally accepted methodology for systematically quantifying and modelling connectivity and resistance remains elusive [

12,

47]. This challenge arises from various factors, including the difficulties associated with observing animal movement, behavioural variations linked to specific species, and the fluctuations of environmental variables. This study, which does not identify the specific organism species present in the district, concentrated on the propensity of grid cells from two perspectives: leaf areas representing both the green surfaces on the ground and the tree canopies that facilitate animal movement and gene flow, alongside the development characterised by impervious surfaces and buildings that perform as obstruction to movement continuity. To a certain degree, the comparison between these two perspectives, denoted by the green ratio, overlooks the differentiation between “isolation-by-distance” and “isolation-by-barrier”, as articulated by Zeller et al [

66]. For example, grid cells exhibiting an identical low green ratio may display either extensive grey surfaces coupled with minimal green surfaces on the ground (such as streets and roads) or consist of towering structures and trees (like high-rise buildings). However, the former scenario hinders movement, whereas the latter situation presents obstacles to mobility. The accuracy of this assessment could potentially be enhanced through the incorporation of the Digital Elevation Model (DEM) along with the integration of green surfaces and tree canopies.

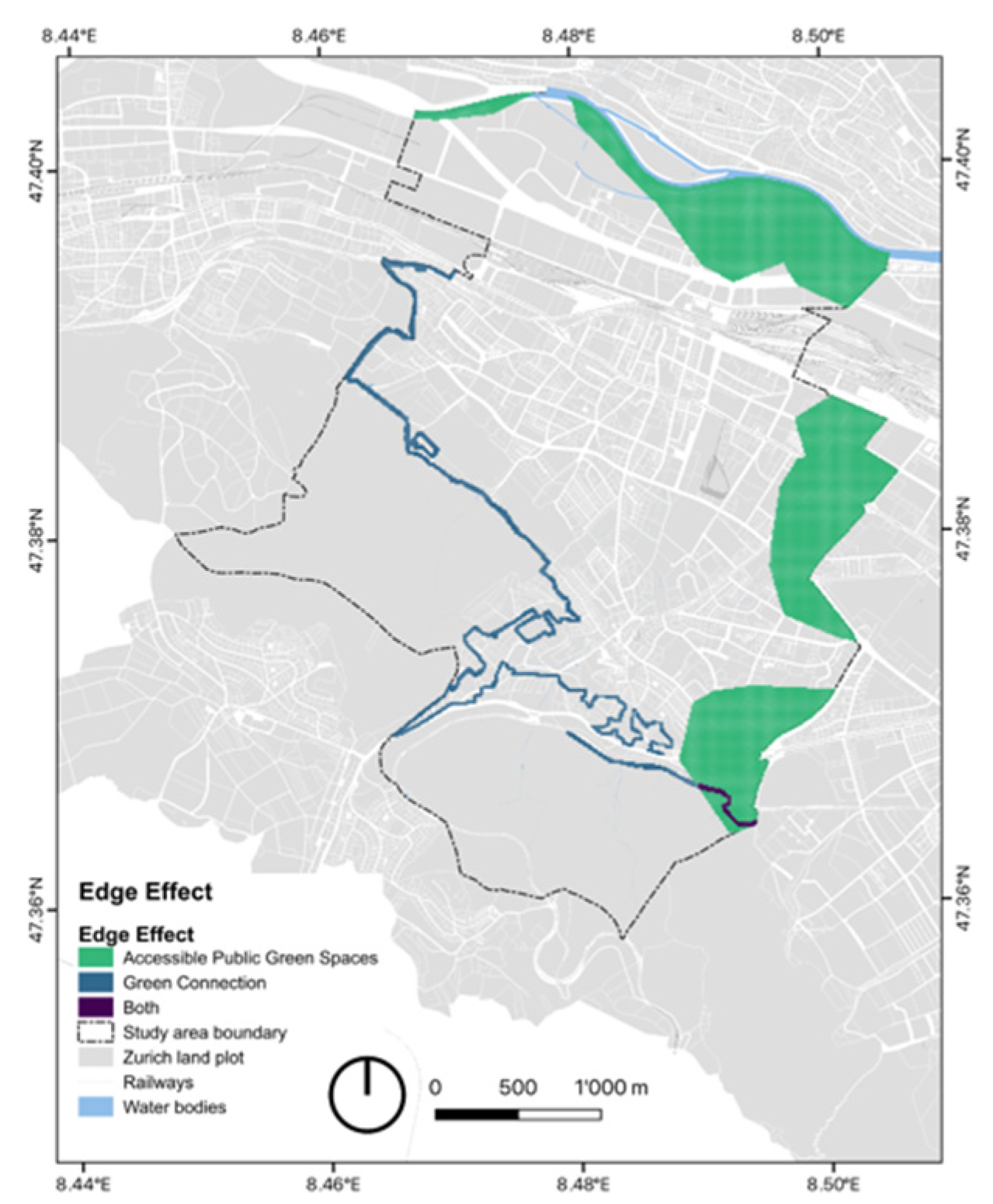

5.4. Geo-Boundary and Edge Effect

The research employed the administrative boundary of the Altstetten-Albisrieden district to generate grid cells and organise geo-information, resulting in edge effects in certain measurements of green factors (

Figure 14). These effects arise from the geographic distribution or spatial occurrences within the district that may extend beyond its boundaries [

16,

60,

65], particularly concerning green connections and the accessibility of public green spaces. In the analysis of the green connections, the predominant bias was identified in the cells adjacent to the western and southern boundaries, extending from the agricultural fields to the closed forest along the Uetliberg foothills, where the links to forests and fields were not incorporated. Certain public green spaces on the opposite riverbank of the Limmat are also accessible to residents in the northern part of the district; however, owing to the already elevated level of access to public green spaces in terms of both quantity and total area, this addition has minimal effects on the clustering results. City parks and gardens situated within 800 meters to the east of the district may enhance the green attributes of the grid cells in the eastern part of the district regarding the availability of accessible public green spaces; nonetheless, in light of the contribution of each variable to the clusters, such impact may not be substantial.

The pressing concern regarding edge effects in the current study necessitates additional contemplation regarding boundary values and performance in the context of urban spatial phenomena. The continuous rise in the influx of individuals, transportation, and various materials has undermined traditional notions of boundaries, consequently complicating the comprehension of both local and global attributes. Defining a finite bounded area for spatial analysis may serve as a valuable supplementary aspect to the study.

6. Conclusions

The significance of urban green infrastructure and its performance in the context of rapid urban development from both social and environmental perspectives has garnered increasing recognition. Nonetheless, enhancing the provision of urban green spaces within existing urban environments is imperative for effective urban planning and design. This study undertook a systematic examination of the availability and accessibility of green infrastructure in the Altstetten-Albisrieden district of Zurich, employing grid-based analysis and clustering algorithms to generate spatial patterns that reflect unique land characteristics. This spatial analytical approach culminated in strategic recommendations that underscore the necessity of community green spaces to address the deficit of public gardens and parks, as well as to augment vegetation and plant cover on existing structures, thereby enhancing leaf area and improving connectivity between green patches and natural habitats in densely populated areas. These recommendations were informed by local land characteristics and also incorporated a comprehensive understanding of the overall situation at the district level.

As a pilot study for integrating such spatial analysis, the metrics utilised can be further refined by enhancing data collection methods to mitigate edge effects, acquiring more precise information regarding ecosystems, and incorporating qualitative studies to substantiate accessibility and perceptions of public green spaces. The challenges posed by the high-dimensional dataset indicate a need for more sophisticated clustering methodologies to minimise randomness, thereby allowing the expansion of this approach to a broader scale. Regardless, this study establishes a robust foundation for understanding urban green infrastructure through the integration of multiple green factors based on their interrelations, thus encouraging future interdisciplinary urban and spatial research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.J.; Methodology, Y.J.; Software, Y.J.; Validation, Y.J.; Formal Analysis, Y.J.; Investigation, Y.J.; Resources, Y.J.; Data Curation, Y.J.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Y.J.; Writing – Review & Editing, Y.J.; Visualization, Y.J.; Supervision, S.M.; Project Administration, Y.J.; Funding Acquisition, S.M.

Funding

This research was conducted at the Future Cities Lab Global at ETH Zurich. Future Cities Lab Global is supported and funded by the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore under its Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise (CREATE) programme and ETH Zurich (ETHZ), with additional contributions from the National University of Singapore (NUS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore and the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD).

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Roderic Günter and Caspar Trüb, who worked as research assistants in the Dense and Green Cities module. Their cooperation, kind support and insightful feedback throughout the research period contributed extraordinarily to the improvement of the paper’s quality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BIC |

Bayesian Information Criterion |

| DBSCAN |

Density-Based Clustering method |

| DEM |

Digital Elevation Model |

| DHP |

Digital Hemispherical Photography |

| GMM |

Gaussian Mixture Model |

| K-Means |

K-Means clustering method |

| LAI |

Leaf Area Index |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| TRAC |

Tracing Radiation and Architecture of Canopies |

| NParks |

Singapore National Parks Abroad |

References

- Abebe, M. T. , & Megento, T. L. Urban green space development using GIS-based multi-criteria analysis in Addis Ababa metropolis. Applied Geomatics 2017, 9, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas. Grid-Based Analysis. https://atlas.co/glossary/grid-based-analysis/.

- Atzberger, C. , Darvishzadeh, R., Immitzer, M., Schlerf, M., Skidmore, A., & Le Maire, G. Comparative analysis of different retrieval methods for mapping grassland leaf area index using airborne imaging spectroscopy. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2015, 43, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, D. N., Dunford, R., Gomez-Baggrthun, E., Harrison, P. A., Jacobs, S., Kelemen, E., & Martin-Lopez, B. Integrated assessment and valuation of ecosystem services: Guidelines and experiences (Collaborative Project FP7 Environment: OpenNESS. Operationalisation of Natural Capital and Ecosystem Services: From Concepts to Real-World Applications) [[Pu] after publication of OpenNESS Special Issue in Ecosystem Services]. Finnish Environment Institute (SYKE) 2017. https://oppla.eu/sites/default/files/uploads/openness-d33-44integratedassessmentvaluationofesfinal2.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Bousquet, M. , Kuller, M., Lacroix, S., & Vanrolleghem, P. A. A critical review of multicriteria decision analysis practices in planning of urban green spaces and nature-based solutions. Blue-Green Systems 2023, 5, 200–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D. E. , Buyung-Ali, L., Knight, T. M., & Pullin, A. S. Urban greening to cool towns and cities: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Landscape and Urban Planning 2010, 97, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, C. A. , & Pickle, L. Evaluation of Methods for Classifying Epidemiological Data on Choropleth Maps in Series. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 2002, 92, 662–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černý, J. , Haninec, P., & Pokorný, R. Leaf area index estimated by direct, semi-direct, and indirect methods in European beech and sycamore maple stands. Journal of Forestry Research 2020, 31, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. M. , & Black, T. A. Defining leaf area index for non-flat leaves. Plant, Cell & Environment 1992, 15, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chianucci, F. , Macfarlane, C., Pisek, J., Cutini, A., & Casa, R. Estimation of foliage clumping from the LAI-2000 Plant Canopy Analyzer: Effect of view caps. Trees 2015, 29, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadvand, P. , Bartoll, X., Basagaña, X., Dalmau-Bueno, A., Martinez, D., Ambros, A., Cirach, M., Triguero-Mas, M., Gascon, M., Borrell, C., & Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. Green spaces and General Health: Roles of mental health status, social support, and physical activity. Environment International 2016, 91, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, M. F. , Cushman, S. A., Machado, R. B., & De Marco Júnior, P. Landscape connectivity modeling from the perspective of animal dispersal. Landscape Ecology 2020, 35, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N. , Yang, X., Cai, H., & Xu, F. Research on Grid Size Suitability of Gridded Population Distribution in Urban Area: A Case Study in Urban Area of Xuanzhou District, China. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0170830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y., Li, G., An, D., & Luo, W. Simulation model for predicting the effects of substrate water potential onleaf area of cut lily. Transations of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering(TCSAE) 2012, 28, 191–197.

- Fang, H. , Baret, F., Plummer, S., & Schaepman-Strub, G. An Overview of Global Leaf Area Index (LAI): Methods, Products, Validation, and Applications. Reviews of Geophysics 2019, 57, 739–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F. , Kihal, W., Le Meur, N., Souris, M., & Deguen, S. Does the edge effect impact on the measure of spatial accessibility to healthcare providers? International Journal of Health Geographics 2017, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelan, E. GIS-based multi-criteria analysis for sustainable urban green spaces planning in emerging towns of Ethiopia: The case of Sululta town. Environmental Systems Research 2021, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X. , Yang, X., Chen, M., Li, M., & Wang, Y. A model with leaf area index and apple size parameters for 2.4 GHz radio propagation in apple orchards. Precision Agriculture 2015, 16, 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T. , Mitchell, R., De Vries, S., & Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annual Review of Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, M., Yusoff, M. M., & Shafie, A. Assessing the role of urban green spaces for human well-being: A systematic review. GeoJournal 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y. , Özdoğan, M., Zipper, S., Román, M., Walker, J., Hong, S., Marshall, M., Magliulo, V., Moreno, J., Alonso, L., Miyata, A., Kimball, B., & Loheide, S. How Universal Is the Relationship between Remotely Sensed Vegetation Indices and Crop Leaf Area Index? A Global Assessment. Remote Sensing 2016, 8, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, C. , & Büyüktaş, D. Variation of The Leaf Area Index of Some Vegetables Commonly Grown in Greenhouse Conditions with Cultural Practices. Horticultural Studies 2021, 38, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłopotek, M. A. Are Easy Data Easy (for K-Means) (Version 1), 2023. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A., Geetha, P., Shashank, A., & Rajendrakumar, S. Review on Grid-based system and applied GIS in Natural Resource management: A Comparative Analysis. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ladefoged, K. Transpiration of Forest Trees in Closed Stands. Physiologia Plantarum 1963, 16, 378–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langemeyer, J. , Gómez-Baggethun, E., Haase, D., Scheuer, S., & Elmqvist, T. Bridging the gap between ecosystem service assessments and land-use planning through Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA). Environmental Science & Policy 2016, 62, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepczyk, C. A. , Aronson, M. F. J., Evans, K. L., Goddard, M. A., Lerman, S. B., & MacIvor, J. S. Biodiversity in the City: Fundamental Questions for Understanding the Ecology of Urban Green Spaces for Biodiversity Conservation. BioScience 2017, 67, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. , Guo, P., Liu, H., Fan, P., Zeng, P., Liu, X., Feng, C., Wang, W., & Yang, F. Gradient Boosting Estimation of the Leaf Area Index of Apple Orchards in UAV Remote Sensing. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S. , Liu, Y., Du, M., Gao, S., Wang, P., & Liu, X. The Influence of Spatial Grid Division on the Layout Analysis of Urban Functional Areas. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2021, 10, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manetti, M. C., Fabbio, G., Giannini, T., Gugliotta, O. I., & Gudi, G. Old-growth forests: Report from the plots established by Aldo Pavari. L’Italia Forestale e Montana 2010, 751–764. [CrossRef]

- Markevych, I. , Schoierer, J., Hartig, T., Chudnovsky, A., Hystad, P., Dzhambov, A. M., De Vries, S., Triguero-Mas, M., Brauer, M., Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Lupp, G., Richardson, E. A., Astell-Burt, T., Dimitrova, D., Feng, X., Sadeh, M., Standl, M., Heinrich, J., & Fuertes, E. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: Theoretical and methodological guidance. Environmental Research 2017, 158, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarini, L. , Lorenzo, G. A., & Fernando, V. Leaf Area Index, Water Index, and Red: Far RedRatio Calculated by Spectral Reflectance and its Relation to Plant Architecture and Cut Rose Production. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 2006, 131, 313–319. [Google Scholar]

- Montes, F., Pita, P., Rubio, A., & Cañellas, I. Leaf area index estimation in mountain even-aged Pinus silvestris L. stands from hemispherical photographs. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2007, 145(3–4), 215–228. [CrossRef]

- Mora, M. , Avila, F., Carrasco-Benavides, M., Maldonado, G., Olguín-Cáceres, J., & Fuentes, S. Automated computation of leaf area index from fruit trees using improved image processing algorithms applied to canopy cover digital photograpies. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2016, 123, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, M. , Crisci, A., Guerri, G., Messeri, A., Congedo, L., & Munafò, M. Surface urban heat islands in Italian metropolitan cities: Tree cover and impervious surface influences. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 751, 142334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muluneh, M. G. , & Worku, B. B. Contributions of urban green spaces for climate change mitigation and biodiversity conservation in Dessie city, Northeastern Ethiopia. Urban Climate 2022, 46, 101294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardini, A. , Raimondo, F., Scimone, M., & Salleo, S. Impact of the leaf miner Cameraria ohridella on whole-plant photosynthetic productivity of Aesculus hippocastanum: Insights from a model. Trees 2004, 18, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K. , Ito, M., Kusaba, Y., Saito, M., Mori, M., Yamane, S., Iwao, T., Tada, I., Yamazaki, T., & Kitano, M. Estimation of the optimal leaf area index (LAI) of an eggplant canopy based on the relationship between the nighttime respiration and daytime photosynthesis of the lowermost leaves. Scientia Horticulturae 2023, 307, 111525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G. G. Tamm review: Leaf Area Index (LAI) is both a determinant and a consequence of important processes in vegetation canopies. Forest Ecology and Management 2020, 477, 118496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry-Thomson, R. Habitat fragmentation: Why it’s an issue for nature & climate. 2024, Kent Wildlife Trust. https://www.kentwildlifetrust.org.uk/blog/habitat-fragmentation-impacts#:~:text=Habitat%20fragmentation%20occurs%20when%20larger,and%20the%20development%20of%20infrastructure.

- Paudel, S., & States, S. L. Urban green spaces and sustainability: Exploring the ecosystem services and disservices of grassy lawns versus floral meadows. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2023, 84, 127932. [CrossRef]

- Peper, P. , & McPherson, E. G. Comparison of Five Methods for Estimating Leaf Area Index of Open-Grown Deciduous Trees. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry 1998, 24, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, A. , Jiang, Y., Menz, S., & Ricci, L. Green Cities: Utopia or Reality? Evidence from Zurich, Switzerland. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petritan, I. C. , Mihăilă, V.-V., Bragă, C. I., Boura, M., Vasile, D., & Petritan, A. M. Litterfall production and leaf area index in a virgin European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) – Silver fir (Abies alba Mill.) forest. Dendrobiology 2020, 83, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primack, R. B., & Morrison, R. A. Extinction, Causes of. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity 2013 (pp. 401–412). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Rees, A. R. Dry-Matter Production by Field-Grown Tulips. Journal of Horticultural Science 1966, 41, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, D. A., Ryan, S. J., Beier, P., Cushman, S. A., Dieffenbach, F., Epps, C. W., Gerber, L. R., Hartter, J., Jenness, J. S., Kintsch, J., Merenlender, A. M., Perkl, R. M., Preziosi, D. V., & Trombulak, S. C. The role of landscape connectivity in planning and implementing conservation and restoration priorities. Ecology 2012, 16(Fall), 1–20.

- Schoier, G., & Borruso, G. On Model Based Clustering in a Spatial Data Mining Context. In B. Murgante, S. Misra, M. Carlini, C. M. Torre, H.-Q. Nguyen, D. Taniar, B. O. Apduhan, & O. Gervasi (Eds.), Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2013 (Vol. 7974, pp. 375–388). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Scott Shaobing Chen, & Gopalakrishnan, P. S. Clustering via the Bayesian information criterion with applications in speech recognition. Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, ICASSP ’98 (Cat. No.98CH36181), 2, 645–648. [CrossRef]

- Šrámek, M. , & Čermák, J. The vertical leaf distribution of Ulmus laevis Pall. Trees 2012, 26, 1781–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinley, D. , & Brusco, M. J. Choosing the number of clusters in Κ-means clustering. Psychological Methods 2011, 16, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterba, H. , Dirnberger, G., & Ritter, T. Vertical Distribution of Leaf Area of European Larch (Larix decidua Mill.) and Norway Spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) in Pure and Mixed Stands. Forests 2019, 10, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research. Insights into the Swiss Forest [Online post]. 2011. https://www.lfi.ch/media/documents/publikationen/posterserie_LFI3_A4-en.pdf.

- Taylor, P. D. , Fahrig, L., Henein, K., & Merriam, G. Connectivity Is a Vital Element of Landscape Structure. Oikos 1993, 68, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharakan, P. J., Volk, T. A., Nowak, C. A., & Ofezu, G. J. Assessment of Canopy Structure, Light Interception, and Light-use Efficiency of First Year Regrowth of Shrub Willow (Salix sp.). BioEnergy Research 2008, 1(3–4), 229–238. [CrossRef]

- Thimonier, A. , Sedivy, I., & Schleppi, P. Estimating leaf area index in different types of mature forest stands in Switzerland: A comparison of methods. European Journal of Forest Research 2010, 129, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokár, F. Aboveground biomass production in black walnut (juglans nigra l.) Monocultures in dependence on leaf area index (lai) and climatic conditions. Ekologia 2009, 28, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, A. E. , Maas, J., Verheij, R. A., & Groenewegen, P. P. Green space as a buffer between stressful life events and health. Social Science & Medicine 2010, 70, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Ploeg, A. , & Heuvelink, E. The influence of temperature on growth and development of chrysanthemum cultivars. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2006, 81, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal Rodeiro, C. L. , & Lawson, A. B. An evaluation of the edge effects in disease map modelling. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 2005, 49, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Luxburg, U. Clustering Stability: An Overview. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Wang’ombe, G. The Impact of Urban Green Spaces on Community Health and Well-being. International Journal of Arts, Recreation and Sports 2024, 3, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S. , Wang, S., Dong, R., & Dong, X. Indexes of Tree Structure of Cylindrical Pear Orchards at the Sapling Stage. Agricultural Biotechnology; Cranston 2019, 8, 145–146. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. , & Rui, J. The mitigating effect of green Space’s spatial and temporal patterns on the urban heat island in the context of urban densification: A case study of Xi’an. Sustainable Cities and Society 2024, 117, 105974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, I. (2009). Edge Effects. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography 2009 (pp. 381–388). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Zeller, K. A. , McGarigal, K., & Whiteley, A. R. Estimating landscape resistance to movement: A review. Landscape Ecology 2012, 27, 777–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F. , & Qian, H. A comprehensive review of the environmental benefits of urban green spaces. Environmental Research 2024, 252, 118837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. , Liu, Y., Zhou, S., Cheng, Y., & Zhao, B. Do various dimensions of exposure metrics affect biopsychosocial pathways linking green spaces to mental health? A cross-sectional study in Nanjing, China. Landscape and Urban Planning 2022, 226, 104494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Methodological framework of the study.

Figure 1.

Methodological framework of the study.

Figure 2.

Location of the studied district, Altstetten-Albisrieden, Zurich.

Figure 2.

Location of the studied district, Altstetten-Albisrieden, Zurich.

Figure 3.

6.5. Accessibility of public green spaces.

Figure 3.

6.5. Accessibility of public green spaces.

Figure 4.

Development intensity (A), green surface (B) and leaf area (C) measured in a 10-meter by 10-meter rectangle grid across the studied area.

Figure 4.

Development intensity (A), green surface (B) and leaf area (C) measured in a 10-meter by 10-meter rectangle grid across the studied area.

Figure 5.

Green ratio (A) and green connection (B) measured in a 10-meter by 10-meter rectangle grid across the studied area.

Figure 5.

Green ratio (A) and green connection (B) measured in a 10-meter by 10-meter rectangle grid across the studied area.

Figure 6.

The allocation of public green space throughout the studied district (A), the number of accessible public green spaces (B) and their total areas (C) within an 800-metre walking distance in the district.

Figure 6.

The allocation of public green space throughout the studied district (A), the number of accessible public green spaces (B) and their total areas (C) within an 800-metre walking distance in the district.

Figure 7.

Correlation coefficient analysis between seven measured factors.

Figure 7.

Correlation coefficient analysis between seven measured factors.

Figure 8.

Elbow method and BIC analysing the optimal K value for K-Means Clustering algorithm: with all seven factors (A) and with retained four components after the PCA analysis(B).

Figure 8.

Elbow method and BIC analysing the optimal K value for K-Means Clustering algorithm: with all seven factors (A) and with retained four components after the PCA analysis(B).

Figure 9.

Four clustering results projected into the studied district map: Ten clusters by K-Means (A), Fifteen clusters by K-Means (B), nine clusters through the “VVE” model in GMM and fifteen clusters through the “VEV” model in GMM.

Figure 9.

Four clustering results projected into the studied district map: Ten clusters by K-Means (A), Fifteen clusters by K-Means (B), nine clusters through the “VVE” model in GMM and fifteen clusters through the “VEV” model in GMM.

Figure 10.

Fifteen clusters by the K-Means Clustering methods in the studied district and the seven-dimensional radar charts demonstrating the average characteristics of each cluster.

Figure 10.

Fifteen clusters by the K-Means Clustering methods in the studied district and the seven-dimensional radar charts demonstrating the average characteristics of each cluster.

Figure 11.

Seven-dimensional characteristics of the four parts in the studied area.

Figure 11.

Seven-dimensional characteristics of the four parts in the studied area.

Figure 12.

Lindenplatz subsite in the studied district (A), its green clusters by K-Means Clustering methods in a 10-metre rectangle grid (B) and a 30-metre rectangle grid (D), as well as the ten green clusters throughout the studied district within the 30-metre rectangle grid (C).

Figure 12.

Lindenplatz subsite in the studied district (A), its green clusters by K-Means Clustering methods in a 10-metre rectangle grid (B) and a 30-metre rectangle grid (D), as well as the ten green clusters throughout the studied district within the 30-metre rectangle grid (C).

Figure 13.

Contributions of each green factor to the clusters, with the colour varying from red to green indicating the contribution from high (level 5) to low (level 0).

Figure 13.

Contributions of each green factor to the clusters, with the colour varying from red to green indicating the contribution from high (level 5) to low (level 0).

Figure 14.

Edge effects in the studied areas highlight three possible impacts, as differentiated by the colours, when using administrative boundaries to limit the original data collection.

Figure 14.

Edge effects in the studied areas highlight three possible impacts, as differentiated by the colours, when using administrative boundaries to limit the original data collection.

Table 1.

Main tree species of the studied area 1 and the leaf area index (LAI) values used in this study.

Table 1.

Main tree species of the studied area 1 and the leaf area index (LAI) values used in this study.

| CATEGORY |

SPECIES |

LEAF AREA INDEX (LAI) |

| TREE |

Spruce (Picea) |

7.5 2

|

| Fir (Abies) |

5.1 3

|

| Larch (Larix) |

3.6 4

|

| Pine (Pinus) |

5.7 5

|

| Beech (Fagus) |

5.5 6

|

| Maple (Acer) |

4.0 7

|

| Ash (Fraxinus) |

2.8 8

|

| Oak (Quercus) |

4.7 9

|

| Chestnut (Castanea) |

2.5 10

|

| Tilia (Tilia) |

5.3 11

|

| Apple tree (Malus) |

3.0 12

|

| Cherry tree (Prunus) |

4.8 13

|

| Pear tree (Pyrus) |

1.7 14

|

| Mulberry (Morus) |

3.1 15

|

| Walnut (Juglans) |

6.3 16

|

| Willow (Salix) |

3.3 17

|

| Broadleaf |

4.0 18

|

| Conifer |

5.2 19

|

| URBAN FARMING / GARDENING FIELDS |

3.2 20

|

| INTENSIVE CULTIVATED FIELDS |

2.9 |

| MEADOW |

2.9 |

Table 2.

Dunn Index of four clustering results. The higher the index value and the better the clustering result.

Table 2.

Dunn Index of four clustering results. The higher the index value and the better the clustering result.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).