Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

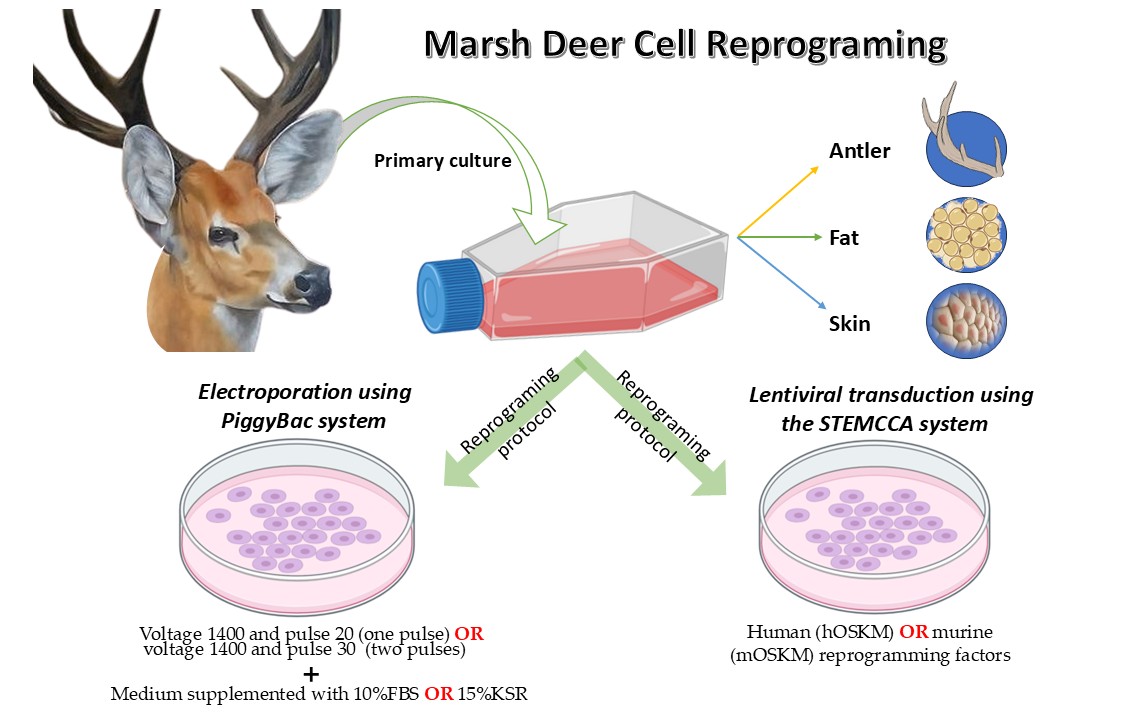

2. Materials and Methods

Animal Biopsies

Isolation of Somatic Cells

Pluripotency Induction

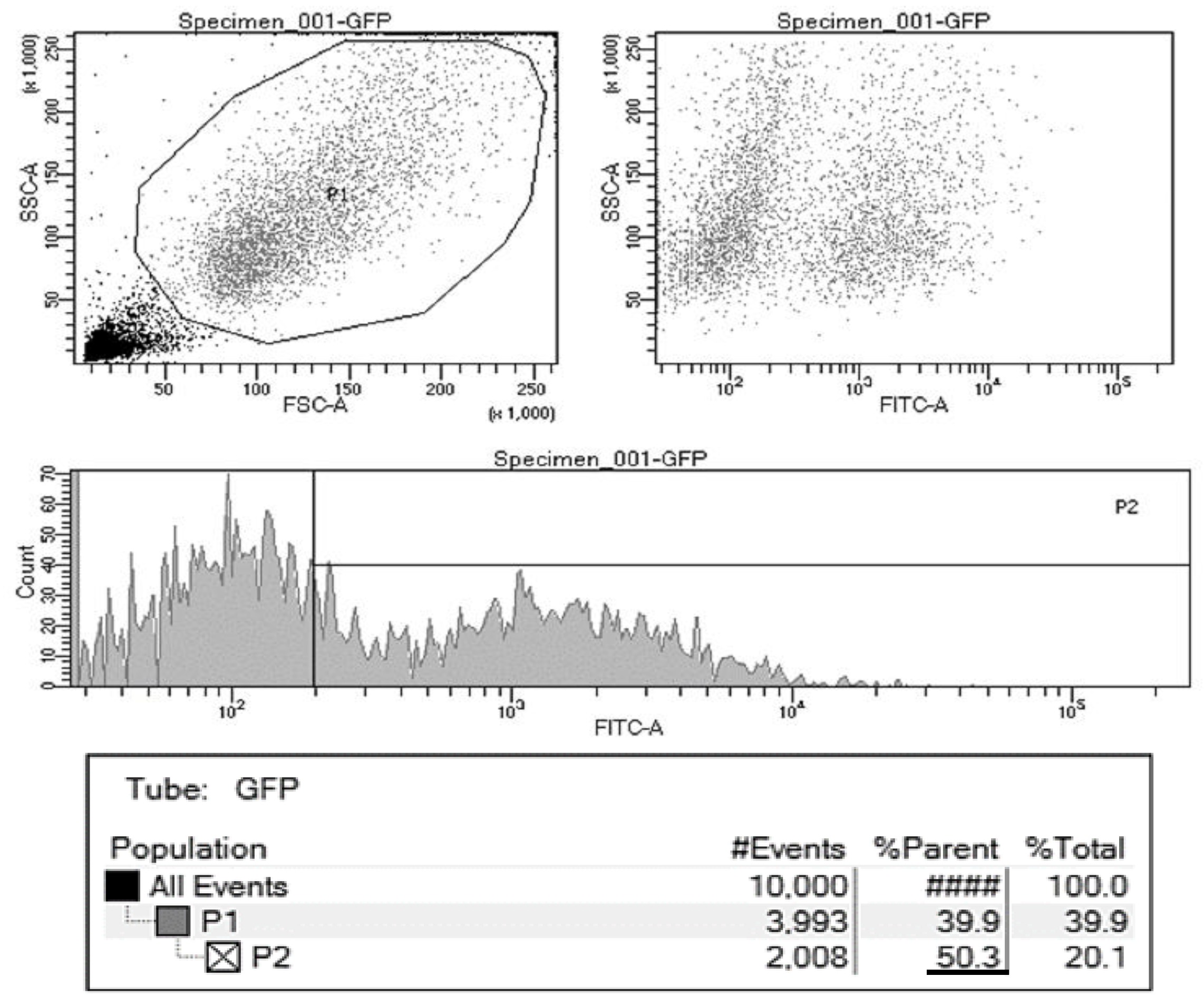

Electroporation Using the PiggyBac System

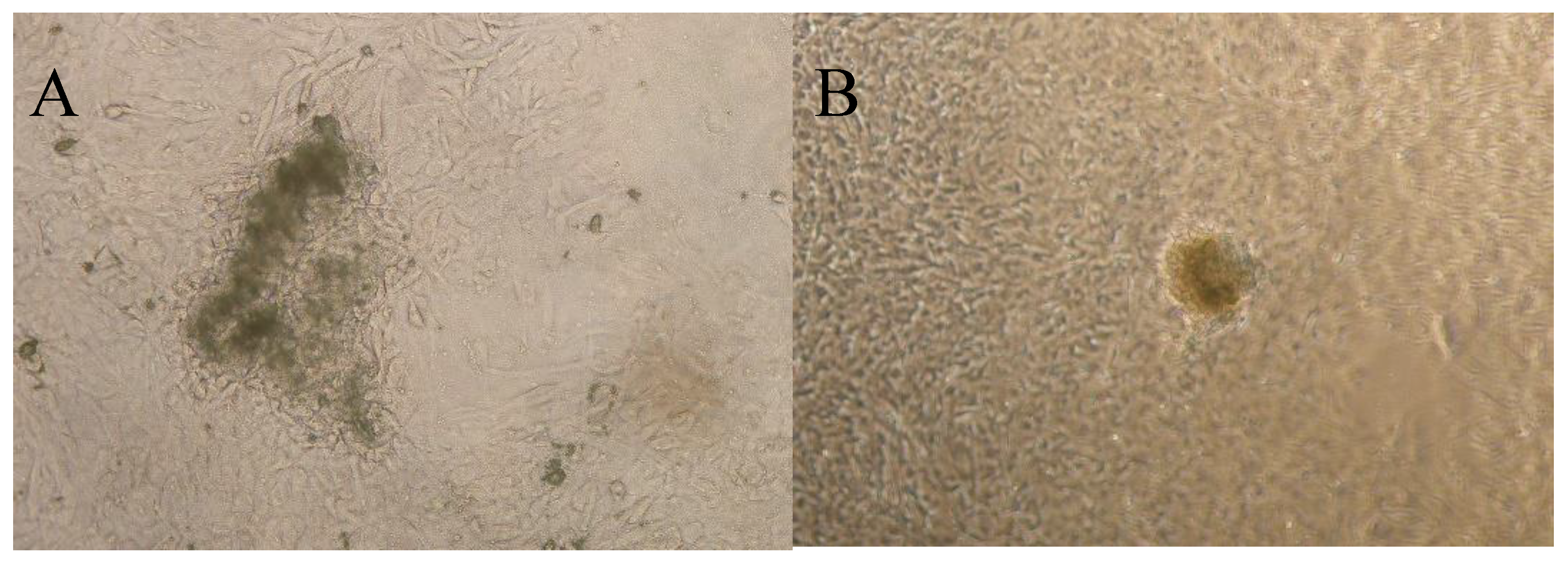

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schipper, J.; Chanson, J.S.; Chiozza, F.; Cox, N.A.; Hoffmann, M.; Katariya, V.; Lamoreux, J.; Rodrigues, A.S.L.; Stuart, S.N.; Temple, H.J.; et al. The status of the world’s land and marine mammals: Diversity, threat, and knowledge. Science 2008, 322, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Frankham, R.; Ballou, J.D.; Briscoe, D.A. A Primer of Conservation Genetics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, L.F.; Biebach, I.; Ewing, S.R.; Hoeck, P.E.A. The genetics of reintroductions: Inbreeding and genetic drift. In Reintroduction Biology: Integrating Science and Management; Ewen, J.G., Armstrong, D.P., Parker, K.A., Seddon, P.J., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 360–394. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M.; Gonzalez, S. Latin American deer diversity and conservation: A review of status and distribution. Écoscience 2003, 10, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piovezan, U.; et al. Marsh deer Blastocerus dichotomus (Illiger, 1815). In Neotropical Cervidology: Biology and Medicine in Latin American Deer; Duarte, J.M.B., González, S., Eds.; Funep/IUCN: Jaboticabal, Brazil, 2010; pp. 66–76. [Google Scholar]

- González, S.; Lessa, E.P. Historia de la mastozoología en Uruguay. In Historia de la Mastozoología en Latinoamérica, las Guayanas y el Caribe; Ortega, J., Martínez, J.L., Tirira, D.G., Eds.; Editorial Murciélago Blanco y Asociación Ecuatoriana de Mastozoología: Quito, Ecuador; México D.F., Mexico, 2014; pp. 381–404. [Google Scholar]

- González, S.; Aristimuño, M.P.; Moreno, F. New record in Uruguay of the marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus Illiger, 1815) redefines its southern geographic distribution area. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 12, 1419234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, S.; Duarte, J.M.B. Speciation, evolutionary history and conservation trends of Neotropical deer. Mastozool. Neotrop. 2020, 27, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, W.V.; Pickard, A.R. Role of reproductive technologies and genetic resource banks in animal conservation. Rev. Reprod. 1999, 4, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildt, D.E. Genetic resource banks for conserving wildlife species: Justification, examples and becoming organized on a global basis. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 1992, 28, 247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006, 126, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, K.; Ohta, H.; Kurimoto, K.; Aramaki, S.; Saitou, M. Reconstitution of the mouse germ cell specification pathway in culture by pluripotent stem cells. Cell 2011, 146, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Ogushi, S.; Kurimoto, K.; Shimamoto, S.; Ohta, H.; Saitou, M. Offspring from oocytes derived from in vitro primordial germ cell-like cells in mice. Science 2012, 338, 971–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rola, L.D.; Buzanskas, M.E.; Melo, L.M.; Chaves, M.S.; Freitas, V.J.F.; Duarte, J.M.B. Assisted reproductive technology in Neotropical deer: A model approach to preserving genetic diversity. Animals 2021, 11, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Papapetrou, E.P.; Kim, H.; Chambers, S.M.; Tomishima, M.J.; Fasano, C.A.; Ganat, Y.M.; Menon, J.; Shimizu, F.; Viale, A. Modeling pathogenesis and treatment of familial dysautonomia using patient-specific iPSCs. Nature 2009, 461, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Berg, D.; Ba, H.; Sun, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, C. Deer antler stem cells are a novel type of cells that sustain full regeneration of a mammalian organ—Deer antler. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colitti, M.; Allen, P.; Price, J.S. Programmed cell death in the regenerating deer antler. J. Anat. 2005, 207, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierdorf, U.; Kierdorf, H. Deer antlers—A model of mammalian appendage regeneration: An extensive review. Gerontology 2011, 57, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, F.; Sheppard, A. Adult stem cells and mammalian epimorphic regeneration—Insights from studying annual renewal of deer antlers. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2009, 4, 237–251. [Google Scholar]

- Rolf, H.J.; Kierdorf, U.; Kierdorf, H.; Schulz, J.; Seymour, N.; Schliephake, H.; Napp, J.; Niebert, S.; Wolfel, H.; Wiese, K.G. Localization and characterization of STRO-1 cells in the deer pedicle and regenerating antler. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tat, P.A.; Sumer, H.; Jones, K.L.; Upton, K.; Verma, P.J. The efficient generation of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells from adult mouse adipose tissue-derived and neural stem cells. Cell Transplant. 2010, 19, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, S.R. Long-term survival of fat transplants: Controlled demonstrations. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 1995, 19, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarak, S.; Okamoto, O.K. Human adipose-derived stem cells: Current challenges and clinical perspectives. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2010, 85, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Cui, C.; Chen, S.; Ren, J.; Chen, J.; Gao, Y.; Li, H.; Jia, N.; Cheng, L.; Xiao, L. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cell lines from adult rat cells. Cell Stem Cell 2009, 4, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, H.; Nakada, A.; Hashimoto, Y.; Shigeno, K.; Shionoya, Y.; Nakamura, T. Generation of canine induced pluripotent stem cells by retroviral transduction and chemical inhibitors. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2009, 77, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezashi, T.; Telugu, B.P.; Alexenko, A.P.; Sachdev, S.; Sinha, S.; Roberts, R.M. Derivation of induced pluripotent stem cells from pig somatic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 10993–10998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Táncos, Z.; Nemes, C.; Varga, E.; Bock, I.; Rungarunlert, S.; Tharasanit, T.; et al. Establishment of a rabbit induced pluripotent stem cell (RbiPSC) line using lentiviral delivery of human pluripotency factors. Stem Cell Res. 2017, 21, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, L.; He, L.; Chen, J.; Wu, Z.; Liao, J.; Rao, L.; et al. Reprogramming of ovine adult fibroblasts to pluripotency via drug-inducible expression of defined factors. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, K.; Sung, H.K.; Zhang, P.; Laflamme, S.; Vincent, P.; et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from equine fibroblasts. Stem Cell Rev. 2011, 7, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezashi, T.; Yuan, Y.; Roberts, R.M. Pluripotent stem cells from domesticated mammals. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2016, 4, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, G.G.; Costa, D.S.; Silva, S.E.M.; Alves, A.L.G.; Oliveira, M.F.; Martins, D.D.S.; et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells from large animals. Anim. Reprod. 2020, 17, e20200032. [Google Scholar]

- Manohar, M.; Lagutina, I.; Fulka, H.; Sung, L.-Y.; Eid, L.; Lazzari, G.; et al. Reprogramming of somatic cells in the sheep: Recent advances and future perspectives. Theriogenology 2016, 86, 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Durnaoglu, S.; Genc, S.; Genc, K. Patient-specific pluripotent stem cells in neurological diseases. Stem Cells Int. 2011, 2011, 212487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlin, R.; Davis, D.; Weiss, M.; Schultz, B.; Troyer, D. Expression of early transcription factors Oct-4, Sox-2 and Nanog by porcine umbilical cord (PUC) matrix cells. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2006, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, M.; Rodriguez, A.; De Frutos, C.; Caamaño, J.N.; Díaz, E.; Ikeda, S.; et al. Conventional and delayed embryo transfer in cattle—In vitro and in vivo embryo development and quality. Theriogenology 2015, 83, 467–476. [Google Scholar]

- Keefer, C.L. Artificial cloning of domestic animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 8874–8878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, A.F.; Oba, E.; Milazzotto, M.P. Contribution of mitochondria to the study of oocyte and embryo quality. Anim. Reprod. 2022, 19, e20220006. [Google Scholar]

- Hirao, Y. In vitro growth of oocytes from domestic species. Anim. Sci. J. 2011, 82, 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, L.F.; Paulini, F.; Silva, R.C.; Andrade, E.R.; Lucci, C.M. Cryopreservation of ovarian tissue from white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus): Effect of different concentrations of EG and DMSO. Theriogenology 2018, 120, 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Comizzoli, P.; Songsasen, N.; Wildt, D.E. Protecting and extending fertility for females of wild and endangered mammals. Cancer Treat. Res. 2010, 156, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Comizzoli, P. Biobanking efforts and fertility preservation in wildlife species: Can they be improved? Asian J. Androl. 2015, 17, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M.R.; Fayrer-Hosken, R.A. Possible mechanisms of mammalian immunocontraception. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2000, 46, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comizzoli, P.; Songsasen, N. Biobanking in wildlife: The end or a means to the end? Anim. Front. 2021, 11, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Tharasanit, T.; Comizzoli, P. Reproductive biotechnologies for endangered mammalian species. Vet. J. 2021, 269, 105604. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J.F.; Alfaro, V. Interspecies somatic cell nuclear transfer: Advancements and future perspectives. Cell Reprogram. 2007, 9, 229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Comizzoli, P. Germplasm banks for conservation of wildlife species: Relevance of reproductive biotechnologies for preserving diversity. Theriogenology 2017, 109, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Songsasen, N.; Comizzoli, P.; Travis, A.J.; Wildt, D.E. Advances in reproductive technology and genome resource banking for wildlife species. Theriogenology 2012, 78, 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Luvoni, G.C.; Chigioni, S.; Allievi, E.; Macis, D. Embryo technologies in dogs and cats. Theriogenology 2005, 64, 1665–1672. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, C.; Duchi, R.; Colleoni, S.; Lagutina, I.; Lazzari, G. Ovum pick-up, in vitro fertilization and embryo culture in cattle. Theriogenology 2007, 68, S59–S70. [Google Scholar]

- Comizzoli, P.; Holt, W.V. Breakthroughs and new thinking in gamete biology. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2019, 54, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M.L.; Venkatesh, D.; Ranganathan, V.; Comizzoli, P. Lessons from biobanking gametes and gonadal tissues for assisted reproduction in wildlife species. Cells 2022, 11, 2124. [Google Scholar]

- Luvoni, G.C. Conservation of endangered mammalian species through assisted reproduction: The role of in vitro embryo production. Anim. Reprod. 2020, 17, e20190062. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, M.; Hamatani, T. Concise review: Toward the generation of female gametes from induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells 2020, 38, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Comizzoli, P. The crucial role of biobanking and fertility preservation as tools for biodiversity conservation and how to better organize and integrate them globally. Biopreserv. Biobank. 2021, 19, 260–268. [Google Scholar]

- Faunes, F.; Larrain, J. Conservation of pluripotency in embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2012, 2012, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, K.; Glage, S.; Neumann, A.; Schwinzer, R.; Dorsch, M.; Tychsen, B.; et al. An iPSC line from the endangered drill monkey (Mandrillus leucophaeus) for comparative stem cell studies. Stem Cell Res. 2020, 47, 101911. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, R.; Holland, M.K.; Temple-Smith, P.; Verma, P.J. Inducing pluripotency in somatic cells from the snow leopard (Panthera uncia), an endangered felid. Theriogenology 2012, 77, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, R.; Liu, J.; Holland, M.K.; Temple-Smith, P.; Williamson, M.; Verma, P.J. Derivation of induced pluripotent stem cells from the tiger (Panthera tigris), an endangered felid. Stem Cells Dev. 2013, 22, 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Gouveia, C.; Huyser, C.; Egli, D.; Pepper, M.S. Lessons learned from somatic cell nuclear transfer. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2020, 64, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, M.A.P.; Silva, A.M.; Comizzoli, P.; Silva, A.R. Current advances in cryopreservation of wild carnivore semen for ex situ conservation. Theriogenology 2019, 130, 222–228. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Bansal, A.K. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defence system in boar spermatozoa. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 759–768. [Google Scholar]

- Comizzoli, P. Biobanking efforts and fertility preservation in wildlife species: Can they be improved? Asian J. Androl. 2015, 17, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, M.C.J.; O’Brien, J.K.; Canfield, P.J.; Allen, W.R. Reproductive technologies and genetic management of wild equids: A review. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2005, 17, 661–671. [Google Scholar]

- Novakovic, S.; Vujovic, M.; Djordjevic, B.; Stanimirovic, Z. Challenges and perspectives in cryopreservation of reproductive cells and tissues of endangered animal species. Cryobiology 2017, 77, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Li, C.; Wang, D.; Lu, J.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, T. Advances in cryopreservation of mammalian oocytes and embryos: A review. Theriogenology 2018, 113, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Comizzoli, P. Biobanking in wildlife: Facing the frontiers of freeze-drying technologies for conservation purposes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1200, 389–403. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago-Moreno, J.; Esteso, M.C.; Castaño, C.; Toledano-Díaz, A.; López-Sebastián, A.; González-Bulnes, A. Cryopreservation of semen from endangered species. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2012, 133, 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Rall, W.F.; Fahy, G.M. Ice-free cryopreservation of mouse embryos at −196 °C by vitrification. Nature 1985, 313, 573–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comizzoli, P.; Holt, W.V. Breakthroughs and new thinking in gamete biology. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2019, 54, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Loux, S.C.; Grieger, D.M.; Newton, G.R.; Canisso, I.F. Development and application of sperm cryopreservation technologies in wildlife species. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 220, 106389. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).