1. Introduction

Plants have been used by humans since immemorial time. On the one hand, natural elements have been used to satisfy humans’ necessities such as food, clothing, building materials and traditional medicine. On the other hand, plants have been included in cosmogonies of original civilisations being incorporated in the culture and beliefs, conferring them spiritual value [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In this sense, in Mexico several plant species that were used by Mesoamerican groups before the Spanish conquest, are still used due to their socio-cultural importance, for example the milpa and agave now considered part of Mexico biocultural heritage [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

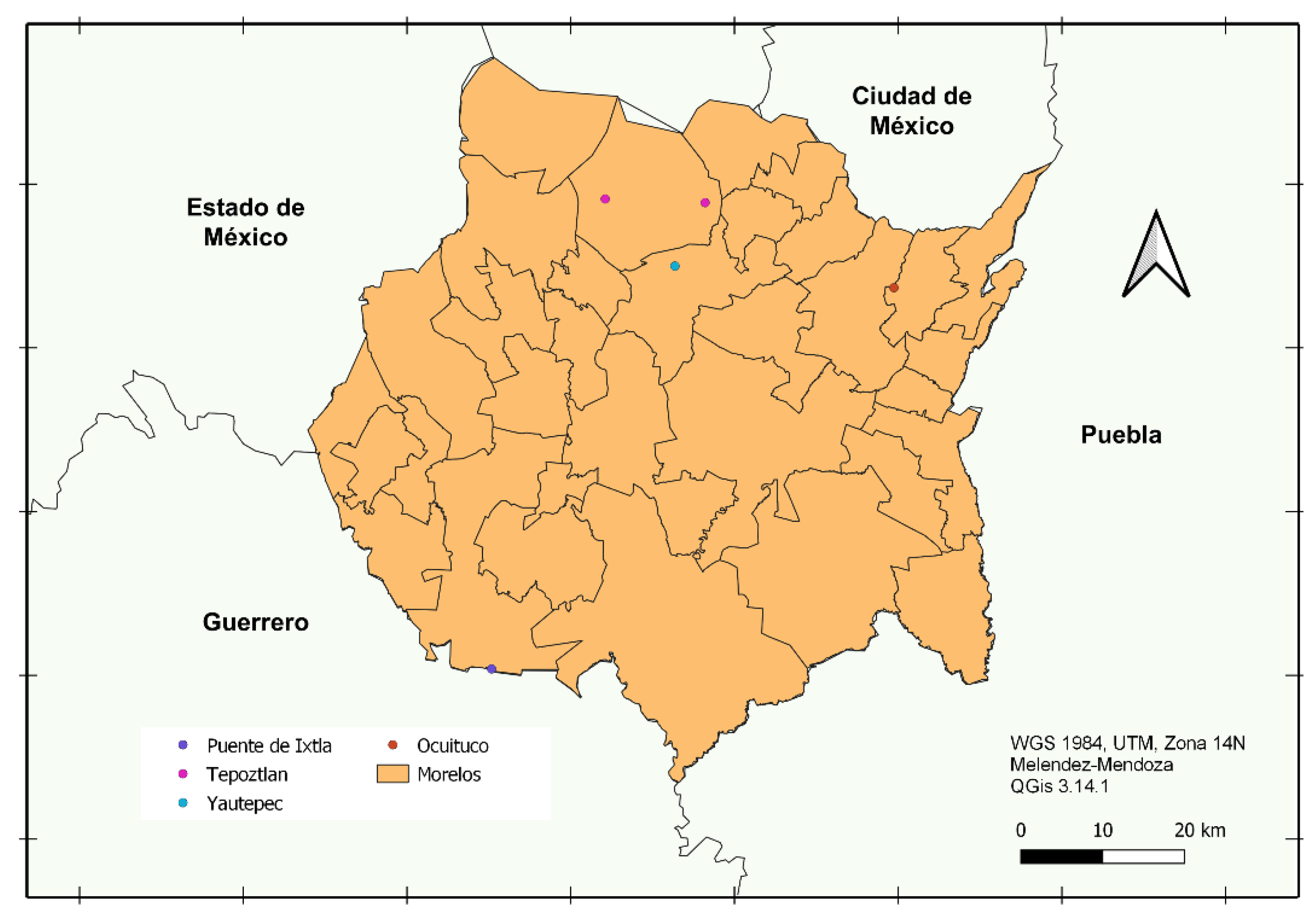

Pericon or yauhtli (

Tagetes lucida) is considered a biocultural heritage in Central Mexico, specifically in Yautepec (pericon hill in Nahuatl), Morelos. This is because it has been used since ancient Mesoamerican civilisations in religious ceremonies, traditional medicine, food and clothing.

Tagetes lucida is a plant that belongs to the Asteraceae family. It is native to Mexico, South and Central America [

10,

11,

12]. It is a wild plant that is characterised by its yellow colouration and intense aniseed odour [

13]. From an ecological perspective, the function of this plant within its ecosystem is of key importance. This is due to the fact that it plays a key role in attracting pollinators and deterring herbivores. Pericon is a perennial species that thrives in a distinct ecological niche: the ecotone between the tropical dry forest and the oak-pine forest, but also it grows in corn fields, in open fields and on roads.

Currently, the loss of species occur at a rate that exceeds the rate of origin of new species, and this is a consequence mainly due to human activities [

14], such as changes in land use, climate change, overexploitation, use of herbicides and deforestation [

15,

16,

17]. The rate of these changes has obligated to study the health of species, this includes the distribution and species richness, genetic erosion and other studies that allow to create the basis for management and conservation programs. In this sense, genetic erosion is referred to loss of genetic diversity within a species, often magnified or accelerated by human activities [

18,

19].

The deciduous forest is the main predominant ecosystem in Yautepec, Morelos and is one of the most coveted ecosystems for agricultural activity and urban development due to environmental conditions such as climate, soil type and vegetation [

20,

21]. Since colonial times, sugar cane production has played an important role in the regional economy, however, this activity has affected land use, and it also has had an important impact on the growth and distribution of the population since the 16th century. During the Porfiriato territorial expansion, emigration and immigration triggered the Zapatista movement in Morelos [

22]. In 1940 green revolution was implemented in Mexican agriculture with technological packs for increased production, this modernization caused a dependency on seeds, pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers [

23,

24]. These are examples of several important historical processes that have influenced changes in Yautepec territory.

To know the perception of Yautepec inhabitants about the pericon populations growth, a series of interviews were conducted with social actors (chronicler, historian, pericon sellers, communal landowners, Mexica dancers, local authorities and a civil organization). The questions include in this interview were: Do you think that the pericon is still growing as it did years ago, or has it decreased? Why? More than 50% of the social actors consider pericon populations to have decreased in the last 50 years. They mention “The field has decreased, everything has changed, the climate is very changing, there is a water shortage”, “Due to urban sprawl and the use of herbicides in the field”, “the field where pericon grew in, now it is occupied by a lot of condominiums or another type of crops”.

In this sense, Yautepec inhabitants perceive a decrease in pericon populations, and also an increase in the temperature caused by climate changes that could encourage the migration of pericon populations to colder zones. Furthermore, pericon populations have been exposed to herbicides applications and land burning, and commercial and traditional exploitation could influence the erosion of this species.

It is hypothesized that species with such specific habitat requirements, such as Pericon, are particularly vulnerable to habitat loss and deterioration [

25,

26,

27]. Changes in land use, overexploitation, the use of herbicides and deforestation have been identified as potential risks to this species [

15,

16,

17], with the resultant genetic erosion potentially leading to a decline in genetic diversity, which in turn affects the adaptability of the species, as has been observed in the case of

Pinus remota (Pinaceae) [

28] and wild amaranth species [

29]. This study sets out to investigate whether the loss of genetic diversity was the driving force behind the disappearance of

Tagetes lucida in the hills of Yautepec.

Molecular markers have become a simple and accurate tool for the estimation of genetic diversity and relationship among genotypes of any organism [

30,

31]. Maturase K (matK) and chloroplast ribulose biphosphate carboxylase (rbcL) have been utilised to establish relationships between genera, given that these genes possess conserved regions which facilitate primer design and enable the differentiation of genera by virtue of their variable regions [

30,

31,

32,

33]. The use of nuclear internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and chloroplast DNA markers has been demonstrated to facilitate the differentiation between species and populations [

33,

34,

35,

36]. The molecular markers employed for the purpose of determining relationships between populations within a species include random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), amplified fragment length polymorphic (AFLP), restriction fragment length polymorphic (RFLP) and simple sequence repeat (SSR), single nucleotide polymorphic (SNP), sequence-characterised amplified regions (SCARs) and inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) [

37,

38,

39,

40]. One of the most frequently used markers in the genus

Tagetes and in wild species is the Inter-Simple Sequence Repeat (ISSR) [

41,

42,

43], a multilocus marker system that has demonstrated a higher rate of reproducibility due to the utilisation of longer primers (16-25 mers). This variety of markers has been demonstrated to be expeditious, economical, highly variable, and amenable to reproducibility without the necessity for prior sequence information regarding the amplified locus [

44,

45].

The present study sought to ascertain whether the genetic diversity of pericon was the causative agent of its extinction in the hills of Yautepec. In order to achieve this objective, an evaluation of the genetic diversity of six populations of Tagetes lucida was conducted using PCR-based Inter-Simple Sequence Repeat (ISSR) markers.

3. Discussion

Molecular markers reveal sites of variation in the DNA [

46], In this work ISSR were used because these markers facilitate the determination of the genetic diversity among populations of the same species. The data showed that ISSR markers were an efficient tool for estimating genetic diversity in six populations of

Tagetes lucida. Evaluated pericon populations showed a high percentage of polymorphism with an average of 100%, thus

Tagetes lucida has important genetic diversity despite its traditional use, climate change, land use change, herbicide use and urbanization [

17]. This result is higher compared to Namita et al. [

43], Panwar et al. [

44] and Majumder et al. [

47] who reported 60.48%, 92.73% and 60.6% using ISSR markers for different species of

Tagetes, in fact the result was higher than the reported by Shahzadi et al. [

48] with 95.21% using RAPD markers in

Tagetes. The mean values of PIC and Rp (0.34 and 2.18, respectively) confirm that ISSR markers are efficient for analyzing the genetic diversity of

Tagetes lucida. These values are comparable to the results obtained by Panwar et al.[

44] for

Tagetes erecta (PIC=0.34) and Abd-dada et al. [

45] for an endemic plant of Morocco (

Euphorbia resinifera O. Berg) (Rp=2.8), based on ISSR markers.

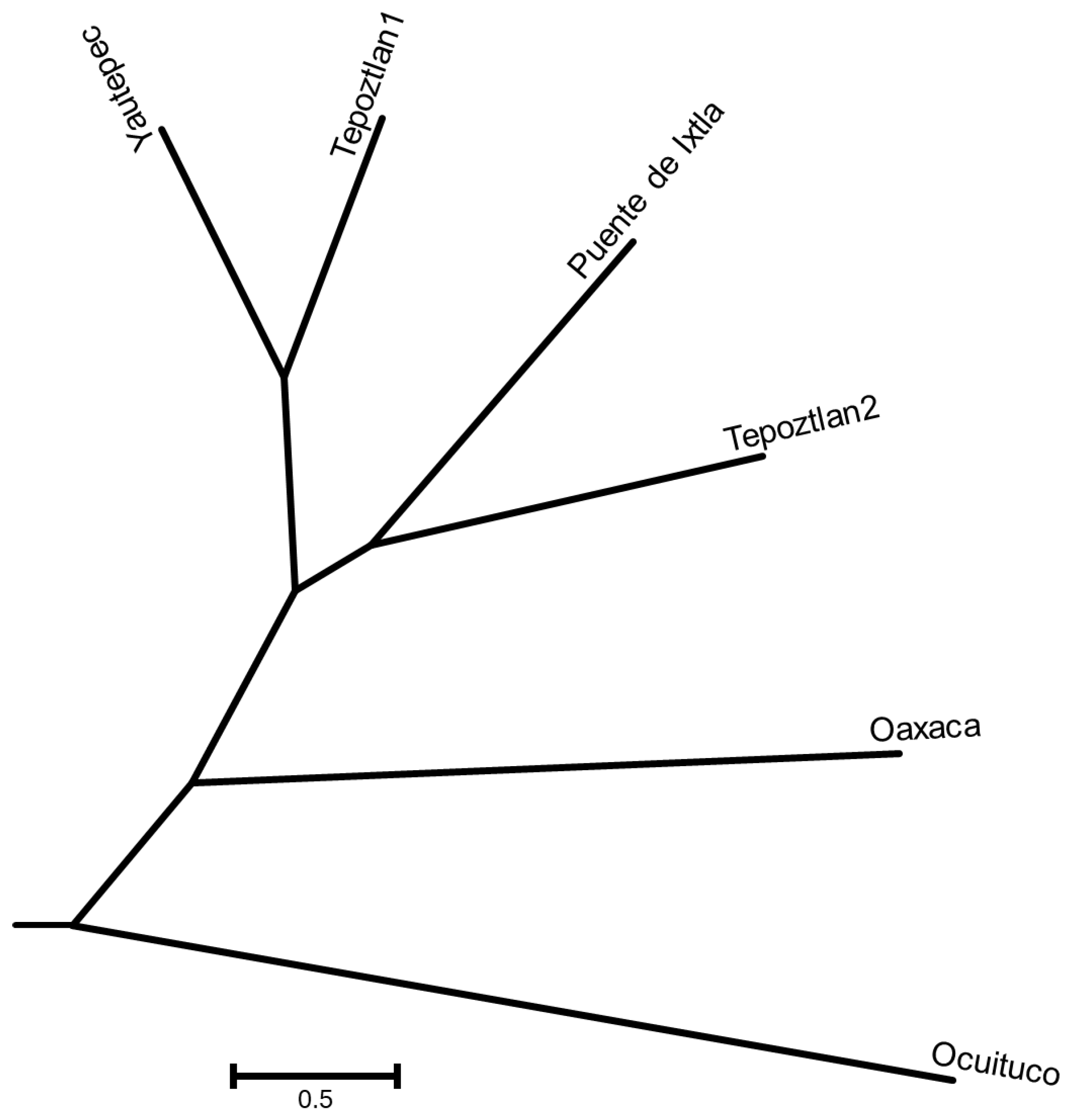

According to the analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA), the variation within the population was higher (79%) than between them (21%). A high level of genetic diversity within the population should help the plants to cope with local environmental changes[

45], as well as facilitate conservation and management programmes. The highest values of indices related to genetic variation were obtained for Tepoztlan1 (Ne= 1.43, I= 0.38 and He= 0.25) and Oaxaca (Na= 1.54 and PPL= 75.71%). This result indicates, on the one hand, that Tepoztlan1 and Oaxaca could be an important source of diversity for breeding conservation projects. The high genetic diversity observed in the Oaxaca population could have been due to the fact that the region is an open zone where several populations of

Tagetes lucida converge. According to the distances and the dendogram, pericon is not vulnerable to habitat fragmentation, but it could be to overexploitation, because the distances between Yautepec, Tepoztlan1, Puente de Ixtla and Tepoztlan2 are smaller, despite habitat fragmentation, these populations are located in places where inhabitants collect pericon for different uses year by year. The opposite occurs in the Oaxaca and Ocuituco regions, where the dendogram showed differentiation from the other populations, which could be due to both populations being located on the road.

It is reported that fragmentation and small and dispersed populations cause genetic isolation, loss of genetic diversity and low genetic flow among them, and it could lead to a serious erosion of the genetic pool [

28], in this investigation it was expected that diversity genetic would be low in the

Tagetes lucida population as a consequence of loss and habitat fragmentation. ISSR markers amplified genomic neutral regions, so with this markers it is obtained a neutral genetic diversity, these markers have the disadvantage of amplifying non coding regions, thus to gain a better understanding of the adaptative genetic load and its influence on the adaptation of species to environmental and habitat changes it is necessary to use molecular markers that facilitate the determination of adaptative genetic diversity that will allow to study the capacity of the plants to respond to environmental changes [

49,

50].

Tagetes lucida populations may have high genetic diversity among them as it is reported in this work using ISSR as molecular markers, however this does not mean that the species could survived to accelerated socio-environmental changes. The changes in Yautepec have occurred in an accelerate way and included pesticides use, in this regard inhabitants of Morelos mention the affectation of herbaceous plants due to use of glyphosate, they observed a decrease in wild plants such as pericon related with the use of this kind of products, so these activities are very abrupt and plants may have not opportunity to adapt and thus got extinct.

On the other hand, it is necessary to explore the use of other molecular markers, such as microsatellites. Since they are codominant, they will provide more precise data on gene flow and its directionality. Likewise, the use of chloroplast markers will provide ancestral signals about past population dynamics that could be linked to climatic changes during the Pleistocene and that may have contributed to the current distribution of the species.

Conservation Recommendations. The results obtained in this study may be useful for determining specific actions for the conservation of the species. Particularly in the state of Morelos, where traditional use of Tagetes lucida is intense, it is necessary to propose conservation strategies with the community, the stakeholders are an important referent in decision-making. Some propose could be to produce plants with seeds from wild populations because the annual extraction of wild plants from their populations could be silently impacting the populations. If it is possible to produce plants from wild seeds, it is possible to reduce the extraction of wild plants and promote their conservation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.B.T., M.M.C.R, L.A.A.M. and J.M.M.; methodology, J.M.M, K.B.T. and M.M.C.R.; validation, M.M.C.R.; formal analysis, J.M.M. and M.M.C.R.; investigation, K.B.T, M.M.C.R. and J.M.M.; resources, K.B.T., M.M.C.R.; data curation, J.M.M. and M.M.C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, K.B.T, M.M.C.R and J.M.M.; writing—review and editing, K.B.T., M.M.C.R. and J.M.M.; visualization, K.B.T., M.M.C.R. and J.M.M.; supervision, K.B.T., M.M.C.R.; project administration, K.B.T., M.M.C.R.; funding acquisition, K.B.T., M.M.C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.