1. Introduction

Transcriptomic methods, such as RNA sequencing, allow the study of gene expression in cells and tissue samples[

1,

2]. Initial transcriptomic technologies interrogated bulk tissues and thus did not address questions pertaining to tissue heterogeneity. Single cell RNA sequencing allows analysis of individual cells within the tissue, but does not answer questions about spatial context, such as cell-cell interactions among neighboring cells. More recently, spatial transcriptomics has emerged and allowed the spatial analysis of gene expression on intact tissues, thereby enabling a new understanding of how gene expression varies in cell neighborhoods [

3]. While spatial transcriptomics is a powerful technology, it does not provide information on post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation or methylation, which can regulate biology independently of gene expression. Therefore, combining spatial transcriptomics with techniques that provide spatial information on post-translational modifications (such as immunofluorescence) can help understand spatial control of important biologic phenotypes[

4,

5].

Integrating immunostaining data with spatial transcriptomics has numerous challenges, including harmonizing varied degrees of spatial resolution. Some platforms for spatial transcriptomics (such as the Visium and Cytassist platforms from 10x Genomics) permit RNA analysis in “spots,” allowing for analysis of cell groups rather than single cells. These slides typically capture RNA information in spots 55 uM wide and can have up to 5,000 spots per capture area[

6]. These spots contain variable numbers of cells depending on the tissue type. Immunostaining, by contrast, has much greater spatial resolution and typically allows interrogation of single cells. Because immunostaining analysis packages (Cell Profiler, ImageJ and QuPath) are optimized for single-cell analysis[

7,

8], extensive manual processing and annotation (for example with the LoupeBrowser 10x Genomics tool) is currently needed to integrate immunostaining data with spot-based spatial transcriptomics. These limitations make it difficult to objectively combine immunofluorescence data with spatial transcriptomic data. For example, if the researcher wishes to compare RNA expression in regions having high imaging marker expression with low imaging marker expression regions, the researcher must manually annotate thousands of spots based on the immunofluorescent marker. This manual immunofluorescent spot annotation is both time consuming and prone to interobserver variability, as the same spot could be annotated differently by different observers. This will, in turn, affect the analysis of spatial RNA expression and the results of the analysis of the same tissue by different researchers can yield different results, reducing reliability.

To address these limitations, we have designed a new program to integrate spatial transcriptomics and immunofluorescence data using MATLAB. While this program is generalizable to any immunofluorescent marker, we focused on γH2AX, a histone phosphorylation mark that indicates the presence of DNA damage. Our results indicate that manual integration of immunofluorescent data and spot-based spatial transcriptomics has high inter-observer variability that can affect which biologic processes are nominated for further study. By developing a new program that automates cell segmentation and annotates “spots” based on quantitative immunofluorescent information, our new analysis tool both decreases inter-observer variability and reduces time needed for data analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

Tissue sections:

The code was generated using brain cancer tissue with radiation induced DNA damage. Radiation exposure induces double stranded DNA breaks which can be detected by immunofluorescence for the phosphorylated Histone marker, γH2AX. This is a posttranslational modification which cannot be detected by RNA sequencing. We used mouse brain cancer (glioblastoma) tumor tissue for this study.

Animal models:

All mouse experiments were performed according to the guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Michigan (approved protocol: PRO00010680). C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson laboratory. Genetically engineered mouse model known as TRP mouse derived glioblastoma cells were provided as a Kind gift by C. Ryan Miller[

9] and were used to generate orthotopic syngeneic glioblastoma tumors, as described previously[

10]. In brief, TRP tumor cells (∼5 × 105) were orthotopically implanted in 3 female C57BL/6J mice. 2 of the 3 brain tumor-bearing mice were subjected to 4Gy radiation treatment (RT) to the brain after sedation with 2.5% isofluorane in an Orthovoltage irradiator. 1 mouse was not irradiated and served as control tumor tissue in this study. The 2 irradiated brain tumor bearing mice were euthanized through isofluorane overdose followed by cervical dislocation, one at 30 min post irradiation and the other at 6hours post irradiation. The unirradiated mouse was euthanized when neurological deficit developed. There was no randomization or exclusion criteria. The outcome measure was γH2AX expression in the tumors of the 3 mice used in this study.

Immunofluorescence:

Spatial transcriptomics:

Following immunofluorescence, the tissue sections were subjected to spatial transcriptomics using the 10x genomics platform, at the advanced genomics core(AGC), University of Michigan, using cytassist technique as described in the Visium CytAssist Spatial Gene Expression for FFPE-Tissue Preparation Guide (CG000518, 10× Genomics, Pleasanton, CA, USA). Briefly, the tissue was permeabilized to release ligated probe pairs from the cells, which then bind to the spatially barcoded oligonucleotides present on the spots. The barcoded molecules are then used to generate a sequencing-ready library. The data was analyzed with 10X genomics software(Space Ranger and Loupe Browser).

Annotation of the spot γH2AX positivity:

3 researchers independently annotated all the spots with at least 10 cells manually in all 3 sections as well as using the MATLAB program. Interobserver variability was compared using (a) average pairwise percentage agreement which is calculated as average of percentage agreement (% spots scored as positive by a pair of observers)+ (% spots scored as negative by a pair of observers) between all pairs of observers and (b) Fliess’ Kappa statistic [

11] (

https://real-statistics.com/reliability/interrater-reliability/fleiss-kappa/) using ReCal, a inter-rater reliability calculator tool (

https://dfreelon.org/utils/recalfront/recal3).

Kappa value 0 means no agreement and value 1 shows full agreement between observers.

Manual annotation:

γH2AX expression(red) had a punctate pattern within the nuclei (blue) (Figure 1A). A cell with moderate to high intensity of Texas red was considered a positive cell and if 10% of the cells within the spot were positive, the spot was annotated as a positive spot. Spots containing fewer than 10 cells were eliminated.

MATLAB program:

Our program mainly utilizes the functions provided by MATLAB’s Image Processing Toolbox for its analysis. It was originally designed to detect γH2AX, a biomarker labelling DNA damage [

12], on immunofluorescence, detected using Texas Red fluorescence channel. However, the program can detect any fluorophore in the nucleus and can be adapted to include detection of cytoplasmic and membrane immunostaining.

Our program is designed to individually analyze the group of cells located under each spot on a tissue section. To focus analysis on the cells underneath each spot, the program applies a mask to the image. Since the size of the spots is fixed at 55 uM, no customization is necessary to perform masking. However, the spot’s coordinates are necessary as an input into the program. These coordinates are the same coordinates as that of the barcodes used for RNA extraction from the tissue. These coordinates or spot midpoints can be obtained from Loupe browser, but they may also be user-defined. [

Appendix A provides the default settings for all user inputs]

Segmenting cells within spots is challenging due to the close proximity of nuclei in a in a 20x-magnification image, the standard magnification used in many spatial transcriptomic platforms. Many current programs are limited by their ability to define a cell’s nucleus when overlapping occurs [

13,

14,

15]. This program is designed to define the boundaries of a nucleus using DAPI intensity. The program takes advantage of the fact that the DAPI intensity is lower at the boundaries of the cells when compared to their center. The program first identifies all the pixels above the user defined threshold for DAPI intensity and deletes all pixels below the threshold (Figure 2). Following the first iteration, all the blue regions completely surrounded by black and lie within the user defined perimeter are considered as individual cells and the information from them is recorded. These cells are then eliminated from the picture for the next iteration. For the second iteration, it eliminates all pixels below an increased threshold of DAPI (the amount of increase is referred to as “range” which is user defined). This process continues until the upper limit of DAPI has been reached or until all the blue cells have been identified and the image is black. Each iteration gradually separates overlapping cells and stores each cell’s information. To ensure that most of the information is stored for overlapping cells, the user can manually define the perimeter of a cell. This perimeter refers to the average number of pixels that encompas a nucleus in an image. Providing an appropriate perimeter value prevents overlapping cells from being regarded as a single cell. Figure 3 depicts the step by step processing of the image by the code.

To identify a certain biomarker within the nucleus, the user can set the minimum and maximum threshold values for an image’s red, green, and blue channels. This range indicates how intense a pixel’s fluorescence must be in an image to be considered positive for the biomarker and should be set using proper biologic controls. The program sums the number of cells positive for the biomarker within a spot based on user input: the threshold of the number of positive pixels needed to consider a cell positive. The overall spot’s intensity value is based on the average pixel values within a spot using the fluorophore’s main color channel. For example, Texas Red mainly utilizes the image’s red channel. A mask is employed to only use the main channel’s positive pixels for the intensity calculation.

Based on the above information, the program analyzes each spot and produces the following output in the form of a table: the x and y coordinates of each spot’s center, the total number of cells and positive cells within each spot, the positivity value of each spot in percent form, each spot’s intensity value for the biomarker, and the final program’s call. The final program call will either be “positive” or “negative”, signifying whether the spot is positive or negative for the biomarker. This call is customizable by the user. It may be based on the spot’s intensity value, the percentage of positive cells present within the spot, or both values. The user has the choice to define the thresholds for each option.

Appendix A. describes the default settings used in the MATLAB program.

3. Results

3.1. Different Experimental Conditions Yielded Tissues Showing Varying Expression of the Marker

The tumor analyzed in this study is glioblastoma, which is the most aggressive primary brain malignancy in adults. Radiation treatment is one of the mainstay treatment modalities for this cancer[

16]. Glioblastoma is resistant to radiation treatment, as evidenced by tumor recurrence and short median overall survival time of about 16 months[

17,

18]. Radiation treatment acts by inducing double stranded DNA breaks[

19]. The ability of the tumor to repair this damage quickly allows it to become resistant to treatment. For this study, we used glioblastoma grown in mouse brain, which was subjected to radiation treatment.

γH2AX is a phosphorylation marker that indicates the presence of unresolved double stranded DNA(ds DNA) breaks (Figure 1A). Since radiation exposure induces dsDNA breaks, the expression of γH2AX is uniformly low in the unirradiated tissue (Figure 1B) and uniformly high in 30min post RT tissue (Figure 1C). We show that in the 6hrs post RT tissue, some repair of the DNA damage has occurred in specific regions of the tumor while damage persists in other regions (Figure 1D) and hence, the γH2AX expression is intermediate and non-uniform.

Spatial transcriptomic analysis platforms often provide gene expression data for spots, rather than individual cells. These spots vary in size depending on the analysis platform used but are often on the order of 50-60 µm in diameter. In conditions where γH2AX staining is heterogeneous (i.e., 6 hrs after RT), some 55 µM spots were clearly negative (Figure 1E, blue circle) or positive (Figure 1E, red circle) for the γH2AX marker. Other spots (Figure 1E, yellow circle) had a mixture of negative and positive cells and uncertainty about whether they should be labeled positive or negative for γH2AX.

3.2. High Interobserver Variability Is Noted in Manual Annotation of Spots with Non-Uniform Marker Expression

To assess inter-observer variability in the analysis pipeline, 3 independent researchers annotated the spots based on agreed upon criteria of moderate to high γH2AX expression within the nucleus being a positive cell and 10% or more of positive cells within the spot being called a positive spot. The tissues annotated were one unirradiated GBM tissue, which served as a negative control for γH2AX, one GBM tissue harvested 30 min after RT, which served as a positive control for γH2AX, and one GBM tissue harvested 6 hr after RT, which had heterogeneous γH2AX expression. The annotations were compared and interobserver variability was measured using percentage agreement and Fliess’ Kappa statistic. Kappa statistic of 0.8 and above is considered as near perfect agreement[

11]. Percentage agreement of 80% or above is considered the minimum acceptable agreement[

20].

In the unirradiated negative control tissue, 2785 spots were analyzed by 3 researchers. On an average, each spot contained 42.1 cells (range:11 to 88) as defined by the number of DAPI stained nuclei. The tissue showed uniform low positivity of γH2AX expression. The percentage of spots annotated as positive by the 3 researchers are 9.4%, 9.4% and 11.3%. There was high agreement among the 3 researchers on the annotation of individual spots. Indeed, the average agreement percentage is 98.42% while the Kappa agreement statistic was 0.912, both of which indicate near perfect agreement. Therefore, tissue showing uniform low positivity (fig.1b) had good agreement among the 3 researchers.

In the 30 min post RT tissue, 1857 spots were analyzed by 3 researchers. On average, each spot contained 45.8 cells (range:15 to 92) as defined by the number of DAPI stained nuclei. The tissue showed uniform high positivity of γH2AX expression. The percentage of spots annotated as positive by the 3 researchers are 98.5%, 98.4% and 98.4%. There was high agreement among the 3 researchers on the annotation of individual spots, with an average agreement percentage of 99.57% and a Kappa agreement statistic of 0.857, both of which indicate near perfect agreement. Hence, the tissue showing uniform high γH2AX positivity showed good agreement among the 3 researchers.

In the 6hrs post RT tissue, 2424 spots were analyzed by all 3 researchers. On an average, each spot had 48.3 cells (range: 10 to 91) as defined by the number of DAPI stained nuclei. The tissue showed non-uniform γH2AX expression. The percentage of spots annotated as positive by the 3 researchers are 43.2%, 65.4% and 69.8%.

There was also low agreement among the 3 researchers on the annotation of individual spots, with an average agreement percentage of only 69.06% and a Kappa statistic of 0.345, both of which indicate poor agreement. Therefore, tissue showing non-uniform intermediate positivity for γH2AX were annotated differently by different researchers. Figure 1E depicts a spot (yellow circle) with high disagreement between researchers.

Table 1 shows the extent of agreement (Fliess’ Kappa value and average pairwise agreement scores) between observers in different experimental conditions with varying γH2AX immunopositivity.

As seen in

Table 1, manual annotation of the spots led to significant differences in annotating the spots in the critical experimental condition where subsequent RNA expression analysis depends heavily on the annotation of the spots. The objective of spatial transcriptomics coupled with IF for γH2AX is to compare the RNA expression in γH2AX positive spots with that in γH2AX negative spots. The 3 observers generated heatmaps on Loupe Browser for differential RNA expression in γH2AX positive vs negative spots using their respective manual annotation of spots in the Rt 6hrs tissue. The top 3 upregulated and downregulated genes were different when each observer used their respective annotations for analysis (Figure 2). Hence, it is essential to have an objective method of annotation of the spots to ensure reproducibility and reliability of the data analysis.

3.3. Development of a Quantitative Tool To Analyze Immunofluorescence in Multicellular Spots

To overcome interobserver variability in manual immunofluorescent annotation, we developed a quantitative analysis tool using MATLAB. Our program is designed to consider each spot (cluster of cells) as one image and perform the nuclear segmentation in each spot individually (Figure 3).

The nuclear segmentation is performed through multiple iterations based on the intensity of DAPI and user defined range for iterations and perimeter of the nucleus (Figure 4). Allowing the user to define these parameters allows customization of segmentation to suit different tissue types having different cell density and size of cells.

Following segmentation, the Texas red intensity within the nuclei is measured, eliminating the chance of measuring RBC autofluorescence (red fluorescence without any underlying nucleus), as γH2AX. This reduces false positive annotation of the spot. The program default is set to take into consideration both Texas red intensity and the percentage of cells positive for γH2AX in the spot, to annotate it as positive or negative. However, the user can choose to use only intensity of the marker or only percentage positive cells to annotate the spots, depending on the immunostaining pattern of the marker in the specific tissue.

Appendix A describes the user defined parameters in detail.

3.4. Automated Quantification of Immunofluorescence Intensity

Our MATLAB program output provided the number of DAPI stained nuclei within the spot, the average intensity of Texas red within the nuclei present in the spot, and the percentage of cells positive for Texas red. We were able to objectively eliminate spots with too few cells (< 10). The mean intensity of Texas red in the spots ranged from 55 to 202.92. The percentage of positive cells in the spots ranged from 0 to 100. Spots with average intensity above 60 and percentage positive cells >10% were annotated as positive spots.

In the no RT tissue showing uniform low expression of γH2AX, the MATLAB program annotated 10.1% spots as positive, which agreed well with manual annotation. In the 30min post RT tissue with uniform high γH2AX expression, the MATLAB program annotated 98.5% spots as positive, which is similar to the total spots annotated as positive by the 3 researchers.

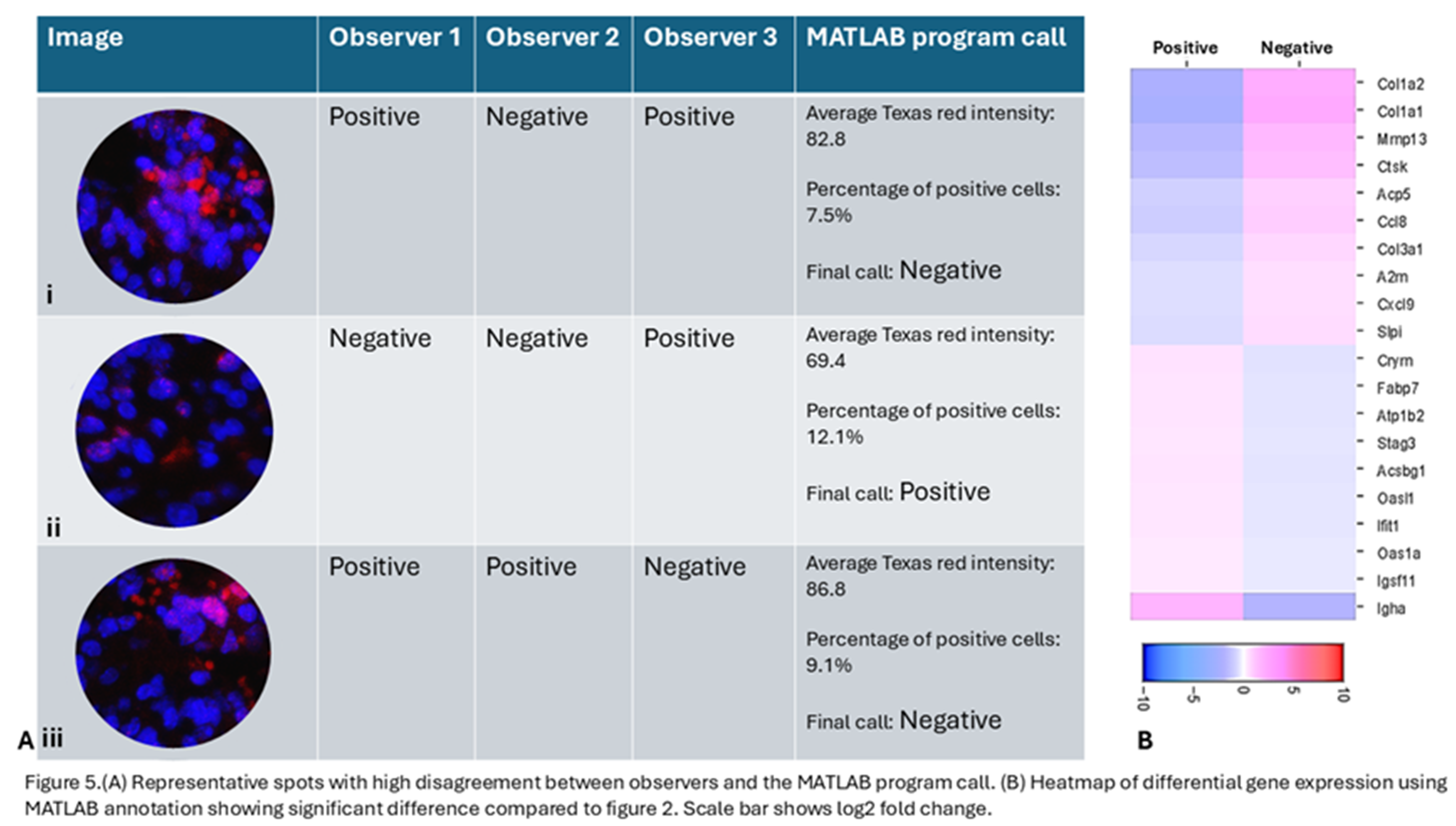

In the RT 6hrs tissue with heterogenous expression of γH2AX, the MATLAB program annotated 61.3% spots as positive, though this number could be altered by changing intensity and the percent positive cell threshold. In spots with high disagreement, such as the central spot in fig.1E which was annotated as positive by 2 researchers and negative by one researcher, the MATLAB program was able to objectively annotate it as negative because, although the average intensity of Texas red was 86.8, the percentage of positive cells was only 9.1%(Figure 5 A iii).

Figure 5 shows different scenarios with high disagreement between observers where the MATLAB program was able to objectively make a call. In Figure 5A i, the spot was annotated as positive by 2 researchers due to high apparent Texas red intensity. But the MATLAB program was able to identify that the red staining is not present over DAPI and is likely to be RBC autofluorescence and not true γH2AX positivity and was able to objectively call it as a negative spot based on the criteria set by the researchers. The heatmap (Figure 5B) showing differentially regulated genes between γH2AX positive and negative spots, as annotated by the MATLAB program. When the top 5 genes upregulated in γH2AX negative spots are compared with those identified by different observers based on their manual annotation, the MATLAB call based genes only matched with 2 of the genes identified by one observer. The 2 other observers’ top 5 upregulated genes did not match with the top 5 genes identified using MATLAB annotation. This shows that while trying to identify candidate genes using IF based marker annotation, it is essential to have an objective tool to allow for reliable and reproducible results and our MATLAB program allows for such objective assessment.

4. Discussion

Advances in spatial biology have yielded insights into tissue heterogeneity and cancer biology in a spatially relevant fashion. Several modalities to study spatial transcriptomics are currently available[

21,

22,

23], but they have the inherent limitation of not being able to study posttranslational modifications and other epigenetic changes such as histone modifications.

Posttranslational modifications like phosphorylation of histone H2A.x are well documented and shown to have a great impact on the biology of several cancers. These modifications cannot be studied by measuring RNA expression, since the changes happen after the RNA has been translated into protein. Histone modifications such as trimethylation of H3K27 also cannot be detected using transcriptomics but can be identified using IF. Spatial protein expression can be studied using multiplex IF platforms with advanced image analysis programs like Akoya biosciences[

24,

25]. However, this cannot be combined with transcriptomic analysis and only a limited number of proteins can be studied. This lack of combined transcriptomic and post-translational analysis can limit biological insights.

Combining immunofluorescence and spatial transcriptomics provides the opportunity to study RNA expression as well as protein expression on the same tissue section. However, there are limited tools available to integrate spatial RNA sequencing data with IF images. This is especially relevant because the current spatial transcriptomics platforms are predominantly based on multicellular region RNA capture. The currently available analysis tools and advanced bioinformatic tools used to analyze this data do not allow automated and objective image analysis of parameters like intensity of marker expression, percentage of marker positive cells within the multicellular spot and other image analysis parameters essential for downstream analysis. Such analyses need to be done manually and are prone to interobserver variability.

Interobserver variability is widely reported in histopathological studies of cancer tissues evaluating routine histopathology images as wells as images of immunostained sections [

26,

27,

28]. Percentage agreement and Kappa statistic have been widely used to quantify inter-observer variability. Kappa statistic of 0.8 and above is considered as near perfect agreement[

11], which was seen in evaluation of tissues with uniform low or uniform high expression of the marker but not in the non-uniform marker expression condition. In the case of spatial transcriptomics, annotating the spots accurately and objectively based on the immunofluorescent image is essential to study the spatial RNA expression and draw conclusions reliably and reproducibly. Currently, there are no platforms with the ability to quantitatively assess immunofluorescent image and annotate spots while complementing Cytassist. Our program is the first tool to accomplish this task.

Our program is designed to annotate multicellular spots, with varying marker expression within the spots, as positive or negative based on user defined criteria of “ground truth.” These criteria can be modified to suit the tissue type, experimental condition and the marker expression pattern. Originally, the program was written to detect the presence of γH2AX; however, other nuclear markers of post-translational modifications such as 5-methyl cytosine[

29] and H3K27me3(trimethyl H3K27) could also be used[

30]. The program provides researchers with the ability to alter threshold values for all three color channels: red, green, and blue. The combination of these channels allows fluorescent markers of any color to be detected. For example, combining the red and green channels will allow the program to detect an orange fluorophore. The user can define this parameter and extend the applicability of the tool to other IF images and multiplex IF images. The program’s nuclei stain detection is currently limited to DAPI or another blue stain as it is widely used as nuclear stain; however, this feature may be added to future versions, if required.

Our work also has some limitations. Our code currently only identifies nuclear immunostaining as the segmentation is based on DAPI intensity. Since the essential step to tease apart overlapping cells mandates segmentation to be strictly limited to DAPI intensity, it cannot be easily modified to suit cytoplasmic or membrane staining in its current form. Another limitation is that this tool applies only to annotation of circular multicellular spots. However, with modifications to defining parameters, the program can be modified to annotate the cells objectively based on IF.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our unique MATLAB program allows researchers to objectively assess immunofluorescent markers combined with spatial transcriptomics performed on Cytassist, a commonly used spatial transcriptomics platform. It allows its user to accurately and efficiently analyze immunofluorescent nuclear biomarkers within spots without the need for laborious and subjective manual annotation.

Author Contributions

Sravya Palavalasa: Conceptualization, biological experimentation, manual annotation of the spots as one of the 3 observers, drafting the manuscript. Emily Baker: Creating the MATLAB program described in this manuscript, drafting the manuscript. Jack Freeman: Manual annotation of the spots as one of the 3 observers. Aditri Gokul: Manual annotation of the spots as one of the 3 observers. Weihua Zhou: Intellectual input, manuscript preparation. Thomas Dafydd: Intellectual input, manuscript preparation. Wajd Al-Holou: Intellectual input, manuscript preparation. Meredith Morgan: Intellectual input, manuscript preparation. Theodore S Lawrence: Intellectual input, manuscript preparation. Daniel Wahl: Conceptualization, drafting and editing the manuscript.

Funding

Sravya Palavalasa was supported by the American Cancer Society postdoctoral fellowship, PF-23-1077428-01-MM, [

https://doi.org/10.53354/ACS.PF-23-1077428-01-MM.pc.gr.175459]. Meredith A Morgan, Daniel R Wahl and Theodore S Lawrence were supported by the SPORE grant, P50CA269022. Meredith A Morgan was supported by R01CA240515, Daniel R Wahl was supported by the NCI (K08CA234416 and R37CA258346), Rogel Cancer Center Munn Team Science Catalyst Award, Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA46592, Damon Runyon Cancer Foundation, Ben and Catherine Ivy Foundation, and the Sontag Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal experiments in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Michigan (approved protocol: PRO00010680) and all methods were performed according to the guidelines and regulations provided by IACUC.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Advanced genomics core at the University of Michigan for performing spatial transcriptomics sequencing on the tissues used in this study. We acknowledge Dr. Ryan Miller from the university of Alabama for sharing the syngeneic mouse glioblastoma cells used to generate the mouse tumors in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| RNA |

Ribonucleic acid |

| IF |

Immunofluorescence |

| γH2AX |

Phosphorylated Histone H2AX |

| RT |

Radiation Treatment |

| IACUC |

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Default Setting Determinants:

| Setting |

Default Value |

| Range for Cell Sweeping(a) |

5:10:250 |

| Average Cell Perimeter(b) |

80 |

| Intensity Lower Threshold(c) |

55 |

| Percent Positive Threshold(d) |

5 |

| Red Pixel Value (Lower Threshold) (e) |

55 |

| Blue Pixel Value (Lower Threshold) (e) |

50 |

| Green Pixel Value (Lower Threshold) (e) |

0 |

| Pixel Clean-up (f) |

20 |

This range refers to the program’s step-incrementation to detect each cell’s nucleus. MATLAB’s impixel() function was used to determine the pixel’s blue channel values on the borders of the nucleus. Multiple cells from different spots were tested with this function. All cells’ nuclei borders were found to be above 60 in the blue channel. A final value of 50 was chosen to ensure pixels considered positive for the biomarker were considered part of the nucleus (See e).

The range’s high threshold was determined by its incrementation value, 25. Step values between 1 and 50 were tested for nucleus border determinacy. A step value of 25 counted the highest number of cells accurately within a spot with the most efficiency. The maximum blue channel value is 255; therefore, this step increment will reach 250.

Cells from different spots were used to determine this default value. The pixels surrounding the nuclei borders were manually counted; the average was approximately 80. Any program-detected region with a perimeter above the average cell perimeter is considered multiple overlapping nuclei.

The minimum red channel value for a pixel to be considered positive for the biomarker determined the intensity lower threshold (See e).

The percent positive threshold refers to the percentage of positive cells necessary to consider a spot positive for the biomarker. The researchers were presented with spots ranging from 1 to 30 percent positive. Utilizing tissue samples that had been manually counted, the researchers chose five percent as the lower threshold.

The red, blue, and green pixel values are the minimum channel values for a pixel to be considered positive. Green is absent from the image, so its channel's lower threshold is set at zero. Texas Red is a combination of blue and red channels. The researchers were presented with a range of pixel colors within different cells that could be considered positive. They chose the minimum pixel color they would consider positive during manually annotation. This pixel’s channel values were rounded and used as the minimum thresholds.

Pixel clean-up refers to a region’s minimum pixel number to be considered a nucleus. The program deletes any regions less than or equal to this value. These regions are considered noise within the image or the remnants of an already documented cell. Deletion values between 5 and 25 were tested. The value 20 had the highest noise reduction accuracy.

The appendix is an optional section that can contain details and data supplemental to the main text—for example, explanations of experimental details that would disrupt the flow of the main text but nonetheless remain crucial to understanding and reproducing the research shown; figures of replicates for experiments of which representative data is shown in the main text can be added here if brief, or as Supplementary data. Mathematical proofs of results not central to the paper can be added as an appendix.

References

- Lowe, R.; et al. Transcriptomics technologies. PLOS Computational Biology 2017, 13, e1005457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nature Reviews Genetics 2009, 10, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.G.; et al. An introduction to spatial transcriptomics for biomedical research. Genome Medicine 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, N.; et al. Protecting RNA quality for spatial transcriptomics while improving immunofluorescent staining quality. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz, A.; Basisty, N.; Schilling, B. Quantification and Identification of Post-Translational Modifications Using Modern Proteomics Approaches. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer US: 2021; p. 225-235.

- Xun, Z.; et al. Reconstruction of the tumor spatial microenvironment along the malignant-boundary-nonmalignant axis. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankhead, P.; et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Scientific Reports 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrekoussis, T.; et al. Image analysis of breast cancer immunohistochemistry-stained sections using ImageJ: an RGB-based model. Anticancer Res 2009, 29, 4995–8. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, R.S.; et al. Core pathway mutations induce de-differentiation of murine astrocytes into glioblastoma stem cells that are sensitive to radiation but resistant to temozolomide. Neuro Oncol 2016, 18, 962–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ER, P.; et al. Purine salvage promotes treatment resistance in H3K27M-mutant diffuse midline glioma - PubMed. Cancer & metabolism, 04/09/2024. 12(1).

- Li, M.; Gao, Q.; Yu, T. Kappa statistic considerations in evaluating inter-rater reliability between two raters: which, when and context matters. BMC Cancer 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, L.-J.; El-Osta, A.; Karagiannis, T.C. γH2AX: a sensitive molecular marker of DNA damage and repair. Leukemia 2010, 24, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Kim, C. Impact of the accuracy of automatic segmentation of cell nuclei clusters on classification of thyroid follicular lesions. Cytometry Part A 2014, 85, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, F.; Yang, L. Robust Nucleus/Cell Detection and Segmentation in Digital Pathology and Microscopy Images: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Reviews in Biomedical Engineering 2016, 9, 234–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronneberger, O.; et al. Spatial quantitative analysis of fluorescently labeled nuclear structures: Problems, methods, pitfalls. Chromosome Research 2008, 16, 523–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R; et al. Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2005, 352.

- Lakomy, R.; et al. Real-World Evidence in Glioblastoma: Stupp's Regimen After a Decade. Frontiers in Oncology 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santosh, V.; Sravya, P.; Arivazhagan, A. Molecular Pathology of Glioblastoma- An Update. Advances in Biology and Treatment of Glioblastoma 2017.

- Zhou, W.; et al. Purine metabolism regulates DNA repair and therapy resistance in glioblastoma. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. , Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2012, 22, 276–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Holou, W.N.; et al. Subclonal evolution and expansion of spatially distinct THY1-positive cells is associated with recurrence in glioblastoma. Neoplasia (New York, N.Y.) 2023, 36.

- Arora, R.; et al. Spatial transcriptomics reveals distinct and conserved tumor core and edge architectures that predict survival and targeted therapy response. Nature Communications, 2023, 14.

- Suzuki, A.; et al. Identification of invasive subpopulations using spatial transcriptome analysis in thyroid follicular tumors. Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine 2024, 58, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhaveri, N.; et al. Mapping the Spatial Proteome of Head and Neck Tumors: Key Immune Mediators and Metabolic Determinants in the Tumor Microenvironment. GEN Biotechnology 2023, 2, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, J.W.; et al. Spatial mapping of protein composition and tissue organization: a primer for multiplexed antibody-based imaging. Nature Methods 2022, 19, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bockstal, M.R.; et al. Interobserver variability in the assessment of stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (sTILs) in triple-negative invasive breast carcinoma influences the association with pathological complete response: the IVITA study. Modern Pathology 2021, 34, 2130–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, M.E.; et al. High Interobserver Variability Among Pathologists Using Combined Positive Score to Evaluate PD-L1 Expression in Gastric, Gastroesophageal Junction, and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol 2023, 36, 100154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bockstal, M.R.; et al. Interobserver Variability in Ductal Carcinoma In Situ of the Breast. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 2020, 154, 596–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meevassana, J.; et al. 5-Methylcytosine immunohistochemistry for predicting cutaneous melanoma prognosis. Scientific Reports 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, N.; et al. Immunohistochemistry for trimethylated H3K27 in the diagnosis of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours. Histopathology 2017, 70, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Agreement scores and Kappa statistic for 3 experimental conditions showing least reliability in annotating section with non-uniform γH2AX immunopositivity.

Table 1.

Agreement scores and Kappa statistic for 3 experimental conditions showing least reliability in annotating section with non-uniform γH2AX immunopositivity.

| |

Negative control (No RT) |

Positive control (RT 30 min) |

Critical Experimental condition (RT 6hrs) |

| No. of spots annotated |

2785 |

1857 |

2424 |

| Agreement between observers 1 and 2 |

98.06% |

99.35% |

73.93% |

| Agreement between observers 2 and 3 |

99.21 |

100% |

57.47% |

| Agreement between observers 1 and 3 |

97.99% |

99.35% |

75.78% |

| Average pairwise agreement score |

98.42% |

99.57% |

69.06% |

| Fliess’ Kappa |

0.912 |

0.857 |

0.345 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).