1. Introduction

Nowadays, porous ceramics have been widely used in various fields, including the water treatment, catalyst support, sound absorption, and so on. The application of the porous ceramics is closely related to the pore size and pore structure. For example, the porous ceramics with open pore sizes ranging from 100 to 1000 μm can be used in sound absorption, physical filtration, thermal insulation [

1,

2,

3], while those with open pore size of 1~100 μm are widely used in bacteria culture, catalyst support, vacuum chunk, and so on [

4,

5,

6].

Recently, gel casting has been successfully used to prepare porous ceramics. Using gel casting combined with foaming techniques, porous ceramics with porosity as high as 80~90% were achieved [

7,

8]. However, their pore size was always higher than 100μm. Moreover, in the gel casting route, toxic acrylamide as raw materials is often used, limiting it large scale production. On the other hand, by introduction of sacrificial template, the gel casting can be used to produce pores with size of several or several tens of micrometers [

9]. However, this method is not environmentally friendly. In addition to the gel casting, the direct stacking and sintering method for preparation of porous ceramics were recently reported [

10,

11]. Interestingly, this method does not need the pore-forming agents or sacrificial templates. In this method, both the large size and the small size powders were used as raw materials, which were then dry pressed and sintered. The through-pores with size of serval micrometers were directly formed during the sintering process. Inspired by this, we realize that if the large size particles are introduced as raw materials in the gel casting, the porous ceramics with through-pores would be obtained without introduction of pore-forming agents or sacrificial template. Moreover, the pore size and porosity of the porous ceramics would be easily tuned.

Intrigued by this idea, in this paper we developed a new and low-cost gel casting method to prepare porous ceramics with though-holes, which is of potential application in fabrication of large size ceramic sheets used for vacuum chunk. To meet the requirement of the ceramic chunk, we fully take into account the design of the component, the selection of the raw materials, and the microstructure of the products. Especially, to avoid the use of the toxic acrylamide, new gel casting process was developed using carrageenan as crosslinking agent. The finally obtained porous ceramic shows a high strength over 160MPa together, a high porosity over 30%, and a high permeability of ~36 L/min/cm 2.

2. Materials and Methods

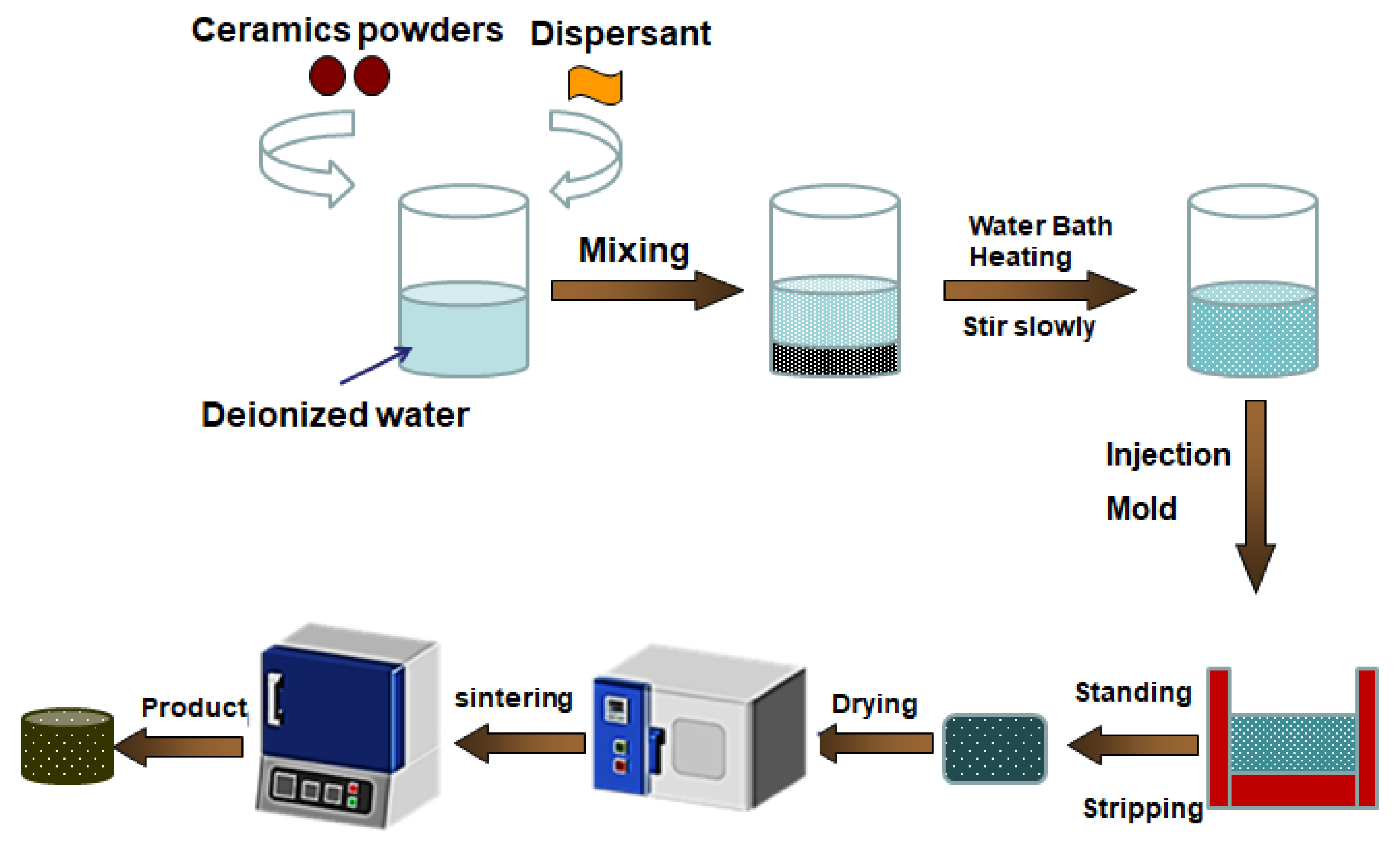

The experimental process for preparation of the porous ceramics is shown in

Figure 1. In a typical experiment, 1.5g ammonium polyacrylate was added into 64g deionized water. Then, 0.5g KCl and 0.5g carrageenan was added into the solution [

12]. After that, the pH of the solution was adjusted to 8 with ammonia. Subsequently, 150g ceramic powders were slowly added to deionized water, and stirred at 80°C for 10 min. The prepared ceramic slurry was then poured into a mold constructed by glass sheets. After the slurry was cooled to room temperature, the slurry was self-solidified. The obtained green bodies with thickness of about 5 mm was then dried at 60°C for 12h, and then sintered at 1500 °C for 4h. The ceramic powders were composed of 10 wt. % kaolin powders (4000 mesh), 5 wt. % sintering aids (Y

2O

3/MgO=8/2, w/w), and 85 wt.% alumina powders. Particularly, the alumina powders consist of large size Al

2O

3 aggregate particles (200~1000 mesh) and small size active α-Al

2O

3 micropowders (1~3μm).

The microstructure of samples was studied by scanning electron microscope (JSM-6700, Japan). The porosity and bulk density were measured by Archimedes method. The flexural strength was tested by a three-point bending method under a universal testing machine (HT-2402, China). The pore size and the size distributions were measured using mercury intrusion porosimetry (Auto Pore V9600, USA). The gas permeability of the porous ceramics was tested by self-made permeability testing equipment, and N2 was selected as the gas source. Before testing, the samples were polished into pieces with diameter of 50mm and thickness of 6 mm.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mechanism of Forming Through-Holes by Gel Casting Combined with Particle Stacking and Sintering Method

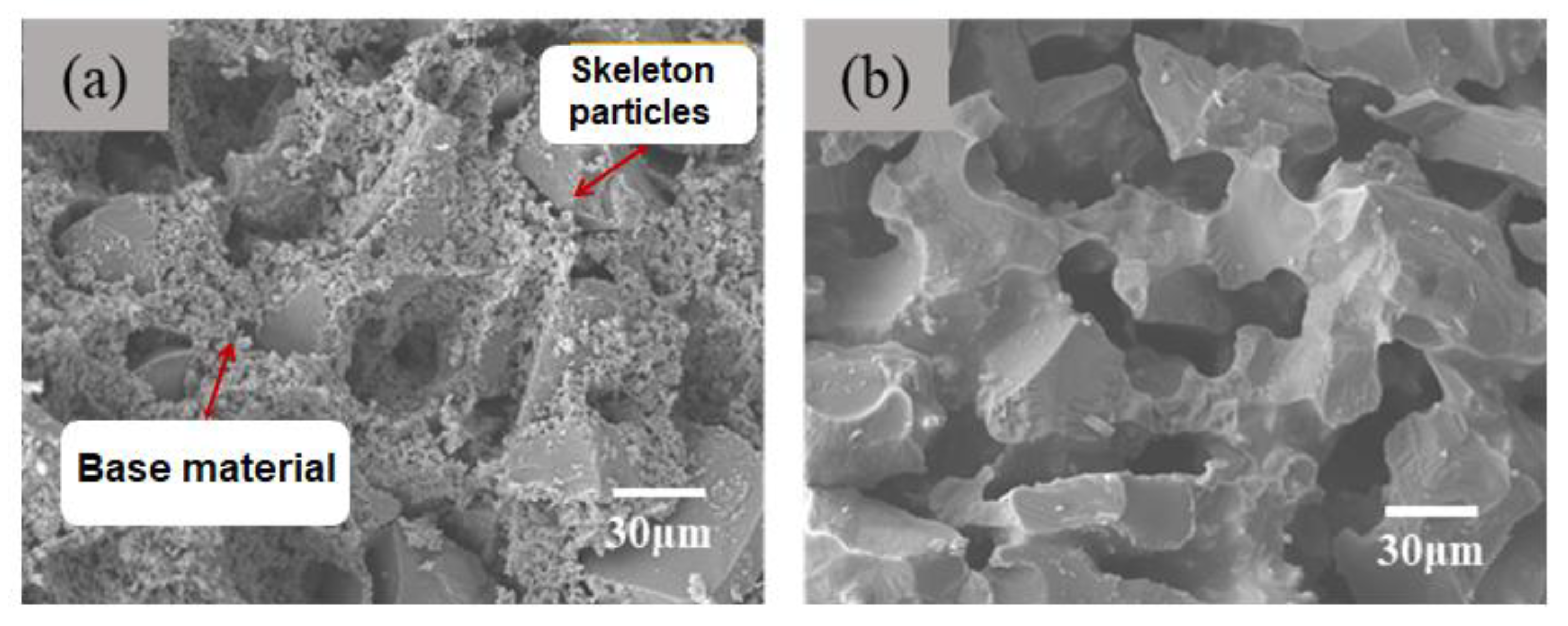

In this paper, large-size white corundum is used as ceramic aggregate, and the α-Al

2O

3 micropowder is the matrix (binders). The method of combining gel casting with particle stacking and sintering is used to successfully build porous ceramics. The results of a typical sample are shown in

Figure 2.

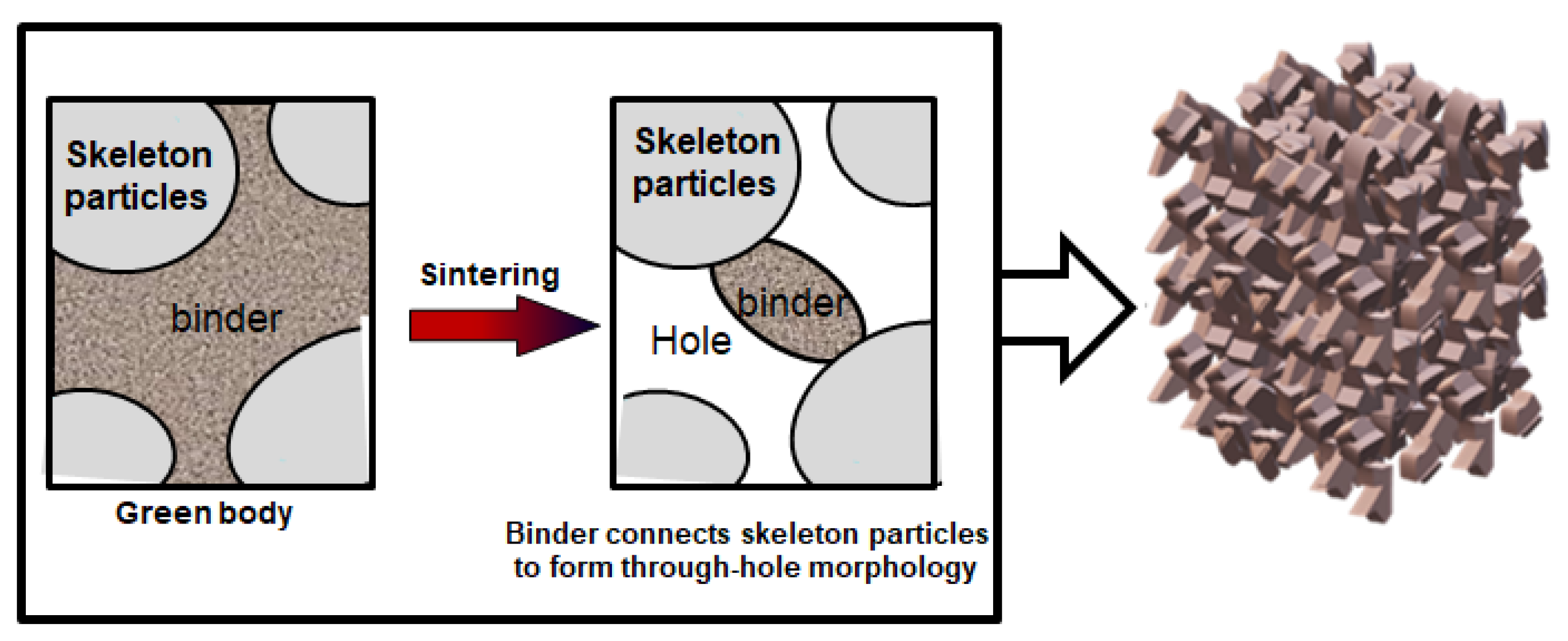

In the green body, the ceramic matrix is covered on the aggregate surface or filled in the pores formed by particle stacking. During sintering process, the matrix is more prone to shrink due to the volume effect between the matrix and the aggregate. After shrinkage, the matrix forms a sintering neck, connecting the aggregate particles. And the pore structure is directly formed by aggregate accumulation. The gel casting method enables the particles loosely accumulate, and the matrix and aggregate distribute more uniform. Therefore, the final porous ceramics have a large number of interconnected pore structures. As indicated by

Figure 3, the aggregates and binders (matrix) are loosely stacked in greed body. After sintering at a certain temperature, large particle aggregates of ceramics are connected by binders. Since only a few points are connected, it presents a three-dimensional through-hole morphology.

3.2. Influence of Aggregate-Matrix Ratio on Morphological Structure and Properties of Through-Porous Ceramic Materials

It is known that the pore size and porosity of the porous ceramics is influenced by many factors when gel casting method is used. In our work, the large size Al

2O

3 aggregates and α-Al

2O

3 micropowders were introduced in the slurry. Obviously, in addition to the solid content of the slurry, the size of the Al

2O

3 aggregate and its content shows great influence on the pore structure and pore size. Therefore, the component design is of great importance to tune the properties of the porous ceramics. To investigate the effect of the weight ratio of the Al

2O

3 aggregate to α-Al

2O

3 micropowders on the pore structure of the porous ceramics, five samples with different Rm (Rm=10wt.%, 20 wt.%, 30 wt.%, 40 wt.%, and 50 wt.%) were prepared. Here, Rm=Wm/(Wa+Wm), where Wm and Wa refer to the weight of Al

2O

3 aggregates and α- Al

2O

3 micropowder, respectively. The raw materials designed for the five samples are listed in

Table 1. The size of the Al

2O

3 aggregates in the slurry was kept same (320 mesh) for all samples, and the solid content of the slurry was fixed at about 70 wt.% (~40 vol.%).

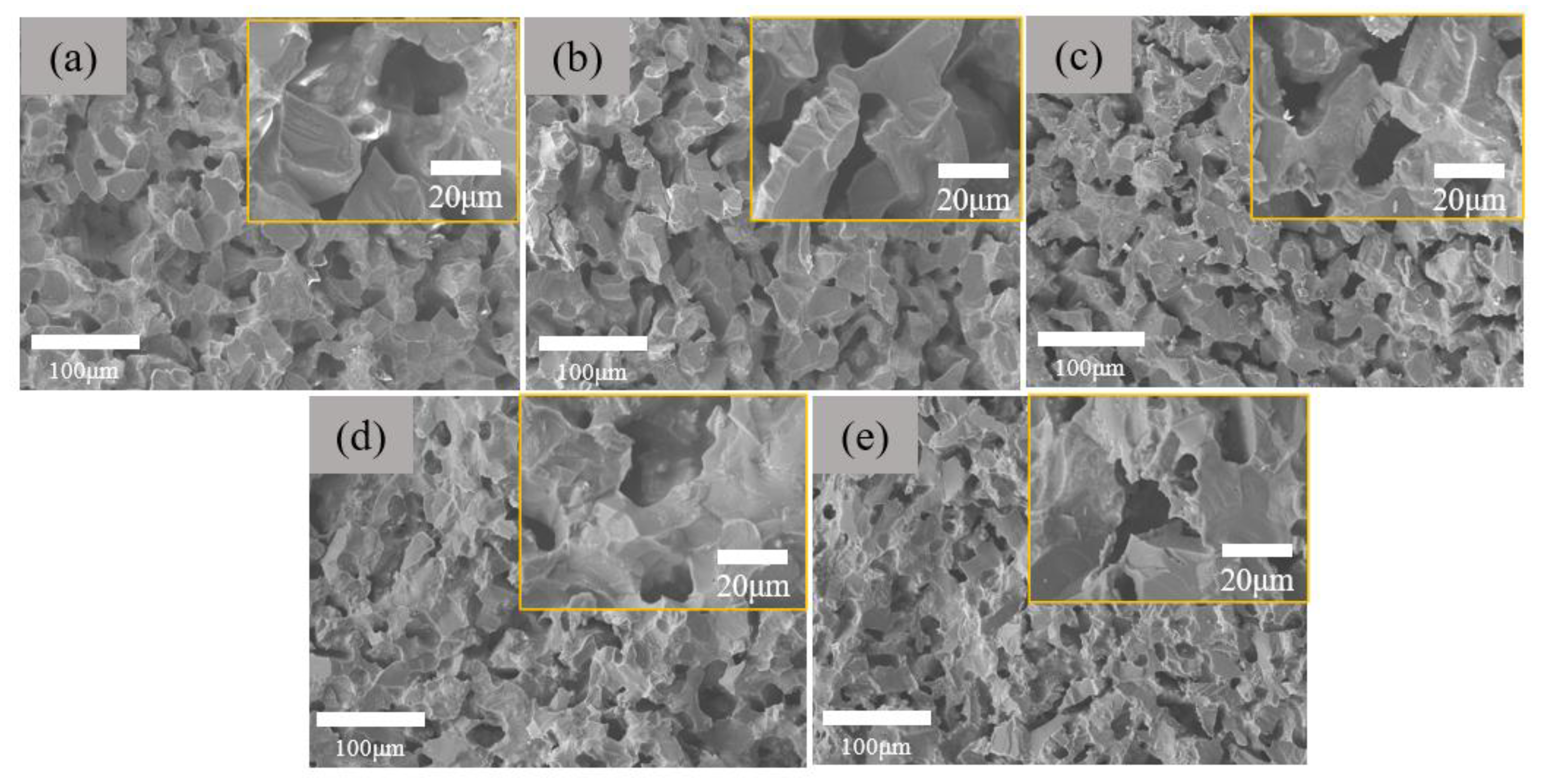

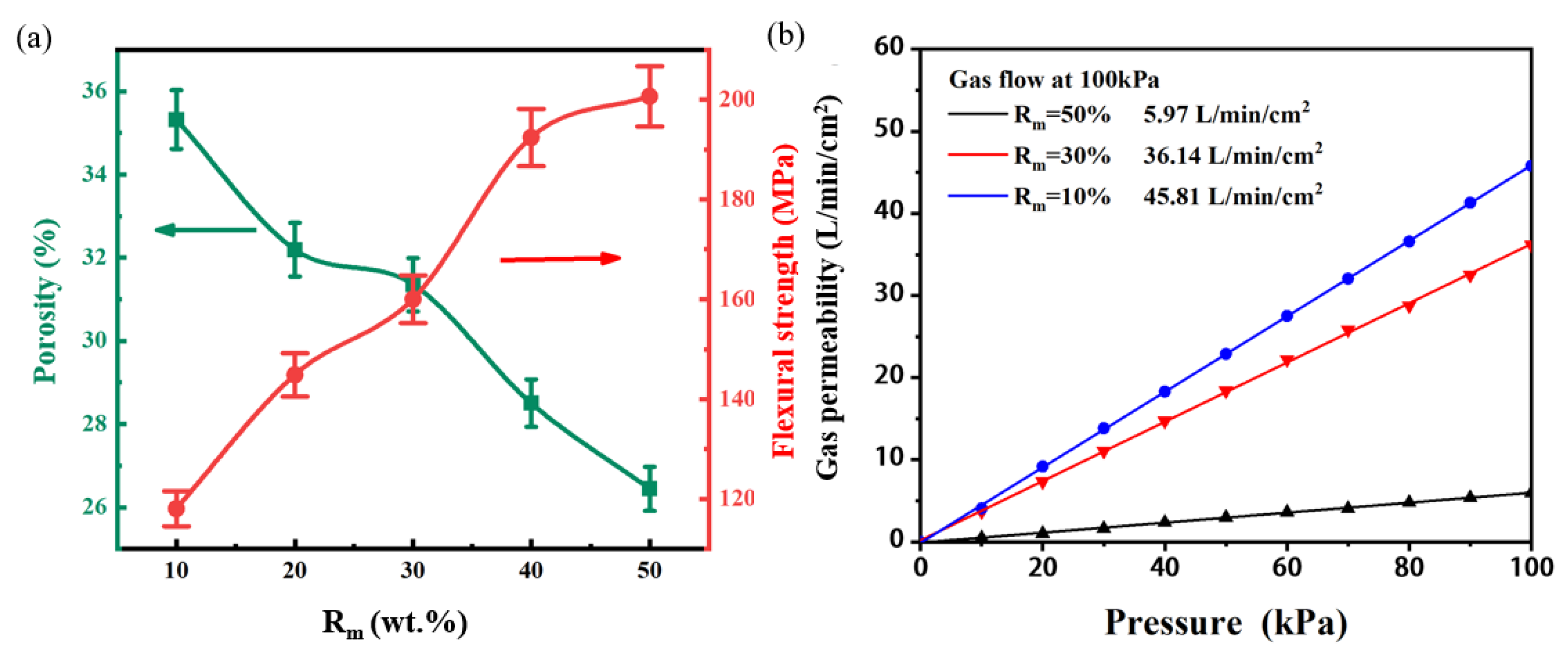

The morphologies of the inner structure of the as-prepared porous ceramics are shown in

Figure 4. Basically, the morphologies of all the samples are almost same. Careful investigation discloses that with the increase of Rm ratio from 10 wt.% to 50 wt.%, the pore size slightly decreases. The open porosity and flexural strength of the samples are shown in

Figure 5(a). As predicted, with the increase of the Rm, the open porosity decreases, while the flexural strength increases almost linearly. These results can be explained as follows: in the green bodies, the pores are directly formed due to the stacking of the large-size Al

2O

3 aggregates, while the α- Al

2O

3 micropowders, together with kaoling powders and sintering aids, acts as the pore fillings in the green body; therefore, with the increase of the content of α- Al

2O

3 micropowders, the pore size and porosity is decreased; Moreover, during the sintering stage, the Al

2O

3 aggregates are almost inert, while α- Al

2O

3 micropowders, kaoling powders and sintering aids tend to form liquid phase [

13,

14], facilitating the crystallization of Al

2O

3 phase, and hence improving the flexural strength. The gas permeability of the samples was further tested. As shown in

Figure 5 (b), the gas permeability decreases gradually with the Rm. This is in agreement of the result of the open porosity. It is found that when the Rm =30%, not only the porosity of the sample is higher than 30%, but also its flexural strength is nearly 160MPa, and the gas permeability reaches ~36 L/min/cm

2 at 100KPa. All of these data indicate its potential application for vacuum chuck.

3.3. Influence of Aggregate Size on the Morphological Structure and Properties of Through-Porous Ceramic Materials

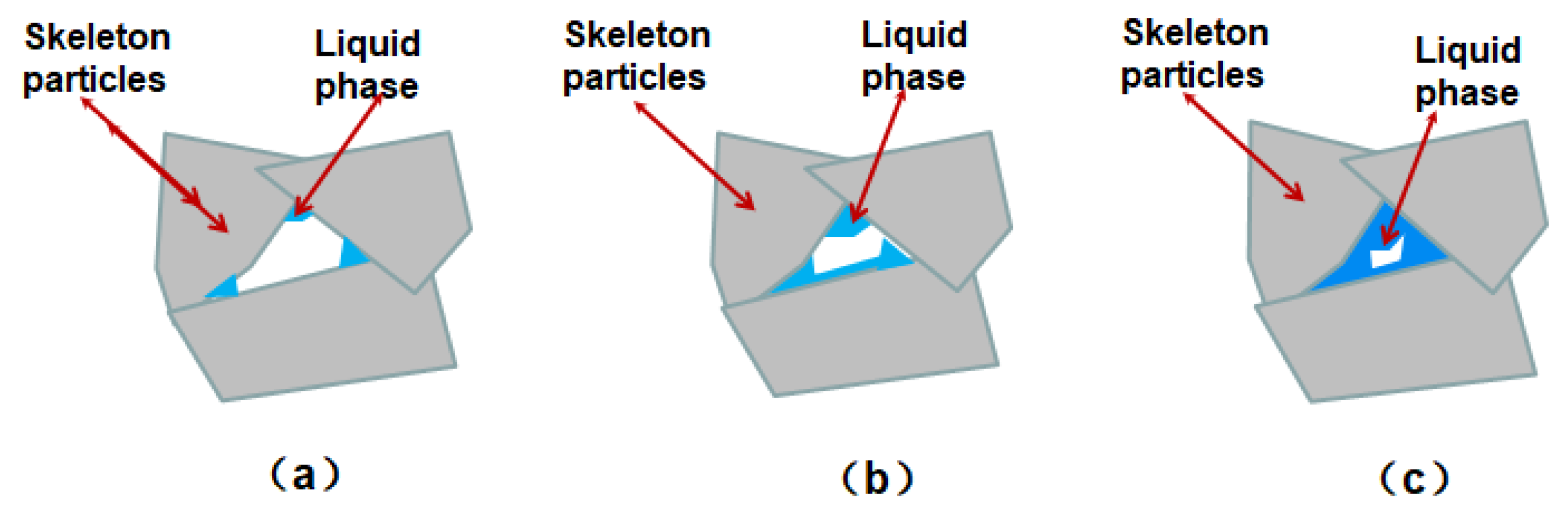

According to the above research results, the proportion of aggregate and matrix in powder are the key parameters to successfully build a porous ceramic with good performance and excellent pore structure when using the particle stacking method to prepare porous ceramic materials. However, how does the ratio of aggregate to matrix affect the bending strength? Because Al2O3 skeleton particles are inert during sintering, the formation of the pores will be related to the reaction of the filler material, including the activity α- Al2O3 powder, kaolin powder and sintering additives. It is well known that rare earth oxides of Y2O3 and La2O3 are good surface active substances. The addition of rare earth materials promotes the solid reaction between Al2O3 powder and the low melting point liquid phase. Therefore, two substances play an important role in the formation of pore structure during sintering: one is inert Al2O3 particles (skeleton particles), and the other is quasi-liquid phase.

Therefore, the effect of the ratio of aggregate to matrix in the powder on the strength of porous ceramics can be explained as follows: when the content of active α-Al

2O

3 powders is low, the quasi-liquid phase may not be completely formed. The liquid phase preferentially fills the sharp corners of adjacent skeleton particles, thus reducing the surface energy of the system, as shown in

Figure 6. However, because of the low-content of liquid, the connection of the aggregates is not of high strength, as indicated by

Figure 6(a). With the increase of matrix content, the material is consumed and transferred to more content of liquid phase, as shown in

Figure 6(b). Further increase of the amount of liquid phase will make the liquid phase tightly wrap and connect the skeleton Al

2O

3 powder, increasing its strength. However, the diameter of the hole caused by the adjacent skeleton Al

2O

3 particles will be decreased, as shown in

Figure 6 (c). Therefore, with the increase of Rm, the strength of ceramics is increased, but the permeability of the porous ceramic will decreased if two much liquid phase is introduced.

To further tune the pore structure of the porous ceramics, we prepared porous ceramics using Al

2O

3 aggregates of 200, 320, 600, and 1000 mesh (about 81.3, 51.8, 28.5, and 14.8μm), respectively.

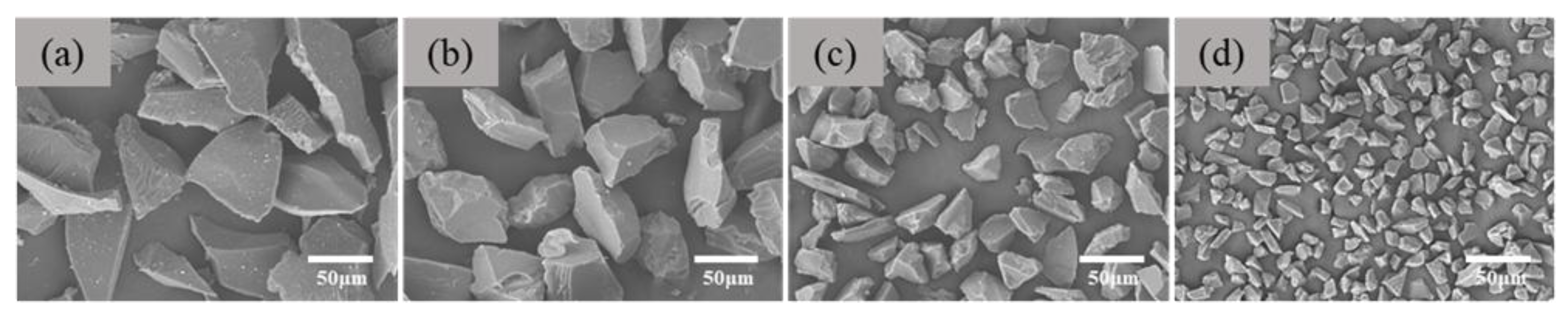

Figure 7 is the scanning electron microscope of white alumina aggregate with particle size of 200, 320, 600 and 1000 mesh.

Table 2 shows the statistical results of particle size. It can be found from the chart that the particle size distribution of the white corundum powder used is relatively uniform, and the particles are irregular. The larger the mesh number, the smaller the average size.

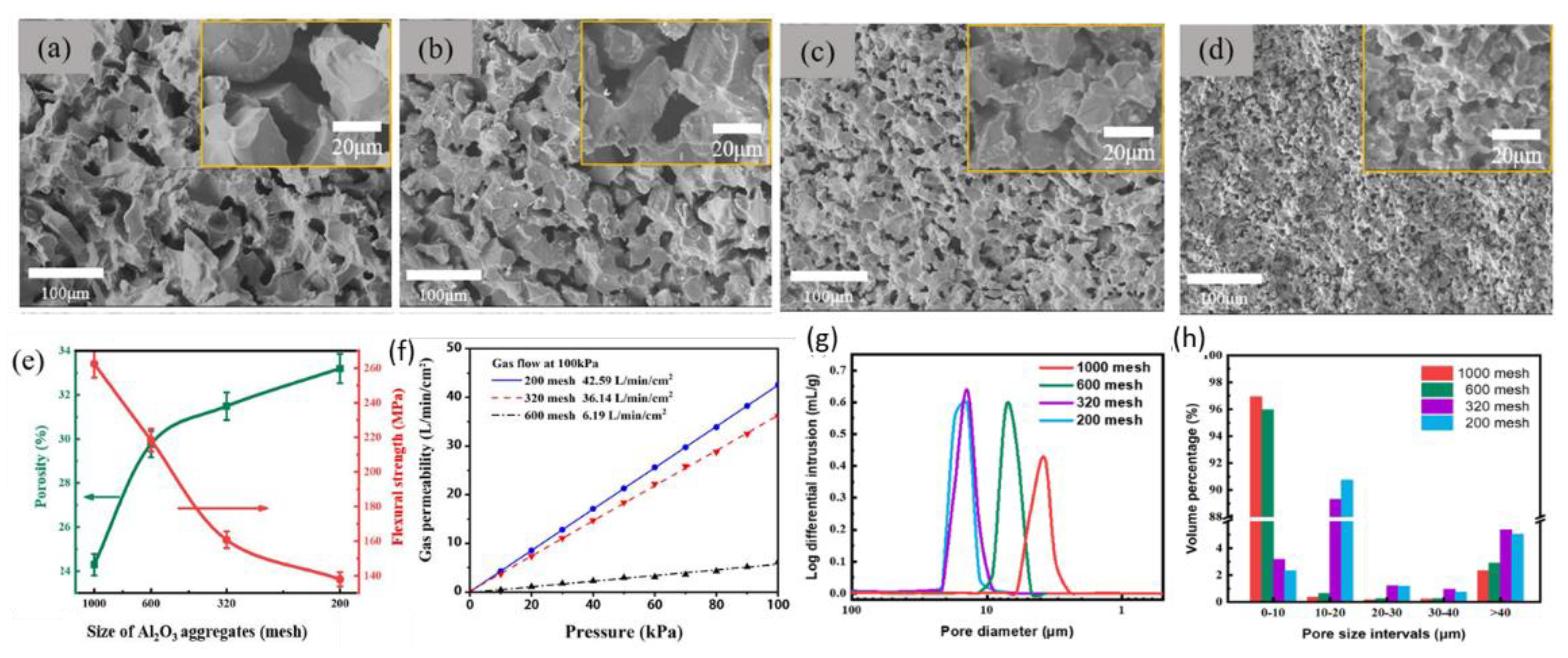

Using the Al

2O

3 aggregates with different size, the porous ceramics were prepared. The morphologies of the inner structure are shown in

Figure 8 (a-d), and their properties are shown in

Figure 8(e-h). With the size of Al

2O

3 aggregates decrease from 1000 mesh to 200 mesh, the pore size and porosity gradually decreases. Conversely, the flexural strength increases from ~140 MPa to ~260 MPa. The results of permeability shown in

Figure 8(f) indicate the permeability shows a negligible drop when Al

2O

3 aggregate size decrease from 200 mesh to 320 mesh, but shows dramatic drop from ~36 to ~6 L/min/cm

2 when the Al

2O

3 aggregate size decreases from 320 mesh to 600 mesh, which is related to the pore structure.

The pore structure of the samples was examined by an automatic mercury porosimeter. Their results are shown in

Figure 8 (g). The average pore size is about 15μm when 200 or 320 mesh aggregates are used. Decrease of the size of the aggregates to 600 and 1000 mesh leads to the average pore size of about 7μm and 4μm. The volume percentage of pores with different sizes is shown in

Figure 8 (h). For samples prepared using 600 and 1000mesh aggregates, the pores with size of 0~10μm take up the volume percentage of more than 95%, while for samples prepared using 200 and 320mesh aggregates, 90% of the volume percentage is taken up by pores with size of 10~20μm. These results explain the reason why the permeability is almost same when the size of Al

2O

3 aggregates decreases from 200 mesh to 320 mesh, but shows a dramatic drop when the size of Al

2O

3 aggregates decreases from 320 mesh to 600 mesh.

4. Conclusions

A novel and environment friendly gel casting method using carrageenan as gelling agent was developed to prepare porous ceramics. Especially, the idea of particle stacking is used to construct through-hole structure. The component raw materials including large size Al2O3 aggregates and active α-Al2O3 micropowders were concisely designed. The micropores were directly formed by stacking the large size Al2O3 aggregates during the sintering process. Assisted by the gel casting method, the loosely accumulated aggregate helps the formation of the through-hole structure. The filling materials of Al2O3 micropowders and sintering aids connected the Al2O3 aggregates and enhanced the flexural strength of the porous ceramics. By reasonable selection and optimization of the components in the slurry, porous Al2O3 based ceramics with porosity over 30%, gas permeability over 36 L/min/cm2, and high flexural strength of ~160MPa were obtained.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.C. and YQ.C.; methodology, ZP.W.; investigation, Z.C.; resources, Z.C.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.C.; writing—review and editing, YQ.C.; visualization, ZP.W.; supervision, YQ.C.; project administration, Z.C.; funding acquisition, Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Natural Science Basic Research Plan in Shaanxi Province of China (grant number 2021JQ-897), the Research Fund Project of Shaanxi Polytechnic Institute (No. 2024YKZX-014).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

References

- Du Z, Yao D, Xia Y, Zuo K, Yin J, Liang H and Zeng Y-P. 2020. Highly porous silica foams prepared via direct foaming with mixed surfactants and their sound absorption characteristics. Ceramics International. 46(9).pp.12942-12947. [CrossRef]

- Voigt C, Jäckel E, Taina F, Zienert T, Salomon A, Wolf G, Aneziris CG and Le Brun P. 2017. Filtration Efficiency of Functionalized Ceramic Foam Filters for Aluminum Melt Filtration. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B. 48(1).pp.497-505. [CrossRef]

- Zhou W, Yan W, Li N, Li Y, Dai Y, Zhang Z and Ma S. 2019. Fabrication of mullite-corundum foamed ceramics for thermal insulation and effect of micro-pore-foaming agent on their properties. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 785(1030-1037. [CrossRef]

- Hong Y, Wang Y, Li B and Pan G. 2019. Immobilizing nitrifying bacteria with Fe2O3-CaO-SiO2 porous glass-ceramics. International Journal of Applied Glass Science. 10(2).pp.228-234.

- Guo W, Hu T, Qin H, Gao P and Xiao H. 2021. Preparation and in situ reduction of Ni/SiCxOy catalysts supported on porous SiC ceramic for ethanol steam reforming. Ceramics International. 47(10, Part A).pp.13738-13744. [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Ha J-H, Lee J and Song I-H. 2016. Optimization for Permeability and Electrical Resistance of Porous Alumina-Based Ceramics. J Korean Ceram Soc. 53(5).pp.548-556. [CrossRef]

- Dong B, Yang M, Wang F, Hao L, Xu X, Wang G and Agathopoulos S. 2019. Porous Al2O3 plates prepared by combing foaming and gel-tape casting methods for efficient collection of oil from water. Chemical Engineering Journal. 370(658-665. [CrossRef]

- Xing Y, Deng J, Zhang K, Wang X, Lian Y and Zhou Y. 2015. Fabrication and dry cutting performance of Si3N4/TiC ceramic tools reinforced with the PVD WS2/Zr soft-coatings. Ceramics International. 41(8).pp.10261-10271. [CrossRef]

- Zhou J and Wang C-A. 2013. Porous yttria-Stabilized Zirconia Ceramics Fabricated by Nonaqueous-Based Gelcasting Process with PMMA Microsphere as Pore-Forming Agent. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 96(1).pp.266-271.

- Xia B, Wang Z, Gou L, Zhang M and Guo M. 2022. Porous mullite ceramics with enhanced compressive strength from fly ash-based ceramic microspheres: Facile synthesis, structure, and performance. Ceramics International. 48(8).pp.10472-10479. [CrossRef]

- Qi F, Xu X, Xu J, Wang Y and Yang J. 2014. A Novel Way to Prepare Hollow Sphere Ceramics. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 97(10).pp.3341-3347.

- Millán AJ, Moreno R and Nieto MaI. 2002. Thermogelling polysaccharides for aqueous gelcasting—part I: a comparative study of gelling additives. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 22(13).pp.2209-2215. [CrossRef]

- Yang Q, Zeng Z, Xu J, Zhang H and Ding J. 2006. Effect of La2O3 on Microstructure and Transmittance of Transparent Alumina Ceramics. Journal of Rare Earths. 24(1).pp.72-75. [CrossRef]

- Park CW and Yoon DY. 2000. Effects of SiO2, CaO2, and MgO Additions on the Grain Growth of Alumina. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 83(10).pp.2605-2609.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).