Submitted:

14 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

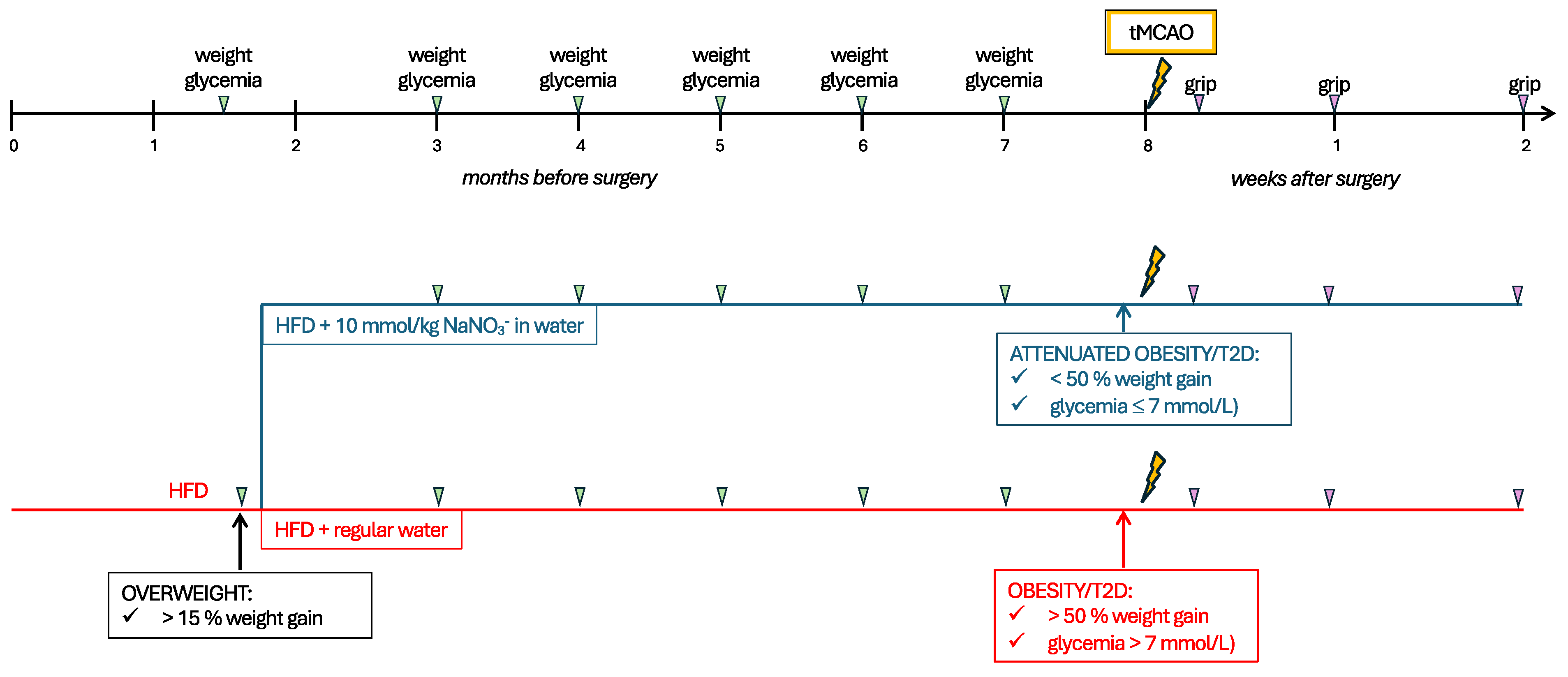

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Metabolic Assessments

2.4.1. Fasting Glycemia

2.4.2. Insulin Tolerance Test (ITT)

2.4.3. Glucose Tolerance Test (GTT)

2.5. Transient Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion

2.6. Behavioral Assessment

2.7. Tissue Collection

2.8. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

2.9. Analysis

2.9.1. Quantification of Infarct Size

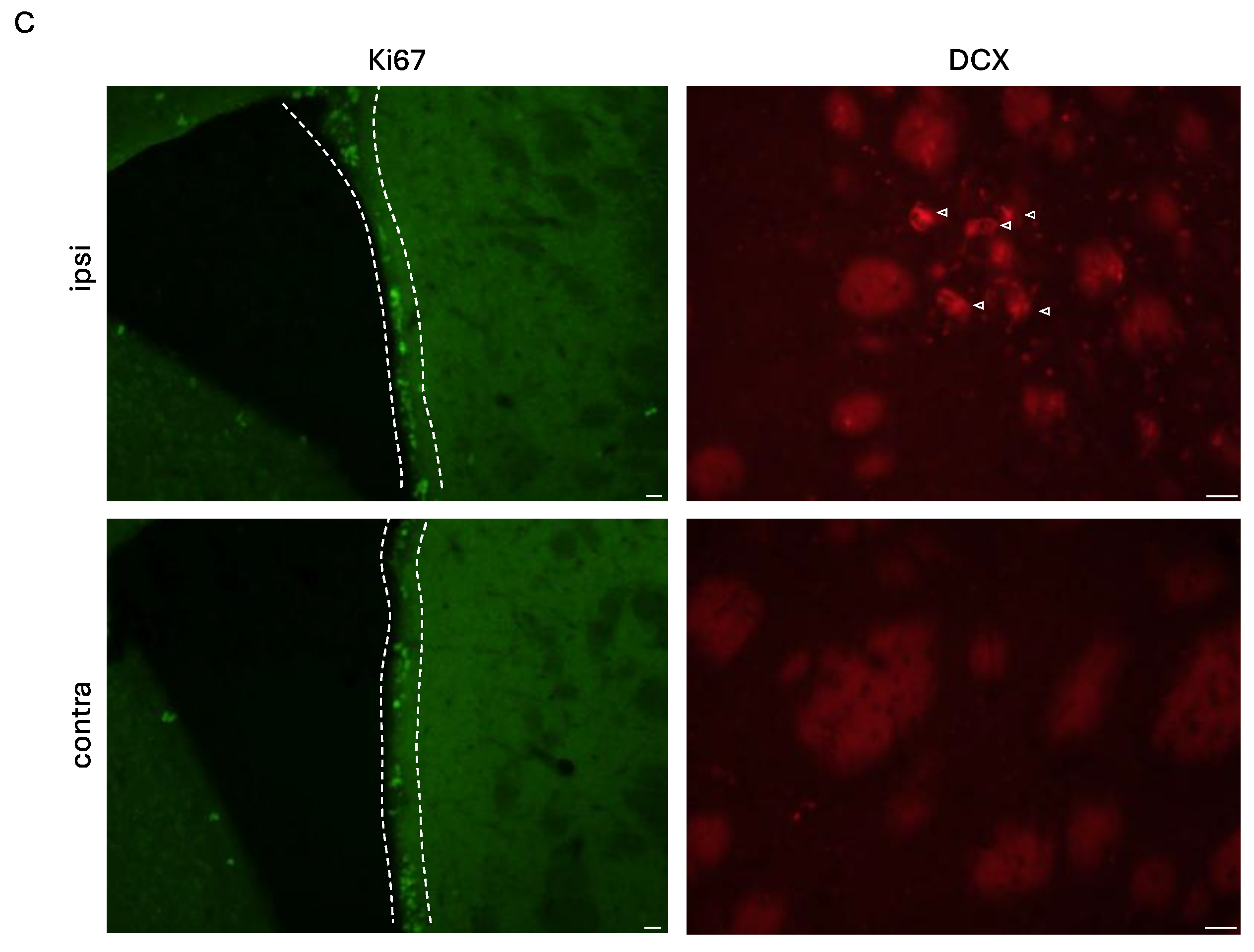

2.9.2. Quantification of Stroke-Induced Neural Stem Cell Proliferation (Ki67) and Early Neurogenesis (DCX)

2.9.3. Quantification of Neuroinflammation

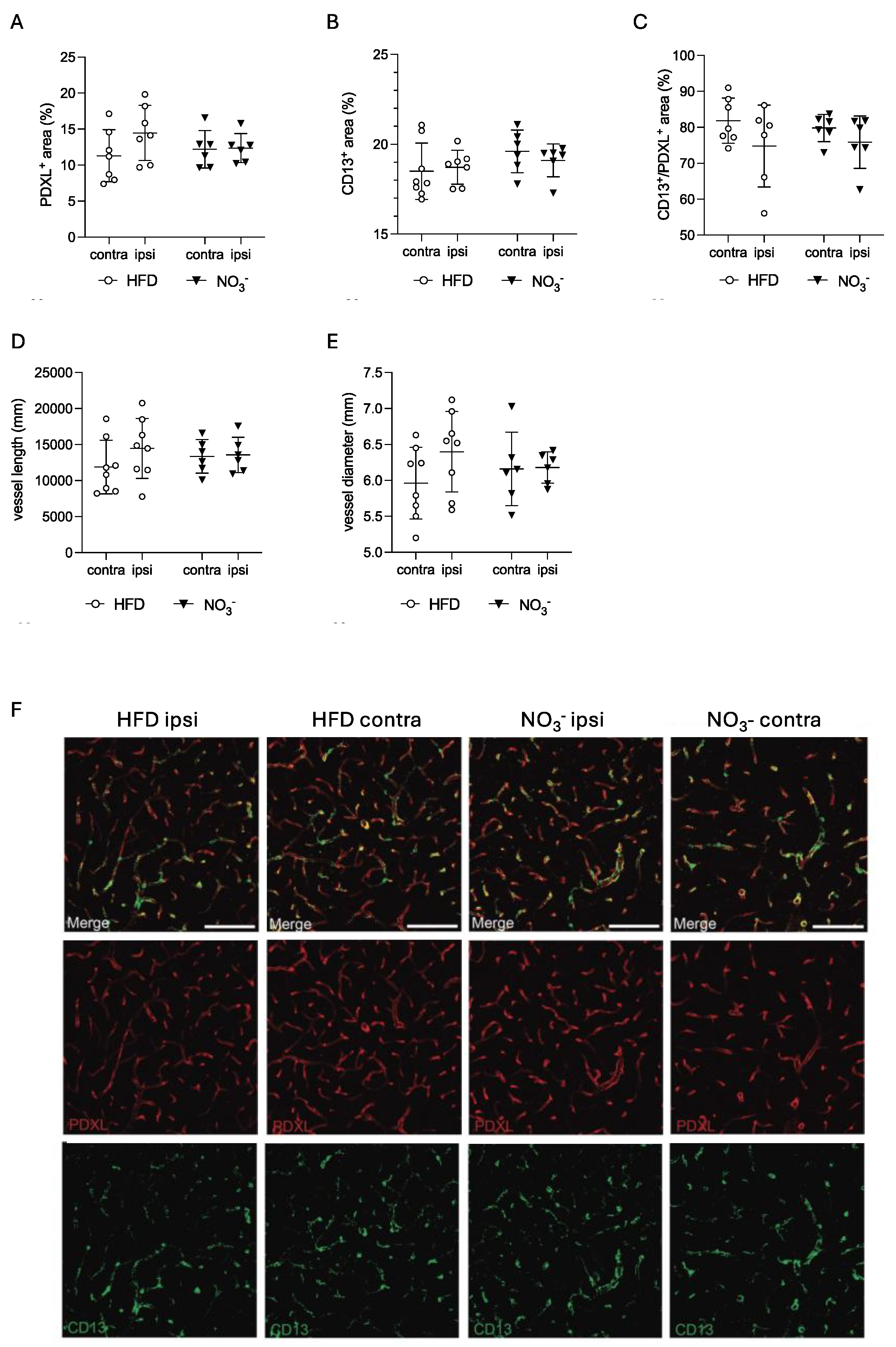

2.9.4. Quantification of Neovascularization

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

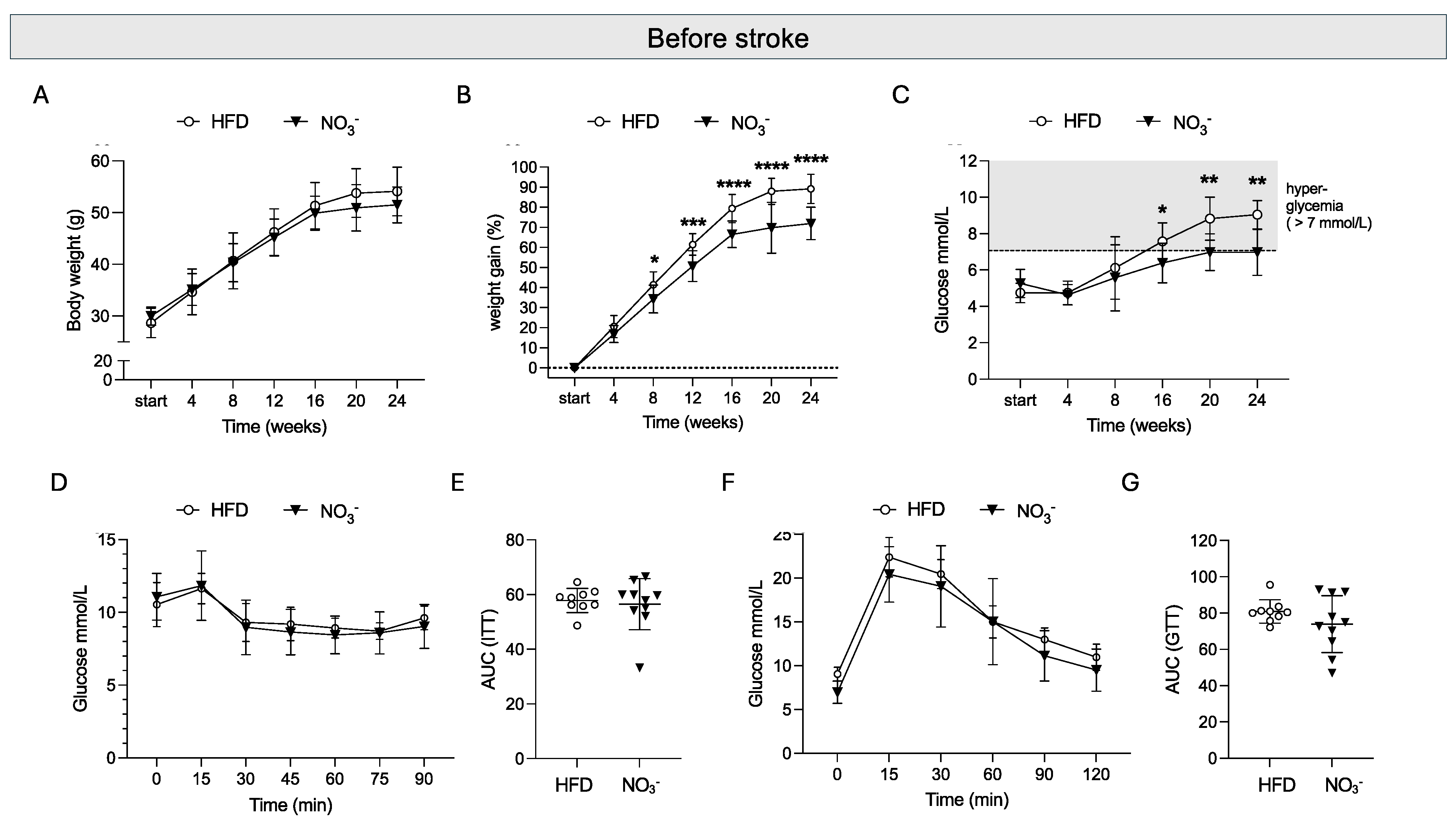

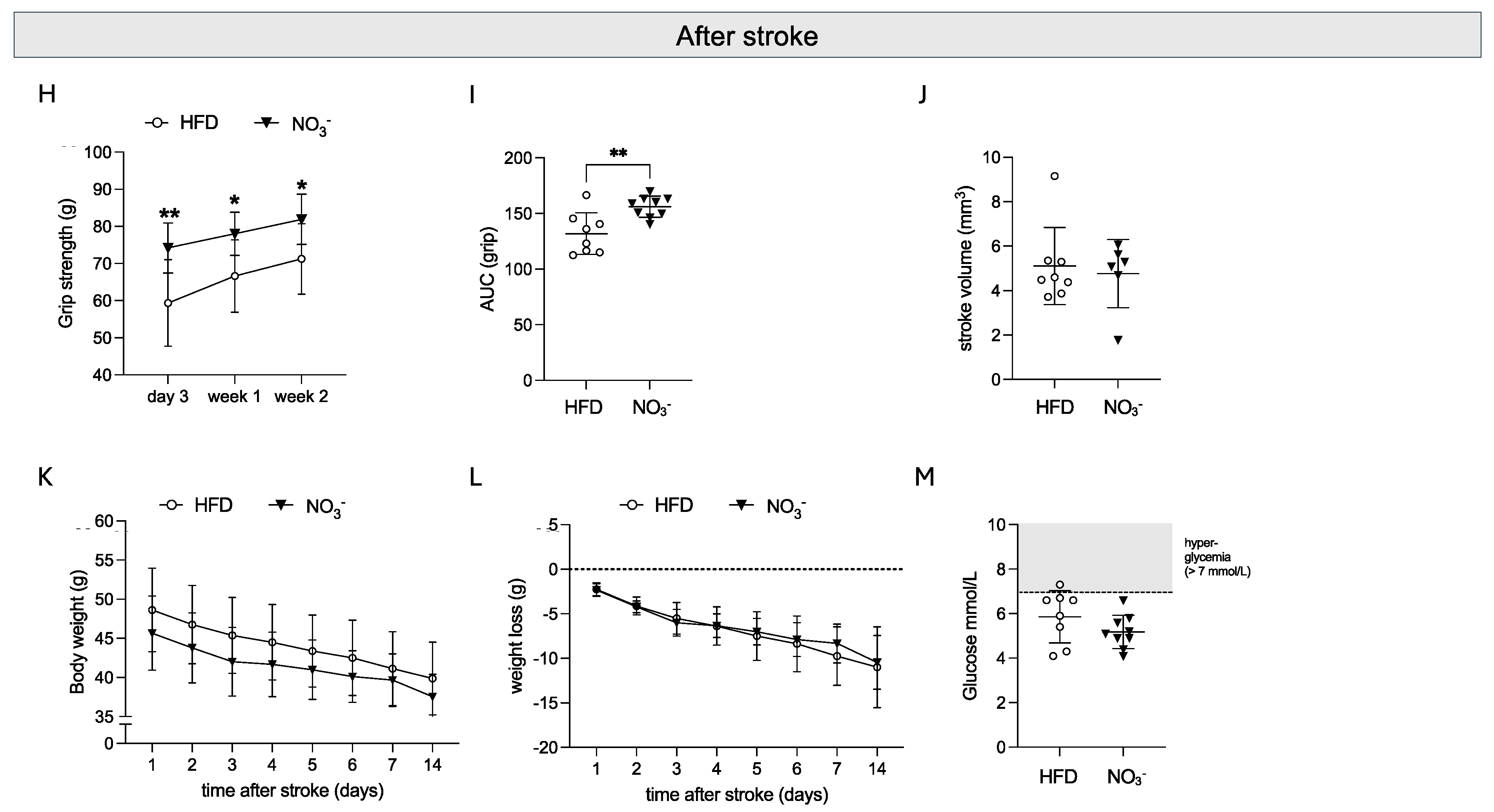

3.1. Sustained NO3- Supplementation in Overweight Mice Attenuates the Development of Obesity and Hyperglycemia and Improves Stroke Recovery

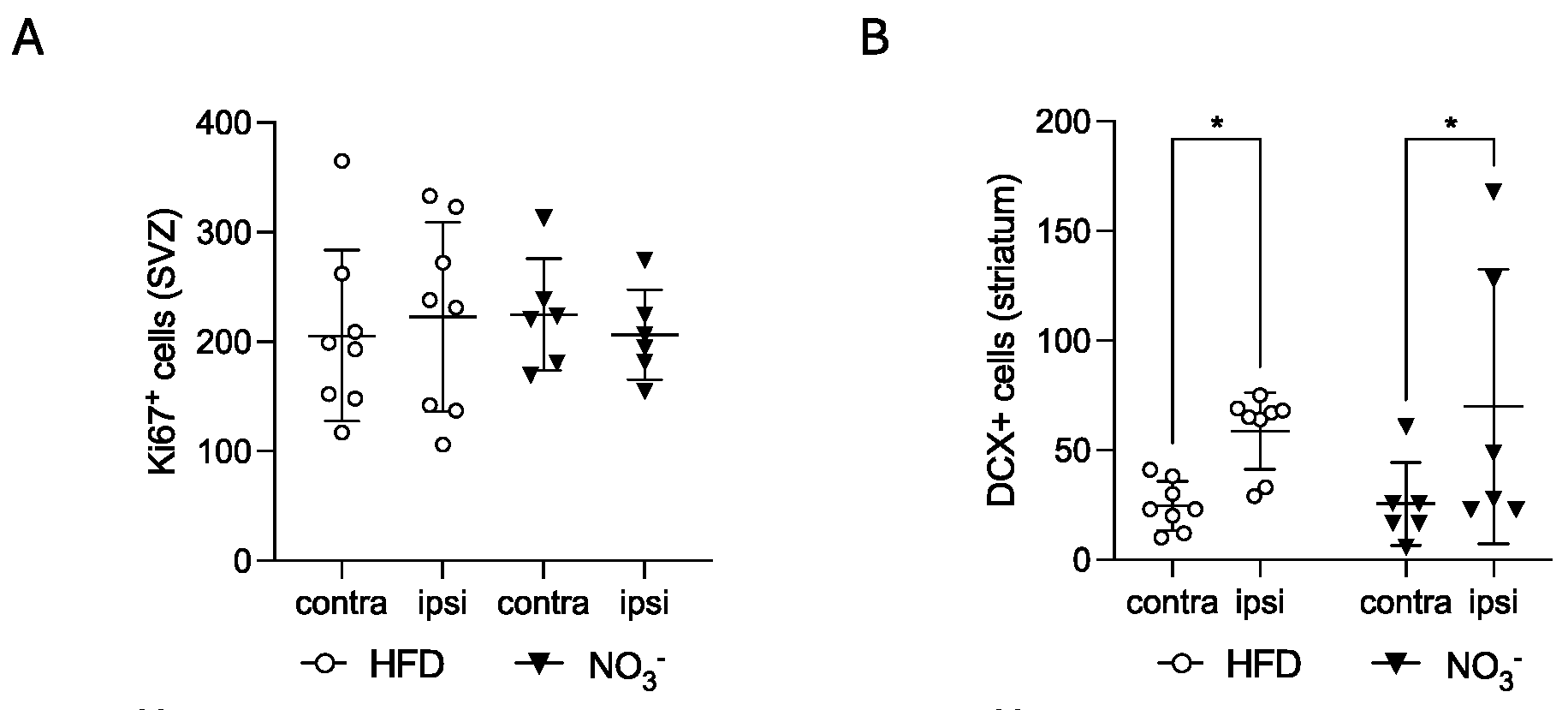

3.2. Improved Stroke Outcome in NO3- Mice Was Not Associated with Increased Stroke-Induced Early Neurogenesis

3.3. Improved Stroke Outcome in NO3- Mice Was Associated with Decreased Post-Stroke Inflammation

3.4. Improved Stroke Outcome in NO3- Mice Was Not Associated with Improved Post-Stroke Vascularization

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Competing Interests

References

- Eckel, R.H.; Alberti, K.G.M.M.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, P.Z. The metabolic syndrome. The Lancet 2010, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirode, G.; Wong, R.J. Trends in the Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in the United States, 2011-2016. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 2020, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, K.L.; Stafford, L.K.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Boyko, E.J.; Vollset, S.E.; Smith, A.E.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet. 2023, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.A.E.; Huxley, R.R.; Woodward, M. Diabetes as a risk factor for stroke in women compared with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts, including 775 385 individuals and 12 539 strokes. The Lancet. 2014, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullberg, T.; Zia, E.; Petersson, J.; Norrving, B. Changes in functional outcome over the first year after stroke: an observational study from the Swedish stroke register. Stroke. 2015, 46, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megherbi, S.E.; Milan, C.; Minier, D.; Couvreur, G.; Osseby, G.V.; Tilling, K.; et al. Association between diabetes and stroke subtype on survival and functional outcome 3 months after stroke: data from the European BIOMED Stroke Project. Stroke. 2003, 34, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braggio, M.; Dorelli, G.; Olivato, N.; Lamberti, V.; Valenti, M.T.; Dalle Carbonare, L.; et al. Tailored Exercise Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome: Cardiometabolic Improvements Beyond Weight Loss and Diet—A Prospective Observational Study. Nutrients. 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muszalska, A.; Wiecanowska, J.; Michałowska, J.; Pastusiak-Zgolińska, K.M.; Polok, I.; Łompieś, K.; et al. The Role of the Planetary Diet in Managing Metabolic Syndrome and Cardiovascular Disease: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahrani, A.A.; Morton, J. Benefits of weight loss of 10% or more in patients with overweight or obesity: A review. Obesity 2022, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernan, W.N.; Inzucchi, S.E. Treating Diabetes to Prevent Stroke. Stroke 2021, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghusn, W.; De La Rosa, A.; Sacoto, D.; Cifuentes, L.; Campos, A.; Feris, F.; et al. Weight Loss Outcomes Associated with Semaglutide Treatment for Patients with Overweight or Obesity. JAMA Netw Open. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.J.; Goodwin Cartwright, B.M.; Gratzl, S.; Brar, R.; Baker, C.; Gluckman, T.J.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Semaglutide and Tirzepatide for Weight Loss in Adults with Overweight and Obesity in the US: A Real-World Evidence Study. medRxiv. 2023.

- Abdel-Bary, M.; Brody, A.; Schmitt, J.; Prieto, K.; Wetzel, A.; Juo, Y.Y. Treating class 2–3 obesity with glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists: A 2-year real-world cohort study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Guh, D.P.; Zhang, W.; Bansback, N.; Amarsi, Z.; Birmingham, C.L.; Anis, A.H. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, G.A.; Horberg, M.; Koebnick, C.; Young, D.R.; Waitzfelder, B.; Sherwood, N.E.; et al. Cardiometabolic risk factors among 1.3 million adults with overweight or obesity, but not diabetes, in 10 geographically diverse regions of the United States, 2012-2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domosławska-Żylińska, K.; Łopatek, M.; Krysińska-Pisarek, M.; Sugay, L. Barriers to Adherence to Healthy Diet and Recommended Physical Activity Perceived by the Polish Population. J Clin Med. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.D.; Kahan, S. Maintenance of Lost Weight and Long-Term Management of Obesity. Medical Clinics of North America 2018, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheibi, S.; Jeddi, S.; Carlström, M.; Gholami, H.; Ghasemi, A. Effects of long-term nitrate supplementation on carbohydrate metabolism, lipid profiles, oxidative stress, and inflammation in male obese type 2 diabetic rats. Nitric Oxide. 2018, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleli, M.; Ferreira, D.M.S.; Tarnawski, L.; McCann Haworth, S.; Xuechen, L.; Zhuge, Z.; et al. Dietary nitrate attenuates high-fat diet-induced obesity via mechanisms involving higher adipocyte respiration and alterations in inflammatory status. Redox Biol. 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Luo, M.; Tian, R.; Lu, N. Dietary nitrate attenuated endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E knockout mice fed a high-fat diet: A critical role for NADPH oxidase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2020, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlström, M.; Larsen, F.J.; Nyström, T.; Hezel, M.; Borniquel, S.; Weitzberg, E.; et al. Dietary inorganic nitrate reverses features of metabolic syndrome in endothelial nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010, 107, 17716–17720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Carlström, M.; Weitzberg, E. Metabolic Effects of Dietary Nitrate in Health and Disease. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E. Nitric oxide signaling in health and disease. Cell. 2022, 185, 2853–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendra, A.; Bondonno, N.P.; Murray, K.; Zhong, L.; Rainey-Smith, S.R.; Gardener, S.L.; et al. Habitual dietary nitrate intake and cognition in the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle Study of ageing: A prospective cohort study. Clinical Nutrition. 2023, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wightman, E.L.; Haskell-Ramsay, C.F.; Thompson, K.G.; Blackwell, J.R.; Winyard, P.G.; Forster, J.; et al. Dietary nitrate modulates cerebral blood flow parameters and cognitive performance in humans: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover investigation. Physiol Behav. 2015, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Crom, T.O.E.; Blekkenhorst, L.; Vernooij, M.W.; Ikram, M.K.; Voortman, T. ; IkramMA. Dietary nitrate intake in relation to the risk of dementia and imaging markers of vascular brain health: a population-based study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2023, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, K.H.; Chu, K.; Ko, S.Y.; Lee, S.T.; Sinn, D.I.; Park, D.K.; et al. Early intravenous infusion of sodium nitrite protects brain against in vivo ischemia-reperfusion injury. Stroke. 2006, 37, 2744–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. Nitrate Metabolism and Ischemic Cerebrovascular Disease: A Narrative Review. Front Neurol. 7351, 13, 735181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, P.D.; Tzeng, Y.C.; Gowing, E.K.; Clarkson, A.N.; Fan, J.L. Dietary nitrate supplementation reduces low frequency blood pressure fluctuations in rats following distal middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Appl Physiol. 2018, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, H.; Huang, P.L.; Panahian, N.; Fishman, M.C.; Moskowitz, M.A. Reduced brain edema and infarction volume in mice lacking the neuronal isoform of nitric oxide synthase after transient MCA occlusion. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism. 1996, 16, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pintana, H.; Lietzau, G.; Augestad, I.L.; Chiazza, F.; Nyström, T.; Patrone, C.; et al. Obesity-induced type 2 diabetes impairs neurological recovery after stroke in correlation with decreased neurogenesis and persistent atrophy of parvalbumin-positive interneurons. Clin Sci (Lond). 2019, 133, 1367–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bederson, J.B.; Pitts, L.H.; Tsuji, M.; Nishimura, M.C.; Davis, R.L.; Bartkowski, H. Rat middle cerebral artery occlusion: evaluation of the model and development of a neurologic examination. Stroke. 1986, 17, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunderland, A.; Tinson, D.; Bradley, L.; Hewer, R.L. Arm function after stroke. An evaluation of grip strength as a measure of recovery and a prognostic indicator. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989, 52, 1267–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, G.D.; Harry, J.D. Brain volume estimation from serial section measurements: a comparison of methodologies. J Neurosci Methods. 1990, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercalsteren, E.; Karampatsi, D.; Buizza, C.; Nyström, T.; Klein, T.; Paul, G.; et al. The SGLT2 inhibitor Empagliflozin promotes post-stroke functional recovery in diabetic mice. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arganda-Carreras, I.; Fernández-González, R.; Muñoz-Barrutia, A.; Ortiz-De-Solorzano, C. 3D reconstruction of histological sections: Application to mammary gland tissue. Microsc Res Tech. 2010, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria, A.S.; Roy, B.; Victoria, L.H. Development of an ImageJ-based method for analysing the developing zebrafish vasculature. Vasc Cell. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Elfarnawany, M.H. Signal Processing Methods for Quantitative Power Doppler Microvascular Angiography. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2015.

- Teplyi, V.; Grebchenko, K. Evaluation of the scars’ vascularization using computer processing of the digital images. Skin Research and Technology. 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lu, M.; LaPointe, M.; et al. A nitric oxide donor induces neurogenesis and reduces functional deficits after stroke in rats. Ann Neurol. 2001, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceanga, M.; Dahab, M.; Witte, O.W.; Keiner, S. Adult Neurogenesis and Stroke: A Tale of Two Neurogenic Niches. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, V.; Shakya, A.K.; Perez-Pinzon, M.A.; Dave, K.R. Cerebral ischemic damage in diabetes: An inflammatory perspective. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durafourt, B.A.; Moore, C.S.; Zammit, D.A.; Johnson, T.A.; Zaguia, F.; Guiot, M.C.; et al. Comparison of polarization properties of human adult microglia and blood-derived macrophages. Glia. 2012, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, H.; Riese, S.; Régnier-Vigouroux, A. Functional characterization of mannose receptor expressed by immunocompetent mouse microglia. Glia. 2003, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Ohgidani, M.; Hata, N.; Inamine, S.; Sagata, N.; Shirouzu, N.; et al. CD206 Expression in Induced Microglia-Like Cells From Peripheral Blood as a Surrogate Biomarker for the Specific Immune Microenvironment of Neurosurgical Diseases Including Glioma. Front Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, M.; Ninomiya, I.; Hatakeyama, M.; Takahashi, T.; Shimohata, T. Microglia and monocytes/macrophages polarization reveal novel therapeutic mechanism against stroke. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammos, C.; Luedike, P.; Hendgen-Cotta, U.; Rassaf, T. Potential of dietary nitrate in angiogenesis. World J Cardiol. 2015, 7, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidder, S.; Webb, A.J. Vascular effects of dietary nitrate (as found in green leafy vegetables and beetroot) via the nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013, 75, 677–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Wang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, X.; Bu, L.; Pang, B.; et al. Dietary nitrate protects skin flap against ischemia injury in rats via enhancing blood perfusion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elabi, O.F.; Karampatsi, D.; Vercalsteren, E.; Lietzau, G.; Nyström, T.; Klein, T.; et al. DPP-4 Inhibitor and Sulfonylurea Differentially Reverse Type 2 Diabetes-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Leakage and Normalize Capillary Pericyte Coverage. Diabetes. 2023, 72, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, R.; Li, W.; Qu, Z.; Johnson, M.A.; Fagan, S.C.; Ergul, A. Vascularization pattern after ischemic stroke is different in control versus diabetic rats: relevance to stroke recovery. Stroke. 2013, 44, 2875–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskar, S. Impact of obesity-induced type 2 diabetes on long-term outcomes following stroke. Clin Sci (Lond). 2019, 133, 1603–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sanossian, N.; Starkman, S.; Avila-Rinek, G.; Eckstein, M.; Sharma, L.K.; et al. Adiposity and Outcome After Ischemic Stroke: Obesity Paradox for Mortality and Obesity Parabola for Favorable Functional Outcomes. Stroke. 2021, 52, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Gong, S.; Zhu, J.; Fang, Q. Relationships between obesity and functional outcome after ischemic stroke: a Mendelian randomization study. Neurological Sciences. 2024, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.R.; Serra, M.C.; McGrath, R.P. Obesity and diabetes are jointly associated with functional disability in stroke survivors. Disabil Health J. 2020, 13, 100914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.O. Novel aspects of dietary nitrate and human health. Annu Rev Nutr. 2013, 33, 129–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Gladwin, M.T.; Ahluwalia, A.; Benjamin, N.; Bryan, N.S.; Butler, A.; et al. Nitrate and nitrite in biology, nutrition and therapeutics. In Nature Chemical Biology; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Group, D.P.P.R. Reduction in the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes with Lifestyle Intervention or Metformin - NEJMoa012512. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002, 346. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan, D.M.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Crandall, J.P.; Edelstein, S.L.; Goldberg, R.B.; Horton, E.S.; et al. Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: The Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Association of the magnitude of weight loss and changes in physical fitness with long-term cardiovascular disease outcomes in overweight or obese people with type 2 diabetes: a post-hoc analysis of the Look AHEAD randomised clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4.

- Lai, M.; Chandrasekera, P.C.; Barnard, N.D. You are what you eat, or are you? the challenges of translating high-fat-fed rodents to human obesity and diabetes. Nutrition and Diabetes 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buettner, R.; Schölmerich, J.; Bollheimer, L.C. High-fat Diets: Modeling the Metabolic Disorders of Human Obesity in Rodents. Obesity. 2007, 15, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speakman, J.R. Use of high-fat diets to study rodent obesity as a model of human obesity. Int J Obes [Internet]. 2019, 43, 1491–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabung, F.K.; Satija, A.; Fung, T.T.; Clinton, S.K.; Giovannucci, E.L. Long-term change in both dietary insulinemic and inflammatory potential is associated with weight gain in adult women and men. Journal of Nutrition. 2019, 149, 804–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero-Herrera, I.; Kozyra, M.; Zhuge, Z.; Haworth, S.M.C.; Moretti, C.; Peleli, M.; et al. AMP-activated protein kinase activation and NADPH oxidase inhibition by inorganic nitrate and nitrite prevent liver steatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higaki, Y.; Hirshman, M.F.; Fujii, N.; Goodyear, L.J. Nitric oxide increases glucose uptake through a mechanism that is distinct from the insulin and contraction pathways in rat skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2001, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.C.; Tabima, D.M.; Dube, J.J.; Hughan, K.S.; Vanderpool, R.R.; Goncharov, D.A.; et al. SIRT3-AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Activation by Nitrite and Metformin Improves Hyperglycemia and Normalizes Pulmonary Hypertension Associated with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation. 2016, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masrur, S.; Cox, M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Smith, E.E.; Ellrodt, G.; Fonarow, G.C.; et al. Association of acute and chronic hyperglycemia with acute ischemic stroke outcomes post-thrombolysis: Findings from get with the guidelines-stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamouchi, M.; Matsuki, T.; Hata, J.; Kuwashiro, T.; Ago, T.; Sambongi, Y.; et al. Prestroke glycemic control is associated with the functional outcome in acute ischemic stroke: The fukuoka stroke registry. Stroke. 2011, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.Y.; Kim, W.J.; Kwon, J.H.; Kim, B.J.; Kim, J.T.; Lee, J.; et al. Prestroke glucose control and functional outcome in patients with acute large vessel occlusive stroke and diabetes after thrombectomy. Diabetes Care. 2021, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siervo, M.; Babateen, A.; Alharbi, M.; Stephan, B.; Shannon, O. Dietary nitrate and brain health. Too much ado about nothing or a solution for dementia prevention? British Journal of Nutrition 2022, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veszelovszky, E.; Holford, N.H.G.; Thomsen, L.L.; Knowles, R.G.; Baguley, B.C. Plasma nitrate clearance in mice: modeling of the systemic production of nitrate following the induction of nitric oxide synthesis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1995, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grefkes, C.; Grefkes, C.; Fink, G.R.; Fink, G.R. Recovery from stroke: Current concepts and future perspectives. Neurological Research and Practice 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ospel, J.M.; Hill, M.D.; Menon, B.K.; Demchuk, A.; McTaggart, R.; Nogueira, R.; et al. Strength of association between infarct volume and clinical outcome depends on the magnitude of infarct size: Results from the ESCAPE-NA1 trial. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2021, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraj, R.L.; Azimullah, S.; Beiram, R.; Jalal, F.Y.; Rosenberg, G.A. Neuroinflammation: friend and foe for ischemic stroke. J Neuroinflammation. 2019, 16, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Imagama, S.; Ohgomori, T.; Hirano, K.; Uchimura, K.; Sakamoto, K.; et al. Minocycline selectively inhibits M1 polarization of microglia. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvig, I.; Augestad, I.L.; Håberg, A.K.; Sandvig, A. Neuroplasticity in stroke recovery. The role of microglia in engaging and modifying synapses and networks. European Journal of Neuroscience 2018, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.T.; Dorman, L.C.; Pan, S.; Vainchtein, I.D.; Han, R.T.; Nakao-Inoue, H.; et al. Microglial Remodeling of the Extracellular Matrix Promotes Synapse Plasticity. Cell. 2020, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alia, C.; Cangi, D.; Massa, V.; Salluzzo, M.; Vignozzi, L.; Caleo, M.; et al. Cell-to-Cell Interactions Mediating Functional Recovery after Stroke. Cells. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolla, M.J.; Liebeskind, D.S.; Chan, S.L. The importance of comorbidities in ischemic stroke: Impact of hypertension on the cerebral circulation. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2018, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.L.; O’Donnell, T.; Lanford, J.; Croft, K.; Watson, E.; Smyth, D.; et al. Dietary nitrate reduces blood pressure and cerebral artery velocity fluctuations and improves cerebral autoregulation in transient ischemic attack patients. J Appl Physiol. 2020, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).