Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

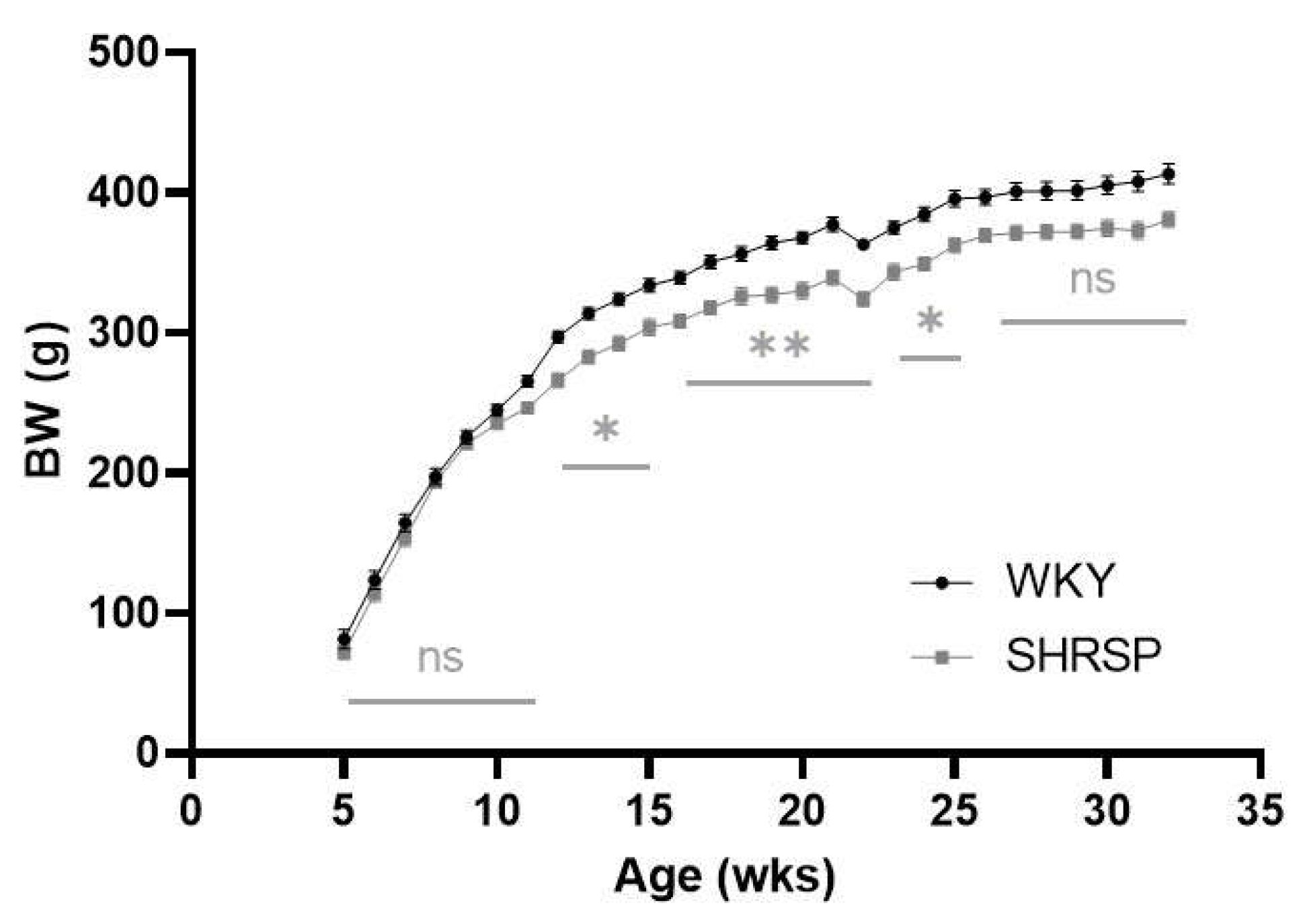

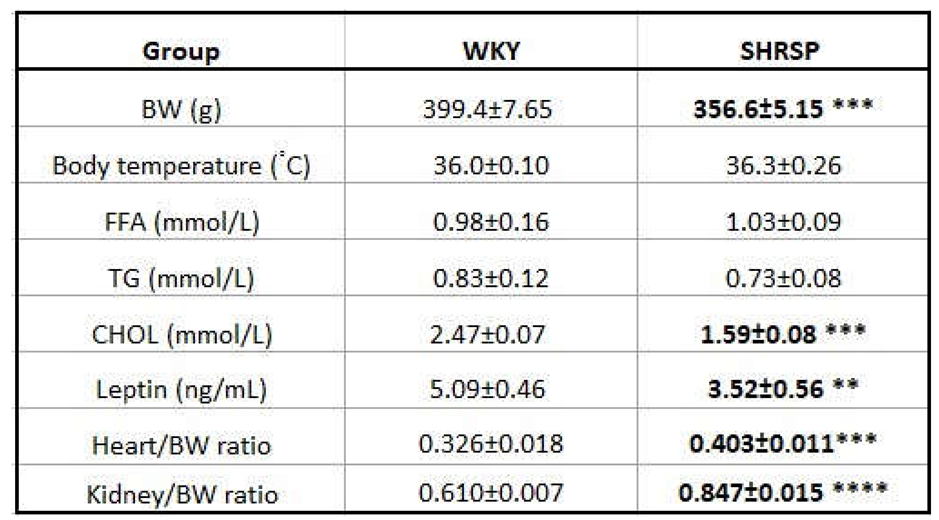

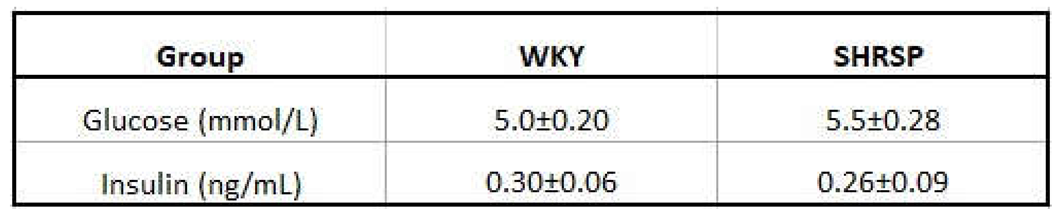

2.1. Morphometric and Metabolic Parameters

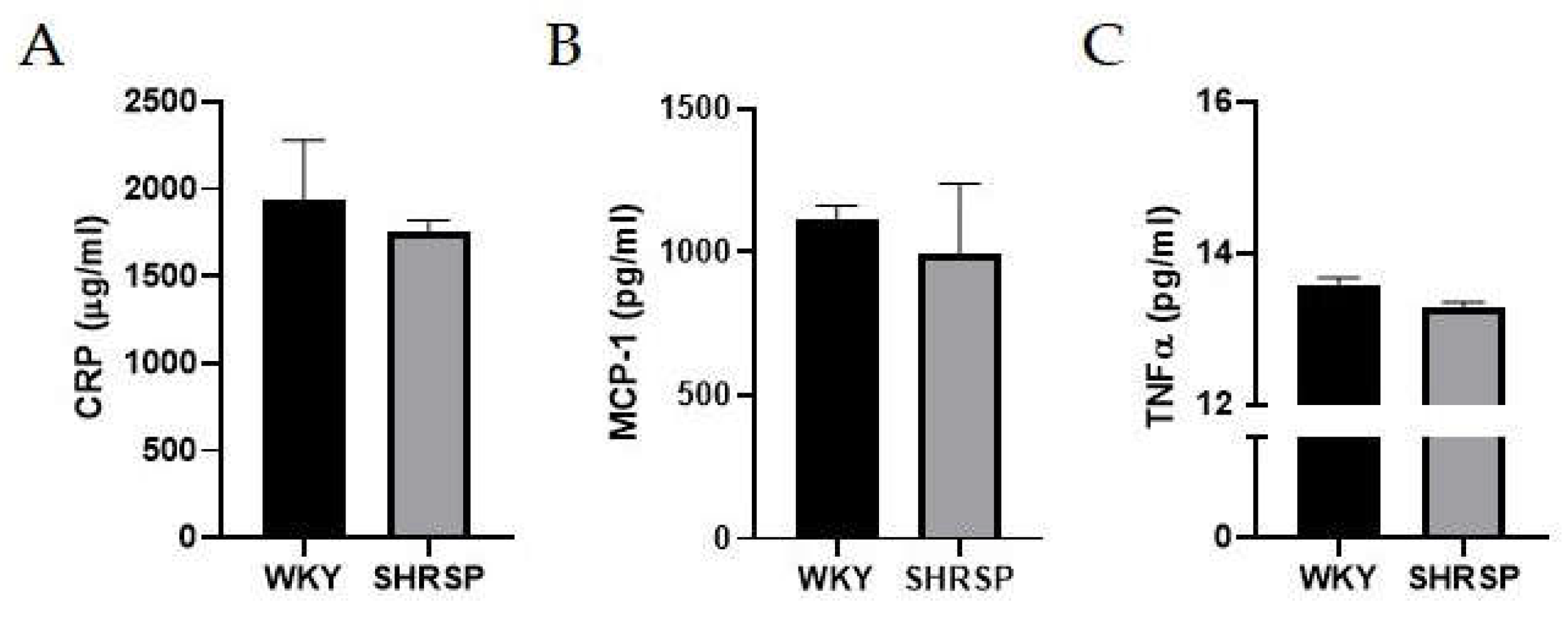

2.2. No Mark of Peripheral Inflammation

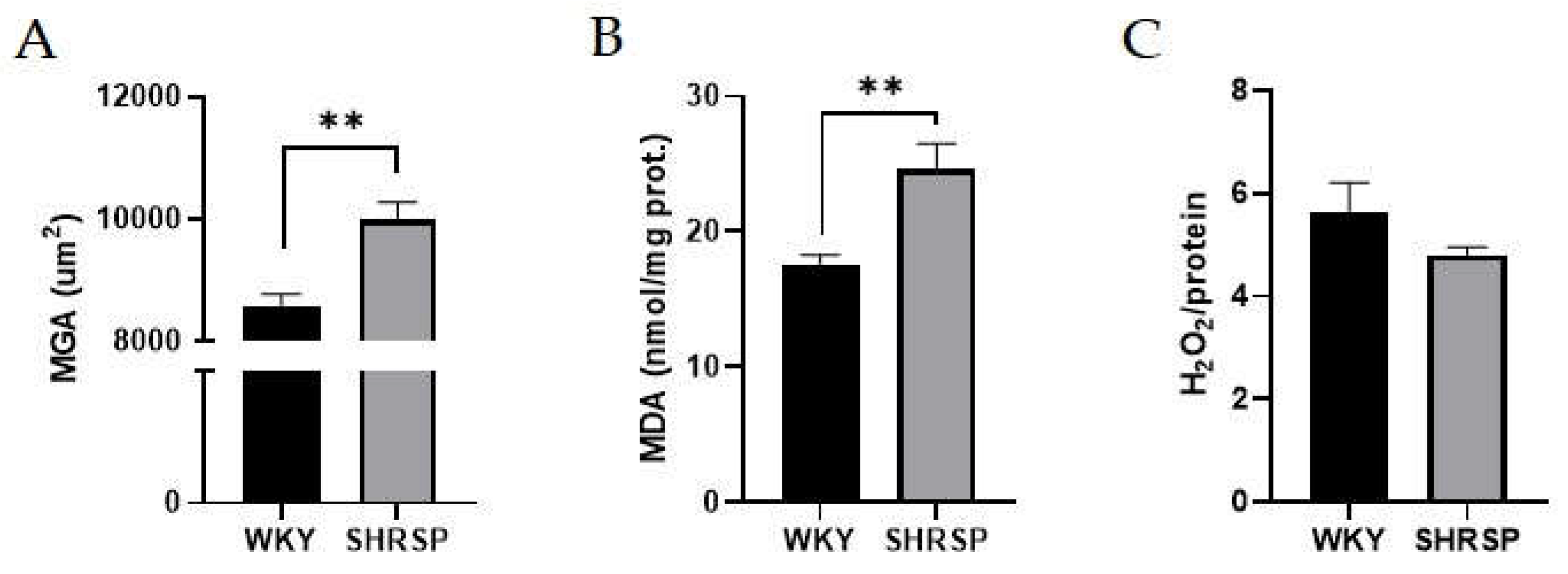

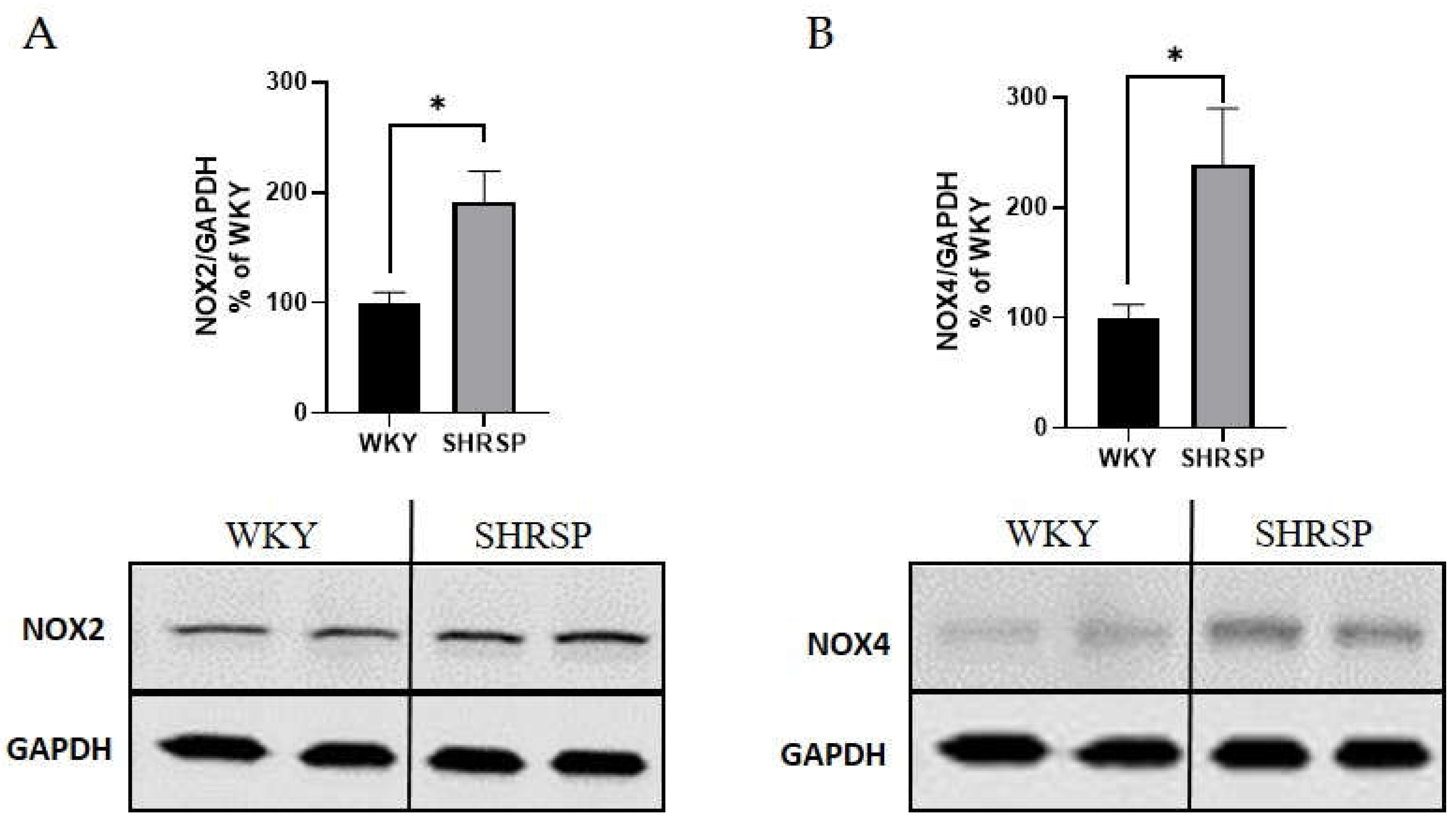

2.3. Signs of Oxidative Stress in the Kidney and Heart

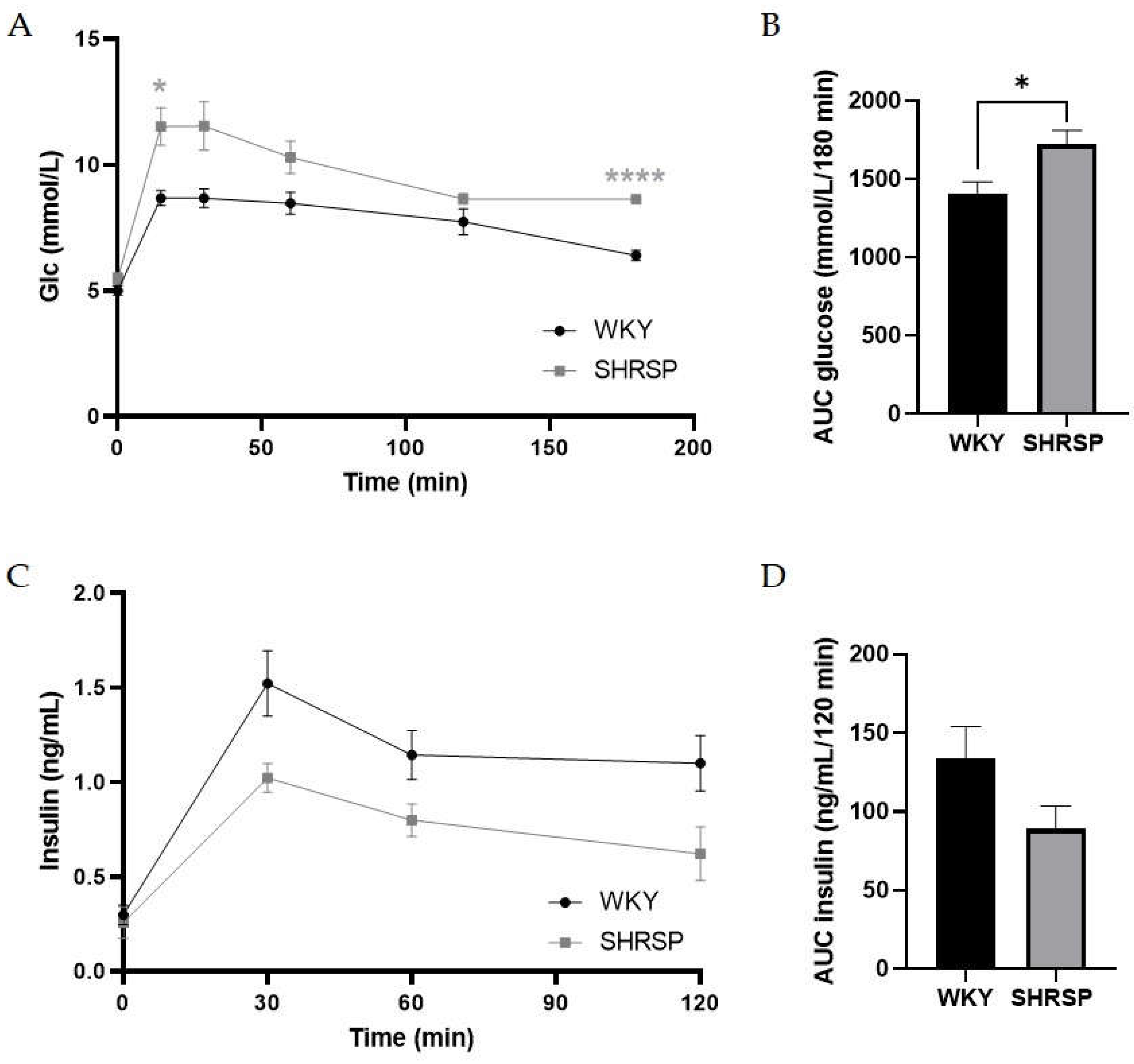

2.4. SHRSP Rats Had Mild Glucose Intolerance

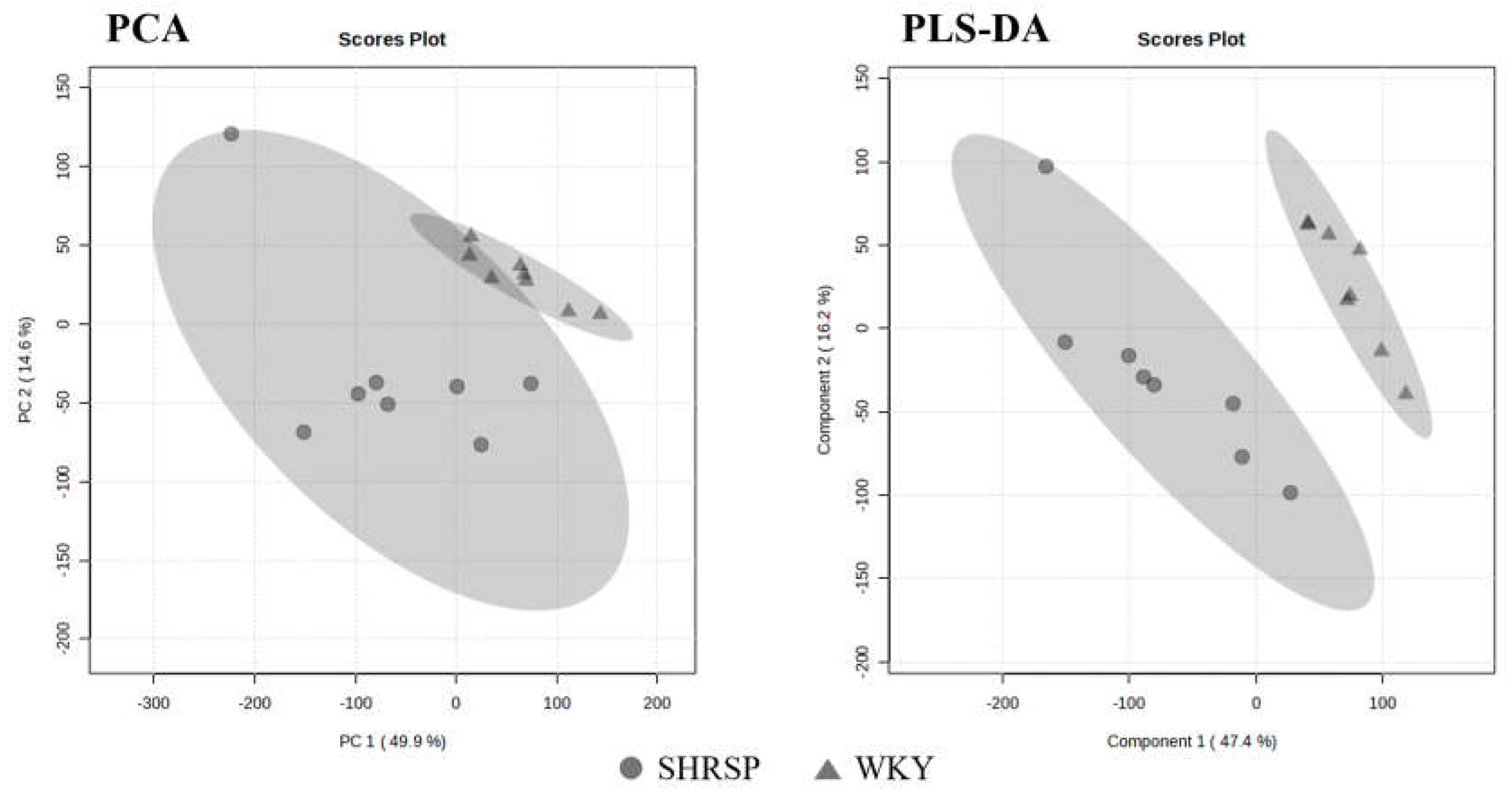

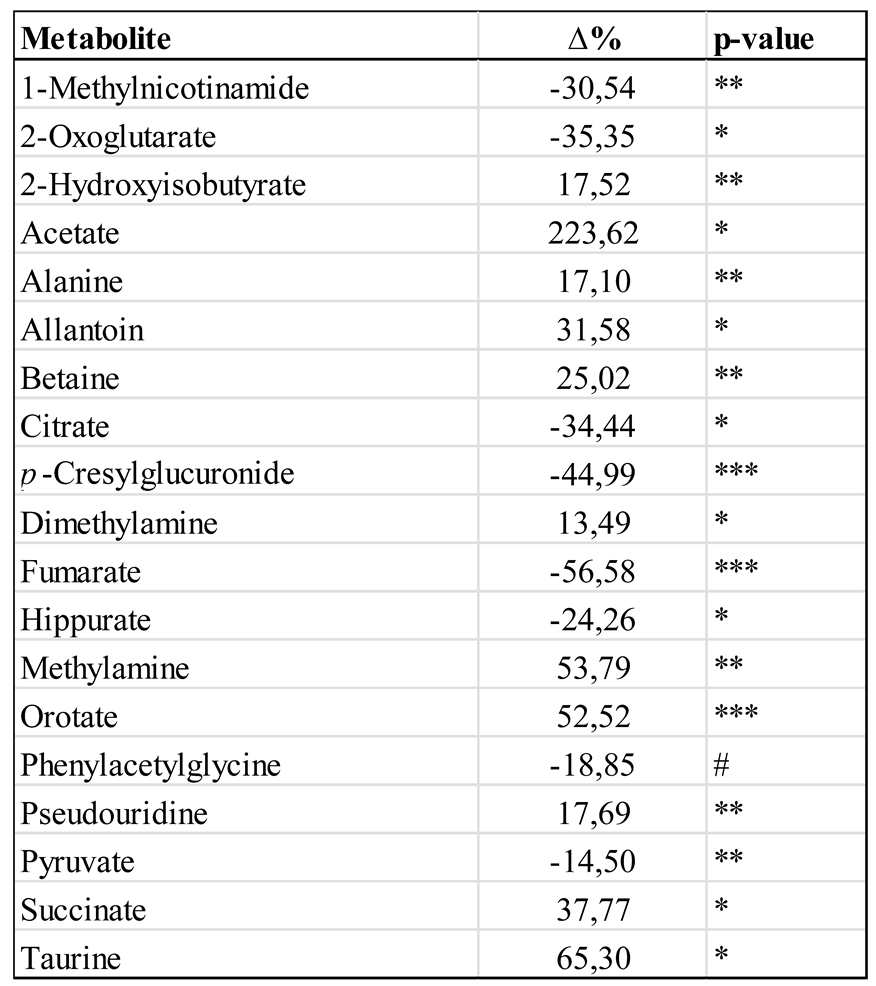

2.5. The NMR-Based Metabolomics in Urine

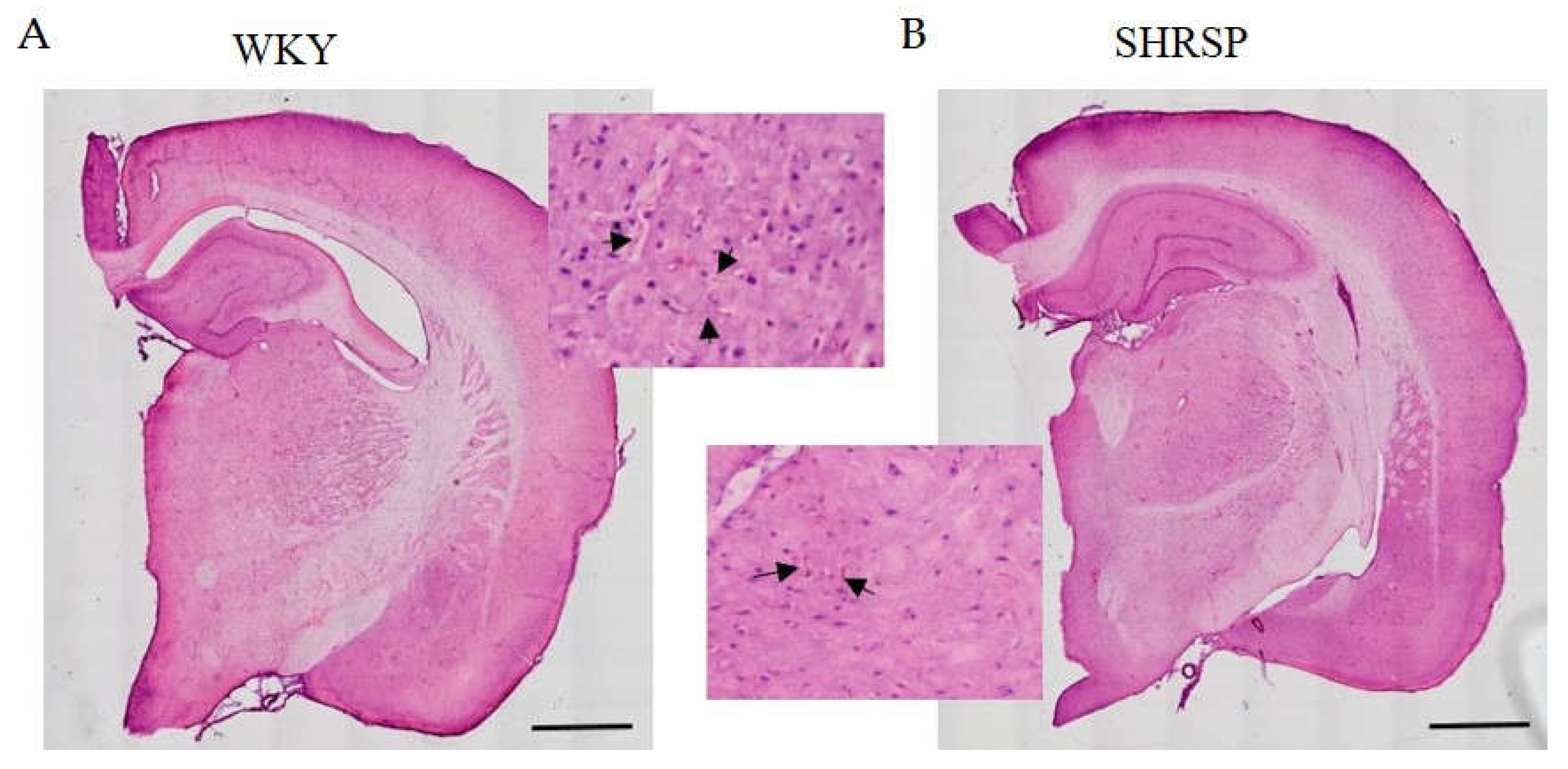

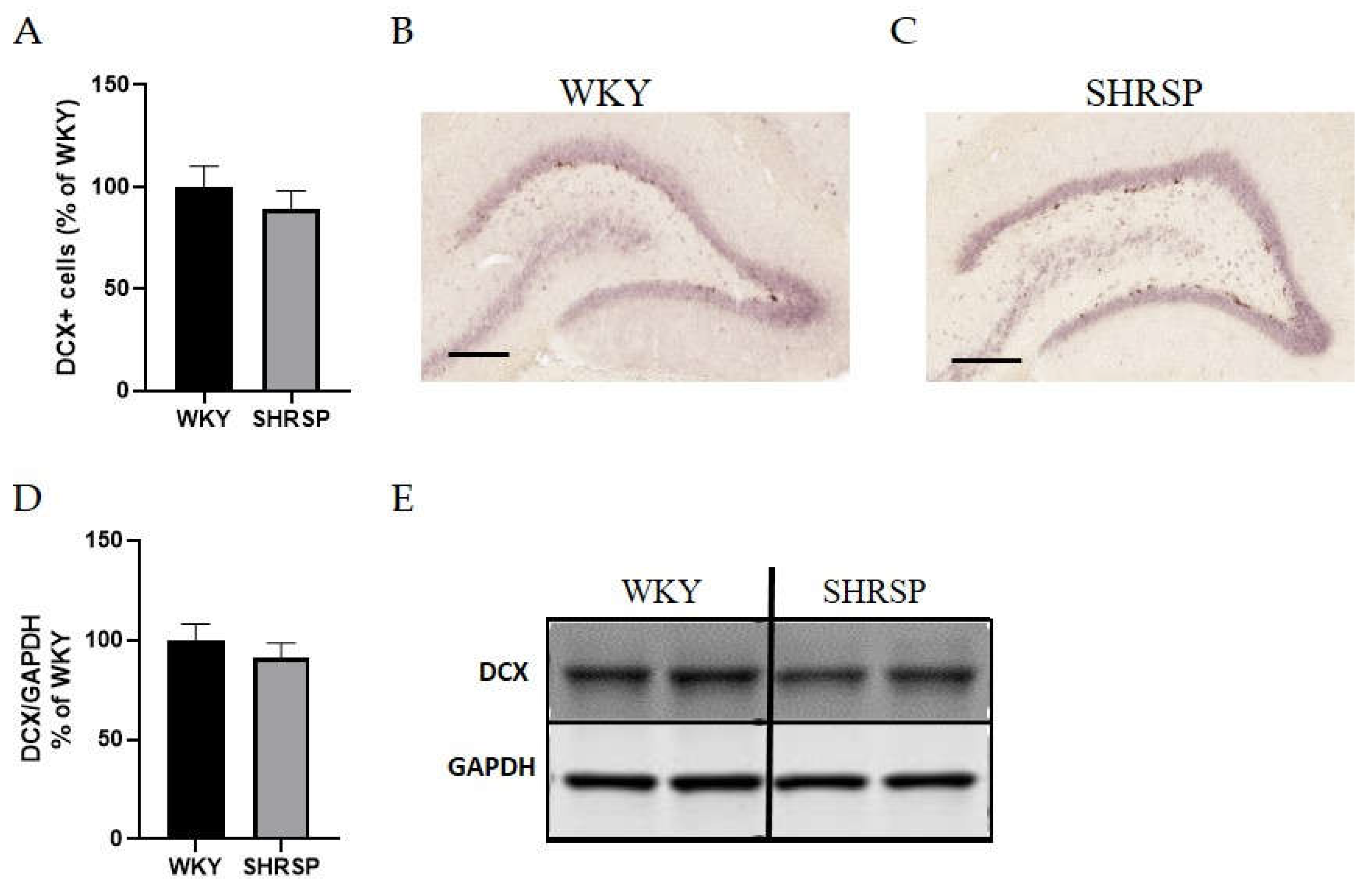

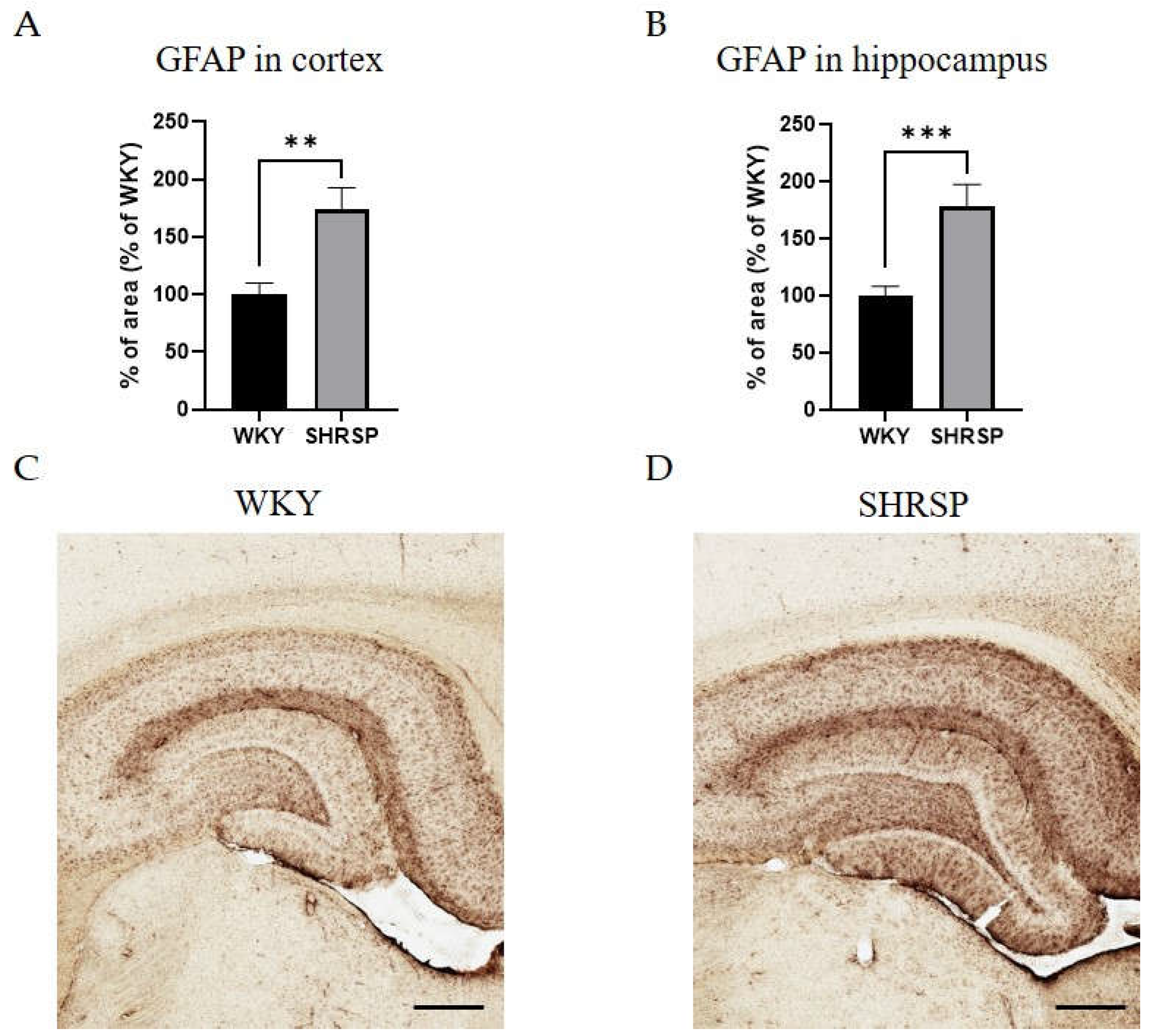

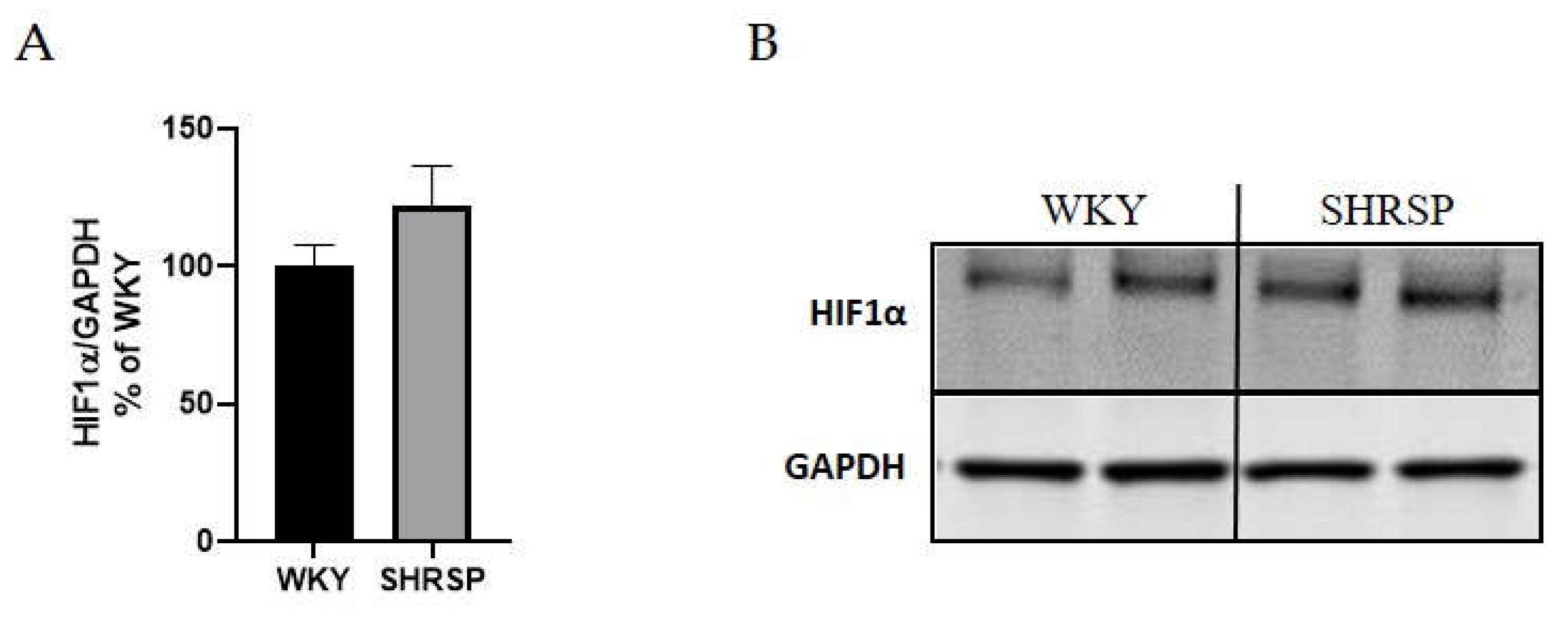

2.6. Brain Biochemistry, Histology and Immunohistochemistry

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. The Experimental Design

4.3. Oral Glucose Tolerance Test

4.4. Determination of Biochemical Parameters

4.5. NMR-Based Metabolomics in Urine

4.6. Western Blot Analysis

4.7. Measurement of Lipid Peroxidation

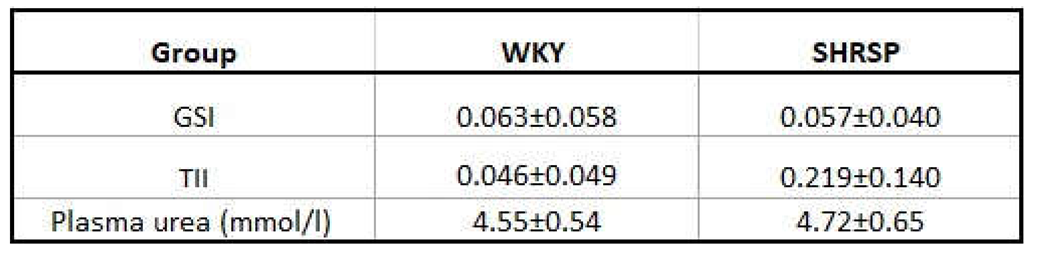

4.8. Kidney Histological Evaluation

4.9. Immunohistochemistry and Brain Histology

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AQP4 | Aquaporin-4 |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| BW | Body weight |

| CHOL | Total cholesterol |

| Col IV | Collagen type IV |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CSVD | Cerebral small vessel disease |

| DCX | Doublecortin |

| EGTA | Egtazic acid |

| FFA | Free fatty acids |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| GFR | Glomerular filtration rate |

| GSI | Glomerulosclerosis index |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| HE | Hematoxylin-eosin staining |

| HIF1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MGA | Mean glomerular area |

| NADPH | Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NOX1-4 | NADPH oxidase 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| OGTT | Oral glucose tolerance test |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| PMSF | Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluorid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SHRSP | Stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances |

| TCA cycle | Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| TII | Tubulointerstitial injury |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| WKY | Wistar-Kyoto rats |

References

- Okamoto, K %J Circ Res. "Establishment of the Stroke-Prone Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat (Shr)." 34 (1974): " I-143"-" I-53".

- Schrader, J.M.; Stanisavljevic, A.; Xu, F.; E Van Nostrand, W. Distinct Brain Proteomic Signatures in Cerebral Small Vessel Disease Rat Models of Hypertension and Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 81, 731–745. [CrossRef]

- Kroll, D. S., D. E. Feldman, C. L. Biesecker, K. L. McPherson, P. Manza, P. V. Joseph, N. D. Volkow, and G. J. Wang. "Neuroimaging of Sex/Gender Differences in Obesity: A Review of Structure, Function, and Neurotransmission." Nutrients 12, no. 7 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ineichen, B. V., P. Sati, T. Granberg, M. Absinta, N. J. Lee, J. A. Lefeuvre, and D. S. Reich. "Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Multiple Sclerosis Animal Models: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and White Paper." Neuroimage Clin 28 (2020): 102371. [CrossRef]

- Iadecola, C.; Gottesman, R.F. Neurovascular and Cognitive Dysfunction in Hypertension. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1025–1044. [CrossRef]

- Moser, M.; Roccella, E.J. The Treatment of Hypertension: A Remarkable Success Story. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2012, 15, 88–91. [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, K.; Yamori, Y. Altered Properties of Neurons and Astrocytes and the Effects of Food Components in Stroke-Prone Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2021, 77, 718–727. [CrossRef]

- Sironi, L.; Gianazza, E.; Gelosa, P.; Guerrini, U.; Nobili, E.; Gianella, A.; Cremonesi, B.; Paoletti, R.; Tremoli, E. Rosuvastatin, but not Simvastatin, Provides End-Organ Protection in Stroke-Prone Rats by Antiinflammatory Effects. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 598–603. [CrossRef]

- Gelosa, P.; Pignieri, A.; Fändriks, L.; de Gasparo, M.; Hallberg, A.; Banfi, C.; Castiglioni, L.; Turolo, L.; Guerrini, U.; Tremoli, E.; et al. Stimulation of AT2 receptor exerts beneficial effects in stroke-prone rats: focus on renal damage. J. Hypertens. 2009, 27, 2444–2451. [CrossRef]

- Gelosa, P., C. Banfi, A. Gianella, M. Brioschi, A. Pignieri, E. Nobili, L. Castiglioni, M. Cimino, E. Tremoli, and L. Sironi. "Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor {Alpha} Agonism Prevents Renal Damage and the Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Processes Affecting the Brains of Stroke-Prone Rats." J Pharmacol Exp Ther 335, no. 2 (2010): 324-31. [CrossRef]

- Zahid, H.M.; Ferdaus, M.Z.; Ohara, H.; Isomura, M.; Nabika, T. Effect of p22phox depletion on sympathetic regulation of blood pressure in SHRSP: evaluation in a new congenic strain. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36739. [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, F.; Liang, Y.-Q.; Isono, M.; Tajima, M.; Cui, Z.H.; Iizuka, Y.; Gotoda, T.; Nabika, T.; Kato, N. Integrative genomic analysis of blood pressure and related phenotypes in rats. Dis. Model. Mech. 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Mary, S.; Boder, P.; Rossitto, G.; Graham, L.; Scott, K.; Flynn, A.; Kipgen, D.; Graham, D.; Delles, C. Salt loading decreases urinary excretion and increases intracellular accumulation of uromodulin in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin. Sci. 2021, 135, 2749–2761. [CrossRef]

- Takemori, K.; Inoue, T.; Ito, H. Effects of Angiotensin II Type 1 receptor blocker and adiponectin on adipocyte dysfunction in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Lipids Heal. Dis. 2013, 12, 108–108. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, S.; Sakamoto, K.; Wakabayashi, I.; Masui, H. Effect of chromium administration on glucose tolerance in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Metabolism 1992, 41, 636–642. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Kurosawa, Y.; Minami, K.; Fushimi, K.; Narita, H. A Novel Angiotensin II-Receptor Antagonist, 606A, Induces Regression of Cardiac Hypertrophy, Augments Endothelium-Dependent Relaxation and Improves Renal Function in Stroke-Prone Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1998, 76, 185–192. [CrossRef]

- Takemori, K.; Ishida, H.; Ito, H. Continuous inhibition of the renin–angiotensin system and protection from hypertensive end-organ damage by brief treatment with angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Life Sci. 2005, 77, 2233–2245. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe-Kamiyama, M.; Kamiyama, S.; Horiuchi, K.; Ohinata, K.; Shirakawa, H.; Furukawa, Y.; Komai, M. Antihypertensive effect of biotin in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 756–763. [CrossRef]

- Castiglioni, L.; Pignieri, A.; Fiaschè, M.; Giudici, M.; Crestani, M.; Mitro, N.; Abbate, M.; Zoja, C.; Rottoli, D.; Foray, C.; et al. Fenofibrate attenuates cardiac and renal alterations in young salt-loaded spontaneously hypertensive stroke-prone rats through mitochondrial protection. J. Hypertens. 2018, 36, 1129–1146. [CrossRef]

- Berry, C.; Brosnan, M.J.; Fennell, J.; A Hamilton, C.; Dominiczak, A.F. Oxidative stress and vascular damage in hypertension. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2001, 10, 247–255. [CrossRef]

- Manning, R.D.; Meng, S.; Tian, N. Renal and vascular oxidative stress and salt-sensitivity of arterial pressure. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2003, 179, 243–250. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.B.; Touyz, R.M.; Chen, X.; Schiffrin, E.L. Chronic treatment with a superoxide dismutase mimetic prevents vascular remodeling and progression of hypertension in salt-loaded stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am. J. Hypertens. 2002, 15, 78–84. [CrossRef]

- Umemoto, S.; Tanaka, M.; Kawahara, S.; Kubo, M.; Umeji, K.; Hashimoto, R.; Matsuzaki, M. Calcium Antagonist Reduces Oxidative Stress by Upregulating Cu/Zn Superoxide Dismutase in Stroke-Prone Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Hypertens. Res. 2004, 27, 877–885. [CrossRef]

- Akasaki, T.; Ohya, Y.; Kuroda, J.; Eto, K.; Abe, I.; Sumimoto, H.; Iida, M. Increased Expression of gp91phox Homologues of NAD(P)H Oxidase in the Aortic Media during Chronic Hypertension: Involvement of the Renin-Angiotensin System. Hypertens. Res. 2006, 29, 813–820. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sheikh, A.M.; Tabassum, S.; Iwasa, K.; Shibly, A.Z.; Zhou, X.; Wang, R.; Bhuiya, J.; Abdullah, F.B.; Yano, S.; et al. Effect of high-fat diet on cerebral pathological changes of cerebral small vessel disease in SHR/SP rats. GeroScience 2024, 46, 3779–3800. [CrossRef]

- Michihara, A.; Oda, A.; Mido, M. High Expression Levels of NADPH Oxidase 3 in the Cerebrum of Ten-Week-Old Stroke-Prone Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 39, 252–258. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-H.; Chen, H.-L.; Fan, H.-C.; Tung, Y.-T.; Kuo, C.-W.; Tu, M.-Y.; Chen, C.-M. Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, and Antifibrotic Effects of Kefir Peptides on Salt-Induced Renal Vascular Damage and Dysfunction in Aged Stroke-Prone Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 790. [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Nelson, J.W.; Phillips, S.; Petrosino, J.F.; Bryan, R.M.; Durgan, D.J. Alterations of the gut microbial community structure and function with aging in the spontaneously hypertensive stroke prone rat. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Santisteban, M.M.; Rodriguez, V.; Li, E.; Ahmari, N.; Carvajal, J.M.; Zadeh, M.; Gong, M.; Qi, Y.; Zubcevic, J.; et al. Gut Dysbiosis Is Linked to Hypertension. Hypertension 2015, 65, 1331–1340. [CrossRef]

- Akira, K.; Masu, S.; Imachi, M.; Mitome, H.; Hashimoto, T. A metabonomic study of biochemical changes characteristic of genetically hypertensive rats based on 1H NMR spectroscopic urinalysis. Hypertens. Res. 2011, 35, 404–412. [CrossRef]

- Čermáková, M.; Pelantová, H.; Neprašová, B.; Šedivá, B.; Maletínská, L.; Kuneš, J.; Tomášová, P.; Železná, B.; Kuzma, M. Metabolomic Study of Obesity and Its Treatment with Palmitoylated Prolactin-Releasing Peptide Analog in Spontaneously Hypertensive and Normotensive Rats. J. Proteome Res. 2019, 18, 1735–1750. [CrossRef]

- Brial, F.; Chilloux, J.; Nielsen, T.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Falony, G.; Andrikopoulos, P.; Olanipekun, M.; Hoyles, L.; Djouadi, F.; Neves, A.L.; et al. Human and preclinical studies of the host–gut microbiome co-metabolite hippurate as a marker and mediator of metabolic health. Gut 2021, 70, 2105–2114. [CrossRef]

- Calvani, R.; Miccheli, A.; Capuani, G.; Miccheli, A.T.; Puccetti, C.; Delfini, M.; Iaconelli, A.; Nanni, G.; Mingrone, G. Gut microbiome-derived metabolites characterize a peculiar obese urinary metabotype. Int. J. Obes. 2010, 34, 1095–1098. [CrossRef]

- Mogilnicka, I., K. Jaworska, M. Koper, K. Maksymiuk, M. Szudzik, M. Radkiewicz, D. Chabowski, and M. Ufnal. "Hypertensive Rats Show Increased Renal Excretion and Decreased Tissue Concentrations of Glycine Betaine, a Protective Osmolyte with Diuretic Properties." PLoS One 19, no. 1 (2024): e0294926. [CrossRef]

- Chachaj, A.; Matkowski, R.; Gröbner, G.; Szuba, A.; Dudka, I. Metabolomics of Interstitial Fluid, Plasma and Urine in Patients with Arterial Hypertension: New Insights into the Underlying Mechanisms. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 936. [CrossRef]

- Bartuś, M.; Łomnicka, M.; Kostogrys, R.B.; Kaźmierczak, P.; Watała, C.; Słominska, E.M.; Smoleński, R.T.; Pisulewski, P.M.; Adamus, J.; Gebicki, J.; et al. 1-Methylnicotinamide (MNA) prevents endothelial dysfunction in hypertriglyceridemic and diabetic rats. Pharmacol Rep 2008, 60, 127–38.

- Choi, Y.-J.; Yoon, Y.; Lee, K.-Y.; Kang, Y.-P.; Lim, D.K.; Kwon, S.W.; Kang, K.-W.; Lee, S.-M.; Lee, B.-H. Orotic Acid Induces Hypertension Associated with Impaired Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthesis. Toxicol. Sci. 2015, 144, 307–317. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E. N., D. B. Mount, J. P. Forman, and G. C. Curhan. "Association of Prevalent Hypertension with 24-Hour Urinary Excretion of Calcium, Citrate, and Other Factors." Am J Kidney Dis 47, no. 5 (2006): 780-9. [CrossRef]

- Il'Yasova, D.; Scarbrough, P.; Spasojevic, I. Urinary biomarkers of oxidative status. Clin. Chim. Acta 2012, 413, 1446–1453. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F.; Tsai, J.-T.; Chen, L.-J.; Wu, T.-P.; Yang, J.-J.; Yin, L.-T.; Yang, Y.-L.; Chiang, T.-A.; Lu, H.-L.; Wu, M.-C. Antihypertensive Action of Allantoin in Animals. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Mutter, S.; Valo, E.; Aittomäki, V.; Nybo, K.; Raivonen, L.; Thorn, L.M.; Forsblom, C.; Sandholm, N.; Würtz, P.; Groop, P.-H. Urinary metabolite profiling and risk of progression of diabetic nephropathy in 2670 individuals with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2021, 65, 140–149. [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J. K., J. A. Timbrell, and P. J. Sadler. "Proton Nmr Spectra of Urine as Indicators of Renal Damage. Mercury-Induced Nephrotoxicity in Rats." Mol Pharmacol 27, no. 6 (1985): 644-51.

- Kim-Mitsuyama, S.; Yamamoto, E.; Tanaka, T.; Zhan, Y.; Izumi, Y.; Izumiya, Y.; Ioroi, T.; Wanibuchi, H.; Iwao, H. Critical Role of Angiotensin II in Excess Salt-Induced Brain Oxidative Stress of Stroke-Prone Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Stroke 2005, 36, 1077–1082. [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, S., C. Z. Bueche, C. Garz, S. Kropf, F. Angenstein, J. Goldschmidt, J. Neumann, H. J. Heinze, M. Goertler, K. G. Reymann, and H. Braun. "The Pathologic Cascade of Cerebrovascular Lesions in Shrsp: Is Erythrocyte Accumulation an Early Phase?" J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32, no. 2 (2012): 278-90. [CrossRef]

- Stanisavljevic, A.; Schrader, J.M.; Zhu, X.; Mattar, J.M.; Hanks, A.; Xu, F.; Majchrzak, M.; Robinson, J.K.; Van Nostrand, W.E. Impact of Non-pharmacological Chronic Hypertension on a Transgenic Rat Model of Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 811371. [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, S.; Bueche, C.Z.; Garz, C.; Braun, H. Blood brain barrier breakdown as the starting point of cerebral small vessel disease? - New insights from a rat model. Exp. Transl. Stroke Med. 2013, 5, 4–4. [CrossRef]

- Baumbach, G.L.; Dobrin, P.B.; Hart, M.N.; Heistad, D.D. Mechanics of cerebral arterioles in hypertensive rats.. Circ. Res. 1988, 62, 56–64. [CrossRef]

- Baumbach, G.L.; Heistad, D.D. Remodeling of cerebral arterioles in chronic hypertension.. Hypertension 1989, 13, 968–972. [CrossRef]

- Allan, S. The Neurovascular Unit and the Key Role of Astrocytes in the Regulation of Cerebral Blood Flow. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2006, 21, 137–138. [CrossRef]

- Koehler, R.C.; Gebremedhin, D.; Harder, D.R.; Shih, E.K.; Robinson, M.B.; Merchant, S.; Medow, M.S.; Visintainer, P.; Terilli, C.; Stewart, J.M.; et al. Role of astrocytes in cerebrovascular regulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 100, 307–317. [CrossRef]

- Holash, J. A., D. M. Noden, and P. A. Stewart. "Re-Evaluating the Role of Astrocytes in Blood-Brain Barrier Induction." Dev Dyn 197, no. 1 (1993): 14-25. [CrossRef]

- Ridet, J.L.; Malhotra, S.K.; Privat, A.; Gage, F.H. Reactive astrocytes: cellular and molecular cues to biological function. Trends Neurosci. 1997, 20, 570–577. [CrossRef]

- Steiner, J.; Bernstein, H.-G.; Bielau, H.; Berndt, A.; Brisch, R.; Mawrin, C.; Keilhoff, G.; Bogerts, B. Evidence for a wide extra-astrocytic distribution of S100B in human brain. BMC Neurosci. 2007, 8, 2–2. [CrossRef]

- Chistyakov, D.V.; Aleshin, S.; Sergeeva, M.G.; Reiser, G. Regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ expression and activity levels by toll-like receptor agonists and MAP kinase inhibitors in rat astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 2014, 130, 563–574. [CrossRef]

- Rahimifard, M.; Maqbool, F.; Moeini-Nodeh, S.; Niaz, K.; Abdollahi, M.; Braidy, N.; Nabavi, S.M.; Nabavi, S.F. Targeting the TLR4 signaling pathway by polyphenols: A novel therapeutic strategy for neuroinflammation. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 36, 11–19. [CrossRef]

- Ritz, M.-F.; Fluri, F.; Engelter, S.T.; Schaeren-Wiemers, N.; Lyrer, P.A. Cortical and Putamen Age-Related Changes in the Microvessel Density and Astrocyte Deficiency in Spontaneously Hypertensive and Stroke-Prone Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Curr. Neurovascular Res. 2009, 6, 279–287. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Jing, Y.; Zang, P.; Hu, X.; Gu, C.; Wu, R.; Chai, B.; Zhang, Y. Vascular Cognitive Impairment Caused by Cerebral Small Vessel Disease Is Associated with the TLR4 in the Hippocampus. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2019, 70, 563–572. [CrossRef]

- Higashino, H.; Niwa, A.; Satou, T.; Ohta, Y.; Hashimoto, S.; Tabuchi, M.; Ooshima, K. Immunohistochemical analysis of brain lesions using S100B and glial fibrillary acidic protein antibodies in arundic acid- (ONO-2506) treated stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Neural Transm. 2009, 116, 1209–1219. [CrossRef]

- Badaut, J., F. Lasbennes, P. J. Magistretti, and L. Regli. "Aquaporins in Brain: Distribution, Physiology, and Pathophysiology." J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 22, no. 4 (2002): 367-78. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.; Nagelhus, E.A.; Amiry-Moghaddam, M.; Bourque, C.; Agre, P.; Ottersen, O.P. Specialized Membrane Domains for Water Transport in Glial Cells: High-Resolution Immunogold Cytochemistry of Aquaporin-4 in Rat Brain. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 171–180. [CrossRef]

- Manley, G.T.; Fujimura, M.; Ma, T.; Noshita, N.; Filiz, F.; Bollen, A.W.; Chan, P.; Verkman, A.S. Aquaporin-4 deletion in mice reduces brain edema after acute water intoxication and ischemic stroke. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 159–163. [CrossRef]

- Takemori, K.; Murakami, T.; Kometani, T.; Ito, H. Possible involvement of oxidative stress as a causative factor in blood–brain barrier dysfunction in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Microvasc. Res. 2013, 90, 169–172. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, R.; Wang, Z. Contribution of Oxidative Stress to HIF-1-Mediated Profibrotic Changes during the Kidney Damage. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Barallobre-Barreiro, J., B. Loeys, M. Mayr, M. Rienks, A. Verstraeten, and J. C. Kovacic. "Extracellular Matrix in Vascular Disease, Part 2/4: Jacc Focus Seminar." J Am Coll Cardiol 75, no. 17 (2020): 2189-203. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Quinones, P.; McCarthy, C.G.; Watts, S.W.; Klee, N.S.; Komic, A.; Calmasini, F.B.; Priviero, F.; Warner, A.; Chenghao, Y.; Wenceslau, C.F. Hypertension Induced Morphological and Physiological Changes in Cells of the Arterial Wall. Am. J. Hypertens. 2018, 31, 1067–1078. [CrossRef]

- Sansawa, H.; Takahashi, M.; Tsuchikura, S.; Endo, H. Effect of Chlorella and Its Fractions on Blood Pressure, Cerebral Stroke Lesions, and Life-Span in Stroke-Prone Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2006, 52, 457–466. [CrossRef]

- Yamori, Y. Overview: Studies on Spontaneous Hypertension - Development from Animal Models Toward Man. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. Part A: Theory Pr. 1991, 13, 631–644. [CrossRef]

- Pelantová, H.; Tomášová, P.; Šedivá, B.; Neprašová, B.; Mráziková, L.; Kuneš, J.; Železná, B.; Maletínská, L.; Kuzma, M. Metabolomic Study of Aging in fa/fa Rats: Multiplatform Urine and Serum Analysis. Metabolites 2023, 13, 552. [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.A.B.; Bruder-Nascimento, T.; Cau, S.B.A.; Lopes, R.A.M.; Mestriner, F.L.A.C.; Fais, R.S.; Touyz, R.M.; Tostes, R.C. Spironolactone treatment attenuates vascular dysfunction in type 2 diabetic mice by decreasing oxidative stress and restoring NO/GC signaling. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 269. [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal. Biochem. 1979, 95, 351–358. [CrossRef]

- Vaněčková, I., P. Kujal, Z. Husková, Z. Vaňourková, Z. Vernerová, V. Certíková Chábová, P. Skaroupková, H. J. Kramer, V. Tesař, and L. Červenka. "Effects of Combined Endothelin a Receptor and Renin-Angiotensin System Blockade on the Course of End-Organ Damage in 5/6 Nephrectomized Ren-2 Hypertensive Rats." Kidney Blood Press Res 35, no. 5 (2012): 382-92. [CrossRef]

- Kujal, P., VČ Chábová, Z. Vernerová, A. Walkowska, E. Kompanowska-Jezierska, J. Sadowski, Z. Vaňourková, Z. Husková, M. Opočenský, P. Skaroupková, S. Schejbalová, H. J. Kramer, D. Rakušan, J. Malý, I. Netuka, I. Vaněčková, L. Kopkan, and L. Cervenka. "Similar Renoprotection after Renin-Angiotensin-Dependent and -Independent Antihypertensive Therapy in 5/6-Nephrectomized Ren-2 Transgenic Rats: Are There Blood Pressure-Independent Effects?" Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 37, no. 12 (2010): 1159-69. [CrossRef]

- Holubová, M.; Hrubá, L.; Neprašová, B.; Majerčíková, Z.; Lacinová, Z.; Kuneš, J.; Maletínská, L.; Železná, B. Prolactin-releasing peptide improved leptin hypothalamic signaling in obese mice. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2018, 60, 85–94. [CrossRef]

- Kořínková, L.; Holubová, M.; Neprašová, B.; Hrubá, L.; Pražienková, V.; Bencze, M.; Haluzík, M.; Kuneš, J.; Maletínská, L.; Železná, B. Synergistic effect of leptin and lipidized PrRP on metabolic pathways in ob/ob mice. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2020, 64, 77–90. [CrossRef]

- Pražienková, V., J. Funda, Z. Pirník, A. Karnošová, L. Hrubá, L. Kořínková, B. Neprašová, P. Janovská, M. Benzce, M. Kadlecová, J. Blahoš, J. Kopecký, B. Železná, J. Kuneš, K. Bardová, and L. Maletínská. "Gpr10 Gene Deletion in Mice Increases Basal Neuronal Activity, Disturbs Insulin Sensitivity and Alters Lipid Homeostasis." Gene 774 (2021): 145427. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).