1. Introduction

Augmented Reality (AR) has rapidly emerged as a technology with wide reaching potential , enhancing the physical world by overlaying digital content in real time [

1,

2]. As AR applications proliferate across domains such as education, healthcare, manufacturing, and entertainment, the quality of user interactions—particularly in near-field environments—has become critical to the effectiveness of these systems [

3,

4]. Designing effective AR interactions presents unique challenges due to the integration of digital and physical spaces, which directly impacts user engagement, task performance, and overall experience [

5].

Although modern commercially available head-mounted displays (HMDs) offer robust capabilities, their perceptual limitations are well documented (as discussed in the following section)[

6,

7,

8]. While ongoing research aims to address these limitations, developers must, in the meantime, find practical strategies to work within the constraints of current hardware [

9,

10,

11]. However, there is a noticeable gap in the literature regarding techniques accessible to developers that mitigate these perceptual issues in near-field AR interactions using commercial HMDs.

In this paper, we investigate existing strategies to overcome, adapt to, or alleviate perceptual challenges in near-field AR environments. To map the current state of knowledge in this niche area, we conducted a scoping literature review of full conference papers and journal articles published since 2016. Following the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews) [

12,

13] guidelines (the process suggested by Cooper et al. [

14] and [

15]), we searched four academic databases—ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, PubMed, and ScienceDirect — yielding an initial set of 780 unique items. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, seven papers were retained for final analysis. We employed both deductive coding and inductive latent pattern content analysis to extract meaningful insights.

Our findings provide a categorization and visualization of the current literature landscape, identifying key themes and recurring challenges. We emphasize the roles of embodiment and immersion in near-field AR interactions and highlight the absence of a consistent definition for the near-field range. We propose a defined range for future studies investigating near-field interactions based on our analysis and offer recommendations for future research directions.

2. Background

In this section we begin by discussing the relevant concepts and definitions before going on to address the need and rationale for this work.

2.1. Augmented Reality

Augmented reality was conceptualised as early as 1965 but has seen a boom in interest in recent years [

16,

17]. While the definition of AR is somewhat fluid, and there is some argument among researchers around the differences between AR and mixed reality (MR), it can generally be agreed that AR superimposes digital objects into the users’ view in real-time using a headset or other device [

18,

19,

20]. The aim is to add virtual components to the user’s field of view in order to provide them with additional information while carrying out a task. Thomas Caudell, at Boeing, coined the term augmented reality in 1992 but it is since around 2016 that a new and continuing wave of development has changed the face of AR [

21,

22,

23].

2016 saw several significant events in the field, such as the release of the first generation Microsoft HoloLens [

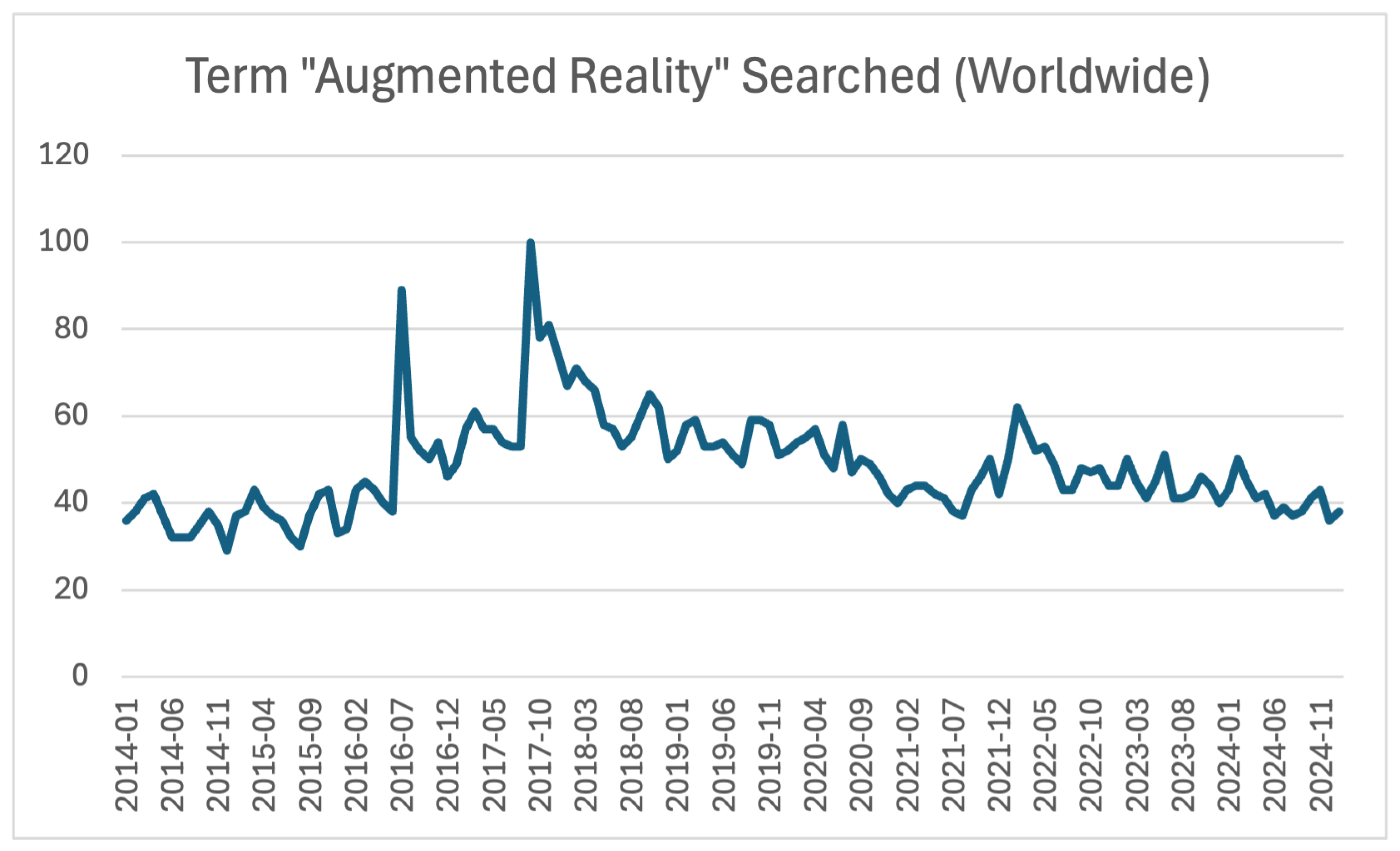

24], which was the fully untethered first stand-alone HMD. This was one of the first of the modern breed of HMDs and allowed the HoloLens much more freedom than previous devices, and to be much more flexible in a larger range of environments. The Google Scholar searches that included the term "Augmented Reality" had a peaks in 2016 and 2017 as shown in

Figure 1. This chart shows search interest in the given term relative to the highest point on the graph [

25]. The first HTC Vive [

26] virtual reality (VR) HMD and Pokemon Go! [

27] were also released in 2016 with other developments such as IKEA place [

28] and the Enterprise Edition of Google Glass [

29]released in 2017 which shows a wider and consistent heightened interest in AR and XR (extended reality) more generally.

2.2. The Near-Field and Perception

The interactions that AR affords can be considered one of the core advantages of the technology and there has been considerable research in this area [

30]. A subset of this area is specifically interactions in near-field ranges, that is to say the immediate area around the user. However, definitions of near-field are varied and no more specific than “within arm’s reach" [

31,

32]. Speaking more generally than XR, Cutting and Vishton [

33] defined personal space in this way in 1995, going on to “arbitrarily delimit this space to be within 2 metres".

2.2.1. Perceptual Issues in the Near-Field

Modern commercially available HMDs are very capable devices, but there are still limitations to their use [

34,

35,

36]. One of these limitations that has various knock-on effects is the fixed focal depth which, for most HMDs, is around two to three metres, meaning that regardless of the depth that the virtual content is intended to be it is always projected at this distance of around two metres [

9,

37,

38]. This can induce a number of perceptual issues, principally the vergence accommodation conflict (VAC) which is a result of the users’ eyes receiving mismatched cues [

10]. The eyes’ two mechanisms of focusing (converging onto the target and the lenses accommodating to the same target) compete against one another and can result in discomfort, simulation sickness, and inaccurate perception of the virtual content. This affect is more common, or more pronounced when the distance between the viewing target and the two metre focal depth are greater, for instance in near-field interactions [

39]. Focal rivalry can also cause similar discomfort in situations like this, where a user is attempting to keep in focus two objects, virtual and physical, at different depths, at the same time [

40]. In 2013 Argelaguet and Andujar [

41] stated that a major block for effective user interaction in virtual environments (VEs) is that the technology fails to reproduce faithfully the physical constraints of the real world. While improvements have been made since 2013, modern HMDs still cannot provide users with all the cues they need to interpret the environment accurately [

37].

Edwards et al. [

42] provide an overview of the challenges of AR for surgery and suggest that “visualization and issues surrounding perception and interaction are in fact the biggest issues facing AR surgical guidance". It is likely then, that this can be generalised to other manual tasks with similar requirements.

2.2.2. The Challenge of Researching Perception

Perceptual issues and how design or interactions affect them are difficult to investigate for two key reasons. Firstly, there are a large number of contributors to perception that all have complex effects and interactions with each other, which makes it difficult to isolate one contributor to perception, evaluate it, and measure what affects it [

7,

43]. Secondly, everyone perceives things slightly differently and the results must be empirical, only the participant of a study can see what they are seeing, the researcher can only measure the effect of an action the participant makes as a result of perceiving something [

44,

45]. This makes perception a challenging area to research.

2.2.3. Design

As stated by Cutting and Vishton [

33], the strongest perceptual cue at arms length is occlusion, followed by binocular disparity (stereopsis), motion parallax, relative size, illumination and shadows, convergence, and accommodation. However, it is generally accepted that modern HMDs cannot faithfully represent all these cues that enable a user to interpret their environment [

36,

39]. Various design techniques to work around these issues have been investigated, such as using virtual apertures in an occluding surface when focusing on an object beneath - X-ray vision is the example here [

46]. True occlusion is not possible with optical see-through (OST) devices, but can be achieved with video see-through (VST) HMDs, and reduced depth errors have been shown in VR when true occlusion is achieved [

47].

Perceptual issues have some commonality between different HMDs but some variation can be observed when moving between different display technologies, that is, OST and VST [

48,

49]. These two technologies have fundamentally different ways of presenting content to the user, and as such the perception of that content varies between the two. These perceptual differences have been investigated somewhat, but there has been much less evaluation of their effects when interactions move into the near-field [

48].

2.2.4. Interaction

AR interactions can be supported by modalities such as speech, gaze, hand gestures, and additional hardware such as controllers or gloves [

50,

51]. The body of work investigating interactions for manipulating objects in virtual environments (VEs) in the near-field generally concludes that `natural’, direct manipulation is preferred [

52]. However, there is research supporting the contrary, and many of the studies conducted are very specific to one task [

53]. There has been comparatively less generalisable evaluation, and research continues to extensively explore intuitive and immersive interactions with virtual objects [

41].

In VR, studies show that increasing embodiment with high fidelity avatars can reduce mental load and increase the performance of a task and improve depth estimation accuracy, a subject that is gaining traction in AR [

54]. The extent to which avatarisation effects embodiment in AR and its effect on interaction is not fully understood but recent research shows its potential [

55].

2.3. Rationale, the Research Gap, and Need for this Review

As discussed above interaction is a key area of XR research with many issues clearly identified and work done to combat them [

5,

30]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is relatively little work, and no synthesis of the work around what AR application developers can do to address these issues while working within the constraints of commercial HMDs. This idea of using design and interaction techniques to optimise the use of commercial HMDs is necessary in lieu of adjacent (but likely slower) work going into developing the HMDs to overcome these issues fundamentally [

11,

56]. The aim of this review is to map current research in this area to aid developers and researchers in this matter, and then to suggest directions for future work to take this further.

3. Methodology

We aim to identify and map the literature that discusses design or interaction techniques to address perceptual challenges in near-field AR using commercially available HMDs. As such, we chose to conduct a scoping literature review. Sutton et al. [

57] define a scoping review as “a review that seeks to explore and define conceptual and logistic boundaries around a particular topic with a view to informing a future predetermined systematic review or primary research". Systematic reviews are defined by their “comprehensive search approach", asking one specific question and carrying out a formal synthesis, while scoping reviews instead explore a range of evidence and present the included literature to provide a structured overview of the landscape [

57]. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines and the PRISMA-ScR checklist [

12].

3.1. Research Questions and Aim

This scoping review is focussed on answering the following research question:

RQ1: How can virtual design or interaction techniques be used to alleviate perceptual issues in near-field AR.

With two sub-questions:

RQ1.1: Is near-field perception better in VST than OST?

RQ1.2: What techniques are being used to work within commercial HMDs?

This work is motivated in part by experientially seeing the lack of research looking at how perceptual issues can be addressed while still using commercially available "off-the-shelf" HMDs. As discussed in the previous section most commercial HMDs have similar hardware restrictions magnified in the near-field, but there is little guidance on how to work around these. There is comparatively more work looking at how the hardware within HMDs can be improved but we are interested in the things that designers and software developers can do when building AR applications to help alleviate some of the effects that the known perceptual issues can cause [

58].

Therefore the aim of this review is to understand and map the existing literature that uses design and interaction to address near-field perceptual issues while using commercially available HMDs. We focus our search on how researchers are working within the bounds of the commercial hardware to alleviate and overcome these perceptual issues, using design and interaction techniques.

3.2. Search Strategy

3.2.1. Definition of Key Words

To define the keywords that would be used to construct the search term, we used the PCC (Participants, Concept, Context) framework recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute. This process structures the definition of key words into three groups, enabling the definition of keywords and then listing of alternatives. Using this relieves some subjectivity from the keyword generation process. Four key areas of interest were identified to group the terms at this stage, derived from the research question: perception, design/interaction, AR, and near-field. The lead author was primarily responsible for this, with the other authors consulted to ensure everyone was in agreement with the terms defined. See

Table 1 for the PCC table of terms. An initial search term was then constructed using the keywords from the PCC table, combining the four key areas (perception, design/interaction, AR, near-field) with ’AND’ statements, and the keywords within these areas with ’OR’ statements. The initial search term is listed here:

2016 to present

(Percept* OR visual OR vision) AND

(design OR interaction) AND

("mixed reality" OR MR OR "augmented reality" OR AR) AND

("near field" OR "near-field" OR "close up" OR "close range" OR

"peripersonal" OR "near range" OR "near by" OR "near-by")

To ensure no important key words had been missed, an initial search of the ACM Digital Library and IEEE Xplore was conducted with the keywords from the PCC table. The titles, abstracts, and author keywords from the papers returned were screened for any keywords that had been missed from the search term. From this process only “close-range" was added to our list. There were many other candidate keywords but all other were either deemed too broad, not specific enough to our question, or too specific to be included in our list. For example “depth cues" would narrow the search too much, but “3D vision" would broaden into computer vision literature. The final search term is listed here:

2016 to present

("Percept*" OR "visual" OR "vision") AND

("design" OR "interaction") AND

("mixed reality" OR "MR" OR "augmented reality" OR "AR") AND

("near field" OR "near-field" OR "close up" OR "close range" OR

"close-range" OR "peripersonal" OR "near range" OR "near by" OR

"near-by")

3.2.2. Search Databases and Date Range

Based on preliminary searches with a subset of the keywords defined above, four databases were identified for this review: ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, PubMed, and Science Direct. These preliminary searches were also used to establish a date range for the final search. 2016 was decided to be an appropriate start date. As discussed in the background, this is because it is an important year around the development of XR technology with the Microsoft HoloLens 1 released which was the first fully untethered, stand-alone HMD. It was also a key turning point for the hype around AR which led to increased research focus and development, as discussed in the background [

22,

23,

24].

3.3. Evidence Screening and Filtering

We used a two stage process to filter and identify appropriate papers to be included. The first involved filtering based on the papers’ title and abstract, then second against the whole paper. This is represented in the PRISMA-ScR diagram

Figure 2.

3.3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria used to screen papers is summarised in

Table 2. These criteria were reached by taking the research question(s) and breaking it down into its components. The exclusion criteria represent a lack of each of these components; to be excluded, a paper would meet one or more of these exclusion criteria. An included paper must fit at least one of the inclusion criteria.

3.3.2. Running the Query

The final search was run on the 28th of February 2025 (28/02/2025) with 805 total records returned (ACM: 582, IEEE: 178, PubMed: 11, Science Direct: 34). Once collated, there were 25 duplicates leaving 780 records for the title and abstract filtering. 747 records excluded in the title and abstract filtering stage leaving 33 records to be retrieved and read in full. 26 records excluded based on reading them in full leaving 7 records for the final data extraction. The PRISMA-ScR diagram 2 details how many records were included and excluded at each stage in line with the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

3.4. Data Extraction

Data extraction was again, a two stage process with the first being a deductive coding and categorisation round and the second being inductive content analysis. This approach was chosen in line with other scoping reviews and recommendations from PRISMA-ScR and the JBI [

59,

60]. It allowed us to develop a rich understanding of the work included in our corpus and generate a thorough construction of conceptual and logical boundaries within the content.

3.4.1. Stage One - Deductive

This first stage involved developing a set of deductive codes and coding the seven included papers against this set. Each paper was read twice during this stage to ensure that all elements were coded appropriately. The codes were developed first by the lead author by breaking down the research questions and objectives of the review. The four sections of the search query (perception, design/interaction, AR, near-field) also came into the code development to ensure all bases had been covered and to maximise the appropriate data that could be collected. After the first round at this stage the codes were reviewed and discussed with all the authors to fill any gaps and address the appropriateness of the codes taken forwards.

Each code either had a list of values to choose from to categorise (e.g. C1, C4, C6), or text was copied and summarise directly from the paper (e.g. C2, C3, C5, C7). See

Table 3 for a full list of 18 codes and predefined values. By the nature of the research question and therefore the inclusion criteria one of C14 and C15 must be complete, i.e. a paper investigates either design or interaction. This deductive coding stage also acted as a familiarisation phase for the next stage of the analysis.

3.4.2. Stage Two - Inductive Content Analysis

Stage two of the data extraction was inductive coding. Latent pattern content analysis [

61] was chosen as an appropriate method for this as the core advantage of content analysis is to condense information within and across the data corpus. The latent pattern part of this method means that the researcher plays an active role in interpreting and finding meaning within the data while seeking to establish a pattern of characteristics within the data. It is more than just collecting overt, surface level meaning and it is inherently linked to the researcher and their interpretation. Latent pattern analysis goes beyond the surface level to identify patterns within the data but while the researcher is integral, it is not reliant on the position or lived experiences of the analyst to establish the patterns [

61]. The patterns are recognisable within the context.

Again, each paper was read twice for this stage of the analysis to ensure scrutiny and to close any gaps. The previous deductive analysis acted as a familiarisation stage which aided the beginning of this process. The lead author conducted the content analysis but the other authors were met with after each round of reading to discuss how the papers were being coded, any issues, and the codes themselves.

3.4.3. Critical Appraisal, Limitations, and Potential Bias

While scoping reviews typically include all types of evidence we chose to restrict our search to full paper proceedings and journal articles in order to set a high level of research rigour. The result of this is a small data corpus of just seven papers. But this in itself was motivation for this review, the lack of research in this area. By conducting this review we hope to help direct future work in this space.

A potential limitation of this review is the chance of missed keywords and therefore missed papers. We endeavoured to avoid this by using the PCC method for collating keywords for the search term however this is not unassailable. We do however, believe that we have been thorough enough to cover enough of the data in this space to be representative. This enables us to maintain confidence in the results of our review.

One challenge during the evidence screening was the large volume of papers returned from the query that were deemed irrelevant, specifically that fell into exclusion criterion 10 (EC10), false positive. We believe that this is due to the imprecise nature of the keywords that define this space. Nearly all of the keywords that should narrow down the search (presented in the PCC

Table 1) are used in different contexts. The result of these keywords having multiple meanings or wide meaning is a large number of papers that the query returns correctly (because the keywords are present) but are not relevant to our research question. As discussed previously this was part of the motivation for not including any more keywords returned after the initial search to validate search terms. Maintaining these wide-reaching keywords though, increased the likelihood that we found all relevant papers.

We recognise that there is the potential for bias throughout the process of choosing keywords, screening evidence, etc but through the process described here we have endeavoured to limit the effects of this bias. By using methods such as PCC we removed a level of subjectivity when establishing keywords. Similarly by defining a thorough inclusion and exclusion criteria ahead of the screening and discussing papers where there is any doubt with all authors, we ensured rigour in our work.

3.4.4. Synthesis

While a formal synthesis is not usually included in a scoping review the results section below presents the findings from the data extraction from both the deductive and inductive coding in order to harmonise the meaning. The results from the deductive round are presented first, largely with tables and graphs illustrating the categorisation of the included papers over different groups. The results from the inductive round are presented as themes that represent a collection of related codes recognising a pattern in the data.

4. Results

This section is split in line with the two rounds of analysis, the deductive coding, and the inductive content analysis. The deductive results give an outline of the focusses of the included papers and the metrics that describes the data corpus. The results from the content analysis are presented as the themes that were generated through this process.

Two key findings that will be discussed further in line with the themes are highlighted here. The first observation, is that of the two competing goals when developing near-field AR experiences - One goal is to replicate the real world faithfully, to provide the user with all of the cues that they would receive and use to make decisions for real world interactions. Conversely, the goal to build on the real world using AR to achieve what cannot be achieved in the physical world, interactions and experiences that are only possible due to the technology. The second observation concerns the way that design and interaction techniques are applied. Design techniques are employed to help replicate the real world or work around scenarios where true replications cannot be achieved, interaction techniques are applied to work around obstacles to realism or go beyond realistic capability and provide experiences impossible without the technology [

62,

63].

We present an answer to our main research question but found insufficient evidence to provide answers for the two sub-questions. The discussion section will describe links between points in the results, their impact, and what this means going forwards.

4.1. Deductive

The deductive codes allowed us to break down the data corpus into groups which enables us to illustrate how different categories and factors are represented within the included papers.

Firstly, the codes C1, C15, and C16 show us that there was a near 50:50 split between papers of the two categories, and interaction techniques vs design techniques. Four papers fell into the “Design technique applied to perceptual issue" and three into “Interaction technique applied to perceptual issue", this was similarly reflected between C15 and C16.

In opposition to this 50:50 split, of the included papers only one used a VST HMD, the rest used optical see-through HMDs. Of these six, five used a Microsoft HoloLens (four studies using the second generation), and the other two used other HMDs (Meta DK1, Epson Moverio BT200).

All seven studies in the data corpus conducted an empirical field study with participants. This is likely due to the nature of researching in the area of perception. As everyone perceives things slightly differently and it is impossible to know exactly what someone else in seeing, you can only measure the result of an action upon what they are seeing - an empirical study is necessitated [

45]. This builds on the challenges of researching this area as discussed in the background.

There was a lot of variability in how near-field was presented and the boundaries placed upon it with many studies loosely defining it as “within arm’s reach". All studies either defined near-field or conducted their study between 25 cm and 100 cm in front of the participant.

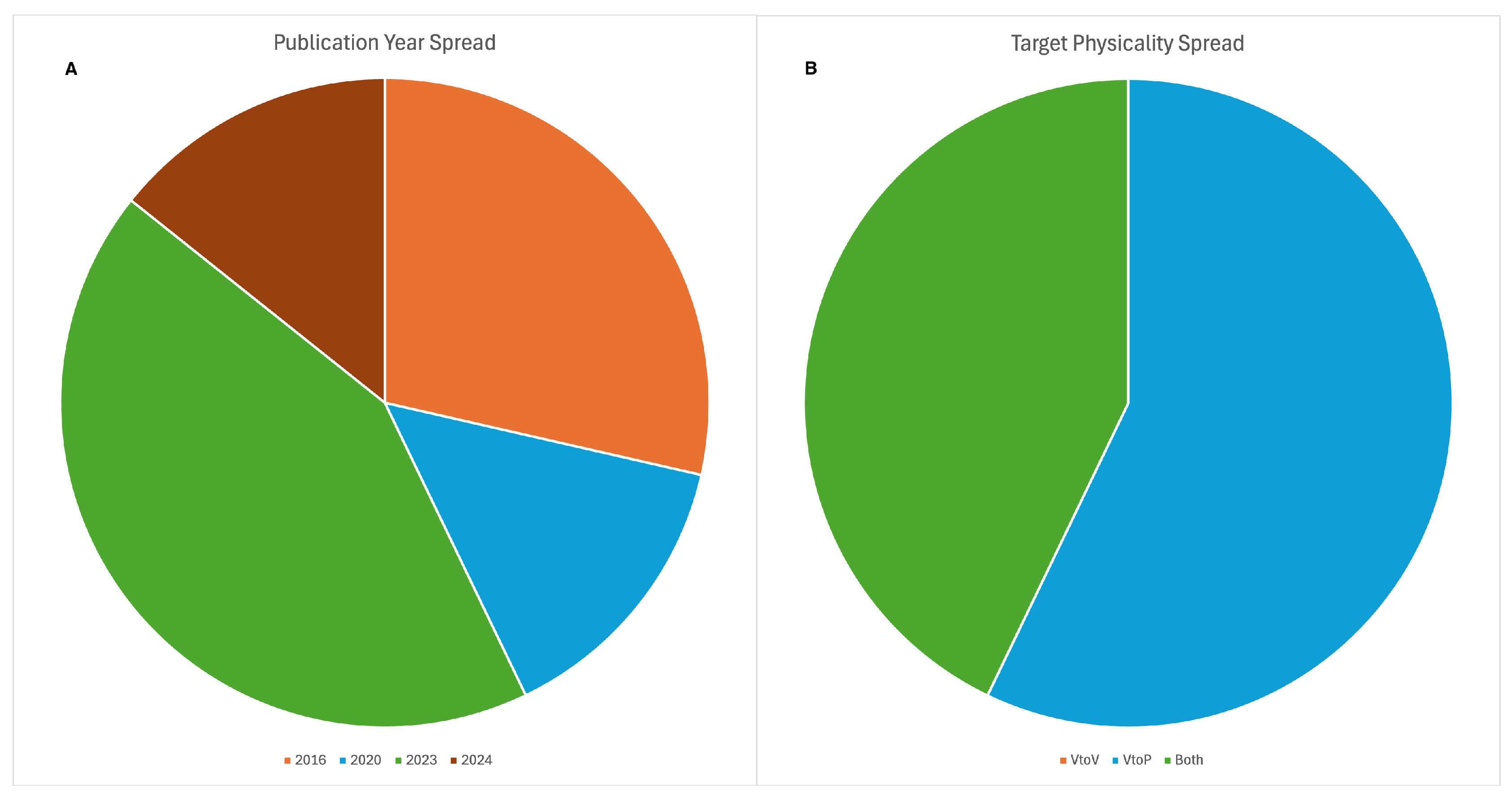

Figure 3 ’A’ shows the distribution of publication years across the data corpus with most (three) papers published in 2023, and two papers published in 2024.

Figure 3 ’B’ illustrates C8 describing the physicality of the objects used in the study task. The tasks in four of the studies fell into “virtual to physical", i.e. the participant was asked to move a virtual object relative to a physical target, and the tasks in three studies included both virtual to physical and virtual to virtual elements. No studies investigated purely virtual to virtual stimuli.

Figure 4 shows the number of participants engaged by each study and the mean average at 28. This includes one study engaging just four participants while all others had 13 or more participants. This difference in the number of participants was due to the specialised and intensive nature of the user task, involving participants specific to the application and a much longer engagement.

There was little cohesion between the types of task each study used in their investigations. Some asked users to move a virtual object relative to another, following or taking inspiration from blind reaching (a common technique used to study hand-eye coordination [

64]), others made interactions more directly with a single virtual object. Nor was there much consistency in the metrics for evaluation. Task completion time was the most common metric and often there was a combination of quantitative and qualitative assessment. Quantitative metrics were very specific to the task and the research questions, qualitative metrics tended to be usability questionnaires or the NASA-TLX [

65] or similar.

A wide range of perceptual issues were investigated in the studies included, depth perception being the most common. Others included focal rivalry and VAC, perception-action coordination, and parallax.

4.2. Inductive

4.2.1. Hardware Effects or Limitations for Near-Field

It is well known that there are limitations to experiences laid on by the hardware of commercially available HMDs, what we have found here supports this and gives further support and context to this point for near-field applications. As discussed in the background the source of a significant issue is the fixed focal depth that all virtual content is displayed at, and when virtual content moves away from this point perceptual challenges arise. This fixed depth is often around two metres which therefore exaggerates issues for near-field tasks as the interaction point is at least a metre away from this fixed focal depth (as indicated by definition of near field above).

Also highlighted by this theme is the difference in hardware limitations between OST and VST technologies. Firstly, we have further support of the statement that OST and VST pose different design challenges. This is a known entity and is intuitive but our review reaffirms this in the context of near-field interactions. Additionally, we highlight two key issues with OST technologies that hinder immersion and exacerbates perceptual issues. One, the inability of OST HMDs to provide true occlusion. While it is stated within the contribution of one of our included papers that occlusion is not necessary for accurate depth perception and near-field interactions if all other depth cues are preserved, occlusion is a strong depth cue that users are often reliant on especially as current HMDs don’t preserve other depth cues 100% accurately. Cutting and Vishton [

33] ranks occlusion as the most important depth cue for near-field perception. This means that depth perception overall is decreased as the user often cannot decipher which object is in front of another. In addition, and as discussed in the background, HMDs still cannot faithfully represent all the cues needed to perceive an environment [

41].

The second issue is the effect of the restricted field of view (FOV) of commercial HMDs. This is particularly an issue where the amplitude of interactions is high, or higher than the FOV [

63]. We theorise that this is in part due to immersion being reduced when harsh boundaries of a narrow FOV interrupt natural interactions. This notion of immersion continues into the next themes.

4.2.2. Real Interactions are Multi-Modal

This theme discusses the observations and opportunities of multi-modal near-field interactions. It is a known matter that multi-modal interactions can perform better than uni-modal interactions but we confirm this for near-field interactions, provide specificity of what multi-modal interactions were investigated in our data corpus, and theorise a reason for this.

Gaze and tactile feedback were the key additional input modalities explored by studies in our data corpus where each was combined with hand gestures and evaluated relative to a uni-modal counterpart. Overall an increase in performance was observed but with various nuances in the effect. Gaze is naturally linked to hand gestures as a precursor interaction and using gaze to initiate an interaction with a hand gesture as a trigger has been shown to be effective [

63]. It is however, necessary to choose an appropriate combination of gaze and hand gesture to suit the task presented. Tactile feedback was shown to improve depth perception [

66] however one observation with tactile feedback was the trade off that developed between speed and accuracy. Different forms of tactile feedback could be chosen for tasks that require higher accuracy or faster completion [

66].

There are two main points to drawn from this theme, the first around how task dependent interactions are and while the studies we included in our data corpus present some suggestion there has been no work to evaluate AR interactions’ situational pros and cons and present any kind of taxonomy for how to choose appropriately for a given task.

Secondly, we come back to immersion. Real world interactions are multi-modal [

67], and as summarised at the start of the discussion there are two competing goals for developing AR experiences; replicating the real world and building on the real world. Interactions in AR are often trying to do both of these at the same time, in that real world interactions naturally have tactile feedback which is being simulated somehow in AR but also gaze is being used in combination with hand gestures to provide the user with interactions that are not possible in the real world. Sometimes gaze may be used to simulate a real world interaction or as a workaround for when a direct simulation is not possible, and these two ideas are not always distinct, but in every situation the aim is (indirectly maybe) to increase in immersion, which in turn increases performance.

4.2.3. Despite More Accurate Options Hand Gestures are Preferred for Near-Field Interactions

As discussed in the previous theme there are a multitude of different interactions available when designing for AR each with their own pros and cons, two interaction methods could out perform one another on different criteria. There is however, consensus that natural hand gestures (a wide group) are the preferred mode of interaction for near-field applications, despite becoming less effective at further ranges. This is still the case even when more accurate options, such as longer precise interactions or haptic hand tracking gloves, are available. The ease, naturalness, and speed of natural hand gestures is preferred over any accuracy gained by more precise but longer interactions or the use of wearables.

This raises two considerations firstly it reaffirms the need to choose interactions appropriate to the task and there will never be one interaction for every task in every situation. Secondly, some level of inaccuracy is tolerable or even preferred if the alternative is better accuracy but longer completion times or additional hardware.

This somewhat goes against the previous theme and multi-modal interactions as without any additional hardware haptic feedback (shown to be effective at improving depth perception) cannot be provided. However, if a ’good enough’ interaction can be achieved using a different second interaction mode or simply using hand gestures alone, then the experience is not hindered by the subtle inaccuracy. For surgical applications however, or any other scenario with a manual task and where accuracy is of highest priority, the extra time or additional hardware may still be worth the cost to the experience.

Avatarisation, Perception, and Embodiment

It was made clear from the studies within our data corpus that a significant source of error for interactions in OST AR is a difference in the interacting layer and the visible layer. The visible layer being the effector that the user can see when performing an action, the interacting layer being what the HMD ’sees’ and what is used to determine whether or not a collision has occurred between the effector and the object. This is not an issue that occurs in VST AR as the visible layer is replicated from the interacting layer and presented to the user. It is also an issue likely exaggerated in near-field interactions due to the interaction point being much closer than the focal depth of the HMD, as discussed previously.

Studies within our data corpus investigated avatarising users’ end effectors (hands) in OST AR to approach this issue and came away concluding that avatarising end effectors can improve interaction performance regardless of the avatar fidelity. Even a crude avatar overlay over the user’s hand could improve performance due to the visible and interaction layers aligning.

This links back to the points made on immersion in the first two themes. Avatarising effectors can be argued to improve immersion and embodiment, which has positive effects on interaction efficacy, especially as the effectiveness of interaction techniques has been shown to change with the degree of physicality [

68,

69]. This is evidence that the more a user is immersed in an AR experience, the more they feel they embody the ’character’ they play in an AR experience, the better the interactions and the better the experience they will have. It can be argued that all the techniques covered in this review are techniques that aim to increase a user’s level of immersion. Both design techniques employed to replicate realistic cues, and interaction techniques working around obstacles to realism or going beyond realistic bounds, as mentioned at the start of this section.

Further work needs to be done to investigate the full effects of avatarisation on interaction efficacy in the near-field, but its role in improving levels of immersion and in turn interaction efficacy is undoubted.

4.2.4. Depth is the Main Contributor to Perceptual Inaccuracy, Particularly in the Near-Field

Depth perception was one of the main issues investigated by the studies in our data corpus and we suggest it here as the main contributor to perceptual inaccuracy for near-field interactions. This is an effect of near-field interactions being a long way from the fixed focal depth of commercial HMDs, as discussed in the background and throughout this review. Challengingly, the depth bias has been noted in both positive and negative directions. This means that an object can appear either nearer or further away than it actually is.

Design Techniques used to Alleviate Depth Estimation Errors in the Near-Field

Design techniques are largely focused on replicating the real world to improve realism and immersion in AR experiences and it is the perception of depth where their efforts have most frequently been applied. Depth cues are difficult to replicate for virtual objects in AR, therefore design techniques are employed to either better replicate real world depth cues, or to provide the user with additional information with which they can make a judgement on the depth of an object [

62,

70]. However, design techniques were also used to more directly address the clarity of the virtual components [

71]. There is little cohesion in the techniques employed within the studies included in our data corpus and more research is required to be able to suggest any kind of guidelines for what design techniques to use in a given situation.

Some key findings are listed here:

Correct estimation of depth is possible without occlusion (although with lower confidence) if all other depth cues are preserved.

Virtual objects that are less opaque and have higher contrast are easier to align with physical counterparts.

Virtual object size and brightness can affect depth estimation.

Sharpening algorithms can aid perception of virtual objects that are much closer than the fixed focal depth.

Complex occluding surfaces negatively impact perception of objects beneath, but virtual holes in the surface can help.

4.2.5. Perception is personal and made up of a multitude of factors

This final theme reiterates the known entity of how personal perception is and brings it into the context of near-field. The first point here observed through our analysis is that perception is a personal experience with many factors effecting it, but crucially it cannot be measured directly, only via a participant’s response. The researcher is never going to know exactly what the participant sees, instead they must measure the effects of empirical observations from a participant. Further to this there are a large number of factors that effect a user’s perception, both physical variations such as age but also the personal choices and experiences. The preferred interaction technique for a situation may vary between users, some interaction techniques can cause physical exertion, a factor that will affect users, and therefore interaction efficacy, differently. Interaction techniques can also have different affects on perception, which adds further variability.

Beyond the personal nature of perception, it is a difficult area to research as it has so many components it is difficult to isolate and investigate them individually. This goes for perceptual cues individually but also we have found design and interaction techniques are linked making it difficult to investigate either independently. This links to the previous theme and the use of design techniques to aid depth estimation, as there are so many factors involved when investigating this area it is challenging to make strong conclusions and suggestions.

5. Discussion

Here we summarise our results and how they address our research question, highlight our contribution, and suggest directions for future work.

5.1. Summary of Results and Contribution

Our results showed that of the studies included in this review there was a near 50:50 split between the two categories

design technique applied to perceptual issue and

interaction technique applied to perceptual issue with all papers involving empirical user studies. A variety of HMDs were used but mostly the Microsoft HoloLens 2, with all but one study focussing on OST technology [

66]. The definition of near-field varied, but all studies conducted their tasks within 25 and 100 cm in front of the user.

Through the inductive content analysis of the data we presented five themes and two sub-themes as listed below.

Hardware effects of limitations for near-field

Real interactions are multi-modal

-

Despite more accurate options, hand gestures are preferred for near-field interactions

-

Depth is the main contributor to perceptual inaccuracy, particularly in the near-field

Perception is personal and made up of a multitude of factors

For the this review we asked the research question “how can virtual design or interaction techniques be used to alleviate perceptual issues in near-field augmented reality?". These themes characterise various concepts that contextualise insights in line with this question and aim to answer it. Some elements discussed confirm some known concepts into the context of near-field interactions, as well as addressing the research question more directly.

Embodiment and immersion is raised throughout and it is clear that a more immersive experience contributes to improved interactions. While this may not directly address the research question it can be used as a proxy or adjacent goal for AR experiences. It is design and interaction techniques that address perceptual issues or enhance an experience, and a more immersive experience with users feeling stronger embodiment that affords users more natural, precise interactions.

Our results showed how design and interaction techniques are applied differently to effectively address different goals. It was observed that building AR experiences comes with two goals, replicating the real world to enable believable immersive experiences, and enhancing real world capability via the AR technology; and the use of design and interaction techniques can be seen to coincide with this. Design techniques tend to be employed to represent the real world better or work around hardware restrictions to provide the user with more information when understanding their experience. Whereas interaction techniques generally enable experiences that are not possible in the real world, affording the user the opportunity to interact in a different way. There is cross over here, for example where interactions that are not possible in the same way in AR (such as the natural feedback from touching an object) are worked around with different interaction techniques enabled by AR technology [

66].

Here we highlight these two findings from this review: The adoption of immersion and embodiment as a key goal when evaluating interactions in near-field augmented reality, and the acknowledgement of two competing goals for AR experiences - replication, and advancement. In addition, we found no further definition for near-field interactions across out data corpus other than the arm’s length" or up to two metres suggested by Cutting and Vishton [

33] with studies conducted at a range of distances. In response to this we advocate for future research to converge on using a range of 25-100 cm in front of the user for studies involving near-field interactions. Closer than this, and even without the use of AR, reading becomes difficult, further than this is further than the average person’s arm length and gets closer to the two metre fixed focal depth of most commercial HMDs for perceptual issues to reduce [

39,

72]. This range is indicative of ranges that the studies included in this review were conducted within. Similarly, the upper boundary of the “comfortable viewing zone" [

73] recommended by Microsoft for the HoloLens 2 is 125 cm, and thus is commensurate.

For this review was also asked two sub-questions "Is near-field perception better in VST than OST?" and “What techniques are being used to work within commercial HMDs?". This first question we are not in a position to answer as only one paper included in our data corpus used a VST HMD. This is an areas that need further work, as discussed in the next section. We asked the second question aiming to have some initial advice for developers and designers of AR applications in this space. We have attempted to answer this question throughout the results section but it is clear that there is a lot more research to do in this area before clear guidance can be given for these developers and designers.

5.2. Research Opportunities

As illustrated by the small number of studies included in our data corpus, this is an under researched area that would benefit from increased attention. Going forwards, using commercially available HMDs is going to be the most accessible option and therefore until hardware issues and limitations such as the fixed focal depth (amongst other things) can be overcome, we must work within their bounds. How design and interaction techniques are employed to work around these limitations and create better experiences will be invaluable.

Secondly, and in tandem with this first point a wide scale, generalisable evaluation of different interaction techniques, their pros and cons, and their applicability to different scenarios would be valuable to designers creating AR experiences in making informed decisions about what techniques should be used in different situations. This could result in a taxonomy being produced that designers of AR experiences could call upon when developing for different scenarios.

Finally, it is clear that the commercial market is moving away from OST HMDs and towards VST devices [

74] however the studies available at the time of this review are very OST focussed. This illustrates a wider shift in the AR scene around how Microsoft (amongst others) grabbed the AR scene with the HoloLens in 2016, but since then the world has shifted away from this technology towards VST instead. Microsoft have dropped the HoloLens 2 and any plans for a third generation device and the market leaders now mostly produce VST devices, Meta with the Quest 3 and Apple with the Vision Pro being the biggest examples. How current research in this area and the taxonomy called for above translates to VST is unclear. Can VR guidelines be drawn on? How do they need to be adapted for VST AR? How does existing research in OST design and interaction transfer to VST? Future research must investigate this.

6. Conclusion

We present a scoping literature review of seven studies that investigate design or interaction techniques to address perceptual challenges for near-field augmented reality. We reviewed the papers with a two phase approach, both with a deductive code book and inductive content analysis. We contribute a series of key findings that address our research question, and go on to suggest threes areas for future research and give reasons for these.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Syed, T.A.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Abdullah, H.B.; Jan, S.; Namoun, A.; Alzahrani, A.; Nadeem, A.; Alkhodre, A.B. In-Depth Review of Augmented Reality: Tracking Technologies, Development Tools, AR Displays, Collaborative AR, and Security Concerns. Sensors 2023, 23, 146, Number: 1 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arena, F.; Collotta, M.; Pau, G.; Termine, F. An Overview of Augmented Reality. Computers 2022, 11, 28, Number: 2 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reljić, V.; Milenković, I.; Dudić, S.; Šulc, J.; Bajči, B. Augmented Reality Applications in Industry 4.0 Environment. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 5592, Number: 12 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing

Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Ramírez, C.E.; Tudon-Martinez, J.C.; Félix-Herrán, L.C.; Lozoya-Santos, J.d.J.; Vargas-Martínez, A. Augmented Reality: Survey. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 10491, Number: 18 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, T.; Evangelidis, K.; Kaskalis, T.H.; Evangelidis, G.; Sylaiou, S. Interactions in Augmented and Mixed Reality: An Overview. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 8752, Number: 18 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, E.A. The Perceptual Science of Augmented Reality. Annual Review of Vision Science 2023, 9, 455–478, Publisher: Annual Reviews. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bremers, A.W.D.; Yöntem, A.; Li, K.; Chu, D.; Meijering, V.; Janssen, C.P. Perception of perspective in augmented reality head-up displays. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 2021, 155, 102693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, A.K. Virtual and augmented reality: Human sensory-perceptual requirements and trends for immersive spatial computing experiences. Journal of the Society for Information Display 2024, 32, 605–646, _eprint: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/jsid.2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Lin, Y.H. Liquid crystal technology for vergence-accommodation conflicts in augmented reality and virtual reality systems: a review. Liquid Crystals Reviews 2021, 9, 35–64, Publisher: Taylor & Francis _eprint: https://doi.org/10.1080/21680396.2021.1948927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, Y.; Langlotz, T.; Sutton, J.; Plopski, A. Towards Indistinguishable Augmented Reality: A Survey on Optical See-through Head-mounted Displays. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 120:1–120:36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, C.; Walker, M.; Szafir, D.A.; Szafir, D. Designing for Depth Perceptions in Augmented Reality. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), 2017, pp. 111–122. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 2018, 169, 467–473, Publisher: American College of Physicians. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoping.

- Cooper, S.; Cant, R.; Kelly, M.; Levett-Jones, T.; McKenna, L.; Seaton, P.; Bogossian, F. An Evidence-Based Checklist for Improving Scoping Review Quality. Clinical Nursing Research 2021, 30, 230–240, SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis - JBI Global Wiki.

- Sutherland, I. The Ultimate Display 1965.

- McCarthy, C.J.; Uppot, R.N. Advances in Virtual and Augmented Reality—Exploring the Role in Health-care Education. Journal of Radiology Nursing 2019, 38, 104–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Hirata, H.; Otani, K.; Sugimoto, M.; Tsukamoto, M.; Yoshihara, T.; Ueno, M.; Mawatari, M. XR (Extended Reality: Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, Mixed Reality) Technology in Spine Medicine: Status Quo and Quo Vadis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 470, Number: 2 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speicher, M.; Hall, B.D.; Nebeling, M. What is Mixed Reality? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 2019; CHI ’19, pp. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Vinci, C.; Brandon, K.O.; Kleinjan, M.; Brandon, T.H. The clinical potential of augmented reality. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2020, 27, e12357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudell, T.; Mizell, D. Augmented reality: an application of heads-up display technology to manual manufacturing processes. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Kauai, HI, USA, 1992; pp. 659–669 vol.2. [CrossRef]

- Javornik, A. The Mainstreaming of Augmented Reality: A Brief History, 2016.

- Vertucci, R.; D’Onofrio, S.; Ricciardi, S.; De Nino, M. History of Augmented Reality. In Springer Handbook of Augmented Reality; Nee, A.Y.C.; Ong, S.K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 35–50. [CrossRef]

- lolambean. HoloLens (1st gen) hardware.

- Google Trends: Understanding the data. - Google News Initiative.

- HTC Vive: Full Specification.

- Pokémon, GO.

- Launch of new IKEA Place app – IKEA Global.

- Google Glass smart eyewear returns. BBC News 2017.

- Dargan, S.; Bansal, S.; Kumar, M.; Mittal, A.; Kumar, K. Augmented Reality: A Comprehensive Review. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2023, 30, 1057–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.V.; Huang, H.C.; Teather, R.J.; Chuang, J.H. Comparing the Fidelity of Contemporary Pointing with Controller Interactions on Performance of Personal Space Target Selection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), 2022, pp. 404–413. ISSN: 1554-7868. [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.; Tsai, M.H.; Hsu, T.W.; Chuang, J.H. An Evaluation of the Efficiency of Popular Personal Space Pointing versus Controller based Spatial Selection in VR. In Proceedings of the ACM Symposium on Applied Perception 2020, New York, NY, USA, 2020; SAP ’20. event-place: Virtual Event, USA. [CrossRef]

- Cutting, J.E.; Vishton, P.M. Chapter 3 - Perceiving Layout and Knowing Distances: The Integration, Relative Potency, and Contextual Use of Different Information about Depth*. In Perception of Space and Motion; Epstein, W.; Rogers, S., Eds.; Handbook of Perception and Cognition, Academic Press: San Diego, 1995; pp. 69–117. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Doyle, D.; Moreu, F. State of the art of augmented reality capabilities for civil infrastructure applications. Engineering Reports 2023, 5, e12602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutis, I.; Ambekar, A. Challenges and enablers of augmented reality technology for in situ walkthrough applications. Journal of Information Technology in Construction (ITcon) 2020, 25, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutolo, F.; Fida, B.; Cattari, N.; Ferrari, V. Software Framework for Customized Augmented Reality Headsets in Medicine. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 706–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; He, Z.; Xiong, J.; Zou, J.; Li, K.; Wu, S.T. Virtual reality and augmented reality displays: advances and future perspectives. Journal of Physics: Photonics 2021, 3, 022010, Publisher: IOP Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, Y.; Langlotz, T.; Sutton, J.; Plopski, A. Towards Indistinguishable Augmented Reality: A Survey on Optical See-through Head-mounted Displays. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 120–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkelens, I.M.; MacKenzie, K.J. 19-2: Vergence-Accommodation Conflicts in Augmented Reality: Impacts on Perceived Image Quality. SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers 2020, 51, 265–268, _eprint: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/sdtp.13855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blignaut, J.; Venter, M.; van den Heever, D.; Solms, M.; Crockart, I. Inducing Perceptual Dominance with Binocular Rivalry in a Virtual Reality Head-Mounted Display. Mathematical and Computational Applications 2023, 28, 77, Number: 3 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argelaguet, F.; Andujar, C. A survey of 3D object selection techniques for virtual environments. Computers & Graphics 2013, 37, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.J.E.; Chand, M.; Birlo, M.; Stoyanov, D. The Challenge of Augmented Reality in Surgery. In Digital Surgery; Atallah, S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 121–135. [CrossRef]

- Reichelt, S.; Häussler, R.; Fütterer, G.; Leister, N. Depth cues in human visual perception and their realization in 3D displays. In Proceedings of the Three-Dimensional Imaging, Visualization, and Display 2010 and Display Technologies and Applications for Defense, Security, and Avionics IV. SPIE, 2010, Vol. 7690, pp. 92–103. [CrossRef]

- Dror, I.E.; Schreiner, C.S. Chapter 4 - Neural Networks and Perception. In Advances in Psychology; Jordan, J.S., Ed.; North-Holland, 1998; Vol. 126, Systems Theories and a Priori Aspects of Perception, pp. 77–85. [CrossRef]

- Marcos, S.; Moreno, E.; Navarro, R. The depth-of-field of the human eye from objective and subjective measurements. Vision Research 1999, 39, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, S.R.; Menges, B.M. Localization of Virtual Objects in the Near Visual Field. Human Factors 1998, 40, 415–431, Publisher: SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sielhorst, T.; Bichlmeier, C.; Heining, S.M.; Navab, N. Depth Perception – A Major Issue in Medical AR: Evaluation Study by Twenty Surgeons. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2006; Larsen, R.; Nielsen, M.; Sporring, J., Eds., Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006; pp. 364–372. [CrossRef]

- Ballestin, G.; Solari, F.; Chessa, M. Perception and Action in Peripersonal Space: A Comparison Between Video and Optical See-Through Augmented Reality Devices. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct), 2018, pp. 184–189. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, T.J.; Mayer, W.; Zucco, J.E.; Matthews, B.J.; Smith, R.T. Adapting VST AR X-Ray Vision Techniques to OST AR. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct), 2022, pp. 495–500. ISSN: 2771-1110. [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.M.; Stuerzlinger, W. Is the Pen Mightier than the Controller? A Comparison of Input Devices for Selection in Virtual and Augmented Reality. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 25th ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, New York, NY, USA, 2019; VRST ’19, pp. 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kwon, Y.T.; Lim, H.R.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Yeo, W.H. Recent Advances in Wearable Sensors and Integrated Functional Devices for Virtual and Augmented Reality Applications. Advanced Functional Materials 2021, 31, 2005692, _eprint: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/adfm.202005692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J.; Shin, J.h.; Ponto, K. A Comparative Analysis of 3D User Interaction: How to Move Virtual Objects in Mixed Reality. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), 2020, pp. 275–284. ISSN: 2642-5254. [CrossRef]

- Prilla, M.; Janssen, M.; Kunzendorff, T. How to Interact with Augmented Reality Head Mounted Devices in Care Work? A Study Comparing Handheld Touch (Hands-on) and Gesture (Hands-free) Interaction. AIS Transactions on Human-Computer Interaction 2019, 11, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seinfeld, S.; Feuchtner, T.; Pinzek, J.; Müller, J. Impact of Information Placement and User Representations in VR on Performance and Embodiment. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 2022, 28, 1545–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genay, A.; Lécuyer, A.; Hachet, M. Being an Avatar “for Real”: A Survey on Virtual Embodiment in Augmented Reality. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 2022, 28, 5071–5090. https://doi.org/Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews Pollock et al. 2023, JBI Evidence Synthesis, 21(3): 520–532.

- Hammady, R.; Ma, M.; Strathearn, C. User experience design for mixed reality: a case study of HoloLens in museum. International Journal of Technology Marketing 2019, 13, 354–375, Publisher: Inderscience Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, A.; Clowes, M.; Preston, L.; Booth, A. Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health Information & Libraries Journal 2019, 36, 202–222, _eprint: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/hir.12276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oun, A.; Hagerdorn, N.; Scheideger, C.; Cheng, X. Mobile Devices or Head-Mounted Displays: A Comparative Review and Analysis of Augmented Reality in Healthcare. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 21825–21839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirzle, T.; Müller, F.; Draxler, F.; Schmitz, M.; Knierim, P.; Hornbæk, K. When XR and AI Meet - A Scoping Review on Extended Reality and Artificial Intelligence. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 2023; CHI ’23. event-place: <conf-loc>, <city> Hamburg</city>, <country>Germany</country>, </conf-loc>. [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI evidence synthesis 2023, 21, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinheksel, A.J.; Rockich-Winston, N.; Tawfik, H.; Wyatt, T.R. Demystifying Content Analysis. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 2020, 84, 7113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Leuze, C.; Perkins, S.; Rosenberg, J.; Daniel, B.; Martin-Gomez, A. Evaluation of Different Visualization Techniques for Perception-Based Alignment in Medical AR. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct), 2020, pp. 45–50. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, U.; Lystbæk, M.N.; Manakhov, P.; Grønbæk, J.E.S.; Pfeuffer, K.; Gellersen, H. A Fitts’ Law Study of Gaze-Hand Alignment for Selection in 3D User Interfaces. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 2023; CHI ’23. event-place: <conf-loc> ,<city> Hamburg</city>, <country>Germany,</country>, </conf-loc>. [CrossRef]

- Weast, R.A.T.; Proffitt, D.R. Can I reach that? Blind reaching as an accurate measure of estimated reachable distance. Consciousness and Cognition 2018, 64, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.G. Nasa-Task Load Index (NASA-TLX); 20 Years Later. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 2006, 50, 904–908, Publisher: SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, N.; Hürst, W.; Werkhoven, P.; Veltkamp, R. Visuotactile integration for depth perception in augmented reality. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 18th ACM International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 2016; ICMI ’16, pp. 45–52. event-place: Tokyo, Japan. event-place: Tokyo, Japan. [CrossRef]

- Quek, F.; McNeill, D.; Bryll, R.; Duncan, S.; Ma, X.F.; Kirbas, C.; McCullough, K.E.; Ansari, R. Multimodal human discourse: gesture and speech. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2002, 9, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatakrishnan, R.; Venkatakrishnan, R.; Canales, R.; Raveendranath, B.; Pagano, C.C.; Robb, A.C.; Lin, W.C.; Babu, S.V. Investigating the Effects of Avatarization and Interaction Techniques on Near-field Mixed Reality Interactions with Physical Components. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 2024, 30, 2756–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatakrishnan, R.; Venkatakrishnan, R.; Raveendranath, B.; Pagano, C.C.; Robb, A.C.; Lin, W.C.; Babu, S.V. Give Me a Hand: Improving the Effectiveness of Near-field Augmented Reality Interactions By Avatarizing Users’ End Effectors. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 2023, 29, 2412–2422, Conference Name: IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Rosenberg, J.; Leuze, C.; Hargreaves, B.; Daniel, B. The Impact of Occlusion on Depth Perception at Arm’s Length. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 2023, 29, 4494–4502, Conference Name: IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, K.; Moser, K.R.; Rompapas, D.C.; Swan, J.E.; Ikeda, S.; Yamamoto, G.; Taketomi, T.; Sandor, C.; Kato, H. SharpView: Improved clarity of defocused content on optical see-through head-mounted displays. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Symposium on 3D User Interfaces (3DUI), 2016, pp. 173–181. [CrossRef]

- Katz, M. Convergence Demands by Spectacle Magnifiers. Optometry and Vision Science 1996, 73, 540.

- Microsoft. Comfort - Mixed Reality, 2021.

- Feld, N.; Pointecker, F.; Anthes, C.; Zielasko, D. Perceptual Issues in Mixed Reality: A Developer-oriented Perspective on Video See-Through Head-Mounted Displays. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct), 2024, pp. 170–175. ISSN: 2771-1110. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).