Submitted:

11 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Molecular Detection and Genotyping of O. tsutsugamushi

2.3.1. Genomic DNA Extraction and GroEL Gene Amplification

2.3.2. Amplification of the 56 kDa Type-Specific Antigen Gene

2.3.3. Sequence Editing, BLAST Analysis, and GenBank Submission

2.3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

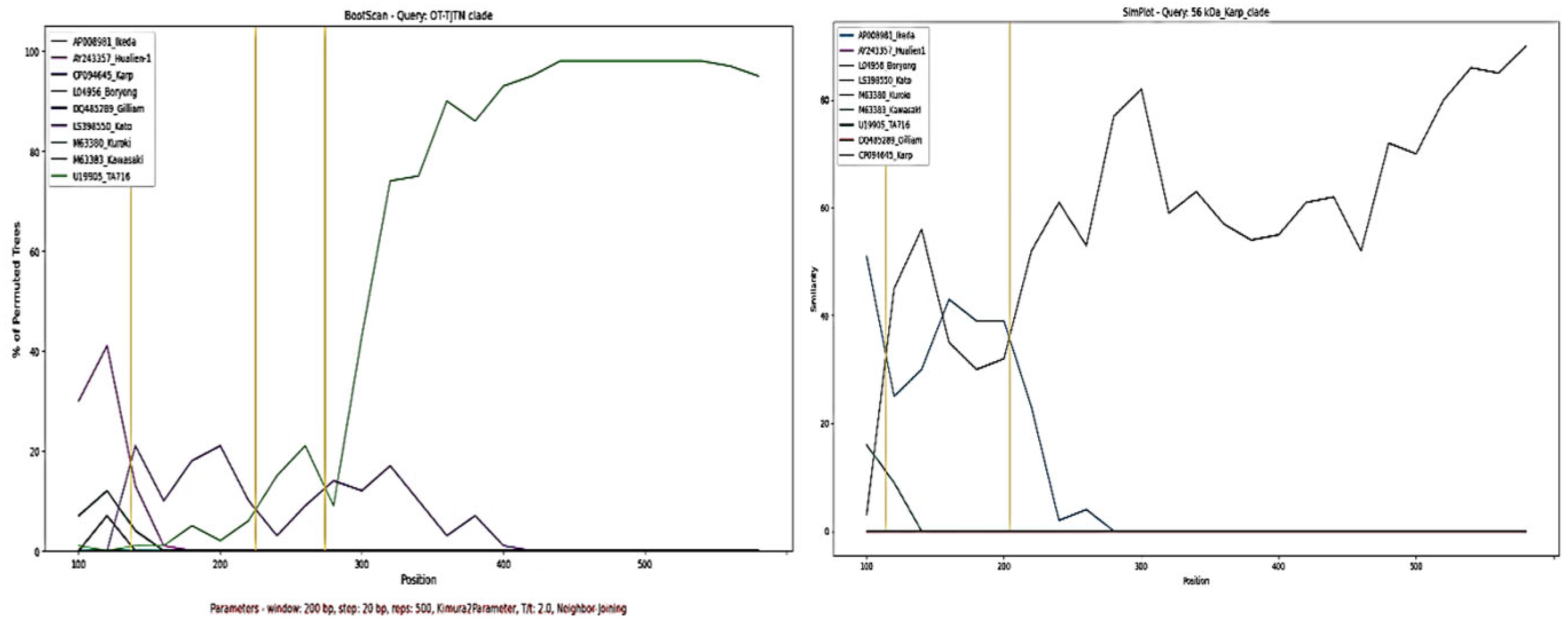

2.3.5. Similarity and Bootscan Analysis of 56 kDa Sequences

3. Results

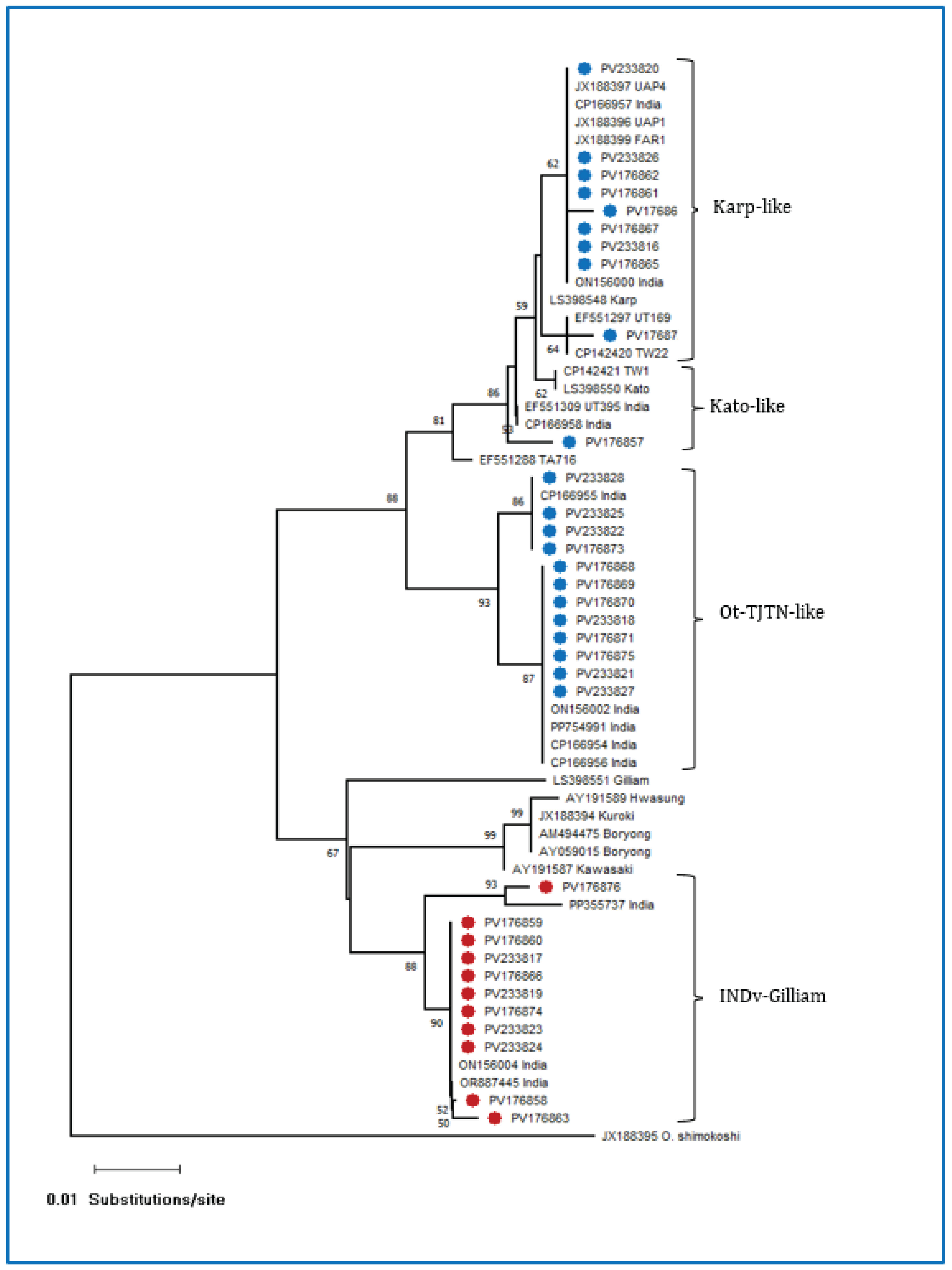

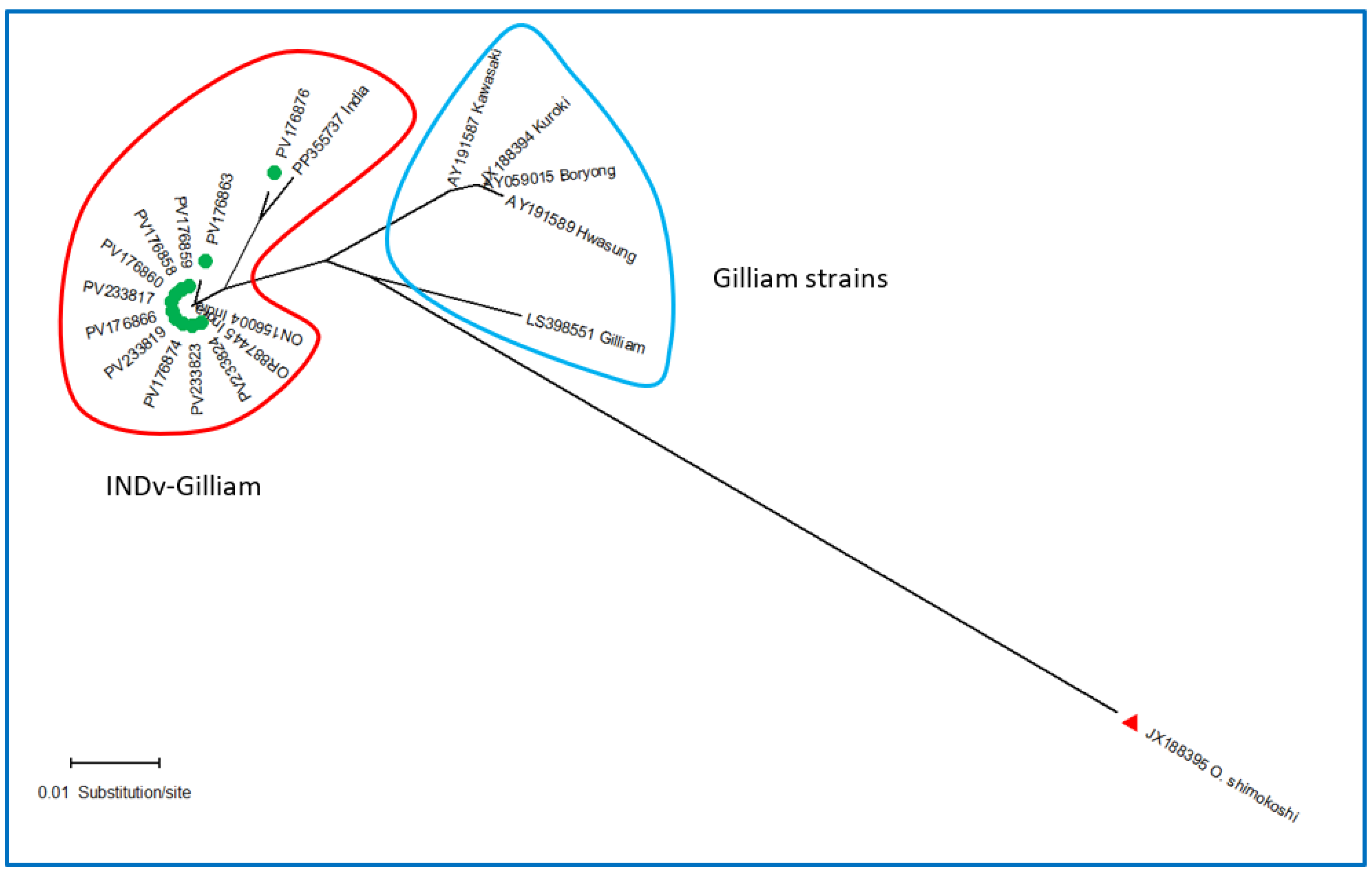

3.1. Molecular Detection and GroEL Gene Sequence Analysis

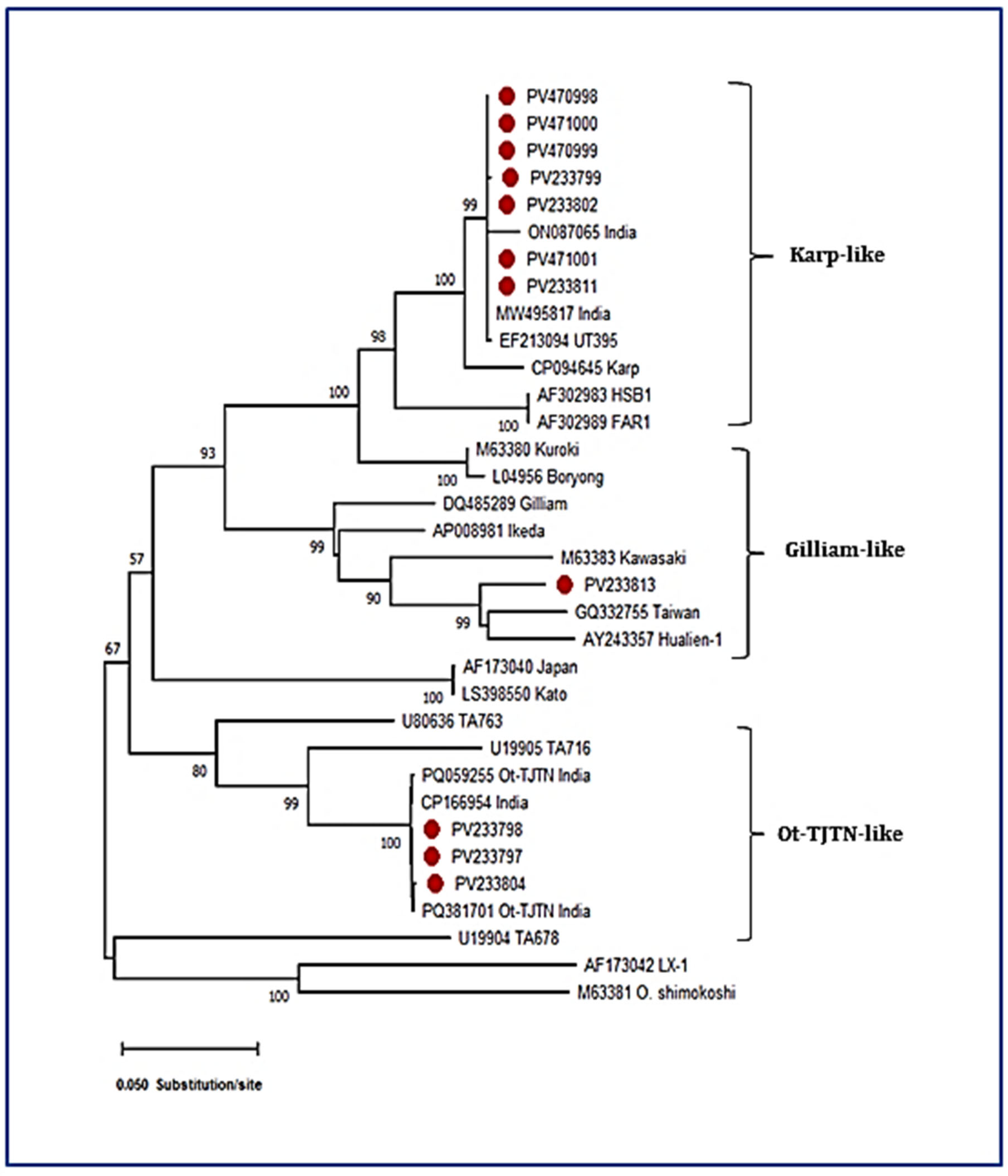

3.2. Sequence Analysis of the TSA 56 kDa Antigen Gene

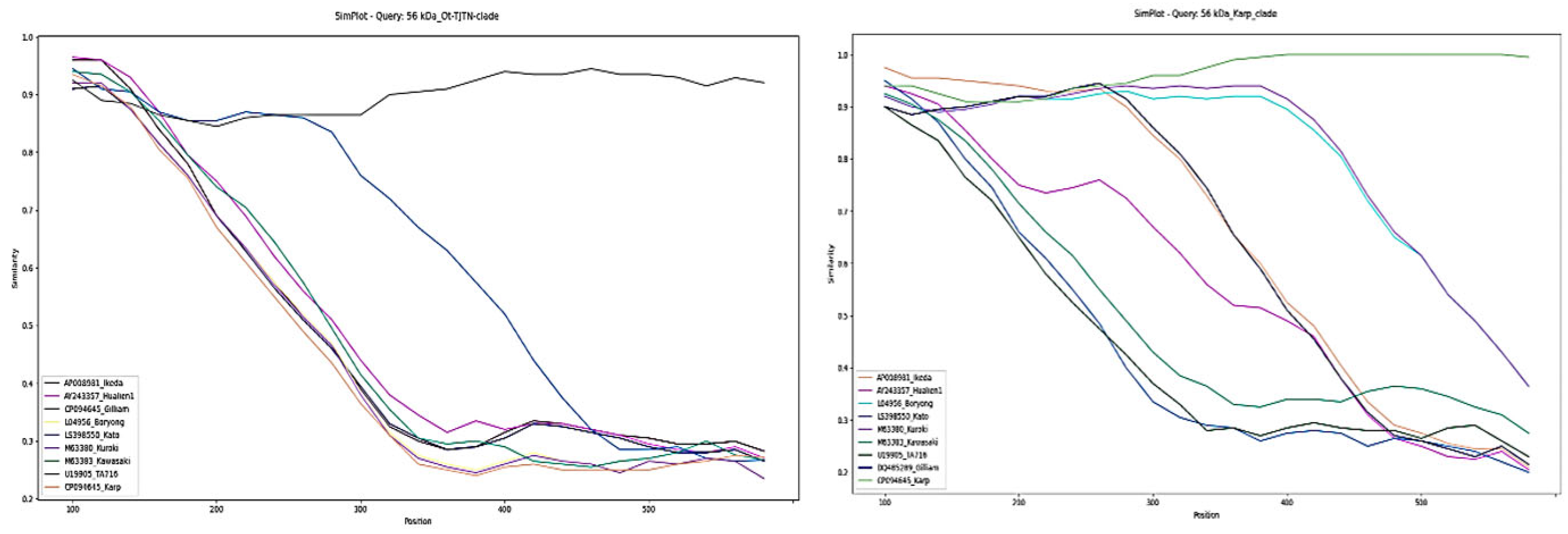

3.3. Similarity Plot and Recombination Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, G.; Walker, D.H.; Jupiter, D.; Melby, P.C.; Arcari, C.M. A Review of the Global Epidemiology of Scrub Typhus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11, e0006062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerdthusnee, K.; Khlaimanee, N.; Monkanna, T.; Sangjun, N.; Mungviriya, S.; Linthicum, K.J.; Frances, S.P.; Kollars, T.M.; Coleman, R.E. Efficiency of Leptotrombidium Chiggers (Acari: Trombiculidae) at Transmitting Orientia Tsutsugamushi to Laboratory Mice. J Med Entomol 2002, 39, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzard, L.; Fuller, A.; Blacksell, S.D.; Paris, D.H.; Richards, A.L.; Aukkanit, N.; Nguyen, C.; Jiang, J.; Fenwick, S.; Day, N.P.J.; et al. Isolation of a Novel Orientia Species ( O. Chuto Sp. Nov.) from a Patient Infected in Dubai. J Clin Microbiol 2010, 48, 4404–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abarca, K.; Martínez-Valdebenito, C.; Angulo, J.; Jiang, J.; Farris, C.M.; Richards, A.L.; Acosta-Jamett, G.; Weitzel, T. Molecular Description of a Novel Orientia Species Causing Scrub Typhus in Chile. Emerg Infect Dis 2020, 26, 2148–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.J.; Paris, D.H.; Newton, P.N. A Systematic Review of Mortality from Untreated Scrub Typhus (Orientia Tsutsugamushi). PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9, e0003971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, G.M.; Trowbridge, P.; Janardhanan, J.; Thomas, K.; Peter, J.V.; Mathews, P.; Abraham, O.C.; Kavitha, M.L. Clinical Profile and Improving Mortality Trend of Scrub Typhus in South India. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2014, 23, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonthayanon, P.; Peacock, S.J.; Chierakul, W.; Wuthiekanun, V.; Blacksell, S.D.; Holden, M.T.G.; Bentley, S.D.; Feil, E.J.; Day, N.P.J. High Rates of Homologous Recombination in the Mite Endosymbiont and Opportunistic Human Pathogen Orientia Tsutsugamushi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010, 4, e752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, D.H.; Shelite, T.R.; Day, N.P.; Walker, D.H. Unresolved Problems Related to Scrub Typhus: A Seriously Neglected Life-Threatening Disease. The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2013, 89, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, E.M.; Chaemchuen, S.; Blacksell, S.; Richards, A.L.; Paris, D.; Bowden, R.; Chan, C.; Lachumanan, R.; Day, N.; Donnelly, P.; et al. Long-Read Whole Genome Sequencing and Comparative Analysis of Six Strains of the Human Pathogen Orientia Tsutsugamushi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018, 12, e0006566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.J.; Fuerst, P.A.; Ching, W.; Richards, A.L. Scrub Typhus: The Geographic Distribution of Phenotypic and Genotypic Variants of Orientia Tsutsugamushi. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2009, 48, S203–S230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valbuena, G.; Walker, D.H. Approaches to Vaccines against Orientia Tsutsugamushi. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2013, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, G.M.; Janardhanan, J.; Mahajan, S.K.; Tariang, D.; Trowbridge, P.; Prakash, J.A.J.; David, T.; Sathendra, S.; Abraham, O.C. Molecular Epidemiology and Genetic Diversity of Orientia Tsutsugamushi from Patients with Scrub Typhus in 3 Regions of India. Emerg Infect Dis 2015, 21, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devamani, C.S.; Prakash, J.A.J.; Alexander, N.; Stenos, J.; Schmidt, W.-P. The Incidence of Orientia Tsutsugamushi Infection in Rural South India. Epidemiol Infect 2022, 150, e132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Bora, T.; Laskar, B.; Khan, A.M.; Dutta, P. Scrub Typhus Leading to Acute Encephalitis Syndrome, Assam, India. Emerg Infect Dis 2017, 23, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonell, A.; Lubell, Y.; Newton, P.N.; Crump, J.A.; Paris, D.H. Estimating the Burden of Scrub Typhus: A Systematic Review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11, e0005838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nallan, K.; Kalidoss, B.C.; Jacob, E.S.; Mahadevan, S.K.; Joseph, S.; Ramalingam, R.; Renu, G.; Thirupathi, B.; Ramasamy, B.; Gupta, B.; et al. A Novel Genotype of Orientia Tsutsugamushi in Human Cases of Scrub Typhus from Southeastern India. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruang-areerate, T.; Jeamwattanalert, P.; Rodkvamtook, W.; Richards, A.L.; Sunyakumthorn, P.; Gaywee, J. Genotype Diversity and Distribution of Orientia Tsutsugamushi Causing Scrub Typhus in Thailand. J Clin Microbiol 2011, 49, 2584–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, S.; Tabara, K.; Yamamoto, N.; Fujita, H.; Itagaki, A.; Kon, M.; Satoh, H.; Araki, K.; Tanaka-Taya, K.; Takada, N.; et al. Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis of Orientia Tsutsugamushi Based on the GroES and GroEL Genes. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 2013, 13, 825–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaiah, A.; Koralur, M.C.; Dasch, G.A. Complexity of Type-Specific 56 KDa Antigen CD4 T-Cell Epitopes of Orientia Tsutsugamushi Strains Causing Scrub Typhus in India. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0196240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nallan, K.; Rajan, G.; Sivathanu, L.; Devaraju, P.; Thiruppathi, B.; Kumar, A.; Rajaiah, P. Molecular Detection of Multiple Genotypes of Orientia Tsutsugamushi Causing Scrub Typhus in Febrile Patients from Theni District, South India. Trop Med Infect Dis 2023, 8, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trend Of Scrub Typhus In Tamil Nadu-2021-2023 (Based On Ihip Data).

- Li, W.; Dou, X.; Zhang, L.; Lyu, Y.; Du, Z.; Tian, L.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Guan, Z.; Chen, L.; et al. Laboratory Diagnosis and Genotype Identification of Scrub Typhus from Pinggu District, Beijing, 2008 and 2010. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013, 89, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, S.; Lord, É.; Makarenkov, V. SimPlot++: A Python Application for Representing Sequence Similarity and Detecting Recombination. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 3118–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phetsouvanh, R.; Sonthayanon, P.; Pukrittayakamee, S.; Paris, D.H.; Newton, P.N.; Feil, E.J.; Day, N.P.J. The Diversity and Geographical Structure of Orientia Tsutsugamushi Strains from Scrub Typhus Patients in Laos. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9, e0004024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, V.; Blassdell, K.; May, T.T.X.; Sreyrath, L.; Gavotte, L.; Morand, S.; Frutos, R.; Buchy, P. Diversity of Orientia Tsutsugamushi Clinical Isolates in Cambodia Reveals Active Selection and Recombination Process. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2013, 15, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.R.; Tsai, H.P.; Tsui, P.Y.; Weng, M.H.; Kuo, M.D.; Lin, H.C.; Chen, K.C.; Ji, D.D.; Chu, D.M.; Liu, W.T. Genetic Typing, Based on the 56-Kilodalton Type-Specific Antigen Gene, of Orientia Tsutsugamushi Strains Isolated from Chiggers Collected from Wild-Caught Rodents in Taiwan. Appl Environ Microbiol 2011, 77, 3398–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.J.; Fuerst, P.A.; Richards, A.L. Origins, Importance and Genetic Stability of the Prototype Strains Gilliam, Karp and Kato of Orientia Tsutsugamushi. Trop Med Infect Dis 2019, 4, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, J.-R. Determinants of the Rate of Protein Sequence Evolution. Nat Rev Genet 2015, 16, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, D.H.; Aukkanit, N.; Jenjaroen, K.; Blacksell, S.D.; Day, N.P.J. A Highly Sensitive Quantitative Real-Time PCR Assay Based on the GroEL Gene of Contemporary Thai Strains of Orientia Tsutsugamushi. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2009, 15, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, N.; Nashimoto, H.; Ikeda, H.; Tamura, A. Diversity of Immunodominant 56-KDa Type-Specific Antigen (TSA) of Rickettsia Tsutsugamushi. Sequence and Comparative Analyses of the Genes Encoding TSA Homologues from Four Antigenic Variants. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1992, 267, 12728–12735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-H.; Huang, I.-T.; Lin, C.-H.; Chen, T.-Y.; Chen, L.-K. New Genotypes of Orientia Tsutsugamushi Isolated from Humans in Eastern Taiwan. PLoS One 2012, 7, e46997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chunduru, K.; A. R, M.; Poornima, S.; Hande H, M.; Devaki, R.; Varghese, G.M.; Saravu, K. Clinical, Laboratory Profile and Molecular Characterization of Orientia Tsutsugamushi among Fatal Scrub Typhus Patients from Karnataka, India. Infect Dis 2024, 56, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, D.J.; Fuerst, P.A.; Ching, W.; Richards, A.L. Scrub Typhus: The Geographic Distribution of Phenotypic and Genotypic Variants of Orientia Tsutsugamushi. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2009, 48, S203–S230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzard, L.; Fuller, A.; Blacksell, S.D.; Paris, D.H.; Richards, A.L.; Aukkanit, N.; Nguyen, C.; Jiang, J.; Fenwick, S.; Day, N.P.J.; et al. Isolation of a Novel Orientia Species ( O. Chuto Sp. Nov.) from a Patient Infected in Dubai. J Clin Microbiol 2010, 48, 4404–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frances, S.P.; Watcharapichat, P.; Phulsuksombati, D.; Tanskul, P. Transmission of Orientia Tsutsugamushi, the Aetiological Agent for Scrub Typhus, to Co-Feeding Mites. Parasitology 2000, 120, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, R.; Rajamannar, V.; Krishnamoorthi, R.; Kumar, A.; Samuel, P.P. Distribution Pattern of Chigger Mites in South Tamil Nadu, India. Entomon 2021, 46, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-W.; Lee, C.K.; Kwak, Y.G.; Moon, C.; Kim, B.-N.; Kim, E.S.; Kang, J.M.; Lee, C.-S. Antigenic Drift of Orientia Tsutsugamushi in South Korea as Identified by the Sequence Analysis of a 56-KDa Protein-Encoding Gene. The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2010, 83, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Ha, N.-Y.; Min, C.-K.; Kim, H.-I.; Yen, N.T.H.; Lee, K.-H.; Oh, I.; Kang, J.-S.; Choi, M.-S.; Kim, I.-S.; et al. Diversification of Orientia Tsutsugamushi Genotypes by Intragenic Recombination and Their Potential Expansion in Endemic Areas. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11, e0005408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sl No. | DNA Code | GenBank Acc. Nos. (Present Study) | Percentage Identity | Source | Country | Closest GenBank Acc. No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TH 05 | PV176858 | 100 100 98.11 96.96 |

Human Human Rodent Human |

India India India Korea |

ON156004 OR887445 PP355737 AY191587 |

| 2 | TH 10 | PV176859 | 100 100 96.98 96.98 |

Human Human Human Human |

India India Korea Korea |

ON156004 OR887445 AM494475 AY191587 |

| 3 | TH 16 | PV176860 | 100 96.9 96.9 96.9 |

Human Human Human Human |

India Korea India Korea |

ON156004 AY059015 CP166955 AY191587 |

| 4 | TH 28 | PV176863 | 99.73 96.7 96.7 |

Human Human Human |

India Korea Korea |

ON156004 AM494475 AY191587 |

| 5 | TH 45 | PV233817 | 100 98.11 96.98 96.98 |

Human Rodent Human Human |

India India Korea Korea |

ON156004 PP355737 AM494475 AY191587 |

| 6 | DM 03 |

PV176866 | 100 100 96.7 97 |

Human Human Human Human |

India India Korea Korea |

ON156004 OR887445 AM494475 AY191587 |

| 7 | DM 14 | PV233819 | 100 100 96.98 96.98 |

Human Human Human Human |

India India Korea Korea |

ON156004 |

| OR887445 | ||||||

| AM494475 | ||||||

| AY191587 | ||||||

| 8 | DM 30 | PV176874 | 100 | Human | India | ON156004 |

| 100 | Human | India | OR887445 | |||

| 96.99 | Human | Korea | AM494475 | |||

| 96.99 | Human | Korea | AY191587 | |||

| 9 | DM 33 | PV176876 | 98.63 | Human | India | ON156004 |

| 99.12 | Rodent | India | PP355737 | |||

| 96.16 | Human | Korea | AM494475 | |||

| 96.16 | Human | Korea | AY191587 | |||

| 10 | DM 43 | PV233823 | 100 | Human | India | ON156004 |

| 100 | Human | India | OR887445 | |||

| 96.98 | Human | Japan | JX188394 | |||

| 96.98 | Human | Korea | AY191587 | |||

| 96.98 | Human | Korea | AM494475 | |||

| 11 | DM 44 | PV233824 | 100 | Human | India | ON156004 |

| 100 | Human | India | OR887445 | |||

| 96.98 | Human | Japan | JX188394 | |||

| 96.98 | Human | Korea | AY191587 | |||

| 96.98 | Human | Korea | AM494475 |

| Genotype | INDv-Gilliam | Hwasung | Kawasaki | Gilliam | Kuroki | Boryong |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INDv-Gilliam | — | |||||

| Hwasung | 0.039 | — | ||||

| Kawasaki | 0.032 | 0.006 | — | |||

| Gilliam | 0.039 | 0.047 | 0.041 | — | ||

| Kuroki | 0.035 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.044 | — | |

| Boryong | 0.035 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.044 | 0.001 | — |

| Sl No. | DNA Code | GenBank Acc. Nos. (Present Study) | Percentage Identity | Source | Country | Closest GenBank Acc. No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TH 05 | PV233797 | 100 100 100 |

Human Human Human |

India India India |

PQ381701 PQ059255 CP166954 |

| 2 | TH 10 | PV233798 | 100 100 100 |

Human Human Human |

India India India |

PQ381701 PQ059255 CP166954 |

| 3 | DM 3 | PV233804 | 100 100 100 |

Human Human Human |

India India India |

PQ381701 PQ059255 CP166954 |

| 4 | TH 16 | PV233799 | 100 98.84 98.15 |

Human Human Human |

India India Thailand |

MW495817 ON087065 EF213094 |

| 5 | TH 28 | PV233802 | 100 98.84 98.15 |

Human Human Human |

India India Thailand |

MW495817 ON087065 EF213094 |

| 6 | TH 45 | PV470998 | 100 98.84 98.15 |

Human Human Human |

India India Thailand |

MW495817 ON087065 EF213094 |

| 7 | DM 43 | PV471000 | 100 98.84 98.15 |

Human Human Human |

India India Thailand |

MW495817 ON087065 EF213094 |

| 8 | DM 44 | PV471001 | 100 98.84 98.15 |

Human Human Human |

India India Thailand |

MW495817 ON087065 EF213094 |

| 9 | DM 14 | PV470999 | 100 98.84 98.15 |

Human Human Human |

India India Thailand |

MW495817 ON087065 EF213094 |

| 10 | DM 30 | PV233811 | 100 98.84 98.15 |

Human Human Human |

India India Thailand |

MW495817 ON087065 EF213094 |

| 11 | DM 33 | PV233813 | 95.14 93.93 93.93 93.93 92.03 |

Human Human Human Human Human |

Taiwan Taiwan China Taiwan Japan |

GQ332755 AY243357 MT258819 GQ332754 AP008981 |

| S. No | GenBank Accession. Nos. (GroEL) |

GroEL Genotype | GenBank Acc. Nos. (56 kDa) | 56kDa Genotype | Dual Genotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | PV176860 | INDv_Gilliam | PV233799 | Karp-like | INDv-Gilliam/Karp-like |

| 2. | PV176863 | INDv_Gilliam | PV233802 | Karp-like | INDv-Gilliam/Karp-like |

| 3. | PV233817 | INDv_Gilliam | PV470998 | Karp-like | INDv-Gilliam/Karp-like |

| 4. | PV233819 | INDv_Gilliam | PV470999 | Karp-like | INDv-Gilliam/Karp-like |

| 5. | PV176874 | INDv_Gilliam | PV233811 | Karp-like | INDv-Gilliam/Karp-like |

| 6. | PV233823 | INDv_Gilliam | PV471000 | Karp-like | INDv-Gilliam/Karp-like |

| 7. | PV233824 | INDv_Gilliam | PV471001 | Karp-like | INDv-Gilliam/Karp-like |

| 8. | PV176858 | INDv_Gilliam | PV233797 | Ot-TJTN | INDv_Gilliam/ Ot-TJTN |

| 9. | PV176859 | INDv_Gilliam | PV233798 | Ot-TJTN | INDv_Gilliam/ Ot-TJTN |

| 10. | PV176866 | INDv_Gilliam | PV233804 | Ot-TJTN | INDv_Gilliam/ Ot-TJTN |

| 11. | PV176876 | INDv_Gilliam | PV233813 | Gilliam-type | INDv_Gilliam /Gilliam |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).