Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Skin and Wound Healing Process

2.1. The Skin Structure

2.2. The Wound Healing Process and Type of Skin Wounds

2.3. The Role of Collgen in Skin Wound Healing

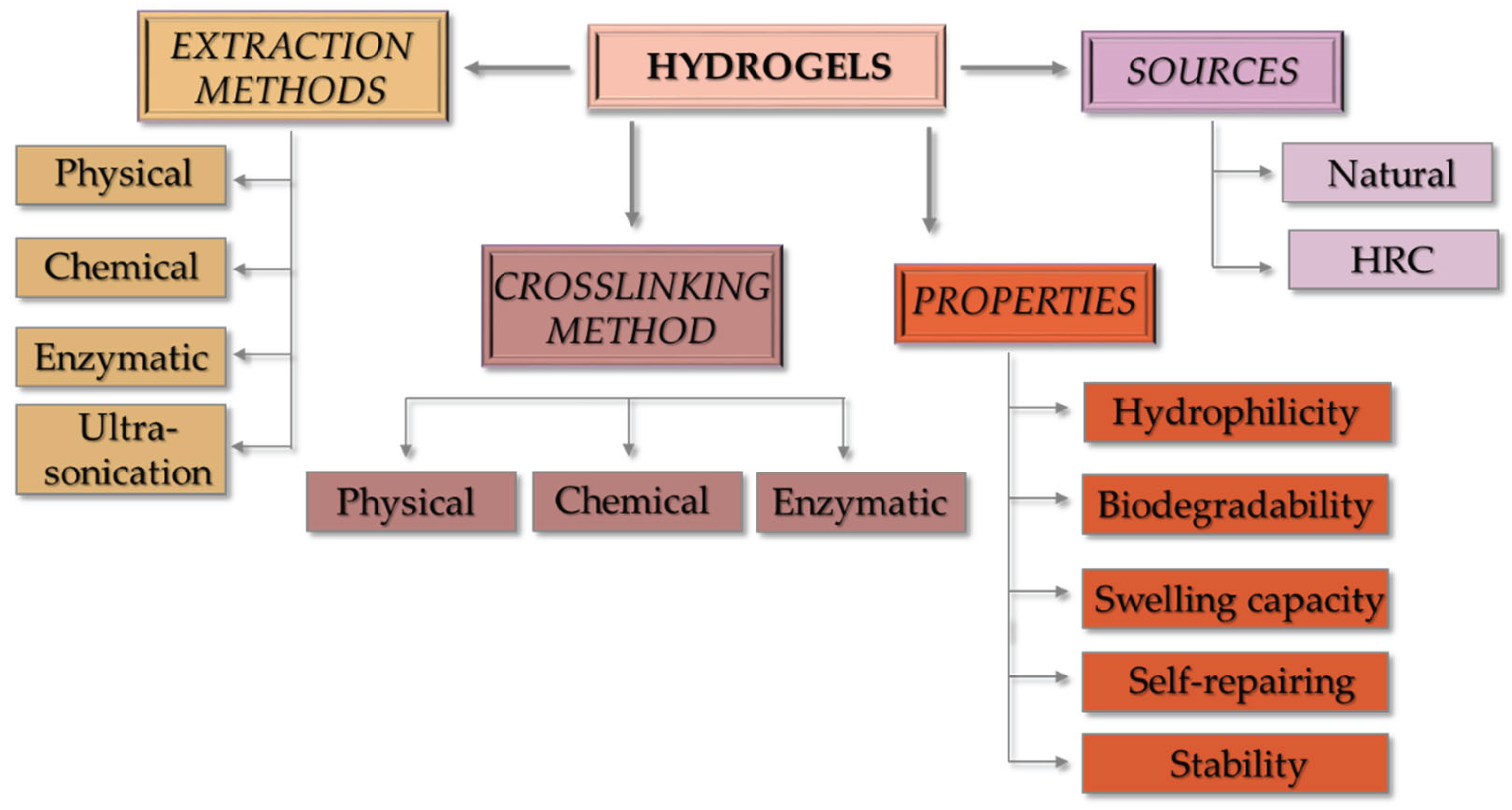

3. Collagen Structure, Sources and Extraction Methods

3.1. Collagen Structure

3.2. Collagen Sources and Extraction Methods

| Technique | Classification | Solvent | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| physical | dioxide acidified water high pressure carbon |

acidified water carbon dioxide |

[52] |

| extrusion-hydro-extraction | distilled water double distilled water |

[53] | |

| chemical | alkaline/acid solubilisation extraction | sodium hydroxide acetic/citric/lactic acid |

[54,55,56] |

| salt solubilisation extraction | sodium chloride | [57] | |

| enzymatic | porcine pepsin coupled with acetic acid | [58] | |

| others | Ultra-sonication assisted extraction |

ultrasonication coupled with acetic acid ultrasonication coupled with pepsin |

[59,60] |

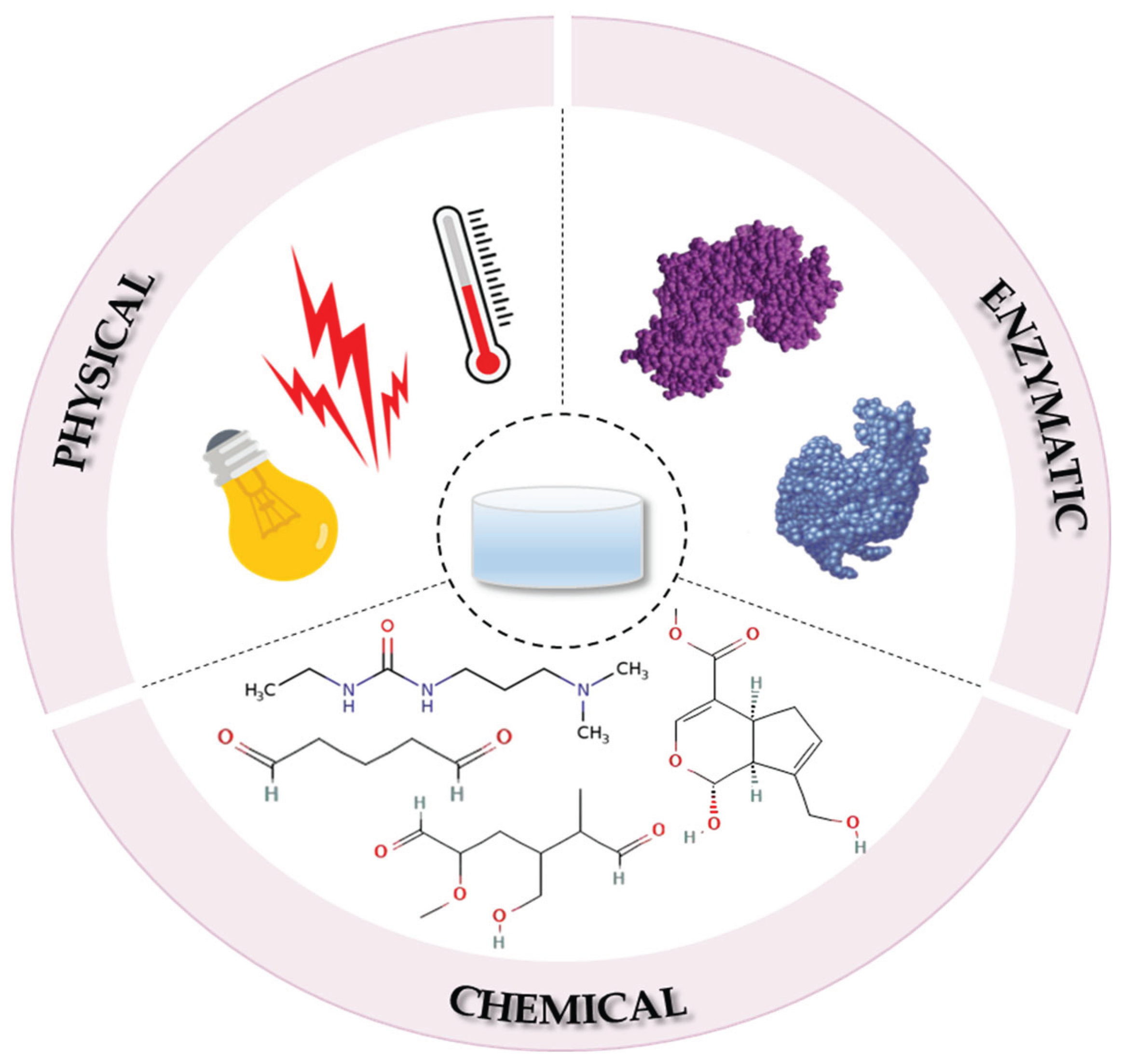

4. Fabrication Methods of Collagen-Based Hydrogels

4.1. The Physical Crosslinking Process

4.1.1. UV Radiation

4.1.2. Temperature

4.2. The Chemical Crosslinking Process

4.2.1. Glutaraldehyde

4.2.2. Dialdehyde Starch

4.2.3. Carbodiimides

4.2.4. Genipin

4.2.5. Other Reagents

4.3. The Enzymatic Crosslinking Process

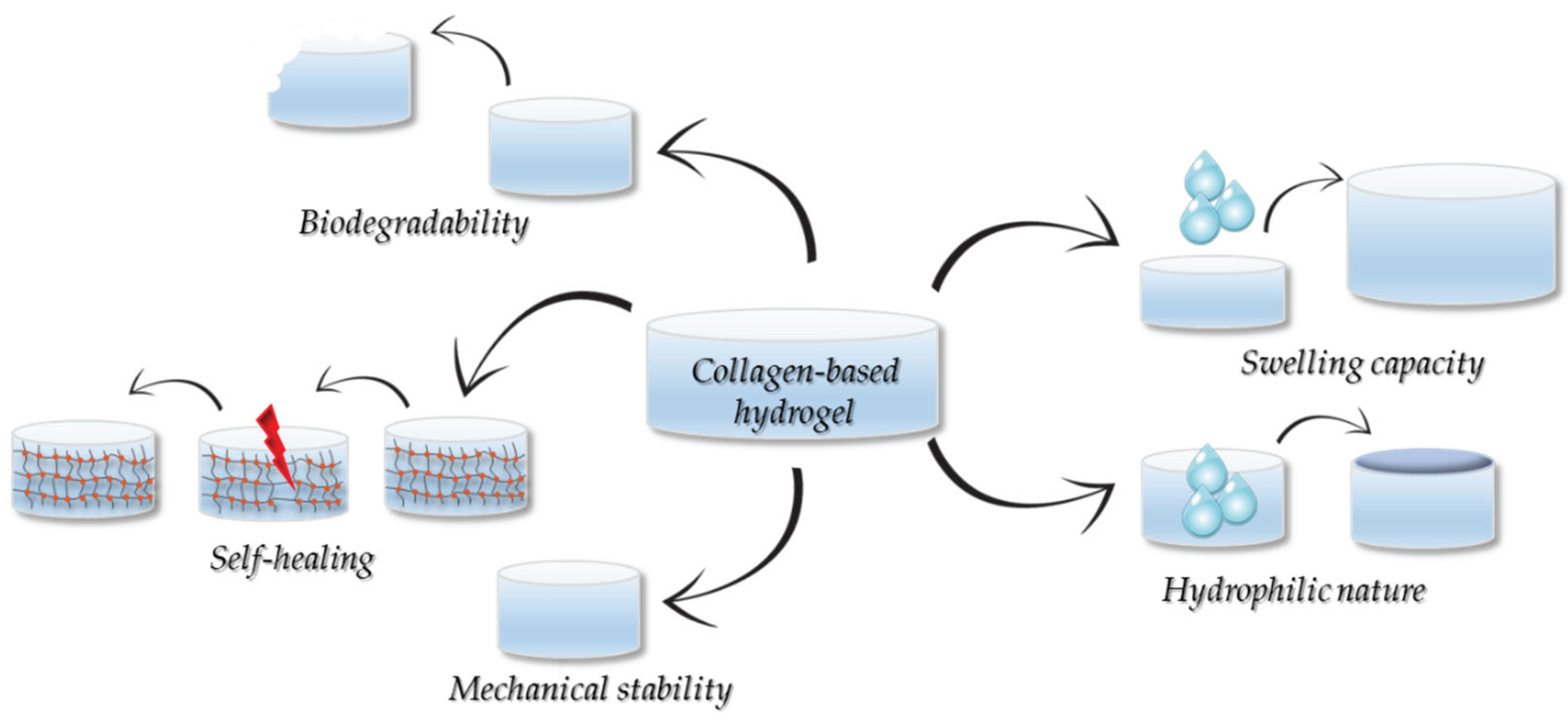

5. Properties of the Collagen-Based Hydrogels

5.1. Hydrohpilicity and Moisturization

5.2. Mechanical Properties

5.3. Degradability

5.4. Swelling Properties

5.5. Self-Healing

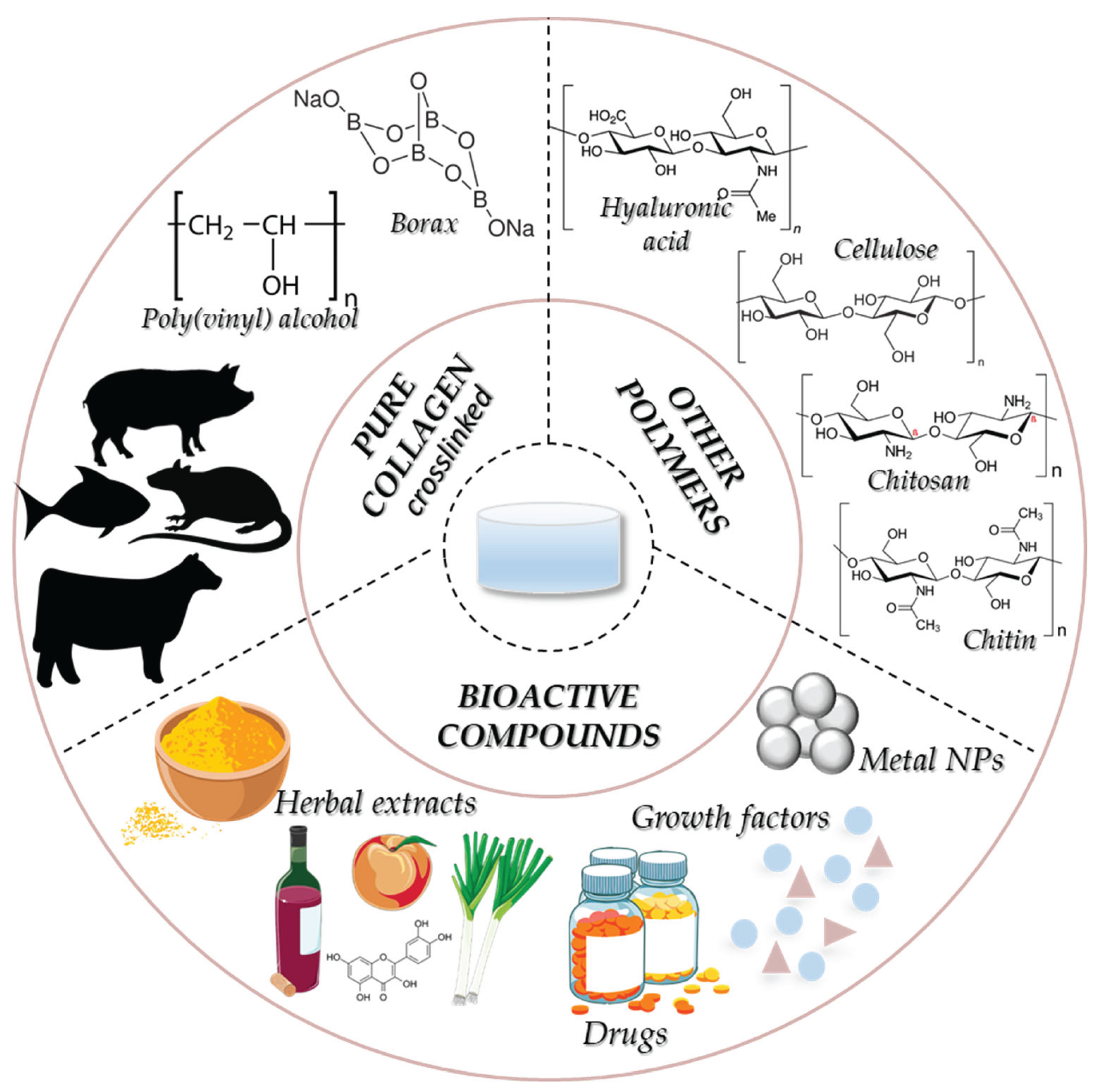

6. Collagen Hydrogel for Skin Wound Healing

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HRC | Human Recombinant Collagen |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinases |

| Gly | Glycine |

| Pro | Proline |

| Pro-HO | Hydroxyproline |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| DHT | Dehydrothermal method |

| OKGM | Oxidation modified konjac glucomannan |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| DFUs | Diabetic foot ulcers |

| PrUs | Pressure ulcers |

| VLUs | Venous leg ulcers |

| PSC | Pepsine-soluble collagen |

| Col-ADH | Collagen peptide |

| ODex | Oxidezed dextran |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| OSA | oxidized sodium |

| ZnO NPs | Zinc oxide nanoparticles |

| CuO NPs | Copper oxide nanoparticles |

| TGF-1β | Transforming growth factor 1β |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| DDSA | Dodecenylsuccinic anhydride |

| HA | Hyaluronic acid |

| SDF-1α | Stromal derived factor 1α |

| CMC | Carboxymethylcellulose |

| PEG | Polyethyleneglycole |

| PEO | Polyethylene oxide |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

References

- Liu, H.; Xing, F.; Yu, P.; Zhe, M.; Duan, X.; Liu, M.; Xiang, Z.; Ritz, U. A review of biomacromolecue-based 3D bioprinting strategies for structure-function integrated repair of skin tissues. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 268, 131623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioce, A.; Cavani, A.; Cattani, C.; Scopelliti, F. Role of the Skin Immune System in Wound Healing. Cells 2024, 13, 624; Antibacterial Conductive Collagen-Based Hydrogels for Accelerated Full-Thickness Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 22817–22829. [Google Scholar]

- Olteanu, G.; Neacsu, S.M.; Joita, F.A.; Musuc, A.M.; Lupu, E.C.; Ionita-Mindrican, C.B.; Lupuliasa, D.; Mititelu, M. Advancements in Regenerative Hydrogels in Skin Wound Treatment: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vig, K.; Chaudhari, A.; Tripathi, S.; Dixit, S.; Sahu, R.; Pillai, S. Dennis, V.A.; Singh, S.R. Advances in Skin Regeneration Using Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Hong, Y.; Fu, X.; Sun, X. Advances and applications of biomimetic biomaterials for endogenous skin regeneration. Bioactive Materials 2024, 39, 492–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, E.; Liu, P.Y.; Schultz, S.G.; Martins-Green, M.M.; Tanaka, R.; Weir, D.; Gould, L.J.; Armostrong, D.G.; Gibbons, G.W.; Wolcott, R.; Olutoye, O.O.; Kirsner, R.S.; Gurtner, G.C. Chronic wounds: Treatment consensus. Wound Repair Regener. 2022, 30, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, A.; Bratu, A.G.; Nicukescu, A.G.; Grumezescu, A.M. Collagen-Based Wound Dressings: Innovations, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Gels 2025, 11, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jin, M.; Lin, X.; Zhuang, Z.; Guo, K.; Zhang, T.; Tan, W. Application of Collagen-Based Hydrogel in Skin Wound Healing. Gels 2023, 9, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Li, D.; Dai, K.; Wang, Y.; Song, P.; Li, H.; Tang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Recent progress of collagen, chitosan, alginate and other hydrogels in skin repair and wound dressing applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 208, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.E.; Anseth, K.S. Spatiotemporal hydrogel biomaterials for regenerative medicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 6532–6552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Zhu, C.; Fan. D. Optimization of Human-like Collagen Composite Polysaccharide Hydrogel Dressing Preparation Using Response Surface for Burn Repair. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 293, 116249.

- Lin. X.; Yang, X.; Li, P.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Mu, C.; Li, D.; Ge, L. Antibacterial Conductive Collagen-Based Hydrogels for Accelerated Full-Thickness Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 22817–22829. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Meng, Q.; Zhong, S.; Gao, Y.; Cui, X. Recent advances in polysaccharide-based self-healing hydrogels for biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, G.; Shalumon, K.T.; Chen, J.-P. Natural Polymers Based Hydrogels for Cell Culture Applications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 2734–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.; Wang, L.; Song, C.; Yao, L.; Xiao, J. Recent progresses of collagen dressings for chronic skin wound healing. Collagen and Leather 2023, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.Q.; Shahriar, S.M.S.; Yan, Z.; Xie, J. Recent Advances in functional Wound Dressings. Adv. Wound Care 2023, 12, 399–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheokand, B.; Vats, M.; Kumar, A.; Srivasta, C.M.; Bahadur, I.; Pathak, S. Natural polymers used in the dressing materials for wound healing: Past, present and future. Journal of Polymer Science 2023, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lin, X.; Cao, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y. Developing natural polymers for skin wound healing. Bioactive Materials 2024, 33, 355-376; Aberbigbe, B.A. Hybrid-Based Wound Dressings: A Combination of Synthetic and Biopolymers. Polymers 2022, 14, 3806. [Google Scholar]

- Sorushanova, A.; Delgado, L.M.; Wu, Z.; Shologu, N.; Kshirsagar, A.; Raghunath, R.; Mullen, A.M.; Bayon, Y.; Pandit, A.; Raghunath, M.; et al. The Collagen Suprafamily: From Biosynthesis to Advanced Biomaterial Development. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1801651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taupin, P.; Gandhi, A.; Saini, S. Integra® Dermal Regeneration Template: From Design to Clinical Use. Cureus 2023, 15, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, M.; Shafiee, M.; Afshari, F.; Mohammadi, H.; Ghasemi, Y. Collagen-Based Medical Devices for Regenerative Medicine and Tissue Engineering. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 169, 5563–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geanaliu-Nicole, R.E.; Andronescu, E. Blended Natural Support Materials-Collagen Based Hydrogels Used in Biomedicine. Materials 2020, 13, 5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.S., The skin. In Techniques in Small Animal Wound Management, 1st edition; Editor Buote, N.J., Ed. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: Publisher: Hoboken, New Jersey, United States, 2024, pp. 1–36.

- Balavigneswaran, C.K.; Selvaraj, S.; Vasudha, T.K.; Iniyan, S.; Muthuvijayan, V. Tissue engineered skin substitues: A comprehensive review of basic design, fabrication using 3D printing, recent advances and challenges. Biomater. Adv. 2023, 153, 213570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhun, R.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Shi, G.; Cai, X.; Dou, R.; Tang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J. The potential of collagen-based materials for wound management. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 41, 102295. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, H.N.; Hardman, M.J. Wound Healing: Cellular Mechanisms and Pathological Outcomes. Adv. Surg. Med. Spec. 2023, 10, 341–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Monica, F.; Campora, S.; Ghersi, G. Collagen-Based Scaffolds for Chronic Skin Wound Treatment. Gels 2024, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Shi, G.; Cai, X.; Dou, R.; Tang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J. The potential of collagen-based materials for wound management. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 41, 102295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Kirsner, R. ; Pathophysiology of acute wound healing. Clin. Dermatol. 2007, 25, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonida, M.D.; Kumar, I. Wound Healing and Skin Regeneration. In Bionanomaterials for Skin Regeneration; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Han, G.; Ceilley, R. Chronic wound healing: a review of current management and treatments. Adv. Ther. 2017, 34, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qi, F.; Luo, H.; Xu, G.; Wang, D. Inflammatory Microenvironment of Skin Wound. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.H.; Huang, B.S.; Horng, H.C.; Yeh, C.C.; Chen, Y.J. Wound healing. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2018, 81, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Nunan, R. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Repair in Acute and Chronic Wound Healing. Br. J. Dermatol. 2015, 173, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, L.M.; Phillips, T.J. Wound healing and treating wounds: Differential diagnosis and evaluation of chronic wounds. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2016, 74, 589–605. [Google Scholar]

- Manon-Jensen, T.; Kjeld, N.G.; Karsdal, M.A. Collagen-mediated hemostasis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2016, 14, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisling, A.; Lust, R.M.; Katwa, L.C. What is the role of peptide fragments of collagen I and IV in health and disease? Life Sci. 2019, 228, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wosicka-Frackowiak, H.; Poniedzialek, K.; Wozny, S.; Kuprianowicz, M.; Nyga, M.; Jadach, B.; Milanowski, B. Collagen and Its Derivatives Serving Biomedical Purposes: A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Raines, R.T. Collagen-Based Biomaterials for Wound Healing. Biopolymers 2014, 101, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouw, J.K.; Ou, G.; Weaver, V.M. Extracellular matrix assembly: A multiscale deconstruction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.K.; Hahn, R.A. Collagens. Cell Tissue Res. 2010, 339, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison-Kotler, E.; Marshall, W. S.; Garcia-Gareta, E. Sources of collagen for biomaterial in skin wound healing. Bioengineering (Basel) 2019, 6, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvipriya, K.S.; Kumar, K.; Bhat, A.; Kumar, B.D.; John, A.; Lakshmanan, P. Collagen: Animal Sources and Biomedical Application. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 5, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefe, J.; Wauk, L.; Chu, S.; & DeLustro, F. Clinical use of injectable bovine collagen: A decade of experience. Clinical Materials 1992, 9, 155–162.

- Charriere, G; Bejot, M.; Schnitzler, L.; Ville, G.; Hartmann, D. J. Reactions to a bovine collagen implant. Clinical and immunologic study in 705 patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 1989, 21, 1203–1208.

- Wang, H. A Review of the Effects of Collagen Treatment in Clinical Studies. Polymers 2021, 13, 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Yue, O.; Bai, Z.; Cui, B.; Jiang, H.; Liu, X. A Review of Recent Progress on Collagen-Based Biomaterials. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2023, 12, 2202042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T. H.; Moreira-Silva, J.; Marques, A. L.; Domingues, A.; Bayon, Y.; Reis, R. L. Marine origin collagens and its potential applications. Marine Drugs 2014, 12, 5881–5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felician, F.F.; Xia, C.; Qi,W.; Xu, H. Collagen from Marine Biological Sources and Medical Applications. Chem. Biodivers. 2018, 15, e1700557.

- Wang, M.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Du, Z.; Qin, S. Preparation and characterization of novel poly (vinyl alcohol)/collagen double-network hydrogels. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, C.; Liu, N.; Liang, F.; Zhao, X.; Long, J.; Yuan, F.; Yun, S.; Sun, Y.; Xi, Y. Molecular assembly of recombinant chicken type II collagen in the yeast Pichia pastoris. Sci. China Life Sci. 2018, 61, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, A.A.; Aroso, I.M.; Silva, T.H.; Mano, J.F.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Reis, R.L. Water and carbon dioxide, green solvents for the extraction of collagen/gelatin from marine sponges. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, C.; Li, X.; Xin, Q.; Han, W.; Shi, C.; Guo, R.; Shi, W.; Qiao, R.; Wang, X.; Zhong, J. Effect of extraction methods on the preparation of electrospun/electrosprayed microstructures of tilapia skin collagen. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2019, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Xiaoliang, Z.Y. Characterization of rabbit skin collagen and modeling of critical gelation conditions. Food Sci. 2002, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniasih, R.A.; Swastawati, F.; Riyadi, P.H.; Rianingsih, L. The influence of extraction period on the characteristics of acid soluble collagen from sea catfish (Arius thalassinus) swim bladder. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Kuo, J.M.; Wu, S.J.; Tsai, H.T. Isolation and characterization of fish scale collagen from tilapia (Oreochromis sp.) by a novel extrusion-hydroextraction process. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Q.; Wang, L.; Sun, W.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Ma, H. Isolation and characterization of collagen from the cartilage of Amur sturgeon (Acipenser schrenckii). Process Biochem. 2014, 49, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboob, S. Isolation and characterization of collagen from fish waste material skin, scales and fins of Catla catla and Cirrhinus mrigala. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 4296–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Kim, Y.K.; Park, H.J.; Lee, N.H. Application of ultrasonic treatment to extraction of collagen from the skins of sea bass Lateolabrax japonicas. Fish. Sci. 2013, 79, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Mu, C.; Cai, S.; Lin, W. Ultrasonic irradiation in the enzymatic extraction of collagen. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2009, 16, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, X.; Dong, S.; Guo, L.; Zhang, S.; Yang, X.; Liu, C.; Jiang, X. Kan, M.; Wu, S.; Zhang, J.; Xu, C. Advances in preparation and application of antibacterial hydrogels. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, D.; Desai, N.; Salave, S.; Karunakaran. B.; Giri, J.; Benival, D.; Gorantla, S.; Kommieni, N. Collagen-Based Hydrogels for the Eye: A Comprehensive Review. Gels 2023, 9, 643.

- Khattak, S.; Ullah, I.; Xie, H.; Tao, X.D.; Xu, H.T.; Shen, J. Self-healing hydrogels as injectable implants: advances in translational wound healing. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 509, 215790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, A.S.; Premanand, R.; Ragupathi, I.; Bhaviripudi, V.R.; Aepuru, R.; Kannan, K.; Shanmugaraj, K. Comprenhensive Review of Hydrol Sythesis, Characterization and Emerging Applications. J. Comps. Sci. 2024, 8, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bax, D.V.; Davidenko, N.; Hamaia, S.W.; Farndale, R.W.; Best, S.M.; Cameron, R.E. Impact of UV- and carbodiimide-based crosslinking on the integrin-binding properties of collagen-based materials. Acta Biomater. 2019, 100, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamiak, K.; Sionkowska, A. Current methods of collagen cross-linking: Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sionkowska, A.; Lewandowska, K.; Adamiak, K. The Influence of UV Light on Rheological Properties of Collagen Extracted from Silver Carp Skin. Materials 2020, 13, 4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Liu, Y.; Tang, L.; Xiao, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S. Preparation of Recombinant Human Collagen III Protein Hydrogels with Sustained Release of Extracellular Vesicles for Skin Wound Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, R.;Wang, C.; Guo, Y.; Sun,W.; Ouyang, L. Recombinant Human Collagen-Based Bioinks for the 3D Bioprinting of Full-thickness Human Skin Equivalent. Int. J. Bioprint. 2022, 8, 611.

- Kazobolis, V.; Labiris, G.; Gkika, M.; Sideroudi, H.; Kalaghianni, E.; Papadopoulou, D.; Taufexis. UV-A collagen cross-linking treatment of bullous keratopathy combined with corneal ulcer. Cornea 2010, 29, 235–238. [CrossRef]

- Richoz, O.; Hammer, A.; Tabibian, D.; Gatzioufas, Z.; Hafezi, F. The biochemical effect of corneal collagen crosslinking (CXL) with riboflavin and UV-A is oxygen dependent. Transl. Vis. Sci. Techn. 2013, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, L.; Xu, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Shinoda, M.; Kishimoto, M.; Tanaka, T.; Yamane, H. Effect of the Application of a Dehydrothermal Treatment on the Structure and the Mechanical Properties of Collagen Film. Materials 2020, 13, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzma, J.; Suchy, T.; Horny, L.; Supova, M.; Sucharda, Z. Comparative Study of the Dehydrothermal Crosslinking of Electrospun Collagen Nanaofibers: The Effects of Vacuum Conditions and Subsequent Chemical Crosslinking. Polymers 2024, 16, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, L.; Shan, T.; Ma, Y.; Tay, F.R.; Niu, L. Novel Biomedical Applications of Crosslinked Collagen. Trend in Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 464–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.P.; Shanmugasundaram, S.; Masih, P.; Pandya, D.; Amara, S.; Collins, G.; Arinzeh, T.L. An investigation of common crosslinking agents on the stability of Electrospun collagen scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2014, 103, 726–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Z.; Wu, K.; Liu, W.; Shen, L.; Li, G. Two-dimensional infrared spectroscopic study on the thermally induced structural changes of glutaraldehyde-crosslinked collagen. Spectrochim.Acta A 2015, 140, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casali, D.M.; Yost, M.J.; Matthews, M.A. Eliminating glutaraldehyde from crosslinked collagen films using critical CO2. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2018, 106, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Liu, W.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, Y. Preparation and Characterization of Dialdehyde Starch by One-Step Acid Hydrolysis and Oxidation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 1257–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabskaielinska, S. Cross-linking Agents in Three-component Materials Dedicated to Biomedical Applications: A Review. Polymers 2024, 6, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yuan, L.; Liu, Q.; Li, D.; Mu, C.; Zhao, L.; Li, X.; Ge, L. Crosslinking effect of dialdehyde cholesterol modified starch nanoparticles on collagen hydrogel. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 285, 119237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapach, L.A.; Vanderburgh, J.A.; Miller, J.P.; Reinhart-King, C.A. Manipulation of in Vitro Collagen Matrix Architecture for Scaffolds of Improved Physiological Relevance. Phys. Biol. 2015, 12, 61002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, F.; Guo, S.; Yang, J. Preparation of aminated fish scale collagen and oxidized sodium alginate hybrid hydrogel for enhanced full-thickness wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska-Łańcucka, J.; Gilarska, A.; Buła, A.; Horak, W.; Łatkiewicz, A.; Nowakowska, M. Genipin crosslinked bioactive collagen/chitosan/hyaluronic acid injectable hydrogels structurally amended via covalent attachment of surface-modified silica particles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 136, 1196–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacAya, D.; Ng, K.K.; Spector, M. Injectable Collagen-Genipin Gel for the Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury: In Vitro Studies. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 4788–4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacmarek-Szczepanska, B.; Wekwejt, M.; Palubicka, A.; Michno, A.; Zasada, L.; Alsharabasy, A.M. Cold plasma treatment of tannic acid as a green technology for the fabrication of advanced cross-linkers for bioactive collagen/gelatin hydrogels. Macromolecules 2024, 258, 128870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Wu, J.; Cao, J.; Xu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang. M. Feasibility of caffeic acid as crosslinking agent in modifying accelular extracellular matrices. Res. Comm. 2023, 677, 82–189.

- Alam, M.; Ahmed, S.; Elasbali, A.M.; Adnan, M.; Alam, S.; Hassan, M.I.; Pasupuleti, V.R. Therapeutic Implications of Caffeic Acid in Cancer and Neurological Diseases. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 860508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, X.; Hao, J. Enzyme-regulated healable polymeric hydrogels. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 1507–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frayssinet, A.; Petta, D.; Illoul, C.; Haye, B.; Markitantova, A.; Eglin, D.; Mosser, G.; D’Este, M.; Hélary, C. Extracellular matrix-mimetic composite hydrogels of cross-linked hyaluronan and fibrillar collagen with tunable properties and ultrastructure. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 236, 116042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Fan, D. Double crosslinked HLC-CCS hydrogel tissue engineering scaffold for skin wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, J.; Liu, J.; Mu, Y.; Lv, S.; Tong, J.; Liu, L.; He, T.; Wang, J.; Wei, D. Recent advances in collagen-based hydrogels: Materials, preparation and applications. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2025, 207, 106136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrigiaddidis, S.O.; Rey, J.M.; Dobre, O.; Gonzales-Gracia, C.; Dlby, M.J.; Salmeron-Sanchez, M. A tough act to follow: collgen hydrogel modifications to improve mechanical and growth factor loading capabilities. Mater. Today Bio. 2021, 10, 100098. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Dai, W.; Gao, Y.; Dong, L.; Jia, H.; Li, S.; Guo, L.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X. The synergistic regulation of chondrogenesis by collagen-based hydrogels and cell co-culture. Acta Biomater. 2022, 154, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, P.; Ruan, D.; Huang, M.; Tian, M.; Zhu, K.; Gan, Z.; Xiao, Z. Harnessing the potential oh hydrogels for advanced therapeutic applications: current achievements and future directions. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.C.; Chang, C.C.; Chan, H.P.; Chung, T.W.; Shu, C.W.; Chuang, K.P.; Duh, T.H.; Yang, M.H.; Tyan, Y.C. Hydrogels: Properties and Applications in Biomedicine. Molecules 2022, 27, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.I.E.; Mollari, K.G.; Komvopoulos, K. Design Challenges in Polymeric Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 617141. [Google Scholar]

- Rahvar, P.T.; Abdekhodaie, M.J.; Jooybar, E.; Gantenbein, B. An enzymatically crosslinked collagen type II/hyaluronic acid hybrid hydrogel: a biomimetic cell delivery system for cartilage tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 134614. [Google Scholar]

- Dinescu, S.; Albu Kaya, M.; Chiroiu, L.; Ignat, S.; Kaya, D.A.; Costache, M. Collagen-Based Hydrogels and Their Applications for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. In: Mondal, M (eds) Cellulose-Based Superabsorbent Hydrogels. Polymers and Polymeric Compoistes: A Reference Series, Springer, Cham., 2019.

- Caliari, S.R.; Burdick, J.A. A practical guide to hydrogels for cell culture. Nature Methods 2016, 13, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L; Sun, L.; Huang, H.; Zhu, W.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Neisiany, R.E.; Gu, S.; You, Z. Mechanically robust and room temperature self-healing Ionogel based on ionic liquid inhibited reversible reaction of disulfide bonds. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2207527. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.; Hwang, S.Y.; Oh, D.X.; Park, J. Recent progress in self-healing polymers and hydrogels based on reversible dynamic B-O bonds: boronic/boronate esters, borax, and benzoxaborole. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 14630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Li, H.; Lu, J.; Wei, Q. Collagen-based injectable and-self healing hydrogel with multifunction for regenerative repairmen of infected wounds. Regen. Biomater. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, S.; Mooney, DJ. Tissue-engineered wound dressings for diabetic foot ulcers. Springer 2018, 247–56. [Google Scholar]

- Khampieng, T.; Wongkittithavorn, S.; Chaiarwut, S.; Ekabutr, P.; Pavasant, P.; Supaphol, P. Silver nanoparticles-based hydrogel: characterization of material parameters for pressure ulcer dressing applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2018, 44, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrowicz, H.; Owczarczyk-Saczonek, A.; Placek, W. Venous leg ulcers: advanced therapies and new technologies. Biomedicines. 2021, 9, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizanova, O.; Penesova, A.; Hokynkova, A.; Pokorna, A.; Samadian, A.; Babula, P. Chronic venous insufficiency and venous leg ulcers: Aetiology, on the pathophysiology-based treatment. Int. Wound J. 2024, 21, e14405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyko, T.V.; Longaker, M.T.; Yang, G.P. Review of the current management of pressure ulcers. Adv Wound Care. 201, 7, 57–67.

- Ge, B.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, N.; Qin, S. Comprehensive Assessment of Nile Tilapia Skin (Oreochromis niloticus) Collagen Hydrogels for Wound Dressings. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhai, Y.N.; Xu, J.P.; Zhu, X.Y.; Yang, H.R.; Che, H.J.; Liu, C.K.; Qu, J.B. An injectable collagen peptide-based hydrogel with desirable antibacterial, self-healing and wound healing properties based on multiple-dynamic crosslinking. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, P.F.; Zheng, B.D.; Xu, Y.L.; Li, B.Z.; Liu, Z.Y.; Huang, Y.Y.; Ye, J.; Xiao, M.T. Multifunctional fish-skin collagen-based hydrogel sealant with dual-dynamic-bond cross-linked for rapid hemostasis and accelerated wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, F.; Hu, X.; Shi, X.; Li, T.; Yang, H. Exploration on the multifunctional hydrogel dressings based on collagen and oxidized sodium: A novel approach for dynamic wound treatment and monitoring. J. Mol. Liquids 2024, 409, 125478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo-Morales, H.; Cobos-Puc, L.E.; Lopez-Badillo, C.M.; Oyervides-Munoz, E.; Ramirez-Garcia., G.; Claudio-Rizo, J.A. Collagen-polyurethane-dextran hydrogels enhace wound healing by inhibiting inflammation and promoting collagen fibrillogenesis. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2024, 112, 1760–1777. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yan, Z.; Ji, S.; Xiao, S.; Gao, J. Metal nanoparticles hybrid hydrogels: the state-of-the-art of combining hard and soft materials to promote wound healing. Theranostics 2024, 14, 1534–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Qi, X.; Shi, G.; Zhang, M.; Haick, H. Wound Dressing: From Nanomaterials to Diagnostic Dressings and Healing Evaluations. ACS Nano. 2022, 16, 1708–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzulkharnien, N.S.F.; Rohani, R. A Review on Current Designation of Metallic Nanocomposite Hydrogel in Biomedical Applications. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantari, K.; Mostafavi, E.; Afifi, A.M. Wound dressings functionalized with silver nanoparticles: promises and pitfalls. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 2268–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Liu, W.; Long, L.;Wang, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang,W.; He, S.;Wang, J.; Yang, L.; Lu, L.; et al. Microenvironment-responsive multifunctional hydrogels with spatiotemporal sequential release of tailored recombinant human collagen type III for the rapid repair of infected chronic diabetic wounds. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 9684–9699.

- Zhao, F.; Liu, Y.; Song, T.; Zhang, B.; Li, D.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X. A chitosan-based multifunctional hydrogel containing in situ rapidly bioreduced silver nanoparticles for accelerating infected wound healing. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 2135–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, C.; Fan, Y.; Liu, G.; Li, W.; Ma, J.; Xiao, J. One-step fabrication of an injectable antibacterial collagen hydrogel with in situ synthesized silver nanoparticles for accelerated diabetic wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 480, 148288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birca, A.C.; Minculescu, M.A.; Niculescu, A.G.; Hudita, A.; Holban, A.M.; Alberts, A.; Grumezescu, A.M. Nanoparticles-Enhanced Collagen Hydrogels for Chronic Wound Manegement. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comino-Sanz, I.M.; Lopez-Franco, M.D.; Castro, B.; Pancorbo-Hidalgo, P.L. The Role of Antioxidants on Wound Healing: A Review of the Current Evidence. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazarlu, O.; Iranshahi, M.; Kashani, H.R.K.; Reshadat, S.; Habtemariam, S.; Iranshahy, M.; Hasanpour, M. Perspective on the application of medicinal plants and natural products in wound healing: A mechanistic review. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 174, 105841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Fan, D.; Yuan, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhao, J.; Yang, J. An ultrasmall infinite coordination polymer nanomedicine-composited biomimetic hydrogel for programmed dressing-chemo-low level laser combination therapy of burn wounds. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 1306106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alven, S.; Nqoro, X.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Polymer-Based Materials Loaded with Curcumin for Wound Healing Applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Peng, W.; Lu, Q.; Ma, S.; Wang, J.; Ma, J.; Wei, X.; Li, M.; Wang, H. Collagen-based hydrogel derived from amniotic membrane loaded with quercetin accelerates wound healing by improving sterelogical parameters and reducing inflammation in a diabetic rat model. Tissue and Cell 2025, 93, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yao, J.; Han, C.; Yang, J.; Chaudhry, M.T.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.; Yin, Y. Quercetin, inflammation and immunity. Nutrients 2016, 8, 167; Aceituno-Medina, M.; Mendoza, S.; Rodrıguez, B.A.; Lagaron, J.M.; López-Rubio, A. Improved antioxidant capacity of quercetin and ferulic acid during in-vitro digestion through encapsulation within food-grade electrospun fibers. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 12, 332–341. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdogan, C.Y.; Kenar, H.; Uzuner, H.; Karadenizli, A. Atelocollagen-based hydrogel loaded with Crotinus coggygria extract for treatment of type 2 diabetic wounds. Biomed. Mater. 2025, 20, 025009. [Google Scholar]

- Olivetti, C.E.; Alvarez Echazú, M.I.; Perna, O.; Perez, C.J.; Mitarotonda, R.; De Marzi, M.; Desimone, M.F.; Alvarez, G.S. Dodecenylsuccinic anhydride modified collagen hydrogels loaded with simvastatin as skin wound dressings. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2019, 107, 1999–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, F.; Guo, S.; Yang, J. Preparation of aminated fish scale collagen and oxidized sodium alginate hybrid hydrogel for enhanced full-thickness wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, W.; Lin, C.; Tao, B.; Deng, Z.; Gao, P.; Yang, Y.; Cai, K. A pH-responsive hyaluronic acid hydrogel for regulating the inflammation and remodeling of the ECM in diabetic wounds. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 2875–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Su, D.; Wu, S.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J. Injectable, self-healing and pH responsive stem cell factor loaded collagen hydrogel as a dynamic bioadhesive dressing for diabetic wound repair. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 5887–5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, M.; Alissa, M.; Alghamadi, A. Collagen-based hydrogel encapsulated with SDF-1α microspheres accelerate diabetic wound healing in rats. Tissue and Cell 2025, 95, 102877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tai, Y.F.; Liu, X.S.; Liu, Y.F.; Dong, Y.S.; Liu, Y.J.; Yang, C.; Kong, D.L.; Qi, C.X.; Wang, S.F.; Midgley, A.C. Natural polymeric and peptide-loaded composite wound dressings for scar prevention. Appl. Mater Today 2021, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.X.; Zhao, W.Y.; Fang, Q.Q.; Wang, X.F.; Chen, C.Y.; Shi, B.H.; Zheng, B.; Wang, S.J.; Tan, W.Q.; Wu, L.H. Effects of chitosan-collagen dressings on wound healing in vitro and in vivo assays. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Fan, D. Double crosslinked HCL-CCS hydrogel tissue engineering scaffold for skin wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.H.; Yin, Z.; Guo, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhou, J.Y.; Wang, L.; Bai, J.Y.; Fan, Z. Facile and large-scale synthesis of PVA/Chitosan/Collagen hydrogel for wound healing. New J. Chem. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeter, M.; Negrescu, A.M.; Ion, C.; Scariosreanu, A.; Albu Kaya, M.; Micutz, M.; Dumitru, M.; Cimpean, A. Synthesis, Physicochemical Characteristics, and Biocompatibility of Multi-Component Collagen-Based Hydrogels Developed by E-Beam Irradiation. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Qian, C.; Zheng, X.; Qi, X.; Bi, J.; Wang, H.; Cao, J. Collagen/chitosan/genipin hydrogel loaded with phycocyanin nanoparticles and ND-336 for diabetic wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, H.S.; Saleh, S.; Omar, A.E.; Saleh, A.K.; Salama, A.; Tolba, E. Development of collagen-chitosan dressing gel functionalized with propolis-zinc oxide nanoarhitectonics to accelerate wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 261, 129665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindi, B.; Perioli, A.; Melo, P.; Mattu, C.; Ferreira, A.M. Bioinspired Collagen/Hyaluronic Acid/Fibrin-Based Hydrogels for Soft Tissue Engineering: Design, Synthesis, and In Vitro Characterization. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, K.J.; Kumar, S. Hyaluronic acid: incorporating the bio into the material, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 8, 3753–3765. [Google Scholar]

- Burla, F.; Tauber, J.; Dussi, S.; van der Gucht, J.; Koenderink, G.H. Stress management in composite biopolymer networks. Nat. Phys. 2018, 15, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Dong, L.; Guo, Z.; Liu, L.; Fan, Z.; Wei, C.; Mi, S.; Sun, W. Collagen-Hyaluronic Acid Composite Hydrogels with Applications for Chronic Diabetic Wound Repair. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 5376–5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tang, P.; Zheng, T.; Ran, R.; Li, G. An injectable, self-healing, and antioxidant collagen- and hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel mediated with gallic acid and dopamine for wound repair. Carbohydrate Polymers 2023, 320, 121231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Acute wounds | Chronic wounds |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial invasion | Minimal bacterial invasion | Bacterial colonization |

| Inflammatory activity | Reduced levels of inflammatory cytokines | High concentrations of inflammatory cytokines |

| Levels of ROS/proteases | Reduced levels of proteases and ROS | High levels of ROS and proteases |

| ECM functionality | Functional ECM | Degraded ECM |

| Cell activity | Proliferating cells | Senescent cells |

| Crosslinking process | Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Physical |

UV radiation temperature |

lack of crosslinker improved hydrogel degradation |

phototoxicity issues structural changes in COL due to high temperature |

| Chemical | glutaraldehyde dialdehyde starch |

good stability very effective |

the crosslinker cannot be removed completely high toxicity |

| carbodiimides | optimal biocompatibility high water solubility mild reaction conditions |

reduced crosslinking strength | |

| phenolic compounds |

high water retention eco-friendly optimal pore size |

risk of self-aggregation low hydrogel extensibility |

|

| genipin | lack of toxicity favourable biocompatibility |

slow crosslinking reaction high-costs |

|

| Enzymatic | glutamine transaminase, lysyl oxidase, horseradish peroxidase |

lack of crosslinkers easily controlled conditions |

biocompatibility concerns high-costs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).