1. Introduction

The organic or inorganic substances which show mesomorphism are known as Liquid Crystals (LCs). While studying the melting process in cholesterol derivatives systematically, double melting was observed by Friedrich Reinitzer in 1888, later further research on such substances by Otto Lehmann et al., coined them as Liquid Crystals. Since then, LCs have gained much attention due to their scientific and industrial applications. They possess unique characteristics such as anisotropy and optical birefringence of solids, isotropic properties of liquids etc. simultaneously [

1,

2,

3,

4]. By subjecting to heat [

5,

6,

7] or dilution [

4,

8,

9], the materials show the mesomorphism and are named as thermotropic and lyotropic LCs [

1,

10] respectively. The mesophases are neither crystalline nor liquid solely in nature but exhibit both the properties simultaneously. Thermotropic LCs are again classified into nematic and smectic [

1,

11] depending on the molecular arrangement and their interactions in inter and intra layers. In nematic phase, the LC molecules have long range orientational order while in the smectic phases possess partial positional order along with orientational order.

Liquid crystals (LCs) have gained significant attention due to their unique properties [

12,

13,

14] and diverse applications [

8,

9,

15,

16,

17,

18] and considered as an exciting topic of interest due to their suitability in various fields [

16,

19,

20] of research. The LCs have been exploited from flat panel displays to sensors to medical/biological fields. They could be tuned themselves in a unique way by application of heat, light, electric or magnetic fields [

21,

22,

23,

24].

Hydrogen bond (HB) interactions are considered [

25,

26,

27] as the fifth fundamental type of chemical interactions [

2] and are like tiny magnets between molecules. The interaction between a hydrogen atom and an electronegative atom such as oxygen or nitrogen or sulphur atom leads to the formation of HB. They have been exploited in recent years due to their powerful nature of self-assembly [

28]. Because of the presence of both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing nature, Pyridine derivatives are potential candidates [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33] for forming HBs with other molecules containing active Hydrogen atom. HB interactions generate supramolecular LCs [

30,

34,

35], which provide a flexible platform for the design of materials with specific characteristics. Preparation of supramolecular complexes [

25,

29,

36] through HB interactions using selective complementary functional groups is a fascinating approach and are exploring for diverse applications [

37]. One of the potential techniques to realize mesomorphism in non-mesogenic molecules is through HB interactions. The chemical moieties with proton donor and proton acceptor capabilities are desirable [

34] to form HB interactions and should have elongated length to show mesomorphism. It was reported that the mesomorphism is influenced by flexible alkyl chain length of the carboxylic acids through their electron donating ability [

35], while Pyridine derivatives behave as proton acceptors [

38,

39,

40]. HB interactions may induce or stabilize or quench or enhance the mesophase thermal spans viz., of Nematic (N), smectic-A (SmA), smectic-C (SmC) etc. depend on the substituents on proton donor or acceptor moieties. However, the parameters that dictate the evolution of mesomorphism are still mysterious. In our previous reports [

30,

32,

33,

34,

37,

41,

42], Pyridine containing Schiff’s base with mono halogen substituent / flexible chain were used to form the HB interactions with

nOBAs and observed that the smectic mesomorphism prevailed and nematic mesophase has been quenched. Interestingly, it was noticed that the non-mesogenic pyridine containing Schiff base and non-mesogenic halogen substituted benzoic acids showed smectic mesomorphism over large range of temperatures. The dihalogen substituted benzoic acids with the same pyridine derivatives showed the highest mesomorphism. However, the HB interactions between dihalogen substituted pyridine derivatives and benzoic acids are scarce in literature. In view of these observations, new pyridine containing Schiff’s base with dihalogen substituents viz., 3-chloro-4-fluoro-N-((pyridin-4-yl)methylene)benzenamine (4Py) are prepared and used as proton acceptors to form the HB interactions with 4

-n-alkyloxybenzoic acids (ethyl to dodecyl) proton donors. This study may provide valuable insights in the development of new mesomorphic materials formed through HB interactions and may paved the way for their technical applications.

2. Results

2.1. Synthesis

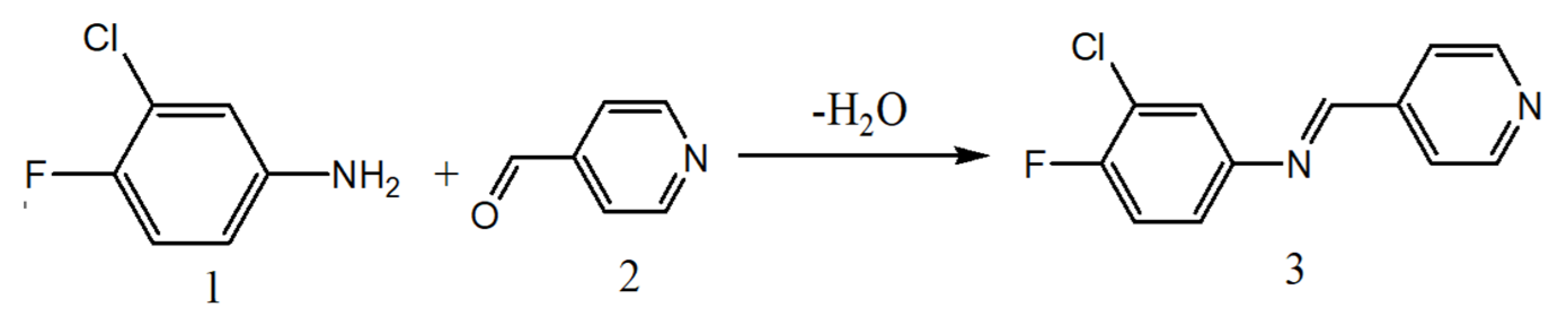

The proton acceptor viz., 3-chloro-4-fluoro-N-((pyridin-4-yl)methylene)benzenamine (4Py) is prepared by condensation reaction [

41,

43,

44] between 3-chloro-4-fluoro-aniline and 4-pyridinecarboxaldehyde as reported earlier. The ethanolic solutions of equimolar quantities (0.01M) of 3-chloro-4-fluoroaniline (

1) and 4-pyridinecarboxaldehyde (

2) are taken in a round bottom flask. About 2 drops of acetic acid are added and refluxed for an hour. The progress of the reaction is monitored by TLC. After completing the reaction, the contents are cooled, a white crystalline product (

3, 4Py), is obtained. The final product is purified by recrystallization three times with ethanol. The synthetic route for the preparation of 4Py is depicted in

Scheme 1.

The synthesized proton acceptor viz., 4Py and the proton donors viz., 4-

n-alkyloxybenzoic acids (

nOBA,

n is the no. of carbons in alkyl chain) are taken in 1:1 molar ratio and dissolved in a common solvent, tetrahydrofuran (THF). The mixture is refluxed for 2 h followed by cooling and distilling off the solvent, a binary mixture is formed, which on further characterization revealed the self-assembly of the two moieties through HB interactions. The general molecular structure of the HB complexes is given in

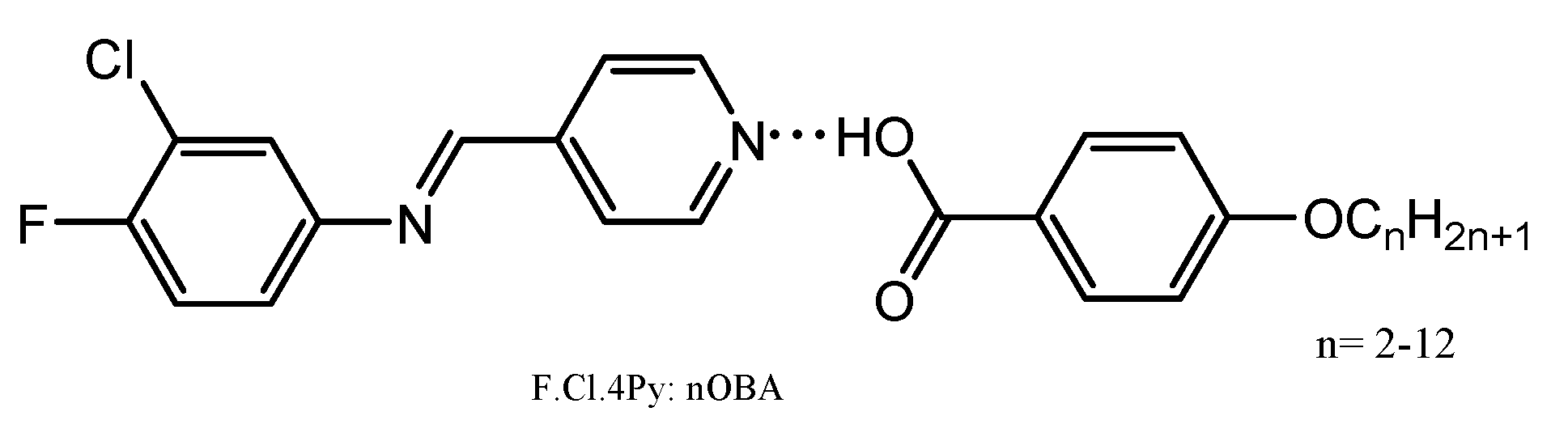

Figure 1.

2.2. Characterization by the Spectral Studies:

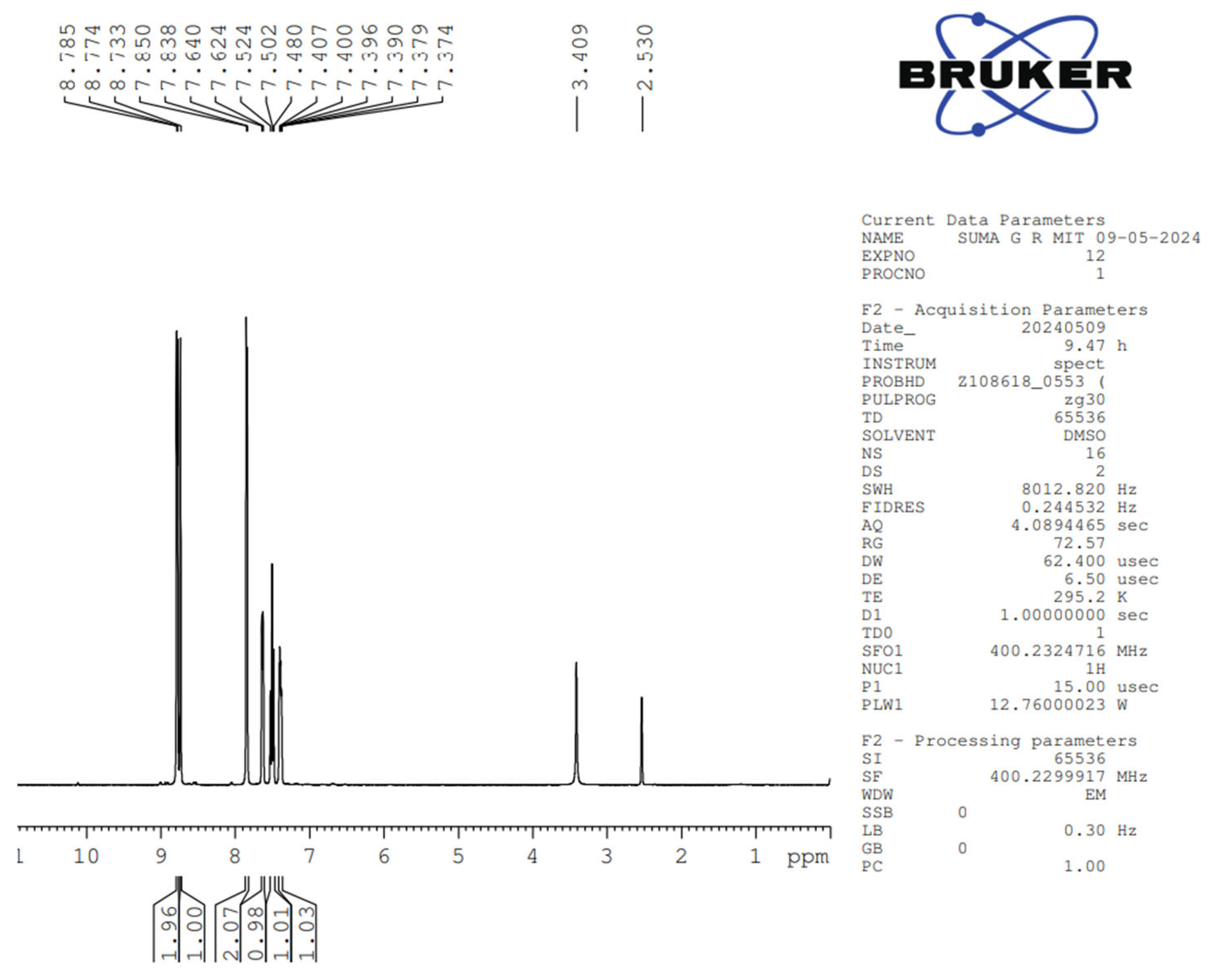

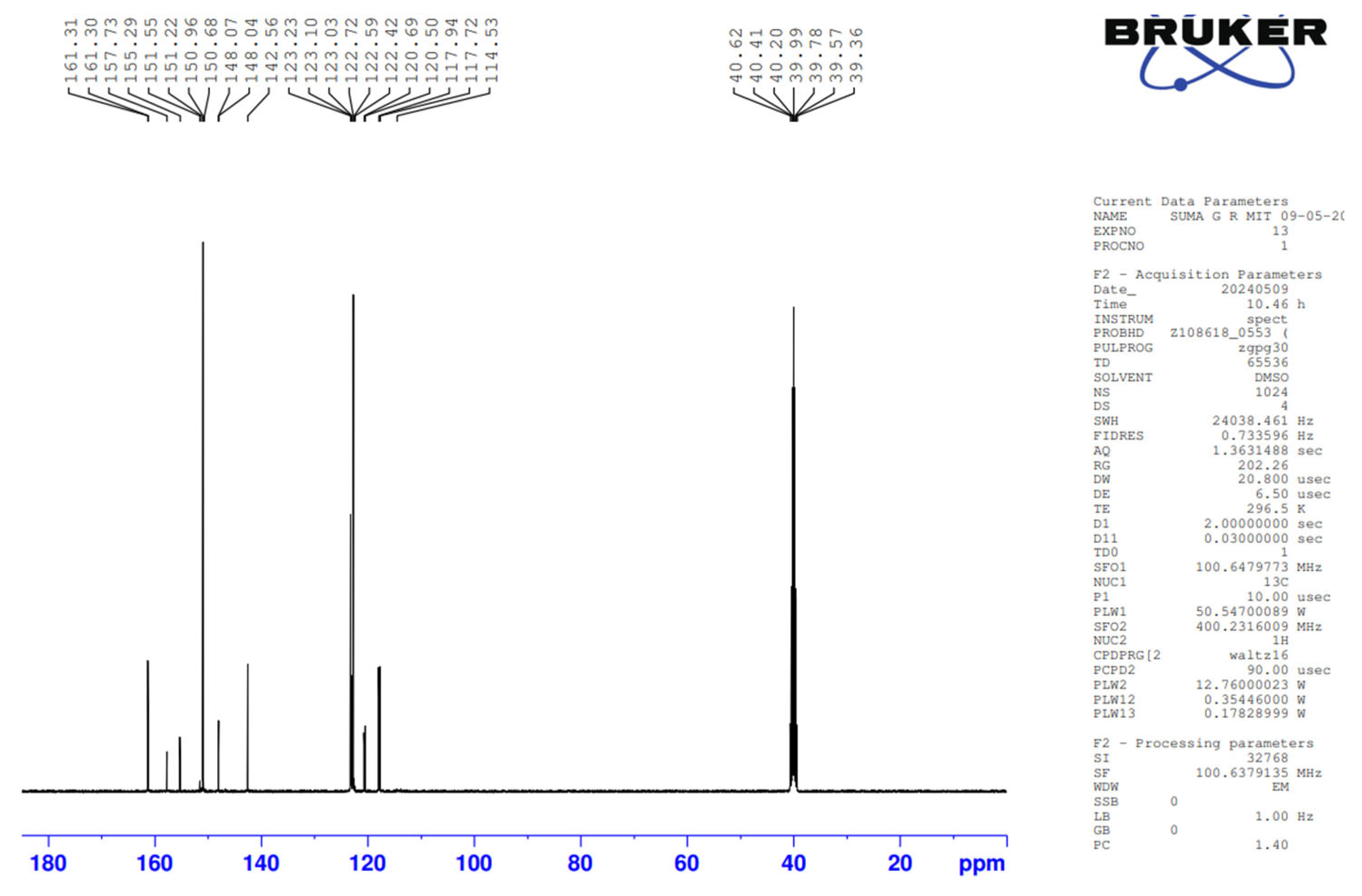

The synthesized Pyridine containing Schiff base is characterized by NMR and FTIR spectroscopy. The

1H and

13C NMR spectra of 4Py are given in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 respectively. The observed chemical shift (δ) values in the

1H NMR spectrum of 4Py are:

1H NMR (400MHz, DMSO): δ 8.78 (d,

J = 3.04 Hz, 2H, 2 × CH of Pyridine ring), 8.73 (s, 1H, 1 × aldimine), δ 7.85 (d,

J= 4.8 Hz, 2H, 2×CH of pyridine ring), δ 7.64 (d,

J= 6.4 Hz, 1H, 1 ×CH of benzene ring), 7.50 (t,

J1 =8.8 Hz,

J2 =8.8 Hz, 1H × CH of benzene ring), 7.40-7.37 (m, 1H, 1 × CH of benzene ring). The observed

13C NMR peaks and the values of corresponding chemical shifts for 4Py are: δ 117.83 (1C, s), 120.59 (2C, s), 122.73 (1C, s), 123.06 (1C, s), 123.23 (1C, s), 142.05 (1C, s), 148.05 (1C, s), 150.65 (1C, s), 151.38 (1C, s), 155.29 (1C, s), 161.30(1C, s). The peaks obtained in the spectra are in concurrence with the number of protons and carbons present in the molecular structure of 4Py.

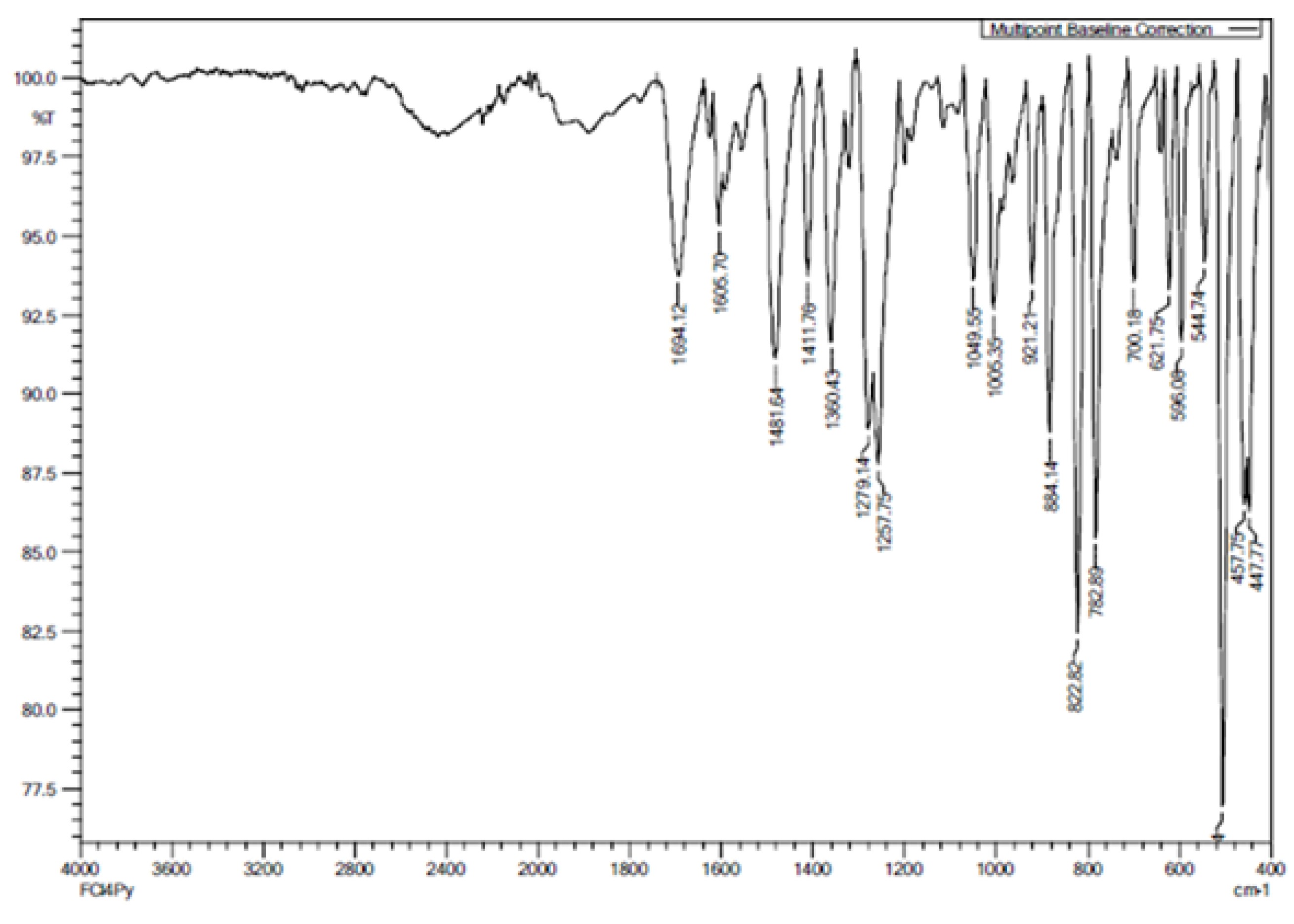

All the HB complexes, i.e., 4Py:

nOBA (

n = 2 - 12), are characterized by FTIR. The FTIR spectra of the proton acceptor (4Py) is given in

Figure 4. The absorption bands beyond 3100 cm

−1 are absent in spectrum of the Schiff base (3), which confirms the absence of free -NH

2 group of 3-chloro-4-fluoroaniline. The absorption band corresponding to C=O stretching of pyridine carboxaldehyde in around 1700 cm

−1 is also absent, which indicates that the condensation reaction between the aniline and carboxaldehyde have been taken place. The peak at 1605 cm

−1 infers the C=N stretching of Schiff base.

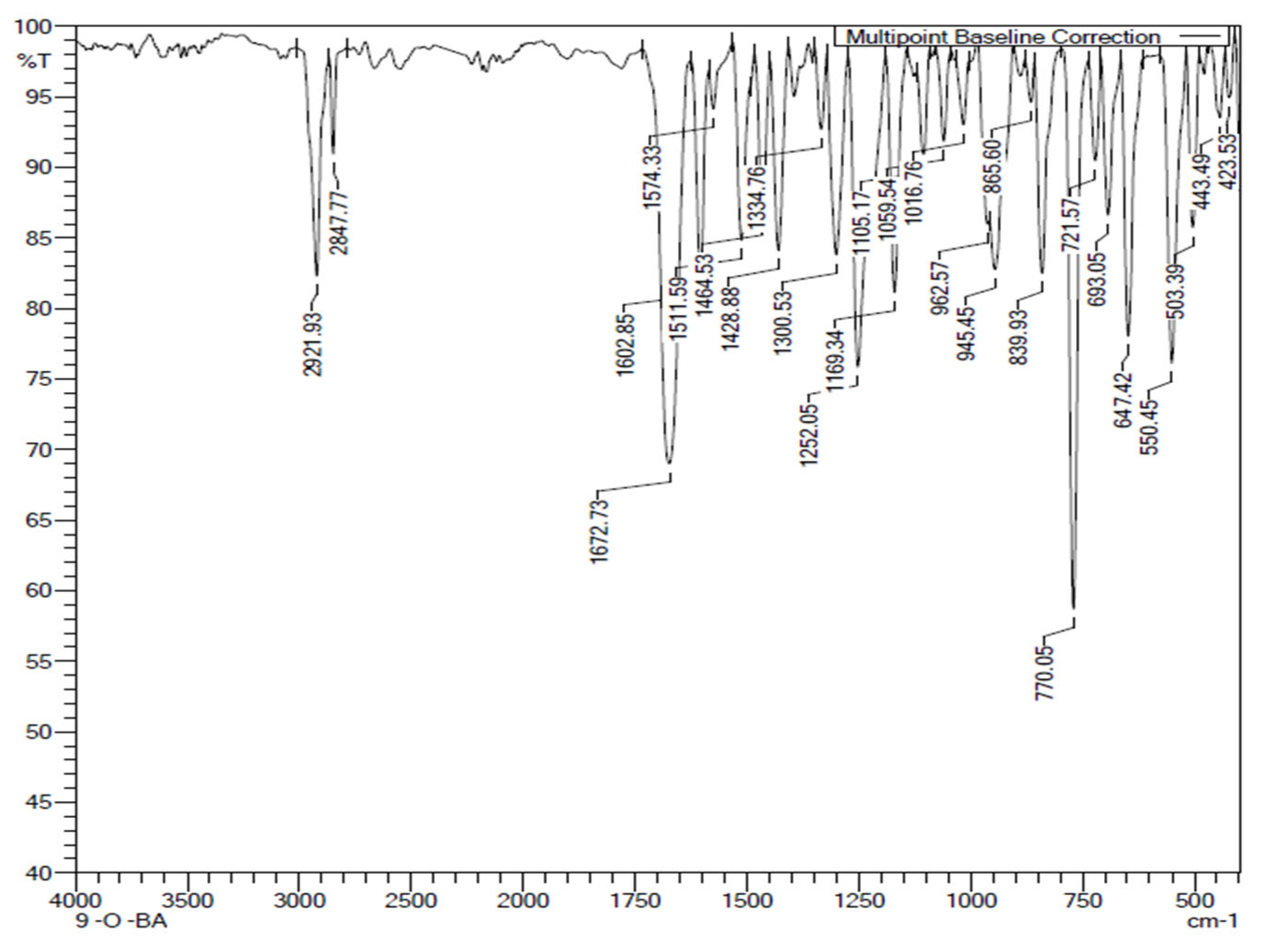

The FTIR spectrum of the proton donor, 9OBA (a representative of

nOBA) is given in

Figure 5. The C=O stretching of carboxylic acid appeared at 1672 cm

−1, the aromatic and aliphatic C-H stretching of the 9OBA are observed at 2912 and 2847 cm

−1 respectively. The O-H stretching of acid is merged with C-H at around 2912 cm

-1. Peaks at 1429 and 945 cm

−1 are attributed to the O-H in-plane and out-of-plane bending modes respectively. A peak at 1300 cm

−1 is attributed to the C-O stretching mode.

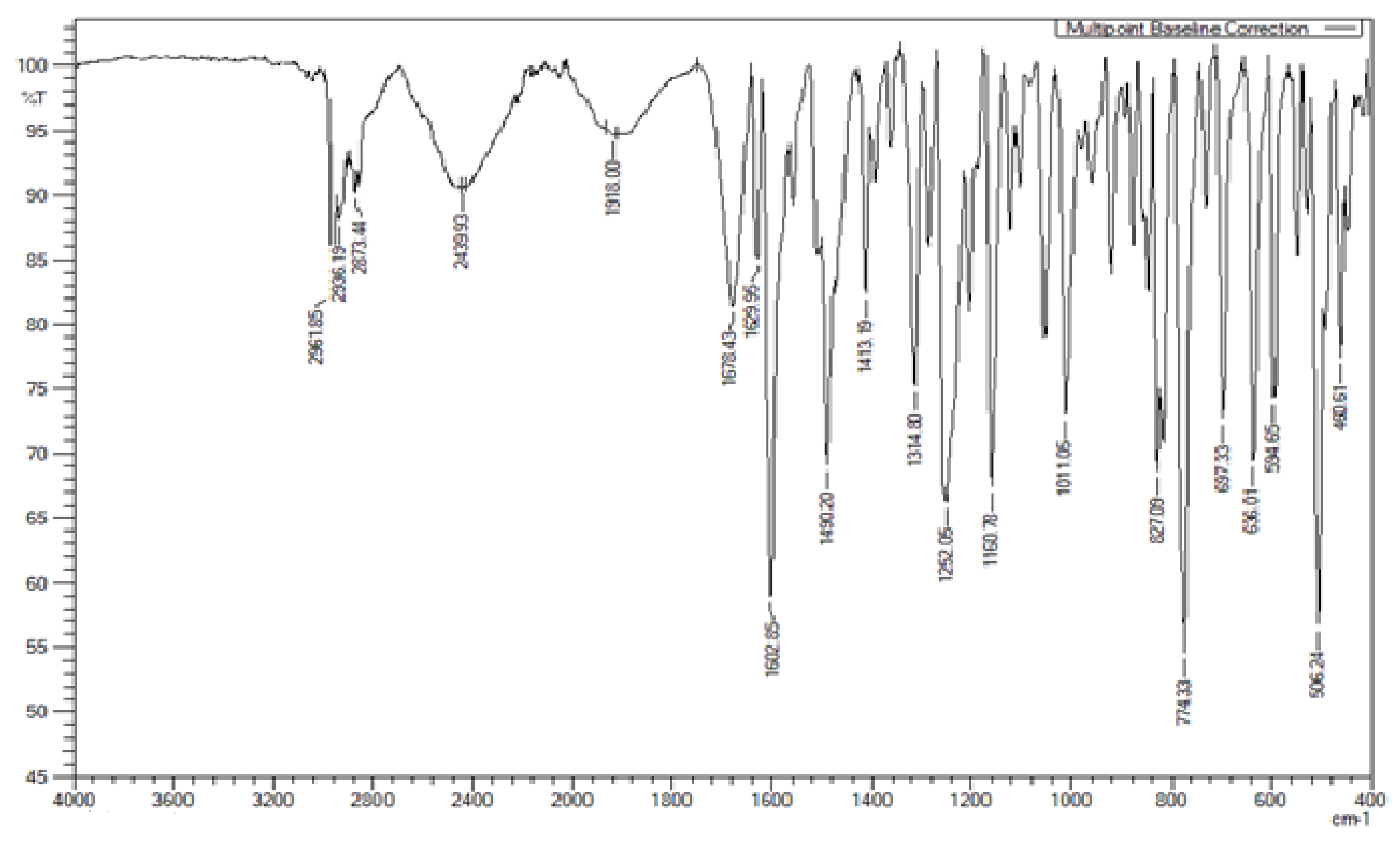

The FTIR spectrum of the HB complex i.e., 4Py:9OBA is given in

Figure 6.

From the FTIR spectrum of 4Py:9OBA, it is observed that additional absorption bands at 2439, 1918 cm

−1 confirms the presence of intermolecular HB interactions between lone pair of electrons of pyridine nitrogen and hydrogen of carboxylic acid group. These observations are in concurrence with the other similar HB complexes reported [

30,

41,

42,

44]. Similar observations are found in other binary mixtures of HB complexes i.e., 4Py:

nOBA (

n = 2-12) in the present study and are included in the

supplementary information.

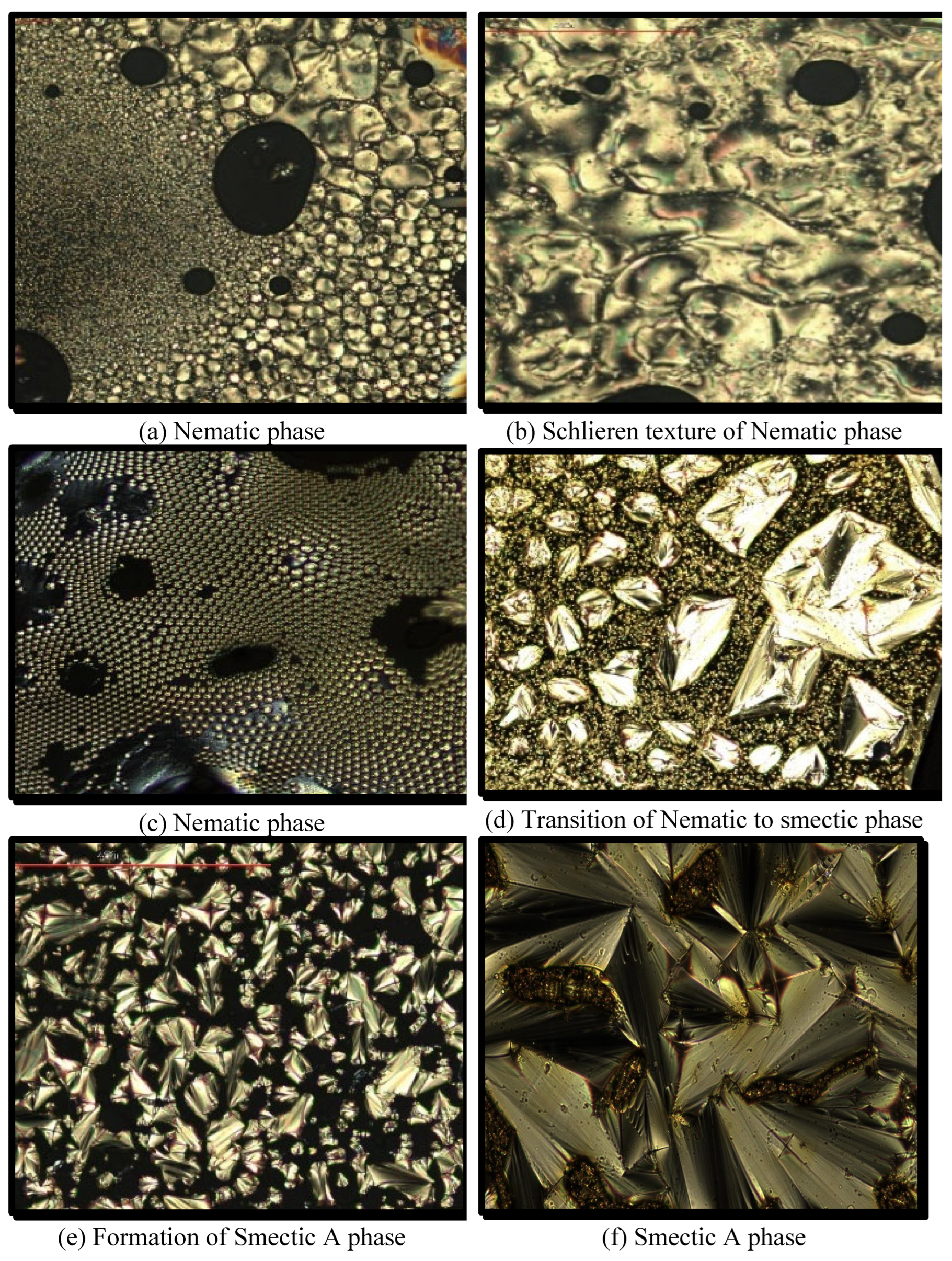

2.3. Phase Behavior of HB Complexes, 4Py:nOBA:

The phase sequence and the transition temperatures of the HB complexes are evaluated with the help of POM under crossed polarizers and in conjunction with a temperature controller. Only nematic mesophase is prevalently reported in the lower homologues of 4-

n-alkyloxybenzoic acids, viz., 4-propyloxy to 4-hexyloxybenzoic acids. The intermediate and higher members of the series viz., 4-heptyloxy to 4-dodecyloxybenzoic acids are reported [

44,

45] to exhibit both nematic and smectic-C mesophases. A threaded marble texture is observed for nematic phase in the lower homologues, schlieren texture is observed for nematic phase in the middle and higher members of the

nOBAs. Broken focal conic fan texture in homogeneous regions and schlieren texture is observed in homeotropic regions simultaneously for smectic-C mesophase. When the

nOBAs are treated with 4Py in the present study, very interesting mesomorphism is observed. The lower member of the series viz., 4Py:2OBA is non-mesomorphic, while the other lower homologues viz., 4Py:3OBA, 4Py:4OBA exhibited nematic phase with Schlieren texture containing four brush disclinations. The intermediate members viz., 4Py:5OBA and 4Py:6OBA exhibited an induced smectic-A (SmA) mesophase with focal conic fan texture in homogeneous regions and pseudo isotropic texture in homeotropic regions simultaneously. It is also observed that the nematic phase (characteristic of 1-D orientational ordering) is quenched in higher homologues (viz., 4Py:7OBA to 4Py:12OBA) of the series. The different mesophases exhibited by the 4Py:

nOBA complexes are shown in

Figure 7.

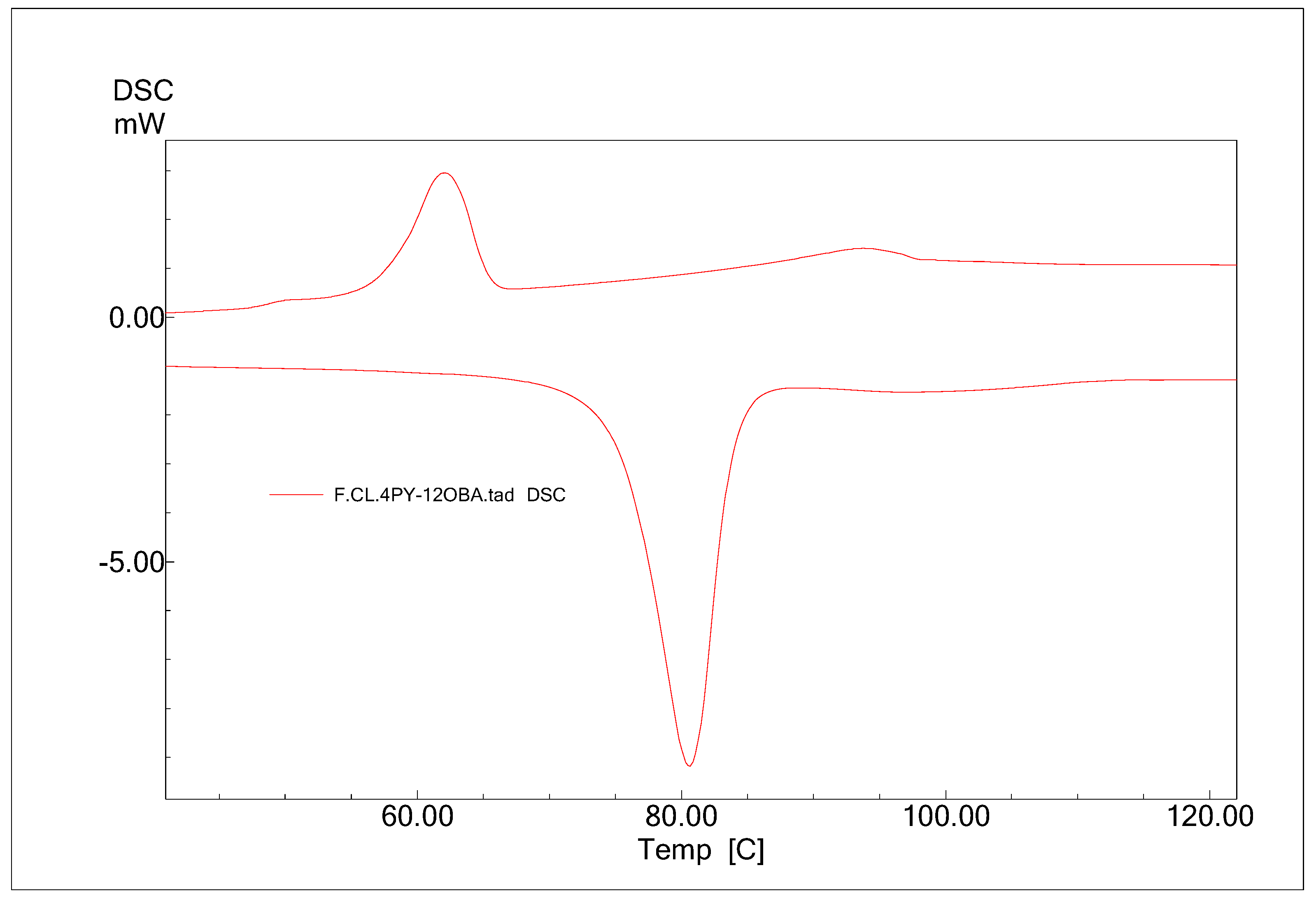

The phase transition temperatures and the enthalpy changes across the phase transitions are determined by DSC. The DSC thermograms of 4Py:12OBA are given in

Figure 8 as a representative of the series. The DSC thermograms of other HB complexes are given in

supplementary information.

The phase transition temperatures and the enthalpy changes of the HB complexes observed in thermal studies are given in the following

Table 1.

The quenching of nematic phase and formation of smectic phases (with and without tilt order) with layering order in higher homologues is due to the formation of a relatively strong HB interactions between the proton-donor and proton acceptor moieties with the increasing chain length. Due to inductive effect, the electron donating tendency of Oxygen gets reduced as the alkyloxy chain increases in a homologue and it leads to promote proton donating tendency of the carboxylic acid. Thus, increasing chain length in 4Py:nOBA series exhibits an increasing strength of HB interactions. Hence, increasing chain length results in a layered organization, which in turn promoted smectic polymorphism by quenching nematic polymorphism.

The mesomorphic thermal spans of the present series of HB complexes are compared with the mesogenic 4-

n-alkyloxybenzoic acids and are given in

Table 2.

It is observed that the lower members of 4Py complexes showed higher mesomorphic thermal spans than the corresponding nOBAs. The mesomorphic thermal spans of intermediate and higher members of 4Py complexes are on par with that of nOBAs and not much appreciable change. The dihalo substituents on lateral positions of the carboxylic acid (non-mesogen) moiety appreciably affected the mesomorphic thermal spans with non-mesogenic calamitic Schiff base containing pyridine moiety through intermolecular HB interactions, in our previous studies. But the mesomorphic thermal spans in the present case in which the dihalo substituents are on the pyridine moiety stabilized the mesomorphism of nOBAs without appreciable change. Interestingly, nematic, and smectic mesophases towards the ambient temperatures are observed in the present studies. The clearing temperatures are also decreased in case of 4Py complexes in comparison with nOBAs.

3. Materials and Methods

The starting materials viz., 3-chloro-4-fluoroaniline and 4-pyridine carboxaldehyde are procured from Aldrich and TCI respectively; 4-n-alkyloxybenzoic acids (ethyl to dodecyl homologues) are purchased from Frinton Laboratories; Acetic acid and Tetrahydrofuran (THF) are purchased from E. Merck, India. The chemicals were used as received from the suppliers without any further purification. Double distilled Ethanol is used as solvent in the synthesis of Schiff base. To monitor the progress / completion of reactions and to check the purity of the product, thin layer chromatography (TLC) was used. Zinc plates precoated with silica gel / neutral alumina TLC plates are procured from E. Merck, India. Shimadzu-8701 Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer in attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode is used for recording the vibrational spectra. The 1H and 13C Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectra of the products are recorded using Bruker Avance 400 MHz NMR spectrometer with DMSO as a solvent and tetramethyl silane (TMS) as an internal standard. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in parts per million (ppm) and coupling constants (J) are given in Hz. The LC behavior of the newly synthesized HB complexes was studied with the help of a Leica Polarizing optical microscope (POM) in conjunction with a Linkam hot stage and a digital camera. The phase transition temperatures and the corresponding enthalpy changes are determined by differential scanning calorimeter (Shimadzu, DSC-60). The heating and cooling rates employed for textural observations are 10 °C/min and the thermograms are recorded at 10 °C/min for both heating and cooling cycle by DSC.

4. Conclusions

The role of molecular architecture on mesomorphism is studied systematically by varying the alkyl chain length of the 4-n-alkyloxycarboxylic acids. It is observed that the nematic phase exhibited by nOBAs is quenched and induced SmA mesophase i.e., the HB interactions favoured the layering order and stabilized the mesomorphism in the present studies. The intermolecular HB interactions between a dihalo substituted benzoic acid (non-mesogen) and a Schiff base containing pyridine (non-mesogen) were found to possess higher mesomorphic thermal spans than the present case of same between a dihalo substituted Schiff base containing pyridine and mesomorphic nOBAs. It is imperative that lateral substituents on either of the proton donor or proton acceptor influence the mesomorphic thermal spans as well as their melting and clearing temperatures. Through systematic studies by changing the nature and size of the substituent on proton donor and proton acceptor, the melting and clearing temperatures as well as the mesomorphic thermal span can be tuned through intermolecular HB interactions. Research in this area could expand to show the influence of different functional groups or substituents or structural variations on the formation or stability of mesomorphism. Apart from the traditional LC technologies, there is also considerable scope to explore these supramolecular systems in other applications such as smart coatings, energy storage, biocompatible materials for medical devices and so on.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: FT-IR spectrum of 4Py:nOBA complexes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Srinivasulu Maddasani; methodology, Suma G. R. and Vijayakumar V.N.; software, Suma G. R.; validation, Srinivasulu Maddasani, Raviraj Shetty and Bhavanari Mallikarjun; formal analysis, Suma G. R. and Srinivasulu Maddasani; investigation, Suma G. R., Srinivasulu Maddasani and Vijayakumar V.N.; resources, Bhavanari Mallikarjun; Srinivasulu Maddasani; data curation, Suma G. R., Srinivasulu Maddasani and Vijayakumar V.N.; writing—original draft preparation, Suma G. R.; writing—review and editing, Srinivasulu Maddasani, Raviraj Shetty and Bhavanari Mallikarjun; visualization, Suma G. R., Srinivasulu Maddasani; supervision, Srinivasulu Maddasani; project administration, Srinivasulu Maddasani; funding acquisition, Srinivasulu Maddasani and Bhavanari Mallikarjun; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE) through Intramural grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided by the authors whenever required.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their heartfelt gratitude to the management of the Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE, Institute of Eminence and Deemed to be University) and Bhandarkars’ Arts and Science College, Kundapura, Karnataka, India for providing the necessary technical and instrumentation facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared |

| POM |

Polarising Optical Microscope |

| DSC |

Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

|

nOBAs |

4-n-alkyloxybenzoic acids |

| 4Py |

3-chloro-4-fluoro-N-((pyridin-4-yl)methylene)benzenamine |

| N |

Nematic |

| SmA |

Smectic-A |

| Cr |

Crystal |

| Iso. |

Isotropic liquid |

References

- Andrienko D. Introduction to liquid crystals. J Mol Liq. 2018;267:520–41. [CrossRef]

- Kumar PA, Srinivasulu M, Pisipati VGKM. Induced smectic G phase through intermolecular hydrogen bonding. Liq Cryst. 1999;26(9):1339–43.

- Srinivasulu M, Satyanarayana PVV, Kumar PA, Pisipati VGKM. Induced crystal G phase through intermolecular hydrogen bonding VII. Influence of non-covalent interactions on mesomorphism and crystallization kinetics. Liq Cryst. 2001;28(9):1321–1329.

- Yogeshvar Tyagi. Liquid crystals: An approach to different state of matter. Pharma Innov J. 2018;7(5):540–5.

- Thaker BT, Patel PH, Vansadiya AD, Kanojiya JB. Substitution effects on the liquid crystalline properties of thermotropic liquid crystals containing schiff base chalcone linkages. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst. 2009;515(October 2012):135–47.

- Durgapal SD, Soni R, Soman SS, Prajapati AK. Synthesis and mesomorphic properties of coumarin derivatives with chalcone and imine linkages. J Mol Liq [Internet]. 2020;297:111920. [CrossRef]

- Soman SS, Jain P. Design, synthesis and study of calamitic liquid crystals containing chalcone and schiff base linkages along with terminal alkoxy chain. J Adv Sci Res. 2022 Apr 30;13(04):59–68.

- Mezzenga R, Seddon JM, Drummond CJ, Boyd BJ, Schröder-Turk GE, Sagalowicz L. Nature-Inspired Design and Application of Lipidic Lyotropic Liquid Crystals. Adv Mater. 2019;31(35):1–19.

- Shiyanovskii S V., Lavrentovich OD, Schneider T, Ishikawa T, Smalyukh II, Woolverton CJ, et al. Lyotropic chromonic liquid crystals for biological sensing applications. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst. 2005;434:259/[587]-270/[598].

- Wang X, Zhang Y, Gui S, Huang J, Cao J, Li Z, et al. Characterization of Lipid-Based Lyotropic Liquid Crystal and Effects of Guest Molecules on Its Microstructure: a Systematic Review. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2018;19(5):2023–40.

- Devadiga D, Ahipa TN. An up-to-date review on halogen-bonded liquid crystals. J Mol Liq 2021;333:115961. [CrossRef]

- An JG, Hina S, Yang Y, Xue M, Liu Y. Characterization of liquid crystals: A literature review. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2016;44(4):398–406.

- Yilmaz Canli N, Ocak H, Okutan M, Karanlık G, Bilgin Eran B. Comparative dielectric parameters and conductivity mechanisms of pyridine-based rod-like liquid crystals. Phase Transitions. 2020;0(0):784–92. [CrossRef]

- Mohammady SZ, Aldhayan DM, El-Tahawy MMT, Alazmid MT, El Kilany Y, Zakaria MA, et al. Synthesis and DFT Investigation of New Low-Melting Supramolecular Schiff Base Ionic Liquid Crystals. Crystals. 2022;12(2).

- Wei Y, Jang CH. Liquid crystal as sensing platforms for determining the effect of graphene oxide-based materials on phospholipid membranes and monitoring antibacterial activity. Sensors Actuators, B Chem. 2018;254:72–80.

- Brown CM, Dickinson DKE, Hands PJW. Diode pumping of liquid crystal lasers. Opt Laser Technol. 2021;140.

- Shibaev P V., Wenzlick M, Murray J, Tantillo A, Howard-Jennings J. Rebirth of liquid crystals for sensoric applications: Environmental and gas sensors. Adv Condens Matter Phys. 2015;2015(February 2016).

- Wang Z, Xu T, Noel A, Chen YC, Liu T. Applications of liquid crystals in biosensing. Soft Matter. 2021;17(18):4675–702.

- Vahedi A, Kouhi M. Temperature effects on liquid crystal-based tunable biosensors. Optik (Stuttg). 2021;242(May):167383.

- Tsuji T, Chono S. Development of micromotors using the backflow effect of liquid crystals. Sensors Actuators, A Phys. 2021;318:112386.

- Karaszi Z, Salamon P, Buka Á, Jákli A. Lens shape liquid crystals in electric fields. J Mol Liq. 2021;334.

- Nguyen DK, Jang CH. A Cationic Surfactant-Decorated Liquid Crystal-Based Aptasensor for Label-Free Detection of Malathion Pesticides in Environmental Samples. Biosensors. 2021;11(3).

- Nguyen DK, Jang CH. A label-free liquid crystal biosensor based on specific dna aptamer probes for sensitive detection of amoxicillin antibiotic. Micromachines. 2021;12(4).

- Duan R, Hao X, Li Y, Li H. Sensors and Actuators B : Chemical Detection of acetylcholinesterase and its inhibitors by liquid crystal biosensor based on whispering gallery mode. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2020;308(November 2019):127672.

- Karas LJ, Wu CH, Das R, Wu JIC. Hydrogen bond design principles. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Mol Sci. 2020;10(6):1–15.

- Alamro FS, Ahmed HA, Naoum MM, Mostafa AM, Alserehi AA. Induced smectic phases from supramolecular h-bonded complexes based on non-mesomorphic components. Crystals. 2021;11(8).

- Srinivasulu M, Satyanarayana PVV, Kumar PA, Pisipati VGKM. Induced Smectic-G Phase through Intermolecular Hydrogen Bonding Part VIII: Phase and Crystallization Behaviours of 2-(p-n-heptyloxybenzylidene imino)-5-chloro-pyridine: P-n-alkoxybenzoic acid (HICPrwABA) Complexes. Zeitschrift fur Naturforsch - Sect A J Phys Sci. 2001;56(9–10):685–91.

- Song X, Li J, Zhang S. Supramolecular liquid crystals induced by intermolecular hydrogen bonding between benzoic acid and 4-(alkoxyphenylazo) pyridines. Liq Cryst. 2003;30(3):331–5.

- Steiner T. The whole palette of hydrogen bonds. Angew Chemie-International Ed [Internet]. 2002;41:48. Available from: http://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=related:jR-YG4yO778J:scholar.google.com/&hl=en&num=20&as_sdt=0,5%5Cnpapers2://publication/uuid/A172FF25-1915-4B6A-A431-B3DB11953E65.

- Bhagavath P, Mahabaleshwara S, Bhat SG, Potukuchi DM, Chalapathi P V., Srinivasulu M. Mesomorphic thermal stabilities in supramolecular liquid crystals: Influence of the size and position of a substituent. J Mol Liq [Internet]. 2013;186:56–62. [CrossRef]

- Mohammady SZ, Aldhayan DM, Hagar M. Pyridine-based three-ring bent-shape supramolecular hydrogen bond-induced liquid crystalline complexes: Preparation and density functional theory investigation. Crystals. 2021;11(6).

- Poornima, Bhagavath; Sangeetha G. Bhat,; Mahabaleshwara, S.; Girish, S. R.; Potukuchi, D. M.; and Srinivasulu, M., Induced Smectic-A Phase at Low Temperatures through Self Assembly, J. Mol. Struct., (2013) 1039, 94-100.

- Poornima Bhagavath and Srinivasulu Maddasani, Effect of rigid core and π – π interactions on the induced mesomorphism in intermolecular hydrogen bonded complexes, ChemPhysChem., (2025) (communicated, under revision).

- Poornima, Bhagavath, Mahabaleshwara, S., Sangeetha G. Bhat, D. M. Potukuchi, Prakasha Shetty, and Srinivasulu, M., Influence of polar substituents and flexible chain length on mesomorphism in non-mesogenic linear hydrogen bonded complexes, J. Mol. Liq., (2021) 336, 116313.

- Khan IM, Ahmad A, Ullah MF. Synthesis, crystal structure, antimicrobial activity and DNA-binding of hydrogen-bonded proton-transfer complex of 2,6-diaminopyridine with picric acid. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol 2011;103(1):42–9. [CrossRef]

- Herschlag D, Pinney MM. Hydrogen Bonds: Simple after All? Biochemistry. Steiner T. The whole palette of hydrogen bonds. Angew Chemie-International Ed [Internet]. 2002;41:48. Available from: http://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=related:jR-YG4yO778J:scholar.google.com/&hl=en&num=20&as_sdt=0,5%5Cnpapers2://publication/uuid/A172FF25-1915-4B6A-A431-B3DB11953E652018;57(24):3338–52.

- A.V.S.N. Krishna Murthy, M. Srinivasulu, Madhumohan M. L. N., Chalapathy P. V.,Y. V. Rao and D. M. Potukuchi, Influence of molecular architecture, hydrogen bonding, chemical moieties and flexible chain for smectic polymorphism in (4)EoBD(3)AmBA:nOBAs, Mol.Cryst. Liq. Cryst. (2021) 715 (1), 1-36.

- Pai P, Kulkarni SD, Srinivasulu M, Baral M, Apoorva MM, Bhagavath P. Enhanced conductivity in nanoparticle doped hydrogen bonded binary mixture. J Mol Liq., 2019;296:111754. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Pacheco AD, Hernández-Vergara M, Jaime-Adán E, Hernández-Ortega S, Valdés-Martínez J. Schiff bases as possible hydrogen bond donors and acceptors. J Mol Struct. 2021;1234.

- Carreño A, Rodríguez L, Páez-Hernández D, Martin-Trasanco R, Zúñiga C, Oyarzún DP, et al. Two new fluorinated phenol derivatives pyridine schiff bases: Synthesis, spectral, theoretical characterization, inclusion in epichlorohydrin-β-cyclodextrin polymer, and antifungal effect. Front Chem. 2018;6(JUL):1–13.

- Bhat SG, Srinivasulu M, Girish SR, Padmalatha, Bhagavath P, Mahabaleshwara S, et al. Influence of moieties and chain length on the abundance of orthogonal and tilted phases of linear hydrogen-bonded liquid crystals, Py16BA:nOBAs. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst. 2012;552 (June 2013):83–96.

- Sangeetha G. Bhat, S. R. Girish, Poornima Bhagavath, Mahabaleshwara S., D. M. Potukuchi and Srinivasulu Maddasani; Self-assembled liquid crystalline materials with fatty acids: FTIR, POM and thermal studies; J. Therm. Analy. Calorim. (2018) 132, 989 – 1000.

- A. Mermer, N. Demirbas, H. Uslu, A. Demirbas, S. Ceylan, and Y. Sirin, “Synthesis of novel Schiff bases using green chemistry techniques; antimicrobial, antioxidant, antiurease activity screening and molecular docking studies,” J. Mol. Struct., vol. 1181, pp. 412–422, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Muniprasad, M.; Srinivasulu, M.; V. C. Pallavajhula and Potukuchi, D. M., Induction of Liquid Crystalline Phases and Influence of Chain Length of Fatty Acids in Linear Hydrogen-Bonded Liquid Crystal Complexes; Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst., 557:1, 102 – 117 (2012).

- Murthy AVSNK, Chalapathy P V., Srinivasulu M, Madhumohan MLN, Rao Y V., Potukuchi DM. Influence of flexible chain, polar substitution and hydrogen bonding on phase stability in Schiff based (4)PyBD(4')BrA-nOBA series of liquid crystals. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst. 2018; 664(1):46–68. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).